Abstract

Motivation: One of the main goals of large scale methylation studies is to detect differentially methylated loci. One way is to approach this problem sitewise, i.e. to find differentially methylated positions (DMPs). However, it has been shown that methylation is regulated in longer genomic regions. So it is more desirable to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs) instead of DMPs. The new high coverage arrays, like Illuminas 450k platform, make it possible at a reasonable cost. Few tools exist for DMR identification from this type of data, but there is no standard approach.

Results: We propose a novel method for DMR identification that detects the region boundaries according to the minimum description length (MDL) principle, essentially solving the problem of model selection. The significance of the regions is established using linear mixed models. Using both simulated and large publicly available methylation datasets, we compare seqlm performance to alternative approaches. We demonstrate that it is both more sensitive and specific than competing methods. This is achieved with minimal parameter tuning and, surprisingly, quickest running time of all the tried methods. Finally, we show that the regional differential methylation patterns identified on sparse array data are confirmed by higher resolution sequencing approaches.

Availability and Implementation: The methods have been implemented in R package seqlm that is available through Github: https://github.com/raivokolde/seqlm

Contact: rkolde@gmail.com

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

DNA methylation is an important cellular mechanism that is associated to processes like X-chromosome inactivation and genomic imprinting. It has also been related to several diseases such as diabetes, schizophrenia and cancer (Baylin and Jones, 2011; Mill et al., 2008; Toperoff et al., 2012). In recent years the role of methylation in various diseases has received considerable interest from the research community. This can be attributed largely to the development of high-density methylation microarrays, like Illumina Infinium 450K, which have made affordable the characterization of genome-wide methylation patterns on large disease related cohorts.

The Illumina 450K microarray covers around 20 CpG sites per gene. Such resolution reveals a spatially correlated structure of DNA methylation. Closely situated CpG sites often display almost identical methylation patterns. This feature has been seen already in the early sequencing studies (Eckhardt et al., 2006) and it has been also shown that methylation is regulated in longer regions (Lienert et al., 2011). While strong spatial correlation is a dominant feature in the data, common analysis methods do not take this into account. For example, differential methylation analysis is commonly performed in a sitewise manner (Marabita et al., 2013; Wessely and Emes, 2012), thus ignoring correlations between probes. To take spatial correlations into account when performing the analysis, it is natural to search for differentially methylated regions (DMRs) instead of sites. Statistically, it could improve the sensitivity of the analysis and make the results less redundant. Biologically, differential methylation supported by multiple independent probes is less likely to represent an experimental artefact. DMR centric analysis has been performed in multiple studies (Bell et al., 2012; Lokk et al., 2014; Slieker et al., 2013) and there are several tools available for it (Jaffe et al., 2012; Pedersen et al., 2012; Sofer et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2012).

However, despite the numerous tools available, there is no standard approach for DMR identification. One possibility is to use predefined regions that are based on genomic features such as gene parts or CpG islands. This has been implemented in an R package IMA (Wang et al., 2012), but it has several shortcomings. Such an analysis often reveals large amount of regions that cover the same set of differentially methylated sites, while their rankings are more based on the concordance between the borders of true DMRs and predefined regions than the true extent of differential methylation.

Another, a more general approach is to define the regions dynamically based on the data. One such method is Comb-p (Kechris et al., 2010; Pedersen et al., 2012) that combines single site P-values by using sliding windows and taking into account the correlation between sites. This method operates on P-values, which makes it flexible and computationally efficient. However, the DMRs are then based on summary statistics and this may lose some information compared to modeling directly on the measurements. Also, the user must pick the minimum P-value required to start a region, and the resulting regions strongly depend on this parameter value.

Maybe the most well-known method is bump hunting (Jaffe et al., 2012), integrated into R package minfi (Aryee et al., 2014). Essentially, it performs site-level analysis on spatially smoothed data and then applies some rules to aggregate the sites into regions. Significance of these regions is assessed using permutations. The number and nature of bumphunter results depends strongly on the effect size cutoff and smoothing window size parameters that are hard to interpret in biological terms and thus tricky to optimize. Second, due to smoothing the method is unable to detect single-site differential methylation (Jaffe et al., 2012), making it less effective in sparsely covered regions.

Another tool Aclust (Sofer et al., 2013) defines the regions by gradually clustering the consecutive sites together. The significance of identified clusters is tested using the Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model. This approach relies on an even larger number of user-defined parameters, such as correlation metric, agglomeration method, correlation threshold, etc.

In this article we present a novel method for identifying DMRs. Probes are grouped into regions based similarity of differential methylation profiles by using the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle. The significance of these regions is estimated using linear mixed models. Such an information theoretic background makes the model flexible in a variety of situations without the need of extensive parameter tuning. For validation, we show that our approach is effective in finding true DMRs while appropriately controlling the number of false positives both on simulated and real methylation datasets.

2 Approach

Biologically, a differentially methylated region is a rather intuitive concept—a collection of consecutive metylation sites in the DNA where the average methylation levels differ significantly between the tissues of interest. However, the intuition does not translate into clear definition that could be used for DMR finding. For example, should we prioritize DMRs that cover most CpG sites, span the largest genomic distance or exhibit the highest differential methylation. As there is no obvious biological criterion to optimize, there are many ad hoc methods for finding DMRs.

From the statistical point of view, however, it is clearer what we want to achieve. We know that the dataset contains redundant information in terms of spatially correlated probes. The goal is to find a smaller set of features by combining the correlated consecutive sites into regions, while preserving the underlying signal. The resulting smaller and more independent set of features can then be used for performing differential methylation analysis.

In seqlm we implement this strategy as the following three stage procedure:

The genome is divided into initial segments, according to the distances between consecutive CpG probes.

These segments are subdivided into regions, based on the differential methylation patterns.

For each region, the statistical significance of differential methylation is assessed.

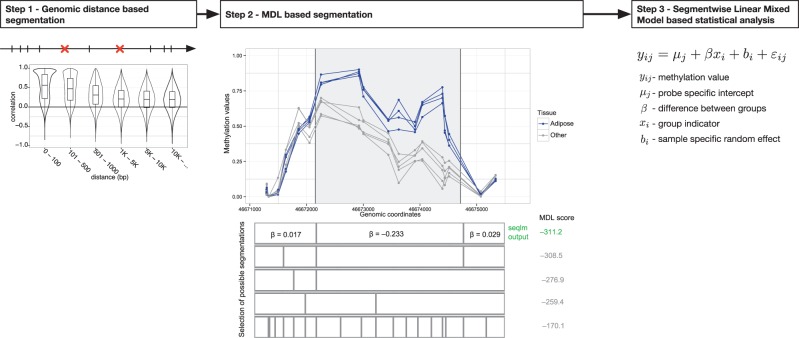

Stages 1 and 3 are relatively straightforward to carry out, while the main novelty of the method lies in step 2. Next we introduce all the stages (illustrated in Fig. 1) one by one.

Fig. 1.

Method workflow. First, the genome is segmented based on distance between consequent probes. The boxplots show the dependence between the distance and correlation of methylation patterns. Second, the resulting segments are divided further into regions with consistent methylation profiles. Finally, the differential methylation is tested using a linear mixed model (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

2.1 Initial segmentation

As the second step in our analysis is computationally rather intensive, we do the initial partitioning using simpler rules.

CpG sites on the genome cluster into tighter groups near promoters and other functional elements and the arrays concentrate also on these regions. Thus, we do not lose much information if we identify denser regions just based on genomic location. Therefore, we have chosen 1000 bp as an upper bound for the distance between two consecutive probes to belong into one region.

The exact cut-off value was determined by exploring in a large dataset (Lokk et al., 2014) the relation between methylation correlation of consecutive sites and the genomic distance (Fig. 1). As expected very close pairs of probes (less than 100 bp) are highly correlated. However, when the distance is already more than 1000 bp, the preferential correlation effect seems to be diminished.

Such initial segmentation creates many isolated sites and short regions, but also substantial amount of more populous segments in areas of sufficient coverage of the array. In the next step, these will be subdivided into regions according to their methylation patterns.

2.2 Refined methylation based segmentation

Given a continuous stretch of CpG probes, we want to divide this into regions with homogeneous methylation patterns with respect to our variable of interest, e.g. extent of differential methylation is constant within each segment.

Let yij denote the methylation value for sample i and site j and xi be the variable describing the samples. For two distinct groups, discrete values are appropriate. If the difference between our groups of interest is constant within a segment, it is well described by a linear model:

| (1) |

where μj is the baseline methylation level of site j and β is the average effect size within this segment. The same model can also handle continuous xi, then we are looking for regions where the variable of interest affects methylation in an consistent manner.

The core of the segmentation algorithm is depicted on the middle portion of Figure 1. In a given stretch of DNA we try out all the possible segmentations of CpG probes (five of those are displayed on the figure). For each segment, we fit the linear model (1), the coefficients are shown for the first segmentation.

The optimal segmentation should prefer longer regions to shorter ones, while assuring the segment-wise linear models provide a good fit. This goal can be viewed as a model selection problem and solved using the Minimum Description Length (MDL) principle.

2.2.1 Minimum description length principle

The MDL principle is a way to find an optimal trade-off between the complexity of the model and its accuracy (Rissanen, 1978). It states that from a collection of models , one should choose a model that gives the shortest description of the data. More formally, let L(M) is the description length of a model M and is the description length of data D given the model M. Then one should choose

The one-to-one correspondence between probability distributions and code lengths (Hansen and Yu, 2001), allows us to calculate as the negative log-likelihood of data D given model M. Thus, finding the optimal model is equivalent to maximizing a penalized log-likelihood function

| (2) |

where the term L(M) measures model complexity.

The MDL principle has been successfully used in various contexts in computational biology, such as for haplotype block detection (Koivisto et al., 2003) and motif discovery (Ritz et al., 2009).

2.2.2 Finding the optimal segmentation

To apply the MDL principle for segmentation, we must first extend a linear regression model (1) for one segment to the entire collection of segments. Let the shorthand denote a segment of consecutive CpG sites where si and ei represent the start and end positions of the segment. Then a segmentation is a gapless collection of non-overlapping segments .

As a result, we can characterize methylation intensities in a fixed segmentation with a piecewise linear model

| (3) |

where I is the indicator function and Mi represents the linear model (1) that is fitted to segment i.

Given a segmentation , fitting the model (3) to a region reduces to finding the least squares estimates for the linear models in each segment. Thus, it is straightforward to find the minimal penalized log-likelihood for each segmentation. See supplementary material for the exact expressions of L(M) and .

To minimize description length over the entire region, we can check all possible segmentations. As a result, we obtain a balance between the number of the segments and goodness of fit of the linear models. Less segments implies a smaller number of parameters in model (3) and thus decreases the term L(M). As the increase in the number of segments provides better fitting models and decreases , there exist a balance point.

In practice, exhaustive search for the optimum can be avoided by first fitting the linear model (1) to every possible segment and then using dynamic programming to find best segmentation. See the supplementary material for further details. The complexity of such algorithm grows quadratically with the number of probes in the original region. In case of Illumina 450K array this is not a problem, since the regions created in the first step are short enough. For larger regions, one could potentially limit the complexity growth, by introducing a restriction on the number of probes in one segment. Finally, the calculations can be trivially parallelized, making them feasible even for large datasets.

2.3 Assessing statistical significance

The previous step provides a collection of genomic regions and single sites. To identify which of these regions show condition specific methylation, we have to assess the extent of differences in methylation. As we already fitted linear models in previous step to all of the regions, we can use the same models to assess the significance of these DMRs. However, the model (1) does not take into account that nearby measurements of a same sample are highly correlated. Hence, resulting P-values are greatly inflated.

To take these correlations into account, we must add a sample specific methylation baseline to the model (1). The resulting linear mixed model

| (4) |

distinguishes sample- and condition-based effects. Interestingly, the extra term in the model (4) does not change the estimate of β compared to (1), but adjusts the respective P-values appropriately. Finally, these P-values must be adjusted for multiple testing.

In general, using the same variable xi for finding segmentation and assessing the significance of regions can inflate P-values. For example, selecting region boundaries based on strength of differential methylation or removing ‘less-promising’ regions would immediately introduce bias. However, in our approach, the second stage maximizes coherence of the regions rather than differential methylation and we do not select regions before applying model (4). As a result, the method does not introduce false positive findings (see also Table 1).

Table 1.

Detected DMRs in the simulation study with 5000 generated DMRs, with an average effect size μ

| Bumphunter |

Aclust |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP |

FP |

missed |

TP |

FP |

missed |

|||||||

| Μ | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 255 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5000 | 28697 | 1568 | 6385 | 352 | 1273 | 3464 | 18545 |

| 0.050 | 1 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 4999 | 28946 | 3241 | 15485 | 537 | 1980 | 1947 | 8903 |

| 0.075 | 5 | 174 | 0 | 0 | 4994 | 28958 | 4039 | 20952 | 581 | 2068 | 1213 | 5067 |

| 0.10 | 18 | 788 | 0 | 0 | 4978 | 28486 | 4423 | 24077 | 619 | 2158 | 810 | 3047 |

| 0.15 | 33 | 1401 | 0 | 0 | 4956 | 28079 | 4642 | 26681 | 646 | 2254 | 456 | 1656 |

| 0.20 | 63 | 2046 | 0 | 0 | 4930 | 26652 | 4715 | 26771 | 641 | 2224 | 356 | 1002 |

|

comb-p |

seqlm |

|||||||||||

|

TP |

FP |

missed |

TP |

FP |

missed |

|||||||

| Μ | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 555 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0.025 | 979 | 6005 | 61 | 506 | 3967 | 21005 | 1004 | 4792 | 65 | 330 | 3941 | 22803 |

| 0.050 | 2353 | 15518 | 40 | 295 | 2538 | 11540 | 3014 | 15713 | 172 | 862 | 1988 | 11079 |

| 0.075 | 3237 | 20921 | 29 | 181 | 1632 | 6731 | 4060 | 21450 | 201 | 1027 | 1055 | 5892 |

| 0.10 | 3686 | 23897 | 28 | 169 | 1169 | 4475 | 4626 | 24649 | 232 | 1241 | 591 | 3514 |

| 0.15 | 4140 | 26599 | 23 | 158 | 689 | 2343 | 5082 | 27137 | 257 | 1373 | 252 | 1734 |

| 0.20 | 4360 | 27005 | 27 | 185 | 467 | 1388 | 5280 | 27457 | 263 | 1354 | 112 | 917 |

For each method and for each μ, total number of the detected regions and the corresponding number of sites has been given (divided into true and false positives, ‘TP’ and ‘FP’), together with the the number of missed regions.

3 Results

We demonstrate the utility of seqlm method in three parts. First, we study the statistical properties and performance of seqlm and other methods on simulated data. Second, we apply the methods to a large public methylation dataset covering 17 different tissues. In all cases we compare seqlm with bumphunter, Aclust, Comb-p and IMA. Finally, we validate several DMRs that were identified using seqlm on Illumina 450K chip data with Sanger sequencing.

3.1 Simulation study

To study sensitivity and specificity of the DMR finding algorithms we need a dataset where we know true differential methylation patterns. For that we permuted labels on a real dataset and introduced differential methylation by changing methylation levels inside specific regions (see Section 4 for further details). This allowed us to preserve much of the structure of the original data, but at the same time introduce controlled variation into it. Without introducing any differential methylation, this schema was effective in generating data that was distributed according to the null hypothesis—the sitewise t-test P-values follow expected uniform distribution.

To test our algorithm, we run all DMR finding algorithms on the simulated data, using FDR 0.05 as a cutoff. After that we counted the number of true and false positive results. If a detected DMR overlapped with a region where we inserted differential methylation, we classified this as a true positive, otherwise as a false positive.

The results can be seen in Table 1. Each row corresponds to a different μ value which represents the average generated effect size between the two groups. The columns show the number of detected regions or number of sites within them. Together with the true and false positives we also show the number of missed regions and sites.

The first row serves as a check on the statistical validity of the algorithms, as we do not expect to find any DMRs for μ = 0. Neither bumphunter or seqlm find any DMRs in this case. Overall, the number of regions bumphunter identifies is an order of magnitude smaller compared to other methods, even with very large effect sizes.

On the other hand, Aclust identifies 87 significant regions that cover 255 sites for the first row. This indicates, that the Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) model used by Aclust, combined with the FDR correction, might be inappropriate for this type of data. Moreover, the proportion of false positive sites stays considerably higher than the expected 5% even if we introduce differential methylation. Interestingly, with Comb-p the number of false positives is not high overall, but there are several of them even if the dataset does not contain any signal. Thus, both Comb-p and Aclust can return too many false positives, especially, when the signal in the data is weak. Even if the number of true positive sites is comparable, it is still consistently lower than for seqlm.

In terms of sensitivity, the performance of seqlm is comparable to Aclust and Comb-p. For higher effect sizes, it finds consistently larger number of true positive sites, while keeping the number of false positives below 5% for most cases.

The comparison with the IMA package is more complicated, since IMA outputs overlapping results. For example, significantly differentially methylated region can partially overlap with several CpG islands, exons, promoters and other functionally relevant regions. Thus for the IMA results we calculated two sets of true and false positive values: for all and for unique results. The results for IMA are given in Supplementary Table 1.

In brief, the IMA package finds the same order of magnitude of unique sites and regions as Aclust and seqlm without exceeding 5% threshold for false positives. The main problem with IMA is that on average each site is reported as a member of two regions, but in many cases few differentially methylated sites can drive the significance of tens of regions. One could merge the overlapping significant regions as we did, but this would lose the interpretability of the results.

To summarize, seqlm displays the most sensitivity and specificity among the four alternative algorithms.

3.2 Comparisons on the 17 tissues data

As a more practical comparison, we also applied all DMR finding methods also on a real dataset that describes methylation in 17 tissues. We searched for DMRs specific to single tissues and performed sitewise t-test as a comparison. The numbers of significant regions and sites covered by those is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

For each approach, the number of significant DMRs and the corresponding number of sites has been given

| Single site |

Bumphunter |

Aclust |

Comb-p |

seqlm |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | # regions | # sites | |

| Lymph node versus others | 58 | 1 | 4 | 2543 | 6943 | 93 | 564 | 21 | 61 |

| Gall bladder versus others | 2875 | 5 | 99 | 6585 | 16054 | 722 | 3062 | 1359 | 2758 |

| Gastric mucosa versus others | 23359 | 2 | 64 | 16661 | 26494 | 2663 | 25248 | 5218 | 24717 |

| Artery versus others | 13639 | 30 | 369 | 16823 | 32626 | 2095 | 9418 | 9126 | 16775 |

| Bone, joint-cartilage versus others | 11553 | 36 | 513 | 17208 | 38107 | 2104 | 9042 | 6816 | 13232 |

| Bladder versus others | 19822 | 39 | 537 | 31413 | 68352 | 3785 | 11865 | 13529 | 22938 |

| Adipose versus others | 28379 | 32 | 407 | 34191 | 63725 | 4182 | 17910 | 15776 | 33196 |

| Ischiatic nerve versus others | 27163 | 20 | 275 | 37846 | 76119 | 4947 | 15895 | 16894 | 30337 |

| Aorta versus others | 40347 | 116 | 1081 | 40063 | 64206 | 6307 | 20809 | 27514 | 47593 |

| Tonsils versus others | 87950 | 12 | 283 | 67344 | 95188 | 6695 | 53474 | 33549 | 94807 |

| Medulla oblongata versus others | 98352 | 179 | 1887 | 97618 | 139954 | 14461 | 51007 | 62370 | 119795 |

| Bone marrow versus others | 173080 | 507 | 4217 | 153184 | 191147 | 33698 | 108590 | 100910 | 187950 |

The results are consistent with the simulation study. Bumphunter is finding a significantly smaller number of DMRs than Aclust, Comb-p or seqlm.

Compared to the single site analysis, seqlm consistently identifies 10–15% more differentially methylated sites. As the single site analysis can be considered a good baseline, we can see that the seqlm algorithm does not pick up spurious signals. Instead, it gives roughly the same set of sites grouped into fewer regions.

The behaviour of Aclust and Comb-p is less consistent. In some cases, the number of reported sites of Aclust is several times higher than for single site t-test. In other occasions, the numbers are more comparable but always higher. Given the over-sensitivity of Aclust we showed on simulated data, such differences are rather suspicious and are likely to contain more than 5% false positives. Comb-p, in turn, seems to find many regions in comparisons where other methods do not find much and less in other comparisons with stronger signals.

When considering length of the identified regions we can also see slight differences. Supplementary Figure S1 details the length distribution of all regions with at least 2 sites in Table 2. Bumphunter tends to identify the longest regions and does not return almost any regions with less than 3 sites, as the length of the region is also an important criterion in region selection. In other cases the distribution was more skewed towards short regions with Aclust giving the shortest and seqlm and combp giving slightly longer correspondingly.

In summary, seqlm seems to give a consistent improvement over single site analysis without returning a suspiciously high amount of differentially methylated sites.

3.3 Validation of identified DMRs

While the 450K sites on Illumina methylation arrays represent a marked improvement over previous technologies, they still represent only 1.5% of the 29M CpG sites on the genome. Thus, it is not a priori clear that DMR-s inferred from such low-resolution measurements reflect biological reality and are not technical artifacts. To address this concern, we have validated 14 of the DMR-s identified in Table 2 using Sanger sequencing.

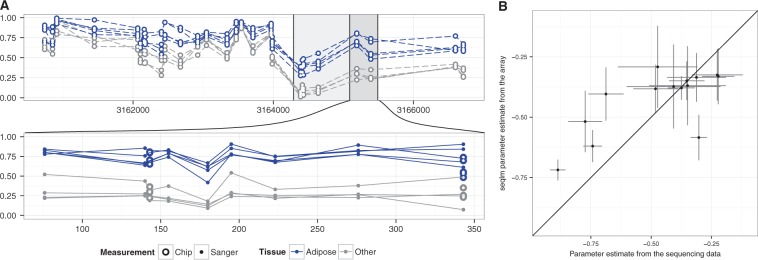

Figure 2A shows an example of such a validation. We can see that there is good overlap between the results of two approaches at the sites that are measured by both. More importantly, the differential methylation pattern identified on the array level can also be observed at the intermediate sites.

Fig. 2.

Validation of identified DMR-s. Panel A has an example from the tissue dataset together with a DMR detected by seqlm (large grey box). The top plot shows the data on array resolution and in bottom plot a portion of the DMR has been zoomed in, and methylation levels of intermediate CpG sites obtained by Sanger sequencing are shown. Panel B shows the effect sizes that are estimated from array data and from Sanger sequencing data for all 14 regions. The 95% confidence intervals are shown for both sources of estimates (Color version of this figure is available at Bioinformatics online.)

Figure 2B summarizes the results for all 14 regions by showing the estimated effect sizes from both array and Sanger sequencing data. We can see that differential methylation of all the regions is confirmed on the higher resolution. Moreover, the effect sizes from array and Sanger measurements are well correlated. In 6 cases out of 14 the effect size, seen independently from Sanger measurements, is within the confidence intervals of the array based estimate.

All together the data shows that DMRs identified on array data adequately represent the underlying methylation patterns on single site resolution.

3.4 Implementation and performance

Our method has been implemented in an R package seqlm, freely available through Github: https://github.com/raivokolde/seqlm. The method is not specific to the Illumina 450k methylation array and can be used with many other arrays. For example the code can be easily used for analyzing tiling array data.

The performance of seqlm is sufficient to analyze any array based dataset on ordinary laptop computers. Moreover, as the implementation supports multi-core computations, it is possible to speed up the analysis on dedicated computation servers.

To compare running time with competitors, we ran seqlm together with bumphunter and Aclust on our simulated dataset. Surprisingly, seqlm was the fastest of the three (Supplementary Table S2). Using multiple cores it is possible to improve the performance of seqlm and bumphunter, but not Aclust.

4 Methods

4.1 Datasets

For demonstrative purposes, we have used a large publicly available methylation dataset on Illumina 450k platform (GSE50192). There, the methylation of 17 tissues from four autopsied humans has been measured.

4.2 Data simulation

To simulate data while retaining most of the characteristics of a real methylation dataset, we have permuted a subset of the 17 tissues data. To obtain data with relatively homogeneous patterns, we chose the subset consisting of a total of 16 samples: coronary artery, splenic artery, thoracic aorta and abdominal aorta. We selected a set of similar tissues to avoid encountering a rather strong signal in the permuted data by chance.

To start we split the genome into smaller pieces that have properties as follows. First, the genomic distances between consecutive sites remain below 1000 bp within each piece. Second, the correlation between all consecutive sites within each piece is above a threshold of 0.1. The aim of these choices was to extract those locations from the data where the methylation patterns are reasonably similar. As a result, we obtain 250 000 pieces with length greater than one, with average length 3.8 sites.

For each piece, we assign the group labels randomly such that we would have eight samples in one group and eight in another. As a result, we get the data where on average there is no group effect, the single site P-values are following closely the uniform distribution.

Finally, we choose randomly N = 5000 pieces with length greater than 1 (with probability proportional to length) and change them into DMRs, by increasing the values in one group by . We varied μ in .

4.3 Parameters for tested methods

While comparing seqlm to other methods which require several input parameters, we either used the default values or the ones recommended in the original publication.

For all methods except for bumphunter, we defined significant differential methylation with FDR corrected P-values below the threshold 0.05. As bumphunter does not divide the genome into regions and rather searches for DMRs, one cannot use FDR correction, so instead we used its reported familywise error rate with threshold 0.10, which was also used in Jaffe et al. (2012).

For bumphunter the parameters used were: pickCutoffQ = 0.99, maxGap = 1000 and smooth = TRUE (as suggested by Jaffe et al., 2012).

For Aclust,we used the ’best’ configuration of the parameters reported in Sofer et al. (2013), i.e. Spearman correlation, average distance clustering, distance cutoff 0.2, and 999-base-pair-merge.

For comb-p, we used P-value threshold of 0.05 for candidate regions.

4.4 Sanger sequencing

For validation we selected 14 DMR-s that were tissue specific, showed large effect size and where it was possible to design primers. Primers for PCR amplification of the bisulfite-treated DNA were designed using MethPrimer (Li and Dahiya, 2002) and are listed in Additional file 9. The 20 L reaction mixes contained 80 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.4–9.5), 20 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.02% Tween-20 PCR buffer, 3 mM MgCl2, 1× Betaine, 0.25 mM dNTP mix, 2 U Smart-Taq Hot DNA polymerase (Naxo, Tartu, Estonia), 50 pmol forward primer, 50 pmol reverse primer and 20 ng bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. The PCR cycling conditions were: 15 min at 95 °C for enzyme activation, followed by 17 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 62 °C and 120 s at 72 °C, with a final -0.5 °C /cycle step-down gradient over 21 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 52 °C and 120 s at 72 °C. The sequencing results were analyzed with Mutation Surveyor software (Softgenetics, State College, PA, USA).

5 Discussion

The method as defined in this article opens up a number of future directions for development. The current model can also handle continuous variables in addition to the two groups of data. Thus, it is possible to use seqlm to search for methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs). In such analysis, even small improvements in statistical power can have huge consequences.

The method can be generalized to handle raw sequencing data with methylation counts instead of aggregated methylation values. For that we must replace linear regression with logistic regression. The change only alters the model fitting inside fixed region and not the core of the dynamic programming routine.

The MDL framework underlying seqlm is a powerful way to identify genomic regions. By employing different statistical models it is possible to specify the properties of the desired regions. For example one can include more sophisticated linear models to test more complex hypotheses or use clustering methods instead, to perform unsupervised region finding.

6 Conclusion

We presented a novel approach for DMR identification, described as a three-stage process. First, the data is divided into smaller segments based on genomic distance between consecutive probes. Then, each of these segments is divided into regions with consistent differential methylation patterns. For this, all possible segmentations are considered and the optimal one is chosen according to the MDL principle. Finally, the significance of differential methylation in each region is assessed using linear mixed models. In our algorithm, the latter two steps are naturally related as both the segmentation and assessing the statistical significance are based on the β parameter.

We showed that seqlm performs well on simulated data, being both more sensitive and more specific than the alternative methods. On a real dataset we can see that DMRs found by seqlm cover more sites than other methods while controlling the Type I error rate. At the same time, the redundancy within the results is smaller as the close sites are reported together. Finally, we validated 14 DMRs using Sanger sequencing and managed to show good correlation between the array and sequencing based estimates of differential methylation.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The research is funded by Estonian Research Council [IUT34-4] and European Regional Development Fund through the EXCS and BioMedIT projects.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

References

- Aryee M.J. et al. (2014) Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics, 30, 1363–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylin S.B., Jones P.A. (2011) A decade of exploring the cancer epigenomebiological and translational implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 11, 726–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J.T. et al. (2012) Epigenome-wide scans identify differentially methylated regions for age and age-related phenotypes in a healthy ageing population. PLoS Genet., 8, e1002629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt F. et al. (2006) Dna methylation profiling of human chromosomes 6, 20 and 22. Nat. Genet., 38, 1378–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M.H., Yu B. (2001) Model selection and the principle of minimum description length. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 96, 746–774. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A.E. et al. (2012) Bump hunting to identify differentially methylated regions in epigenetic epidemiology studies. Int. J. Epidemiol., 41, 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kechris K.J. et al. (2010) Generalizing moving averages for tiling arrays using combined p-value statistics. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol., 9, Article29.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto M. et al. (2003) An MDL method for finding haplotype blocks and for estimating the strength of haplotype block boundaries. Pac. Symp. Biocomput., 502–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.C., Dahiya R. (2002) Methprimer: designing primers for methylation pcrs. Bioinformatics, 18, 1427–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lienert F. et al. (2011) Identification of genetic elements that autonomously determine DNA methylation states. Nat. Genet., 43, 1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokk K. et al. (2014) DNA methylome profiling of human tissues identifies global and tissue-specific methylation patterns. Genome Biol., 15, r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marabita F. et al. (2013) An evaluation of analysis pipelines for DNA methylation profiling using the illumina humanmethylation450 beadchip platform. Epigenetics, 8, 333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill J. et al. (2008) Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 82, 696–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen B.S. et al. (2012) Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping and correcting spatially correlated P/i-values. Bioinformatics, 28, 2986–2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen J. (1978) Modeling by shortest data description. Automatica, 14, 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ritz A. et al. (2009) Discovery of phosphorylation motif mixtures in phosphoproteomics data. Bioinformatics, 25, 14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slieker R.C. et al. (2013) Identification and systematic annotation of tissue-specific differentially methylated regions using the illumina 450k array. Epigenet. Chromatin, 6, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofer T. et al. (2013) A-clustering: a novel method for the detection of co-regulated methylation regions, and regions associated with exposure. Bioinformatics, 29, 2884–2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toperoff G. et al. (2012) Genome-wide survey reveals predisposing diabetes type 2-related DNA methylation variations in human peripheral blood. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. et al. (2012) IMA: an r package for high-throughput analysis of illumina’s 450k infinium methylation data. Bioinformatics, 28, 729–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely F., Emes R.D. (2012) Identification of DNA methylation biomarkers from infinium arrays. Front. Genet., 3, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.