Abstract

Purpose

PD-1 inhibitors are established agents in the management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); however, only a subset of patients derives clinical benefit. To determine the activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors within clinically-relevant molecular subgroups, we retrospectively evaluated response patterns among EGFR-mutant, ALK-positive, and EGFR wild-type/ALK-negative patients.

Experimental Design

We identified 58 patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Objective response rates (ORRs) were assessed using RECIST v1.1. PD-L1 expression and CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

Results

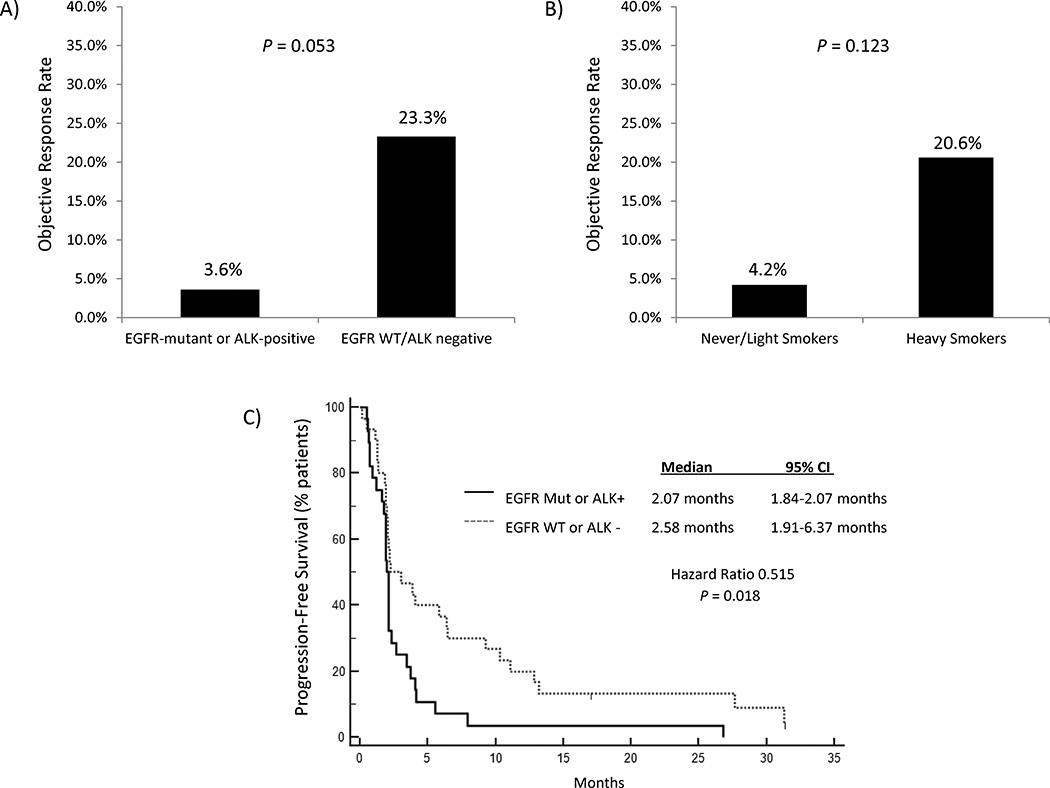

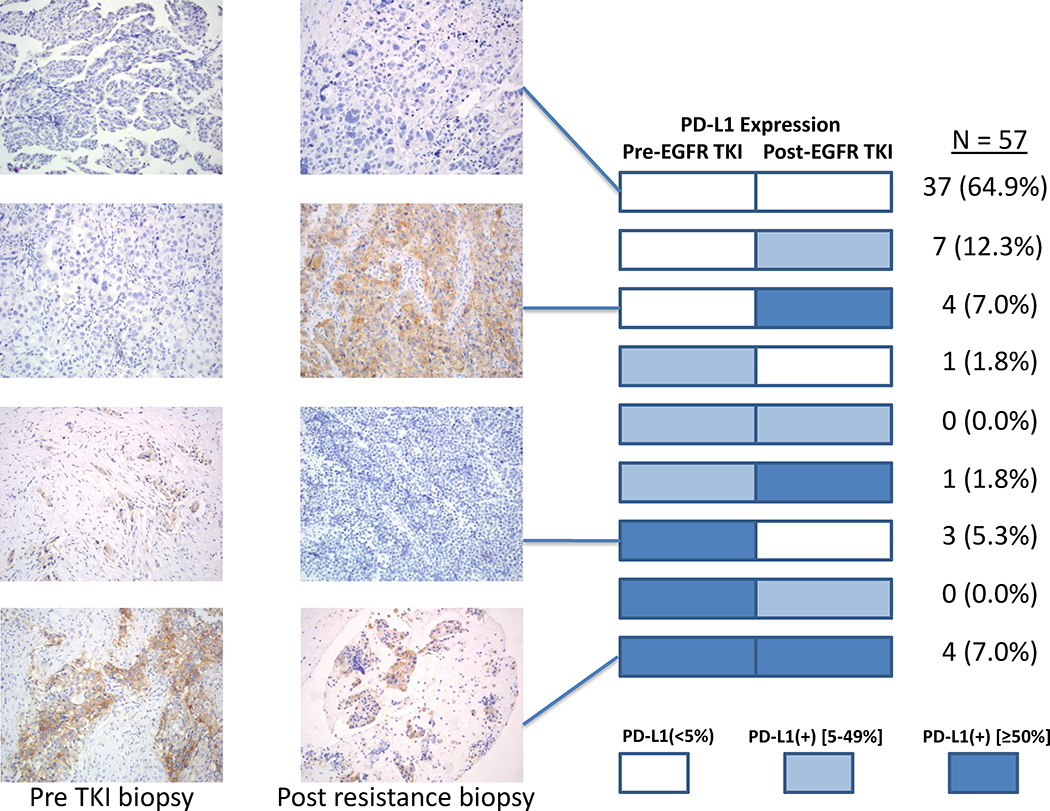

Objective responses were observed in 1/28 (3.6%) EGFR-mutant or ALK-positive patients versus 7/30 (23.3%) EGFR wild-type and ALK-negative/unknown patients (P = 0.053). The ORR among never- or light- (≤10 pack years) smokers was 4.2% versus 20.6% among heavy smokers (P = 0.123). In an independent cohort of advanced, EGFR-mutant (N=68) and ALK-positive (N=27) patients, PD-L1 expression was observed in 24%/16%/11% and 63%/47%/26% of pre-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) biopsies using cutoffs of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50% tumor cell staining, respectively. Among EGFR-mutant patients with paired, pre- and post-TKI resistant biopsies (N=57), PD-L1 expression levels changed after resistance in 16 (28%) patients. Concurrent PD-L1 expression (≥5%) and high levels of CD8+ TILs (grade ≥2) were observed in only 1 pre-treatment (2.1%) and 5 resistant (11.6%) EGFR-mutant specimens, and was not observed in any ALK-positive, pre- or post-TKI specimens.

Conclusion

NSCLCs harboring EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangements are associated with low ORRs to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Low rates of concurrent PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs within the tumor microenvironment may underlie these clinical observations.

Keywords: PD-1 Inhibitors, EGFR, ALK, Non-small cell lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Two major treatment paradigms have recently emerged in the management of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): targeted therapies and immunotherapy. The former relies on stratification and treatment based upon genetic alterations in oncogenic drivers, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Despite the impressive activity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in these subgroups (1, 2), resistance almost invariably develops (3). Furthermore, a significant proportion of patients with NSCLC do not have genetic alterations that are currently targetable with FDA-approved therapies (4).

More recently, monoclonal antibodies targeting the programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor and its ligand (PD-L1), have demonstrated impressive anti-tumor activity in NSCLC (5–7). Further, in randomized phase III trials, the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab have produced significant improvements in overall survival compared to single-agent docetaxel delivered in the second-line setting, effectively establishing a new standard of care (8–10). This has culminated in the regulatory approvals of nivolumab and pembrolizumab in the United States for NSCLC patients with disease progression on or after platinum-based chemotherapy.

Despite the promise of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in NSCLC, it is noteworthy that most patients do not respond to therapy (ORRs ~ 20%), underscoring the need for better predictive biomarkers (8, 9). In analyses to date, increased PD-L1 expression has generally been associated with higher ORRs to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade (5–7). Studies have also shown a strong association between PD-L1 expression and improved clinical outcomes with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition compared to chemotherapy (9, 11).

Here, we sought to evaluate the activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors within two important molecular subgroups—patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements who have progressed on TKIs and who have limited therapeutic options. As part of this study, we also conducted a retrospective analysis to investigate PD-L1 expression patterns and levels of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) within a separate cohort of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients. Finally, to determine the impact of resistance to targeted therapies on PD-L1 expression, we analyzed a series of paired, pre-TKI and post-TKI specimens from EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients.

METHODS

Patients

We reviewed the medical records of all EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients treated at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) between 2011 and February 2016, identifying 28 patients who received PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors during their disease course. As a comparator population, we selected all EGFR wild-type and ALK-negative/unknown patients treated on clinical trials of single-agent PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors over this same time period (N=30).

For analysis of PD-L1 expression, we identified a separate cohort of patients with advanced, EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLC treated at MGH between 2004–2015 with sufficient archival tumor tissue available for analysis. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue was retrieved and the corresponding histology slides were reviewed for tissue adequacy (MMK). All studies were performed under Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols.

Data Collection

Medical records were reviewed and data extracted on clinicopathologic features and treatment histories. Data were updated as of February 2016. Responses were assessed per RECIST v1.1 (12). PFS was measured from the time of treatment initiation to clinical/radiographic progression or death. Patients without documented clinical or radiographic disease progression were censored on the date of last follow-up.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor histology was classified according to World Health Organization criteria. Immunohistochemistry for PD-L1 and CD8 was performed using a monoclonal anti-PD-L1 antibody (Clone E1L3N, Cell Signaling Technologies; Danvers, MA) and a CD8 monoclonal antibody (4B11, RTU, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), respectively, with an automated stainer (Bond Rx, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

The E1L3N anti-PD-L1 antibody is commercially available and has been independently validated in NSCLC (13). PD-L1 immunohistochemistry was optimized using HDLM2 and PC3 cell lines as positive and negative controls, respectively (Figure S1). Cell lines were obtained within the prior six months from the Center of Molecular Therapeutics at the MGH Cancer Center, which performs routine cell line authentication testing by single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and short tandem repeat (STR) analysis. We defined PD-L1 positivity as membranous +/− cytoplasmic staining of tumor cells of any intensity using cut-offs of ≥1%, ≥5%, and ≥50% tumor cells (Figure S2). PD-L1 immunostaining was independently scored by 2 pathologists (MMK and LZ) who were blinded to clinical outcomes. Concordance between the two observers was 0.88 (κ = 0.75) for the 1% cut-off, 0.92 (κ = 0.80) for the 5% cut-off and 0.97 (κ = 0.89) for the 50% cut-off. In cases with discrepant scores, the final score was determined upon reviewing and discussing under a multi-head microscope.

CD8+ TILs were semi-quantitatively evaluated on a scale of 0–3 based on the extent of positive lymphocytes infiltrating within tumor cells (Figure S3; ref 14). Each score was defined based on the fraction of tumor cells on top of which CD8+ T cells were present: score 0 - none or rare; score 1 - <5%; score 2 - ≥5% and <25%; score 3 - ≥25%. Subsequently, the scores were dichotomized into positive (scores 2–3) and negative (scores 0–1) for increased CD8+ TILs (14). Cytology specimens were excluded from CD8 assessments because the spatial relationship between lymphocytes and tumor cells may not have been well preserved.

An image-based analysis was also performed to quantitate CD8+ TILs. Briefly, the immunostained slides were scanned by a Whole Slide Imaging Scanner, Nanozoomer XR (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K, NJ, USA) with 20× objective (0.46um/pixel). The scanned whole section images were reviewed with NDP.view1.2 (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K, NJ, USA) and tumor regions including the stroma were outlined by a pathologist (MMK). Subsequently the images were exported from NDP.view1.2 with the magnification of 10× or 5×, and saved in a JPEG format for further analyses. The exported JPEG images were analyzed with ImageJ 1.49q (NIH, USA) for counting CD8+ TILs. Briefly, images were rescaled in ImageJ, and tumor regions were selected and the size of the region (mm2) was measured. Color segmentation plugin was applied to segment the CD8+ TILs based on color difference with the algorithm of Hidden Markov model. The segmented cells were then quantified by particle analysis. The density of CD8+ TILs in the tumor was calculated by dividing the number of cells by the size of tumor (cells/mm2). For statistical analysis, the median density of pre-treatment CD8+ TILs in the control population of KRAS-mutant NSCLC was used as the cut-off for high and low. Of note, cytology specimens and fragmented biopsy specimens were excluded from quantitative CD8 assessments due to the lack of adequate stromal component for analysis.

Mutational Analysis

EGFR and KRAS mutation testing was performed using SNaPshot (15). ALK rearrangements were identified via ALK fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using dual-color, break-apart assays and standardized criteria.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical characteristics, response rates and PD-L1 positivity between genotype cohorts. Continuous or ordinal characteristics and CD8+ TILs were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. PFS was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method using SAS 9.4 (SAS Inst Inc, Cary, NC). The PFS difference between cohorts was assessed using the logrank test and estimated as a hazard ratio (HR) by proportional hazards regression. Paired comparisons of PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs between pre- and post-TKI specimens from the same patient were evaluated using McNemar’s test, marginal homogeneity test and Wilcoxon sign-rank test, respectively, depending on whether the immunostaining data were reported as binary, ordinal or continuous. All P values are based on a two-sided hypothesis with exact calculations performed using StatXact 6.2.0 (Cytel Software Corp., Cambridge, MA).

RESULTS

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in EGFR-Mutant and ALK-Positive Patients

We identified 28 patients with EGFR mutations (N=22) or ALK rearrangements (N=6) seen at the MGH Cancer Center who were treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors between 2011 and 2016. Baseline clinical and pathological features are summarized in Table 1. Most patients (N=25; 89%) were treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors as part of a clinical trial, but three patients received commercially available pembrolizumab (N=2) or nivolumab (N=1). A majority of patients (N=23; 82%) had previously received and progressed on a TKI. Three patients (11%) with acquired TKI-resistance were maintained on a genotype-specific TKI in combination with a PD-1 inhibitor. Four patients (14%) received a combination of PD-1 and CTLA-4 blockade. Of note, the median number of prior TKIs was one (range 0–4).

Table 1.

Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics of Patients Treated with PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

| Characteristic | EGFR-Mutant or ALK-Positive (N=28) |

EGFR WT & ALK-Negative/Unknown (N=30) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis | 0.005 | ||

| Median | 54.5 | 64.5 | |

| Range | 36–75 | 35–77 | |

| Sex – no. (%) | 0.020 | ||

| Male | 8 (29) | 18 (60) | |

| Female | 20 (71) | 12 (40) | |

| Ethnicity – no. (%) | 0.292 | ||

| Caucasian | 22 (79) | 28 (93) | |

| Asian | 4 (14) | 2 (7) | |

| Othera | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Smoking History – no. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 16 (57) | 1 (3) | |

| Light (≤10 pack years) | 6 (21) | 1 (3) | |

| Heavy (>10 pack years) | 6 (21) | 28 (93) | |

| Histology - no. (%) | 0.018 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 27 (96) | 21 (70) | |

| Squamous | 1 (4) | 8 (27) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (3)b | |

| Molecular Genotype – no. (%) | <0.001 | ||

| EGFR mutations | 22 (79) | 0 (0) | |

| ALK rearrangements | 6 (21) | 0 (0) | |

| KRAS mutations | 0 (0) | 11 (37) | |

| Other/Unknownc | 0 (0) | 19 (63) | |

| Prior Lines of Therapy | 0.008 | ||

| Median | 3 | 2 | |

| Range | 0–8 | 0–4 | |

| Prior Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor – no. (%) | 23 (82) | 5 (17) | <0.001 |

| PD-1 vs. PD-L1 Inhibitors – no. (%) | |||

| PD-1 Inhibitors | 23 (82) | 20 (67) | 0.235 |

| - Nivolumab | 9 (32) | 4 (13) | |

| - Pembrolizumab | 14 (50) | 16 (53) | |

| PD-L1 Inhibitors | 5 (18) | 10 (33) | |

| - Durvalumab | 3 (11) | 1 (3) | |

| - Atezolizumab | 1 (4) | 9 (30) | |

| - Other | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

ALK – anaplastic lymphoma kinase, EGFR – epidermal growth factor receptor, WT – wild-type

Not available in one patient.

Denotes a patient with adenosquamous histology.

Six patients with squamous histology did not undergo ALK testing.

Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

As a comparator population, we identified 30 NSCLC patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors as part of clinical trials over the same time period (2011–2016). All patients were EGFR wild-type (WT) and ALK negative/unknown. The most common genetic alterations identified within this cohort were KRAS mutations, found in 11 (37%) patients (Table 1). As expected, compared to the EGFR-mutant/ALK-positive cohort, EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients were significantly older (P = 0.005) and were more likely to be male (P = 0.020) and heavy smokers (P < 0.001). The EGFR WT/ALK-negative cohort also included a significantly higher frequency of patients with squamous histology (P = 0.018). The median number of prior lines of therapy among EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients was two (range 0–4), whereas EGFR-mutant/ALK-positive patients received a median of three (range 0–8) prior lines of therapy (P = 0.008). All EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients received single-agent PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors.

Among patients with EGFR mutations or ALK rearrangements, objective radiographic responses (confirmed and uncomfirmed) were observed in 1/28 (3.6%) patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (Figure 1A). Of note, the lone partial response was seen in an EGFR-mutant patient treated with pembrolizumab. Importantly, this response was not confirmed, as the patient subsequently progressed on a confirmatory scan obtained four weeks after her initial partial response. By contrast, objective responses were observed in 7/30 (23.3%) EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (P = 0.053), all of which were confirmed on subsequent imaging. Notably, the ORR for this control cohort was similar to those observed in recent large clinical trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in NSCLC (8–10). The median PFS on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors among EGFR-mutant/ALK-positive patients was 2.07 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.84–2.07 months). Among EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients, the median PFS on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors was 2.58 months (95% CI 1.91–6.37 months). As with other studies with PD-1 pathway blockade, the median PFS fails to capture the significant difference between these two patient populations, which is clearly demonstrated by inspection of the curves and assessment of the hazard ratio (HR=0.515, P = 0.018).

Figure 1.

A) Unconfirmed/Confirmed objective response rates (ORRs) to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors comparing EGFR-mutant or ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients versus EGFR wild-type and ALK-negative/unknown patients. B) ORRs to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors of never- or light-smokers versus heavy smokers (>10 pack years). C) Progression-free survival (PFS) on PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors based upon EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement status.

We next evaluated the antitumor activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors based upon smoking status (Figure 1B). Consistent with other studies (16), the ORR among never- or light- (≤10 pack years) smokers was 4.2% versus 20.6% among heavy smokers (P = 0.123; Figure 1B). As this analysis may have been confounded by the association between a lack of smoking and the presence of EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements, we also investigated response rates to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors as a function of smoking within each molecular subgroup. Among EGFR-mutant or ALK-positive patients, one unconfirmed partial response was observed among 22 never-/light-smokers (ORR 4.5%), and no responses were seen among six heavy smokers. Within the EGFR WT and ALK-negative/unknown group, seven partial responses were seen among 28 heavy smokers (25%). Only two never-/light-smokers were in the EGFR WT and ALK-negative cohort, neither of whom responded to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Further assessments of smoking status independent of EGFR and ALK status were limited by sample size.

Altogether, our data suggest that patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements have a significantly shorter PFS (Figure 1C) and a trend towards lower response rates to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors compared to EGFR WT/ALK-negative patients.

PD-L1 Expression in EGFR-Mutant and ALK-Positive Patients: Baseline

In light of the low anti-tumor activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in our EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive cohorts above, we sought to investigate patterns of PD-L1 expression and levels of TILs in these molecular subgroups. A majority of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients who received PD-1 inhibitors above had been treated previously with TKIs. Thus, we wished to determine PD-L1 expression and levels of CD8+ TILs in both treatment-naive and TKI-resistant cancer. Due to tissue availability, our analyses were limited to a separate cohort of 95 patients with EGFR-mutant (N=68) or ALK-rearranged (N=27) NSCLC. Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics are summarized in Table S1. Of note, this population consisted largely of patients who did not receive PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors during their disease course.

We first evaluated PD-L1 expression in EGFR-mutant patients (N=62) using tissue samples obtained prior to EGFR TKI treatment. PD-L1 expression was observed in 15 (24%), 10 (16%) and 7 (11%) patients using cut-offs of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50% tumor cell staining, respectively (Table 2). In order to contextualize these findings, we next identified a cohort of 65 patients with advanced, KRAS-mutant NSCLC and performed PD-L1 expression analysis. KRAS-mutant lung cancer was used as a comparator in order to have a homogeneous control population. Moreover, KRAS mutations are the most frequent oncogenic driver in NSCLC (4). Among KRAS-mutant patients, we observed PD-L1 expression in 23 (35%), 20 (31%), and 11 (17%) patients using cut-offs for positivity of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50%, respectively (Table 3). While these rates were consistently higher than those among EGFR-mutant specimens, the numerical differences were not statistically significant due to limited power.

Table 2.

PD-L1 Expression in EGFR-Mutant and ALK-Rearranged Lung Cancer Patients Prior to and After Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Treatment

| EGFR-Mutant | ALK-Rearranged | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-TKI (N=62) |

Post-TKI (N=63) |

P Valuea | Pre-Criz (N=19) |

Post-Criz (N=12) |

P Valuea | |

| PD-L1 Positive | ||||||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) | 7 (11%) | 9 (14%) | 0.727 | 5 (26%) | 2 (17%) | 1.000 |

| PD-L1+ (≥5%) | 10 (16%) | 18 (29%) | 0.119 | 9 (47%) | 3 (25%) | 0.500 |

| CD8+ TILs (Immunohistochemistry; IHC)b | ||||||

| 0 | 17 (35%) | 18 (42%) | 0.847 | 2 (15%) | 4 (44%) | * |

| 1+ | 29 (60%) | 20 (47%) | 8 (62%) | 5 (56%) | ||

| 2+ | 2 (4.2%) | 5 (12%) | 3 (23%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 3+ | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| CD8+ TILs (Image-Based)c per mm2 | ||||||

| Median (Range) |

185.1 (6.1–1161.9) |

140.2 (4.3–1029.3) |

0.527 | 178.9 (30.1–477.4) |

69.2 (17.9–523.6) |

* |

| Concurrent PD-L1 Expression & CD8+ TILs (IHC) | ||||||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) & High CD8+ TILs (grade 2–3) | 1/48 (2.1%) | 1/43 (2.3%) | 1.000 | 0/13 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | * |

| PD-L1+ (≥ 5%) & High CD8+ TILs (grade 2–3) | 1/48 (2.1%) | 5/43 (11.6%) | 0.219 | 0/13 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | |

| Concurrent PD-L1 Expression & CD8+ TILs (Image-Based) | ||||||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) & Highd CD8+ TILs per mm2 | 2/46 (4.3%) | 1/35 (2.9%) | 1.000 | 0/11 (0%) | 0/7 (0%) | * |

| PD-L1+ (≥ 5%) & Highd CD8+ TILs per mm2 | 2/46 (4.3%) | 3/35 (8.6%) | 1.000 | 1/11 (9.1%) | 0/7 (0%) | |

All P-values are based upon paired sample analysis.

p-value not calculated based on limited pairs.

Cytology specimens and those with no tissue on the slide were excluded from the evaluation of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Cytology and markedly fragmented biopsy specimens and those with no tissue on the slide were excluded from the evaluation of CD8+ TILs.

High CD8+ TILs defined as ≥ median in the pre-treatment control (KRAS-mutant) population (330.1 per mm2).

Slight differences in the number of specimens analyzed using immunohistochemistry versus quantitative CD8 analysis reflect differences in tissue adequacy for analysis.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Table 3.

Comparison of Baseline PD-L1 Expression and CD8+ TILs in Patients with EGFR versus KRAS Mutations

| EGFR-Mutant (N=62) |

KRAS-Mutant (N=65) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 Positive | |||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) | 7 (11%) | 11 (17%) | 0.449 |

| PD-L1+ (≥5%) | 10 (16%) | 20 (31%) | 0.062 |

| CD8+ TILs (Immunohistochemistry; IHC)a | |||

| 0 | 17 (35%) | 18 (32%) | 0.159 |

| 1+ | 29 (60%) | 26 (46%) | |

| 2+ | 2 (4.2%) | 11 (20%) | |

| 3+ | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| CD8+ TILs (Image-Based)b per mm2 | |||

| Median (Range) |

185.1 (6.1–1161.9) |

330.1 (8.5–2567.3) |

0.011 |

| Concurrent PD-L1 Expression & CD8+ TILs (IHC) | |||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) & High CD8+ TILs (grade 2–3) | 1/48 (2.1%) | 7/56 (12%) | 0.066 |

| PD-L1+ (≥ 5%) & High CD8+ TILs (grade 2–3) | 1/48 (2.1%) | 11/56 (20%) | 0.005 |

| Concurrent PD-L1 Expression & CD8+ TILs (Image-Based) | |||

| PD-L1+ (≥ 50%) & Highc CD8+ TILs per mm2 | 2/46 (4.3%) | 10/56 (18%) | 0.061 |

| PD-L1+ (≥ 5%) & Highc CD8+ TILs per mm2 | 2/46 (4.3%) | 15/56 (27%) | 0.003 |

Cytology specimens and those with no tissue on the slide were excluded from the evaluation of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Cytology and markedly fragmented biopsy specimens and those with no tissue on the slide were excluded from the evaluation of CD8+ TILs.

High CD8+ TILs defined as ≥ median in the pre-treatment control (KRAS-mutant) population (330.1 per mm2).

Slight differences in the number of specimens analyzed using immunohistochemistry versus quantitative CD8 analysis reflect differences in tissue adequacy for analysis.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to rounding.

Recently, PD-L1 expression and the presence of TILs have been shown to be associated with clinical outcomes to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (6, 17). Therefore, we next performed CD8 immunohistochemistry and quantitative, image-based CD8 TIL analysis in our cohorts of EGFR-mutant and KRAS-mutant patients (Tables 2–3). By immunohistochemistry, CD8+ TILs were present in 31/48 (65%) evaluable, EGFR-mutant cases, but only 2 (4.2%) showed high levels (grade ≥2). Moreover, only 1 (2.1%) treatment naïve EGFR-mutant patient exhibited both PD-L1 expression (≥5%) and high-level CD8+ TILs in the same specimen. When CD8+ TILs were quantified using a digital-imaging platform, similar findings were observed (Table 2). Only 2/46 (4.3%) EGFR-mutant specimens had concurrent PD-L1 expression and high CD8+ TILs (≥330.1 per mm2). Interestingly, the median number of CD8+ TILs per mm2 was significantly higher among KRAS-mutant specimens (330.1) compared to EGFR-mutant specimens (185.1; Table 3; Figure S4). Moreover, KRAS-mutant patients had a significantly higher frequency of concurrent PD-L1 expression (≥5%) and high CD8+ TILs compared to EGFR-mutant patients, using both quantitative TIL analysis and immunohistochemistry (P=0.003 and P=0.005, respectively; Table 3).

We next evaluated a cohort of 19 treatment naïve ALK-positive specimens, observing PD-L1 expression in 12 (63%), 9 (47%) and 5 (26%) patients using cut-offs of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50% tumor cell staining, respectively (Table 2). Using immunohistochemistry, CD8+ TILs were present in most specimens (85%), but few (23%) had high levels (grade ≥2). Interestingly, no pre-TKI specimens demonstrated concurrent PD-L1 expression (≥5%) and high levels of CD8+ TILs as assessed by immunohistochemistry (P=0.109 versus KRAS-mutant). Using quantitative analysis, zero to one ALK-positive specimens (0–9.1%) exhibited high CD8+ TILs (≥330.1 per mm2) and PD-L1 expression (≥50% and ≥5%, respectively; Table 2). While these rates were lower compared to KRAS-mutant specimens (Table 3), the numerical differences were not statistically significant (P=0.195 and P=0.274, respectively), likely due to limited power.

Collectively, these results suggest that only a subset of TKI-naive, EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive lung cancers express PD-L1 and have CD8+ TILs, and it is rare for any of these tumors to contain both.

Acquired TKI Resistance and PD-L1 Expression

To determine whether targeted therapies affect PD-L1 expression, we analyzed repeat biopsies obtained from patients at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR or ALK TKIs. Among EGFR-mutant patients, we observed PD-L1 expression in 19 (31%), 18 (29%) and 9 (14%) post-TKI specimens using cut-offs of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50%, respectively (Table 2). Concurrent PD-L1 expression (≥5%) and CD8+ TILs were present in 9 (21%) post-EGFR TKI specimens using immunohistochemistry. Only 5 (12%) specimens demonstrated both PD-L1 expression and high-level (grade ≥2) CD8+ TILs. Similar findings were observed using quantitative CD8+ TIL analysis (Table 2). Notably, paired pre- and post-TKI biopsies were available in 57 EGFR-mutant patients (Figure 2). The degree of PD-L1 expression was consistent in both biopsies in 41 (72%) patients, but varied upon the development of resistance in 16 (28%), with 12 showing higher levels of PD-L1 expression in the resistant biopsy.

Figure 2.

PD-L1 expression levels in paired, pre- and post-TKI biopsies among EGFR-mutant patients along with representative PD-L1 immunohistochemical images. A majority of EGFR-mutant patients (72%) exhibited consistent PD-L1 staining across both specimens, but 16 (28%) patients demonstrated variable staining across biopsies.

Among 12 ALK-positive, resistant biopsies, we observed PD-L1 expression in 5 (42%), 3 (25%) and 2 (17%) specimens using cut-offs of ≥1%, ≥5% and ≥50%, respectively (Table 2), but none showed high levels of CD8+ TILs using either immunohistochemistry or quantitative CD8+ TIL analysis. Thus, like pre-TKI specimens, resistant biopsies from EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients rarely showed concomitant PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs.

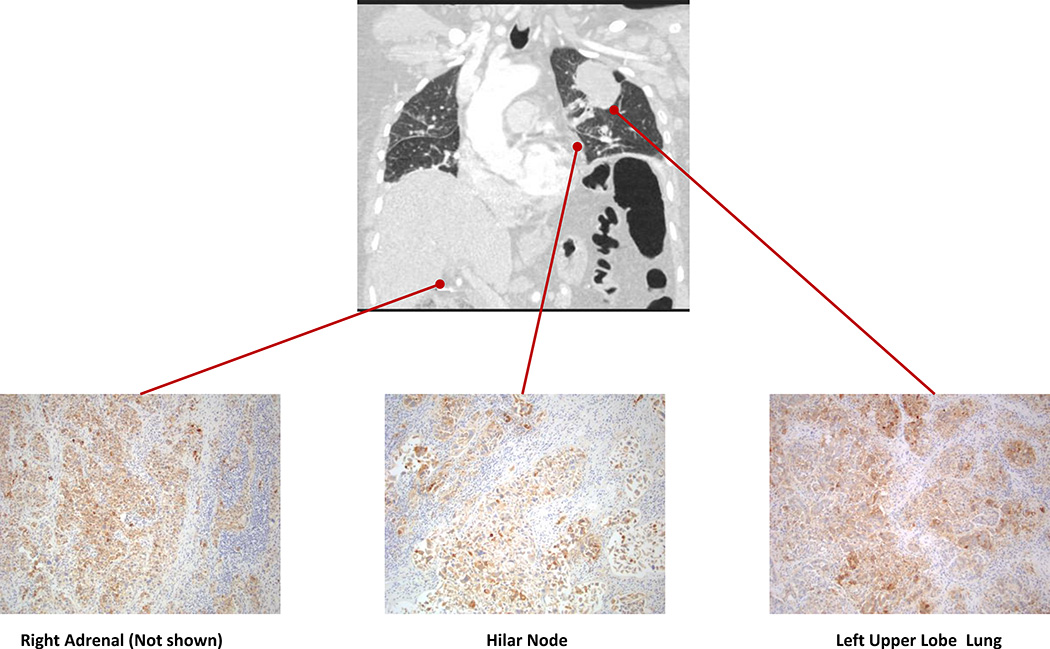

Evaluating Heterogeneity of PD-L1 Expression

To evaluate whether changes in PD-L1 staining in serial biopsies were due to tumor heterogeneity and/or different biopsy sites over time, we analyzed a series of autopsy specimens obtained from EGFR-mutant (N=3) and ALK-positive (N=1) patients. Multiple distinct sites of metastatic disease were sampled in each patient. The median number of autopsy sites examined was 4 (range 3–8). All three EGFR mutant patients demonstrated homogeneity of PD-L1 expression across sites. Two EGFR-mutant patients exhibited diffuse PD-L1 expression (≥50%) in all sites examined (N=5 and 8; Figure 3). Both patients had 1–2+ CD8+ TILs in the corresponding sites of disease. A third EGFR-mutant patient was PD-L1 negative in 3/3 examined sites. Finally, one patient with ALK-positive NSCLC demonstrated PD-L1 expression in all examined sites, but the degree of PD-L1 expression was heterogeneous (Figure S5) with low-level (5–49%) expression in some sites and diffuse (≥50%) expression in others. None of these sites showed increased levels of CD8+ TILs. Collectively, across of all of these autopsies, PD-L1 staining was relatively consistent across synchronous sites of disease.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography (CT) image of a patient with EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer demonstrating the metastatic burden of disease along with representative images of PD-L1 immunohistochemical staining of corresponding autopsy samples. Diffuse PD-L1 expression (≥50% of tumor cells expressing PD-L1) was identified in 8 distinct metastatic sites, but not in normal lung tissue.

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis, we evaluated the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors according to molecular genotype, focusing on patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements. Importantly, we observed a statistically significant shorter PFS and borderline significant lower ORR for EGFR-mutant/ALK-positive patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors compared to a cohort of EGFR WT and ALK negative/unknown patients. Such findings are consistent with recent prospective data from the CheckMate 057 and KEYNOTE 010 trials (9, 10). In both studies, PD-1 inhibitors produced significant improvements in overall survival compared to docetaxel in the overall intention-to-treat populations. However, in subgroup analyses, there was no difference between study arms among EGFR-mutant patients.

PD-L1 expression has been associated with improved response rates to PD-1 pathway blockade in NSCLC (6, 18). To date, two different mechanisms of PD-L1 up-regulation on tumors have been described (19). Adaptive immune resistance refers to induction of tumoral PD-L1 expression in response to local inflammatory signals (e.g., interferons) produced by an active anti-tumor immune response. By contrast, innate immune resistance refers to up-regulation of PD-L1 as a result of constitutive oncogenic signaling within cancer cells. For example, Marzec and colleagues observed that NPM-ALK rearrangements induce PD-L1 expression in anaplastic large cell lymphoma as a result of downstream activation of STAT3 (20). More recently, induction of PD-L1 expression due to constitutive oncogenic signaling has also been reported in NSCLC models harboring EML4-ALK rearrangements and EGFR mutations (21, 22). Furthermore, treatment with ALK and EGFR TKIs has been shown to attenuate PD-L1 expression in these models (21–23). It remains unclear, however, whether the mechanism underlying tumor PD-L1 expression (i.e., innate versus adaptive immune resistance) impacts responsiveness to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in the clinic.

Several early clinical reports suggested that EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are associated with PD-L1 overexpression (21, 22), with PD-L1 staining in up to 71.9% of EGFR-mutant patients (24) and 78% of ALK-rearranged patients (13). In contrast to such reports (13, 22, 24), we found that the frequency of PD-L1 expression among EGFR-mutant patients was relatively low prior to TKI exposure (16%; PD-L1 ≥5%) and at the time of acquired resistance (29%; PD-L1 ≥5%). In a parallel cohort of patients with metastatic ALK-rearranged NSCLC, we found that the frequency of PD-L1 expression was 47% (PD-L1 ≥5%) in the crizotinib-naïve setting and 25% (PD-L1 ≥5%) among crizotinib-resistant patients. Such differences across studies may reflect the use of different anti-PD-L1 antibodies, scoring cut-offs, or types of specimens (e.g., resection specimens versus biopsies).

Perhaps more importantly, we also observed that few EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive specimens exhibited both CD8+ TILs and concomitant PD-L1 expression. Moreover, EGFR-mutant patients had significantly lower rates of combined PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs compared to KRAS-mutant patients. Of note, we restricted our analysis to CD8+ TILs due to tissue availability. These cells are also generally thought to be the dominant effector population following treatment with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (25). Theoretically, such low rates of co-localized PD-L1 expression and CD8+ TILs may underlie the low response rates to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors among EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLC patients, as a lack of effector cells may limit an anti-tumor immune response–even in the setting of PD-L1 expression.

Recently, it has become clear that PD-L1 expression alone is an imperfect biomarker. In NSCLC, smoking exposure and tumor mutational load have also emerged as potential determinants of response to these agents. Indeed, Rizvi et al. recently reported that lung cancers with larger numbers of nonsynonymous mutations (i.e., mutational load) and neoantigens were associated with higher rates of durable clinical benefit to PD-1 inhibitors (26). Ultimately, such markers may be inter-related, since never-smokers with NSCLC (a clinical characteristic that tends to enrich for patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements) have an average mutation frequency approximately 10-fold less than smokers with the disease (27). Thus, such patients likely generate fewer neoantigens, leading to less inflamed tumor microenvironments.

Our study has several important limitations. First, this was a retrospective analysis involving a small cohort of relatively heavily pre-treated patients who received a range of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Nonetheless, we were able to show a clinically meaningful difference in response rates and PFS among EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive patients compared to those without these alterations. Moreover, the extent of prior therapy was comparable to other early-phase studies of PD-1 inhibitors (16). Another potential limitation is that the immunotherapy field currently lacks standardization with respect to PD-L1 testing. A number of different antibodies and scoring protocols have been devised (18). To account for this, we used a commercially available, anti-PD-L1 antibody that has been independently validated (13). We also evaluated a range of cut-offs for scoring PD-L1 expression, focusing on cut-offs that have been associated with benefit to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical studies (5, 7). Still, another limitation of this analysis is that pre- and post-TKI biopsies were not always obtained from the same anatomic lesions. Thus, differences in PD-L1 expression may have been due to intra-tumoral and/or inter-tumoral heterogeneity. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed multiple synchronous metastatic lesions in several autopsies, observing minimal variation in PD-L1 expression within individual patients. Finally, post-TKI biopsies were obtained at the time of acquired resistance and not early in the treatment course. Thus, we were unable to assess whether TKIs can dynamically induce changes in PD-L1 expression and/or the immune microenvironment.

In summary, we observed relatively low response rates to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors among patients with EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive lung cancer. While this finding requires validation in additional, prospective studies, such initial observations are clinically important. With a range of next-generation EGFR and ALK TKIs currently in the clinic, prioritization of therapies will be particularly important in these molecular subgroups. Despite PD-L1 expression in a subset of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLCs, we observed that expression may be dynamic within individual patients, with some exhibiting changes over time and/or in response to treatment. Moreover, only a small subset of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLCs demonstrated both PD-L1 expression and high levels of CD8+ TILs. This lack of an inflammatory microenvironment, despite PD-L1 expression, is suggestive of innate immune resistance, and may limit the effectiveness of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in these patient populations.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

PD-1 inhibitors have emerged as important therapeutic agents in the management of advanced, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In this retrospective analysis, we evaluated the activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors within two important molecular subgroups of NSCLC—patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements. Among these patients, we observed lower objective response rates to PD-1 pathway inhibitors compared to EGFR wild-type/ALK-negative patients. Based upon this observation, we also investigated the tumor immune microenvironment in an independent cohort of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive cancers, finding that a majority of EGFR-mutant and ALK-positive NSCLCs lack concurrent PD-L1 expression and high levels of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). This lack of an inflammatory microenvironment may underlie the limited effectiveness of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in these populations. Future prospective studies to confirm these observations are necessary.

Acknowledgments

None

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant numbers 5R01CA164273 to ATS and JAE, C06CA059267 to JFG) and from the National Foundation for Cancer Research (ATS). This work is supported by a Stand Up to Cancer – American Cancer Society Lung Cancer Dream Team Translational Research Grant (SU2C-AACR-DT1715). Stand Up To Cancer is a Program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation administered by the American Association for Cancer Research (JFG, BYY, JAE, MMK).

Footnotes

Disclosures: JFG has served as a compensated sultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Novartis, Merck, Clovis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Jounce Therapeutics, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin. ATS has served as a compensated consultant or received honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, Genentech, Roche, Ignyta, Blueprint, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ariad, Chugai, Taiho, and EMD Serono. LVS has served as an uncompensated consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Novartis, Merrimack, Genentech, and Taiho Pharmaceuticals. ZP has received honorarium from Clovis Oncology. AFF has received honoraria from Agios and Cell Signaling Technologies. RJS has served as a consult for Astex Pharmaceuticals. JAE has served as a consultant for Novartis, Roche, Genentech, Chugai, Merck, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. JAE has also received sponsored research from Jounce, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. MMK has served as a consultant for Merrimack and Advanced Cell Diagnostics.

References

- 1.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gainor JF, Shaw AT. Emerging paradigms in the development of resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3987–3996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. 2014;311:1998–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crino L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–1639. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015 Dec 18; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spira A, Park K, Mazieres J, Vansteenkistie JF, Rittmeyer A, Ballinger M, et al. Efficacy, safety and predictive biomarker results from a randomized phase II study comparing MPDL3280A vs docetaxel in 2L/3L NSCLC (POPLAR) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl) abstr 8010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh J, Go H, Keam B, Kim MY, Nam SJ, Kim TM, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of programmed cell death-1 and programmed cell death-ligand 1 and 2 expressions in pulmonary adenocarcinoma: comparison with histology and driver oncogenic alteration status. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:1154–1166. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2015.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahlin AM, Henriksson ML, Van Guelpen B, Stenling R, Oberg A, Rutegard J, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis depends on T-cell infiltration and molecular characteristics of the tumor. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:671–682. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dias-Santagata D, Akhavanfard S, David SS, Vernovsky V, Kuhlmann G, Boisvert SL, et al. Rapid targeted mutational analysis of human tumours: a clinical platform to guide personalized cancer medicine. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:146–158. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Rizvi NA, et al. Overall Survival and Long-Term Safety of Nivolumab (Anti-Programmed Death 1 Antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2004–2012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, Shintaku IP, Taylor EJ, Robert L, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerr K, Tsao M, Nicholson A, Yatabe Y, Wistuba I, Hirsch F. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry in lung cancer: in what state is this art? J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:985–989. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marzec M, Zhang Q, Goradia A, Raqhunath PN, Liu X, Paessler M, et al. Oncogenic kinase NPM/ALK induces through STAT3 expression of immunosuppressive protein CD274 (PD-L1, B7-H1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20852–20857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810958105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ota K, Azuma K, Kawahara A, Hattori S, Iwama E, Harada T, et al. Induction of PD-L1 Expression by the EML4-ALK Oncoprotein and Downstream Signaling Pathways in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4014–4021. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, Altabef A, Tchaicha JH, Christensen CL, et al. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1355–1363. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen N, Fang W, Zhan J, Hong S, Tang Y, Kang S, et al. Upregulation of PD-L1 by EGFR Activation Mediates the Immune Escape in EGFR-Driven NSCLC: Implication for Optional Immune Targeted Therapy for NSCLC Patients with EGFR Mutation. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:910–923. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Y, Fang W, Zhang Y, Hong S, Kang S, Yan Y, et al. The association between PD-L1 and EGFR status and the prognostic value of PD-L1 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with EGFR-TKIs. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14209–14219. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune Checkpoint Blockade: A Common Denominator Approach to Cancer Therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Govindan R, Ding L, Griffith M, Subramanian J, Dees ND, Kanchi KL, et al. Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell. 2012;150:1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.