Abstract

In this brief article, we summarize recent reports about endogenous ouabain (EO), a cardiotonic steroid (CTS). This includes analysis of mammalian EO, the discovery of EO isomers, regulation of intracellular signaling by EO, and the roles of EO in hypertension, pregnancy, and heart and kidney diseases. Novel ouabain-resistant mice that elucidate the key roles of α2 Na+ pumps and their CTS binding site are also discussed.

Endogenous ouabain and its isomers

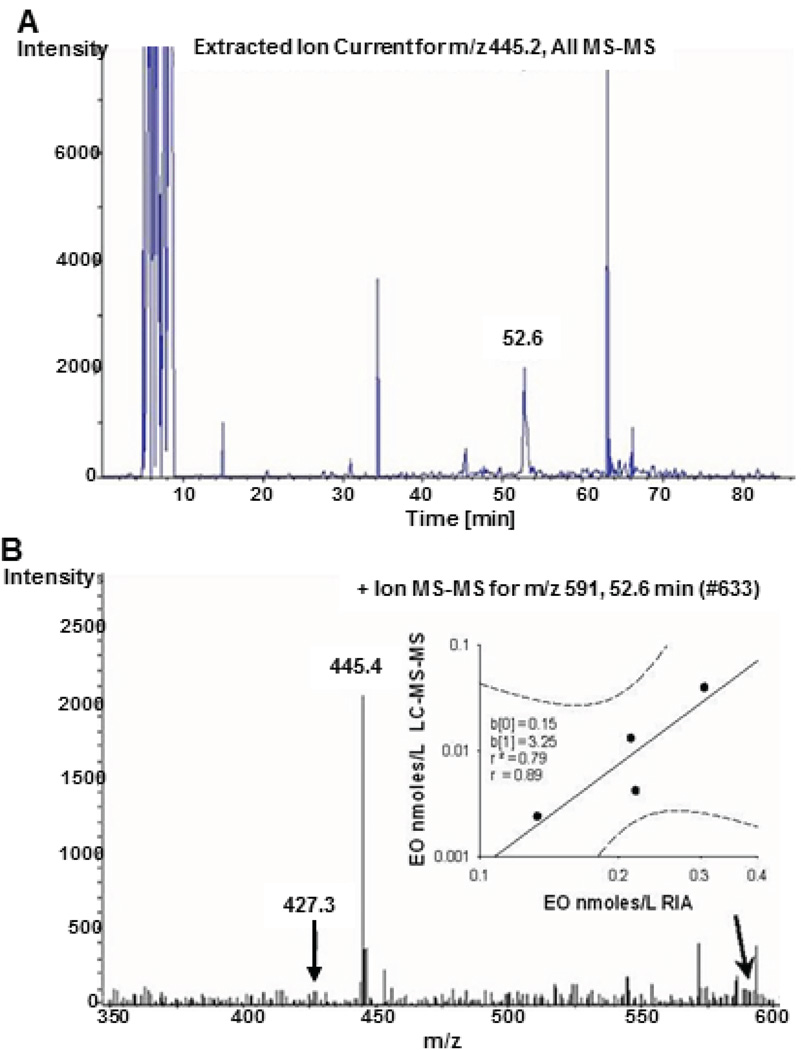

EO was first identified in human plasma 25 years ago.1, 2 Despite confirmation in humans and other mammals with mass spectrometry (MS; Figure 1; Online Supplement Figures S1–S6), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and combined liquid chromatography (LC)-immunology methods,3–6 human EO has remained controversial.7 New analytical studies and related findings should allay skepticism. For example, employment of multistage MS (MS-MS or MS2, and MS-MS-MS or MS3) to examine the effects of pregnancy and of central angiotensin (Ang) II infusion on EO in rat plasma led to the discovery of two novel EO isomers.8, 9 One isomer (#1) has MS2 and MS3 product ion spectra indistinguishable from those of EO, but is slightly more polar than EO; it binds to the antibody employed in our radioimmunoassay (RIA). Isomer 2 is slightly less polar than EO, has a distinct MS3 spectrum, and cross-reacts weakly in our RIA. The primary structural difference(s) between EO and these isomers may involve the steroid nucleus. Importantly, neither isomer was previously described or is detectable in commercial (plant) ouabain.8, 9

Figure 1.

Endogenous ouabain determined by LC-MS-MS in plasma from patients with cardiomyopathy. Panel A. Capillary LC-MS-MS product ion chromatogram for a plasma extract from a patient with cardiomyopathy. The ion current peaks represent positively charged molecular product ions with an M+Li+/z ratio equivalent to the lithiated aglycone of ouabagenin (m/z 445.4). Under the slow LC gradient conditions employed, the specific ion current peak at 52.6 minutes is the lithiated aglycone of EO and matches the retention time for EO in this system. Panel B. MS-MS spectrum for the ion current peak at 52.6 minutes. Arrow points to m/z 591 which corresponds to the lithiated EO parent ion. Inset: Correlation (r=0.89) between plasma EO determined by RIA and LC-MS/MS from four cardiomyopathic patients. The slope of the relationship indicates that EO per se explained ~15% of the RIA signal in this patient group (see Online Supplement for further information). Dashed lines are the 95 % confidence interval. From Pitzalis et al.12 with permission.

A recent report based on an LC-MS2 approach concluded that EO was not detected in human plasma,10 but the LC gradient was extraordinarily short so that EO in plasma may have been missed (see Data Supplement). Further, critical data supporting their conclusion were absent from the published article,10 and the key product ion current recording had inexplicable gaps (Figure S7) at locations where signals from EO isomers might be anticipated.11 Also, the plasma used by Baecher and colleagues10 tested positive for EO11 with a well-documented RIA.8, 9, 12 These RIA data are significant because EO is routinely detected when the same sample extracts are subjected to LC-RIA and LC-MS.5, 8, 9, 12 In contrast to MS, RIA-based estimation of EO includes the unpredictable contribution of cross-reactivity from related molecules5, 13 such as isomers 1 and 2,8, 9 which may vary with gender, age and disease.

The carbon isotope (13C/12C) ratio is helpful to distinguish plant versus animal metabolism. The natural abundance of 13C in the bovine adrenal EO and, thus, the 13C/12C ratio determined by high resolution MS, was significantly lower than in plant ouabain.14 EO therefore is neither a laboratory contaminant nor an ingested plant material. If adrenal EO isn’t plant ouabain sequestered from the circulation,15 it must be, either in whole (i.e., sugar and steroid) or in part (steroid, alone), an endogenous product.

What is the origin of circulating EO?

Human, bovine and rodent data indicate that the adrenal cortex contains the highest concentration of EO in the body.1, 3 Also, adrenalectomized rats1 and adrenal insufficiency patients16 have exceptionally low plasma EO levels. Primary cultured bovine and human adrenal cortical cells secrete more EO than is present in the cells, indicating net synthesis.17 Adrenal venous EO concentrations (adrenal vein cannulation) in the dog were 4–5 fold higher than that in arterial blood.18 Similarly, in human hypertensives undergoing testing for hyperaldosteronism, the adrenal venous effluent EO concentration was 2–3 fold higher than in inferior vena cava blood.19 In that study, MS3 analysis of the plasma confirmed that the endogenous substance was EO and an isomer (likely isomer 2). Thus, the adrenal cortex is most probably the primary source of circulating EO, and aldosterone and EO biosynthesis share a requirement for progesterone.20 The brain is likely also a source of one isomer.9 Regrettably, the biosynthetic pathway for EO remains unresolved. This is due, in part, to the difficulty and the resources required to elucidate an adrenal pathway whose relative carbon flux is ~20–50 fold and ~10,000 fold less than for aldosterone and cortisol, respectively.

Role of the brain in regulating circulating EO

Early work suggested that the central nervous system (CNS) influences the peripheral levels of ouabain-like substances.9, 21 Indeed, brain ouabain-like materials are critical to the ability of low dose angiotensin (Ang) II to raise circulating EO and blood pressure (BP).22–26 Based on new insight into CNS and vascular signaling pathways in salt-sensitive hypertension,27, 28 the role of the brain in controlling circulating EO was recently probed with multi-dimensional MS analytical methods.8, 9, 12 Those studies show that low doses of Ang II, acting within the CNS, up-regulate circulating EO; this, in turn, stimulates downstream arterial myocyte mechanisms that raise vascular tone and long-term BP.9, 28 Upregulation of brain EO, per se, also raises BP.29 Conversely, central blockade of aldosterone synthase, mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs), epithelial Na+ channels (ENaCs) or brain EO prevents the sympathetic hyperactivity.26, 27, 30, 31 These central blockers also prevent or markedly attenuate experimental forms of hypertension induced by high salt, low dose Ang II, or ouabain.26, 27, 30, 31 The participation of EO is documented by the demonstration that mutation of the ouabain/EO receptor site on α2 Na+ pumps to make the pumps ouabain-resistant (α2R/R) blocks ouabain-induced and salt-sensitive forms of hyper-tension in mice.32–35 Importantly, pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and failure are greatly attenuated in α2R/R mice, whereas they are accelerated in these mice when the α1 Na+ pumps are mutated to an ouabain-sensitive form.35, 36 (Note: the α1:α2 expression ratio is ≈4:1 in heart and arteries.37, 38) Thus, in addition to hypertension, target organ damage depends, in part, on high affinity EO binding (see “EO in kidney disease and heart failure”, below).

EO is part of a new neurohumoral pathway in blood pressure control

Compelling evidence indicates that the slow pressor effects of low doses of Ang II depend on an amplifier located in the CNS.27, 33 The amplifier incorporates neuromodulatory components including local aldosterone synthesis, MRs, ENaCs, and increased synthesis and/or levels of EO in the brain.39–42 Prolonged stimulation of this CNS amplifier, especially by Na+ or low dose Ang II, increases sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), often to discrete vascular beds.43 In addition, however, activation of the CNS amplifier raises the circulating levels of peptide hormones including ACTH, a stimulator of adrenal EO secretion,44 vasopressin and growth hormone.45 The relative roles of increased SNA and the humoral components is not clear.

Intracerebroventricular (icv) Ang II infusion also elevates circulating EO.9 Sustained increases in circulating EO, per se, augment the expression of proteins involved in Ca2+ homeostasis and signaling in arterial myocytes.46, 47 The effects of the elevated circulating EO on Ca2+ handling in arterial myocytes in vivo are fully replicated ex vivo with nanomolar ouabain.46, 47 Notably, all the effects of icv Ang II on circulating EO, as well as the reprogramming of peripheral vascular function, and the elevated BP are prevented by icv administration of eplerenone, an MR blocker, as well as by inhibition of aldosterone synthase with FAD286.9 Further, BP elevation by subcutaneous (sc) low dose Ang II + high dietary salt is greatly attenuated by immuno-neutralization of EO with fab fragments that bind ouabain with high affinity.48 Apparently, EO itself can augment basal and stimulated vascular tone and raise BP.

The demonstration that brain Ang II activates a novel long-range neurohumoral-vascular control axis that involves EO is striking. This axis amplifies the long term central effects of Ang II by recruiting CNS components (aldosterone, MRs, epithelial Na+ channels or ENaCs, and ‘brain EO’)27 and peripheral factors that include circulating EO and up-regulated expression of Ca2+ transport proteins in arterial myocytes.9 Collectively, these factors contribute to the ability of chronic central Ang II and increased SNA to elevate and maintain BP. We postulate that this CNS-humoral axis is the delayed “other mechanism” that helps maintain the elevated BP when the direct vasopressor activity of circulating Ang II “plays only a minor role”.49

The Na+ pump is a biased receptor for EO

The physiological and pharmacological effects of the CTS have long been interpreted as the consequence of binding to a highly conserved site on the Na+ pump catalytic (α) subunit and the block of Na+ transport.50 This was confirmed by studies in α2R/R mice51 and mice lacking Na/Ca exchanger-1, NCX1.52

The groundbreaking observation that ouabain binding also activates signaling cascades added critically to the mounting evidence that ouabain is a hormone.53 The ouabain-stimulated signal transduction is mediated by Na+ pumps but is apparently independent of the ion transport function.47, 54 Remarkably, recent work reveals that the ouabain binding site behaves like a “biased” receptor,47 the first example of this phenomenon55 in an ion transport system. Ouabain binding to arterial Na+ pumps activates c-Src, for example, while the binding of digoxin, which is an equi-effective pump inhibitor, does not.47 In fact, digoxin antagonizes ouabain’s effects and vice-versa, both in vivo56–59 and in vitro.47, 60 Thus, biased signaling likely underlies the ability of ouabain and EO to induce hypertension and explains both the inability of digoxin to raise BP and its antihypertensive effect in ouabain-dependent models.56–58

Rostafuroxin (10 µg/kg/day), an ouabain antagonist,60, 61 attenuates ouabain-induced hypertension in rats,61, 62 but 5 mg/day was ineffective in unselected patients with stage I or II hypertension in the OASIS-HT trial.63 Nevertheless, rostafuroxin effectively lowered BP in a sensitive cohort of patients with adducin variants and elevated plasma EO.64 Importantly, rostafuroxin’s affinity for its Na+ pump binding site is relatively low: EC50 ≈ 1.4 µM60, 61 vs ouabain EC50 ≈ 0.5 nM,65 Thus, higher doses might be effective in unselected hypertensives. A new antagonist with higher affinity, that neither inhibits Na+ transport60, 61 nor activates signal transcription,62 may be needed.

Role of genetics in ouabain-induced hypertension

Prolonged ouabain administration induces hypertension in many,25, 32, 66 but not all,7, 67 outbred rodent strains. This variable response,7 even within a single strain,68, 69 is neither strange nor surprising. When given high salt, excess mineralocorticoids or other hypertensinogenic substances, not all outbred rats develop hypertension; indeed, this phenotype variation was deliberately exploited to generate lines of rats with heightened or lowered susceptibility to hypertension.70, 71 Experience with ouabain is no different. Starting from a large founding colony of outbred Sprague-Dawley rats in which high ouabain sensitivity was the dominant phenotype in both genders, minimal inbreeding led to distinct strains with ouabain-sensitive and -resistant BP phenotypes within three generations.68, 72 The sensitive strain exhibited altered ganglionic synapse plasticity that was normalized with in vivo captopril.72 Some components of the pressor mechanism of ouabain that likely function in the sensitive strain have been partially elucidated,28, 69 whereas elevated vagal tone and increased CGRP may underlie the ouabain-resistant phenotype.67

Hypertension mediated by ouabain-sensitive α2 Na+ pumps in the brain

Liddle’s syndrome is a salt-sensitive hypertension due to enhanced ENaC activity caused by loss of regulation by the ubiquitin ligase, NEDD4-2.73 A mouse model, NEDD4-2 knockout, NEDD4-2−/−, with up-regulated renal ENaCs, exhibits mild salt-sensitive hypertension.74 Brain ENaCs are also up-regulated, and salt-sensitive hypertension is prevented by icv infusion of very low dose benzamil, an ENaC blocker75 that inhibits the CNS neurohumoral pathway.9 Further, although icv Na+-rich cerebrospinal fluid induces hypertension in wild-type and NEDD4-2−/− mice,75 the hypertension is prevented by expression of ouabain-resistant α2 pumps, i.e., in α2R/R and NEDD4-2−/−-α2R/R mice.34, 75 Thus, an EO-like compound and CNS, as well as renal, ENaCs, and α2 Na+ pumps apparently participate in the hypertension of Liddle’s syndrome. This complements prior studies showing that α2 ouabain binding site integrity76, 77 and its ligand77–79 are essential for other forms of experimental hypertension.28

Paradoxical effects of EO in pregnancy and preeclampsia

Normal pregnancy is a volume expanded state in which plasma ACTH, renin, aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are elevated.80 In view of the increased volume and reduced vasoreactivity in pregnancy, it is surprising that excess mineralocorticoid triggers a preeclampsia-like state in rats.81 Further, excess ADH increase in early pregnancy may predict preeclampsia in humans.82, 83 This suggests that fluid volume in pregnancy is more relevant than previously appreciated: circulating volumes in women destined to become preeclamptic appear to be inappropriately elevated very early in pregnancy.84 The mechanisms by which early volume overexpansion might trigger vascular changes that lead to preeclampsia require investigation.

Circulating ouabain–like materials rise progressively in normal pregnancy, and decline after delivery.85 The earlier reports were recently confirmed with advanced analytical methods: in addition to circulating EO, one of the newly-discovered isomers was markedly elevated in pregnancy.8 Based on the emerging pressor mechanism of ouabain,28 the elevated EO in pregnancy was expected to reprogram vascular function by increasing the expression of arterial myocyte Ca2+ transporters, e.g., NCX1 and TRCPC6. Upregulation of these proteins is triggered by the prolonged elevation of circulating ouabain in normal non-pregnant rats.8, 86, 87 In the high EO state of pregnancy, however, expression of NCX1, which mediates Ca2+ influx and tone in arterial myocytes, was reduced. In other words, normal pregnancy is a high EO state with apparent resistance of the arteries to the pressor action of circulating EO. Indeed, even supra-physiological circulating levels of ouabain failed to raise BP in pregnancy.8 The mechanism of ouabain-resistance is likely to be significant in elucidating the decline of vascular reactivity in pregnancy. Nevertheless, the low BP in pregnant α2R/R mice indicates that the integrity of the α2 Na+ pump ouabain binding site provides a small stimulus to BP in the 3rd trimester of pregnancy.88

Does elevated EO and/or EO resistance have any role in preeclampsia? Circulating EO is linearly related to BP in preeclampsia,89, 90 suggesting that the mechanism underlying ouabain resistance is impaired so that the already elevated EO could raise BP in a dose-dependent manner. Surprisingly, however, in pregnant rats with reduced uterine perfusion pressure and hypertension, prolonged exogenous ouabain administration (additional to the already elevated EO) lowered circulating sFLT1 (soluble fat mobilizing substance-like tyrosine kinase-1) and reduced BP.91 Thus, in this preeclamptic model in which EO is believed to be elevated, ouabain behaved as an antihypertensive and had a net effect on BP that resembled that of digoxin in ouabain-dependent hypertension. The mechanism of this paradoxical and beneficial effect requires investigation. Nevertheless, it now appears that, contrary to earlier ideas, EO upregulation in preeclampsia is of potential benefit to mother and fetus.

At the opposite end of the pregnancy spectrum, recent studies link low circulating EO levels with impaired fetal growth and development: In pregnant mice, anti-ouabain antibodies reduced circulating EO, decreased offspring body weight, and impaired kidney and liver growth. Further, during human pregnancy, circulating EO among women with small-for-gestational age neonates was lower than in women with normal-for-gestational age newborns.92 Ouabain is recognized as a growth promoter, but these new results are the first to suggest that relative lack of EO increases the risk for impaired fetal development. In this context, the aforementioned ouabain resistance of pregnancy makes sense: the elevated circulating EO could exert a growth promoting effect while its hypertensinogenic activity was deactivated. Further evidence that EO is a growth factor in pregnancy is that malnutrition delayed the formation of functional nephrons in the fetus and increased susceptibility to renal injury and disease later in life. Administration of ouabain to malnourished pregnant rats protected fetal kidney development.93

EO in kidney disease and heart failure

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a frequent complication that increases the morbidity and mortality of cardiac surgery. EO can behave as an adrenal-derived stress hormone and has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in clinical studies. In data from two centers (626 patients), preoperative EO was the strongest predictor of surgery-induced AKI at both centers.94 Also, the addition of preoperative plasma EO levels to an accepted clinical model for predicting AKI significantly improved predictability.95 Further, a rat model of ouabain-induced hypertension exhibited reduced creatinine clearance, proteinuria, and impaired podocyte nephrin expression; thus, elevated EO per se may be a direct cause of podocyte damage.94

EO, which may contribute to renal failure96 and may be linked to cardiomyopathy in chronic kidney disease,62, 97, 98 also appears to be a valuable biomarker of heart failure. In 845 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery, plasma EO was correlated negatively with left ventricular ejection fraction, and positively with cardiac end-diastolic diameter and plasma NT-proBNP. Higher EO levels immediately postoperatively were associated with increased 30-day perioperative mortality.99 Thus, both pre- and post-operative EO levels identify patients with more severe cardiovascular presentation and those with a higher risk of morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery.99

Conclusion

During the last five years, numerous notable advances have been made in the understanding of EO, its receptor and the downstream effects of activation of EO in the brain and periphery. While many important questions remain to be investigated, compelling evidence indicates that EO is a significant entity in physiology and contributes to the pathogenesis of many common diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Supported, in part, by NIH/NHLBI Grants R01 HL-45215 and R01 HL-107555 (to MPB and JMH).12

Footnotes

References

- 1.Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Bova S, DuCharme DW, Harris DW, Mandel F, Mathews WR, Ludens JH. Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6259–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathews MR, DuCharme DW, Hamlyn JM, Harris DW, F M, Clark MA, Ludens JH. Mass spectral characterization of an endogenous digitalis-like factor from human plasma. Hypertension. 1991;17(6 Pt 2):930–935. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.6.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schneider R, Wray V, Nimtz M, Lehmann WD, Kirch U, Antolovic R, Schoner W. Bovine adrenals contain, in addition to ouabain, a second inhibitor of the sodium pump. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:784–792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawamura A, Guo J, Itagaki Y, Bell C, Wang Y, Haupert GT, Jr, Magil S, Gallagher RT, Berova N, Nakanishi K. On the structure of endogenous ouabain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6654–6659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Salt intake and depletion increase circulating levels of endogenous ouabain in normal men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R553–R559. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00648.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komiyama Y, Nishimura N, Dong XH, Hirose S, Kosaka C, Masaki H, Masuda M, Takahashi H. Liquid chromatography mass spectrometric analysis of ouabainlike factor in biological fluid. Hypertens Res. 2000;23(Suppl):S21–S27. doi: 10.1291/hypres.23.supplement_s21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis LK, Yandle TG, Hilton PJ, Jensen BP, Begg EJ, Nicholls MG. Endogenous ouabain is not ouabain. Hypertension. 2014;64:680–683. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs BE, Liu Y, Pulina MV, Golovina VA, Hamlyn JM. Normal pregnancy: Mechanisms underlying the paradox of a ouabain-resistant state with elevated endogenous ouabain, suppressed arterial sodium calcium exchange, and low blood pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1317–H1329. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00532.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamlyn JM, Linde CI, Gao J, Huang BS, Golovina VA, Blaustein MP, Leenen FH. Neuroendocrine humoral and vascular components in the pressor pathway for brain angiotensin II: A new axis in long term blood pressure control. PloS One. 2014;9:e108916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baecher S, Kroiss M, Fassnacht M, Vogeser M. No endogenous ouabain is detectable in human plasma by ultra-sensitive UPLC-MS/MS. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;431:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaustein MP. Letter to the editor concerning Baecher et al. (Clin Chim Acta. 2014;431:87–92) Clin Chim Acta. 2015;448:248–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitzalis MV, Hamlyn JM, Messaggio E, Iacoviello M, Forleo C, Romito R, de Tommasi E, Rizzon P, Bianchi G, Manunta P. Independent and incremental prognostic value of endogenous ouabain in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Sanchez EP, Foecking MF, Sellers D, Blankenship MS, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Is the circulating ouabain-like compound ouabain? Am J Hypertens. 1994;7:647–650. doi: 10.1093/ajh/7.7.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogowski R, Tilva V, Tashko G, Liu Y, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Different carbon isotope ratios in endogenous ouabain from bovine adrenal glands and plant ouabain: Implications for the biosynthesis of endogenous cardiotonic steroids. Hypertension. 2009;54:e51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manunta P, Ferrandi M, Bianchi G, Hamlyn JM. Endogenous ouabain in cardiovascular function and disease. J Hypertens. 2009;27:9–18. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831cf2c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sophocleous A, Elmatzoglou I, Souvatzoglou A. Circulating endogenous digitalis-like factoRs) (EDLF) in man is derived from the adrenals and its secretion is ACTH-dependent. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:668–674. doi: 10.1007/BF03347027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laredo J, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Ouabain is secreted by bovine adrenocortical cells. Endocrinology. 1994;135:794–797. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.2.8033829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boulanger BR, Lilly MP, Hamlyn JM, Laredo J, Shurtleff D, Gann DS. Ouabain is secreted by the adrenal gland in awake dogs. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:E413–E419. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.264.3.E413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamlyn JM, Hamilton BP. Adrenal venous gradients for ouabain, aldosterone and cortisol in patients with adrenal dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;56:e69. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamlyn JM, Laredo J, Shah JR, Lu ZR, Hamilton BP. 11-hydroxylation in the biosynthesis of endogenous ouabain: Multiple implications. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;986:685–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada K, Goto A, Omata M. Modulation of the levels of ouabain-like compound by central catecholamine neurons in rats. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:67–69. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00078-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi H, Iyoda I, Takeda K, Sasaki S, Okajima H, Yamasaki H, Yoshimura M, Ijichi H. Centrally-induced vasopressor responses to sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase inhibitor, ouabain, may be mediated via angiotensin II in the anteroventral third ventricle in the brain. Jpn Circ J. 1984;48:1243–1250. doi: 10.1253/jcj.48.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi H, Yoshika M, Komiyama Y, Nishimura M. The central mechanism underlying hypertension: A review of the roles of sodium ions, epithelial sodium channels, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, oxidative stress and endogenous digitalis in the brain. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1147–1160. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balda MS, Pirola CJ, Dabsys SM, Finkielman S, Nahmod VE. Saralasin blocks the effect of angiotensin II and extracellular fluid saline expansion on the Na-K-ATPase inhibitor release in rats. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1986;8:997–1008. doi: 10.3109/10641968609044082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doursout MF, Chelly JE, Liang YY, Buckley JP. The ouabain-dependent Na+-K+ pump and the brain renin-angiotensin system. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1992;14:393–411. doi: 10.3109/10641969209036197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang BS, Ahmadi S, Ahmad M, White RA, Leenen FH. Central neuronal activation and pressor responses induced by circulating ang II: Role of the brain aldosterone-"ouabain" pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H422–H430. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00256.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leenen FH. The central role of the brain aldosterone-"ouabain" pathway in salt-sensitive hypertension. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:1132–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaustein MP, Leenen FH, Chen L, Golovina VA, Hamlyn JM, Pallone TL, Van Huysse JW, Zhang J, Wier WG. How NaCl raises blood pressure: A new paradigm for the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1031–H1049. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00899.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang BS, Huang X, Harmsen E, Leenen FH. Chronic central versus peripheral ouabain, blood pressure, and sympathetic activity in rats. Hypertension. 1994;23:1087–1090. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.6.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang BS, White RA, Ahmad M, Jeng AY, Leenen FH. Central infusion of aldosterone synthase inhibitor prevents sympathetic hyperactivity and hypertension by central Na+ in wistar rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R166–R172. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90352.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang BS, White RA, Ahmad M, Leenen FH. Role of brain corticosterone and aldosterone in central angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;62:564–571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dostanic I, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Theriault S, Van Huysse JW, Lingrel JB. The α2-isoform of Na-K-ATPase mediates ouabain-induced hypertension in mice and increased vascular contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H477–H485. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00083.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Huysse JW, Dostanic I, Lingrel JB, Hou X, Wu H. Hypertension from chronic central sodium chloride in mice is mediated by the ouabain-binding site on the Na,K-ATPase α2-isoform. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2147–H2153. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01216.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leenen FH, Hou X, Wang HW, Ahmad M. Enhanced expression of epithelial sodium channels causes salt-induced hypertension in mice through inhibition of the α2-isoform of Na+, K+-ATPase. Physiol Rep. 2015;3:e12383. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaustein MP, Chen L, Hamlyn JM, Leenen FHH, Lingrel JB, Wier WG, Zhang J. Pivotal role of α2 Na+ pumps and their high affinity ouabain binding site in cardiovascular health and disease. J Physiol. 2016 doi: 10.1113/JP272419. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wansapura AN, Lasko VM, Lingrel JB, Lorenz JN. Mice expressing ouabain-sensitive α1-Na,K-ATPase have increased susceptibility to pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H347–H355. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00625.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Lee MY, Cavalli M, Chen L, Berra-Romani R, Balke CW, Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Hamlyn JM, Iwamoto T, Lingrel JB, Matteson DR, Wier WG, Blaustein MP. Sodium pump α2 subunits control myogenic tone and blood pressure in mice. J Physiol. 2005;569:243–256. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.091801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berry RG, Despa S, Fuller W, Bers DM, Shattock MJ. Differential distribution and regulation of mouse cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase α1 and α2 subunits in T-tubule and surface sarcolemmal membranes. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang BS, Harmsen E, Yu H, Leenen FH. Brain ouabain-like activity and the sympathoexcitatory and pressor effects of central sodium in rats. Circ Res. 1992;71:1059–1066. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.5.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leenen FH, Harmsen E, Yu H, Ou C. Effects of dietary sodium on central and peripheral ouabain-like activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H2051–H2055. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang BS, Leenen FH. Brain "ouabain" and angiotensin II in salt-sensitive hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1996;28:1005–1012. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi H. Upregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-ouabain system in the brain is the core mechanism in the genesis of all types of hypertension. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:242786. doi: 10.1155/2012/242786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuroki MT, Guzman PA, Fink GD, Osborn JW. Time-dependent changes in autonomic control of splanchnic vascular resistance and heart rate in ANG II-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H763–H769. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00930.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laredo J, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Secretion of endogenous ouabain from bovine adrenocortical cells: Role of the zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:487–493. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ganong WF. Angiotensin II in the brain and pituitary: Contrasting roles in the regulation of adenohypophyseal secretion. Hormone Res. 1989;31:24–31. doi: 10.1159/000181082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pulina MV, Zulian A, Berra-Romani R, Beskina O, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Baryshnikov SG, Papparella I, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Golovina VA. Upregulation of Na+ and Ca2+ transporters in arterial smooth muscle from ouabain-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H263–H274. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00784.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zulian A, Linde CI, Pulina MV, Baryshnikov SG, Papparella I, Hamlyn JM, Golovina VA. Activation of c-SRC underlies the differential effects of ouabain and digoxin on Ca2+ signaling in arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C324–C333. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00337.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Blaustein MP, Hamlyn JM. Immuno-neutralization of endogenous ouabain lowers blood pressure in angiotensin II-dependent models. Hypertension. 2015;66(Suppl 1):AP145. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morton JJ, Wallace EC. The importance of the renin-angiotensin system in the development and maintenance of hypertension in the two-kidney one-clip hypertensive rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 1983;64:359–370. doi: 10.1042/cs0640359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baker PF, Blaustein MP, Hodgkin AL, Steinhardt RA. The influence of calcium on sodium efflux in squid axons. J Physiol. 1969;200:431–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Despa S, Lingrel JB, Bers DM. Na+/K+-ATPase α2-isoform preferentially modulates Ca2+ transients and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:480–486. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reuter H, Henderson SA, Han T, Ross RS, Goldhaber JI, Philipson KD. The Na+-Ca2+ exchanger is essential for the action of cardiac glycosides. Circ Res. 2002;90:305–308. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie Z, Askari A. Na+/K+-ATPase as a signal transducer. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:2434–2439. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lai F, Madan N, Ye Q, Duan Q, Li Z, Wang S, Si S, Xie Z. Identification of a mutant α1 Na/K-ATPase that pumps but is defective in signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13295–13304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity and biased receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:296–302. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manunta P, Hamilton J, Rogowski AC, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Chronic hypertension induced by ouabain but not digoxin in the rat: Antihypertensive effect of digoxin and digitoxin. Hypertens Res. 2000;23(Suppl):S77–S85. doi: 10.1291/hypres.23.supplement_s77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura K, Manunta P, Hamilton BP, Hamlyn JM. Different effects of in vivo ouabain and digoxin on renal artery function and blood pressure in the rat. Hypertens Res. 2000;23(Suppl):S67–S76. doi: 10.1291/hypres.23.supplement_s67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang BS, Kudlac M, Kumarathasan R, Leenen FH. Digoxin prevents ouabain and high salt intake-induced hypertension in rats with sinoaortic denervation. Hypertension. 1999;34:733–738. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nesher M, Shpolansky U, Viola N, Dvela M, Buzaglo N, Ben-Ami HC, Rosen H, Lichtstein D. Ouabain attenuates cardiotoxicity induced by other cardiac steroids. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song H, Karashima E, Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP. Ouabain-digoxin antagonism in rat arteries and neurones. J Physiol. 2014;592:941–969. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.266866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrari P, Torielli L, Ferrandi M, Padoani G, Duzzi L, Florio M, Conti F, Melloni P, Vesci L, Corsico N, Bianchi G. PST2238: A new antihypertensive compound that antagonizes the long-term pressor effect of ouabain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferrandi M, Molinari I, Barassi P, Minotti E, Bianchi G, Ferrari P. Organ hypertrophic signaling within caveolae membrane subdomains triggered by ouabain and antagonized by PST 2238. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33306–33314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staessen JA, Thijs L, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, et al. Main results of the ouabain and adducin for specific intervention on sodium in hypertension trial (OASIS-HT): A randomized placebo-controlled phase-2 dose-finding study of rostafuroxin. Trials. 2011;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lanzani C, Citterio L, Glorioso N, et al. Adducin- and ouabain-related gene variants predict the antihypertensive activity of rostafuroxin, part 2: Clinical studies. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:59ra87. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song H, Thompson SM, Blaustein MP. Nanomolar ouabain augments Ca2+ signalling in rat hippocampal neurones and glia. J Physiol. 2013;591:1671–1689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuan CM, Manunta P, Hamlyn JM, Chen S, Bohen E, Yeun J, Haddy FJ, Pamnani MB. Long-term ouabain administration produces hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 1993;22:178–187. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghadhanfar E, Al-Bader M, Turcani M. Wistar rats resistant to the hypertensive effects of ouabain exhibit enhanced cardiac vagal activity and elevated plasma levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide. PloS One. 2014;9:e108909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamlyn JM, Takata T, Manunta P, Hamilton J, Kramer R, Hamilton BP. New strains of rats for cardiovascular research: Sensitivity and resistance to ouabain induced hypertension. Abst. 7th Eur Meet Hypertens. 1995:78. Abst. 332. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ozdemir A, Sahan G, Demirtas A, Aypar E, Gozubuyuk G, Turan NN, Ark M. Chronic ouabain treatment induces Rho kinase activation. Arch Pharm Res. 2015;38:1897–1905. doi: 10.1007/s12272-015-0597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dahl LK, Heine M, Tassinari L. Effects of chronic excess salt ingestion. Role of genetic factors in both DOCA-salt and renal hypertension. J Exp Med. 1963;118:605–617. doi: 10.1084/jem.118.4.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ben-Ishay D, Saliternik R, Welner A. Separation of two strains of rats with inbred dissimilar sensitivity to DOCA-salt hypertension. Experientia. 1972;28:1321–1322. doi: 10.1007/BF01965321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aileru AA, De Albuquerque A, Hamlyn JM, Manunta P, Shah JR, Hamilton MJ, Weinreich D. Synaptic plasticity in sympathetic ganglia from acquired and inherited forms of ouabain-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol. Regul, Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R635–R644. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.2.R635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hansson JH, Nelson-Williams C, Suzuki H, Schild L, Shimkets R, Lu Y, Canessa C, Iwasaki T, Rossier B, Lifton RP. Hypertension caused by a truncated epithelial sodium channel gamma subunit: Genetic heterogeneity of liddle syndrome. Nat Genet. 1995;11:76–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shi PP, Cao XR, Sweezer EM, Kinney TS, Williams NR, Husted RF, Nair R, Weiss RM, Williamson RA, Sigmund CD, Snyder PM, Staub O, Stokes JB, Yang B. Salt-sensitive hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in mice deficient in the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. Am J Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F462–F470. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90300.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Huysse JW, Amin MS, Yang B, Leenen FH. Salt-induced hypertension in a mouse model of liddle syndrome is mediated by epithelial sodium channels in the brain. Hypertension. 2012;60:691–696. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lingrel JB. The physiological significance of the cardiotonic steroid/ouabain-binding site of the Na,K-ATPase. Ann Rev Physiol. 2010;72:395–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dostanic-Larson I, Van Huysse JW, Lorenz JN, Lingrel JB. The highly conserved cardiac glycoside binding site of Na,K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15845–15850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507358102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krep H, Price DA, Soszynski P, Tao QF, Graves SW, Hollenberg NK. Volume sensitive hypertension and the digoxin-like factor. Reversal by a Fab directed against digoxin in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:921–927. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00181-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaide J, Ura N, Torii T, Nakagawa M, Takada T, Shimamoto K. Effects of digoxin-specific antibody fab fragment (digibind) on blood pressure and renal water-sodium metabolism in 5/6 reduced renal mass hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:611–619. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tkachenko O, Shchekochikhin D, Schrier RW. Hormones and hemodynamics in pregnancy. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:e14098. doi: 10.5812/ijem.14098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Puschett JB. The role of excessive volume expansion in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santillan MK, Santillan DA, Scroggins SM, Min JY, Sandgren JA, Pearson NA, Leslie KK, Hunter SK, Zamba GK, Gibson-Corley KN, Grobe JL. Vasopressin in preeclampsia: A novel very early human pregnancy biomarker and clinically relevant mouse model. Hypertension. 2014;64:852–859. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yeung EH, Liu A, Mills JL, Zhang C, Mannisto T, Lu Z, Tsai MY, Mendola P. Increased levels of copeptin before clinical diagnosis of preelcampsia. Hypertension. 2014;64:1362–1367. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP. Sodium chloride, extracellular fluid volume, and blood pressure regulation. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:F563–F575. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.4.F563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vakkuri O, Arnason SS, Pouta A, Vuolteenaho O, Leppaluoto J. Radioimmunoassay of plasma ouabain in healthy and pregnant individuals. J Endocrinol. 2000;165:669–677. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Linde CI, Antos LK, Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Nanomolar ouabain increases NCX1 expression and enhances Ca2+ signaling in human arterial myocytes: A mechanism that links salt to increased vascular resistance? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H784–H794. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00399.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pulina MV, Zulian A, Baryshnikov SG, Linde CI, Karashima E, Hamlyn JM, Ferrari P, Blaustein MP, Golovina VA. Cross talk between plasma membrane Na+/Ca2+ exchanger-1 and TRPC/Orai-containing channels: Key players in arterial hypertension. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;961:365–374. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4756-6_31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oshiro N, Dostanic-Larson I, Neumann JC, Lingrel JB. The ouabain-binding site of the α2 isoform of Na,K-ATPase plays a role in blood pressure regulation during pregnancy. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1279–1285. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Delva P, Capra C, Degan M, Minuz P, Covi G, Milan L, Steele A, Lechi A. High plasma levels of a ouabain-like factor in normal pregnancy and in pre-eclampsia. Eur J Clin Invest. 1989;19:95–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1989.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gregoire I, Roth D, Siegenthaler G, Fievet P, el Esper N, Favre H, Fournier A. A ouabain-displacing factor in normal pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond) 1988;74:307–310. doi: 10.1042/cs0740307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rana S, Rajakumar A, Geahchan C, Salahuddin S, Cerdeira AS, Burke SD, George EM, Granger JP, Karumanchi SA. Ouabain inhibits placental sFlt1 production by repressing HSP27-dependent HIF-1α pathway. FASEB J. 2014;28:4324–4334. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-252684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dvela-Levitt M, Cohen-Ben Ami H, Rosen H, Ornoy A, Hochner-Celnikier D, Granat M, Lichtstein D. Reduction in maternal circulating ouabain impairs offspring growth and kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:1103–1114. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li J, Khodus GR, Kruusmagi M, Kamali-Zare P, Liu XL, Eklof AC, Zelenin S, Brismar H, Aperia A. Ouabain protects against adverse developmental programming of the kidney. Nat Commun. 2010;1:42. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bignami E, Casamassima N, Frati E, Lanzani C, Corno L, Alfieri O, Gottlieb S, Simonini M, Shah KB, Mizzi A, Messaggio E, Zangrillo A, Ferrandi M, Ferrari P, Bianchi G, Hamlyn JM, Manunta P. Preoperative endogenous ouabain predicts acute kidney injury in cardiac surgery patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:744–755. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182741599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simonini M, Lanzani C, Bignami E, Casamassima N, Frati E, Meroni R, Messaggio E, Alfieri O, Hamlyn J, Body SC, Collard CD, Zangrillo A, Manunta P. A new clinical multivariable model that predicts postoperative acute kidney injury: Impact of endogenous ouabain. Nephrol, Dial, Transplant. 2014;29:1696–1701. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hamlyn JM, Manunta P. Endogenous cardiotonic steroids in kidney failure: A review and an hypothesis. Adv Chron Kidney Dis. 2015;22:232–244. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pavlovic D. The role of cardiotonic steroids in the pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy in chronic kidney disease. Nephron. Clin Pract. 2014;128:11–21. doi: 10.1159/000363301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pavlovic D, Aksentijevic D, Seymour A-ML, Fuller W, Shattock MJ. A soluble inhibitor depresses Na/K ATPase activity in cardiomyopathic hearts from uremic rats. Circulation. 2010;122:A16016. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Simonini M, Pozzoli S, Bignami E, Casamassima N, Messaggio E, Lanzani C, Frati E, Botticelli IM, Rotatori F, Alfieri O, Zangrillo A, Manunta P. Endogenous ouabain: An old cardiotonic steroid as a new biomarker of heart failure and a predictor of mortality after cardiac surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:714793. doi: 10.1155/2015/714793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.