ABSTRACT

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains can colonize cattle for several months and may, thus, serve as gene reservoirs for the genesis of highly virulent zoonotic enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Attempts to reduce the human risk for acquiring EHEC infections should include strategies to control such STEC strains persisting in cattle. We therefore aimed to identify genetic patterns associated with the STEC colonization type in the bovine host. We included 88 persistent colonizing STEC (STECper) (shedding for ≥4 months) and 74 sporadically colonizing STEC (STECspo) (shedding for ≤2 months) isolates from cattle and 16 bovine STEC isolates with unknown colonization types. Genoserotypes and multilocus sequence types (MLSTs) were determined, and the isolates were probed with a DNA microarray for virulence-associated genes (VAGs). All STECper isolates belonged to only four genoserotypes (O26:H11, O156:H25, O165:H25, O182:H25), which formed three genetic clusters (ST21/396/1705, ST300/688, ST119). In contrast, STECspo isolates were scattered among 28 genoserotypes and 30 MLSTs, with O157:H7 (ST11) and O6:H49 (ST1079) being the most prevalent. The microarray analysis identified 139 unique gene patterns that clustered with the genoserotypes and MLSTs of the strains. While the STECper isolates possessed heterogeneous phylogenetic backgrounds, the accessory genome clustered these isolates together, separating them from the STECspo isolates. Given the vast genetic heterogeneity of bovine STEC strains, defining the genetic patterns distinguishing STECper from STECspo isolates will facilitate the targeted design of new intervention strategies to counteract these zoonotic pathogens at the farm level.

IMPORTANCE Ruminants, especially cattle, are sources of food-borne infections by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in humans. Some STEC strains persist in cattle for longer periods of time, while others are detected only sporadically. Persisting strains can serve as gene reservoirs that supply E. coli with virulence factors, thereby generating new outbreak strains. Attempts to reduce the human risk for acquiring STEC infections should therefore include strategies to control such persisting STEC strains. By analyzing representative genes of their core and accessory genomes, we show that bovine STEC with a persistent colonization type emerged independently from sporadically colonizing isolates and evolved in parallel evolutionary branches. However, persistent colonizing strains share similar sets of accessory genes. Defining the genetic patterns that distinguish persistent from sporadically colonizing STEC isolates will facilitate the targeted design of new intervention strategies to counteract these zoonotic pathogens at the farm level.

INTRODUCTION

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and especially enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC), a subset of STEC strains, cause disease in humans, ranging from mild to bloody diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis (HC), or even hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (1). STEC strains are zoonotic bacteria. The main reservoirs for STEC isolates associated with human disease are ruminants, in particular cattle, in which they only very rarely elicit clinical symptoms (2, 3). Most human cases are sporadic, but large outbreaks also occur. Although human STEC infections are often associated with the consumption of contaminated food (e.g., ground beef, cider, raw milk, sprouts, and lettuce) or water, they can also be caused by person-to-person transmission or by contact with shedding livestock (4). STEC strains from human outbreaks that can be traced epidemiologically back to cattle are only detected sporadically in the suspected source animals (5). This might be due to the delay in initiating epidemiological investigations because of the time interval between infection and the onset of severe clinical symptoms in patients, the very low infectious dose of only 10 to 100 bacteria that requires a low contamination rate of the respective vector, the heterogeneity of STEC strains within the animal reservoir that hampers detection of the implicated clone at the source, or simply the geographical distance between breeding, raising, and fattening of animals, food production, and food consumption (6–8).

More than 400 different STEC serotypes have been described to date (9). Nevertheless, most human infections are associated with only a few serotypes containing the O antigens O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157 (10) with some country-specific variations in the principal serotypes (11). Therefore, most research concerning the prevalence of STEC in reservoir animals focuses on these serotypes. In the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, studies describing the occurrence of O157:H7 in cattle were conducted (12, 13), but in continental European countries only few data on the duration of bovine shedding of STEC O26, O103, O111, O145, or O157 exist (14–17). Interestingly, a longitudinal study measuring the occurrence of STEC in cattle performed by Geue and colleagues showed that other serotypes dominate the intestinal STEC microbiota (18). These included isolates with the serotypes O156:H25/H−/Hnt (19), O165:H25 (20), and O26:H11 (21). Some of these serotypes have been linked to severe human HUS cases (e.g., O165:H25 or O26:H11), but other serotypes have not appeared in this context until now (e.g., O156:H25). The isolation of the latter from diarrheic or asymptomatic humans has only been reported sporadically (22–24). Geue et al. (18) did identify O157:H7/H− STEC among the isolates from the herds, but in lower numbers than the serotypes mentioned above, e.g., only once in one animal in one of the tested herds in contrast to O165:H25 STEC, which was isolated repeatedly in the same herd from 8 different cattle over a 12-month period (20).

E. coli has not only high serotype diversity but also high genome plasticity. About 1,200 genes define its conserved core genome, but the pan-genome contains more than 13,000 gene families, and the number is still growing (25–27). In STEC, this is in part due to several major virulence factors being located on transmissible genetic elements like plasmids, pathogenicity islands, or bacteriophages. For instance, the Shiga toxin gene stx is encoded by a bacteriophage and eae (encoding the adhesion factor intimin) is part of the LEE (locus of enterocyte effacement) pathogenicity island (28, 29). The severe O104:H4 outbreak in Germany in 2011 dramatically underscored the flexibility and adaptability of the STEC pathovar as it was caused by a newly evolved hybrid strain combining virulence properties of both EHEC and enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) (30). Recently, Eichhorn and colleagues showed that some atypical enteropathogenic E. coli (aEPEC) and EHEC isolates share the same phylogeny and termed the aEPEC isolates post- or pre-EHEC (31). Horizontal gene transfer constantly lets new STEC and EHEC strains with unforeseeable risk potential for humans arise. Consequently, STEC clones persisting in animals or farms over long time periods, which are equipped with certain sets of virulence and virulence-associated genes (VAGs), might serve as gene reservoirs for the evolution of such new strains. Thus, attempts to reduce the human risk for acquiring EHEC infections should also include strategies to control STEC isolates that persist in cattle. Colonization and persistence of STEC in the bovine host is modulated by the expression of Stx, which is also the only virulence factor common to all STEC (32). The persistence of distinct EHEC subpopulations (e.g., O157:H7) was also shown to correlate with colonization properties and, e.g., with the presence of the large EHEC virulence plasmid or of long polar fimbriae (33, 34). However, not all STEC strains persist in cattle (18). Therefore, we conducted this study to validate our hypothesis that bacterial persistence is not connected to one single bacterial factor but rather to a combination of traits. We therefore focused our research on combining the analyses of genes representing the core genome [serotype-related genes and housekeeping genes (multilocus sequence type [MLST] analysis)] with those of virulence-associated genes representing the accessory genome and thus enabling the identification of differentiating markers by analyzing STEC isolates that were either persistent colonizers or only sporadically found in cattle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and DNA preparation.

A longitudinal study monitoring the prevalence of fecal STEC had sampled 136 cattle from 4 different farms in northeast Germany. To this end, cattle from three beef farms were tested at intervals of approximately 2 to 4 weeks from birth to slaughter. One additional heifer group was tested likewise but with an interruption during pastoral feeding in the summer (18). Briefly, after DNA hybridization, 6,245 stx-positive isolates were subcultured and tested by colony hybridization for additional markers (stx1, stx2, eae, ehxA, katP, and espP). According to their virulence gene pattern (positive for stx1 and/or stx2 and at least one additional marker), isolates were submitted to a slide agglutination assay with antisera to differentiate between 43 O antigens (Denka Seiken, Japan; obtained from LD Labor Diagnostika GmbH, Heiden, Germany). Selected isolates positive for stx1 and/or stx2 in combination with eae and ehxA were submitted to the National Reference Centre for Enteric Pathogens (Hygiene Institut, Hamburg, Germany) or the National Reference Centre for Salmonella and other Bacterial Enterics (Robert-Koch-Institute, Wernigerode, Germany) for complete serotyping. Isolates belonging to O-antigen groups O26, O103, O156, O157, and O165 and rough forms were genotyped by contour-clamped homogeneous electric field-pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF-PAGE) (18–21). Sixteen STEC isolates obtained from sampling a cohort of calves in a different study and randomly selected for further genetic characterization were included in the current study as controls with an undefined colonization pattern (35).

Genomic DNA of the E. coli isolates was prepared using the ZR fungal/bacterial DNA kit (Zymo Research Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) from overnight cultures in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, following the instructions of the manufacturer. The DNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260 nm and analyzed for fragmentation by 1% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) agarose gel electrophoresis.

Whole-genome sequencing.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the isolates was performed using Illumina MiSeq 300-bp paired-end sequencing with >40× coverage. The sequence read data were first subjected to quality control using the NGS tool kit (36). Reads with a minimum of 70% of bases having a Phred score of >20 were defined as high-quality reads. De novo assembly of the resulting high-quality filtered reads into contiguous sequences (contigs and scaffolds) was performed using CLC Genomics Workbench 8.0 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark).

MLST analysis.

The gene sequences for adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA were extracted from the WGS scaffolds for MLST analysis. If the corresponding DNA sequences were incomplete or missing, Sanger sequencing (LGC Standards GmbH, Wesel, Germany) was performed according to the protocol of Wirth et al. (37). Subsequently, the sequence type (ST) and ST complex (STC) were determined by using the MLST Database from Warwick University (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). BioNumerics (version 6.6; Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) was used to create minimum spanning trees.

Genoserotyping.

To determine the serotype of an isolate, its wzx and wxy genes and an in silico PCR fragment using primers fliC-1 (5′-CAAGTCATTAATACMAACAGCC-3′) and fliC-2 (5′-GACATRTTRGAVACTTCSGT-3′) (38) were extracted from the WGS scaffolds and subjected to a BLAST search against the gene sequences proposed by Iguchi et al. (39) and Wang et al. (40) using Geneious (version 8.1.3; Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). The databases included 184 O and 43 H antigens, respectively.

All isolates were additionally submitted to the SeroTypeFinder of the Center for Genomic Epidemiology of the Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, with a selected percent identity (ID) threshold of 85% and minimum length of 60% (www.genomicepidemiology.org) (41).

BLAST search of DNA sequences within WGS scaffolds.

Specific genes or DNA fragments within the WGS scaffolds were identified with the Geneious mapper using the initial DNA sequence as the reference sequence, and then the contigs of the WGS scaffolds were mapped to the reference sequence.

DNA microarray analysis.

Miniaturized E. coli oligonucleotide arrays (ArrayStrip E.coli-gesamt-AS-2; Alere Technologies GmbH, Jena, Germany) (42–44) were applied. Normalized signal intensities (minus background) or a positive (signal intensity of ≥0.3) or negative (<0.3) result for each probe was used (IconoClust, version 4.3r0; Alere Technologies GmbH). The DNA probes and the results for each STEC isolate are shown in data set S1 in the supplemental material.

Statistical analysis.

To identify significant differences between groups of isolates in the occurrence of specific genes detected by microarray, either χ2 or Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19; IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA). To identify clusters within gene patterns, R (version 3.2.1) was chosen with application of the cluster package (version 2.0.3) (45, 46). From this package, the hierarchical method, agglomerative nesting (AGNES), was used as no number of clusters (k) is required as input. Besides the tree-like output, the agglomerative coefficient (AC) was calculated by AGNES as a quality measure (47).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Out of the 6,245 stx-positive isolates from the study of Geue et al. (18), 162 representative isolates were selected based on their O antigens and possession of the genes stx1, stx2, eae, and/or ehxA. Clones suspected to have been shed by a single animal or circulating within a herd for at least 4 months were defined as persistent colonization type (STECper), whereas isolates detected either ≤2 months (two successive sampling time points) and/or occasionally with at least a 4-month gap in detection were considered sporadically occurring (STECspo), resulting in 77 STECper and 85 STECspo isolates. Additionally, 16 isolates obtained from calves during a 6-month monitoring study (35) were used as unrelated controls, resulting in a total of 178 STEC isolates in the study.

Core genome and STEC colonization type.

For confirmation and completion of previous serotyping by Geue et al. (18), the wzx, wzy, and fliC genes were identified in the WGS scaffolds of 170 of 178 isolates (95.5%) (Table 1). This approach identified the O and H antigens in the vast majority of isolates. In only eight isolates the O antigen (ONT) and in one isolate the H antigen (HNT) was not identifiable. To determine the O antigens in the ONT isolates, the whole O-antigen biosynthesis gene cluster was selected by searching for the O cluster flanked by the galF and gnd genes in the WGS scaffolds (39). Both genes were detected within the same WGS scaffold in 7 of the 8 ONT isolates. A BLAST search of these 7 DNA fragments from galF to gnd against the NCBI nucleotide collection database yielded matches with >96% identity. Two sequences matched with 99% identity to the O-cluster operon of strain ECC-1470, a persistent bovine mastitis isolate of serotype Ont:Hnt (GenBank accession number CP010344), four sequences matched with 96 to 99% identity to O19 (accession no. CP000970), and one DNA fragment did not yield sufficient data (coverage of <41%). In the one HNT isolate, neither the fliC amplicon nor flkA, fllA, flmA, or flnA was found within the WGS scaffold. Analysis with SeroTypeFinder (41) proposed the O antigen O8 (99.6% identity for wzm; 99.7% identity for wzt) for one of the ONT isolates. In the remaining 7 ONT isolates, the search for O antigens did not give a result within the WGS scaffolds. The missing H antigen was also not identifiable with SeroTypeFinder. Comparing our own genoserotyping results with those obtained from SeroTypeFinder, we found two discrepancies concerning H-antigen identification: two isolates possessed fliC for antigen H2, and each isolate possessed one additional flkA flagellin gene (H35 and H47, respectively). Phenotypically, these double-positive isolates normally express the non-fliC genes (41), and, therefore, the genoserotypes of two flkA-positive isolates were corrected to the H antigen encoded by the flkA genes.

TABLE 1.

Occurrence of genoserotypes and MLSTs in bovine STEC according to the colonization type of the isolate

| Genoserotypea | No. of STEC isolates per colonization type |

MLST result (no. of isolates if more than one type or STC)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent | Sporadic | Not known | ST | STC | |

| O6:H49 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1079 | None |

| O8:H21 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1794 | None |

| O8:HNTc | 0 | 1 | 0 | 155 | 155 |

| O13:H11 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| O26:H11 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 21 (16), 396 (3), 1705 (9) | 29 |

| O32:H36 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 181 | 168 |

| O35:H2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5266 | None |

| O37:H4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 398 | 398 |

| O51:H25 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2325 | None |

| O59:H23 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 224 | None |

| O84:H2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 306 | None |

| O103:H2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 17 | 20 |

| O112:H35(H2)d | 0 | 0 | 1 | Unknown | None |

| O113:H21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 223 | 155 |

| O118/O151:H16e | 0 | 0 | 1 | 445 | 29 |

| O128:H47(H2)f | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1147 | None |

| O134:H21 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 345 | None |

| O136:H12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 329 | None |

| O145:H28 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 32 |

| O150:H2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 306 | None |

| O156:H8 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 327 | None |

| O156:H25 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 300 (16), 668 (6) | None |

| O157:H7 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| O157:H12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| O159:H45 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 101 | 101 |

| O165:H25 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 119 | None |

| O171:H2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 332 | None |

| O172:H25 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 660 | None |

| O174:H21 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 677 | None |

| O174:H40 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Unknown | None |

| O177:H11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 765 | None |

| O177:H25 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 342 (5), 659 (1) | None |

| O182:H25 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 300 | None |

| O185:H28 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 658 | None |

| ONT:H2c,g | 0 | 2 | 0 | 847 | None |

| ONT:H7c | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1308 | None |

| ONT:H25c,h | 0 | 4 | 0 | 58 | 155 |

| Total | 88 | 74 | 16 | NA | NA |

NT, nontypeable.

ST, sequence type; STC, ST complex; Unknown, ST not assigned in the Warwick database; NA, not applicable.

O (and H) antigen predicted by SeroTypeFinder.

Isolate possesses fliC2 and flkA35.

O118 and O151 not distinguishable by wzx and wzy.

Isolate possesses fliC2 and flkA47.

Complete O cluster matched Ont cluster in PubMed entry CP010344.

Complete O cluster matched O19 cluster in PubMed entry CP000970.

Fitting the genoserotype data to the epidemiological metadata of the isolates necessitated a regrouping of 21 isolates. Sixteen O182:H25 isolates were moved from STECspo to STECper as they had been isolated over a long time period in three of the farms tested but had not been identified by serotyping because they were originally not typeable. Five O156:H8 isolates were recategorized in the opposite direction as they had been erroneously grouped with the O156:H25 isolates into the O156 group within the STECper isolates. After consolidation, 88 STECper and 74 STECspo clones were available for further analysis.

All STECper isolates belonged to only four genoserotypes (O26:H11, O156:H25, O165:H25, O182:H25), while STECspo isolates were scattered between 28 genoserotypes with O157:H7 being the most prevalent followed by O6:H49 (Table 1). Five O antigens were detected in combination with different H antigens (O8:H21/HNT, O156:H8/H25, O157:H7/H12, O174:H21/H40, O177:H11/H25). The O-cluster encoding regions, flanked by galF and gnd, of the three genoserotypes exhibiting ONT were highly heterogeneous (identity of ≤46.12%) and therefore declared to be individual ONT types. Most isolates (n = 75, 42.1%) possessed a fliC gene encoding the H25 flagellin. Of these, 60 isolates (80.0%) belonged to STECper (O156, O165, O182), 14 (18.6%) to STECspo (O51, O172, O177, ONT), and one to the unrelated calf isolates (O177). The second most frequently found gene was fliC encoding H2 (15 isolates, 8.4%), but this flagellin gene was exclusively found in isolates with sporadic or unknown colonization types (O35, O84, O103, O112, O128, O150, O171, ONT). It has been reported that some cattle excrete O157:H7 STEC only for short time periods (48), that the O157:H7 STEC prevalence varies from herd to herd (49), and that the duration and amount of fecal shedding are isolate dependent (12). However, most data available are taken as evidence that O157:H7 STEC isolates persistently colonize cattle (12, 50). It was, therefore, unexpected that the O157:H7 isolates in our study had to be classified as STECspo. Experimental data show that O157:H7 is detectable in the feces of 100-day-old calves for at least 28 days after having been infected orally with 1010 CFU/dose on 3 consecutive days (51). This was considered persistent colonization because shedding was significantly longer than shedding of an apathogenic O43:H28 isolate in the same study (12 days postinfection [dpi]). We applied a more stringent definition of persistence based on field data rather than on experimental data, requiring fecal detection of the clone for at least 4 months. Experimental infection studies are indispensable for unveiling molecular mechanisms of colonization. However, only shedding curves can be a surrogate for the duration of shedding that occurs after low but repeated exposure of cattle to certain STEC clones under conditions of agricultural husbandry practices. In our study, classical serotyping did not allow correct classification of all isolates as STECper and STECspo, because some O antigens (e.g., O182) were not detected by the antisera. Even after genoserotyping had resulted in a regrouping of several isolates, serotypes did not distinguish STECper from STECspo as O156, H11, and H25 were present in both groups. Consequently, a more complex genetic pattern appears to be associated with the risk for certain STEC clones to be shed for extended periods of time. This can only be identified when the definition of the colonization pattern is based on epidemiological data, an approach adopted in this study.

For a closer look at the core genome of the isolates we used the MLST scheme according to Wirth et al. (37) and annotated the 178 isolates to 36 known and 2 new sequence types. Most prevalent were the sequence types ST300, ST119, ST11, and ST21 with 32, 22, 18, and 16 isolates, respectively (Table 1). The majority of the sequence types (23/36) could not be assigned to an ST complex (STC). Of the nine different ST complexes identified, STC11 and STC29 included the most isolates (18 and 29, respectively).

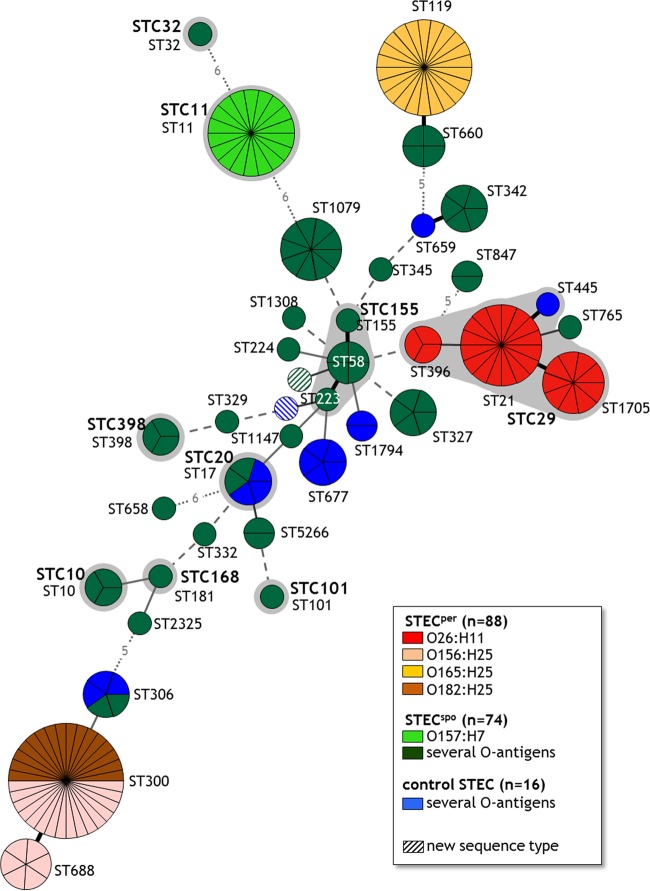

Similar to the genoserotyping results, all STECper isolates belonged to a limited number of sequence types (ST21, ST119, ST300, ST396, ST688, ST1705), whereas the STECspo isolates were represented by 30 different sequence types (Table 1). After combining genoserotypes and sequence types, STECper isolates formed three discrete and independent clusters within the minimum spanning tree (MST) (Fig. 1). While all O165:H25 isolates possessed the identical sequence type 119, the O156:H25 isolates were allocated to the types ST300 and ST688, which differ by only one nucleotide in the purA gene. ST300 additionally contained all O182:H25 isolates. The O26:H11 isolates belonged to three sequence types (ST21, ST396, ST1705), differing with only one nucleotide each in up to three alleles (adk, gyrB, purA) and were therefore grouped in the ST complex STC29. In the STECspo group, the O157:H7 isolates formed a single ST11 cluster, and the O6:H49 isolates clustered in ST1079. The remaining STECspo clones varied strikingly in their MLST allocation. Remarkably, neither a sequence type nor any ST complex contained both STECper and STECspo isolates. However, there were also no distinct groups containing either STECper or STECspo sequence types as we identified sequence types containing isolates of either colonization type, which were often closely related and might form a distinct ST cluster (ST119/ST600, ST21/ST765, ST300/ST688/ST306). The STECper-containing clusters are widely separated within the MST, suggesting that they evolved independently in parallel evolutionary branches by emerging from sporadically colonizing isolates.

FIG 1.

Minimum spanning tree based on MLST data indicating known sequence types (ST) and ST complexes (STC) of 178 bovine E. coli isolates The MLST classification is based on the nucleotide sequences of the genes adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA and the clonal complexes (shaded in gray) are named analogous to the MLST Database from Warwick University (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). BioNumerics version 6.6, minimum spanning tree of categorical character data. Each circle represents a single ST and each section of a circle a single isolate corresponding to the indicated ST. The number of different alleles between two STs is depicted by different types of lines: thick black line, 1-allele difference; thin black line, 2-allele difference; thin gray line, 3-allele difference; dashed gray line, 4-allele difference; dotted gray line, >4-allele difference (numbers of different alleles are indicated by numbers within the lines).

VAGs and VAG variants (DNA microarray analysis).

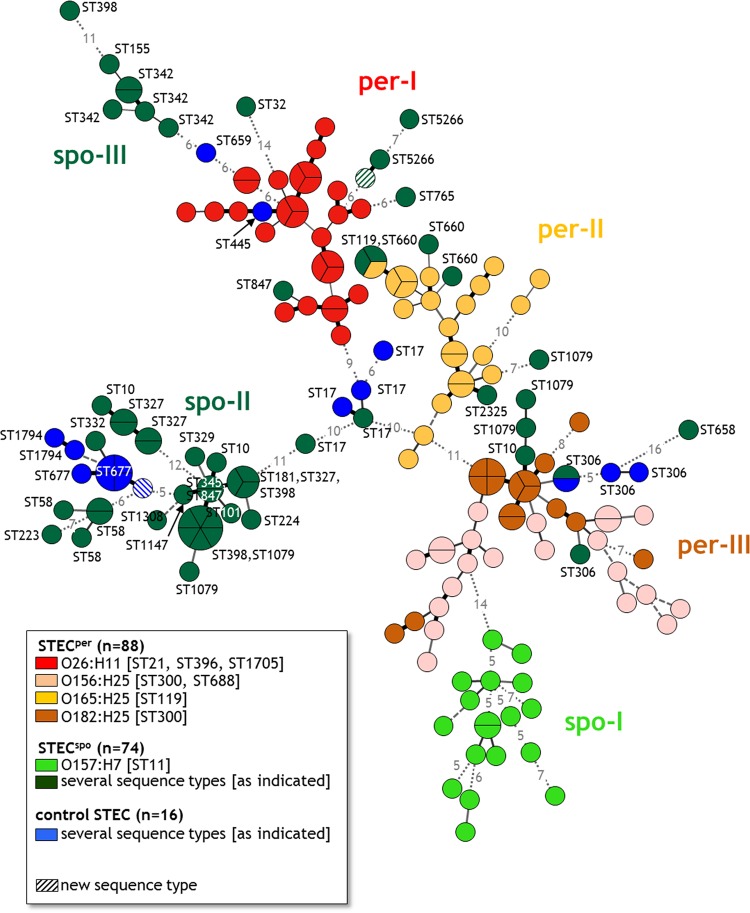

Since the tested markers representing the core genome did not distinguish clearly between STECper and STECspo isolates, we determined parts of the accessory genome of the isolates. The accessory genome is variable, often encoded on mobile elements and contains genes that are not present in all E. coli strains (52). Therefore, this part comprises mainly genes that are dispensable for bacterial survival within their normal host but promote fitness, virulence, the conquest of new niches, or resilience to adverse conditions. We analyzed the isolates using a DNA microarray that detects, among others, known E. coli VAGs and VAG variants. Of 127 VAG probes, 71 (55.9%) hybridized with the DNA of at least one of the isolates. Based on the presence or absence of those 71 VAG and VAG variants, the array identified 139 unique VAG patterns with 1 through 6 members (Fig. 2). By far the most patterns (115) contained only a single member and another 14 only two members, in line with the genome flexibility of E. coli. Only one of the patterns detected included both persistent (1× O165:H25, ST119) and sporadic (2× O172:H25, ST660) isolates, all belonging to closely related MLSTs with only one single nucleotide variation.

FIG 2.

Minimum spanning tree demonstrating the correlation between VAG pattern and MLST sequence type of 178 bovine E. coli isolates. Results of the microarray analysis. BioNumerics version 6.6, minimum spanning tree of binary character data. Each circle represents a single VAG pattern and each section of a circle a single isolate with the respective VAG pattern. The number of differing genes between two patterns is depicted by different types of lines: thick black line, 1-gene difference; thin black line, 2-gene difference; thin gray line, 3-gene difference; dashed gray line, 4-gene difference; dotted gray line, >4-gene difference (numbers of different genes are indicated by numbers within the lines). per-I to per-III, three clusters with predominantly persistent STEC isolates (STECper); spo-I to spo-III, three clusters with predominantly sporadic colonizing STEC isolates (STECspo).

After building an MST based on the binary data of the presence of VAGs and VAG variants, it was obvious that the VAG pattern correlated with both genoserotype and MLST (Fig. 2). The center of the MST consisted of five ST17 STECspo isolates, all belonging to the O103:H2 genoserotype, from which three main branches emerged. One branch contained only STECspo isolates and isolates with an unknown colonization type (spo-II). The second branch included the cluster per-I with O26:H11 STECper predominating and, connected to per-I, the STECspo cluster spo-III. The third branch comprised mainly STECper isolates with the cluster per-II (O165:H25) and the interconnected cluster per-III (O156:H25/O182:H25), before this third branch ended in the cluster spo-I containing mainly O157:H7 STECspo isolates. Four VAG patterns included STECspo isolates belonging to two or three different sequence types. Three of these VAG patterns in cluster spo-II were characterized by a significantly lower number of detected VAGs and/or VAG variants (n = ≤3), as other VAG patterns possessed up to 40 VAGs and/or VAG variants. One VAG pattern in cluster per-II included isolates from the closely related sequence types ST119 and ST660. Only STECspo isolates belonging to sequence types ST10, ST398, and ST1079 possessed unrelated VAG patterns in different clusters. While some isolates of the sequence types ST10 and ST1079 clustered with isolates of the genoserotype O156:H25 (cluster per-III), other ST10/ST1079 isolates were found in the big cluster spo-II containing STECspo, and one additional ST1079 isolate grouped with the O165:H25 isolates in cluster per-II. The three ST398 isolates were scattered among the clusters spo-II and spo-III. The origin of the isolates from only four different herds did not dominantly affect the presence of the VAGs because isolates of the control group belonging to sequence types ST10 and ST306 exhibited VAG patterns highly similar to those of the STECspo ST10 and ST306 isolates. The differentiation and composition of the main clusters were also confirmed by the hierarchical cluster analysis tool AGNES with an AC of 0.79, indicating that the clusters are strongly supported (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In a comparison of one representative isolate for each VAG pattern from the 139 isolates, the VAG and VAG variant genes most often detected were hemL (glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, n = 130), eae (4 variants of intimin, n = 107 through n = 118), nleB (non-LEE-encoded effector protein B, n = 112), nleA (4 variants of the non-LEE-encoded effector protein A, n = 100 through n = 111), lpfA (major subunit of long polar fimbriae, n = 102), astA (heat-stable enterotoxin EAST1, n = 96), hlyA (ehxA, EHEC hemolysin, n = 89), nleC (non-LEE-encoded effector protein C, n = 87), and tccP (Tir-cytoskeleton coupling protein, n = 85). A substantial number of isolates tested negative for stx1 and stx2 (Shiga toxins 1 and 2, respectively), although all of them had been initially selected as STEC. Loss of the bacteriophage occurred more often in some genoserotypes (O156:H8 [5 stx-negative of 5 isolates under study], O6:H49 [5/9], O157:H7 [3/18], O26:H11 [4/28], O165:H25 [2/22]), while other genoserotypes did not lose it at all (e.g., O156:H25, O172:H25, O182:H25). The loss of stx-encoding bacteriophages during in vitro cultivation has already been described by several authors, especially for O26 STEC (53–57). However, it was interesting to note that STECspo isolates were more often affected by bacteriophage loss than STECper isolates. This loss had occurred in 6 of 86 STECper (7.0%) and 29 of 76 STECspo (38.2%) isolates. The gene encoding Stx1 was significantly more abundant in STECper isolates, while most STECspo isolates harbored stx2. Free Stx2 phages are much more frequent in the environment (68% of the tested samples) than Stx1 phages (8%) (58), implying that the former are either less stably integrated in the E. coli genome or more mobile or their binding receptors are present only on a smaller number of environmental bacteria.

Persistent STEC isolates belonging to the O26:H11 cluster possessed between 23 and 33 genes for VAGs and/or VAG variants: isolates of the O156:H25/O182:H25 cluster between 16 and 29 and isolates of the O165:H25 cluster between 12 and 35 genes. Among the STECspo isolates, 22 to 40 genes for VAGs and/or VAG variants were detected in the O157:H7 cluster, while the next bigger group of STECspo isolates (O6 isolates, n = 9) contained only 3 to 20 genes. A comparison of the mean number of genes for VAGs and/or VAG variants in the different groups of isolates made it obvious that O157 STECspo isolates had significantly more VAGs per isolate than O156:H25/O182:H25 STECper isolates, the isolates of the STECspo group with several antigens, and the calf isolates with unknown colonization types (P ≤ 0.001; Kruskal-Wallis post hoc Scheffé test). For a set of human STEC isolates, the results of the microarray analysis were published by de Boer et al. (59). The numbers of VAGs and/or VAG variants in their O26:H11 (29 to 35 genes), O157:H7 (32 genes), O165:NM (33 genes), and O182:H25 (25 to 27 genes) isolates match ours, indicating that the numbers of VAGs and/or VAG variants seem to be serotype specific.

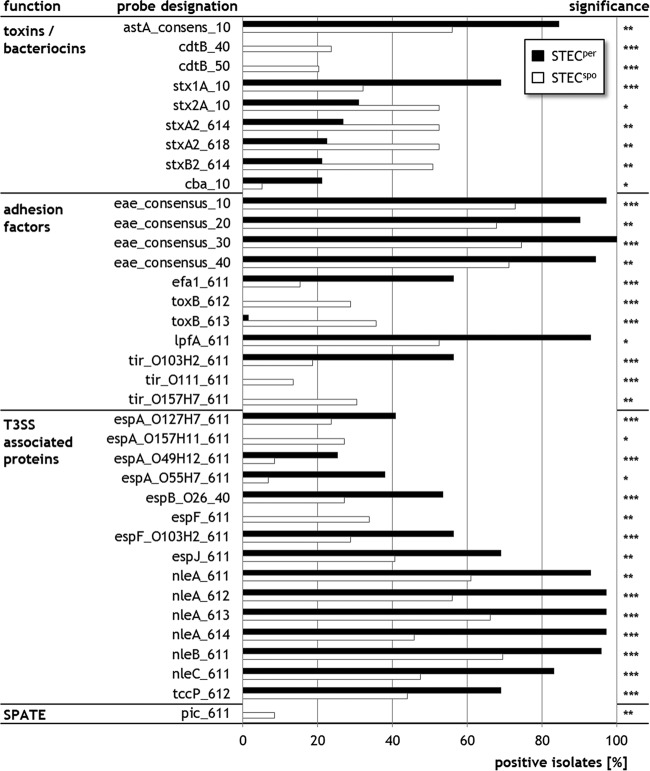

A comparison of 130 isolates with known colonization types, with one isolate representing each VAG pattern, revealed that STECper (n = 71) isolates possessed significantly more often genes encoding, among others, factors involved in adherence (eae, efa-1/lifA [EHEC factor for adherence], lpfA, tccP), effector proteins from a type III secretion system (T3SS) (espB, espJ), non-LEE encoded effectors (nleA, nleB, nleC), and Shiga toxin type 1 (χ2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). In contrast, STECspo isolates (n = 59) encoded more often Shiga toxin type 2 or ToxB, a protein involved in adherence. Interestingly for the genes tir (translocated intimin receptor) and the T3SS proteins espA and espF, the predominance was variant dependent, e.g., for tir the variant tirO103:H2 (corresponding to tir-β1 according to Garrido et al. [60]) occurred significantly more often in STECper isolates, while the variants tirO111 (tir-γ2/θ) and tirO157:H7 (tir-γ1) were more often detected in STECspo isolates.

FIG 3.

VAGs and VAG variants that occur with significant differences in STECper and STECspo isolates. Results of the microarray analysis considering only one representative isolate per VAG pattern. The figure depicts only those VAGs and VAG variants that differ in the detection frequency between persistent (STECper, n = 71) and sporadic STEC (STECspo, n = 59). χ2 test, two-tailed: ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05. T3SS, type III secretion system; SPATE, serine protease autotransporter.

In conclusion, a comparison of the parts of the core (genes encoding the serotype and housekeeping genes for the MLST) and accessory genomes (virulence-associated genes [VAGs]) did not allow the identification of defining gene patterns that correlate with the colonization type of the isolates in the bovine host. It became obvious, however, that within the MST of the core genome, persistent colonizing isolates (STECper) were located at the ends of branches, indicating a more distinct evolution from that of most of the sporadic colonizing isolates (STECspo). Only O157:H7 STECspo isolates of sequence type 11 also separated from the other STECspo isolates. In contrast, STECper isolates grouped close to the center of the VAG-based MST, while the O157:H7 STECspo and most of the remaining STECspo isolates clearly separated at the ends of the branches. This might be a hint that, even with clearly distinct genetic backbones, STECper isolates acquire similar sets of accessory genes. These seem to be more stably integrated in STECper genomes than in STECspo genomes as shown for the stx genes (lost in 7% versus 38.2%), supporting our hypothesis that STECper isolates act as sustained and continuous sources of VAGs in the bovine intestinal tract and therefore play a pivotal role in the evolution of putative EHEC.

The observation that three of four STECper genoserotypes possess predominantly stx1 (O26:H11, O156:H25, O182:H25), while STECspo genoserotypes are significantly more often positive for stx2 is consistent with the observation that calves are first colonized by an STEC-1 population, which is later expanded by the occurrence of STEC-2 isolates (16, 35, 61), implying that stx1-positive E. coli are particularly adopted to be part of the normal microbiota in the bovine host.

Even though only four cattle herds were sampled, albeit intensively, we detected 4 (O26, O103, O145, O157) of the 5 (additionally O111) EHEC O antigens, which define strains that account for most of the human HUS cases in Germany (31, 62, 63). Three of these were recognized as STECspo. These results substantiate our assumption that the sporadic colonization type of some putative EHEC strains in cattle may impair the identification of the infection source by epidemiological investigations during a human outbreak.

Measures to reduce pathogen shedding in livestock in order to protect humans against EHEC infections have been suggested earlier and tested both experimentally and in field studies (64). Targeting STECper isolates within the bovine host would minimize the E. coli VAG pool, reducing the risk of evolution of new zoonotic strains. Several attempts to develop vaccines against STEC in cattle were of limited success in field applications probably due to their limitation to single STEC subpopulations (e.g., serotype or presence of the LEE locus). Accordingly, a combination of different vaccine antigens was most effective in reducing fecal shedding (65). With the identification of serotypes (O26:H11, O156:H25, O165:H25, O182:H25) and VAGs correlating with a persistent colonization type in bovine STEC (among others stx1, efa-1, tccP, espB, nleA), the current study provides proof of principle that analysis of the accessory genome of a significant number of STEC strains with various colonization patterns should allow the identification of common genomic patterns which can be targeted by broadly effective vaccines to prevent human infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Birgit Mintel and Susann Schares (both FLI, Greifswald-Insel Riems), Anke Hinsching (FLI, Jena), and Petra Krienke (FU Berlin) for their excellent technical assistance and Dirk Höper (FLI, Greifswald-Insel Riems) for his constructive support by analyzing the DNA microarray results.

Author contributions were as follows: S.A.B., C.M., L.H.W., and L.G. designed the research; S.A.B., I.E., D.P., and L.G. performed the research; S.A.B., C.B., T.S., and A.B. analyzed data; and S.A.B., C.B., and C.M. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00909-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karmali MA, Petric M, Lim C, Fleming PC, Arbus GS, Lior H. 1985. The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis 151:775–782. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean-Nystrom EA, Bosworth BT, Cray WC Jr, Moon HW. 1997. Pathogenicity of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the intestines of neonatal calves. Infect Immun 65:1842–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karmali MA, Gannon V, Sargeant JM. 2010. Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC). Vet Microbiol 140:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL. 2005. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982−2002. Emerg Infect Dis 11:603–609. doi: 10.3201/eid1104.040739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman PA. 2000. Sources of Escherichia coli O157 and experiences over the past 15 years in Sheffield, UK. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol 29:51S–60S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell BP, Goldoft M, Griffin PM, Davis MA, Gordon DC, Tarr PI, Bartleson CA, Lewis JH, Barrett TJ, Wells JG, Baron R, Kobayashiet J. 1994. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers. The Washington experience. JAMA 272:1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilden J Jr, Young W, McNamara AM, Custer C, Boesel B, Lambert-Fair MA, Majkowski J, Vugia D, Werner SB, Hollingsworth J, Morris JG Jr. 1996. A new route of transmission for Escherichia coli: infection from dry fermented salami. Am J Public Health 86:1142–1145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.8_Pt_1.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferens WA, Hovde CJ. 2011. Escherichia coli O157:H7: animal reservoir and sources of human infection. Foodborne Pathog Dis 8:465–487. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheutz F, Strockbine N. 2005. Genus I. Escherichia, p 607–624. In Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed Springer US, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao YT, Miller MF, Loneragan GH, Brooks JC, Echeverry A, Brashears MM. 2014. Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in U. S. retail ground beef J Food Prot 77:1188–1192. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellmann A, Bielaszewska M, Kock R, Friedrich AW, Fruth A, Middendorf B, Harmsen D, Schmidt MA, Karch H. 2008. Analysis of collection of hemolytic uremic syndrome-associated enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis 14:1287–1290. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong KC, Hiki O, Kang MY, Park D, Kaspar CW. 2013. Prevalent and persistent Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains on farms are selected by bovine passage. Vet Microbiol 162:912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe RM, Munns K, Selinger LB, Kremenik L, Baines D, McAllister TA, Sharma R. 2010. Factors influencing the persistence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 lineages in feces from cattle fed grain versus grass hay diets. Can J Microbiol 56:667–675. doi: 10.1139/W10-051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verstraete K, Reu K, Van Weyenberg S, Pierard D, De Zutter L, Herman L, Robyn J, Heyndrickx M. 2013. Genetic characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O157, O26, O103, O111 and O145 isolates from humans, food, and cattle in Belgium. Epidemiol Infect 141:2503–2515. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monaghan Á, Byrne B, Fanning S, Sweeney T, McDowell D, Bolton DJ. 2011. Serotypes and virulence profiles of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from bovine farms. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:8662–8668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06190-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw DJ, Jenkins C, Pearce MC, Cheasty T, Gunn GJ, Dougan G, Smith HR, Woolhouse ME, Frankel G. 2004. Shedding patterns of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli strains in a cohort of calves and their dams on a Scottish beef farm. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:7456–7465. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7456-7465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menrath A, Wieler LH, Heidemanns K, Semmler T, Fruth A, Kemper N. 2010. Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli: identification of non-O157:H7-Super-Shedding cows and related risk factors. Gut Pathog 2:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geue L, Segura-Alvarez M, Conraths FJ, Kuczius T, Bockemühl J, Karch H, Gallien P. 2002. A long-term study on the prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) on four German cattle farms. Epidemiol Infect 129:173–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geue L, Schares S, Mintel B, Conraths FJ, Muller E, Ehricht R. 2010. Rapid microarray-based genotyping of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serotype O156:H25/H−/Hnt isolates from cattle and clonal relationship analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5510–5519. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00743-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geue L, Selhorst T, Schnick C, Mintel B, Conraths FJ. 2006. Analysis of the clonal relationship of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroup O165:H25 isolated from cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2254–2259. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2254-2259.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geue L, Klare S, Schnick C, Mintel B, Meyer K, Conraths FJ. 2009. Analysis of the clonal relationship of serotype O26:H11 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:6947–6953. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00605-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creuzburg K, Schmidt H. 2007. Molecular characterization and distribution of genes encoding members of the type III effector nleA family among pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J Clin Microbiol 45:2498–2507. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00038-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielaszewska M, Prager R, Vandivinit L, Musken A, Mellmann A, Holt NJ, Tarr PI, Karch H, Zhang W. 2009. Detection and characterization of the fimbrial sfp cluster in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O165:H25/NM isolates from humans and cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:64–71. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01815-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eklund M, Leino K, Siitonen A. 2002. Clinical Escherichia coli strains carrying stx genes: stx variants and stx-positive virulence profiles. J Clin Microbiol 40:4585–4593. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4585-4593.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Land M, Hauser L, Jun SR, Nookaew I, Leuze MR, Ahn TH, Karpinets T, Lund O, Kora G, Wassenaar T, Poudel S, Ussery DW. 2015. Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing. Funct Integr Genomics 15:141–161. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaas RS, Friis C, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM. 2012. Estimating variation within the genes and inferring the phylogeny of 186 sequenced diverse Escherichia coli genomes. BMC Genomics 13:577. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferdous M, Friedrich AW, Grundmann H, de Boer RF, Croughs PD, Islam MA, Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, Kooistra-Smid AMD, Rossen JWA. 4 April 2016. Molecular characterization and phylogeny of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates obtained from two Dutch regions using whole genome sequencing. Clin Microbiol Infect doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. 1995. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith HW, Green P, Parsell Z. 1983. Vero cell toxins in Escherichia coli and related bacteria: transfer by phage and conjugation and toxic action in laboratory animals, chickens and pigs. J Gen Microbiol 129:3121–3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denamur E. 2011. The 2011 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 German outbreak: a lesson in genomic plasticity. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:1124–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eichhorn I, Heidemanns K, Semmler T, Kinnemann B, Mellmann A, Harmsen D, Anjum MF, Schmidt H, Fruth A, Valentin-Weigand P, Heesemann J, Suerbaum S, Karch H, Wieler LH. 2015. Highly virulent non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serotypes reflect similar phylogenetic lineages, providing new insights into the evolution of EHEC. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:7041–7047. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01921-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman MA, Menge C, Casey TA, Laegreid W, Bosworth BT, Dean-Nystrom EA. 2006. Bovine immune response to Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13:1322–1327. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00205-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lim JY, Sheng H, Seo KS, Park YH, Hovde CJ. 2007. Characterization of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 plasmid O157 deletion mutant and its survival and persistence in cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2037–2047. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02643-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jordan DM, Cornick N, Torres AG, Dean-Nystrom EA, Kaper JB, Moon HW. 2004. Long polar fimbriae contribute to colonization by Escherichia coli O157:H7 in vivo. Infect Immun 72:6168–6171. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.6168-6171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fröhlich J, Baljer G, Menge C. 2009. Maternally and naturally acquired antibodies to Shiga toxins in a cohort of calves shedding Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:3695–3704. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02869-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel RK, Jain M. 2012. NGS QC Toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One 7:e30619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, Karch H, Reeves PR, Maiden MC, Ochman H, Achtman M. 2006. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol 60:1136–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machado J, Grimont F, Grimont PA. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Res Microbiol 151:535–546. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iguchi A, Iyoda S, Kikuchi T, Ogura Y, Katsura K, Ohnishi M, Hayashi T, Thomson NR. 2015. A complete view of the genetic diversity of the Escherichia coli O-antigen biosynthesis gene cluster. DNA Res 22:101–107. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Rothemund D, Curd H, Reeves PR. 2003. Species-wide variation in the Escherichia coli flagellin (H-antigen) gene. J Bacteriol 185:2936–2943. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.9.2936-2943.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joensen KG, Tetzschner AM, Iguchi A, Aarestrup FM, Scheutz F. 2015. Rapid and easy in silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol 53:2410–2426. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00008-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anjum MF, Mafura M, Slickers P, Ballmer K, Kuhnert P, Woodward MJ, Ehricht R. 2007. Pathotyping Escherichia coli by using miniaturized DNA microarrays. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:5692–5697. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00419-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ballmer K, Korczak BM, Kuhnert P, Slickers P, Ehricht R, Hachler H. 2007. Fast DNA serotyping of Escherichia coli by use of an oligonucleotide microarray. J Clin Microbiol 45:370–379. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01361-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batchelor M, Hopkins KL, Liebana E, Slickers P, Ehricht R, Mafura M, Aarestrup F, Mevius D, Clifton-Hadley FA, Woodward MJ, Davies RH, Threlfall EJ, Anjum MF. 2008. Development of a miniaturised microarray-based assay for the rapid identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 31:440–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maechler M, Rousseeuw P, Struyf A, Hubert M, Hornik K. 2016. cluster: cluster analysis basics and extensions. R package version 2.0.4. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaufman L, Rousseeuw PJ. 2008. Agglomerative Nesting (Program AGNES), p 199−252. In Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ. doi: 10.1002/9780470316801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Besser TE, Hancock DD, Pritchett LC, McRae EM, Rice DH, Tarr PI. 1997. Duration of detection of fecal excretion of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle. J Infect Dis 175:726–729. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hancock DD, Besser TE, Rice DH, Herriott DE, Tarr PI. 1997. A longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157 in fourteen cattle herds. Epidemiol Infect 118:193–195. doi: 10.1017/S0950268896007212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shere JA, Bartlett KJ, Kaspar CW. 1998. Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 dissemination on four dairy farms in Wisconsin. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:1390–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamm K, Barth S, Stalb S, Liebler-Tenorio E, Teifke JP, Lange E, Tauscher K, Kotterba G, Bielaszewska M, Karch H, Menge C. Experimental infection of calves with Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak strain. Sci Rep, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lukjancenko O, Wassenaar TM, Ussery DW. 2010. Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes. Microb Ecol 60:708–720. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9717-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bielaszewska M, Prager R, Köck R, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Tschape H, Tarr PI, Karch H. 2007. Shiga toxin gene loss and transfer in vitro and in vivo during enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26 infection in humans. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:3144–3150. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02937-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bielaszewska M, Middendorf B, Köck R, Friedrich AW, Fruth A, Karch H, Schmidt MA, Mellmann A. 2008. Shiga toxin-negative attaching and effacing Escherichia coli: distinct clinical associations with bacterial phylogeny and virulence traits and inferred in-host pathogen evolution. Clin Infect Dis 47:208–217. doi: 10.1086/589245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mellmann A, Lu S, Karch H, Xu JG, Harmsen D, Schmidt MA, Bielaszewska M. 2008. Recycling of Shiga toxin 2 genes in sorbitol-fermenting enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:NM. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:67–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01906-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joris MA, Verstraete K, Reu KD, Zutter LD. 2011. Loss of vtx genes after the first subcultivation step of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli O157 and non-O157 during isolation from naturally contaminated fecal samples. Toxins (Basel) 3:672–677. doi: 10.3390/toxins3060672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mellmann A, Bielaszewska M, Karch H. 2009. Intrahost genome alterations in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Gastroenterology 136:1925–1938. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grau-Leal F, Quiros P, Martinez-Castillo A, Muniesa M. 2015. Free Shiga toxin 1-encoding bacteriophages are less prevalent than Shiga toxin 2 phages in extraintestinal environments. Environ Microbiol 17:4790–4801. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Boer RF, Ferdous M, Ott A, Scheper HR, Wisselink GJ, Heck ME, Rossen JW, Kooistra-Smid AM. 2015. Assessing the public health risk of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli by use of a rapid diagnostic screening algorithm. J Clin Microbiol 53:1588–1598. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03590-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garrido P, Blanco M, Moreno-Paz M, Briones C, Dahbi G, Blanco J, Blanco J, Parro V. 2006. STEC-EPEC oligonucleotide microarray: a new tool for typing genetic variants of the LEE pathogenicity island of human and animal Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strains. Clin Chem 52:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wieler LH, Sobjinski G, Schlapp T, Failing K, Weiss R, Menge C, Baljer G. 2007. Longitudinal prevalence study of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in dairy calves. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr 120:296–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karch H, Tarr PI, Bielaszewska M. 2005. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human medicine. Int J Med Microbiol 295:405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friedrich AW, Bielaszewska M, Zhang WL, Pulz M, Kuczius T, Ammon A, Karch H. 2002. Escherichia coli harboring Shiga toxin 2 gene variants: frequency and association with clinical symptoms. J Infect Dis 185:74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vande Walle K, Vanrompay D, Cox E. 2013. Bovine innate and adaptive immune responses against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and vaccination strategies to reduce faecal shedding in ruminants. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 152:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McNeilly TN, Mitchell MC, Corbishley A, Nath M, Simmonds H, McAteer SP, Mahajan A, Low JC, Smith DG, Huntley JF, Gally DL. 2015. Optimizing the protection of cattle against Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonization through immunization with different combinations of H7 flagellin, Tir, Intimin-531 or EspA. PLoS One 10:e0128391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.