Abstract

Hypoxia and inflammation are implicated in the episodic induction of heterotopic endochondral ossification (HEO); however, the molecular mechanisms are unknown. HIF-1α integrates the cellular response to both hypoxia and inflammation and is a prime candidate for regulating HEO. We investigated the role of hypoxia and HIF-1α in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), the most catastrophic form of HEO in humans. We found that HIF-1α increases the intensity and duration of canonical bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling through Rabaptin 5 (RABEP1)-mediated retention of Activin A receptor, type I (ACVR1), a BMP receptor, in the endosomal compartment of hypoxic connective tissue progenitor cells from patients with FOP. We further show that early inflammatory FOP lesions in humans and in a mouse model are markedly hypoxic, and inhibition of HIF-1α by genetic or pharmacologic means restores canonical BMP signaling to normoxic levels in human FOP cells and profoundly reduces HEO in a constitutively active Acvr1Q207D/+ mouse model of FOP. Thus, an inflammation and cellular oxygen-sensing mechanism that modulates intracellular retention of a mutant BMP receptor determines, in part, its pathologic activity in FOP. Our study provides critical insight into a previously unrecognized role of HIF-1α in the hypoxic amplification of BMP signaling and in the episodic induction of HEO in FOP, and further identifies HIF-1α as a therapeutic target for FOP and perhaps non-genetic forms of HEO.

Keywords: Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, Preclinical studies, Cell/tissue signaling

Introduction

Heterotopic endochondral ossification (HEO) - the transformation of skeletal muscle and soft connective tissue into mature lamellar bone through an obligate cartilaginous template - occurs sporadically in response to trauma, or by genetic mutation in the rare, disabling autosomal dominant disorder, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP; MIM 135100).(1,2) FOP is caused by a recurrent heterozygous activating mutation of activin receptor A, type I/activin-like kinase 2 (ACVR1/ALK2; referred hereafter as ACVR1), a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor, in all individuals with classic FOP.(3) The canonical FOP mutation and all of the genetic variants reported in humans exhibit loss of autoinhibition of BMP signaling.(4,5) Regulated feedback in BMP type I receptors is required for the spatial and temporal modulation of BMP signaling.(6)

Despite the occurrence of germline activating mutations of ACVR1 in all FOP patients, individuals with FOP do not form bone continuously, but rather episodically and often following trivial injury, a finding that suggests that trauma-related triggers induce tissue metamorphosis in the setting of altered micro-environmental thresholds.(7) FOP flare-ups are predictably associated with inflammation(1), a well-known cause of tissue hypoxia.(8)

Hypoxia, the principal trigger of cellular oxygen sensors, prolongs the activation of cell surface protein kinase receptors by decelerating their endocytosis and degradation.(9) BMP receptors are cell surface protein kinases whose signaling and degradation are mediated, in part, by distinct endosomal pathways, a finding that has profound implications for their morphogenetic function.(6,9–12) Signaling can be modulated by targeting active receptors for degradation or by dysregulating trafficking of receptors through the endocytic pathway.(12,13)

The molecular response to hypoxia is controlled by the HIF family of heterodimeric transcription factors, comprised of the subunits HIF-1α and HIF-1β. HIF-1β is constitutively expressed and stable. HIF-1α, in contrast, is oxygen sensitive and targeted for ubiquitin-mediated degradation to experimentally undetectable levels following oxygen-dependent prolyl-hydroxylation.(14) In hypoxia, prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) are inactivated; HIF-1α escapes hydroxylation, is stabilized, rapidly accumulates in the nucleus, recruits HIF1-β, and binds to the penta-nucleotide hypoxia-responsive elements of target genes to regulate glycolysis, cell survival, cell reprogramming, inflammation, and angiogenesis.(9,15) HIF-1α and HIF-2α are closely related and activate HRE-dependent gene expression, sharing several common targets, such as VEGF, but also regulating distinct transcriptional targets that may require unique transcriptional cofactors.(16) HIF-1α is expressed ubiquitously, whereas HIF-2α expression is more limited. Both HIF proteins appear to play non-redundant roles in the development and in cancer cells have differential effects on c-Myc activity.(16)

Stabilization of HIF-1α occurs as an adaptive response to inflammation or hypoxia.(8) Post-translational stabilization of HIF-1α (by a tissue specific knockout of the von Hippel-Lindau gene) is sufficient to drive ectopic chondrogenesis in mouse models.(17–19) Although dysregulated BMP signaling causes robust HEO, the relationship between tissue hypoxia and BMP signaling in the pathogenesis of HEO is unknown.

We speculated that the inflammatory microenvironment of early FOP lesions might be hypoxic. We further reasoned that molecular oxygen sensing during hypoxia might enhance BMP signaling in FOP by stimulating retention of mutant ACVR1 (mACVR1) [serine-threonine kinase] receptors in signaling endosomes similar to that which occurs with the mutant EGF (tyrosine kinase) receptors under hypoxic conditions during oncogenesis.(9,20) To test this hypothesis, we evaluated early murine and human FOP lesions for evidence of tissue hypoxia and HIF1-α stabilization and then examined the effect of hypoxia on BMP ligand-independent ACVR1 (R206H) activity in primary chondro-osseous progenitor cells from FOP patients and controls. We found that early inflammatory FOP lesions were profoundly hypoxic and that hypoxia not only increased the intensity but also prolonged the duration of BMP ligand-independent signaling through a HIF-1α mediated mechanism that retained ACVR1 in signaling endosomes. The endosomal retention of ACVR1 under hypoxia was caused by HIF-1α transcriptional down-regulation of RABEP1 which encodes Rabaptin 5, a neoplastic tumor suppressor gene that interacts to modulate Rab5, a small GTPase that plays a critical role in endocytic trafficking.(9,20,21) We further determined by both genetic and pharmacologic means that attenuation of cellular oxygen sensing restored BMP signaling to normoxic levels in FOP cells and abrogated HEO in a Acvr1Q207D/+ mouse model of FOP.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples

Specimens from six FOP patients who underwent biopsy for presumptive neoplasm prior to the definitive diagnosis of FOP were obtained from superficial and deep back masses later determined to be acute, early FOP lesions. To our knowledge, this sample size represents all of the available biopsy tissue for this ultra-rare disease. Normal muscle tissue was obtained from the corresponding anatomic sites of four age-and gender-matched unaffected individuals. Specimens were also obtained from 8 patients with non-hereditary HEO due to trauma and spinal cord injury.

Tissue preparation and staining

Tissue samples were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, decalcified, infiltrated, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at a thickness of 5 µm. Cut samples were deparaffinized, stained with Harris hematoxylin solution and counterstained with eosin (H&E) by standard procedures. All stained slides were examined under light microscopy for histological characteristics of FOP lesion formation.(22) Distinct cellular elements/tissue types in the same section were confirmed by two independent examiners (R.J.P. and F.S.K.).

Animal models

A transgenic mouse model containing a constitutively active (ca)ACVR1 allele flanked by loxP sites (caACVR1 mice) was used in all animal experiments.(23,24) A 50 µl, 0.9% NaCl solution containing adenovirus-Cre [5×1010 genome copies (GC) per mouse; Penn Vector Core, University of Pennsylvania] to induce expression of caACVR1 and cardiotoxin (100 µl of a 10 µM solution; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to induce an injury/inflammatory response was injected into the hindlimb musculature of mice at 3 weeks of age. Tissues were recovered at 0, 2, 7, and 14 days after injections.

Mice were bred in an animal biosafety level (ABSL) 1 facility then transferred to an ABSL2 facility where procedures were performed. Mice were housed as 1 or 2 mothers with litters and then separated at weaning into cages of no more than 5 males or 5 females. Both males and females were used for experiments. Other aspects of animal care and usage (e.g., light/dark cycle) were standard and performed by University Laboratory Animal Resources (ULAR) in accordance with ULAR policies and protocols.

Chondrogenesis pellet assay

Control or FOP stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) were centrifuged in conical bottom 96 well plates. Formed pellets were cultured in chondrogenic media (CM) containing α MEM, 1% ITS Premix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), 50 mg/ml L-proline, 0.1 mM dexamethasone, 0.9 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 mg/ml ascorbate, and antibiotics (PenStrep, Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) or CM plus100ng/ml BMP4 for 14 days. Pellets were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 µm thick) were deparaffinized in a graded series of ethanol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Safranin O, Alcian Blue (pH 1.0), and immunohistochemically with collagen type II α (col2α) [(#ab34712, ABCAM, Cambridge, MA]. Image J software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) was used to quantify pellet size and the ratio of extracellular matrix area to cellular area.

Lentivirus infection of SHED cells

Human rabaptin 5 cloned into the lentiviral expression vector pReceiver-Lv105 (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD) was used to generate lentivirus particles assembled in HEK293T cells. Lentiviral particles were then used for polybrene-mediated transduction using standard protocols. Two days after infection, control or FOP SHED cells were exposed to 1% O2 for 2 hours and then protein extracted for western blot analysis.

Adenovirus-Cre induction of MEFs

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from conditional LoxP HIF1-α mice (HIF-1αfl/fl MEFs)(18) were infected at a multiplicity of infection (M.O.I.) of 100, with either Ad5CMVcre or Ad5CMVGFP (Penn Vector Core, University of Pennsylvania), three successive times over a 72-h period. The addition of the former, but not the latter, results in the induced deletion of floxed HIF-1α in MEFs.

In vivo testing of HIF-1α inhibitors

caACVR1 mice were treated via gavage with either 25 mg/kg of apigenin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a vehicle containing 0.5% methyl cellulose and 0.025% Tween 20 twice daily, 200 mg/kg of Imatinib (SelleckBio, Houston, TX) suspended in deionized water twice daily, or with 10 µl/g of vehicle containing 0.5% methyl cellulose and 0.025% Tween 20 twice daily. For treatment with PX-478 (Bioorbyt, Berkeley, CA), daily doses of 50 mg/kg and 100mg/kg in phosphate-buffered saline were given via intraperitoneal injection. Mice were treated for 4 days prior to and 14 days following induction of injury and recombination as described above. Mice were sacrificed 14 days after injection with adenovirus-Cre/cardiotoxin, when 100 percent of animals reproducibly form HEO at the injection site. Animals were randomly assigned to the control or treatment groups in an unblinded fashion.

Functional wire grasp test

Mobility in the left hind limb of caACVR1 mice was assessed by observation of their ability to grasp a wire using all four limbs. Unimpaired mice grasp the wire with all four limbs (simultaneously) while mice with impaired mobility of a joint can only grasp the wire with three limbs simultaneously.

Micro-computerized tomography

Micro computerized tomography (µCT) was performed on legs from caACVR1 mice obtained 14 days after adenovirus-Cre/cardiotoxin injection using a Scanco VivaCT 40 device (Bruettisellen, Switzerland) to determine the volume of heterotopic bone and obtain a two-dimensional image of the medial sagittal plane of each limb. Scanning was performed using a source voltage of 55 kV, a source current of 142 µA, and an isotropic voxel size of 10.5 µm. Bone was differentiated from “non-bone” by an upper threshold of 1000 Hounsfield units and a lower threshold of 150 Hounsfield units.

FKBP12 binding analysis

FKBP12 binding analysis was performed essentially as described.(25) Briefly, total protein was isolated and quantified as per Western blot analysis. Immunoprecipitation was carried out using 500 µg protein from each sample and 2 µg ACVR1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) with incubation at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with 30 µl of Protein A/G agarose beads (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Waltham, MA) at 4°C for 1 hour and centrifugation at 800×g for 5 minutes. The immunoprecipitated complex was dissociated by 12% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting performed using FKBP12 antibody (N19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.).

Cell culture, RNA isolation and real-time PCR, Western blot analysis, Iimmunocytochemistry, Flow Cytometry

Details of these standard procedures can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used with one or more of the following factors: genotype, oxygen tension, drug treatment. The Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons was used for post-hoc analyses. Based on the estimated variability in the amount of HEO formed by caACVR1 mice under induction conditions, setting α= 0.05, and β= 0.20 (power of 0.80), a minimum of 8 mice per experimental group were used to test the effectiveness of HIF-1α inhibitors on HEO formation. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (San Diego,CA,USA). The number of experimental (biological) replicates is indicated in the figures or figure legends, and for each biological replicate three in vitro technical replicates were evaluated. Within experiments, variance was similar between comparison groups and data met the assumptions of the statistical tests. An adjusted p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M).

Study Approval

Collection of specimens and mechanism of informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania. Animal use was in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Results

Early inflammatory and pre-chondrogenic FOP patient lesions are hypoxic

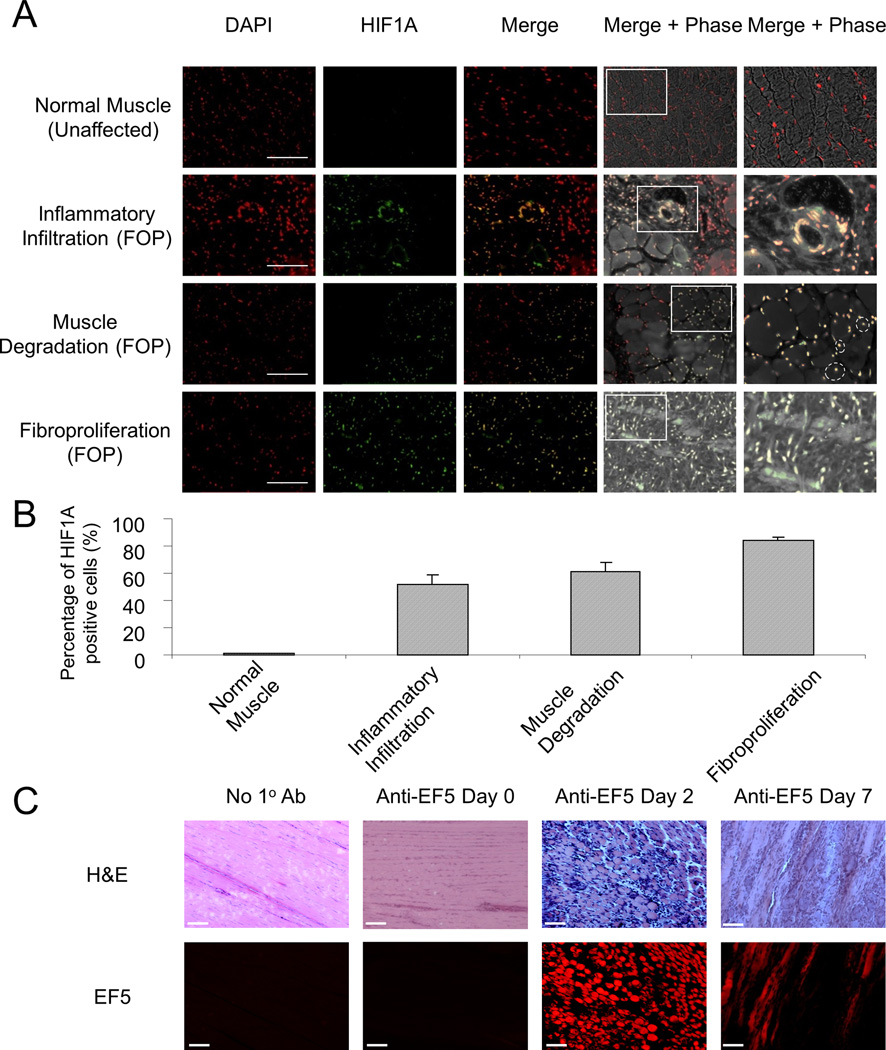

Lesion formation in FOP often occurs as the result of subtle soft tissue trauma; therefore, biopsies are not obtained after a diagnosis is made. However, rare glimpses into the histopathology of early lesions have been afforded by misdiagnoses of FOP. The earliest stages are composed of perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, muscle degeneration, and fibroproliferation.(22) We evaluated the hypoxic response in early FOP lesions from six FOP patients who underwent diagnostic biopsy for presumptive neoplasm prior to the correct diagnosis of FOP. Nuclear localization of HIF-1α was present in pre-chondrogenic FOP lesions, indicative of a hypoxic response in multiple cells types including inflammatory, endothelial, muscle, and fibroproliferative cells (Fig. 1, a and b). This response is not detectable in normal muscle tissue from unaffected individuals. In addition, we evaluated 13 distinct lesions from 8 patients with non-hereditary HEO due to trauma and spinal cord injury. All but one lesion (12/13) showed mature heterotopic bone with bone marrow, likely reflecting surgical bias to remove fairly mature HEO. One lesion showed predominant evidence of slightly less mature bone with cartilage bar remnants. Two lesions showed at least one area of inflammation and fibroproliferation (but no cartilage). We performed HIF1-α immunohistochemistry on the latter two samples, and consistent with our findings in early FOP lesions, these also show evidence of HIF1-α nuclear staining in immature areas of lesion formation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Injury triggers hypoxia in early FOP lesions. (A) Nuclear localization of HIF-1α by immunohistochemistry in tissues sections from unaffected individuals (n = 4) and those with FOP (n = 6). Magnified images of the indicated regions of interest are shown in the right-most panels. Scale bar, 50 µm. Dashed circles delineate centralization of nuclei in degenerating muscle. (B) Quantification of HIF-1α positive cells from normal human muscle and stage-specific early FOP lesional tissue, expressed as the percentage of cells with nuclear HIF-1α (DAPI and HIF-1α co-localization). (C) Identification of hypoxia in early FOP lesions induced by Adenovirus-Cre and cardiotoxin in a caACVR1 FOP-like mouse model (n = 3). The no 1° antibody (negative) control was performed on lesional tissue seven days after injury. Scale bar = 100 µm.

Although the availability of antibodies with adequate specificity against murine HIF-1α precluded us from conducting the same analysis in a mouse model of HEO, we detected EF5, a pentafluorintated derivative of etanidazole and a marker of hypoxic cells, to examine hypoxia in early stage lesions that were induced by adenovirus-Cre and cardiotoxin in mice constitutively active for ACVR1 (caACVR1), a murine model of FOP-like heterotopic ossification.(23,24,26) The presence of EF5 in areas of inflammation and fibroproliferation in day 2 and day 7 pre-chondrogenic lesions, respectively, indicated that hypoxia was associated with the same pathological stages that demonstrate a hypoxic response in lesional tissue from FOP patients (Fig. 1c).

Since HIF-1α is ubiquitously expressed, including in early FOP lesions, and its function in the hypoxic response is better understood, we focused on its role in BMP signaling. We cannot exclude a role for HIF-2α in this process.

The response to hypoxia in chondro-osseous progenitor cells is regulated by the BMP signaling pathway

Hypoxia inhibits prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), thus activating HIF1-α. In SHED cells, a Tie2+ chondro-osseous progenitor cell population,(27) hypoxia caused HIF1A nuclear translocation and enhanced expression of HIF1-α target genes (Supplementary Fig. 2). SHED cells represent a powerful in vitro model for studying FOP because Tie2+ mesenchymal stem cells have been implicated in developing lesions, they are easily derived from exfoliated primary teeth in a non-invasive manner that avoids FOP exacerbations, and they reflect the identical stoichiometry and genomic location of FOP mutations. We tested the hypothesis that tissue hypoxia enhances BMP signaling through mACVR1 using SHED cells isolated from FOP patients and unaffected, age- and gender-matched individuals. Prior to choosing SHED cell strains for use in experiments, we conducted an analysis of ten strains (five FOP and five control) for Inhibitor of Differentiation 1 (ID1) mRNA expression under normoxic conditions. We chose representative cell strains based on the median ID1 expression in each group and then used multiple SHED cell isolates from these representative samples to conduct future experiments. The variability in ID1 expression seen among SHED cell strains was similar to what we have seen in other cell models used to study FOP, including lymphoblastoid cell lines; therefore, to minimize variability in SHED cells strains based on the heterogeneous nature of donors, we conducted all experiments using SHED cells that expressed the median ID1 expression among FOP and control (unaffected) donors. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows the distribution of ID1 expression among all the SHED cell strains.

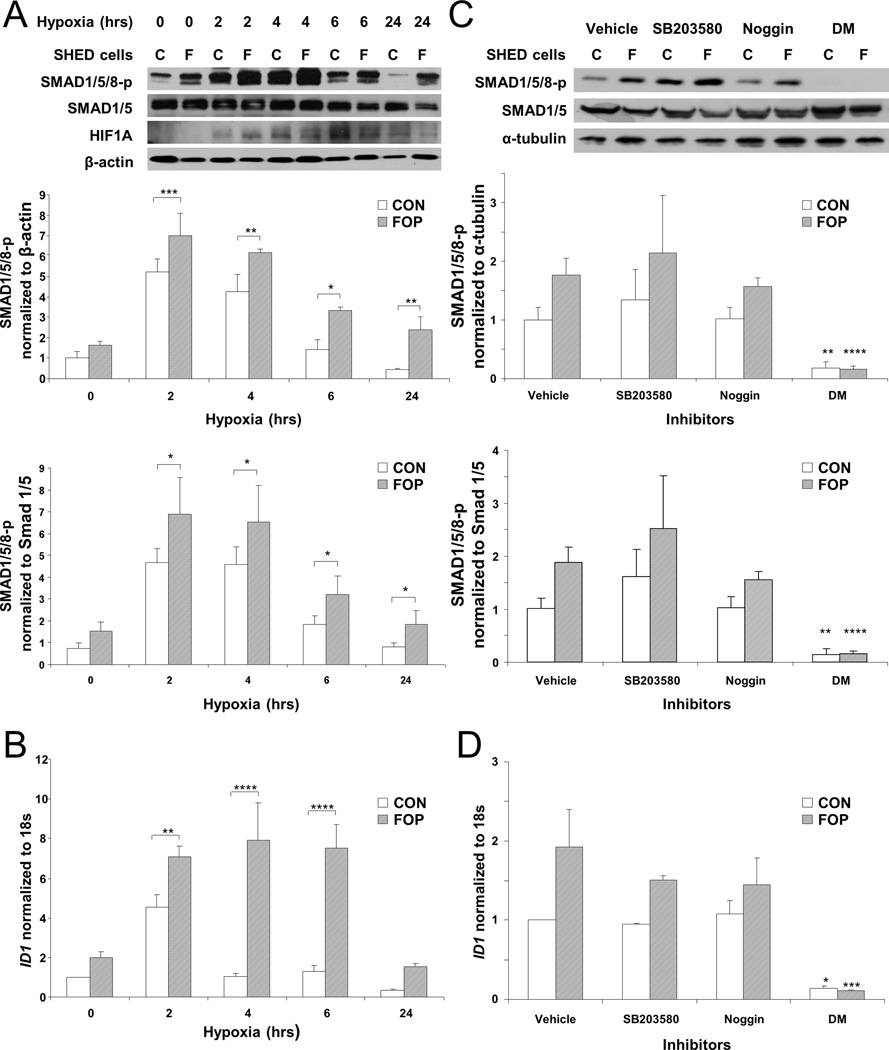

FOP and control SHED cells responded to hypoxia by elevated levels of SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation and ID1 mRNA after two hours (Fig. 2, a and b). SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation and ID1 mRNA expression were significantly elevated in FOP cells compared to control cells. FOP SHED cells continued to manifest elevated SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation and ID1 mRNA levels after 24 and 6 hours, respectively, while control SHED cells at these later time points had levels of ID1 mRNA comparable to normoxic conditions (Fig. 2, a and b). We also examined MSX2 mRNA expression as an additional target of BMP signaling and obtained results similar to that with ID1 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Using cobalt as a hypoxia mimetic recapitulated the effects of hypoxia on BMP ligand-independent signaling in SHED cells (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 2.

The BMP signaling pathway is regulated by the cellular response to hypoxia. (A) SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation in SHED cells under hypoxia. SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation and HIF-1α were detected by Western blot analysis after the indicated number of hours under hypoxia (n = 5). (B) Relative ID1 expression in SHED cells under hypoxia. ID1 levels were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to 18s RNA (n = 3). (C) Dorsomorphin, but not Noggin or p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, mitigates SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation in SHED cells under low oxygen conditions. SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation was detected by Western blot analysis after two hours under hypoxia. Noggin was used at 400ng/ml (n = 3). (D) ID1 expression induced by hypoxia in SHED cells is inhibited by Dorsomorphin, but not Noggin or p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. ID1 levels were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to 18s RNA (n = 3). C, Unaffected controls; F, FOP. Genotype and hypoxia, as well as genotype and drug inhibition, are significantly related to SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation and ID1 expression by 2-way ANOVA (p < 0.0001). Bonferroni post-hoc analysis: ****, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

Although these experiments were performed in serum-free media in the absence of exogenous BMP, we confirmed that hypoxia-induced, enhanced early signaling through mACVR1 is BMP ligand-independent by measuring SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation after treatment of SHED cells with Noggin. Fig. 2 (c and d) shows that Noggin did not mitigate ACVR1 signaling under hypoxic conditions, in cells expressing mACVR1 or in control cells. However, mACVR1 hypoxia-mediated signaling was abrogated by Dorsomorphin, a BMP type I receptor inhibitor (Fig. 2, c and d) as well as LDN-193189, a selective inhibitor of BMP type I receptor kinases (Supplementary Fig. 6). Similarly, hypoxia-induced ID1 expression was minimized by Dorsomorphin. The p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 did not affect signaling (Fig. 2, c and d). Previous studies have shown that treatment of SHED cells with inhibitors of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and inhibitors of c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) had no effect on ID1 expression.(27)

Given these results, it is unlikely that enhanced BMP signaling under hypoxia is due to modulation of soluble BMP inhibitors, findings supported by our previous report.(27) We also examined a possible role of FKBP12, a protein which is required to maintain the ACVR1 receptor kinase in an auto-inhibited state until activated by ligand. mACVR1 exhibited lower FKBP12 binding in response to hypoxia compared to wild-type receptor (Supplementary Fig. 7), and may in part account for BMP ligand-independent signaling under hypoxia.

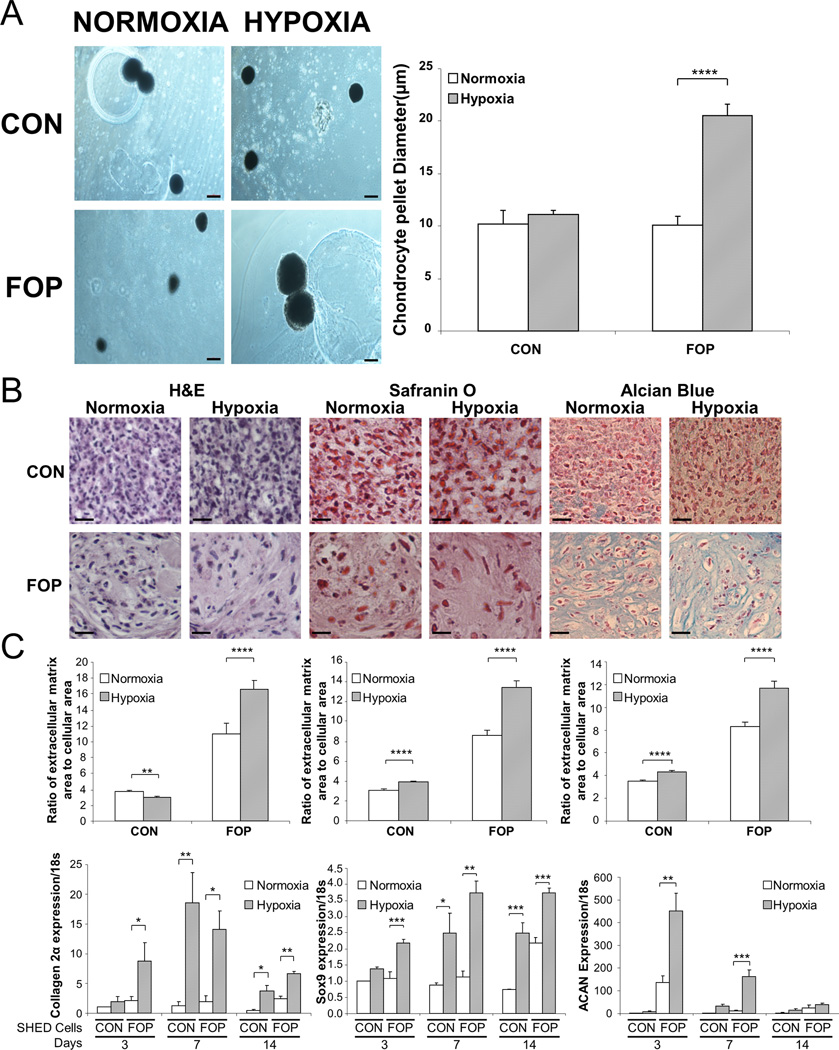

Hypoxia promotes chondrogenesis through BMP signaling

We used SHED cells as a surrogate model system to assess the obligate, pre-osseous chondrogenic phase of HEO in FOP. We evaluated the ability of mACVR1 to promote chondrogenesis in the absence of BMP and demonstrated that FOP SHED cells, relative to control SHED cells, had an enhanced capacity to differentiate into chondrocytes under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3). This was demonstrated by the nearly two-fold larger size of chrondrocyte pellets produced by FOP SHED cells under hypoxia compared to control SHED cells or to FOP SHED cells under normoxic conditions (Fig. 3a), and was reflected in the greater amount of chondrocyte extracellular matrix produced by hypoxic FOP SHED cells (Fig. 3b). Chrondrocyte differentiation in pellets derived from SHED cells was further confirmed by the up-regulation of chrondrocyte markers collagen 2α, Sox9, and aggrecan (ACAN) under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3c). Production of col2α is also enhanced by the addition of BMP to control cells, and even more so by addition to FOP cells (Supplementary Fig. 8), consistent with the idea that the combination of hypoxia and increased BMP signaling (via ACVR1 R206H mutation) could be driving what is seen in FOP chondrocyte pellets. These results were not accounted for by increased proliferation of FOP SHED cells under hypoxic conditions since there were about 30–50% as many cells per unit area in chondrocyte pellets derived from FOP SHED cells compared to controls (53 ± 8 to 74 ± 11 cells/104µm versus 148 ± 22 to 161 ± 23 cells/104µm).

Figure 3.

mACVR1 enhances chondrogenesis of SHED cells under hypoxia. (A) Representative chondrocyte pellets and quantification of chondrocyte pellet size under the indicated conditions (n = 6). Scale bar = 1 mm. (B) Histological appearance and quantification of extracellular matrix showing enhanced chondrocyte differentiation (n =3). Scale bar = 100 µm. (C) Up-regulation of chondrocyte markers COL2A1, Sox9, and aggrecan (ACAN) in SHED cells under hypoxic conditions (n = 3). Genotype and hypoxia are significantly related to pellet size and chondrocyte extracellular matrix by 2-way ANOVA (p < 0.01; interaction, p < 0.01). Post-hoc analysis: ****, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

Hypoxia promotes BMP signaling by retention of ACVR1 in the endosomal pathway

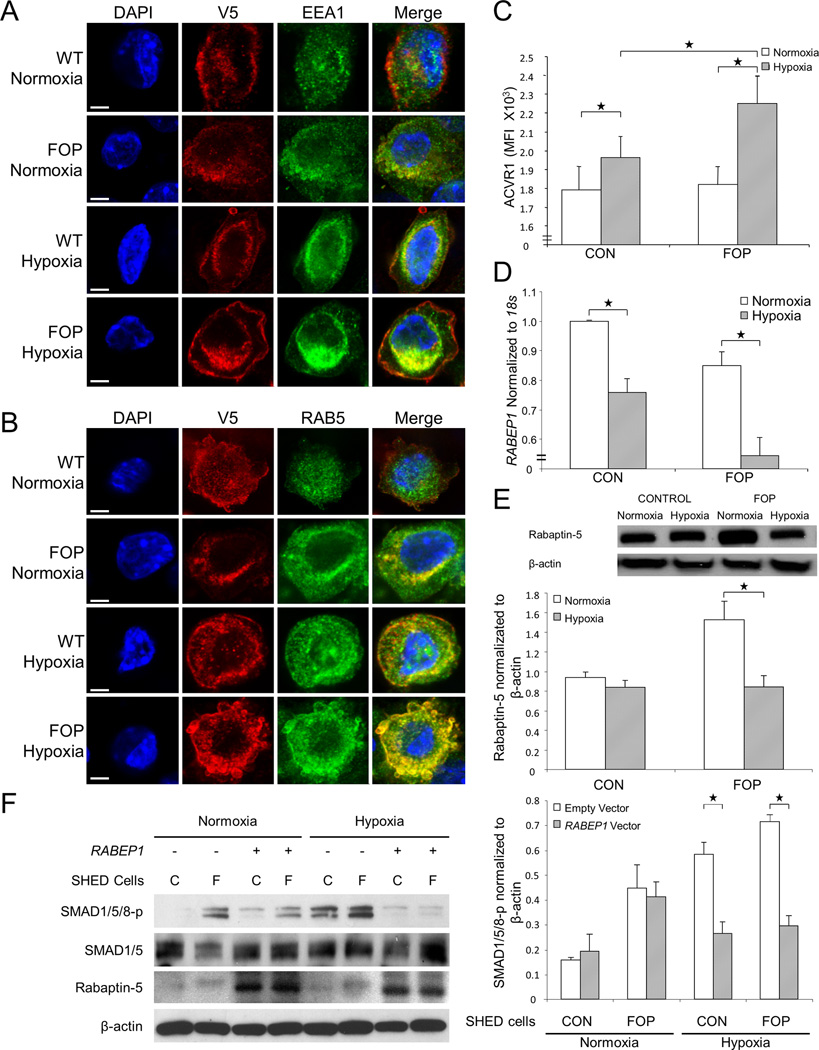

Rabaptin 5 is a direct effector of Rab5 in endocytic membrane fusion. Since hypoxia causes Rabaptin 5 inhibition leading to prolonged endosomal trafficking of EGF receptors through association with Rab5,(9) we investigated whether hypoxia also altered Rabaptin-5 mediated endosomal retention of mutant or wild-type ACVR1. In C2C12 cells expressing V5-tagged wild-type or mACVR1, we found that hypoxia enhanced retention of mACVR1 in endosomes identified by the markers Rab5, EEA1 (Fig. 4, a and b), and the transferrin receptor (Supplementary Fig. 9). Supplementary Fig. 10 quantifies the greater endosomal co-localization of V5-labeled mACVR1 under hypoxia compared to either wild-type ACVR1 or cells under normoxic conditions. Under hypoxia, cell surface ACVR1 receptor density is significantly higher compared to normoxia, and this increase is also intensified with FOP (Fig. 4c). Flow cytometry histograms for each genotype-oxygen tension group are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

Figure 4.

Hypoxia promotes enhanced endosomal retention and BMP ligand-independent signaling of mACVR1. V5-tagged wild-type and mACVR1 is localized to (A) EEA1-positive endosomes and (B) RAB5-positive endosomes on C2C12 cells (n = 9). Scale bar = 10 µm. (C) There is an increased number of cell surface-bound mACVR1 on SHED cells under hypoxic conditions (n = 9). RAB5 mRNA [RABEP1] (D) and RAB5 protein (E) levels were decreased under hypoxic conditions, to a greater extent in FOP SHED cells compared to controls (n = 3). (F) Exogenous expression of Rabaptin 5 in FOP SHED cells decreases BMP signaling in the absence of ligand (n = 2). C, Control; F, FOP. (G) Quantification of Western blot in panel f. Genotype and hypoxia are significantly related to ACVR1 and RAB5 mRNA (RABEP1) as well as to Rabaptin-5 by 2-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis: ****, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

Both Rabaptin 5 mRNA (RABEP1) and protein levels were decreased under hypoxic conditions, greater in FOP SHED cells than in WT SHED cells (Fig. 4, d and e). Since BMP signaling occurs within endosomes,(28) and we found that the ACVR1 receptor is retained in endosomes under hypoxic conditions, we performed a rescue experiment to determine whether Rabaptin 5 decreased BMP signaling in the absence of exogenous BMP ligand. When Rabaptin 5 was exogenously expressed in FOP SHED cells, BMP signaling was markedly decreased to normoxic levels (Fig. 4, f and g), confirming that hypoxia-mediated signaling occurred through ACVR1 in the absence of exogenous BMP ligand and was the result of altered endosomal retention of ACVR1.

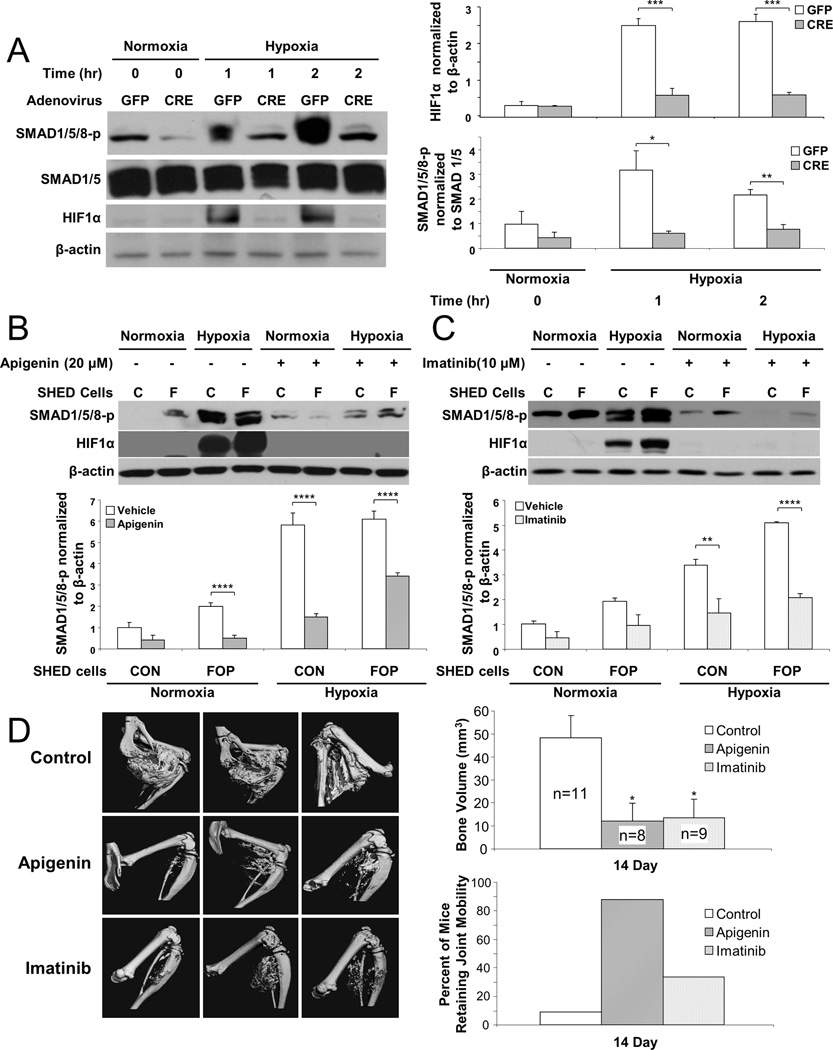

Inhibition of HIF-1α abrogates BMP ligand-independent signaling and heterotopic ossification in a mouse model of FOP

We used complementary genetic and chemical inhibitor approaches to confirm the role of hypoxia in BMP ligand-independent signaling. Adenovirus-Cre induced deletion of floxed HIF-1α in MEFs, but not adenovirus-GFP (negative control), resulted in significantly reduced levels of SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation (Fig. 5a). Similarly, using three potent HIF1-α inhibitors, two currently available agents (apigenin and imatinib)(29,30) and another highly specific agent but in early clinical trials (PX-478),(31,32) BMP ligand-independent signaling was blocked. Of note, and to our knowledge, HIF-1α is the only molecular target shared by all three inhibitors. Thus, genetic deletion or chemical inhibition of HIF-1α in MEFs or SHED cells, respectively, prevented BMP ligand-independent signaling by hypoxia.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of HIF-1α abrogates BMP ligand-independent signaling and heterotopic ossification in a FOP mouse model. (A) Adenovirus-Cre induced deletion of HIF-1α in wild-type MEF cells markedly reduces SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation (n = 3). (B) Apigenin or (C) imatinib blocks BMP ligand-independent signaling in vitro (n = 3). (D) Apigenin or imatinib effectively reduces HEO and improves joint mobility in a caACVR1 FOP-like mouse model. Hypoxia and HIF-1α inhibition are significantly related to SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation and HEO by ANOVA (p < 0.01; interaction, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis: ****, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

Figure 5 (b and c) and Supplementary Fig. 12 show that each inhibitor significantly reduced hypoxia-mediated SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation in both control and FOP SHED cells. Two potent, clinically available, and non-toxic HIF1-α inhibitors (apigenin and imatinib) were subsequently tested in a caACVR1 mouse model of FOP and found to markedly reduce the formation of HEO (Fig. 5d) and decrease the functional limitation about affected joints (Fig. 5d). PX-478 also markedly reduced HEO in the caACVR1 mouse model (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Discussion

The response to tissue hypoxia is a critical regulatory signal in embryogenesis, wound healing, and oncogenesis; however, its mechanism of action in the pathophysiology of heterotopic bone formation is unknown.(8,9,17,20,33–35) We found that early FOP lesions are profoundly hypoxic. Our data support that the cellular response to hypoxia in FOP connective tissue progenitor cells up-regulates and prolongs BMP signaling through HIF-1α repression of Rabaptin5-mediated early endosome fusion, which regulates endosomal retention of BMP receptors.

The resultant retention of mACVR1 in the signaling endosomes amplifies and prolongs dysregulated BMP signaling and stimulates HEO in an animal model of FOP. Rabaptin-5 over-expression or HIF-1α inhibition in vitro restores BMP signaling to normoxic baseline levels in FOP cells while inhibition of HIF-1α in vivo profoundly inhibits HEO and joint immobilization, the most debilitating features of FOP. Thus, we provide evidence for a connection between endosomal retention of mACVR1under hypoxic conditions and a general increase in BMP signaling (Fig. 4).

Endosomal retention of mACVR1 appears to be a major contributor to hypoxia-mediated BMP signaling. We previously reported that FOP cells fail to properly internalize BMP receptors,(10) and our results showing an increase in cell surface labeling of ACVR1 on FOP cells due to a block in endosomal transport is consistent with our previous findings. Compared to wild-type receptor, mACVR1 displays lower FKBP12 binding under hypoxic conditions, suggesting that basal (BMP ligand-independent) activity in hypoxia is in part related to direct receptor kinase inhibition. Although it is unclear if endosomal retention of ACVR1 directly mediates increased cell surface expression of the receptor as well as its decreased FKBP12 binding, this is supported by the effective abrogation of BMP signaling after introduction of exogenous rabaptin-5 into SHED cells.

Previous studies have shown that the cellular response to hypoxia plays a critical role in regulating progenitor cell function and facilitates the reprogramming process,(36–39) in part through dysregulation of BMP signaling.(40–42) This finding is consistent with the reprogramming activity previously demonstrated in the early FOP lesional microenvironment.(40) Importantly, the response to hypoxia also promotes cancer cell survival in tumor formation. Recent studies have identified somatic gain-of-function mutations in ACVR1 in about a quarter of cases of the childhood brainstem tumor diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPGs).(43–46) This intriguing finding suggests that dysregulated BMP signaling may also confer protection against cell death in a hypoxic microenvironment. Although ACVR1mutation-positive cases were associated with younger patient age and longer patient survival, the lack of cancer predisposition in FOP (where identical mutations can be found), suggests that additional driver mutations are necessary.(45,47)

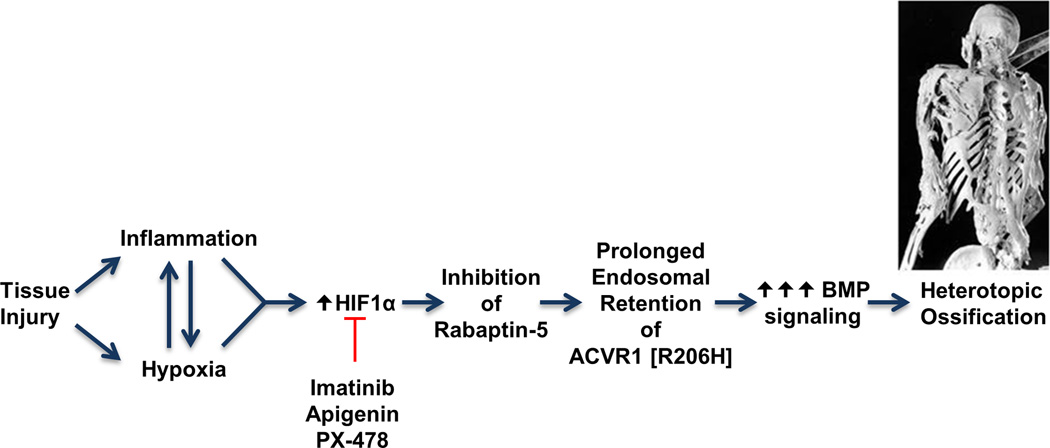

Our findings allow us to construct a working schema of the pathophysiology of flare-ups and resultant HEO in FOP (Fig. 6). Generation of a hypoxic microenvironment in injured skeletal muscle appears to be a critical step in the formation of HEO in FOP. Studies show that dysregulated BMP signaling creates an inflammatory and hypoxic microenvironment(48–55). Inflammation and hypoxia, acting through HIF-1α, down-regulate Rabaptin-5 (RABEP1) expression and cause retention of mACVR1 in signaling endosomes where it amplifies and prolongs BMP signaling with resultant HEO(9,56,57). Enhanced BMP signaling in FOP lesions is likely due to both increased endosomal retention of mACVR1 in hypoxic FOP lesional cells and to increased basal BMP signaling relative to the wild-type receptor(5,25). This mechanism is also supported by a report showing that receptor kinase activity affects FGFR3 trafficking and determines the spatial segregation of signaling pathways, suggesting that highly activated receptors increase signaling capacity from intracellular compartments.(58) Taken together, our data suggest that inflammation and tissue hypoxia create a microenvironment that amplifies and prolongs BMP signaling from mACVR1 and promotes ectopic chondrogenesis and HEO in FOP.

Figure. 6.

Hypothetical schema for hypoxia-associated changes in BMP signaling in FOP. Inhibition of Rabaptin-5 by HIF-1α results in prolonged endosomal retention of mACVR1 and enhanced BMP signaling.

Although our study focused on the hypoxic endosomal retention of mACVR1 in the pathogenesis of episodic HEO in FOP, one can speculate that the cellular response to hypoxia may be more generalizable to other BMP receptors as well as more common forms of HEO. In fact, the cellular response to hypoxia noted with mACVR1 was also seen with wild-type ACVR1, albeit to a much lesser extent as one might expect with endosomal retention of a well-regulated receptor.

It is a confounding observation that HEO in FOP is limited to skeletal muscle, fascia, tendon, and ligaments. Although highly speculative, the precise combination of inductive factors, connective tissue progenitor cells and microenvironmental factors may be lacking in other tissues. Further, there are even exceptions to the notion that all skeletal muscles behave similarly in FOP; for example, extra-ocular muscles, the tongue, and the diaphragm are all spared from HEO in FOP. However, under normal physiologic conditions, those muscles do not fatigue or become hypoxic, perhaps explaining their protection from HEO. This variation in skeletal muscles may, in part, be related to the embryonic derivation and gene expression profile of their resident stem cells,(59) and understanding these differences could provide insight into mechanisms underlying the susceptibility of certain muscles to HEO.

We have demonstrated that signaling in FOP lesion formation has a BMP ligand-independent component and is mediated by the SMAD 1/5/8 pathway under hypoxic conditions present in both an injury-induced animal model of FOP and in lesions from FOP patients. However, injury-induced inflammation is a complex physiologic response to damaged tissue, including infiltrating immune cells, progenitor cells, as well as secreted cytokines and chemoattractants. Thus, while hypoxia mediates BMP ligand-independent signaling, other responses in the local microenvironment could be ligand-dependent and result in a more complex regulation of ectopic chondrogenesis and HEO in FOP. The mutant, but not wildtype, ACVR1 receptor transduces signals from ligands of the activin family via BMP-, not activin/TGFβ-responsive Smad effectors.(60,61) Although activin ligands can assemble a ternary complex composed of a dual-specificity type II receptor and wildtype ACVR1, a signal is not propagated, hence actually act as antagonists of BMP signaling. In hypoxic cells of FOP lesions, mACVR1 might indeed be retained and aberrantly function in the endosomal pathway in a BMP ligand-independent manner, however as an activin-dependent heterotetrameric signalling complex. Such a mechanism could account for the disparate activities of wildtype and mACVR1 receptors during the hypoxia-dependent prolongation of endosomal signalling reported here. We hypothesize that in FOP, neither local secretion of activin family ligands nor hypoxia within soft tissues would be sufficient to produce HEO, however both would be necessary.

We previously described an Acvr1 chimeric knock-in model (Acvr1R206H/+) that recapitulated with great fidelity the phenotype seen in FOP patients, including injury-induced flare-ups; however, this model was very limited in that there was no germline transmission.(62) The caAcvr1Q207D/+ model used in our current work recapitulates the injury-induced flare-ups seen in patients with FOP and has been an accepted model to study both FOP lesion formation and the response to specific therapeutic interventions.(24,26) Although we did not use mechanically based methods for trauma-induced HEO (e.g., blunt injury), we did use a highly reproducible chemically-induced method of muscle injury (i.e., cardiotoxin injection). We postulate that our findings here also have important implications for traumatic HEO.

That connective tissue hypoxia is a potent stimulus for HEO in caAcvr1Q207D/+ mice is supported by a recent study in which siRNA knockdown of HIF-1α mRNA and-Runx2 mRNA resulted in inhibition of HEO in an Achilles tenotomy mouse model.(63) We explored the use of available compounds to block HIF-1α signaling and thus inhibit HEO in the FOP animal model. Apigenin, a naturally occurring HIF-1α inhibitor found in parsley(29) was used to modulate dysregulated BMP signaling in FOP connective tissue progenitor (SHED) cells and restore BMP signaling to levels found in control SHED cells. Furthermore, apigenin was effective in abrogating HEO in a mouse model of FOP. Imatinib, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that exhibits anti-angiogenic and anticancer properties, was also used because of its potent HIF-1α inhibition.(30) Although imatinib has off-target effects (such as those against PGDF) it was selected because, unlike other available inhibitors, it has low toxicity and the ability to inhibit HIF-1α without directly affecting ACVR1 in vivo.(64) Our study shows that imatinib, like apigenin, potently inhibits BMP pathway specific SMAD1/5/8 phosphorylation induced by HIF-1α in vitro, as well as HEO following tissue injury in a mouse model of FOP. Interestingly, Compound C (also known as Dorsomorphin) an AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) and BMP type I receptor inhibitor, blocks hypoxic activation of HIF-1α in vitro.(65)Although many agents inhibit HIF-1α in cells, only a few have been shown to effectively inhibit HIF-1α in vivo.(66,67) In all cases, it is possible that these compounds also affect HEO by mechanisms other than HIF-1α-SMAD crosstalk,(68) but more potent and highly specific HIF-1α inhibitors such as PX-478, which was also highly effective in our FOP mouse model, offer hope for the future.(31,32) Although we demonstrate that chemical inhibitors of HIF-1α can block SMAD 1/5/8 phosphorylation in vitro and HEO in vivo, direct genetic proof of HIF-1α involvement in HEO is lacking.

Although we have not explored the possibility of systemic skeletal effects of imatinib or apigenin in the caAcvr1Q207D/+ mouse model, an in vivo analysis in adult mice following eight weeks of imatinib treatment demonstrated a decrease in osteoclast activity, suggesting that imatinib may have therapeutic value as an anti-osteolytic agent.(69) In healthy humans, there appears to be no significant skeletal effects postnatally, and in patients with chronic mylelogenous leukemia long-term therapy actually promotes bone formation in the normotopic skeleton.(70) Similarly, apigenin appears to be protective against bone loss, especially in ovariectomized mice and rats.(71,72)

The evolutionary pressure for oxygen-sensitive regulation of BMP signaling probably arose long before organisms with endoskeletons appeared on Earth.(73–75) It is likely that multi-cellular creatures of the pre-Cambrian world developed and thrived in hypoxic sea beds where hypoxia-BMP pathway interactions were extant and selective for morphogenesis.(76,77) Importantly, invertebrate Drosophila larvae develop and live in a hypoxic microenvironment of rotting fruit in which the BMP/Decapentaplegic (DPP) signaling pathway functions to form and maintain the body plan and the exoskeleton.(78) In addition, when the FOP mutation in Saxophone, the Drosophila homologue of ACVR1, is introduced into Drosophila, severe patterning malformations arise and are amplified in a hypoxic microenvironment.(79) Interestingly, Drosophila ema mutants, which are defective in endosomal membrane trafficking, accumulate BMP receptors and phosphorylated Mad in their synapses.(12) This unexpected finding supports that dysregulated endosomal retention of BMP receptors causes hyperactive BMP signaling at the neuromuscular junction,(12) a finding with critical implications for common forms of HEO such as those that occur sporadically following neurologic and soft tissue injury. These observations strongly support our findings of the regulatory role of the endosomal pathway in hypoxic BMP signaling.

In summary, our investigation supports that cellular oxygen sensing is a critical regulator of HEO in FOP, knowledge that will contribute to the development of more effective treatments for FOP and possibly for related common disorders of heterotopic ossification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Celeste Simon for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. This work was supported in part by the International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association (IFOPA), the Center for Research in FOP and Related Disorders, the Ian Cali Endowment for FOP Research, the Whitney Weldon Endowment for FOP Research, the Isaac and Rose Nassau Professorship of Orthopaedic Molecular Medicine (to FSK), the Cali-Weldon Research Professorship in FOP (to EMS), the Rita Allen Foundation, the Roemex Fellowship for FOP Research (to HW), the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01-AR41916).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design of the work were predominately by RJP and FSK, with contributions by HW, CML, and ES. Collection and/or assembly of data were predominately by HW and CML, with important contributions by VL, J-HK, RM-W, and MX. The manuscript was written by RJP and FSK with revisions by ES, EMS and JG. Critical study materials were provided by ES and LM. Data analysis and interpretation were performed by all authors. The manuscript was approved by all authors.

References

- 1.Kaplan FS, Shen Q, Lounev V, Seemann P, Groppe J, Katagiri T, Pignolo RJ, Shore EM. Skeletal metamorphosis in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(6):521–530. doi: 10.1007/s00774-008-0879-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pignolo RJ, Foley KL. Nonhereditary heterotopic ossification: Implications for injury, arthropathy, and aging. Clinical Reviews in Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2005;3:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, Fenstermacher DA, Cho TJ, Choi IH, Connor JM, Delai P, Glaser DL, LeMerrer M, Morhart R, Rogers JG, Smith R, Triffitt JT, Urtizberea JA, Zasloff M, Brown MA, Kaplan FS. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet. 2006 May;38(5):525–527. doi: 10.1038/ng1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan FS, Xu M, Seemann P, Connor JM, Glaser DL, Carroll L, Delai P, Fastnacht-Urban E, Forman SJ, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Hoover-Fong J, Koster B, Pauli RM, Reardon W, Zaidi SA, Zasloff M, Morhart R, Mundlos S, Groppe J, Shore EM. Classic and atypical fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) phenotypes are caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor ACVR1. Hum Mutat. 2009 Mar;30(3):379–390. doi: 10.1002/humu.20868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaikuad A, Alfano I, Kerr G, Sanvitale CE, Boergermann JH, Triffitt JT, von Delft F, Knapp S, Knaus P, Bullock AN. Structure of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK2 and implications for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Biol Chem. 2012 Oct 26;287(44):36990–36998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoyama M, Sun-Wada GH, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto M, Hamada H, Wada Y. Spatial restriction of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in mouse gastrula through the mVam2-dependent endocytic pathway. Dev Cell. 2012 Jun 12;22(6):1163–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan FS, Pignolo RJ, Shore EM. The FOP metamorphogene encodes a novel type I receptor that dysregulates BMP signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009 Oct-Dec;20(5–6):399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011 Feb 17;364(7):656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Roche O, Yan MS, Finak G, Evans AJ, Metcalf JL, Hast BE, Hanna SC, Wondergem B, Furge KA, Irwin MS, Kim WY, Teh BT, Grinstein S, Park M, Marsden PA, Ohh M. Regulation of endocytosis via the oxygen-sensing pathway. Nat Med. 2009 Mar;15(3):319–324. doi: 10.1038/nm.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Pena LS, Billings PC, Fiori JL, Ahn J, Kaplan FS, Shore EM. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP), a disorder of ectopic osteogenesis, misregulates cell surface expression and trafficking of BMPRIA. J Bone Miner Res. 2005 Jul;20(7):1168–1176. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleason RJ, Akintobi AM, Grant BD, Padgett RW. BMP signaling requires retromer-dependent recycling of the type I receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Feb 18;111(7):2578–2583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319947111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S, Wairkar YP, Daniels RW, DiAntonio A. The novel endosomal membrane protein Ema interacts with the class C Vps-HOPS complex to promote endosomal maturation. J Cell Biol. 2010 Mar 8;188(5):717–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seto ES, Bellen HJ, Lloyd TE. When cell biology meets development: endocytic regulation of signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 2002 Jun 1;16(11):1314–1336. doi: 10.1101/gad.989602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marxsen JH, Stengel P, Doege K, Heikkinen P, Jokilehto T, Wagner T, Jelkmann W, Jaakkola P, Metzen E. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) promotes its degradation by induction of HIF-alpha-prolyl-4-hydroxylases. Biochem J. 2004 Aug 1;381(Pt 3):761–767. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008 Jun 5;453(7196):807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loboda A, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. HIF-1 and HIF-2 transcription factors--similar but not identical. Mol Cells. 2010 May;29(5):435–442. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araldi E, Schipani E. Hypoxia, HIFs and bone development. Bone. 2010 Aug;47(2):190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.04.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schipani E, Ryan HE, Didrickson S, Kobayashi T, Knight M, Johnson RS. Hypoxia in cartilage: HIF-1alpha is essential for chondrocyte growth arrest and survival. Genes Dev. 2001 Nov 1;15(21):2865–2876. doi: 10.1101/gad.934301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Wan C, Deng L, Liu X, Cao X, Gilbert SR, Bouxsein ML, Faugere MC, Guldberg RE, Gerstenfeld LC, Haase VH, Johnson RS, Schipani E, Clemens TL. The hypoxia-inducible factor alpha pathway couples angiogenesis to osteogenesis during skeletal development. J Clin Invest. 2007 Jun;117(6):1616–1626. doi: 10.1172/JCI31581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung MC, Mills GB, Yu D. Oxygen sensor boosts growth factor signaling. Nat Med. 2009 Mar;15(3):246–247. doi: 10.1038/nm0309-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas C, Strutt D. Rabaptin-5 and Rabex-5 are neoplastic tumour suppressor genes that interact to modulate Rab5 dynamics in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2014 Jan 1;385(1):107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pignolo RJ, Suda RK, Kaplan FS. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva lesion. Clinical Reviews in Bone and Mineral Metabolism. 2005;3:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukuda T, Scott G, Komatsu Y, Araya R, Kawano M, Ray MK, Yamada M, Mishina Y. Generation of a mouse with conditionally activated signaling through the BMP receptor, ALK2. Genesis. 2006 Apr;44(4):159–167. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu PB, Deng DY, Lai CS, Hong CC, Cuny GD, Bouxsein ML, Hong DW, McManus PM, Katagiri T, Sachidanandan C, Kamiya N, Fukuda T, Mishina Y, Peterson RT, Bloch KD. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic [corrected] ossification. Nat Med. 2008 Dec;14(12):1363–1369. doi: 10.1038/nm.1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Q, Little SC, Xu M, Haupt J, Ast C, Katagiri T, Mundlos S, Seemann P, Kaplan FS, Mullins MC, Shore EM. The fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva R206H ACVR1 mutation activates BMP-independent chondrogenesis and zebrafish embryo ventralization. J Clin Invest. 2009 Nov;119(11):3462–3472. doi: 10.1172/JCI37412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimono K, Tung WE, Macolino C, Chi AH, Didizian JH, Mundy C, Chandraratna RA, Mishina Y, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-gamma agonists. Nat Med. 2011 Apr;17(4):454–460. doi: 10.1038/nm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billings PC, Fiori JL, Bentwood JL, O'Connell MP, Jiao X, Nussbaum B, Caron RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Dysregulated BMP signaling and enhanced osteogenic differentiation of connective tissue progenitor cells from patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Mar;23(3):305–313. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.071030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen YG. Endocytic regulation of TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009 Jan;19(1):58–70. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang J, Zhou Q, Liu LZ, Xia C, Hu X, Shi X, Jiang BH. Apigenin inhibits tumor angiogenesis through decreasing HIF-1alpha and VEGF expression. Carcinogenesis. 2007 Apr;28(4):858–864. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litz J, Krystal GW. Imatinib inhibits c-Kit-induced hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha activity and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006 Jun;5(6):1415–1422. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee K, Kim HM. A novel approach to cancer therapy using PX-478 as a HIF-1alpha inhibitor. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Oct;34(10):1583–1585. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welsh S, Williams R, Kirkpatrick L, Paine-Murrieta G, Powis G. Antitumor activity and pharmacodynamic properties of PX-478, an inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004 Mar;3(3):233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maes C, Carmeliet G, Schipani E. Hypoxia-driven pathways in bone development, regeneration and disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012 Jun;8(6):358–366. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunwoodie SL. The role of hypoxia in development of the Mammalian embryo. Dev Cell. 2009 Dec;17(6):755–773. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factors, and disease pathophysiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:47–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohyeldin A, Garzon-Muvdi T, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Oxygen in stem cell biology: a critical component of the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2010 Aug 6;7(2):150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon MC, Keith B. The role of oxygen availability in embryonic development and stem cell function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Apr;9(4):285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathieu J, Zhou W, Xing Y, Sperber H, Ferreccio A, Agoston Z, Kuppusamy KT, Moon RT, Ruohola-Baker H. Hypoxia-inducible factors have distinct and stage-specific roles during reprogramming of human cells to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 May 1;14(5):592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida Y, Takahashi K, Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Hypoxia enhances the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009 Sep 4;5(3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medici D, Shore EM, Lounev VY, Kaplan FS, Kalluri R, Olsen BR. Conversion of vascular endothelial cells into multipotent stem-like cells. Nat Med. 2010 Dec;16(12):1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/nm.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romero-Lanman EE, Pavlovic S, Amlani B, Chin Y, Benezra R. Id1 maintains embryonic stem cell self-renewal by up-regulation of Nanog and repression of Brachyury expression. Stem Cells Dev. 2012 Feb 10;21(3):384–393. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ying QL, Nichols J, Chambers I, Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003 Oct 31;115(3):281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fontebasso AM, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Schwartzentruber J, Nikbakht H, Gerges N, Fiset PO, Bechet D, Faury D, De Jay N, Ramkissoon LA, Corcoran A, Jones DT, Sturm D, Johann P, Tomita T, Goldman S, Nagib M, Bendel A, Goumnerova L, Bowers DC, Leonard JR, Rubin JB, Alden T, Browd S, Geyer JR, Leary S, Jallo G, Cohen K, Gupta N, Prados MD, Carret AS, Ellezam B, Crevier L, Klekner A, Bognar L, Hauser P, Garami M, Myseros J, Dong Z, Siegel PM, Malkin H, Ligon AH, Albrecht S, Pfister SM, Ligon KL, Majewski J, Jabado N, Kieran MW. Recurrent somatic mutations in ACVR1 in pediatric midline high-grade astrocytoma. Nat Genet. 2014 May;46(5):462–466. doi: 10.1038/ng.2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor KR, Mackay A, Truffaux N, Butterfield YS, Morozova O, Philippe C, Castel D, Grasso CS, Vinci M, Carvalho D, Carcaboso AM, de Torres C, Cruz O, Mora J, Entz-Werle N, Ingram WJ, Monje M, Hargrave D, Bullock AN, Puget S, Yip S, Jones C, Grill J. Recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nat Genet. 2014 May;46(5):457–461. doi: 10.1038/ng.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL, Ju B, Li Y, Zhu X, Qu C, Chen X, Zhang J, Easton J, Edmonson M, Ma X, Lu C, Nagahawatte P, Hedlund E, Rusch M, Pounds S, Lin T, Onar-Thomas A, Huether R, Kriwacki R, Parker M, Gupta P, Becksfort J, Wei L, Mulder HL, Boggs K, Vadodaria B, Yergeau D, Russell JC, Ochoa K, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Jones C, Boop FA, Broniscer A, Wetmore C, Gajjar A, Ding L, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, Taylor MR, Downing JR, Ellison DW, Zhang J, Baker SJ St. Jude Children's Research Hospital-Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome P. The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet. 2014 May;46(5):444–450. doi: 10.1038/ng.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buczkowicz P, Hoeman C, Rakopoulos P, Pajovic S, Letourneau L, Dzamba M, Morrison A, Lewis P, Bouffet E, Bartels U, Zuccaro J, Agnihotri S, Ryall S, Barszczyk M, Chornenkyy Y, Bourgey M, Bourque G, Montpetit A, Cordero F, Castelo-Branco P, Mangerel J, Tabori U, Ho KC, Huang A, Taylor KR, Mackay A, Bendel AE, Nazarian J, Fangusaro JR, Karajannis MA, Zagzag D, Foreman NK, Donson A, Hegert JV, Smith A, Chan J, Lafay-Cousin L, Dunn S, Hukin J, Dunham C, Scheinemann K, Michaud J, Zelcer S, Ramsay D, Cain J, Brennan C, Souweidane MM, Jones C, Allis CD, Brudno M, Becher O, Hawkins C. Genomic analysis of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas identifies three molecular subgroups and recurrent activating ACVR1 mutations. Nat Genet. 2014 May;46(5):451–456. doi: 10.1038/ng.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zadeh G, Aldape K. ACVR1 mutations and the genomic landscape of pediatric diffuse glioma. Nat Genet. 2014 May;46(5):421–422. doi: 10.1038/ng.2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dizon ML, Maa T, Kessler JA. The bone morphogenetic protein antagonist noggin protects white matter after perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 Jun;42(3):318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Emans PJ, Spaapen F, Surtel DA, Reilly KM, Cremers A, van Rhijn LW, Bulstra SK, Voncken JW, Kuijer R. A novel in vivo model to study endochondral bone formation; HIF-1alpha activation and BMP expression. Bone. 2007 Feb;40(2):409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frank DB, Abtahi A, Yamaguchi DJ, Manning S, Shyr Y, Pozzi A, Baldwin HS, Johnson JE, de Caestecker MP. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 promotes pulmonary vascular remodeling in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2005 Sep 2;97(5):496–504. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181152.65534.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gelse K, Muhle C, Knaup K, Swoboda B, Wiesener M, Hennig F, Olk A, Schneider H. Chondrogenic differentiation of growth factor-stimulated precursor cells in cartilage repair tissue is associated with increased HIF-1alpha activity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Dec;16(12):1457–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maegdefrau U, Amann T, Winklmeier A, Braig S, Schubert T, Weiss TS, Schardt K, Warnecke C, Hellerbrand C, Bosserhoff AK. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 is induced in hepatocellular carcinoma by hypoxia and promotes tumour progression. J Pathol. 2009 Aug;218(4):520–529. doi: 10.1002/path.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mizuno Y, Tokuzawa Y, Ninomiya Y, Yagi K, Yatsuka-Kanesaki Y, Suda T, Fukuda T, Katagiri T, Kondoh Y, Amemiya T, Tashiro H, Okazaki Y. miR-210 promotes osteoblastic differentiation through inhibition of AcvR1b. FEBS Lett. 2009 Jul 7;583(13):2263–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tian F, Zhou AX, Smits AM, Larsson E, Goumans MJ, Heldin CH, Boren J, Akyurek LM. Endothelial cells are activated during hypoxia via endoglin/ALK-1/SMAD1/5 signaling in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010 Feb 12;392(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tseng WP, Yang SN, Lai CH, Tang CH. Hypoxia induces BMP-2 expression via ILK, Akt, mTOR, and HIF-1 pathways in osteoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2010 Jun;223(3):810–818. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeigerer A, Gilleron J, Bogorad RL, Marsico G, Nonaka H, Seifert S, Epstein-Barash H, Kuchimanchi S, Peng CG, Ruda VM, Del Conte-Zerial P, Hengstler JG, Kalaidzidis Y, Koteliansky V, Zerial M. Rab5 is necessary for the biogenesis of the endolysosomal system in vivo. Nature. 2012 May 24;485(7399):465–470. doi: 10.1038/nature11133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Culbert AL, Chakkalakal SA, Theosmy EG, Brennan TA, Kaplan FS, Shore EM. Alk2 regulates early chondrogenic fate in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva heterotopic endochondral ossification. Stem Cells. 2014 May;32(5):1289–1300. doi: 10.1002/stem.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lievens PM, Mutinelli C, Baynes D, Liboi E. The kinase activity of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 with activation loop mutations affects receptor trafficking and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004 Oct 8;279(41):43254–43260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Randolph ME, Pavlath GK. A muscle stem cell for every muscle: variability of satellite cell biology among different muscle groups. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:190. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hatsell SJ, Idone V, Wolken DM, Huang L, Kim HJ, Wang L, Wen X, Nannuru KC, Jimenez J, Xie L, Das N, Makhoul G, Chernomorsky R, D'Ambrosio D, Corpina RA, Schoenherr CJ, Feeley K, Yu PB, Yancopoulos GD, Murphy AJ, Economides AN. ACVR1R206H receptor mutation causes fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva by imparting responsiveness to activin A. Sci Transl Med. 2015 Sep 2;7(303):303ra137. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hino K, Ikeya M, Horigome K, Matsumoto Y, Ebise H, Nishio M, Sekiguchi K, Shibata M, Nagata S, Matsuda S, Toguchida J. Neofunction of ACVR1 in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Dec 15;112(50):15438–15443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510540112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chakkalakal SA, Zhang D, Culbert AL, Convente MR, Caron RJ, Wright AC, Maidment AD, Kaplan FS, Shore EM. An Acvr1 R206H knock-in mouse has fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Aug;27(8):1746–1756. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin L, Shen Q, Leng H, Duan X, Fu X, Yu C. Synergistic inhibition of endochondral bone formation by silencing Hif1alpha and Runx2 in trauma-induced heterotopic ossification. Mol Ther. 2011 Aug;19(8):1426–1432. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, Gallant P, Atteridge CE, Campbell BT, Chan KW, Ciceri P, Davis MI, Edeen PT, Faraoni R, Floyd M, Hunt JP, Lockhart DJ, Milanov ZV, Morrison MJ, Pallares G, Patel HK, Pritchard S, Wodicka LM, Zarrinkar PP. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Jan;26(1):127–132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emerling BM, Viollet B, Tormos KV, Chandel NS. Compound C inhibits hypoxic activation of HIF-1 independent of AMPK. FEBS Lett. 2007 Dec 11;581(29):5727–5731. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koh MY, Spivak-Kroizman TR, Powis G. Inhibiting the hypoxia response for cancer therapy: the new kid on the block. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Oct 1;15(19):5945–5946. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene. 2010 Feb 4;29(5):625–634. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Werner CM, Zimmermann SM, Wurgler-Hauri CC, Lane JM, Wanner GA, Simmen HP. Use of imatinib in the prevention of heterotopic ossification. HSS J. 2013 Jul;9(2):166–170. doi: 10.1007/s11420-013-9335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dewar AL, Farrugia AN, Condina MR, Bik To L, Hughes TP, Vernon-Roberts B, Zannettino AC. Imatinib as a potential antiresorptive therapy for bone disease. Blood. 2006 Jun 1;107(11):4334–4337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fitter S, Dewar AL, Kostakis P, To LB, Hughes TP, Roberts MM, Lynch K, Vernon-Roberts B, Zannettino AC. Long-term imatinib therapy promotes bone formation in CML patients. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2538–2547. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goto T, Hagiwara K, Shirai N, Yoshida K, Hagiwara H. Apigenin inhibits osteoblastogenesis and osteoclastogenesis and prevents bone loss in ovariectomized mice. Cytotechnology. 2015 Mar;67(2):357–365. doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9694-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park JA, Ha SK, Kang TH, Oh MS, Cho MH, Lee SY, Park JH, Kim SY. Protective effect of apigenin on ovariectomy-induced bone loss in rats. Life Sci. 2008 Jun 20;82(25–26):1217–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wan C, Gilbert SR, Wang Y, Cao X, Shen X, Ramaswamy G, Jacobsen KA, Alaql ZS, Eberhardt AW, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA, Deng L, Clemens TL. Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Jan 15;105(2):686–691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708474105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolar P, Gaber T, Perka C, Duda GN, Buttgereit F. Human early fracture hematoma is characterized by inflammation and hypoxia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 Nov;469(11):3118–3126. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1865-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Taylor CT, McElwain JC. Ancient atmospheres and the evolution of oxygen sensing via the hypoxia-inducible factor in metazoans. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010 Oct;25(5):272–279. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gill BC, Lyons TW, Young SA, Kump LR, Knoll AH, Saltzman MR. Geochemical evidence for widespread euxinia in the later Cambrian ocean. Nature. 2011 Jan 6;469(7328):80–83. doi: 10.1038/nature09700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lowe CJ, Terasaki M, Wu M, Freeman RM, Jr, Runft L, Kwan K, Haigo S, Aronowicz J, Lander E, Gruber C, Smith M, Kirschner M, Gerhart J. Dorsoventral patterning in hemichordates: insights into early chordate evolution. PLoS Biol. 2006 Sep;4(9):e291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Romero NM, Dekanty A, Wappner P. Cellular and developmental adaptations to hypoxia: a Drosophila perspective. Methods Enzymol. 2007;435:123–144. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)35007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le VQ, Wharton KA. Hyperactive BMP signaling induced by ALK2(R206H) requires type II receptor function in a Drosophila model for classic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Dev Dyn. 2012 Jan;241(1):200–214. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.