Abstract

Context

Violence against women, or domestic violence, is both a physical and mental health issue that is rampant in many societies. It undermines the personal health of those involved by inflicting physical, sexual, and psychological damage. The purpose of the present systematic review and meta-analysis is to assess the prevalence of domestic violence in Iranian society.

Evidence Acquisition

A total of 31 articles published between 2000 and 2014 in Iranian and international databases (MagIran, IranMedex, SID, Google Scholar, Science Direct, PubMed, Pre Quest, and Scopus) were examined. The data collected from the articles were analyzed through a meta-analysis using a random effects model. The heterogeneity of the articles was examined using the I2 index, and the analyses were performed with STATA software version 11.2.

Results

Based on the 31 articles, which represent a sample size of 15,514 persons, we estimated the prevalence of domestic violence to be 66% (CI 95%: 55 - 77). The geographical classification showed that the prevalence of domestic violence was 70% (CI 95%: 57 - 84) in the east of the country, 70% in the south (CI 95%: 32 - 100), 75% in the west (CI 95%: 56 - 94), 62% in the north (CI 95%: 37 - 86), and 59% in the center (CI 95%: 44 - 74).

Conclusions

The results of the study showed a high prevalence of domestic violence in Iran, which requires the adoption of appropriate measures and the initiation of effective interventions by the legal authorities. These measures and interventions should aim to determine the causes of domestic violence and to develop ways of controlling and reducing this destructive phenomenon.

Keywords: Domestic Violence, Women, Meta-Analysis

1. Context

Violence is a behavioral model that is imposed on close friends and family members through intimidation, threats, and annoying, harmful behaviors aimed at controlling and manipulating a person. Instances of violence can comprise sexual, physical, and economic abuse, as well as verbal threats and divorce (1). Domestic violence is a serious social and mental health problem that takes the form of violence against women and children or the mistreatment of senior citizens and other vulnerable individuals (2). The most common form of domestic violence is violence, whether physical or mental, against women by their life partner. Many social, mental, and economic problems are rooted in domestic violence, which targets the lives and dignity of women (3). Evidence shows that domestic violence is responsible for physical injuries, digestive system disorders, chronic pain syndrome, depression, anxiety, suicide-oriented behaviors, and pregnancy problems such as unwanted inception, illegal abortion, and early labor (4).

The negative consequences of domestic violence on women’s health can be seen over the long term, affecting the victim long after the original incident (5). According to international statistics, mortality and disabilities caused by domestic violence among women at fertility age are equal to the mortalities resulting from cancer and pregnancy problems and exceed the mortalities caused by car accidents and common diseases (6). In recent decades, domestic violence has been recognized as the world’s most serious social problem, crossing cultural, social, and geographical boundaries to the extent that it is found in all societies and across all social classes. It is considered one of the main health problems among women given the negative effects of domestic violence on physical, mental, and pregnancy health (7). Although the problem of domestic violence is serious, it can be tracked and monitored, and women can be screened for signs of domestic violence during routine health services. Tracking domestic violence is the first step in dealing with the problem (8). It is an international issue that is observable in all societies and cultures regardless of race and social class (9).

The prevalence of domestic violence differs from region to region; for instance, the prevalence is 35% in Mexico and 50% in Bangladesh (10). According to the world health organization (WHO), about one-third of women in the world were victims of domestic violence in 2014 (11). Mazza et al. (12) (2005) estimated the prevalence of domestic violence to be 40% - 50% and maintained that this problem is a threat to the physical and mental health of women, and in some cases, leads women to commit suicide. A 2001 survey of 28 provinces in Iran conducted by the Women and Social Participation Department of the Iranian Ministry of Health showed that 66% of women have been victims of domestic violence at least once (13), while a study by Moasheri et al. (9) (2012) indicated that 83% of women from Birjand suffer from domestic violence, mostly (20.6%) in the form of emotional-mental abuse. Ahmadi et al. (4) (2006) estimated the domestic violence in Tehran at 36%, of which 30% is physical and 29% emotional-mental.

To ascertain the destructive effects of the related sociocultural and health problems, several studies have focused on the prevalence of domestic violence and reported different estimates in Iran. The present study aimed to determine a general estimate of the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran and to assess the general trend of the problem in Iran. The results may be helpful in enlightening policy makers and authorities as to the real situation and the necessity of adopting effective policies and programs to reduce violence against women.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran based on the results reported in articles published in Iranian and foreign journals. The articles were found by searching Iranian (MagIran and IranMedex) and international (SID, Google Scholar, Science Direct, PubMed, PreQuest, and Scopus) databases. The keywords used to find the articles were “domestic violence”, “violence against spouse”, “violence against women” and the Farsi equivalents of the same keywords and possible combinations. To extend the search scope, the references of the found articles were also reviewed.

2.1. Articles and Data Extraction

First, all the articles that were somehow relevant to the topic of domestic violence against Iranian women were collected. The articles were then screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were thematic irrelevance, pregnant women or couples as the subject group, interventional studies, repetitive words, the absence of general estimates, and the unavailability of the full text. The summaries of the articles were reviewed by the authors, and the required data were collected using a specially designed form, which included the first author’s name, the year of publication, the location of the study, the sample size, and the prevalence of domestic violence. To decrease possible bias, the separation method was utilized; the articles were reviewed independently by two researchers, and the relevant articles were included in the analysis. Cases of disagreement were settled by a third researcher (the corresponding author) who has extensive experience in meta-analysis.

Altogether, 31 articles published between 2000 and 2014 were selected out of a total of 106 articles.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Given that prevalence follows a binomial distribution, the variance of prevalence was calculated through binomial distribution variance. To combine the prevalence reported by the different studies, the weighted mean of the reported prevalence was used so that the weight of each article was the inverse variance of the article. To examine the heterogeneity of the data, the I2 index was used, and a heterogeneity index of less than 25% was interpreted as low heterogeneity, 25% - 75% as average heterogeneity, and above 75% as high heterogeneity. With I2 equal to 99.8% (high heterogeneity), a random effects model was used. The relationship between the prevalence of domestic violence, the year of the publication of the article, and sample size was examined by meta-regression, and the data analyses were performed using STATA software version 11.2.

3. Results

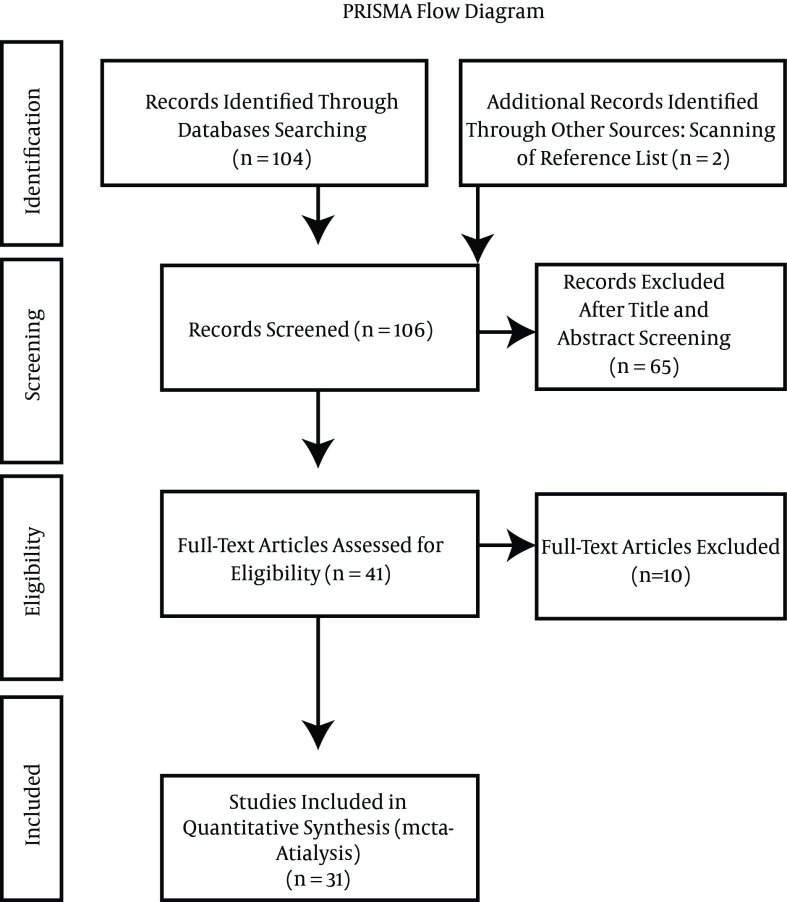

All the relevant articles on domestic violence in Iran published between the years 2000 and 2015 were reviewed systematically based on the PRISMA instruction (14). The primary search yielded 106 articles of which 75 articles were removed from the study based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The flowchart of finding and screening the articles is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Finding and Screening Flowchart.

The selected articles were published between 2000 and 2014 and represented a total sample size of 15,514 subjects (501 subjects per article). Six articles (25%) were in English (15-20). The minimum sample size was attributed to Khosravi Zadegan (2007) (21) and Liaghat (2005) (22) with 100 subjects each, while Nouhjah (2011) (18) used the maximum sample size of 1,820 participants. With respect to the prevalence of domestic violence, Khosravi Zadegan (21) found 100% prevalence while Nouhjah (18) reported 20.2%. In terms of location, the majority of the studies (25%) had been conducted in Tehran (4, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22-25). Some of the most important information about the articles and the prevalence of domestic violence based on province are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Article Specifications in the Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Prevalence of Domestic Violence.

| Row | Author | Year | Location | Sample Size | Questionnaire | Prevalence of Domestic Violence (%) | Confidence Interval 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| 1 | Rasoulian et al. (15) | 2014 | Tehran | 1000 | Checklist | 93 | 36 | 42 |

| 2 | Bahrami (26) | 2014 | Mashhad | 700 | AAS | 87 | 84 | 89 |

| 3 | Sheikhan et al. (16) | 2014 | Tehran | 400 | Domestic violence | 35 | 30 | 39 |

| 4 | Derakhshanpour et al. (27) | 2014 | Bandar Abbas | 500 | - | 92 | 90 | 94 |

| 5 | Shayan et al. (28) | 2013 | Shiraz | 197 | Haj Yahya | 76 | 71 | 82 |

| 6 | Moghaddam Hosseini et al. (17) | 2013 | Sabzevar | 251 | CTS2 | 78 | 73 | 83 |

| 7 | Torkashwand et al.(29) | 2013 | Rafsanjan | 540 | Designed by researcher | 51 | 47 | 55 |

| 8 | Mazloom Khorasani and Mirzaee (30) | 2012 | Khorramabad | 210 | - | 90 | 86 | 94 |

| 9 | Moasheri et al. (9) | 2012 | Birjand | 414 | Designed by researcher | 83 | 80 | 87 |

| 10 | Rahbar et al. (31) | 2012 | Rasht | 320 | Checklist & file | 83 | 79 | 87 |

| 11 | Mohammadi et al. (32) | 2012 | Rawansar | 200 | Designed by researcher | 91 | 87 | 95 |

| 12 | Aliverdinia et al.(23) | 2011 | Tehran | 440 | Designed by researcher | 93 | 90 | 95 |

| 13 | Mohammadi et al. (24) | 2012 | Tehran | 69 | Designed by researcher | 69 | 58 | 80 |

| 14 | Nouhjah et al. (18) | 2011 | Khuzestan | 1820 | Interview | 20 | 18 | 22 |

| 15 | Taherkhani et al. (25) | 2010 | Tehran | 811 | Checklist | 88 | 86 | 91 |

| 16 | Rashti et al. (33) | 2010 | Dezful | 404 | Designed by researcher | 45 | 40 | 50 |

| 17 | Maleki et al. (34) | 2010 | Khorramabad | 383 | Checklist | 83 | 79 | 87 |

| 18 | Ardabili Hasan et al. (19) | 2010 | Tehran | 400 | CTS2 | 62 | 57 | 67 |

| 19 | Balali et al. (35) | 2009 | Kerman | 400 | Designed by researcher | 46 | 41 | 51 |

| 20 | Sarichlo et al. (36) | 2009 | Qazvin | 301 | Designed by researcher | 51 | 45 | 57 |

| 21 | Sedaghat et al. (37) | 2008 | Tabriz | 384 | Designed by researcher | 28 | 23 | 32 |

| 22 | Khosravi Zadegan et al. (21) | 2007 | Bushehr | 100 | Designed by researcher | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 23 | Nojomi et al. (20) | 2007 | Tehran | 1000 | - | 59 | 54 | 62 |

| 24 | Ahmadi et al. (4) | 2006 | Tehran | 1189 | Checklist | 36 | 33 | 38 |

| 25 | Liaghat (22) | 2005 | Tehran | 100 | Designed by researcher | 80 | 72 | 88 |

| 26 | Mousavi (38) | 2005 | Esfahan | 386 | - | 37 | 32 | 42 |

| 27 | Moazzemi et al. (39) | 2004 | Sistan | 350 | Checklist | 77 | 73 | 81 |

| 28 | Bakhtiari and Omidbakhsh (40) | 2003 | Babol | 508 | - | 36 | 32 | 40 |

| 29 | Arefi (41) | 2003 | Urmia | 919 | File information | 82 | 80 | 85 |

| 30 | Esfandabad and Emamipoor (42) | 2003 | Golestan | 400 | Moffitt questionnaire | 82 | 78 | 85 |

| 31 | Elahi and Alhani (43) | 2000 | Ahvaz | 368 | Strauss checklist | 63 | 58 | 64 |

Table 2. The Prevalence Of domestic Violence Based on Province.

| Province | Sample Size | Prevalence | CI 95% | I2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Tehran | 5409 | 82 | 79 | 45 | 0.001 | 99.6 |

| Razavi Khorasan | 951 | 83 | 91 | 74 | 0.003 | 88.4 |

| Bandar Abbas | 500 | 92 | 94 | 90 | - | |

| Shiraz | 197 | 76 | 82 | 71 | - | |

| Kerman | 940 | 49 | 53 | 44 | 0.137 | 54.9 |

| Khorramabad | 210 | 87 | 94 | 80 | 0.01 | 84.9 |

| South Khorasan | 414 | 83 | 87 | 80 | - | - |

| Gilan | 320 | 83 | 87 | 79 | - | - |

| Khuzestan | 2224 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 0.001 | 99.4 |

| Qazvin | 301 | 51 | 57 | 45 | - | - |

| Tabriz | 384 | 28 | 32 | 23 | - | - |

| Esfahan | 386 | 37 | 42 | 2 | - | - |

| Sistan and Bluchestn | 350 | 77 | 81 | 73 | - | - |

| Babol | 508 | 36 | 40 | 32 | - | - |

| Urmia | 919 | 82 | 85 | 80 | - | - |

| Golestan | 400 | 82 | 85 | 78 | - | - |

| Kermanshah | 200 | 91 | 95 | 87 | - | - |

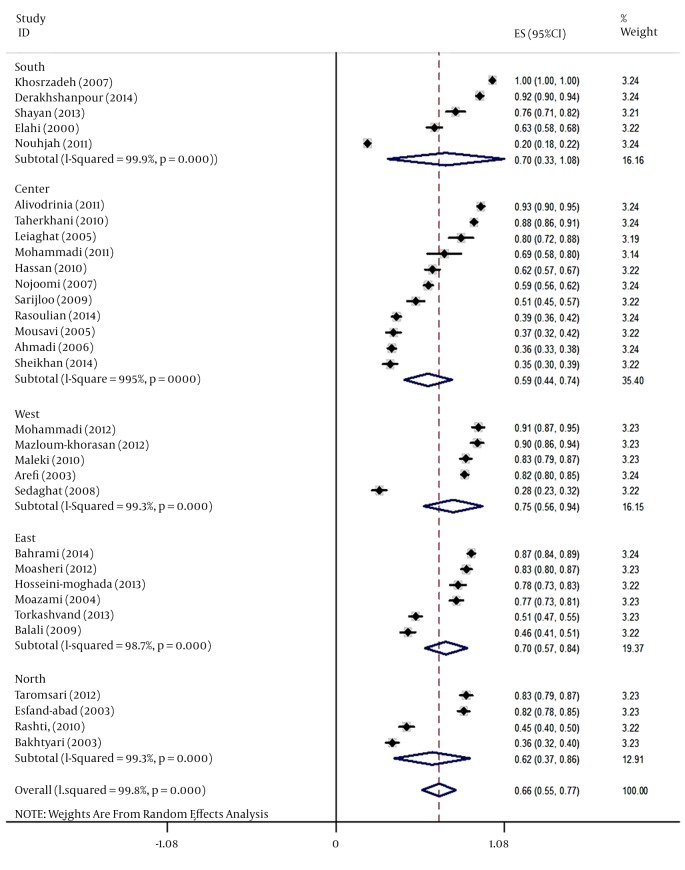

Due to the high heterogeneity of the articles (99.8%), a random effects model was used for further surveys. The model assumed that the differences between the reported results were rooted in the differences in the scores obtained by the subjects and different sampling processes. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran was estimated by the random effects model; it was found to be equal to approximately 66% for the sample size of 15,514 persons (CI 95%: 55 - 77). In terms of geographical classification, the prevalence of domestic violence was calculated as being 70% (CI 95%: 57 - 84) in the east of the country, 70% in the south (CI 95%: 32 - 100), 75% in the west (CI 95%: 56 - 94), 62% in the north (CI 95%: 37 - 86), and 59% in the center (CI 95%: 44 - 74).

Figure 2. The Prevalence of Domestic Violence Based on Geographical Region.

The confidence interval (CI) of 95% for each article is represented by a horizontal line near the main mean line; the dashed line in the middle represents the estimate of the total mean point; and the rhomboid represents the CI 95% of the prevalence of domestic violence.

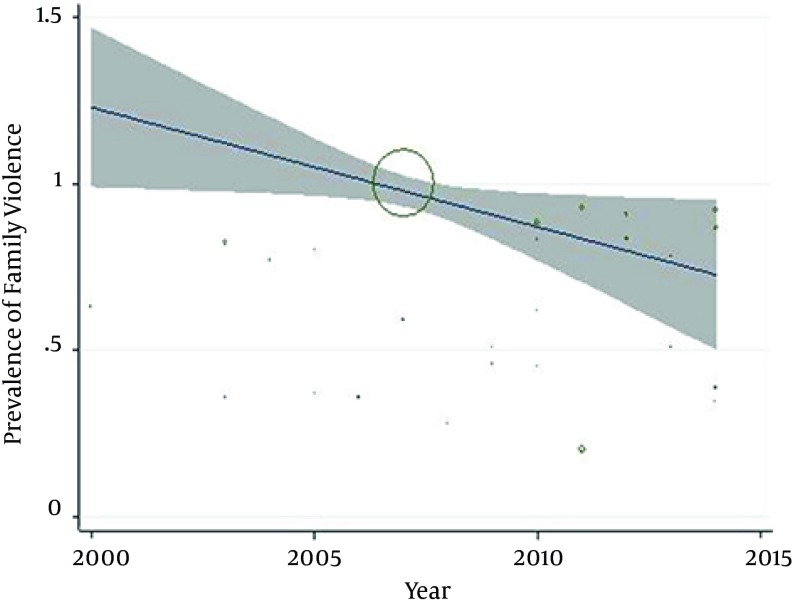

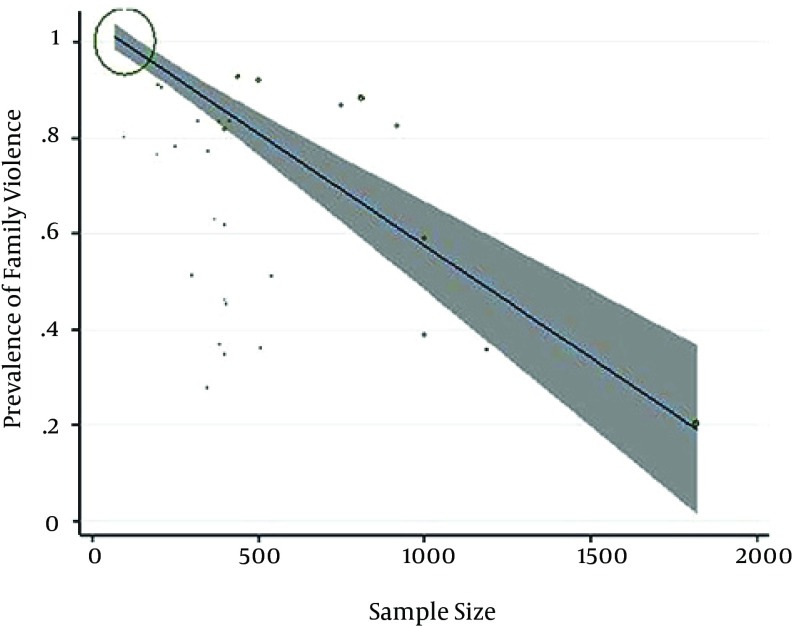

The prevalence of domestic violence was measured based on researcher-designed questionnaires in 11 articles (35.4%), and the data-gathering tool was not mentioned in five articles (16.1%). The meta-regression results showed that there was no relationship between the prevalence of domestic violence and the year of publication of the article (P = 0.554), and there was no ascending trend for the prevalence of domestic violence over time (Figure 3). The meta-regression based on sample size showed that the studies with smaller samples reported a higher prevalence of domestic violence (P = 0.013) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. The Prevalence of Domestic Violence Based on the Year of Publication of the Article.

Figure 4. The Prevalence of Domestic Violence Based on the Study Sample Size.

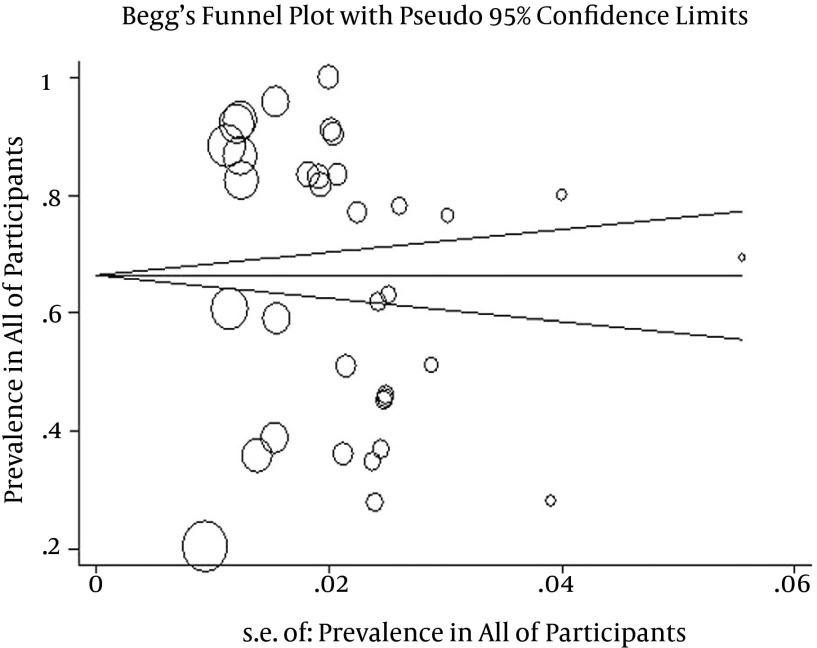

To study publication bias, a funnel plot was used. The results showed that the publication bias in this systematic review and meta-analysis was not significant (P = 0.846) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Funnel Plot of Domestic Violence Against Iranian Women.

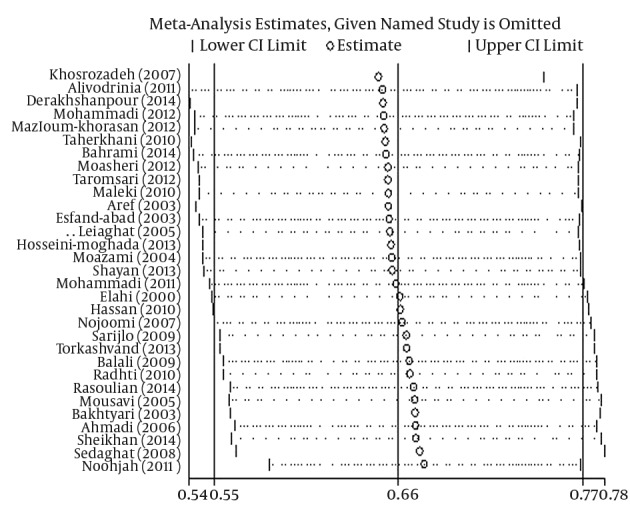

The sensitivity analysis in Figure 6 shows that, by eliminating each study, the overall prevalence did not change significantly.

Figure 6. Sensitivity Analysis.

4. Conclusions

The studies conducted in Iran on the prevalence of domestic violence among Iranian women have reported different results. In the present study, the general estimate of the prevalence of this problem in Iran was 66% (CI 95%: 55 - 77), which is consistent with the results of a national study (44) conducted in 2001 in 28 provinces of the country (66%). A study in Pakistan reported that the prevalence of domestic violence was 69.5%, which is quite close to that of Iran (45). According to UN reports, the prevalence of domestic violence in Belgium, the USA, Norway, New Zealand, South Korea, Colombia, and Guinea is 25%, 28%, 17%, 38%, 20%, 58%, and 67%, respectively (46). Another study by the WHO (2006) of 24,000 women in 10 countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, Japan, Namibia, Peru, Samoa, Serbia and Montenegro, Thailand, and the United Republic of Tanzania) showed that 15% - 71% of the participants were subjected to violence by their husband (47). Reports in the USA and Canada indicated that 34% and 10% of women, respectively, had suffered from domestic violence by their husband or sex partner (38). The results of many studies in different parts of the world have revealed that violence against women is rampant in all countries and across all sociocultural classes. The differences in the reports are due to the varying definitions of domestic violence and the culture and laws in different countries.

Domestic violence is one of the main social-public health and human rights issues that influence women and children’s health. In their meta-analysis study, Niazi et al. (48) (2014) estimated the prevalence of domestic violence against pregnant women in Iran at 48%. Apparently, the prevalence of domestic violence decreases during pregnancy due to sensitivities toward fetus health and legal consequences.

A comparison of the prevalence of domestic violence in different regions of Iran indicated that it is less widespread in the central region (59%) than in the western (75%), southern, and eastern (70%) regions. It has been suggested that several social, economic, and cultural factors may have an effect on the prevalence of domestic violence (49-51). The differences between the various regions in Iran are therefore not surprising given that the Iranian population features high cultural diversity, and the different cultures have distinctive beliefs, attitudes, traditions, values, and norms. Shahabadi and Amini (51) (2010) showed that an increase in domestic violence was more apparent among the Azari, Kurdish, and Fars ethnic groups. In addition, climate change has been noted as having an impact on the prevalence of domestic violence. Rotton (2001) and Ellen (1993) (49, 50) demonstrated that domestic violence is related to temperature changes with the net effect that it is more common in regions with hot weather.

The results of the present research suggest that domestic violence is indeed influenced by climate and cultural factors. It is further assumed that cultural factors can sometimes lessen the impact of climate and reduce levels of domestic violence, even in the tropics. Of course, this issue requires additional study.

The results of the meta-regression indicated that there was no significant relationship between the prevalence of domestic violence and the year of publication of the articles; however, the diagram in Figure 3 shows an ascending trend for the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran although this was not found to be significant. Our results are consistent with the study conducted in 2001 by the Ministry of Interior Affairs in 28 Iranian provinces (13). Contrarily, studies in the USA have indicated that the prevalence of domestic violence has increased over time from 39% to 60% (45). These increasing trends in some countries are in spite of the general technological and educational advances and changes in lifestyle (52). Certainly, some studies in Iran have indicated that poor education and a lack of facilities and welfare standards were among the contributory factors to the emergence of domestic violence (15, 26, 29, 33, 35). Notwithstanding, there may be unknown factors or changes in the known contributory factors over time.

In terms of the limitations of this study, instead of focusing on the whole population, some of the reviewed studies only focused on the women who had been to forensic medicine centers, and consequently the results of these studies could not be generalized. Failure to use checklists to study the methodological quality of the articles included in this study, the varying definitions of violence in the articles, the use of different tools to examine domestic violence, and the victims’ failure to report many instances of domestic violence were among the most important limitations of this study.

Our literature review revealed the absence of studies dealing systematically with domestic violence against Iranian women, and it is therefore vital that such a study be conducted. The most important strength of this study is its accurate estimate of the prevalence of domestic violence against Iranian women, which can be of great help in the design of prevention or intervention programs by health organizations and research centers.

In conclusion, there are no reliable and accurate data and statistics about domestic violence against women in Iran, as in most cases, women tend not to go to legal authorities for reasons such as feelings of guilt or fear of economic hardship, being deserted by their families, loss of social position, rumors, or separation from their children. Due to the high prevalence of domestic violence against Iranian women, early detection of domestic violence and the initiation of intervention programs by health and social services centers may prevent many of the unwanted consequences of this phenomenon. Indeed, delays in the detection of domestic violence impose serious threats to the well-being of women and children. There is additionally a critical need to determine and deal with the factors contributing to the emergence of domestic violence in Iran.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the reviewers for their constructive comments, which improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Design: Hamideh Hajnasiri; data collection: Hamideh Hajnasiri, Farnoosh Moafi, and Mohammad Farajzadeh; analysis and interpretation of data: Kourosh Sayehmiri and Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh; manuscript preparation: Hamideh Hajnasiri and Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh; manuscript revision: Hamideh Hajnasiri and Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support:This study was funded and supported by the department of nursing and midwifery at the Qazvin University of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Bodaghabadi M. Prevalence of violence and related factors in pregnant women referring to Shahid Mobini hospital, Sabzevar. Med J Hormozgan Uni. 2007;11(1):71–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baher B, Ziaei M, Sh ZM. Survey of prevalence domastic violence and relationship Adverse pregnancy outcomes. J School Nur Midwife Hamedan. 2012;20(1):31–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas Zadeh M, Saadati M. Domestic violence, threat against mental health. J Social Security . 2011:61–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmadi B, Alimohamadian M, Golestan B, Bagheri Yazdi A, Shojaeezadeh D. Effects of domestic violence on the mental health of married women in Tehran. J School Public Health Institute Public Health Res. 2006;4(2):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohseni Tabrizi A, Kaldi A, Javadianzadeh M. The study of domestic violence in marrid women addmitted to yazd legal medicine organization and welfare organization. Toloo-e-Behdasht. 2012;11(3):11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aghakhani K, Aghabigloie A, Chehreii A. Evaluation of physical violence by spouse against womens refering to forensic medicine center of Tehran in autumn of 2000. Razi J Med Sci. 2003;9(31):485–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tavassoli A, Monirifar S. Sociological study of the impact of socioeconomic status on violence against women in the marriage. J Family Res. 2009;5(20):441–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.KHadiv Zadeh T, Erfanian F. Comparison of domestic violence during pregnancy with the Pre-pregnancy period and its relating factors. Iran J Obstetric Gynecol Infertil. 2011;14(4):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moasheri N, Miri M, Abolhasannejad V, Hedayati H, Zangoie M. Survey of prevalence and demographical dimensions of domestic violence against women in Birjand. Modern Care J. 2012;9(1):32–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranji A, Sadr khanlo M. The study of domestic violence during pregnancy, their relationship with some demographic factors and the effects on pregnancy outcomes in women referred to health centers in Urmia city. J Women Family Studies. 2012;4(15):107–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sminkey L, Chaib F, Khadka S, Bannerjee P. New study highlights need to scale up violence prevention efforts globally. 2014 Available from: http://wwwwhoint/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/violence-prevention/en/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Mazza D, Dennerstein L, Garamszegi CV, Dudley EC. The physical, sexual and emotional violence history of middle-aged women: a community-based prevalence study. Med J Aust. 2001;175(4):199–201. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghazi Tabatabai M, Tabrizi A, Marjai S. Studies on domestic violence against women. Tehran: Office of public affairs, ministry of interior affairscenter of women and family affairs, presidency of the islamic republic of Iran; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasoulian M, Habib S, Bolhari J, Hakim Shooshtari M, Nojomi M, Abedi S. Risk factors of domestic violence in Iran. J Environ Public Health. 2014;2014:352346. doi: 10.1155/2014/352346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikhan Z, Ozgoli G, Azar M, Alavimajd H. Domestic violence in Iranian infertile women. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014;28:152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghaddam Hosseini V, Asadi ZS, Akaberi A, Hashemian M. Intimate partner violence in the eastern part of Iran: a path analysis of risk factors. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(8):619–25. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.785616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nouhjah S, Latifi M, Haghighi M, Eatesam H, Fatholahifar A, Zaman N. Prevalence of domestic violence and its related factors in women referred to health centers in Khuzestan Province. Journal of Kermanshah university of medical sciences. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2011;15(4):278–86. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardabily HE, Moghadam ZB, Salsali M, Ramezanzadeh F, Nedjat S. Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian setting. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;112(1):15–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nojomi M, Agaee S, Eslami S. Domestic violence against women attending gynecologic outpatient clinics. Arch Iran Med. 2007;10(3):309–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khosravi Zadegan F, Azizi F, Khosravi Zadegan Z, Morvaridy M. Psychological demographic characteristics for violence against women in Bushehr city. South Med J. 2007;10(1):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liaghat G. Domestic violence in family. J Social Sci Faculty Human Sci Ferdowsi Uni Mashhad. 2005;2(2):163–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aliverdinia A, Riahi M, Farhadi M. Social analysis intimate partner violence against women. J Social Isues Iran. 2011;2(2):96–127. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammadi F, Mirzaei R. Effect of Social Factors on violence against women. J Social Studies. 2012;6(1):101–29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taherkhani S, Mirmohammadali M, Kazemnejad A, Arbabi M. Association experience time and fear of domestic violence with the occurrence of depression in women. Iran J Forensic Med. 2010;16(2):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahrami G. Domestic violence on women: Evidence from iran. Asia J Res Social Sci Humanities. 2014;4(5):688–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derakhshanpour F, Mahboobi H, Keshavarzi S. Prevalence of domestic violence against women. J Gorgan Uni Med Sci. 2014;16(1):126–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shayan A, Masoumi Z, Kaviani M. The relationship between wife abuse and mental health in women experiencing domestic violence referred to the forensic medical center of shiraz. J Edu Commun Health. 2015;1(4):51–7. doi: 10.20286/jech-010451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torkashwand F, Rezaeean M, Sheikhfathollahi M, Mehrabian M, Bidaki R, Garousi B. The Prevalence of the types of domestic violence on women referred to health care centers in Rafsanjan in 2012. J Rafsanjan Uni Med Sci. 2013;12(9):695–708. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazloom Khorasani M, Mirzaee M. Domestic Violence against women in khorram abad 2010-2011. J Women's Studies. 2012;10(3):111–38. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahbar Taramsari M, Badsar A, Zobde Imanabadi R, Khajeh Jahromi S, Amir Maafi A, Yaghubi M. Evaluation of physical intimate partner violence in respective victims in Rasht. J Guilan Uni Med Sci. 2012;21(83):21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadi F, Mirzaei M. The study Social factors impact on violence against women in city Rawansar. J Social Studies Iran. 2012;6(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rashti S, Golshokoh F. The relationship between domestic violence and post - tramatic stress disorder among marriad women. J Social Psychol. 2010;5(15):105–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maleki A, Nejad Sabzi P. The relationship between the family social capital with domestic violence against women in khorram abad. J Social Problems Iran. 1(2):32–53. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balali Meybodi F, Hassani M. Prevalence of violence against women by their partners in Kerman. Iran J Psychiatr Clin Psychol. 2009;15(3):300–7. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarichlo M, GHafeledbashi S, Kalantari Z, Moradibegloi M, Jahani hashmi H. Domestic violence against women and Interventions for prevention in Kosar and minodar area. J Uni Med Sci Qazvin. 2009;13(4):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sedaghat K, Zarinian J. Social factors and domestic violence among the families in Tabriz city. J Sociol Studies. 2008;1(1):124–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mousavi SM, Eshagian A. Wife abuse in Esfahan, Islamic Republic of Iran, 2002. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11(5-6):860–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moazzemi S. The criminology of domestic violence and spousal murder in Sistan and Baluchestan. J Women Res. 2004;2(2):39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bakhtiari A, Omidbakhsh N. Backgrounds & effects of domestic violence against women referred to law-medicine center of Babol, Iran. J Kermanshah Uni Med Sci. 2004;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arefi M. Domestic violence against women in Urmia city. J Women's Studies. 2003;1(2):101–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shams Esfand Abad H, Emamipoor S. The study of the prevalence of domestic violence and effective factors its. J Women. 2003;1(5):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elahi N, Alhani F. The frequency of misbehavior with married women referred to health centers in Ahwaz and its related factors. Jundishapur Med J. 2000;5(8):477–87. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Health . National research study of domestic violence against women in 28 centers in the country. Tehran: Ministry of Social Affairs; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haqqi S, Faizi A. Prevalence of domestic violence and associated depression in married women at a tertiary care hospital in karachi. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2010;(5):1090–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.WHO . Multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women. Geneve: Department of gender and women's health, family and community health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1260–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niazi M, Kassani A, Menati R, Khammarnia M. The prevalence of domestic violence among pregnant women in iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sadra Med Sci J. 2015;3(2):139–50. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohn EG. The prediction of police calls for service: The influence of weather and temporal variables on rape and domestic violence. J Environmen Psychol. 1993;13(1):71–83. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80216-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rotton J, Cohn EG. Temperature, routine activities, and domestic violence: a reanalysis. Violence Vict. 2001;16(2):203–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shahabadi A, Amimi K. The impact of ethnicity on violence against women in Tekab city. J Order Security Police. 2010;1(3):55–78. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horne S. Domestic violence in Russia. Am Psychol. 1999;54(1):55–61. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]