Abstract

This study introduces the Balance Exercises Circuit (BEC) and examines its effects on muscle strength and power, balance, and functional performance in older women. Thirty-five women aged 60+ (mean age = 69.31, SD = 7.35) were assigned to either a balance exercises group (BG, n = 14) that underwent 50-min sessions twice weekly, of a 12-week BEC program, or a wait-list control group (CG, n = 21). Outcome measures were knee extensor peak torque (PT), rate of force development (RFD), balance, Timed Up & Go (TUG), 30-s chair stand, and 6-min walk tests, assessed at baseline and 12 weeks. Twenty-three participants completed follow-up assessments. Mixed analysis of variance models examined differences in outcomes. The BG displayed improvements in all measures at follow-up and significantly improved compared with CG on, isokinetic PT60, PT180 (p = 0.02), RFD (p < 0.05), balance with eyes closed (p values range .02 to <.01) and TUG (p = 0.03), all with medium effect sizes. No changes in outcome measures were observed in the CG. BEC improved strength, power, balance, and functionality in older women. The BEC warrants further investigation as a fall prevention intervention.

Keywords: Exercise, Muscle strength, Task performance, Aged, Balance

Introduction

Aging is associated with a general decline in the musculoskeletal and sensory systems involved in the maintenance of postural control (Isles et al. 2004; Farinatti 2013; Tiedemann, et al. 2011). Lower extremity weakness and balance impairment are major independent intrinsic risk factors for falls and loss of independence (Orr et al. 2008; Pizzigalli et al. 2011). Preservation of these essential elements of postural stability is critically important for autonomy in the performance of activities of daily living and for reducing the risk of falls in older age.

A 2011 Cochrane systematic review that included 94 randomized controlled trials concluded that certain types of exercise, such as gait, balance, coordination, and functional training, strengthening exercise, and other three-dimensional exercise programs are moderately effective in improving balance in people aged 60 years and over (Howe et al. 2011). Furthermore, exercise that challenges balance plays a particularly important role in preventing falls in older people (Sherrington et al. 2011; Gillespie et al. 2012). Moreover, further benefits are likely if in addition to improving balance, training programs for older individuals also target improvements in muscle strength and functional independence (Eyigor et al. 2007; Swanenburg et al. 2007; Giné-Garriga et al. 2010; Bird et al. 2011; Kuptniratsaikul et al. 2011). Interventions specifically designed to improve balance and strength in older people are expected to have important clinical implications.

Costa et al. (2012) developed a Balance Exercises Circuit (BEC) program, a new comprehensive design that includes exercise stations that specifically challenge sensory inputs from mechanoreceptors as well as from the visual and vestibular systems. The exercises included in the circuit were selected with reference to published research about the characteristics of effective fall prevention exercise programs (Gillespie et al. 2012) and with reference to exercise for fall prevention best practice guidelines (Sherrington et al. 2011; Tiedemann, et al. 2011). Exercise stations were also designed to simulate activities of daily living so that in addition to stimulating balance the program has the potential to improve physical functioning. It is clear from the literature that in order to improve balance and prevent falls, exercise needs to be conducted in a standing position and needs to include movement of the body’s center of gravity, narrowing of the base of support and a reduction in the use of upper limb support. Exercise should also include progressive increases in the degree of balance challenge and should be ongoing (Sherrington et al. 2011; Tiedemann, et al. 2011). These factors were considered in the design of the BEC.

The BEC is conducted in an outdoor space, with a specifically designed court that contains clearly marked exercise stations which are supervised by trained exercise specialists, as described elsewhere (Herdman 2002; Costa et al. 2012). Briefly, the circuit is composed of 13 stations, involving static and dynamic balance exercises, including tandem walking, forward-backward stepping, wide-stance gait, functional reach, heel lift, toe press, balance on unstable surfaces, and standing on one leg (Costa et al. 2012). Costa et al. (2012) reported improvements in balance and a reduction in fall risk as indicated by improvements in the Berg Balance Scale scores, among 32 older people after 12 weeks of twice-weekly BEC participation. However, further investigation of the effect of the BEC intervention on more objective measures of both static and dynamic balance, and the impact on functional mobility is important before its practical implementation. Moreover, given the documented relationship between muscle strength and balance (Binda et al. 2003; Kouzaki 2010; Brech et al. 2013), investigation of the influence of BEC on strength and power-related indexes such as rate of force development (RFD) is important. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effects of the BEC program on muscle strength and power, balance, and functional performance in older community-dwelling women.

Material and methods

Study design

We conducted a quasi-experimental study with follow-up after a 12-week intervention. The trial was conducted during 2012/2013 in Brasilia, Brazil. To examine the effects of participation in the BEC program on muscle strength, balance, and functional performance, a sample of older women was divided into an intervention or a wait-list control group, with outcome variables being measured both before and after the intervention period in all participants. At baseline, participants underwent a semi-structured interview to obtain information about sociodemographic variables, comorbidities, current medication use, and fear of falling. Participants also underwent an assessment of their balance, strength, and functional mobility. Dependent variables were selected based on their relationship with falls and their established clinical significance among older adults. The experimental protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee at The University of Brasilia under protocol 167/2011 and all participants gave written informed consent.

Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisements on television, newspapers, and through presentations in the local community. Eligible participants were women who were aged 60 years or more, who were physically independent, not currently engaged in a structured exercise program, and who were able to understand the trial procedures. Exclusion criteria were as follows: any physical or functional conditions that could be aggravated as a result of the proposed activities or that could prevent full participation in the study such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, use of prosthesis in the lower limbs, and participation in regular and targeted physical activity.

Participants were allocated to the BEC intervention or wait-list CG based on whether or not they had completed all baseline assessments, at the time of BEC intervention commencement. The BEC intervention began during the third week of baseline assessments, when 14 participants had completed all assessments; hence, these people were allocated to the BEC intervention. Twenty-one people were yet to complete the assessments and were therefore allocated to the wait-list control group. Volunteers had no choice regarding group allocation.

Participants were reassessed on all study measures after intervention completion at week 12 (Fig. 1), with a total of 10 participants completing the intervention in the experimental group and 13 completed all the evaluations in the control group.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study design

Intervention group

Participants in the BG participated in the BEC, for 50 min, two times per week for a total of 12 weeks. Each BEC session comprised of warm-up and stretching (10 min), exercise circuit (30 min), and cool-down (10 min). Thirteen workstations were organized in a circuit format on an outdoor court at the University of Brasilia that was specifically designed for this purpose. The stations were painted onto the court and involved multidirectional gait in different bases of support, unstable surfaces, functional reach, exercise with balls, and single-leg stance. The components and exercises of the circuit are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for categorical variables of the total sample and of the intervention (BG) and control groups (CG)

| Total (n = 23) | BG (n = 10) | CG (n = 13) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.3 ± 5.63 | 70.10 ± 6.6 | 66.92 ± 4.5 | 0.875 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.974 | |||

| Maiden | 4 (17.4) | 2 (20) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Married | 8 (34.8) | 4 (40) | 4 (30.8) | |

| Widow | 5 (21.7) | 2 (20) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Divorcee | 6 (26.1) | 2 (20) | 4 (30.7) | |

| Years of formal education, n (%) | 0.551 | |||

| Up to 8 | 7 (30.5) | 2 (20) | 5 (38.5) | |

| 8 to 11 | 3 (13.0) | 1 (10) | 2 (15.4) | |

| More than 12 | 13 (56.5) | 7 (70) | 6 (46.1) | |

| Prevalent diseases, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 13 (56.5) | 6 (60) | 7 (53.8) | 0.768 |

| Diabetes | 3 (13.0) | 2 (20) | 1 (7.7) | 0.385 |

| Visual problems | 21 (91.3) | 9 (90) | 12 (92.3) | 0.846 |

| Labyrinthitis | 1 (4.3) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0.244 |

| Arthritis | 4 (17.4) | 3 (30) | 1 (7.7) | 0.162 |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis | 12 (52.2) | 6 (60) | 6 (46.1) | 0.510 |

| Number of medications, n (%) | 0.285 | |||

| Up to 2 | 17 (74.0) | 9 (90) | 8 (61.6) | |

| 3 or 4 | 5 (21.7) | 1 (10) | 4 (30.7) | |

| 5 or more | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Falls in the previous year, n (%) | 6 (26.1) | 3 (30) | 3 (23.1) | 0.793 |

| Fear of falling, n (%)a | 11 (47.8) | 6 (60) | 5 (38.5) | 0.392 |

| Walking, n (%)b | 11 (47.8) | 5 (50) | 6 (46.2) | 0.632 |

aMeasured with a “Yes” or “No” response to the question “Are you fearful of falling?”

bMeasured with “Yes” or “No” response to the question “Do you practice regular physical activity?”

Participants completed the circuit in pairs in order to encourage social interaction and safety and to maximize enjoyment. The participants exercised at each station for 2 min (1 min for each participant of the pair), and a whistle was blown after 2 min to indicate the need to move on to the next exercise station. Participants completed the circuit in 30 min, including time for a short break to drink water.

Progression of exercises occurred every 3 weeks and was closely supervised to ensure safety, especially in the first week in which the progression was introduced. Progressions were as follows: (1) exercises performed with eyes open, (2) exercises performed with eyes closed, (3) exercises performed with obstacles and eyes open, and (4) exercises performed with obstacles and eyes closed (Costa et al. 2012). Progressions were applied on an individual basis, with instructors judging whether or not participants were ready to attempt the more difficult activities of the next progression.

Participants were supervised by trained exercise specialists while undertaking the BEC to ensure safety and the use of correct exercise techniques. Verbal encouragement and feedback were also offered by the trainers.

Control group

The CG was asked not to alter their daily routine during the study period. In order to maintain study participation, the BEC was offered to the CG after follow-up assessments had been conducted.

Study measures

The primary outcome measures were balance and muscle strength. Secondary outcome measures were functional mobility and rate of force development. All outcome measures were assessed at the same time of day and by the same investigator throughout the study. Assessments were conducted using well-established laboratory procedures for muscle strength/power and balance, including isokinetic dynamometer and force platform, respectively. Validated clinical tests were used to evaluate physical function. Also, prior to the measurement of all outcomes, a familiarization trial was conducted to ensure participants understood the assessment instructions. The study measures are described below.

Static and dynamic balance

Static balance was evaluated using an AccuSway Plus force platform (AMTI Inc.) which measures displacements of the center of pressure (COP). The force platform signals were sampled at 100 Hz and data were filtered using a fourth Butterworth filter with cutoff frequency of 10 Hz. The software Balance Clinic (AMTI Inc.) was used for signal recording (Scoppa et al. 2013). The reliability coefficient was described elsewhere (r ≥ 0.75) (Ruhe 2010).

Environmental conditions during testing were kept consistent, with no visual and auditory disturbances. An assessor was always positioned laterally to the platform to ensure participant safety. To standardize participant stance position, the platform was marked with a 2-cm width tape to indicate the desired positioning of the feet. Participants were asked to keep their sight fixed at a mark on the wall positioned 1.5 m away from the platform and 1.5 m above floor level (Prado et al. 2007; Duarte and Freitas 2010) and to breathe normally. Participants were on barefoot and were instructed to stand for 30 s on the force platform, with arms relaxed and with minimal body sway. Two trials of bilateral stance with eyes closed were completed with a 20- to 30-s rest period between trials.

For statistical analyses, postural sway was quantified by peak-to-peak amplitude COP oscillations along the anterior/posterior and medial/lateral axis (COPap and COPml, respectively) in centimeters (cm) and average speed of displacement (COPvel) in centimeters/second (cm/s). These parameters are considered as representative of the COP displacement providing information about the limits of stability of the body oscillations during a postural task, as well as the total trajectory around a median position during a fixed duration (Duarte and Freitas 2010; Scoppa et al. 2013). The average of two trials in each protocol was calculated and included in analyses.

The Timed Up & Go test was included as a measure of dynamic balance and functional mobility and because it has been associated with fall risk. The test measured the time participants took to rise from a chair, walk 3 m at their usual pace, turn, return to the chair, and sit down (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991). The time taken to complete the task was recorded and the fastest of the two trials was included in the analyses. The high reliability coefficient have been described elsewhere (ranging from 0.95 to 0.97) (Steffen 2002).

Isokinetic peak torque

Dominant-side knee extensor peak torque (PT) and rate of force development (RFD) were assessed using an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex System 3, Medical Systems, NY, USA). After a detailed explanation of the procedures and calibration of the equipment, participants were seated so that the rotation axis of the dynamometer arm was aligned with the femoral lateral epicondyle. The force application point was positioned 2 cm above the medial malleolus of the ankle. Velcro belts were used to secure the trunk, pelvis, and thigh to avoid possible compensatory movements. Equipment positioning for each participant was recorded to ensure consistent conditions for the re-assessment measurements. After a warm-up involving two sub-maximal sets of 10 repetitions, the testing protocol consisted of two sets of four maximal contractions at 60°/s (PT60) and two sets of four maximal contractions at 180°/s (PT180), with 1-min rest intervals between sets (Bottaro et al. 2005). Participants were asked to perform contractions with maximum effort, and verbal encouragement was provided during the test. The highest PT for each speed was recorded for subsequent analyses. Baseline test/retest reliability coefficient (ICC) value for knee extensor peak torque was 0.91.

Rate of force development (RFD) at time intervals of 0–50, 0–100, 0–200, 0–300 ms, and 0-PT attainment were calculated for PT60. Data were collected from the Biodex software and analyzed in MATLAB R2010a software. Data were butterworth-filtered at 10 Hz and calculation of RFD was performed according to procedures described elsewhere (Corvino 2009; Oliveira et al. 2010). Briefly, throughout the contraction, RFD was derived as the average slope of the moment-time curve (∆torque/∆time) over time. Onset of muscle contraction was defined as the time point at which the moment curve exceeded baseline by >7 Nm (Aagaard et al. 2002).

Functional mobility

Functional mobility was assessed with the 30-s chair stand test and with the 6-min walk test. Prior to assessment, participants were given detailed instructions and a demonstration of the test procedures.

The 30-s chair stand test is a measure lower-body strength, balance, and endurance. Participants were seated in a standard-height chair with arms crossed over the chest and were then instructed to stand up fully and sit down fully as many times as possible within 30 s (Rikli and Jones 2008). The reliability of this test has been previously described (r = 0.92) (Jones 1999).

The 6-min walk test is a measure of functional capacity and endurance. This test was conducted according to procedures previously described (Rikli and Jones 2008) using a circuit 45.72 m in length that was marked with cones placed every 4.57 m. Participants were instructed to walk at their own pace in order to cover as much distance as possible in 6 min without running. The distance covered in 6 min, measured in meters, was recorded. The reliability of this test has been described elsewhere (ranging from 0.95 to 0.97) (Steffen 2002).

Adverse events and intervention adherence

Class attendance was recorded by the BEC instructors at each session. Adverse events associated with BEC participation were discussed at the follow-up assessment session and recorded in the data collection forms.

Statistical analysis

Mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) models with Bonferroni post hoc analyses were used to examine differences between groups before and after the intervention for all outcome variables. In addition, the effect sizes (ES) were calculated according with Cohen’s d specifications. Data were analyzed using SPSS v.18.0 for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA). A p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Baseline data

Ninety-one older women volunteered for the research but 41 of these people did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, at baseline 50 participants underwent the semi-structured interview to obtain demographic and health-related data. Fifteen potential participants did not complete the baseline assessment and were excluded from further participation; therefore, 35 participants were allocated to either the balance group (BG, n = 14) involving the Balance Exercise Circuit (BEC) or to a wait-list control group (CG, n = 21). Four BG participants dropped out during the intervention due to reasons such as ill health (n = 2), lack of transportation (n = 1), and lack of interest (n = 1). Moreover, eight CG participants were excluded from analyses due to high body weight change during the study period (n = 1) and non-completion of all the re-assessments (n = 7). Therefore, by the end of the 12-week intervention, 23 participants, (10 BG, 13 CG) provided data for the analyses. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the study (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics for categorical variables according to group allocation are presented in Table 2. The participants in the two study groups had similar baseline characteristics (included in Table 2). The mean age of the sample was 68.3 (±5.63) years (range 61–81 years). Just over one quarter (26 %) of participants had experienced a fall in the past year and almost half (48 %) of the sample reported being fearful of falling. Moreover, there were no significant between-group differences regarding age, body weight, height, or body mass index (all p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Description of movements and activities of Balance Exercises Circuit (BEC)

| Stretching and warming-up | Balance Exercises Circuit | Cooling-down |

|---|---|---|

| Stretching Lower limbs Upper limbs |

All exercises were performed in pairs and for 2 min | Exercises in group Exercises for the eyeball Memory exercises Ball games Motor coordination Rhythm exercises Vestibular exercises Breathing exercises |

| 1. Side steps to the right and to the left. | ||

| 2. “Airplane-like”—standing on one foot, right and left. | ||

| Warm-up exercises Multidirectional gait Rhythmic gait Step change Gait with stops Gait with turns Hip flexion Hip abduction Hip adduction Hip extension Knee flexion Plantar flexion |

3. Backward-sensitive walking (on the heels). | |

| 4. Backward walking on the whole foot. | ||

| 5. “Hit the target” with the back turned to the target and the balls attached by ropes on the sides. | ||

| 6. Balance and walking on unstable surface (mattress, balance disc, and balance board). | ||

| 7. Sensitive walking (using only the anterior portion of the foot). | ||

| 8. Forward walking on the whole foot with legs apart. | ||

| 9. Multidirectional reach (difficulty levels with varying heights represented by the numbers 1, 2, and 3). | ||

| 10. Forward walking on the whole foot with legs crossed. | ||

| 11. “Ball in the basket” (difficulty levels with varying distances represented by the three divisions of the box). | ||

| 12. Walking on narrowed base and circumferential path. | ||

| 13. Tandem gait (straight-line forward and backward walking). |

Intervention adherence and participant retention

The number of BEC sessions attended ranged from 18 to 24 with a mean session attendance of 21.7 out of 24 sessions offered (SD 2.11, 91 % mean attendance).

Adverse events

There were no adverse events associated with BEC participation. Moreover, progression was well tolerated by all volunteers.

Effects of intervention on outcome measures

Table 3 shows the baseline and 12-week follow-up results for the outcome measures. There were no significant between-group differences in muscle strength, functional, or force platform variables (all p > 0.05). ANOVA revealed a significant time × group interaction for 6-min walking test (F(1,21) = 16.654, p = <0.01) and isokinetic PT60 (F(1,21) = 4.559, p = 0.04) and a trend but not quite statistical significance for PT180 (F(1,21) = 6.089, p = 0.05). For the intra-group analyses, in the BG, there were significant improvements in TUG (F(9) = 3.936, p = 0.03, ES = 0.67), and PT180 (F(9) = 2.897, p = 0.02, ES = 0.48) at follow-up. In the CG, there was a significant decline in the 6-min walk test performance at follow-up (F(12) = 1.278, p = <0.01, ES = 0.55). Δ% values indicate better results for the BG compared to the CG for all variables presented in Table 3, with the changes varying from 3.20 to 10.72 % in the BG. In general, by the end of the intervention, all the mean values for these outcomes were better for BG when compared to CG, though statistically significant differences were only noted for isokinetic muscle strength at 180°/s (p = 0.02).

Table 3.

Mean (SD) of groups at baseline and follow-up, percentage change within groups, and between-group comparison at follow-up on the outcome variables

| Balance group (n = 10) | Control group (n = 13) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | ∆% | p a | Pre | Post | ∆% | p a | p b | |

| Timed Up & Go (s) | 6.12 ± 0.54 | 5.72 ± 0.62a | −6.53 | 0.03 | 5.89 ± 0.80 | 5.83 ± 0.72 | −1.00 | 0.70 | 0.16 |

| 30-s chair stand test (rep) | 18.60 ± 5.60 | 20.10 ± 4.43 | +8.06 | 0.22 | 19.38 ± 4.07 | 18.38 ± 3.01 | −5.16 | 0.34 | 0.13 |

| 6-min walking test (m)b | 514.41 ± 60.35 | 530.89 ± 51.95 | +3.20 | 0.06 | 532.14 ± 53.13 | 503.04 ± 50.56a | −5.47 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| PT60 (Nm)b | 83.32 ± 21.79 | 89.10 ± 15.28 | +6.94 | 0.08 | 86.61 ± 9.24 | 83.53 ± 9.49 | −3.56 | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| PT180 (Nm)b | 56.45 ± 12.69 | 62.31 ± 11.58a | +10.38 | 0.02 | 53.47 ± 5.88 | 52.91 ± 6.32 | −1.05 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| COPap (cm) | 2.47 ± 0.82 | 0.93 ± 2.04a | −62.34 | <0.01 | 1.93 ± 0.40 | 0.96 ± 1.47a | −50.25 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| COPml (cm)b | 0.96 ± 0.39 | 0.82 ± 0.27a | −14.60 | 0.06 | 0.75 ± 0.21 | 0.84 ± 0.30 | +12.00 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| COPvel (cm/s)b | 1.41 ± 0.58 | 1.18 ± 0.46 | −16.31 | 0.19 | 1.18 ± 0.38 | 2.04 ± 0.71a | +72.88 | <0.001 | <0.01 |

PT60 peak torque at 60°/s, PT180 peak torque at 180°/s, COPap center of pressure oscillation along anterior/posterior axis, COPml center of pressure oscillation along medial/lateral axis, COPvel average speed of displacement

a p values for within group comparisons (p < 0.05)

b p values for group × time interaction (p < 0.05)

Results of force platform parameters are also presented in Table 3. ANOVA revealed significant time × group interaction for COPap (F(1,21) = 5.941, p = 0.02), COPml (F(1,21) = 21.472, p = 0.02), and COPvel (F(1,21) = 21.472, p = <0.01). COPap showed mean reductions in both groups, however, at a significantly greater degree for the BG, which showed statistical significance (F(9) = 50.989, p = <0.01, ES = 2.96). COPml significantly decreased in the BG (F(9) = 0.259, p = 0.01, ES = 0.42) and significantly increased in the CG (F(12) = 0.259, p = <0.01, ES = 0.05). For COPvel, BG presented a mean reduction without statistical significance, while CG showed significant increases (F(12) = 6.677, p = <0.01, ES = 1.21). Overall, these results indicate better static balance after the training protocol for the BG compared with the CG, with statistical significance for COPvel (p = 0.002).

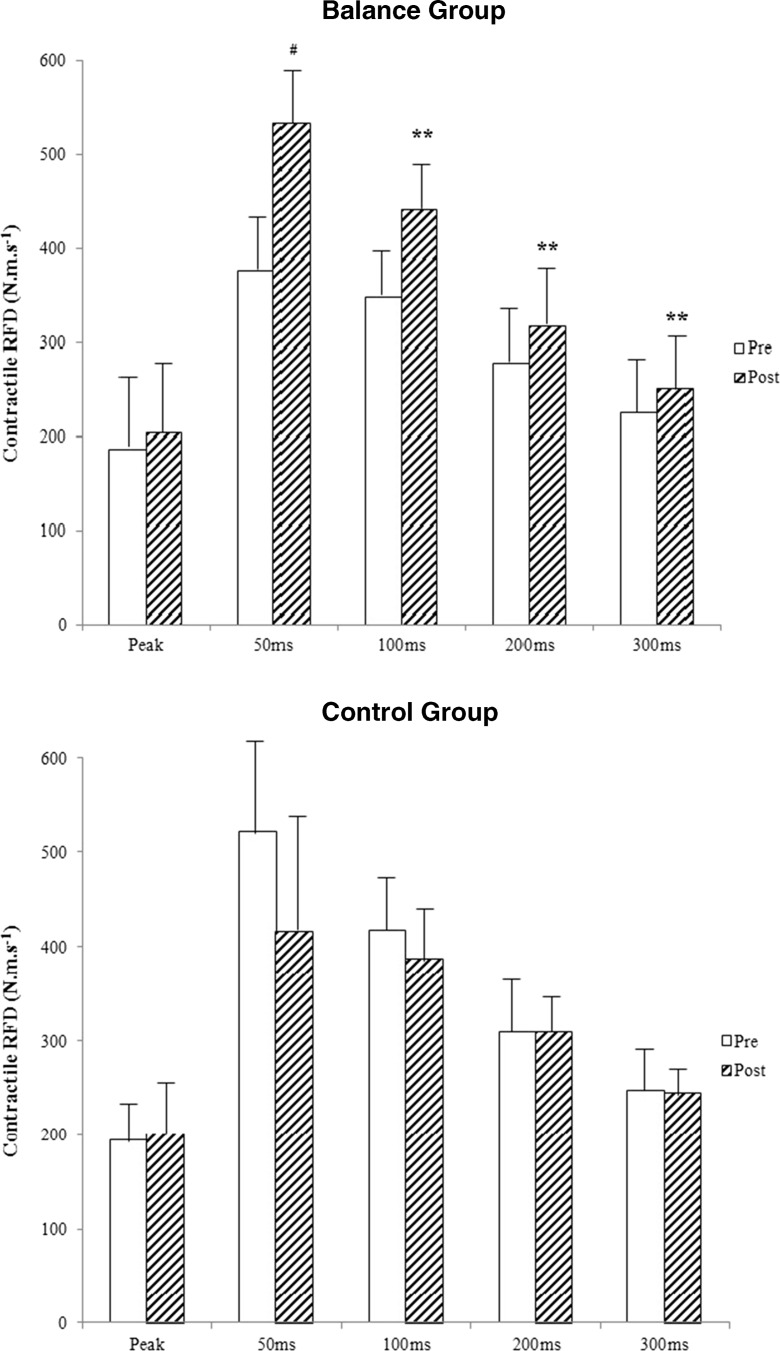

Results for RFD are depicted in Fig. 2. There were significant group × time interactions for 0–100 (F(1,21) = 8.643, p = 0.01), 0–200 (F(1,21) = 5.185, p = 0.03), and 0–300 (F(1,21) = 4.742, p = 0.04) time intervals. In addition, post hoc analyses revealed that post-training values were significantly increased when compared to pre-training for BG (0–100: F(9) = 2.248, p = <0.01; 0–200: F(9) = 5.135, p = <0.01; and 0–300: F(9) = 2.881, p = 0.04). No significant time × group interaction was noted for 0-PT interval and RFD values remained unchanged at re-assessment for the CG (all p > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Contractile RFD (means) before (open bars) and after (hatched bars) 12 weeks of BEC in BG and CG, respectively. Rate of force development (RFD) (∆moment/∆time) was calculated in time intervals of 0–50, 100, 200, 300 ms, and until the peak torque from the onset of contraction. Group × time interactions: *p ≤ 0.05; significant intra-group differences: **p < 0.05, # p = 0.08

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the BEC program attended twice a week for 12 weeks improved leg strength and power, static and dynamic balance, and mobility. The CG did not show any improvement in any of the study outcomes. The BEC program was feasible and acceptable, with average participant adherence above 91 %. These results indicate that the BEC intervention is likely to promote functional independence in older women and provides preliminary evidence that it may be effective in reducing the risk of falls.

The BEC program was not primarily designed to improve muscle strength; however, significant improvements (ranging from 6.94 to 10.38 %) were observed in knee extensor isokinetic PT at different angular speeds 60°/s (6.94 %) and 180°/s (0.38 %). Previous research employing similar intervention protocols has found consistent results (Eyigor et al. 2007; Carvalho et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2010). In addition, the improvement in RFD as a result of the intervention is highly significant in relation to the ability to produce rapid muscle contraction to prevent a fall (Aagaard et al. 2002). To achieve this aim of balance recovery, there is usually a need for maximal muscle force to be reached in less than 200 ms (Aagaard et al. 2002). Therefore, increases in muscle strength and time to reach contraction (i.e., RFD) become highly important to the older adult and are likely to have important clinical implications for fall prevention.

Regarding static balance, significant between-group differences were observed in three variables of center of pressure (CP) (COPap, COPml, COPvel) for open stance with eyes closed protocol (OBEC), all demonstrating advantage for the BG. This measure simulates the natural position adopted in activities of daily living to acquire stability, since visual information is removed and sensory information mostly rests on the peripheral proprioceptive system (Hurley et al. 1998). With the absence of vision, proprioceptive and vestibular information must be relied upon, with additional attention demand in both systems (Teasdale and Simoneau 2001). Of note, suppression of visual information was conducted during the progression of the BEC both in the static and dynamic activity stations, providing specific stimuli for the remaining sensory systems.

Agility and dynamic balance skills evaluated by the TUG showed significant improvements (−6.3 %) after the intervention period only in the BG. This observation is consistent with results in previous studies that applied interventions with similar principles used in the BEC and with the same amount of sessions (Eyigor et al. 2007; Donat and Ozcan 2007; Fu et al. 2009; Alfieri et al. 2010). However, these authors had superficially described the types of exercises and stimuli, only in a broad way, reporting only the total duration of sessions, which was approximately 50 to 60 min.

Lower limb function and aerobic capacity assessed with the 30-s chair stand test and 6-min walk test, respectively, did not show significant improvements after 12 weeks. However, we observed a trend of improvement in the performance of these tests in the BG (8.06 and 3.20 %, respectively) with concomitant reduced performance in the control group. Furthermore, the participants in both groups performed well in the sit to stand test at baseline, which may have made additional gains in this area difficult to achieve over the short study period. Previous studies that included more than 24 exercise sessions elicited improved performance in these tests (Rubenstein et al. 2000; Carvalho et al. 2010) and specific strength or aerobic training was also associated with significant improvements in these measures (Eyigor et al. 2007). We suggest that future research should include a higher intervention dose to fully investigate the effect of the BEC on these variables. A longer duration intervention would also be in accordance with fall prevention guidelines that recommend a dose of 50 h or more of exercise to maximize fall prevention benefit (Sherrington et al. 2011).

The results presented are likely to have important practical applications. The BEC program is a new format of exercise delivery, developed with reference to published evidence on effective exercise to maximize balance and function and prevent falls in older age. It is easy to reproduce the protocol used and to implement the BEC into other settings with minimal equipment. Importantly, these results show that the BEC is feasible for older women with a range of comorbidities to undertake safely. Furthermore, the BEC is a low-cost intervention highly reproducible and attractive and enjoyable from the older persons’ perspective, making it a particularly promising intervention to be delivered in low-middle income countries. The promising results of this study in relation to the effect of the BEC on strength, balance, and power should prompt further investigation of the role of the BEC in preventing falls.

We acknowledge this study has some limitations. Firstly, the small sample size makes it difficult to draw conclusions about wider implications of the results and increases the likelihood of type I and II errors. However, this was designed as a pilot study to assess the feasibility of the BEC intervention for older people and to assess the intervention effect on balance, strength, and function in preparation for a planned large trial with rate of falls as the primary outcome. Also, due to logistical procedures, participants were not randomly allocated into the two study groups. However, comparisons on sociodemographic and outcome measures between the groups at baseline showed that the groups were similar at study commencement. Additionally, as we only included females in this study, the effect of the BEC in men is not clear. Finally, the intervention was limited to only 12 weeks of BEC, which we acknowledge to be less than the recommended 50 or more hours of balance challenging exercise that is recommended in clinical guidelines (Sherrington et al. 2011) and which is likely to reduce the risk of falls in older people. Future studies should therefore include a longer duration intervention and should have a large enough sample size to be powered to examine the effect of the BEC intervention on falls rates in older people.

Conclusions

These results show that the BEC program is an acceptable and effective intervention for older women to promote improvements in important aspects of physical functioning, autonomy, and health. Specifically, the intervention resulted in improved muscle strength and power, balance, and functional capacity in a sample of older women. High participant adherence with the intervention illustrates the importance of programs that incorporate socialization, exercises that are similar to activities of daily living and a supervised and supported approach to attract and retain participation by older women.

References

- Aagaard P, Simonsen EB, Andersen JL, Magnusson P & Dyhre-Poulsen P (2002). Increased rate of force development and neural drive of human skeletal muscle following resistance training. J Appl Physiol (1985) 93(4):1318–1326. Fonte: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00283.2002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Alfieri FM, Riberto M, Gatz LS, Ribeiro CP, Lopes JA, Battistella LR. Functional mobility and balance in community-dwelling elderly submitted to multisensory versus strength exercises. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:181–185. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S10223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda SM, Culham EG, Brouwer B. Balance, muscle strength, and fear of falling in older adults. Exp Aging Res. 2003;29(2):205–219. doi: 10.1080/03610730303711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird M, KD H, Ball M, Hetherington S, AD W. The long-term benefits of a multi-component exercise intervention to balance and mobility in healthy older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(2):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottaro M, Russo AF, de Oliveira RJ. The effects of rest interval on quadriceps torque during an isokinetic testing protocol in elderly. J Sports Sci Med. 2005;4(3):285–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brech GC, Alonso AC, Luna NM, Greve JM. Correlation of postural balance and knee muscle strength in the sit-to-stand test among women with and without postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(7):2007–2013. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho J, Marques E, JM S, Mota J. Isokinetic strength benefits after 24 weeks of multicomponent exercise training and combined exercise training in older adults. Aging Clint Exp Res. 2010;22(1):63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03324817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvino RC. Taxa de desenvolvimento de força em diferentes velocidades de contrações musculares. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Esporte. 2009;15(6):428–431. doi: 10.1590/S1517-86922009000700005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J, Avelar B, Gonçalves C, Pereira M, Safons M (2012) Efeitos do circuito de equilíbrio sobre o equilíbrio funcional e a possibilidade de quedas em idosas. Motricidade 8(S2):485-492.

- Donat H, Ozcan A. Comparison of the effectiveness of two programmes on older adults at risk of falling: unsupervised home exercise and supervised group exercise. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(3):273–283. doi: 10.1177/0269215506069486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M, Freitas S. Revisão sobre posturografia baseada em plataforma de força para avaliação do equilíbrio. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia. 2010;14:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyigor S, Karapolat H, Durmaz B. Effects of a group-based exercise program on the physical performance, muscle strength and quality of life in older women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45(3):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinatti PG. Effects of different resistance training frequencies on the muscle strength and functional performance of active women over 60 years-old. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013;27(8):2225–2234. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318278f0db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S, Choy NL, Nitz J. Controlling balance decline across the menopause using a balance-strategy training program: a randomized, controlled trial. Climacteric. 2009;12(2):165–176. doi: 10.1080/13697130802506614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, Lamb SE. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giné-Garriga M, Guerra M, Pagès E, TM M, Jiménez R, VB U. The effect of functional circuit training on physical frailty in frail older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;18(4):401–424. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman S (2002) Reabilitação Vestibular (2 ed.). Manole.

- Howe TE, Rochester L, Neil F, Skelton DA, Ballinger C (2011) Exercise for improving balance in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11):CD004963. Fonte: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004963.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hurley MV, Rees J, Newham DJ. Quadriceps function, proprioceptive acuity and functional performance in healthy young, middle-aged and elderly subjects. Age Ageing. 1998;27(1):55–62. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isles RC, Choy NL, Steer M, Nitz JC. Normal values of balance tests in women aged 20–80. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1367–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CR (1999) A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 70(2):113–119 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim K, Piao Y, Kim N, Kwon T (2010) Characteristic analysis of the isokinetic strength in lower limbs of the elderly on training for postural control. Int J Precis Eng Manuf 6:955–967

- Kouzaki M (2010) Steadiness in plantar flexor muscles and its relation to postural sway in young and elderly adults. Muscle Nerve 42:78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kuptniratsaikul V, Praditsuwan R, Assantachai P, Ploypetch T, Udompunturak S, Pooliam J (2011) Effectiveness of simple balancing training program in elderly patients with history of frequent falls. Clinical Interventions in Aging 6:111–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oliveira AS, Corvino RB, Gonçalves M, Caputo F, Denadai BS. Effects of a single habituation session on neuromuscular isokinetic profile at different movement velocities. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110(6):1127–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1599-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr R, Raymond J, Fiatarone Singh M. Efficacy of progressive resistance training on balance performance in older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2008;38(4):317–343. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzigalli L, Filippini A, Ahmaidi S, Jullien H, Rainoldi A. Prevention of falling risk in elderly people: the relevance of muscular strength and symmetry of lower limbs in postural stability. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(2):567–574. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d32213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado JM, Stoffregen TA, Duarte M. Postural sway during dual tasks in young and elderly adults. Gerontology. 2007;53(5):274–281. doi: 10.1159/000102938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikli R, Jones C. Teste de Aptidão Física para Idosos. São Paulo: Manole; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ, Josephson KR, Trueblood PR, Loy S, Harker JO, Pietruszka FM, Robbins AS. Effects of a group exercise program on strength, mobility, and falls among fall-prone elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(6):M317–M321. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.M317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe AFR. The test–retest reliability of centre of pressure measures in bipedal static task conditions—a systematic review of the literature. Gait and Posture. 2010;32:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoppa F, Capra R, Gallamini M, Shiffer R. Clinical stabilometry standardization: basic definitions–acquisition interval–sampling frequency. Gait Posture. 2013;37(2):290–292. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington C, Tiedemann A, Fairhall N, Close JC, Lord SR. Exercise to prevent falls in older adults: an updated meta-analysis and best practice recommendations. N S W Public Health Bull. 2011;22(3–4):78–83. doi: 10.1071/NB10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen TH (2002) Age and gender-related test performance in community-dwelling elderly people: six-minute walk test, Berg Balance Scale, Timed Up & Go test, and gait speeds. Phys Ther 82(2):128–137 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Swanenburg J, de Bruin ED, Stauffacher M, Mulder T, Uebelhart D. Effects of exercise and nutrition on postural balance and risk of falling in elderly people with decreased bone mineral density: randomized controlled trial pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(6):523–534. doi: 10.1177/0269215507075206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale N, Simoneau M. Attentional demands for postural control: the effects of aging and sensory reintegration. Gait Posture. 2001;14(3):203–210. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Close JC, Lord SR, Exercise & Australia SS ) Exercise and Sports Science Australia position statement on exercise and falls prevention in older people. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(6):489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]