Abstract

Whole-transcriptome sequencing studies from recent years revealed an unexpected complexity in transcriptomes of bacteria and archaea, including abundant non-coding RNAs, cis-antisense transcription and regulatory untranslated regions (UTRs). Understanding the functional relevance of the plethora of non-coding RNAs in a given organism is challenging, especially since some of these RNAs were attributed to ‘transcriptional noise’. To allow the search for conserved transcriptomic elements we produced comparative transcriptome maps for multiple species across the microbial tree of life. These transcriptome maps are detailed in annotations, comparable by gene families, and BLAST-searchable by user provided sequences. Our transcriptome collection includes 18 model organisms spanning 10 phyla/subphyla of bacteria and archaea that were sequenced using standardized RNA-seq methods. The utility of the comparative approach, as implemented in our web server, is demonstrated by highlighting genes with exceptionally long 5′UTRs across species, which correspond to many known riboswitches and further suggest novel putative regulatory elements. Our study provides a standardized reference transcriptome to major clinically and environmentally important microbial phyla. The viewer is available at http://exploration.weizmann.ac.il/TCOL, setting a framework for comparative studies of the microbial non-coding genome.

INTRODUCTION

The growing availability of next-generation sequencing technologies has led to a burst of studies characterizing the transcriptomes of many prokaryotic species, often charting transcription start sites (TSSs) at single-nucleotide resolution (1–9). These studies unraveled unexpected complexity in the transcriptomes of bacteria and archaea including numerous long regulatory 5′UTRs, non-coding RNAs, alternative operon structures, internal promoters and abundant cis-antisense transcription (10–12).

Comparative transcriptome studies of various prokaryotes had shown that transcriptional maps may differ even among closely related species, challenging functional interpretations of ncRNA transcription with suspected transcriptional noise (13–17). While the functional importance of non-conserved transcription remains debated (18), cases in which evolutionary conservation is observed were shown to have the potential to highlight functionally important features in the organisms’ transcriptional dynamics (19–21). To date, comparative transcriptomic studies were limited to few organisms, usually comparing closely related species.

A major challenge in comparative transcriptomics studies is the construction of reliable and comparable transcriptome maps across multiple diverse species. The first published transcriptome maps were based on manual curation of multiple putative TSSs. With the dramatic reduction of sequencing costs, however, using manual curation for construction of transcriptome maps becomes increasingly prohibitive because it is not scalable to large number of organisms and multiple conditions. Thus, in the last couple of years several methods had been developed to automatically infer TSSs. Some of these methods are tailored analyses for differential 5′-RNA sequencing data (dRNA-seq, (11)) as in the primary transcriptome of H. pylori (1). These include methods that are primarily based on analyzing two RNA-seq libraries, one untreated and one enzymatically treated to enrich for primary transcripts (22–24). Additional methods that analyze TSSs integrate comparative signals from closely related species (25), while other methods attempt to delineate transcript boundaries (both TSS and termination) based on statistically significant local differences in RNA-seq coverage (26,27). However, methods that can infer primary TSSs based on multiple transcriptomic and genomic features, taken together, are still lacking.

In this study, we present the TCOL web-server (Transcriptomes Compared across the tree Of Life) that includes several important novel components. First, TCOL encompass the largest compendium of comparable transcriptomes to date, spanning representatives of the major phyla of the prokaryotic tree of life. Second, all transcriptomes were sequenced using standardized approach, combining RNA-seq and 5'-end sequencing, generating comparable data. Third, we reconstructed the transcriptome maps using a computational pipeline that utilized machine learning to accurately infer primary TSSs based on multiple genomic and transcriptomic features. Fourth, TCOL includes a comparative transcriptome browser, allowing for simultaneous viewing of transcriptome maps for homologous genes across divergent organisms. Finally, the TCOL transcriptomes are BLAST-searchable with query sequences provided by users, broadening the utility of this web-server to the microbiology community.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions

Most data were derived from previously published studies, with the exception of the following organisms for which data were obtained within this study: E. coli was grown in LB medium overnight, diluted 1:200 into fresh LB and incubated at 37°C until OD600nm of ∼0.3 (early-mid log). B. subtilis was grown in TB, similarly diluted into fresh TB until reaching mid log OD600nm of ∼0.6. G. oxydans 621H was grown in pH 6 in constant temperature of 30°C in two media: (i) mannitol fermentation (50 mM glucose) (ii) glycerol fermentation (50 mM glycerol) until reaching OD600nm of 1.12 and OD600nm of 0.9, for mannitol and glycerol, respectively. C. acetobutylicum was cultured in phosphate limited conditions at (i) pH 4.5 (ii) pH 5.7 until OD600nm of 3.7. T. thermophilus was cultured in TB medium at 70°C until OD600nm of 3.0. S. acidocaldarius was cultured in ‘Brock medium’ (28) with 0.1% tryptone added, until early stationary phase. For all other organisms culture conditions details were published (Supplementary Table S1).

RNA-seq protocols and reads mapping

Total RNA-seq (strand insensitive) and 5′ end transcriptome (strand sensitive) libraries were produced as described previously (19,29) (Supplementary Materials). List of transcriptomes in this study is depicted in Table 1, and sequencing depth and growth conditions of all organisms are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Briefly, the 5′ differential RNA-seq protocol included the construction of 2 libraries: A treated library in which RNA is incubated with Tobacco Acid Pyrophosphatase (TAP, Epicentre), which we term TAP(+) and an untreated library termed TAP(−). The relative number of TAP(+) and TAP(−) reads that are mapped to the same site is indicative of the likelihood of that site to represent primary TSS. Higher TAP(+)/TAP(−) ratios typically represent primary TSSs while lower values represent processing sites (Supplementary Materials).

Table 1. The transcriptome maps in the study. A quantitative summary of major transcriptional features including various types of transcriptional start sites (TSSs), inferred small RNAs (sRNAs) and inferred operons.

| Organism | Accession | Growth conditions | genes | gTSS | iTSS | aTSS | nTSS | sRNAs | Operonsa | RNA-seq and TSS data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | NC_000964 | Terrific Broth, mid-log phase | 4420 | 1292 | 20 | 29 | 128 | 75 | 1242 | This study |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris | NC_002937 | DSMZ medium | 3466 | 1365 | 204 | 407 | 215 | 99 | 1193 | (42) |

| Escherichia coli | NC_000913 | mid-log phase | 4495 | 1118 | 10 | 35 | 83 | 36 | 1059 | This study |

| Listeria monocytogenes | NC_003210 | log phase 37°C; log phase 30°C; hypoxia; stationary phase 37°C; ΔsigB; ΔprfA | 2936 | 1388 | 26 | 19 | 109 | 36 | 1282 | (19) |

| Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus | NC_005363 | attack phase; growth phase | 3627 | 407 | 8 | 16 | 46 | 23 | 395 | (43) |

| Catenulispora acidiphila | NC_013131 | DSMZ medium | 8984 | 1996 | 0 | 96 | 197 | 118 | 1908 | (42) |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | NC_003030 | pH 4.5; pH 5.7 | 3777 | 866 | 5 | 1 | 112 | 26 | 839 | This study |

| Gluconobacter oxydans | NC_006677 | mannitol; glycerol | 2499 | 1268 | 135 | 642 | 168 | 87 | 1113 | This study |

| Kangiella koreensis | NC_013166 | DSMZ medium | 2681 | 627 | 16 | 16 | 49 | 16 | 601 | (42) |

| Lactobacillus brevis | NC_008497 | ATCC medium | 2265 | 777 | 6 | 7 | 71 | 29 | 764 | (42) |

| Lactococcus lactis | NC_002662 | M17 medium | 2400 | 746 | 5 | 7 | 82 | 31 | 714 | (42) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | NC_008463 | 28°C; 37°C (LB medium) | 5975 | 2224 | 5 | 195 | 321 | 158 | 1728 | (29) |

| Synechococcus WH7803 | NC_009481 | Artificial seawater medium | 2585 | 1176 | 0 | 45 | 31 | 9 | 1125 | (21) |

| Synechococcus WH8102 | NC_005070 | Artificial seawater medium | 2581 | 1005 | 0 | 52 | 44 | 5 | 957 | (21) |

| Spirochaeta aurantia | Saur_Contig1177 | DSMZ medium | 4124 | 1284 | 8 | 212 | 84 | 34 | 1229 | (42) |

| Sulfolobus acidocaldarius | NC_007181 | yeast extract, stationary phase | 2330 | 1050 | 0 | 32 | 133 | 45 | 1033 | This study |

| Sulfolobus solfataricus | NC_002754 | glucose; cellobiose; minimal | 3034 | 1094 | 0 | 124 | 202 | 109 | 1040 | (4) |

| Thermus thermophilus | NC_005835 | mid-log phase | 2035 | 731 | 0 | 109 | 41 | 15 | 688 | This study |

gTSS = A TSS found upstream to coding gene.

iTSS = internal TSS within a gene.

aTSS = cis-antisense TSS overlapping a gene.

nTSS = non-coding, intergenic TSS.

aIncluding overlapping operons.

Determination and assessment of reliability of TSSs

A machine learning approach was utilized to infer TSSs from all 5′ mapped sites (the set of putative TSSs). The inference algorithm consists of two main steps: (i) Heuristic determination of the training set and (ii) supervised Random Forest learning (pipeline steps in Supplementary Figure S1). The learning is based on a set of 15 features which capture relevant TSS characteristics including genomic, whole-transcriptome RNA-seq coverage patterns, and 5' differential RNA-seq (TAP(+)/(−), see list in Supplementary Table S2). A Random Forest machine learning procedure was used to infer and quantify reliability of the TSS determination. Finally, the classification of TSS types (e.g. gTSS as gene-related TSS or nTSS as non-coding TSS) was performed automatically based on genomic and transcriptomic features (Supplementary Extended Methods).

Inference of operons, sRNAs and putative ORFs

The general approach to infer operons (transcriptional units, TUs), sRNAs and putative ORFs was as previously described (19,29). Briefly, operon beginnings are defined by location of primary gTSSs while operon ends are defined by the genomic coordinates of the last gene which is likely to be expressed within the same TU. Inclusion of downstream genes in the same TU is dependent on both genomic and transcriptomic features (Supplementary Extended Methods). sRNAs inference is based on the presence of a TSS and expression in intergenic regions (Supplementary Extended Methods). Putative ORFs are inferred based on bioinformatic detection of putative start and stop codons in intergenic regions. Putative ORFs of at least 30 amino acids were subjected to BLASTX search against the non-redundant protein database.

The genomic browser and comparative analysis of gene families

The genomic browser is based on GenBank annotation for each organism in this study. The genomic browser annotation is augmented by sRNA and cis-regulators if found in Rfam repositories (30) or found with covariance models (31) homology search against the Rfam database (E-value < 10−3).

The comparative approach is focused on protein families. We constructed the set of homologous proteins by first producing the network of all homologies with blastp E-value < 10−3 and delineation of best bi-directional hits (BBH) between homologs. For readability we will refer to sets of BBH homologs genes as orthologs throughout the manuscript. For each locus across all organisms in our study all BBH loci are listed and a comparative viewer with aligned transcriptomes for the entire set is available. Further comparative analysis of gene families is facilitated by depicting, for each locus, the entire list of homologs (orthologs and paralogs) found in our compendium with the same COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) affiliation (32,33). The COG affiliation is shown separately for three phylogenetic levels: ‘TOL’, ‘Domain’ and ‘Phylum’ for orthologous groups across the entire Tree Of Life, Domain-specific, or Phylum-specific, respectively.

RESULTS

General approach and the TCOL transcriptome browser

To facilitate comparison of transcriptomes of diverged organisms we use standardized sequencing protocols and a fully automated computational pipeline for the reconstruction of transcriptome maps, including accurate inference of TSSs, and transcription-dependent prediction of sRNAs and operons. We produced a user-friendly webserver that visualizes the transcriptome maps, available at http://exploration.weizmann.ac.il/TCOL. The transcriptome browser provides a multi-track view of homologous genes across the tree of life, providing a unique comparative view into the transcriptional activity of gene families across diverged organisms.

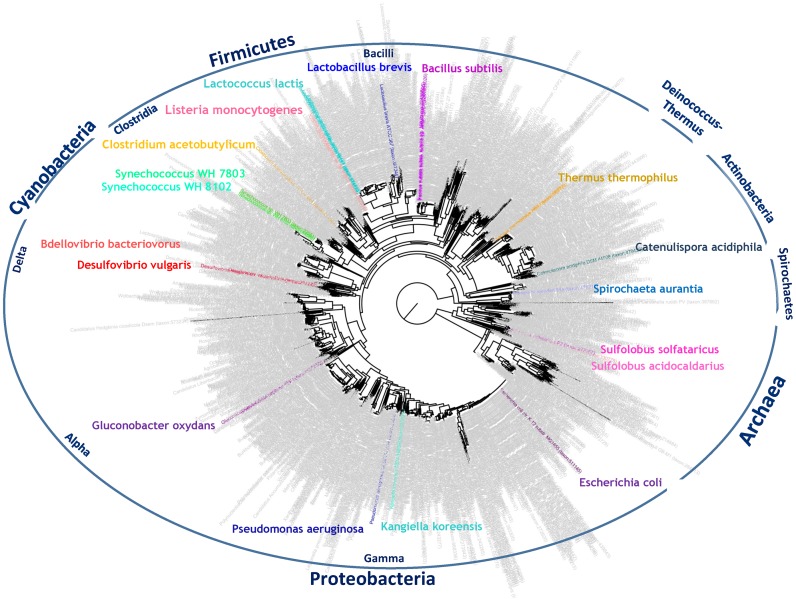

The compendium of transcriptomes in this study encompasses the two prokaryotic domains of life (bacteria and archaea) with 18 representative species across 10 different phyla/subphyla (Figure 1). The transcriptomes of multiple organisms, typically grown in one or two conditions, were sequenced at a high depth both by standard Illumina RNA-seq, which captures the full length of the transcript, and using a 5′-end-specific sequencing protocol, which we previously described (4,19) (Table 1; Supplementary Table S1). For organisms analyzed in more than one growth condition, the transcriptome map for the comparative view is derived from merging the activity at the different conditions, resulting with greater sequencing depth and more comprehensive transcriptome maps. However, data tracks for the individual conditions are also presented in the TCOL browser, allowing the study of condition-specific transcription.

Figure 1.

Representative transcriptomes presented on the tree of life. The compendium of transcriptomes in this study is denoted as colored lineages across the prokaryotic tree of life consisting of 18 representative species across different phyla including Gamma, Alpha and Delta Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Firmicutes, Deinococcus-Thermus, Actinobacteira, Spirochaetes and the Archael Crenarchaeotes phylum. Tree was taken from (44,45), reconstructed with (45).

Reconstruction of transcriptome maps

A quantitative summary of all transcriptome maps in this study is presented in Table 1. Primary TSSs were inferred using a machine learning approach, integrating relevant genomic and transcriptomic information in an unbiased manner using multiple features (Supplementary Table S2). In order to estimate the accuracy of our automated inference of TSSs, we compared these to a set of manually curated TSSs in three organisms for which published TSS maps are available - Listeria monocytogenes (19), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29) and Sulfolobus solfataricus (4). In comparison with these benchmarks, both the sensitivity and precision were high, with sensitivity (True Positive, TP) of 79.3%, 74.5% and 64.1%, and precision (TP/TP+FP) of 78.3%, 70.9% and 64.1% for Listeria, Pseudomonas and Sulfolobus, respectively (Supplementary Materials Figure S2). Further inspection of a subset of TSSs in which the automatic annotation and the benchmark, manually curated data, disagreed showed that in the vast majority of cases the automatic inference is more likely to report the correct TSS (Supplementary Materials).

Using the TCOL transcriptome viewer

Comprehensive documentation of the functions available in TCOL is detailed in the ‘help’ page of the web server.

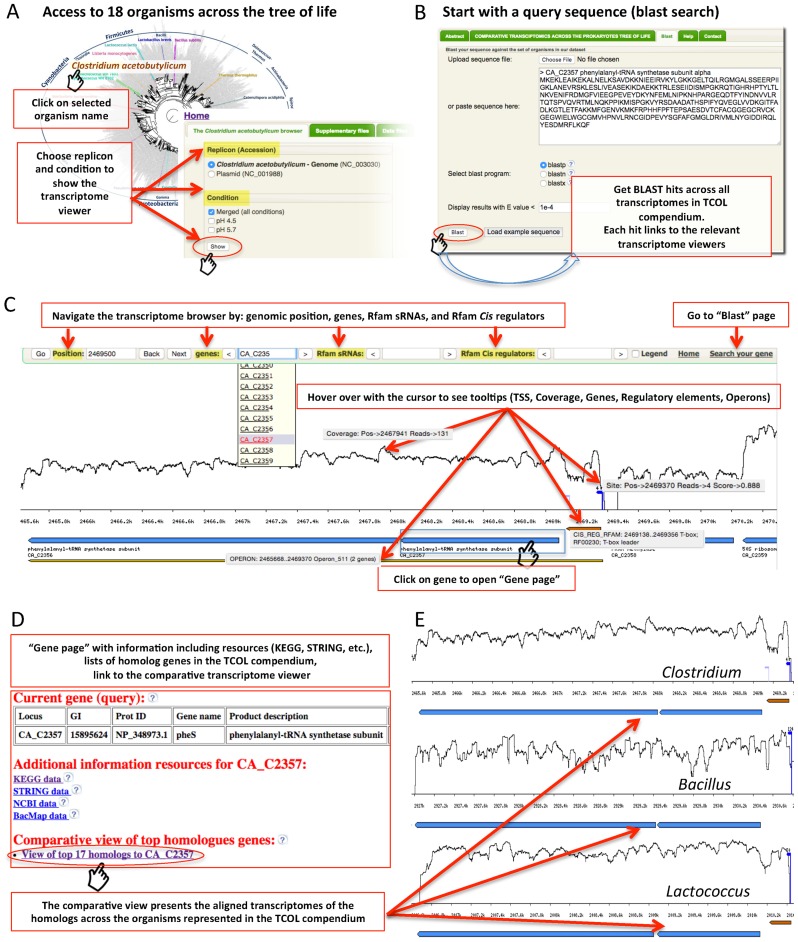

Figure 2 illustrates some of the main features of TCOL. Users can start by choosing a representative organism (Figure 2A). The next step is choosing a desired sample (e.g. growth condition), and pressing ‘Show’ to open the transcriptome viewer (Figure 2C). A user can navigate the browser by genome position, gene locus name or annotated Rfam genes. Genomic and transcriptomic information appears as ‘tooltips’ upon hovering with the cursor, including TSS information (e.g. hover over plotted TSS arrow to reveal position, number of supporting reads and reliability score of TSS), coverage information (number of RNA-seq reads per position), information on genes and regulatory elements and operon inferences. The user may click on a gene to open a ‘Gene page’ (Figure 2D) containing specific gene and homologs information, including links to the homologs transcriptional maps, and a link to the comparative viewer that visualizes all homologs together (Figure 2E; Figure 3). Furthermore, in each ‘Gene page’ the ‘COG-based homology’ section contains links to the transcriptomes of all the genes in our data set with the same COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) (32,33).

Figure 2.

The Transcriptomes Compared across the Tree of Life (TCOL) online web-server. Interactive browser with detailed transcriptional maps of 18 representative species across the microbial tree of life. Transcriptome maps can be accessed either by (A) choosing an organism or (B) by using BLAST with a user-provided query sequence. (C) Transcriptome maps can be navigated with multiple functions and are information-rich. Some of the information appears as tooltips when hovering above the features with the cursor. (D) ‘Gene page’ (when clicking on a gene in the browser) containing information about the gene including its homologs. (E) The comparative transcriptome viewer shows aligned transcriptomes of homologous genes, centered on the queried gene. This view is accessible from the ‘Gene page’ and from the BLAST results page.

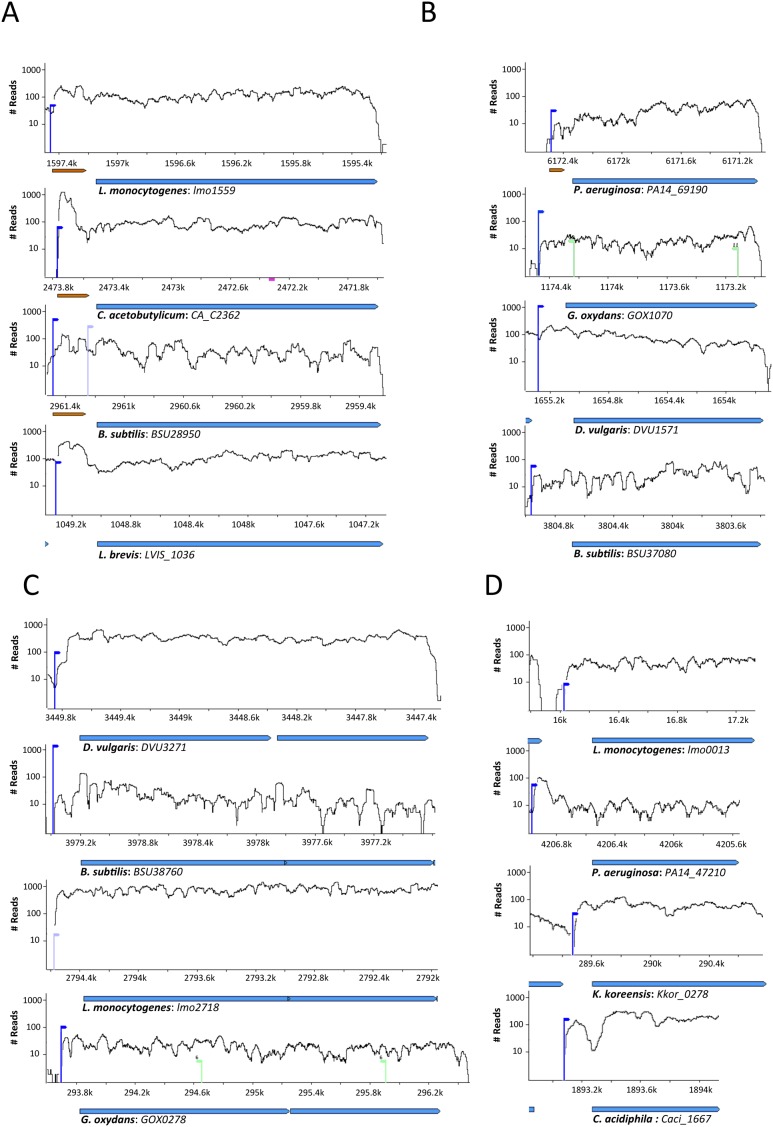

Figure 3.

Comparative transcriptome views of homologous genes with long 5'UTRs. (A) Threonyl-tRNA synthetase (thrS) has a known T-box (RF00230) in Listeria, Clostridium and Bacillus. (B) The transcription termination factor rho gene (COG1158) in which regulatory structure was previously inferred in Pseudomonas (Pseudomon-Rho). (C) The cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit I (COG1271) gene (D) The cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit II (COG1622) gene. Brown horizontal arrows denote RFAM-identified cis-regulators.

Alternatively, browsing can start by BLAST searching a query sequence against the database of the TCOL compendium (Figure 2B). Each of the returning hits includes links to both the comparative transcriptome map as well as the maps for individual species. There are three different BLAST options: blastp, blastn and blastx.

Users interested in browsing all TSS or RNA-seq data globally can use the ‘Supplementary files’ tab that contains downloadable detailed information on the transcriptome annotation, including summary statistics (‘TSS statistics’), details of the TSS for each gene (‘TSS’), summary of total RNA-seq data statistics (‘RNA-seq summary’), number of reads mapped to each gene (‘Expression per gene’) and a summary file with additional transcriptome features including RFAM genes, operons and identified sRNAs (‘Additional transcriptome annotations’).

Comparative transcriptomics highlights cis-acting RNA regulators

One of the main applications of the comparative transcriptomics approach is to highlight cases in which recurring transcriptomic features are found across homologs, suggestive of regulatory importance and evolutionary conservation. We demonstrate this by focusing on orthologous genes showing long 5′ UTRs across the tree of life.

Long regulatory 5′ UTRs have the capacity to integrate environmental and inner-cellular cues into regulation of gene expression (34,35). Previous comparative genomics studies significantly enhanced the capacity to detect putative functional 5′ regulatory elements (36,37). However, it is likely that many additional regulatory 5′ UTRs elements remain to be found, including regulatory elements with conservation that is insufficient for reliable detection from genomic data alone (38,39).

Searching for gene families with long conserved 5′ UTR in multiple organisms across the tree of life, we found 41 gene families (COGs) with exceptional propensity for recurring long 5′ UTRs (Supplementary Table S3). Approximately three quarters of the gene families within this list recapitulated previously reported 5′ UTR regulatory elements (Supplementary Figure S4). These include 14 known riboswitches (including T-box, S-box, TPP, Cobalamin, FMN, glmS ribozyme and Glycine, Purine and Lysine riboswitches); 8 ribosomal leaders; 2 thermosensor RNA elements; and 6 cis-regulatory elements of various categories that had been reported including the rimP leader, Pseudomon-GroES, Pseudomon-Rho, Lacto-rpoB, mini-ykkC and leucine operon leader. We further found 8 novel putative candidates, inferred to harbor RNA-regulatory elements of unknown function in their 5′ UTRs, and additional 3 ribosomal leader candidates (Supplementary Table S3; Figure 3).

As examples, Figure 3 presents the comparative transcriptome viewer of four gene families with recurring long 5′ UTRs. Figure 3A illustrates the 5′ UTR of the threonyl-tRNA synthetase gene family (COG0441, thrS), where T-box 5′ UTR riboswitches are found in gram-positive bacteria (40). Among the 5 presented cases, the Rfam T-box leader (RF00230) is described only in Listeria, Clostridium and Bacillus (30). However, searching for structural homology (31), we found a similar structural RNA element in the 5′ UTRs of the gram-positive Lactobacillus and Lactococcus, suggesting that these Lactobacillales homologs are regulated by an element similar to the T-box riboswitch, but with structural homology that is too weak for detection based on sequence and/or structure prediction alone.

A regulatory element in the 5′UTR of the Rho transcription terminator was discovered bioinformatically in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and termed Pseudomon-Rho (37). Among the homologs of the ‘Rho, Transcription termination factor’ gene family (COG1158), we found recurring long 5′UTRs across multiple genera including Pseudomonas, Gluconobacter, Desulfovibrio and Bacillus (Figure 3B). These results suggest that the Rho transcriptional terminator is being regulated by a leader 5′UTR element in multiple bacterial species in addition to Pseudomonas.

The gene families ‘cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit I’ (COG1271), and ‘cytochrome o ubiquinol oxidase subunit II’ (COG1622) are part of the CydABX and CyoABCD operons, respectively. These two different cytochrome oxidase complexes, responsible for cellular respiration, are known to be regulated by the oxygen state. We found, for both of these gene families, recurring long 5′UTRs across divergent bacteria, implying the existence of cis-acting RNA regulators within their 5′UTRs (Figure 3C and D).

CONCLUSION

The comparative transcriptomics approach was recently shown to be useful for studying closely related species – either strains within the same species (15) or species within the same genus (16,19,21). Broader evolutionary comparison across diverse species based on aggregating results from different studies (41) is limited due to methodological differences in RNA sequencing and computational analyses. Here we provide, for the first time, a comparative transcriptome viewer of representative species spanning the prokaryotic tree of life, generated by standardized methodologies in both data generation and data analysis. This constitutes an important step toward better understanding the similarities and differences in transcriptome regulation and dynamics in various organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Burge for assisting with access to Rfam data and Zizhen Yao for useful discussions and help with CMfinder. We thank W. Liebl, A. Ehrenreich and C. Doering for contributing the RNA of C. acetobutylicum, G. oxydans and T. thermophilus. We also thank Sonja-Verena Albers and Michaela Wagner for contributing S. acidocaldarius cell pellets.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

ISF [personal grant 1303/12 and I-CORE grant 1796/12]; ERC-StG program [260432]; HFSP [RGP0011/2013]; Abisch–Frenkel foundation; Pasteur–Weizmann council grant; Minerva Foundation; Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; DIP grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; AXA postdoctoral research grant [project 711545 to O.C.]. Funding for open access charge: ERC-StG program [260432].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma C.M., Hoffmann S., Darfeuille F., Reignier J., Findeiss S., Sittka A., Chabas S., Reiche K., Hackermüller J., Reinhardt R., et al. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2010;464:250–255. doi: 10.1038/nature08756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitschke J., Georg J., Scholz I., Sharma C.M., Dienst D., Bantscheff J., Voss B., Steglich C., Wilde A., Vogel J., et al. An experimentally anchored map of transcriptional start sites in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:2124–2129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015154108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu Y., Cho B.-K., Park Y.S., Lovley D., Palsson B.Ø., Zengler K. Structural and operational complexity of the Geobacter sulfurreducens genome. Genome Res. 2010;20:1304–1311. doi: 10.1101/gr.107540.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wurtzel O., Sapra R., Chen F., Zhu Y.W., Simmons B.A., Sorek R. A single-base resolution map of an archaeal transcriptome. Genome Res. 2010;20:133–141. doi: 10.1101/gr.100396.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toledo-Arana A., Dussurget O., Nikitas G., Sesto N., Guet-Revillet H., Balestrino D., Loh E., Gripenland J., Tiensuu T., Vaitkevicius K., et al. The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature. 2009;459:950–956. doi: 10.1038/nature08080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins T.T., Kingsley R.A., Fookes M.C., Gardner P.P., James K.D., Yu L., Assefa S.A., He M., Croucher N.J., Pickard D.J., et al. A strand-specific RNA-Seq analysis of the transcriptome of the typhoid bacillus Salmonella typhi. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Güell M., van Noort V., Yus E., Chen W.-H., Leigh-Bell J., Michalodimitrakis K., Yamada T., Arumugam M., Doerks T., Kühner S., et al. Transcriptome complexity in a genome-reduced bacterium. Science. 2009;326:1268–1271. doi: 10.1126/science.1176951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoder-Himes D.R., Chain P.S., Zhu Y., Wurtzel O., Rubin E.M., Tiedje J.M., Sorek R. Mapping the Burkholderia cenocepacia niche response via high-throughput sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:3976–3981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sittka A., Lucchini S., Papenfort K., Sharma C.M., Rolle K., Binnewies T.T., Hinton J.C.D., Vogel J. Deep sequencing analysis of small noncoding RNA and mRNA targets of the global post-transcriptional regulator, Hfq. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorek R., Cossart P. Prokaryotic transcriptomics: a new view on regulation, physiology and pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:9–16. doi: 10.1038/nrg2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma C.M., Vogel J. Differential RNA-seq: the approach behind and the biological insight gained. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014;19:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creecy J.P., Conway T. Quantitative bacterial transcriptomics with RNA-seq. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014;23:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghavan R., Sloan D.B., Ochman H. Antisense transcription is pervasive but rarely conserved in enteric bacteria. MBio. 2012;3:1–7. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00156-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernick D.L., Dennis P.P., Lui L.M., Lowe T.M. Diversity of antisense and other non-coding RNAs in archaea revealed by comparative small RNA sequencing in four pyrobaculum species. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:231. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dugar G., Herbig A., Förstner K.U., Heidrich N., Reinhardt R., Nieselt K., Sharma C.M. High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple campylobacter jejuni isolates. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao W., Price M.M.N., Deutschbauer A.A.M., Romine M.F., Arkin A.P. Conservation of transcription start sites within genes across a bacterial genus. MBio. 2014;5 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01398-14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01398-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson M. The evolution of gene regulation, the RNA universe, and the vexed questions of artefact and noise. BMC Biol. 2010;8:97. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade J.T., Grainger D.C. Pervasive transcription: illuminating the dark matter of bacterial transcriptomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:647–653. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wurtzel O., Sesto N., Mellin J.R., Karunker I., Edelheit S., Bécavin C., Archambaud C., Cossart P., Sorek R. Comparative transcriptomics of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Listeria species. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:583. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voigt K., Sharma C.M., Mitschke J., Joke Lambrecht S., Voß B., Hess W.R., Steglich C. Comparative transcriptomics of two environmentally relevant cyanobacteria reveals unexpected transcriptome diversity. ISME J. 2014;8:2056–2068. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doron S., Fedida A., Hernández-Prieto M.A., Sabehi G., Karunker I., Stazic D., Feingersch R., Steglich C., Futschik M., Lindell D., et al. Transcriptome dynamics of a broad host-range cyanophage and its hosts. ISME J. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.210. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidtke C., Findeiss S., Sharma C.M., Kuhfuss J., Hoffmann S., Vogel J., Stadler P.F., Bonas U. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas identifies sRNAs with putative virulence functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2020–2031. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amman F., Wolfinger M.T., Lorenz R., Hofacker I.L., Stadler P.F., Findeiß S. TSSAR: TSS annotation regime for dRNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorjani H., Zavolan M. TSSer: an automated method to identify transcription start sites in prokaryotic genomes from differential RNA sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:971–974. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbig A., Sharma C., Nieselt K. Automated transcription start site prediction for comparative Transcriptomics using the SuperGenome. EMBnet J. 2013;19:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirauta B., Nicolas P., Richard H. Parseq: reconstruction of microbial transcription landscape from RNA-Seq read counts using state-space models. Bioinformatics. 2014;10:1409–1416. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McClure R., Balasubramanian D., Sun Y., Bobrovskyy M., Sumby P., Genco C.A., Vanderpool C.K., Tjaden B. Computational analysis of bacterial RNA-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brock T.D., Brock K.M., Belly R.T., Weiss R.L. Sulfolobus: a new genus of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria living at low pH and high temperature. Arch Mikrobiol. 1972;84:54–68. doi: 10.1007/BF00408082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wurtzel O., Yoder-Himes D.R., Han K., Dandekar A.A., Edelheit S., Greenberg E.P., Sorek R., Lory S. The single-nucleotide resolution transcriptome of pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in body temperature. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002945. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nawrocki E.P., Burge S.W., Bateman A., Daub J., Eberhardt R.Y., Eddy S.R., Floden E.W., Gardner P.P., Jones T.A., Tate J., et al. Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D130–D137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nawrocki E.P., Kolbe D.L., Eddy S.R. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Powell S., Szklarczyk D., Trachana K., Roth A., Kuhn M., Muller J., Arnold R., Rattei T., Letunic I., Doerks T., et al. eggNOG v3.0: orthologous groups covering 1133 organisms at 41 different taxonomic ranges. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D284–D289. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tatusov R.L., Fedorova N.D., Jackson J.D., Jacobs A.R., Kiryutin B., Koonin E. V, Krylov D.M., Mazumder R., Mekhedov S.L., Nikolskaya A.N., et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breaker R.R. Prospects for riboswitch discovery and analysis. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kortmann J., Narberhaus F. Bacterial RNA thermometers: molecular zippers and switches. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinberg Z., Barrick J.E., Yao Z., Roth A., Kim J.N., Gore J., Wang J.X., Lee E.R., Block K.F., Sudarsan N., et al. Identification of 22 candidate structured RNAs in bacteria using the CMfinder comparative genomics pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4809–4819. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg Z., Wang J.X., Bogue J., Yang J., Corbino K., Moy R.H., Breaker R.R. Comparative genomics reveals 104 candidate structured RNAs from bacteria, archaea, and their metagenomes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dar D., Shamir M., Mellin J.R., Koutero M., Stern-Ginossar N., Cossart P., Sorek R. Term-seq reveals abundant ribo-regulation of antibiotics resistance in bacteria. Science. 2016;352:aad9822. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westhof E. The amazing world of bacterial structured RNAs. Genome Biol. 2010;11:108. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vitreschak A.G., Mironov A.A., Lyubetsky V.A., Gelfand M.S. Comparative genomic analysis of T-box regulatory systems in bacteria. RNA. 2008;14:717–735. doi: 10.1261/rna.819308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Georg J., Hess W.R. cis-antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011;75:286–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He S., Wurtzel O., Singh K., Froula J.L., Yilmaz S., Tringe S.G., Wang Z., Chen F., Lindquist E.A., Sorek R., et al. Validation of two ribosomal RNA removal methods for microbial metatranscriptomics. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:807–812. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karunker I., Rotem O., Dori-Bachash M., Jurkevitch E., Sorek R. A global transcriptional switch between the attack and growth forms of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dehal P.S., Joachimiak M.P., Price M.N., Bates J.T., Baumohl J.K., Chivian D., Friedland G.D., Huang K.H., Keller K., Novichkov P.S., et al. MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D396–D400. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Price M.N., Dehal P.S., Arkin A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.