Abstract

Cytotoxic memory T cells play a critical role in combating viral infections; however, in some diseases they may contribute to tissue damage. In HAM/TSP, HTLV-1 Tax 11–19+ cells proliferate spontaneously in vitro and can be tracked using the Tax 11–19 MHC Class I tetramer. Immediately ex vivo, these cells were a mix of CD45RA−/CCR7− TEM and CD45RA+/CCR7− TDiff memory CTL. The subsequent proliferating Tax 11–19 tetramer+ population expressed low levels of IL-7Rα, failed to respond to IL-7 and IL-15, and did not develop a TCM phenotype. Thus, chronic exposure to viral antigen may result in a sustained pool of TEM cells that home to the CNS and mediate the spinal cord pathology seen in this disease.

Keywords: Cytotoxic T cells, Memory, Viral infection

1. Introduction

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1) is the etiologic agent of both adult T-cell leukemia (ATL) (Hinuma et al., 1981; Poiesz et al., 1981; Yoshida et al., 1982) and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP) (Gessain et al., 1985; Osame et al., 1986; Rodgers-Johnson et al., 1985). HAM/TSP is a chronic inflammatory disorder, predominantly affecting the brain and spinal cord, and characterized by weakness, spasticity of the lower extremities, urinary incontinence, and hyperreflexia (Levin and Jacobson, 1997). Remarkably, in HAM/TSP A2+ patients up to 30% of circulating CD8 cells are specific for Tax 11–19, the immunodominant peptide from the viral transactivator protein Tax, with much higher frequencies found in patients with HAM/TSP, as compared with healthy carriers (Bieganowska et al., 1999; Jeffery et al., 1999; Sakai et al., 2001). HAM/TSP patients also have much higher proviral loads than healthy carriers suggesting that there is failed clearance of the virus by cytotoxic T cells (CTL) and this has been linked with disease severity (Manns et al., 1999; Nagai et al., 1998; Yamano et al., 2002). A direct pathogenic role for the HTLV-1 Tax specific CTL has been proposed based on their presence in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with HAM/TSP, and in CNS lesions where they likely mediate disease pathology by secreting inflammatory cytokines and proteases (Biddison et al., 1997; Jacobson et al., 1990; Kubota et al., 2002; Levin et al., 1997; Nagai et al., 2001a,b).

A fundamental goal in immunology is to define the mechanisms that allow the maintenance and rapid regeneration of effector memory T cell responses in order to improve our ability to prime protective immune responses and combat damaging ones. Human memory T-cells can be divided into four subpopulations based on their expression of CD45RA and CCR7. Naïve T cells (CD45RA+/CCR7+) are the major pool of thymic emigrants that migrate to secondary lymph node structures in search of their cognate antigen. Central memory T-cells (TCM) (CD45RA−/CCR7+) define a pool of cells that have been activated, proliferated, and maintained the ability to migrate to lymph nodes where they can stimulate dendritic cells and B cells, but may be less efficient at mediating immediate effector functions (Sallusto et al., 2004; Sallusto et al., 1999). Effector memory T-cells (TEM) (CD45RA−/CCR7−) have a rapid effector function, proliferate less well, but are capable of migrating to tissue sites of inflammation (Sallusto et al., 1999, 2004). A terminally differentiated effector memory cell population (CD45RA+/CCR7−) has also been described, but not well characterized, and may have a limited proliferative capacity (Champagne et al., 2001).

To follow the differentiation of antigen-specific memory cells, we studied HTLV-1+ A2+ HAM/TSP patients with chronic neurologic disease. A hallmark of HTLV-1 infection is the spontaneous proliferation of T cells from immediately ex vivo peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) isolated from these HAM/TSP patients (Itoyama et al., 1988; Jacobson et al., 1988; Sakai et al., 2001; Usuku et al., 1988). This spontaneously proliferating population is highly enriched for HTLV-1-specific CD8+ memory CTLs recognizing the Tax 11–19 peptide that is produced as the virus reactivates from chronically infected cells (Sakai et al., 2001). Cells expressing the Tax protein were previously shown to peak by 12 h and persist until 72 h in vitro (Hanon et al., 2000; Sakai et al., 2001). HTLV-1 represents an ideal system in which to track the fate of the ex vivo antigen-specific memory CTL and show the reconstitution of effector memory as new viral antigen is released, as the ex vivo culture system contains no exogenous antigens, cytokines, or other stimulants. Thus, this ex vivo system may better reflect what is occurring naturally in a chronic viral infection in which there is repeated intermittent exposure to viral antigen.

Herein, we show that HTLV-1 Tax tetramer positive cells are CCR7−/IL-7Rαlo+ immediately ex vivo. Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells lose tetramer staining during early activation in vitro consistent with activation-induced TCR down-regulation, but reappeared at days 6–7, and were again predominantly CCR7/IL-7Rαlo+. This population only showed minimal conversion to the TCM pool, remaining CCR7−, while displaying extensive expansion (up to 30% of CD8s) and effector properties (IFN-γ and Granzyme B production) for up to 25 days in culture before reaching clonal exhaustion. Isolated Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells failed to proliferate or survive in response to exogenous IL-7 and IL-15 outside of their parent cultures consistent with impaired antigen independent memory generation. Thus in this chronic infection it appears that continuous exposure to viral antigen results in failed long-term TCM memory and maintenance of large numbers of damaging TEM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

PBMC were isolated by Ficoll density gradient from peripheral blood of five HLA-A2+ HAM/TSP patients and five A2+ HTLV-1 seronegative controls. All samples were taken with IRB-approved informed consent. Cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen until use, when they were thawed and placed in culture in RPMI supplemented with 10% human sera, 1% L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Proviral load was assessed as described previously (Yamano et al., 2002).

2.2. Phenotypic characterization and flow cytometry

At various points in culture, PBMC were harvested, washed, and resuspended in PBS 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), and incubated with various antibody combinations: APC-conjugated anti-human CCR7, APC-conjugated IL-7Rα (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), FITC-CD45RA (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), or PerCP-CD8 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or isotype-matched controls for 30 min at 4 °C. Stained cells were then washed and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde. To identify the HTLV-1-specific cells, PBMC were incubated 30 min at 4 °C with a PE-conjugated Tax 11–19/HLA-A201 tetramer provided by NIAID MHC Tetramer Core Facility, Atlanta, GA. The Tax 11–19 peptide is the dominant epitope recognized by HTLV-1 HLA-A201-restricted CD8 cells in HAM/TSP patients (Koenig et al., 1993; Parker et al., 1992). The CMV pp65 tetramer was used as a control (Beckman Coulter, San Diego, CA). Dead cells were stained with ethidium monoazide (EMA) a fixed cell viability probe, which enters cells with membrane damage and irreversibly labels the nucleic acids (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Flow cytometric samples were analyzed on a BD FACS Calibur 4-color machine using BD Cellquest Software for analysis. Cells were gated on either the live CD8 positive lymphocytes or the live Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population with the quadrants set on the appropriate isotype-matched controls.

2.3. CFSE proliferation and tracking

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) was used to visualize dividing cells as described previously (Crawford et al., 2004; Karandikar et al., 2002). In brief, PBMC isolated from HAM/TSP patients were labeled with 2.5 μm CFSE per 107 cells for 10 min at 37 °C. Labeled cells were washed three times with PBS/1% FCS and then cultured, as described above. Proliferation of HTLV-1-specific cells was analyzed by staining the CFSE-labeled cells with the PE-conjugated Tax 11–19 tetramer using flow cytometry. In the CFSE tracking experiments, the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells were isolated, as described below, labeled with CFSE, and returned to culture with the unlabeled patient-matched PBMC fraction. The division of the Tax 11–19 positive cells was followed using the Tax 11–19 tetramer and flow cytometry.

2.4. Magnetic sorting and cytokine stimulation of Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells

Tax 11–19 positive cells were isolated from HAM/TSP PBMCs using the Tax 11–19 PE-conjugated tetramer and magnetic cell sorting (MACS anti-PE microbeads) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity of the isolated cells was assessed using the Tax 11–19 tetramer and flow cytometry. The Tax 11–19 depleted PBMC were followed for over 14 days using the Tax 11–19 tetramer and flow cytometry to determine whether the Tax 11–19 positive population regenerated in vitro. For comparison, PBMC from the identical patient were cultured without depleting the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population. In the IL-7/IL-15 experiments, the Tax 11–19 positive cells were incubated with either media alone or with 10 ng/ml of IL-7 and IL-15 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), in duplicate. As a control, an equivalent number of CD8 cells, isolated using magnetic sorting (anti-CD8 microbeads) following the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), were also incubated with media or with IL-7 and IL-15. After 72 h of incubation, cells were pulsed with 0.5–1 μCi 3H per well, incubated overnight at 37 °C; cells were then harvested and proliferation was measured with the Microbeta Trilux Scintillation Counter (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA).

2.5. Granzyme B and IFN-γ ELISA

Cell supernatants from the HAM/TSP PBMC cultures were harvested and tested for Granzyme B (Diaclone Research, France) and IFN-γ (Biosource International, Camarillo, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. We examined Granzyme B and IFN-γ levels in vitro from 3 patients at day 6 and one patient over a time course, days 1, 3, and 6.

3. Results

3.1. Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells from HAM/TSP patients proliferate spontaneously in vitro

PBMC from A2+ HAM/TSP patients were isolated and placed in culture with no exogenous stimulants for up to 25 days. Spontaneous proliferation was evident in the cultures by day 5 to 7, as measured by cell counts (data not shown), activation (Fig. 1), and CFSE (Fig. 2). PBMC isolated from normal donors did not spontaneously proliferate (data not shown). Tax 11–19-specific T-cells were characterized by four-color flow cytometry at day 0; the initial phenotype of this population was TEM (CD8+/CD45RA−/CCR7−) and TDiff (CD8+/CD45RA+/CCR7−) cells (Table 1). The Tax 11–19-specific T-cells that were present at day 0, decreased in number over the next several days to undetectable or very low levels (Figs. 1 and 2B), which suggested that this population might have died or down-regulated their TCR. At days 5 to 8, we detected an expanding population of Tax 11–19-specific T-cells consistent with antigen-specific cell activation in response to the known expression of viral Tax protein between 12 and 72 h in vitro (Hanon et al., 2000; Sakai et al., 2001) (Figs. 1 and 2B). To determine the level of background tetramer binding, the isolated A2+ HAM/TSP PBMC were stained with the pp65 CMV tetramer; no CMV pp65 positive population was detected (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells from A2+ HAM/TSP patients proliferate spontaneously in vitro. The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population was detected ex vivo in five A2+ HAM/TSP patients using the Tax 11–19 tetramer and flow cytometry. The live lymphocyte population was gated and representative results are shown.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous proliferation is visible by day 5 in vitro. CFSE-based proliferation assays were performed on PBMC isolated from three A2+ patients with HAM/TSP; representative results are shown. Cells were gated on the live lymphocyte population. (A) By day 5, a dilution of the CFSE (x-axis) is seen, indicating cell division is occurring, as indicated by arrow. (B) Cell division of the CFSE labeled HTLV-1-specific population was measured using the Tax 11–19 tetramer and flow cytometry. CFSE staining is measured on the x-axis and Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells are shown on the y-axis. The percent of Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells is indicated.

Table 1.

Patient summary

| Sex | Duration of disease (years) | Age at sampling | Proviral load | % Tax 11–19a | % TEMb | % TDiffb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 30 | 59 | 25 | 1 | 63 | 38 |

| M | 16 | 53 | 81 | 4 | 50 | 50 |

| F | 16 | 64 | 87 | 12 | 12 | 80 |

| M | 23 | 64 | 23 | 5 | 59 | 35 |

| F | 19 | 58 | 36 | 3 | 64 | 35 |

Within live lymphocyte gate.

Within Tax 11–19 tetramer positive gate.

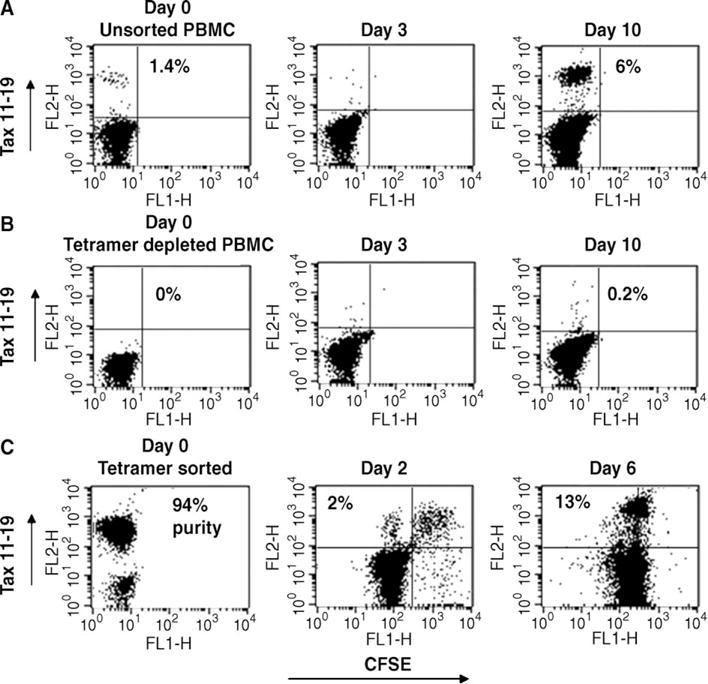

To examine the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells further, PBMC from A2+ HAM/TSP patients were labeled with CFSE prior to culture and cell proliferation was examined by FACS. Proliferation was visible in all cultures by days 5 to 6 (Fig. 2A), correlating with the increased numbers of Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells (Fig. 1). The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells present in vitro initially disappeared by day 3 (Fig. 2B). A Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population reappeared by day 6 and was proliferating (Fig. 2B). Collectively, these findings confirm that the Tax 11–19-specific T-cells are expanding by day 6 of culture in vitro, but do not specifically address whether some of the original tetramer memory pool present at day 0 died and were reconstituted by a new pool of antigen-specific cells or rather that they escaped detection on days 1–4 by TCR down-regulation. To more definitively answer this question, we depleted 100% of the Tax tetramer positive cells from one PBMC sample and cultured these cells in parallel with wild type (undepleted) PBMC, which initially contained 1.4% HTLV-1 Tax tetramer cells (Fig. 3A,B). At day 3, neither culture had tetramer positive cells, as previously seen. By day 10, the wild type culture reconstituted a population (6%) of tetramer positive cells (Fig. 3A). However, no significant regeneration of this population was visible in the Tax 11–19 depleted culture, suggesting that the Tax 11–19 specific cells present at day 0 are the same ones expanding at day 7 and that their TCR is down-regulated in vitro (Fig. 3B). We next sorted Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells immediately ex vivo from an A2+ HAM/TSP patient, labeled them with CFSE, and then added them back to the parent PBMC culture in order to determine their fate. Some of the tetramer positive cells persist and have clearly divided, but some CSFE labeled cells appear to be losing tetramer staining. At day 6 none of the original Tax 11–19 tetramer stained cells could be detected (data not shown), but a de novo Tax tetramer stain revealed strong Tax 11–19 tetramer staining on divided cells, which provides further evidence that it was the original population of tetramer positive cells that proliferated in culture (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells transiently down-regulate their TCR during activation. To address whether the initial Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population present at day 0 died, PBMC isolated from an A2+ patient with HAM/TSP were divided into a wild type culture (no manipulation) or a depleted culture (removal of 100% of Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells by positive selection). Cells were allowed to proliferate spontaneously in order to determine the fate of the initial Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population using flow cytometry (gating on the live lymphocyte population). (A) The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells in the wild type cultured disappeared by day 3, reappearing by day 10, as seen previously (B). No significant regeneration of this population was visible in the Tax depleted culture, suggesting that the Tax 11–19-specific cells present at day 0 are the same cells expanding at day 10 and their TCR is down-regulated in vitro. (C) Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells were isolated from an A2+ HAM/TSP patient (94% purity), labeled with CFSE, and added back to the parent PBMC culture in order to follow their fate. The double-labeled Tax 11–19/CFSE cells are visible at day 2 and some have undergone division. In addition, variable degrees of Tax 11–19 tetramer staining can be seen on the CFSE positive cells indicating tetramer down-regulation. A de novo Tax tetramer stain revealed strong Tax 11–19 tetramer staining on divided cells, which provides further evidence that it was the original population of tetramer positive cells that proliferated in culture.

3.2. The Tax 11–19-specific T-cells are CCR7− TEM or TDiff cells in vitro

To determine the memory lineage of the proliferating tetramer positive memory CTL, we then tracked the expression of CD45RA and CCR7 on the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells as they proliferated in vitro. At day 0, the Tax 11–19-specific T-cells were either TEM (CD45RA−/CCR7−) or TDiff (CD45RA+/CCR7−) in all five A2+ HAM/TSP samples (Fig. 4A and Table 1). A low level of CCR7 expression was seen only transiently on the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells (Fig. 4A). For comparison, we examined the CD45RA/CCR7 expression on the Tax 11–19 tetramer negative cells and show the presence of a significant population of CCR7+ cells at day 0 and day 7 (Fig. 4B). At later stages in culture, there is an increase of CD45RA on a subset of the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells, demonstrating that terminally differentiated cells are re-generated in vitro (Fig. 4C). Eventually the cultures no longer proliferate and die. In order to gain further knowledge of the function of these Tax 11–19-specific T-cells, we examined expression of Granzyme B (Fig. 4D) and IFN-γ (Fig. 4E) from the supernatants of the HAM/TSP cultures. We found high levels of both being produced by these cells during this time period of cell activation and proliferation, evidence that these cells are functional effector cells as has been previously documented from HTLV-1 spinal cord (Kubota et al., 2002; Levin et al., 1997).

Fig. 4.

The Tax 11–19-specific T-cells are CCR7-TEM or terminally differentiated cells in vitro. To phenotype the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells, we examined the expression of CD45RA and CCR7 on PBMC isolated from 5 A2+ HAM/TSP patients as they proliferated in vitro. (A) The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells expressed little to no CCR7 on their surface immediately ex vivo and throughout the time course in vitro. Cells were gated on live Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells and quadrant markers were set using the appropriate isotype-matched controls. (B) As a comparison, we also examined CD45RA and CCR7 levels on tetramer negative cells showing that their phenotype differs from the HTLV-1-specific cells and have a CCR7 positive population. (C) A CD45RA positive population is seen at Day 21 in vitro. (D and E) Progressively higher levels of Granzyme B and IFN-γ were seen in the HTLV-1 cell supernatants during this time period of cell activation and proliferation.

3.3. HTLV-1 Tax tetramer cells fail to become antigen independent memory cells

Recent work to characterize the generation of memory cells in mice has demonstrated that IL-7 receptor alpha (IL-7Rα) expression enables effector cells to develop into functional long-lived memory cells in part by inducing Bcl-2 expression (Kaech et al., 2003). Thus, we examined IL-7Rα expression on the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells from 3 patients, as they proliferated in response to viral antigen release in vitro. Virtually all of the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells expressed low levels of IL-7Rα immediately ex vivo (Fig. 5A). However, throughout culture, the IL-7Rα levels remained relatively stable on the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population, similar to the IL-7Rα levels on the tetramer negative PBMC within the same culture. We did not see a shift to IL-7Rαhi in this antigen-specific population in vitro. Since the tetramer positive cells never fully converted to TCM, as indicated by the low levels of CCR7 expression on these cells, we suspected that this population had failed generation of long-term memory. Indeed, when removed from antigen by sorting from the parent culture (Fig. 5B), the tetramer positive cells failed to proliferate in response to IL-7 and IL-15 as compared to sorted CD8 T cells from an uninfected donor (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells express low levels of the IL-7Rα antigen. The level of IL-7Rα on the surface of Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells isolated from A2+ patients with HAM/TSP was assessed by flow cytometry. Cells were gated on the live Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population. (A) The Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells expressed low levels of IL-7Rα (thick lines); IL-7Rα levels on tetramer negative cells from the same culture are overlaid in the histograms for comparison (thin lines). Results from two of the three patients examined are shown. (B) Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells were isolated from the PBMC of an A2+ HAM/TSP patient (95% purity) and were cultured alone or with IL-7 and IL-15 to examine whether cytokine treatment could affect proliferation of this population in vitro. CD8 cells isolated from a normal donor were included for comparison. While IL-7/IL-15 treatment induced significant proliferation of the normal donor CD8 positive cells, there was no affect on the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells.

4. Discussion

The mechanisms involved in the generation of T cell memory are only beginning to be understood. Upon antigen stimulation, the CD8 T cell response has 3 distinct phases: expansion, contraction, and memory (Gourley et al., 2004). After the initial activation and expansion of CD8 cells in response to an antigen, there is a contraction phase in which 90–95%, of effector CD8 cells die via apoptosis. The remaining 5–10% of CD8 cells persist to become long-lived memory cells (Gourley et al., 2004). The lineage pattern that results in chronic memory cells remains unclear and may vary depending on the quality and the length of antigen stimulation. In acute infections, the original suggested lineage pattern was naïve→TCM→TEM. Several recent studies have found conflicting results and perhaps a more accurate, yet broader, description is naïve→effector→memory, in which the source of memory has mostly been shown to reside in the TCM pool as a result of conversion of a subset of TEM cells. Indeed TCM and TEM may not represent two independent subsets, but are interrelated pools through which exchange is determined by the dose and duration of antigen exposure (Champagne et al., 2001; Gourley et al., 2004; Harari et al., 2004; Northrop and Shen, 2004; Wherry et al., 2003). In acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, MHC class I tetramer tracking of antigen-specific cells revealed that TEM convert to TCM in the absence of antigen or proliferation and become antigen independent long-term memory cells (Wherry et al., 2003). In chronic LCMV infection, however, the antigen-specific CD8 T cells persist as TEM and there is failed generation of antigen independent proliferation and thus memory (Wherry et al., 2003, 2004). These cells fail to acquire the cardinal properties of memory CD8 T cells including antigen-independent persistence via homeostatic proliferation in response to IL-7 and IL-15. It has been hypothesized that under conditions of chronic exposure to antigen that T cells get caught in a cycle of continuous transition between effector→TEM, which favors homing to non-lymphoid tissues (Wherry et al., 2003, 2004). Alternatively, another study that employed a serial analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) α clonotypes specific for influenza A virus found no evidence for transition between TEM and TCM subsets and suggested that these subpopulations are largely independent sources of memory (Baron et al., 2003). A limitation of prior human studies of the lineage pattern of CD8 memory maintenance has been the inability to control the timing of antigenic exposure in vivo or ex vivo without adding exogenous peptide, and therefore difficulty in tracking antigen-specific responses over time (Champagne et al., 2001; Harari et al., 2004).

To gain a better understanding of the lineage differentiation pathways of CD8 memory during a chronic human viral infection, we studied a unique disease in which up to 30% of the antigen-specific memory CD8 T cells in A2+ patients infected with HTLV-1 proliferate in vitro in response to viral reactivation and Tax protein release in the first 12–72 h of culture (Sakai et al., 2001). Since this ex vivo culture system contains no exogenous antigens, cytokines, or other stimulants, it may more closely reflect what is occurring naturally in HAM/TSP patients. We demonstrate that the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population present initially is composed of TEM cells (CD45RA−/CCR7−) and TDiff memory cells (CD45RA+/CCR7−). This correlates with the previous finding that greater than 80% of HTLV-1 Tax 11–19-specific CD8+ cells from A2+ HAM/TSP patients were memory and/or effector cells upon ex vivo phenotyping with CD45RA and CD27 (Nagai et al., 2001a,b). By days 5–7 in vitro, the Tax 11–19 tetramer positive population proliferates vigorously. The spontaneous proliferation seen in HAM/TSP in vitro involves both IL-2 and IL-15, which are known to be up-regulated by Tax (Azimi et al., 1998; Cross et al., 1987; Inoue et al., 1986; Mariner et al., 2001). This increased cytokine production in HTLV-infected cultures produces an environment that promotes cell proliferation of both virally infected, as well as non-infected bystander cells, as seen in the CFSE-based proliferation assays. Indeed the proliferation of CD8 T cells in this system has been previously shown to be dependent on the presence of CD4 helper T cells (Sakai et al., 2001). The observed lineage pattern of tetramer positive cells being predominantly CCR7− TEM and with little conversion to TCM is remarkably consistent with the findings reported in the chronic LCMV model and supports the concept that in chronic infections there is continuous production of TEM that retain tissue homing effector functions, but fail to establish memory responses.

The transient loss of tetramer staining has been described in murine systems and was attributed to T cell receptor (TCR) down-regulation or decreased binding affinity (Engelhardt et al., 2005; Kambayashi et al., 2001). A recent study examining tetramer expression in humans infected with hepatitis B also reported tetramer negative cells that responded to viral peptide as measured by production of intracellular IFN-γ (Reignat et al., 2002). In this system, there was no loss of CD3 staining to suggest TCR down-regulation and tetramer staining could be induced after repeated CD8 T cell stimulation suggesting a state of partial tolerance. Herein, we show the same pattern of tetramer loss and gain, but the timing is more consistent with TCR down-regulation during cell activation. In addition, a small percentage of cells from tetramer depleted cultures proliferate suggesting that there are indeed some tetramer negative cells in vivo that retain the capacity to proliferate in response to viral Tax protein. Whether these tetramer negative cells have a different capacity to kill virally infected targets could not be ascertained. In this system, the predominant proliferative response derived from tetramer positive cells, but it will be critical to determine if the tetramer negative population is the source of long-term memory cells that evade activation induced cell death by TCR down-regulation or impaired responsiveness to viral antigen (Maile et al., 2005).

Increased IL-7Rα expression on effector cells correlated with increased survival signals and a decrease in apoptosis and it is these IL-7Rαhi cells that give rise to longer-lived memory cells after acute infection (Kaech et al., 2003; van Leeuwen et al., 2005). Interestingly, in the HTLV-1 system, IL-7Rα is expressed, but only at low levels and does not mediate an effective proliferative or survival signal in TEM. Sustained high levels of IL-2, as occurs in HTLV-1 because of Tax transactivation of IL-2, have been shown to suppress high IL-7Rα expression and this may explain why there is continuous TEM generation but absent TCM antigen independent memory to the virus (Xue et al., 2002). However, alternative mechanisms of impaired signaling downstream of the receptor may also be involved.

In summary, we utilized an ex vivo culture system to show that antigen-specific cytotoxic CD8 T cells in a chronic human infectious disease undergo rapid expansion, in response to release of viral antigen in culture. These cells rapidly become TEM with little conversion to TCM and failed generation of antigen independent proliferation and long-term memory similar to what has been described in chronic animal infections. These TEM cells have an immediate effector function and may migrate to sites of inflammation due to their lack of CCR7 expression. Thus, a continuous generation of TEM with impaired long-term memory and inability to keep the virus latent may provide one potential mechanism by which why these Tax 11–19 tetramer positive cells migrate to the CNS and mediate a pathological immune response resulting in HAM/TSP (Biddison et al., 1997; Kubota et al., 2002; Nagai et al., 2001a,b).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NS041435 (PAC) and NINDS, NIH intramural program (SJ).

Abbreviations

- TEM

T effector memory

- TCM

T central memory

- TDiff

T terminally differentiated memory

- HTLV

human T-cell lymphotropic virus

- CCR7

chemokine receptor-7

- IL-7Rα

interleukin-7 receptor alpha

- IFN-γ

interferon-gamma

References

- Azimi N, Brown K, Bamford RN, Tagaya Y, Siebenlist U, Waldmann TA. Human T cell lymphotropic virus type I Tax protein trans-activates interleukin 15 gene transcription through an NF-kappaB site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2452–2457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron V, Bouneaud C, Cumano A, Lim A, Arstila TP, Kourilsky P, Ferradini L, Pannetier C. The repertoires of circulating human CD8(+) central and effector memory T cell subsets are largely distinct. Immunity. 2003;18:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddison WE, Kubota R, Kawanishi T, Taub DD, Cruikshank WW, Center DM, Connor EW, Utz U, Jacobson S. Human T cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I)-specific CD8+ CTL clones from patients with HTLV-I-associated neurologic disease secrete proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinase. J Immunol. 1997;159:2018–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieganowska K, Hollsberg P, Buckle GJ, Lim DG, Greten TF, Schneck J, Altman JD, Jacobson S, Ledis SL, Hanchard B, Chin J, Morgan O, Roth PA, Hafler DA. Direct analysis of viral-specific CD8+ T cells with soluble HLA-A2/Tax 11–19 tetramer complexes in patients with human T cell lymphotropic virus-associated myelopathy. J Immunol. 1999;162:1765–1771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne P, Ogg GS, King AS, Knabenhans C, Ellefsen K, Nobile M, Appay V, Rizzardi GP, Fleury S, Lipp M, Forster R, Rowland-Jones S, Sekaly RP, McMichael AJ, Pantaleo G. Skewed maturation of memory HIV-specific CD8 T lymphocytes. Nature. 2001;410:106–111. doi: 10.1038/35065118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford MP, Yan SX, Ortega SB, Mehta RS, Hewitt RE, Price DA, Stastny P, Douek DC, Koup RA, Racke MK, Karandikar NJ. High prevalence of autoreactive, neuroantigen-specific CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis revealed by novel flow cytometric assay. Blood. 2004;103:4222–4231. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SL, Feinberg MB, Wolf JB, Holbrook NJ, Wong-Staal F, Leonard WJ. Regulation of the human interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain promoter: activation of a nonfunctional promoter by the transactivator gene of HTLV-I. Cell. 1987;49:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt KR, Richter K, Baur K, Staeheli P, Hausmann J. The functional avidity of virus-specific CD8+ T cells is down-modulated in Borna disease virus-induced immunopathology of the central nervous system. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:487–497. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessain A, Barin F, Vernant JC, Gout O, Maurs L, Calender A, de The G. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type-I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;2:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourley TS, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, Ahmed R. Generation and maintenance of immunological memory. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanon E, Hall S, Taylor GP, Saito M, Davis R, Tanaka Y, Usuku K, Osame M, Weber JN, Bangham CR. Abundant tax protein expression in CD4+ T cells infected with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) is prevented by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2000;95:1386–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari A, Vallelian F, Pantaleo G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of antigen-specific CD4 T cells under different conditions of antigen persistence and antigen load. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3525–3533. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinuma Y, Nagata K, Hanaoka M, Nakai M, Matsumoto T, Kinoshita KI, Shirakawa S, Miyoshi I. Adult T-cell leukemia: antigen in an ATL cell line and detection of antibodies to the antigen in human sera. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:6476–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J, Seiki M, Taniguchi T, Tsuru S, Yoshida M. Induction of interleukin 2 receptor gene expression by p40x encoded by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. EMBO J. 1986;5:2883–2888. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoyama Y, Minato S, Kira J, Goto I, Sato H, Okochi K, Yamamoto N. Spontaneous proliferation of peripheral blood lymphocytes increased in patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. Neurology. 1988;38:1302–1307. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson S, Zaninovic V, Mora C, Rodgers-Johnson P, Sheremata WA, Gibbs CJ, Jr, Gajdusek C, McFarlin DE. Immunological findings in neurological diseases associated with antibodies to HTLV-I: activated lymphocytes in tropical spastic paraparesis. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(Suppl):S196–S200. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson S, Shida H, McFarlin DE, Fauci AS, Koenig S. Circulating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for HTLV-I pX in patients with HTLV-I associated neurological disease. Nature. 1990;348:245–248. doi: 10.1038/348245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery KJ, Usuku K, Hall SE, Matsumoto W, Taylor GP, Procter J, Bunce M, Ogg GS, Welsh KI, Weber JN, Lloyd AL, Nowak MA, Nagai M, Kodama D, Izumo S, Osame M, Bangham CR. HLA alleles determine human T-lymphotropic virus-I (HTLV-I) proviral load and the risk of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3848–3853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambayashi T, Assarsson E, Chambers BJ, Ljunggren HG. IL-2 down-regulates the expression of TCR and TCR-associated surface molecules on CD8(+) T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3248–3254. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3248::aid-immu3248>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karandikar NJ, Crawford MP, Yan X, Ratts RB, Brenchley JM, Ambrozak DR, Lovett-Racke AE, Frohman EM, Stastny P, Douek DC, Koup RA, Racke MK. Glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) therapy induces CD8(+) T cell responses in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:641–649. doi: 10.1172/JCI14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig S, Woods RM, Brewah YA, Newell AJ, Jones GM, Boone E, Adelsberger JW, Baseler MW, Robinson SM, Jacobson S. Characterization of MHC class I restricted cytotoxic T cell responses to tax in HTLV-1 infected patients with neurologic disease. J Immunol. 1993;151:3874–3883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota R, Soldan SS, Martin R, Jacobson S. Selected cytotoxic T lymphocytes with high specificity for HTLV-I in cerebrospinal fluid from a HAM/TSP patient. J Neurovirology. 2002;8:53–57. doi: 10.1080/135502802317247811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MC, Jacobson S. HTLV-I associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP): a chronic progressive neurologic disease associated with immunologically mediated damage to the central nervous system. J Neurovirology. 1997;3:126–140. doi: 10.3109/13550289709015802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MC, Lehky TJ, Flerlage AN, Katz D, Kingma DW, Jaffe ES, Heiss JD, Patronas N, McFarland HF, Jacobson S. Immunologic analysis of a spinal cord-biopsy specimen from a patient with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I-associated neurologic disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:839–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703203361205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maile R, Siler CA, Kerry SE, Midkiff KE, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA. Peripheral “CD8 tuning” dynamically modulates the size and responsiveness of an antigen-specific T cell pool in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;174:619–627. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns A, Miley WJ, Wilks RJ, Morgan OS, Hanchard B, Wharfe G, Cranston B, Maloney E, Welles SL, Blattner WA, Waters D. Quantitative proviral DNA and antibody levels in the natural history of HTLV-I infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1487–1493. doi: 10.1086/315088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariner JM, Lantz V, Waldmann TA, Azimi N. Human T cell lymphotropic virus type I Tax activates IL-15R alpha gene expression through an NF-kappa B site. J Immunol. 2001;166:2602–2609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Usuku K, Matsumoto W, Kodama D, Takenouchi N, Moritoyo T, Hashiguchi S, Ichinose M, Bangham CR, Izumo S, Osame M. Analysis of HTLV-I proviral load in 202 HAM/TSP patients and 243 asymptomatic HTLV-I carriers: high proviral load strongly predisposes to HAM/TSP. J Neurovirology. 1998;4:586–593. doi: 10.3109/13550289809114225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Kubota R, Greten TF, Schneck JP, Leist TP, Jacobson S. Increased activated human T cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) Tax 11–19-specific memory and effector CD8+ cells in patients with HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis: correlation with HTLV-I provirus load. J Infect Dis. 2001a;183:197–205. doi: 10.1086/317932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M, Yamano Y, Brennan MB, Mora CA, Jacobson S. Increased HTLV-I proviral load and preferential expansion of HTLV-I Tax-specific CD8+ T cells in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with HAM/TSP. Ann Neurol. 2001b;50:807–812. doi: 10.1002/ana.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrop JK, Shen H. CD8+ T-cell memory: only the good ones last. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osame M, Usuku K, Izumo S, Ijichi N, Amitani H, Igata A, Matsumoto M, Tara M. HTLV-I associated myelopathy, a new clinical entity. Lancet. 1986;1:1031–1032. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker CE, Daenke S, Nightingale S, Bangham CR. Activated, HTLV-1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes are found in healthy seropositives as well as in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Virology. 1992;188:628–636. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90517-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Reitz MS, Kalyanaraman VS, Gallo RC. Isolation of a new type C retrovirus (HTLV) in primary uncultured cells of a patient with Sezary T-cell leukaemia. Nature. 1981;294:268–271. doi: 10.1038/294268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reignat S, Webster GJ, Brown D, Ogg GS, King A, Seneviratne SL, Dusheiko G, Williams R, Maini MK, Bertoletti A. Escaping high viral load exhaustion: CD8 cells with altered tetramer binding in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1089–1101. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers-Johnson P, Gajdusek DC, Morgan OS, Zaninovic V, Sarin PS, Graham DS. HTLV-I and HTLV-III antibodies and tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;2:1247–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90778-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai JA, Nagai M, Brennan MB, Mora CA, Jacobson S. In vitro spontaneous lymphoproliferation in patients with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I-associated neurologic disease: predominant expansion of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2001;98:1506–1511. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usuku K, Sonoda S, Osame M, Yashiki S, Takahashi K, Matsumoto M, Sawada T, Tsuji K, Tara M, Igata A. HLA haplotype-linked high immune responsiveness against HTLV-I in HTLV-I-associated myelopathy: comparison with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Ann Neurol. 1988;23(Suppl):S143–S150. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen EM, de Bree GJ, Remmerswaal EB, Yong SL, Tesselaar K, ten Berge IJ, van Lier RA. IL-7 receptor alpha chain expression distinguishes functional subsets of virus-specific human CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2005;106:2091–2098. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry EJ, Teichgraber V, Becker TC, Masopust D, Kaech SM, Antia R, von Andrian UH, Ahmed R. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:225–234. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry EJ, Barber DL, Kaech SM, Blattman JN, Ahmed R. Antigen-independent memory CD8 T cells do not develop during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16004–16009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue HH, Kovanen PE, Pise-Masison CA, Berg M, Radovich MF, Brady JN, Leonard WJ. IL-2 negatively regulates IL-7 receptor alpha chain expression in activated T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13759–13764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212214999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamano Y, Nagai M, Brennan M, Mora CA, Soldan SS, Tomaru U, Takenouchi N, Izumo S, Osame M, Jacobson S. Correlation of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) mRNA with proviral DNA load, virus-specific CD8(+) T cells, and disease severity in HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (HAM/TSP) Blood. 2002;99:88–94. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Miyoshi I, Hinuma Y. Isolation and characterization of retrovirus from cell lines of human adult T-cell leukemia and its implication in the disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2031–2035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]