Abstract

Objective

Emerging evidence identifies disgust as a common and persistent reaction following sexual victimization that is linked to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Importantly, evidence suggests compared to fear, disgust may be less responsive to repeated exposure, which may have implications for the treatment of PTSD. The current study sought to fill a gap in the existing literature by examining reductions in sexual trauma cue-elicited disgust and anxiety upon repeated imaginal exposure.

Method

72 women with a history of sexual victimization completed a single laboratory-based session that involved repeated imaginal exposure to idiographic disgust- and fear-focused sexual trauma scripts.

Results

Results demonstrated that while anxiety and disgust declined at similar rates across exposure trials (t = −.24, p = .81), ratings of disgust (B0 = 61.93) were elevated as compared to ratings of anxiety at initiation (B0 = 51.03; t = 4.49, p < .001) of exposure even when accounting for severity of PTSD symptoms. Moreover, change in disgust significantly predicted improvement in script-elicited PTSD symptoms across the course of exposure for individuals exhibiting significant decline in anxiety (B = .006, t = 2.00, p = .048). Change in script-elicited PTSD symptoms was minimal (and was not predicted by the decline in disgust) for individuals exhibiting less change in anxiety (B = −.002, t = −0.46, p = .65).

Conclusion

These results add to an increasing literature documenting the importance of disgust in the development, maintenance, and treatment of sexual trauma-related PTSD.

Keywords: Trauma, PTSD, Disgust, Anxiety

Disgust, defined as a rejection or revulsion response aimed at distancing an individual from a potentially harmful or noxious stimulus (Davey, 1994), is increasingly recognized as a common emotional reaction to traumatic events, particularly those involving sexual victimization (Badour, Feldner, Babson, Blumenthal, & Dutton, 2013; Feldner, Frala, Badour, Leen-Feldner, & Olatunji, 2010). The ‘law of contagion,’ a heuristic outlined by Rozin and colleagues (1986) to describe the magical thinking and beliefs about the spread of contagion that are characteristic of—and apparently unique to—disgust may aid in understanding the importance of disgust following sexual assault. Central to the ‘law of contagion’ is the belief that contact with or proximity to a repulsive stimulus can result in permanent transference of the disgusting or contaminating properties of that stimulus (Rozin & Fallon, 1987; Rozin, & Nemeroff, 2002). This may lead to, for example, a sexual assault victim viewing him/herself as perpetually dirty or contaminated as a result of feelings of disgust associated with the assault (Badour, Feldner, Blumenthal, & Bujarski, 2013; Fairbrother & Rachman, 2004; Olatunji, Elwood, Williams, & Lohr, 2008). Several studies demonstrate that disgust is linked to posttraumatic stress following sexual trauma (Badour, Feldner, Blumenthal, & Bujarski, 2013; Shin et al., 1999), even when accounting for associated fear and anxiety (Badour, Feldner, Babson et al., 2013; Badour, Feldner, Blumenthal, & Knapp, 2013).

Several studies demonstrate that as compared to fear or anxiety, conditioned disgust reactions respond more slowly to exposure among persons with anxiety-based psychopathology where disgust plays a central role (i.e., specific phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder; see Mason and Richardson, 2012 for a review). Such findings have led researchers to suggest that longer or more intensive exposure may be required to sufficiently extinguish conditioned disgust, or that alternatives to traditional exposure (e.g., counter conditioning; unconditioned stimulus re-evaluation) might yield superior results for disgust. However, there has been no examination of how trauma-related disgust is influenced by exposure-based interventions. Similarly, researchers have yet to investigate whether changes in conditioned trauma-related disgust are associated with unique improvement in posttraumatic stress symptomatology. This is an important gap to address given that exposure-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) purport that symptom improvement is mediated by the reduction of conditioned fear responses via habituation (or extinction/safety learning; Foa, 1997; Keane, Zimering, & Caddell, 1985). It is possible that additional, and meaningful, symptom improvement may be driven by successful reduction in conditioned disgust. Consistent with this postulation, it may be important to examine any potential added benefit to incorporating disgust-focused content into imaginal exposure in order to enhance reduction in trauma-related disgust above and beyond traditional imaginal exposure procedures that are designed to specifically elicit conditioned fear in response to trauma-related memories. Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that adding disgust-focused exposure exercises to treatments targeting anxiety disorders may yield additional symptom improvement (Hirai et al., 2008).

In light of these gaps, the present study had several aims. First, this study sought to examine relative rates of decline in disgust and anxiety across the course of a single session of repeated imaginal exposure to sexual trauma cues. It was hypothesized that the decline in disgust would be less than the decline in anxiety, and that these differences would remain when controlling for 1) overlapping variance between the two emotions and 2) severity of PTSD symptoms. The present study also sought to systematically manipulate the emphasis of emotional content of imaginal exposure in order to deliver both disgust-focused and fear-focused traumatic event cues to all participants (counterbalancing the order of presentation) to explore the potential utility of targeting specific emotions during exposure. Presenting all participants with both disgust-focused and fear-focused cues in counterbalanced order allows for a measure of change in overall amount of responding for anxiety and disgust (across all trials) as well as a comparison of change in anxiety versus disgust responses when people are exposed to only one type of cue (across only the first phase of exposure trials). The study was also designed to alter the number of trauma-focused exposure trials by randomly assigning participants to receive an experimental or control dose (8 vs. 4 exposure trials) to examine whether a dose-effect could be identified within a single session of exposure. It was hypothesized that greater decline in disgust and anxiety responses would be observed among groups receiving more exposure trials.

Finally, the current study served as a preliminary test of whether change in disgust and/or change in anxiety is associated with change in PTSD symptoms elicited by repeated exposure to traumatic event cues. Although there is likely overlap between cue-elicited disgust and anxiety and cue-elicited PTSD symptoms (e.g., cue-elicited arousal, avoidance of cues), there are also likely to be unique features of PTSD elicited by cue exposure (e.g., dissociative symptoms; Hopper, Frewen, Sack, Lanius, & van der Kolk, 2007). Therefore, our assessment strategy included measurement of anxiety, disgust, and cue-elicited PTSD symptoms in order to capture a broad range of likely responses to trauma cue exposure. Cue-elicited PTSD symptoms were expected to decrease over the course of repeated exposure trials. It was hypothesized that change in disgust and change in anxiety would both be independently associated with the rate of symptom decline. It was further hypothesized that the greatest decline in symptoms would be observed among people evidencing the largest reduction in both disgust and anxiety responses.

Method

Participants

Participants included 72 community-recruited adult women (Mage = 31.15, SD = 13.17) who endorsed an index trauma involving sexual victimization that satisfied the definition of a traumatic event as specified in Criterion A of the DSM-IV-TR-definition of PTSD (American Psychiatric Association [APA, 2000]) and who reported experiencing significant emotions of fear and disgust during their most distressing sexual trauma (as rated by at least a 50 on a 0 [not at all afraid/disgusted]-100 [extremely afraid/disgusted] scale during an initial screening). Participants endorsed the following range of non-exclusive acts: exposing of sexual organs (22.2%), touching/fondling of sexual organs (50.0%), vaginal intercourse (36.1%), oral intercourse (19.5%), anal intercourse (4.2%), and other sexual acts (8.3%). Participants’ relationship to the assailant included relative (38.9%), intimate partner/spouse (8.3%), date (6.9%), acquaintance (11.1%), friend (9.7%), stranger (12.5%), and other (12.5%). Sixty-one individuals (84.7%) reported a history of multiple sexual trauma experiences.

Measures

Traumatic event exposure and PTSD symptoms

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) is a semi-structured interview that indexes past-month severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms and provides a current PTSD diagnosis per DSM-IV (APA, 1994). This measure has excellent psychometric properties and is considered a gold standard in PTSD assessment (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). The CAPS was used in the present study to index details regarding traumatic event exposure (e.g., most distressing event, time since exposure), severity of past-month posttraumatic stress symptoms, and past-month diagnosis of PTSD.

The Responses to Script-Driven Imagery Scale (RSDI; Hopper et al., 2007) was used to measure PTSD symptoms elicited by the script-driven imagery procedure. The RSDI is an 11-item scale that was developed to measure symptomatic responses to traumatic event cue exposure, such as that involved in the script-driven imagery procedure (Hopper et al., 2007). The RSDI has three empirically derived factors: Re-experiencing, Avoidance, Dissociation. Each symptom (e.g., “Did you avoid thoughts about the event?”, “Did you feel as though the event was reoccurring, like you were reliving it?”) is measured on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal). This measure has demonstrated good psychometric properties, including within studies employing repeated script-driven imagery procedures (Hopper et al., 2007). The RSDI evidences adequate to strong internal consistency, divergent validity, and convergent validity with self-report and physiological indices of responding to script-driven imagery as well as with established measures of PTSD symptoms and dissociation (Hopper et al., 2007). Strong reliability in RSDI ratings have been demonstrated over a one-week interval, and change in RSDI ratings assessed weekly over a course of treatment have been shown to correlate with pre-post change in PTSD symptoms assessed via established measures (Sack, Hofmann, Wizelman, & Lempa, 2008). Ratings on the RSDI were made following each script presentation, and a total symptom score for each exposure trial was calculated by summing scores for the re-experiencing, avoidance, and dissociation subscales.

Subjective responding to the script-driven imagery procedure

Consistent with previous studies using the script-driven imagery procedure (e.g., Olatunji, Babson, Smith, Feldner, & Connolly, 2009; Shin et al., 1999), ratings of self-reported disgust and anxiety were measured using visual analog scales (VAS; Freyd, 1923). Single-item VAS ratings have evidence of reliability and convergent validity with established self-report and physiological indices of emotion (Chapman, Kim, Susskind, & Anderson, 2009; Sack et al., 2008). Moreover, VAS ratings of disgust and anxiety evidence distinct response patterns following presentation of script-driven imagery procedures (Badour, Feldner, Babson et al., 2013; Olatunji, Babson, et al., 2009). In this study, participants were asked to report levels of disgust and anxiety prior to each phase of exposure (i.e., baselines) as well as following each script presentation using a 0 (no disgust/fear) to 100 (extreme disgust/fear) scale. Post-script VAS ratings were used to index emotional responding across exposure trials for all models. Ratings of script vividness were also obtained following each script using a 0 (not at all vivid) to 100 (extremely vivid) scale.

Procedure

All procedures were first approved by the University of Arkansas Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through paper and electronic flyers placed at various locations in the Northwest Arkansas community. Women deemed potentially eligible upon an initial phone screening were invited to the laboratory to complete the experimental procedure (pending final eligibility). During the laboratory session, participants first provided written informed consent and then completed the CAPS interview. Participants ineligible to complete the study at that point received $10 in compensation, and were debriefed regarding the study.

Imagery response training

All participants then completed 15 minutes of imagery response training, during which the experimenter read a series of brief standardized imagery scripts (e.g., lying on the beach, speaking in front of a large group) and trained participants to focus on their active responses in the imagery scenes (e.g., did your breathing or heart rate change?). This approach was adapted from the work of Lang, Levin, Miller, and Kozak (1983) showing that imagery response training increases synchrony between self-report and physiological measures of emotional responding to idiographic scripts.

Script generation

In collaboration with the experimenter, participants then generated four idiographic scripts (2 neutral, 2 trauma-focused [1 fear-focused, 1 disgust-focused]) in a manner consistent with previous studies utilizing the script-driven imagery procedure (Pitman, Orr, Forgue, de Jong, & Claiborn, 1987). To aid in creating disgust-focused versus fear-focused traumatic event scripts, participants completed a checklist prior to script development that included a range of physiological and behavioral responses shown to differentiate between fear-focused (e.g., heart racing, run away) and disgust-focused (e.g., gagging, take a shower) responses to standardized emotion-eliciting stimuli (Fridlund, Kenworthy, & Jaffey, 1992; Mikels et al., 2005) in an independent pilot sample of unscreened participants (N = 185; Mage = 19.25; 57.8% women). The checklist also included a range of emotionally neutral responses (e.g., heart beats steadily) to aid in development of two neutral scripts.

Neutral scripts

Participants were first asked to identify a single autobiographical experience that they considered to be emotionally neutral. They were then asked to provide ratings of the degree to which they remembered experiencing each response listed on the pre-script checklist. The experimenter then generated a list of the highest rated neutral responses and instructed participants to include these in a written narrative of the experience. Participants were also asked to incorporate any sensory information, behaviors, thoughts, feelings, or conversations that occurred during the neutral experience. The experimenter then created two 30-second audio-recorded neutral scripts from each participant’s written narrative to be presented in Phases I and II; respectively.

Trauma scripts

Participants were next asked to write about the index sexual trauma identified during the CAPS. They were given a second response checklist and were asked to provide ratings of the degree to which they experienced each of the physiological sensations and wanted to (or did) engage in any of the behaviors listed during the traumatic experience. Participants were then instructed to generate a written description of the trauma that included both disgust-focused and fear-focused response propositions along with any sensory information, thoughts, feelings, or conversations that occurred. From the single written narrative, the experimenter divided participants’ disgust- and fear-focused response propositions into two 30-second audio-recorded sexual victimization scripts (one disgust-focused, one fear-focused). Aside from varying the disgust-focused and fear-focused response propositions, every effort was made to standardize the remaining script content.

Randomization and group design

After script generation, participants were randomly assigned to groups that determined script content for the 10 trials delivered across Phases I and II of the exposure protocol. All participants received a combination of trauma-focused and neutral trials; however, script content varied as a function of 1) the number or dose of exposure trials: Experimental condition (8 trauma-focused trials [4 disgust-focused, 4 fear-focused]; 2 neutral trials) vs. Control condition (4 trauma-focused trials [2 disgust-focused, 2 fear-focused]; 6 neutral trials]), and 2) Order of stimulus presentation (Disgust-focused trials first [in Phase I] vs. Fear-focused trials first [in Phase I]). This resulted in a 4 group design: Group 1: Experimental, Disgust-focused trials first, Group 2: Experimental, Fear-focused trials first, Group 3: Control, Disgust-focused trials first, Group 4: Control, Fear-focused trials first.

Exposure phases

Consistent with prior research demonstrating differential extinction of disgust and fear (Olatunji, Smits, Connolly, Willems, & Lohr, 2007; Smits, Telch, & Randall, 2002), each exposure phase included 30-min of exposure (5-min baseline where participants were asked to sit quietly and relax in preparation for the exposure procedure, plus 5, 5-min exposure trials). Based on published script-driven imagery procedures (e.g., Orr et al., 1998; Pitman et al., 1987), each exposure trial consisted of six sections: 1) 1-min pre-script VAS ratings; 2) 30-sec baseline period; 3) 30-sec script presentation; 4) 30-sec imaginal rehearsal (period where participants were asked to sit quietly and continue to imagine the script they just heard); 5) 30-sec recovery; and 6) 2-min inter-trial-interval where participants completed post-script VAS and RSDI ratings. Phase II was identical to Phase I with the exception of script content. Groups 1 and 2 (Experimental condition) received trauma-focused script content on Trials 1-1, 1–2, 1–4, 1–5, 2-1, 2-2, 2–4, and 2–5. Groups 3 and 4 (Control condition) received trauma-focused script content on Trials 1-1, 1–5, 2–1, and 2–5. All other scripts involved neutral content.

Debriefing and compensation

Upon completion of exposure Phase II, participants were debriefed, provided with referrals to local health care providers, informed about common reactions to traumatic events, and compensated $40.

Results

Examination of intraclass correlation coefficients supported the use of linear mixed modeling with maximum-likelihood estimation (MLE) for hypothesis testing. Unless otherwise specified, unstructured covariance matrices were employed in all models. Time was modeled as follows: Trial 1-1 (0), Trial 1–2 (1), Trial 1–4 (3), Trial 1–5 (4), Trial 2-1 (5), Trial 2-2 (6), Trial 2–4 (8), Trial 2–5 (9). Trial 1-1 was coded as 0 to allow for interpretation of the intercept as an index of responding to the initial presentation of sexual trauma cues. Data for Trials 1–3 and 2–3 were not included in any models, as these trials involved presentation of neutral content for all participants. For Trials 1–2, 1–4, 2-2, and 2–4, data were only analyzed for participants in the experimental condition (Groups 1 and 2).

Descriptive Statistics and Manipulation Check

As detailed in Table 1, there were no significant group differences with regard to baseline characteristics. Participant ratings of script vividness for trial 1-1 did not vary as a function of stimulus type [disgust-focused (MGroups 1 and 3 = 74.14, SD = 23.03), fear-focused (MGroups 2 and 4 = 79.66, SD = 17.85), t = −.87, p = .39]. Counter to expectations, ratings of trial 1-1 disgust [disgust-focused (MGroups 1 and 3 = 61.74, SD = 34.34), fear-focused (MGroups 2 and 4 = 58.53, SD = 36.28), t = .38, p = .71] and trial 1-1 anxiety [disgust-focused (MGroups 1 and 3 = 49.23, SD = 31.91), fear-focused (MGroups 2 and 4 = 51.75, SD = 31.67), t = −.33, p = .74] also did not vary as a function of stimulus type. Effects of Order (disgust-focused scripts first vs. fear-focused scripts first) were all non-significant (including interactions), suggesting that the manipulation of script content to elicit more disgust or more anxiety was not effective. Raw disgust and anxiety VAS and RSDI scores for all trauma-focused exposure trials (among the total sample and within each group) are presented in Table 2 in the supplemental materials. Trial 1-1 anxiety, disgust, and RSDI ratings were all significantly positively correlated (r’s ranging from .42 – .51). As expected, these results suggest overlap among these criterion variables, but also independence sufficient to warrant analysis of each separately. Scores on the CAPS also significantly correlated with Trial 1-1 anxiety (r = .42), disgust (r = .34), and RSDI (r = .42) scores.

Table 1.

Sample Demographics and Information Regarding Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress

| Total Sample (N = 72) |

Group 1 Experimental Disgust-first (n = 19) |

Group 2 Experimental Fear-first (n = 17) |

Group 3 Control Disgust first (n = 20) |

Group 4 Control Fear-first (n = 16) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean or n |

SD or % |

Range | Mean or n |

SD or % |

Mean or n |

SD or % |

Mean or n |

SD or % |

Mean or n |

SD or % |

|

| Age (years) | 31.15 | 13.17 | 18 – 59 | 27.42 | 10.53 | 33.24 | 14.47 | 27.60 | 10.39 | 37.81 | 15.53 |

| Race | -- | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 57 | 79.2% | 15 | 78.9% | 12 | 70.6% | 17 | 85.0% | 13 | 81.3% | |

| African American | 7 | 9.7% | 2 | 10.5% | 1 | 5.9% | 2 | 10.0% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| Asian | 3 | 4.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 11.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Bi-racial/Multi-racial | 3 | 4.2% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 5.9% | 1 | 5.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Other | 2 | 2.8% | 1 | 5.3% | 1 | 5.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 5 | 6.9% | -- | 2 | 10.5% | 1 | 5.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 12.5% |

| Education | -- | ||||||||||

| High school or equivalent | 41 | 56.9% | 10 | 52.6% | 10 | 58.8% | 11 | 55.0% | 10 | 24.4% | |

| Some college | 8 | 11.1% | 4 | 21.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 15.0% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Completed 2- or 4-year college | 7 | 9.7% | 4 | 5.3% | 1 | 5.9% | 2 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Some graduate/professional school | 9 | 12.5% | 1 | 0.0% | 3 | 17.6% | 4 | 20.0% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Completed graduate/professional school | 7 | 9.7% | 0 | 26.4% | 3 | 17.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 25.0% | |

| Annual Income (in dollars) | 20,681 | 22,630 | 0 – 119,000 | 24,056 | 17,225 | 14,080 | 15,620 | 17,296 | 21,085 | 28,975 | 33,086 |

| Past-Month PTSD Symptoms (CAPS) | 32.8 | 19.56 | 5 – 91 | 35.52 | 21.97 | 29.12 | 23.13 | 34.35 | 16.73 | 31.56 | 16.65 |

| Past-Month PTSD Diagnosis (CAPS) | 13 | 18.1% | -- | 3 | 15.8% | 3 | 17.6% | 5 | 25.0% | 2 | 12.5% |

| Age at Index Trauma (in years) | 14.00 | 9.20 | 1 – 47 | 14.53 | 9.31 | 15.00 | 10.49 | 12.55 | 7.69 | 14.13 | 9.98 |

| Time Since Index Trauma (in years) | 17.15 | 14.54 | 0 – 52 | 12.90 | 11.64 | 16.65 | 4.04 | 13.09 | 2.93 | 15.81 | 3.95 |

Note: Tests of group equivalence (χ2, Fisher’s exact test, one-way ANOVA) revealed no significant differences for any of the above variables at α = .05.

Dose Effects

There were no significant Condition (Experimental [Groups 1 and 2] vs. Control [Groups 3 and 4]) effects (including interactions) in any of the models used to test study hypotheses below. As such, groups were combined together and all data were interpreted as responses to general sexual trauma cues.

Primary Hypothesis Testing

Disgust and anxiety

Data were submitted to a multivariate unconditional linear growth model (i.e., multivariate outcome [disgust, anxiety] over repeated trials) to account for covariance between change in disgust and change in anxiety. Dummy-coded intercepts for Trial 1-1 disgust, Trial 1-1 anxiety, and slopes of change for each emotion were entered into the model. A variance components covariance structure was used due to the large number of model parameters.

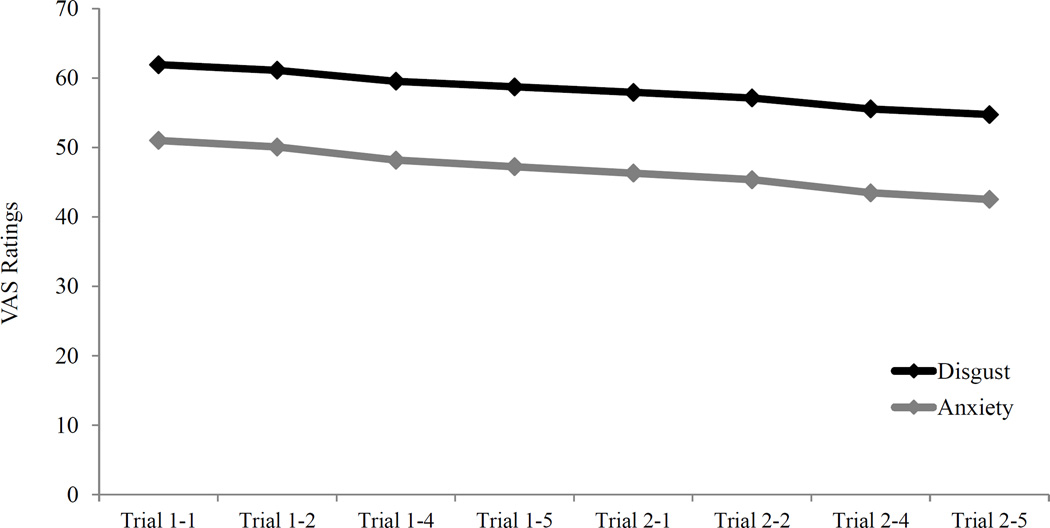

Emotional responding (i.e., disgust and anxiety VAS ratings) was significantly greater than zero following the initial presentation of trauma cues during Trial 1-1 [F(2, 131.14) = 149.06, p < .001]. Trial 1-1 ratings of disgust (B0 = 61.93) were significantly higher than ratings of anxiety (B0 = 51.03; t = 4.49, p < .001). Additionally, significant overall change in emotional responding was observed across exposure trials within this model [F(2, 149.06) = 3.90, p = .02]. Growth parameters for individual emotional responses demonstrated a significant decline in anxiety ratings across exposure trials (B = −.94, t = −2.21, p = .03) while change in disgust was nonsignificant (B = −.80 t = −1.73, p = .09). However, the rates of decline in disgust and anxiety were not significantly different when compared directly (t = −.24, p = .81; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relative rate of decline in disgust versus anxiety across the course of exposure while controlling for covariance between rates of change in the two emotions via multivariate unconditional growth analyses.

To determine whether past-month PTSD symptom severity was associated with 1) Trial 1-1 disgust or anxiety VAS ratings, or 2) change in disgust or anxiety VAS ratings across exposure trials, CAPS scores were entered as a mean-centered covariate in the multivariate model, resulting in improved model fit [χ2(1) = 16.47, p < .001]. CAPS scores were positively associated with Trial 1-1 emotional responding (B = .65, t = 4.28, p < .001); however, they were not related to change in emotional responding across exposure trials (B = −.01, t = −.28, p < .78).

Script-elicited PTSD symptoms

Individual variation in script-elicited PTSD symptoms across exposure trials was examined via a univariate unconditional linear growth model with random intercept and slopes. Mean RSDI scores following the first exposure trial were significantly greater than zero (B0 = 33.96, t = 23.19, p < .001), and symptom ratings decreased significantly across exposure trials (B = −0.59, t = −3.40, p = .001).

To examine how patterns of disgust and anxiety VAS ratings across exposure trials were related to decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms, time-varying covariates of disgust and anxiety were calculated by disaggregating the effects of each emotion across exposure trials into 1) between-person deviation in individual intercepts from the grand mean intercept (i.e., the degree to which each participant’s Trial 1-1 rating for disgust and anxiety differed from the average Trial 1-1 ratings for the entire sample), and 2) within-person deviation from individual disgust and anxiety intercepts across each exposure trial (e.g., the degree to which each participant’s VAS rating following any single trial differed from that participant’s own Trial 1-1 rating; Curran & Bauer, 2011).

Disgust and anxiety following initial presentation of sexual trauma cues

Between-person deviation in disgust and anxiety ratings following Trial 1-1 were examined as predictors of 1) Trial 1-1 script-elicited PTSD symptoms and 2) decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms across the course of exposure. Inclusion of these variables significantly improved model fit compared to the unconditional linear growth model [χ2(4) = 32.04, p < .001]. Specifically, Trial 1-1 disgust ratings were positively associated with Trial 1-1 script-elicited PTSD symptoms (B = .11, t = 2.88, p = .005) as well as with greater decline in symptoms across the course of exposure (B = −.01, t = −2.07, p = .04). Trial 1-1 anxiety ratings were similarly associated with higher script-elicited PTSD symptoms following Trial 1-1 (B = .10, t = −2.32, p = .02); however, Trial 1-1 anxiety was unrelated to symptom decline across exposure (B = .00, t = −.63, p = .53). Removal of this predictor did not reduce overall model fit [χ2(1) = .40, p = .53].

Change in disgust and anxiety responses across exposure trials

Within-person change in disgust, within-person change in anxiety, and the interaction between change in disgust and change in anxiety were also examined as candidate predictors of decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms while accounting for significant effects observed for Trial 1-1 disgust and Trial 1-1 anxiety. Addition of these predictors improved overall model fit [χ2(3) = 30.30, p < .001]. Consistent with hypotheses, change in anxiety was significantly related to decline in symptoms (B = .01, t = 3.58, p < .001). The main effect of change in disgust was not significant (B = .001 t = .20, p = .84); however, the interaction between change in disgust and change in anxiety was significant (B = −.0002, t = −2.36, p = .02). Trial 1-1 disgust (B = .11, t = 3.05, p = .003) and Trial 1-1 anxiety (B = .15, t = 3.66, p < .001) were still significantly associated with Trial 1-1 script-elicited PTSD symptoms. However, Trial 1-1 disgust was no longer a significantly related to decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms (B = −.01, t = −1.23, p = .22) after accounting for variance associated with change in disgust and change in anxiety. Removal of this predictor did not impact overall model fit [χ2(1) = 1.49, p = .22].

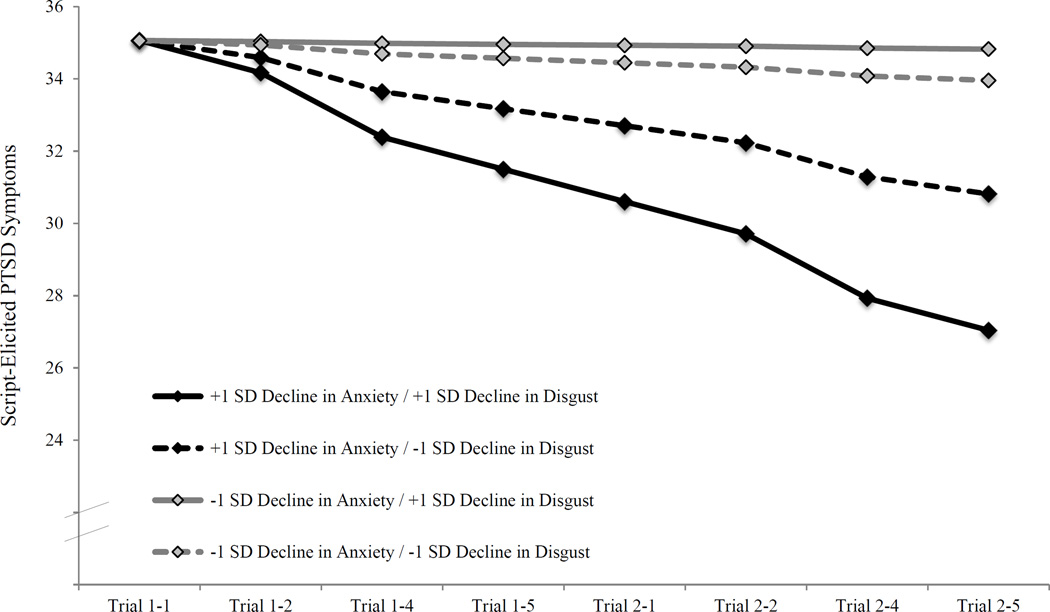

Post-hoc probing of the interaction was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of Holmbeck (2002). Specifically, decline in disgust ratings was uniquely related to decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms among individuals exhibiting the greatest decline in anxiety ratings across exposure (+1 SD for change in anxiety; B = .006, t = 2.00, p = .048). In contrast, change in disgust was not associated with decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms among individuals exhibiting less decline in anxiety ratings across exposure (−1 SD for change in anxiety; B = −.002, t = −0.46, p = .65). Notably, this group exhibited a non-significant slope of change in script-elicited PTSD symptoms overall. Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of the final model predicting change in script-elicited PTSD symptoms.

Figure 2.

Growth models for change in script-elicited PTSD symptoms across exposure trials as a function of the interaction between change in disgust and change in anxiety.

Discussion

These findings add to a growing literature documenting the importance of disgust in understanding responses to sexual trauma. It is notable that this was the first study to examine relative reductions in trauma-related disgust and anxiety, and to consider the implications of trauma-related disgust on posttraumatic stress reactions. Results demonstrated that anxiety declined significantly following repeated exposure to idiographic sexual trauma cues in the laboratory, while disgust did not. Although this pattern appears to be consistent with the hypothesis that disgust should exhibit less of a response decrement when compared with anxiety, examination of the two slopes within a single model failed to detect a statistically significant difference in the rates of decline. The non-significant slope for disgust was likely an artifact of the relatively small sample size in the present study.

Participants did, however, report significantly higher ratings of disgust as compared to anxiety following the initial presentation of sexual trauma cues during the first exposure trial. This replicates prior findings documenting an increased magnitude of disgust versus anxiety responding to script-driven imagery involving sexual trauma cues (Badour, Feldner, Babson et al., 2013). There was also an interaction between change in disgust and change in anxiety in predicting the rate of decline in script-elicited PTSD symptoms across the course of exposure. Specifically, for individuals exhibiting significant decline in anxiety, decline in disgust was associated with incremental improvement in the rate of change for script-elicited PTSD symptoms. In contrast, there was little to no change observed in script-elicited PTSD symptoms for individuals reporting minimal decline in anxiety ratings, regardless of change in disgust.

It is notable that this study failed to replicate the pattern of differential change in disgust and anxiety observed following exposure for other forms of psychopathology. While it is possible that processing of trauma-related disgust versus anxiety during exposure is unique, methodological factors may have also contributed to this finding. For example, this was the first study to examine change in disgust and anxiety during imaginal, as opposed to in vivo exposure (Olatunji et al., 2007; Olatunji, Wolitzky-Taylor, Willems, Lohr, & Armstrong, 2009; Smits et al., 2002). The specific paradigm used in this study may require modification to appropriately model imaginal exposure exercises found in empirically supported treatments for PTSD. For example, it may be valuable to implement additional experimental sessions. Indeed, basic learning research suggests the delivery of temporally spaced blocks of trials (cf., massed trials) enhances extinction learning (Cain, Blouin, & Barad, 2003), and minimizes renewal and spontaneous recovery following successful extinction (Urcelay, Wheeler, & Miller, 2009).

Despite failing to replicate differential change in disgust and anxiety following exposure, the finding that reminders of sexual trauma are associated with initially heightened intensity of conditioned disgust as compared to anxiety may still offer important implications for the treatment of posttraumatic stress. Exposure-based treatments for PTSD are couched within an anxiety habituation model of exposure (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998), wherein clinicians repeatedly assess for self-reported anxiety or general discomfort ratings in response to trauma cues until significant reductions are evidenced (i.e., evidence of habituation). Consequently, clinicians may terminate exposure prior to achieving satisfactory reductions in trauma-related disgust. This is critical in light of the present findings suggesting that change in trauma-related disgust may yield additional improvement in PTSD symptoms above and beyond the decline associated with change in anxiety. Future studies should examine how alternative approaches to exposure might differentially impact decline in trauma-related disgust and anxiety. This might include, for example, exposures designed to explicitly test expectations regarding future aversive outcomes (e.g., my boyfriend will think I’m disgusting if he knows I was raped, if I go out on my own I will be raped again; Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek, & Vervliet, 2014) or counter conditioning exercises, where trauma cues are repeatedly paired with positively valenced or appetitive stimuli (e.g., positive consensual experiences with sexual intimacy) in the absence of the aversive unconditioned stimulus (Mason & Richardson, 2012).

The manipulations aimed at varying exposure dose and developing distinct disgust-focused and fear-focused traumatic event cues were also not supported by the present results. Several methodological factors may have accounted for these findings. First, while the non-significant effect of exposure dose seems surprising, the ability to vary dose meaningfully within a single session of repeated exposure was relatively limited. Future studies with longer, or multiple exposure sessions will be needed to adequately address this issue. With respect to creating emotion-specific trauma cues, the script generation procedures may have been ineffective in creating cues that sufficiently differentiated emotional content to include a relative focus on disgust versus fear. Indeed, the physiological and behavioral response checklist developed for this study was established via responses to standardized emotion-eliciting stimuli (cf. trauma-relevant stimuli). This approach may have resulted in limited generalizability to the trauma-related emotional responses assessed among the primary sample. The within-subjects design of the current study may have also contributed the present findings in at least two ways. First, emotion ratings to the different scripts may have been influenced by the fact that participants generated a single written account of the traumatic event that incorporated both disgust-focused and fear-focused response propositions. Second, participants were exposed to a limited number of trials involving each script type. Future laboratory studies should consider a design more ideally suited to test specific hypotheses regarding targeted emotional content of exposure stimuli such as a between-subjects design in which participants receive either disgust-focused or fear-focused traumatic event stimuli to determine the number of trials required to reduce (to a predetermined threshold) both the stimulus-congruent and non-congruent emotion.

Given the emotional complexity of trauma-related memories, it may not be possible to manipulate script content to elicit an isolated emotional response. However, certain aspects of traumatic memories may still elicit disgust more readily than other aspects, and/or they may facilitate greater reductions in conditioned disgust upon repeated exposure (e.g., smell of the perpetrator, attempts to cleanse one’s body after an assault). If this is the case, there may be added treatment utility in tailoring imaginal exposure content to focus on these aspects of the traumatic memory. This may be particularly salient for people experiencing persistent problems with trauma-related disgust (e.g., aversion to physical intimacy, viewing the self as dirty or contaminated).

A number of additional limitations warrant attention. Although the decision to include participants with a range of posttraumatic stress symptoms was supported by research suggesting a dimensional (as opposed to taxonic) nature of posttraumatic stress reactions with PTSD representing the upper end of this continuum (Ruscio, Ruscio, & Keane, 2002), and PTSD symptoms severity on the CAPS was unrelated to change in disgust and anxiety in the present study, it is possible that extinction of trauma-related emotional responding may look different among individuals with clinical PTSD. The current study also focused on immediate change in script-elicited PTSD symptoms within a single exposure session. It is unclear whether within-session decline of fear or disgust has differential predictive value for longer-term changes in PTSD symptoms. As such, future research should examine these issues among people receiving multiples sessions of exposure, including those seeking treatment for PTSD. In addition, the current study included a relatively small sample of only female participants. While women disproportionately experience instances of sexual trauma (Tolin & Foa, 2008), making this an ideal initial sample, research also consistently finds differences in disgust as a function of gender (Rohrmann, Hopp, & Quirin, 2008; Schienle, Schäfer, Stark, Walter, & Vaitl, 2005), including in response to trauma-related script-driven imagery (Olatunji, Babson, et al., 2009). Future research should examine whether patterns of initial activation and reduction of trauma-related disgust and anxiety vary as a function of gender. Additional research is also needed to understand specific patterns of emotional responding following traumatic events other than sexual trauma.

Study limitations notwithstanding, the present findings offer a novel contribution to the emerging literature documenting the importance of disgust in understanding the emotional correlates of, and recovery from, posttraumatic stress reactions secondary to sexual trauma. Specifically, these findings suggest that although trauma-related disgust may decline at a similar rate to trauma-related anxiety in response to exposure, initial elevations in disgust may be higher in response to sexual trauma cues, prompting the need for additional exposure or alternative approaches to exposure to result in sufficient reductions. Results also suggest that change in trauma-related disgust may be an important mechanism in facilitating additional remediation of PTSD symptoms even after accounting for the change associated with successful reductions in trauma-related anxiety. Additional research is now needed in both laboratory and clinical settings to further elucidate our understanding of the relative roles of disgust and anxiety within the context of posttraumatic stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosures:

This research was supported by a NIMH National Research Service Award (F31 MH092994) awarded to the first author. Manuscript preparation was also supported by an NIMH award (T32 MH018869; Co-PIs Kilpatrick & Danielson). The expressed views do not necessarily represent those of NIMH. We would like to thank Thomas Adams, Erin Brannen, Jeffrey Lohr, Bunmi Olatunji, and Candice Monson for their contributions to this project.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition – Text Revision. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition. Washington, D.C.: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Badour C, Feldner M, Babson K, Blumenthal H, Dutton C. Disgust, mental contamination, and posttraumatic stress: Unique relations following sexual versus non-sexual assault. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badour C, Feldner M, Blumenthal H, Bujarski S. Examination of increased mental contamination as a potential mechanism in the association between disgust sensitivity and sexual assault-related posttraumatic stress. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013;37:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s10608-013-9529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badour C, Feldner M, Blumenthal H, Knapp A. Preliminary evidence for a unique role of disgust-based conditioning in posttraumatic stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:280–287. doi: 10.1002/jts.21796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Gusman F, Charney D, Keane T. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain C, Blouin A, Barad M. Temporally massed CS presentations generate more fear extinction than spaced presentations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2003;29:323–333. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.29.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H, Kim D, Susskind J, Anderson A. In bad taste: Evidence for the oral origins of moral disgust. Science. 2009;323:1222–1226. doi: 10.1126/science.1165565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske M, Treatnor M, Conway C, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B. Maximizing exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 58:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran P, Bauer D. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey G. Disgust. In: Ramachandran V, editor. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. San Diego, CA: San Diego Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother N, Rachman S. Feelings of mental pollution subsequent to sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:173–189. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner M, Frala J, Badour C, Leen-Feldner E, Olatunji B. An empirical test of the association between disgust and sexual assault. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E. Psychological processes related to recovery from a trauma and an effective treatment for PTSD. In: Yehuda R, McFarlane A, editors. Psychobiology of PTSD. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 410–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Rothbaum B. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd M. The graphic rating scale. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1923;14:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fridlund A, Kenworthy K, Jaffey A. Audience effects in affective imagery: Replication and extension to dysphoric imagery. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1992;16:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hair J, Anderson R, Tatham R, Black W. Multivariate data analysis. 3d ed. New York: Macmillan; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Cochra H, Meyer J, Butcher J, Vernon L, Meadows E. A preliminary investigation of the efficacy of disgust exposure techniques in a subclinical population with blood and injection fears. Behaviour Change. 2008;25:129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper J, Frewen P, Sack M, Lanius R, van der Kolk B. The Responses to Script-Driven Imagery Scale (RSDI): Assessment of state posttraumatic symptoms for psychobiological and treatment research. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29:249–268. [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Zimering RT, Caddell JM. A behavioral formulation of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. The Behavior Therapist. 1985;8:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lang P, Levin D, Miller G, Kozak M. Fear behavior, fear imagery, and the psychophysiology of emotion: The problem of affective response integration. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1983;92:276–306. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.92.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason E, Richardson R. Treating disgust in anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2012;19:180–194. [Google Scholar]

- Mikels J, Fredrickson B, Larkin G, Lindberg C, Maglio S, Reuter-Lorenz P. Emotional category data on images form the International Affective Picture System. Behavior Research Methods. 2005;37:626–630. doi: 10.3758/bf03192732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B, Babson K, Smith R, Feldner M, Connolly K. Gender as a moderator of the relation between PTSD and disgust: A laboratory test employing individualized script-driven imagery. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B, Elwood L, Williams N, Lohr J. Feelings of mental pollution and PTSD symptoms in victims of sexual assault. The mediating role of trauma-related cognitions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;22:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B, Smits J, Connolly K, Willems J, Lohr J. Examination of the rate of decline in fear and disgust during exposure to threat-relevant stimuli in blood-injection-injury phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B, Wolitzky-Taylor K, Willems J, Lohr J, Armstrong T. Differential habituation of fear and disgust during exposure to threat-relevant stimuli in contamination-based OCD: An analogue study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr S, Lasko N, Metzger L, Berry N, Ahern C, Pitman R. Psychophysiologic assessment of women with posttraumatic stress disorder resulting from childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:906–913. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman R, Orr S, Forgue D, de Jong J, Claiborn J. Psychophysiologic assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder imagery in Vietnam combat veterans. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:970–975. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800230050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S. Fear of contamination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1227–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann S, Hopp H, Quirin M. Gender differences in psychophysiological responses to disgust. Journal of Psychophysiology. 2008;22:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Fallon A. A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review. 1987;94:23–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Nemeroff C. Sympathetic magical thinking: The contagion and similarity “heuristics”. In: Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D, editors. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Millman L, Nemeroff C. Operations of the laws of sympathetic magic in disgust and other domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:703–712. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio A, Ruscio J, Keane T. The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: A taxometric investigation of reactions to extreme stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:290–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack M, Hofmann A, Wizelman L, Lempa W. Psychophysiological changes during EMDR and treatment outcome. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. 2008;2:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A, Schäfer A, Stark R, Walter B, Vaitl D. Gender differences in the processing of disgust- and fear-inducing pictures: an fMRI study. Neuroreport. 2005;16:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin L, McNally R, Kosslyn S, Thompson W, Rauch S, Alpert N, Pitman R. Regional cerebral blood flow during script-driven imagery in childhood sexual abuse-related PTSD: A PET investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:575–584. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits J, Telch M, Randall P. An examination of the decline in fear and disgust during exposure-based treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00094-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D, Foa E. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2008;1:37–85. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urcelay G, Wheeler D, Miller R. Spacing extinction trials alleviates renewal and spontaneous recovery. Learning & Behavior. 2009;37:60–73. doi: 10.3758/LB.37.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Keane T, Davidson J. Clinician-administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.