ABSTRACT

Recently, we have reported that adipose tissue-derived stem cells (ASC) harvested from obese donors induce a pro-inflammatory environment when co-cultured with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (MNC), with a polarization of T cells toward the Th17 cell lineage, increased secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 pro-inflammatory cytokines, and down-regulation of Th1 cytokines, such as IFNγ and TNFα. However, whether differentiated adipocytes, like the aforementioned ASC, are pro-inflammatory in obese subject AT remained to be investigated. Herein, we isolated ASC from AT of obese donors and differentiated them into adipocytes, for either 8 or 14 d. We analyzed their capacity to activate blood MNC after stimulation with phytohemagglutinin A (PHA), or not, in co-culture assays. Our results showed that co-cultures of MNC with adipocytes, like with ASC, increased IL-17A, IL-1β, and IL-6 pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. Moreover, like ASC, adipocytes down-regulated TNFα secretion by Th1 cells. As adipocytes differentiated from ASC of lean donors also promoted IL-17A secretion by MNC, an experimental model of high-fat versus chow diet mice was used and supported that adipocytes from obese, but not lean AT, are able to mediate IL-17A secretion by PHA-activated MNCs. In conclusion, our results suggest that, as ASC, adipocytes in obese AT might contribute to the establishment of a low-grade chronic inflammation state.

KEYWORDS: adipose-tissue derived stem cells, ASC, blood mononuclear cells, IL-17A, subcutaneous adipose tissue, Th17

Introduction

Increased incidence of obesity and its subsequent complications are a worldwide public health problem. During the development of obesity, visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue (AT) depots are subjected to extensive tissue remodeling and hypertrophy,1 with expansion of the abdominal AT compartments being a strong predictor of the development of insulin resistance.2 AT inflammation is considered as the causal event leading to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and its associated cardiovascular and metabolic complications.3 In the obese condition, hypertrophied AT becomes heavily infiltrated by a variety of immune cells.4 Macrophage infiltration within AT mainly occurs at an advanced stage of obesity, and is a major driver of inflammation.5,6 In contrast, T cells appear to play a role in the regulation of obesity-induced inflammation,7 since lean AT is infiltrated by anti-inflammatory CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) and Th2 cells, which both secrete IL-10, a cytokine known to improve adipocyte insulin sensitivity.8 In contrast, CD8+ T cell accumulation in AT from obese subjects has been shown to precede macrophage infiltration, and to contribute to macrophage recruitment and AT inflammation.9 Besides their function as fat repositories, adipocytes can also be considered as endocrine cells that secrete numerous adipokines involved in the regulation of metabolic homeostasis, with IL-6 and leptin being pro-inflammatory while adiponectin is anti-inflammatory.10 Therefore, a crosstalk between adipocytes and the immune cell populations infiltrating AT may govern homeostasis under physiological conditions, but contribute to the establishment of a chronic sub-clinical inflammation, a prerequisite for insulin resistance, during obesity.

A recently discovered T-cell lineage playing a central role in obese AT inflammation corresponds to the T-helper 17 (Th17) cell subset,11 which mainly secretes IL-17A and IL-17F pro-inflammatory cytokines.12 IL-17A/F play a crucial role against extracellular bacterial or fungi infections but are also able to induce secretion of other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, chemokines (e.g. CXCL8) by a variety of immune and non-immune cells, including monocytes, stromal cells, adipocytes and stem cells, which all express IL-17A/F receptors.13 While Th17 cells and IL-17A/F have been implicated in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases, such as psoriasis, multiple sclerosis and/or rheumatoid arthritis14; their role in obesity and type 2 diabetes is still being elucidated. IL-17A concentrations in obese subjects were demonstrated to be increased not only in plasma,15 but also within the AT of obese subjects, and more particularly among mucosal-associated invariant T cells.16-18 IL-17A has also been suggested to favor the development of insulin resistance, through downregulation of multiple pro-adipogenic transcription factor expression, such as PPARγ, C/EBPα, and/or dysregulation of several members of the Krüppel-like family transcription factors, leading to inhibition of adipogenesis.19 In spite of these advances, the mechanisms by which Th17 cells are increased in AT of obese subjects remain unknown. Recently, we have reported that adipose stem cells (ASC) from obese, but not lean donors, contribute to Th-17 promotion through contact-dependent interactions and soluble factor secretion.20 ASC-mediated lL-17A secretion was associated with increased secretion of IL-1β by monocytes and IL-6 by ASC, but decreased TNFα and IFNγ secretion by Th1 cells. Interestingly, increased IL-17A secretion was also found in the stromal vascular fractions (SVF) of obese, but not lean subjects. However, the implication of adipocytes into Th17 cell subset activation was not addressed in our previous study. With this aim, we investigated herein whether, once differentiated into adipocytes, ASC would maintain their pro-inflammatory properties. To answer this question, we harvested ASC from subcutaneous AT depots of obese subjects and differentiated them for 2 independent time points: 8 d to obtain differentiating adipocytes, and 14 d to obtain more mature adipocytes. Differentiated adipocytes were co-cultured with blood MNC, and induction of a pro-inflammatory environment was determined through quantification of multiple secreted cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα. Our results showed that both day 8 and day 14 ASC-derived adipocytes were able to induce IL-17 A secretion by PHA-activated MNC, which was confirmed in a physiological model, where IL-17A secretion was induced by adipocytes harvested from obese, but not lean mice. Our results suggested thus that like ASC, adipocytes might contribute to the establishment of a low-grade chronic inflammation state in AT of obese subjects.

Results

Both ASC and ASC-derived adipocytes from obese subject AT polarize T cells toward the Th 17 cell subset while inhibiting Th1 cells

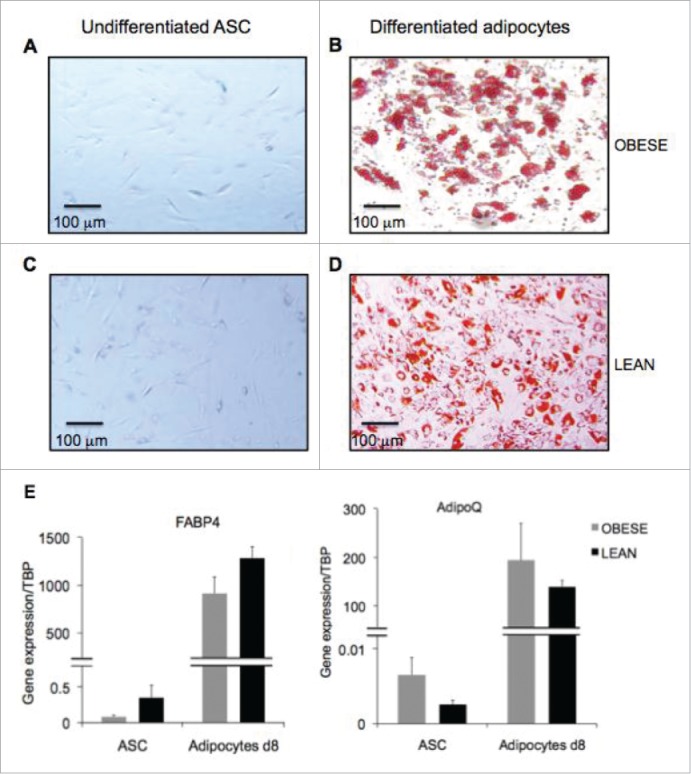

To analyze the role of differentiated adipocytes in the activation of infiltrating blood mononuclear cells (MNC), we first differentiated ASC isolated from subcutaneous adipose depots of obese and lean subjects into adipocytes for 8 d. Differentiation was morphologically assessed by Oil Red O staining of lipid droplets, which were clearly visible in adipocytes (Fig. 1B and D), but absent in undifferentiated ASC (Fig. 1A and C). The occurrence of adipocyte differentiation was also monitored by evaluation of gene expression of the adipogenic genes FABP4 and AdipoQ/adiponectin, which were both highly upregulated, as soon as day 8 of differentiation (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Generation of differentiated adipocytes from ASC derived from subcutaneous AT of obese donors. Oil Red O staining of undifferentiated ASC (A,C) and differentiated adipocytes (B,D) respectively at day 8 and 14 of differentiation. Scale bars represent 100 µm. (E) Gene expression quantification of adipogenic genes FABP4 (left graph) and AdipoQ (right graph) in ASC and ASC-derived adipocytes at 8d of differentiation derived from obese (gray bars) and lean (black bars) donors. Error bars represent standard deviations from n ≥ 3 independent experiments.

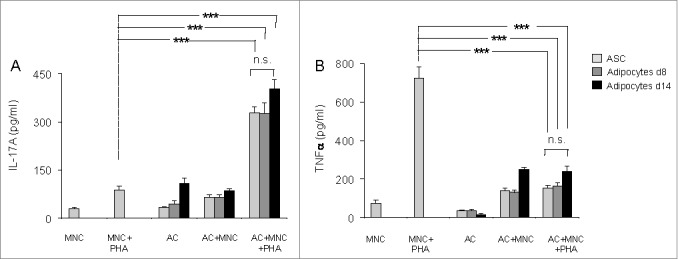

Next, to investigate whether differentiated adipocytes were able to promote inflammation, we co-cultured them with MNC activated in the presence or absence of PHA for 48 hours, and measured cytokine secretion by ELISA. As shown in Figure 2A, IL-17A secretion by PHA-activated MNC was upregulated at comparable levels, and without any statistically significant differences, in the presence of undifferentiated ASCs, or adipocytes differentiated for either 8- or 14-days. In contrast, PHA-mediated TNFα secretion, a marker of Th1 cell activation, was significantly inhibited in the presence of either adipocytes, or ASC (Fig. 2B). Thus, our results demonstrate that adipocytes, like ASC, may contribute to the regulation of T cell activation, through polarization toward the Th17 cell lineage but inhibition of the Th1 cell population.

Figure 2.

Both undifferentiated ASC and ASC-derived adipocytes (adipose cells, AC) polarize T cells toward the Th17 lineage and down-regulate Th1 cytokines. ASC differentiation was carried out for 8 d or 14 d as indicated. Cell culture supernatants of MNC co-cultured or not with undifferentiated ASC (light gray bars), differentiated adipocytes at day 8 (gray bars) or at day 14 (black bars), and activated by PHA or not, were analyzed by ELISA for the secretion of IL-17A (A) and TNFα (B). Co-cultures were in a 1:5 ratio (20,000 ASC/adipocytes for 100,000 MNC). Error bars represent standard deviations from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 as tested by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. n.s not statistically significant for each combinatorial comparisons within the 3 bars.

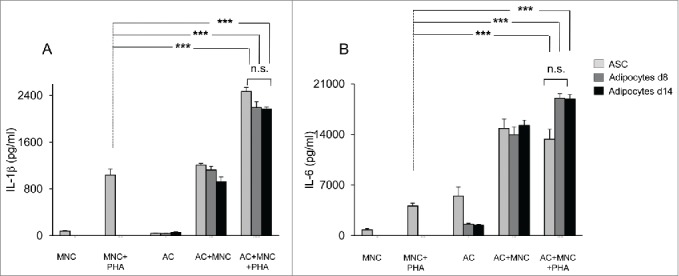

Both ASC and ASC-derived adipocytes from obese donors amplify IL-1β and IL-6 secretion

A substantial fraction of MNC is constituted by monocytes. As shown in Figure 3A, monocytes were also activated by co-culture with ASC or adipocytes derived thereof, as assessed by the higher levels of IL-1β that were observed when either ASC, or adipocytes differentiated for 8- or 14-days were added to PHA-activated MNC cultures. Here again, IL-1β secretion levels were comparable to those induced by ASC. Interestingly, the levels of IL-1β secretion increased in the absence of PHA, but at a lesser extent than with PHA, probably as a result of innate immunity. Finally, IL-6 secretion was also up-regulated in these co-culture assays containing differentiated adipocytes (Fig. 3B). Taken together, our data suggest that interaction of MNC with ASC, and/or adipocytes derived thereof may contribute to the inflammatory environment which is observed in AT from obese subjects.

Figure 3.

Both undifferentiated ASC and ASC-derived adipocytes (adipose cells, AC) enhance IL-1β secretion by monocytes and IL-6 secretion by ASC or adipocytes. Cell culture supernatants of MNC co-cultured or not with undifferentiated ASC (light gray bars), differentiated adipocytes at day 8, and activated by PHA or not, were analyzed by ELISA for the secretion of IL-1β (A) and IL-6 (B). Error bars represent standard deviations from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.01 as tested by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. n.s not statistically significant for each combinatorial comparison within the 3 bars.

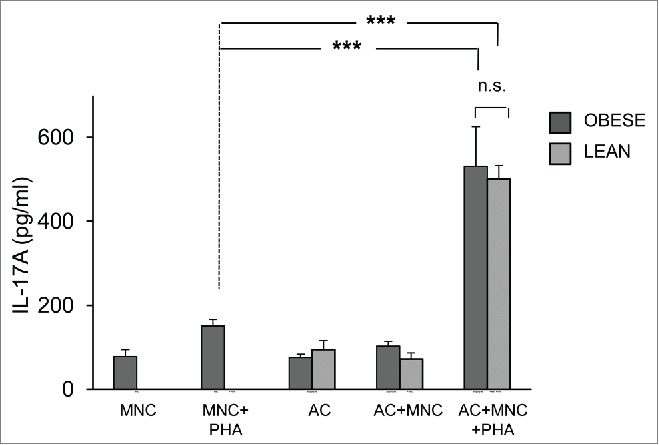

ASC-derived adipocytes from lean AT can also mediate IL-17A secretion by PHA-activated MNC

As control, adipocytes were differentiated for 8 d from ASC of lean donors. Then, lean MNC were activated with PHA or not, in the presence of adipocytes of different origins. The differentiation capacities of obese vs. lean adipocytes were comparable as assessed morphologically and by quantification of adipocyte-specific genes FABP4 and AdipoQ (Fig. 1). Moreover, induction of IL-17A secretion by MNC was comparable as well (Fig. 4). These results suggested either i) that adipocytes were pro-inflammatory, whatever their origin, or ii) that in vitro differentiation could have modified the behavior of ASC-derived adipocytes.

Figure 4.

ASC-derived adipocytes from lean donors induce IL-17A secretion in MNC-adipocytes co-cultures. ASC from obese (dark gray bars) or lean (light gray bars) donors were differentiated for 8 d. Cell culture supernatants of MNC co-cultured or not with differentiated adipocytes were activated by PHA or not, and analyzed by ELISA for the secretion of IL-17A. Co-cultures were in a 1:5 ratio (20,000 ASC/adipocytes for 100,000 MNC). Error bars represent standard deviations from n ≥ 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001; as tested by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. n.s not statistically significant.

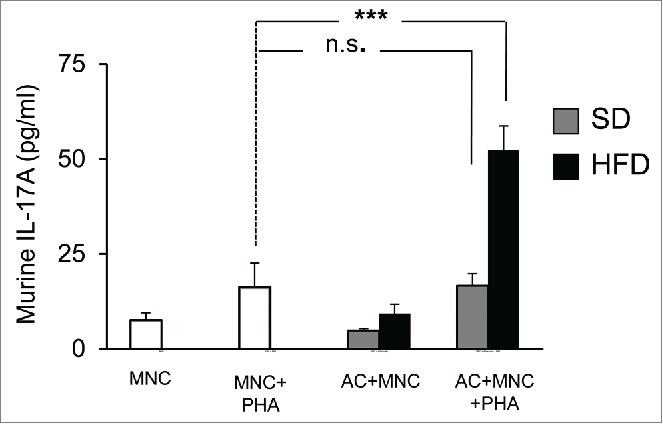

Adipocytes harvested from adipose tissue of obese, but not lean animals, are able to mediate IL-17A secretion, in a murine model

To analyze whether adipocytes may activate IL-17A secretion physiologically, we used an animal model in which mice were rendered obese or not, with high fat or chow diets, respectively. We then cultured the adipocyte fraction of adipose tissues harvested either from obese versus lean mice with spleen mononuclear cells from lean mice and activated them with PHA or not. Results showed that adipocytes from obese, but not lean mice were able to promote IL-17A secretion by MNC after 48 hour co-culture (Fig. 5). Therefore, these results suggest that obese but not lean adipocytes may contribute to AT inflammation.

Figure 5.

Murine adipocytes from obese, but not lean mice, induce IL-17A secretion in MNC-adipocytes co-cultures. Adipocytes from subcutaneous adipose tissue of mice fed a standard diet (SD, gray bars) or a high-fat diet (HFD, black bars) were co-incubated with spleen-derived MNC and stimulated or not with PHA. Cell culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for the secretion of murine IL-17A. Error bars represent standard deviations from n ≥ 5 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001; as tested by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test. n.s not statistically significant.

Discussion

White adipose tissue is a site of chronic inflammation in obesity, due to secretion of inflammatory cytokines and adipokines by infiltrating immune cells and adipocytes.21 The major consequence of obesity-associated chronic inflammation is the development of insulin resistance, and type 2-diabetes, together with impairment of AT homeostasis.6 AT is mainly composed of adipocytes, which stock fatty acids and release energy. In addition, the dynamic extracellular matrix of the adipose tissue plays an important role in the regulation of AT expansion and vascularisation, with adipose tissue from obese subjects displaying fewer capillaries and more large vessels, as compared to lean subjects.22 Inside the AT, the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) - an heterogeneous cell population mainly composed of ASC and immune cells23 - is also a key actor during the transition from lean to obese AT, as obesity substantially modifies SVF composition and function. In a previous study, we have shown that SVF derived from obese, but not lean donors, were able to promote Th17 cells following activation with a mitogen, such as PHA. In addition, we have demonstrated the critical role of ASC in inducing polarization of T cells toward Th17 pro-inflammatory cells, and activation of IL-1β secretion by monocytes.20 This was associated with up-regulation of IL-6 secretion by ASC, which might be mediated, at least in part by IL-17A. Indeed, ASC are known to express receptors for IL-17A/F13, which themselves have been shown to activate IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 secretion by mesenchymal stem cells, following ligation with IL-17A/F24. Because IL-6 in turn is known to participate to IL-17A signaling pathway through Stat3 phosphorylation,25 our previous study strongly suggests that ASC may mediate a vicious circle of pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion contributing to the chronic low grade inflammation known to occur in AT of obese subjects.

However, one could argue that the paucity of ASC in AT- even though ASC are known to proliferate during obesity26 cannot account for such a degree and/or persistence of inflammation. Therefore, to answer this question, we investigated in the present study whether ASC would maintain their pro-inflammatory status, once differentiated into adipocytes. With this aim, ASC, or adipocytes harvested at two different steps of differentiation (8 and 14 days), were co-cultured with PHA-activated MNC for 48 hours. The patterns of cytokine secretion induced by adipocytes were quite similar to that of their progenitors, with increased secretion of IL-17A, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Figs. 2 and 3). Interestingly, like ASC, adipocytes were also able to negatively regulate Th1 cells, as assessed by decreased secretion of TNFα (Figure 2B). This is reminiscent with a previous study, in which we have demonstrated that, like their progenitors, i.e: mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblast-like synoviocytes promote Th17 cells, but inhibit Th1 cells.24 Thus, our results suggested that both ASC and adipocytes derived-off may initiate inflammation in AT of obese subjects. To validate these results, ASC from lean AT were differentiated into adipocytes for 8 days, but unexpectedly demonstrated pro-inflammatory properties as well (Fig. 4). Thus, this either could signify that adipocytes are pro-inflammatory whatever subject weight, or that in vitro differentiation of ASC was able to modify adipocyte behavior and activate them toward a pro-inflammatory state. Therefore, to approximate physiological conditions, we used an experimental model in which mice were rendered obese or not, with high fat or chow diets, respectively. We then cultured the adipocyte fraction of adipose tissues harvested either from obese or lean mice with spleen mononuclear cells from lean mice. This led us to demonstrate that adipocytes from obese, but not lean mice, were able to promote IL-17A secretion by MNC after 48 hour activation. Therefore, these results strongly suggested that obese but not lean adipocytes might exert pro-inflammatory functions. The relative contribution of ASC or adipocytes in inducing MNC activation remains now to be determined, with adipocytes possibly playing a quantitatively more important as compared to ASC, due to their numerical preponderance. However, at the qualitative level, ASC might play a key role due to their ability to proliferate and differentiate into adipocytes in obese AT. Accordingly, a recent study has demonstrated that delivery of ASC from lean mice, into white AT of obese mice, attenuated WAT inflammation, and insulin sensitivity.27 Taken together, our present data demonstrate that interaction of MNC with ASC, and/or adipocytes may contribute to the inflammatory environment, which is observed in obese AT. Because we have demonstrated that cell to cell contact between ASC and mononuclear cells is critical for inducing inflammation,20 the identification of the cell-surface molecules involved in these interactions should allow the design of novel targets in the treatment of obesity, and/or insulin resistance. Whether ASC and adipocytes interact with infiltrating immune cells through the same cell-surface molecules require further investigation.

Materials and methods

Isolation and expansion of adipose stem cells (ASC)

Subcutaneous AT was isolated from residues of bariatric surgery, with the approval of the Person Protection Committee of the “Hospices Civils de Lyon,” or from patients undergoing surgery, with their informed consent. AT (50–100 mg) was fragmented and incubated in 2g/L of collagenase type Ia solution (Sigma Aldrich, C2674) dissolved in DMEM:F12 medium (50/50 vol/vol) (Invitrogen) for 40 min at 37°C by mixing. Collagenase action was quenched by addition of 10 ml DMEM:F-12 medium, 1:1 vol/vol supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). The released stromal vascular fraction (SVF) was recovered by centrifugation (800 g for 7 min at 25°C), residual red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic shock and the ASC component of the SVF was selectively expanded in culture medium composed of DMEM:F-12 supplemented with 10% FCS, 4 ng/mL Fibroblast Growth Factor basic (e-Biosciences, 14-8986-80), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Half of the culture medium was changed every 2 or 3 d. ASC were amplified by several passages in culture (4 to 5) and directly used for experiments or stored in liquid nitrogen.

Isolation of blood mononuclear cells (MNC)

Blood samples were obtained through the blood bank center of Lyon (France), following institutionally approved guidelines. MNC were extracted from healthy human peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque, Miltenyl Biotec). MNC were stored in liquid nitrogen prior to use.

Differentiation of obese subcutaneous ASC into adipocytes

ASC from subcutaneous AT of obese donors were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in a 12-well plate (3.8 cm2/well) containing basal culture medium (DMEM:F-12 medium, 1:1 vol/vol supplemented with 10% FCS) for 2 d. Cells were stimulated to differentiate using an adipogenic culture medium composed of basal culture medium supplemented with 1.8 µM insulin, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxantine (IBMX), 500 nM dexamethasone, 1 μM rosiglitazone, 2 nM triiodothyronine and 10 μg/ml transferrin (all from Sigma-Aldrich). During differentiation, the culture medium was replaced every 2 to 3 d. Differentiated adipocytes were obtained after 8–14 d. Differentiation was validated by light microscopy, Oil Red O visualization of lipid droplets.

Gene expression measurements

Total RNA were extracted from adipocytes at day 8 of differentiation and control ASC cultivated 8 d in basal culture medium using Tri Isolation Reagent™ (Roche, Meylan, France). RNAs were stored at −80°C until analysis. cDNA was synthesized from 250 ng of total RNA using the Primescript™ RT reverse transcription kit (Takara, Dalian, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed in duplicate on a Rotor-gene Real-time PCR System, using the AbsoluteTM QPCR SYBR Green Mix (ABgene, Illkirch, France). Quantitative data were defined by threshold cycle (Ct) normalized for the housekeeping gene TATA Box Binding Protein (TBP). FABP4 and Adiponectin (AdipoQ) were used as adipogenic markers.

Oil Red O staining

Oil Red O staining, an indicator of intracellular lipid accumulation, was used to assess adipocyte differentiation. At day 8, adipogenic culture medium was removed; cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed using 10% formaldehyde (in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature. The fixative was removed and replaced with 60 % isopropanol to totally dry cells. ASC or adipocytes were stained for 10 minutes at room temperature with a 0.2 % Oil Red O solution (Oil Red O powder, Sigma O-0625). Cells were then washed 3 to 4 times with PBS to remove excess stain. Photos were taken using ZEN Microscope version 2012 (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH).

Co-culture assays

Adipocytes (differentiated for 8 or 14 days) or undifferentiated ASC were harvested and seeded in 96-well plates (20,000 cells/well) for 18–24 h in 200 μl of basal culture medium (DMEM:F-12 medium, 1:1 vol/vol supplemented with 10% FCS). 100,000 MNC were co-seeded for 48h in the presence or absence of phytohemagglutinin (PHA, 5 µg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich). Ratios 1:5 were used for ASC:MNC co-cultures. Cells were incubated in 200 μL of RPMI supplemented with 10 % FCS. Supernatant was harvested and frozen.

Adipose-tissue derived adipocytes and co-cultures

Four weeks old male C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice were purchased from Harlan. Mice were housed at 22°C with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines for the care of laboratory animals and were approved by the local ethic committee. After 1 week of acclimatization, 5–6 week old C57BL/6JOlaHsd mice were divided into 2 groups: one group with free access to a standard chow diet (SD; A04, Safe, France), the other with free access to the standard diet supplemented with 20% of palm oil (w/w) (HFD, Safe, France) for 16 weeks. Adipocytes were harvested from the same weight of subcutaneous pads. After digestion with collagenase, adipocytes were separated by centrifugation (to exclude the stromal vascular fraction), and co-cultured with MNC from spleen of lean mice in a final volume of 2 ml of RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS, with or without PHA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

Human IL-17A (#88-7176-88), IL-1β (#88-7261-88), IL-6 (#88-7066-88) and TNFα (#88-7346-88) and murine IL-17A (#88-7371-22) secretion were evaluated by ELISA using the corresponding antibodies (all from e-Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Comparisons between multiple groups were performed by ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Bonferroni's multiple Comparison test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Abbreviations

- ASC

adipose-tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells

- AT

adipose tissue

- AC

adipose cells

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

- IL-17A

interleukin-17A

- MNC

mononuclear cells

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. A. Mey for providing part of the ASC used in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the INSERM institute, Hospices Civils de Lyon and research grants from “Fondation de l'Avenir” and “Fondation Chèque Dejéuner” to Assia. Eljaafari. MC was supported by a PhD scholarship from the Rhone-Alpes region.

References

- 1.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006; 444:860-7; PMID:17167474; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Despres JP, Lemieux I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2006; 444:881-7; PMID:17167477; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donath MY, Shoelson SE. Type 2 diabetes as an inflammatory disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:98-107; PMID:21233852; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri2925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med 2012; 18:363-74; PMID:22395709; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1796-808; PMID:14679176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI200319246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, et al.. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2003; 112:1821-30; PMID:14679177; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI200319451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumeng CN, Maillard I, Saltiel AR. T-ing up inflammation in fat. Nat Med 2009; 15:846-7; PMID:19661987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm0809-846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, Lee J, Goldfine AB, Benoist C, Shoelson S, et al.. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med 2009; 15:930-9; PMID:19633656; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Eto K, Yamashita H, Ohsugi M, Otsu M, Hara K, Ueki K, Sugiura S, et al.. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med 2009; 15:914-20; PMID:19633658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Walsh K. Obesity, adiponectin and vascular inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 2003; 14:561-6; PMID:14624132; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00041433-200312000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fouser LA, Wright JF, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M. Th17 cytokines and their emerging roles in inflammation and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev 2008; 226:87-102; PMID:19161418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed M, Gaffen SL. IL-17 in obesity and adipogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2010; 21:449-53; PMID:21084215; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaffen SL. Recent advances in the IL-17 cytokine family. Curr Opin Immunol 2011; 23:613-9; PMID:21852080; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 2008; 28:454-67; PMID:18400188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumarac-Dumanovic M, Stevanovic D, Ljubic A, Jorga J, Simic M, Stamenkovic-Pejkovic D, Starcevic V, Trajkovic V, Micic D. Increased activity of interleukin-23/interleukin-17 proinflammatory axis in obese women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009; 33:151-6; PMID:18982006; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ijo.2008.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magalhaes I, Pingris K, Poitou C, Bessoles S, Venteclef N, Kiaf B, Beaudoin L, Da Silva J, Allatif O, Rossjohn J, et al.. Mucosal-associated invariant T cell alterations in obese and type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:1752-62; PMID:25751065; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI78941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalmas E, Venteclef N, Caer C, Poitou C, Cremer I, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Bayry J, Kaveri SV, Clément K, et al.. T cell-derived IL-22 Alifies IL-1beta-driven inflammation in human adipose tissue: relevance to obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2014; 63:1966-77; PMID:24520123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db13-1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabbrini E, Cella M, McCartney SA, Fuchs A, Abumrad NA, Pietka TA, Chen Z, Finck BN, Han DH, Magkos F, et al.. Association between specific adipose tissue CD4+ T-cell populations and insulin resistance in obese individuals. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:366-74 e1-3; PMID:23597726; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed M, Gaffen SL. IL-17 inhibits adipogenesis in part via C/EBPalpha, PPARgamma and Kruppel-like factors. Cytokine 2013; 61:898-905; PMID:23332504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eljaafari A, Robert M, Chehimi M, Chanon S, Durand C, Vial G, Bendridi N, Madec AM, Disse E, Laville M, et al.. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells from obese subjects contribute to inflammation and reduced insulin response in adipocytes through differential regulation of the Th1/Th17 balance and monocyte activation. Diabetes 2015, 64:2477-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talukdar S, Oh da Y, Bandyopadhyay G, Li D, Xu J, McNelis J, Lu M, Li P, Yan Q, Zhu Y, et al.. Neutrophils mediate insulin resistance in mice fed a high-fat diet through secreted elastase. Nat Med 2012; 18:1407-12; PMID:22863787; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spencer M, Unal R, Zhu B, Rasouli N, McGehee RE Jr., Peterson CA, Kern PA. Adipose tissue extracellular matrix and vascular abnormalities in obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96:E1990-8; PMID:21994960; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2011-1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Francesco F, Ricci G, D'Andrea F, Nicoletti GF, Ferraro GA. Human Adipose Stem Cells (hASCs): from bench to bed-side. Tissue Eng Part B Review; 2015; 21(6):572-84; in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eljaafari A, Tartelin ML, Aissaoui H, Chevrel G, Osta B, Lavocat F, Miossec P. Bone marrow-derived and synovium-derived mesenchymal cells promote Th17 cell expansion and activation through caspase 1 activation: contribution to the chronicity of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:2147-57; PMID:22275154; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.34391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei L, Laurence A, Elias KM, O'Shea JJ. IL-21 is produced by Th17 cells and drives IL-17 production in a STAT3-dependent manner. J Biol Chem 2007; 282:34605-10; PMID:17884812; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M705100200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahrends R, Ota A, Kovary KM, Kudo T, Park BO, Teruel MN. Controlling low rates of cell differentiation through noise and ultrahigh feedback. Science 2014; 344:1384-9; PMID:24948735; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1252079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shang Q, Bai Y, Wang G, Song Q, Guo C, Zhang L, Wang Q. Delivery of Adipose-derived Stem Cells Attenuates Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obese Mice through Remodeling Macrophage Phenotypes. Stem Cells Dev 2015; 24: 2052-64; PMID:25923535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/scd.2014.0557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]