Abstract

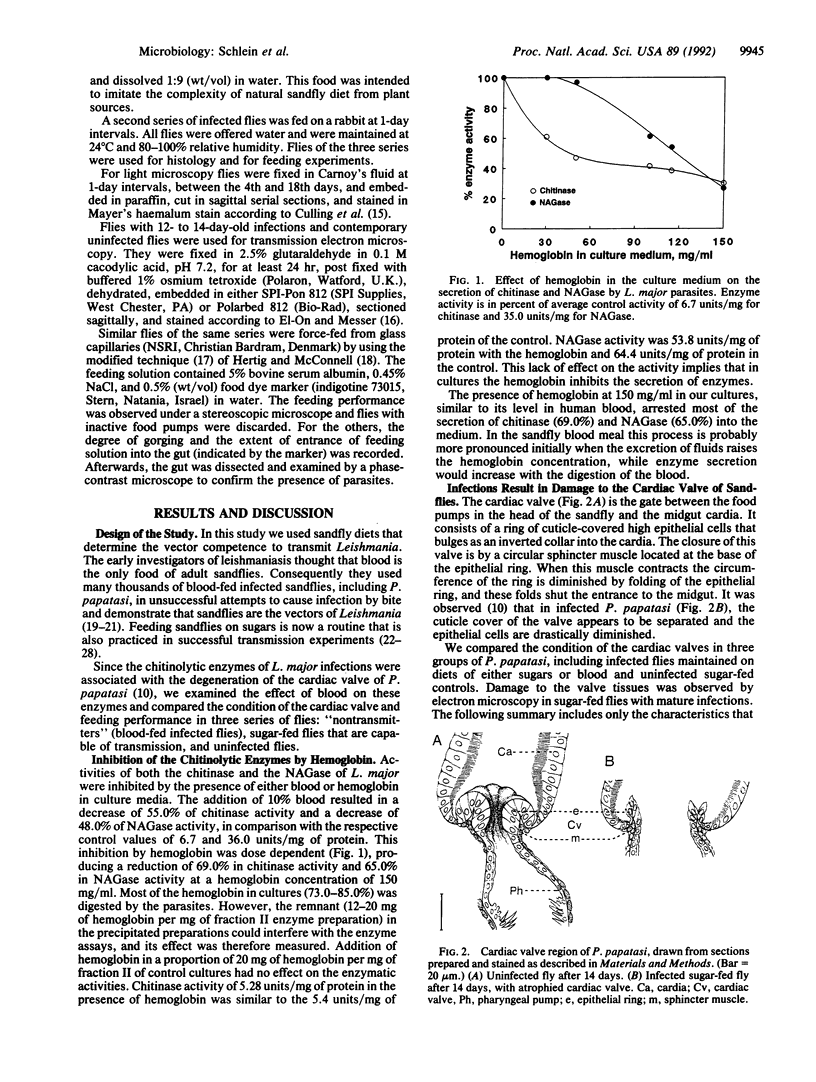

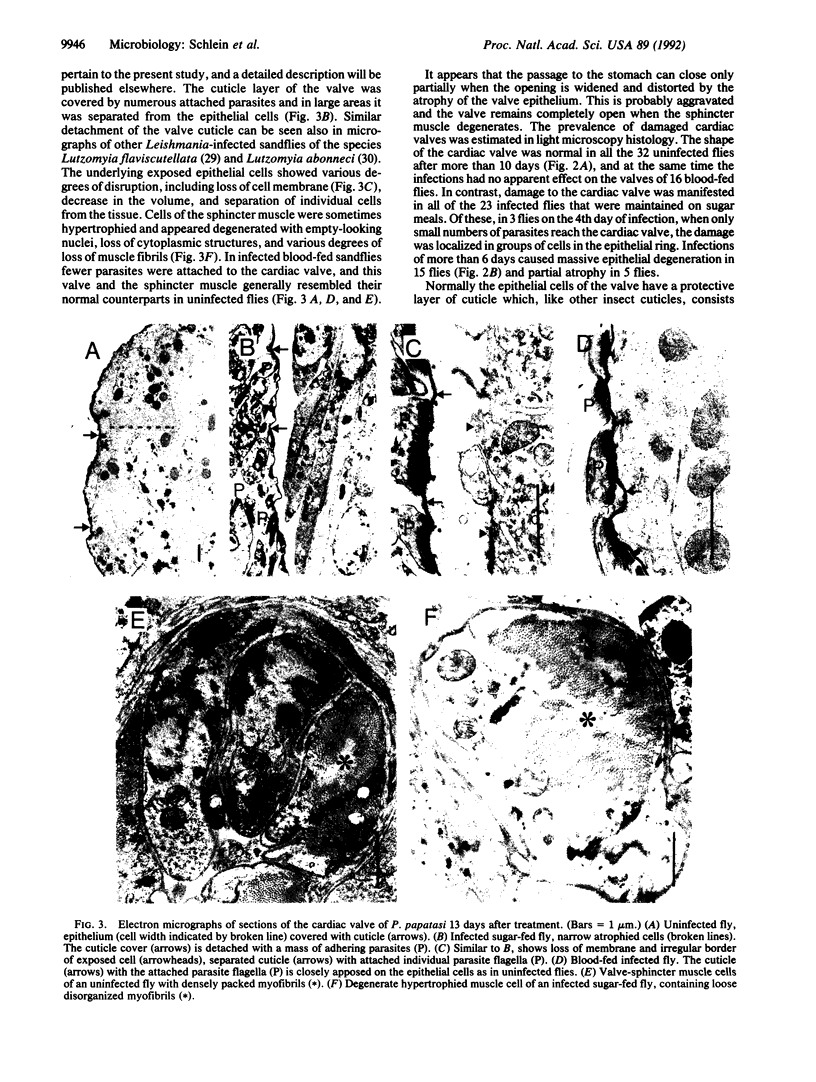

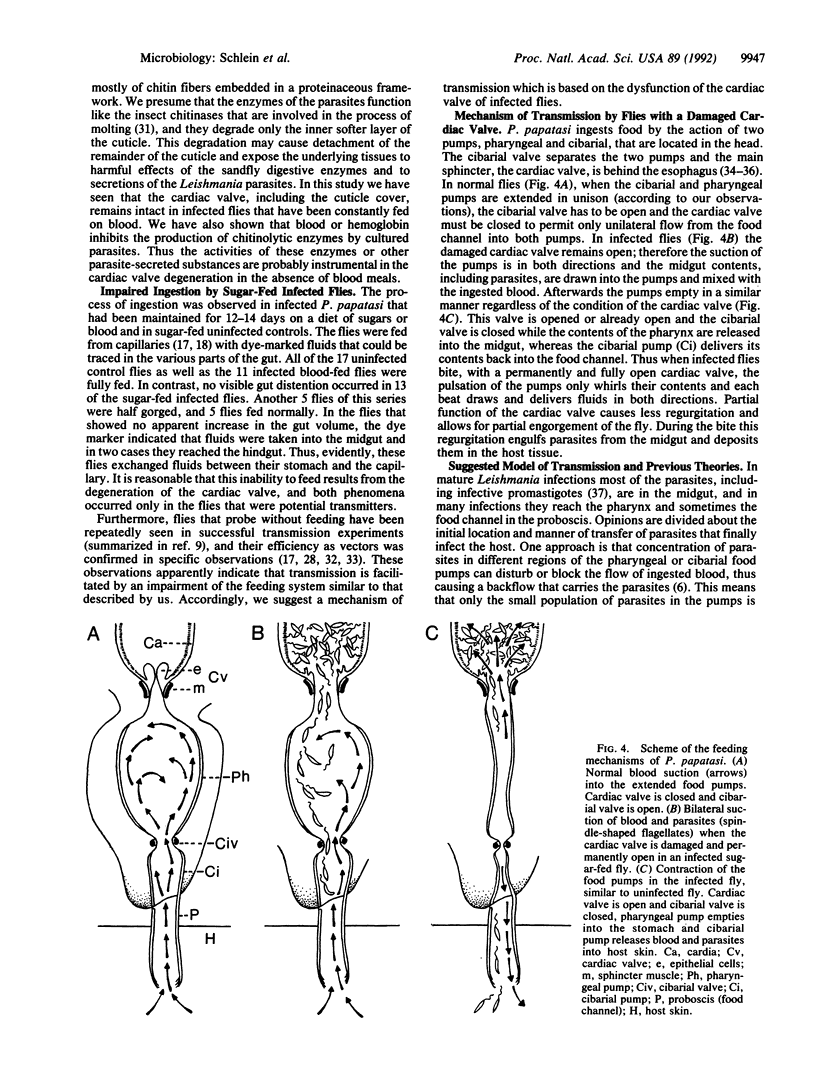

Leishmania parasites are transmitted by the bites of infected female sandflies by a mechanism that has not been clarified. Leishmania infections in the vector develop only in the gut, and the parasites' exit is through the food channel in the proboscis. The problem is how during the bite, when blood flows in, parasites are emitted through the same channel in the opposite direction. It is well documented that infected sandflies maintained on sugar diets are potent vectors, whereas transmission fails after constant feeding on blood. Hence to study the mechanism of transmission, we fed these diets to Phlebotomus papatasi infected with L. major. Histological examination demonstrated that only in the sugar-fed flies did the cuticle lining of the cardiac valve detach and other valve tissues degenerate gradually. The injury of the main valve of the food pumps hindered gorging of most flies when force-fed from capillaries, and they regurgitated the gut contents with fluids from the capillaries. We suggest that infections are caused by parasites regurgitated from the stomach that are deposited in the host tissue. We found that secretion of chitinolytic enzymes by cultured L. major parasites is inhibited by blood or hemoglobin, and hence these enzymes are apparently absent from the blood-fed infected flies, where the cardiac valve appears undamaged. We therefore presume that lysis of the chitin in the cuticle lining of the valve leads to exposure and degeneration of the underlying tissues.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beach R., Kiilu G., Hendricks L., Oster C., Leeuwenburg J. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kenya: transmission of Leishmania major to man by the bite of a naturally infected Phlebotomus duboscqi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1984;78(6):747–751. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(84)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach R., Kiilu G., Leeuwenburg J. Modification of sand fly biting behavior by Leishmania leads to increased parasite transmission. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985 Mar;34(2):278–282. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray R. S. Leishmania. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1974;28(0):189–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.001201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N. T. Leishmaniasis in the Sudan republic. 28. Anatomical studies on Phlebotomus orientalis Parrot and P. papatasi Scopoli (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol. 1967 Apr 25;4(1):50–65. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/4.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-On J., Messer G. Leishmania major: antileishmanial activity of methylbenzethonium chloride. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986 Nov;35(6):1110–1116. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endris R. G., Young D. G., Perkins P. V. Experimental transmission of Leishmania mexicana by a North American sand fly, Lutzomyia anthophora (Diptera: Psychodidae). J Med Entomol. 1987 Mar;24(2):243–247. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERTIG M., MCCONNELL E. EXPERIMENTAL INFECTION OF PANAMANIAN PHLEBOTOMUS SANDFLIES WITH LEISHMANIA. Exp Parasitol. 1963 Aug;14:92–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(63)90014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R., Leaney A. J., Ready P. D., Molyneux D. H. Leishmania in phlebotomid sandflies. IV. The transmission of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis to hamsters by the bite of experimentally infected Lutzomyia longipalpis. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977 Feb 11;196(1122):105–115. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1977.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R., Molyneux D. H. Transmission of leishmaniasis by the bite of phlebotomine sandflies: possible mechanisms. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75(1):152–154. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lainson R., Shaw J. J., Ryan L., Ribeiro R. S., Silveira F. T. Leishmaniasis in Brazil. XXI. Visceral leishmaniasis in the Amazon Region and further observations on the role of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) as the vector. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79(2):223–226. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer P. G., Githure J. I., Anjili C. O., Olobo J. O., Koech D. K., Reid G. D. Experimental transmission of Leishmania major to vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) by bites of Phlebotomus duboscqi (Diptera: Psychodidae). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990 Mar-Apr;84(2):229–232. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90266-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer P. G., Young D. G. Experimental transmission of Leishmania mexicana to hamsters by bites of phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) from the United States. J Med Entomol. 1987 Jul;24(4):458–462. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/24.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux D. H. Vector relationships in the Trypanosomatidae. Adv Parasitol. 1977;15:1–82. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacheck I., Rosenberger R. F. Distribution of autolysins in hyphae of Aspergillus nidulans: evidence for a lipid-mediated attachment to hyphal walls. J Bacteriol. 1978 Sep;135(3):741–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.3.741-747.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozio E., Maroli M., Gradoni L., Gramiccia M. Laboratory transmission of Leishmania infantum to Rattus rattus by the bite of experimentally infected Phlebotomus perniciosus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1985;79(4):524–526. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(85)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L., Lainson R., Shaw J. J., Wallbanks K. R. The transmission of suprapylarian leishmania by the bite of experimentally infected sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae). Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987 Jul-Sep;82(3):425–430. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761987000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks D. L., Perkins P. V. Development of infective stage Leishmania promastigotes within phlebotomine sand flies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1985 May;34(3):456–459. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y., Jacobson R. L., Shlomai J. Chitinase secreted by Leishmania functions in the sandfly vector. Proc Biol Sci. 1991 Aug 22;245(1313):121–126. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y. Sandfly diet and Leishmania. Parasitol Today. 1986 Jun;2(6):175–177. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(86)90150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y., Warburg A., Schnur L. F., Shlomai J. Vector compatibility of Phlebotomus papatasi dependent on differentially induced digestion. Acta Trop. 1983 Mar;40(1):65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters L. L., Modi G. B., Tesh R. B., Burrage T. Host-parasite relationship of Leishmania mexicana mexicana and Lutzomyia abonnenci (Diptera: Psychodidae). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987 Mar;36(2):294–314. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg A., Schlein Y. The effect of post-bloodmeal nutrition of Phlebotomus papatasi on the transmission of Leishmania major. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1986 Sep;35(5):926–930. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P., de Vasconcellos Coelho M. Taxonomy and transmission of Leishmania. Adv Parasitol. 1978;16:1–42. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]