Abstract

In π-conjugated chain molecules such as carotenoids, coupling between electronic and vibrational degrees of freedom is of central importance. It governs both dynamic and static properties, such as the time scales of excited state relaxation as well as absorption spectra. In this work, we treat vibronic dynamics in carotenoids on four electronic states (|S0⟩, |S1⟩, |S2⟩, and |Sn⟩) in a physically rigorous framework. This model explains all features previously associated with the intensely debated S* state. Besides successfully fitting transient absorption data of a zeaxanthin homologue, this model also accounts for previous results from global target analysis and chain length-dependent studies. Additionally, we are able to incorporate findings from pump-deplete-probe experiments, which were incompatible to any pre-existing model. Thus, we present the first comprehensive and unified interpretation of S*-related features, explaining them by vibronic transitions on either S1, S0, or both, depending on the chain length of the investigated carotenoid.

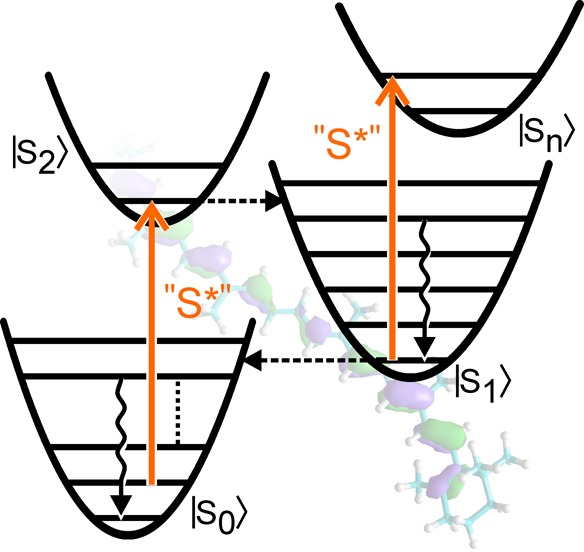

Vibrational energy relaxation is a process of equilibration among excited vibrational states.1 Such processes are of fundamental importance to molecular dynamics: after photoexcitation, vibrational energy relaxation dissipates excess vibrational energy, a process indicated by wavy arrows in Figure 1. Internal conversion between donor and acceptor electronic states can also populate high-lying vibrational acceptor states that will relax to their respective equilibrium configuration. Both processes, photoexcitation between electronic ground- and displaced excited- states and internal conversion between states with large zero-energy differences, are found in carotenoids.2

Figure 1.

Energy level scheme describing electronic (dashed horizontal lines) and vibrational (wavy vertical lines) energy relaxation in carotenoids along a reaction coordinate q. Colored vertical arrows indicate allowed electronic transitions. Electronic states are labeled in ket-notation, while vibrational levels on electronic ground and excited state are denoted by primes and double-primes, respectively. The gray curve depicting the Sm state is shown for completeness and not included in the calculations.

Chlorophylls and carotenoids are the two molecular building blocks of photosynthetic light harvesters. Carotenoids harvest the blue-green spectral components of solar radiation, and also quench long-lived states of chlorophylls to avoid the formation of singlet oxygen, a potentially harmful species. These multiple roles are linked to the unusual dynamic and spectroscopic properties of carotenoids that are the subject of an ongoing scientific debate.3 Their polyenic backbone holds a delocalized π-electron system, which explains the intense lowest lying absorption band, typically in the 400–500 nm range. Remarkably, this transition is between ground and second electronic excited singlet state, S0 → S2, while the S0 → S1 transition is optically forbidden due to symmetry reasons, at least in an idealized C2h symmetry.4,5 Besides these unusual spectroscopic properties, the population dynamics of carotenoids are also noteworthy: in contrast to other systems with conjugated π-electrons, electronic excited states in carotenoids deactivate back to ground state rapidly, with an S2 to S1 transfer time of sub-200 fs and S1 to S0 transfer ranging from hundreds of femtoseconds to tens of picoseconds, all depending on chain length.

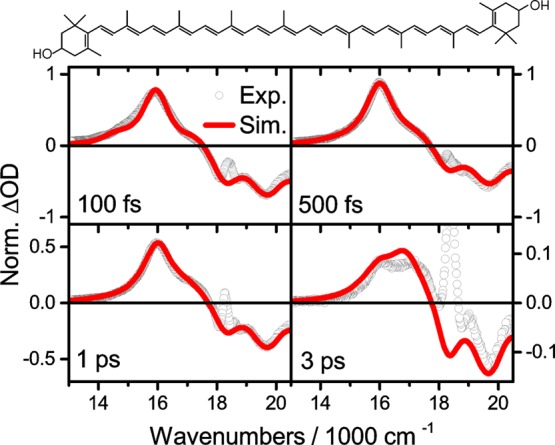

The electronic states depicted in Figure 1 explain most but not all features of spectrally resolved pump–probe measurements. Andersson and Gillbro6 were the first to describe a blue-detuned long-lived shoulder on the excited state absorption (ESA) of S1, which cannot be understood by just three electronic levels (S0, S1, S2). Depending on chain length, the lifetime of this feature, usually denoted as the S* signal, may exceed that of S1 substantially and hence cannot stem from the same electronic state. In this work, we investigate a long-chain homologue of zeaxanthin, called Zea15, with 15 conjugated double bonds (N = 15; see Figure 2). The short S2 lifetime of Zea15 of sub-100 fs explains why the S*-related shoulder near 17.000 cm–1 is already observed at a population time of 100 fs, as shown in Figure 2. The dominant feature at 100 fs is the S1 → Sn ESA, peaking at 16.000 cm–1. In agreement with the reported7 lifetimes of S1 and S* of 0.9 and 2.9 ps, respectively, the relative amplitude of the S* signal grows with population time to outweigh the S1 signal at 3 ps.

Figure 2.

Slices through the spectrally resolved pump–probe spectrum of zeaxanthin 15 (Zea15; see top) at indicated population times. Experimental data are taken from ref (7) and normalized to the highest value at 500 fs (40 mOD). The spike in experimental data (circles) near 18.000 cm–1 is due to scattered pump light. The red line shows simulation results as discussed in the text.

We note that the time-resolved data for Zea15 with its typical S* signature have been published previously. In the work by Staleva et al.,7 zeaxanthin and three homologues were studied to obtain the chain-length dependence of spectroscopic and dynamic properties of otherwise identical carotenoids. However, the authors were unable to assign the S* signature to either the excited state or the hot ground state unequivocally. The main focus of this work is the formulation of a unified model for S*, which incorporates all major reported findings related to this elusive state.

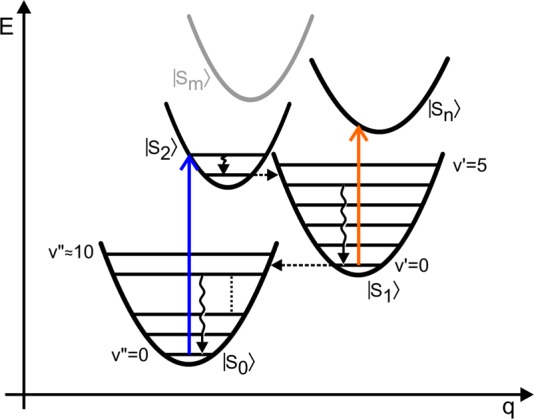

At present, there are several competing explanations for S*. In 2001, Gradinaru et al.8 considered S* as an additional electronic state similar to but different from S1. It was proposed that S* is an energy donor for bacteriochlorophylls in light harvesting complexes9 and also serves as a triplet-precursor state,8 which is a conclusion that has been challenged recently.10 Frank and co-workers11 also interpreted S* as an electronic excited state, but rather as the product of photoisomerization on S1. This was later drawn into question, based on experiments showing different temperature dependence of S* and S1, which is unexpected for photoinitiated excited state isomerization.12 The finding that S* can be “frozen out” is central to the so-called inhomogeneous ground state model,13 in which S1 and S* are both first electronic excited singlet states, but of different molecular species, represented by isomers with altered end group rotation.14−17 An alternative interpretation of pump–probe18−21 and pump-degenerate four wave mixing data22,23 explains S*-related features by a vibrationally hot ground state, hot S0. Within this hypothesis, it is important to differentiate two distinct mechanisms of addressing hot S0. Based on pump-deplete-probe experiments, Motzkus and co-workers suggested that hot S0 is populated by the pump-pulse via impulsive stimulated Raman scattering.20,24 A bandwidth-dependent study by Jailaubekov and others ruled out this mechanism by showing that the S* signatures occur regardless of the employed excitation bandwidth.25 Lenzer and co-workers26−28 argued that S* is populated in a sequential scheme such as S2 → hot S1 → S1 → hot S0 → S0, which is the essence of the model depicted in Figure 1. Such a deactivation scheme is, however, in contrast to earlier studies using global target analysis (GTA),13,29,30 in which the initially excited population on S2 splits to form both S1 and S*. The latter then shows a rise time of a few hundred femtoseconds, which seems irreconcilable with a sequential scheme proposed by Lenzer and co-workers.26 In a vibrational energy relaxation approach (VERA), we showed earlier that a rigorous treatment of vibrational relaxation and vibronic transitions on S1 leads to S*-like spectral signatures.31 This approach was successfully applied to β-carotene, where lifetimes of S* and S1 are similar, but fails if the lifetimes of these two states are significantly different, as found for longer chain carotenoids. In this work, we extend our previous model to treat vibrational relaxation explicitly on both S1 and S0. We show how this extension of VERA enables one to explain the S* signal in Zea15 as the results of vibronic transitions from vibrationally excited levels in the electronic ground state. Additionally, we demonstrate how, within this framework, experimental results from pump-deplete-probe, GTA, as well as chain-length dependent studies are easily incorporated.

The basics of VERA were described in detail previously.31 Briefly, we consider four electronic states |S0⟩, |S1⟩, |S2⟩ and |Sn⟩ with two high-frequency harmonic vibrational modes at 1522 and 1156 cm–1 coupled to the electronic transitions depicted in Figure 1. While the frequency value taken for the C=C mode, 1522 cm–1, is a good estimate for standard zeaxanthin,32 it is known that for carotenoids with number of double bonds N = 15 this frequency can be approximately 17 cm–1 blue-shifted.33 However, we note that the results presented below are not critically dependent on the choice of C=C stretch frequency value. Transient absorption (TA) spectra are simulated in a simplified third-order response function approach.34,35 Within this method, each optical transition involving vibrational levels on different electronic states is assigned a Lorentzian line-shape, multiplied by the respective Franck–Condon factors. Ground state bleaching (GSB), stimulated emission (SE), and ESA spectral components are then calculated as products of line-shapes and transition dipole moments between vibronic states, weighted by time-dependent population factors. As an example, the evolution of ESA from S1 is described by the transitions between all the vibrational levels on S1 and all the levels on Sn weighted by the populations of S1 levels at any given pump–probe delay time.36−38 As we compare modeling to experimental data obtained with a time-resolution of around 100 fs, faster processes such as ESA from S2 are not considered. Internal conversion between electronic states as well as vibrational relaxation within a given electronic manifold are described by a density matrix and originate from phonon-induced off-diagonal fluctuations in the system’s Hamiltonian, which is given in the Supporting Information (SI). These fluctuations are described by the bath spectral densities employing the overdamped Brownian oscillator model, which is parametrized by the reorganization energy and the relaxation time-scale.39 Both static (curve displacements, line-widths and transition energies) and dynamical parameters (reorganization energies in particular) are obtained by fitting TA and absorption data and are summarized in SI.

The fitting procedure leads to the red lines in Figure 2, in near-quantitative agreement with experimental results, shown as open circles (taken from the measurement by Staleva et al.7) We emphasize that VERA including vibrational relaxation on both S1 and S0 readily yields the S*-related shoulder near 17.000 cm–1, despite the fact that no extra state besides S1 is part of our model shown in Figure 1. It is noteworthy that various vibrational spectroscopic techniques report a 1750 cm–1 C=C stretching mode on S1, a fingerprint of the S1 state,15,40,41 yet we do not find its inclusion critical to the model. The near-perfect agreement between experiment and theory as shown in Figure 2 is encouraging, yet a direct link between S* and vibrationally hot ground state can be drawn by a simple, straightforward comparison. Figure 3 shows an experimental TA signal at 5 ps along with absorption spectra of vibrationally excited species.

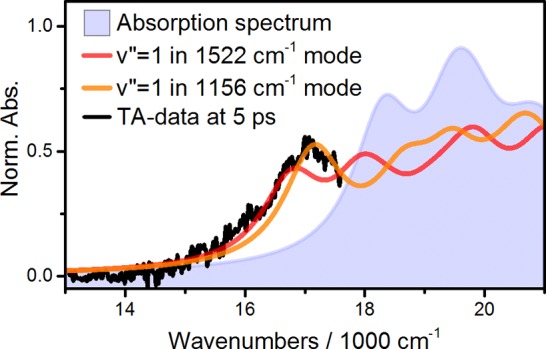

Figure 3.

Comparison between experimental TA data at 5 ps (black line) to a vibrationally relaxed absorption spectrum (light blue) and absorption spectra of vibrationally excited species (red and orange). The latter coincide with the S*-related features in the TA data.

The light blue filled curve in Figure 3 is the absorption spectrum at thermal equilibrium. The TA signal shown in black was taken at a population time of 5 ps, at which the S1 state has already fully decayed, given its lifetime of 0.9 ps, making S* the only remaining species with a lifetime of 2.9 ps. The TA data was cut at 17.600 cm–1 to exclude GSB signals. The experimental data coincide almost perfectly with the absorption spectra of vibrationally excited species, shown as red and orange lines in Figure 3. The two curves are thus ESA spectra from the indicated vibrationally excited states. Linking S* to vibronic transitions from vibrationally excited ground states explains the absence of S* → S2 absorption in the NIR,42 while S1 → S2 is an experimentally verified transition in the 900–1800 nm spectral region.43 By interpreting S1 as an electronic excited state and connecting S* to vibrationally hot ground states, we can also readily explain inconsistencies in chain-length dependent lifetimes: S1 lifetimes scale quasi-linearly with 1/(N-1), while the S* lifetime was only weakly dependent on N, as shown by Staleva et al.7 Within VERA, the S* lifetime is defined by vibrational relaxation on S0, which depends on the strength of system-bath interaction rather than on N.

While these explanations are encouraging, the link between S* and vibrationally excited levels in the electronic ground state disagrees with results from several GTA studies.13,30,44 In one set of reports, the purely sequential deactivation scheme (see Figure SI 1a) is challenged, and S* is interpreted as a branching channel from S1, competing with relaxation S1 → S0 (see Figure SI 1b).11,45 Alternatively, S* is being populated directly by S2, i.e., in parallel to S1 (see Figure SI 1c).30 We tested all three schemes on experimental and on modeled data and found that all of them (sequential, branching on S1, branching on S2) work equally well on experimental data as shown in the SI, Figure 1a–c. For GTA of simulated data, we find that both the sequential and the branching on S1 model give satisfactory results. The latter is surprising, as no such branching channel is part of our theoretical model (see Figure 1). This leads to the conclusion that for the case of Zea15, success of a certain target model in describing experimental data alone is not strong enough evidence to rule out other schemes. We emphasize that in our model there is no separate S* state; all S* signals are attributable to vibronic transitions from long-lived intermediate states. Namely, for longer or shorter carotenoids, the dominant factor behind S* are vibronic transitions from hot S0 or S1, as shown previously.31

Finally, we turn to the discussion of pump-deplete-probe (PDP) experiments in the context of VERA. In a set of experiments by the group around Motzkus,20,24 the authors depleted the initially excited S2 by an NIR-pulse. The depletion pulse lowered the ESA signal associated with cooled S1 but left the S* signatures largely unaltered. The depletion pulse is driving population out of S2, facilitated by an ESA transition in the NIR (see Figure 1).46−48 The fact that removal of population from S2 only affects S1 but not S* lead to the interpretation that S1 must be an electronic excited state, populated via S2, while S* must be populated instantaneously, i.e., by pump pulse-induced Raman-scattering49 or by two-photon interaction.21 For both interpretations, the pump pulse has to be spectrally broad in order to populate vibrationally high-lying states on S0. Jailaubekov et al.25 tested this aspect of the hot ground state hypothesis and found that S* gets populated, regardless of the spectral width of the pump pulse. This finally rules out the interpretation of S* as an instantaneously populated vibrationally hot ground state, but does not explain the experimental PDP results by Buckup et al.20 Within VERA, the depletion pulse will not only drive the transition from S2 to the higher lying electronic state, but will also stimulate population back down to vibrationally excited levels in S0, preferentially to v″ = 7 for Zea15. The effect of depletion into v″ = 7 is shown in Figure 4.

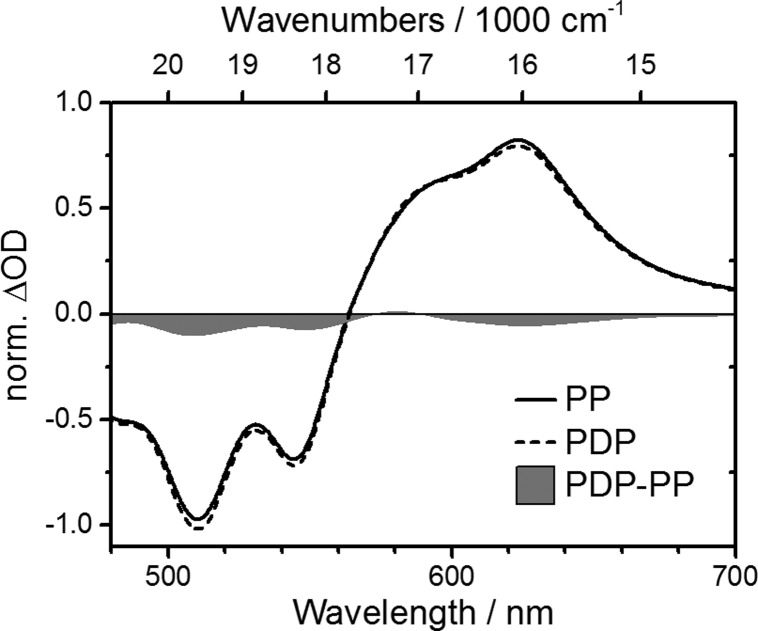

Figure 4.

Effect of depletion at 1000 nm after excitation into S2 for Zea15 model data. The black curves show calculated pump–probe (full line, PP) and pump-deplete-probe (PDP, dashed) at 2 ps pump–probe delay. The depletion pulse was set to arrive simultaneously with the pump-pulse. The filled gray line depicts the difference between the full and the dashed curve. ESA from S2 to higher lying electronic states is not considered.

The solid line in Figure 4 shows a spectral cut through the simulated pump–probe signal for Zea15. Parameters and model were the same as for the data shown in Figure 2. Relative intensity and central wavelength of the depletion pulse were chosen to coincide with the parameters given for the experiments by Buckup et al.20 A spectrally resolved PDP signal is shown as a dashed line in Figure 4. As can be seen, the depletion effects are stronger at the peak of the S1 signal than at the S* shoulder. This means that our employed model reproduces the PDP experiments by Buckup et al.,20 without the need to invoke multiphoton effects. Instead, we find that the NIR pulse populates a vibrationally hot ground state directly, which is the physical basis of S* in our model. This population is missing in S1, leading to the negative signal in the filled gray curve in Figure 4. This means that by including NIR transitions to the vibrationally hot ground state, VERA fully explains PDP experimental results. We note that the missing ESA from S2 → Sm (see Figure 1) does not affect this interpretation, as depletion to this state is seen as an overall loss channel, which would not affect the ratio between S* and S1 signals and hence leave the shape of the curves in Figure 4 unaltered.51

In summary, we have shown that an in-depth treatment of vibrational energy relaxation allows for a unified description of the ultrafast dynamics in carotenoids. Features previously associated with the intensely debated S* state are now explained by vibronic transitions from either S1 (as shown for β-carotene31) or from vibrationally excited levels on S0 (see Zea15 discussed above). This model readily incorporates results from pump-dump-probe experiments, which were irreconcilable with any previous model for carotenoid energy level schemes. High-level ab initio methods as presently available only for shorter polyenes50 would serve as a crucial test for the mechanisms proposed in this work.

Acknowledgments

D.A. and V.B. acknowledge the support from the Research Council of Lithuania(MIP-090/2015 and MIP-090/2016). T.P. thanks the Czech Science Foundation (Grant No. 16-10417S) for financial support. A. G. P. and J. H. acknowledge funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): START project Y631–N27.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01455.

Results of global (target) analysis, model Hamiltonian, and table of model parameters (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ V.B. has recently moved to the School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, U.K.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Uzer T.; Miller W. H. Theories of Intramolecular Vibrational-Energy Transfer. Phys. Rep. 1991, 199, 73–146. 10.1016/0370-1573(91)90140-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polivka T.; Sundstrom V. Ultrafast dynamics of carotenoid excited states - From solution to natural and artificial systems. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2021–2071. 10.1021/cr020674n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivka T.; Sundstrom V. Dark Excited States of Carotenoids: Consensus and Controversy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 477, 1–11. 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedor L.; Heriyanto; Fiedor J.; Pilch M. Effects of Molecular Symmetry on the Electronic Transitions in Carotenoids. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1821–1829. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavan P.; Schulten K. Electronic Excitations in Finite and Infinite Polyenes. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1987, 36, 4337–4357. 10.1103/PhysRevB.36.4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson P. O.; Gillbro T. Photophysics and Dynamcis of the Lowest Excited Singlet-State in Long Substituted Polyenes With Implications to the Very Long-Chain Limit. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 2509–2519. 10.1063/1.469672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staleva H.; Zeeshan M.; Chábera P.; Partali V.; Sliwka H.-R.; Polívka T. Ultrafast Dynamics of Long Homologues of Carotenoid Zeaxanthin. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 11304–11312. 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b08460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru C. C.; Kennis J. T. M.; Papagiannakis E.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; Cogdell R. J.; Fleming G. R.; Niederman R. A.; van Grondelle R. An Unusual Pathway of Excitation Energy Deactivation in Carotenoids: Singlet-to-Triplet Conversion on an Ultrafast Timescale in a Photosynthetic Antenna. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 2364–2369. 10.1073/pnas.051501298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakis E.; Kennis J. T. M.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; Cogdell R. J.; van Grondelle R. An alternative carotenoid-to-bacteriochlorophyll energy transfer pathway in photosynthetic light harvesting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 6017–6022. 10.1073/pnas.092626599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosumi D.; Maruta S.; Horibe T.; Nagaoka Y.; Fujii R.; Sugisaki M.; Cogdell R. J.; Hashimoto H. Ultrafast Excited State Dynamics of Spirilloxanthin in Solution and Bound to Core Antenna Complexes: Identification of the S* and T-1 States. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 064505. 10.1063/1.4737129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedzki D.; Koscielecki J. F.; Cong H.; Sullivan J. O.; Gibson G. N.; Birge R. R.; Frank H. A. Ultrafast Dynamics and Excited State Spectra of Open-Chain Carotenoids at Room and Low Temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 5984–5998. 10.1021/jp070500f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer J.; Maiuri M.; Viola D.; Lukes V.; Henry S.; Carey A. M.; Cogdell R. J.; Cerullo G.; Polli D. Explaining the Temperature Dependence of Spirilloxanthin’s S* Signal by an Inhomogeneous Ground State Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 6303–6310. 10.1021/jp4011372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakis E.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; Vengris M.; Cogdell R. J.; van Grondelle R.; Larsen D. S. Excited-State Dynamics of Carotenoids in Light-Harvesting Complexes. 1. Exploring the Relationship between the S-1 and S* States. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5727–5736. 10.1021/jp054633h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukes V.; Christensson N.; Milota F.; Kauffmann H. F.; Hauer J. Electronic Ground State Conformers of Beta-Carotene and Their Role in Ultrafast Spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2011, 506, 122–127. 10.1016/j.cplett.2011.02.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kloz M.; Weißenborn J.; Polivka T.; Frank H. A.; Kennis J. T. M. Spectral Watermarking in Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy: Resolving the Nature of the Carotenoid S* State. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 14619–14628. 10.1039/C6CP01464J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick M.; Kasper M.-A.; Richter C.; Mahrwald R.; Dobryakov A. L.; Kovalenko S. A.; Ernsting N. P. β-Carotene Revisited by Transient Absorption and Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16, 3824–3835. 10.1002/cphc.201500586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen R. L.; Enriquez M. M.; Wagner N. L.; Peacock-Villada A. Y.; Scriban C.; Schrock R. R.; Polivka T.; Frank H. A.; Birge R. R. Energetics and Dynamics of the Low-Lying Electronic States of Constrained Polyenes: Implications for Infinite Polyenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 1449–1465. 10.1021/jp310592s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek J. L.; Wohlleben W.; Cogdell R. J.; Zeidler D.; Motzkus M. Quantum Control of Energy Flow in Light Harvesting. Nature 2002, 417, 533–535. 10.1038/417533a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlleben W.; Buckup T.; Hashimoto H.; Cogdell R. J.; Herek J. L.; Motzkus M. Pump-Deplete-Probe Spectroscopy and the Puzzle of Carotenoid Dark States. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 3320–3325. 10.1021/jp036145k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckup T.; Savolainen J.; Wohlleben W.; Herek J. L.; Hashimoto H.; Correia R. R. B.; Motzkus M. Pump-Probe and Pump-Deplete-Probe Spectroscopies on Carotenoids With N = 9–15 Conjugated Bonds. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 194505. 10.1063/1.2388274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen J.; Buckup T.; Hauer J.; Jafarpour A.; Serrat C.; Motzkus M.; Herek J. L. Carotenoid Deactivation in an Artificial Light-Harvesting Complex Via a Vibrationally Hot Ground State. Chem. Phys. 2009, 357, 181–187. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2009.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer J.; Buckup T.; Motzkus M. Quantum Control Spectroscopy of Vibrational Modes: Comparison of Control Scenarios for Ground and Excited States in Beta-Carotene. Chem. Phys. 2008, 350, 220–229. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2008.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauer J.; Buckup T.; Motzkus M. Pump-Degenerate Four Wave Mixing as a Technique for Analyzing Structural and Electronic Evolution: Multidimensional Time-Resolved Dynamics Near a Conical Intersection. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 10517–10529. 10.1021/jp073727j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlleben W.; Buckup T.; Hashimoto H.; Cogdell R. J.; Herek J. L.; Motzkus M. Pump–Deplete–Probe Spectroscopy and the Puzzle of Carotenoid Dark States. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 3320–3325. 10.1021/jp036145k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jailaubekov A. E.; Song S. H.; Vengris M.; Cogdell R. J.; Larsen D. S. Using Narrowband Excitation to Confirm that the S* State in Carotenoids is Not a Vibrationally-Excited Ground State Species. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 487, 101–107. 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers F.; Scholz M.; Schimpfhauser J.; Bienert J.; Oum K.; Lenzer T. Collisional Relaxation of Apocarotenals: Identifying the S* State With Vibrationally Excited Molecules in the Ground Electronic State S-0*. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 10478–10488. 10.1039/C4CP05600K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golibrzuch K.; Ehlers F.; Scholz M.; Oswald R.; Lenzer T.; Oum K.; Kim H.; Koo S. Ultrafast Excited State Dynamics and Spectroscopy of 13,13 ’-Diphenyl-Beta-Carotene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 6340–6351. 10.1039/c0cp02525a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzer T.; Ehlers F.; Scholz M.; Oswald R.; Oum K. Assignment of Carotene S* state Features to the Vibrationally Hot Ground Electronic State. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 8832–8839. 10.1039/b925071a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stokkum I. H. M.; Larsen D. S.; van Grondelle R. Global and Target Analysis of Time-Resolved Spectra. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2004, 1657, 82–104. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jailaubekov A. E.; Vengris M.; Song S. H.; Kusumoto T.; Hashimoto H.; Larsen D. S. Deconstructing the Excited-State Dynamics of Beta-Carotene in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3905–3916. 10.1021/jp1082906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balevicius V.; Pour A. G.; Savolainen J.; Lincoln C. N.; Lukes V.; Riedle E.; Valkunas L.; Abramavicius D.; Hauer J. Vibronic Energy Relaxation Approach Highlighting Deactivation Pathways in Carotenoids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 19491–19499. 10.1039/C5CP00856E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn R.; Vanholten R. W. Zeaxanthin ([3r,3′r]-Beta-Beta-Carotene-3–3′diol) as a Resonance Raman and Visible Absorption Probe of Membrane-Structure. Biophys. J. 1979, 27, 221–235. 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85213-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes-Pinto M. M.; Sansiaume E.; Hashimoto H.; Pascal A. A.; Gall A.; Robert B. Electronic Absorption and Ground State Structure of Carotenoid Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 11015–11021. 10.1021/jp309908r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkunas L.; Abramavicius D.; Mancal T.. Molecular Excitation Dynamics and Relaxation: Quantum Theory and Spectroscopy; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- May V.; Kuehn O.. Charge and Energy Transfer Dynamics in Molecular Systems, 3rd ed.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kardas T. M.; Ratajska-Gadomska B.; Lapini A.; Ragnoni E.; Righini R.; Di Donato M.; Foggi P.; Gadomski W. Dynamics of the Time-Resolved Stimulated Raman Scattering Spectrum in Presence of Transient Vibronic Inversion of Population on the Example of Optically Excited Trans-Beta-Apo-8 ′-Carotenal. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 204312. 10.1063/1.4879060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. P.; Chen C. H.; Koyama Y.; Nagae H. Vibrational Relaxation and Redistribution in the 2A(g)(−) State of All-Trans-Lycopene as Revealed by Picosecond Time-Resolved Absorption Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 1632–1640. 10.1021/jp9728058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroumov E. E.; Muller M. G.; Reus M.; Holzwarth A. R. On the Nature of the ″Dark S*″ Excited State of beta-Carotene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 3698–3712. 10.1021/jp105385c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel S.Principles of Nonlinear Optical Spectroscopy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McCamant D. W.; Kukura P.; Mathies R. A. Femtosecond Time-Resolved Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy: Application to the Ultrafast Internal Conversion in Beta-Ccarotene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 8208–8214. 10.1021/jp030147n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraack J. P.; Wand A.; Buckup T.; Motzkus M.; Ruhman S. Mapping Multidimensional Excited State Dynamics Using Pump-Impulsive-Vibrational-Spectroscopy and Pump-Degenerate-Four-Wave-Mixing. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 14487–14501. 10.1039/c3cp50871d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakis E.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; van Grondelle R.; Niederman R. A.; Zigmantas D.; Sundstrom V.; Polivka T. A Near-Infrared Transient Absorption Study of the Excited-State Dynamics of the Carotenoid Spirilloxanthin in Solution and in the LH1 Complex of Rhodospirillum Rubrum. J. Phys. Chem. B 2003, 107, 11216–11223. 10.1021/jp034931j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polivka T.; Herek J. L.; Zigmantas D.; Akerlund H. E.; Sundstrom V. Direct observation of the (forbidden) S1 state in carotenoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 4914–4917. 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri M.; Snellenburg J. J.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; Pillai S.; Carter K. W.; Gust D.; Moore T. A.; Moore A. L.; van Grondelle R.; Cerullo G.; Polli D. Ultrafast Energy Transfer and Excited State Coupling in an Artificial Photosynthetic Antenna. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117, 14183–14190. 10.1021/jp401073w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedzwiedzki D. M.; Sullivan J. O.; Polivka T.; Birge R. R.; Frank H. A. Femtosecond Time-Resolved Transient Absorption Spectroscopy of Xanthophylls. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 22872–22885. 10.1021/jp0622738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. P.; Skibsted L. H.; Fujii R.; Koyama Y. Transient Absorption from the 1B(u)(+) State of All-Trans-Beta-Carotene Newly Identified in the Near-Infrared Region. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 73, 219–222. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosumi D.; Komukai M.; Hashimoto H.; Yoshizawa M. Ultrafast Dynamics of All-Trans-Beta-Carotene Explored by Resonant and Nonresonant Photoexcitations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 213601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.213601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson N.; Milota F.; Nemeth A.; Pugliesi I.; Riedle E.; Sperling J.; Pullerits T.; Kauffmann H. F.; Hauer J. Electronic Double-Quantum Coherences and Their Impact on Ultrafast Spectroscopy: The Example of Beta-Carotene. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 3366–3370. 10.1021/jz101409r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensson N.; Milota F.; Nemeth A.; Sperling J.; Kauffmann H. F.; Pullerits T.; Hauer J. Two-Dimensional Electronic Spectroscopy of Beta-Carotene. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 16409–16419. 10.1021/jp906604j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channels such as Sm to S* are speculative (see refs (13) and (21)) and of only marginal potential contribution and are therefore neglected in our model.

- Garavelli M.; Celani P.; Bernardi F.; Robb M. A.; Olivucci M. Force Fields for ’’Ultrafast’’ Photochemistry: The S-2 (1B(u))- > S-1(2A(g))- > S-0 (1A(g)) Reaction Path for All-Trans-Hexa-1,3,5-Triene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11487–11494. 10.1021/ja971280u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.