Abstract

Abstract

Three 2'-aminochalcone derivatives (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, and (E)-1-(2-amino-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, have been synthesized, characterized, and tested in vitro in order to assess their antioxidant activity. All compounds were characterized on the basis of 1H NMR, 13C NMR, ESI-mass spectrometry, FT-IR, UV/Vis, and elemental analysis. The X-ray crystal structures of (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one and (E)-1-(2-amino-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one were successfully determined showing a planar molecule geometry. Studies on the biological properties including test of free radical scavenging ability (DPPH test) and superoxide dismutase mimetic activity were performed. The results indicate that the aminochalcone carrying two hydroxyl functionalities in adjacent meta and para position exhibits a stronger antioxidant activity than the other derivatives.

Graphical abstract

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00706-016-1812-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Claisen condensation, Structure activity relationship, X-ray structure determination

Introduction

Medicinal plants have always represented one of the most excellent and ancient sources of pharmaceutical agents in the history of medicinal chemistry. Among them chalcones are natural colorful pigments present in several medicinal and edible plants [1]. They act as intermediates in the flavonoid biosynthesis serving different physiological functions such as UV photoprotectors, insect repellents, and attractants of pollinators [2, 3]. Besides these physiological aspects chalcones provide an attractive scaffold for medicinal chemistry, as they possess a wide range of biological activities and are compounds of high therapeutical interest [4].

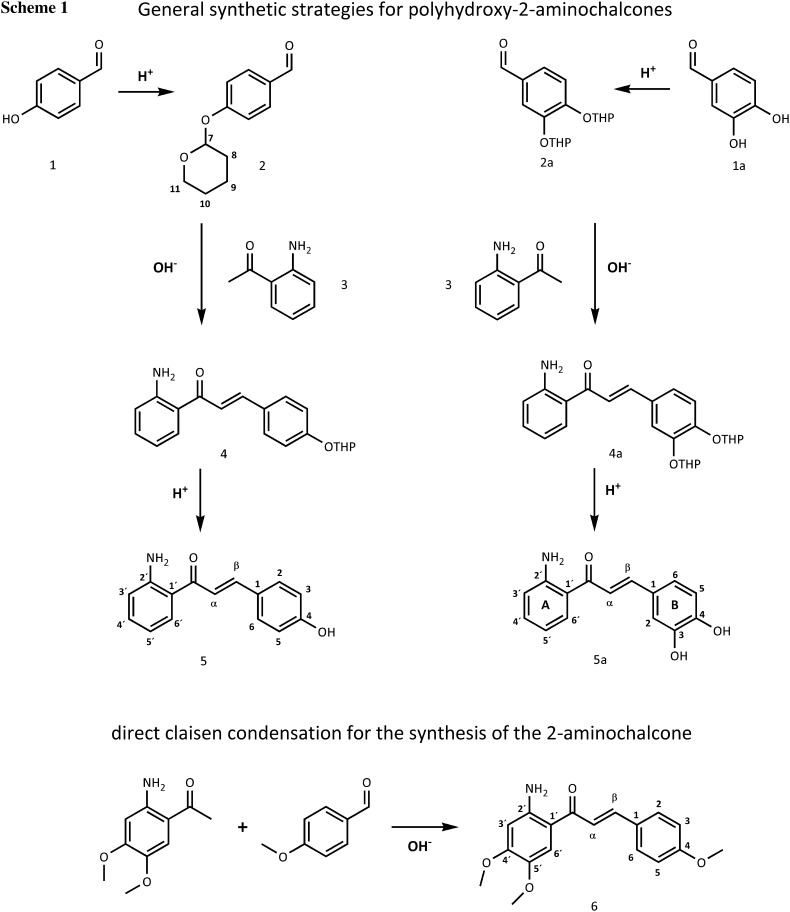

In the past decades a large number of reports have been published on the pharmacological effects of chalcones, and it has repeatedly been claimed that this natural product is efficient and safe for the prevention and treatment of several diseases such as atherosclerosis and neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer disease, preventing the low density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation [5, 6]. Chalcones have been investigated for their anti-tumor [7], anti-inflammatory [8], antifungal and antibacterial properties [9] as well as for their radical scavenging potential [10]. Structurally they possess a 1,3-diaryl-2-propen-1-one skeleton (see Scheme 1). The presence of the α,β-unsaturated keto functionality (2-propen-1-one chain) seems to be responsible for the medicinal properties of the chalcones [11, 12].

In fact it has been proven in previous studies that the electrophilicity of this α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety is involved in the antioxidant [13, 14] activities of chalcones. Additionally, although numerous antioxidant substances belong to different chemical classes, they have a certain electronic and steric characteristic in common: in particular an important requisite would be a planar structure with two hydrophobic moieties (aromatic groups) and an acidic proton (the phenolic proton) [15]. These characteristics, which are all present in chalcones, make them suitable candidates for the design of new drugs; moreover, depending on the substitution pattern of the two rings they can display different spectra of activity. In this work we focused our attention on hydroxyl, methoxyl, and amino substitution in order to observe how they impact the biological activities of chalcones.

Methoxylated and hydroxylated chalcones are also well known for their powerful antioxidant activities. In fact it has been reported in literature that natural chalcones carrying methoxyl and hydroxyl substitutions such as butein, isoliquiritigenin, cardamonin, flavokawain A and B, are able to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10]. Normally living organisms are protected against highly reactive oxygen species by an endogenous system of enzymes like superoxide dismutase or other naturally occurring antioxidants widely distributed in the biological system such as ascorbic acid or vitamin E for instance [16]. In fact a high level of ROS can attack essential biological molecules like lipids, proteins, and DNA, and it has been already demonstrated that in case of disease the production of ROS is increased [17]. As a consequence, natural and synthetic molecules possessing multifunctional antioxidant activities such as flavonoids are of great interest and important in disease prevention and in therapy [18]. Within this polyhedral class of compounds, 2'-aminochalcone derivatives still represent a new domain of investigation. Currently they have been investigated for their antitumor activity [19, 20], and additionally they have shown to be useful as photoprotectors in sunscreen formulations as well as in textile polymers or fibers because of their high UV–visible extinction coefficient [21, 22]. Apart from these promising aspects, little is known about the reactivity/response of aminochalcones towards reactive oxygen species. Thus, an evaluation of the potential biological applications of the novel amino chalcone-based compounds will give more insights into their mode-of-action. Therefore, they could represent in the future new templates for novel antioxidants.

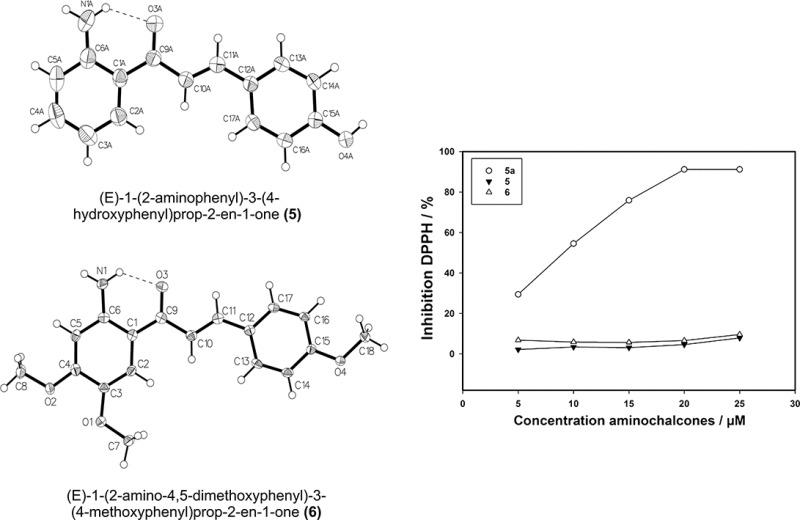

In this work three new chalcones with methoxyl, hydroxyl, and amino substitutions on ring A as well as on ring B were synthesized and characterized with the aim to investigate their antioxidant properties and clarify their molecular structure. The compounds are therefore characterized via 1H NMR, 13C NMR, FT-IR, and UV–Vis and elemental analysis. The crystal structures of the newly synthesized molecules 1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5) and 1-(2-amino-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (6) (see Scheme 1) were solved by single-crystal X-ray diffraction in order to study the conformation of the typical chalcones.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of 2'-aminochalcone derivatives

All three final compounds (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5), (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5a), and (E)-1-(2-amino-4-methoxyphenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (6) were obtained with moderate-to-good yields and purely in the E form confirmed by the means of 1H NMR and X-ray crystallography. The amino chalcones 5 and 5a were synthesized according to the most common base-catalyzed Claisen Schmidt condensation using barium hydroxide octahydrate [23]. 5 and 5a were obtained via a three-step procedure (see Scheme 1). First the appropriate benzaldehydes 1 and 1a were protected with tetrahydropyranyl (THP) to obtain 2 and 2a. THP has been chosen as a protecting group because it is easy to insert and remove and it is also stable under normal alkaline coupling conditions [24]. Protection proceeded in both cases in good yield (89 % for 2 and 69 % for 2a). Subsequently a base-catalyzed aldol condensation reaction between the aminoacetophenone with protected benzaldehydes 2 and 2a was performed to furnish the protected aminochalcones 4 and 4a species with a yield of 39 % and 40 %, respectively. Compound 4a was immediately used without any further purification and its identity checked by ESI-mass spectrometry (see “Experimental” section compound 4a). Compound 4 instead was purified by flash column chromatography. After purification 4 decomposes very fast turning from yellow to dark red, therefore 13C NMR measurements have not been recorded and 4 was immediately used for the condensation step. Finally deprotection was performed to give the hydroxy-2'-aminochalcones 5 and 5a with a yield of 25 % for 5 and 20 % for 5a. All the condensation reactions worked only moderately, and purification with liquid column chromatography is challenging after condensation as well as after the hydrolysis reaction. This may be due to the formation of the cyclization side product between the amino group on the A ring and the aromatic B ring, which is very difficult to separate from the target compound by flash column chromatography as the two molecules have the same retention time. The cyclization of 2'-aminochalcones has been reported before [25]. Moreover, the different attempts pointed out that both time and temperature influence the hydrolysis reaction.

Synthesis of the 2'-aminochalcone 6 was carried out between the 2-aminoacetophenone and the 4-methoxybenzaldehyde in one direct reaction leading to a yield of 40 % of the pure product.

Spectroscopic and mass characterization

Characterization of the synthesized compounds was performed by ESI-mass spectrometry, FT-IR spectroscopy, UV–Vis spectroscopy, 1H NMR, and 13C NMR. All techniques confirm unambiguously the structure of the final products 5, 5a, and 6. ESI-MS analysis shows the molecular ion peak always with good intensity and in accordance with the calculated empirical formula. The same is valid for elemental analysis results. For compounds 5 and 6 the typical strong NH2 asymmetric and symmetric vibrations were visible at 3340/3042 cm−1 (5) and 3386/3267 cm−1 (6), respectively. For compound 5a the NH2 stretching overlapped with the strong broad band of the two OH groups [26]. All the absorptions arising from the aromatic rings appear between 1400 and 1600 cm−1. The UV–Vis absorption occurs in the range from 480 to 260 nm, showing maxima of absorption at 240, 342, and 399 nm for 5, 364 and 487 nm for 5a, and 244, 323, and 412 nm for 6 [27]. These values are attributed to π–π* and n–π* transitions due to the excitation in the aromatic ring and the C=O group [28].

Finally, the characteristic high value of the coupling constant of the double bond of the enone moiety (see also 1H NMR of and Hα and Hβ, “Experimental” section) indicates that the chalcones 5, 5a, and 6 were obtained in the E form [29]. The Hβ of the olefinic system is more deshielded then Hα because of the π-bond delocalization, and therefore they both appear in the aromatic region. This result is in good agreement with the X-ray structure analyses data obtained for 5 and 6.

X-ray crystallography

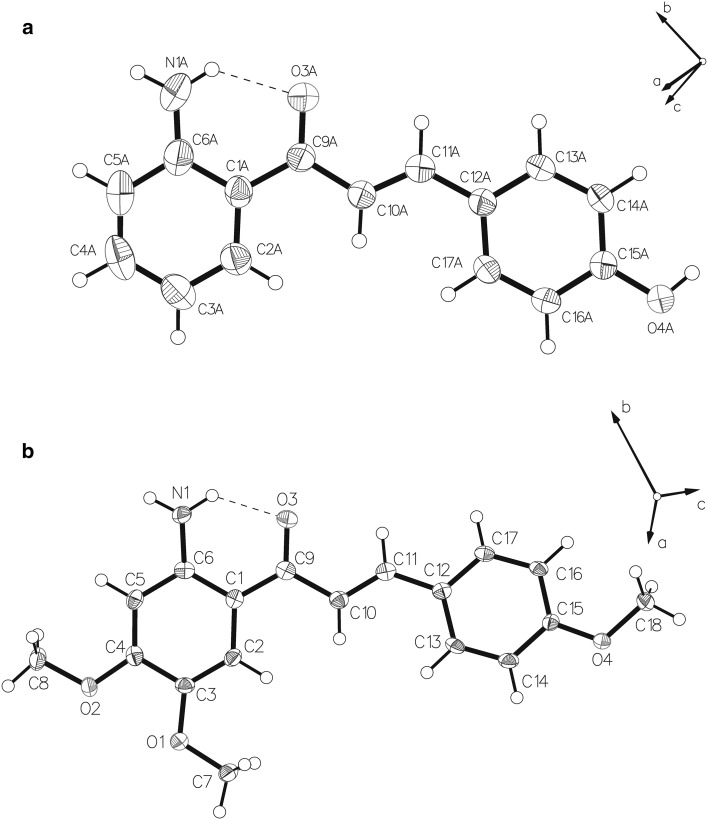

5 and 6 were crystallized at room temperature from a mixture of dichloromethane/methanol 9:5 for 5 and hexane/ethyl acetate 9:2 for 6. A summary of crystal parameters and refinement details of 5 and 6 are given in Table 1. Compounds 5 and 6 crystallize in the space groups P21/c and Iba2, respectively. The asymmetric unit of compound 5 contains five independent molecules, whereas the asymmetric unit of 6 contains one molecule. All bond distances and angles are comparable to previous reports [30] and similar experimental value were previously found for the 2'-aminochalcone (E)-1-(2-aminophenyl)-3-(pyridine-4-yl)prop-2-en-1-one [31] and (E)-1-(4-aminophenyl)-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one [32]. The ORTEP diagrams of 5 and 6 prepared with OLEX2 are shown in Fig. 1 along with the atom numbering scheme. The results confirm that the olefinic double bond in both compounds is in the E configuration and that the OH group in 5 and the OCH3 group in 6 are located in para position on ring B. The most interesting structural feature is a plane molecular conformation: in fact the hydrogen bonding interaction between the amino function NH2 and the carbonylic O atom seems to play an important role in defining the planar conformation of the molecule. The oxygen atoms O(3A) in 5 and O(3) in 6 act as an acceptor in a moderate intramolecular hydrogen bond involved with the adjacent NA(1)–H2 and N(1)–H2 functionalities, respectively (see Fig. S1 and S2). The same O(3A) atom in 5 acts again as an acceptor in a likewise moderate intermolecular hydrogen bond interaction with the O(4)–H group. The N(1A)–O(3) and O(3)–O(4) distances are 2.621 and 2.640 Å for compound 5 (see Table 2). Similar distances are observed for compound 6 (Table 3). The intramolecular hydrogen bond seems to be the most significant coadjuvant to the molecular packing forces that support the planarity of the entire molecule, although further contribution could originate also from weak aromatic ring-stacking interactions between the phenyl rings and the keto-enolic moiety.

Table 1.

Crystal data and structure refinement for compounds 5 and 6

| Identification code | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C15H13NO2 | C18H19NO4 |

| M r/g cm−3 | 1.305 | 1.314 |

| Space group | P2 1 /c | Iba2 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic |

| a/Å | 18.877(4) | 13.1460(13) |

| b/Å | 16.644(3) | 29.598(3) |

| c/Å | 19.387(4) | 8.1392(6) |

| α/° | 90 | 90 |

| β/° | 91.781(10) | 90 |

| γ/° | 90 | 90 |

| V/Å3 | 6088(2) | 3166.9(5) |

| Z | 20 | 8 |

| μ/mm−1 | 0.087 | 0.093 |

| Reflns collected | 126774 | 17995 |

| Independent reflns | 15117 | 2924 |

| R(int) | 0.0638 | 0.0776 |

| GooF on F 2 | 1.025 | 1.033 |

| R 1 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0579 | 0.0403 |

| wR 2 (all data) | 0.1596 | 0.0943 |

Fig. 1.

ORTEP style drawings based on X-ray structure analysis of 5 (a) and 6 (b) with atom numbering scheme. Thermal parameters enclose 50 % probability

Table 2.

Selected hydrogen bond distances/Å and angles/° for 5

| D | H | A | d(D-H)/Å | d(H-A)/Å | d(D-A)/Å | D-H-A/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O(4A) | H(4A) | O(3B)a | 0.84 | 1.80 | 2.640(2) | 174.0 |

| N(1A) | H(1AB) | O(3A) | 0.88 | 1.96 | 2.621(3) | 130.3 |

a+X, 1/2 − Y, −1/2 + Z

Table 3.

Selected hydrogen bond distances/Å and angles/° for 6

| D | H | A | d(D-H)/Å | d(H-A)/Å | d(D-A)/Å | D-H-A/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(1) | H(1A) | O(3) | 0.88 | 1.93 | 2.584(4) | 130.4 |

| N(1) | H(1B) | O(3)a | 0.88 | 2.03 | 2.890(4) | 166.8 |

a+X,1-Y,-1/2+Z

Antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity under in vitro conditions has been explored through two different methods, namely the superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay and the DPPH radical scavenging method. The DPPH test relies on the antioxidant ability to quench the radical by hydrogen donation capacity, whereas the SOD-like assay is based on the fact that antioxidants can suppress the formation of reactive oxygen species by inhibiting the enzymes involved in its generation and have superoxide scavenging activities themselves [33, 34]. Both methods have been chosen because they have already been widely used to determine the antioxidant activity of isoflavonoids [35].

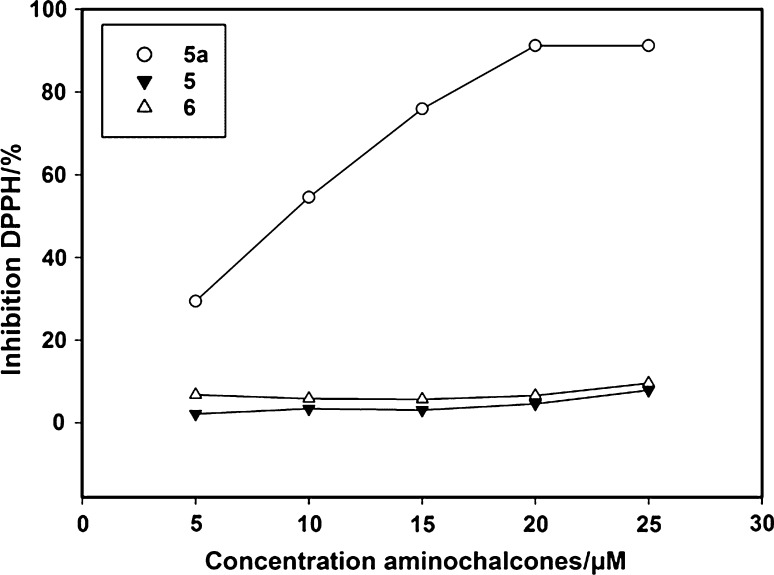

Free radical scavenging ability

The free radical scavenging ability of the synthesized 2'-aminochalcones was evaluated by the DPPH radical assay. The results are summarized in Fig. 2. The aminochalcone 5a shows an IC50 value (the antioxidant concentration necessary to decrease the initial amount of DPPH by 50 %) of 4.9 ± 1 µM which is even better than the one for catechol that in the same experimental condition showed an IC50 of 5.3 ± 1 µM (see Table 4). The results point out that the presence of the two hydroxyl groups in ring B of 5a are important for the antioxidant activity of the aminochalcones [10]. For the other two compounds 5 and 6 the IC50 is not reached within the concentrations applied. Our values are close to the ones determined for other potent natural flavonoids [36]. Some studies on antioxidant properties of chalcones highlighted a mechanism involving H atom transfer from the phenolic moiety of the ring B [18]. In contrast to these reports no significant free radical scavenging ability is observed for the aminochalcone 5. This result is comparable to previous antioxidant activity studies performed by Iqbal et al. [37] on a series of 4-aminochalcones and sulfonamide-substituted chalcones, which also did not show a powerful antioxidant activity. Previous studies performed on the trimethoxy chalcone 1-(2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-(1-methylbuta-1,3-dienyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]propenone, suggested that the amino group is not involved in the antioxidant mechanism [38]. The measurements reported here evidence only a significant inhibition of DPPH for 5a that exhibit two phenolic groups in meta and para position on ring B, therefore this would suggest that the mechanism of the H-transfer originate mainly from the phenolic group rather than from the keto-enolic moiety. The two adjacent hydroxyl groups seem to be mainly responsible for the antioxidant activity of the aminochalcone, supporting the mechanism proposed by Hwang et al. [18].

Fig. 2.

The percentage of inhibition of the free DPPH radical in the presence of 5, 5a, and 6. The concentration of the different compounds is expressed as µM

Table 4.

IC50 value of the aminochalcones 5, 5a, and 6 for the inhibition of xanthine oxidase and the inhibition of DPPH

| Compound | SOD mimic activity IC50/μM ± SDa | DPPH radical assay IC50/μM ± SDa |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 38.6 ± 1 | – |

| 5a | 37.1 ± 1 | 4.9 ± 1 |

| 6 | – | – |

| Caffeic acid | 34.1 ± 1 | – |

| Catechol | – | 5.3 ± 1 |

aStandard deviation

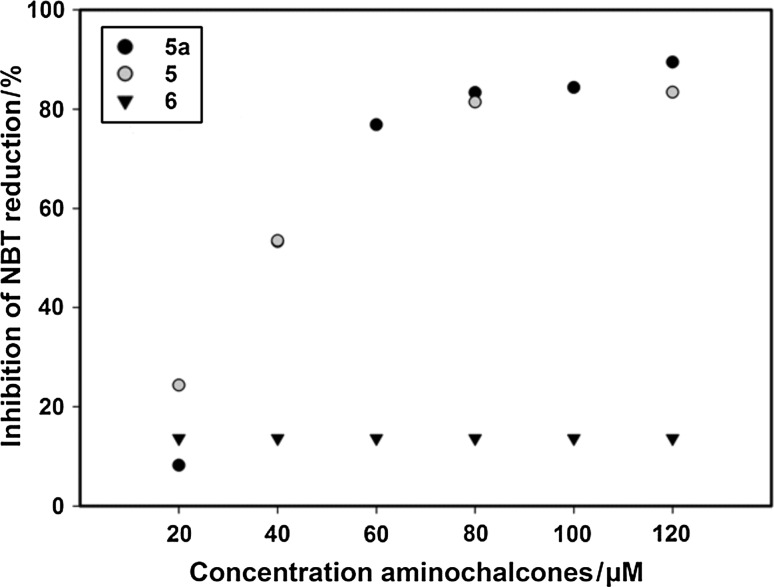

Superoxide scavenging ability

The superoxide radical anions are generated in vitro by a xanthine/xanthine oxidase system causing the reduction of the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT2+) and consequently the determination of the scavenging activity of the chalcones. Applying this method O.−2 reduces the yellow colored (NBT2+) to produce the blue formazan, which is measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm. Antioxidants are scavengers of oxygen free radicals and prevent the purple NBT formation [39]. The compounds 5, 5a, and 6 were studied as potential scavengers of oxygen free radicals and the results are summarized in Fig. 3, which illustrates the percentage of inhibition of NBT2+ against the concentration of the different synthesized 2'-aminochalcones 5, 5a, and 6. The IC50 value, that is the concentration of 2'-aminochalcone necessary to reduce the absorbance of the NBT2+ to half of its initial value was calculated to 38.6 ± 1 µM for 5 and 37.1 ± 1 µM for 5a (see Table 4). The IC50 value of the aminochalcones 5 and 5a is not so much different to the ones previously found for other flavonoids such as rutin (42.7 µM) and quercetin (42.3 µM) [40]. For comparative purpose, we have also measured the activity of caffeic acid which showed an IC50 of 34.1 µM under the same experimental condition. The IC50 value is not reached for 6 which showed a very low activity comparable to that one previously found for nobiletin and tangeretin [39]. In previous studies it has been proposed that the reaction takes place by donating the unpaired electron from superoxide radical to the flavonoids [41]. According to this reaction mechanism the presence of at least one hydroxyl group on the B ring seems to be essential for the activity, and would explain the lack of scavenging activity for compound 6. In fact the percentage of inhibition of superoxide anions is not affected by increasing the concentration of the aminochalcones 6. Previous studies [42] on superoxide scavenging activity performed on a series of 4′-aminochalcones showed a dose-dependent inhibition of superoxide radicals. In fact it has been observed that the activity increased when the aminochalcones dose level was higher. Interestingly the same aminochalcones possess an electron-releasing group at position 4 of the ring B, therefore this structural characteristic seems to be essential for significant antioxidant activity. Additionally it has been observed that the superoxide scavenging activity is sensitive to the planarity of the molecule [39] present in 5 and 5a.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of inhibition (% In) of superoxide radical formed by xanthine/xanthine oxidase enzyme by different concentrations of 2'-aminochalcones assayed by NBT2+ absorption at 560 nm in presence of 5, 5a, and 6. The concentration of the different compounds is expressed as µM

Conclusion

This study reports on the synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of antioxidant activity of three different 2'-aminochalcones. The antioxidant activity was evaluated with two different methods: superoxide scavenging assay and DPPH radical scavenging testing. Compound 5a having two adjacent hydroxyl groups in the B ring exhibits very high antioxidant activity compared to compounds 5 and 6 based on the DPPH test. The presence of the OH groups in 5 (one in ring B) and 5a (two adjacent ones in ring B) makes them good candidates for superoxide scavenging activity. Compound 6 having a methoxyl substituent in ring B reveals to be less effective. Therefore, this set of aminochalcones shows a clear correlation between the number and the position of OH groups and their activity. The planar structure evidenced by NMR spectroscopy and X-ray structure analysis seems to be an important prerequisite for the activity of the molecule. The intramolecular hydrogen bond interaction with the adjacent carbonylic oxygen functionality contributes to stabilize the planar structure of the studied chalcones.

Experimental

Chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, they were of reagent grade and used without any further purification unless otherwise specified. All NMR spectra were recorded at the NMR core facility 1090 Wien, Währinger Straße 38 of the University of Vienna with a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz NMR spectrometer at 500.32 MHz (1H), 125.81 MHz (13C), in CDCl3, methanol-d4, or acetone-d6 at ambient temperature. The splitting of proton resonances in the 1H NMR spectra are defined as s = singlet, d = doublet, dd = doublet of doublets, ddd = doublet of doublets of doublets, t = triplet, and m = multiplet. Numbering of carbon atoms and protons refers to Scheme 1. Electrospray ionization mass spectra were recorded at the Mass Spectrometry Center (MSC) of the Chemical Faculty of the University of Vienna on a Bruker Esquire 3000 with an orthogonal ESI source applying MeOH/ACN as solvent. The molecular mass was determined in the positive mode. Elemental analyses were carried out in the Mikroanalytisches Laboratorium of the University of Vienna with a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN elemental analyser. The spectrophotometer Shimadzu UV 1800 has been used to recorder the UV–Vis spectra. Spectra were collected in methanol. The infrared spectra were recorded with an infrared spectrometer Bruker Tensor 27 FTIR equipped with a global MIR light source, a KBr beam splitter, and a DLaTGS detector. Sample and background spectra were averaged from 100 scans at 4 cm−1 resolution. Undiluted sample powder was pressed on the diamond window of a Harrick MVP 2 diamond ATR accessory. Background spectra were obtained from the empty ATR unit. Data handling was performed with OPUS 5.5 software (Bruker Optik GmbH, 2005). Intensities of reported IR bands are defined as br = broad, s = strong, m = medium, and w = weak.

4-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)benzaldehyde (2, C12H14O3)

4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde (1, 6.60 mmol) and pyridinium para-toluenesulfonate (0.16 mmol) were dissolved in 30 cm3 of dichloromethane and the solution was mixed at room temperature. Subsequently, 3,4-dihydro-α-pyran (19.73 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction was stirred for 24 h and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the mixture was washed with water, dried over Na2SO4, concentrated under vacuum, and purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate 7:3) to obtain pure 2. Yield: 89 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.50–1.58 (m, 1H, H-10b), 1.60–1.80 (m, 2H, H-9b, 10a), 1.82–1.93 (m, 2H, H-8b, H-9a), 1.96–2.08 (m, 1H, H-8a), 3.64 (m, 1H, H-11b), 3.82–3.93 (m, 1H, H-11a), 5.55 (t, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.13–7.20 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.0 Hz, 2H, H-3, H-5), 7.81–7.87 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.0 Hz, 2H, H-2, H-6), 9.97 (s, 1H, C=O) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 191.1 (C=O), 161.7 (C-4), 132.4 (C-2,6), 131.9 (C-1), 115.9 (C-3,5), 96.1 (C-7), 63.0 (C-11), 30.0 (C-8), 25.3 (C-10), 19.6 (C-9) ppm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 229.0829 ([M+Na]+, calcd. for C12H14O3Na 229.0835).

3,4-Bis(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)benzaldehyde (2a, C17H22O5)

3,4-Dihydroxybenzaldehyde (1a, 6.60 mmol) and pyridinium para-toluensulfonate (0.16 mmol) were dissolved in 30 cm3 of dichloromethane and the solution was mixed at room temperature. Subsequently, 3,4-dihydro-α-pyran (39.46 mmol) was added dropwise. The reaction was stirred for 24 h and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the mixture was washed with water, dried over Na2SO4, concentrated under vacuum, and purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate 9:2) to obtain 2a as a mixture of stereoisomers. Yield: 69 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.58–1.50 (m, 2H, H-10b, 10b′), 1.60–1.80 (m, 4H, H-9b, H-9b′, H-10a, H-10a′), 1. 82–1.93 (m, 4H, H-8b, H-8b′, H-9a, H-9a′), 1.96–2.08 (m, 2H, H-8a, H-8a′) 3.64 (m, 2H, H-11b, H-11b), 3.82–3.93 (m, 2H, H-11a, H-11′a), 5.55 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 2H, H-7, H-7′), 7.05–7.07 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.25 (s, 1H, H-2), 7.49–7.50 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, H-6), 9.87 (s, 1H, CHO) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 190.6 (C=O), 153.1 (C-4), 146.9 (C-3), 129.8 (C-1), 123.9 (C-6), 115.8 (C-5), 115.2 (C-2), 98.4 (C-7), 98.9 (C-7′), 63.7 (C-11), 63.3 (C-11′), 30.1 (C-8), 30.1 (C-8′), 25.4 (C-10), 25.2 (C-10′) 19.4 (C-9), 18.8 (C-9′) ppm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 329.1356 ([M+Na]+), 307.1534 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C17H22O5 307.1461).

(E)-1-(2-Aminophenyl)-3-[4-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)phenyl]prop-2-en-1-one (4, C20H21NO3)

2 (4.24 mmol) and 3 (8.48 mmol) were dissolved in 10 cm3 of methanol under reflux at 35 °C. Subsequently, a solution of 20 cm3 of methanol containing barium hydroxide octahydrate (16.96 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the mixture was concentrated under vacuum, quenched with 0.1 M HCl and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated under vacuum. The reaction mixture was purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate 7:3) to obtain pure 4. Yield: 40 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.50–1.58 (m, 1H, H-10b), 1.60–1.80 (m, 2H, H-9b, 10a), 1.82–1.93 (m, 2H, H-8b, H-9a), 1.96–2.08 (m, 1H, H-8a), 3.64 (m, 1H, H-11b), 3.82–3.93 (m, 1H, H-11a), 5.55 (t, J = 3.1 Hz, 1H, H-7), 6.69–6.71 (m, 2H, H-5′, H-6′), 6.3 (br. s, 2H, NH2), 7.08–7.10 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.50–7.53 (d, 1H, J = 15.4 Hz, H-α), 7.27–7.30 (t, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz, H-4′), 7.57–7.59 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz, H-5, H-3), 7.71–7.74 (d, 1H, J = 15.4 Hz, H-β), 7.86–7.87 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz, H-3′) ppm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 346.1426 ([M+Na]+), 324.1604 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C20H21NO3 324.1594).

(E)-3-[3,4-Bis(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)phenyl]-1-(2-aminophenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (4a, C25H29NO5)

2a (4.24 mmol) and 3 (8.48 mmol) were dissolved in 10 cm3 of methanol under reflux at 35 °C. Subsequently, a solution of 20 cm3 of methanol containing barium hydroxide octahydrate (16.96 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the mixture was concentrated under vacuum, quenched with 0.1 M HCl and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated under vacuum. The residue yielded the crude chalcone 4a as a yellow powder and was used for the next step without any further purification. Yield: 39 %; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 446.1955 ([M+Na]+), 424.2133 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C25H29NO5 424.2118).

(E)-1-(2-Aminophenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5, C15H13NO2)

4 (1.26 mmol) was dissolved in 50 cm3 of methanol. Subsequently pyridinium para-toluensulfonate (0.062 mmol) was added and the reaction was stirred under reflux and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the reaction mixture was directly concentrated under vacuum and then purified by flash column chromatography (dichloromethane/methanol 9.5/0.5). Yield: 25 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 6.60–6.63 (t, J = 6.62 Hz, 1H, H-4′), 6.81–6.83 (d, 1H, J = 8.2 Hz, H-6′), 6.90–6.92 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2, H-6), 7.04 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.24–7.27 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, H-5′), 7.67–7.69 (d, 1H, J = 15.4 Hz, H-α), 7.67–7.69 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H, H-5, H-3), 7.72–7.75 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H, C-β), 8.01–8.03 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 8.83 (s, 1H, OH) ppm; 13C NMR (126 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 190.8 (C=O), 159.5 (C-4), 152.0 (C-2′), 133.7 (C-5′), 130.9 (C-3′), 130.1 (C-α), 127.1 (C-1), 126.8 (C-5, C-3), 120.02 (C-β), 117.6 (C-1′), 115.7 (C-2, C-6), 115.3(C-6′), 114.7 (C-4′) ppm; FT-IR (KBr): = 3340, 3042, 3000, 1640, 1600, 1587, 1520, 1326 cm−1; UV/Vis (methanol): λmax = 240, 342, 399 nm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 262.0832 ([M+Na]+), 240.1012 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C15H13NO2 240.1019).

(E)-1-(2-Aminophenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (5a, C15H13NO3)

4a (1.26 mmol) was dissolved in 50 cm3 of methanol. Subsequently, pyridinium para-toluensulfonate (0.062 mmol) was added and the reaction was stirred under reflux at 50 °C and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the reaction mixture was directly concentrated under vacuum and then purified by column flash chromatography (Sephadex LH-20, dichloromethane/methanol 9.5/0.5). Yield: 20 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 6.62–6.64 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, H-4′), 6.88–6.90 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, H-6), 6.81–6.83 (d, 1H, J = 9.5 Hz, H-6′), 7.03 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.16–7.18 (dd, J = 10.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 7.24–7.27 (t, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, H-5′), 7.30 (s, 1H, H-2), 7.61–7.58 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H, C-β), 7.65–7.68 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H, C-α), 8.0–8.02 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 8.06 (OH), 8.42 (OH) ppm; 13C NMR (126 MHz, acetone-d6): δ = 191.0 (C=O), 151.9 (C-2′), 147.6 (C-3), 145.3(C-4), 142.7 (C-β), 133.8 (C-5′), 130.7 (C-3′), 127.7 (C-1′), 121.9 (C-5), 120.0 (C-α), 118.5 (C-1), 116.9 (C-6′), 115.4 (C-4′), 115.3 (C-6), 114.8 (C-2) ppm; FT-IR (KBr): = 3325, 1640, 1600, 1573, 1505, 1326 cm−1; UV/Vis (methanol): λmax = 364, 487 nm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 278.0780 ([M+Na] +), 256.0961 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C15H13NO3 256.0968).

(E)-1-(2-Amino-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (6, C18H19NO4)

1-(2-Amino-4,5-dimethoxyphenyl)ethanone (4.24 mmol) and 4-methoxybenzaldehyde (4.24 mmol) were dissolved in 10 cm3 of methanol at 35 °C under reflux. Subsequently, a solution of 20 cm3 of methanol containing barium hydroxide octahydrate (16.96 mmol) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and the progress was monitored by TLC. Then the mixture was concentrated under vacuum, quenched with 0.1 M HCl and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was separated, dried over Na2SO4 and then concentrated under vacuum. The reaction mixture was purified by flash column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate 9:2) to obtain pure 6. Yield: 40 %; 1H NMR (500 MHz, methanol-d4): δ = 3.82 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.86 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.36 (s, 1H, H-6′), 6.96–6.98 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H, H-2, H-6), 7.39 (s, 1H, H-3′), 7.56–7.60 (d, 1H, J = 15.5 Hz, Hα), 7.60–7.63 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H, H-β), 7.68–7.67 (d, J = 8.50 Hz, 2H, H-4, H-5) ppm; 13C NMR (126 MHz, methanol-d4): δ = 191.6 (C=O), 163.1 (C-4′), 157.8 (C-5′), 151.7 (C-4), 143.3 (C-β), 141.3 (C-1′), 131.3 (C-5, C-3), 129.6 (C-2′), 122.4 (C-α), 115.9 (C-3′), 115.7 (C-2, C-6), 112.2 (C-1), 100.6 (C-6′), 56.4 (C-OCH3), 56.2 (C-OCH3), 56.1(C-OCH3) ppm; FT-IR (KBr): = 3386, 3267, 1630, 1563, 1501, 1401, 1342 cm−1; UV/Vis (methanol): λmax = 244, 323, 412 nm; HRMS (ESI–MS): m/z = 336.1206 ([M+Na]+), 314.1384 ([M+H]+, calcd. for C18H19NO4 314.1386).

Crystallographic structure determination

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected with Bruker diffractometers, equipped with a multilayer monochromator, INCOATEC microfocus sealed tube (λ (MoKα) = 0.71073 Ǻ), and with a CMOS Photon Detector at 100 K for 6, and with a APEXII CCD detector for 5 at 200 K, respectively. The data reductions were performed using APEX2 (Bruker Analytical X-ray systems, Madison, 2004) software package. The structure solution was executed using SHELXS [43] with the GUI OLEX2 [44]. The structure refinements were realized with SHELXL [45] embedded in GUI’s OLEX2 [44] and ShelXle [45]. The crystallographic results were proofed with PLATON [46]. OLEX2 [44] calculated modified hkl-files to finalize the refinement process. Both, the original and the modified hkl-files, were uploaded to the CCDC database (http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/) with the accession number 1406883 for 5 and 1406882 for 6.

Antioxidant activity (DPPH radical scavenging method)

The antioxidant activity test is conducted according to the method described by Ferrari et al. [47]. 1-x cm3 of 6 × 10−5 mM DPPH radical solution is prepared in methanol and mixed with a variable amount x mm3 (x = 5, 10, 15, 20 mm3, etc.) of a methanolic solution containing the 2'-aminochalcone (1.2 mM). The absorbance of the mixture is measured immediately every second up to 30 min at 517 nm at 20 °C. For the baseline a control sample of 1 cm3 of methanol was used. The percentage of inhibition of the DPPH radical was calculated for each sample referring to the following formula in accordance to Ref. [47]:

where A0 is the absorbance of the control (DPPH radical) at time 0 and At is the absorbance of the mixture DPPH–antioxidant at time t (30 min). All the determinations were performed in triplicate and the values of absorbance were corrected considering the factor of dilution. The IC50 value was also calculated from the regression line.

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD assay using XO/NBT system)

The SOD-like activity is performed with the method described by Ferrari et al. [48] with some modification. Superoxide was generated by enzymatic methods employing a xanthine/xanthine oxidase assay. A mixture containing 50 μM of xanthine, 300 μM of NBT2+ (nitro blue tetrazolium) and variable amounts from 0 to 120 μM of 2'-aminochalcone were dissolved in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 1 cm3. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.04 unit/cm3 of xanthine oxidase. The absorbance changes during the NBT2+ formation were monitored spectrophotometrically at 560 nm for 20 min at 25 °C. The percentage of inhibition (% In) of NBT2+ formation was calculated according to the equation of the linear regression:

where A is the absorbance value, k0 is the slope of the straight line/the speed of reduction of NBT2+, and t is the time of reduction, and k1 is the intercept of the straight line. From this data we were able to calculate the inhibitory ability of the synthesized compounds according to the following formula:

where k0 is the slope of the straight line in the presence of the 2'-aminochalcone and kred is the speed of reduction of NBT2+ by superoxide anions generated by xanthine oxidase at 560 nm in the absence of the antioxidant. The IC50 value was also calculated from a linear regression of the observed inhibition against the logarithm of the concentration of the compound.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna. The authors wish to kindly acknowledge Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Markus Galanski, NMR Centre, Faculty of Chemistry, University of Vienna for NMR measurement and Ing. Peter Unteregger for support with the ESI-MS measurements at the Massenspektrometriezentrum of the University of Vienna. We thank Amir Blazevic, MSc. and Dipl.-Ing. Matthias Pretzler for valuable discussions about the data reported in the manuscript.

References

- 1.Rozmer Z, Perjesi P. Phytochem Rev. 2016;15:87. doi: 10.1007/s11101-014-9387-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhar DN. The chemistry of chalcones and related compounds. New York: Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kong J-M, Chia L-S, Goh N-K, Chia T-F, Brouillard R. Phytochemistry. 2003;64:923. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P, Anand A, Kumar V. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;85:758. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaya J, Belinky PA, Aviram M. Free Radical Biol Med. 1997;23:302. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerry NL, Abbey M. Atherosclerosis. 1997;135:93. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(97)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ducki S. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:336. doi: 10.2174/1871520610909030336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kontogiorgis C, Mantzanidou M, Hadjipavlou-Litina D. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:1224. doi: 10.2174/138955708786141034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowakowska Z. Eur J Med Chem. 2007;42:125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishida J, Kawabata J. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70:193. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orlikova B, Tasdemir D, Golais F, Dicato M, Diederich M. Genes Nutr. 2011;6:125. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0210-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attar S, O’Brien Z, Alhaddad H, Golden ML, Calderon-Urrea A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:2055. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anto RJ, Sukumaran K, Kuttan G, Rao MNA, Subbaraju V, Kuttan R. Cancer Lett. 1995;97:33. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03945-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calliste CA, Le Bail JC, Trouillas P, Pouget C, Habrioux G, Chulia AJ, Duroux JL. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimmock JR, Elias DW, Beazely MA, Kandepu NM. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacob RA, Burri BJ. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:985. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halliwell B, Gutterridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim BT, O KJ, Chun J-C, Hwang K-J. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2008;29:1125. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2008.29.6.1125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pati HN, Holt HL, Jr, LeBlanc R, Dickson J, Stewart M, Brown T, Lee M. Med Chem Res. 2005;14:19. doi: 10.1007/s00044-004-0122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Y, Yang Z-Y, Xia P, Bastow KF, Nakanishi Y, Lee K-H. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:699. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George F, Fellague T (2003) Preparation of amino substituted chalcone derivatives for use in cosmetic compositions as sunscreens and suntanning agents. WO 2003097577, 27 Nov 2003

- 22.George F, Fellague T. Chem Abstr. 2003;142:56053. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen SF, Larsen M, Boesen T, Schønning K, Kromann H. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2667. doi: 10.1021/jm049424k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu S, Zhuang X, Pan X, Zhang Z, Duan L, Liu Y, Zhang L, Ren X, Ding K. J Med Chem. 2013;56:4631. doi: 10.1021/jm4003928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Z, Li Y, Pan L, Xu X. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:2974. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201400468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masoud MS, Abou El-Enein SA, Abed IM, Ali AE. J Coord Chem. 2002;55:153. doi: 10.1080/00958970211879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khatib S, Nerya O, Musa R, Shmuel M, Tamir S, Vaya J. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:433. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruanwas P, Chantrapromma S, Fun H-K. Mol Cryst Liquid Cryst. 2015;609:126. doi: 10.1080/15421406.2014.950003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandgar BP, Patil SA, Gacche RN, Korbad BL, Hote BS, Kinkar SN, Jalde SS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:730. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen FH, Kennard O, Watson DG, Brammer L, Orpen AG, Taylor R. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1987;2:1. doi: 10.1039/p298700000s1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz Ortiz AF, Sanchez Lopez A, García Ríos A, Cuenú Cabezas F, Rozo Correa CE. J Mol Struct. 2015;1098:216. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2015.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fun H-K, Kobkeatthawin T, Ruanwasb P, Chantrapromma S. Acta Crystallogr Sect E: Struct Rep Online E. 2010;66:o1973. doi: 10.1107/S1600536810026346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sichel G, Corsaro C, Scalia M, Di Bilio AJ, Bonomo RP. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:1. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu JP, Calomme M, Lasure A, De Bruyne T, Pieters L, Vlietinck A, Vanden Berghe DA. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1995;47:327. doi: 10.1007/BF02790134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivakumar PM, Prabhakar PK, Doble M. Med Chem Res. 2011;20:482. doi: 10.1007/s00044-010-9342-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang W, Chen W, Yang Y, Liu T, Yang H, Xin Z. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:200. doi: 10.1021/jf504289g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iqbal H, Prabhakar V, Sangith A, Chandrika B, Balasubramanian R. Med Chem Res. 2014;23:4383. doi: 10.1007/s00044-014-1007-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bandgar BP, Gawande SS, Bodade RG, Totre JV, Khobragade CN. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:8168. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cos P, Ying L, Calomme M, Hu JP, Cimanga K, Van Poel B, Pieters L, Vlietinck AJ, Vanden Berghe D. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:71. doi: 10.1021/np970237h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robak J, Gryglewski RJ. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:837. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jovanovic SV, Steenken S, Tosic M, Marjanovic B, Simic MG. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:4846. doi: 10.1021/ja00090a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasad YR, Rani VJ, Rao AS. Asian J Chem. 2013;25:52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr Sect A: Found Crystallogr. 2008;64:112. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, Puschmann H. J Appl Crystallogr. 2009;42:339. doi: 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hubschle CB, Sheldrick GM, Dittrich B. J Appl Crystallogr. 2011;44:1281. doi: 10.1107/S0021889811043202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spek AL. Acta Crystallogr Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:148. doi: 10.1107/S090744490804362X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferrari E, Asti M, Benassi R, Pignedoli F, Saladini M. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:5304. doi: 10.1039/c3dt33072a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrari E, Benassi R, Sacchi S, Pignedoli F, Asti M, Saladini M. J Inorg Biochem. 2014;139:38. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.