Abstract

Background and purpose

Patients with anxiety and/or depression tend to report less pain reduction and less satisfaction with surgical treatment. We hypothesized that the use of antidepressants would be correlated to patient-reported outcomes (PROs) 1 year after total hip replacement (THR), where increased dosage or discontinuation would be associated with worse outcomes.

Patients and methods

THR cases with pre- and postoperative patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were selected from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (n = 9,092; women: n = 5,106). The PROMs were EQ-5D, visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, Charnley class, and VAS for satisfaction after surgery. These cases were merged with a national database of prescription purchases to determine the prevalence of antidepressant purchases. Regression analyses were performed where PROs were dependent variables and sex, age, Charnley class, preoperative pain, preoperative health-related quality of life (HRQoL), patient-reported anxiety/depression, and antidepressant use were independent variables.

Results

Antidepressants were used by 10% of the cases (n = 943). Patients using antidepressants had poorer HRQoL and higher levels of pain before and after surgery and they experienced less satisfaction. Preoperative antidepressant use was independently associated with PROs 1 year after THR regardless of patient-reported anxiety/depression.

Interpretation

Antidepressant usage before surgery was associated with reduced PROs after THR. Cases at risk of poorer outcomes may be identified through review of the patient’s medical record. Clinicians are encouraged to screen for antidepressant use preoperatively, because their use may be associated with PROs after THR.

The prevalence of depression, assessed in several sub-populations, ranges from 3% to 20% (Blazer et al. 1994, Kessler et al. 2003, Wilhelm et al. 2003, Li et al. 2008). Depression is not limited to psychological and emotional effects alone, but is also linked to reduced physical function, greater experience of pain, and overall impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (Creed et al. 2002, Rosemann et al. 2007, Scopaz et al. 2009, Axford et al. 2010). The physical symptoms of depression may reflect those of osteoarthritis (OA). Somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbances, weight gain, and musculoskeletal aches and pains may confound the diagnosis of depression in patients living with OA (Rosemann et al. 2007). Those suffering somatic symptoms are at a higher risk of developing the psychological elements of depression as well (Tylee and Gandhi 2005).

OA is a debilitating joint disease in ageing populations (Quintana et al. 2008). Hip OA in a Swedish sub-population ranged from less than 1% in patients younger than 55 and up to 10% in those over 85 (Danielsson and Lindberg 1997). Because OA patients experience chronic pain and reduced hip function, these factors in turn have a negative influence on the patient’s HRQoL.

Total hip replacement (THR) is a highly effective treatment for most (but not all) patients suffering from severe OA of the hip (Quintana et al. 2008). Thus, identification of protective factors and risk factors associated with better and worse patient-reported outcomes (PROs) is important. Standard clinical radiographs and implant survivorship do not give the clinician a sense of how patients feel about their surgery or condition. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) enable patients to assess their own condition in the pre- and postoperative periods. Sex, age, and comorbidity status are factors that are known to influence outcomes in THR patients after primary and revision surgery (Singh and Lewallen 2009, Anakwe et al. 2011, Rolfson et al. 2011). Identification of additional preoperative risk factors may aid surgical assessment before THR, allowing physicians to anticipate patient outcomes more accurately.

Studies have shown that patients suffering from depression who undergo surgery report less satisfaction and pain reduction with treatment, and those who undergo THR have a greater risk of postoperative complications and revision (Scopaz et al. 2009, Riediger et al. 2010, Bozic et al. 2014, Browne et al. 2014). Because the prevalence of depression and/or anxiety in populations with OA has been measured to be as high as 41%, we wanted to assess PROMs 1 year after THR, taking the patient’s psychological status into account (Lin et al. 2003, Marks 2009, Scopaz et al. 2009, Axford et al. 2010). Many patients show no notable improvement from antidepressants for mild to moderate depression (Khan et al. 2002, Moncrieff and Kirsch 2005, Hermens et al. 2007, Fournier et al. 2010). As a result of these findings and the fact that some patients manage chronic pain with antidepressant medication, we analyzed a Swedish THR population to investigate the use of antidepressants, as a surrogate for psychological status, before surgery and its influence on PROMs 1 year after THR. We hypothesized that there would be a correlation between antidepressant use and poorer outcome. We also hypothesized that increased dosage and discontinuation of antidepressant medication would correlate with even poorer outcomes after THR.

Patients and methods

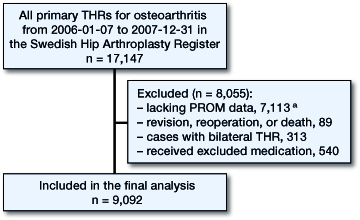

The inclusion criteria covered all the patients registered in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register who had undergone THR due to primary OA from July 2006 through December 2007 (n = 17,147). The register had a nationwide completeness of individual registration of primary THRs of 97% during the study period, a figure that is assessed annually (Karrholm et al. 2008). Participation in the register’s PROM program preoperatively and 1 year postoperatively was required. The PROM protocol comprised the HRQoL measure EQ-5D (EuroQol Group), a visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, the Charnley classification survey, and a VAS addressing satisfaction with the outcome of surgery (Rolfson et al. 2011). Anyone who died or underwent reoperation before the 1-year follow-up was excluded from the analysis. If a patient had bilateral hip surgery, only the first hip was included, except if the PROM follow-up was incomplete. When this occurred, the second hip was included if a complete PROM was available for that hip. The remaining cases were linked to the Prescribed Drug Register at the National Board of Health and Welfare (which covers all prescription purchases in Sweden since July 2005) to determine which individuals purchased prescribed antidepressants (code N06A according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] Classification System). To avoid studying groups who received antidepressants for other conditions such as addiction, cancer, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, patients taking any medication with ATC code N05A, N04, N06D, N03, N07B, N06AX12, or L02BA01 were excluded. The study population consisted of 9,092 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection of patients from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register based on the inclusion criteria of the study. aThe Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register PROM program began in 2002 at 11 hospitals. Participation gradually increased until 2008 when it was active nationwide.

Use of antidepressants in this population was defined as the purchase of antidepressant medications up to 1 year before surgery. The antidepressant group was subdivided into 5 groups. First, patients with prescription text indicating depression with no mention of anxiety were considered to be depressed. Secondly, patients with prescription text indicating anxiety with no mention of depression were considered to be anxious. Thirdly, patients who had both depression and anxiety mentioned in the prescription text were categorized as a separate mixed group. Fourthly, patients with prescription text specifying chronic pain, pain syndrome, or prescriptions of Gabapentin (N03AX12), Pregabalin (N03AX16), or Tryptizol (N06AA09)—where at least 1 of the prescription texts mentioned pain—were classified as pain syndrome patients. Those with Gabapentin or Pregabalin without any mention of pain were not included in the antidepressant group, even if they also had antidepressant treatment. Lastly, when there was no text indicating the reason for prescription of antidepressant, the patient’s diagnosis was classified as unknown.

To verify that the patients used their medication, the medication possession ratio was calculated (Andrade et al. 2006). A ratio of 1 indicated perfect compliance, where the patient was in possession of his/her medication during 100% of the treatment period, while a ratio of 0.5 indicated possession 50% of the time. A ratio above 0.8 was considered to be an indicator of good compliance.

Statistics

Linear regression analyses were performed where outcome measures (patient satisfaction, EQ-5D index and EQ VAS, and pain VAS) were dependent variables. Bayesian model averaging was used to determine which variables significantly influenced each outcome parameter, and then these variables were included in the given model (Hoeting et al. 1999, Genell et al. 2010). The independent variables tested for each model were: sex, age at surgery, whether the hip was the patient’s first or second THR, musculoskeletal comorbidities defined by Charnley class, presence of an antidepressant prescription, and the usage pattern of the antidepressant medication. Patient-reported preoperative pain (VAS pain score) and HRQoL (EQ-5D index and EQ VAS score) were also included as independent variables, as preoperative health status has an influence on how patients report their outcomes at 1 year (Greene et al. 2014, 2015a and b). Finally, the patient’s response to the fifth dimension of the EQ-5D preoperative survey indicating extreme, moderate, or no anxiety/depression was included as an independent variable (Rolfson et al. 2009). Any independent variable with a posterior probability of 0.50 or less after Bayesian model averaging was excluded from the given model (Genell et al. 2010).

Piecewise linear regression splines were applied to the EQ-5D index, EQ VAS, and pain VAS models to determine if the relationship between the preoperative and postoperative scores were linear or if they would benefit from the use of a change point to more accurately model their relationship (Greene et al. 2014). The fit of the linear regression and the segmented regression models for each outcome was tested using Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The model with the lower BIC value was used to determine the influence of the independent variables on the outcome.

SPSS statistical software version 20 was used to merge and create the study variables. R (version 3.1.2) together with the “segmented” package for change point estimation and the “BMA” package for Bayesian model averaging were used for statistical modeling. Significance for all tests was assumed with p-values ≤0.05.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Central Ethical Review Board, for the collection of PROMs (S 067-02) and merging of the Arthroplasty Register with the Prescribed Drug Register (328-08).

Results

Up to 1 year before surgery, 10% of the patients acquired antidepressants at least once (n = 943). Of the patients who were treated with antidepressants, 43% had prescription text indicating depression (n = 405), 4% had text indicating anxiety (n = 34), 6% had text indicating both depression and anxiety (n = 60), and 14% had prescription text indicating pain (n = 136). Of the individuals with text indicating treatment for pain, 29 were also treated for depression, 2 were treated for anxiety, and 2 were treated for both anxiety and depression. The remaining 341 patients (36%) with antidepressant prescription purchases had no prescription text giving the indication for the medication.

The majority of patients who took antidepressants had continuous usage throughout the observation period (n = 581, 62%). The median MPR was 0.98 (IQR: 0.85–1.0). The prevalence of antidepressant usage increased with the self-reported severity of anxiety/depression in the EQ-5D survey. 6% of patients who did not report anxiety/depression, 17% who reported moderate anxiety/depression, and 29% who reported extreme anxiety/depression used antidepressant.

Patients who used antidepressants had poorer HRQoL and higher levels of pain before and after THR, and generally experienced less satisfaction from the treatment (Table 1). Purchase of prescription antidepressants had an influence on patient-reported HRQoL (EQ-5D index and EQ VAS) and pain (VAS) 1 year after THR, but it was not associated with satisfaction with the outcome of surgery (VAS) (Table 2). Patient responses to the anxiety/depression dimension of the EQ-5D survey were, however, associated with each of the 4 outcomes irrespective of whether the respondent had an antidepressant prescription or not, and they were therefore included in each of the regression models. Similarly, age, Charnley classification, and preoperative EQ VAS score were included in each of the 4 outcome models. The hip order variable alone (whether the included hip was the first or second treated with THR) was not included in any of the regression models (Table 2).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population, with absolute number (percentage) for proportions and mean (SD) for continuous variables. The population was divided into patients with and without antidepressant prescriptions

| All patients | Antidepressant prescription |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Variable | n = 9,092 | n = 8,149 | n = 943 |

| Age, years | 69 (9.8) | 69 (9.8) | 69 (10.1) |

| Female, n (%) | 5,106 (56) | 4,402 (54) | 704 (75) |

| Charnley class, n (%) | |||

| A | 4,176 (46) | 3,840 (47) | 336 (36) |

| B | 1,149 (13) | 1,043 (13) | 106 (11) |

| C | 3,767 (41) | 3,266 (40) | 501 (53) |

| EQ-5D index | |||

| Preoperative | 0.430 (0.308) | 0.443 (0.304) | 0.323 (0.322) |

| Postoperativea | 0.792 (0.228) | 0.803 (0.220) | 0.701 (0.277) |

| EQ VAS | |||

| Preoperative | 55 (22) | 56 (22) | 49 (22) |

| Postoperativea | 77 (20) | 78 (19) | 70 (23) |

| Pain VAS | |||

| Preoperative | 60 (17) | 60 (17) | 64 (16) |

| Postoperativea | 14 (18) | 13 (17) | 18 (20) |

| Satisfaction VAS | |||

| Postoperativea | 16 (20) | 16 (20) | 19 (23) |

1 year postoperative

Table 2.

The posterior probability threshold of each independent variable as determined by Bayesian model averaging. Any variable with a probability of ≥0.50 was subsequently included in the linear regression model for that outcome parameter (a)

| Patient-reported outcome |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | Satisfaction | |||

| Variable | index | EQ VAS | Pain VAS | VAS |

| Age, years | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a |

| Sex | 0.18 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.62a |

| Charnley classification | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a |

| Preoperative EQ-5D index | 1.0a | 0.89a | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Preoperative EQ VAS | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a |

| Preoperative pain VAS | 1.0a | 0.0 | 1.0a | 0.0 |

| Hip order | 0.0 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.49 |

| 5th dimension of EQ-5D | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a | 1.0a |

| Antidepressants N06A | 1.0a | 1.0a | 0.78a | 0.0 |

The EQ-5D index was the only model that benefited from the use of piecewise linear regression splines with a change point at a preoperative EQ-5D index of 0.051 (95% CI: 0.001–0.101). Individuals with preoperative EQ-5D index values less than 0.051 were considered to have low preoperative HRQoL, while those with index values of 0.051 or greater were considered to have high preoperative HRQoL. Those with low preoperative HRQoL improved at a greater rate than those with high scores (Table 3) due to the capacity of the scale; however, they did not achieve postoperative EQ-5D indices that were as high.

Table 3.

Regression β-coefficients and 95% CIs for the continuous independent variables, for each outcome measure

| Outcome model Independent variable | β | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D Index | ||

| Age, years | −0.002 | −0.002 to −0.001 |

| Preoperative EQ-5D index | ||

| low | 0.497 | 0.296 to 0.698 |

| high | 0.034 | 0.014 to 0.055 |

| Preoperative EQ VAS | 0.001 | 0.0006 to 0.0010 |

| Preoperative Pain VAS | −0.001 | −0.0009 to −0.0003 |

| EQ VAS | ||

| Age, years | −0.23 | −0.27 to −0.19 |

| Preoperative EQ-5D index | 2.63 | 1.20 to 4.06 |

| Preoperative EQ VAS | 0.12 | 0.10 to 0.14 |

| Pain VAS | ||

| Age, years | 0.08 | 0.05 to 0.12 |

| Preoperative EQ VAS | −0.05 | −0.06 to −0.03 |

| Preoperative Pain VAS | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.08 |

| Satisfaction VAS | ||

| Age, years | 0.21 | 0.17 to 0.25 |

| Preoperative EQ VAS | −0.04 | −0.06 to −0.02 |

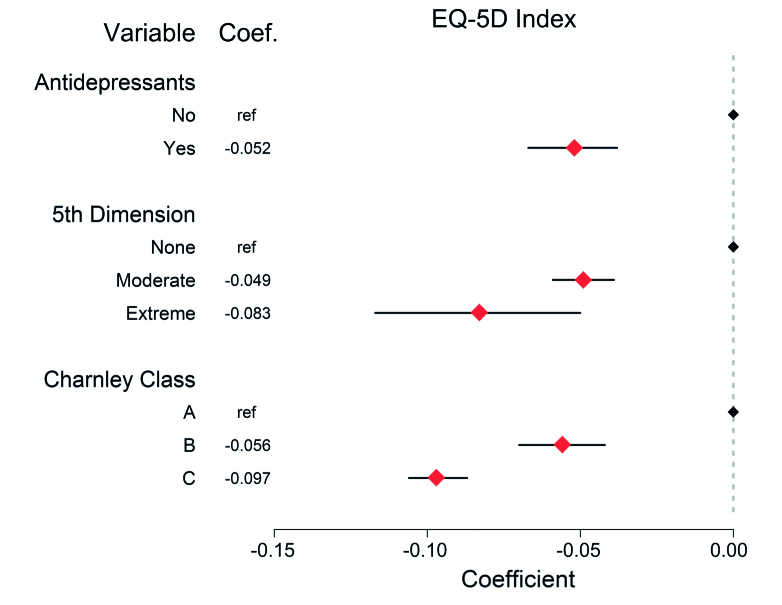

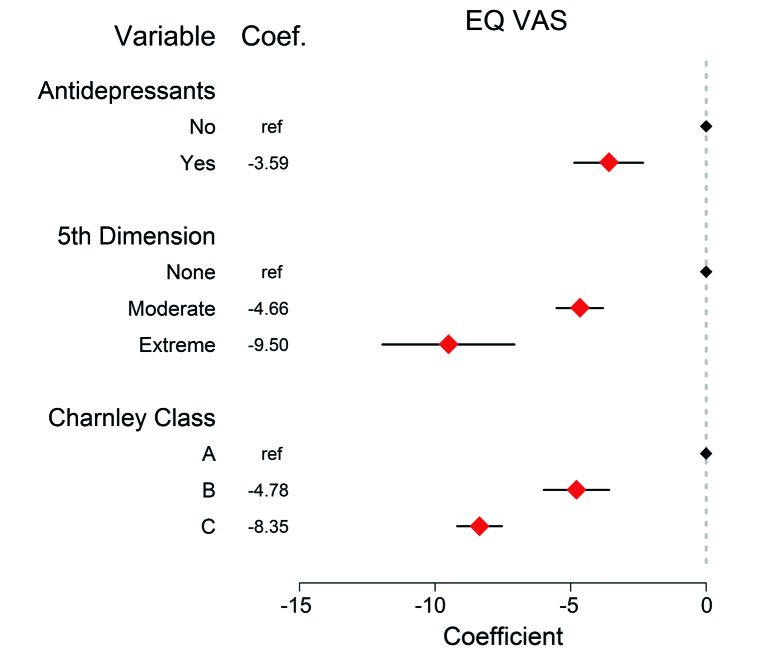

Controlling for age at surgery, musculoskeletal comorbidities, preoperative HRQoL (EQ-5D index and EQ VAS), and preoperative pain, possession of a prescription for antidepressant medication had a negative influence on patient-reported HRQoL, as reflected in both the EQ-5D index (Figure 2) and the EQ VAS (Figure 3) 1 year after THR. More striking was the influence of self-reported anxiety/depression in the fifth dimension of the EQ-5D survey, where those who reported extreme anxiety/depression had significantly lower EQ-5D indices and EQ VAS scores. In the case of the EQ VAS, patients who reported extreme anxiety/depression had worse scores than individuals with multiple musculoskeletal comorbidities.

Figure 2.

Linear regression results of the independent categorical variables including the dichotomous antidepressant variable, where the points represent the slope coefficient with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the dependent EQ-5D index variable. EQ-5D indices can range from –0.594 to 1.0. Any variable without a CI was the reference variable and any CI that did not include 0 represents a significant influence on the EQ-5D index. Preoperative EQ-5D index, EQ VAS, pain VAS, and age were the influential continuous variables on postoperative EQ-5D indices as indicated in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Linear regression results of the independent categorical variables including the dichotomous antidepressant variable, where the points represent the slope coefficient with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the dependent EQ VAS variable. EQ VAS values can range from 0 to 100. Any variable without a CI was the reference variable and any CI that did not include 0 represents a significant influence on the EQ VAS. Preoperative EQ-5D index and EQ VAS scores and age were the influential continuous variables on postoperative EQ VAS scores as indicated in Table 3.

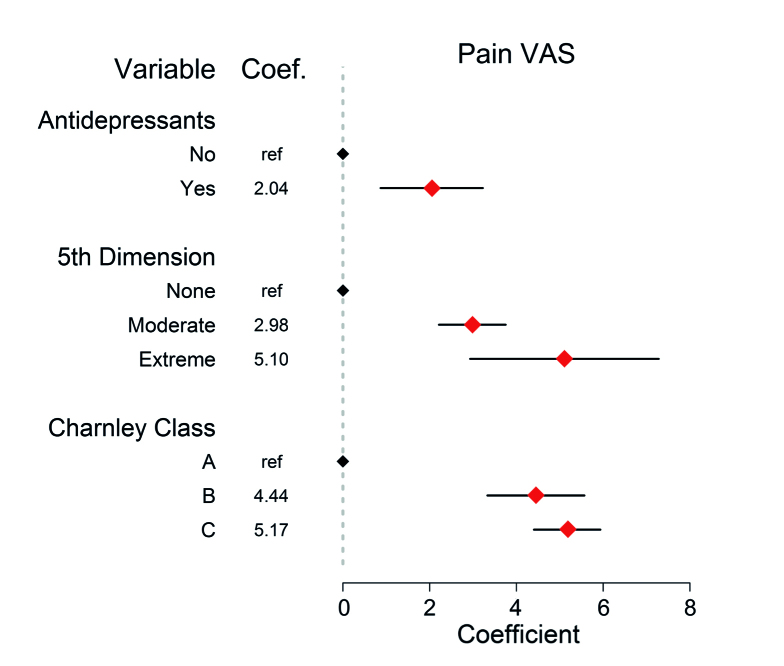

Controlling for age at surgery, musculoskeletal comorbidities, preoperative HRQoL (EQ VAS), and preoperative pain, individuals with antidepressant prescriptions tended to report postoperative pain levels 2 points greater on the pain VAS than their peers did. Consistent with the postoperative HRQoL trends, patients who reported extreme anxiety/depression in the preoperative EQ-5D survey reported significantly higher postoperative pain (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Linear regression results of the independent categorical variables including the dichotomous antidepressant variable where the points represent the slope coefficient with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the dependent pain VAS variable. Pain VAS values can range from 0 to 100. Any variable without a CI was the reference variable and any CI that did not include 0 represents a significant influence on the pain VAS. Preoperative EQ VAS and pain VAS scores and age were the influential continuous variables on postoperative pain VAS scores as indicated in Table 3.

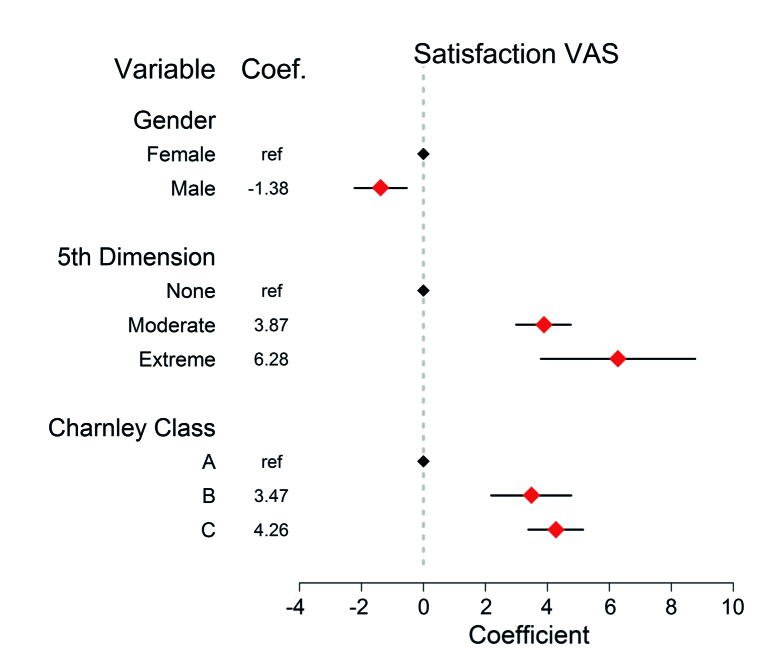

Antidepressant prescriptions did not appear to influence patient-reported satisfaction with the outcome of THR 1 year after surgery. Self-reported anxiety/depression did, however, have a negative influence on how patients reported their satisfaction as much as or more than the presence of additional musculoskeletal comorbidities (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Linear regression results of the independent categorical variables including the dichotomous antidepressant variable where the points represent the slope coefficient with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the dependent satisfaction VAS variable. Satisfaction VAS values can range from 0 to 100. Any variable without a CI was the reference variable and any CI that did not include 0 represents a significant influence on the satisfaction VAS. Preoperative EQ VAS and age were the influential continuous variables on satisfaction VAS scores as indicated in Table 3.

Discussion

Controlling for the known confounders sex, age, comorbidity, and preoperative health status, we found that the use of antidepressants was associated with more pain and lower HRQoL before and at 1 year after surgery. The influence of antidepressants on outcomes was independent of the response to the anxiety/depression dimension of the preoperative EQ-5D questionnaire.

The strength of this study stems from the use of the nationwide register of OA patients receiving THR. In conjunction with the nationwide register of prescription drug purchases, we were able to create a homogenous study population that excluded important confounding groups. Specialized code allowed the identification of various stages and severity of disease in patients taking antidepressant medications. Finally, rigorous validation ensured viable data and robust statistical methods accounted for multiple variable types.

A limitation of this investigation was that in 36% of the patients the indication for the antidepressant medications could not be identified. A review of a Swedish sub-population found that antidepressants were primarily prescribed for depression (66%), followed by anxiety (14%), and treatment of pain (11%), giving an idea of the distribution—but not specifically in an OA population (Henriksson et al. 2003). Another limitation is that we cannot know with certainty that patients took the medication prescribed. However, there is strong indication that most patients were following the treatment set by their physician because 62% of them continually obtained prescriptions throughout the study period, and the medication possession ratio was very high at 98%. The variety of clinical indications for prescription of antidepressants and the unknown definitive level of compliance with treatment may limit our understanding of how psychological distress truly influences PROs in this population. The aim of the study was to investigate preoperative factors associated with poor patient outcomes. For this reason, we did not investigate the novel, continued, increased, or discontinued use of antidepressants after surgery. Studies that focus on these postoperative factors—such as the work of Duivenvoorden et al. (2013)—help to explain how antidepressant treatment continues to influence PROs after surgery. The use of PROMs with bounded scores may have been a limitation in this investigation, but this will always be the case in studies using standardized patient-reported data. As soon as a measure has an upper or lower bound, there is the opportunity for ceiling or floor effects. Patients with very high preoperative scores have little room for measurement of improvement after THR, and the sensitivity of the scale for those patients may be questioned. We did our best to mitigate this by applying a change point where it was relevant (EQ-5D index), and we were able to measure average improvement in these patients with high HRQoL before surgery, indicating that there was sufficient statistical power in this large population for skewed data not to be a concern.

Currently, sex, age, and comorbidity status are considered before THR surgery (Espehaug et al. 1998, Rolfson et al. 2009, Anakwe et al. 2011). Since these known predictors are accounted for preoperatively, our findings suggest that patients undergoing treatment for depression may also benefit from special consideration and perhaps education before THR, to better understand how their mental state and their medication usage patterns may influence their outcomes after surgery.

The sale of antidepressants in Sweden increased 6-fold from 1990 to 2002 (from 9 to 57 defined daily doses per 1,000 inhabitants), which is consistent with increases in treatment of depression seen in other populations (Henriksson et al. 2003, Kessler et al. 2003, Henriksson and Isacsson 2006). The substantial increases in antidepressant prescriptions triggered a number of groups to examine the effectiveness of this treatment, and they found that efficacy varies substantially as a function of the severity of depression symptoms. At baseline, patients who were severely ill benefited from antidepressants, but patients who had mild, moderate, or even severe symptoms had no marked improvement from antidepressants (relative to placebo treatment or standard primary care) (Khan et al. 2002, Moncrieff and Kirsch 2005, Hermens et al. 2007, Fournier et al. 2010). While a proportion of our treated study patients may have been experiencing benefits from their antidepressant treatment, others may have seen little effect on their condition—as indicated by the proportion of antidepressant patients who reported having extreme problems in the anxiety/depression dimension of the EQ-5D preoperatively. At the same time, we presume that some proportion of the study population was experiencing symptoms of depression, anxiety, or pain syndrome but was not receiving treatment for them, as indicated in the self-reported anxiety/depression dimension of the EQ-5D survey. Because some of the patients may have been experiencing these conditions but not taking antidepressants, the effect of depression, anxiety, and pain syndrome on PROs was probably dampened in this population—thus suggesting that these conditions may have an even greater negative effect on pain reduction, satisfaction, and improvement in HRQoL after surgery than the results of this study suggest. For these reasons, a prospective study assessing the presence of depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, or pain syndrome symptoms with specific measures might better determine how these conditions influence PROs.

Osteoarthritis, depression, and pain are commonly treated in the primary care setting. Physiotherapy and education about OA in the early stages of the disease could teach patients how to cope with their musculoskeletal pain. Because OA patients sometimes associate activity with increased pain and therefore assume that additional injury is occurring, fear may play a role in inhibiting patient activity. Contrary to what patients might assume, avoidance of activity may in fact contribute to physical deterioration and muscle weakness (Heuts et al. 2004). Depression in patients with OA has been linked to sensitivity to pain and reduced ability to cope with the disease (Rosemann et al. 2007). Because depressive disorders are common in patients with chronic pain, education about continued activity should be considered not only as a non-surgical treatment for OA, but also as a preventative measure against the development of depression (Tylee and Gandhi 2005).

Our findings suggest that the patient’s mental health status before surgery is associated with PROs, which is consistent with the findings of McHugh et al. (2013). Poorer outcomes associated with antidepressant use may be due to inadequate participation in rehabilitation because of fear of or low levels of motivation, heightened pain sensitivity, reduced ability to cope with illness, and/or lower or uncertain expectations of pain relief and functional recovery (Lin et al. 2003, Rosemann et al. 2007, Marks 2009, Singh and Lewallen 2009, Axford et al. 2010). Identification of antidepressant users preoperatively may allow the surgeon to address these areas of concern before surgery and further encourage participation in rehabilitation after surgery, in the hope of avoiding persistent pain and dissatisfaction with treatment.

A recent study found that patients with a history of depression experienced substantially more pain before surgery than those without any history of mood disorders (Marks 2009). Axford et al. (2010), on the other hand, found only weak correlations between depression status and level of pain experienced by the patient. Other studies have found that pain was actually the greatest predictor of depression in patients with OA, raising the question of whether the pain had led to depression or whether depression had caused the patient to experience a greater level of pain (Rosemann et al. 2007). Regardless of which condition occurred first, the diagnosis of depression in patients afflicted with chronic pain could shed light on the best way to treat their pain.

The expectations of pain reduction and improved HRQoL are the most common reasons for patients seeking THR. Thus, failure to reduce pain for any reason may have a negative influence on patient satisfaction and HRQoL (Anakwe et al. 2011). Identification of risk factors for continued pain after surgery enables clinicians to improve the usefulness of THR for patients with preoperative predictors of poor patient outcomes. For these patients, preoperative education and/or non-surgical interventions may be used to improve the outcome of THR later. Lin et al. (2003) showed that arthritis patients who received enhanced depression care that involved antidepressants and/or psychotherapy sessions showed marked improvements in pain, physical function, and HRQoL. These results indicate that for some patients, treatment of their depression may actually improve their ability to cope with their joint disease even without surgery.

Understanding a patient’s mental health before surgery may play a key role in management and education of patients eligible for THR. Patients receiving treatment with antidepressant medications should be informed of the risks associated with their course of treatment. Our findings add knowledge to preoperative risk assessment. Patients at risk of having poorer outcomes may be identified through review of their medical records, and clinicians are encouraged to review or screen OA patients for psychological distress and inform them of the risk of inferior outcomes.

MEG: study design, data analysis, statistics, and interpretation of data. OR: study design, and analysis and interpretation of data. MG: study design, and preparation, merging, and analysis of data. KA: validation of data, clinical classifications, and interpretation of data. HM and GG: study design and interpretation of data. All the authors edited the manuscript and approved the final draft.

We thank Szliard Nemes for his guidance with the statistical part of the work. The study was funded by the Harris Orthopaedic Laboratory and the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. OR received funding through grants from the Felix Neubergh Foundation, the Göran Bauer Grant, the Swedish Society of Medicine, and the Wangstedt Foundation.

References

- Anakwe R E, Jenkins P J, Moran M. Predicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patients. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (2): 209–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade S E, Kahler K H, Frech F, Chan K A. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidem Dr S 2006; 15(8), 565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axford J, Butt A, Heron C, Hammond J, Morgan J, Alavi A, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis: use of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale as a screening tool. Clin Rheumatol 2010; 29 (11): 1277–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D G, Kessler R C, McGonagle K A, Swartz M S. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151 (7): 979–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic K J, Lau E, Ong K, Chan V, Kurtz S, Vail T P, et al. Risk factors for early revision after primary total hip arthroplasty in Medicare patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (2): 449–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J A, Sandberg B F, D’Apuzzo M R, Novicoff W M. Depression is associated with early postoperative outcomes following total joint arthroplasty: a nationwide database study. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (3): 481–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed F, Morgan R, Fiddler M, Marshall S, Guthrie E, House A. Depression and anxiety impair health-related quality of life and are associated with increased costs in general medical inpatients. Psychosomatics 2002; 43 (4): 302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson L, Lindberg H. Prevalence of coxarthrosis in an urban population during four decades. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; (342): 106-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duivenvoorden T, Vissers M M, Verhaar J A, Busschbach J J, Gosens T, Bloem R M, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms before and after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective multicentre study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (12): 1834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Langeland N, Vollset S E. Patient satisfaction and function after primary and revision total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998; (351): 135-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J C, DeRubeis R J, Hollon S D, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam J D, Shelton R C, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Amer Med Assoc 2010; 303 (1): 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genell A, Nemes S, Steineck G, Dickman P W. Model selection in medical research: a simulation study comparing Bayesian model averaging and stepwise regression. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010; 10: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M E, Rolfson O, Nemes S, Gordon M, Malchau H, Garellick G. Education attainment is associated with patient-reported outcomes: findings from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (6): 1868–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M E, Rolfson O, Garellick G, Gordon M, Nemes S. Improved statistical analysis of pre- and post-treatment patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): the applicability of piecewise linear regression splines. Qual Life Res 2015a; 24(3): 567–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M E, Rolfson O, Gordon M, Garellick G, Nemes S. Standard comorbidity measures do not predict patient-reported outcomes 1 year after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015b; 473(11): 3370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson S, Isacsson G. Increased antidepressant use and fewer suicides in Jamtland county, Sweden, after a primary care educational programme on the treatment of depression. Acta Psychiat Scand 2006; 114 (3): 159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson S, Boethius G, Hakansson J, Isacsson G. Indications for and outcome of antidepressant medication in a general population: a prescription database and medical record study, in Jamtland county, Sweden, 1995. Acta Psychiat Scand 2003; 108 (6): 427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermens M L, van Hout H P, Terluin B, Ader H J, Penninx B W, van Marwijk H W, et al. Clinical effectiveness of usual care with or without antidepressant medication for primary care patients with minor or mild-major depression: a randomized equivalence trial. BMC Med 2007; 5: 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuts P H, Vlaeyen J W, Roelofs J, de Bie R A, Aretz K, van Weel C, et al. Pain-related fear and daily functioning in patients with osteoarthritis. Pain 2004; 110 (1-2): 228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeting J A, Madigan D, Raftery A E, Volinsky C T. Bayesian model averaging: a tutorial. Statistical Sci 1999; 14 (4): 382–417. [Google Scholar]

- Karrholm J, Garellick G, Rogmark C, Herberts P Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2007. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: Sweden; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R C, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas K R, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). J Amer Med Assoc 2003; 289 (23): 3095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Leventhal R M, Khan S R, Brown W A. Severity of depression and response to antidepressants and placebo: an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Clin Psychopharm 2002; 22 (1): 40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Age-specific familial risks of anxiety. A nation-wide epidemiological study from Sweden. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2008; 258 (7): 441–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E H, Katon W, Von Korff M, Tang L, Williams J W Jr., Kroenke K, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003; 290 (18): 2428–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R. Comorbid depression and anxiety impact hip osteoarthritis disability. Disabil Health J 2009; 2 (1): 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh G A, Campbell M, and Luker K A. Predictors of outcomes of recovery following total hip replacement surgery. Bone Joint Res 2013; 2 (11): 248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieff J, Kirsch I. Efficacy of antidepressants in adults. BMJ 2005; 331 (7509): 155–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana J M, Arostegui I, Escobar A, Azkarate J, Goenaga J I, Lafuente I. Prevalence of knee and hip osteoarthritis and the appropriateness of joint replacement in an older population. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168 (14): 1576–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger W, Doering S, Krismer M. Depression and somatisation influence the outcome of total hip replacement. Int Orthop 2010; 34 (1): 13–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson O, Dahlberg L E, Nilsson J A, Malchau H, Garellick G. Variables determining outcome in total hip replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (2): 157–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfson O, Karrholm J, Dahlberg L E, Garellick G. Patient-reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (7): 867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosemann T, Backenstrass M, Joest K, Rosemann A, Szecsenyi J, Laux G. Predictors of depression in a sample of 1,021 primary care patients with osteoarthritis. Arthrit Rheum 2007; 57 (3): 415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopaz K A, Piva S R, Wisniewski S, Fitzgerald G K. Relationships of fear, anxiety, and depression with physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2009; 90 (11): 1866–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Lewallen D. Age, gender, obesity, and depression are associated with patient-related pain and function outcome after revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Rheumatol 2009; 28 (12): 1419–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylee A, Gandhi P. The importance of somatic symptoms in depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 7 (4): 167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Mitchell P, Slade T, Brownhill S, Andrews G. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV major depression in an Australian national survey. J Affect Disorders 2003; 75 (2): 155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]