Abstract

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an abundant methylated sulfur compound in deep sea ecosystems. However, the mechanism underlying DMSO-induced reduction in benthic microorganisms is unknown. Shewanella piezotolerans WP3, which was isolated from a west Pacific deep sea sediment, can utilize DMSO as the terminal electron acceptor. In this study, two putative dms gene clusters [type I (dmsEFA1B1G1H1) and type II (dmsA2B2G2H2)] were identified in the WP3 genome. Genetic and physiological analyses demonstrated that both dms gene clusters were functional and the transcription of both gene clusters was affected by changes in pressure and temperature. Notably, the type I system is essential for WP3 to thrive under in situ conditions (4°C/20 MPa), whereas the type II system is more important under high pressure or low temperature conditions (20°C/20 MPa, 4°C/0.1 MPa). Additionally, DMSO-dependent growth conferred by the presence of both dms gene clusters was higher than growth conferred by either of the dms gene clusters alone. These data collectively suggest that the possession of two sets of DMSO respiratory systems is an adaptive strategy for WP3 survival in deep sea environments. We propose, for the first time, that deep sea microorganisms might be involved in global DMSO/DMS cycling.

Keywords: Shewanella, DMSO respiration, high pressure, low temperature, environmental adaptation

Introduction

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) concentrations in deep oceanic water are higher than 1.5 nM at depths up to 1,500 m in the equatorial Pacific Ocean and never drop below 1.3 nM at depths up to 4,000 m in the Arabian Sea (Hatton et al., 1996, 1998, 1999). It is thought to be an environmentally significant compound due to the potential role it plays in the biogeochemical cycle of the climatically active trace gas dimethyl sulfide (DMS; Hatton et al., 2005). DMSO can be produced either through the transformation of DMS by both photo-oxidation and bio-oxidation routes or by direct production from marine phytoplankton (Hatton et al., 1996; Simó, 1998; Moran et al., 2012). In addition to its roles in protecting cells against photo-generated oxidants and cryogenic damage, DMSO can also be used as an alternative electron acceptor for energy conservation through microbial dissimilatory reduction

(Sunda et al., 2002; Asher et al., 2011). Although DMSO acts as the dominant organic sulfur compound in deep oceanic water, the mechanism underlying DMSO bio-reduction by bathypelagic microorganisms is unknown.

Biochemical and genetic analyses of anaerobic DMSO respiration have been performed, particularly in Escherichia coli (McCrindle et al., 2005). In E. coli, two sets of operons are involved in DMSO respiration: the dmsABC operon and the ynfEFGHI operon, which is a paralog of the former and is likely to be phenotypically silent (Lubitz and Weiner, 2003). The dmsABC operon encodes the three functional proteins DmsA (the molybdopterin cofactor-containing subunit of the DMSO reductase), DmsB (the ion-sulfur subunit), and DmsC (the NapC-like integral membrane anchor). These three subunits constitute a functional DMSO reductase that is anchored to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane by DmsC. The electron released by menaquinol (MQH2) oxidation by DmsC is transferred via a series of [4Fe-4S] clusters in DmsB to the catalytic subunit DmsA, which reduces DMSO to DMS (Stanley et al., 2002).

Shewanella is a genus of facultative anaerobic, Gram-negative microorganisms that are widely distributed in marine and freshwater environments. The hallmark of Shewanella is their ability to utilize a broad range of terminal electron acceptors, which makes them outstanding candidates for potential applications in the bioremediation of pollutants (Nealson and Scott, 2006; Hau and Gralnick, 2007). In Shewanella species, the DMSO reduction pathway has been characterized only in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, which was isolated from the sediment of Oneida Lake in New York (Venkateswaran et al., 1999). Two dms operons were found in the MR-1 genome, although only one of them mediated DMSO reduction under the tested conditions (Gralnick et al., 2006; Fredrickson et al., 2008).

Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 was isolated from a west Pacific deep sea sediment at a depth of 1,914 m (Wang et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2007). Our previous study demonstrated that WP3 was able to utilize DMSO as a terminal electron acceptor for anaerobic growth (Xiao et al., 2007). However, the precise mechanism of anaerobic DMSO respiration by WP3 is still unknown. In this study, we showed that WP3 contained two dms gene clusters (type I and type II), both of which were functional; type I was essential for the ability of WP3 to thrive under in situ conditions (4°C/20 MPa) and type II was more important under other extreme conditions (i.e., 20°C/20 MPa or 4°C/0.1 MPa). The possession of two sets of DMSO respiratory systems is suggested to be an adaptive strategy for WP3 to cope with extreme deep sea environments.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strain WM3064 was routinely grown in Luria Broth medium at 37°C with the addition of 500 μM 2,6-diaminopimelic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo, USA). For aerobic growth, the S. piezotolerans WP3 strains were cultured in 2216E broth (Wang et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2011) with minor modifications (5 g l-1 tryptone, 1 g l-1 yeast extract, and 34 g l-1 NaCl) at 20°C in a rotary shaker at 200 rpm. If necessary, chloramphenicol was added to both media (30 μg ml-1 for E. coli strains and 10 μg ml-1 for WP3 strains). For the anaerobic growth assay, the cultivation of WP3 strains was performed in 2216E broth supplemented with 20 mM lactate and 25 mM DMSO (Burns and DiChristina, 2009). Serum bottles each containing 100 ml of fresh medium were prepared anaerobically by flushing with nitrogen gas through the butyl rubber stopper fixed with a metal seal to strip the dissolved oxygen prior to autoclave sterilization. To examine the growth of the WP3 strains at high hydrostatic pressure, each culture was grown to stationary phase in 2216E medium at 1 atm (1 atm = 0.101 MPa) and 20°C in a rotary shaker. The late-log phase cultures were diluted into the same medium to an optical density of 0.3 at 600 nm. Aliquots of the diluted culture (1 ml) were injected into serum bottles containing 100 ml of anaerobic medium through the butyl rubber stopper. After brief shaking, 2.5 ml disposable syringes were used to distribute the culture in 2 ml aliquots. The syringes with needles were stuck into rubber stoppers in a vinyl anaerobic airlock chamber (Coy Laboratory Products Inc., Grass Lake, MI, USA). Then, the syringes were incubated at a hydrostatic pressure of 20 MPa at 4°C or 20°C in stainless steel vessels (Feiyu Science and Technology Exploitation Co., Ltd, Nantong, China) that could be pressurized using water and a hydraulic pump. These systems were equipped with quick-connect fittings for rapid decompression and recompression (Yayanos and Van Boxtel, 1982; Allen et al., 1999).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids.

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| WM3064 | Donor strain for conjugation; ΔdapA | Gao et al. (2006) |

| S. piezotolerans WP3 | ||

| WT | Wild type strain | Lab stock |

| ΔdmsA1 | dmsA1 single mutant derived from WT | This study |

| ΔdmsA2 | dmsA2 single mutant derived from WT | This study |

| ΔΔdmsA | dmsA1 and dmsA2 double mutant derived from WT | This study |

| ΔdmsB1 | dmsB1 single mutant derived from WP3 | This study |

| ΔdmsB2 | dmsB2 single mutant derived from WP3 | This study |

| ΔΔdmsB | dmsB1 and dmsB2 double mutant derived from WP3 | This study |

| ΔΔdmsA-dmsA1-C | Complemented strain of ΔΔdmsA double mutant | This study |

| ΔΔdmsA-dmsA2-C | Complemented strain of ΔΔdmsA double mutant | This study |

| ΔΔdmsA-pSW2 | ΔΔdmsA double mutant containing the empty pSW2 vector as negative control | This study |

| ΔΔdmsB-dmsB1-C | Complemented strain of ΔΔdmsB double mutant | This study |

| ΔΔdmsB-dmsB2-C | Complemented strain of ΔΔdmsB double mutant | This study |

| ΔΔdmsB-pSW2 | ΔΔdmsB double mutant containing the empty pSW2 vector as negative control | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pSW2 | Chloramphenicol resistance, generated from filamentous bacteriophage SW1; used for complementation | Yang et al. (2015) |

| pSW2-dmsA1 | pSW2 containing dmsA1 and the promoter region of dmsA2 | This study |

| pSW2-dmsA2 | pSW2 containing dmsA2 and its own promoter region | This study |

| pSW2-dmsB1 | pSW2 containing dmsB1 and the promoter region of dmsB2 | This study |

| pSW2-dmsB2 | pSW2 containing dmsB2 and its own promoter region | This study |

| pRE112 | Chloramphenicol resistance, suicide plasmid with sacB1 gene as a negative selection marker; used for gene deletion | Lab stock |

| pRE112-ΔdmsA1 | pRE112 containing the PCR fragment for deleting dmsA1 | This study |

| pRE112-ΔdmsA2 | pRE112 containing the PCR fragment for deleting dmsA2 | This study |

| pRE112-ΔdmsB1 | pRE112 containing the PCR fragment for deleting dmsB1 | This study |

| pRE112-ΔdmsB2 | pRE112 containing the PCR fragment for deleting dmsB2 | This study |

RT-PCR, reverse transcription-PCR.

Deletion Mutagenesis and Complementation in S. piezotolerans WP3

In-frame deletion mutagenesis of dmsA1 (swp3459) was performed as previously reported (Chen et al., 2011). The primers designed to amplify PCR products for mutagenesis are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. To construct a dmsA1 in-frame deletion mutant, two fragments flanking dmsA1 were amplified by PCR. Fusion PCR products were generated using the amplified PCR fragments as templates with primers swp3459-UF and swp3459-DR. After digestion with the restriction enzymes SmaI and XbaI, the treated fusion PCR products were ligated into the SmaI and XbaI sites of the suicide plasmid pRE112 (Edwards et al., 1998), resulting in the mutagenesis vector pRE112-ΔdmsA1. This vector was first introduced into E. coli WM3064 and then conjugated into WP3-WT (wild type). Positive exconjugants were spread onto marine agar 2216E plates supplemented with 10% (w/v) sucrose. The chloramphenicol-sensitive and sucrose-resistant colonies were screened by PCR for the dmsA1 deletion. The same strategy was used to construct ΔdmsA2 single mutants. The double mutant ΔdmsA1ΔdmsA2 (ΔΔdmsA) was constructed by introducing pRE112-dmsA2 into ΔdmsA1. To construct the complemented strain of ΔdmsA1ΔdmsA2, the intact dmsA1 and dmsA2 gene fragments were amplified from the WT genomic DNA. The resulting PCR products were inserted into the shuttle vector pSW2, which was developed from the filamentous phage SW1 of WP3 (Yang et al., 2015). Transformants ΔΔdmsA-dmsA1-C and ΔΔdmsA-dmsA2-C were obtained by introducing the recombinant plasmids pSW2-dmsA1 and pSW2-dmsA2, respectively, into the ΔΔdmsA strain via conjugation.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

Total RNA was extracted from the WP3 strains as previously described (Wang et al., 2009). Briefly, cells in mid-log phase were harvested by centrifugation and treated with the TRI Reagent RNA/DNA/protein isolation kit (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove residual genomic DNA and quantified using the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by reverse transcription reaction with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD, USA) to obtain cDNA.

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Primer pairs (Supplementary Table S1) for the genes selected for the RT-PCR analysis were designed using the Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). Transcription assays were performed using the 7500 System SDS software in reaction mixtures with total volumes of 20 μl containing 10 μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK), 0.5 μM of each primer, and 1.2 μl of the cDNA template. The amount of target was normalized to the reference gene swp2079 (Li et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). The RT-PCR assays were performed in triplicate for each sample and a mean value and standard deviations were calculated for the relative RNA expression levels.

DMSO Concentration Determination

Aliquots (1 ml) of the culture recovered at different time points were filtered immediately through 0.22 μm Millex-GP filters (Millipore, Carrigtwohill, Ireland) and stored at -70°C prior to use. The DMSO concentration was determined as previously reported (Cheng et al., 2013). Briefly, the samples were applied for analysis by an Agilent 1200 series high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with a diode-array detector set at 210 nm. DMSO was separated using an Aminex HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 50°C using H2SO4 (5 mM) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min-1. Commercially available DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to generate a calibration curve to estimate the DMSO concentration.

Results

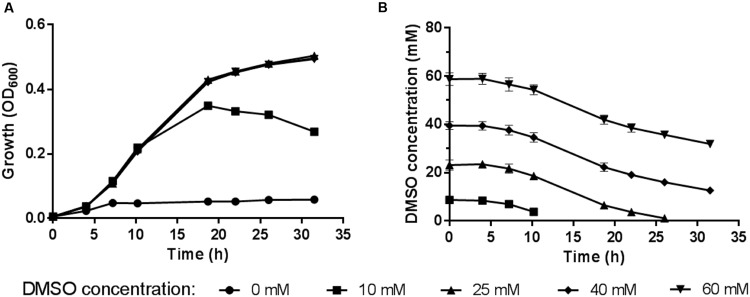

Determination of the Optimum DMSO Concentration for WP3 Anaerobic Respiration

The 2216E medium supplemented with sodium lactate and DMSO was used to study the anaerobic DMSO respiration of WP3. The time course of the DMSO concentration was monitored by assessing the cell density (represented by OD600) in the medium (Figure 1). The maximum growth was observed at a DMSO concentration of 25 mM, at which concentration the DMSO in the medium was exhausted and the cells were entering stationary phase. We found no significant differences in the cell density and DMSO consumption with a further increase in the DMSO concentration (40 or 60 mM) compared with growth at the 25 mM concentration, suggesting that excess DMSO (40 or 60 mM) had no positive effect on the growth yield. Therefore, the subsequent physiological experiments were performed with DMSO at a concentration of 25 mM.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Growth of S. piezotolerans WP3 in 2216E medium using different DMSO concentrations as the sole electron acceptor. (B) Time course of DMSO consumption by S. piezotolerans WP3. The data shown represent the results of two independent experiments and the error bars represent standard deviations of the averages of triplicate cultures.

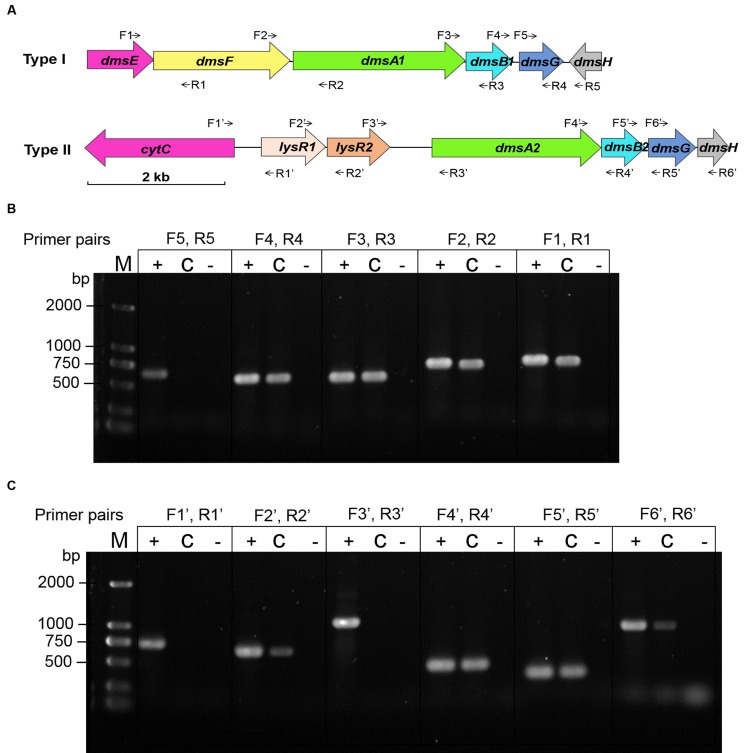

Organization of the dms Gene Clusters in WP3

Two sets of dms gene clusters [type I (dmsEFA1B1G1H1 and swp3461-swp3456) and type II (dmsA2B2G2H2 and swp0724-swp0728)] were identified according to the WP3 genome annotation (Figure 2A). The type I dms gene cluster matches the archetypal dmsEFABGH organization. However, no dmsE or dmsF homologous gene was found upstream of dmsA2B2G2H2 in the type II dms gene cluster. Additionally, two partially overlapped genes encoding the LysR family regulator were located directly upstream of dmsA2. To investigate whether these two operons were truly polycistronic, reverse transcription PCR was performed to amplify the intergenic regions of neighboring genes. Our data demonstrated that five genes (dmsEFA1B1G1) in the type I dms gene cluster were co-transcribed, with the exception of swp3456 (Figure 2B). For the type II dms gene cluster, four genes (dmsA2B2G2H2) were co-transcribed as a single operon (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Co-transcriptional analysis of the type I and type II dms gene operons in S. piezotolerans WP3. (A) The operon organization of the two dms gene clusters. Arrows indicate primer pairs spanning adjacent genes used for the co-transcription analysis. (B) Co-transcriptional analysis of the type I gene operon (dmsEFA1B1G1H1). (C) Co-transcriptional analysis of the type II gene operon (dmsA2B2G2H2). The different templates used for each co-transcription confirmation are presented as follows: +, WP3 genomic DNA (positive control); -, distilled water (negative control); and C, WP3 cDNA. The primer pairs used in each assay are indicated as follows: dmsE-F For/Rev (F1, R1); dmsF-A1 For/Rev (F2, R2); dmsA1-B1 For/Rev (F3, R3); dmsB1-G1 For/Rev (F4, R4); dmsG1-H1 For/Rev (F5, R5); cytC-lysR1 For/Rev (F1′, R1′); lysR1-R2 For/Rev (F2′, R2′); lysR2-dmsA2 For/Rev (F3′, R3′); dmsA2-B2 For/Rev (F4′, R4′); dmsB2-G2 For/Rev (F5′, R5′); and dmsG2-H2 For/Rev (F6′, R6′). The resulting amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis using 1.0% agarose gels with GelRed staining.

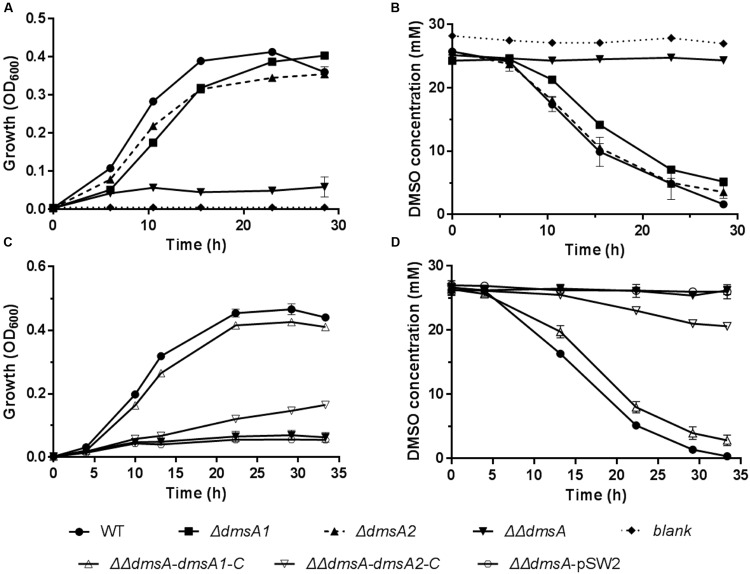

Both dms Gene Clusters in WP3 Were Functional in DMSO Respiration

To test whether both dms gene clusters were responsible for DMSO respiration, we initially monitored the transcription of both dms gene clusters using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). The results showed that both gene clusters were significantly induced under anaerobic DMSO conditions (Supplementary Figure S1). Because dmsA encodes the large catalytic subunit of the DMSO reductase and plays an essential role in DMSO respiration (Trieber et al., 1996), dmsA of these two gene clusters was inactivated and in-frame deletion mutants were constructed. The growth assay performed at 20°C/0.1 MPa demonstrated that the single mutants ΔdmsA1 and ΔdmsA2 retained the ability to use DMSO for anaerobic growth, whereas the double mutant ΔΔdmsA (namely ΔdmsA1ΔdmsA2) failed to grow in the same medium (Figure 3A) and did not consume DMSO (Figure 3B). To confirm that the loss of DMSO-dependent growth of ΔΔdmsA was caused by the disruption of dmsA1 and dmsA2, two complemented strains (ΔΔdmsA-dmsA1-C and ΔΔdmsA-dmsA2-C) were generated. As expected, the introduction of either dmsA1 or dmsA2 into ΔΔdmsA partially restored the ability of the double mutant to utilize DMSO for anaerobic growth (Figures 3C,D). Because dmsB encoded the small ion-sulfur subunit of the DMSO reductase, we constructed corresponding in-frame deletion mutants (ΔdmsB1, ΔdmsB2, and ΔdmsB1ΔdmsB2) and complemented strains (ΔΔdmsB-dmsB1-C and ΔΔdmsB-dmsB2-C). Similar results were observed in the growth yields and DMSO consumption of these strains (Supplementary Figure S2). Taken together, these data indicated that both the type I and type II dms gene clusters were responsible for DMSO respiration.

FIGURE 3.

Growth and corresponding DMSO consumption curves of the WP3 mutants at 20°C/0.1 MPa using DMSO as the sole electron acceptor. (A,B) Growth and corresponding DMSO consumption curves of WP3 single and double mutants; (C,D) Growth and corresponding DMSO consumption curves of WP3 complemented strains. The data shown represent the results of two independent experiments and the error bars represent standard deviations of averages of triplicate cultures.

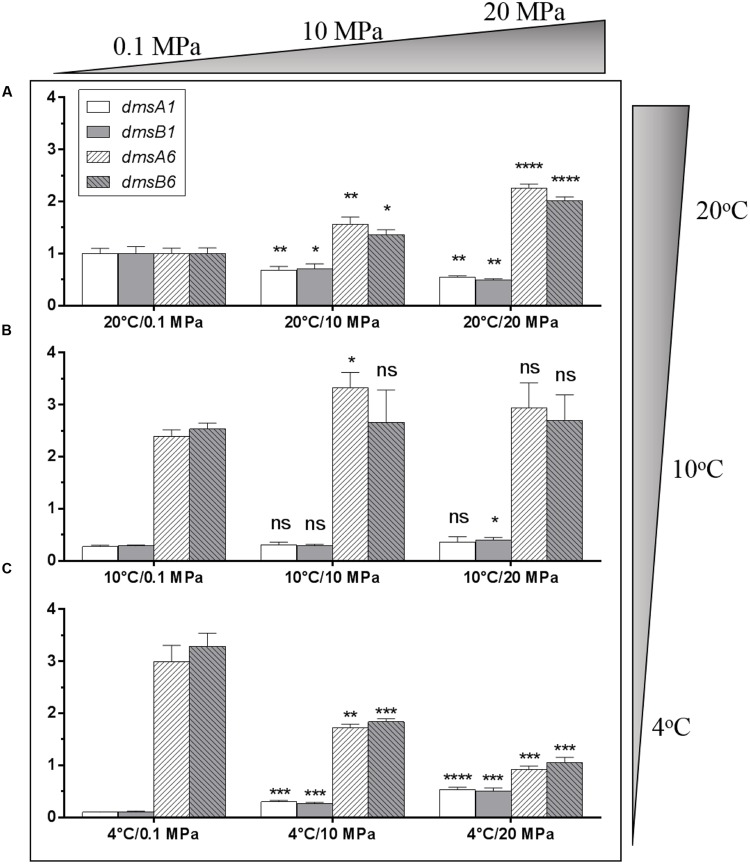

Transcription of the Two dms Gene Clusters Was Affected by Pressure and Temperature Changes

To evaluate whether these two dms gene clusters were involved in DMSO respiration at different temperatures (4 and 20°C) and pressures (0.1 and 20 MPa), relative transcription assays of these two clusters were performed by qRT-PCR. The cells were incubated in anaerobic DMSO medium under different growth conditions for RNA extraction. Compared to the expression levels of the two dms gene clusters at 20°C/0.1 MPa, the expression of the type I cluster was significantly down-regulated with pressure increased from atmospheric pressure (0.1 MPa) to high pressure (10 and 20 MPa) conditions, whereas the expression of type II cluster was significantly up-regulated under the same conditions (Figure 4A). In contrast, the expression profiles of two dms gene clusters at 10°C were generally similar regardless of pressure changes (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the expression profiles of type I dms clusters at 4°C were significantly induced with pressure increased from atmospheric pressure to high pressure (10 and 20 MPa) conditions, whereas the expression profiles of type II dms clusters were greatly reduced under the same conditions (Figure 4C). Collectively, these data suggested that the transcription of the two dms clusters was regulated in response to pressure and temperature changes.

FIGURE 4.

Transcriptional analysis of two dms gene operons in S. piezotolerans WP3 under different pressure and temperature conditions. (A) WP3 grown at 20°C under different pressures; (B) WP3 grown at 10°C under different pressures; (C) WP3 grown at 4°C under different pressures. The data were normalized to the 20°C/0.1 MPa anaerobic conditions. The data shown represent the results of two independent experiments and the error bars represent standard deviations of averages of triplicate experiments. At each temperature, P-value reflects gene transcription differences between atmospheric pressure and high pressure conditions. ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 (Student’s t-test); ns, no significant difference.

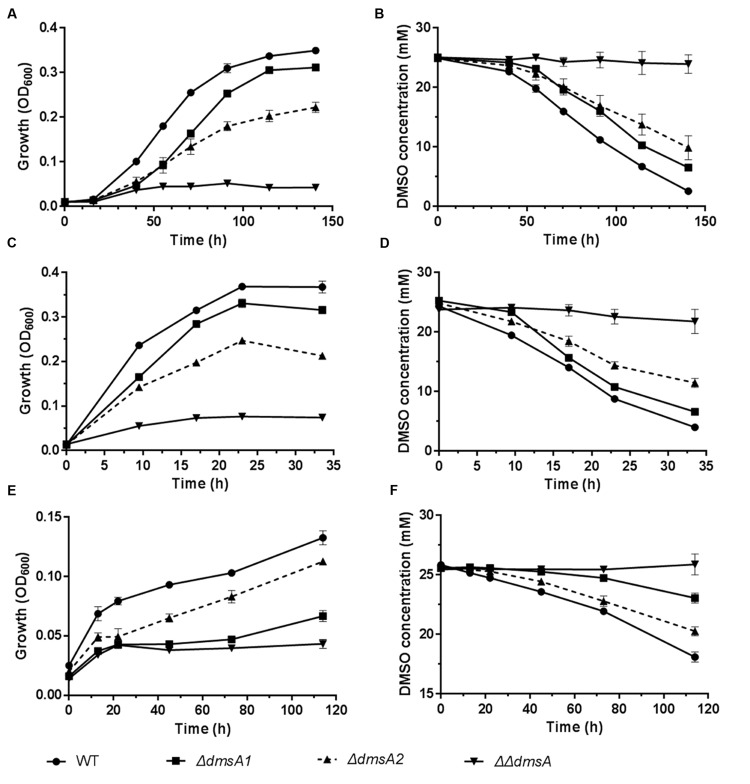

The Contribution of the Two dms Gene Clusters to WP3 Growth was Influenced by Pressure and Temperature

To investigate whether the two dms gene clusters were involved in deep sea environmental adaptation, a growth assay was performed at different pressures and temperatures. As predicted, ΔdmsA1 exhibited a higher growth yield than ΔdmsA2 when the growth temperature decreased from 20 to 4°C or the pressure increased from 0.1 to 20 MPa (Figures 5A,C), which indicated that the type II dms operon was more important than the type I operon at low temperature or high pressure. Additionally, culture media collected at different time points were filtered and then analyzed to assess DMSO consumption by these strains. The HPLC results indicated that the ΔdmsA1 mutant exhibited higher DMSO consumption (Figures 5B,D) than ΔdmsA2 at 4°C/0.1 MPa or 20°C/20 MPa.

FIGURE 5.

Growth and corresponding DMSO consumption curves of WP3 mutants at different temperatures and pressures with DMSO as the sole electron acceptor. (A,B) 4°C and 0.1 MPa; (C,D) 20°C and 20 MPa; (E,F) 4°C and 20 MPa. The data shown represent the results of two independent experiments and the error bars represent standard deviations of averages of triplicate cultures.

Interestingly, when these strains were incubated at 4°C/20 MPa, the growth of ΔdmsA2 appeared to be higher than ΔdmsA1 (Figure 5E), which was consistent with the more efficient DMSO consumption by ΔdmsA2 in the medium (Figure 5F). Additionally, our results showed that the DMSO-dependent growth yield conferred by the presence of the two dms operons was higher than the growth yield conferred by either of the two dms operons alone, indicating that the presence of both dms operons was essential for the DMSO-dependent growth of WP3 under in situ deep sea conditions.

Discussion

DMSO and DMS are interchangeable substrates in marine environments through the bio-reduction and bio-oxidation pathways (Bürgmann et al., 2007; Muyzer and Stams, 2008; Rellinger et al., 2009; Spiese et al., 2009). As a volatile anti-greenhouse gas, DMS plays an important climatic role in cloud nucleation and hence may influence the global temperature (Charlson et al., 1987; Andreae, 1990; Curson et al., 2011). Previous study demonstrated that DMSO as a substantial sink or source for DMS (Hatton et al., 1996). The formation of DMSO would therefore lead to the removal of DMS from sea water, effectively limiting the quantity of DMS available for releasing into the atmosphere (Hatton et al., 2005). Although DMSO has been detected in abyssal ocean water (Hatton et al., 1999), few data are available on the turnover mechanisms of DMSO in deep sea environments. In this study, our results demonstrate a previously unrecognized role for biotic DMSO reduction as an important pathway of DMS production in the deep sea environment.

In the abyssal ocean, metabolic energy is harnessed from the coupling of redox reactions (Orcutt et al., 2011). Microorganisms exploit the available chemical energy by developing strategies to overcome the activation energy of reaction. The metabolic activities of microorganisms in such environment depend on the availability and speciation of electron donors and acceptors (Froelich et al., 1979). As for DMSO, the E0′ value for its reduction (+160 mV) lies between those for fumarate/succinate (+33 mV) and nitrate/nitrite (+433 mV; Thauer et al., 1977; Wood, 1981), and thus the coupling of DMSO reduction to ATP synthesis presents no energetic difficulty. Accordingly, some culturable bacteria isolated from marine environments have also shown the ability to grow by anaerobic DMSO respiration (Jonkers et al., 1996; Süß et al., 2008). Although sulfate is the most abundant oxidized sulfur species in the dark ocean (Orcutt et al., 2011), the reduction of sulfate yields less energy than that of DMSO, and DMSO could therefore be consumed preferentially.

In Shewanella species, the DMSO reduction pathway was first characterized in S. oneidensis MR-1, which was a strain isolated from the sediment of Oneida Lake in New York (Venkateswaran et al., 1999). Two dms operons were found in the MR-1 genome; however, only one dms operon mediated DMSO reduction under the tested conditions (Gralnick et al., 2006). In contrast to the results in MR-1, both dms gene operons in WP3 were functional (Figure 3). Moreover, our results demonstrated that the presence of both operons was essential for the maximum growth of WP3 using DMSO as the sole electron acceptor (Figure 5). Type I matches the archetypal dmsEFABGH organization, which enables the DMSO reductase to localize to the outer membrane of Shewanella and allows the cells to respire DMSO more efficiently (Gralnick et al., 2006). Additionally, type I plays a dominant role in the DMSO-dependent growth of WP3 under in situ deep sea conditions (4°C/20 MPa). Type II is more similar to E. coli (dmsABC organization; Stanley et al., 2002) and may locate in the periplasmic space. The physiological analysis indicated that type II was more important for DMSO-dependent growth than type I under some stressful conditions (i.e., 20°C/20 MPa and 4°C/0.1 MPa).

To evaluate the impact of the two DMSO respiration systems on growth, we calculated the DMSO consumption of the WP3 mutants by standardizing the growth yield to the same cell density (1 OD unit ≈ 1.5 × 108 cells; Supplementary Figure S3). Our data showed that WT (type I and type II together) and ΔdmsA1 (type II alone) required less DMSO than ΔdmsA2 (type I alone) to reach the same growth yield when incubated at 20°C/0.1 MPa, 4°C/0.1 MPa, or 20°C/20 MPa, indicating that type II was a more efficient DMSO respiration system at atmospheric pressure or 20°C. However, when the WP3 mutants were incubated at 4°C/20 MPa, ΔdmsA2 (type I alone) inversely required less DMSO than ΔdmsA1 (type II alone), indicating that type I was more efficient than type II under the 4°C/20 MPa in situ condition. Collectively, our results suggest that the possession of multiple systems with similar functions might be an adaptive strategy for bacteria to cope with extreme deep sea environments. Similar adaptive mechanisms can also be found in other deep sea-derived Shewanella strains. For example, Shewanella putrefaciens W3-18-1 (Sediment; under 630 m of oxic water) has been identified to contain two functional nap gene clusters (nap-α and nap-β), and the nitrate respiration in W3-18-1 starts earlier than that in MR-1 (with nap-β only) under microoxic conditions (Qiu et al., 2013). In another Shewanella strain, Shewanella violacea DSS12 (Sediment; 5,110 m), it possesses more terminal oxidases with different affinities for oxygen and less terminal reductases, implying that DSS12 has undergone respiratory adaptation to aerobiosis in the upper layer of deep sea sediments (Aono et al., 2010).

The physiological results concerning the possession of two DMSO respiration systems in WP3 are quite different from those of the two NAP systems in WP3. Although two nitrate respiration systems (nap-α and nap-β) were identified in the WP3 genome, further studies demonstrated that WP3 possessing nap-α alone was more competitive than the strain possessing both nap-α and nap-β during nitrate-dependent growth. Thus containing a single nap-α system should be the evolutionary direction for Shewanella to thrive at low temperature (Chen et al., 2011). By combining these results, we conclude that WP3 can utilize different strategies to evolve its different anaerobic respiration systems in response to deep sea environments.

The effects of pressure on the respiratory systems has been well studied in S. violacea DSS12. Although very few terminal reductases for anaerobic respiration being identified in DSS12 genome, it processes at least five sets of putative terminal oxidases for aerobic respiration (Aono et al., 2010), in which the expression of cytochrome bd (quinol oxidase) was enhanced under high pressure (Tamegai et al., 2005). In addition, the d-type terminal oxidase of DSS12 was identified to be pressure-resistant and functional under high pressure conditions (Chikuma et al., 2007). Further research demonstrated that the piezotolerance of the Shewanella terminal oxidase activity perhaps depends on the intrinsic properties of the enzymes themselves but not their membrane lipid composition (Tamegai et al., 2011). In contrast, the piezophilic property of terminal oxidases in Photobacterium profundum SS9 (amphipod; 2,500 m) seems to be different. For one thing, the cytochrome content of P. profundum SS9 was not affected by altered pressure during growth; for another, genes encoding cytochromes showed no significant change in expression under different pressures during growth of P. profundum SS9. However, the piezotolerance of P. profundum SS9 terminal oxidase activity could also be observed using cells grown under higher pressures (Tamegai et al., 2012). Collectively, piezophiles from distinct genus may choose different strategies in adaptating to high pressure.

More recently, the respective effects of temperature and pressure on Fe(III) reduction rates (FeRRs) and viability have been investigated in deep sea bacterium Shewanella profunda LT13a (sediment; 4,500 m; Picard et al., 2015). Results showed that FeRR increased linearly with temperature between 4 and 37°C, while the highest FeRR was observed between 10 and 40 MPa and then slightly decreased with increasing pressure (40–110 MPa), indicating that the respiratory chain was not immediately affected by pressure (Picard et al., 2015). Under high pressure conditions, the significantly increased energy demand for cell maintenance of S. profunda LT13a may account for its decreased viability (Picard et al., 2015). Here we observed that DMSO-dependent growth can occur when WP3 is incubated in 4°C/20 MPa conditions (Figure 5E), suggesting that the energy demand of WP3 could still be fulfilled under in situ conditions with DMSO as the sole electron acceptor.

Because the transcription profiles of these two dms gene clusters vary significantly in response to pressure or temperature changes (Figure 4), it is important to elucidate the mechanism by which dms gene clusters are regulated. Previously, a mutant lacking the fur gene (encoding the ferric uptake regulator) was found to be severely deficient in DMSO respiration in WP3 (Yang et al., 2013), indicating that Fur was the dms gene cluster regulator. Moreover, cAMP receptor protein (CRP) was also found to directly regulate the expression of the dms gene cluster in S. oneidensis MR-1 (Zhou et al., 2013). We predicted the transcriptional regulation motifs of both dms gene clusters in WP3 and found similar CRP binding motifs (data not shown). Taken together, the presence of the CRP and Fur binding motifs might be an alternative regulatory strategy for WP3 to cope with pressure or temperature changes in a subtle regulatory mechanism. Investigation into this mechanism is currently underway and will be described as part of a separate report.

Conclusion

We have shown that two dms operons found in S. piezotolerans WP3 are functional in DMSO respiration. Both dms gene clusters are essential for the maximum growth of WP3 under low temperature and high pressure conditions; the type I system is essential for the ability of WP3 to thrive under in situ conditions (4°C/20 MPa), whereas the type II system is more important under other stressful conditions (i.e., 4°C/0.1 MPa and 20°C/20 MPa). Based on these data, we propose that multiple copies of dms gene clusters may confer a competitive advantage to the ability of WP3 to thrive under a broader range of environmental conditions. Thus, deep sea microorganism-mediated DMSO reduction may contribute to the global DMS cycle, which has been neglected in previous studies.

Author Contributions

LX, HJ, and XX designed the study, analyzed the data. LX and YZ participated in the experiments. LX and HJ wrote the manuscript and XX critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31290232), the China Ocean Mineral Resources R & D Association (Grant No. DY125-22-04), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41306129, 91228201, 91428308).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01418

References

- Allen E. E., Facciotti D., Bartlett D. H. (1999). Monounsaturated but not polyunsaturated fatty acids are required for growth of the deep-sea bacterium Photobacterium profundum SS9 at high pressure and low temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 1710–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae M. O. (1990). Ocean-atmosphere interactions in the global biogeochemical sulfur cycle. Mar. Chem. 30 1–29. 10.1016/0304-4203(90)90059-l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aono E., Baba T., Ara T., Nishi T., Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., et al. (2010). Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of Shewanella violacea, a psychrophilic and piezophilic bacterium from deep sea floor sediments. Mol. BioSyst. 6 1216–1226. 10.1039/c000396d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher E. C., Dacey J. W., Mills M. M., Arrigo K. R., Tortell P. D. (2011). High concentrations and turnover rates of DMS, DMSP and DMSO in Antarctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38:L23609 10.1029/2011GL049712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bürgmann H., Howard E. C., Ye W., Sun F., Sun S., Napierala S., et al. (2007). Transcriptional response of Silicibacter pomeroyi DSS-3 to dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). Environ. Microbiol. 9 2742–2755. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns J. L., DiChristina T. J. (2009). Anaerobic respiration of elemental sulfur and thiosulfate by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 requires psrA, a homolog of the phsA gene of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium LT2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 5209–5217. 10.1128/AEM.00888-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson R. J., Lovelock J. E., Andreae M. O., Warren S. G. (1987). Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature 326 655–661. 10.1038/326655a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Wang F., Xu J., Mehmood M. A., Xiao X. (2011). Physiological and evolutionary studies of NAP systems in Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. ISME J. 5 843–855. 10.1038/ismej.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.-Y., Li B.-B., Li D.-B., Chen J.-J., Li W.-W., Tong Z.-H., et al. (2013). Promotion of iron oxide reduction and extracellular electron transfer in Shewanella oneidensis by DMSO. PLoS ONE 8:e78466 10.1371/journal.pone.0078466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikuma S., Kasahara R., Kato C., Tamegai H. (2007). Bacterial adaptation to high pressure: a respiratory system in the deep-sea bacterium Shewanella violacea DSS12. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 267 108–112. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curson A. R., Todd J. D., Sullivan M. J., Johnston A. W. (2011). Catabolism of dimethylsulphoniopropionate: microorganisms, enzymes and genes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9 849–859. 10.1038/nrmicro2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R. A., Keller L. H., Schifferli D. M. (1998). Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207 149–157. 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00619-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J. K., Romine M. F., Beliaev A. S., Auchtung J. M., Driscoll M. E., Gardner T. S., et al. (2008). Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 592–603. 10.1038/nrmicro1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froelich P. N., Klinkhammer G., Bender M. A. A., Luedtke N., Heath G. R., Cullen D., et al. (1979). Early oxidation of organic matter in pelagic sediments of the eastern equatorial Atlantic: suboxic diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 43 1075–1090. 10.1016/0016-7037(79)90095-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Yang Z. K., Wu L., Thompson D. K., Zhou J. (2006). Global transcriptome analysis of the cold shock response of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and mutational analysis of its classical cold shock proteins. J. Bacteriol. 188 4560–4569. 10.1128/jb.01908-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gralnick J. A., Vali H., Lies D. P., Newman D. K. (2006). Extracellular respiration of dimethyl sulfoxide by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 4669–4674. 10.1073/pnas.0505959103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton A., Malin G., Turner S., Liss P. (1996). “DMSO: a significant compound in the biogeochemical cycle of DMS,” in Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds, eds Kiene R. P., Visscher P. T., Keller M. D., Kirst G. O. (New York, NY: Plenum Press; ), 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- Hatton A., Turner S., Malin G., Liss P. (1998). Dimethylsulphoxide and other biogenic sulphur compounds in the Galapagos Plume. Deep Sea Res. Part 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 45 1043–1053. 10.1016/s0967-0645(98)00017-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton A. D., Darroch L., Malin G. (2005). “The role of dimethylsulphoxide in the marine biogeochemical cycle of dimethylsulphide,” in Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, eds Gibson R. N., Atkinson R. J. A., Gordon J. D. M. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hatton A. D., Malin G., Liss P. S. (1999). Distribution of biogenic sulphur compounds during and just after the southwest monsoon in the Arabian Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part 2 Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 46 617–632. 10.1016/s0967-0645(98)00120-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hau H. H., Gralnick J. A. (2007). Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61 237–258. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers H. M., Der Maarel M. J., Gemerden H., Hansen T. A. (1996). Dimethylsulfoxide reduction by marine sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 136 283–287. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08062.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Xiao X., Sun P., Wang F. (2008). Screening of genes regulated by cold shock in Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 and time course expression of cold-regulated genes. Arch. Microbiol. 189 549–556. 10.1007/s00203-007-0347-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz S. P., Weiner J. H. (2003). The Escherichia coli ynfEFGHI operon encodes polypeptides which are paralogues of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (DmsABC). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 418 205–216. 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrindle S. L., Kappler U., McEwan A. G. (2005). Microbial dimethylsulfoxide and trimethylamine-N-oxide respiration. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 50 147–198. 10.1016/s0065-2911(05)50004-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. A., Reisch C. R., Kiene R. P., Whitman W. B. (2012). Genomic insights into bacterial DMSP transformations. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 4 523–542. 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G., Stams A. J. (2008). The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 441–454. 10.1038/nrmicro1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H., Scott J. (2006). “Ecophysiology of the genus Shewanella,” in The Prokaryotes, ed.Dworkin M. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 1133–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt B. N., Sylvan J. B., Knab N. J., Edwards K. J. (2011). Microbial ecology of the dark ocean above, at, and below the seafloor. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75 361–422. 10.1128/mmbr.00039-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard A., Testemale D., Wagenknecht L., Hazael R., Daniel I. (2015). Iron reduction by the deep-sea bacterium Shewanella profunda LT13a under subsurface pressure and temperature conditions. Front. Microbiol. 5:796 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu D., Wei H., Tu Q., Yang Y., Xie M., Chen J., et al. (2013). Combined genomics and experimental analyses of respiratory characteristics of Shewanella putrefaciens W3-18-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 5250–5257. 10.1128/aem.00619-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellinger A. N., Kiene R. P., del Valle D. A., Kieber D. J., Slezak D., Harada H., et al. (2009). Occurrence and turnover of DMSP and DMS in deep waters of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part 1 Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 56 686–702. 10.1016/j.dsr.2008.12.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simó R. (1998). Trace chromatographic analysis of dimethyl sulfoxide and related methylated sulfur compounds in natural waters. J. Chromatogr. A 807 151–164. 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)00086-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiese C. E., Kieber D. J., Nomura C. T., Kiene R. P. (2009). Reduction of dimethylsulfoxide to dimethylsulfide by marine phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54 560–570. 10.4319/lo.2009.54.2.0560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley N. R., Sargent F., Buchanan G., Shi J., Stewart V., Palmer T., et al. (2002). Behaviour of topological marker proteins targeted to the Tat protein transport pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 43 1005–1021. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunda W., Kieber D. J., Kiene R. P., Huntsman S. (2002). An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature 418 317–320. 10.1038/Nature00851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Süß J., Herrmann K., Seidel M., Cypionka H., Engelen B., Sass H. (2008). Two distinct Photobacterium populations thrive in ancient Mediterranean sapropels. Microb. Ecol. 55 371–383. 10.1007/s00248-007-9282-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamegai H., Kawano H., Ishii A., Chikuma S., Nakasone K., Kato C. (2005). Pressure-regulated biosynthesis of cytochrome bd in piezo-and psychrophilic deep-sea bacterium Shewanella violacea DSS12. Extremophiles 9 247–253. 10.1007/s00792-005-0439-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamegai H., Nishikawa S., Haga M., Bartlett D. H. (2012). The respiratory system of the piezophile Photobacterium profundum SS9 grown under various pressures. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76 1506–1510. 10.1271/bbb.120237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamegai H., Ota Y., Haga M., Fujimori H., Kato C., Nogi Y., et al. (2011). Piezotolerance of the respiratory terminal oxidase activity of the piezophilic Shewanella violacea DSS12 as compared with non-piezophilic Shewanella species. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75 919–924. 10.1271/bbb.100882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thauer R. K., Jungermann K., Decker K. (1977). Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41 100–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieber C. A., Rothery R. A., Weiner J. H. (1996). Engineering a novel iron-sulfur cluster into the catalytic subunit of Escherichia coli dimethyl-sulfoxide reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 271 4620–4626. 10.1016/s0167-7012(97)00990-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswaran K., Moser D. P., Dollhopf M. E., Lies D. P., Saffarini D. A., MacGregor B. J., et al. (1999). Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Shewanella and description of Shewanella oneidensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49 705–724. 10.1099/00207713-49-2-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wang J., Jian H., Zhang B., Li S., Wang F., et al. (2008). Environmental adaptation: genomic analysis of the piezotolerant and psychrotolerant deep-sea iron reducing bacterium Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. PLoS ONE 3:e1937 10.1371/journal.pone.0001937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Wang P., Chen M., Xiao X. (2004). Isolation of extremophiles with the detection and retrieval of Shewanella strains in deep-sea sediments from the west Pacific. Extremophiles 8 165–168. 10.1007/s00792-003-0365-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Xiao X., Ou H.-Y., Gai Y., Wang F. (2009). Role and regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in the response of Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 to different temperatures and pressures. J. Bacteriol. 191 2574–2584. 10.1128/jb.00498-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood P. M. (1981). The redox potential for dimethyl sulphoxide reduction to dimethyl sulphide. FEBS Lett. 124 11–14. 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Wang P., Zeng X., Bartlett D. H., Wang F. (2007). Shewanella psychrophila sp. nov. and Shewanella piezotolerans sp. nov., isolated from west Pacific deep-sea sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 60–65. 10.1099/ijs.0.64500-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.-W., He Y., Xu J., Xiao X., Wang F.-P. (2013). The regulatory role of ferric uptake regulator (Fur) during anaerobic respiration of Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. PLoS ONE 8:e75588 10.1371/journal.pone.0075588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.-W., Jian H.-H., Wang F.-P. (2015). pSW2, a novel low-temperature-inducible gene expression vector based on a filamentous phage of the deep-sea bacterium Shewanella piezotolerans WP3. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 5519–5526. 10.1128/aem.00906-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayanos A. A., Van Boxtel R. (1982). Coupling device for quick high-pressure connections to 100 MPa. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 53 704–705. 10.1063/1.1137011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G., Yin J., Chen H., Hua Y., Sun L., Gao H. (2013). Combined effect of loss of the caa3 oxidase and Crp regulation drives Shewanella to thrive in redox-stratified environments. ISME J. 7 1752–1763. 10.1038/ismej.2013.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.