Abstract

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) during pregnancy is associated with significant maternal and fetal risks. Prompt diagnosis and effective management during pregnancy can improve both maternal and fetal outcomes. However, there is no consensus with regard to conservative versus surgical management especially in the first and third trimester. We report three cases of PHPT associated with pregnancy that underwent parathyroidectomy each in a different trimester. Cases 1 and 2 were found to have hypercalcaemia and elevated parathyroid hormone levels in the second and first trimesters, respectively. Case 3 was known to have PHPT prenatally but previously declined parathyroidectomy. All three cases underwent parathyroidectomies during pregnancy without significant postoperative complications and all achieved favourable maternal and neonatal outcomes. Maternal hyperparathyroidism represents a preventable cause of maternal morbidity, with fetal morbidity and mortality. The benefits of parathyroidectomy with normalization of serum calcium in the mothers outweigh the risks of hypercalcaemia and suppression of the fetal parathyroid, especially where maternal vitamin D concentration is low.

Keywords: hypercalcaemia, maternal, hyperparathyroidism, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) in pregnancy is a serious condition as there are significant maternal and fetal risks associated with delayed diagnosis and untreated hypercalcaemia during pregnancy. The incidence of PHPT in pregnancy is rare, reported as 0.7% of all women with PHPT. However, the incidence may be under-reported due to the asymptomatic nature of the cases. The use of automated multianalysers may also explain the apparent increase in the incidence of hypercalcaemia. We report the outcomes of three cases of PHPT associated with pregnancy that underwent parathyroidectomy in each trimester.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

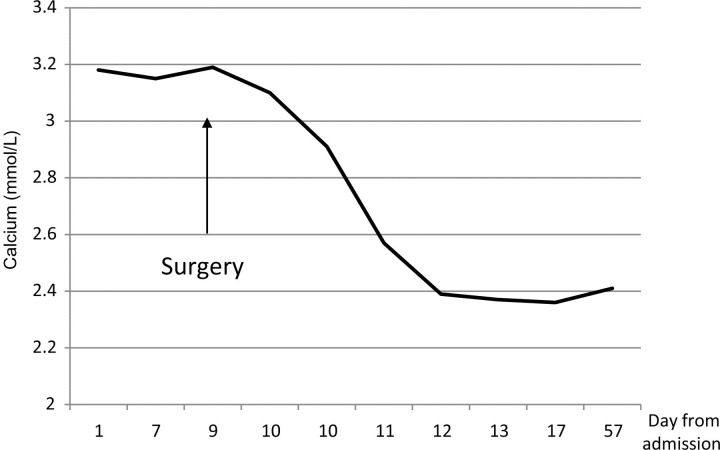

A 35-year-old Caucasian woman in her second pregnancy presented at 28 weeks gestation with polydipsia and polyuria. She had booked at 14 weeks and had regular antenatal care until 28 weeks. Investigations performed at that time revealed a corrected serum calcium of 3.08 mmol/L (normal range (NR) 2.15–2.55 mmol/L), phosphate 0.84 mmol/L (NR 0.8–1.4 mmol/L) and parathyroid hormone of 7.0 pmol/L (NR 1.1–6.8 ρmol/L), while renal and thyroid function and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D level were normal. Twenty-four-hour urinary calcium was 20.0 mmol/day (NR 2.5–10.0 mmol/day). Her obstetric history included an emergency caesarean section due to fetal distress at 41+5 weeks. Although she had pregnancy-induced hypertension in her first pregnancy, her blood pressure was well controlled without medication on this occasion and fetal growth was normal on ultrasound. An ultrasound of her neck showed a possible left superior parathyroid adenoma. Despite fluid rehydration she remained hypercalcaemic (Figure 1). A repeat ultrasound at a tertiary hospital at 33+4 weeks also revealed a possible left inferior parathyroid adenoma. She underwent neck exploration at 33+6 weeks, and the left superior and inferior parathyroid glands were removed. Although she had partial vocal cord palsy postoperatively, this recovered fully. She subsequently presented at 37 weeks gestation in spontaneous labour and was delivered by caesarean section for previous caesarean section and breech presentation. She delivered a healthy 2.92 kg female infant with Apgar scores of 6 at one minute and 10 at five minutes. The neonatal plasma serum calcium level at birth was 2.30 mmol/L (NR 2.13–2.62 mmol/L) and phosphate level 2.01 mmol/L (NR 1.6–2.9 mmol/L). The patient's serum calcium levels have remained normal following her parathyroidectomy.

Figure 1.

Corrected serum calcium levels of Case 1 patient before and during admission and at follow-up 60 days postoperation

Case 2

A 29-year-old West African woman in her first pregnancy presented at 10 weeks gestation with three weeks of vomiting and two days of suprapubic tenderness. Her corrected calcium was found to be 3.18 mmol/L, with an elevated parathyroid hormone level of 20.5 pmol/L and a low 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D at 16 nmol/L (NR 25–100 mmol/L). Twenty-four-hour urinary calcium was 11.04 mmol/day (NR 2.5–7.5 mmol/day). Urine culture grew Escherichia coli and the patient responded clinically to a five-day course of cephalexin. There were no renal calculi seen on ultrasound of the renal tract. Calcium levels remained elevated after a week of fluid rehydration and limited oral calcium intake (Figure 2). In order to correct her low vitamin D and treat her hypercalcaemia, parathyroid neck exploration was undertaken at 11 weeks gestation, during which a right superior parathyroid gland was removed which was confirmed histologically to be an adenoma. She was treated with vitamin D replacement and her calcium normalized postoperatively. Delivery was by emergency caesarean section at 40+3 weeks for significant meconium and suboptimal cardiotocograph in early labour. She delivered a healthy 2.580 kg female infant with Apgar scores of 9 at one minute and 10 at five minutes. The baby had transient reduced urine output and hypernatraemia (157 mmol/L, NR 135–145 mmol/L) which responded promptly to rehydration with intravenous fluids. Sodium levels returned to normal levels (142 mmol/L) within a few days.

Figure 2.

Corrected serum calcium levels of Case 2 patient during admission and at follow-up

Case 3

A 39-year-old Afro-Caribbean woman, Para 1 + 1, presented at 15 weeks gestation for antenatal booking. She was known to have PHPT and essential hypertension pre-pregnancy and had declined parathyroidectomy in her previous pregnancies. Neck ultrasound showed a 1.7 cm right inferior parathyroid adenoma and elevated corrected serum calcium at booking of 3.56 mmol/L and parathyroid hormone level of 36.4 pmol/L. She agreed to have neck exploration at 22 weeks gestation where a 28 × 22 × 16 mm parathyroid adenoma, confirmed histologically, was resected. Although her parathyroid hormone level was detectable seven days postoperatively, her corrected serum calcium normalized (Figure 3). She subsequently delivered by elective caesarean section at 39 weeks for previous caesarean section and breech presentation. She delivered a healthy 3.640 kg male infant with Apgar scores of 9 at one minute and 10 at five minutes. The baby had normal serum calcium levels of 2.34 mmol/L on day 1 and 2.13 mmol/L on day 2 of life.

Figure 3.

Corrected serum calcium levels of Case 3 patient during admission and at follow-up

DISCUSSION

Symptoms and signs

Fifty to eighty percent of gravid patients with PHPT are asymptomatic.1,2 Maternal PHPT may be undetected and present as neonatal tetany after delivery.3 Subtle symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, emotional lability and constipation may occur. Hypercalcaemia can also manifest as hyperemesis gravidarum, nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis and spontaneous abortion.4–6 If unrecognized, it is associated with increased maternal and fetal complications.

Calcium metabolism in pregnancy

During normal pregnancy, 20–30 g of calcium is actively transported across the placenta from the mother to the fetus.7 It was suggested that this active calcium transport is influenced by PTHrP (parathyroid hormone-related protein), and not PTH (parathyroid hormone), via a receptor unrelated to the PTH/PTHrP receptor.8 Eighty percent of this calcium transfer occurs during the third trimester,9 which leads to a higher concentration of ionized calcium in the fetal cord blood than in non-pregnant adults. Ionized calcium levels in pregnant women are the same as those in the non-pregnant state, but the total calcium level is decreased due to hypoalbuminaemia in pregnancy.8

In PHPT, prolonged maternal hypercalcaemia results in an increase in calcium transfer across the placenta, which leads to fetal hypercalcaemia. The high calcium levels during intrauterine life leads to suppression of fetal parathyroid function and fetal parathyroid gland development.10 Parathyroid glands were not found at autopsy in the neonate of a woman with PHPT,11 and low levels of fetal parathyroid hormone and 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D were found in cord blood.7 Due to fetal parathyroid development suppression, neonatal hypoparathyroidism is associated with hypocalcaemia, and tetany may occur soon after birth when the maternal calcium supply is no longer available to the neonate.12

Medical complications

Effect of hyperparathyroidism (HPT) on pregnancy

In the first review of literature in 1962, Ludwig13 reported a 50% complication rate in 40 pregnancies of 21 hyperparathyroid women. There were eight stillbirths, two neonatal deaths and 19% of the cases presented with symptomatic neonatal hypocalcaemia. In earlier reports, perinatal mortality has been reported to be as high as 25–31% and neonatal complication rates of 19–53%.11,13,14 In a large case series of 159 pregnancies complicated by PHPT, Shangold et al. 15 reported 13 spontaneous abortions, one intrauterine growth retardation, 11 intrauterine deaths, 35 cases of transient neonatal tetany, with one permanent hypoparathyroidism, and four neonatal deaths. Although the actual calcium values for these pregnancies were not mentioned, three of the cases presented in the series had elevated calcium levels of 3.6–3.75 mmol/L (normal range 2.13–2.64 mmol/L). Both of these authors included all obstetric cases, in which some had developed symptoms after the reported pregnancies. It was believed that by including only those pregnancies where diagnosis was certain would tend to overestimate the morbidity. The cause of fetal intrauterine growth retardation was thought to be due to premature calcification of the placenta, associated with maternal hyperparathyroidism.16

More recently, there has been a decline in perinatal morbidity and mortality from PHPT. Kelly et al. 17 demonstrated that the incidence of stillbirths and neonatal deaths associated with maternal PHPT have decreased from 27% in the period 1963–1975, to 5% in 1976–1990. This was attributed to an improved understanding of the condition, better diagnostic tests, earlier detection (automated blood sampling of calcium) and improved perinatal care.

Effect of hyperparathyroidism on neonates

In the cases reported above, appropriate treatment was associated with a favourable neonatal outcome and prevention of neonatal hypocalcaemia. All infants of maternal PHPT should be tested at birth and have regular check-ups for a few months after birth as hypocalcaemia can occur in up to 50% of infants of women with PHPT18 with the onset of symptoms from birth to up to two months postnatally.19,20 Clinically significant symptoms such as opisthotonus, tetany and seizures can be avoided by calcium supplementation promptly after birth. Recovery of parathyroid function occurs within three to five months,15 although rare cases of permanent hypoparathyroidism have been reported.13,21

Effect of pregnancy on hyperparathyroidism

Maternal complication rates have been reported to be as high as 67% with a mildly elevated mean serum calcium level of 3.23 ± 0.18 mmol/L at presentation.22 The incidence of hyperemesis gravidarum is increased in pregnant women with PHPT. Nephrolithiasis and pancreatitis associated with PHPT were also found to have a higher incidence during pregnancy, as compared with PHPT in non-pregnant cases.23 Hypercalcaemic crisis remains a significant danger, especially postpartum, when the transplacental calcium shunt from the mother to the fetus is removed. It presents with nausea, vomiting, weakness and changes in mental status, and can progress to uraemia, coma and death. The incidence of pre-eclampsia was higher in women with PHPT as compared with the general population (25% versus 5% respectively).24

Treatment

Conservative

Although some studies suggested that mild hypercalcaemia in asymptomatic pregnant women with PHPT can be safely managed conservatively,25,26 conservative treatments, such as increasing oral fluids and reducing oral calcium intake, did not normalize the serum calcium levels permanently throughout the pregnancy. In none of our three cases did oral or intravenous fluids normalize maternal hypercalcaemia. The maternal hyperparathyroidism will continue and drive maternal bone calcium loss. Furthermore, prolonged neonatal parathyroid suppression, resulting in neonatal hypocalcaemia, has been shown in asymptomatic maternal hyperparathyroidism.27 Surgery remains the definitive treatment for PHPT and should be considered the primary modality of treatment.13,14,28

Pharmacological

Loop diuretics can be used to facilitate fluid and sodium excretion in the patient requiring large volumes of intravenous normal saline to treat hypercalcaemia. However, loop diuretics will not treat the hyperparathyroidism per se. Bisphosphonates should be avoided during pregnancy as they readily cross the placenta.29 Bisphosphonates have been shown to decrease fetal bone growth in animal studies,30 although in humans, neonatal malformations or skeletal abnormalities were not found in 51 cases of women who were exposed to bisphosphonates before or during pregnancy.31 Although calcitonin can lower serum calcium level and does not cross the placenta,32 it is not recommended to be used in pregnancy33,34 as it led to low fetal birth weights in animal studies.

In women with HPT in whom surgery during pregnancy could not be performed, oral phosphate has been shown to be effective in lowering maternal serum calcium without causing neonatal hypocalcaemia. A daily dose of 1.5–3.0 mg inorganic phosphate was suggested.35 Oral phosphate can be associated with gastrointestinal side-effects such as diarrhoea.

Vitamin D supplementation in maternal PHPT

As demonstrated in Case 2, maternal PHPT can occur in conjunction with hypovitaminosis D. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low birthweight, neonatal hypocalcaemia, poor postnatal growth and bone fragility. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence now recommends vitamin D supplementation for at-risk pregnant women. Ideal vitamin D supplementation in maternal PHPT has not been defined. In one case series, oral calcium supplementation was routinely given to post-parathyroidectomy patients with maternal PHPT.36

Surgical

Sestamibi parathyroid scanning, which is widely used in tumour localization in non-pregnancy cases, is avoided during pregnancy due to radioactive exposure to the fetus. In this centre, parathyroid ultrasonography is the first-line investigation for preoperative tumour localization. Cases 1 and 3 demonstrate the utility of this investigation in pregnancy. In the largest series of maternal PHPT in 77 pregnancies, ultrasonography correctly identified the adenoma in 64% of cases.36

New surgical approaches, including unilateral neck exploration and minimally invasive parathyroidectomy, provide benefits of reduced postoperative pain and better cosmetic outcomes. Ultrasound-guided aspiration of suspected parathyroid nodule(s) with PTH measurement from the aspirate has been described in two cases of maternal PHPT to allow minimally invasive parathyroidectomy to be carried out successfully.37 Nevertheless, sound surgical technique and intra-operative judgement have a high impact on the success of the parathyroidectomy, regardless of the types of operative strategy.38

Women with PHPT who are planning to conceive should ideally be treated surgically prior to pregnancy. When PHPT is diagnosed during pregnancy, parathyroidectomy is traditionally considered safe during the second trimester9,39 whereas in the first trimester, opinions still vary regarding the optimal time for surgery. Some authors advocated delaying parathyroidectomy at least until the second trimester if the calcium level and symptoms are controlled.24 In a study reviewing six cases of hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy (out of 750 parathyroidectomies over 21-year period), four patients were diagnosed at a mean gestational age of 15 weeks. Three of the women underwent parathyroidectomies in the second trimester resulting in normalized maternal serum calcium levels and live births without neonatal complications.22 However, elevated maternal hypercalcaemia, ranging from 2.68 to 3.30 mmol/L, was associated with increased rate of fetal loss as compared with the general population. A 75% miscarriage rate was reported with maternal calcium level of 2.85 mmol/L or higher, but may still occur with only mildly elevated calcium levels.36 Our second case supports previous reports of parathyroidectomies performed in the first trimester, which led to normalization of maternal calcium and normal live births.17 Therefore, surgery should be considered in the first trimester to minimize the maternal and fetal risks associated with prolonged hypercalcaemia.

Surgery in the third trimester was previously believed to be risky as pre-term labour was considered as one of the postoperative complications. In a review of 38 women who underwent parathyroidectomy during pregnancy, a 58% perinatal complication rate was reported in seven women who were operated on in the third trimester, including premature delivery, intrauterine growth retardation, neonatal hypocalcaemia and stillbirth. However, these complications may not be due to surgery alone and may actually be the consequence of prolonged maternal hypercalcaemia.1 With preoperative localization, serial intra-operative PTH measurements and improved minimally invasive surgical techniques, operative time and postoperative complications can be significantly minimized. In a review of parathyroidectomies performed in the third trimester from 1970 to 2005,24 four out of 16 cases suffered with clinically significant maternal complications, which included severe pre-eclampsia, pancreatitis and renal failure. The authors also concluded that these complications were attributable to PHPT or the underlying pregnancy, rather than a direct complication of surgical intervention. Most of the surgical complications were not clinically significant and were due to transient postoperative hypocalcaemia in 62.5% of women, which was easily treated with calcium replacement. The incidence of clinically significant fetal complications from the surgery was only 5.9%, whereas the incidence of clinically significant fetal complications as a result of delayed diagnosis or surgery were as high as 23.5% in fetuses and 25% in mothers. Like the third case, there are more case reports in the literature of uncomplicated third trimester parathyroidectomy.40 Therefore, if maternal PHPT is diagnosed in the third trimester, surgery should be considered as in the first and second trimesters.

Surgery for PHPT offers the chance for cure of the high PTH concentration, thereby reducing the risk of fetal complications, as medical management is unlikely to normalize the calcium and will not normalize the PTH level. Surgical management also allows for optimal management of hypovitaminosis D, which untreated has a significant morbidity.

CONCLUSION

Maternal hyperparathyroidism represents a preventable cause of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. We report three cases of maternal hyperparathyroidism in which favourable maternal and neonatal outcomes were achieved after parathyroidectomy during pregnancy. Medical treatment is unsatisfactory in pregnancy. Surgical treatment can normalize maternal hypercalcaemia thereby reducing fetal risk, while also facilitating treatment of maternal hypovitaminosis D. Given the risks of maternal hypercalcaemia and fetal parathyroid suppression, surgery should be considered at all stages of pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- 1. Carella MJ, Gossain VV. Hyperparathyroidism and pregnancy. Case report & review. J Gen Inter Med 1992;7:448–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Potts JT. Diseases of the parathyroid gland and other hyper- and hypocalcemic disorders. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001:2205–14 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Friedrichsen C. Hypocalcamie bei einem Brustkingund Hypercalcamie bei der Mutter. Monatsshr F Kinderheilkunde 1938;75:146 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kohlmeier L, Marcus R. Calcium disorders of pregnancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 1995;24:15–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cushard WG, Creditor MA, Canterbury JM, Reiss E. Physiologic hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1972;34:767–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kondo Y, Nagai H, Kasahara K, Kanazawa K. Primary hyperparathyroidism and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy. Report of a case and a review of the English and Japanese literature. Int J Pancreatol 1998;24:43–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fleischman AR. Fetal parathyroid gland and calcium homeostasis. Clin Obstet Gynaeocol 1980;23:791–802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kovacs CS, Lanske B, Hunzelman JL, Guo J, Karaplis AC, Kronenberg HM. Parathyroid-hormone related peptide regulates fetal-placental calcium transport through a receptor distinct from the PTH/PTHrP receptor. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 1996;93:15233–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaplan EL, Burrington JD, Klementshitsch P, Taylor J, Deftos L. Primary hyperparathyroidism, pregnancy, and neonatal hypocalcaemia. Surgery 1984;96:717–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. De Swiet M. Medical Disorders in Obstetric Practice. 4th edn Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 2002. Chapter 14 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnstone RE II, Kreindler T, Johnstone RE. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1972;40:580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kovacs CS, Kronenburg HM. Maternal-fetal calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy, puerperium and lactation. Endocrinol Rev 1997;18:832–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ludwig GD. Hyperparathyroidism in relation to pregnancy. New Engl J Med 1962;267:637–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delmonico FL, Neer RM, Cosimi AB, Barnes AB, Russell PS. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Am J Surg 1976;131:328–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shangold MM, Dor N, Welt SI, Fleischman AR, Crenshaw C. Hyperparathyroidism and pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynaeocol Surv 1982;37:217–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graham EM, Freedman LJ, Forouzan I. Intrauterine growth retardation in a woman with primary hyperparathyroidism. A case report. J Reprod Med 1998;43:451–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelly TR. Primary hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy. Surgery 1991;110:1028–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beattie GC, Ravi NR, Lewis M, et al. Rare presentation of maternal primary hyperparathyroidism. Br Med J 2000;321:223–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tseng UF, Shu SG, Chen CH, Chi CS. Transient neonatal hypoparathyroidism: report of four cases. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 2001;42:359–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ip P. Neonatal convulsion revealing maternal hyperparathyroidism: an unusual case of late neonatal hypoparathyroidism. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003;268:227–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bruce J, Strong JA. Maternal hyperparathyroidism and parathyroid deficiency in the child. Q J Med 1955;96:307–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kort KC, Schiller HJ, Numann PJ. Hyperparathyroidism and pregnancy. Am J Surg 1999;177:66–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schnatz PF, Curry SL. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy: evidence-based management. Obstet Gynaeocol Surv 2002;57:365–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schnatz PF, Thaxton S. Parathyroidectomy in the third trimester of pregnancy. Obstet Gynaeocol Surv 2005;60:672–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haenel LC, Mayfield RK. Primary hyperparathyroidism in a twin pregnancy and review of fetal/maternal calcium homeostasis. Am J Med Sci 2000; 319:191–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lowe DK, Orwoll ES, McClung MR, Cawthon ML, Peterson CG. Hyperparathyroidism and pregnancy. Am J Surg 1983;145:611–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Better OS, Levi J, Greif E, Tuma S, Gellei B, Erlik D. Prolonged neonatal parathyroid suppression. Arch Surg 1978;106:722–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Higgins RV, Hisley JC. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med 1988;33:726–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clark D, Seeds JW, Cefalo RC. Hyperparathyroid crisis and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynaecol 1981;140:840–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patlas N, Golomb G, Yaffe P, et al. Transplacental effects of bisphosphonates on fetal skeletal ossification and mineralization in rats. Teratology 1999;60: 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Djokanovic N, Klieger-Grossmann C, Koren G. Does treatment with bisphosphonates endanger the human pregnancy? J Obstet Gynaecol Canada 2008;30:1146–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murray JA, Newman WA, Darcus JV. Hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy: diagnostic dilemma? Obstet Gynaeocol Surv 1997;52:202–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. United States Food and Drugs Administration. See http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/dailys/00/mar00/032300/cp0001.pdf (last checked 28 January 2010)

- 34. British National Formulary. British Medical Association and The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Issue no 58 (September 2009). Appendix A: Pregnancy

- 35. Montoro MN, Collea JV, Mestman JH. Management of hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy with oral phosphate therapy. Obstet Gynaecol 1980;55:431–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Norman J, Politz D, Politz P. Hyperparathyroidism during pregnancy and the effect of rising calcium on pregnancy loss: a call for earlier intervention. Clin Endocrinol 2009;71:104–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pothiwala P, Levine SN. Parathyroid surgery in pregnancy: review of the literature and localisation by aspiration for parathyroid hormone levels. J Perinatol 2009;29:779–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGill J, Sturgeon C, Kaplan SP, Chiu B, Kaplan EL, Angelos P. How does the operative strategy for primary hyperparathyroidism impact the findings and cure rate? A comparison of 800 parathyroidectomies. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:246–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rabasa-Lhoret R, Rasamisoa M, Caubel C, Avignon A, Monnier L. Hyperparathyroidism diagnosed during pregnancy. Presse Med 2001;30:964–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Truong MT, Lalakea L, Robbins P, Friduss M. Primary hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy: a case series and review. Laryngoscope 2008;118:1966–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]