Abstract

Cell-cell fusion is fundamental to a multitude of biological processes ranging from cell differentiation and embryogenesis to cancer metastasis and biomaterial-tissue interactions. Fusogenic cells are exposed to biochemical and biophysical factors, which could potentially alter cell behavior. While biochemical inducers of fusion such as cytokines and kinases have been identified, little is known about the biophysical regulation of cell-cell fusion. Here, we designed experiments to examine cell-cell fusion using bulk metallic glass (BMG) nanorod arrays with varying biophysical cues, i.e. nanotopography and stiffness. Through independent variation of stiffness and topography, we found that nanotopography constitutes the primary biophysical cue that can override biochemical signals to attenuate fusion. Specifically, nanotopography restricts cytoskeletal remodeling-associated signaling, which leads to reduced fusion. This finding expands our fundamental understanding of the nanoscale biophysical regulation of cell fusion and can be exploited in biomaterials design to induce desirable biomaterial-tissue interactions.

Fusion of cells to form multinucleated giant cells constitutes an integral component of various physiological processes including the biomaterial-induced foreign body response (FBR)1,2,3,4. For example, fusion of macrophages on the surface of biomaterials results in the formation of foreign body giant cells (FBGCs), which contribute to the progression of biomaterial-induced FBR4,5,6,7,8,9. Similarly, fusion of myoblasts leads to the formation of multinucleated myotubes in a process called myogenesis10,11. Myogenesis contributes to muscle development during embryogenesis as well as muscle regeneration during tissue repair. Modulation of cell fusion by biochemical signals such as cytokines, kinases and GTPases has been studied extensively7,9,11,12,13,14. It has also been reported that specific cell co-cultures can lead to cell fusion. For example, co-culture of macrophages and fibroblasts can lead to formation of fibroblast-derived multinucleated giant cells15. Additionally, soluble polymers such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) have also been shown to induce cell-cell fusion in vitro16,17.

Unlike biochemical induction, the biophysical regulation of cell fusion is not well understood. Biophysical cues such as topography and stiffness are ubiquitous in the native ECM and implanted biomaterials5,18. Biophysical regulation of cell behavior has been extensively studied using micro/nanostructured materials generated by employing lithography-based techniques as well as alternate methods such as modified polymer demixing/spin-coating and colloidal chemistry based techniques19,20,21. Such patterned materials have been employed to investigate the effect of topography and stiffness on multiple cell types including fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells and stem cells5,22,23,24,25,26,27. Exploring the effect of these biophysical parameters on cell fusion could uncover unknown aspects of cell physiology, already present in nature. In this regard, micro- and nanopatterned biomaterials have been employed to investigate the effect of topography on cell fusion5,24,25,28,29,30. Specifically, micron-sized ridges or gratings have been shown to increase cell alignment and cell fusion in myoblasts and macrophages29,30,31. Additionally, it has been suggested that micro islands and nanotubes can be used to modulate cell fusion26,32,33. While these studies provide evidence that topography can induce changes in cell fusion, there is no consensus on how the fusogenic capacity of primary cells changes in response to the biomechanical cues presented by nanopatterned biomaterials. Specifically, our current understanding of cell fusion cannot distinguish between topographical features and stiffness due to experimental limitations.

Additionally, most of the studies described above employed polymers to investigate the effect of topography on cell fusion. Polymers constitute a versatile, easily processable class of materials and have been instrumental to our understanding of cell-biomaterial interactions. Metals and metallic alloys constitute another class of materials often used to develop biomaterials for bone replacements, cardiovascular stents and other applications. Metals display high elastic moduli and corrosion resistance, and have been traditionally used for structural implants34. However, the practical applicability of nanopatterning strategies with metals is restricted due to intrinsic limits in processability of high-strength metals. Hence, there is a clinical need for biocompatible, high strength materials that can be processed at various length scales including the nanoscale. Bulk metallic glasses (BMGs), metallic alloys with an amorphous atomic structure, constitute a class of materials ideally suited to address the clinical need described above35,36,37,38,39. BMGs possess metal-like properties such as high strength and elastic moduli, and increased resistance to corrosion and wear35. Unlike conventional metals, BMGs lack a microstructure comprised of crystals, decorated with dislocations and separated by grain boundaries. Instead, their atomic structure results in a homogenous and isotropic material with unique properties. For example, BMGs exhibit a unique temperature-dependent mechanical behavior, which enables polymer-like processability at temperatures higher than the critical BMG-specific glass transition temperature40,41. Therefore BMG alloys combine metal-like strength and stiffness with polymer-like processability. Nanopatterning of biomaterials to engineer cellular response has been suggested for polymer-based materials previously5. Development of BMG nanorods enable the application of nanopatterning-based strategies with high strength and stiffness materials. We recently demonstrated that thermoplastic forming of Platinum-based BMGs (Pt57.5Cu14.7Ni5.3P22.5, Pt-BMGs) above its glass transition temperature can be exploited to generate a variety of precise nanorod arrays with feature sizes below 100 nm37.

In the present study, we employed thermoplastic forming to generate Pt-BMG nanorod arrays to investigate the effect of topographical features and stiffness on cell fusion. Thermoplastic forming of BMGs is uniquely suited to generate surfaces to study these properties. The forming process involves heating the BMG to its supercooled liquid region, the temperature range where the glass relaxes into a liquid before it eventually crystallizes. Pressure is applied to mold the BMG into commercially available nanoporous alumina molds. The porous morphology of the alumina mold determines the topographical parameters such as nanorod diameter and inter-nanorod spacing (pitch).

Analysis of fusion revealed that various nanopattern arrays could reduce fusion, with 55 nm nanorods displaying maximum attenuation. Nanorod length was independently manipulated to generate identical nanorod arrays in terms of diameter and pitch with distinct aspect ratios between 7 and 2, which corresponded to a forty-fold difference in nanorod stiffness. Despite this variation in individual nanorod stiffness, these nanorod arrays induced a similar reduction in cell fusion, indicating that topographical cues can override biochemical signals to attenuate fusion. Nanotopography-induced attenuation of cell fusion was mediated by compromised activation of p38 MAP kinase and inhibition of cytoskeletal remodeling.

Results

Biophysical regulation of cell-cell fusion: Topography vs. Stiffness

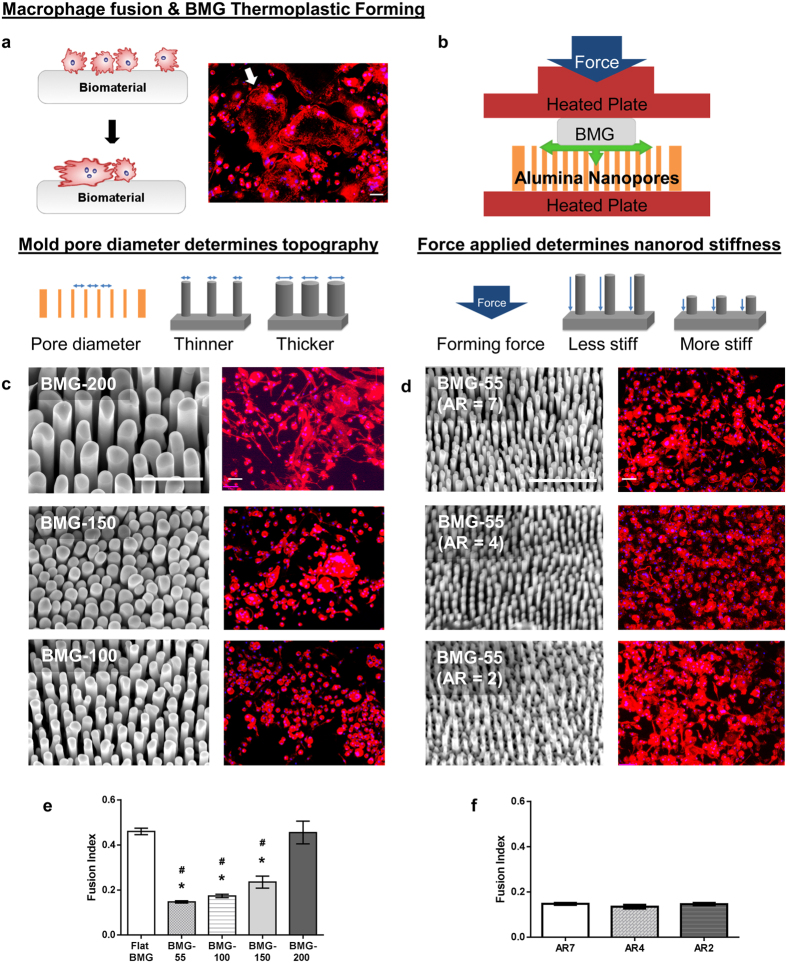

In the present study, cell-cell fusion of primary bone-marrow derived macrophages cultured on Pt-BMG nanorod arrays (Supplementary Fig. S1) was biochemically induced using IL-4. Macrophages on flat control BMGs displayed extensive fusion, forming large multinucleated FBGCs that accounted for 42% of all the nuclei (Fig. 1a). Cell fusion on BMG nanorod arrays was compromised to various extents depending on surface topography (Fig. 1c–e). Moreover, analysis of changes in cell adhesion density induced by nanorod arrays revealed that the decrease in cell-cell fusion observed was not correlated to reduced cell adhesion. For example, the average number of total nuclei on 55 nm nanorod arrays and 100 nm nanorod arrays was similar to that on Flat BMGs (Supplementary Fig. S1). Despite similar adhesion density, cell-cell fusion was reduced on these nanorod arrays. All nanorod arrays tested displayed a significant reduction in FBGC size as well as average number of nuclei per FBGC (Supplementary Fig. S1). 55 nm nanorod arrays, termed BMG-55s, were the most effective in attenuating cell-cell fusion and were chosen for further experimentation (Fig. 1c–e, Supplementary Fig. S1). To assess the effect of nanorod stiffness in isolation, BMG-55s with varying nanorod lengths were fabricated. Forming pressure was altered to increase the filling depth, which increases aspect ratio and hence generates nanorod arrays with similar topography (diameters and pitch), but varied aspect ratios and stiffness. A nanorod aspect ratio of seven for BMG-55s was used, which results in a stiffness of 3 nN/nm. In addition, BMG-55s with an average nanorod aspect ratio of 4 and 2 were generated with nanorod stiffness of 14 nN/nm and 114 nN/nm respectively (Supplementary Fig. S2). The average nanorod diameter for BMG-55s with different aspect ratios was 64 ± 10 nm. Hence, BMG-55s with varying aspect ratios represented nanorod arrays with identical diameters and pitch (topographical features) but a 40-fold difference in nanorod stiffness. Primary macrophages were seeded on BMG-55s and cell fusion was analyzed, which revealed that change in nanorod stiffness does not significantly alter macrophage fusion (Fig 1d,f). Taken together, these results imply that nanorod arrays with similar topographical cues (nanorod diameter and pitch) can override biochemical signals, independent of changes in nanorod stiffness cues, to regulate cell fusion (Fig. 1c–f).

Figure 1. Macrophage fusion on BMG nanorod arrays: Isolating the role of topography vs. stiffness in modulating macrophage behavior.

(a) (Left) Schematic of the macrophage fusion. Macrophages can fuse to form FBGCs on the biomaterial surface. (Right) IL-4 treated macrophages cultured on flat BMGs for 10 days fuse to form FBGCs. Cells stained for F-actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). White arrow indicates a single FBGC in the image. Scale bar = 70 μm. (b) Schematic of formation of nanorods by thermoplastic forming of BMGs using nanoporous alumina molds. Porosity of alumina molds determines nanorod diameter while force applied determines nanorod height. (c) (Left) Representative SEM images of nanopatterned BMGs. (BMG-55s, BMG-100s, BMG-150s and BMG-200s refer to nanopatterned BMGs with nominal nanorod diameter of 55, 100, 150 & 200 nm, Supplementary Fig. S1) Scale bar = 1 μm. (Right) IL-4 treated macrophages cultured on BMGs for 10 days, stained for F-actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). Scale bar = 70 μm. (d) (Left) Representative SEM images of BMG-55s with varying nanorod aspect ratios and therefore different stiffness. Scale bar = 1 μm. (Right) IL-4 treated macrophages on BMGs cultured for 10 days, stained for F-actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). Scale bar = 70 μm. (e,f) Fusion index (FI) of macrophages on flat and nanopatterned BMGs. FI was defined as the ratio of number of fused nuclei to total nuclei and was quantified in ImageJ. *represents significant differences as compared to flat BMGs. #represents significant differences as compared to BMG-200s. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). (ANOVA with Tukey’s posthoc analysis, (n ≥ 3). p ≤ 0.05 for significance.) Nanorods 55 nm in diameter significantly decreased fusion while changes in aspect ratio did not.

Our results reveal that some macrophage responses to nanotopography occur independent of substrate stiffness. It is also reported in the literature that cell fusion is unique in that it responds to changes in topography, but not stiffness18,42. Other cell types respond to changes in substrate stiffness by altering their morphologies and functions42,43. For example, fibroblasts respond to decreasing substrate stiffness by assuming a more rounded morphology and reducing collagen production37,43. An explanation for the differences between macrophages and other cell types may be found in the distinct nature of cell-substrate adhesions formed by these cells. Fibroblasts form stable focal adhesions, which anchor the cells to the underlying substrate37,44. In contrast, stable focal adhesions are missing in macrophages, which use short adhesions and podosomes to interact with the substrate45,46. Furthermore, it is important to note that in addition to topography and stiffness, nanomaterial shape constitutes a consequential biomechanical property. Specifically, it has been previously reported that ridges or trenches increase cell fusion29,30. Our results show that nanorod arrays can attenuate macrophage fusion. In this regard, their response is similar to that observed in other inflammatory cells interacting with nanofibers and nanoparticles and is dependent on nanomaterial shape5,47,48,49,50,51.

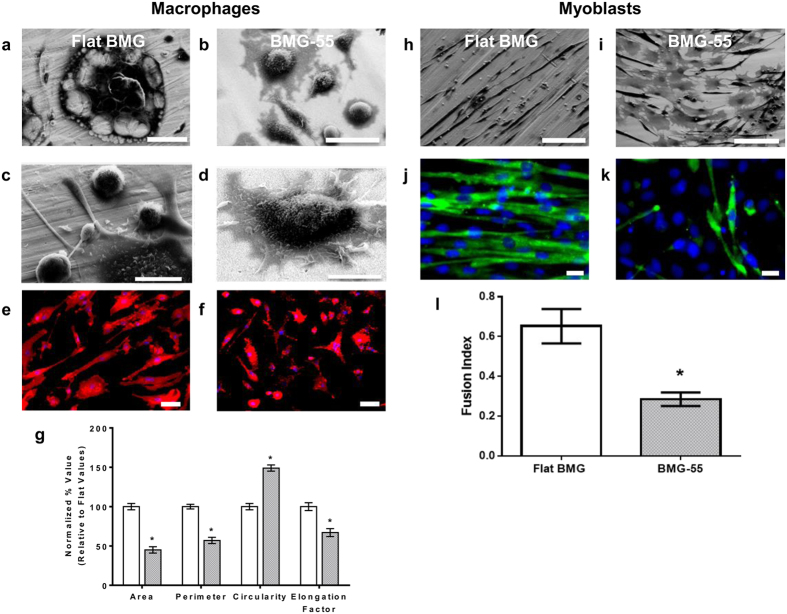

Nanotopography-induced attenuation of cytoskeletal remodeling results in reduced fusion

We observed that nanotopography-induced attenuation of cell fusion was correlated with reduced cytoskeletal remodeling. To probe nanotopography-induced changes in this process, we analyzed the differences in serum protein deposition on flat BMGs and BMG-55s (Supplementary Fig. S3). Atomic force microcopy (AFM) aided analysis of flat BMGs and nanopatterned BMGs prior to and following exposure to 10% serum-containing media suggested differences in protein deposition. Specifically, percent change in surface roughness following treatment was 45% for flat BMGs and 177% for BMG-55s (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, SEM analysis of macrophages revealed extensive fusion and formation of FBGCs. FBGCs formed extensions that interacted with individual macrophages, which is consistent with previous reports of macrophage fusion on other surfaces52,53 (Fig. 2a,c). In contrast, SEM of BMG-55s showed predominantly single cells, which demonstrated a distinct morphology with a raised cell center as shown in (Fig. 2b,d). We also observed the distinct change in cell spreading and elongation induced by nanotopography as early as 48 hours after culture with IL-4 using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2e,f). Cells on flat BMGs were found to be significantly larger and elongated as compared to cells on BMG-55s, suggesting that cytoskeletal remodeling is compromised in cells cultured on the latter (Fig. 2e–g).

Figure 2. Nanotopography-induced restriction in cytoskeletal remodeling results in decreased cell fusion.

(a–d) Representative SEM images of IL-4 treated macrophages on flat BMG and BMG-55 cultured for 10 days. Scale bar for a = 100 μm, b = 50 μm. c, d = 20 μm. (e,f) Representative images of IL-4 treated macrophages on flat BMGs and BMG-55s at Day 2 timepoint, stained for F-actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). Scale bar = 21 μm. (g) Quantification of parameters of macrophage morphology on flat (white) and BMG-55 (gray) samples. Cells on flat BMGs display an elongated, well-spread morphology, while cells on BMG-55s show significantly lower cell area and elongation. (h,i) Representative SEM images of transferrin/insulin treated myoblasts on flat BMGs and BMG-55s. Scale bars = 100 μm. (j,k) Transferrin/insulin-treated myoblasts cultured on BMGs for 72 hours in fusogenic media were fixed and stained for myosin heavy chain (MHC, green), which serves as a myoblast fusion marker62,63, and nuclei (blue). (l) Quantification of fusion index of myoblasts on flat BMGs and BMG-55s. Myoblasts on BMG-55s displayed significantly lower fusion index. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM).*p ≤ 0.05 for significance, t-test, compared to corresponding values in flat BMG controls.

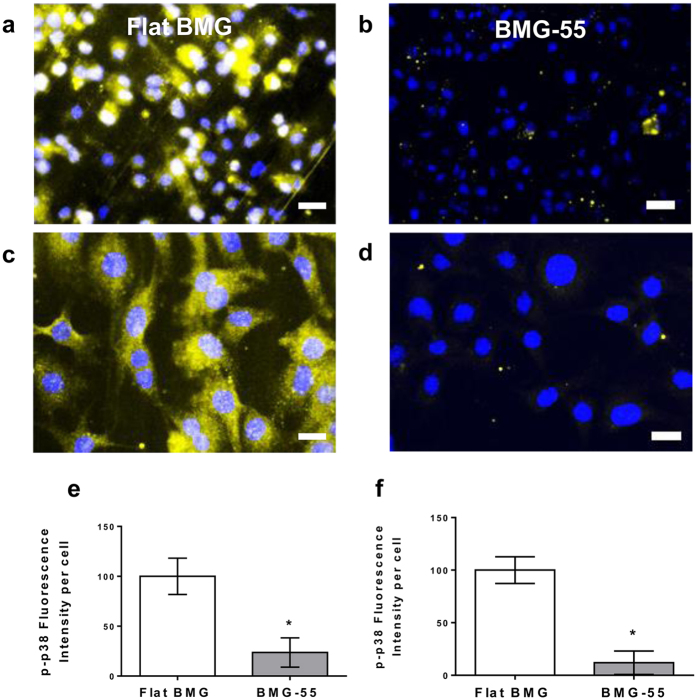

To further verify nanotopography-induced restriction of cytoskeletal remodeling, we investigated fusion of C2C12 myoblasts, which are fusogenic muscle progenitor cells10,11. BMG nanorod arrays induced a 50% reduction in myoblast fusion, which was similar to that observed for macrophages (Fig. 2h–l). In addition, SEM analysis revealed that cells on flat BMGs underwent extensive remodeling to form myotubes (Fig. 2h). In contrast, cells cultured on nanorod arrays showed minimal remodeling and were mostly individual cells (Fig. 2i). Based on our findings and published studies, we hypothesized that early activation of p38 MAP kinase might be involved in nanorod array-induced attenuation of cell fusion. Specifically, myogenesis was shown to require activation of p38 MAP Kinase and cells deficient in certain p38 isoforms displayed attenuated fusion capacity54,55,56. p38 MAP Kinase is also involved in the regulation of molecules such as P2×7, which regulate cytoskeletal remodeling in macrophage fusion57. Both macrophages (Fig. 3a,b,e) and myoblasts (Fig. 3c,d,f) cultured on BMG-55s with fusogenic media had lower levels of phospho-p38 as compared to flat BMGs. Collectively, our results indicate that nanotopography prevents the activation of p38 MAP Kinase, which limits cytoskeletal remodeling in fusogenic cells. Since early cytoskeletal remodeling is essential for cell fusion, we conclude that nanorod array-induced restriction of cell spreading and remodeling contributes to the altered fusion. The mechanism suggests that topography-induced modulation of cell fusion could be realized for other fusogenic cell types.

Figure 3. Compromised activation of p38 MAP Kinase induced by nanotopography.

(a,b) Representative images of macrophages cultured on Flat BMGs and BMG-55s for one hour in IL-4 containing media and subsequently fixed and stained for p-p38 (yellow) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 21 μm. (c,d) Representative images of myoblasts cultured on Flat BMGs and BMG-55s for one hour with fusogenic media, fixed and stained for p-p38 (yellow) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 21 μm. (e) Quantification of total fluorescence intensity per cell of p-p38 in macrophages, expressed as a percentage of flat BMG value. Macrophages cultured on BMG-55s displayed significantly lower levels of p-p38. (f) Quantification of total fluorescence intensity per cell of p-p38 in myoblasts. Myoblasts cultured on BMG-55s displayed significantly lower levels of p-p38. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). *p ≤ 0.05 for significance, t-test, compared to corresponding values in flat BMG controls.

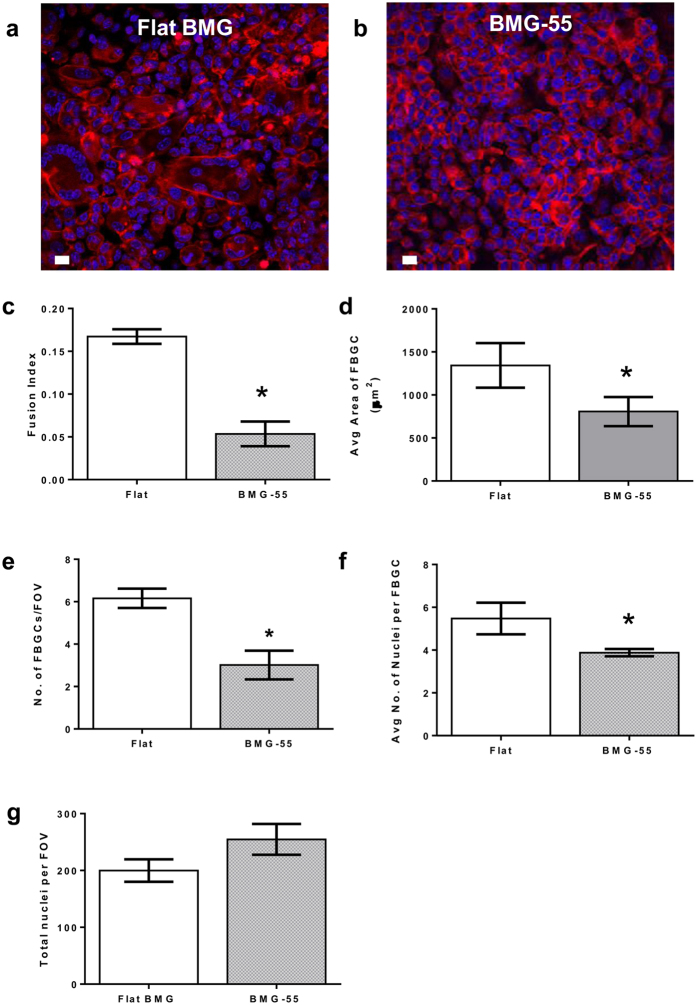

In vivo evaluation of nanotopography-induced attenuation of cell fusion

Furthermore, we evaluated nanotopography-mediated attenuation of FBR-associated cell fusion in vivo using an intraperitoneal (IP) FBGC formation model. Flat BMGs and BMG nanorod arrays were implanted in the intraperitoneal cavity of WT mice for 1 week. Explanted BMGs were stained and analyzed for cell fusion using confocal microscopy. Explanted BMG-55s had significantly lower number of FBGCs as compared to flat BMGs (Fig. 4a,b,e). Moreover, FBGCs on BMG-55s were smaller in size and had a smaller number of nuclei as compared to those on flat BMGs (Fig. 4a,b,d,f). Analysis revealed that 55 nm nanorod arrays attenuated FBR-associated cell fusion by over fifty percent (Fig. 4a–f).

Figure 4. In vivo evaluation of FBR-associated cell-cell fusion on BMG nanorod arrays.

Flat BMGs and BMG-55s were implanted IP in WT mice for 7 days. Explanted BMGs were stained and analyzed as described. (a,b) Explanted BMGs stained for F-actin (phalloidin) and nuclei (DAPI). Scale bar = 7 μm. (c–g) Quantification of fusion parameters. Fusion index was defined as the ratio of number of fused nuclei to total nuclei. BMG-55s resulted in attenuation of cell-cell fusion in in vivo settings. Fusion index, number of FBGCs, nuclei per FBGC and average area of FBGCs were significantly reduced on BMG-55s. Total number of nuclei per field of view was found to be larger on BMG-55s. (n = 6). Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). *p ≤ 0.05 for significance, t-test, compared to corresponding values in flat BMG controls.

Discussion

Work presented here expands our fundamental understanding of the nanoscale biophysical regulation of cell-cell fusion. We have demonstrated the selective mechanosensitivity of cell fusion to nanotopographical features. Substrate nanotopography can override biochemical signals, to attenuate fusion. Biochemical induction of fusion in primary macrophages and myoblasts is mediated by extensive cytoskeletal remodeling, which enables cell-cell contact and fusion. Substrate nanotopography restricts the signaling necessary for early cytoskeletal remodeling in cells, thereby decreasing overall fusion in both cell types. Nanotopographical cues presented by ECM architecture are ubiquitous in nature and hence could be involved in regulation of cell fusion in other relevant cell types. Implications of nanotopography-mediated changes in cell fusion in physiology and disease progression remain to be evaluated.

Nevertheless, our current findings have implications in several areas of research because cell-cell fusion underlies cell-biomaterial interactions. Specifically, sensitivity of macrophage fusion to nanotopography can be exploited to attenuate biomaterial-induced FBR. As described before, progression of FBR is largely mediated by activated macrophages, which fuse on the surface of biomaterials to form FBGCs9. Macrophages and FBGCs release degradative factors such as ROS and pro-fibrotic signals9,58. Prolonged presence of these cells leads to infiltration by collagen-producing fibroblasts. The consequence of these events is the formation of a collagen-rich capsule, which isolates the biomaterial from its microenvironment. In vitro assays and in vivo experiments described here showed that 55 nm nanorod arrays attenuated macrophage fusion and formation of FBGCs. Incorporation of nanoscale architecture on the surface of biomaterials provides a unique means to limit FBR-associated cell-cell fusion, which could lead to improved biomaterial-tissue integration and performance. Hence, nanotopography-mediated attenuation of macrophage fusion can mitigate or delay biomaterial rejection and implant failure. We have previously shown that 55 nm nanorod arrays can induce decreased collagen production in fibroblasts37. Thus, 55 nm nanorod arrays can induce favorable cell responses in both macrophages and fibroblasts. Such nanorod arrays can be incorporated in biomaterial surface design to limit FBR towards tissue engineering constructs, biomedical devices and implants.

Methods

Primary Macrophage Isolation

Mouse macrophages were obtained as described previously7. Briefly, bone marrow was collected from mouse femurs. The mononuclear cell component was isolated using Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane Labs, Burlington, NC) as described previously7. Cells were plated in expansion medium (IMDM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin, 1.5 ng/ml M-CSF, and 100 ng/ml Flt3-ligand, fed on day 5 and collected on day 10 by scraping as described previously7.

Fabrication of BMG nanorod arrays

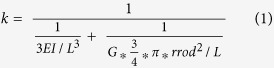

Thermoplastic forming of BMGs was employed to form nanorod arrays with nanoporous alumina molds as described previously35,37,59,60. BMG nanorod arrays with diameters ranging from 55–200 nm were formed using commercially available (Whatman & Synkera) nanoporous alumina molds fabricated through a two-step anodization process. Additionally, three different BMG-55s were pressed with distinct applied force during the forming process. 35 kN, 15 kN and 5 kN were used to create BMG-55s with varying nanorod stiffness of 3 nN/nm, 14 nN/nm and 114 nN/nm respectively. Nanorod stiffness was calculated using Timoshenko’s beam theory. The beam theory describes the stiffness of each nanorod (k) as a function of nanorod length (L), nanorod radius (rrod), second moment of inertia of the nanorod (I), elastic modulus of the material (E) as well as the shear modulus of the material (G), and is given by Euler-Bernoulli’s beam theory as follows.

|

SEM was employed to inspect the samples for fidelity before use. Representative BMG samples were placed in endotoxin-free PBS for 1 week and the eluents were analyzed for endotoxin content with the Pyrogent Plus, 64 kit (Lonza, Allendale, NJ). All samples contained less than 0.06 EU/ml.

In Vitro Macrophage Fusion & Analysis

Bone marrow-derived macrophages, were plated at a density of 260,000 cells/cm2 on ethanol-sterilized BMGs for 10 days in IMDM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, and 10 ng/ml IL-4. Media was replaced on Day 3, 5 and 7. At the end of 10 days, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with phalloidin and DAPI. Three/four independent samples were used for each type of BMG and at least ten images were analyzed for each sample. Image J was used for image analysis. For SEM samples, macrophages on BMGs were dehydrated using HMDS and serial ethanol washes followed by chrome-coating.

In Vitro Myoblast Fusion

C2C12 myoblasts at a density of 20,000 cells/cm2 were cultured in media (DMEM with 10% serum, 1% Penicillin/streptomycin and 1% sodium pyruvate) on BMGs for 24 hours followed by change of media to include differentiation factors. DMEM with 1% heat-inactivated FBS, 5 μg/ml transferrin and 5 μg/ml insulin was used to induce cell-cell fusion as described previously11. Passages 1–3 after thawing out vials of C2C12 myoblast cell line were used.

At the end of 72 hours, cells were prepped either for SEM or for immunostaining with MHC, which is a myoblast fusion marker11. For staining, fixed cells were permeabilized using Triton and 5% normal goat serum/0.3% Triton was used for blocking. Cells were stained with an antibody against MHC (DHSB, MF20) and subsequently with an Alexa-488 secondary antibody for imaging. Three independent samples were used for each type of BMG and at least ten images were analyzed for each sample using Image J.

Phospho-P38 in Macrophages And Myoblasts

Cells were seeded on BMGs and fixed using paraformaldehyde after 1 hour of culture with differentiation media. Primary Macrophages were seeded at a density of 260,000 cells/cm2 and C2C12s (passage 1–3) were cultured at a density of 20,000 cells/cm2. Fixed cells were stained for an antibody against phospho-p38 (Cell signaling, mAb #4631). A 488 nm fluorescent-tagged secondary antibody was used to visualize the protein and DAPI was used to label the nuclei. Three independent samples were used for each type of BMG & cell type and at least ten images were analyzed for each sample. Metamorph image analysis software was used to quantify fluorescence signal intensity normalized to number of nuclei. The fluorescence signal was converted to yellow to increase figure clarity.

AFM analysis of BMGs

BMG samples were washed with ethanol for sterilization, rinsed with PBS and subsequently incubated in serum-containing media for three hours. BMGs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and visualized using a Bruker AFM. For controls, flat BMGs and BMG-55s were analyzed after ethanol sterilization and rinsing with PBS.

In Vivo Cell Fusion & Analysis

All procedures were performed in accordance with the regulations adopted by the National Institutes of Health and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University. Intraperitoneal implantations were performed as described previously7. A total of 12 wild-type (WT) mice were used for the in vivo studies. Each mouse received a single BMG implanted in the peritoneum. Six independent samples were used for control flat BMGs and BMG-55s. BMGs remained in the peritoneum for 7 days prior to explantation. As described previously, intraperitoneal implants do not adhere to the omentum and can be easily retrieved and analyzed by staining61. Samples were then fixed and stained for image analysis. n = 6 mice were used for each BMG and at least ten images were analyzed for each sample.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Padmanabhan, J. et al. Regulation of cell-cell fusion by nanotopography. Sci. Rep. 6, 33277; doi: 10.1038/srep33277 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by CRISP (NSF MRSEC DMR 1119826). Funds from National Institutes of Health Grant (GM-072194) supported animal studies. Funding for Dr. A. Sawyer was provided by NIH Vascular Research Training Grant (5T32HL007950-12, A.S.). Yale Center for research on interface structures and phenomena (CRISP) and Yale Institute for Nanoscience and Quantum Engineering (YINQE) provided the facilities used for this research. We would also like to thank Dr. A. Bennet for providing C2C12 Myoblasts and Dr. L.B Moore, Sam Caldwell, and Zheng Chen for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions J.P. carried out most biological experiments. M.A., B.Ch., B.Cl., P.K. and R.W. contributed to biological experiments and data analysis. E.R.K. fabricated BMG samples and carried out SEM analysis. A.S. and J.P. carried out in vivo experiments. R.L. and U.S. carried out AFM experiments and contributed to data analysis. T.R.K. and J.S. designed the experiments and provided guidance. All authors contributed to data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Ogle B. M., Cascalho M. & Platt J. L. Biological implications of cell fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6, 567–575 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren-Suissa M. & Podbilewicz B. Cell fusion during development. Trends Cell Biol 17, 537–546 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelek J. M. & Chakraborty A. K. Fusion of tumour cells with bone marrow-derived cells: a unifying explanation for metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 8, 377–386 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. Zwitterionic hydrogels implanted in mice resist the foreign-body reaction. Nature biotechnology 31, 553–556 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan J. & Kyriakides T. R. Nanomaterials, inflammation, and tissue engineering. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 7, 355–370 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLauchlan S. et al. Macrophage fusion, giant cell formation, and the foreign body response require matrix metalloproteinase 9. Journal of leukocyte biology 85, 617–626 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L. B., Sawyer A. J., Charokopos A., Skokos E. A. & Kyriakides T. R. Loss of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 alters macrophage polarization and reduces NF kappa B activation in the foreign body response. Acta Biomater 11, 37–47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay S. M., Skokos E. A., Zeng J., Knox K. & Kyriakides T. R. Macrophage fusion leading to foreign body giant cell formation persists under phagocytic stimulation by microspheres in vitro and in vivo in mouse models. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 93, 189–199 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. M., Rodriguez A. & Chang D. T. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Seminars in immunology 20, 86–100 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. et al. Improved regenerative myogenesis and muscular dystrophy in mice lacking Mkp5. J Clin Invest 123, 2064–2077 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaridis M. I., Liu X., Zhang L. & Bennett A. M. SHP-2 complex formation with the SHP-2 substrate-1 during C2C12 myogenesis. J Cell Sci 114, 2187–2198 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajcini K. V., Pomerantz J. H., Alkan O., Doyonnas R. & Blau H. M. Myoblasts and macrophages share molecular components that contribute to cell-cell fusion. The Journal of cell biology 180, 1005–1019 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay S. M., Skokos E., Laiwalla F., Krady M. M. & Kyriakides T. R. Foreign body giant cell formation is preceded by lamellipodia formation and can be attenuated by inhibition of Rac1 activation. The American journal of pathology 171, 632–640 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner S., Gross S. M., David L. L., Klimek J. E. & Rotwein P. Separating myoblast differentiation from muscle cell fusion using IGF-I and the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB202190. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, ajpcell 00184 02015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt D. J. & Grainger D. W. Multinucleated giant cells from fibroblast cultures. Biomaterials 32, 3977–3987 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. M., Roos D. S., Davidson R. L. & Karnovsky M. J. Membrane alterations and other morphological features associated with polyethylene glycol-induced cell fusion. J Cell Sci 40, 63–75 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz B. R. & Lee J. K. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-mediated fusion between pure lipid bilayers: a mechanism in common with viral fusion and secretory vesicle release? Mol Membr Biol 16, 279–296 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M. M. & George J. H. Exploring and engineering the cell surface interface. Science 310, 1135–1138 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. L. et al. Cells lying on a bed of microneedles: an approach to isolate mechanical force. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 1484–1489 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien J., Nelson C. M. & Chen C. S. Fabrication of aligned microstructures with a single elastomeric stamp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 1758–1762 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby M. J., Pasqui D. & Affrossman S. Cell response to nano-islands produced by polymer demixing: a brief review. IEE Proc Nanobiotechnol 151, 53–61 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray R. J. et al. Nanoscale surfaces for the long-term maintenance of mesenchymal stem cell phenotype and multipotency. Nat Mater 10, 637–644 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim E. K., Darling E. M., Kulangara K., Guilak F. & Leong K. W. Nanotopography-induced changes in focal adhesions, cytoskeletal organization, and mechanical properties of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 31, 1299–1306 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs M. J. et al. Interactions with nanoscale topography: adhesion quantification and signal transduction in cells of osteogenic and multipotent lineage. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 91, 195–208 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham C. J., ter Maat J. & de Vos W. M. Where bio meets nano: the many uses for nanoporous aluminum oxide in biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv 30, 1089–1099 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby M. J. et al. Increasing fibroblast response to materials using nanotopography: morphological and genetic measurements of cell response to 13-nm-high polymer demixed islands. Exp Cell Res 276, 1–9 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H., Simon C. G. Jr. & Kim G. A mini-review: Cell response to microscale, nanoscale, and hierarchical patterning of surface structure. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part B, Applied biomaterials 102, 1580–1594 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. S. et al. Electroconductive Nanopatterned Substrates for Enhanced Myogenic Differentiation and Maturation. Adv Healthc Mater 5, 137–145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini V. et al. Engineered contractile skeletal muscle tissue on a microgrooved methacrylated gelatin substrate. Tissue engineering. Part A 18, 2453–2465 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. et al. Characterization of topographical effects on macrophage behavior in a foreign body response model. Biomaterials 31, 3479–3491 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers E. et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the inflammatory response to nanoscale grooved substrates. Nanomedicine 8, 308–317 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsu P. et al. Reduced inflammatory activity of RAW 264.7 macrophages on titania nanotube modified Ti surface. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 55, 187–195 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majd H. et al. Novel micropatterns mechanically control fibrotic reactions at the surface of silicone implants. Biomaterials 54, 136–147 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. F. & Zheng Y. F. Recent advances in bulk metallic glasses for biomedical applications. Acta Biomater 36, 1–20 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar G., Tang H. X. & Schroers J. Nanomoulding with amorphous metals. Nature 457, 868–872 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroers J., Kumar G., Hodges T. M., Chan S. & Kyriakides T. R. Bulk metallic glasses for biomedical applications. Jom-Us 61, 21–29 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan J. et al. Engineering cellular response using nanopatterned bulk metallic glass. ACS nano 8, 4366–4375 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Zhang T., Liaw P. K. & He W. Macrophage responses to a Zr-based bulk metallic glass. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 102, 3369–3378 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. et al. Ni-free Zr-Cu-Al-Nb-Pd bulk metallic glasses with different Zr/Cu ratios for biomedical applications. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 100, 1472–1482 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroers J. et al. Thermoplastic blow molding of metals. Mater Today 14, 14–19 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ding S. et al. Combinatorial development of Metallic Glasses. Nature Materials 13, 494 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher D. E., Janmey P. & Wang Y. L. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science 310, 1139–1143 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam K. R. et al. The effect of nanotopography on modulating protein adsorption and the fibrotic response. Tissue engineering. Part A 20, 130–138 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco da Cunha C. et al. Influence of the stiffness of three-dimensional alginate/collagen-I interpenetrating networks on fibroblast biology. Biomaterials 35, 8927–8936 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixley F. J. Macrophage Migration and Its Regulation by CSF-1. Int J Cell Biol 2012, 501962 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. G., Correia I., Krasavina O., Watson N. & Matsudaira P. Macrophage podosomes assemble at the leading lamella by growth and fragmentation. J Cell Biol 161, 697–705 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashur C. A., Shaffer R. D., Dahlgren L. A., Guelcher S. A. & Goldstein A. S. Effect of fiber diameter and alignment of electrospun polyurethane meshes on mesenchymal progenitor cells. Tissue engineering. Part A 15, 2435–2445 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J. et al. Radially aligned, electrospun nanofibers as dural substitutes for wound closure and tissue regeneration applications. ACS nano 4, 5027–5036 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinwald A., Chernova T. & Donaldson K. Use of silver nanowires to determine thresholds for fibre length-dependent pulmonary inflammation and inhibition of macrophage migration in vitro. Part Fibre Toxicol 9, 47 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., McHugh K., Chew S. Y. & Anderson J. M. The topographical effect of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds on the in vivo and in vitro foreign body reaction. Journal of biomedical materials research. Part A 93, 1151–1159 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albanese A., Tang P. S. & Chan W. C. The effect of nanoparticle size, shape, and surface chemistry on biological systems. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 14, 1–16 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally A. K. & Anderson J. M. Beta1 and beta2 integrins mediate adhesion during macrophage fusion and multinucleated foreign body giant cell formation. The American journal of pathology 160, 621–630 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally A. K., Macewan S. R. & Anderson J. M. Foreign body-type multinucleated giant cell formation requires protein kinase C beta, delta, and zeta. Exp Mol Pathol 84, 37–45 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdiguero E. et al. Genetic analysis of p38 MAP kinases in myogenesis: fundamental role of p38alpha in abrogating myoblast proliferation. EMBO J 26, 1245–1256 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. et al. p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate the myogenic program at multiple steps. Molecular and cellular biology 20, 3951–3964 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S., Kumar A., Makonchuk D. Y., Li H. & Kumar A. Transforming growth factor-beta-activated kinase 1 is an essential regulator of myogenic differentiation. The Journal of biological chemistry 285, 6401–6411 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer Z. A. et al. The nucleotide receptor P2X7 mediates actin reorganization and membrane blebbing in RAW 264.7 macrophages via p38 MAP kinase and Rho. Journal of leukocyte biology 75, 1173–1182 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Harkel B. et al. The Foreign Body Giant Cell Cannot Resorb Bone, But Dissolves Hydroxyapatite Like Osteoclasts. PloS one 10, e0139564 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo M. et al. Bulk metallic glass nanowire architecture for electrochemical applications. ACS nano 5, 2979–2983 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. et al. Tunable Hierarchical Metallic-Glass Nanostructures. Adv Funct Mater 23, 2708–2713 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Moore L. B., Sawyer A. J., Saucier-Sawyer J., Saltzman W. M. & Kyriakides T. R. Nanoparticle delivery of miR-223 to attenuate macrophage fusion. Biomaterials 89, 127–135 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornaro M. et al. SHP-2 activates signaling of the nuclear factor of activated T cells to promote skeletal muscle growth. The Journal of cell biology 175, 87–97 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovidov S. et al. Three-dimensional co-culture of C2C12/PC12 cells improves skeletal muscle tissue formation and function. J Tissue Eng Regen Med (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.