Abstract

Recent studies have revealed that some mammals possess adaptations that enable them to produce vocal signals with much lower fundamental frequency (F0) and formant frequency spacing (ΔF) than expected for their size. Although these adaptations are assumed to reflect selection pressures for males to lower frequency components and exaggerate body size in reproductive contexts, this hypothesis has not been tested across a broad range of species. Here we show that male terrestrial mammals produce vocal signals with lower ΔF (but not F0) than expected for their size in mating systems with greater sexual size dimorphism. We also reveal that males produce calls with higher than expected F0 and ΔF in species with increased sperm competition. This investigation confirms that sexual selection favours the use of ΔF as an acoustic size exaggerator and supports the notion of an evolutionary trade-off between pre-copulatory signalling displays and sperm production.

The acoustic properties of vocal signals generally depend on body size, but in some species males have traits that exaggerate the size conveyed by their vocal signals. Here, Charlton and Reby show that among terrestrial mammals, species with sexual selection for large male body size also have more exaggerated vocal signals for their size.

The acoustic properties of vocal signals generally depend on body size, but in some species males have traits that exaggerate the size conveyed by their vocal signals. Here, Charlton and Reby show that among terrestrial mammals, species with sexual selection for large male body size also have more exaggerated vocal signals for their size.

Identifying the proximate and ultimate factors that underlie the extraordinary diversity of mammal vocal signals is a key objective of animal communication research, and an essential prerequisite for understanding the origins and evolution of human vocal communication1. Body size is known to exert major constraints on the frequency characteristic of animal vocalizations, and as a consequence, size differences between species explain a large proportion of the acoustic diversity of animal vocalizations2,3. Large animals tend to produce lower-pitched calls than smaller ones because they have larger larynges with longer vocal folds that can oscillate periodically at lower frequencies and longer vocal tracts that produce lower resonances (termed formant frequencies in animal vocalizations)4,5,6,7. While this general rule of acoustic allometry is broadly verified across mammal species, several exceptions, typically affecting male vocal signals, have been documented.

For example, some species possess anatomical innovations that enable males to produce abnormally low fundamental frequency (hereafter F0), such as the fleshy vocal pads of roaring cats8, Mongolian and goitered gazelles9,10 or saiga antelope11; hypertrophied larynges in howler and colobus monkeys12, fallow deer13 and hammer-headed bats14, and even an additional, non-laryngeal set of vocal folds in the koala15. In other species, males produce abnormally low formant frequency spacing (ΔF) for their size by extending their vocal tracts using descended and/or mobile larynges10,13,16,17,18,19, additional resonators20,21, or nasal proboscises11,22,23. Because these anatomical adaptations are often only present or disproportionately large in males and involved in the production of mating calls, it is generally assumed that they have evolved via selection pressures for individuals to lower frequency components to broadcast an exaggerated impression of their body size in reproductive contexts1,17,24. However, while this assumption has been verified experimentally within a small number of species25,26,27,28,29, whether sexual selection pressures on male body size drive the evolution of putative acoustic size exaggeration across a wider range of mammalian taxa remains to be investigated.

Although phylogenetically controlled comparative analyses of vocal behaviour exist for birds30,31, previous comparative investigations of mammal vocalizations are either restricted to one mammalian order (for example, Primates3,32,33, Rodentia34) or family (for example, Cervidae35, Felidae36). In this paper we provide the first phylogenetically controlled comparative examination of the selection pressures that lead to acoustic size exaggeration across nine orders and 72 species of terrestrial mammals. We show that the principle of acoustic allometry is generally observed across taxa, and that males from mating systems with strong selection pressures for large male body size produce lower ΔF, but not F0, than expected for their size. Our findings also confirm that selection pressures to exaggerate size are relaxed in male species with larger testes relative to overall body size, indicating that a high level of post-copulatory sperm competition reduces the importance of pre-copulatory acoustic size exaggeration.

Results

Model selection criteria

To test our hypotheses we used phylogenetic generalized least-squares (PGLS) regressions that simulated five different evolutionary scenarios. To select the best supported PGLS regression models, we started with a ‘global' model including male body mass, habitat (arboreal or terrestrial), call-type (sexual or nonsexual), mating system (polygynous, monogamous, polyandrous, promiscuous or variable) and sexual size dimorphism or relative testes size depending on the hypothesis that was being tested, and iterated through all variable combinations to explain variation in male F0 and ΔF for each of the five different evolutionary scenarios. All models considered included log10 male body mass to control for body size differences across species and a model selection criteria based on the Akaike's Information Criteria corrected for sample size (AICc) was used, in which the model having the lowest AICc value is chosen37 (Supplementary Tables 1–6).

Male body size versus F0 and ΔF across species

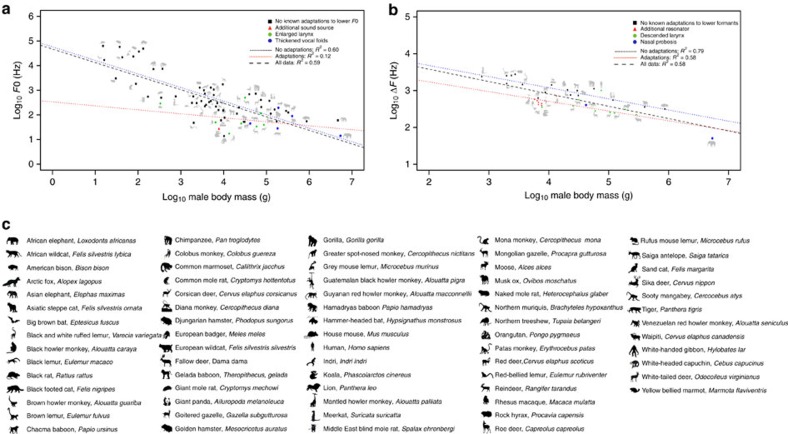

Our model selection approach indicated that the best supported PGLS regression models to test for the effect of male body size on male F0 and ΔF were a Brownian motion model of evolution using Pagel's lambda (λ) to model the covariance structure (BM+λ) and a pure Brownian motion model (BM) with habitat included as a covariate, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The PGLS regressions showed that greater male body mass predicted lower log10 F0 (estimate±s.e.=−0.50±0.09, λ=0.87, t4,65=−5.92, P<0.001) and log10 ΔF (estimate±s.e.=−0.34±0.05, t4,32=−6.19, P<0.001), confirming that the expected acoustic allometry exists across species (Fig. 1). We also found that arboreal species produced significantly lower log10 ΔF than other terrestrial mammals (estimate±s.e.=0.30±0.11, t4,32=3.10, P=0.008).

Figure 1. Relationship between male body mass and acoustic variables across terrestrial mammal species.

The scatterplots show the relationship between (a) log10 male body mass and log10 F0 and (b) log10 male body mass and log10 ΔF. The dotted lines represent the slope and intercept of phylogenetic generalized least-squares regressions of log10 male body mass on log10 F0 (a) and log10 male body mass and habitat on log10 ΔF. (b) In both plots, the blue dotted line shows the relationship between male body mass and acoustic features for species without known adaptations to lower frequency components of calls, the red dotted line shows the relationship between male body mass and acoustic features for species that are known to possess adaptations to lower frequency components of calls, and the black dotted line shows the relationship between male body mass and acoustic features for all the species in the data set (plot A: PGLS regression, N=67, P<0.001; plot B: PGLS regression, N=35, P<0.001). In both plots a black square indicates species with no known adaptations to lower frequency components. A red triangle denotes species with additional sound sources and resonators in plots A and B, respectively, a green circle signifies species with an enlarged larynx in plot A and species with a descended larynx in plot B, and a blue circle represents species with thickened vocal folds in plot A and a nasal proboscis in plot B. A key for the icons representing each of the mammal species is also provided in c.

Male size dimorphism versus F0 and ΔF across species

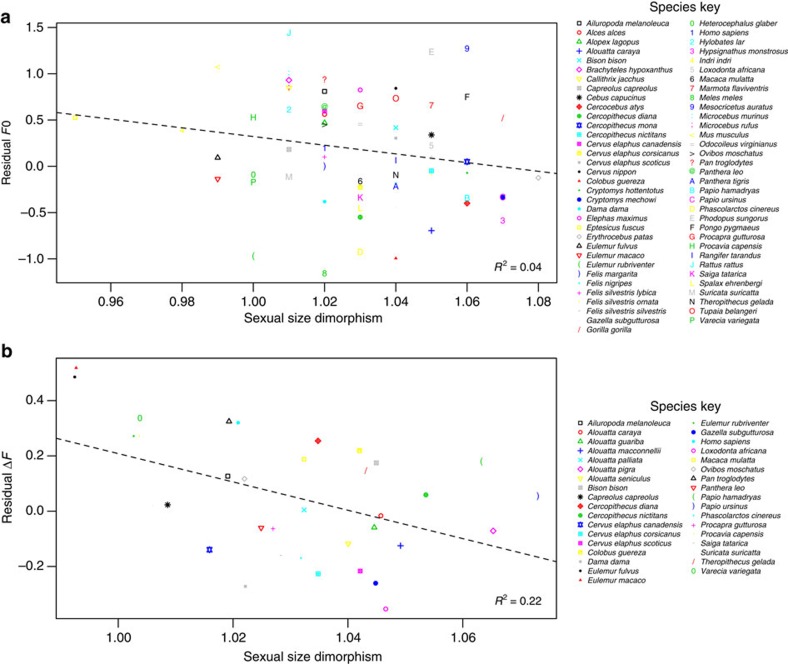

A BM+λ model of evolution including log10 male body mass as a covariate best explained the relationship between size dimorphism and F0 (Supplementary Table 3). This model showed that size dimorphism was not significantly related to log10 F0 (estimate±s.e.=−4.93±3.11, λ=0.87, t5,64=−1.58, P=0.119) (Fig. 2a). The relationship between size dimorphism and ΔF was best explained by a pure Brownian motion model of evolution with log10 male body mass and habitat included as covariates (Supplementary Table 4). This model revealed that species with greater male sexual size dimorphism produced sexual calls with lower log10ΔF (estimate±s.e.=−3.58±1.21, t5,31=−2.97, P=0.006) (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Table 4), indicating that males produce vocal signals with lower than expected ΔF for their size in mating systems with sexual selection pressures for large male body size.

Figure 2. Relationship between sexual size dimorphism and acoustic variables across terrestrial mammal species.

The scatterplots show the relationship between (a) sexual size dimorphism and residual F0, and (b) sexual size dimorphism and residual ΔF. Residual F0 and ΔF refer to the residuals obtained from PGLS regressions of log10 male body mass on log10 F0 and log10 male body mass and habitat on log10 ΔF, respectively. For each plot, the dotted line represents the slope and intercept of the PGLS model regressions (plot A: N=67, P=0.119; plot B: N=35, P=0.006). R2 values are given in the bottom right-hand corner.

Sperm competition versus F0 and ΔF across species

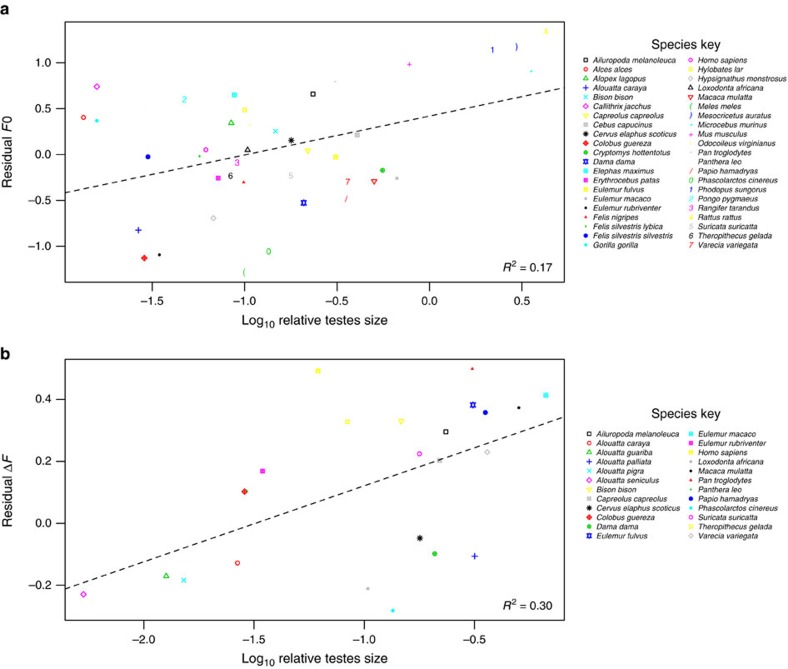

The best supported models to examine the effect of post-copulatory sperm competition on F0 and ΔF were an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) model and a BM+λ model of evolution, respectively (lowest AICc values, see Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Both models included log10 male body mass as a covariate. The relationship between relative testes size and male acoustic values in the 42 mammal species for which acoustic and testes data were available, revealed that log10 relative testes size was positively correlated with log10 F0 (estimate±s.e.=0.39±0.16, α=0.02, t5,39=2.50, P=0.017) (Fig. 3a). We also found that log10 relative testes size was positively correlated with log10 ΔF (estimate±s.e.=0.09±0.02, λ=1.02, t5,21=4.04, P<0.001) (Fig. 3b) for the 24 species with available acoustic and testes data. These findings indicate that species with larger testes relative to body size produce calls with higher F0 and ΔF.

Figure 3. Relationship between relative testes size and acoustic variables across terrestrial mammal species.

The scatterplots show the relationship between (a) log10 relative testes size and residual F0, and (b) log10 relative testes size and residual ΔF. Residual F0 and ΔF refer to the residuals obtained from PGLS regressions of log10 body mass on log10 F0 and log10 ΔF, respectively. The dotted line represents the slope and intercept of the PGLS model regressions (plot A: N=42, P=0.017; plot B: N=24, P<0.001). R2 values are given in the bottom right-hand corner.

Discussion

Several interesting results emerge from this phylogenetically controlled examination of the link between acoustic variation in mammal calls and putative pre- and post-copulatory sexual selection pressures in a wide range of mammalian species. First, the key predictions of the acoustic allometry are confirmed: males from larger species produce calls with lower F0 and lower formants (Fig. 1). The analysis also reveals that males of arboreal species give sexual calls with lower ΔF than other terrestrial mammals. This finding is consistent with the notion that low frequency calls given from relatively higher positions are less affected by ground interference38 and/or that lower frequencies propagate best in forest environments39. Interestingly, the relationship between body mass and F0 across nine orders of terrestrial mammals (Fig. 1a) indicates that laryngeal enlargement and the concomitant lengthening of the vocal folds is a more effective way of lowering F0 than thickening the vocal folds to increase their mass40, and suggests that vocal pads may primarily support the production of high-amplitude low-F0 sexual calls, rather than lowering F0 per se.

A very close relationship between male ΔF and body mass is also revealed (Fig. 1b), illustrating how strong anatomical constraints affect the correlations between vocal tract length, skull size and overall body size41. When species without anatomical adaptations to lower formant frequencies are considered alone, the relationship is even stronger (R2 of 0.79) (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, species with specific anatomical and/or behavioural adaptations that allow them to escape these constraints follow a separate downward shifted trend that still, nevertheless, represents a close relationship between ΔF and body mass (R2 of 0.58) (Fig. 1b). This is suggestive of secondary constraints acting on size exaggerators, such as the sternum preventing any further laryngeal descent16 and/or other skeletal structures that limit further enlargement of acoustic resonators, which in turn limits the extent of size exaggeration and maintains a parallel allometric relationship between ΔF and body mass. Of particular interest are species that are not known to possess adaptations to lower F0 or formants yet still produce call frequencies which fall way below the expected acoustic allometry (for example, European badgers and mole rats). Future studies should further investigate these species' vocal anatomy in conjunction with the selection pressures acting on their vocal communication systems.

When investigating the effect of sexual selection for large male body size we found that sexual size dimorphism did not predict F0 across taxa. The lack of a relationship between sexual size dimorphism and F0 is not surprising, as F0 is generally a poor predictor of adult male body mass within species5. Our results, therefore, support the hypothesis that sexual selection does not systematically favour the use of F0 as an acoustic size exaggerator. In contrast, sexual size dimorphism was negatively correlated to formant frequency spacing, with greater male sexual size dimorphism resulting in male sexual calls with lower than expected ΔF. This relationship indicates that sexual selection for increased male body size is likely to be a key force leading to the evolution of anatomical and/or behavioural adaptations that enable male callers to acoustically exaggerate their apparent body size via formant lowering. Although ΔF is known to function as a size exaggerator in some mammalian species25,26,27,28,29, the findings of the current study constitute the first demonstration that sexual selection is a key driver of acoustic variability across mammals.

Our phylogenetic analysis also reveals that male mammals with relatively large testes produced calls with higher ΔF, suggesting that pre-copulatory sexual selection pressures to acoustically exaggerate body size are relaxed in species where sperm competition predominates. This result confirms the evolutionary trade-off between acoustic size exaggeration and testes size revealed by a recent study of sexual calls in howler monkeys20. The fact that F0 is also lower in species with relatively smaller testes is consistent with previous observations that, while lower F0 may not function as a reliable cue to body size within mammal species, it can indicate higher testosterone levels42,43, threat potential44 and dominance45,46, and hence, remains an important, sexually selected component of pre-copulatory signalling in mammals. Indeed, recent findings in anthropoid primates show how sexual dimorphism in F0 increases during evolutionary transitions towards polygyny and decreases during transitions towards monogamy33, further emphasizing that F0 is a sexually selected component of mammal vocalizations.

Finally, our comparative investigation provides a useful background for understanding the selection pressures contingent on our own species' vocal communication. Although male humans do not appear to possess an exclusively sexual call, it is now well established that F0 and formants are sexually selected components of the male voice that play a role in mate choice47,48 and intra-sexual competition44,46. However, unlike other primates, adult humans have a descended larynx that results in a disproportionately long pharyngeal cavity1. Moreover, a secondary descent of the larynx that only affects adult men at puberty, and enables them to produce even lower formant frequencies, has been attributed to sexual selection for size exaggeration49. Yet surprisingly, the observed ΔF of male humans is quite far above, rather than below the value predicted from the acoustic allometry (Fig. 1b), indicating that the human male vocal tract is in fact shorter than expected for a male terrestrial mammal that weighs around 75 kg (the average weight of a male human50). We suggest that selection pressures to decrease facial size may have counter-balanced sexual selection pressures to exaggerate apparent body size, and resulted in the relative overall shortening of the human vocal tract revealed by our comparative investigation. Indeed, selection pressures linked to speech production, thermoregulation or locomotion51 and facilitated by tool use and meat eating52, are generally assumed to have led to the 1:1 ratio of the oral cavity relative to the pharyngeal cavity that is considered to be a crucial prerequisite for the evolution of complex speech articulation1,53. Our phylogenetically controlled investigation, therefore, not only reveals how sexual selection for acoustic size exaggeration drives the anatomical and acoustical diversification of terrestrial mammal vocal communication systems, but also highlights the importance of the comparative approach for providing the background necessary to fully understand the origins and evolution of our own species' vocal apparatus1.

Methods

Data sources

To test our hypotheses, we collated acoustic data on mean F0 from 67 male species across 52 genera, and mean formant frequency values from 35 male species across 25 genera from the literature (Supplementary Table 7). We restricted the data set to adult terrestrial mammals and noted whether vocalizations function as sexual calls (that is, those that are purported to have functional relevance during intra-sexual or inter-sexual assessment). This allowed us to enter call-type (sexual or nonsexual) as a covariate in the analysis, and control for any differences in the acoustic structure generated by males using different modes of sound production and/or adopting different calling postures exclusively in sexual calls (such as the use of non-laryngeal sources and/or vocal tract elongation by laryngeal retraction or neck stretching). Humans were included on the basis that F0 and formants in the male voice have also been shaped by sexual selection46,47,48.

In cases where mean F0 and formant frequency values were not directly reported in papers, the acoustic values were obtained by contacting the lead authors of the respective studies. For five species, mean F0 was estimated by taking the average of the minimum and maximum reported values3,32. To calculate formant frequency spacing (ΔF), we used the first two to nine formant frequencies (mean=5) and the regression method of Reby & McComb54, in which the formant frequency values are plotted against those that would be expected if the vocal tract was a straight uniform tube closed at one end (the glottis) and open at the other (the mouth). This regression method is an accurate way to estimate ΔF in species with unevenly spaced formants (as is commonly the case in mammals17,22,54).

Data on male acoustic features and body mass were obtained from the same published source for 39 out of 67 taxa for the F0 data and 15 out of 35 taxa for the formant data. In addition, because the physical environment also shapes the acoustic features of vocal signals32,38,39, we collected data on the typical habitat for each of the species in our comparative analyses from the Encyclopaedia of Life website (http://eol.org/) to control for this factor in the analyses. We also collected data on the mating system of each species in the analysis from the Animal Diversity Website (http://animaldiversity.org/). If body weight data was not available from the acoustic studies we referred to the CRC handbook of mammalian body masses55 and the PANTHERIA v.1 database56. We did not collect acoustic and body weight data for farmed or domestic animals (for example, cats, dogs, horses, sheep, goats) that are often intensely bred and therefore subject to strong artificial selection.

The degree of sexual size dimorphism was used as an indicator of the intensity of sexual selection pressures acting on male body size in a given species57,58 with greater values indicative of selection pressures for larger male body size. Sexual size dimorphism was calculated for each species by dividing log10 male body weight by log10 female body weight (to convert a cubic measure to a linear measure of size57,58). Body mass data were taken from several sources (Supplementary Table 7); however, care was always taken to match male and female body mass data from the same population when calculating sexual size dimorphism. Relative testis size was used as an index of post-copulatory sexual selection pressures20,59,60. Post-copulatory sexual selection is prevalent in promiscuous species that live at high population densities and typically manifests itself as sperm competition, which in turn leads to larger male testes relative to overall body size61. Relative testes size is thus assumed to be a reliable index of the degree of sperm competition experienced by males within a species20,59,60. We calculated relative testes size for each species as the total mass of both testis in grams divided by the overall body mass in grams, rather than generating residuals of male testes mass regressed on body mass across taxa59,62. Male body and testes mass data from the same population were collected for 42 species for the F0 analyses and 24 species for the ΔF analyses (Supplementary Table 7). In five cases where data on testes mass were not directly available, the mass in grams was calculated by multiplying the volume in mm3 by 1.02 (ref. 60).

Statistical analyses

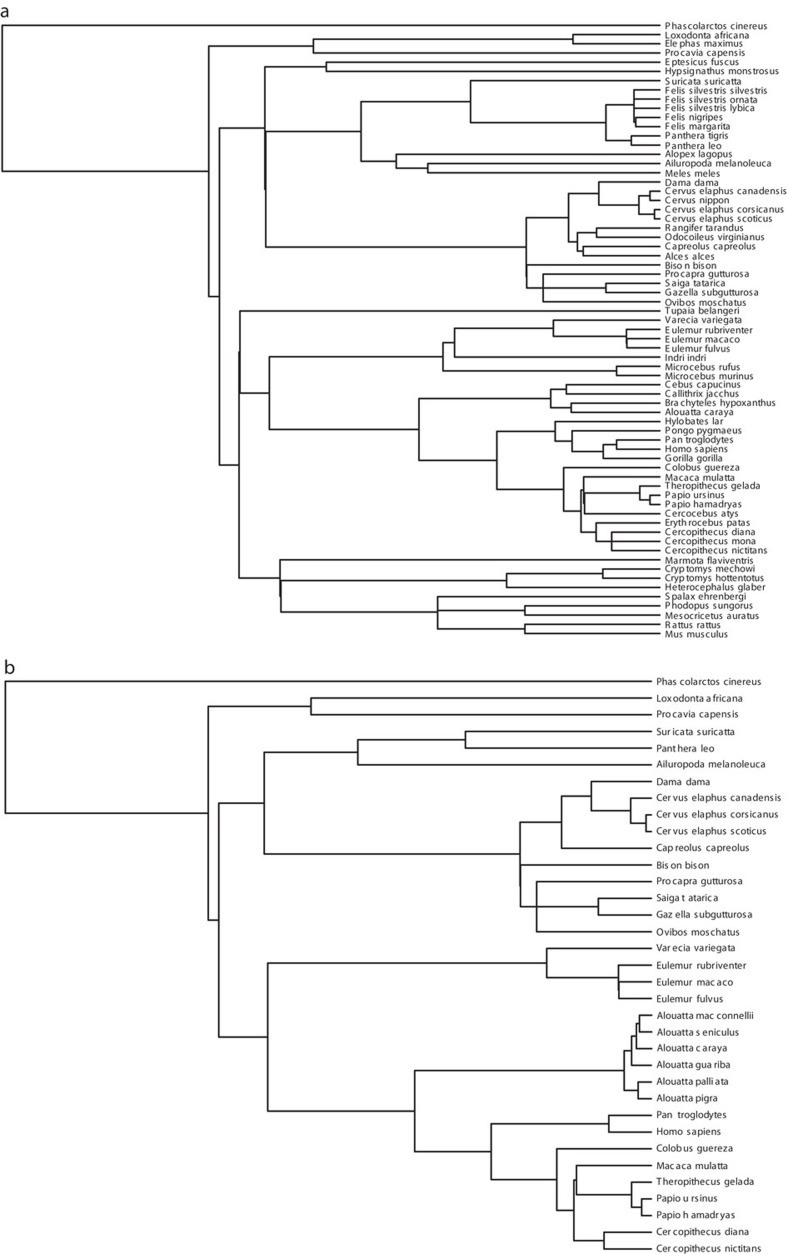

Due to shared phylogenetic history, data from different species cannot be treated as statistically independent20,57,58,63. Accordingly, we conducted PGLS regressions using the gls function (nlme package) in R64 to test our hypotheses. To control for the confounding effects of shared phylogenetic ancestry we used untransformed branch lengths and splitting dates from a recent molecular phylogeny of mammals65. Additional molecular phylogenies were used to improve resolution within the Cervinae66, Alouatta67 and Cercopithecinae68 species. Figure 4 depicts the phylogenies used to control for shared ancestry among species in each of the separate analyses.

Figure 4. The phylogenies used to control for shared ancestry between different species.

PGLS regressions testing the effect of size dimorphism and relative testes size on F0 used the phylogeny in a; and those testing the effect of size dimorphism and relative testes size on ΔF used the phylogeny in b.

In addition, for each formal hypothesis we computed five PGLS regression models that were designed to test a different evolutionary scenario, and chose the most parsimonious model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion statistic corrected for sample size (AICc)37,69. The different models were an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) model of evolution, a non-phylogenetic ordinary least-squares (OLS) model, a pure Brownian motion (BM) model, and two restricted maximum-likelihood (REML) Brownian motion models that allow parameters to vary with the strength of the phylogenetic signal, a Brownian motion+Pagel's lambda (BM+λ) and a Brownian motion+Grafen's rho (BM+ρ) model. The OLS model assumes phylogenetic independence, the BM model assumes a Brownian motion model of trait evolution (or pure Random Walk), the OU model uses alpha (α) to test the strength of stabilizing selection: α=0 is equivalent to pure Brownian motion and larger values of α indicate stronger stabilizing selection, the BM+λ model allows us to test if the best model falls between pure Brownian motion (λ=1) and phylogenetic independence (λ=0), and the BM+ρ model tests the rate of evolutionary change, with ρ<1 indicating relatively more gradual recent evolution, ρ>1 relatively faster recent evolution, and ρ=0 indicates a star phylogeny, generated by a recent population expansion event from a common ancestor.

For each PGLS regression, the dependent variable was the acoustic measure (log10 F0 or log10ΔF). Log10 transformed male body mass (in grams) was entered as a covariate to control for body size differences across taxa, and the species-typical habitat (arboreal versus terrestrial), the call-type from which the acoustic data was derived (sexual or nonsexual), and the mating system for each species (monogamous, polygynous, polyandrous, promiscuous or variable) were also entered into a global PGLS model to control for these factors. For each formal hypothesis, we then used the ‘dredge' function in R (MuMIn' package) to iterate through all variable combinations in the global model to explain variation in log10 F0 and log10ΔF, and chose the model with the lowest AICc value69. The acoustic variables F0 and ΔF, and relative testes size were log10 transformed to achieve a normal data distribution. All other variables were normally distributed.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Supplementary Table 7 and also from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Charlton, B.D. & Reby, D. The evolution of acoustic size exaggeration in terrestrial mammals. Nat. Commun. 7:12739 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12739 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Tables 1-7 and Supplementary References.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Barelli, Jack Bradbury, Tecumseh Fitch, Roland Frey, Marco Gamba, Tara Harris, Lee Koren, Simon Townsend, Ilya Volodin, lena Volodin and Megan Wyman for providing unpublished data and/or clarification on some of the acoustic data.

Footnotes

Author contributions B.D.C. and D.R. conceived and designed the study; B.D.C. and D.R. wrote the manuscript; B.D.C. collated the data and conducted the analyses.

References

- Fitch W. T. The Evolution of Language Cambridge University Press (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher N. H. A simple frequency-scaling rule for animal communication. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115, 2334–2338 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M. D. The evolution of nonhuman primate vocalisations: effects of phylogeny, body weight and social context. Am. Nat. 142, 528–542 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fant G. Acoustic Theory of Speech Production Mouton (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. & Reby D. The contribution of source–filter theory to mammal vocal communication research. J. Zool. 280, 221–236 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W. T. Vocal tract length and formant frequency dispersion correlate with body size in rhesus macaques. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 1213–1222 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titze I. R. Principles of Voice Production Prentice Hall (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Klemuk S., Riede T., Walsh E. & Titze I. Adapted to roar: functional morphology of tiger and lion vocal folds. PLoS ONE 6, e27029 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey R. & Riede T. Sexual dimorphism of the larynx of the Mongolian gazelle (Procapra gutturosa Pallas, 1777) (Mammalia, Artiodactyla, Bovidae). Zool. Anz. 242, 33–62 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Frey R., Volodin I., Volodina E., Soldatova N. V. & Juldaschev E. T. Descended and mobile larynx, vocal tract elongation and rutting roars in male goitred gazelles (Gazella subgutturosa Güldenstaedt, 1780). J. Anat. 218, 566–585 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey R., Volodin I. & Volodina E. A nose that roars: anatomical specializations and behavioural features of rutting male saiga. J. Anat. 211, 717–736 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixson A. F. Primate Sexuality: Comparative Studies of the Prosimians, Monkeys, Apes, and Humans Oxford University Press (2012). [Google Scholar]

- McElligott A. G., Birrer M. & Vannoni E. Retraction of the mobile descended larynx during groaning enables fallow bucks (Dama dama) to lower their formant frequencies. J. Zool. 270, 340–345 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury J. Lek mating behavior in the hammer–headed bat. Z. Tierpsychol. 45, 225–255 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B. et al. Koalas use a novel vocal organ to produce unusually low-pitched mating calls. Curr. Biol. 23, R1035–R1036 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W. T. & Reby D. The descended larynx is not uniquely human. Proc. Biol. Sci. 268, 1669–1675 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B. et al. Cues to body size in the formant spacing of male koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) bellows: honesty in an exaggerated trait. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 3414–3422 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissengruber G. E., Forstenpointner G., Peters G., Kubber-Heiss A. & Fitch W. T. Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and domestic cat (Felis silvestris f. catus). J. Anat. 201, 195–209 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey R. et al. Mobile larynx in Mongolian gazelle: retraction of the larynx during rutting barks in male Mongolian gazelle (Procapra gutturosa Pallas, 1777). J. Morphol. 269, 1223–1237 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. C. et al. Evolutionary trade-off between vocal tract and testes dimensions in howler monkeys. Curr. Biol. 25, 2839–2844 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T. R., Fitch W. T., Goldstein L. M. & Fashing P. J. Black and white colobus monkey (Colobus guereza) roars as a source of both honest and exaggerated information about body mass. Ethology 112, 911–920 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- McComb K., Reby D., Baker L., Moss C. & Sayialel S. Long-distance communication of acoustic cues to social identity in African elephants. Anim. Behav. 66, 317–329 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Sanvito S., Galimberti F. & Miller E. H. Vocal signalling in male southern elephant seals is honest but imprecise. Anim. Behav. 73, 287–299 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Charlton B. D. & Reby D. in Vertebrate Sound Production and Acoustic Communication Springer Handbook of Auditory Research eds Suthers R. A., Fitch W. T., Fay R. R., Popper A. Springer International Publishing (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B., Ellis W., Brumm J., Nilsson K. & Fitch W. Female koalas prefer bellows in which lower formants indicate larger males. Anim. Behav. 84, 1565–1571 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B., Reby D. & McComb K. Female red deer prefer the roars of larger males. Biol. Lett. 3, 382–385 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton B., Whisson D. & Reby D. Free-ranging male koalas use size-related variation in formant frequencies to assess rival males. PLoS ONE 8, e70279 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reby D. et al. Red deer stags use formants as assessment cues during intrasexual agonistic interactions. Proc. Biol. Sci. 272, 941–947 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher B. J., Briefer E. F. & McElligott A. G. Intrasexual selection drives sensitivity to pitch, formants and duration in the competitive calls of fallow bucks. BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 149 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podos J. Correlated evolution of morphology and vocal signal structure in Darwin's finches. Nature 409, 185–188 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli S. & Tubaro P. L. Body mass and habitat correlates of song structure in a primitive group of birds. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 77, 423–430 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Mitani J. C. & Stuht J. The evolution of nonhuman primate loud calls: acoustic adaptation for long-distance transmission. Primates 39, 171–182 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A. et al. Sexual selection on male vocal fundamental frequency in humans and other anthropoids. Proc. Biol. Sci. 283, 20152830 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Navas V. & Blumstein D. T. The effect of body size and habitat on the evolution of alarm vocalizations in rodents. Biol. J. Linnean Soc 118, 745–751 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Cap H., Deleporte P., Joachim J. & Reby D. Male vocal behavior and phylogeny in deer. Cladistics 24, 917–931 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters G., Baum L., Peters M. & Tonkin-Leyhausen B. Spectral characteristics of intense mew calls in cat species of the genus Felis (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae). J. Ethol. 27, 221–237 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K. D. & Anderson D. R. in Model Selection and Multimodal Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach 2nd edn Springer-Verlag (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Embleton T. F. W. Tutorial on sound propagation outdoors. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 100, 31–48 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Wiley R. H. & Richards D. G. Physical constraints on acoustic communication in atmosphere - implications for evolution of animal vocalizations. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 3, 69–94 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Titze I. R. Vocal fold mass is not a useful quantity for describing F0 in vocalization. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 54, 520–522 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W. T. Skull dimensions in relation to body size in nonhuman mammals: the causal bases for acoustic allometry. Zool. Anal. Complex Syst. 103, 40–58 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Dabbs J. M. & Mallinger A. High testosterone levels predict low voice pitch among men. Pers. Individ. Dif. 27, 801–804 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Cartei V., Bond R. & Reby D. What makes a voice masculine: physiological and acoustical correlates of women's ratings of men's vocal masculinity. Horm. Behav. 66, 569–576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Apicella C. L. & Cardenas R. A. Masculine voices signal men's threat potential in forager and industrial societies. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 601–609 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannoni E. & McElligott A. G. Low frequency groans indicate larger and more dominant fallow deer (Dama dama) males. PLoS ONE 3, e3113 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A., Hodges C. R., Cardenas R. A. & Gaulin S. J. C. Men's voices as dominance signals: vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence dominance attributions among men. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 340–344 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg D. R. et al. Menstrual cycle, trait estrogen level, and masculinity preferences in the human voice. Horm. Behav. 49, 215–222 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts D. A. Mating context and menstrual phase affect women's preferences for male voice pitch. Evol. Hum. Behav. 26, 388–397 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W. T. & Giedd J. Morphology and development of the human vocal tract: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 1511–1522 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisanski K. et al. Voice parameters predict sex-specific body morphology in men and women. Anim. Behav. 112, 13–22 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D. E. The Evolution of the Human Head Havard University Press (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Zink K. D. & Lieberman D. E. Impact of meat and lower palaeolithic food processing techniques on chewing in humans. Nature 531, 500–503 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman P., Klatt D. H. & Crelin E. S. Phonetic ability and related anatomy of the newborn and adult human, Neanderthal man, and the chimpanzee. Am. Anthropol. 74, 287–307 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Reby D. & McComb K. Anatomical constraints generate honesty: acoustic cues to age and weight in the roars of red deer stags. Anim. Behav. 65, 519–530 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Silva M. & Downing J. A. CRC Handbook of Mammalian Body Masses CRC Press (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. E. et al. PanTHERIA: a species-level database of life history, ecology, and geography of extant and recently extinct mammals. Ecology 90, 2648–2648 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Gage M. J. G., Parker G. A., Nylin S. & Wiklund C. Sexual selection and speciation in mammals, butterflies and spiders. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269, 2309–2316 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow E. H. & Fricke C. Sexual selection and the risk of extinction in mammals. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271, 2395–2401 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsbury C. D. Genetic patterns of paternity and testes size in mammals. PLoS ONE 5, e9581–e9587 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossa G., Soulsbury C. D., Baker P. J. & Harris S. Sperm competition and the evolution of testes size in terrestrial mammalian carnivores. Funct. Ecol. 22, 655–662 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Dixson A. F. Observations on the evolution of the genitalia and copulatory behaviour in male primates. J. Zool. 213, 423–443 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton R. P. On the misuse of residuals in ecology: regression of residuals vs. multiple regression. J. Anim. Ecol. 71, 542–545 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P. H. & Pagel M. D. The Comparative Method in Evolutionary Biology Oxford University Press (1991). [Google Scholar]

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Development Core Team, 2008).

- Bininda-Emonds O. R. P. et al. The delayed rise of present-day mammals. Nature 446, 507–512 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitra C., Fickel J., Meijaard E. & Groves C. Evolution and phylogeny of old world deer. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 33, 880–895 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Ortiz L. et al. Molecular systematics and biogeography of the Neotropical monkey genus, Alouatta. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 26, 64–81 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinner D., Wertheimer J., Liedigk R., Groeneveld L. F. & Roos C. Baboon phylogeny as inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 150, 133–140 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley N. M., Drury J. P., Garland T. & Blumstein D. T. Vivid birds do not initiate flight sooner despite their potential conspicuousness. Curr. Zool. 61, 773–780 (2015). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1-7 and Supplementary References.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in Supplementary Table 7 and also from the corresponding author upon request.