Abstract

Immunotherapies have shown considerable efficacy for the treatment of various cancers but a multitude of patients remain unresponsive for various reasons including poor homing of T cells into tumors. In this study, we investigated the roles of leukotriene B4 receptor - BLT1; and CXCR3, the receptor for CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 under endogenous as well as vaccine induced anti-tumor immune response in a syngeneic murine model of B16 melanoma. Significant acceleration in tumor growth and reduced survival was observed in both BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice as compared to the WT mice. Analysis of tumor infiltrating leukocytes revealed significant reduction of CD8+ T-cells in the tumors of BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice as compared to WT tumors, despite their similar frequencies in periphery. Adoptive transfer of WT but not BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− CTLs significantly reduced tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice, a function attributed to reduced infiltration of knockout (KO) CTLs into tumors. Co-transfer experiments suggested that WT CTLs do not facilitate the infiltration of KO CTLs to tumors. Anti-PD-1 treatment reduced the tumor growth rate in WT mice but not in BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− or BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice. The loss of efficacy correlated with failure of the knockout CTLs to infiltrate into tumors upon anti-PD1 treatment, suggesting an obligate requirement for both BLT1 and CXCR3 in mediating anti-PD-1 based anti-tumor immune response. These results demonstrate a critical role for both BLT1 and CXCR3 in CTL migration to tumors and thus may be targeted to enhance efficacy of CTL based immunotherapies.

Keywords: CXCR3, BLT1, cancer, anti-tumor immunity, leukocyte migration

Introduction

Several preclinical and clinical studies suggest a positive prognostic implication and prolonged survival advantage associated with the presence of tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells (1–6). Adoptive cell therapies including Chimeric Antigen Receptor therapy (CAR) have shown considerable efficacy in melanoma and haematological malignancies like leukemia with an impressive 80% response rates in some studies (7, 8). A major criteria pertinent to the success of these immunotherapies is the presence of CTLs in tumors. However, one of the obstacles in the success of existing CD8+ T cell based tumor immunotherapies, particularly in solid tumors, is inefficient homing of the CD8+ T cells into tumors. Some preclinical studies have shown that less than two percent of the transferred CTLs infiltrate the tumors (9–11). Vaccination studies have demonstrated inefficient tumor regression despite intact CTL responses in the periphery; a phenotype attributed to lack of efficient CTL trafficking into tumors (9, 12, 13). Tumor suppressive microenvironment and the nature of the tumor microvasculature are some of the resistance mechanisms employed by the tumor against recruitment of CD8+ T cells (11, 14–16).

Chemokine-chemokine receptor pathways are one of the major factors governing CTL recruitment to tumors and anti-tumor immunity (12, 17). Till date only a few chemokine receptors viz. CCR5, CXCR3, CX3CR1 and CXCR6 and their cognate ligands have been implicated in CTL migration to tumors (18–23). CXCR3 is expressed on activated CD4+, CD8+ T cells and NK cells and is strongly associated with Th1 and cytotoxic responses (24–28). The role of CXCR3 and its interferon gamma inducible ligands - CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11 have been very well characterized in various viral disorders, autoimmunity and transplantation studies (12). However, its role in regulating T cell migration across the tumor vasculature has been recently demonstrated as a critical mediator of T cell based immunotherapies (29). CXCR3 and its ligands play a crucial role in anti-tumor immunity by having anti-tumor effects on tumor cells directly or indirectly through the host immune system (29–38). Another category of potent chemoattractants include leukotriene B4 (LTB4), an eicosanoid derived from arachidonic acid (39). BLT1, the high affinity receptor for LTB4 is expressed on innate cells as well as activated T cells and has been implicated as a pro-inflammatory mediator (40–45). In the context of cancer, BLT1 was shown to play a dual role in controlling tumor promoting inflammation; as seen in silica induced lung tumorigenesis (46), or tumor suppressive inflammation; as shown in the TC-1 cervical cancer model (47).

Herein, we studied the roles of BLT1 and CXCR3 in mediating an endogenous as well as anti-PD-1 based anti-tumor immune responses using a syngeneic murine model of B16 melanoma. Both BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice showed significantly enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival compared to WT mice in melanoma and breast cancer models. Analysis of tumor infiltrating leukocytes and adoptive transfer experiments in Rag2−/− mice revealed the importance of BLT1 and CXCR3 expression on CD8+ T cells for generating effective anti-tumor immunity. An Anti-PD-1 Ab immunotherapy significantly reduced the tumor growth in WT mice but was completely ineffective in both BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice. The inability of the vaccine to enhance T cell migration in the knockout mice suggested an obligate non-redundant requirement for both BLT1 and CXCR3 in T cell migration to tumors and Anti-PD-1 Ab induced anti-tumor immunity.

Materials and Methods

Mice and cell lines

C57BL/6 mice, CXCR3−/− mice and UBC-GFP mice in C57BL/6 background (6–7wks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and/or bred in our animal facility at the University of Louisville. Previously described BLT1−/− mice in C57BL/6 background were also bred in our animal facility at University of Louisville (48). Rag2−/− mice in C57BL/6 background were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− double knockout mice were generated by crossing BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice at our animal facility. All animals were cared for in accordance with institutional and National Institute of Health guidelines and under IACUC protocol. B16 melanoma cell line and E0771 breast cancer cell line were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in complete RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS.

Reagents

Fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (anti-CD45.2-PE-Cy7, anti-CD3-APC-Cy7, anti-CD4-APC, anti-CD8-PerCP-Cy5.5, NK1.1-PE, CD11b-APC, Ly6G-PE, Ly6C-FITC, IFNγ APC, TNFα APC-Cy7, anti-CXCR3-PE, Streptavidin-APC and 7-AAD) were purchased from BD PharMingen and eBioscience. AnnexinV FITC was purchased from Biolegend. Trp-2 peptide (Trp2180: SVYDFFVWL) was purchased from Peptide 2.O Inc. Anti-m-OX-40 agonistic Ab (Clone OX-86) and Anti-m-PD-1 antagonistic Ab (Clone: RMP1-14) were purchased from BioXcell. Anti-mouse BLT1 antibody conjugated to biotin was developed in the lab (unpublished data).

Tumor model and vaccinations

WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice were challenged with 105 live B16 melanoma cells or in certain experiments 105 E0771 cells by reconstituting in 200µl PBS and injecting subcutaneously at the right flank of naive mice to form tumors. For low tumor dose experiments, 4x104 live B16 cells were injected s.c. Tumor diameter was measured every alternate day using a calliper. Average tumor diameter was calculated by measuring two perpendicular diameters and tumor area was calculated by multiplying the two perpendicular diameters. For survival experiments, mice were allowed to reach 15mm tumor diameter and once they do were considered as dead. Percentage survival was calculated and plotted using Kaplan Meier survival plots. Tumor bearing animals were euthanized once the tumors reached 15mm or 7–9mm diameter or earlier if they showed any signs of discomfort. For vaccine studies, WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− were challenged with 105 live B16 cells s.c. on the right flank on day 0. On day +5 and day +15 post tumor challenge, the mice were vaccinated i.v. with 50µg/mice Trp-2 peptide and 100µg/mice anti-PD-1 antagonistic Ab (clone RMP1-14, BioXcell). The control mice were administered with PBS. The tumor growth was monitored every alternate day. The mice were euthanized when the knockout animals or the control unvaccinated animals reached 15mm tumor diameter. Tumors, blood, spleen and tumor draining lymph nodes (TdLN) were then analyzed for CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry

Tumors were harvested and cut into small pieces after removal of connective tissue and tissue stroma. To obtain single cell tumor suspension, the small tumor pieces were incubated in an enzyme mixture consisting of Collagenase A (2mg/ml) and DNase-I (1mg/ml) in incomplete RPMI medium for 1hr at 37 °C on a rocking platform. After 1hr digestion, single cell suspension was obtained by passing the digested tissue through 40µm nylon mesh and the resultant cells washed twice in PBS before staining for flow cytometry. Cells were stained with fluorochrome labelled anti-mouse Ab like CD45.2, CD3, CD4, CD8, NK1.1, CD11b, Ly6G, Ly6C, etc. Two million total tumor cells were stained and analyzed using multi-parameter flow cytometry. Similarly, spleen and tumor draining lymph nodes (TdLN- inguinal, brachial and axillary) were harvested, processed into single suspension, stained and analyzed via flow cytometry. For intracellular cytokine staining single cell suspensions from tumor, spleen and TdLNs were stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail (eBiosciences, 500X used at 1X) consisting of PMA (40.5µM), Ionomycin (670µM) and protein transport inhibitors – Brefeldin A (5.3mM) and Monensin (1mM) for 6hrs at 37 °C, 5%CO2. After 6 hrs the cells were harvested and washed, surface stained with CD45, CD3 and CD8 and fixed and permeabilized (IC fixation and Permeabilisation buffer – eBiosciences ) and stained for IFNγ and TNFα using anti-mIFNγ Ab and anti-mTNFα Ab (BD Biosciences). Isotype controls with the same fluorochrome were used as controls. Cells were acquired using FACS Canto II machine and analysed by FlowJo (TreeStar) software.

In order to analyse the percentages of CTLs undergoing apoptosis, single cell suspensions from tumors were stained with CD45, CD3 and CD8 antibodies. Apoptosis was evaluated using standard 7AAD and AnnexinV FITC staining protocols and analyzed by flow cytometry. % of 7AAD+AnnexiV+ cells of total CD8+ T cells were determined in tumor cell suspensions obtained from tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice once tumors reached 5mm in diameter.

For BLT1 and CXCR3 staining, single cell suspensions from TdLN were obtained from tumor bearing vaccinated or unvaccinated WT mice. The mice were sacrificed and TdLN were harvested after 3 days post second vaccine dose administration according to the vaccine design. Single cell suspensions were stained with 2µl of biotinylated anti-mouse BLT1 antibody developed in the laboratory and incubated at 4 °C for one hr. The cells were washed with IX PBS + 0.1% BSA and further stained with 1µl of Streptavidin-APC and other antibodies against CD45, CD3, CD8 and CXCR3 for 1 hour at 4 °C. Suitable isotype controls with the same fluorochrome were used. Cells were then washed and acquired using the FACS Canto II machine and analyzed by FlowJo (TreeStar) software.

Immune-fluorescence microscopy

Immune-fluorescence staining for CD8+ T cells in the tumors of WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice was analyzed using Nikon-A1R Confocal microscope. Tumors were embedded in OCT medium and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and later cut into 5µm sections using a cryostat. Sections were fixed using ice-cold acetone and then blocked using 1X PBS supplemented with 3% BSA and 5% goat serum for 1 hr at RT. To stain for CD8+ T cells, the sections were incubated with rat anti-mouse CD8a Ab (BD Pharmingen) in 1X PBS + 3% BSA for 1hr at RT. After 3 washes with PBS, the sections were then incubated with the secondary Ab goat anti-rat Alexa 594 (2mg/ml, Invitrogen). After washing with PBS, the sections were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Labs) and analyzed at 200X magnification. A minimum of 4 fields for each tumor section was analyzed.

In vivo-cytotoxicity assay

A standard in vivo-cytotoxicity assay was performed by injecting peptide pulsed target cells into immunized mice as previously described (47). Briefly, WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− recipient mice were immunized s.c. with 50µg/mice of Trp-2 peptide and an adjuvant i.e. 100µg/mice anti-OX-40 agonistic Ab (Clone OX-86, BioXcell). 7 days later, C57BL/6 splenocytes were divided into CFSEhigh and CFSElow populations by staining with 2.5µM and 0.25µM CFSE fluorescent dye. CFSEhigh cells were pulsed with 2µg/ml Trp-2 peptide. CFSE high and low cells were extensively washed and mixed at 1:1 ratio and injected i.v. into the immunized WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− mice. Their spleens were harvested after two days and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the ratio of CFSEhigh/CFSElow target cells and percent killing. The percentage of in vivo killing was calculated by the following formula:

Adoptive transfer studies in Rag2−/− mice

Rag2−/− immune-deficient mice were challenged s.c. with 1 x 105 live B16 cells. Two days later, CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and TdLN of tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− or BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice by magnetic sorting using CD8a-Ly2 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) with >98% purity. 1 million purified CD8+ T cells were injected i.v. into the Rag2−/− mice challenged with live B16 tumors and vehicle alone i.e. PBS was used as the control. Tumor growth was monitored every alternate day. Animals were euthanized once they reached 15mm tumor diameter and TdLNs as well as tumors were analyzed for CD8+ T cell numbers. For, co-transfer experiments, UBC-GFP mice were used as WT mice in order to distinguish between WT and knockout (non-GFP) CD8+ T cells. Rag2−/− mice were challenged with 105 live B16 cells. Two days later, CD8+ T cells were isolated from tumor bearing WT (UBC-GFP), BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice. 1 million total CD8+ T cells consisting of WT (GFP+) and either BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− or BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells were injected into Rag2−/− mice in equal proportion and tumor growth was monitored. Animals were euthanized once they reached 7–9mm diameter. Spleen, blood, TdLN and tumors were harvested and CD8+ T cells were analysed for GFP+ (WT) and GFP- (knockout) populations.

T-cell activation ex-vivo

WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were immunized with Trp2 peptide and OX-86 adjuvant s.c. to obtain antigen specific responses. 7 days later mice were sacrificed and spleen and draining lymph nodes were harvested. Pooled cells were activated for 5 days in U-bottom 96 well plates coated with anti-mouse CD3e Ab (2µg/ml, clone 145-2C11, BD Biosciences) and anti-mouse CD28 (2µg/ml, Clone 37.51, eBiosciences) in complete media for 48 hrs and maintained in rhIL-2 (20ng/ml, Peprotech) for 5 days. The cells were then used for chemotaxis assays or for BLT1 and CXCR3 staining using flow cytometry.

Chemotaxis assays

Chemotaxis was performed for murine WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− CTLs in response to media alone, 10nM LTB4, 10nM CXCL10 and both 10nM LTB4 and CXCL10 (Peprotech). The assay was performed in 24 well plates with 5µm pore size transwell insert (Corning). Media (RPM1+1%FBS) containing chemokines or media alone were placed in the bottom chamber. 0.5 million activated CD8+ T cells were placed in the upper chamber. After 3hr of incubation at 37°C, the cells that migrated to the lower chamber were counted using hemocytometer.

CXCL9, CXCL10 and LTB4 measurements

Tumors from WT unvaccinated and vaccinated mice were harvested after 3 days post second vaccine dose was administered. The tumors were homogenized in 500µl 1X PBS buffer containing 10µM Indomethacin using Omni GLH general homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14000 g for 15mins and supernatants were collected. LTB4 was measured using the EIA Kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CXCL9 (MIG) and CXCL10 (IP-10) were measured using the Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to manufacturer’s instructions. CXCL9, CXCL10 and LTB4 were expressed as pg/g of tumor tissue.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from the excised tumors was isolated using Trizol followed by RNase mini-prep kit from Qiagen. The RNA was treated with DNase using Turbo DNAse kit (Ambion). For quantitative real-time PCR, 1µg total RNA was reverse transcribed in 50µl reaction using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) using random hexamer primers. A total of 2µl cDNA and the 1µM real-time PCR primers were used in a final 20µl PCR reaction with “power SYBR-green master mix” (Applied Biosystems). The real-time primers for Granzyme-b and GAPDH were purchased from Real Time Primers, LLC (Elkins Park, PA). The sequence of the primers will be provided upon request. Real-time PCR reaction was performed in Bio-Rad CFX-96 Real Time System. Expression of the target genes was normalized to GAPDH and displayed as fold change relative to the WT sample. Data are representative of tumors isolated from at least five different mice for each genotype.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using the Student t test and Mann Whitney U test. The survival assays were analyzed using long-rank test in Graph Pad Prism software. Student’s t-test were used for comparisons between two experimental groups, with a p value of <0.05 considered as significant using Graph Pad Prism software (***=p<0.001; **=p<0.01, *=p<0.05). Error bars represent ±SEM.

Results

Defective immune surveillance and anti-tumor immunity in BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice

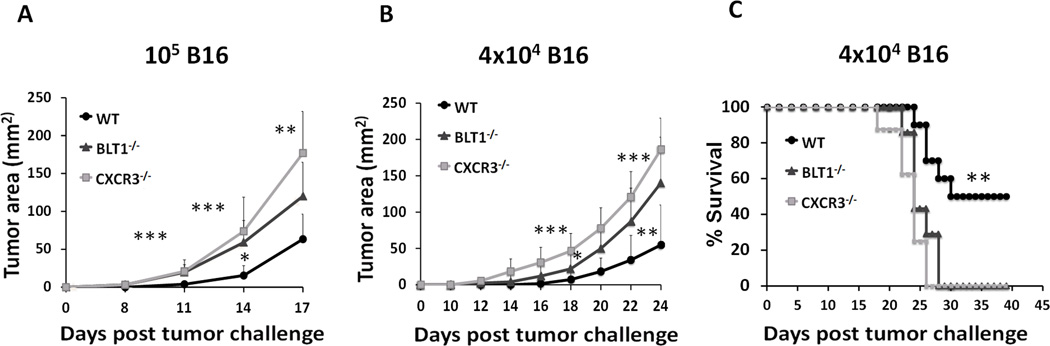

An essential role for BLT1 in immune surveillance against tumors and anti-tumor immunity in a viral antigen derived TC-1 cervical cancer model was recently demonstrated (47). To determine the requirement for BLT1 and CXCR3 in mediating anti-tumor immunity in an autologous (non-viral) tumor model, syngeneic spontaneous B16 melanoma mice model was employed. WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were subcutaneously challenged with either a lethal tumor dose (105 cells) or sub-lethal tumor dose (4 x 104 cells) of B16 cells. BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice showed significantly enhanced tumor growth as compared to the WT mice at both doses of tumor challenge (Figure 1A and B) and significantly reduced survival as compared to the WT mice at the low dose (Figure 1C). Even at the sub-lethal tumor dose both BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice demonstrated 100% mortality by day 28 post tumor challenge, however, 50% of the WT mice still survived post day 40 with all of them developing relatively slow growing tumors (Figure 1 C). To explore whether similar phenotypes are seen in other solid tumor types, WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were challenged with 105 E0771 cells. Like in melanoma, in this breast cancer model the BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice demonstrated significantly enhanced tumor growth compared to WT mice (Figure S1). These results suggest that both BLT1 and CXCR3 may be crucial for immune surveillance and generating endogenous anti-tumor response.

Figure 1. Enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival in BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice.

A, WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were challenged subcutaneously with 105 B16 cells (high dose). Tumor area was determined by multiplication of two perpendicular diameters (LxW). n=9 for each group. B, WT (n=10), BLT1−/− (n=7) and CXCR3−/− (n=8) mice were challenged subcutaneously with 4x104 B16 cells (low dose) and the tumor area calculated. C, Survival in low dose challenge group was monitored till day 45 post tumor challenge. Log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier methods were used for survival analyses and student t tests were used for tumor sizes. A, Data is representative of three independent experiments. B, C, Data representative of two independent experiments.

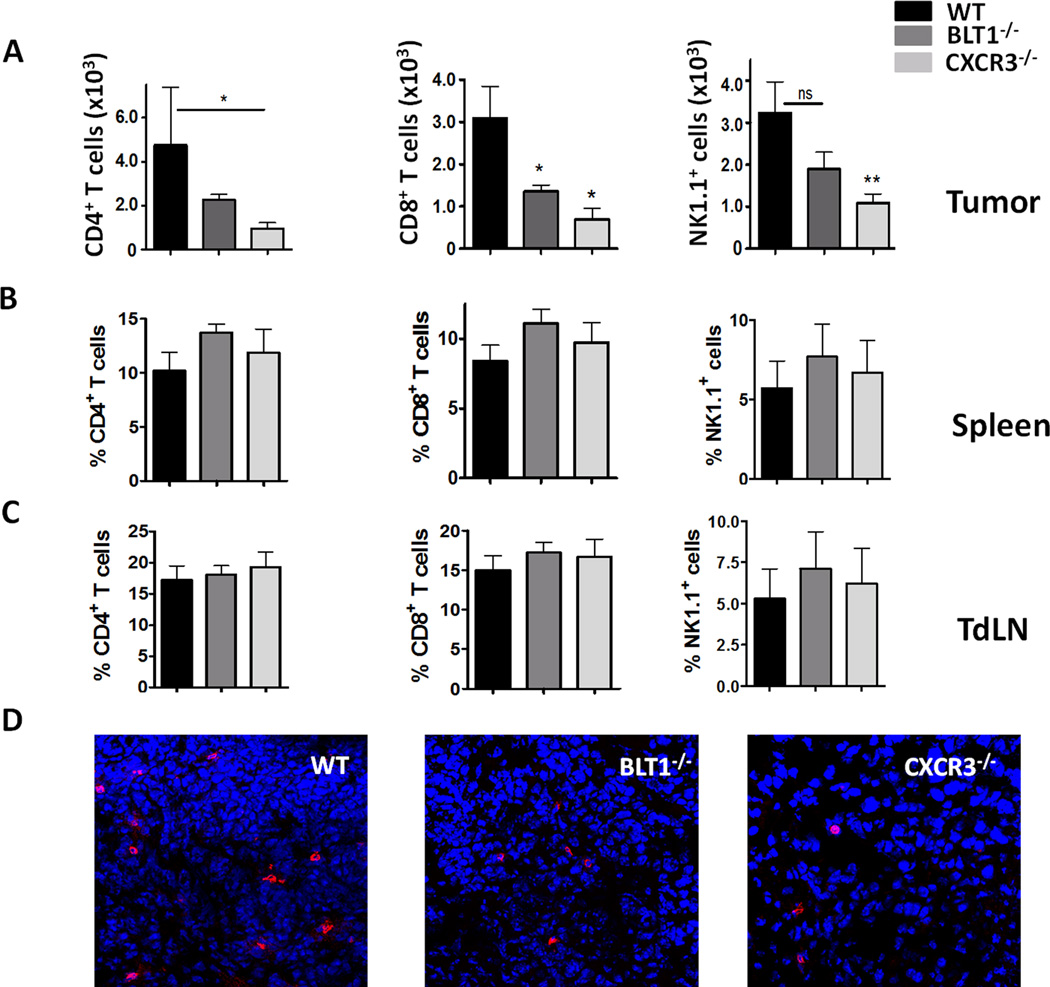

Reduced homing of CD8+ T cells into tumors of BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice

To explore the basis for enhanced tumor growth in the knockout mice, leukocyte sub-populations in tumors, spleen and TdLN of tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were analyzed by flow cytometry. WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were challenged with 1 x 105 B16 cells and the tumors were harvested when the knockout tumors reach 7–9 mm (mid-sized) tumor diameter. Single cell suspensions were obtained from the tumor, spleen and TdLN and stained with CD45.2 for all immune cell populations and CD3, CD4 and CD8 for T cells, NK1.1 for NK cells, CD11b, Ly6G and Ly6C for myeloid cell populations. The BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− tumors showed significant reduction in CD8+ T cell numbers as compared to WT tumors (Figure 2A). Moreover, CXCR3−/− tumors, but not BLT1−/− tumors, had significant reduction in other effector cell populations like CD4+ T cell and NK cells as compared to the WT tumors (Figure 2A). To ensure that reduced CTL numbers are not a function of differential tumor sizes, TIL infiltration, studies were carried out in size-matched tumors. Similar reduction in CD8+ T cell numbers in tumors of knockout mice as compared to WT mice was observed in size matched (at the end stage) tumors as well (Figure S2A). Immune cell profiling in the spleen and TdLN revealed that knockout mice had similar percentages of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells and NK cells as compared to WT mice (Figure 2B and C). Myeloid cell populations constitute a significant part of the tumor microenvironment. Analysis of CD11b+ myeloid cells and myeloid derived suppressive cells subsets (MDSC) i.e. CD11b+Ly6G+ (granulocytic-MDSC) and CD11b+Ly6C+ (monocytic-MDSC) in the tumors of WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice showed no significant difference (Figure S2B). The significant reduction in CD8+ T cells in the tumors of BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice was confirmed by immune-fluorescence staining and confocal microscopy (Figure 2D). These results suggest that enhanced tumor growth in BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice may be related to the reduced numbers of CD8+ T cells as compared to tumors of WT mice.

Figure 2. Reduced infiltration of CD8+ T cells in BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− tumors.

A, Numbers of tumor infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK1.1+ cells per million total tumor cells (frequency of total) were analyzed from WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice using standard flow cytometry protocol as described in Methods. All the mice were sacrificed and tumors harvested when the knockout tumors reached 7-9mm tumor diameter. B, CD4+, CD8+, NK1.1+ staining in TdLN of size-matched tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice. Data represented as percent of total CD45+ cells. C, CD4+, CD8+, NK1.1+ staining in spleens of size-matched tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice. Data represented as percent of total CD45+ cells. D, Representative immunofluorescence staining images of CD8+ T cells in WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− tumors. Tumors harvested were frozen, sectioned and stained as described in Methods, CD8 represented in Red, DAPI in blue. The images were captured using Nikon A1R confocal microscope. The scale represents 50µM. Data representative of three independent experiments.

To determine if the significant reduction in CD8+ T cell numbers in the tumors of BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice was not due to differential survival rates; we performed staining of apoptosis markers 7AAD and AnnexinV. %7AAD+AnnexinV+ cells of total CD8+ T cells in tumors from WT and knockout mice were determined. There was no significant difference between WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells undergoing apoptosis in the tumor microenvironment (Figure S3A). Thus, lack of BLT1 and CXCR3 does not affect the survival of CTLs in the tumor milieu, however their migration into the tumors from periphery is significantly abrogated.

Given that BLT1 and CXCR3 are essential for homing into tumors, we sought to determine if the effector functions were also controlled by BLT1 and CXCR3. Transcript expression levels of CTL effector molecule viz. granzyme-b in tumors was significantly reduced in tumors of BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice as compared to WT mice as shown by RT-PCR (Figure S3B). No significant difference was observed in the killing abilities of the CD8+ T cells in the spleens of WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice (Figure S3C). To measure their cytotoxic function within the tumor, levels of IFNγ, an effector cytokine was determined in the CD8+ T cells by intracellular cytokine staining. The percent IFNγ+ cells of total CD8+ T cells in the tumors of CXCR3−/− mice was significantly reduced as compared to WT mice; but remained similar in the tumors of BLT1−/− mice (Figure S3D). In contrast, percent IFNγ+ cells of total CD8+ T cells in spleens and TdLNs of tumor bearing WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice were similar (Figure S3D). Interestingly, CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells showed intact TNFα production in the tumor as also in spleen and TdLN (Figure S3D). These studies suggest that BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− CTLs do not have an intrinsic defect in effector functions. However, CXCR3−/− CTLs may have defective effector function in the tumor microenvironment, specifically in the IFNγ axis.

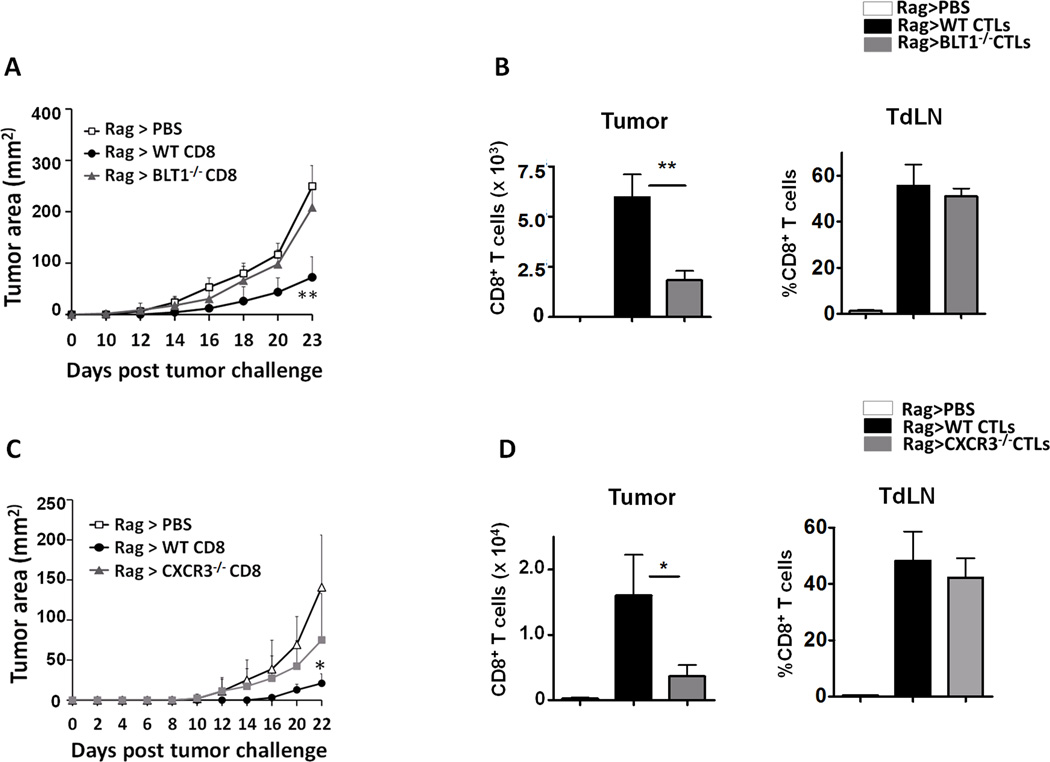

Adoptively transferred WT but not BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells delayed tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice

To further examine the importance of BLT1 and CXCR3 expression on CD8+ T cells for effective infiltration to tumors, adoptive transfer model involving Rag2−/− mice was employed. Rag2−/− mice were challenged with 105 B16 cells and 2 days later were adoptively transferred with tumor educated sorted (>98% pure) WT or BLT1−/− CD8+ T cells and the tumor growth was recorded. PBS transferred tumor bearing Rag2−/− mice served as controls. WT CD8+ T cells significantly reduced the tumor progression in Rag2−/− animals. However, BLT1−/− CD8+ T cells failed to reduce the tumor growth and showed tumor growth kinetics similar to control Rag2−/− mice without any transferred CD8+ T cells (Figure 3A). CTL infiltration studies showed that BLT1−/− CTLs were significantly reduced in tumors of Rag2−/− mice as compared to WT CTLs, albeit remaining similar in the TdLN (Figure 3B), suggesting a defect in tumor infiltration of BLT1−/− CTLs. Similar studies were carried out with WT and CXCR3−/− CTLs. CXCR3−/− CTLs also failed to retard tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice. This defective anti-tumor response was attributed to significantly reduced levels of CXCR3−/− CTLs in the tumors, their levels remaining similar in the TdLN (Figure 3C and 3D). These studies demonstrate that expression of both BLT1 and CXCR3 on CTLs is necessary for their effective infiltration to tumors and subsequent anti-tumor immunity.

Figure 3. Adoptive transfer of WT but not BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− tumor experienced CD8+ T cells retarded tumor growth in Rag2−/− mice.

Rag2−/− mice were challenged with 105 B16 cells. Two days later CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and TdLN of B16 tumor bearing (3-5mm) WT, BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− mice by MACS technique and 1 million isolated CD8+ T cells (>98% purity) or PBS were injected i.v. in tumor inoculated Rag2−/− mice. A, Tumor growth kinetics for Rag2−/− mice transferred with either PBS (n=5), WT CD8+ T cells (n=5) or BLT1−/− CD8+ T cells (n=5). B, Numbers of CD8+ T cells (frequency of total) per 1 million total tumor cells and percent CD8+ T cells of total CD45+ cells in TdLN for WT and BLT1−/− transferred CD8+ T cells are shown. C, Tumor growth kinetics for Rag2−/− mice transferred with either PBS (n=4), WT CD8+ T cells (n=5) or CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells (n=4). D, Numbers of CD8+ T cells (frequency of total) per 1 million total tumor cells and percent CD8+ T cells of total CD45+ cells in TdLN for WT and CXCR3−/− transferred CD8+ T cells are shown. Data is representative of two independent experiments.

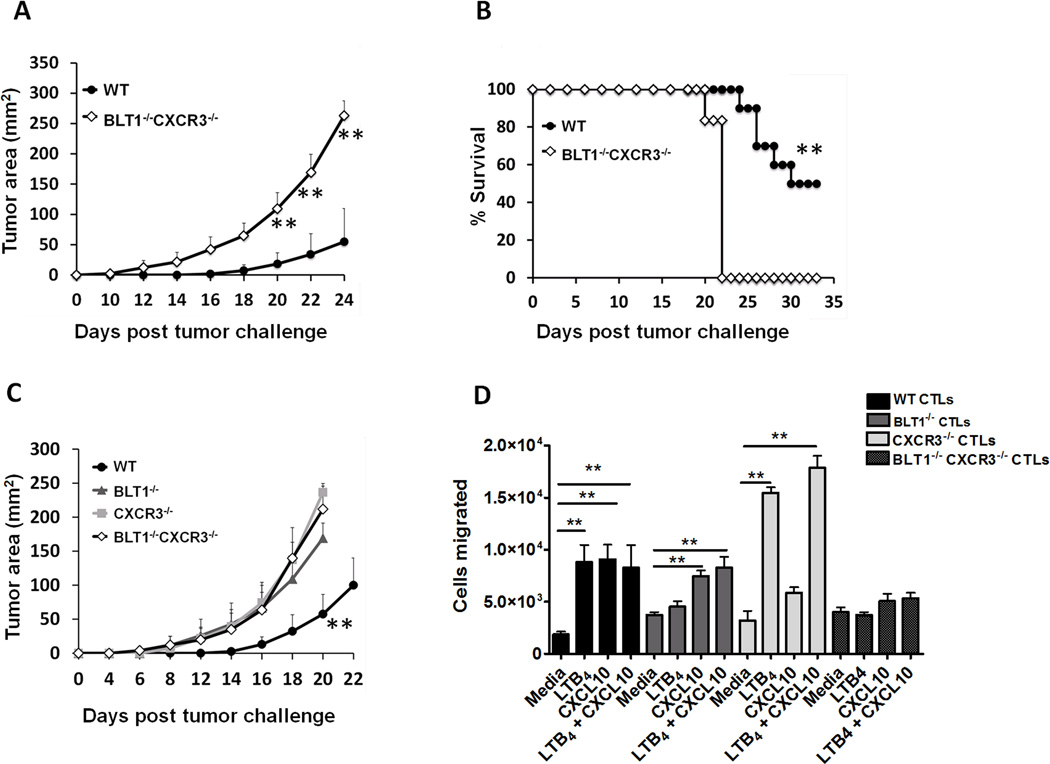

Accelerated tumor growth and reduced survival in BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice

To examine the interdependence of BLT1 and CXCR3 in generating anti-tumor immunity, BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− double knockout mice (DKO) were generated by crossing BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice. The BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratios and displayed normal developmental and morphological features. At the sub-lethal dose of B16 cells (4x104), BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice showed significantly enhanced tumor growth as well as significantly reduced survival as compared to WT mice (Figure 4A and B). There was 100% mortality of BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice by day 22, while 50% of WT mice still survived at day 35-post tumor challenge (Figure 4B). To compare the tumor growth kinetics in double knockout mice versus either of the single knockout mice; WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice were challenged with 105 B16 cells and the tumor growth was recorded. The BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− mice displayed significantly enhanced tumor growth kinetics as compared to WT mice but similar growth kinetics as compared to BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− mice (Figure 4C). No significant enhancement in the tumor growth was observed in the double knockout mice as compared to either of the single knockout mice. These results suggest that BLT1 and CXCR3 mediated regulation of anti-tumor immunity may be codependent but not additive or synergistic.

Figure 4. Defective immune surveillance and anti-tumor immunity in BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− double knockout (DKO) mice.

A, WT (n=10) and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− (n=6) mice were challenged subcutaneously with 4x104 B16 cells (low dose) and the tumor area calculated. Tumor area was measured by multiplication of two perpendicular diameters (LxW). B, Survival in low dose challenge group was monitored till day 35 post tumor challenge. C, WT (n=4), BLT1−/− (n=5), CXCR3−/− (n=4) and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− (n=6) mice were challenged subcutaneously with 105 B16 cells (high dose). Log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier methods were used for survival analyses and student t tests were used for tumor sizes. Data is representative of two independent experiments. D, No further enhancement in CTL migration was observed in response to both LTB4 and CXCL10. Chemotaxis with activated CTLs was performed as indicated in the methods section. The migration of CTLs was determined in response to LTB4 (10nM), CXCL10 (10nM) or LTB4 and CXCL10 (10nM each) in combination. Migration in response to media alone (RPMI + 1% FBS) served as control. 0.5 million WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and DKO CTLs were loaded onto the upper chamber and appropriate ligands were placed in the lower chamber and the measurements were carried out in triplicates. The data represents cells migrated in response to respective ligands. Data is representative of two independent experiments.

To determine if there is dependence of BLT1 receptor on CXCR3 and vice versa in order to achieve efficient CTL migration, we performed ex-vivo chemotaxis assays. Activated WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells were prepared and chemotaxis performed as described in the methods section. The results showed that BLT1−/− CTLs migrate to CXCL10 and CXCR3−/− CTLs migrate to LTB4 to a similar extent as compared to WT CTLs. This suggests that CXCR3 is functional in BLT1 deficient CTLs and BLT1 is functional in CXCR3 deficient CTLs. The results also suggest that LTB4 and CXCL10 collectively do not further enhance the CTL chemotaxis (Figure 4D). This is in line with the results obtained with double knockout mice wherein there was no further enhancement of tumor growth in the absence of both BLT1 and CXCR3 compared to either alone. In order to determine whether BLT1 and CXCR3 receptors are expressed on the same cells, we performed BLT1 and CXCR3 staining on ex vivo activated CTLs. Receptor expression studies indicated that almost all in vitro activated CTLs (92.3%) are CXCR3+, out of which around 31% are BLT1+. (Figure S4).

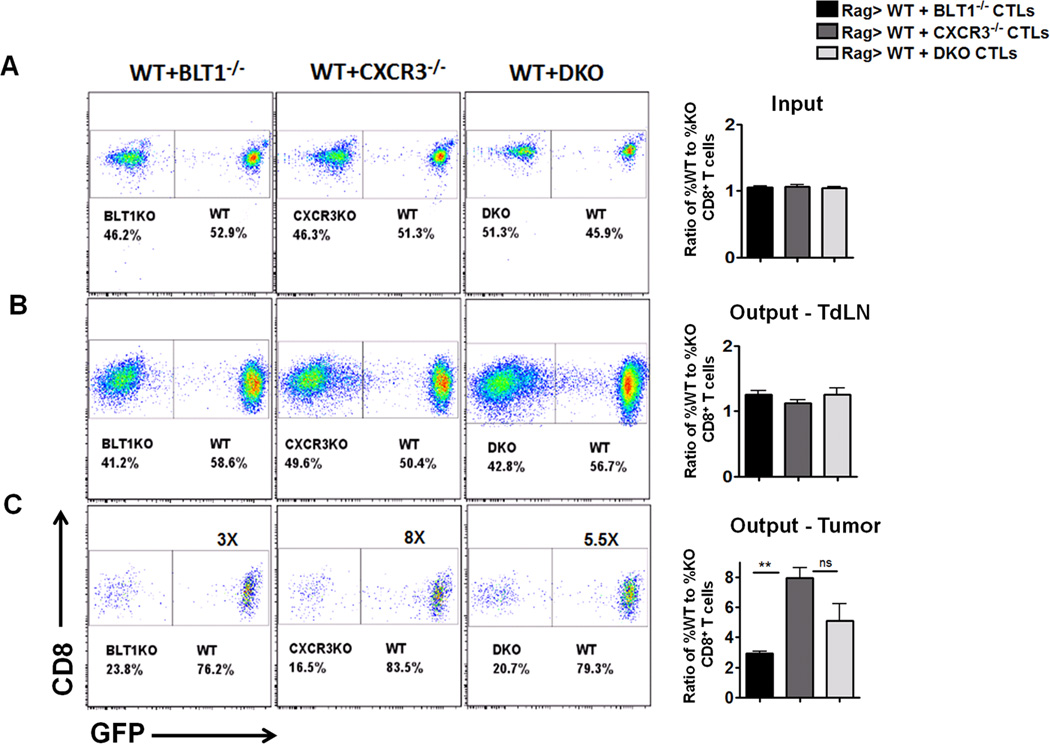

WT CTLs do not facilitate knockout CTL infiltration to tumors

In order to determine if WT CTLs could facilitate knockout CTL infiltration to tumors by production of cytokines/chemokines, the migration patterns of the WT and knockout CD8+ T cells co-transferred into Rag2−/− mice were studied. Equal proportions of tumor experienced WT CD8+ T cells and BLT1−/− , CXCR3−/− or BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− (DKO) CD8+ T cells were introduced intravenously into tumor bearing Rag2−/− mice. UBC-GFP mice were used as WT mice to differentiate between WT (bright green fluorescence) and the knockout CD8+ T cells (Figure 5A). CD8+ T cells were stained in tumor, blood, spleen and TdLN once the tumor reached 7–9 mm diameter and the ratio of WT to knockout CD8+ T cells was assessed. The ratios of WT to knockout CTLs in TdLN were similar across all the groups and close to 1–1.5 (Figure 5B). WT CD8+ T cells infiltrated into tumors around 3 fold more as compared to BLT1−/− CD8+ T cells, around 8 fold more as compared to CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells and around 5.5 fold more as compared to BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells (Figure 5C). These studies suggest that WT cells do not facilitate additional knockout CTL infiltration to tumors.

Figure 5. WT CD8+ T cells do not facilitate knockout CD8+ T cell infiltration to tumors.

UBC-GFP mice were used as the WT mice in this experiment to differentiate between WT and knockout CTLs. Rag2−/− mice were challenged with 105 B16 cells. Two days later CD8+ T cells were isolated from the spleen and TdLN of tumor bearing (3-5mm) WT (UBC-GFP mice), BLT1−/− (non GFP), CXCR3−/− (non-GFP) mice and BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− (non-GFP) mice by MACS technique. 0.5 Million WT (GFP+) CD8+ T cells were either mixed with 0.5 million BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− or BLT1−/−CXCR3−/− (DKO) CD8+ T cells and were injected i.v. in Rag2−/− mice. Animals were sacrificed when the tumors reached 7-8mm tumor diameter. The percentage of WT and knockout CD8+ T cells were determined upon gating on live CD8+ T cells and looking for GFP+ and GFP− populations respectively. A, Representative dot plots of GFP+(WT) and GFP− (KO) CTLs transferred in tumor inoculated Rag2−/− mice and corresponding cumulative graph of ratio of %WT to %KO CTLs injected which is equal to 1. B, Representative dot plots of %WT and %KO CTLs obtained from TdLNs of Rag2−/− mice when the tumor reaches 7-8mm tumor diameter. The %GFP+ and %GFP- is shown after gating on CD8+ T cells. Cumulative bar graph demonstrating the ratio of %WT to %KO CTLs in TdLN is also shown. C, Representative dot plots of %WT and %KO CTLs obtained from tumor of Rag2−/− mice when the tumor reaches 7-8mm tumor diameter. The %GFP+ and %GFP- is shown after gating on CD8+ T cells. Cumulative bar graph demonstrating the ratio of %WT to %KO CTLs in TdLN is also shown. Bar in black represents WT + BLT1−/− CTL mix; grey bars represent WT + CXCR3−/− CTL mix and light grey bar represents WT + DKO CTL mix. Data is representative of two independent experiments for each transferred combination with n=5 in each experimental group.

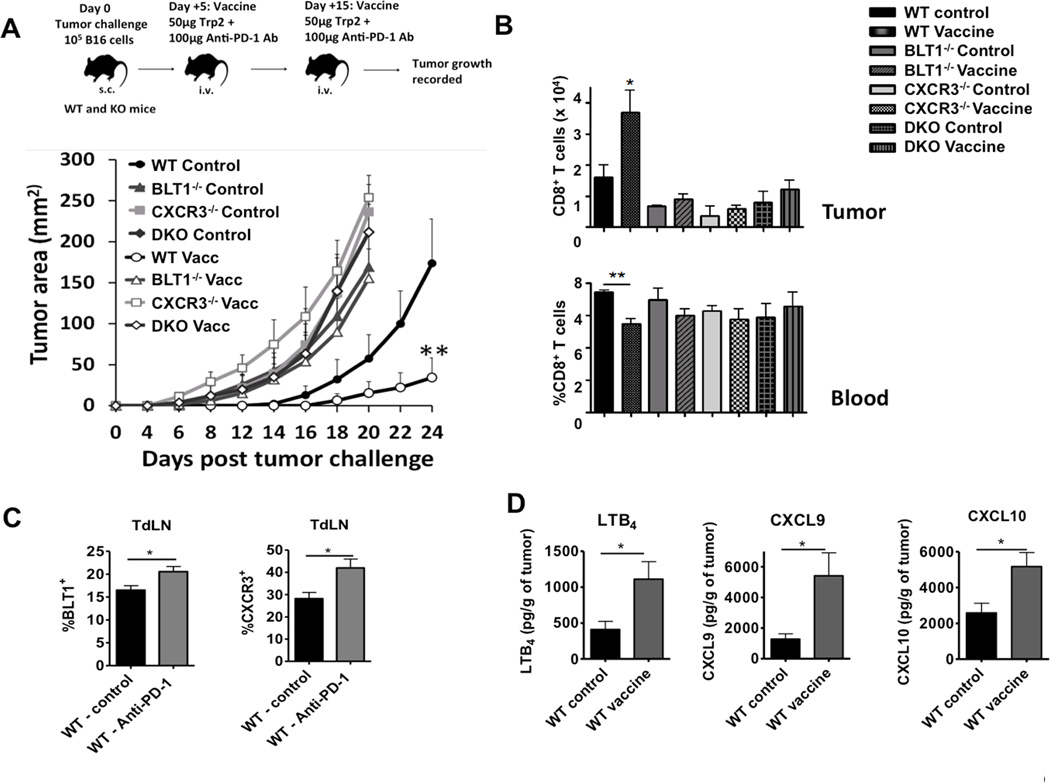

Obligate requirement for BLT1 and CXCR3 in anti-PD-1 Ab based immunotherapy efficacy

Next, the importance of BLT1 and CXCR3 in anti-PD1 antibody enhanced anti-tumor immune response was determined. WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1/CXCR3−/− mice were challenged with 105 B16 cells subcutaneously on Day 0 followed by vaccine administration on day +5 and day +15. Although the vaccine did not completely eradicate the tumors in WT mice, there was a significant reduction in the tumor growth kinetics in WT mice. However, the vaccine completely failed to delay tumor growth in the BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and BLT1/CXCR3−/− animals (Figure 6A). The vaccine efficacy correlated with CD8+ T cell infiltration to tumors, with significantly reduced CTL infiltration in tumors of knockout mice upon vaccination. As expected the vaccine decreased CTL numbers in the blood of WT mice as a reflection of the concurrent increase in the CTLs in tumors of WT mice (Figure 6B). The percentages of CD8+ T cells in the TdLNs and spleens of the knockout animals were comparable to the WT animals in both the vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts (data not shown).

Figure 6. Obligate requirement of BLT1 and CXCR3 for optimum efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibody based immunotherapy.

WT (Unvacc: n=4, Vacc: n=6), BLT1−/− (Unvacc: n=5, Vacc: n=5), CXCR3−/− (Unvacc: n=3, Vacc: n=5) and DKO (Unvacc: n=6, Vacc: n=5) mice were subcutaneously challenged with 105 B16 cells and left either unvaccinated (PBS) or vaccinated with Trp-2 peptide (50µg) and anti-PD-1 Ab (100µg) twice intravenously on day +5 and +15 post tumor inoculation. A, Tumor area measured by multiplication of two perpendicular diameters in unvaccinated and vaccinated WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and DKO mice is shown. B, Cumulative bar graph representing CD8+ T cell numbers per million total tumor cells (frequency of total) in unvaccinated and vaccinated WT, BLT1−/−, CXCR3−/− and DKO mice is represented. Cumulative bar graph representing %CD8+ T cells (frequency of CD45+ cells) in blood of these mice is also shown. Data is representative of two independent experiments. C. BLT1+ and CXCR3+ CTLs are enhanced upon PD-1 blockade. WT tumor bearing mice underwent PD-1 blockade immunotherapy or no immunotherapy as control. The mice were sacrificed and TdLN were obtained after 3 days post booster vaccine dose. BLT1 and CXCR3 staining on CTLs were carried out as mentioned in the methods section. Cumulative bar graph showing percentages of BLT1+ and CXCR3+ CD8+ T cells (frequency of CD8+ T cells) is shown. n=5 in each group. Data is representative of two independent experiments. D, Enhanced LTB4, CXCL9 and CXCL10 levels in tumor after PD-1 blockade immunotherapy. LTB4, CXCL9 and CXCL10 measurements in tumors from WT vaccinated and unvaccinated was carried out as mentioned in the methods. Cumulative bar graphs representing LTB4, CXCL9 and CXCL10 as pg/g of tumor tissue is shown. n=5 in each group. Data is representative of two independent experiments.

To determine whether BLT1 and CXCR3 receptor expression on CTLs are affected by vaccine treatment, CD8+ T cells were stained for BLT1 and CXCR3 after 5 days post-booster vaccine treatment. %BLT1+ and %CXCR3+ populations were significantly enhanced in total CD8+T cells from TdLN upon PD-1 blockade (Figure 6C). In order to understand the levels of ligand expression in the tumors upon PD-1 blockade, tumors from WT unvaccinated and vaccinated mice were homogenized and the tumor supernatant were analyzed for LTB4, by EIA assay and CXCL9 and CXCL10 by ELISA as described in the methods section. The results suggest that PD-1 blockade significantly enhanced the expression of BLT1 and CXCR3 ligands in the tumor milieu (Figure 6D). These results suggest that optimum efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibody relies on both BLT1 and CXCR3 chemoattractant pathways for effective CTL-mediated anti-tumor immunity.

Discussion

Cancer immunotherapies rely on achieving stronger and long lasting effector CD8+ T cell responses in the tumor. A major obstacle for attaining this goal is the inefficient migration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor (12, 17). The results presented here, using murine melanoma and breast cancer models, suggest that both BLT1 and CXCR3 are independently required for CD8+ T cell migration to tumors and sustained anti-tumor immunity. In the absence of either of these receptors, there is a breach in achieving an effective anti-tumor response.

Although BLT1 is expressed on a variety of leukocytes, there is a preferential BLT1 mediated recruitment of certain cells under specific disease condition. For example, Th2 and CD8+ T cells cell infiltration is preferred during airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma, T cells in autoimmune uveitis, macrophages in diet induced obesity and atherosclerosis and neutrophils in silica induced lung cancer promotion; in all of these models genetic deletion of BLT1 was shown to be protective (42–46, 49, 50). Recently, we demonstrated a crucial anti-tumor role of BLT1 in mediating CD8+ T cell recruitment to tumors using TC-1 cervical cancer model wherein BLT1 deficient mice showed enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival compared to WT mice (47). Lack of CTL infiltration to tumors can delay an anti-tumor response in other types of cancers as well. Herein, we investigated the role of BLT1 in autologous B16 melanoma (51) and E0771 breast cancer model. This suggests that BLT1 mediated regulation of CTL infiltration may be important across a variety of immunogenic solid tumor types including cervical cancers, melanoma and breast cancers. Previous studies have reported a pro-tumorigenic role of BLT1-LTB4 pathway in various tumors types including melanoma (52–56). In contrast, our studies highlight the importance of BLT1 on immune cells (CTLs) in achieving an effective anti-tumor response. Moreover, the data presented here suggests that in the absence of BLT1, major CTL chemokine receptors like CXCR3 that have been demonstrated to be indispensable for T cell trafficking at the tumor vasculature (29), cannot achieve optimum CTL infiltration to tumors and anti-tumor immunity. In a GM-CSF gene transduced leukemia model, Yokota et.al showed that BLT1 knockout mice showed similar or better primary and recall immune responses that were attributed to reduced myeloid derived suppressor cell population in the tumors of BLT1 deficient mice and robust CD4 dependent anti-tumor responses(56). The divergence in the results observed herein, may be due to the differences in the mouse strains (BALB/c), tumor model (leukemia) and expression of GM-CSF in the tumor cells (56). In our model, we did not find any difference in the numbers of CD4+ T cells, NK cells or myeloid cells in the tumors of BLT1−/− mice. However, the helper contributions of CD4+ T cells and NK cells in CD8+ T cell mediated anti-tumor immunity may not be excluded. Hence, BLT1 mediated recruitment of various immune cells at specific locations in different tumor models is key to the type of inflammation (pro-tumor or anti-tumor) that accrues. In melanoma, BLT1 mediated CD8+ T cell infiltration to tumors is a crucial mechanism for effective anti-tumor immunity.

The role of CXCR3 and the ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 in anti-tumor immunity is well established (29, 34, 57, 58). In a recent study, Mikuchi et.al elegantly demonstrated that CXCR3 mediated signalling to be a critical and an indispensable checkpoint for tumor antigen specific CD8+ T cells to traffic across the tumor vasculature for carrying out effective tumoricidal activity in mice and human melanoma (29). CTL chemokine receptors CCR5 and CCR2 were not essential for CXCR3 mediated CTL extravasation across tumor vessels despite the presence of CCL2 and CCL5 chemokines in the tumor milieu. Using an antigen specific B16Ova - OT-I system and ACT setting, they showed that WT OT-I but not CXCR3−/− OT-I CTLs were able to significantly reduce tumors; with 50% of WT OT-I transferred mice showing complete tumor regression. Consistent with their study, our data from tumor kinetics in WT v/s CXCR3−/− mice as well as adoptive transfer of tumor educated WT or CXCR3−/− CTLs suggest an indispensable role for CXCR3 in mediating CTL recruitment. Moreover, the current study also demonstrated that both CXCR3−/− as well as BLT1−/− mice are completely unresponsive to PD-1 blockade based immunotherapy. In line with this, our data suggests an additional indispensable requirement for BLT1 for endogenous anti-tumor immunity and therapeutic efficacy. Mikuchi et. al. demonstrated an essential role for CXCR3 in mediating firm adhesion of tumor Ag specific CD8+ T cells at the tumor vessels while not affecting the rolling property of the CTLs (29). However, at what juncture of the multi-step trafficking process is BLT1 required on CD8+ T cells for homing into tumors, remains to be determined.

The results presented here suggest that low CTL numbers in tumors seen in BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− mice is not due to enhanced susceptibility to apoptosis of the knockout CTLs in the tumors (Figure S3A), but likely due to migration defect as there is no difference in the survival of WT, BLT1−/− and CXCR3−/− CTLs in the tumors. With respect to the functionality of the CD8+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment, CXCR3 expression plays a crucial role in IFNγ secretion as CXCR3−/− CTLs in the tumors have a defect in IFNγ production. Various other studies have shown similar defects in IFNγ production of CXCR3−/− T cells (28, 59, 60). Perturbed amplification loop in IFNγ production due to reduced effector cell infiltration or increased suppressive function of M2 macrophages in CXCR3−/− mice may be the reasons for defective IFNγ production in CXCR3−/− CD8+ T cells (61, 62). Thus, expression of CXCR3 on CTLs appears crucial for their effector functions in tumors.

Leukocytes express several chemo-attractant receptors in overlapping patterns and respond to multiple chemo-attractant cues that may be present at the target tissue. Using a simplified 2D agarose based system that integrated sequential exposure to IL-8 and LTB4, it was shown that neutrophils can migrate up a primary gradient of IL-8 into a disorienting concentration but later could effectively retain the capacity to resume migration to a secondary gradient of LTB4, suggesting a potential for step-by-step navigation in complex chemo-attractant fields (63). Hence, two attractant pathways specific for the same cell may function together rather than being redundant in order to effectively recruit immune cells. Receptor expression studies indicated that almost all in vitro activated CTLs (92.3%) are CXCR3+, out of which around 31% are BLT1+. On the other hand, all BLT1+ CTLs are also CXCR3+ (Figure S4). Our studies suggest that BLT1 and CXCR3 seem to play an essential, non-redundant, cell-autonomous role in collectively mediating CD8+ T cell infiltration to tumors and anti-tumor immunity.

We examined the combinatorial regulation of CTL infiltration to tumors by BLT1 and CXCR3 via generation of BLT1/CXCR3 double knockout mice (DKO). The data presented here suggest a lack of synergism in BLT1 and CXCR3 as there was no further enhancement of tumor growth in the DKO mice compared to either of the single knockout mice. Similar migration of ex vivo activated WT CTLs in response to both LTB4 and CXCL10 as compared to either LTB4 or CXCL10 alone suggests lack of synergism.

Studies in an arthritis model revealed that BLT1 mediated infiltration of WT neutrophils in BLT1−/− mice facilitated infiltration of endogenous BLT1−/− neutrophils to the inflamed joint suggesting that BLT1 expression on neutrophils is essential only for the initial recruitment and other chemokines could then perpetuate the disease progression (64). However, our co-transfer experiments with WT and individual knockout CTLs revealed that WT CTLs do not facilitate additional BLT1−/− or CXCR3−/− CTL infiltration to tumors suggesting that BLT1 and CXCR3 mediated signalling cannot be bypassed by other chemoattractant systems for CTL migration in to tumors. These results suggest that BLT1 and CXCR3 signalling pathways do not act in a synergistic manner. However, neither BLT1 nor CXCR3 can be bypassed and an intact anti-tumor response requires both BLT1 and CXCR3 signalling for efficient CTL migration to tumors.

Mikuchi et. al demonstrated a crucial role of CXCR3 in migration of CTLs to tumors using short-term migration assays to assess migration aspect of CTLs alone, not letting other parameters like survival, retention and egress to interfere. However, in our endogenous tumor model (not-Ova-OT-1system) we were unable to detect WT or knockout CTLs in the tumor after 2hrs of CTL transfer. It is plausible that in our system migration of CTLs to tumors follows a different kinetic due to self-antigens compared to Ova specific OT-1 cells.

Blockade of Programmed cell Death-1 (PD-1) pathway has been a promising anti-tumor immunotherapy in humans (65–68). Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy was shown to enhance infiltration of adoptively transferred T cells (68). We used the PD-1 blockade based vaccine model to assess the involvement of BLT1 and CXCR3 in achieving PD-1 blockade based efficacy. PD-1 blockade in conjunction was Trp-2 peptide showed similar efficacy compared to PD-1 blockade alone (data not shown). Hence it seems antigen specific stimulation is not required for PD-1 blockade efficacy. While enhancing CD8+ T cell numbers in tumors and thus reducing tumor growth in WT mice, the vaccine lost its efficacy in mice lacking either or both BLT1 and CXCR3 receptors. Additionally, PD-1 blockade significantly enhanced the expression of LTB4, CXCL9 and CXCL10 in the tumors as well as enhanced the %BLT1+ and %CXCR3+ CTLs in TdLN, suggesting a mechanism by which there may be enhanced T cell infiltration in tumors upon vaccination (Figure 6). The CTLs from the tumors however, did not show any detectable expression of BLT1 or CXCR3 (data not shown). Previous studies have shown that chemoattractant receptors get internalized in cells when they reach the site of inflammation (47, 49). Recent studies on patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors suggest that the responsiveness to PD-1 blockade depends on a certain threshold of CD8+ T cell densities in the tumors. Mutational landscape of the tumor dictates whether the tumor assumes a T cell-inflamed (presence of CTLs) or a non-T cell inflamed phenotype (absence of CTLs) and responsiveness to therapy (69). The data presented here suggests, yet another mechanism that governs T cell inflamed or non-T cell inflamed tumor phenotype. In the absence of either or both BLT1 and CXCR3 receptors, there is a defect in T cell infiltration leading to a “non-T cell inflamed” tumor that fails to respond to PD-1 blockade therapy.

In lung metastatic melanoma model, melanoma cells were shown to be a source for CXCL9 and CXCL10 production. Among the immune cells, CD4+ T cells were considered the major producers of CXCL9 as well as IFNγ in the metastatic nodules in lung (34). While most myeloid cells can readily produce LTB4, the source of this BLT1 ligand in the B16 tumors remains to be determined.

Taken together, these results suggest critical and non-redundant roles for BLT1 and CXCR3 in regulating CTL migration to tumors and antitumor immunity. By targeting these receptor pathways the efficacy of current immunotherapy approaches including ACT and PD-1 blockade may be enhanced.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Becca Baby for support of animal colony maintenance.

This work was supported by the NIH grant R01 CA138623 (BH), The James Graham Brown Cancer Center (BH) and Careers in Immunology Fellowships (ZC) (AAI)

References

- 1.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Waldner M, Obenauf AC, Angell H, Fredriksen T, Lafontaine L, Berger A, Bruneval P, Fridman WH, Becker C, Pages F, Speicher MR, Trajanoski Z, Galon J. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity. 2013;39:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, Bundy B, Nishikawa H, Qian F, Jungbluth AA, Frosina D, Gnjatic S, Ambrosone C, Kepner J, Odunsi T, Ritter G, Lele S, Chen YT, Ohtani H, Old LJ, Odunsi K. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cipponi A, Wieers G, van Baren N, Coulie PG. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes: apparently good for melanoma patients. But why? Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2011;60:1153–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Goedemans R, Doorduijn EM, van Ham JJ, Gorter A, van Hall T, Kuijjer ML, van Poelgeest MI, van der Burg SH, Jordanova ES. Tumor-infiltrating CD14-positive myeloid cells and CD8-positive T-cells prolong survival in patients with cervical carcinoma. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2013;133:2884–2894. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Houdt IS, Sluijter BJ, Moesbergen LM, Vos WM, de Gruijl TD, Molenkamp BG, van den Eertwegh AJ, Hooijberg E, van Leeuwen PA, Meijer CJ, Oudejans JJ. Favorable outcome in clinically stage II melanoma patients is associated with the presence of activated tumor infiltrating T-lymphocytes and preserved MHC class I antigen expression. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2008;123:609–615. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maus MV, Grupp SA, Porter DL, June CH. Antibody-modified T cells: CARs take the front seat for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2014;123:2625–2635. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-492231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinrichs CS, Rosenberg SA. Exploiting the curative potential of adoptive T-cell therapy for cancer. Immunol Rev. 2014;257:56–71. doi: 10.1111/imr.12132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA, Sherry RM, Morton KE, Scharfman WJ, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Royal RE, Kammula U, Restifo NP, Hughes MS, Schwartzentruber D, Berman DM, Schwarz SL, Ngo LT, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Steinberg SM. Tumor progression can occur despite the induction of very high levels of self/tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;175:6169–6176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon EK, Carpenito C, Sun J, Wang LC, Kapoor V, Predina J, Powell DJ, Jr, Riley JL, June CH, Albelda SM. Expression of a functional CCR2 receptor enhances tumor localization and tumor eradication by retargeted human T cells expressing a mesothelin-specific chimeric antibody receptor. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4719–4730. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher DT, Chen Q, Appenheimer MM, Skitzki J, Wang WC, Odunsi K, Evans SS. Hurdles to lymphocyte trafficking in the tumor microenvironment: implications for effective immunotherapy. Immunol Invest. 2006;35:251–277. doi: 10.1080/08820130600745430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma RK, Chheda ZS, Jala VR, Haribabu B. Regulation of cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte trafficking to tumors by chemoattractants: implications for immunotherapy. Expert review of vaccines. 2014:1–13. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.982101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bedognetti D, Wang E, Sertoli MR, Marincola FM. Gene-expression profiling in vaccine therapy and immunotherapy for cancer. Expert review of vaccines. 2010;9:555–565. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motz GT, Santoro SP, Wang LP, Garrabrant T, Lastra RR, Hagemann IS, Lal P, Feldman MD, Benencia F, Coukos G. Tumor endothelium FasL establishes a selective immune barrier promoting tolerance in tumors. Nature medicine. 2014;20:607–615. doi: 10.1038/nm.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melero I, Rouzaut A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T-cell and NK-cell infiltration into solid tumors: a key limiting factor for efficacious cancer immunotherapy. Cancer discovery. 2014;4:522–526. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellone M, Calcinotto A. Ways to enhance lymphocyte trafficking into tumors and fitness of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:231. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franciszkiewicz K, Boissonnas A, Boutet M, Combadiere C, Mami-Chouaib F. Role of chemokines and chemokine receptors in shaping the effector phase of the antitumor immune response. Cancer research. 2012;72:6325–6332. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohta M, Tanaka F, Yamaguchi H, Sadanaga N, Inoue H, Mori M. The high expression of Fractalkine results in a better prognosis for colorectal cancer patients. International journal of oncology. 2005;26:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumura S, Wang B, Kawashima N, Braunstein S, Badura M, Cameron TO, Babb JS, Schneider RJ, Formenti SC, Dustin ML, Demaria S. Radiation-induced CXCL16 release by breast cancer cells attracts effector T cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:3099–3107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavergne E, Combadiere C, Iga M, Boissonnas A, Bonduelle O, Maho M, Debre P, Combadiere B. Intratumoral CC chemokine ligand 5 overexpression delays tumor growth and increases tumor cell infiltration. Journal of immunology. 2004;173:3755–3762. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gough M, Crittenden M, Thanarajasingam U, Sanchez-Perez L, Thompson J, Jevremovic D, Vile R. Gene therapy to manipulate effector T cell trafficking to tumors for immunotherapy. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:5766–5773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran CJ, Arenberg DA, Huang CC, Giordano TJ, Thomas DG, Misek DE, Chen G, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Hanash S, Beer DG. RANTES expression is a predictor of survival in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:3803–3812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Martin A, Gomez L, Lustgarten J, Mira E, Manes S. Maximal T cell-mediated antitumor responses rely upon CCR5 expression in both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells. Cancer research. 2011;71:5455–5466. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin S, Rottman JB, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch AE, Moser B, Mackay CR. The chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;101:746–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groom JR, Luster AD. CXCR3 in T cell function. Experimental cell research. 2011;317:620–631. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friese MA, Fugger L. Autoreactive CD8+ T cells in multiple sclerosis: a new target for therapy? Brain : a journal of neurology. 2005;128:1747–1763. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helbig KJ, Ruszkiewicz A, Lanford RE, Berzsenyi MD, Harley HA, McColl SR, Beard MR. Differential expression of the CXCR3 ligands in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and their modulation by HCV in vitro. Journal of virology. 2009;83:836–846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01388-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung JH, Zhang H, Moseman EA, Alvarez D, Iannacone M, Henrickson SE, de la Torre JC, Groom JR, Luster AD, von Andrian UH. Chemokine guidance of central memory T cells is critical for antiviral recall responses in lymph nodes. Cell. 2012;150:1249–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mikucki ME, Fisher DT, Matsuzaki J, Skitzki JJ, Gaulin NB, Muhitch JB, Ku AW, Frelinger JG, Odunsi K, Gajewski TF, Luster AD, Evans SS. Non-redundant requirement for CXCR3 signalling during tumoricidal T-cell trafficking across tumour vascular checkpoints. Nature communications. 2015;6:7458. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu M, Guo S, Stiles JK. The emerging role of CXCL10 in cancer (Review) Oncology letters. 2011;2:583–589. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loetscher M, Gerber B, Loetscher P, Jones SA, Piali L, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Chemokine receptor specific for IP10 and mig: structure, function, and expression in activated T-lymphocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1996;184:963–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luster AD, Leder P. IP-10, a -C-X-C- chemokine, elicits a potent thymus-dependent antitumor response in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1993;178:1057–1065. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vicari AP, Caux C. Chemokines in cancer. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2002;13:143–154. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(01)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clancy-Thompson E, Perekslis TJ, Croteau W, Alexander MP, Chabanet TB, Turk MJ, Huang YH, Mullins DW. Melanoma induces, and adenosine suppresses, CXCR3-cognate chemokine production and T cell infiltration of lungs bearing metastatic-like disease. Cancer immunology research. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullins IM, Slingluff CL, Lee JK, Garbee CF, Shu J, Anderson SG, Mayer ME, Knaus WA, Mullins DW. CXC chemokine receptor 3 expression by activated CD8+ T cells is associated with survival in melanoma patients with stage III disease. Cancer research. 2004;64:7697–7701. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dengel LT, Norrod AG, Gregory BL, Clancy-Thompson E, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Slingluff CL, Jr, Mullins DW. Interferons induce CXCR3-cognate chemokine production by human metastatic melanoma. Journal of immunotherapy. 2010;33:965–974. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb045d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musha H, Ohtani H, Mizoi T, Kinouchi M, Nakayama T, Shiiba K, Miyagawa K, Nagura H, Yoshie O, Sasaki I. Selective infiltration of CCR5(+)CXCR3(+) T lymphocytes in human colorectal carcinoma. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 2005;116:949–956. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Poon RT, Hughes J, Feng X, Yu WC, Fan ST. Chemokine receptors support infiltration of lymphocyte subpopulations in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clinical immunology. 2005;114:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samuelsson B, Dahlen SE, Lindgren JA, Rouzer CA, Serhan CN. Leukotrienes and lipoxins: structures, biosynthesis, and biological effects. Science. 1987;237:1171–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.2820055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tager AM, Luster AD. BLT1 and BLT2: the leukotriene B(4) receptors. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;69:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subbarao K, Jala VR, Mathis S, Suttles J, Zacharias W, Ahamed J, Ali H, Tseng MT, Haribabu B. Role of leukotriene B4 receptors in the development of atherosclerosis: potential mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:369–375. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110503.16605.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohnishi H, Miyahara N, Dakhama A, Takeda K, Mathis S, Haribabu B, Gelfand EW. Corticosteroids enhance CD8+ T cell-mediated airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic inflammation by upregulating leukotriene B4 receptor 1. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2008;121:864–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.035. e864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li RC, Haribabu B, Mathis SP, Kim J, Gozal D. Leukotriene B4 receptor-1 mediates intermittent hypoxia-induced atherogenesis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184:124–131. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201012-2039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathis SP, Jala VR, Lee DM, Haribabu B. Nonredundant roles for leukotriene B4 receptors BLT1 and BLT2 in inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol. 2010;185:3049–3056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spite M, Hellmann J, Tang Y, Mathis SP, Kosuri M, Bhatnagar A, Jala VR, Haribabu B. Deficiency of the leukotriene B4 receptor, BLT-1, protects against systemic insulin resistance in diet-induced obesity. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:1942–1949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Satpathy SR, Jala VR, Bodduluri SR, Krishnan E, Hegde B, Hoyle GW, Fraig M, Luster AD, Haribabu B. Crystalline silica-induced leukotriene B4-dependent inflammation promotes lung tumour growth. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7064. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma RK, Chheda Z, Jala VR, Haribabu B. Expression of leukotriene B(4) receptor-1 on CD8(+) T cells is required for their migration into tumors to elicit effective antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2013;191:3462–3470. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haribabu B, Verghese MW, Steeber DA, Sellars DD, Bock CB, Snyderman R. Targeted disruption of the leukotriene B(4) receptor in mice reveals its role in inflammation and platelet-activating factor-induced anaphylaxis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:433–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou RC, Kim ND, Sadik CD, Seung E, Lan Y, Byrne MH, Haribabu B, Iwakura Y, Luster AD. Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascade drives neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Immunity. 2010;33:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liao T, Ke Y, Shao WH, Haribabu B, Kaplan HJ, Sun D, Shao H. Blockade of the interaction of leukotriene b4 with its receptor prevents development of autoimmune uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1543–1549. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. B16 as a mouse model for human melanoma. In: Coligan John E, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. 2001. Chapter 20: Unit 20 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bachi AL, Kim FJ, Nonogaki S, Carneiro CR, Lopes JD, Jasiulionis MG, Correa M. Leukotriene B4 creates a favorable microenvironment for murine melanoma growth. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1417–1424. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wejksza K, Lee-Chang C, Bodogai M, Bonzo J, Gonzalez FJ, Lehrmann E, Becker K, Biragyn A. Cancer-produced metabolites of 5-lipoxygenase induce tumor-evoked regulatory B cells via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:2575–2584. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tong WG, Ding XZ, Hennig R, Witt RC, Standop J, Pour PM, Adrian TE. Leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist LY293111 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2002;8:3232–3242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ihara A, Wada K, Yoneda M, Fujisawa N, Takahashi H, Nakajima A. Blockade of leukotriene B4 signaling pathway induces apoptosis and suppresses cell proliferation in colon cancer. J Pharmacol Sci. 2007;103:24–32. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0060651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokota Y, Inoue H, Matsumura Y, Nabeta H, Narusawa M, Watanabe A, Sakamoto C, Hijikata Y, Iga-Murahashi M, Takayama K, Sasaki F, Nakanishi Y, Yokomizo T, Tani K. Absence of LTB4/BLT1 axis facilitates generation of mouse GM-CSF-induced long-lasting antitumor immunologic memory by enhancing innate and adaptive immune systems. Blood. 2012;120:3444–3454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-383240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chow MT, Luster AD. Chemokines in Cancer. Cancer immunology research. 2014;2:1125–1131. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong M, Puaux AL, Huang C, Loumagne L, Tow C, Mackay C, Kato M, Prevost-Blondel A, Avril MF, Nardin A, Abastado JP. Chemotherapy induces intratumoral expression of chemokines in cutaneous melanoma, favoring T-cell infiltration and tumor control. Cancer research. 2011;71:6997–7009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu L, Huang D, Matsui M, He TT, Hu T, Demartino J, Lu B, Gerard C, Ransohoff RM. Severe disease, unaltered leukocyte migration, and reduced IFN-gamma production in CXCR3−/− mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:4399–4409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Groom JR, Richmond J, Murooka TT, Sorensen EW, Sung JH, Bankert K, von Andrian UH, Moon JJ, Mempel TR, Luster AD. CXCR3 chemokine receptor-ligand interactions in the lymph node optimize CD4+ T helper 1 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;37:1091–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Campbell JD, Gangur V, Simons FE, HayGlass KT. Allergic humans are hyporesponsive to a CXCR3 ligand-mediated Th1 immunity-promoting loop. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2004;18:329–331. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0908fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oghumu S, Varikuti S, Terrazas C, Kotov D, Nasser MW, Powell CA, Ganju RK, Satoskar AR. CXCR3 deficiency enhances tumor progression by promoting macrophage M2 polarization in a murine breast cancer model. Immunology. 2014;143:109–119. doi: 10.1111/imm.12293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foxman EF, Campbell JJ, Butcher EC. Multistep navigation and the combinatorial control of leukocyte chemotaxis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.5.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim ND, Chou RC, Seung E, Tager AM, Luster AD. A unique requirement for the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 for neutrophil recruitment in inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:829–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Horn LA, Haile ST. The programmed death-1 immune-suppressive pathway: barrier to antitumor immunity. Journal of immunology. 2014;193:3835–3841. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sznol M, Chen L. Antagonist antibodies to PD-1 and B7-H1 (PD-L1) in the treatment of advanced human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1021–1034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sakuishi K, Apetoh L, Sullivan JM, Blazar BR, Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:2187–2194. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peng W, Liu C, Xu C, Lou Y, Chen J, Yang Y, Yagita H, Overwijk WW, Lizee G, Radvanyi L, Hwu P. PD-1 blockade enhances T-cell migration to tumors by elevating IFN-gamma inducible chemokines. Cancer research. 2012;72:5209–5218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.