Abstract

Engaging patients in a group-based weight loss program is a challenge for the acute-care hospital outpatient setting. To evaluate the feasibility, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a telephone-based weight loss service and an existing face-to-face, group-based service a non-randomised, two-arm feasibility trial was used. Patients who declined a two-month existing outpatient group-based program were offered a six-month research-based telephone program. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, two months (both groups) and six months (telephone program only) using paired t tests and linear regression models. Cost per healthy life year gained was calculated for both programs. The telephone program achieved significant weight loss (−4.1 ± 5.0 %; p = 0.001) for completers (n = 35; 57 % of enrolees) at six months. Compared to the group-based program (n = 33 completers; 66 %), the telephone program was associated with greater weight loss (mean difference [95%CI] −2.0 % [−3.4, −0.6]; p = 0.007) at two months. The cost per healthy life year gained was $33,000 and $85,000, for the telephone and group program, respectively. Telephone-delivered weight management services may be effective and cost-effective within an acute-care hospital setting, likely more so than usual (group-based) care.

Keywords: Obesity, Physical activity, Diet, Translation research, Weight loss, Lifestyle intervention

INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity are a significant population health problem [1]. Obesity is a risk factor for developing and worsening of a number of chronic conditions such as hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes and some cancers [2], and contributes to approximately 10 % of total health care costs in developed countries [3]. Obesity is also reflected in hospital admissions across developed countries where it is estimated that 20–30 % of patients admitted to hospital are obese [4–7].

In Australia, acute care hospitals offer outpatient weight management services delivered as group-based programs [8] consistent with the broader evidence on delivery of weight loss interventions [9]. Although such weight loss programs are effective at achieving significant weight loss in a proportion of patients, their uptake is generally low, limiting their impact [10].

Telephone-delivery of weight loss services has the potential to provide broad reach and the repeated contacts necessary to promote successful behaviour change and weight loss [8, 11, 12]. Several randomised controlled trials have investigated the use of telephone-only delivery to target weight loss in patients recruited from primary care settings, including adults with no or very few comorbidities other than overweight or obesity [13–18]. These trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of telephone delivery for improvement in diet and physical activity behaviours, and weight loss in a controlled research context. To date, dissemination efforts for weight loss programs have primarily been for face-to-face delivered programs [19]. However, four recent studies have evaluated telephone-delivered lifestyle-based weight loss services implemented in broader dissemination contexts for a state-wide population [20], for overweight and obese primary care patients in a community catchment area [21], for patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation services in rural and urban Australia [22] and for patients previously hospitalised with coronary heart disease [23]. These services have shown significant weight loss outcomes (ranging from −1.3 to −5.4 kg over 6 to 12 months) and behaviour change outcomes approximating those reported in the precursor randomised trials [20, 22–24]. Such interventions may also be appropriate for the large number of hospital patients identified as requiring outpatient weight management services.

This study was conducted primarily to determine whether an evidence-based, telephone-delivered weight loss program (telephone program) for overweight and obese patients was feasible, effective (primary outcome of weight loss) and cost-effective when implemented in an applied, acute-care hospital outpatient setting, to patients who declined the existing service (a face-to-face, group-based program). As a secondary aim, the telephone program was compared to the existing group-based program for contextual purposes. Primary outcomes were feasibility (reach, retention, patient characteristics and implementation), effectiveness for weight loss, and cost-effectiveness. Secondary effectiveness outcomes were waist circumference and lifestyle behaviours that underpin weight change.

METHODS

Study design

A non-randomised, two-arm pre-post feasibility study was conducted primarily to evaluate the 6-month telephone program and, secondarily, to compare the telephone program to the existing two-month group-based program. Such non-randomised study designs are common in translational research [24–26].There is already a considerable amount of evidence supporting the efficacy of telephone-delivered lifestyle interventions at achieving weight loss in controlled research settings [27]. The purpose of this study was to determine whether an evidence-based telephone program was feasible and effective when implemented in a ‘real-world’ hospital outpatient setting for patients who had already declined usual care, with the group-based program providing comparison to the existing service. Data were collected between November 2011 and March 2013. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committees of The University of Queensland and the Princess Alexandra Hospital in accordance with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s guidelines. All participants provided written consent.

Patient recruitment

Patients considered for recruitment into the telephone program and group-based program were those referred for dietetic outpatient weight management services at a large acute-care hospital in Brisbane, Australia. Consistent with current service delivery, all patients referred for weight loss from a variety of health practitioners in the hospital were mailed a letter of invitation for the established group-based program, asking patients to contact the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics if they were interested in participating. Patients who had declined or not responded to the invitation were then invited to participate in the telephone program and screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria for the telephone program were body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2, age <80 years, no use of prescription weight loss drugs, no previous weight loss surgery, no current cancer treatment, not pregnant or breastfeeding, no contraindications to participation in unsupervised exercise or a weight loss program, access to a telephone and sufficient English to complete phone calls. Patients referred for outpatient weight loss service from November 2011 to February 2013 and who agreed to participate in the group-based program were invited to consent to the use of their data in the study. The only eligibility criterion for participants in the group-based program was a BMI ≥25 kg/m2.

Study groups

It is important to note that the telephone program (six months; up to 16 calls) and group-based program (eight weeks; eight sessions) are two distinct weight loss intervention delivery models, not equated for duration or number of contacts, but are similar in terms of intervention targets and counselling approach. A six-month intervention was provided for the telephone program, consistent with guidelines to achieve maximal weight loss and increase the likelihood of weight loss maintenance [28].

Telephone program

The telephone program is based on current evidence for weight loss initiation and clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity, and uses a combined approach of reducing energy intake, increasing physical activity and behavioural therapy [28, 29]. Patients received individualised telephone support involving eight weekly telephone calls for the first two months and fortnightly calls for the remaining four months (up to 16 calls over six months). Counsellors used a motivational interviewing approach to deliver the program [30, 31]. Patients were provided with a workbook on weight loss, physical activity, healthy eating and behaviour change strategies derived from Social Cognitive Theory [32] including goal setting, self-monitoring, social support, problem solving and relapse prevention. Additionally, they received a diary to record weekly goals, dietary intake, physical activity and weight, The CalorieKing Calorie, Fat and Carbohydrate Counter 2011 [33] to calculate energy intake, and a pedometer (Yamax Digi-walker SW700, San Antonio, USA) to self-monitor physical activity.

Patients were encouraged to achieve 5 % of initial body weight loss [29] over six months by increasing physical activity (aiming for at least 30 min/day) [34] and reducing dietary energy intake by 2000 kJ/day from estimated energy requirements based on gender, weight and age (between 5000 and 7500 kJ/day) [35]. Patients capable of higher activity levels were encouraged to gradually progress to at least 60 min/day of physical activity [36], and all were encouraged to increase incidental activity [37]. Individualised advice to reduce energy intake was given, and a fibre intake of 25 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men was encouraged [38], as was a reduced fat diet (total fat < 30 % energy intake; saturated fat intake <7 % energy intake) [36]. Counsellors were Accredited Practising Dietitians (with at least bachelor level training in nutrition and dietetics). They received one-day training by the investigators on the motivational interviewing approach [30], intervention procedures and study protocols. Weekly contact between counsellors and investigators, and intervention checklists were used to promote fidelity of implementation. Where possible, the same telephone counsellor remained with patients for the intervention duration to facilitate continuity of care.

Group-based program

The group-based program was delivered as per routine practice. The group-based program was adapted from a previously evaluated group-based program [8] and supported patients to self-manage weight loss through reducing energy intake, increasing physical activity and behavioural therapy. It involved eight free of charge, two-hour sessions held at the hospital where patients attended the same group each week, with capacity to accommodate 12 patients per session. Discussion topics included getting ready for change, healthy eating, a supermarket tour, emotional eating, mindful eating, identifying barriers to change, physical activity and exercise. Similar to the telephone-based service, a motivational interviewing [31] counselling approach was used, and behaviour change strategies were derived from Social Cognitive Theory [32]. Upon completion, patients were offered monthly review with a dietitian.

Patients were encouraged to achieve 5 % of initial body weight loss [29] by reducing dietary energy intake (aiming for a reduction by 2000 kJ/day) [29, 39] and increasing physical activity (aiming for 20–30 min/day on 3–4 days of the week plus incidental exercise). Seven of the eight sessions were co-facilitated by an Accredited Practicing Dietitian and a clinical psychologist. A physiotherapist facilitated one session. A comprehensive program manual was used to ensure fidelity of program delivery.

Data collection and outcome measures

Assessments for both groups took place at the hospital at baseline to capture the start of the programs, two months to capture the end of the group-based program and end of the intensive phase of the telephone program, with the telephone group also followed up at six months (end of program). Patients in the telephone program completed a questionnaire followed by anthropometric measurements taken by the study counsellors (height, weight and waist circumference). All anthropometric measurements for the telephone program were an average of two measurements. Patients in the group-based program had height, weight and waist measurements taken by the dietitian who facilitated the program and received questionnaires to complete and post back. For the group-based program, anthropometric measurements were taken only once as the program was assessed as per routine practice.

Primary outcomes

Feasibility

Reach, retention and characteristics of patients in both groups were measured by collecting information on recruitment, attrition (including reasons for dropout) and patient demographic characteristics through a self-administered questionnaire. Implementation was measured by recording call completion and call duration for the telephone program. At the end of program assessment, participants in the telephone program were asked to rate the program on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 ‘not helpful at all’ to 5 ‘extremely helpful’, and adverse events were assessed by asking about the occurrence of new health problems. For the group-based program, implementation was measured by recording the numbers of sessions attended.

Weight loss

Weight was measured in light clothing, without shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg on calibrated scales.

Program delivery cost per healthy life year gained

Costs to deliver each program were systematically recorded throughout the study in 2012 Australian dollars. Included in the cost evaluation were the program materials (handouts, workbook, tracking diary, pedometer and calorie counter), cost of program calls and the cost of counsellor time. Payroll information was used to assess wage rates for program staff, and the standard rate for on-costs (23 %) was added, a proportion of which accounted for related infrastructure (office space, telephones and computers). The number of patients included for costing delivery of the group-based program was based on the total number of patients who took part in the groups, not just those who consented to use of data in this study (weight change was thus also based on that observed in the total number of group-based program participants).

Secondary outcomes

Waist circumference in the telephone group was measured at the superior border of the iliac crest at the end of a normal expiration (to the nearest 0.5 cm). For the group-based program, waist circumference was measured halfway between the lowest rib and superior border of the iliac crest.

Physical activity was assessed using two items from the US National Health Interview Survey about total time spent walking for exercise in the past week. These items have been shown to be as responsive as more detailed physical activity instruments [40]. Physical activity was measured objectively in the telephone program only using accelerometers (Actigraph GT3X+, Florida, USA). Accelerometers were fitted around the waist, positioned on the right mid-axillary line and worn during all waking hours for seven consecutive days. The accelerometers were downloaded in 60-second epochs using Actilife 6.0 [41]. Using SAS version 9.2 [42], moderate to vigorous activity (MVPA) was identified as mean time spent at ≥1952 counts per minute (cpm) [43] on valid days (i.e., ≥10 h of wear). Wear time was estimated as all time except bouts of 60 min or longer of zero cpm (with allowance for up to two counts 1–49 cpm) [44]. A sensitivity analysis using different cut-points (lower [45] and higher [25]) to describe MVPA intensity was also performed to evaluate the sensitivity of conclusions to assumptions of different count cut-points.

Dietary intake was measured using the Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire (FFBQ), a 20-item questionnaire that assesses behaviours related to fat and fibre intake [46]. The questionnaire yields a Total Index, Fat Index and Fibre Index that are scored from 1 to 5, with higher numbers indicating better dietary behaviours. The first two items are valid and reliable measures of fruit and vegetable intake [47] which were reported separately as well as contributing to the fibre and total indices.

Sample size

With an anticipated 30 % attrition, and assuming standard deviations from previous literature [46, 48], an estimated sample size of approximately 50 participants in the telephone program was expected to provide adequate power to detect within-group changes (with 5 % significance, two-tailed) meeting the minimum differences of interest (MDI) for most outcomes: >90 % power for weight loss (MDI = 5 % or 5 kg [28, 29], assumed standard deviation = 4.9 kg [48]); ≥80 % power for waist circumference (MDI = 4 cm), MVPA (MDI = 60 min/week), fruit intake (MDI = 0.5 serves/day), vegetable intake (MDI = 1 serve/day) and FFBQ indices (MDI = 0.2); and <80 % power only for walking for exercise (MDI = 75 min/week) [46, 48].

Data analysis

Data analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 21) (New York, USA) and STATA (version 12) (Texas, USA). All data were normally distributed. Significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). As the interventions were not randomly allocated, baseline characteristics of the telephone program and the group-based program participants were compared statistically. Characteristics of two- and six-month completers versus dropouts were also compared. Independent t tests were used for continuous variables (normal) or chi-square tests for categorical variables.

All change outcomes approximated a normal distribution. Within-group changes in the telephone program (baseline to two months; baseline to six months) and the group-based program (baseline to two months) were assessed using paired t tests. Differences in outcomes between the telephone program and group-based program from baseline to two months were evaluated using linear regression models. These were adjusted for baseline value of the outcome variable and for potential confounders. Potential confounders (baseline values of the other outcomes and demographic variables) were adjusted for in the analyses if their association with the outcome was p < 0.2 [49, 50]. Results were reported primarily for completers, consistent with other evaluations of weight loss interventions in service delivery contexts [20, 24]. A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation was performed to evaluate the sensitivity of conclusions to assumptions regarding missing data. Conclusions were considered sensitive to missing data assumptions when the discrepancy between completers and multiple imputation estimates amounted to >20 %. Multiple imputation (MI) was performed by chained equations, with 20 imputations. Imputation models included all variables in the regression models and auxiliary variables to improve the prediction of missing covariates.

Cost-effectiveness

To estimate the cost per healthy life-year gained, methods developed for the ‘Assessing Cost-Effectiveness in Prevention’ project were used [51]. A full description of the approach was published previously [52]. Briefly, a multi-cohort multistate life table model [53] was populated with data on the 2003 Australian population with regard to body mass index and epidemiology of obesity-related diseases. The model compared the expected number of health-adjusted years of life lived between an intervention scenario and a business-as-usual scenario. Costing took a health sector perspective. The cost evaluation excluded research or assessment components of the programs and did not include costs incurred by participants (i.e. travel, parking, time). Intervention costs were partly offset by prevented health care costs in later life, inflated to 2012 values [54]. Health effects and costs were discounted at 3 % per year. Weight loss was assumed to reach its maximum at six months into the intervention, after which all weight was gradually regained [55]. The model was implemented in MS Excel, with add-in program Ersatz (www.epigear.com) for Monte Carlo analysis (2000 iterations) to assess uncertainty in effect-size, rate of weight regain and risk of disease.

RESULTS

Reach, retention and patient characteristics

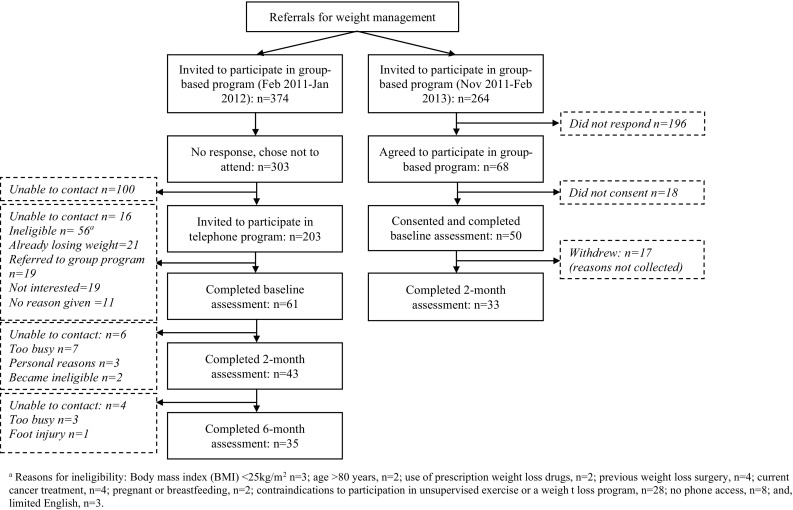

Attempts were made to contact a total of 303 patients referred for weight loss who did not access the group-based program (Fig. 1). Of those attempts, 33 % (n = 100) were unable to be contacted (unanswered calls or disconnected numbers) and 19 % (n = 56) were ineligible. From the patients who were contacted and eligible (n = 147), 61 (45 %) consented to participate and commenced the telephone service (20 % of original sample). Reasons for not participating were already losing weight and did not require the service, requesting referral back to the group-based program, or not interested. Of the 61 patients who started the telephone program, 71 % (n = 43) completed the 2-month assessment, and 57 % (n = 35) completed the 6-month assessment.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment flowchart for the telephone program and group-based program

For the group-based program, 264 patients were referred for weight loss services, of which 68 (26 % of referrals) commenced the program (across 10 groups), and 50 patients (74 % of group participants) consented to use of their data in this study. Of the 50 patients who consented, 66 % (n = 33) completed the 2-month assessment. Recruitment and retention of patients in both groups are shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline characteristics of the telephone program patients compared to those in the group-based program are shown in Table 1. Compared with patients in the group-based program, patients in the telephone program were significantly younger (p < 0.001), more likely to be in paid employment (p < 0.001), with fewer co-morbidities (p = 0.011) and a relatively higher income (p < 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between completers and non-completers in either program.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the telephone program and group-based program

| Patient characteristics | Telephone programa | Group-based programb | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=61) | (n=50) | ||

| Female | 28 (46.0 %) | 26 (60.5 %) | .206 |

| Age (years) | 49.3 ± 12.0 | 57.4 ± 13.5 | .000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 37.3 ± 7.2 | 39.1 ± 7.6 | .201 |

| Caucasian | 57 (93.4 %) | 35 (81.4 %) | .306 |

| Married/living together | 42 (68.9 %) | 21 (48.8 %) | .079 |

| MVPA, min/day | 20.6 ± 17.7 | – | – |

| Walking, min/week | 56.0 ± 102.5 | 120.8 ± 181.0 | .049 |

| Fruit intake, serves/day | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | .001 |

| Vegetable intake, serves/day | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | .005 |

| FFBQ Fat Index | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | .137 |

| FFBQ Fibre Index | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | .315 |

| FFBQ Total Index | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | .227 |

| Education | |||

| ≤Primary school | 7 (11.5 %) | 5 (11.9 %) | .848 |

| Grade 10 or grade 12 | 23 (37.7 %) | 18 (42.9 %) | |

| Trade or university degree | 31 (50.8 %) | 19 (45.2 %) | |

| Employment | |||

| Paid employment | 40 (65.6 %) | 9 (20.9 %) | .000 |

| Retired | 5 (8.2 %) | 14 (32.6 %) | |

| Student, unemployed | 16 (26.2 %) | 20 (46.5 %) | |

| Income | |||

| <$540/week–1007/weekc | 22 (36.1 %) | 28 (65.1 %) | .000 |

| $1008 ≥ $2391/weekd | 26 (42.6 %) | 3 (7.0 %) | |

| Unsure/prefer not to answer | 13 (21.3 %) | 12 (27.9 %) | |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| 0–1 | 27 (44.3 %) | 7 (16.3 %) | .011 |

| 2–3 | 24 (37.7 %) | 25 (58.1 %) | |

| 4+ | 11 (18.0 %) | 11 (25.6 %) | |

Data presented as mean ± SD or n (%). Income is based on population quintiles for Australian distribution of income.

BMI body mass index, MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity, FFBQ Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire, higher FFBQ scores = better dietary behaviour

a n = 55 for MVPA, min/day; n = 60 for FFBQ fat index; n = 54 for FFBQ fibre index, FFBQ total index

b n = 43 for ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, income and comorbidities; n = 38 for walking, FFBQ fat index; n = 39 for fruit intake, vegetable intake; n = 36 for FFBQ fibre index, FFBQ total index

cRepresents lowest two categories for population quintiles for Australian distribution of income

dRepresents highest three categories for population quintiles for Australian distribution

Implementation

Among the 35 telephone program patients who completed the program (57 % of enrolees), counselling call completion ranged from 11 to all 16 calls, most (n = 32, 91 %) completed ≥12 calls with a mean (±SD) of 14 (±2) calls completed. Call duration ranged from 19 to 38 min and averaged 27 min (±5). Overall, the telephone service was rated ‘helpful’ or ‘very helpful’ by 86 % (n = 30) of completers. Those who completed the group-based program (n = 33) attended five to eight sessions, mostly (n = 31, 94 %) attended ≥six sessions and had a mean attendance of seven (±1) sessions. Non-serious and unrelated adverse events were reported for two patients in the telephone program.

Weight loss

Weight loss and changes in secondary outcomes for the telephone program and group-based program are shown in Table 2. Completers analysis showed that patients in the telephone program achieved statistically significant weight loss from baseline to two months (−2.9 ± 3.4 %; p < 0.001) initial body weight) and baseline to six months (−4.1 ± 5.1 %; p = 0.001). Patients in the group-based program achieved small, statistically significant weight loss from baseline to two months (−1.1 ± 2.2 %; p = 0.012; Table 2), with no data available for the group-based program at six months. Telephone program patients lost significantly more weight at two months than group-based program patients (mean difference [95%CI] −2.0 % [−3.4, −0.6]; p = 0.007). Estimates obtained via MI and completers analysis were similar (±20 %) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mean within-group changes (95 % CI) from baseline in study outcomes among telephone program and group-based program patients

| Completers | Multiple imputationa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone | Group | Telephone | Group | |||

| ∆2 monthsb | ∆6 monthsc | ∆2 monthsd | ∆2 months | ∆6 months | ∆2 months | |

| n | 43 | 35 | 33 | 61 | 61 | 50 |

| Weight, kg | −3.0 (−4.2, −1.9)* | −4.1 (−6.5, −1.6)* | −1.2 (−1.9, −0.5)* | −3.1 (−4.7, −1.6)* | −3.8 (−5.6, −2.0)* | −1.2 (−1.8, −0.5)* |

| Waist circumference, cm | −2.6 (−4.0, −1.3)* | −4.5 (−6.6, −2.4)* | −2.3 (−4.3, −0.3)* | −2.9 (−4.4, −1.4)* | −4.8 (−6.1, −2.9)* | −2.6 (−4.5, −0.7)* |

| MVPA, min/day | 1.5 (−3.7, 6.7) | 2.1 (−2.7, 6.9) | n/a | 1.4 (−4.2, 7.0) | 1.4 (−4.0, 6.7) | n/a |

| Walking, min/week | 76.7 41.5, 112.0)* | 56.0 (3.4, 108.6)* | 11.4 (−41.8, 64.5) | 81.0 (40.8, 121.3)* | 56.4 (3.4, 109.4)* | 10.8 (−50.8, 72.4) |

| Fruit intake, serves/day | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8)* | 0.3 (0.0, 0.6)* | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.1) | 0.6 (0.3, 0.9)* | 0.3 (−0.1, 0.6) | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.0) |

| Vegetable intake, serves/day | 0.6 (0.2, 0.9)* | 0.8 (0.3, 1.3)* | 0.5 (−0.2, 1.1) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.1)* | 0.7 (0.1, 1.3)* | 0.4 (−0.3, 1.1) |

| FFBQ Fat Index (1–5) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6)* | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5)* | 0.5 (0.3, 0.6)* | 0.4 (0.2, 0.5)* | 0.3 (0.2, 0.5)* | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7)* |

| FFBQ Fibre Index (1–5) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.2 (−0.0, 0.4) | 0.2 (−0.1, 0.4) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.0, 0.4)* | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4) |

| FFBQ Total Index (1–5) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4)* | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4)* | 0.4 (0.2, 0.5)* | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4)* | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5)* | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5)* |

Data from paired t tests, presented as mean (95 % CI)

MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity, FFBQ Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire, higher FFBQ scores = better dietary behaviour

*Significant within-group change from baseline, p < 0.05

aMultiple Imputation = 20 imputations by chained equations

bMVPA n = 39; FFBQ Fibre Index, FFBQ Total Index n = 34

cMVPA n = 27

dWeight n = 31; waist circumference, fruit intake, vegetable intake, FFBQ Fibre Index, FFBQ Total Index, walking n = 26; FFBQ Fat Index n = 28

Table 3.

Mean between-group difference (95 % CI) in study outcomes for telephone program and group-based program at two months, adjusted for confounders

| Completersa | p value | Multiple imputationb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95 % CI) | Mean difference (95 % CI) | |||

| Weight (kg) | −2.0 (−3.4, −0.6) | .007 | −2.2 (−3.5, −0.9) | .002 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | −0.3 (−2.9, 2.2) | .808 | −0.2 (−2.2, 1.8) | .836 |

| Walking (min/week) | 73.1 (17.4, 128.7) | .011 | 73.6 (14.6, 132.5) | .016 |

| Fruit (serves/day) | 0.6 (0.1, 1.0) | .009 | 0.5 (0.1, 0.9) | .012 |

| Vegetables (serves/day) | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.6) | .823 | 0.01 (−0.7, 0.7) | .966 |

| FFBQ Fat Index (1–5) | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | .068 | −0.2 (−0.4, −0.0) | .034 |

| FFBQ Fibre Index (1–5) | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) | .102 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) | .213 |

| FFBQ Total Index (1–5) | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.0) | .110 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.0) | .088 |

All models adjust for baseline values. Additionally, models adjust for smoking (weight); self-reported physical activity, smoking, weight loss attempt over previous 6 months (waist circumference); education, heart condition, weight loss attempt over previous 6 months (walking for exercise); BMI, self-reported physical activity, education, employment, heart condition, musculoskeletal condition (fruit intake); BMI, ethnicity, heart condition (vegetable intake); age, BMI, heart condition, mental illness (FFBQ fat); previously diagnosed cancer (FFBQ Fibre); previously diagnosed cancer, heart condition (FFBQ Total).

FFBQ Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire

aTelephone program n = 43. Group-based program: weight n = 31; waist circumference, walking, fruit intake, vegetable intake, FFBQ Fibre Index, FFBQ Total Index n = 26, FFBQ Fat Index n = 28

bMultiple Imputation using 20 imputations by chained equations. Telephone program n = 61, group-based program n = 50

Secondary outcomes

Those who completed the telephone program achieved significant changes at two months for waist circumference (p < 0.001), self-reported walking for exercise (p < 0.001), fruit intake (p = 0.001), vegetable intake (p = 0.002), and the FFBQ Fat Index (p < 0.001) and Total Index (p < 0.001), but not for objectively measured physical activity (p = 0.580) or FFBQ Fibre Index (p = 0.449) (Table 2). The same pattern of results was seen at six months. The use of varying cut points for calculating MVPA intensity did not impact conclusions for objectively measured physical activity. Those in the group-based program achieved significant improvements for waist circumference (p = 0.028), and FFBQ Fat (p < 0.001) and Total Index (p < 0.001; Table 2). Most results did not vary (±20 %) between completers and MI analyses. In the telephone program, significantly greater improvements in self-reported physical activity and fruit intake, compared to the group-based program, were observed in both completers and MI analyses (all p < 0.05; Table 3).

Program delivery cost per healthy life-year

The cost per healthy life-year gained was $33,000 (95 % uncertainty interval 14,000–100,000) for the telephone intervention and $85,000 (95 % UI 27,000–infinite) for the group-based program.

DISCUSSION

Accessible and effective models of weight management service delivery are needed to address the growing burden of obesity. This study assessed the feasibility, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a telephone-delivered weight loss service implemented in an acute-care hospital outpatient setting. Overall, the telephone program engaged with a different demographic of patient and produced successful weight loss and improvements in health behaviours. Weight loss was significantly greater than that observed in the existing group-based program.

Of particular interest is the considerable difference in demographic characteristics between the telephone program and the group-based program patients, indicating that each service delivery model attracted a different type of patient group. Telephone program patients were younger and more likely in paid employment than the group-based program patients possibly due to difficulties attending the face-to-face group-based sessions offered during working hours. The group-based program had a higher proportion of patients living with multiple co-morbidities than the telephone program. Although not statistically different, the telephone program (offered to non-attendees of the group-based program) tended to attract more males than the group-based program in the hospital setting. This is interesting as research and disseminated traditional lifestyle behaviour interventions tend to be under-represented by males [20, 24, 56]. Overall, the telephone program showed success enrolling those who were difficult to reach.

Successful weight and lifestyle behaviour change outcomes were underpinned by high implementation similar to what has previously been seen in other lifestyle interventions in both a research and dissemination context [20, 24, 56]. The 4 % weight loss and behavioural changes observed in the telephone program are similar in magnitude to those observed in three other studies of telephone-delivered weight loss programs (reporting on completers analyses) delivered to a state-wide population [20], primary care patients in a community catchment area [21] and for patients previously hospitalised with coronary heart disease [57]. This is of interest as participants in this study were living with multiple co-morbidities, compared to the participants taking part in other dissemination trials.

In the current study, weight loss in the telephone program was significantly greater than that observed in the group-based program at 2 months. A recent meta-analysis comparing telephone to face-to-face interventions for weight loss found similar magnitudes of weight loss between modalities when equated on number of contacts [27]. Generally, group-based programs have resulted in greater weight loss in the context of randomised controlled trials than face-to-face weight loss interventions targeting individuals (i.e. individual dietetic counselling) [9]. However, no trials to date have compared individually targeted telephone programs to face-to-face group-based programs for initial weight loss [27].

Limited evidence on the cost-effectiveness of telephone-delivered lifestyle interventions is available [58, 59]. In this study, the telephone program was more cost-effective in terms of healthy life-years gained. The 0.8 kg lost for all participants who began the group-based program is likely to be regained in a matter of months, while it takes around 3.5 years to regain the 4.1 kg lost with the telephone intervention, on average assuming a regain of approximately 0.03 BMI unit per month during maintenance phases [55]. It is impossible to determine whether the difference in cost-effectiveness between groups is due to differences in sample characteristics or the intervention modality of each program, or both. The cost-effectiveness of the telephone program is comparable to that of Weight Watchers [26] and would generally be considered cost-effective in the Australian context [51]. The program is thus able to provide an effective and efficient weight loss service that reached more patients of a different demographic who were otherwise not engaging in such services. Alternative models of delivering weight management services that are flexible and therefore accessible by those with working and other commitments hold promise as a method to intervene earlier and therefore may assist with the prevention or delay progression of obesity-related comorbid conditions. Additionally, provision of alternative delivery options for weight management including face-to-face and telephone (potentially integrating technologies such as internet-based modalities, text messaging or smart phone applications) may provide greater reach to the growing number of patients requiring weight management services. Future research is required to better understand the reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these modalities in real-world settings.

High attrition is both a limitation of this study for both programs (43 % telephone program; 34 % group-based program) and weight loss programs in general with dropout rates of up to 60 % in other applied setting programs over a six-month follow-up period [8, 20, 22, 24]. For patients in the telephone program, the most commonly reported reason for dropping out was being too busy to participate. Consistent predictors of patient dropout have not yet been identified, perhaps due to population or treatment differences, or differences in definition and measurement of attrition [60, 61]. Further research is required to understand characteristics of those who are more likely to drop out of a program so they can be identified as a high-risk group and provided extra support.

In the current study, any resultant bias from attrition appeared minimal with completers and multiple imputation estimates being similar (to within ±20 %). The sample size was not chosen a priori for comparing the programs and was too small to exclude meaningful differences (for between-group) as unlikely for some of the null results (e.g. FFBQ Indices). Direct comparison between the two non-randomised arms accounted for many potential confounders; however, there is likely to be residual confounding (e.g. from unmeasured variables). Importantly, a strength of the recruitment protocol and non-randomised design was the ability to examine the demographic characteristics of those participating in the group-based program compared to those declining and engaging in the telephone program.

Future research is needed to evaluate the extent to which telephone programs may be suitable for the more challenging type of patient (older demographic, lower income, greater co-morbidities) currently accessing group-based treatment. Additionally, there remain a large proportion of patients referred for weight loss services who are unable to be contacted or refuse both service delivery options (approximately 70 % of those referred; Fig. 1). Further research to explore alternative models to engage and support these patients with weight loss services is needed.

Findings from this study indicated that the telephone-based weight loss program was a feasible, effective and cost-effective service delivery option when evaluated in a real-world hospital outpatient setting. Additionally, the telephone-delivered program may be a suitable alternative service delivery option to the existing group-based program. Evaluating alternative and broader-reaching service delivery models for reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is important for decision-making in relation to the allocation of scarce health care resources to address the significant proportion of patients who remain unengaged with existing weight management services.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Queensland Health, Health Practitioner Grant (2011). MEW is supported by Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship. IJH is supported by a Queensland Health, Health Practitioner Research Grant and a Lions Medical Research Fellowship. EGE is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship. MMR is supported by a National Breast Cancer Foundation Early Career Fellowship. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of clinical staff including Melissa Gwizd, Amy Davis, Louise Cooney, Emily Power, Scott Honeyball and Steven McPhail, as well as the Princess Alexandra Hospital Department of Nutrition and Dietetics and the Department of Diabetes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: A telephone-based weight loss service may be a feasible, effective and cost-effective alternative service delivery option to an existing group-based program in an acute-care hospital outpatient setting.

Policy: Evaluating alternative and broader-reaching service delivery models for reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is important for decision-making in relation to the allocation of scarce health care resources.

Research: Further research needs to address the significant proportion of patients who remain unengaged with existing weight management services.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13142-016-0416-6.

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Preventative Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. In: Ministry for Health and Ageing, Canberra. 2009.

- 3.Colagiuri S, Lee CM, Colagiuri R, et al. The cost of overweight and obesity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2010;192:260–264. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korda RJ, Liu B, Clements MS, et al. Prospective cohort study of body mass index and the risk of hospitalisation: findings from 246 361 participants in the 45 and Up Study. Int J Obes. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hart CL, Hole DJ, Lawlor DA, Smith GD. Obesity and use of acute hospital services in participants of the Renfrew/Paisley study. J Publ Health. 2007;29:53–56. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darnis S, Fareau N, Corallo CE, Poole S, Dooley MJ, Cheng AC. Estimation of body weight in hospitalized patients. QJM. 2012;105:769–774. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012; 82 [PubMed]

- 8.Ash S, Reeves M, Bauer J, et al. A randomised control trial comparing lifestyle groups, individual counselling and written information in the management of weight and health outcomes over 12 months. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1557–1564. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul-Ebhohimhen V, Avenell A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of group versus individual treatments for adult obesity. Obes Facts. 2009;2:17–24. doi: 10.1159/000186144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:119–127. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goode A, Reeves M, Eakin E. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behaviour change: an updated systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eakin EG, Lawler SP, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Wier MF, Ariens GA, Dekkers JC, Hendriksen IJ, Smid T, van Mechelen W. Phone and e-mail counselling are effective for weight management in an overweight working population: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanWormer JJ, Martinez AM, Benson GA, et al. Telephone counseling and home telemonitoring: the Weigh by Day Trial. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:445–454. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.33.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Pronk NP, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: weigh-to-be 2-year outcomes. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ely AC, Banitt A, Befort C, et al. Kansas primary care weighs in: a pilot randomized trial of a chronic care model program for obesity in 3 rural Kansas primary care practices. J Rural Health : Off J Am Rural Health Assoc National Rural Health Care Assoc. 2008;24:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djuric Z, DiLaura NM, Jenkins I, et al. Combining weight-loss counseling with the weight watchers plan for obese breast cancer survivors. Obes Res. 2002;10:657–665. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dekkers JC, van Wier MF, Ariens GA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on cardiovascular risk factors among a Dutch overweight working population: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittemore R. A systematic review of the translational research on the Diabetes Prevention Program. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:480–491. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hara BJ, Phongsavan P, Venugopal K, et al. Effectiveness of Australia’s Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service(R): translational research with population wide impact. Prev Med. 2012; 55: 292-298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Goode A, Reeves M, Owen N, Eakin E. Results from the dissemination of an evidence-based telephone-delivered intervention for healthy lifestyle and weight loss: the Optimal Health Program. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:340–350. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0210-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sangster J, Furber S, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Effectiveness of a pedometer-based telephone coaching program on weight and physical activity for people referred to a cardiac rehabilitation program: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiopulmonary Rehab and Prev. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD, et al. Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): a multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2775–2783. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goode AD, Reeves M, Owen N, Eakin E, G. Results from the dissemination of an evidence-based telephone-delivered intervention for healthy lifestyle and weight loss: the optimal health program. Trans Behav Med. 2013; 3: 340-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yngve A, Nilsson A, Sjostrom M, Ekelund U. Effect of monitor placement and of activity setting on the MTI accelerometer output. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:320–326. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048829.75758.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobiac L, Vos T, Veerman L. Cost-effectiveness of Weight Watchers and the Lighten Up to a Healthy Lifestyle program. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves MM, Brakenridge CL, Whelan ME, Eakin EG. Weight loss via the telephone - does it work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australia and New Zealand Obesity Society Annual Scientific Meeting; 2014; Sydney.

- 28.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102–S138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Health and Medical Research Council. Management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents and children: clinical practice guidelines for primary care health professionals. 2013.

- 30.Emmons K, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in health care settings: opportunities and limitations. Am J Prevent Med. 2001;20:68–74. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borushek A. The CalorieKing Calorie, Fat, and Carbohydrate Counter 2011. USA: Family Health Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity interventoin strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:459–471. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Institute of Medicine of the National Academics. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington DC. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Wing R, Hill J. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorp A, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW. Sedentary behaviours and subsequent health outcomes in adults: a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am J Prevent Med. 2011;41:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slavin JL. Dietary fiber and body weight. Nutrition. 2005;21:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. The practical guide: identification, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. In: The North American Association for the Study of Obesity, Bethesda. 2000.

- 40.Johnson M, Sallis J, Hovell M. Self-report assessment of walking: effects of aided recall instructions and item order. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2000;4:141–155. doi: 10.1207/S15327841Mpee0403_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ActiLife 6.0 [computer program]. Version 6. Pensacola, Florida 2011.

- 42.SAS/GRAPH 9.2, Second Edition [computer program]. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2010.

- 43.Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:777–781. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winkler EA, Gardiner PA, Clark BK, Matthews CE, Owen N, Healy GN. Identifying sedentary time using automated estimates of accelerometer wear time. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:436–442. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swartz A, Strath S, Bassett D, O'Brian W, King A, Ainsworth B. Estimation of energy expenditure using CSA accelerometers at hip and waist sites. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:450–456. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeves M, Winkler E, Eakin E, G. The Fat and Fibre Behaviour Questionnaire: reliability, relative validity and responsiveness to change. Nutrition and Dietetics. 2014 [Epub ahead of print].

- 47.Rutishauser IH, Webb K, Abraham B. Evaluation of short dietary questions from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. In: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra. 2001.

- 48.Eakin EG, Reeves MM, Winkler E, et al. Six-month outcomes from living well with diabetes: a randomized trial of a telephone-delivered weight loss and physical activity intervention to improve glycemic control. Ann Behav Med : Publ Soc Behav Med. 2013;46:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th Ed. USA. 2001.

- 50.Bendel R, Afifi A. Comparison of stopping rules in forward regression. J Am Stat Assoc. 1977;72:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vos T, Carter R, Barendregt J, et al. Assessing cost-effectiveness in prevention (ACE-prevention): final report. University of Queensland, Brisbane and Deakin University, Melbourne; 2010.

- 52.Forster M, Veerman JL, Barendregt JJ, Vos T. Cost-effectiveness of diet and exercise interventions to reduce overweight and obesity. Int J Obes. 2011;35:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barendregt JJ, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Van Hout BA, Van Den Bosch JM, Bonneux L. Coping with multiple morbidity in a life table. Math Popul Stud. 1998;7:29–49. doi: 10.1080/08898489809525445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health Expenditure Australia 2010–11. Canberra: AIHW;2012.

- 55.Dansinger M, Tatsioni A, Wong J, Mei C, Balk E. Meta-analysis: the effect of dietary counseling for weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:41–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jolly K, Lewis A, Beach J, et al. Comparison of range of commercial or primary care led weight reduction programmes with minimal intervention control for weight loss in obesity: lighten up randomised trial. Br Med J. 2011; 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Ski CF, Vale MJ, Bennett GR, et al. Improving access and equity in reducing cardiovascular risk: the Queensland Health model. Med J Aust. 2015;202:148–152. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graves N, Barnett AG, Halton KA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a telephone-delivered intervention for physical activity and diet. PLoS One. 2009;4:7135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell MK, Carr C, Devellis B, et al. A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption for cancer prevention and control. Ann Behav Med : Publ Soc Behav Med. 2009;38:71–85. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev : Off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2011;12:912–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miller BM, Brennan L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: a call to action! Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015; 9: 187-202. [DOI] [PubMed]