Significance

Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) is a critical protein with many protective activities inside the cell. We demonstrate that forced secretion of Hsp70 is beneficial against the extracellular protein aggregates typical of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Engineering Hsp70 enables its interaction with the amyloid-β42 peptide, the main pathogenic agent in AD. This interaction suppresses amyloid-β toxicity in the eye, reduces cell death in brain neurons, and protects neuronal architecture and function. Interestingly, secreted Hsp70 exerts this protective activity without utilizing its refolding activity and without decreasing the levels and aggregation of amyloid-β42. These results suggest a protective mechanism mediated by direct binding to amyloid-β42, which blocks amyloid-β42 neurotoxicity. We discuss here the potential therapeutic benefits of secreted Hsp70.

Keywords: amyloid-β, Hsp70, Drosophila, engineered chaperones, neuroprotections

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent of a large group of related proteinopathies for which there is currently no cure. Here, we used Drosophila to explore a strategy to block Aβ42 neurotoxicity through engineering of the Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), a chaperone that has demonstrated neuroprotective activity against several intracellular amyloids. To target its protective activity against extracellular Aβ42, we added a signal peptide to Hsp70. This secreted form of Hsp70 (secHsp70) suppresses Aβ42 neurotoxicity in adult eyes, reduces cell death, protects the structural integrity of adult neurons, alleviates locomotor dysfunction, and extends lifespan. SecHsp70 binding to Aβ42 through its holdase domain is neuroprotective, but its ATPase activity is not required in the extracellular space. Thus, the holdase activity of secHsp70 masks Aβ42 neurotoxicity by promoting the accumulation of nontoxic aggregates. Combined with other approaches, this strategy may contribute to reduce the burden of AD and other extracellular proteinopathies.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the presence of amyloid-β1–42 (Aβ42) deposition in senile plaques, tau accumulation in neurofibrillary tangles, and neuronal loss coupled with cognitive decline and other behavioral alterations (1). Genetic evidence strongly supports a causal role for Aβ42 as the triggering event in AD (2). Although the initial amyloid cascade hypothesis posited that the accumulation of Aβ42 into insoluble amyloid fibers was the key triggering event, growing evidence indicates that soluble preamyloid structures are the main contributors to AD pathogenesis (3). These preamyloid structures include both oligomers with little β-sheet structure and protofibrils with a high β-sheet content. Indeed, in certain experimental systems, it can be shown that soluble Aβ42 assemblies are more potent toxins than the amyloid fibrils themselves (4, 5). However, the likely reality is that both soluble preamyloid and amyloid assemblies contribute to disease but perhaps in different ways. Thus, neutralizing the toxicity of different Aβ42 assemblies poses extraordinary challenges.

In addition to AD, self-association of misfolded proteins into toxic assemblies is the main pathological event in a large number of neurodegenerative diseases collectively known as protein misfolding disorders or proteinopathies (6). These intracellular protein aggregates led several teams to propose molecular chaperones as cellular machines with key roles regulating pathology. Early in vitro studies confirmed the regulatory role for chaperones in protein misfolding and aggregation (7–9). Then, N. Bonini’s group demonstrated that the Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), the main cytosolic chaperone in eukaryotes, suppressed the toxicity of Ataxin-3–78Q (Atx3) and mutant α-Synuclein in Drosophila (10, 11). Hsp70 proved later its neuroprotective activity in transgenic mice expressing mutant Atx1, Androgen receptor, and tau (12–14). These results suggest the therapeutic potential of Hsp70 activation (15, 16). Hsp70 is found in a variety of pathological protein aggregates within cells and demonstrates a notable ability to regulate proteotoxic assemblies (17). Remarkably, Hsp70 inhibits the early stages of Aβ42 misfolding in cell-free systems by dissociating preformed oligomers but not fibrils, suggesting that Hsp70 targets oligomeric intermediates (18). More recent in vitro studies show that Hsp70 and other chaperones promote the aggregation of oligomers into less toxic species (19). Also, Hsp70 demonstrates neuroprotection against intracellular Aβ42 in primary cultures (20), whereas down-regulation of Hsp70 leads to increased protein aggregation in transgenic worms expressing intracellular Aβ42 (21). A recent study in a transgenic mouse model of AD overexpressing the Amyloid precursor protein with the Swedish mutation (APPswe) showed that Hsp70 overexpression improved cognition and reduced Aβ42 levels, but this protective activity seemed to be indirectly mediated by elevated levels of insulin-degrading enzyme in glia (22). Overall, these observations suggest that Hsp70 exerts a robust protective activity against Aβ42 toxicity under experimental conditions that facilitate their interaction. Unfortunately, this interaction is precluded under physiological conditions because Hsp70 and Aβ42 occupy different subcellular compartments.

Drosophila has played an instrumental role in the identification of genetic and molecular mechanisms mediating the neurotoxicity of misfolded amyloids, with particular attention to AD (23, 24). A key advantage of Drosophila models is the ability to efficiently test candidate genes. Here, we engineered Hsp70 to force its secretion (secHsp70) into the extracellular space, where it could potentially interact with Aβ42. We report that secHsp70 suppresses Aβ42 neurotoxicity in the eye, reduces cell death in brain neurons, protects the structural integrity of mushroom body neurons, and suppresses the progressive dysfunction of locomotor neurons. We also find that secHsp70 interacts with Aβ42 in brain neurons but does not alter Aβ42 steady-state levels or aggregation. Interestingly, secHsp70 promotes the formation of Aβ42 aggregates in a cell-based assay that is reversed by addition of ATP, suggesting that the secHsp70 binding is critical to mask neurotoxic Aβ42 epitopes. Based on these results, we demonstrate that the ATPase activity of secHsp70 that mediates its foldase activity is not required for its protective activity. We also confirmed through mutations that disrupt the substrate-binding domain (SBD) of secHsp70 that the holdase activity of secHsp70 is sufficient to mask Aβ42 neurotoxic epitopes. These studies report a potent mechanism for blocking Aβ42 neurotoxicity.

Results

Generation of SecHsp70.

To force Hsp70 secretion, we analyzed virtual fused human Hsp70 (HSPA1L) (10) with the signal peptide of the human Ig heavy chain V-III, which is compatible with Drosophila and mammals and displayed a perfect match with the Von Heijne consensus and ref. 25. We synthesized the signal peptide–HSPA1L fusion (secHsp70) and placed the fusion under the control of the yeast UAS regulatory sequence (26). To examine the functionality of the signal peptide in Drosophila, we cotransfected Hsp70 or secHsp70 with Actin-Gal4 into Drosophila S2R+ cells. As expected, Hsp70 accumulated throughout the cytoplasm and did not colocalize with the ER-bound Hsc3/BiP (Fig. 1A). In contrast, secHsp70 distribution overlapped with that of Hsc3, supporting the synthesis of Hsp70 in the secretory pathway (Fig. 1A). To verify secHsp70 secretion, we collected the media from the transfected cells, precipitated the proteins, and performed Western blot. We detected secHsp70, but not Hsp70, in the culture media, demonstrating its efficient secretion into the extracellular space (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

SecHsp70 is efficiently secreted in Drosophila cells and tissues. (A) Expression of Hsp70 and secHsp70 in Drosophila S2R+ cells. Hsp70 (magenta) accumulates in the cytoplasm, whereas secHsp70 colocalizes with Hsc3 (green) in the ER (arrow). DAPI (white) labels the nuclei. (B) SecHsp70, but not Hsp70, is detected in the culture media. Purified Hsp70 was loaded in the second lane as a positive control. (C–F) Distribution of Hsp70 in the eye–antenna disk. (C and D) Hsp70 (green) accumulates in the posterior differentiating photoreceptors that express Elav (magenta, arrowhead). (E and F) SecHsp70 accumulates throughout the entire eye–antenna disk (arrow), whereas Elav is still restricted to the posterior eye (arrowhead). SecHsp70 accumulates in the lumen of the disk (F, arrow), supporting its secretion from the posterior eye cells.

In Vivo Distribution of secHsp70.

We next created transgenic flies carrying secHsp70 and compared the distribution of Hsp70 and secHsp70 in the larval eye imaginal disk. As expected, Hsp70 distribution was restricted to the posterior eye disk in cells undergoing differentiation into the mature retina (Fig. 1 C and D). Although only posterior eye cells expressed secHsp70 (Fig. 1 E and F, arrowhead), secHsp70 accumulated throughout the whole antenna–eye imaginal disk, diffusing into the lumen of the anterior eye and the antenna (Fig. 1 E and F, arrow). Thus, secHsp70 was processed and secreted as predicted in vivo, enabling us to test its functional interaction with extracellular Aβ42.

SecHsp70 Suppresses Aβ42 Neurotoxicity in the Eye.

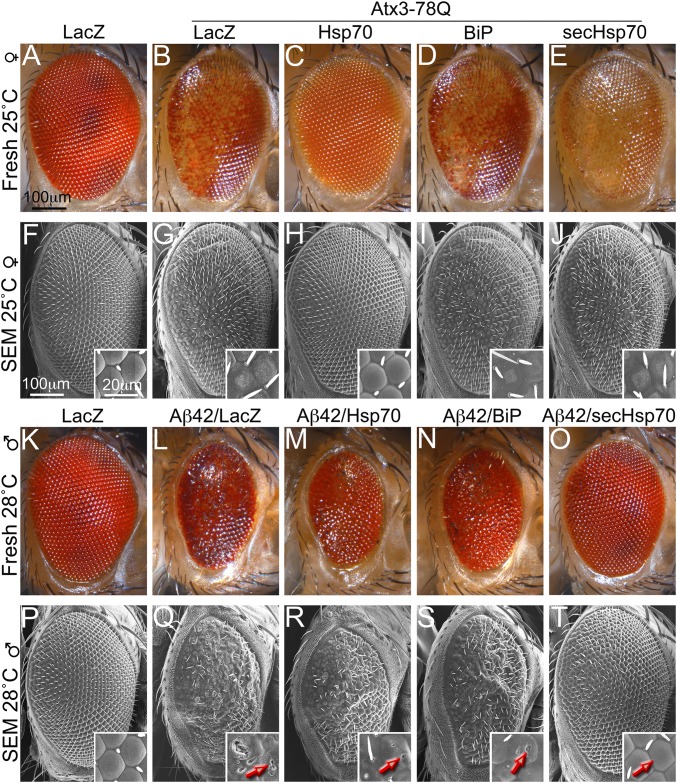

To examine the compartment-specific activity of Hsp70 and secHsp70, we first coexpressed Hsp70 in different compartments with Atx3-78Q, a cytosolic/nuclear amyloid (27). Compared with control flies expressing LacZ alone (Fig. 2 A and F), flies coexpressing Atx3-78Q with LacZ exhibited glassy and depigmented eyes with abnormal lenses (Fig. 2 B and G). As described previously, Hsp70 completely suppressed the Atx3-78Q eye phenotypes (Fig. 2 C and H) (10), demonstrating its potent antiamyloid activity. However, neither ER-bound BiP nor secHsp70 modified the glassy and depigmented eye induced by Atx3-78Q (Fig. 2 D, E, I, and J). Flies coexpressing Atx3-78Q and a secreted GFP reporter (secGFP), a control for the artificial secretion of Hso70, exhibited the same eye phenotype as flies coexpressing LacZ (Fig. S1 A and B). Thus, BiP and secHsp70 are confined to the secretory compartment and do not leak into the cytosol based on the lack of suppression of the Atx3-78Q phenotype.

Fig. 2.

SecHsp70 suppresses Aβ42 neurotoxicity in the eye. (A–J) Fresh eyes and SEMs of Atx3-78Q females at 25 °C. Control flies expressing LacZ in the eye display a highly ordered ommatidia lattice (A and F). Coexpression of Atx3-78Q and LacZ results in depigmented eyes with poorly differentiated lenses (B and G). Coexpression of Atx3-78Q and Hsp70 completely suppresses Atx3-78Q neurotoxicity (C and H). Coexpression of Atx3-78Q with BiP (D and I) or secHsp70 (E and J) has no effect on Atx3-78Q phenotype. (K–T) Fresh eyes and SEM of Aβ42 males at 28 °C. (K and P) Control flies expressing LacZ in the eye. Coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ results in small, glassy, and depigmented eyes that accumulate necrotic spots that breach the lenses (arrow) (L and Q). Coexpression of Aβ42 with Hsp70 (M and R) or BiP (N and S) has no effect on the Aβ42 phenotype. Coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 results in eyes of normal size with almost perfect organization and no necrotic spots (O and T). Insets show a magnification of the ommatidia.

Fig. S1.

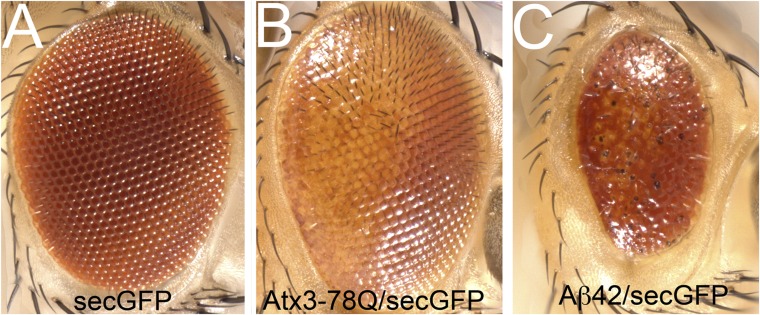

A secreted form of GFP has no effect on Aβ42 toxicity. (A and B) Expression of secGFP has no effect in the eye or on Atx3-78Q toxicity. Flies expressing a secreted form of EGFP in the eye under the control of GMR-Gal4 have perfectly organized eyes (A). Flies coexpressing Atx3-78Q and secGFP display the same bright and depigmented eye as flies coexpressing cytosolic LacZ (B). (C) Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secGFP have no effect on Aβ42 toxicity and exhibit the same small, disorganized, and depigmented eyes.

Next, we determined the ability of the different Hsp70 constructs to suppress the toxicity of the human Aβ42 peptide in the eye. Coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ dramatically reduced the size of the eye, disrupted the highly ordered lattice of the ommatidia (glassy eye), and caused depigmentation and accumulation of necrotic spots (Fig. 2 K and L) (28). Aβ42 also perturbed the differentiation of lenses, which appeared fused and ruptured (Fig. 2 P and Q). Coexpression of Aβ42 with Hsp70 or BiP had no effect on the eyes, which were still small and disorganized (Fig. 2 M and N) with fused and ruptured lenses (Fig. 2 R and S). In contrast, coexpression of Aβ42 with secHsp70 resulted in eyes of normal size with highly organized ommatidia, strong pigmentation, no necrotic spots (Fig. 2O), and well-differentiated lenses (Fig. 2T). Coexpression of Aβ42 with secGFP still had the same robust eye perturbations (Fig. S1C), demonstrating that coexpressing innocuous intra- or extracellular proteins had no effect on Aβ42 toxicity. Overall, these results support the robust protective activity of secHsp70 in the extracellular space, where Aβ42 exerts its toxicity, whereas the cytosol and the ER do not seem to alter Aβ42 toxicity.

SecHsp70 Nonautonomously Suppresses Aβ42 Eye Toxicity.

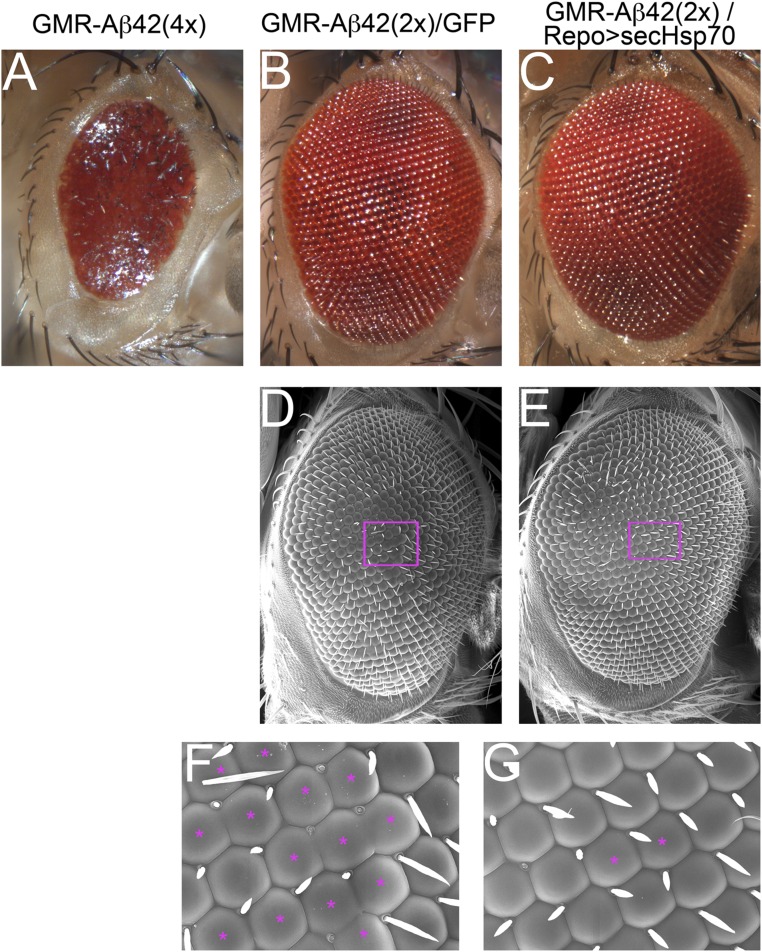

The previous experiments demonstrate that coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 in the same cells dramatically suppresses the toxicity of Aβ42. Although coexpression with BiP demonstrates that the ER is not the site of the protective activity of secHsp70, Aβ42 and secHsp70 could interact further downstream in the secretory pathway before both proteins are secreted. To test the ability of secHsp70 to rescue Aβ42 toxicity extracellularly, we expressed Aβ42 and secHsp70 in different cell types in the eye. For this, we expressed Aβ42 in all eye cells with the GMR-Aβ42(4×) fusion (29) and expressed secHsp70 in all glia using the repo-Gal4 driver. This experimental design allows us to express Aβ42 and secHsp70 in two distinct populations that only come into contact after the eye starts to differentiate. Although the GMR-Aβ42(4×) flies carrying four copies of the fusion construct show a robust eye phenotype (Fig. S2A), flies carrying GMR-Aβ42(2×) and UAS-GFP-attP display a weak phenotype consisting of multiple ommatidia fusions (Fig. S2 B, D, and F). However, flies carrying GMR-Aβ42(2×) with UAS-secHsp70;repo-Gal4 resulted in almost perfect eyes showing very few fusions (Fig. S2 C, E, and G). Overall, our results support the non-cell autonomous protective activity of secHsp70 driven from glia.

Fig. S2.

SecHsp70 nonautonomously suppresses Aβ42 toxicity. (A) Flies carrying four copies of the GMR-Aβ42(4×) construct display small and glassy eyes. (B, D, and F) Crossing GMR-Aβ42(4×) with UAS-GFPattP results in flies carrying two copies of GMR-Aβ42(2×) that display a weak eye phenotype (B). The eye phenotype is clearly visible in the SEM and consists on multiple ommatidia fusions (D and F). (C, E, and G) Flies carrying two copies of the GMR-Aβ42(2×) construct and expressing secHsp70 in glia under the control of repo-Gal4 show better organized eyes (C and E). The suppressed phenotype can be observed as rare ommatidia fusions (E and G).

SecHsp70 Is Neuroprotective in the Eye.

The robust eye phenotype in flies expressing Aβ42 is due, in part, to massive cell death that starts soon after the expression of Aβ42 (30). We next examined the ability of secHsp70 to suppress the Aβ42-induced cell death in the developing eye. For this, we used TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling), a technique that fluorescently labels broken DNA ends. Control eye discs expressing LacZ exhibited TUNEL staining in a row of cells in the posterior eye (Fig. 3 A, E, and I). These cells undergo developmentally regulated apoptosis after failing to acquire an identity in the differentiating eye. Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ accumulated three times more TUNEL-positive cells distributed throughout the posterior eye disk, illustrating the toxicity of Aβ42 (Fig. 3 B, F, and I). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 accumulated fewer TUNEL-positive cells, but the difference was not statistically significant with respect to Aβ42/LacZ controls (Fig. 3 C, G, and I). Finally, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 showed a significant reduction in the TUNEL-positive cells, although they still accumulated more than twice the number of dying cells than control eyes (Fig. 3 D, H, and I). These results demonstrate the neuroprotective activity of secHsp70 against Aβ42 during the early stages of eye differentiation.

Fig. 3.

SecHsp70 is neuroprotective against Aβ42. (A–H) TUNEL signal in the eye disk. Control eyes expressing LacZ accumulate TUNEL signal (green) in a row of cells posterior to the differentiation wave (A and E). Coexpression of Aβ42 (magenta) and LacZ increases TUNEL signal throughout the posterior eye (B and F). Coexpression of Aβ42 and Hsp70 lowers the TUNEL signal (C and G). Coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 significantly lowers fluorescence (D and H). (I) Quantification of TUNEL signal in eye discs. (J–N) TUNEL signal in mushroom body neurons in 20-d-old brains (J). Brains expressing LacZ accumulate no TUNEL signal in the Kenyon cells (Kcs) (K). Coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ induces widespread apoptosis through the Kc (L). Coexpression of Aβ42 and Hsp70 (M) or secHsp70 (N) reduces the number of TUNEL-positive cells in Kc. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

SecHsp70 Is Neuroprotective in Brain Neurons.

To further validate the neuroprotective activity of secHsp70, we performed TUNEL in adult brains expressing Aβ42 in the mushroom body neurons, the best characterized higher processing center in the Drosophila brain (31, 32). Around 2,500 Kenyon cells per hemisphere form tight clusters in the posterior brain (see Fig. 4A). Flies expressing LacZ and aged for 20 d accumulated no TUNEL signal in the Kenyon cell clusters (Fig. 3 J and K, arrow), indicating the robustness of these neurons. In contrast, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ accumulated around 20 apoptotic cells per cluster (Fig. 3 J and L, arrows). Interestingly, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 or secHsp70 exhibited a comparable reduction in the number of TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 3 J, M, and N, arrows). These results support the protective activity of secHsp70 in brain neurons and describe an unexpected protective activity for Hsp70.

Fig. 4.

SecHsp70 protects neuronal integrity in brain neurons. (A–D) 3D architecture of the mushroom body complex in 1-d-old flies by CD8-GFP expression. Control flies expressing LacZ exhibit robust dorsal (α) and medial (β and γ) lobes (A). The calyx (Ca) appears below in light blue and the cell bodies (Kenyon cells, Kc) in dark blue. The arrow indicates the antero–posterior (A–P) axis ages. Expression of Aβ42 shrinks the mushroom body lobes (B, arrows), which are not rescued by Hsp70 (C). SecHsp70 rescues the axonal terminals (D, arrows). (E–P) Single optical planes of the calyces at days 1, 20, and 40. At day 1, expression of Aβ42 enlarges the calyces compared with LacZ control flies (E–H). By day 20, coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ (J) shrinks the calyces (I). Coexpression of Hsp70 has no protective effect (K), but coexpression of secHsp70 preserves the calyces (L). By day 40, coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ drastically reduces the calyces (M and N). Hsp70 does not rescue calix degeneration (O), but coexpression of secHsp70 partially rescues calycal volume (P). (Q) Mushroom body lobe areas of day 1 flies. (R) Calycal volumes in flies at different time points. Values are shown as averages ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

SecHsp70 Protects the Structural Integrity of Brain Neurons.

We next investigated the ability of secHsp70 to protect the architecture of mushroom body neurons upon Aβ42 expression. The Kenyon cells project their dendrites—the calyces—into the underlying neuropil, where they receive input from several types of projection neurons (Fig. 4A). The axons project through the calyces toward the anterior brain, where they branch into dorsal (α) and medial (β, γ) lobes. Expression of LacZ alone did not alter the robust calyces and axonal lobes (Fig. 4A). However, coexpression of Aβ42 and LacZ ensued in thinner axonal lobes, illustrating the developmental toxicity of Aβ42 (Fig. 4 B and Q). Coexpression of Aβ42 and Hsp70 did not rescue the thin axons (Fig. 4 C and Q). In contrast, coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 partially rescued the mushroom body axonal lobes (Fig. 4 D and Q). Because Aβ42 disrupted the development of the axonal terminals, we focused only on the calyces for aging studies.

In contrast to the axonal terminals, the calyces seemed well preserved in young flies expressing Aβ42, thus making them a better model to study the progressive toxicity of Aβ42 (Fig. 4 E and R). The volume of calyces in control flies expressing LacZ expanded over time, showing a 30% increase by day 20 and a 50% increase by day 40 (Fig. 4 E, I, M, and R). This dendritic expansion is likely due to dendritic growth and remodeling, as there is no neuronal proliferation in adult flies. The calycal volume of 1-d-old flies expressing Aβ42 and LacZ were slightly larger, suggesting that Aβ42 stimulates the spread of the dendritic terminals (Fig. 4 F and R). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 or secHsp70 exhibited even larger calyces at day 1 than the flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ (Fig. 4 G, H, and R). These results support the protective activity of the secHsp70 and further suggest a positive role for Aβ42 in dendritic spreading.

By day 20, though, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ showed a 30% reduction in calycal volume compared with LacZ controls (Fig. 4 I, J, and R). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 experienced a similar reduction in dendritic volume as Aβ42/LacZ flies (Fig. 4 K and R). However, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 exhibited a calycal volume similar to that of LacZ controls and 20% larger than that of the Aβ42/LacZ flies (Fig. 4 L and R). Thus, at day 20 sHsp70 completely suppressed the degeneration of the calyces, but Hsp70 had no protective effect.

By day 40, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ experienced almost a 60% reduction in calycal volume compared with LacZ controls (Fig. 4 M, N, and R). Hsp70 provided no protection of the calyces by day 40, resulting in identical reduction in dendritic volume as Aβ42/LacZ flies (Fig. 4 O and R). In contrast, coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 partially suppressed the degeneration of the calyces, which were 45% smaller than in control LacZ flies but 25% larger than in Aβ42/LacZ flies (Fig. 4 P and R). Overall, these results support the protective activity of secHsp70 against the progressive neurotoxicity of Aβ42 in the dendritic terminals of the mushroom body neurons.

SecHsp70 Suppresses the Progressive Dysfunction Induced by Aβ42.

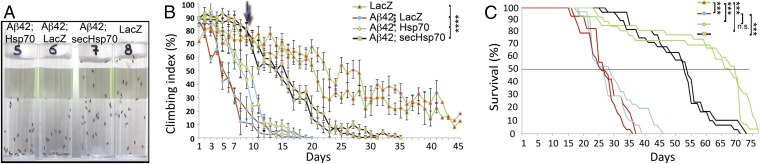

To determine the physiological benefits of the Hsp70 constructs, we next examined the locomotor performance of adult flies as a surrogate functional assay for Aβ42 toxicity. To do so, we coexpressed Aβ42 with LacZ or Hsp70 transgenes in all neurons and assessed the ability of flies to climb as a function of age. Comparing the four groups in double-blind experiments, we observed differences in climbing speed and in their overall ability to climb by day 10 (Fig. 5A). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and either LacZ or Hsp70 performed poorly at day 10. In contrast, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 performed similarly to control flies expressing LacZ (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

SecHsp70 alleviates the locomotor dysfunction induced by Aβ42. (A) Representative image of the locomotor activity of 10-d-old flies of the indicated genotypes. Vials show blinded identifying numbers. (B) Longitudinal activity of the indicated genotypes showing duplicates to indicate reproducibility. Arrow indicates the time for the image in A. Control flies expressing LacZ (green lines) reach 50% climbing index by day 22. Flies coexpressing Aβ42 with LacZ (red lines) reach 50% climbing by day 5. Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 (blue lines) reach 50% climbing by day 9. Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 (black lines) reach 50% climbing by day 15. (C) Survival curves of flies of the indicated genotypes. The horizontal line indicates 50% survival. Coexpression of secHsp70 significantly extends lifespan in flies expressing Aβ42 (same color coding as in B). ****P < 0.0001; n.s., nonsignificant.

The longitudinal analysis of the climbing ability indicated that control females expressing LacZ alone reached the 50% climbing index by day 22 and continued to move for 20 more days (Fig. 5B). In contrast, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ displayed severe locomotor dysfunction, reaching 50% climbing index by day 5 (Fig. 5B and Table S1). Surprisingly, flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 performed better than the positive controls, reaching 50% climbing by day 9 (Fig. 5B and Table S1). However, these flies performed similarly to the flies expressing Aβ42 and LacZ after day 12. Remarkably, flies expressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 displayed robust climbing ability, reaching 50% climbing activity by day 16 (Fig. 5B and Table S1), followed by slow locomotor decline until day 30. We also compared the climbing performance of the different Aβ42 combinations every 5 d (Table S1). At day 1, we found no significant differences in the performance of all Aβ42 combinations. However, between days 5 and 10, flies expressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 or secHsp70 performed significantly better that flies coexpressing LacZ. By day 15, the flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70 perform as poorly as those coexpressing LacZ, but flies coexpressing secHsp70 performed significantly better.

Table S1.

Analysis of climbing index by day

| Time | Analysis | Aβ42; LacZ | Aβ42; Hsp70 | Aβ42; secHsp70 |

| Day 1 | Mean, %, ± SD | 85.4 ± 9.2 | 89.8 ± 9.5 | 89.6 ± 9.5 |

| P value | — | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| Day 5 | Mean, %, ± SD | 42.5 ± 6.5 | 75.4 ± 8.7 | 89.5 ± 9.5 |

| P value | — | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Day 10 | Mean, %, ± SD | 12.7 ± 3.5 | 34.5 ± 5.9 | 70.4 ± 8.4 |

| P value | — | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Day 15 | Mean, %, ± SD | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 6 ± 2.4 | 49.7 ± 7 |

| P value | — | 0.6 | <0.0001 |

All P values are the result of comparing the climbing index (%) of each Aβ42;Hsp70 and Aβ42;secHsp70 genotype with respect to Aβ42;LacZ.

We also monitored the longevity of the same flies described above. The negative control flies expressing only LacZ lived for 75 d, with a 50% survival of 70 d (Fig. 5C). The survival curve for control flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ was very similar to that of flies coexpressing Aβ42 and Hsp70, with a 50% survival of 28 d and all flies dead by day 46 (Fig. 5C). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 had an extended lifespan, with a 50% survival at day 54 and a few flies living for more than 70 d (Fig. 5C), almost double the 50% survival of Aβ42/LacZ flies but 15 d shorter than control LacZ flies. In all, these observations support the ability of secHsp70 to protect neuronal activity against Aβ42 neurotoxicity in vivo.

SecHsp70 Colocalizes and Interacts with Aβ42 in Brain Neurons.

To determine whether the neuroprotective activity shown above is mediated by direct interaction with Aβ42, we first examined the colocalization of both proteins. For this, we performed immunofluorescence in a small cluster of neurons in the anterior lateral protocerebrum using the OK107-Gal4 driver (Fig. 6A). Coexpression of Aβ42 and CD8-GFP confirmed that most Aβ42 codistributed with GFP in the membrane, although large puncta suggested that some Aβ42 was still in transit to the membrane, possibly in the Golgi (Fig. 6A). Coexpression of Aβ42 and Hsp70 showed Hsp70 in the cytosol, confirming their distinct distribution (Fig. 6B). Coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 confirmed the colocalization of the two proteins in the membrane (Fig. 6C), supporting the intended design of secHsp70. However, the presence of secHsp70 in the membrane had no effect on Aβ42 distribution or accumulation (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

SecHsp70 colocalizes and interacts with Aβ42. (A–C) Subcellular distribution of Aβ42 and Hsp70 constructs in brain neurons. Coexpression of Aβ42 and CD8-GFP colocalize in the membrane (arrows) and Aβ42 accumulates in the Golgi (A). Hsp70 accumulates intracellularly and does not change Aβ42 distribution (B). (C) SecHsp70 colocalizes with Aβ42 in the membrane, but Aβ42 is not altered. (D) SecHsp70 immunoprecipitates with Aβ42. Three controls (lanes 1–3) show that 6E10 produces high-molecular-weight bands from antibody fragments. All of the head homogenates expressing Aβ42 show capture in the column (lanes 4–6). (E) SecHsp70 coimmunoprecipitates with Aβ42. Head extracts from flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ or Hsp70 (lanes 4 and 5) show no co-IP of Hsp70. Coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70 (lane 6) coimmunoprecipitates Hsp70. Another band above 75 kDa suggests elution of an Hsp70/Aβ42 complex.

Previous evidence has shown that Aβ42 is a good substrate for Hsp70 in vitro (18, 19). To demonstrate the interaction of secHsp70 and Aβ42 in vivo, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) from head homogenates with beads bound to the 6E10 anti-Aβ42 antibody. First, we analyzed the Aβ42 captured with the 6E10 antibody from the homogenates (IP). Although all of the lanes containing fly extracts produced high background due to the release of antibody fragments, only the flies expressing Aβ42 in lanes 4–6 showed Aβ42 immunoreactivity at the expected molecular weight of 4 kDa (Fig. 6D). Then, we analyzed the ability of Aβ42 bound to the column to co-IP Hsp70. The negative controls in lane 2 demonstrated good conditions for co-IP. The addition of a non-Aβ42 extract produced a more intense high-molecular-weight background but no specific signal at 70 kDa (Fig. 6E, lane 3). The incubation with fly extracts coexpressing Aβ42 with either LacZ or Hsp70 produced the same background signal as the non-Aβ42 control, indicating no binding to Hsp70 (Fig. 6E, lanes 4 and 5). However, incubation with the homogenate expressing Aβ42 and secHsp70 revealed a specific band around 70 kDa corresponding to Hsp70 (Fig. 6E, lane 6). We also identified a higher band that could correspond to a complex between Hsp70 and Aβ42. These results demonstrate the ability of secHsp70 to bind extracellular Aβ42 in vivo, suggesting that the protective activity of secHsp70 is mediated by this direct interaction.

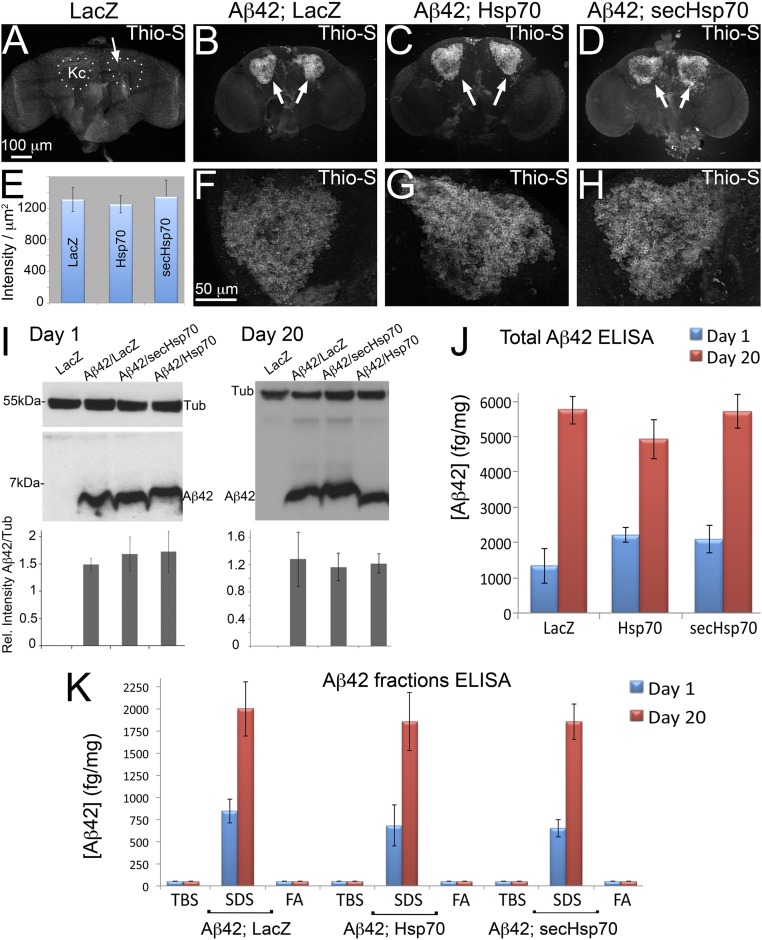

SecHsp70 Does Not Affect the Steady-State Levels of Aβ42.

We next asked whether secHsp70 reduced Aβ42 aggregation. To test this, we first incubated Drosophila brains with thioflavin-S, a compound that emits green fluorescence upon binding to amyloid fibers. As expected, control flies expressing LacZ in mushroom body neurons revealed no fluorescence in the Kenyon cells (Fig. 7A). Flies expressing Aβ42 and LacZ accumulated intense fluorescence in the Kenyon cell clusters (Fig. 7 B, E, and F). Coexpression of Aβ42 with either Hsp70 or secHsp70 had no significant effect on the intensity and distribution of thioflavin-S fluorescence (Fig. 7 C–E, G, and H).

Fig. 7.

Secreted Hsp70 suppresses Aβ42 neurotoxicity without Aβ42 clearance or disaggregation. (A–H) Accumulation of the amyloid dye thioflavin-S in the Drosophila brain in flies expressing LacZ or Aβ42 transgenes under the control of OK107-Gal4. Control flies expressing LacZ in the Kenyon cells (Kcs; arrow) show no localized signal for thioflavin-S (A). Flies coexpressing Aβ42 and LacZ display strong fluorescence in the Kc (B and F). Coexpression of Aβ42 and Hsp70 (C and G) or secHsp70 (D and H) has no effect on thioflavin-S intensity. Quantification of the fluorescent signal from thioflavin-S shows no significant differences among the different genotypes (E). (I–K) Quantification of Aβ42 in the Drosophila brain. Western blot in 1- and 20-d-old flies shows no significant differences in flies coexpressing Aβ42 with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 (n = 3) (I). Quantification of total Aβ42 by ELISA at days 1 and 20 showed no significant differences in flies coexpressing Hsp70 constructs (n = 5) (J). Quantification of Aβ42 in the TBS, SDS, and FA fractions (n = 5) showed no significant effects on Aβ42 distribution among the fractions (K).

We next analyzed the steady-state levels of total Aβ42 by Western blot and ELISA. For this, we generated homogenates from 10 heads, performed Western blot, and detected Aβ42 with the 6E10 antibody. Interestingly, we found no significant changes in the levels of Aβ42 in young and old flies coexpressing secHsp70 (Fig. 7I). Consistent with the Western blot, examination of the homogenates by ELISA detected no significant differences in total Aβ42 (Fig. 7J). These results suggest that the protective activity exerted by secHsp70 is not mediated by Aβ42 clearance.

We finally asked whether secHsp70 affected the dynamics of Aβ42 aggregation. For this, we generated head homogenates and separated the Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-soluble, SDS-soluble, and SDS-insoluble fractions by centrifugation. Then, we resolubilized the SDS-insoluble fraction with formic acid (FA fraction) and quantified all of the fractions by ELISA. In all of the combinations, the SDS fraction contained most of the Aβ42, supporting the formation of intermediate (soluble) Aβ42 aggregates in flies. Remarkably, we found no significant change on Aβ42 aggregation in flies coexpressing Hsp70 or secHsp70 (Fig. 7K). Thus, these studies indicated that the protective activity of secHsp70 is not mediated by promoting Aβ42 disaggregates from the SDS and FA fractions to either the TBS fraction.

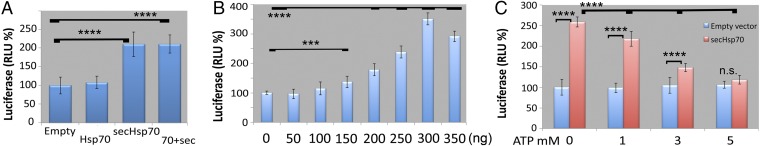

SecHsp70 Promotes Aβ42 Aggregation.

To examine in more detail the effects of secHsp70 on the dynamics of Aβ42 aggregation, we used a cellular assay based on a split luciferase fused to Aβ42 that generates luminescence upon Aβ42 dimerization (33). This assay provides a sensitive and quantitative method to examine the effect of Hsp70 constructs on Aβ42 aggregation. HEK293 cells constitutively expressing Aβ42 fused to N- and C-terminal fragments of luciferase were transiently transfected with Hsp70 constructs. We measured luciferase signal in the extracellular media after 24 h, enough time for the formation of oligomers and soluble protofibers, the most toxic species, but too short for insoluble fibers. Expression of Hsp70 generated the same luciferase activity as the control cells, indicating that Hsp70 had no effect on Aβ42 aggregation (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the luciferase signal doubled in cells expressing secHsp70 (Fig. 8A), suggesting a direct effect of secHsp70 on the formation/stability of dimers or oligomers. We next transfected the cells with increasing amounts of secHsp70 cDNA to examine the dynamics of its interaction with Aβ42. Transfection with up to 100 ng of secHsp70 had no effect on Aβ42 aggregation (Fig. 8B). Addition of secHsp70 above 150 ng promoted Aβ42 aggregation, with a maximum aggregation (3.5-fold) at 300 ng (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, 350 ng of secHsp70 cDNA partially inhibited dimerization. This result suggests that excess secHsp70 binds misfolded Aβ42 monomers and prevents dimerization (Fig. 8B). Overall, these results are consistent with previous findings in recombinant systems (19), but we show the proaggregation activity of secHsp70 in a more physiological cellular system.

Fig. 8.

SecHsp70 promotes Aβ42 aggregation. (A) Transient transfection with indicated constructs into stable HEK293 cells expressing N-Luc-Aβ42 and C-Luc-Aβ42. Luminescence in the media after 48 h indicates that secHsp70 promotes Aβ42 aggregation (n = 12), (B) Transient transfection with increasing amounts of secHsp70 promotes Aβ42 aggregation, with a peak at 300 ng. (C) Luminescence of conditioned media at 12 h after addition of 1, 3, or 5 mM of ATP. Addition of 5 mM ATP completely reverses the effect of secHsp70 on Aβ42 aggregation. n = 12; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; n.s., nonsignificant.

The proaggregation effects of secHsp70 were obtained in the absence of exogenous ATP, mimicking the lack of ATP in the extracellular environment in the Drosophila experiments. These results suggest that the holdase activity of Hsp70 is responsible for this effect wheras the foldase activity is dispensable. To test this, we added ATP at different concentrations, which should promote Hsp70 cycling and the release of Aβ42. The control experiment without ATP showed a 2.5-fold increase in signal, consistent with previous results (Fig. 8C). Addition of 1 mM ATP decreased slightly the luciferase signal, but addition of 3 or 5 mM ATP inhibited the proaggregation effect of secHsp70 (Fig. 8C). In fact, addition of 5 mM ATP reduced Aβ42 aggregation to the levels of the empty vector. These results show that the holdase activity of Hsp70 promotes Aβ42 whereas its foldase activity inhibits it. Thus, the lack of ATP allows the holdase activity to stably bind Aβ42 aggregates, masking their neurotoxic epitopes.

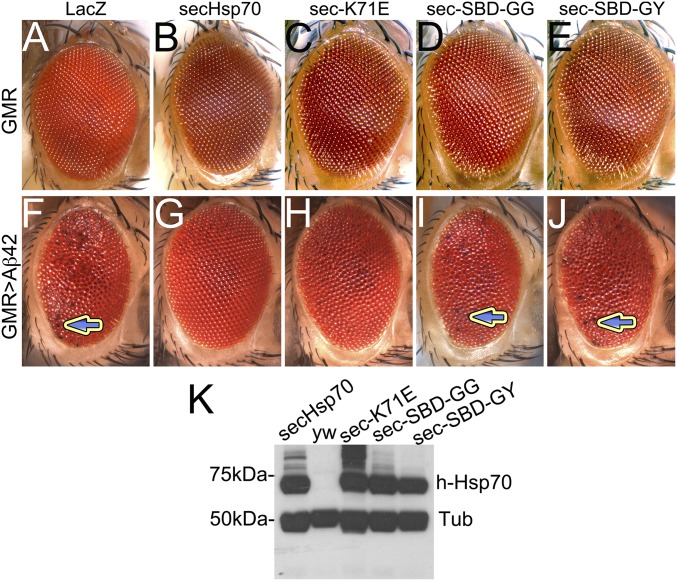

The ATPase Activity Is Not Required for the Protective Activity of secHsp70.

To dissect in more detail the mechanism mediating the protective activity of secHsp70, we introduced mutations that knock out the ATPase domain and SBD. ATPase-dead mutations in Drosophila Hsc3 and Hsc4 were shown previously to perturb eye development through dominant-negative effects (34) and enhance the toxicity of Atx3-78Q (10). We introduced the K71E substitution in human HSPA1L to compare all of the mutants in the same protein context. As expected, expression of Hsp70-K71E alone in the eye results in small, disorganized, and depigmented eyes (Fig. 9 A–C). Hsp70-K71E also enhanced the toxicity of Atx3-78Q (Fig. 9 F–H), supporting its dominant-negative activity. Although we tried to select mutant Hsp70 constructs expressed at similar levels to Hsp70-WT, only flies expressing low levels of Hsp70-K71E in the eye survived, with several additional lines showing pupal lethality (Fig. 9K).

Fig. 9.

The ATPase domain is critical for Hsp70 neuroprotection. (A–E) Expression of WT and mutant Hsp70 constructs in the eye. LacZ (A) and Hsp70-WT (B) have no effect on the eye. Expression of the K71E (C) and A406G+V438G (D) mutants disrupts eye development. The A408G+V438Y mutant has no effect, suggesting that it is a null allele (E). (F–J) Coexpression of Atax3-78Q and Hsp70 constructs. Hsp70-WT fully rescues Atx3-78Q toxicity (F and G). Coexpression with K71E results in very small eyes (H). Coexpression with A406G+V438G results in small and disorganized eyes (I). Coexpression with A406G+V438Y has no effect on Atx3-78Q (J). (K) The expression level of the SBD mutants is comparable to that of the WT Hsp70, but K71E is lower.

We next introduced the ATPase-dead mutation in the context of secHsp70 (secHSPA1L). Expression of secHsp70-K71E alone had no effect in the eyes (Fig. 10 A–C), indicating that it can only cause dominant-negative effects in the presence of client proteins and cofactors. Based on our previous results, we predicted that the ATPase-dead secHsp70 would still rescue Aβ42 because the holdase activity was sufficient to bind Aβ42 and mask its neurotoxicity. Coexpression of Aβ42 and secHsp70-K71E resulted in almost normal eyes, very similar to those expressing secHsp70 (Fig. 10 F–H). These results confirm our prediction that the ATPase activity of secHsp70 is not required to suppress Aβ42 toxicity, which contrasts dramatically with the activity of intracellular Hsp70. Notice that the expression level of secHsp70-K71E is similar to that of secHsp70 (Fig. 10K).

Fig. 10.

The holdase activity mediates secHsp70 neuroprotection. (A–E) Expression of WT and mutant secHsp70 constructs in the eye. LacZ (A) and secHsp70 (B) have no effect on the eye. Expression of K71E (C), A406G+V438G (D), and A408G+V438Y has no effect in the eye. (F–J) Coexpression of secHsp70 and Aβ42. SecHsp70 completely rescues Aβ42 toxicity in the eye (F and G). Coexpression with K71E rescues the eye (H). Coexpression with A406G+V438G and A406G+V438Y has no effect on the toxicity of Aβ42 (arrows) (I and J). (K) The expression level of all of the mutants is comparable to that of the WT secHsp70.

The Holdase Activity of secHsp70 Is Critical for Neuroprotection.

To examine the role of the SBD in the protective activity of secHsp70, we introduced mutations that reduce the affinity for substrates in refolding assays (35). We introduced the double mutation A406G+V438G in the context of HSPA1L and secHSPA1L and examined their effects in transgenic flies. This double mutation was expected to disrupt the SBD and cause a loss-of-function of Hsp70. Instead, expression of Hsp70-A406G+V438G alone induced small and disorganized eyes indicative of a dominant-negative effect (Fig. 9D). This mutant also enhanced Atx3-78Q toxicity in the eye (Fig. 9I), suggesting that it could still bind substrates but not process them completely. To robustly disrupt the hydrophobic pocket, we next introduced a polar residue in the SBD: A406G+V438Y. Expression of Hsp70-A406G+V438Y alone had no effect in the eye (Fig. 8E), indicating that the stronger substitution acts as a true null allele that cannot bind substrates. Hsp70-A406G+V438Y had no effect on the toxicity of Atx3-78Q (Fig. 9 F and J), supporting its inability to bind substrates. The expression level of the A406G+V438Y mutant is similar to that of the A406G+V438G and WT alleles (Fig. 9K).

We next analyzed the consequence of mutating the SBD in the context of secHsp70. Expression of secHsp70-A406G+V438G alone had no effect in the eye (Fig. 10D) due to the lack of natural substrates. Additionally, secHsp70-A406G+V438G did not rescue the Aβ42 eye phenotype, resulting in small and disorganized eyes with necrotic spots (Fig. 10I). Lastly, expression of the stronger secHsp70-A406G+V438Y alone had no effect in the eye either (Fig. 10E). Importantly, secHsp70-A406G+V438Y did not rescue Aβ42 toxicity in the eye (Fig. 10J), indicating that binding is sufficient for the protective activity. Notice that the expression level of the SBD mutants is similar to that of secHsp70 (Fig. 10K). Overall, these results demonstrate that the refolding activity of secHsp70 is dispensable whereas the holdase activity mediated by binding through the SBD is critical for the protective activity against Aβ42 in the extracellular space.

Discussion

Hsp70 not only is a potent cellular chaperone (36) but also recognizes a wide range of substrates (17), resulting in robust protection against several intracellular amyloids (10–13). Motivated by the lack of effective therapies for extracellular amyloids, we examined the protective activity of a chimeric Hsp70 engineered for extracellular secretion in a Drosophila model of Aβ42 neurotoxicity. We approached this project with the caveat that the lack of cochaperones, low ATP, and a highly oxidizing environment (37) could inhibit Hsp70 activity in the extracellular space. Despite these risks, we demonstrate here that secHsp70 robustly suppresses Aβ42 neurotoxicity in multiple assays in Drosophila. We also show that this protective activity is mediated by the holdase activity of Hsp70 through direct binding to Aβ42 whereas its foldase activity seems superfluous. Thus, we describe an activity for Hsp70 outside the cell capable of neutralizing Aβ42 neurotoxicity without the contribution of other cellular machinery involved in protein folding or degradation. We propose here that secHsp70 binds Aβ42 and masks the neurotoxic epitopes in its assemblies, an activity that does not involve the classic refolding activity of Hsp70. These observations may have relevant implications for understanding amyloid toxicity and developing therapeutic applications.

Our experiments demonstrate that Aβ42 and Atx3-78Q exert their toxicity mainly in one cellular compartment, as BiP/Hsc3 has no effect in either model and secHsp70 has no effect on Atx3-78Q toxicity. Interestingly, we observed a small but significant benefit from Hsp70 against Aβ42 in some assays. This protection can be explained by two alternative mechanisms. One involves intracellular reuptake of secreted Aβ42 and direct interaction with cytosolic Hsp70. Aβ42 oligomers have been proposed to reenter neurons by both active (endocytosis, exosomes) and passive (formation of pores) mechanisms (38), which explain the induction of ER stress and the release of intracellular calcium stores. Alternatively, Hsp70 can exert pleiotropic activities that promote proteostasis and reduce cellular stress. Several reports have demonstrated the neuroprotective activity of Hsp70 against oxidative stress, mitochondrial depolarization, and JNK-mediated cell death (39, 40). Also, damaged cytosolic proteins resulting from Aβ42-induced oxidative stress may be eliminated via Hsp70-mediated proteasome activity and autophagy (41, 42). This indirect activity is consistent with recent reports showing that Hsp70 overexpression alleviates memory deficits in APP mice by activating the expression of insulin-degrading enzyme (22). Given the documented protective effects of Hsp70, the combination of both intra- and extracellular Hsp70 are expected to exert potent benefits against Aβ42 and other extracellular amyloids.

Many fatal neurodegenerative diseases are associated with extracellular protein misfolding, including AD, prion diseases, several eye disorders, systemic amyloidosis, and type 2 diabetes. Only recently, a growing family of constitutively secreted chaperones was identified in the extracellular space, including clusterin and α-macroglobulin (43). These proteins resemble small heat shock proteins as they mask hydrophobic residues and prevent aggregation but are unable to refold substrates. Interestingly, clusterin expression is elevated in models of AD (37), and preincubation with clusterin reduced the toxicity of Aβ42 oligomers in SY5Y cells and rat brains (19, 44), suggesting a protective activity. In contrast, clusterin knockout lessens fibrillar Aβ deposition and neurotoxicity in APP transgenic mice, suggesting that clusterin promotes Aβ toxicity in vivo (45, 46). Although these data indicate that clusterin can modulate Aβ42 toxicity, its precise role in AD remains to be elucidated. Overall, it seems that the natural secreted chaperone system provides a limited protective response to the Aβ42 challenge, opening a therapeutic opportunity by increasing the levels of extracellular chaperones, including the chimeric secHsp70.

Here, we present an alternative approach to block Aβ42 toxicity by genetic engineering of a cytosolic chaperone. We demonstrate that the deliberate secretion of Hsp70 robustly neutralizes the toxicity of Aβ42 assemblies in the Drosophila eye and brain neurons, an activity for which the ATPase domain is dispensable. The protective activity of ATPase-dead secHsp70 is consistent with the lack of cochaperones and the low levels of ATP in the extracellular compartment, suggesting no relevant role for the foldase activity in this context. Our data suggest that the protective activity of secHsp70 is mediated by a potent holdase activity that binds and stabilizes small Aβ42 assemblies into nontoxic complexes. We propose that the holdase activity robustly neutralizes (masks) Aβ42 neurotoxicity by preventing the interaction of toxic assemblies with cellular substrates and inhibiting the ability of Aβ42 oligomers to disrupt membranes, penetrate cells, and spread to neighboring cells (38). The lack of secHsp70 cycling in the extracellular space critically promotes the formation of highly stable, nonreversible, nontoxic Aβ42/Hsp70 complexes. Previous in vitro work concluded that under high ATP concentrations the refolding activity of Hsp70 prevents Aβ42 aggregation (18). But under low ATP concentrations, Hsp70 promotes Aβ42 nucleation into nontoxic aggregates (clustering) that is proposed to reduce the mobility and eliminate some of the biophysical properties that make oligomers highly toxic (19). It is possible that the potent in vivo protective activity of secHsp70 that we describe here is a combination of both clustering and masking because both phenomena coexist in the experiments described so far (ref. 19 and this report). We recently observed a similar phenomenon in flies coexpressing anti-Aβ42 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) antibodies in Drosophila (47), further suggesting that Aβ42-binding agents can be protective without decreasing the levels of Aβ42. Furthermore, the formation of nontoxic complexes by secHsp70 is consistent with our previous observation that Hsp40 overexpression promotes Atx1-82Q aggregation into nontoxic inclusions (48), supporting the idea that large amyloid assemblies are protective (49–51).

Overall, the holdase activity of Hsp70 demonstrates robust protective activity against Aβ42, uncovering mechanisms to block Aβ42 neurotoxicity. A key advantage of secHsp70 as a therapeutic agent compared with antibodies and classic compounds is its protective activity at substoichiometric concentrations (19). Additionally, the broad substrate spectrum of Hsp70 may also prove useful against the prion-like spread of different oligomeric assemblies proposed to mediate disease spread of synucleinopathies, tauopathies, and TDP-43 proteinopathies (38, 52, 53). The current limitations for the therapeutic delivery of secHsp70 may be soon overcome by novel and safer technologies for gene therapy.

Materials and Methods

Cloning.

To generate secHsp70, we digested pUAS-HSPA1L (a gift from N. Bonini, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) (10) at the polylinker and five codons downstream of the ORF. Then, we ligated an oligonucleotide encoding a Kozak sequence, the human Ig heavy chain V-III signal peptide, and the first five amino acids of HSPA1L (SI Materials and Methods). To generate ATPase-dead and SBD-inactive domains, we carried out mutagenesis over pcDNA3.1-HSPA1L and subcloned the products into pUAST-HSPA1L or pUAST-secHSPA1L.

Drosophila Genetics.

The flies expressing two copies of UAS-Aβ42 were described previously (28). Flies carrying four copies of the GMR-Aβ42 fusion (29) were kindly provided by M. Konsolaky, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ. All crosses were initially placed at 25 °C for 2 d, progeny was raised at different temperatures depending on the assay, and the adults were aged at the same temperature. All assays were performed using females, except for the Aβ42 eyes, to take advantage of the stronger phenotype in males.

Drosophila S2R+ Cell Culture.

Drosophila S2R+ cells were maintained in Schneider media at 26 °C as described (54). We cotransfected 4 × 105 cells in duplicate with 200 ng of pAC-Gal4 (Addgene) and Hsp70 vectors in 24-well plates with Qiagen Effectene. Forty-eight hours later, the media was collected and precipitated for Western blot analysis and immunostaining.

Eye Degeneration.

For Atx3-78Q, we collected 1-d-old female GMR-Gal4/UAS-Atx3-78Q at 25 °C. For Aβ42, we collected 1-d-old males GMR-Gal4/UAS-Aβ42 at 28 °C. For nonautonomous rescue, we collected 1-d-old female GMR-Aβ42(2×)/UAS-GFPattP or/repo-Gal4; UAS-secHsp70 at 29 °C. To image fresh eyes, we froze the flies at –20 °C, collected Z-stacks with a Leica Z16 APO, and generated single in-focus images. For SEM, flies were serially dehydrated, air-dried, and metal-coated for observation in a Jeol 1500 SEM.

Tissue Staining.

We fixed larval eye discs and incubated them with the anti-human Hsp70 and anti-Elav antibodies. For colocalization, we coexpressed Aβ42 and Hsp70 constructs, fixed brains at day 1, and stained them with anti-Hsp70 and 4G8 anti-Aβ42 antibodies. For S2R+ cells, we used anti-Hsp70 and anti-Hsc3 antibodies. Whole-mount immunofluorescence was conducted as described (48) by fixing in 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde, washing with 1× PBT, and blocking with 3% BSA. We used the secondary antibodies anti-mouse-Cy3 and anti–rabbit-FITC. We used the TUNEL assay with fluorescein from Roche with a few modifications (SI Materials and Methods). For thioflavin-S, we fixed and incubated 1-d-old brains in a 0.03% solution of fresh thioflavin-S (Sigma) in 50% ethanol/PBS for 10 min.

Microscopy and Image Processing.

We collected adult flies of the indicated genotypes and imaged GFP distribution in mushroom bodies at days 1, 20, and 40 in an Axio-Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss). Maximum intensity projection images, representative single plane images, and 3D images were created in AxioVision. Data series were analyzed for statistical significance in GraphPad Prism using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Final images were combined using Adobe Photoshop to create multipanel figures. Image processing was minimal but included brightness/contrast adjustment to whole images for optimal viewing and printing.

Locomotor and Longevity Assays.

Progeny carrying the indicated genotypes at 25 °C were tested daily for their ability to climb with the genotypes blinded to the experimenter as previously described (55). The climbing index was calculated as follows: no. flies above line/no. total flies × 100. The two replicates were averaged to compare climbing by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. For longevity studies, we used the same flies and recorded lost flies each day. We averaged duplicates and analyzed the survival curves between genotypes using the log-rank test (Mantel–Cox).

Western Blot and ELISA.

Fly heads or cultured cells were homogenized essentially as described (28). Following PAGE and transfer, membranes were probed against Aβ 6E10), β-Tubulin, and human Hsp70 polyclonal antibody, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. For total Aβ42 ELISA, five heads were homogenized in 50 µL GnHCl extraction buffer in five replicates. To analyze fractions, five fly heads were sequentially extracted with TBS, 2% SDS, and 70% FA. Fractions were serially diluted for sandwich ELISA in five replicates. Aβ42 was captured with mAb 2.1.3 (Aβ35–42, TG) and detected by HRP-conjugated mAb Ab9 (pan-Aβ, TG). Values were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Co-IP.

Forty heads per genotype were homogenized in 30 μL of extraction buffer. We used the Dynabead co-IP kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations with minor modifications. The Dynabead–Aβ complex was incubated with 25 μL of homogenate and 330 μL of extraction buffer for 14 h. Upon washing, proteins were eluted by boiling in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and detected by Western blot using the anti-human Hsp70 polyclonal antibody.

Split-Luciferase Aβ42 Dimerization Assay.

HEK293 cells expressing the split-luciferase Aβ42 system were a gift from B. Hyman, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA (33). Cells were transfected with 250 ng pcDNA3.1-based Hsp70 constructs. To assess the effect of ATP, we added 1, 3, and 5 mM ATP for 24 h. Luciferase signal in the media was analyzed in two independent experiments in sextuplicate each. After normalization, we analyzed for statistical significance using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of Constructs.

To generate secHsp70, the plasmid pUAS-HSPA1L (a gift from N. Bonini) (10) was digested with EcoRI at the polylinker and SacII five codons downstream of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA translation initiation site. Then the open vector was ligated with the following oligonucleotide encoding a Kozak sequence, the human Ig heavy chain V-III signal peptide, and the first five amino acids of HSPA1L flanked by EcoRI and SacII sites (underlined): GAATTCCACCATGGAGTTCGGACTGAGCTGGCTGTTCCTGGTCGCCATACTCAAAGGAGTCCAGTGCGAGGTTATGGCCAAAGCCCGG. The resulting construct, pUAS-secHsp70, was sequenced in both strands to confirm the identity and integrity of the chimeric fusion. To generate ATPase-dead and SBD-inactive domains, mutagenesis was carried out over pcDNA3.1-HSPA1L and subcloned into pUASt-HSPA1L or pUASt-secHSPA1L by EcoRI-XbaI or SacII-XbaI, respectively. The following mutagenic oligonucleotides were used: K71E-Fw, 5′-CCGATCAGCCGCTC CGCGTCAAACACG-3′; K71E-Rev, 5′-CGTGTTTGACGCGGAGCGGCTGA TCGG-3′; A406G-Fw, 5′-GCTGGAGACGGGCGGAGGCGTGA-3′; A406G-Rev, 5′-GCTGGAGACGGGCGGAGGCGTGA-3′; V438G-Fw, 5′-CACCTGGATCAGCCCCCCGGGTTGGTT-3′; V438G-Rev, 5′-AACCAACCC GGGGGGCTGATCCAGGTG-3′; V438Y-Fw, 5′-CCGACAACCAACCCGGGTAGCTGATCCAGG TGTACGA-3′; and V438Y-Rev, 5′-TCGTACACCTGGATCAGCTA CCCGGGTTGGTTGTCGG-3′.

For oligomerization studies in HEK293 cells, the Hsp70 and secHsp70 ORFs were released from the pUAS vectors with EcoRI and XbaI and subcloned into the same sites of pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) to generate pcDNA3.1-Hsp70 and pcDNA3.1-sHsp70.

Transgenic Flies and Drosophila Genetics.

We generated transgenic lines by injecting the pUAST-based constructs pUAS-secHsp70, pUAS-secHsp70-K71E, pUAS-secHsp70-A406G+V438G, pUASsecHsp70-A406G+V438Y, pUAS-Hsp70-K71E, pUAS-Hsp70-A406G+V438G, and pUAS-Hsp70-A406G+V438Y into yw embryos at Rainbow Transgenics following standard procedures (56).

Flies were maintained on standard Drosophila medium at 25 °C. The driver strains GMR-Gal4 (all eye cells), OK107-Gal4 (mushroom bodies), and Elav-Gal4 (pan-neural); the reporters UAS-LacZ and UAS-CD8-GFP; and the UAS-HSC3 (BiP) and UAS-Atx3-78Q (27) lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. UAS-sEGFP (secreted EGFP) was kindly provided by B.-Z. Zhilo, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel (57). Flies carrying four copies of the GMR-Aβ42 fusion (30) showed low penetrance and expressivity. To eliminate second-site modifiers and restore the robust eye phenotype of this stock, we recombined over yw and Vallecas WT strains and reconstituted the double homozygous stock in chromosomes 2 and 3. For experiments, homozygous females for the Gal4 strains were crossed with UAS males to generate progeny expressing Aβ42 in the desired tissue.

Drosophila S2R+ Cell Culture.

Drosophila S2R+ cells were maintained in Schneider media at 26 °C as described (54). Briefly, 4 × 105 cells were cotransfected in duplicate with 200 ng of pAC-Gal4 (Addgene) and Hsp70 vectors in 24-well plates with Qiagen Effectene. Forty-eight hours later, the media was collected and precipitated for Western blot analysis and immunostaining using anti-Hsp70 and anti-Hsc3 antibodies.

Eye Degeneration.

For imaging Atx3-78Q eyes, we crossed GMR-Gal4: Atx3-78Q females with LacZ, Hsp70, BiP, and secHsp70 at 25 °C and collected 1-d-old females. For Aβ42 eyes, we crossed GMR-Gal4: Aβ42 females with LacZ, Hsp70, BiP, and secHsp70 at 28 °C and collected 1-d-old males to maximize the phenotype. For nonautonomous rescue, we collected 1-d-old females from the progeny of GMR-Aβ42(4×) × UAS-GFPattP or × repo-Gal4; UAS-secHsp70 at 29 °C. To image fresh eyes, we froze the flies at –20 °C for at least 1 d. Then, we collected eye images as Z-stacks with a Leica Z16 APO using a 2× Plan-Apo objective and generated single in-focus images with the Montage Multifocus module of the Leica Application Software. For SEM, flies were serially dehydrated in ethanol, air-dried in hexamethyldisilazane (Electron Microscope Sciences), and metal-coated for observation in a Jeol 1500 SEM.

Immunofluorescence.

We expressed Hsp70 and secHsp70 in eye disk under the control of GMR-Gal4 at 25 °C, dissected wandering third instar larvae, fixed eye discs, and stained them with the rabbit anti-human Hsp70 (1:200, Stressgen) and rat anti-Elav (1:75, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) antibodies. For colocalization, we coexpressed Aβ42 and Hsp70 constructs under the control of OK107-Gal4, fixed brains at day 1, and stained them with anti-Hsp70 and 4G8 anti-Aβ42 (1:150, Covance) antibodies. For S2R+ cells we used the anti-Hsp70 antibody and the guinea pig anti-Hsc3 antibody kindly provided by H. Steller, The Rockefeller University, New York (58). Whole-mount immunofluorescence of adult brains and larval eye discs was conducted as described previously (48) by fixing in 4% formaldehyde, washing with PBT, and blocking with 3% BSA. The secondary antibodies anti-mouse Cy3 (Molecular Probes) and anti-rabbit FITC (Sigma) were used at 1:600. After washing the secondary antibody, tissues were mounted on Vectashield antifade (Vector).

TUNEL Staining.

To document cell death, we used the TUNEL assay with fluorescein from Roche. For eye imaginal discs, we generated flies expressing LacZ alone or Aβ42 together with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 under the control of GMR-Gal4 at 25 °C. For the brain, we generated flies expressing LacZ alone or Aβ42 together with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 under the control of OK107-Gal4 at 27 °C and aged them for 20 d. Once we fixed the eye discs and whole brains, we followed the manufacturer’s recommendations with a few changes to optimize penetration and signal in whole-mount samples (30). We permeabilized in 100 mM sodium citrate for 45 min at 65 °C, washed, preincubated in 45 µL with 50% label solution for 30 min at 37 °C, added 5 µL of enzyme, incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, washed thoroughly, and mounted in Vectashield. For eye discs, we first performed staining with 4G8 antibody and then proceeded with the same TUNEL protocol. TUNEL-positive cells were manually counted from flattened stacks and entered in Excel to generate the graphs. Means were analyzed in GraphPad Prism using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Thioflavin-S Staining.

We generated flies expressing LacZ alone or Aβ42 together with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 under the control of OK107-Gal4 at 25 °C. Then, we fixed 1-d-old brains and incubated them with a 0.03% solution of freshly prepared and filtered thioflavin-S (Sigma) in 50% ethanol/PBS for 10 min, washed them, and mounted them in Vectashield. We calculated thioflavin-S intensity and area from single plane images outlined manually in Photoshop and calculated the average intensity per µm2 from those parameters. At least 10 images were analyzed per genotype and the differences between the positive control (Aβ42; LacZ) and the Hsp70 constructs were determined by t test.

Microscopy and Image Processing.

We collected fluorescent images with AxioVision (Zeiss) in an Axio-Observer Z1 microscope (Zeiss) by optical sectioning using ApoTome (structured light microscopy) with 20× NA, 0.7 (air); 40× NA, 0.75 (air); and 63× NA, 1.4 (oil) objectives. Maximum intensity projection images were created in AxioVision (geometric processing, orthoview) for Z-stacks containing the whole eye disk (Figs. 1 and 3). Representative single-plane images of calyces (Figs. 4 and 6) and Kenyon cells (Fig. 7) were extracted from Z-stacks. 3D images were created from Z-stacks in AxioVision rendered in the transparency mode and textured method (Figs. 1 and 4). 3D mushroom bodies (Fig. 4A) were also color-coded for depth. Final images were combined using Adobe Photoshop to create multipanel figures. Image processing was minimal but included brightness/contrast adjustment to whole images for optimal viewing and printing.

Analysis of Mushroom Body Degeneration.

We generated flies expressing CD8-GFP under the control of OK107-Gal4 together with LacZ (negative control) or coexpressing Aβ42 and either LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 at 27 °C. We collected adult flies at day 1 posteclosion and aged them for 20 and 40 d. We then imaged GFP distribution at days 1, 20, and 40 by dissecting, fixing, and mounting the brains as described above. To quantify the surface of mushroom body axonal lobes, we flattened the Z-stacks and manually selected the maximum area for at least 10 images. To quantify the volume of the calyces, we collected Z-stacks with a 0.7-µm step for at least 10 mushroom bodies. Then, the areas in each plane were traced manually in ImageJ with the free Measure Stack plug-in, which rendered the total volume for each stack. The average volume for each condition and time point was entered in Excel to create the graphs. Finally, data series were analyzed for statistical significance in GraphPad Prism using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Locomotor and Longevity Assays.

Flies carrying LacZ alone or Aβ42 combined with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 were crossed with the pan-neural driver elav-Gal4 at 25 °C, and the progeny were tested daily for their ability to climb with the genotypes blinded to the experimenter as previously described (55). Briefly, 25–30 newborn adult females were placed in empty vials in duplicate. Every day, flies were forced to the bottom by firmly tapping against the surface. After 8 s, we recorded the number of flies that walked above 5 cm. This was repeated eight times to obtain the average climbing index each day (flies above line/total flies × 100). At the end of the experiment, the climbing index was plotted as a function of age in Excel. Data points are presented as mean values ± SD. First, we compared means between replicates of the same genotypes by t test. Because we found no significant differences between replicates, they were averaged to analyze the different genotypes by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. To compare the climbing index by day, we performed a similar analysis by averaging replicates per day followed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Significance was established with P values equal or lower than 0.01. For longevity studies, we used the same flies described for the climbing assays. We transferred these flies to new food vials every day and documented the number of flies dead or lost for other reasons. Then, we plotted the data in Excel and analyzed the values for statistical significance. We first compared survival rates between duplicates of each genotype with t test. Because no statistical significance was observed, we then averaged duplicates and analyzed the survival curves between genotypes using the log-rank test (Mantel–Cox). Significance was defined as P < 0.01. All statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism.

Tissue Homogenates and Western Blot.

Fly heads or cultured cells were homogenized essentially as described (29). For Western blots, we added NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (4×) to each sample, followed by boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein extracts were separated by SDS/PAGE in 4–12% Bis–Tris gels (Invitrogen) under reducing conditions and electroblotted into 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in TBS containing 5% nonfat milk and probed against Aβ (6E10, 1:1,000, Covance) and β-Tubulin (1:250,000, Sigma) antibodies. To optimize reactivity of the 6E10 antibody, membranes were boiled for 5 min in TBS. For S2R+ cells, the membrane was probed against a human Hsp70 polyclonal antibody (1: 1,000, Enzo Life Sciences), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at 1:2,500. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Thermo Scientific). Bands were quantified from three independent experiments, normalized to nonspecific bands, and reported as average ± SD. To analyze the statistical significance of the band intensity, we used GraphPad to carry out a one-way ANOVA.

ELISA of Total Aβ42 and Aβ42 Fractions.

To assess total Aβ42 levels by ELISA, five fly heads were homogenized in 50 µL GnHCl extraction buffer [5 M guanidinium HCl, 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.3), protease inhibitor mixture (Thermo Scientific), and 5 mM EDTA] and centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris. The resulting supernatants were analyzed as the total fly Aβ42 sample using five replicates. For preparation of soluble and insoluble fractions, five fly heads were sequentially extracted with 10 µL of TBS, 10 µL of 2% SDS, and 6 µL of 70% FA containing protease inhibitor mixture. The FA fraction was neutralized with 54 µL of 2 M Tris·HCl (pH 9.1), as described previously (59). Total Aβ42, TBS, 2% SDS, and neutralized 70% FA fractions were diluted at 1:20, 1:200, 1:400, and 1:100, respectively, for sandwich ELISA also in five replicates as described (60). Aβ42 was captured with mAb 2.1.3 (human Aβ35–42, 0.5 μg per well, T.E. Golde) and detected by HRP-conjugated mAb Ab9 (pan-Aβ, 1: 2,000, T.E. Golde). Data at day 1 and day 20 were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with the Tukey’s multiple comparison test in GraphPad Prism.

Co-IP.

We generated flies expressing Aβ42 together with LacZ, Hsp70, or secHsp70 under the control of OK107-Gal4 at 25 °C. Forty heads of each genotype or control yw were homogenized in 30 μL of extraction buffer [1× IP buffer (Invitrogen), 0.15M NaCl, 0.02 M MgCl2, 1× complete Mini (Roche), and 0.1 mM DTT]. The co-IP assay was conducted using the Dynabead co-IP kit (Invitrogen, 14321D) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations with minor modifications. Briefly, 1.5 mg of Dynabeads was incubated with 7 μg of 6E10 antibody for 14 h at 37 °C with rotation. The antibody-coated beads were washed and incubated with extraction buffer containing 0.3% of BSA for 40 min at room temperature (RT). After washing two additional times, the Dynabead–Aβ complex was incubated with 330 μL of extraction buffer and 25 μL of homogenate at 4 °C for 14 h with gentle rotation. Upon washing, immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by boiling in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and detected by Western blot in a 12% NuPAGE Bis–Tris gel using the anti-human Hsp70 polyclonal antibody.

Split-Luciferase Aβ42 Dimerization Assay.

The HEK293 cells expressing a complementary split-luciferase system to monitor Aβ42 oligomerization were a gift from B. Hyman (33). These cells express the N- and C-terminal fragments of Gaussia luciferase fused to Aβ in separate constructs (N-Luc-Aβ42 and C-Luc-Aβ42) with a signal peptide for secretion. Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and seeded in 24-well plates 24 h before transfection. Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as suggested by the manufacturer. Cells were transfected with 500 ng of pcDNA3.1 (mock), 250 ng Hsp70, 250 ng secHsp70, or 250 ng of each Hsp70 construct, using empty pcDNA3.1 to bring the total transfected DNA to 500 ng. For normalization, 7 ng of pCMV-Red Firefly Luc (Pierce) were added per well. After 48 h in Optimem, conditioned media from these cells was collected and centrifuged at 120 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris. Cells were washed with 1× d-PBS and lysed in 100 μL of 1× Luciferase cell lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific). To analyze the effect of ATP on secHsp70 activity, cells were incubated in the presence of 1, 3, and 5 mM of ATP (Sigma) for 24 h following transfection. Measures of Aβ oligomerization in cell media were performed in two independent experiments in sextuplicate each with Pierce Gaussia luciferase flash assay kit (Thermo Scientific) using a Biotech FX-800 microplate luminometer. Red Firefly Luc was measured with Pierce Firefly luciferase flash assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Data were calculated as relative luciferase activity (% Gaussia Luciferase/Red Firefly Luc) and analyzed for statistical significance in GraphPad Prism using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shailaja Emani for technical assistance, Nancy Bonini (University of Pennsylvania) for the human HSPA1L construct and flies, Mary Konsolaki (Rutgers University) for the GMR-Aβ42(4×) flies, Ben-Zion Shilo (Weizmann Institute for Science) for the secGFP flies, Bradley Hyman (Massachusetts General Hospital) for the HEK293 cells/split-luciferase Aβ42, Amit Singh (University of Dayton) for the optimized TUNEL protocol, Hermann Steller (Rockefeller University) for the anti-Hsc3 antibody, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) for fly strains, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. This work was supported by NIH Grants DP2 OD002721-01 (to P.F.-F.) and R21NS081356 (to D.E.R.-L.) and a McKnight Brain Institute Research Development Award (to P.F.-F. and D.E.R.-L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1608045113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Crews L, Masliah E. Molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(R1):R12–R20. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. Genetics of dementia. Lancet. 2014;383(9919):828–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: A critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. 2009;110(4):1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: An emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(3):349–357. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: Lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(2):101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winklhofer KF, Tatzelt J, Haass C. The two faces of protein misfolding: Gain- and loss-of-function in neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO J. 2008;27(2):336–349. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings CJ, et al. Chaperone suppression of aggregation and altered subcellular proteasome localization imply protein misfolding in SCA1. Nat Genet. 1998;19(2):148–154. doi: 10.1038/502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenoien DL, et al. Polyglutamine-expanded androgen receptors form aggregates that sequester heat shock proteins, proteasome components and SRC-1, and are suppressed by the HDJ-2 chaperone. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(5):731–741. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DebBurman SK, Raymond GJ, Caughey B, Lindquist S. Chaperone-supervised conversion of prion protein to its protease-resistant form. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(25):13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warrick JM, et al. Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat Genet. 1999;23(4):425–428. doi: 10.1038/70532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auluck PK, Chan HY, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Bonini NM. Chaperone suppression of alpha-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2002;295(5556):865–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adachi H, et al. Heat shock protein 70 chaperone overexpression ameliorates phenotypes of the spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy transgenic mouse model by reducing nuclear-localized mutant androgen receptor protein. J Neurosci. 2003;23(6):2203–2211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02203.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings CJ, et al. Over-expression of inducible HSP70 chaperone suppresses neuropathology and improves motor function in SCA1 mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(14):1511–1518. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrucelli L, et al. CHIP and Hsp70 regulate tau ubiquitination, degradation and aggregation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(7):703–714. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neef DW, Jaeger AM, Thiele DJ. Heat shock transcription factor 1 as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(12):930–944. doi: 10.1038/nrd3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broadley SA, Hartl FU. The role of molecular chaperones in human misfolding diseases. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(16):2647–2653. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans CG, Wisén S, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock proteins 70 and 90 inhibit early stages of amyloid beta-(1-42) aggregation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33182–33191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannini B, et al. Molecular mechanisms used by chaperones to reduce the toxicity of aberrant protein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(31):12479–12484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117799109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magrané J, Smith RC, Walsh K, Querfurth HW. Heat shock protein 70 participates in the neuroprotective response to intracellularly expressed beta-amyloid in neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(7):1700–1706. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4330-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen E, Bieschke J, Perciavalle RM, Kelly JW, Dillin A. Opposing activities protect against age-onset proteotoxicity. Science. 2006;313(5793):1604–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.1124646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshino T, et al. Suppression of Alzheimer’s disease-related phenotypes by expression of heat shock protein 70 in mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(14):5225–5234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5478-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rincon-Limas DE, Jensen K, Fernandez-Funez P. Drosophila models of proteinopathies: The little fly that could. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(8):1108–1122. doi: 10.2174/138161212799315894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez-Funez P, de Mena L, Rincon-Limas DE. Modeling the complex pathology of Alzheimer’s disease in Drosophila. Exp Neurol. 2015;274(Pt A):58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: Discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8(10):785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118(2):401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warrick JM, et al. Expanded polyglutamine protein forms nuclear inclusions and causes neural degeneration in Drosophila. Cell. 1998;93(6):939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casas-Tinto S, et al. The ER stress factor XBP1s prevents amyloid-beta neurotoxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(11):2144–2160. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greeve I, et al. Age-dependent neurodegeneration and Alzheimer-amyloid plaque formation in transgenic Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2004;24(16):3899–3906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0283-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]