Abstract

Background

In Denmark, the treatment of COPD is mainly managed by general practitioners (GPs). Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is available to patients with COPD in the local community by GP referral, but in practice, many patients do not participate in rehabilitation. The aim of our study was to explore 1) GPs’ perceptions of their role and responsibility in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD, and 2) GPs’ perceptions of how patients manage their COPD.

Methods

The study was based on a qualitative design with semi-structured key-informant interviews with GPs. Investigator triangulation was applied during data generation, and analysis was done using thematic analysis methodology.

Results

Our main findings were that GPs relied on patients themselves to take the initiative to make clinic appointments and on professionals at health centers to provide the PR including consultations on lifestyle changes. The GPs experienced that patients chose to come to the clinic when they were in distress and that patients either declined or had poor adherence to rehabilitation when offered. The GPs were relieved that the health centers had taken over the responsibility of rehabilitation as GPs lacked the resources to discuss rehabilitation and follow up on individual plans.

Conclusion

Our study suggested a potential self-reinforcing problem with the treatment of COPD being mainly focused on medication rather than on PR. Neither GPs nor patients used a proactive approach. Further, GPs were not fully committed to discuss non-pharmacological treatment and perceived the patients as unmotivated for PR. As such, there is a need for optimizing non-pharmacological treatment of COPD and in particular the referral process to PR.

Keywords: non-pharmacological treatment, motivation theory, primary care, treatment approach, pulmonary rehabilitation, qualitative research

Video abstract

Introduction

COPD is an incurable disease representing a major health problem. The incidence has increased over the years, and COPD is today the fourth highest cause of death in the world.1,2 Smoking cessation can delay further disease, and both medical treatment and physical activity can reduce symptoms.1,3 Rehabilitation programs, with physical activity, patient education, and smoking cessation as treatment elements, have proven to be important for 1) reducing breathlessness, 2) improving exercise capacity, and 3) health-related quality of life. Moreover, rehabilitation programs 4) promote a more speedy recovery from hospitalization in case of exacerbation and 5) reduces the frequency of hospitalizations and days in hospital in the event of an exacerbation. Other benefits of rehabilitation programs are related to relieving anxiety and depression associated with COPD.1

One of the main pillars of COPD management is effective pharmacological treatment, providing symptom relief, and reducing the rate of exacerbations and hospitalizations.4 In Denmark, there has been a substantial improvement in quality of COPD management in the last 25 years. Before 1990, many patients in the general practice were often not diagnosed with COPD but were treated based on their symptoms without the use of spirometry. In 1998, the Danish Lung Association introduced the first national guidelines on management of COPD. After the publication of the first Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease document in 2001, COPD gradually became a focus area for the Danish Health Authorities, and several national treatment guidelines have been published in recent years.5 In Denmark, most health care services are financed through income tax. Medications are usually paid for by the patients.

The treatment of COPD is mainly managed by general practitioners (GPs),6,7 who play an important role as frontline care workers. Danish GPs are able to offer pharmacological treatment and refer the patients to pulmonary rehabilitation (PR).5,8 Moreover, it is recommended that the GPs monitor patients with COPD routinely, at least once a year.9–11 GPs are responsible for patient motivation and follow-up, evaluation of goal fulfillment, and for adjusting or terminating the effort.8 The change from conventional treatment and symptom management to a more systematic primary care approach with potential reduction of hospitalization and mortality is supported in the literature.12

However, studies from Australia and the US show that GPs are challenged in their treatment of patients with COPD with regard to several aspects.13–17 One problem is that patients with COPD often have comorbidities13,14 and that COPD tends to get outweighed by these coexisting diseases by both patients and doctors.14 Other problems include delayed medical treatment15 and low referral rate to PR.16

It is of interest to explore the identified challenges within the context of a comprehensive welfare system. COPD has been a target area for the Danish Health Authorities, and it may be assumed that easy access to health services, in particular to PR, would prompt GPs to more patient referrals. The aim of our study was to explore 1) GPs’ perceptions of their role and responsibility in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD, and 2) GPs’ perceptions of how patients manage their COPD.

Methods

The study had a descriptive qualitative design to explore key-informant interviews with Danish GPs. Data were generated during January–April 2014.

Ethics

The study complied with ethical principles for medical research as described in the Declaration of Helsinki.18 As the interviews did not include personal data, the study did not require approval but was reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal number 2013-41-2536) and the National Committee on Health Research Ethics (protocol number H-6-2013-009). The GPs were informed of the study verbally and in writing, and verbal consent was obtained. The informants were informed that the interviews would be audio-recorded and that all identifying information would be deleted from the transcripts.

Participants

We used strategic sampling with a purpose of achieving maximum variation among the informants. This included GPs in solo practice, in a medical center, in a low-income area, and in a middle- to high-income area, GPs with varying years of experience, GPs with expert knowledge on patients with respiratory diseases, and finally male and female GPs. The informants were recruited through physician networks and educational programs for new graduates and consultants on improving conditions for working in the primary health sector. The recruitment process ended when data saturation was obtained.19

Data generation

All semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (KRM), while the third author (LSV) acted as observer. The interview guide focused on the following themes: GPs’ treatment of patients with COPD, patients’ reason for contact, and patients’ disease management (Table 1). The interview guide was pilot-tested and revised before and through the study.

Table 1.

Interview guide

| Themes | Examples of questions |

|---|---|

| GPs’ treatment of patients with COPD | Do you have a general treatment program for patients with COPD other than patients’ complaints? |

| Patients’ reason for contact | What are the needs of patients with COPD? |

| Patients’ disease management | What are the barriers for patients with COPD for following treatment recommendations? |

Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners.

Key-informant interviews provide firsthand knowledge of a community, as inside experts are able to describe their problems and give recommendations for solutions.19 The interviews were audio-recorded, and field notes were taken by the investigators immediately after each interview. The interviews were transcribed using the software Express Scribe Pro version 5.63 (NCH Software, Inc., Canberra, Australia).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using thematic analysis in six phases as described by Braun and Clarke:20 1) The interviews were transcribed and validated by two investigators by listening to the voice recordings while reading the transcripts to ensure accuracy. 2) Initial deductive and inductive coding was performed by vertical analysis of the entire dataset. 3) The codes were reread and combined into themes. 4) The themes were checked with the coded extracts and data corpus (hermeneutical circle). 5) Themes were finally defined. 6) We used direct quotes for documentation and illustration of each theme. When more specific questions were asked, a semantic approach was chosen for a detailed and nuanced account of particular themes within the data. The analytic process consisted of a descriptive phase, where data were organized and patterns emerged, and an interpretation phase, with a possibility to theorize. The analysis was conducted using the software NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

Results

Informant characteristics

We interviewed eight GPs in the study. Seven worked in solo practice and one in a medical center. Four of the practitioners in solo practice worked in a semi-solo clinic in collaboration with other GPs but each with their own patients (Table 2). Two informants worked at the same clinic with low-income patients in whom COPD was highly prevalent.

Table 2.

Informant characteristics

| GP ID number | Sex | Experience (years) | Type of practice | Secretary | Nurse | Laboratory technician | Midwife | Resident | Medical student |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 1 | SS | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | Female | 2 | SS | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 3 | Male | 3 | SS | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| 4 | Female | 11 | S | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| 5 | Male | 11 | SS | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| 6 | Male | 17 | S | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| 7 | Male | 24 | M | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Female | 25 | S | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

Abbreviations: GP, general practitioner; SS, semi-solo practice in collaboration with other GPs; S, solo practice; M, medical center.

Themes and subthemes

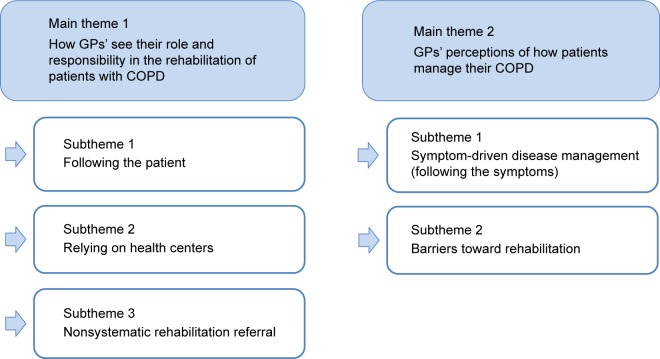

The two main themes refer to the aim of the study: 1) how GPs see their role and responsibility in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD, and 2) GPs’ perceptions of how patients manage their COPD. The subthemes that emerged in the first theme were 1) following the patient, 2) relying on health centers, and 3) nonsystematic rehabilitation referral. The subthemes in the second theme were 1) symptom-driven disease management (following the symptoms) and 2) barriers toward rehabilitation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main themes and subthemes.

Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners.

Figure 1 illustrates the two main themes and the related subthemes.

Theme: how GPs see their role and responsibility in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD

Subtheme: following the patient

The GPs focused on the current problems presented by the patients, rather than tapping into the patients’ general knowledge of COPD and suggesting a full rehabilitation program with lifestyle changes including physical activity. Patients were assumed to be in good health if they did not bring up other treatment needs. GPs did not actively discuss these matters if not brought up by the patients. One GP said:

If the patient doesn’t mention any distress or ask for anything specific, I assume that everything is fine. [GP 1]

The GPs did not actively use a protocol for COPD treatment, and annual check-ups were not planned ahead. One GP said:

It’s up to the patients; I usually say: “So, you’ll be back again in 6 to 12 months” – which they seldom do. We lack a system that is organized so we can make structured follow-up on each patient. I should probably have one, but I don’t. [GP 6]

One GP differed from the other informants by stressing that patients with COPD require frequent follow-up, and should have higher priority than patients with other chronic conditions (eg, diabetes) arguing that patients with COPD are more affected in their daily lives. The GP acknowledged the complexity of the illness and explained that his COPD consultations focused on the psychosocial aspects and supported the patients in activities of daily living as many of the patients had symptoms of depression. He explained:

The patients endure long periods of illness and perseverance. The problem can be medication compliance, physical activity and lifestyle. Often I think they have a depression – they are sad. There are many reasons; their living situation, their family and all the things that don’t work because they are actually very ill. [GP 7]

The same practitioner specialized in respiratory diseases. He believed that consultations were important for patients with COPD because of an often complex life situation. The other GPs believed that they were unable to do much for the patients and were primarily focused on medications. Although, attention regarding the social aspects of COPD, including social problems, was present with all the GPs, where most of the GPs assumed that the social problems would explain the lack of patient resources to manage their disease. Based on these assumptions, the GPs failed to prod or motivate the patients toward a healthier lifestyle.

Subtheme: relying on health centers

In general, the GPs found it pointless to discuss non-pharmacological treatment options and lifestyle changes with the patients. Instead, they described that the municipal PR at the health centers was responsible for handling these issues. They assumed that PR was offered to the patients elsewhere and expressed relief that this option was available. One GP stated:

For once, some of my work is taken off my shoulders. Instead of me telling the patients about physical activity, and demonstrating exercises and such, there are other people [health care professionals] who are much better doing it than me. […] I clearly don’t want to deal with this. [GP 3]

Another GP explained:

I can feel that I have become a bit lazy, because I, myself, don’t take care of it because of these other options [health centers]. […] However, it would typically be something I would give higher priority, or have a nurse that could inform the patients, if they [health centers] didn’t exist. [GP 5]

The interviews revealed that the GPs agreed that consultations focusing on lifestyle were important. Yet, they chose not to spend time addressing these issues because they found that the patients have already been referred to the health centers. One GP thought that the patients were only offered a single PR program and that this was inadequate. She said:

[…] but the municipal center has only a limited offer [of PR] and the patients get only one chance; many patients would like to participate again, but this is not possible. [GP 2]

Another GP believed that when patients had followed PR once and had quit smoking, they should not be offered a second rehabilitation program as the resources should be reserved for “new” patients. He underlined this by describing one of his patients:

[…] probably she will have more exacerbations over time […] she will be admitted to the hospital a couple of times a year maybe and this direction will probably continue. […] she is in some sort of limbo where she has followed a rehabilitation program with patient education, and she has quit smoking. I think… Let’s use the resources on someone else who has not quit smoking or who doesn’t know the recommendations. [GP 5]

Subtheme: nonsystematic rehabilitation referral

Two GPs in our study stated that they did not inform their patients with COPD of the possibility of participating in PR. They believed that their patients in general were unable or unmotivated to follow such a program. The distance to the health centers was seen as a barrier. One of the GPs stated:

They [patients] don’t want to [follow rehabilitation] and the distance to the center is too far and difficult. […] I think there have been one or two [patients] who appreciated the physical activity, but it is my impression that they don’t want to go. […] They don’t understand the good, obvious advice. [GP 4]

Another reason to defer PR referral was the perception that the patients were too depressed to engage in rehabilitation. A GP said:

Some of the patients with COPD are depressed. […] For patients to participate they need more energy. So I think that most of the patients with COPD […] are not able to attend PR at the health center. [GP 7]

Frequent home visits were suggested as an alternative to rehabilitation programs at the health centers. The GP explained:

In a perfect world you would have more time to visit them in their homes. […] Either myself or another health care professional, nurses […] someone with special knowledge on this matter. Maybe a visit once a month to get insight in “how is it going” and to help them remember and follow up on their illness. […] To keep them motivated. [GP 5]

The GPs who did inform their patients of non-pharmacological treatment believed that the health care professionals at the health centers had more success with lifestyle changes because the conditions for helping the patients were better. One GP explained:

They [health center] may have more time to talk and inform about these matters than I have here in my practice. So I have the impression that the patients are very pleased with PR and I believe that it is a very good supplement to general practice that they [health center] can take action on the aspects regarding physical activity, diet and smoking and so forth. [GP 1]

Another GP said:

I think that it works very well with the health centers. I think it is good that so many services are in one place. […] We have us [the GPs] here and then the health centers with other services such as smoking cessation, physical activity and diet. [GP 2]

In summary, the main focus of GP consultations was on the medical treatment. GPs displayed a reactive treatment approach to COPD and lacked procedures for annual check-ups. The GPs assumed that it was unnecessary for them to discuss and provide non-pharmacological advice for their patients with COPD because this was provided elsewhere.

Theme: GPs’ perceptions of how patients manage their COPD

Subtheme: symptom-driven disease management (following the symptoms)

Most of the GPs perceived that patients with COPD rarely made an appointment unless they were experiencing illness exacerbations. One GP stated that only very few patients made an appointment for medication adjustment and annual check-ups. She said:

A few patients consult me because they feel that the medicine no longer helps them sufficiently. Then we have a talk about this and try to find a way for it to work. Apart from this they [patients] usually come because they have first signs of an exacerbation. [GP 8]

Another GP explained it this way:

[…] they [patients] only show up during exacerbations and when they need medications. Apart from this I don’t hear from them. […] They are not very interested in getting their lung function measured “It was measured a few years ago” and that is fine with them. […] So they live a life where it is not that common to bother a doctor. [GP 1]

The GPs indicated that patients with COPD had a symptom-driven approach to the management of their disease and that they only consulted their GP when they needed help during exacerbations. A GP reflected on why the patients failed to make an appointment without experiencing an exacerbation:

It is a puzzle to me and I don’t understand why they don’t come and see me. […] But maybe… it feels like a resignation because you cannot really do anything. […] We can hardly make them better because no matter what we do, their lung function will decrease. And that means they will need more and more medicine. I think people experience that the things we do don’t help them that much. [GP 6]

The GPs had the impression that the patients only came to the clinic when they were desperate. Otherwise, the patients coped with their disease on their own because they failed to see that the GPs could play a role in handling their disease and the challenges that the disease resulted in. GPs as well as patients had a dim view of COPD management and rehabilitation in relation to prevention of disease progression and improving functional capacity and everyday life.

Subtheme: barriers to rehabilitation

Most of the GPs perceived that the patients were unmotivated toward PR. Some patients were willing to participate at the time of referral but failed to engage in PR because of lack of energy or because of a long distance to the health center. The greatest barrier is to get the patients to initiate PR. Once the patients get started and begin to feel better, they are willing to stay on the program, and some even enjoy it. One GP explained:

[…] I mention the possibility of following PR to the ones I believe can profit from this at all. But most of them say “I will think about it” and then nothing else happens. [GP 6]

Another GP said:

There are many who fail to attend because they lack the strength to do it […] they say “yes” but then they don’t show up anyway […] maybe the explanation is the distance. Or maybe they do not think they benefit enough from it. [GP 7]

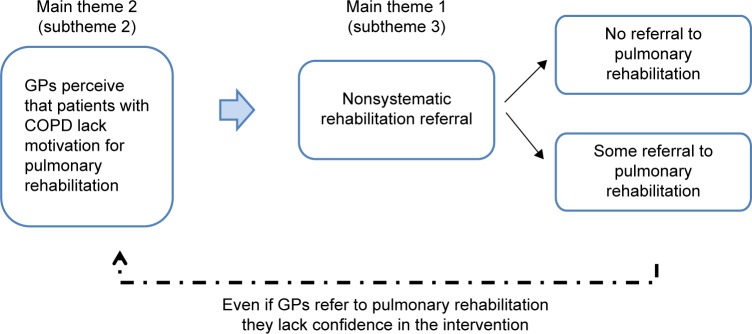

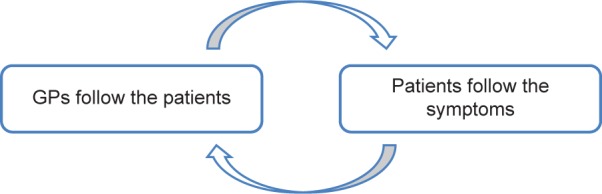

In summary, the GPs experienced that their patients with COPD rarely made appointments at the clinic unless they were experiencing exacerbations. The GPs perceived that the patients failed to take responsibility for their disease and assumed that they were unmotivated for PR. GPs did not see themselves having an active role in suggesting PR when not required by the patients. For this reason, the GPs failed to refer patients with COPD to PR. This appeared to be a vicious cycle in the treatment of COPD, as illustrated in Figure 2. GPs had a reactive treatment strategy (follow the patients), and the patients had a reactive management of their COPD (follow the symptoms). Figure 3 illustrates the potential dynamics of PR referral.

Figure 2.

Vicious cycle in COPD treatment.

Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners.

Figure 3.

Dynamics of pulmonary rehabilitation referral.

Abbreviation: GPs, general practitioners.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to explore 1) GPs’ perceptions of their role and responsibility in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD, and 2) GPs’ perceptions of how patients manage their COPD. The subthemes emerged inductively and included following the patient, relying on health centers, non-systematic rehabilitation referral, symptom-driven disease management, and barriers toward rehabilitation. Our main findings were that GPs relied on patients to make appointments when the patients felt that they needed it, and that the responsibility for non-pharmacological solutions such as PR was on the health centers. GPs offered mainly medical treatment leaving non-pharmacological treatment and training up to the patients and health centers. In essence, the GPs had a reactive approach toward the treatment of patients with COPD which is not in line with the clinical guidelines on proactive treatment options.

The approach to COPD treatment described in this study might lead to a vicious cycle, where GPs fail to refer patients to PR assuming that the patients are unwilling. Further, the patients may fail to comply with PR because the GPs fail to endorse it.

This reactive approach leads to suboptimal treatment of patients with COPD. Our findings are important because the evidence documented that PR together with correct medications has a positive effect on patients’ symptoms and quality of life.1 A proactive strategy is further supported in a study by Einarsdóttir et al,12 where they found that a more frequent contact with GPs protects the patients with COPD against hospital admissions and mortality. Moreover, it is recommended that a date is set for a future appointment when patients are visiting the GP. Alternatively, the GP should on an annual basis remind the patient that it is time to make an appointment.8

The subthemes in our study suggest that patients are unmotivated for PR and that GPs refer patients unsystematically showing that the GPs act on their assumptions rather than on evidence. This pattern is an obstacle in facilitating a sustainable treatment for patients with COPD. It is crucial that the patient participate in PR for succeeding in a more proactive management to avoid systemic consequences of the disease including muscle atrophy.1,2 Accordingly, it could be argued that the vicious cycle could be broken if GPs chose a more proactive approach, and took the responsibility to inform the patients and support them in becoming motivated.8 Yet, in order for this to happen, it is important to fully understand why patients are perceived as unmotivated toward PR. Consequently, our understanding of the underlying incentives of the individuals relies crucially on a better understanding of the patients’ perception of COPD treatment and management. This needs to be addressed and investigated further to develop solutions that can break this present pattern.

The fact that some GPs did not offer PR to their patients with COPD is in contrast to both the national and the international clinical guidelines, and is a known challenge in the literature.8,16,17 Hence, all patients should be made aware of the benefits of PR, and in a Danish context, of the option to be referred to PR in the municipalities.11 However, the patients are dependent on each GP’s approach because the GPs, as the patients’ gatekeepers, are not legally obliged to consider and prescribe PR.8 Within the publicly financed Danish health care system, the GP has only 10 minutes per consultation to assess the patient and promote lifestyle changes. This might explain some of the views by GPs found in our study.

This discussion leaves the question of why patients lack motivation. The information–motivation–behavioral skills model by Fischer et al21 can help us understand why people fail to initiate, persist, and terminate their involvement in health-related activities such as PR. This theory focuses on three dimensions, health-related information, motivation, and behavioral skills, which are fundamental determinants of behavioral change. The effects of the information and motivation part are seen primarily as a result of behavioral skills which can lead to initiation and maintenance of behavioral change. Patients with COPD do not seem to have the required behavioral skills to have a proactive management strategy. Therefore, it is important to consider the two main determinants: information and motivation. Regarding information part, one study finds that the patients have “expert” knowledge, and that they know what to do in the case of exacerbations.22 Other studies, however, show that the patients do want more information about COPD early in the process, preferably at the time of diagnosis,23 and that patients with moderate COPD lack knowledge of the disease.14,24–26 Because COPD is a progressive disease, the need for information and behavior change counseling can vary over time. Thus, it can be problematic when GPs fail to discuss non-pharmacological treatment with their patients over time or only refer them to PR once. What is needed, regarding patients with COPD, is to investigate their level of information, motivation, behavioral skill deficits and assets, and their level of health promotion or health risk behavior.

Motivation, as the other determinant, can be presented as a continuum from amotivation to extrinsic motivation and on to intrinsic motivation described in the self-determination theory developed by Ryan and Deci.27 Extrinsic motivation relies on input from the outside, whereas intrinsic motivation is driven by the person’s own enjoyment or interest.

According to the interviews with the GPs, the GPs assume that patients with COPD are predominantly extrinsically motivated or even amotivated. As the patients’ gatekeepers to the health care system, the GPs have an important role in guiding the patients and in facilitating the patients’ motivation toward rehabilitation. However, that is also a key to the problem because according to our findings, the GPs are not fully committed to introduce rehabilitation. Due to the assumed division of labor between the GP clinics and the health care centers, some GPs fail to do their part. This could potentially affect the patients and increase expenses to society.

Another possible way to address the patients’ possible lack of motivation could be to increase the number of local facilities as suggested by GPs in this study. This would increase the incentive for initiation and sustainment of rehabilitation in patients who are challenged by comorbidity and disease severity. Local facilities are identified in the literature as a determining factor for the success of PR.11

Traditionally COPD rehabilitation has focused on the most severe cases of the disease in a hospital setting.28–30 Going forward, it would be beneficiary to further investigate rehabilitation in a more timely fashion to include patients earlier in their disease. This would enable more sustainable rehabilitation and support changes in habits and lifestyle. In that way, we might reduce the speed of the progression of the disease, which is in the interest of the individual and society.

Methodological reflections of the study

The transferability (applicability) of the findings in the present study is challenged by the context of the study. Most of the GP practices in Copenhagen are solo practices as opposed to other parts of Denmark, where GPs are organized in medical centers.8 The GPs in our study, however, did vary with reference to sex, experience, income, and expertise. There was a risk of informant bias, as recruitment was performed in connection with a series of lectures promoting practice in the primary sector.

The trustworthiness of our study was increased by investigator triangulation. Two investigators conducted the interviews, took field notes, reviewed the transcripts, and translated the direct quotes in the paper. The study is based on key-informant interviews, which supports a high credibility (truth value) and provides us with firsthand knowledge of how GPs handle patients with COPD. Further, the credibility of the study was supported by the high consistency in some of the findings across a broad variety of GPs. With regard to dependability (consistency), all the interviews were conducted in a similar manner with two investigators conducting the interviews. The confirmability (neutrality) of the study was achieved by investigator triangulation with regard to interpreting and evaluating field notes written by the two investigators.

Conclusion

Our study suggested a potential self-reinforcing problem with the treatment of COPD being mainly focused on medication rather than on PR. Neither GPs nor patients used a proactive approach. Further, GPs were not fully committed to discuss non-pharmacological treatment and perceived the patients as unmotivated for PR. As such, there is a need for optimizing non-pharmacological treatment of COPD and in particular the referral process to PR.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Merete Jørgensen for helping recruit the informants and lector Niels Sandholm, PhD, at Metropolitan University College for input regarding study design. CopenRehab is supported by a grant from the Copenhagen Municipality. The study was further supported by grants from the Danish Lung Association.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (homepage) Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. (GOLD) 2016. [Accessed July 11, 2016]. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/

- 2.Dansk Lungemedicinsk Selskab . Danske kol-guidelines [Danish COPD-guidelines] Copenhagen: Dansk Lungemedicinsk Selskab; 2012. [Accessed May 17, 2013]. Available from: http://www.lungemedicin.dk/fagligt/101-dansk-kol-retningslinje-2012/file.html. Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourbeau J, Bartlett SJ. Patient adherence in COPD. Thorax. 2008;63(9):831–838. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.086041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sin DD, McAlister FA, Man SF, Anthonisen NR. Contemporary management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;290(17):2301–2312. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen LM, Elbrønd J. KOL-behandling i almen praksis er i rivende udvikling [COPD treatment in general practice in Denmark is into a rapid development] Ugeskr Læger. 2013;175(18):1271–1276. Danish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bischoff E, Schermer T, Bor H, Brown P, van Weel C, van den Bosch W. Trends in COPD prevalence and exacerbation rates in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(569):927–933. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X473079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schermer T, van Weel C, Barten F, et al. Prevention and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in primary care: position paper of the European Forum for Primary Care. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(5):363–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tønnesen H, Bendix AF, Hendriksen C, et al. Lægens rolle i rehabilitering [The Doctor’s Role in Rehabilitation] Copenhagen: Den Almindelige Danske Lægeforening – Sundhedskomiteen, Læge-foreningens Forlag; 2006. [Accessed June 10, 2015]. Available from: http://www.laeger.dk/portal/pls/portal/!PORTAL.wwpob_page.show?_docname=8542883.pdf. Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brorson S, Gorlén T, Heebøll-Nielsen NC, et al. KOL i almen praksis [COPD in General Practice] Copenhagen: Dansk Selskab for Almen Medicin; 2008. [Accessed June 12, 2015]. Available from: http://www.dsam.dk/files/9/kol.pdf. Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2010. [Accessed July 11, 2016]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange P, Moll L, Koefoed BG, et al. Forløbsprogram for KOL – Hospitaler, almen praksis og kommunerne i Region Hovedstaden [Disease management program for COPD – hospitals, general practice and the municipalities in The Capital Region of Denmark] Approved by Health Coordination Committee; 2009. [Accessed July 11, 2016]. https://www.regionh.dk/Sundhedsaf-tale/bilag-og-download/Documents/RH_Program_KOL_rev_2015.pdf. Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Einarsdóttir K, Preen DB, Emery JD, Kelman C, Holman CD. Regular primary care lowers hospitalisation risk and mortality in seniors with chronic respiratory diseases. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):766–773. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1361-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ansari S, Hosseinzadeh H, Dennis S, Zwar N. Patients’ perspectives on the impact of a new COPD diagnosis in the face of multimorbidity: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14036. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salinas GD, Williamson JC, Kalhan R, et al. Barriers to adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines by primary care physicians. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2011;6:171–179. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S16396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer KA, Antic R, Frith PA. Barriers to, and facilitators for, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients from the perspective of Australian general practitioners: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(3):319–324. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer-Somers KA, Antic R, Frith PA. Why are some evidence-based care recommendations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease better implemented than others? Perspectives of medical practitioners. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2011;6:659–667. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S26581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. World Medical Association; 2013. [Accessed December 1, 2015]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilchrist VJ, Williams RL. Key informant interviews. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, editors. Doing Qualitative Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer WA, Fischer JD, Harman J. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model: a general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008. pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams V, Hardinge M, Ryan S, Farmer A. Patients’ experience of identifying and managing exacerbations in COPD: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14062. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodgers S, Dyas J, Molyneux AW, Ward MJ, Revill SM. Evaluation of the information needs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease following pulmonary rehabilitation: a focus group study. Chron Respir Dis. 2007;4(4):195–203. doi: 10.1177/1479972307080698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boeckxstaens P, Deregt M, Vandesype P, Willems S, Brusselle G, De Sutter A. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities through the eyes of the patient. Chron Respir Dis. 2012;9(3):183–191. doi: 10.1177/1479972312452436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apps LD, Harrison SL, Williams JE, et al. How do informal self-care strategies evolve among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease managed in primary care? A qualitative study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulm Dis. 2014;9:257–263. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S52691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyde N, Casey D, Murphy K, et al. COPD in primary care settings in Ireland: stories from usual care. Br J Community Nurs. 2013;18(6):275–282. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2013.18.6.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan R, Deci E. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ZuWallack R, Hedges H. Primary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-part 3: pulmonary rehabilitation and comprehensive care for the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2008;121(7 Suppl):S25–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourbeau J. Making pulmonary rehabilitation a success in COPD. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13067. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.13067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, Murphy K, Murphy E, Lacasse Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD003793. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]