Abstract

Aims

Increased nicotine metabolism during pregnancy could explain why nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) appears to be less effective on smoking cessation in pregnancy than in non‐pregnant smokers, but little is known about nicotine metabolism across pregnancy. This study was conducted to determine when changes in nicotine metabolism occur during pregnancy and to describe the magnitude of these changes.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study of pregnant smokers' nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR).

Setting and Participants

101 pregnant smokers recruited from hospital antenatal clinics in Nottingham, UK were asked to provide saliva samples at 8–14 weeks (n = 98), 18–22 weeks (n = 65), 32–36 weeks gestation (n = 47), 4 weeks postpartum (n = 44) and 12 weeks postpartum (n = 47).

Measurements

Nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR) was measured using the ratio of cotinine to its primary metabolite trans‐3'‐hydroxycotinine. Multi‐level modelling was used to detect any overall difference in NMR between time points. The 12 week postpartum NMR was compared with the NMRs collected antenatally and 4 weeks postpartum.

Findings

NMR changed over time (p = 0.0006). Compared with NMR at 12 weeks postpartum, NMR was significantly higher at 18–22 weeks (26% higher, 95% CI 12% to 38%) and 32–36 weeks (23% higher, 95% CI 9% to 35%). There was no significant difference between the 8‐14 weeks gestation or 4 weeks postpartum NMR and 12 weeks postpartum.

Conclusions

Nicotine metabolism appears to be faster during pregnancy; this faster metabolism is apparent from 18 to 22 weeks of pregnancy and appears to fall by 4 weeks after childbirth.

Keywords: Antenatal, metabolism, nicotine, pregnancy, postpartum, smoking

Introduction

Smoking in pregnancy is associated strongly with adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes 1. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is often provided to assist pregnant women to stop smoking, yet despite its effectiveness in non‐pregnant populations, NRT has not been found in randomized controlled trials to be effective in pregnancy, except possibly in the short term 2, 3. A potential reason for this may be that nicotine metabolism is increased during pregnancy 4, 5, 6, 7. It is possible that the dose of nicotine in NRT may not be enough to reduce cigarette cravings adequately.

Currently, we do not know exactly when changes in nicotine metabolism begin. Most studies have suggested that change in nicotine metabolism occurs by the second trimester of pregnancy, but little is known about nicotine metabolism in the first trimester and postpartum. No studies have attempted to measure the rate of nicotine metabolism from early pregnancy, throughout gestation and into the postpartum. Using saliva samples to provide current measurements of nicotine metabolism, this study aims to address the following: to (1) determine at what gestation changes in nicotine metabolism occur; and (2) describe the magnitude of changes in nicotine metabolism across pregnancy.

Methods

This is a longitudinal cohort study measuring the nicotine metabolism of pregnant and postpartum women who smoke daily. Saliva samples were analysed to obtain their nicotine metabolite ratio at five points; at recruitment between 8 and 14 weeks' gestation with follow‐up at 18–22, 32–36 weeks' gestation, and at 4 and 12 weeks postpartum.

Participants were recruited from hospital antenatal clinics in Nottingham, UK, between August 2013 and October 2013, with follow‐up completed by October 2014. Participants were included if they smoked one cigarette or more per day, were aged 16 years or over, had a singleton pregnancy and self‐reported being between 8 and 14 weeks' gestation. Participants were excluded if they self‐reported that they had consumed grapefruit within the last 24 hours 8, had liver or renal health problems or used medication other than the following: iron supplementation, vitamin supplements, folic acid and medications to treat asthma.

The researcher took written informed consent and asked participants to provide a saliva sample using a sterile Salivette swab, an exhaled carbon monoxide reading (CO) and had their height and weight measured. They were also asked to complete a short survey containing questions about their age, education, employment status and nicotine dependence, measured by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) 9.

Participants were notified by telephone or text to alert them that follow‐up saliva kits were being posted to their home, along with surveys containing questions about nicotine dependence. Anyone who had stopped smoking during the study was instructed to not provide a sample while they were abstinent. In order to encourage response rates, participants received a £5 high street shopping voucher; this amount was increased to £20 for the final postpartum sample in order to improve return rates. The study was given a favourable ethical opinion by East Midlands, Nottingham 2 Research Ethics Committee.

Sample analysis

Samples were stored frozen at –20 degrees centigrade and stored at Nottingham Health Science Biobank before being sent by courier to ABS Laboratories Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK for analysis. Assays were carried out on the saliva to provide a measurement of cotinine and trans‐3'‐hydroxycotinine. The use of saliva to measure nicotine metabolites is a validated method of assessing exposure to nicotine 10. The samples were quantified by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS).

The LC‐MS/MS method involved the addition of deuterated internal standards for both analytes, addition of a pH 7 buffer then liquid–liquid extraction using ethyl acetate prior to hydrophilic liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry using TurboIonspray in the positive ionization mode using a CTC Agilent 1100 AB SCIEX API4000 LC‐MS/MS system 11. The assay range for both analytes was 1–500 ng/mL. Any over‐range samples were diluted and re‐assayed. Precision was less than or equal to 10.3% for cotinine and less than or equal to 8.2% for 3‐hydroxy cotinine; mean accuracy ranged from 88.8 to 107% for cotinine and from 98.6 to 101% for 3'‐hydroxycotinine. Once analysis had taken place, samples were destroyed in accordance with the Human Tissue Act, 2004.

Outcome measures

Nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR) was measured by using the ratio of cotinine (COT) to its primary metabolite trans‐3'‐hydroxycotinine (3HC) in saliva 12. This method is a validated measure of nicotine metabolism 13, 14. The hepatic cytochrome CYP2A6 enzyme is responsible for the metabolism of nicotine, cotinine and 3HC, therefore NMR is a marker of CYP2A6 activity 12, 15, and a higher NMR (3HC/COT) indicates faster nicotine metabolism.

Statistical analysis

Based on previous research we assumed a standard deviation of 0.15 between time‐points 16, and taking statistical significance as P < 0.05, a sample size of 73 participants would provide 80% power to detect a difference of 0.05 (1/3 of a standard deviation). NMR was not distributed normally, and was log‐transformed to normality. Levene's test was used to confirm that there was no difference in variance of NMR between time‐points. The overall significance of the change in NMR between time‐points was assessed using a multi‐level model, which allows us to assess the significance of a change over time while allowing for the correlation between repeated measurements made on individuals.

NMR was compared descriptively between each of the five time‐points: 8–14, 18–22 and 32–36 weeks' gestation and 4 and 12 weeks postpartum. Similar to previous research, we used the 12‐week postpartum NMR as the comparison value in this study 4 and a priori‐determined paired t‐tests were performed to determine differences in NMR at 12 weeks postpartum and all other time‐points. The Bonferroni correction was used for multiple testing in the four pairwise comparisons of each time‐point with the 12‐week postpartum value 17, so P‐values of 0.01 or smaller were significant at the 5% level. We also averaged all measurements made on an individual during the antenatal period (8–14, 18–22 and 32–36 weeks) and the postpartum period (4 and 12 weeks postpartum) and compared these using a paired t‐test to determine the magnitude and statistical significance of change in NMR between the antenatal and postpartum periods. Effect sizes are presented as percent change from the 12‐week postpartum result by anti‐logging the mean difference.

We observed the 26 women who returned all five saliva samples and looked to see if the NMR followed a similar pattern of NMR over time to that described using all available samples, and then conducted multi‐level analysis to test for change over time within this subsample. Evidence suggests the contraceptive pill increases nicotine metabolism 18, 19, so we excluded those who reported using contraception at either 4 or 12 weeks postpartum.

Results

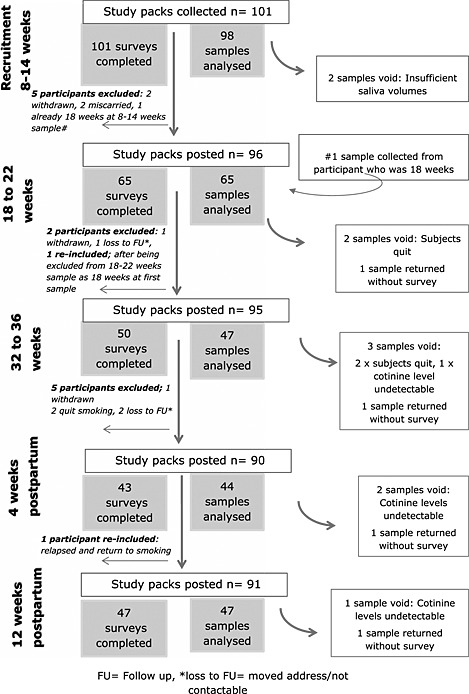

Of 101 saliva samples provided at recruitment (8–14 weeks), 98 were able to be analysed (Fig. 1). The first follow‐up at 18–22 weeks' gestation had the highest return rate (n = 65, 64%) and the lowest response rate was at 4 weeks postpartum (sample n = 44, 43%). The response for the final sample at 12 weeks postpartum was 47 (46%). A total of 79 (78%) women provided more than one sample for comparison and 26 (26%) women provided a sample at all five time‐points. The median (IQR) number of cigarettes participants smoked at each time‐point was: 8–14 weeks, 10 (5–10); 18–22 weeks, 10 (4–11); 32–36 weeks, 10 (5–10); 4 weeks postpartum, 10 (7.5–15); and 12 weeks postpartum, 10 (7–15). Two participants who provided follow‐up samples reported to have used NRT.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and follow‐up rates for samples and surveys

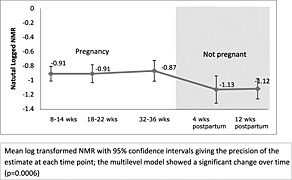

The characteristics of the 101 participants recruited can be seen in Table 1. We compared the characteristics of the entire sample at recruitment with those of participants who returned the 12‐week postpartum sample (n = 47). There was a slight difference in the median number of cigarettes smoked. Also, only one of the five non‐white ethnic participants returned a sample at 12 weeks postpartum. The remaining characteristics appeared similar between the two groups. The mean of the log‐transformed values of NMR at different time‐points is shown in Fig. 2. There was a significant difference in NMR over time (multi‐level model, P = 0.0006). Nicotine metabolism appears higher in pregnancy than outside pregnancy, and after pregnancy the ratio appears to fall by 4 weeks postpartum.

Table 1.

Characteristics of sample at recruitment and 12 weeks postpartum.

| Variables at recruitment | Recruitment: 8–14 weeks' gestation (n = 101) | Returned sample/survey at 12 weeks postpartum (n = 47) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (median, IQR) | 24 (20–28) | 25 (20–29) | ||

| Gestation at recruitment (mean and SD) | 12.3 (1.78) | 12.3 (1.77) | ||

| Cigarettes smoked at recruitment (median IQR) | 10 (5–10) | 8 (5–12) | ||

| Carbon monoxide reading (CO) | 11 (7–16) | 11 (8–16) | ||

| Employment (n, %) | ||||

| Employed | 32 | 32% | 18 | 41% |

| Unemployed | 34 | 34% | 12 | 25% |

| Full‐time student | 3 | 3% | 1 | 2% |

| Homemaker/parent | 30 | 30% | 14 | 29% |

| Other | 2 | 2% | 2 | 4% |

| Qualifications (n, %) | ||||

| None | 20 | 20% | 9 | 18% |

| GCSE or equivalent | 57 | 57% | 24 | 53% |

| A levels/equivalent | 19 | 19% | 11 | 22% |

| Degree/equivalent | 2 | 2% | 1 | 2% |

| Other | 3 | 3% | 2 | 4% |

| Partner smokes (n, %) | ||||

| Yes | 71 | 70% | 36 | 77% |

| No | 19 | 19% | 11 | 23% |

| No partner | 11 | 11% | – | – |

| Partner/family smoke in home (n, %) | ||||

| Yes | 36 | 35% | 18 | 50% |

| No | 35 | 36% | 18 | 50% |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | ||||

| White British/Irish/other white | 96 | 95% | 46 | 98% |

| Other background | 5 | 5% | 1 | 2% |

| Fagerström categorical (n, %) | ||||

| Mildly addicted < 4 | 56 | 55% | 25 | 53% |

| Moderately addicted 4–6 | 37 | 36% | 19 | 41% |

| Highly addicted 7–10 | 8 | 7% | 3 | 6% |

| BMI categorical (8–14 weeks' gestation) (n, %) | ||||

| Underweight, less than 18.5 | 9 | 8% | 3 | 7% |

| Healthy weight, 18.5–24.9 | 50 | 50% | 21 | 46% |

| Overweight, 25–29.9 | 20 | 20% | 10 | 22% |

| Obese, above 30 | 21 | 21% | 12 | 26% |

| Missing | 1 | 1% | 1 | 2% |

BMI = body mass index; GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR) over time

Table 2 shows the pairwise comparison of NMR at 12 weeks postpartum with NMR at other time‐points. After accounting for multiple comparisons, NMR was significantly higher at 18–22 weeks (P = 0.001) and 32–36 weeks (P = 0.003) compared to NMR 12 weeks postpartum. There was no statistical difference between the samples obtained at 8–14 weeks' gestation or 4 weeks postpartum and 12 weeks postpartum. The ‘within‐participant’ comparison of mean log‐transformed NMR from samples collected during pregnancy with those collected after delivery (4 and 12 weeks postpartum combined) showed that NMR was 17% higher in the antenatal period (95% CI = 6–26%, P = 0.023).

Table 2.

Pairwise comparisons of nicotine metabolism ratio (NMR) at 12 weeks postpartum with each time‐point antenatally and postpartum

| Comparison to 12 weeks postpartum | Percentage difference | 95% confidence intervals | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8–14 weeks' gestation (46 paired samples) | +15% | +1% to +26% | 0.034 |

| 18–22 weeks' gestation (37 paired samples) | +26% | +12% to +38% | 0.001* |

| 32–36 weeks' gestation (31 paired samples) | +23% | +9% to +35% | 0.003* |

| 4 weeks postpartum (35 paired samples) | +9% | –12% to +26% | 0.405 |

P values < 0.125 are significant.

The analysis involving the 26 women who returned a sample at every time‐point showed a similar pattern of NMR, and there remained a significant change in NMR over time (P = 0.003). After excluding women who reported using contraception at either 4 or 12 weeks postpartum (n = 7) the pattern of NMR over time appeared similar, and there was still a significant difference in NMR over time (P = 0.002).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the longitudinal pattern of nicotine metabolism from as early as 8 weeks' gestation until 12 weeks following birth. Our findings show that nicotine metabolism appears to be faster in pregnancy; this faster metabolism is apparent from 18 to 22 weeks of pregnancy and appears to fall by 4 weeks after childbirth

This study is one of the largest pharmacokinetic studies of any drug throughout pregnancy 20, 21. From the same women, we have been able to take repeated measures of NMR which enabled us to explore the within‐subject changes over time. To our knowledge, this is also the only study to record nicotine metabolism accurately soon after pregnancy (4 weeks postpartum) and also at a much later point following birth (12 weeks postpartum), so our finding that there was no further fall in nicotine metabolism between 4 and 12 weeks postpartum is a novel finding. We used the 12 weeks postpartum sample as our comparison sample. Ideally, the comparison NMR would have been collected before conception and participants would have been followed into pregnancy. However, recruiting prior to conception would be difficult, as most women access health‐care after finding out they are pregnant.

Our response rate fell to below 50% by the time of the 4‐week postpartum sample; this could have given rise to response bias. However, we found no major differences between women who returned the 12‐week postpartum sample and all women recruited to the cohort. We used a multi‐level model which enabled us to include all available data, but also conducted sensitivity analysis on participants who provided a sample at every time‐point; this showed a similar pattern of nicotine metabolism changes to that observed in the primary analysis, again suggesting that response bias did not impact unduly upon study results.

Consistent with a previous study, we have shown that nicotine metabolism is faster during pregnancy compared to the post‐partum period 4. Our study also found that at 18–22 and 32–36 weeks' gestation NMR was significantly different from 12 weeks postpartum. The difference between 8–14 weeks' gestation and 12 weeks postpartum was in the same direction, but was not significant after allowing for multiple testing; low statistical power may have contributed to this finding. Studies which have been able to derive longitudinal trends during pregnancy have relied upon the analysis of hair samples which cannot provide measurement at precise time‐points, and may be problematic due to contamination from hair products or passive smoking 6, 7.

Non‐pregnant women who use contraceptives containing either progesterone or a combination of oestrogen and progesterone hormones metabolize nicotine faster compared to women not using contraception 18, 19. During pregnancy these hormones begin to rise after conception, and are increased markedly throughout pregnancy. It is speculated that these hormones are responsible for the increased CYP2A6 activity during pregnancy 15. This could explain why at 4 weeks postpartum there was a decline in NMR, as following birth there would be a rapid reduction in these hormones. However, the exact causes of increased nicotine metabolism require investigation.

We hypothesized originally that if nicotine metabolism increased during pregnancy then the dose of nicotine in NRT may not be enough to alleviate nicotine withdrawal symptoms. As we have shown an increase in nicotine metabolism during pregnancy, this suggests that higher doses of NRT may be necessary. Observational evidence has shown that, during pregnancy, using a combination of long‐ and short‐term‐acting NRT (patch and a faster‐acting form) is associated with higher short‐term quit rates compared with those attributable to using either no medication or single form NRT [22]. However, to date no randomized control trials have investigated this, so further research is required on the effectiveness of higher‐dose NRT and combinations of patch plus a faster‐acting form.

In conclusion, we have shown that in pregnancy nicotine metabolism is increased compared to the postpartum period; it falls between birth and 1 month and does not seem to fall further after this.

Declaration of interests

This research is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) and under the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP‐PG‐0109‐10020). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health. K.B., T.C., S.C. and S.L. are members of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research and are members of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (http://www.ukctas.ac.uk). T.C. acknowledges the support of the East Midlands Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLARHC).

Acknowledgements

This research is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (NIHR SPCR) and under the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP‐PG‐0109‐10020). The work was carried out as part of a PhD (K.B) which is funded by the School of Medicine at the University of Nottingham. The authors would also like to acknowledge support from the Clinical Research Network (CRN) at Nottingham University Hospital, for support in the recruitment of participants. We would also like to thank ABS Laboratories Ltd for analysing the study samples and Nottingham Health Science Biobank for storing and organizing the transfer of study saliva samples.

Bowker, K. , Lewis, S. , Coleman, T. , and Cooper, S. (2015) Changes in the rate of nicotine metabolism across pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Addiction, 110: 1827–1832. doi: 10.1111/add.13029.

References

- 1. Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004; 6: S125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berlin I., Grange G., Jacob N., Tanguy M‐L. Nicotine patches in pregnant smokers: randomised, placebo controlled, multicentre trial of efficacy. BMJ 2014; 348: g1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman T., Chamberlain C., Davey M. A., Cooper S. E., Leornardi‐Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 9: CD010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dempsey D., Jacob P., Benowitz N. L. Accelerated metabolism of nicotine and cotinine in pregnant smokers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 301: 594–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Blanchette P., Klein J., Christodouleas J., Kramer M., Koren G. Nicotine metabolism in pregnant smokers measured by segmental hair analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004; 75: P38. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koren G., Blanchette P., Lubetzky A., Kramer M. Hair nicotine:cotinine metabolic ratio in pregnant women: a new method to study metabolism in late pregnancy. Ther Drug Monit 2008; 30: 246–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brajenovic N., Karaconji I. B., Mikolic A., Stasenko S., Piasek M. Tobacco smoke and pregnancy: segmental analysis of nicotine in maternal hair. Arch Environ Occup Health 2013; 68: 117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hukkanen J., Jacob P. III, Benowitz N. L. Effect of grapefruit juice on cytochrome P450 2A6 and nicotine renal clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 80: 522–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fagerstrom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res 2012; 14: 75–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benowitz N. L. Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Environ Health Perspect 1999; 107: 349–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernert J. T., Jacob P. III, Holiday D. B., Benowitz N. L., Sosnoff C. S., Doig M. V. et al. Interlaboratory comparability of serum cotinine measurements at smoker and nonsmoker concentration levels: a round‐robin study. Nicotine Tob Res 2009; 11: 1458–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. West O., Hajek P., McRobbie H. Systematic review of the relationship between the 3‐hydroxycotinine/cotinine ratio and cigarette dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011; 218: 313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levi M., Dempsey D. A., Benowitz N. L., Sheiner L. B. Prediction methods for nicotine clearance using cotinine and 3‐hydroxy‐cotinine spot saliva samples II. Model application. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2007; 34: 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dempsey D., Tutka P., Jacob P. III, Allen F., Schoedel K., Tyndale R. F. et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio as an index of cytochrome P450 2A6 metabolic activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004; 76: 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benowitz N. L., Hukkanen J., Jacob P. III. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Handbk Exp Pharmacol 2009; 192: 29–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim I., Wtsadik A., Choo R. E., Jones H. E., Huestis M. A. Usefulness of salivary trans‐3'‐hydroxycotinine concentration and trans‐3'‐hydroxycotinine/cotinine ratio as biomarkers of cigarette smoke in pregnant women. J Anal Toxicol 2005; 29: 689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bland J. M., Altman D. G. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995; 310: 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berlin I., Gasior M. J., Moolchan E. T. Sex‐based and hormonal contraception effects on the metabolism of nicotine among adolescent tobacco‐dependent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res 2007; 9: 493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benowitz N. L., Lessov‐Schlaggar C. N., Swan G. E., Jacob P. III. Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2006; 79: 480–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dawes M., Chowienczyk P. J. Drugs in pregnancy. Pharmacokinetics in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2001; 15: 819–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson G. D. Pregnancy‐induced changes in pharmacokinetics—a mechanistic‐based approach. Clin Pharmacokinet 2005; 44: 989–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brose L. S., McEwen A., West R. Association between nicotine replacement therapy use in pregnancy and smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013; 132: 660–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]