Abstract

Here, we study the molecular evolution of a near complete set of genes that had functional evidence in the regulation of the Drosophila germline and neural stem cell. Some of these genes have previously been shown to be rapidly evolving by positive selection raising the possibility that stem cell genes as a group have elevated signatures of positive selection. Using recent Drosophila comparative genome sequences and population genomic sequences of Drosophila melanogaster, we have investigated both long- and short-term evolution occurring across these two different stem cell systems, and compared them with a carefully chosen random set of genes to represent the background rate of evolution. Our results showed an excess of genes with evidence of a recent selective sweep in both germline and neural stem cells in D. melanogaster. However compared with their control genes, both stem cell systems had no significant excess of genes with long-term recurrent positive selection in D. melanogaster, or across orthologous sequences from the melanogaster group. The evidence of long-term positive selection was limited to a subset of genes with specific functions in both the germline and neural stem cell system.

Keywords: Drosophila, germline stem cell, neural stem cell, population genomics, positive selection, adaptive evolution

Introduction

Stem cells are a unique group of undifferentiated cells capable of undergoing asymmetric division to renew itself and/or generate a daughter cell that will undergo terminal differentiation. How the stem cell is able to balance the transition from self-renewal to differentiation has been extensively studied in various organisms. Specifically in Drosophila, studies have hypothesized a microenvironment surrounding the stem cell (termed the stem cell niche) controls the fate of the stem cell through cell–cell interaction and asymmetric signaling (Losick et al. 2011). In the adult Drosophila, the stem cell niche has been found in various biological systems such as in the germline, hematopoietic, intestinal, and neural tissues, suggesting that the niche is a conserved mechanism that regulates the development of most Drosophila stem cells (Yamashita et al. 2005; Morrison and Spradling 2008).

Developmentally all stem cells need to be tightly regulated as uncontrolled differentiation leads to rapid depletion of stem cells, whereas uncontrolled self-renewal leads to an excess of stem cells resembling tumorigenesis. Thus, there are series of intricate genetic pathways that assure the initiation of correct self-renewal and differentiation after each stem cell division (Doe 2008; Losick et al. 2011; Spradling et al. 2011; Lehmann 2012). Most mutations occurring across the genes that control the stem cell development are then predicted to be strongly deleterious, as perturbations would cause sterility or lethality. Evolutionarily, the genes involved in regulation and development of the stem cell system might thus be predicted to be dominated by purifying selection, that is, selection purging deleterious mutations, resulting in a slower rate of evolution compared with the genomic background.

Targeted studies of several Drosophila germline stem cell (GSC) regulating genes, however, have found several of these genes to be evolving rapidly due to strong positive selection, that is, selection favoring advantageous mutations (Civetta et al. 2006; Bauer DuMont et al. 2007; Choi and Aquadro 2014; Flores, Bubnell, et al. 2015). In addition, population genomic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans has shown an enrichment for gene ontology (GO) categories related to oogenesis and spermatogenesis across genes with evidence of positive selection (Begun et al. 2007; Langley et al. 2012; Pool et al. 2012). GSC regulating genes are involved in the maintenance and differentiation of the germline and in some cases, the expression of these genes are so tightly regulated that even being one cell diameter away from the germline cap cells leads to rapid differentiation (Li and Xie 2005; Lehmann 2012). Thus, these genes were originally expected to be under evolutionary constraint. However, evidence of rapid evolution in some of the GSC regulating genes raises the possibility that genes involved in GSC function are actually enriched for positive selection, motivating a system wide analysis of this specific group of genes.

The neural stem cell (NSC) is another Drosophila stem cell system that has been extensively studied for its stem cell biology (Doe 2008) but lacks characterization of its molecular evolution in Drosophila. Interestingly, a study of the nematode Caenorhabditis remanei showed that transcription factors involved in the differentiation of chemosensory neurons were rapidly evolving compared with other neural development genes (Jovelin 2009). Thus, it would be important to establish the extent of positive selection occurring across the Drosophila NSC system as well.

The main goal of our study was to examine and compare the evolution of genes involved in Both germline and neural Stem Cell (BSC) regulation. Using genes identified from previous comparable high throughput genetic screens in the GSC (Yan et al. 2014) and NSC (Neumüller et al. 2011) system, we have analyzed the evolution of genes that have functional evidence in the GSC, NSC, and involved in BSC regulation. We tested whether particular stem cell systems were enriched for genes with evidence of positive selection by comparing the evolution of each stem cell class to a carefully chosen set of random genes that either 1) had similar sequence characteristics to each stem cell regulating genes or 2) its genomic position was close to each stem cell regulating genes. Using existing and new draft Drosophila genome sequences (Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2014) and population genomic sequences from D. melanogaster (Lack et al. 2015), we have examined both the long- and short-term evolution occurring in genes with stem cell developmental function.

Materials and Methods

GSC and NSC Regulating Genes Analyzed

Neumüller et al. (2011) had screened 89% of the D. melanogaster annotated genes to identify 620 genes involved in the regulation of NSCs (see supplementary table S2 from https://neuroblasts.imba.oeaw.ac.at/downloads.php, last accessed November 2015 for full list of the NSC regulating genes), whereas Yan et al. (2014) had screened 25% of the D. melanogaster annotated genes to identify 366 genes involved in the regulation of GSCs (see supplementary table S1 of Yan et al. 2014 for full list of the GSC regulating genes). Flybase ID (i.e., FBgn number) for each stem cell regulating genes was based on release 5.50 for the GSC genes and release 5.7 for the NSC genes. To make the FBgn names comparable between the two data sets and identify genes involved in both GSC and NSC regulation, all FBgn names were converted to release 5.57. After converting the names, FBgn0036315 and FBgn0052108, which were originally identified as two separate NSC regulating genes from Neumüller et al. (2011), were in fact the same gene and named as FBgn0260965 in Flybase release 5.57. Thus, there were in fact 619 genes involved in the NSC regulation.

We have focused on stem cell regulating genes that have been examined in both studies of Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014), which comprised 262 GSC genes, 144 NSC genes, and 104 BSC genes (full list of genes available at supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). This was necessary due to the lower total number of genes screened genome-wide by Yan et al. (2014), where more than half of the genes involved in the regulation of NSCs have not been examined by Yan et al. (2014) for their potential function in the GSC. We note that these numbers are slightly different from that reported by Yan et al. (2014); however, numbers from the former study were erroneously reported (Yan D, personal communication).

Population Genetics of D. melanogaster Stem Cell Regulating Genes

Filtering and Preparing the Population Data Set for Downstream Analysis

Consensus sequences for the D. melanogaster population genome data were obtained from the Drosophila Population Genomics Project 3 study (Lack et al. 2015). We have examined the genome sequences from lines originating from Siavonga, Zambia, a location thought to represent the ancestral range of D. melanogaster (Pool et al. 2012). Genomic regions with evidence of identity-by-descent and admixture (Pool et al. 2012; Duchen et al. 2013) were masked using the genome coordinates and Perl scripts supplied by the Drosophila Genome Nexus website (http://johnpool.net/genomes.html, last accessed November 2015). Genes located on the fourth chromosome and in heterochromatic regions were excluded to avoid evolutionary effects associated with linked positive and background selection in regions with very low rates of recombination (following Arguello et al. 2010 and Campos et al. 2012).

Only the coding DNA sequence (CDS) was analyzed for each gene as we were mainly interested in the positive selection occurring across the amino acid coding sequences. Using the D. melanogaster release 5.57 from Flybase, the longest transcript for each gene was chosen for further analysis. Custom filters were imposed to deal with sites that had missing information (“N”). Initially, if any individual sequence had more than 5% of its sequence consisting of “N” that sequence as a whole was removed. Next, we examined every polymorphic site to check whether that polymorphic site also had any individuals with “N.” In any case a polymorphic site had some individuals with “N,” we removed the entire sequence of the individual with the missing site to preserve the polymorphic site for downstream analysis. Finally after these two steps any sites that still have “N” are monomorphic throughout the population except for the individual with “N,” thus we masked the entire codon in all the individuals to prevent that codon from being analyzed. Due to the varying number of individuals being filtered out in the previous filtering step, sample sizes varied among genes. To unify the sample size, we analyzed genes where we could choose 50 random individual sequences. Interspecific sequence divergence for each CDS was estimated by comparing the D. melanogaster CDS with the orthologous Drosophila yakuba CDS, which was aligned by using the codon aware realignment program transAlign (Bininda-Emonds 2005).

Two random control genes were chosen for each stem cell regulating gene. The first random control was selected on a set of five stringent criteria: 1) Genes not identified as having a stem cell regulatory function, 2) genes located on the same chromosome as the stem cell regulating gene in question, and 3) similar recombination environment. Using genome-wide recombination rate (cM/Mb) estimates from Comeron et al. (2012), the recombination rate between the start codon and the stop codon (which includes both exons and introns of gene) of each stem cell regulatory gene was estimated. The same was applied to estimate recombination rates for all annotated genes in the D. melanogaster genome. Here, a random gene was selected as a control gene when its estimated recombination rate was within ±25% of the stem cell regulating genes’ recombination rate, 4) genes within ±25% of the stem cell regulating genes’ genomic size which ranges from the start codon to the stop codon (this includes both exons and introns of a gene), and 5) genes being within ±25% of the stem cell regulating genes’ CDS length. The second set of random control genes was selected based on their physical proximity to the stem cell gene, specifically with the criteria: 1) Not identified as having a stem cell regulatory function, and 2) not more than 5 kb away from the start or stop codon of the stem cell gene. The population sequences that were used in this study are available upon request.

DNA Sequence Statistics Calculation

Codon usage statistics for each gene were estimated using the program CodonW (http://sourceforge.net/projects/codonw/, last accessed November 2015) for the frequency of optimal codon (FOP) (Ikemura 1981) and the effective number of codon (ENC) (Wright 1990) statistics. The codon usage table of D. melanogaster (Shields et al. 1988; Akashi 1995) was used for the estimates of FOP.

Recombination rate (cM/Mb) for each gene was calculated using the Perl scripts from D. melanogaster Recombination Rate Calculator version 2.3 (http://petrov.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/recombination-rates_updateR5.pl, last accessed November 2015) (Fiston-Lavier et al. 2010) using the high-resolution recombination maps from Comeron et al. (2012). The full genomic location of each gene, which includes intron and exon, starting from the start codon and ending at the stop codon was used for estimating the rate of recombination. A single midpoint estimate of the rate of recombination was assigned as each gene’s recombination rate.

DNA Sequence Polymorphism and Divergence Analysis

The population genetic analysis software suite from K. Thornton (https://github.com/molpopgen/analysis last accessed November 2015) and his libsequence package (Thornton 2003) was used for DNA polymorphism analysis. The polydNdS program was used to estimate levels of synonymous and nonsynonymous site polymorphism, whereas the gestimator program was used to estimate dN and dS between D. melanogaster and D. yakuba using the method of Comeron (1995). The MKtest program was used to estimate the values for the 2×2 table of a McDonald and Kreitman test (MK test) (McDonald and Kreitman 1991). Custom Perl scripts were written to calculate Tajima’s D (TajD) (Tajima 1989) and the normalized Fay and Wu’s H (FWH) (Fay and Wu 2000; Zeng et al. 2006).

To estimate the strength of recurrent positive selection, the polymorphism and divergence table generated from the program MKtest was used to estimate the direction of selection (DoS) statistics (Stoletzki and Eyre-Walker 2011) for each gene. As a variant of the neutrality index (Rand and Kann 1996), DoS measures the degree of positive selection but is more robust to biases caused by low cell counts in the 2×2 MK-test table. Minor allele frequencies lower than 5% were excluded from the polymorphism counts as these could include slightly deleterious mutations (Fay et al. 2001).

The molecular evolutionary statistics for each stem cell class (BSC, GSC, and NSC genes) were compared with its own set of control genes, using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (MWU test).

Proportion of amino acid sites fixed by positive selection (α) was estimated using the method of Messer and Petrov (2013). Briefly, this method calculates α through a modification of the traditional method of Smith and Eyre-Walker (2002) by binning according to the frequency of derived alleles. Assuming constant purifying selection and rapid fixation of adaptive mutations, as the derived allele frequency asymptotically approaches 1 (fixation) the α estimated from binning the derived allele frequency is predicted to converge with the true value of α. Here, the true value of α was estimated by fitting an exponential function of form y = a + b[exp(−cx)] to the data, where y is the value of α when x is the derived allele frequency, and a, b, and c being the parameters to fit the equation. Because different effective population sizes of the autosome and X chromosomes can cause biased estimates of α, only genes on the autosomes were used (we had too few on the X for a meaningful comparison). α was estimated for each stem cell class and its control genes, and the 95% confidence interval for each α was calculated by generating bootstrap samples with replacement.

Estimating Genes with Evidence of Recent Selective Sweeps

Because of the potentially reduced statistical power to detect recent selective sweeps due to analyzing only the coding region sequences of the GSC and NSC genes, we also include here evidence of selective sweeps occurring across each gene’s larger genomic region using the results of Pool et al. (2012). Their study reported whole-genome scans for evidence of recent selective sweeps using the SweepFinder program (Nielsen et al. 2005; Pavlidis et al. 2010) in the Rwanda population sample of D. melanogaster. We note that although this population is from a different locality compared with the Zambia population we analyzed here, it is still part of the sub-Saharan ancestral range of D. melanogaster (Pool et al. 2012). If a stem cell gene or control gene overlapped the outlier window identified from Pool et al. (2012), we here classified the gene as having undergone a recent selective sweep.

We evaluated whether a stem cell class had an overrepresentation of genes with selective sweeps by a permutation-based test using the Pool et al. (2012) SweepFinder results. A sample of genes that matched the total number of autosomal and X chromosomal genes for each GSC, NSC, and BSC group were randomly selected from all D. melanogaster genes. In total, 1,000 of these random groups were generated and for each group we counted the total number of genes with evidence of a selective sweep from the study of Pool et al. (2012). Because we were interested in the probability that a random group of genes would contain more genes with evidence of a selective sweep than our stem cell class, we used a one-tailed test of significance.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of Stem Cell Regulating Genes across the melanogaster Group

Identifying Orthologous Protein-Coding Sequences within the 13 melanogaster Group Species

CDS data from each of the five Drosophila species (D. ananassae, D. erecta, D. sechellia, D. melanogaster, and D. yakuba) were downloaded from Flybase (St Pierre et al. 2014). Additionally, the CDS data for eight newly sequenced Drosophila genomes (D. biarmipes, D. bipectinata, D. elegans, D. eugracilis, D. ficusphila, D. kikkawai, D. takahashii, and D. rhopaloa) were downloaded from the Drosophila modENCODE website (ftp://ftp.hgsc.bcm.edu/DmodENCODE/maker_annotation/, last accessed November 2015). We have focused only within the melanogaster group species to avoid problems associated with the fact that synonymous sites quickly reach saturation when comparing among more divergent species (Barmina and Kopp 2007; Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium et al. 2007).

As the D. melanogaster annotation is arguably the best among the genome-sequenced Drosophila species, we used CDS from the D. melanogaster release 5.57 to find orthologs in non-D. melanogaster species. The CDS of the longest protein sequence for each gene was chosen and any internal stop codons, due to sequencing errors or rare amino acids, were removed as these cannot be analyzed in most evolutionary analysis.

Orthologs were inferred using the reciprocal BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool)-hit approach of the program INPARANOID (Remm et al. 2001). Any orthologs that had any evidence of paralogs were removed. Potential non-D. melanogaster species’ ortholog was considered as a D. melanogaster ortholog if the bootstrap values from the INPARANOID analysis were 100%. For each gene, if there were at least six orthologous sequences it was considered for downstream analysis.

Orthologous Sequence Alignment and Filtering

We have realigned our ortholog data set using the phylogeny aware realignment software PRANK (Löytynoja and Goldman 2008) that has been consistently shown to outperform most realignment algorithms (Markova-Raina and Petrov 2011; Jordan and Goldman 2012; Spielman et al. 2014). The CDS of each gene’s orthologs was realigned using the codon model of PRANK version 140603. After the alignment any individual sequence that contained large regions of gap was removed using the program maxAlign (Gouveia-Oliveira et al. 2007). Multisequence alignments where there were orthologs from more than six species were further trimmed using the program trimAl version 1.2rev59 (Capella-Gutiérrez et al. 2009). trimAl was used to delete sites in the multisequence alignments where more than 20% of the sequences had gaps because these regions could correspond to potentially misannotated regions of the gene. The multiple species alignments that were used in this study are available upon request.

Analysis of the Ortholog Data Set Using Codon-Based Models

Synonymous divergence (dS), nonsynonymous divergence (dN), and their ratio dN/dS (ω) were estimated using the program CODEML from the package PAML version 4.8 (Yang 2007) using Model 0 (M0).

To infer evidence of positive selection across the multispecies alignment, we have applied two codon model-based methods from the software packages PAML and HYPHY version 2.2 (Pond et al. 2005). First, CODEML from the PAML suite was used to fit Model 8 (M8) (Yang et al. 2000). M8 fits a model allowing ω to vary across the site following a beta distribution with evidence of no positive selection (i.e., 0 ≤ ω ≤ 1), while allowing a certain proportion of sites to be under positive selection (ω > 1). M8 was run under three different starting ω values to ensure the global maxima had been reached in the maximum-likelihood estimation. We have inferred evidence of positive selection using the posterior probabilities estimated from the Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) approach (Yang et al. 2005). A site was inferred to have significant evidence of selection if the posterior probability was greater than 0.9. We chose the Bayesian method of PAML to allow comparisons to the method of the HYPHY suite as described below, which also reports evidence of positive selection in Bayesian statistics. The codon frequency model F3×4 was fit to all multispecies alignments.

The second method for detecting evidence of positive selection was using the hierarchical Bayesian method of FUBAR (Murrell et al. 2013) from the HYPHY package. Briefly, FUBAR fits a dense grid of a priori selected values of dN and dS which are later then drawn to infer evidence of selection for each site. For FUBAR, positive selection was inferred for a site when dN − dS > 0 whereas evidence of negative selection was inferred for a site with dN − dS < 0. For the Bayesian parameters, 400 grid points were assigned to represent dN and dS while weights for each grid point were determined using a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach. Five independent MCMC chains were run to ensure convergence while the length of each chain was set at 10 million and a sample was drawn every 2,500 steps. Five million samples were discarded as burn-in. Sites with posterior probability of greater than 0.9 were assumed to have significant evidence of selection.

Method to Correct for Multiple Hypothesis Testing

To control the false positive rates involved with multiple hypothesis testing, we have pooled all hypothesis tests resulting in a P value and applied the method of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) using the program R (https://www.r-project.org/, last accessed November 2015).

Results

Analysis of Recent Positive Selection across D. melanogaster Stem Cell Regulating Genes

We analyzed and compared the molecular population genetics and evolution of three classes of stem cell genes, specifically 1) those expressed only in GSC, 2) genes only expressed in NSC, and 3) genes expressed in both GSC and NSC (abbreviated here as BSC genes). Individual genes of each class were compared with a control group of genes that was selected based on several criteria outlined in Materials and Methods, which we applied in an effort to control for regional gene differences in factors such as recombination rate, nucleotide sequence composition, substitution rate, and mutation rate.

After preprocessing, quality controlling, and selecting two control genes for each stem cell gene, a total of 68 BSC, 159 GSC, and 88 NSC regulating genes were able to be assigned appropriate control genes. Population genetic statistics for each stem cell class and its controls are presented in table 1, with statistics for all genes individually provided in supplementary data S1, Supplementary Material online. Despite the several custom filters implemented on our population data set, an average of 98% of the sites were retained and analyzed for all three stem cell gene classes (BSC, GSC, and NSC) and their respective control genes (table 1). Thus, our data filtering steps are unlikely to have significantly biased our results.

Table 1.

Population Genetic Summary Statistics for the Three Stem Cell Classes and Their Control Genes

| Class | CDS % | Total θπ | Syn θπ | Total TajD | Syn TajD | Total nFWH | Syn nFWH | ω | DoS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | 0.986 | 0.0048 (0.0042, 0.0056) | 0.019 (0.016, 0.024) | −0.814 (−0.978, −0.666) | −0.629 (−0.768, −0.510) | −0.665 (−0.997, −0.465) | −0.886 (−1.246, −0.641) | 0.056 (0.044, 0.073) | 0.049 (0.020, 0.079) |

| BSC control | 0.988 | 0.0057 (0.0047, 0.0063) | 0.022 (0.020, 0.026) | −0.787 (−0.880, −0.707) | −0.497 (−0.630, −0.415) | −0.838 (−0.944, −0.658) | −1.004 (−1.153, −0.821) | 0.05 (0.041, 0.063) | 0.048 (0.029, 0.072) |

| GSC | 0.984 | 0.0038 (0.0034, 0.0046) | 0.015 (0.013, 0.018) | −0.965 (−1.058, −0.876) | −0.789 (−0.903, −0.669) | −0.799 (−0.891, −0.650) | −0.933 (−1.010, −0.811) | 0.047 (0.038, 0.060) | 0.057 (0.048, 0.085) |

| GSC control | 0.989 | 0.0052 (0.0047, 0.0058) | 0.021 (0.019, 0.022) | −0.835 (−0.912, −0.740) | −0.591 (−0.665, −0.465) | −0.782 (−0.873, −0.675) | −0.938 (−1.048, −0.811) | 0.052 (0.048, 0.065) | 0.042 (0.029, 0.059) |

| NSC | 0.986 | 0.0046 (0.0035, 0.0054) | 0.018 (0.014, 0.023) | −0.852 (−1.036, −0.719) | −0.734 (−0.876, −0.556) | −0.736 (−1.016, −0.593) | −0.905 (−1.188, −0.589) | 0.055 (0.034, 0.063) | 0.061 (0.024, 0.077) |

| NSC control | 0.987 | 0.0054 (0.0047, 0.0062) | 0.022 (0.019, 0.025) | −0.871 (−1.016, −0.769) | −0.788 (−0.853, −0.600) | −0.613 (−0.778, −0.545) | −0.794 (−0.945, −0.648) | 0.052 (0.046, 0.062) | 0.042 (0.027, 0.064) |

Note.—CDS %, proportion of analyzed CDSs; Total θπ, total CDS pairwise nucleotide difference per site; Syn θπ, total synonymous pairwise nucleotide difference per site; Total TajD, Tajima’s D across CDS; Syn TajD, Tajima’s D across synonymous sites; Total nFWH, normalized Fay and Wu’s H across CDS; Syn nFWH, normalized Fay and Wu’s H across synonymous sites; ω, rate of evolution measured by nonsynonymous divergence divided by synonymous divergence; Each value represents the median value and in parenthesis are the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals of the median. Significant MWU test after FDR correction (P value < 0.05) between the stem cell class and its control genes are bolded.

As a recent selective sweep can lead to reductions in levels of polymorphism, nucleotide diversity (θπ) was examined for each stem cell class and its control genes (table 1). Compared with their control genes the GSC class genes had a significantly lower level of θπ across all nucleotide sites, as well as for only the synonymous sites (FDR-corrected MWU test P values of 0.0020 and 0.0071, respectively). In contrast, BSC and NSC class genes did not differ significantly from their control genes. Recent selective sweeps can also alter the site frequency spectrum leading to excesses of rare and high frequency-derived alleles that can be detected using TajD and FWH test statistics, respectively. No significant differences in TajD or FWH values were observed between any of the three stem cell gene classes and their control genes when analyzing all sites across the total CDS. However, analyzing only the putatively neutral synonymous sites revealed that the GSC class genes did have significantly more negative TajD values (table 1; FDR-corrected MWU test P value = 0.019) compared with their control genes, consistent with an elevated frequency of recent selective sweeps at or near GSC genes.

We also examined the genomic regions discovered by Pool et al. (2012) to have evidence of selective sweeps using the SweepFinder program, and tabulated our list of stem cell genes they identified as within the swept regions (see Materials and Methods). For this analysis we examined members of the full list of stem cell regulating genes, except genes on the fourth chromosome due to their low recombination rates (see Materials and Methods for detail), regardless of whether we had found a suitable control gene. Ten of 100 (10%) BSC genes, 31 of 259 (12%) GSC genes, and 20 of 144 (14%) NSC genes were identified within the SweepFinder outlier windows from Pool et al. (2012) (see table 2 for full list of genes). We tested for an enrichment of sweep-associated genes among the three stem cell gene classes by comparing the observed numbers with those from a random distribution. In total, 1,000 groups of genes were generated where each group comprised randomly chosen genes from the D. melanogaster genome that matched the total number of autosomal and X chromosomal genes of each stem cell class. Then for each group, the total numbers of genes with evidence of selective sweeps identified by Pool et al. (2012) were counted. This generated a distribution of the total number of genes with evidence of a selective sweep in a randomly selected group of genes. Compared with this random distribution, the GSC and NSC classes were both significantly overrepresented with genes with evidence of recent selective sweeps (FDR-corrected P value = 0.038; FDR P value = 0.022, respectively).

Table 2.

List of Stem Cell Regulating Genes with Evidence of a Recent Selective Sweep Based on the SweepFinder Results of Pool et al. (2012)

| FBgn Name | Gene Name | Literature Annotated Functiona | GO Annotated Molecular Functionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both stem cell | |||

| FBgn0002787 | Rpn8 | GSCMAINT | Endopeptidase activity |

| FBgn0003607 | Su(var)205 | GSCDIFF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Chromatin binding |

| FBgn0010278 | Ssrp | GSCMAINT; NSCDIFF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Single-stranded DNA binding |

| FBgn0020306 | dom | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Helicase activity |

| FBgn0025832 | Fen1 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Endonuclease activity |

| FBgn0030086 | CG7033 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | ATP binding |

| FBgn0259937 | Nop60B | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; NSCSR; Ribosome biogenesis | Pseudouridylate synthase activity |

| FBgn0260399 | gwl | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Protein ser/thr kinase activity |

| FBgn0261617 | nej | GSCDIFF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Transcription coactivator activity |

| FBgn0265297 | pAbp | GSCMAINT; Translation | Protein binding |

| Germline stem cell | |||

| FBgn0000562 | egl | Translation | mRNA binding |

| FBgn0000996 | dup | GSCMAINT | DNA binding |

| FBgn0001215 | Hrb98DE | Splicing | mRNA binding |

| FBgn0001233 | Hsp83 | — | ATPase activity, coupled |

| FBgn0002791 | mr | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Ubiquitin protein ligase binding |

| FBgn0003676 | T-cp1 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Hydrogen-exporting ATPase activity |

| FBgn0004656 | fs(1)h | GSCMAINT | DNA binding |

| FBgn0004838 | Hrb27C | Splicing | mRNA 3′-UTR binding |

| FBgn0004872 | piwi | — | RNA binding |

| FBgn0011211 | blw | GSCDIFF; Mitochondrial function | Hydrogen-exporting ATPase activity |

| FBgn0011785 | BRWD3 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | — |

| FBgn0013984 | InR | GSCMAINT | Insulin-activated receptor activity |

| FBgn0021796 | Tor | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein kinase activity |

| FBgn0022943 | Cbp20 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Translation | RNA cap binding |

| FBgn0025724 | beta’COP | GSCMAINT | Structural molecule activity |

| FBgn0025830 | IntS8 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Molecular_function |

| FBgn0026252 | msk | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein transmembrane transporter activity |

| FBgn0028411 | Nxt1 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | — |

| FBgn0029113 | Uba2 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Ubiquitin activating enzyme activity |

| FBgn0031493 | CG3605 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Splicing | — |

| FBgn0031883 | CG11266 | — | mRNA binding |

| FBgn0032393 | CG12264 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Cystathionine gamma-lyase activity |

| FBgn0035854 | CG8005 | — | — |

| FBgn0039120 | Nup98-96 | Nuclear pore | Protein binding |

| FBgn0053526 | PNUTS | GSCMAINT | Protein phosphatase regulator activity |

| FBgn0086899 | tlk | — | Protein ser/thr kinase activity |

| FBgn0260934 | Par-1 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein ser/thr kinase activity |

| FBgn0260936 | scny | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Ubiquitin-specific protease activity |

| FBgn0261797 | Dhc64C | GSCDIFF; Kinetochore/Spindle | ATPase activity, coupled |

| FBgn0262647 | Nup160 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Nuclear pore | Protein binding |

| FBgn0262656 | dm | GSCMAINT; Ribosome biogenesis | DNA binding |

| Neural stem cell | |||

| FBgn0000413 | da | NCDDIFF | DNA binding |

| FBgn0002917 | na | — | Cation channel activity |

| FBgn0010328 | woc | — | Protein binding |

| FBgn0015024 | CkIα | — | Protein kinase activity |

| FBgn0020653 | Trxr-1 | — | Protein homodimerization activity |

| FBgn0022238 | lolal | — | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

| FBgn0024921 | Trn | — | Protein transmembrane transporter activity |

| FBgn0025463 | Bap60 | — | Transcription coactivator activity |

| FBgn0025571 | SF1 | — | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0025716 | Bap55 | — | Transcription coactivator activity |

| FBgn0030208 | PPP4R2r | — | Protein phosphatase regulator activity |

| FBgn0031456 | Trn-SR | — | Protein binding |

| FBgn0032388 | CG6686 | — | — |

| FBgn0035422 | RpL28 | — | Structural constituent of ribosome |

| FBgn0036248 | ssp | — | Beta-catenin binding |

| FBgn0038746 | Surf6 | — | Heme transporter activity |

| FBgn0053100 | 4EHP | — | Translation initiation factor activity |

| FBgn0061200 | Nup153 | — | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0261793 | Trf2 | — | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

| FBgn0264962 | Inr-a | — | RNA binding |

Note.—CELLEF, germline general cell essential factor. GSCEF, germline stem cell specific essential factor. NSCCG, neural stem cell regulation of cell growth. NSCSR, neural stem cell self-renewal. Note that these were analyzed from all stem cell regulating gene list identified from both Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014) regardless of whether it was assigned a control gene or not from this study.

aFunctional annotation based on the study of Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014).

bFunctional annotation based on GO categorization on Flybase.

Analysis of Recurrent Adaptive Evolution across D. melanogaster Stem Cell Regulating Genes

Evidence for recurrent positive selection that had occurred along the D. melanogaster lineage was examined for each gene using D. melanogaster polymorphism and divergence to the outgroup D. yakuba orthologs. The ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous divergence (ω) was not significantly different between any stem cell class and its control genes (table 1). Using the polymorphism within D. melanogaster and fixed differences between D. melanogaster and D. yakuba, DoS (Stoletzki and Eyre-Walker 2011) statistics were estimated for each gene to infer the presence and direction of recurrent adaptive evolution. All stem cell classes had a positive median DoS values but none was significantly different from their respective control genes (table 1).

MK tests (McDonald and Kreitman 1991) were also conducted for individual genes to see whether there were differences in the total number of genes with significant MK test result, when comparing each stem cell class with its control genes. Across all stem cell regulating genes, regardless of having a control gene assigned or not, a total of 14 of 95 (14.7%) BSC genes, 40 of 228 (17.5%) GSC genes, and 25 of 132 (18.9%) NSC genes had a significant MK test result before FDR correction (see table 3 for complete list of genes that had significant MK test before and after FDR correction). However, despite the individual genes with significant MK test in each stem cell class, there was no significant difference in the proportion of genes with significant MK test (both before and after FDR corrected MK test P values) in any of the stem cell class compared with its control genes (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online).

Table 3.

List of Stem Cell Regulating Genes with Significant MK Test, Which Detects Recurrent Positive Selection, before and after False Discovery Rate Correction

| FBgn Name | Gene Name | DoSMAF | MK Test P Values | MK Test FDR P Values | Literature Annotated Functiona | GO Annotated Molecular Functionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0004391 | shtd | 0.308 | 1.48 E-12 | 4.49 E-10 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; NSCSR; Cell cycle activity | Mitotic anaphase-promoting complex activity |

| FBgn0053123 | CG33123 | 0.195 | 4.65 E-06 | 0.000269 | NSCSR; ribosome associated process | Leucine-tRNA ligase activity |

| FBgn0020306 | dom | 0.15 | 5.82 E-06 | 0.000321 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Helicase activity |

| FBgn0030241 | feo | 0.259 | 0.00042 | 0.0105 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Microtubule binding |

| FBgn0015664 | Dref | 0.178 | 0.00377 | 0.055 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

| FBgn0030500 | Ndc80 | 0.176 | 0.0159 | 0.147 | GSCDIFF; Kinetochore/Spindle | — |

| FBgn0002183 | dre4 | 0.0906 | 0.0192 | 0.167 | Transcription and chromatin remodeling | DNA binding |

| FBgn0085436 | Not1 | 0.135 | 0.0212 | 0.174 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Protein binding |

| FBgn0029672 | CG2875 | 0.187 | 0.0296 | 0.223 | — | — |

| FBgn0260789 | mxc | 0.131 | 0.032 | 0.227 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | DNA binding |

| FBgn0024227 | ial | 0.136 | 0.0381 | 0.254 | GSCEF; NSCCG | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| FBgn0027783 | SMC2 | 0.106 | 0.0386 | 0.254 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | DNA binding |

| FBgn0032728 | Tango6 | −0.304 | 0.0415 | 0.263 | CELLEF | — |

| FBgn0053554 | Nipped-A | 0.154 | 0.0483 | 0.291 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Protein kinase activity |

| Germline stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0011230 | poe | 0.133 | 5.36 E-11 | 1.09 E-08 | GSCEF | Calmodulin binding |

| FBgn0032006 | Pvr | 0.295 | 7.58 E-11 | 1.32 E-08 | — | Protein tyrosine kinase activity |

| FBgn0021761 | Nup154 | 0.341 | 3.09 E-09 | 3.13 E-07 | GSCDIFF; Nuclear pore | Structural constituent of nuclear pore |

| FBgn0028982 | Spt6 | 0.288 | 3.48 E-09 | 3.26 E-07 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Chromatin binding |

| FBgn0021796 | Tor | 0.165 | 2.57 E-06 | 0.000161 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein kinase activity |

| FBgn0262647 | Nup160 | 0.27 | 8.28 E-06 | 0.00042 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Nuclear pore | Protein binding |

| FBgn0261854 | aPKC | 0.447 | 1.35 E-05 | 0.000632 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein kinase C activity |

| FBgn0261954 | east | 0.32 | 1.95 E-05 | 0.000877 | GSCMAINT | — |

| FBgn0001624 | dlg1 | 0.354 | 5.46 E-05 | 0.00189 | — | Guanylate kinase activity |

| FBgn0261797 | Dhc64C | 0.0475 | 5.67 E-05 | 0.00191 | GSCDIFF; Kinetochore/Spindle | ATPase activity, coupled |

| FBgn0082582 | tmod | 0.531 | 0.00015 | 0.00443 | — | Actin binding |

| FBgn0027537 | Nup93-1 | 0.356 | 0.0002 | 0.00566 | — | Structural constituent of nuclear pore |

| FBgn0033762 | ZnT49B | 0.264 | 0.00025 | 0.00673 | GSCMAINT | Cation transmembrane transporter activity |

| FBgn0040273 | Spt5 | 0.143 | 0.00095 | 0.0206 | CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | — |

| FBgn0031119 | CG1812 | 0.277 | 0.00286 | 0.0484 | GSCMAINT | Actin binding |

| FBgn0038805 | TFAM | 0.361 | 0.00298 | 0.0493 | GSCMAINT; Mitochondrial function | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

| FBgn0260936 | scny | 0.243 | 0.00314 | 0.0509 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Ubiquitin-specific protease activity |

| FBgn0039680 | Cap-D2 | 0.125 | 0.0032 | 0.0512 | — | — |

| FBgn0031344 | CG7420 | 0.283 | 0.00414 | 0.0576 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | — |

| FBgn0010382 | CycE | 0.237 | 0.00414 | 0.0576 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Cyclin-dependent protein ser/thr kinase regulator activity |

| FBgn0050020 | CG30020 | 0.223 | 0.00452 | 0.0604 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Nucleic acid binding |

| FBgn0267350 | PI4KIIIalpha | 0.0671 | 0.00604 | 0.073 | — | 1-phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activity |

| FBgn0000158 | bam | 0.373 | 0.00729 | 0.0821 | GSCDIFF; Translation | Translation repressor activity |

| FBgn0011802 | Gem3 | 0.131 | 0.00735 | 0.0821 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Splicing | RNA helicase activity |

| FBgn0039016 | Dcr-1 | 0.0957 | 0.00825 | 0.0887 | Translation | Double-stranded RNA binding |

| FBgn0025815 | Mcm6 | 0.13 | 0.0083 | 0.0887 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF; DNA replication | Chromatin binding |

| FBgn0015245 | Hsp60 | 0.183 | 0.0114 | 0.114 | — | Unfolded protein binding |

| FBgn0002174 | l(2)tid | 0.208 | 0.01294 | 0.124 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Patched binding |

| FBgn0004856 | Bx42 | 0.22 | 0.01781 | 0.158 | GSCEF | Protein binding |

| FBgn0024177 | zpg | 0.2 | 0.02133 | 0.174 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Gap junction channel activity |

| FBgn0053526 | PNUTS | 0.155 | 0.02655 | 0.208 | GSCMAINT | Protein phosphatase regulator activity |

| FBgn0027055 | CSN3 | −0.857 | 0.02722 | 0.211 | GSCEF | — |

| FBgn0041164 | armi | 0.172 | 0.02817 | 0.215 | — | DNA helicase activity |

| FBgn0052113 | CG32113 | 0.0534 | 0.03186 | 0.227 | GSCMAINT | — |

| FBgn0039120 | Nup98-96 | 0.0951 | 0.0359 | 0.242 | Nuclear pore | Protein binding |

| FBgn0003277 | RpII215 | 0.0825 | 0.0385 | 0.254 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | DNA-directed RNA polymerase activity |

| FBgn0025455 | CycT | 0.217 | 0.04489 | 0.274 | GSCEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Protein kinase binding |

| FBgn0033846 | mip120 | 0.142 | 0.04827 | 0.291 | Transcription and chromatin remodeling | DNA binding |

| FBgn0029113 | Uba2 | −0.18 | 0.04833 | 0.291 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Ubiquitin activating enzyme activity |

| FBgn0261938 | mtRNApol | 0.107 | 0.0491 | 0.294 | GSCEF; Mitochondrial function | DNA-directed RNA polymerase activity |

| Neural stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0001612 | Grip91 | 0.443 | 2.75 E-11 | 6.70 E-09 | — | Microtubule binding |

| FBgn0005630 | lola | 0.502 | 1.43 E-10 | 2.17 E-08 | NSCDIFF | Protein binding |

| FBgn0030384 | CG2577 | 0.354 | 2.29 E-05 | 0.00096 | — | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| FBgn0263257 | Cngl | 0.218 | 2.21 E-05 | 0.00096 | — | Intracellular cyclic nucleotide activated cation channel activity |

| FBgn0061200 | Nup153 | 0.282 | 2.58 E-05 | 0.00104 | — | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0250847 | CG14034 | 0.387 | 3.39 E-05 | 0.00133 | — | Phospholipase activity |

| FBgn0264962 | Inr-a | 0.23 | 8.60 E-05 | 0.00275 | — | RNA binding |

| FBgn0041147 | ida | 0.196 | 0.00049 | 0.0116 | NSCSR; Cell cycle activity | Mitotic anaphase-promoting complex activity |

| FBgn0001222 | Hsf | 0.263 | 0.00157 | 0.0314 | — | DNA binding |

| FBgn0037379 | CG10979 | −0.451 | 0.00333 | 0.0516 | — | Metal ion binding |

| FBgn0032683 | kon | 0.113 | 0.00416 | 0.0576 | — | Protein binding |

| FBgn0030706 | CG8909 | 0.0659 | 0.00673 | 0.078 | — | Low-density lipoprotein receptor activity |

| FBgn0040477 | cid | 0.405 | 0.00751 | 0.0831 | — | DNA binding |

| FBgn0003044 | Pcl | 0.188 | 0.00797 | 0.0867 | — | Protein binding |

| FBgn0031886 | Nuf2 | 0.236 | 0.0108 | 0.109 | — | — |

| FBgn0036248 | ssp | 0.281 | 0.0118 | 0.117 | — | Beta-catenin binding |

| FBgn0259876 | Cap-G | 0.18 | 0.0141 | 0.134 | — | — |

| FBgn0030951 | CG6873 | 0.378 | 0.0205 | 0.171 | — | Actin binding |

| FBgn0035026 | Fcp1 | −0.242 | 0.0265 | 0.208 | — | CTD phosphatase activity |

| FBgn0053100 | 4EHP | 0.423 | 0.0307 | 0.226 | — | Translation initiation factor activity |

| FBgn0039475 | CG6277 | 0.219 | 0.0322 | 0.228 | — | Phosphatidylcholine 1-acylhydrolase activity |

| FBgn0039788 | Rpt6R | 0.138 | 0.0329 | 0.231 | — | ATPase activity |

| FBgn0036643 | Syx8 | −0.702 | 0.0346 | 0.241 | — | SNAP receptor activity |

| FBgn0250732 | gfzf | 0.287 | 0.0395 | 0.256 | — | Glutathione transferase activity |

| FBgn0011704 | RnrS | −0.229 | 0.0445 | 0.274 | — | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase activity |

Note.— CELLEF, germline general cell essential factor; GSCEF, germline stem cell-specific essential factor; NSCCG, neural stem cell regulation of cell growth; NSCSR, neural stem cell self-renewal; DoSMAF, DoS statistics calculated after excluding minor allele frequencies of 5%; MK-test FDR P values, MK-test P values after FDR corrections; Note that these were analyzed from all stem cell regulating gene list identified from both Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014) regardless of whether it was assigned a control gene or not from this study. Significant MK test P values after FDR correction are bolded.

aFunctional annotation based on the study of Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014).

bFunctional annotation based on GO categorization on Flybase.

The proportion of amino acid sites fixed from positive selection (α) was estimated using the method of Messer and Petrov (2013). We estimate α values of 0.704 (95% confidence interval: 0.255–0.931) for BSC whereas 0.688 (95% confidence interval: 0.564–0.805) for its control genes, 0.796 (95% confidence interval: 0.656–0.890) for GSC whereas 0.656 (95% confidence interval: 0.583–0.720) for its control genes, and 0.676 (95% confidence interval: 0.397–0.836) for NSC genes whereas 0.674 (95% confidence interval: 0.549–0.800) for its control genes. For each stem cell class and its control genes, the 95% confidence intervals overlapped with each other suggesting no significant differences in α. The 95% confidence intervals for the control genes of each stem cell class encompassed the α from Messer and Petrov (2013) of 0.57 (95% confidence interval: 0.54–0.60) estimated from a whole-genome polymorphism data from a North American population of D. melanogaster (Mackay et al. 2012).

The ω, DoS, and α statistics and the MK test assume synonymous sites are effectively neutral and thus any potential selection on synonymous sites could bias our results and interpretations. However, we did not observe any significant differences in synonymous divergence (dS), FOP, or ENC statistics between the stem cell class genes and their control genes (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online).

Analysis of D. melanogaster Stem Cell Regulating Genes without Random Control Genes

Although we favor our analysis of stem cell class genes relative to sets of matched control genes, the inability to find appropriate control genes resulted in excluding a total of 27 BSC, 69 GSC, and 44 NSC genes from the previous polymorphism and divergence analysis. For completeness, we have separately examined θπ, TajD, FWH, ω, and DoS values for the excluded stem cell genes. Although excluded BSC genes without controls showed lower total CDS θπ (FDR-corrected MWU test P value = 0.048) and excluded GSC genes without controls showed significantly lower synonymous θπ (FDR-corrected MWU test P value = 0.038) compared with the BSC or GSC genes with controls (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online), the TajD, FWH, ω, and DoS values showed no significant difference in any of the three stem cell classes when comparing genes with and without its control genes (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). Thus, results from the previous evolutionary analysis do not appear to have been biased by a loss of power from excluding stem cell genes without the appropriate control genes.

Comparative Genetic Analysis of Stem Cell Regulating Genes in the melanogaster Group

Long-term patterns of molecular evolution were also evaluated for these same groups of stem cell genes across the 13 Drosophila species of the melanogaster group. For some individual genes, clear orthologs could not be assigned in some species and were thus excluded, resulting in a slightly smaller number of genes being analyzed than were for the D. melanogaster polymorphism-based analyses (67 BSC genes, 154 GSC genes, and 88 NSC genes with assigned control genes).

No significant difference in ω (the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous substitutions) was observed between any of the three stem cell classes and their control genes (table 4; see supplementary data S2, Supplementary Material online, for estimates of ω for each gene). We observed no significant difference in dS between the stem cell class genes and their control genes (results not shown) suggesting that there are no class-specific differences in positive or negative selection, based on ω, on amino acid replacements across the analyzed 13 Drosophila species.

Table 4.

Codon Model Based Test of Positive and Purifying Selection across the Three Stem Cell Classes and Their Corresponding Control Genes

| Statistic | Both Stem Cell | Both Stem Cell Control | Germline Stem Cell | Germline Stem Cell Control | Neural Stem Cell | Neural Stem Cell Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAML Model 0 | ||||||

| ω | 0.032 (0.023, 0.041) | 0.036 (0.027, 0.043) | 0.033 (0.026, 0.042) | 0.041 (0.036, 0.045) | 0.03 (0.022, 0.043) | 0.034 (0.030, 0.040) |

| PAML Model 8 | ||||||

| ω+ | 49 (0.096%) | 116 (0.110%) | 109 (0.090%) | 213 (0.084%) | 47 (0.086%) | 113 (0.084%) |

| HYPHY FUBAR | ||||||

| ω+ | 17 (0.033%) | 27 (0.026%) | 36 (0.030%) | 89 (0.035%) | 24 (0.044%) | 51 (0.038%) |

| ω− | 40,688 (80.0%) | 84,593 (80.2%) | 94,762 (78.6%) | 200,475 (79.2%) | 42,157 (77.5%) | 106,005 (79.1%) |

| Total Codons | 50,869 | 105,449 | 120,558 | 253,087 | 54,412 | 134,081 |

Note.—ω, median ratio of nonsynonymous divergence to synonymous divergence with 95% bootstrap confidence interval in parenthesis; ω+, number of sites with significant evidence (posterior probability ≥ 0.9) of positive selection and its proportions are indicated in parenthesis; ω−, number of sites with significant evidence (posterior probability ≥ 0.9) of purifying selection and its proportions are indicated in parenthesis.

We tested for codon-specific positive and negative selection occurring on the amino acid coding sites using the methods M8 of PAML and FUBAR of HYPHY. Results showed that the total number of codons with positive selection (ω+) was lower using HYPHY than using PAML; however, neither method indicated a significant difference in total ω+ between any of the three stem cell classes and their respective control genes (table 4; see supplementary data S2, Supplementary Material online, for full list of genes with results from HYPHY and PAML analysis). Using FUBAR codons estimated to show significant evidence of negative selection (ω < 1) were also compared across all stem cell class genes and their control genes. On average, 79% of the total examined codons were under negative selection for each stem cell class and this proportion was not significantly different from its control genes (table 4).

Examining all stem cell regulating genes regardless of having a control gene assigned, PAML M8 analysis showed 39 of 99 (39.4%) BSC genes, 89 of 244 (36.5%) GSC genes, and 50 of 138 (36.2%) NSC genes with at least one codon with significant evidence (posterior probability > 0.9) of positive selection. The HYPHY FUBAR analysis showed 26 of 99 (26.2%) BSC genes, 55 of 244 (22.5%) GSC genes, and 31 of 138 (22.5%) NSC genes with at least one codon with significant evidence (posterior probability > 0.9) of positive selection. Both PAML Model 8 and HYPHY FUBAR analysis had detected the same codons with significant evidence (posterior probability > 0.9) of positive selection in 10 BSC genes, 27 GSC genes, and 17 NSC genes (see table 5 for complete list of genes that had significant evidence of positive selection after PAML and HYPHY analysis).

Table 5.

List of Stem Cell Regulating Genes with Codons under Positive Selection after PAML Model 8 and HYPHY FUBAR Analysis, Which Detects Evidence of Long-Term Positive Selection along the melanogaster Group

| FBgn Name | Gene Name | Codon Position | PPModel 8 | PPFUBAR | Literature Annotated Functiona | GO Annotated Molecular Functionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0000541 | E(bx) | 899 | 0.916 | 0.912 | Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor binding |

| FBgn0003041 | pbl | 450 | 0.951 | 0.916 | GSCMAINT; NSCCG | Guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity |

| FBgn0003169 | punt | 49 | 0.994 | 0.995 | — | Activin binding |

| FBgn0003346 | RanGAP | 595 | 0.904 | 0.919 | GSCMAINT | Ran GTPase activator activity |

| FBgn0004378 | Klp61F | 863 | 0.903 | 0.968 | — | Motor activity |

| FBgn0016983 | smid | 501 | 0.944 | 0.945 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | ATPase activity |

| FBgn0027587 | CG7028 | 385 | 0.918 | 0.928 | CELLEF | Protein kinase activity |

| FBgn0030241 | feo | 627 | 0.967 | 0.947 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | Microtubule binding |

| FBgn0034528 | CG11180 | 698 | 0.902 | 0.944 | NSCSR; ribosome associated process | Nucleic acid binding |

| FBgn0052183 | Ccn | 315 | 0.971 | 0.928 | GSCDIFF; NSCDIFF | Growth factor activity |

| 345 | 0.947 | 0.933 | ||||

| Germline stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0000392 | cup | 680 | 0.925 | 0.989 | Translation | Protein binding |

| FBgn0003090 | pk | 284 | 0.926 | 0.937 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0003732 | Top2 | 903 | 0.925 | 0.966 | GSCEF | DNA binding |

| 913 | 0.947 | 0.921 | ||||

| 1455 | 0.986 | 0.911 | ||||

| FBgn0004872 | piwi | 75 | 0.914 | 0.944 | — | RNA binding |

| FBgn0005632 | faf | 1199 | 0.978 | 0.918 | — | Ubiquitin-specific protease activity |

| FBgn0015245 | Hsp60 | 494 | 0.962 | 0.992 | — | Unfolded protein binding |

| FBgn0015834 | Trip1 | 3 | 0.934 | 0.913 | GSCMAINT; Translation | Translation initiation factor activity |

| FBgn0021796 | Tor | 1654 | 0.934 | 0.948 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein kinase activity |

| FBgn0023175 | Prosalpha7 | 13 | 0.979 | 0.943 | CELLEF; Proteasome | Endopeptidase activity |

| FBgn0025830 | IntS8 | 132 | 0.952 | 0.92 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF | — |

| FBgn0029840 | raptor | 372 | 0.954 | 0.934 | GSCDIFF; GSCEF | — |

| FBgn0031119 | CG1812 | 23 | 0.945 | 0.93 | GSCMAINT | Actin binding |

| FBgn0031885 | Mnn1 | 607 | 0.958 | 0.932 | CELLEF | — |

| FBgn0033185 | CG1603 | 267 | 0.953 | 0.974 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Metal ion binding |

| FBgn0035437 | CG11526 | 37 | 0.912 | 0.941 | — | — |

| FBgn0035590 | Prpk | 118 | 0.936 | 0.908 | GSCDIFF | Protein tyrosine kinase activity |

| FBgn0039016 | Dcr-1 | 780 | 0.993 | 0.959 | Translation | Double-stranded RNA binding |

| FBgn0050020 | CG30020 | 112 | 0.957 | 0.91 | GSCMAINT; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Nucleic acid binding |

| FBgn0053556 | form3 | 369 | 0.991 | 0.958 | GSCEF | Actin binding |

| FBgn0260934 | par-1 | 480 | 0.982 | 0.931 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF | Protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

| FBgn0260936 | scny | 700 | 0.925 | 0.929 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Ubiquitin-specific protease activity |

| FBgn0261954 | east | 810 | 0.967 | 0.97 | GSCMAINT | — |

| 1516 | 0.927 | 0.921 | ||||

| FBgn0262647 | Nup160 | 710 | 0.919 | 0.903 | GSCMAINT; CELLEF; Nuclear pore | Protein binding |

| FBgn0263102 | psq | 142 | 0.998 | 0.963 | Transcription and | DNA binding |

| 258 | 0.999 | 0.974 | chromatin remodeling | |||

| 262 | 0.992 | 0.952 | ||||

| FBgn0263755 | Su(var)3-9 | 373 | 0.994 | 0.92 | GSCMAINT; GSCEF; Transcription and chromatin remodeling | Chromatin binding |

| FBgn0264495 | gpp | 993 | 0.91 | 0.903 | — | Histone methyltransferase activity (H3-K79 specific) |

| FBgn0266557 | kis | 1974 | 0.969 | 0.903 | — | ATP-dependent helicase activity |

| Neural stem cell | ||||||

| FBgn0000287 | salr | 680 | 0.935 | 0.915 | — | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

| FBgn0004595 | pros | 120 | 0.941 | 0.922 | NSCDIFF | DNA binding |

| FBgn0010328 | woc | 1022 | 0.953 | 0.964 | — | Protein binding |

| 1206 | 0.923 | 0.923 | ||||

| FBgn0020653 | Trxr-1 | 93 | 0.99 | 0.926 | — | Protein homodimerization activity |

| FBgn0025571 | SF1 | 19 | 0.948 | 0.939 | — | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0026722 | drosha | 102 | 0.986 | 0.946 | — | Ribonuclease III activity |

| FBgn0030208 | PPP4R2r | 407 | 0.921 | 0.924 | — | Protein phosphatase regulator activity |

| FBgn0033062 | Ars2 | 449 | 0.929 | 0.951 | — | — |

| 463 | 0.953 | 0.948 | ||||

| 475 | 0.936 | 0.907 | ||||

| FBgn0037379 | CG10979 | 887 | 0.979 | 0.954 | — | Metal ion binding |

| FBgn0038072 | CG6225 | 198 | 0.96 | 0.937 | — | Aminopeptidase activity |

| FBgn0038499 | Brf | 346 | 0.968 | 0.954 | — | Transcription factor binding |

| FBgn0038874 | ETHR | 728 | 0.934 | 0.945 | — | G-protein-coupled peptide receptor activity |

| FBgn0061200 | Nup153 | 658 | 0.914 | 0.94 | — | Zinc ion binding |

| FBgn0250732 | gfzf | 989 | 0.984 | 0.989 | — | Glutathione transferase activity |

| FBgn0259876 | Cap-G | 909 | 0.989 | 0.932 | — | — |

| FBgn0260794 | ctrip | 27 | 0.971 | 0.952 | — | Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor binding |

| FBgn0261793 | Trf2 | 348 | 0.982 | 0.9 | — | Sequence-specific DNA binding transcription factor activity |

Note.—CELLEF, germline general cell essential factor; GSCEF, germline stem cell-specific essential factor; NSCCG, neural stem cell regulation of cell growth; NSCSR, neural stem cell self-renewal. Codon Position, position of the codon that had significant evidence of selection (posterior probability > 0.9) in both PAML Model 8 and HYPHY FUBAR analysis. PPModel 8, posterior probability of the positively selected codon after the BEB method of PAML Model 8. PPFUBAR, posterior probability of the positively selected codon after the HYPHY FUBAR analysis. Note that these were analyzed from all stem cell regulating gene list identified from both Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014) regardless of whether it was assigned a control gene or not from this study.

aFunctional annotation based on the study of Neumüller et al. (2011) and Yan et al. (2014).

bFunctional annotation based on GO categorization on Flybase.

Analysis of Biological and Molecular Functions under Selection in D. melanogaster Stem Cell Regulating Genes

To gain insight into the potential drivers of selection on the GSC and NSC system, we have examined for enrichment of genes with evidence of positive selection in specific molecular and biological functions. Only the D. melanogaster lineage was analyzed as the molecular and biological functions for each stem cell regulating genes have been experimentally determined only in this species.

The GSC class was initially examined based on the categorization of Yan et al. (2014). Two biological functions involved in the GSC were examined: 1) GSC specific essential factors versus general cell essential factors and 2) GSC differentiation versus GSC maintenance genes (see Yan et al. 2014 for further detail).

No significant differences in synonymous TajD, FWH, or DoS values were observed between GSC essential factor genes and their control genes or between general cell essential factor genes and their control genes (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online). However, the general cell essential factor category had a significant excess of genes with evidence of a recent selective sweep (13 of 63 genes; FDR P value = 0.049) based on the SweepFinder results from Pool et al. (2012).

Contrasting GSC maintenance and differentiation genes, we found the GSC maintenance genes had significantly more negative synonymous TajD test statistics compared with their control genes (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online; FDR-corrected MWU test P value = 0.038). However, neither GSC differentiation nor maintenance functions showed an excess of genes with SweepFinder evidence of recent selective sweeps (based on Pool et al. 2012) compared with a random group of genes.

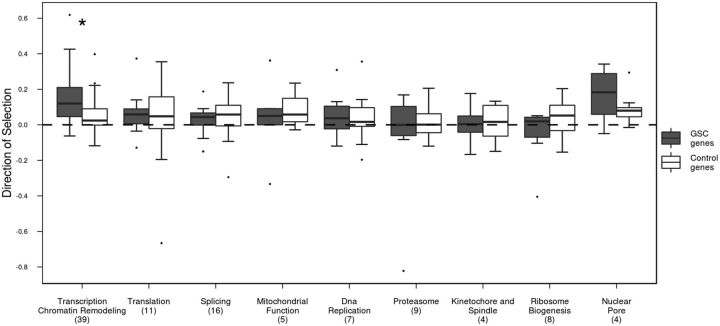

Next, we examined nine molecular complexes/molecular functions within the germline (see fig. 2e of Yan et al. 2014 for further detail). Molecular functions involved in the transcription and chromatin remodeling of the GSC had significantly higher DoS values compared with its control genes (fig. 1; FDR-corrected MWU test P value = 0.0019). However, no significant differences in synonymous TajD or FWH test statistics were observed between genes grouped into any of the nine molecular functions and their control genes (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 1.—

DoS values of various molecular functions within the germline stem cell genes (dark gray) and its control genes (white). Significant difference (P value < 0.05) between stem cell group and its control genes is indicated with a star, whereas numbers in parentheses represent the number of genes examined for each stem cell group.

Finally, we examined the molecular evolution of specific biological and molecular functions in the NSC system. To group NSC genes according to their putative biological functions, Neumüller et al. (2011) used a hierarchical clustering algorithm on a reduced set of NSC regulating genes’ mutant phenotypes, resulting in a cluster of three phenotypic groups: NSC growth, NSC self-renewal, and NSC differentiation (genes listed on supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Data and Supplementary Data, respectively, in Neumüller et al. 2011). As many of the NSC genes’ biological and molecular functions overlapped with each other, only the biological functions involved in the NSC were examined (Neumüller et al. 2011). No significant differences in synonymous TajD or FWH tests and DoS statistics were observed between genes involved in the NSC growth, NSC self-renewal, or NSC differentiation compared with its respective controls genes (supplementary fig. S5, Supplementary Material online). However, we caution further interpretations as the sample sizes for each category were too low resulting in reduced power to detect any potential significant differences.

Discussion

Based on its biological function and importance, stem cell regulatory genes might be expected to be under evolutionary constraint and evolve slower than most other nonstem cell regulatory genes. However, evidence from several previous population genetic studies targeting a few GSC regulating genes (Civetta et al. 2006; Bauer DuMont et al. 2007; Choi and Aquadro 2014; Flores, Bubnell, et al. 2015) suggests the contrary, and compared with the genomic background the stem cell system may in fact have an increased number of genes that are adaptively evolving. Here, to elucidate the evolution of stem cell regulating genes we have examined the molecular evolution of a large set of genes that have functional evidence regulating the Drosophila germline and neural stem cell.

We find evidence that recent selective sweeps were enriched in both GSC and NGS regulatory genes, but not long-term and recurrent positive selection. These results for NSCs were consistent with Pool et al. (2012) who also found an excess of genes with selective sweeps associated with GO terms relating to neurogenesis in the Rwanda D. melanogaster population. We note that the Rwanda population has higher proportions of cosmopolitan admixture compared with the Zambia population that was analyzed in this study (Pool et al. 2012; Lack et al. 2015). Thus, it is possible that the genome-wide selective sweep analysis conducted by Pool et al. (2012) was affected by the cosmopolitan admixture. At least in human populations, recent admixture does not increase the false positive rate of detecting selective sweeps using site frequency-based neutrality tests (Lohmueller et al. 2011). Thus, our results corroborate those of Pool et al. (2012) suggesting that both GSC and NSC have an excess of genes with evidence of recent selection.

On the other hand, none of the three stem cell classes (BSC, GSC, and NSC) showed an elevation, relative to their respective control genes, of long-term recurrent positive selection based on DoS or ω estimates, MK tests, or PAML and HYPHY analyses. Thus, despite the evidence of recent and long-term positive selection in individual genes of the BSC, GSC, and NSC system, there was no evidence to support the hypothesis that the functional role involving stem cells has led to a class-wide enrichment for positively selected genes.

Our results may seem to contradict the findings of Langley et al. (2012) who had conducted genome-wide-polarized MK tests in an African population of D. melanogaster. Their results have shown that genes with significant polarized MK test were enriched for GO categories involved in stem cell maintenance and neural and neural muscular development (see table 11 of Langley et al. 2012). We conducted GO enrichment analysis (from the GO website: http://geneontology.org/, last accessed November 2015) on our set of genes with significant MK test result (table 3) and found significant enrichment for categories such as “germarium-derived female germ-line cyst formation,” “cystoblast division,” and “female germ-line cyst formation” for the GSC genes; and “neurogenesis” for the NSC genes. Thus, our results are consistent with Langley et al. (2012) where among the genes with significant MK test, there are enrichment for specific biological functions relating to germline and neural stem cell functions. However, unlike biological systems such as the immunity where majority of its composing genes have an elevated level of adaptive evolution (Obbard et al. 2009), positive selection in both GSC and NSC is only limited to a subset of genes.

Although neither stem cell system had evidence for an enrichment of genes with long-term adaptive evolution, we also did not find any evidence that the germline and neural stem cell system had a deficit of adaptive evolution. Thus, the unique biological function of stem cells does not seem to cause an overall constraint on the evolution of genes directly involved in regulating the germline and neural stem cell systems. It will of course be important to examine these trends in additional populations of D. melanogaster, as well as populations of species in other lineages across the genus as high quality data become available. Newly available data sets (Rogers et al. 2014; Garrigan et al. 2015; Grenier et al. 2015) are promising however, are limited in their SNP calls due to low sequencing coverage and/or residual heterozygosity.

Using population genetic tests that detect recent (SweepFinder), recurrent (MK test), and long-term (HYPHY and PAML) positive selection there were four genes that had evidence of positive selection across all temporal scale: In the GSC regulating genes: Tor (FBgn0021796), scny (FBgn0260936), and Nup160 (FBgn0262647); and in the NSC regulating genes: Nup153 (FBgn0061200). Multiple signatures of positive selection suggests that these genes are consistent targets of adaptive evolution in Drosophila and will be further discussed below.

Molecular evolution of Tor (Target of Rapamycin) is consistent with previous study that had also identified it under recurrent adaptive evolution in D. melanogaster (Alvarez-Ponce et al. 2012). Functionally Tor is part of the insulin/TOR signal transduction pathway that is commonly involved in various physiological processes, such as metabolism, reproduction, and growth (Oldham and Hafen 2003). Previous studies have identified multiple genes comprising the insulin/TOR pathway under positive selection in both invertebrate and vertebrate lineages (Alvarez-Ponce et al. 2009, 2012; Luisi et al. 2012; McGaugh et al. 2015), suggesting that the genes of the insulin/TOR pathway are strong targets of positive selection in a wide group of organisms. The driver of selection of Tor in Drosophila is unknown, but potentially due to its role in energy metabolism and fecundity Tor had evidence of positive selection across multiple evolutionary time scale in our study. During the wide geographical expansion of the genus Drosophila, subsequent use of the diverse resources in those novel environments (Markow and O’Grady 2008) could have been the primary driver of positive selection for Tor across a wide evolutionary time scale.

Our molecular evolutionary analysis of specific biological functions within the GSC provides limited insight into the possible drivers of selection. However within the GSC, molecular functions relating to transcription/chromatin remodeling was the only category that had increased recurrent adaptive evolution compared with a random group of genes. We note that some of the functional categories had very small sample sizes (fig. 1) resulting in lower power to determine the degree of adaptive evolution. Nevertheless in Drosophila, genes involved in transcription and chromatin remodeling were previously identified as targets of rapid evolution (Vermaak et al. 2005; Rodriguez et al. 2007; Levine and Begun 2008). The gene scny, which had evidence of positive selection across all evolutionary time scale in this study, also has a role in transcription and chromatin remodeling as it encodes an ubiquitin specific protease, and regulates the ubiquitylation of histones during the chromatin remodeling stages (Buszczak et al. 2009). The rapid evolution observed in genes regulating transcription and chromatin remodeling is hypothesized to be due to conflicts between transposable elements and its host (Lee and Langley 2012). Due to its replicative mode of transmission, transposable elements can cause deleterious mutagenic effects across the host genome (Finnegan 1992). Here, a coevolutionary arms race is predicted to occur within the host involving the suppression of these transposable elements from transmitting, while the elements themselves evolving rapidly to evade the host defense (Kidwell and Lisch 2001). Thus, transposable elements could be a major driver of adaptive evolution across some of the GSC regulating genes.

Nup153 and Nup160 are part of the nuclear pore complex surrounding the nuclear membrane and mediates the import and export of molecules being transported to the nucleus (Tran and Wente 2006). Components of the nuclear pore complex were under rapid adaptive evolution in Drosophila (Presgraves et al. 2003; Presgraves and Stephan 2007; Mensch et al. 2013) potentially due to its role in hybrid incompatibility, that is, sterility or inviability observed in a hybrid of two diverged species (Tang and Presgraves 2009). Previously many hybrid incompatibility genes were found rapidly evolving (Ting et al. 1998; Brideau et al. 2006; Maheshwari et al. 2008) likely from genetic conflicts between host and transposable elements, meiotic drivers, and cytoplasmic–nuclear conflicts (Maheshwari and Barbash 2011).

Evolutionary conflict could also occur between germline parasites, such as Wolbachia and Spiroplasma; and their insect host GSCs (e.g., Bauer DuMont et al. 2007; Engelstädter and Hurst 2009; Choi and Aquadro 2014; Flores, Bubnell, et al. 2015; Flores, DuMont, et al. 2015). These maternally inherited microbes have a selfish interest for their own transmission and can manipulate the host reproduction (Werren et al. 2008). One model of manipulation proposes that in the host GSC, the germline parasite could eliminate uninfected germ cells and effectively favor the transmission of infected GSCs (Werren 2005). The elevation of recent selective sweeps that we have observed in GSC regulating genes could reflect the host resisting this manipulation and ultimately promoting the generation of uninfected gametes. Given that phylogenetic studies of Wolbachia have suggested turnovers of Wolbachia infections among its host arthropods (e.g., Baldo et al. 2006), transient infections and resulting transient evolutionary conflict could result in bursts of recent selective sweeps in hosts such as that observed across the D. melanogaster GSC regulating genes. However, this would not lead to excess of recurrent adaptive evolution on GSC genes as a class. Transient positive selection could also result from the fact that Wolbachia infection can provide positive reproductive benefits to its host Drosophila (e.g., Starr and Cline 2002; Teixeira et al. 2008; Flores, DuMont, et al. 2015), and Carrington et al. (2011) have reported a decreased intensity of reproductive manipulation evolving after a decade in a Wolbachia strain infecting D. simulans. Thus even with a persistent Wolbachia infection the coevolutionary arms race could be short, leading only to transient positive selection acting on the GSC regulating genes as appears to be the case for bag of marbles (bam) in Drosophila (Civetta et al. 2006; Bauer DuMont et al. 2007; Choi and Aquadro 2014).

The driver of selection across the NSC genes showing recent selective sweeps or long-term positive selection is unknown. A previous study of the D. melanogaster nervous system has shown frequent emergence of new genes being expressed in the neural tissues. Many of these were under strong positive selection where the possible evolutionary driver was proposed to be its role in regulating foraging behavior (Chen et al. 2012). NSCs will differentiate into the neurons and glia cells of the D. melanogaster nervous system ultimately giving rise to all the cells existing in the adult D. melanogaster brain (Doe 2008). Here, it is possible that cellular regulation of neural differentiation associated with behavior could be driving the evolution of some of the NSC regulating genes.

Finally, the BSC class of genes expressed in both GSC and NSC was the only group showing no evidence of excess positive selection in either short- or long-term evolutionary time scales. This is potentially due to the pleiotropic nature of the BSC class as genes involved in multiple functions of a pathway have previously shown to be under more constraint (Jeong et al. 2001; Fraser et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2007; Greenberg et al. 2008). Still, however, there were individual genes of the BSC system that had evidence of positive selection in various evolutionary time scales. A possible driver of selection here is the competition stem cells have with each other for the niche environment (Li and Xie 2005). In many biological systems, cells are under constant competition with each other. Specifically within the stem cell system, the “winner” stem cell that displaces the “loser” stem cell would differentiate and give rise to the entire adult organism (Johnston 2009). In the Drosophila gonad, studies have shown that stem cells from both somatic and germline tissues are able to compete with each other to occupy their respective stem cell niche (Nystul and Spradling 2007; Jin et al. 2008). These “selfish” behaviors of stem cells could cause conflicts leading to antagonistic results to the overall organism (Werren 2011). Thus as BSC regulating genes are involved in germline, neural, and possibly other systems as well, at least some of the individual genes that are rapidly evolving in this class could be a result from the evolutionary conflict during the stem cell niche competition.

Conclusion

In this study, we have examined the molecular evolution of more than 500 genes that have functional evidence in the regulation of the Drosophila germline and/or neural stem cell. We found an enrichment of genes with evidence of recent selective sweeps in each germline and neural systems. However, there was no evidence to support the hypothesis that germline and neural stem cell regulatory genes are increased targets of recurrent and long-term positive selection. We have also identified and listed the individual genes within the germline and neural system that had evidence of positive selection across various temporal scales. Further analysis suggests that the rapid adaptive evolution of some stem cell regulatory genes is consistent with various genetic conflicts between and within the stem cell.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grant number R01GM095793 to C.F.A. and Daniel A. Barbash, and by the Cornell Center for Comparative and Population Genomics (3CPG) with a 3CPG Scholar Award to J.Y.C. The authors thank Vanessa L. Bauer DuMont, Daniel Barbash, Jaclyn Bubnell, Angela Early, Brian Lazzaro, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful discussions and comments.

Literature Cited

- Akashi H. 1995. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at “silent” sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics 139:1067–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Ponce D, Aguadé M, Rozas J. 2009. Network-level molecular evolutionary analysis of the insulin/TOR signal transduction pathway across 12 Drosophila genomes. Genome Res. 19:234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Ponce D, et al. 2012. Molecular population genetics of the insulin/TOR signal transduction pathway: a network-level analysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Biol Evol. 29:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguello JR, et al. 2010. Recombination yet inefficient selection along the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup’s fourth chromosome. Mol Biol Evol. 27:848–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo L, et al. 2006. Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 72:7098–7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmina O, Kopp A. 2007. Sex-specific expression of a HOX gene associated with rapid morphological evolution. Dev Biol. 311:277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DuMont VL, Flores HA, Wright MH, Aquadro CF. 2007. Recurrent positive selection at bgcn, a key determinant of germ line differentiation, does not appear to be driven by simple coevolution with its partner protein bam. Mol Biol Evol. 24:182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]