Abstract

Temperature is an important factor influencing the distribution of marine picocyanobacteria. However, molecular responses contributing to temperature preferences are poorly understood in these important primary producers. We compared the temperature acclimation of a tropical Synechococcus strain WH8102 with temperate strain BL107 at 18 °C relative to 22 °C and examined their global protein expression, growth patterns, photosynthetic efficiency and lipid composition. Global protein expression profiles demonstrate the partitioning of the proteome into major categories: photosynthesis (>40%), translation (10–15%) and membrane transport (2–8%) with distinct differences between and within strains grown at different temperatures. At low temperature, growth and photosynthesis of strain WH8102 was significantly decreased, while BL107 was largely unaffected. There was an increased abundance of proteins involved in protein biosynthesis at 18 °C for BL107. Each strain showed distinct differences in lipid composition with higher unsaturation in strain BL107. We hypothesize that differences in membrane fluidity, abundance of protein biosynthesis machinery and the maintenance of photosynthesis efficiency contribute to the acclimation of strain BL107 to low temperature. Additional proteins unique to BL107 may also contribute to this strain's improved fitness at low temperature. Such adaptive capacities are likely important factors favoring growth of temperate strains over tropical strains in high latitude niches.

Introduction

Picoplanktonic cyanobacteria Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus are the most abundant photosynthetic prokaryotes in the marine environment. Their photosynthetic capacity and high abundance make them prominent components of the marine biosphere where they contribute significantly to global primary production and biogeochemical nutrient cycling (Garczarek et al., 2008; Palenik et al., 2009; Scanlan et al., 2009).

Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus differ in their distribution across the marine environment. Prochlorococcus numerically dominates warm oligotrophic regions, while Synechococcus is more widespread with higher abundance in coastal and temperate waters. Synechococcus is a genetically diverse group with lineages exhibiting horizontal partitioning in the ocean (Scanlan et al., 2009; Scanlan, 2012). Phylogenies based on ribosomal RNA genes display three main subclusters, 5.1, 5.2 and 5.3, which are further classified into over 20 phylogenetically-distinct clades. The largest, sub-cluster 5.1, is the dominant cluster in the marine environment (Urbach et al., 1998; Herdman et al., 2001; Fuller et al., 2003; Dufresne et al., 2008; Ahlgren and Rocap, 2012). Oceanic surveys indicate that these clades exhibit broad distribution from the equator to the polar regions having colonized habitats defined by a broad range of light, temperature and nutrient regimes (Fuller et al., 2003; Ahlgren and Rocap, 2006; Penno et al., 2006; Paerl et al., 2008; Zwirglmaier et al., 2008; Scanlan et al., 2009; Post et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2012; Mazard et al., 2012). The genomic complements of strains from different clades provide insights to preferential habitat niches (Dufresne et al., 2008).

Clades I, II, III and IV represent the most abundant Synechococcus lineages and these display distinct niche preferences. Clades I and IV are predominant in oceanic latitudes above 30°N and below 30°S. Clades II and III are found mostly within tropical and sub-tropical oceanic latitudes (Zwirglmaier et al., 2007, 2008; Scanlan et al., 2009; Mella-Flores et al., 2011; Post et al., 2011; Ahlgren and Rocap, 2012; Mazard et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Sohm et al., 2015). In relation to temperature, clades I and IV occur at higher abundances at 10 –20 °C whereas clades II and III occur in the range of 20–28 °C (Zwirglmaier et al., 2008) suggesting that temperature, among other environmental factors, may have a key role in their partitioning. Predicted changes in temperature within marine provinces have the potential to force changes in the abundance and distribution of picocyanobacteria. This could significantly impact on primary production in marine ecosystems, due to metabolic and physiological differences between Synechococcus clades.

Studies in freshwater cyanobacteria have shown that growth temperature affects a wide range of cellular functions, from the photosynthetic apparatus and rates of electron transport to membrane fluidity, enzyme structure and function and metabolic reactions (Huner et al., 1998; Hongsthong et al., 2008). Pittera et al. (2014) and Mackey et al. (2013) have shown that temperature changes influence growth and photosynthesis of selected marine Synechococcus clades. The temperatures at which adjustments in growth rate and photochemistry occurred varied between different isolates of Synechococcus in accordance with their thermal niche ranges. Phycobilisomes (PBS) have a major role in the regulation of photosynthetic electron flow through photosystem II (PSII) over relatively short-term transitions to lower temperature (Pittera et al., 2014), initially mediated by a state transition to photosystem I (PSI), followed by decoupling of the PBS from the electron transport chain. In general, isolates from warmer regions had less capacity to regulate PBS state transitions and displayed greater PBS decoupling, PSII inactivation and reduced non-photochemical quenching when shifted to 13 °C from 22 °C.

Mackey et al. (2013) also show that PBS state transitions have an important role in temperature acclimation for a range of marine strains. They suggest that this may be linked to changes in the relative abundance of major photosynthetic and electron transport proteins in a tropical Synechococcus strain WH8102. These general responses in growth rate and photophysiology at different temperatures demonstrate the adaptability of Synechococcus isolates across a broad range of optimal growth temperatures. However, they do not explain the fundamental differences in each clade that result in the vastly different observed environmental distributions (Zwirglmaier et al., 2008; Sohm et al., 2015).

This study aims to understand the impacts of growth temperature at the global cellular level to explore the molecular factors influencing the physiological adaptation of distinct lineages to different temperature niches. Two environmentally relevant representatives were selected to investigate molecular responses during low temperature acclimation, a temperate isolate Synechococcus BL107 (clade IV; Dufresne et al., 2008) and a tropical isolate Synechococcus WH8102 (clade III; Palenik et al., 2003). The effect of temperature on growth and physiology was determined using growth assays, pulse-amplitude-modulation fluorometry and total lipid analyses in combination with label-free shotgun proteomic analyses on whole-cell lysates to provide insights into the molecular basis of cellular responses to low temperature.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and growth

All Synechococcus isolates used in the study were grown in synthetic ocean water-based medium with 13.4 μM Na2EDTA.2H2O, 87.6 μM K2HPO4, 96.8 μM Na2CO3 and 9 mM NaNO3 (Morel et al., 1979; Su et al., 2006). Cultures were grown at 18 °C and 22 °C under constant illumination of 20 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and agitation at 100 r.p.m. Cultures were acclimated to experimental temperature conditions through three successful serial transfers (8 generations total) before harvesting cells in logarithmic phase. Experiments were performed in biological triplicates for each condition. Growth was measured based on optical density at 750 nm (Beckman DU 640 spectrophotometer, Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Photosynthetic efficiency was measured during the entire growth period as the quantum yield (Fv/Fm) of PSII using a Phytoplankton analyzer, Phyto-pulse-amplitude-modulation with PhytoWin V1.45 software (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). An aliquot of the culture (1 ml) was dark adapted (5 min) before measuring yield using a saturated pulse of light. Averages for growth rates and photosynthetic yield during exponential phase were calculated and significance determined using independent two-sample t-tests. For proteomics, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and total lipid analyses, cells were harvested from 100 to 500 ml of culture in logarithmic phase by centrifugation (7000 g, 10 min) at 4 °C. Cells were washed with Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), centrifuged (3100 g, 10 min) at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C until further processing or processed immediately for RNA extraction.

The absence of heterotrophic bacterial contamination was verified by plating an aliquot of the cultures on ASW medium solidified with 10.0 g l−1 agar and supplemented with 100 mg l−1 peptone.

Label-free shotgun proteomics

Proteins were extracted from cell pellets using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer (4.6% w/v SDS, 0.12 M Tris (pH 6.8), 1 mM EDTA, 4% w/v glycerol and 0.1% v/v β-mercaptoethanol) with bead beating followed by centrifugation (10 000 g, 10 min). Extracted proteins were precipitated using methanol/chloroform/water protocol (Wessel and Flügge, 1984). Protein pellets were resuspended in 2% w/v SDS and 50 mM Tris (pH 6.8) and quantitated using bicinchoninic acid protein assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples were diluted with sample loading buffer, denatured by boiling (95 °C, 5 min) and fractionated using SDS-PAGE (4–20% precast gel; Bio-Rad, Sydney, NSW, Australia). Sample loading and running buffers were prepared using suggested protocols (Bio-Rad). For each sample, 150 μg of total protein was resolved into 16 fractions at 60 V for 15 min followed by 110 V for 45 min. Peptides were extracted after gel de-staining followed by trypsin digestion as described in Mirzaei et al. (2012). Trypsin-digested peptides were analyzed using nanoflow liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Supplementary File 1) performed on a VelosPro linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA).

Raw spectral files converted to mzXML were processed using the global proteome machine (GPM) software with the X!Tandem algorithm (Craig and Beavis, 2003, 2004). Protein sequences extracted from the sequenced genome of each individual strain were used as the search database (Palenik et al., 2003; Dufresne et al., 2008). To ensure data quality, identified proteins were filtered based on two criteria: reproducible identification across three replicates and a total spectral count of >5 (Gammulla et al., 2010; Mirzaei et al., 2011). A database of reversed sequences was searched to determine the false discovery rate.

Quantitative analyses of expressed proteins were performed based on spectral counts and normalized spectral abundance factor (NSAF) (Zybailov et al., 2006). NSAF for each protein (represented by k) in an experiment is calculated as the number of spectral counts (SpC) identifying k divided by its length (L), divided by sum of SpC/L of all identified proteins (Zybailov et al., 2006). Such normalization accounts for differences in spectral counts dependent on protein length (Zybailov et al., 2006; Mosley et al., 2009; Neilson et al., 2014). For statistical analyses, NSAF values were log-transformed to ensure normal distribution and checked using density estimation (kernel density plots). Population means were analyzed using box plots to ensure similarity across replicates and conditions (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Two sample t-tests were performed on log-transformed NSAF values comparing protein expression at 18 °C relative to 22 °C using the program Scrappy (Mirzaei et al., 2012; Neilson et al., 2014).

Proteomic data sets from this study were deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (Vizcaíno et al., 2014) via the PRIDE partner repository (Vizcaíno et al., 2013) under the accession code PXD002914.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Gene expression at the transcriptional level was determined using qRT-PCR as an independent means of examining differential expression. Cells were lysed using TRIzol reagent (Ambion, Life Technologies, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) at 55 °C for 40 min. RNA purification was performed using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). DNase digestion was carried out using TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion, Life Technologies) with the addition of ribonuclease inhibitor (RNaseOUT, Invitrogen, Life Technologies). The QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen) was used for cDNA synthesis. qRT-PCR was performed using 2.5 ng of cDNA as template and Brilliant II SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Agilent Technologies, Integrated Sciences, Sydney, NSW, Australia). Negative controls including ‘no RT' were performed to ensure the absence of genomic DNA contamination.

Cycle threshold values were determined using Realplex software 2.0 in a Realplex mastercycler (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). Target genes were selected based on the proteomic data. Using rnpB as the reference housekeeping gene, target gene expression was determined using ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primers were designed using Primer3Plus version 2.3.6 (Untergasser et al., 2012). Primer efficiency and secondary amplification using melting curves were tested. Target genes and specific primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Total lipid analyses

Cell pellets from 500 ml of cultures of BL107 (clade IV), WH8102 (clade III) and WH8109 (clade II) (two biological replicates) were analyzed at Waite Analytical Services (Adelaide, SA, Australia). Fatty acids were extracted using a modified Bligh and Dyer technique and analyzed via gas chromatography as described in Makrides et al. (1996). Statistical analyses were performed using independent two-sample t-tests.

Results and Discussion

The effect of low temperature on growth and photophysiology

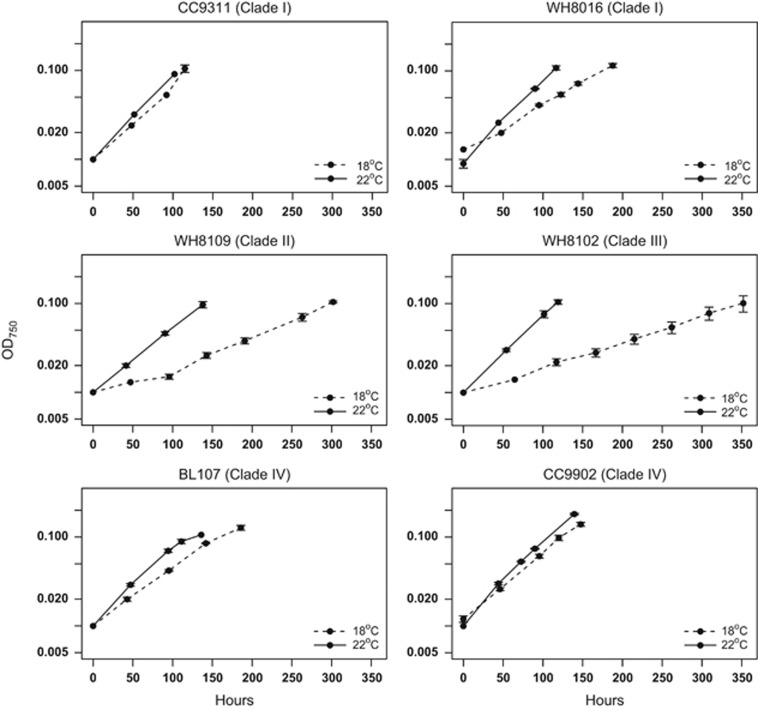

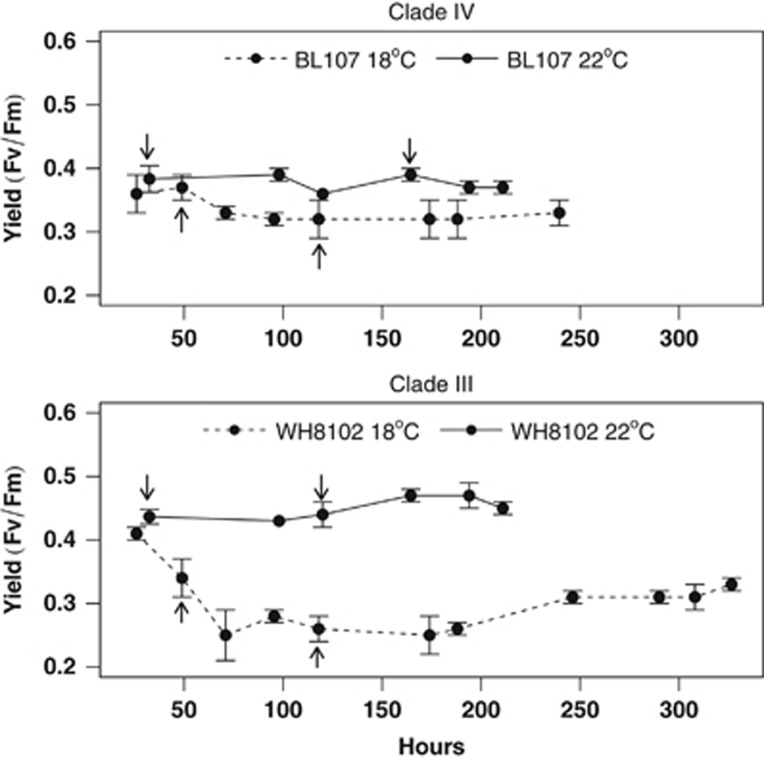

Growth experiments were conducted on representative strains of Synechococcus clades I, II, III and IV at 18 °C and 22 °C under constant irradiance. Two strains from each of the four clades (except clade III, for which only one strain was available) were grown at the two growth temperatures (Table 1; Figure 1). At 18 °C, growth rates in the temperate strains CC9311 (clade I), BL107 (clade IV) and CC9902 (clade IV) were marginally lower. One temperate strain WH8016 (clade I) showed a more significant growth reduction at 18 °C. The tropical strains were substantially affected by low temperature with growth rates at 18 °C less than 50% of that at 22 °C for strains WH8102 (clade III) and WH8109 (clade II). The tropical strain CC9605 (clade II) failed to grow beyond three generations following transfer to 18 °C (data not shown). These growth patterns correlate well with the ecological thermal niche preferences of each clade: <20 °C for temperate clades and >20 °C for tropical clades (Zwirglmaier et al., 2008). Based on the growth data, strains BL107 (clade IV) and WH8102 (clade III) were selected to determine the influence of low temperature on photosynthetic yield (Fv/Fm) measured using pulse-amplitude-modulation fluorometry (Figure 2). At low temperature, average yield was significantly reduced (P<0.001) in the tropical isolate WH8102. In contrast, temperate isolate BL107 maintained photosynthetic efficiency at both growth temperatures (P⩾0.05).

Table 1. Growth physiology of Synechococcus strains grown at 18 °C and 22 °C.

| Clade | Strains | Average growth rate±s.d. |

|---|---|---|

| I | CC9311 18 °C | 0.48±0.016* |

| CC9311 22 °C | 0.52±0.008 | |

| WH8016 18 °C | 0.30±0.009**** | |

| WH8016 22 °C | 0.48±0.004 | |

| II | WH8109 18 °C | 0.18±0.009**** |

| WH8109 22 °C | 0.40±0.011 | |

| CC9605 18 °C | n/aa | |

| CC9605 22 °C | 0.33±0.014 | |

| III | WH8102 18 °C | 0.16±0.013**** |

| WH8102 22 °C | 0.47±0.018 | |

| IV | BL107 18 °C | 0.36±0.003*** |

| BL107 22 °C | 0.48±0.011 | |

| CC9902 18 °C | 0.42±0.004*** | |

| CC9902 22 °C | 0.49±0.008 |

*P<0.05, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Growth rates for strain CC9605 were not calculated since it did not grow beyond three generations after transfer to 18 °C.

Figure 1.

Growth physiology of Synechococcus isolates at 18 °C and 22 °C. Isolates CC9311 and WH8016 of clade I, WH8109 of clade II, WH8102 of clade III and BL107 and CC9902 of clade IV. The x axis represents growth period in hours and the y axis represents optical density at 750 nm. Dashed lines represent growth at 18 °C and solid lines represent growth at 22 °C.

Figure 2.

PSII photosynthetic yield in Synechococcus isolates BL107 (clade IV) and WH8102 (clade III) at 18 °C and 22 °C. The x axis represents growth period in hours and the y axis represents mean quantum yield (Fv/Fm). Dashed lines represent growth at 18 °C and solid lines represent growth at 22 °C. Arrows indicate time of serial transfers.

The effect of low temperature on membrane lipid saturation

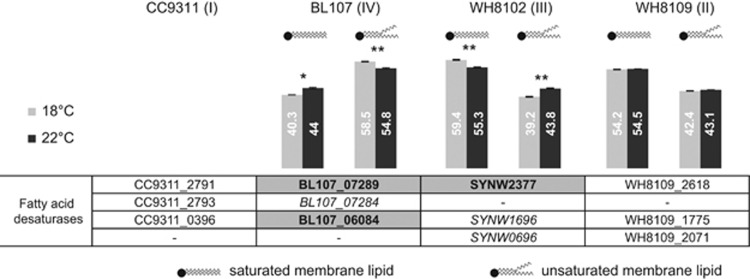

Low temperature causes a reduction in membrane fluidity, and in the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis increased unsaturation of fatty acids is essential for maintaining membrane fluidity at low temperature (Wada et al., 1994; Hongsthong et al., 2008). Total cellular lipids were analyzed to determine whether the observed differences in growth rates at 18 °C (relative to 22 °C) between temperate and tropical strains can be correlated with changes in fatty acid saturation. At 18 °C and 22 °C, the level of fatty acid unsaturation in the temperate strain, BL107, was at least 25% higher than in the tropical strains, WH8102 and WH8109 (Figure 3). Furthermore, strain BL107 increases the level of membrane fatty acid unsaturation at 18 °C compared with 22 °C (P<0.01), suggesting that it has additional capacity to regulate its membrane fluidity at lower temperatures. In contrast, isolate WH8102 displayed a decrease in lipid unsaturation (P<0.01) and isolate WH8109 showed no change in unsaturation at low temperature. The higher saturated fatty acid content and the lack of increase in unsaturation in tropical strains WH8102 and WH8109 could be a major factor in their reduced adaptability to low temperatures. This loss in fluidity can have severe consequences to cell functioning including loss in transport efficiency as well as impairing the repair cycle of the photosystem core proteins and exacerbating photoinhibition (Gombos et al., 1994; Murata and Los, 1997). Higher latitude isolates such as BL107 may have additional mechanisms to regulate membrane fluidity. Comparison of fatty acid desaturase genes in temperate and tropical genomes revealed an additional ortholog in BL107 (BL107_07284) and CC9311 that was absent from strains WH8102 and WH8109 (Figure 3), which may have a role in regulating membrane fluidity at low temperature. Desaturases were either not detected or were unchanged in abundance as determined from proteomic analyses.

Figure 3.

Lipid composition of Synechococcus isolates BL107 (clade IV), WH8102 (clade III) and WH8109 (clade II) when grown at 18 °C (light gray) and 22 °C (dark gray). Included in the figure are genes encoding fatty acid desaturases in representative isolates of clades I, II, III and IV. Gene IDs in bold represent proteins that are detected but not differentially expressed and those in italics represent proteins that are not detected.

Molecular-level adaptations to growth temperature

The temperature adaptation of strains WH8102 and BL107 at the molecular level was examined following eight generations of growth at 18 °C and 22 °C. Total soluble proteins extracted from logarithmic phase cultures were fractionated by 1D SDS-PAGE and analyzed by reverse-phase liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. The total number of proteins identified from this label-free quantitative proteomic analysis provided coverage of 28% and 40% of the predicted proteome for strains WH8102 and BL107, respectively (Supplementary Table S2).

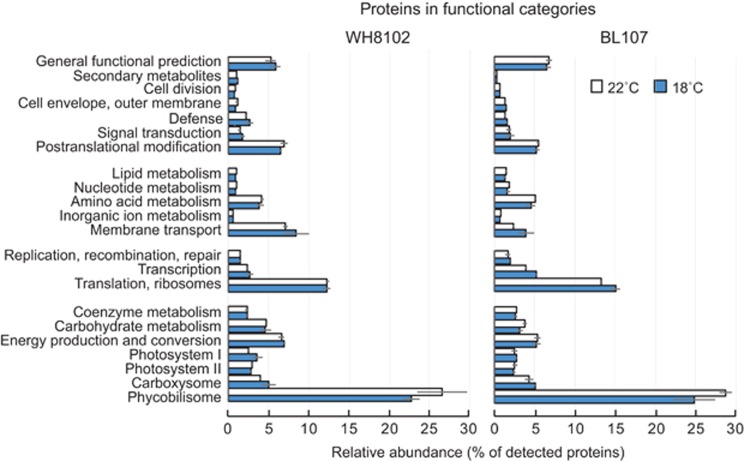

Detected proteins were grouped into functional categories based on COG (Clusters of Orthologous Genes) (Tatusov et al., 2003) with custom groupings for proteins involved in photosynthesis (that is, PBS, photosystems and carboxysomes) and membrane transporters (Figure 4). In total, nearly half (46.2–50.2%) of all of the detected protein in each strain was invested in photosynthesis, energy production and carbohydrate metabolism. PBS proteins account for up to 50% of total cellular protein in some cyanobacterial strains (Tandeau de Marsac and Cohen-Bazire, 1977). Under the relatively low light growth conditions used (20 μmol photons m−2s−1) PBS proteins also accounted for a significant proportion of the proteome of each strain (26.5% and 28.8% for WH8102 and BL107 at 22 °C, respectively). Lower relative abundance of PBS proteins (~12%, P<0.1) was evident in both strains at 18 °C relative to 22 °C, as previously reported for WH8102 (Mackey et al., 2013). In contrast to PBS, the relative abundance of carboxysome proteins increased at 18 °C in strain BL107 (P<0.1; not significant in WH8102 P>0.1).

Figure 4.

Relative expression of proteins in functional groups at 18 °C and 22 °C in Synechococcus strains BL107 (clade IV) and WH8102 (clade III). Proteins were grouped into functional categories based on primary COGs with additional manually curated groups (phycobilisome, PSI and PSII, carboxysome, membrane transport). The relative abundance is determined as the sum of NSAF of all detected proteins in that functional category. Error bars are based on sum of NSAF of three biological replicates.

The relative abundance of protein invested in PSI and PSII was approximately equal in both strains. No other differences within strains were obvious in this category, however, the tropical strain (WH8102) invested more (22–30% P<0.05) in the energy production and conversion machinery than BL107 under all growth conditions tested.

Among the other functional categories, there were significant differences between strains, providing insight into intrinsic differences in resource allocation that may underpin contrasting lifestyle strategies. The temperate strain, BL107, invested significantly more in proteins required for transcription, ribosomes and translation (P<0.01) as well as key enzymes for the assimilation of amino acids and nitrogen (cysteine synthase, glutamate synthase and glutamine synthase). Strain WH8102 displayed more than double the relative amount of protein dedicated to membrane transporters than BL107 (P<0.001). Transport proteins highly expressed in WH8102 include three periplasmic binding proteins for phosphate (PstS, SYNW1018), Fe2+ (FutA, SYNW1797) and urea (SYNW2442); two outer membrane porins (SYNW2224, SYNW0227); a cyanate transporter and an ABC type multidrug efflux system (SYNW0193).

The following sections look at specific differentially abundant proteins at the two temperatures within relevant functional categories across the two strains.

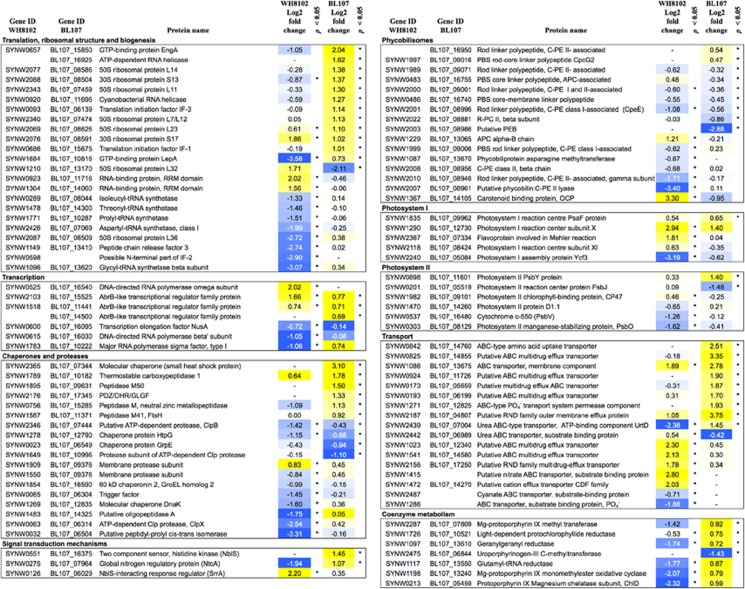

Protein biosynthesis machinery

In freshwater cyanobacteria, low temperature results in reduced transcription and translation efficiency. To compensate for lower efficiency, cells induce RNA polymerase subunits, sigma factors, RNA helicases, ribosomal proteins and initiation, elongation and anti-termination factors (Los and Murata, 1999; Suzuki et al., 2001). In the temperate strain BL107, most of the differentially expressed proteins involved in translation were upregulated at 18 °C relative to 22 °C (Figure 5). This increased expression may compensate for reduced protein synthesis efficiency and/or indicate the need for increased protein production and/or turnover for acclimation to low temperature (Suzuki et al., 2001).

Figure 5.

Differential expression of selected proteins at 18 °C in comparison with 22 °C in Synechococcus strains WH8102 (clade III) and BL107 (clade IV). Expression changes are given as log2 fold change (upregulation: yellow; downregulation: blue).

In strain WH8102, the majority of differentially expressed proteins involved in translation, ribosome structure and biogenesis were downregulated at 18 °C (Figure 5). Expression of proteins involved in transcription including elongation factor NusA, type I sigma factor and RNA polymerase beta' subunit was also reduced (Figure 5). Lower abundance of these proteins likely impairs protein synthesis and correlates with the lower growth rate observed in WH8102 at 18 °C. Alternative hypotheses for such downregulation could be increased protein stability at low temperature and/or increased efficiency of translation. Lower expression of chaperones and proteases (see below) may support the hypothesis of increased protein stability and less protein turnover at 18 °C. Increased translation efficiency in WH8102 at 18 °C does not seem likely due to impaired growth.

Both strains showed distinct differences in the expression of RNA helicases, ATPases that unwind RNA (Chamot et al., 1999). RNA helicase activity is important during environmental stress adaptation, particularly under low temperature conditions that can lead to stabilization of RNA secondary structures that impair protein synthesis (Yu and Owttrim, 2000; Hongsthong et al., 2008). In freshwater cyanobacteria, cold-inducible RNA helicases (such as those encoded by gene crhR) are regulated by redox state of the electron transport chain and have an important role in cold acclimation, through the modification of mRNA secondary structures (Chamot et al., 1999; Yu and Owttrim, 2000; Rosana et al., 2012). Two RNA helicases, BL107_16925 and BL107_11696 (crhR), are found in higher abundance in BL107 at 18 °C (Figure 5), with the latter also observed to be induced at the transcript level (Table 2). They may be essential for the maintenance of translation under low temperature conditions and important for adaptation of cyanobacteria to high latitude niches. Orthologs of BL107_16925 occur in the accessory genome of isolates from temperate clades I and IV, but not in tropical clades II and III. Although no RNA helicases are differentially expressed in strain WH8102 at 18 °C compared with 22 °C, two RNA-binding proteins (Rbps; SYNW0923, SYNW1364) are found at higher abundances (Figure 5). Some Rbps involved in RNA metabolism are known to be induced under low temperature stress and could have a role in RNA stability for the maintenance of translation (Los and Murata, 1999).

Table 2. Comparison of gene expression at the transcriptional and translational levels in Synechococcus strains WH8102 and BL107 grown at 18 °C relative to 22 °C.

| Target | Protein name |

Log2

fold change |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA (n=2) | Protein (n=3) | ||

| WH8102 | |||

| SYNW0213 | Protoporphyrin IX Mg-chelatase subunit, ChlD | 0.89 | −2.32 |

| SYNW0490 | ATP synthase, C chain | 0.83 | 2.09 |

| SYNW1367 | Carotenoid binding protein, OCP | 1.95 | 3.3 |

| SYNW1470 | Photosystem II protein D1.1 | 1.12 | −0.65 |

| SYNW2272 | NADH dehydrogenase I subunit, NdhG | 0.83 | 1.15 |

| BL107 | |||

| BL107_11696 | Cyanobacterial RNA helicase | 1 | 1.27 |

| BL107_16725 | ATP synthase A chain | 1.2 | 1.63 |

Note: This table includes only those genes that exhibit significant (>1.5- or <0.5-fold change) changes in expression at the transcript level. A complete list of tested genes are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Chaperones and proteases

Chaperones and proteases ensure proper folding of newly synthesized polypeptides and degradation of damaged and/or misfolded proteins. At low temperature for strain BL107, a small heat-shock protein (BL107_07344) and various proteases were induced suggesting greater protein turnover due to either higher protein synthesis or low temperature-induced misfolding (Figure 5). Trigger factor is a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase that associates with the ribosome and helps in the folding of newly synthesized polypeptides. It increases the affinity of GroEL for unfolded polypeptides. Trigger factor is a known cold-shock protein in Synechocystis (Chamot and Owttrim, 2000). Trigger factor, GroEL and eight other chaperones/proteases were reduced in expression in the tropical strain WH8102 (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S3).

Photosystems

At 18 °C compared with 22 °C, both strains differentially expressed subunits of PSI and PSII (Figure 5). In the temperate strain BL107, with the exception of two extrinsic subunits, none of the core PSII subunits was differentially expressed. In the tropical strain WH8102, low temperature appears to have a significant effect on the abundance of photosystem subunits. A core subunit of PSII, D1 protein was lower in abundance in strain WH8102 at 18 °C. Gene transcription levels determined through qRT-PCR indicate that there was an increase in the expression of the psbA gene, encoding D1, in strain WH8102 at 18 °C (Table 2). Lower abundance of D1 protein despite increased levels of the psbA transcript could indicate differences in the rate of degradation compared with the rate of protein synthesis. Mackey et al. (2013) and Pittera et al. (2014) have shown a similar decrease in D1 protein expression in tropical isolates at low temperatures correlating with lower growth rate.

D1 is sensitive to environmental stress and susceptible to photo-oxidative damage and requires replacement through a continuous repair cycle for the maintenance of photosynthesis (Huang et al., 2002). In freshwater cyanobacteria, to overcome low temperature-induced inhibition of the repair cycle, increased membrane fluidity and de novo protein synthesis are required (Kanervo et al., 1997; Suzuki et al., 2001; Murata et al., 2007; Tyystjärvi et al., 2001). As low temperature reduces membrane fluidity and decreases the level of translational proteins in strain WH8102, these could be causal factors in decreased D1 levels. The lowered abundance of D1 as well as the PSII subunits, PsbO and PsbV correlates with the reduced photosynthetic efficiency as determined through pulse-amplitude-modulation fluorometry.

In strain WH8102, two PSI subunits (PsaK and PsaL) and a flavoprotein involved in Mehler reaction have higher abundance at 18 °C compared with 22 °C while strain BL107 increased the abundance of one subunit PsaF. Over-reduction of PSII occurs under high light and/or low temperature. To avoid over-reduction, photosynthetic organisms increase the transfer of energy to PSI or dissipate energy as heat (Huner et al., 1998). In freshwater cyanobacterium, Synechocystis, PsaK is involved in increased transfer of energy from PBS to PSI under high light conditions, which aid in avoiding photodamage (Fujimori et al., 2005). The upregulation of PsaK in response to low temperature in WH8102 may have a similar role in protecting PSII from over-reduction.

Phycobilisomes

There was a significant decrease in PBS proteins at 18 °C in both WH8102 and BL107 (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S3). As qRT-PCR results indicate that there is no significant change in PBS gene expression (Supplementary Table S1), lowered abundance of PBS may be the result of protein degradation as reported previously (Mackey et al., 2013). Pittera et al. (2014) reported that under cold stress in tropical strains, there is reduced coupling between PBS rod phycobiliproteins possibly because of PE degradation while no change was observed in high latitude strains. This observation correlates with the reduced abundance of PE-related proteins observed in this study for tropical strain WH8102. However, PBS proteins are also lowered in abundance in the temperate strain BL107.

Coenzyme metabolism

In the category of coenzyme metabolism, five of seven differentially expressed proteins in strain WH8102 were downregulated while in strain BL107 seven of ten were upregulated (Figure 5; Supplementary Table S3). Many of these proteins are involved in porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism. Chlorophylls are essential for light absorption and energy transfer to reaction centers. They can also reduce the energy transferred through non-photochemical quenching, which aids in the prevention of photo-oxidative damage (Beale, 1999; Kirilovsky and Kerfeld, 2012). The availability of chlorophyll is important for the repair cycle of PSII (Hernandez-Prieto et al., 2011). The increased abundance of chlorophyll biosynthesis proteins in BL107 at colder temperatures may ensure the maintenance of chlorophyll supply providing the ability to cope with the imbalance in energy absorption and utilization caused by low temperature under constant light. The decreased abundance of these proteins in the tropical strain, WH8102 may be the result of increased efficiency in chlorophyll synthesis and/or a reduced requirement for chlorophyll but could likely be due to lowered translation since chlD (SYNW0213), encoding protoporphyrin IX magnesium chelatase, showed an increase in gene expression at the transcript level (Table 2).

Role of the accessory genome in growth at low temperatures

While genes required for protein biosynthesis, photosynthesis and metabolism are conserved across compared strains, their expression in response to low temperature is clearly different. This may be due to the influence of regulatory genes within the accessory genome, that is, genes that are unique to individual isolates or lineages. In temperate isolate BL107, seven proteins found at higher abundance at 18 °C are not conserved in the genome of strain WH8102. One of these is a transcriptional regulator (BL107_10951) while the remaining are a PBS rod linker polypeptide (BL107_16950), and five hypothetical proteins (BL107_05929, BL107_16580, BL107_16585, BL107_05389 and BL107_09511) (Supplementary Table S3). Accessory genes in Synechococcus have been suggested to provide a selective advantage under certain stress conditions, thus aiding in niche selection and adaptation (Ostrowski etal., 2010; Stuart et al., 2013; Tetu et al., 2013). The accessory proteins differentially expressed in this work may similarly contribute to acclimation and growth at low temperature.

Regulatory proteins

Several AbrB-like transcriptional regulators (three in BL107 and two in WH8102) were induced in both strains at 18 °C suggesting a potentially important role in low temperature acclimation (Figure 5). In Synechocystis PCC6803, AbrB transcriptional regulators are known to have a role in carbon and nitrogen uptake and metabolism (Ishii and Hihara, 2008; Kaniya et al., 2013). These regulators may be involved in metabolic adjustments to low temperature.

Hik33 (NblS) is a histidine kinase involved in perceiving various environmental signals including temperature in cyanobacteria. The signal is perceived through changes in photosynthetic redox state and/or membrane fluidity (Suzuki et al., 2001; Scanlan et al., 2009; Lopéz-Redondo et al., 2010). Hik33 was induced in temperate strain BL107 at 18 °C (Figure 5). Though Hik33 was not detected in WH8102, a response regulator, SrrA that interacts with Hik33 was induced at 18 °C (Figure 5). In Synechocystis PCC7942, srrA gene is induced transiently under high light and is involved in regulating PBS expression (Lopéz-Redondo et al., 2010).

The cell division protein SulA was induced in WH8102 (Supplementary Table S3). In Escherichia coli, this protein is part of the SOS response inhibiting cell division and enabling DNA repair (Cordell et al, 2003). In Synechocystis, SulA is required for cell division and is crucial for cell survival (Raynoud et al., 2004). The induction of SulA in WH8102 suggests a role in low temperature stress.

Membrane transport

Both strains increased expression of proteins involved in membrane transport at 18 °C compared with 22 °C which could be due to the influence of low temperature on the efficiency of nutrient acquisition and/or an increased nutrient requirement (Figure 5). At low temperature, nitrate assimilation efficiency is lowered in freshwater Synechococcus species while reduced nitrogen sources such as urea help maintain growth (Sakamoto and Bryant, 1998, 1999). The temperate isolate BL107 induced two proteins involved in urea transport and metabolism along with global nitrogen regulatory protein (NtcA) (Figure 5). In other cyanobacteria and Synechococcus strain WH7805, regulation of genes involved in urea metabolism by NtcA have been reported (Collier et al., 1999; Palenik, 2015). Though the tropical isolate WH8102 induced a putative nitrate transporter (SYNW1415) and urea transporter (substrate-binding subunit, SYNW2442), expression of urea transporter (ATP-binding subunit, SYNW2439) was highly reduced (Figure 5). Increased expression of efflux transporters at 18 °C could imply a defense mechanism against a buildup of toxic metabolites under low temperature stress. Alternatively, these may act as lipid transporters and be involved in membrane composition changes at low temperature.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that Synechococcus isolates of clades I–IV exhibit temperature preferences. Their growth physiology is consistent with the environmental distribution of these clades reported in the previous studies (Zwirglmaier et al., 2007, 2008; Ahlgren and Rocap, 2012; Huang et al., 2012; Sohm et al., 2015). Growth rates were marginally lower at low temperature in strains of clade I (CC9311) and IV (BL107, CC9902), which are dominant in temperate regions. For strains of clade II (CC9605, WH8109) and III (WH8102) that are predominant in (sub) tropical regions, growth was severely affected at low temperature. Membrane lipid composition in cyanobacteria has been reported to be important in stress adaptation (Van Mooy et al., 2006) and alteration of membrane fluidity is crucial during temperature fluctuations. This work provides the first comparative analyses of lipid composition between marine Synechococcus isolates. Temperate strain BL107 has a higher level of unsaturated fatty acid content than tropical strains WH8102 and WH8109. Strain BL107 further increases the level of unsaturation at low temperature thus potentially enabling better adaptability. Higher level of saturated fatty acid content in tropical isolates WH8102 and WH8109 is likely significant in their inability to acclimate to low temperature. This study highlights differences in low temperature adaptive capacities between isolates of clades III (WH8102) and IV (BL107) at the level of protein expression. The tropical strain WH8102 has a lower abundance of several PSII subunits and proteins involved in translation, which may be in response to slower growth. In contrast, temperate strain BL107 induces the expression of important components of the translational machinery potentially aiding acclimation at low temperature. Thus, the maintenance of protein biosynthesis, membrane fluidity and photosynthetic efficiency in temperate strain BL107 enables the cells to meet the energy requirements for growth at low temperature. Specific proteins in BL107 that are absent from WH8102, such as the RNA helicase, fatty acid desaturase and transcriptional regulator, may be important in the ability of clade IV strains to successfully colonize high latitude niches. The ability to adapt and maintain growth under lower temperatures would provide clade I and IV isolates with a competitive advantage over clade II and III isolates in higher latitudes and explain their dominance in these cold waters. More work is required to understand the eco-physiology of the increasing number of distinct lineages found in different ocean regimes. The relationships between local changes in temperature, stratification and atmospheric CO2 concentrations as a consequence of global climate change could be quite complex. Caution is needed when generalizing responses to global change scenarios as individual picocyanobacterial lineages may respond quite differently. Global proteomic studies will be a useful approach to determine whether the observed thermal acclimation and adaptations in these strains can be more generally applied, and whether additional thermal acclimation strategies exist in marine cyanobacteria lineages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP110102718 and Laureate Fellowship FL40100021 to ITP, and an International Postgraduate Research Scholarship to DV from the Australian government. We thank DJ Scanlan and FD Pitt, University of Warwick, UK for providing the Synechococcus strains.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Ahlgren N, Rocap G. (2006). Culture isolation and culture-independent clone libraries reveal new marine Synechococcus ecotypes with distinctive light and N physiologies. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 7193–7204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren N, Rocap G. (2012). Diversity and distribution of marine Synechococcus: multiple gene phylogenies for consensus classification and development of qPCR assays for sensitive measurement of clades in the ocean. Front Microbiol 3: 1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beale S. (1999). Enzymes of chlorophyll biosynthesis. Photosynth Res 60: 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chamot D, Magee W, Yu E, Owttrim G. (1999). A cold shock-induced cyanobacterial RNA helicase. J Bacteriol 181: 1728–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamot D, Owttrim G. (2000). Regulation of cold shock-induced RNA helicase gene expression in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 182: 1251–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier J, Brahamsha B, Palenik B. (1999). The marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH7805 requires urease (urea amidohydrolase, EC 3.5.1.5) to utilize urea as a nitrogen source: molecular-genetic and biochemical analysis of the enzyme. Microbiology 145: 447–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell S, Robinson E, Lowe J. (2003). Crystal structure of the SOS cell division inhibitor SulA and in complex with FtsZ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 7889–7894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R, Beavis R. (2003). A method for reducing the time required to match protein sequences with tandem mass spectra. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 17: 2310–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R, Beavis R. (2004). TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20: 1466–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne A, Ostrowski M, Scanlan D, Garczarek L, Mazard S, Palenik B et al. (2008). Unraveling the genomic mosaic of a ubiquitous genus of marine cyanobacteria. Genome Biol 9: R90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T, Hihara Y, Sonoike K. (2005). PsaK2 subunit in photosystem I is involved in state transition under high light in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J Biol Chem 280: 22191–22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller N, Marie D, Partensky F, Vaulot D, Post A, Scanlan D. (2003). Clade-specific 16S ribosomal DNA oligonucleotides reveal the predominance of a single marine Synechococcus clade throughout a stratified water column in the Red Sea. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 2430–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammulla C, Pascovici D, Atwell B, Haynes P. (2010). Differential metabolic response of cultured rice (Oryza sativa cells exposed to high and low-temperature stress. Proteomics 10: 3001–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garczarek L, Dufresne A, Blot N, Cockshutt A, Peyrat A, Campbell D et al. (2008). Function and evolution of the psbA gene family in marine SynechococcusSynechococcus sp. WH7803 as a case study. ISME J 2: 937–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombos Z, Wada H, Murata N. (1994). The recovery of photosynthesis from low-temperature photoinhibition is accelerated by the unsaturation of membrane lipids: A mechanism of chilling tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8787–8791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman M, Castenholz R, Iteman I, Waterbury J, Rippka R. (2001). Subsection I (Formerly Chroococcales Wettstein 1924, emend. Rippka, Deruelles, Waterbury, Herdman and Stanier 1979). In Boone D, Castenholz R, Garrity G eds Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology vol 1, 2nd edn, The archaea and the deeply branching and phototrophic bacteria Springer: New York, NY, USA, pp 493–514. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Prieto M, Tibiletti T, Abasova L, Kirilovsky D, Vass I, Funk C. (2011). The small CAB-like proteins of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: Their involvement in chlorophyll biogenesis for Photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807: 1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongsthong A, Sirijuntarut M, Prommeenate P, Lertladaluck K, Porkaew K, Cheevadhanarak S et al. (2008). Proteome analysis at the subcellular level of the cyanobacterium Spirulina platensis in response to low-temperature stress conditions. FEMS Microbiol Lett 288: 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Parmryd I, Nilsson F, Persson A, Pakrasi H, Andersson B et al. (2002). Proteomics of Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803. Mol Cell proteomics 1: 956–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Wilhelm S, Harvey H, Taylor K, Jiao N, Chen F. (2012). Novel lineages of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus in the global oceans. ISME J 6: 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huner N, Öquist G, Sarhan F. (1998). Energy balance and acclimation to light and cold. Trends Plant Sci 3: 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Hihara Y. (2008). An AbrB-like transcriptional regulator, Sll0822, is essential for the activation of nitrogen-regulated genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 148: 660–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanervo E, Tasaka Y, Murata N, Aro E. (1997). Membrane lipid unsaturation modulates processing of the photosystem II reaction-center protein D1 at low temperatures. Plant Physiol 114: 841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniya Y, Kizawa A, Miyagi A, Kawai-Yamada M, Uchimiya H, Kaneko Y et al. (2013). Deletion of the transcriptional regulator cyAbrB2 deregulates primary carbon metabolism in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 162: 1153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilovsky D, Kerfeld C. (2012). The orange carotenoid protein in photoprotection of photosystem II in cyanobacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1817: 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K, Schmittgen T. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopéz-Redondo M, Moronta F, Salinas P, Espinosa J, Cantos R, Dixon R et al. (2010). Environmental control of phosphorylation pathways in a branched two-component system. Mol Microbiol 78: 475–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los D, Murata N. (1999). Responses to cold shock in cyanobacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 1: 221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey K, Paytan A, Caldeira K, Grossman A, Moran D, McIlvin M et al. (2013). Effect of temperature on photosynthesis and growth in marine Synechococcus spp. Plant Physiol 163: 815–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides M, Neumann M, Gibson R. (1996). Effect of maternal docosahexanoic acid (DHA) supplementation on breast milk composition. Eur J Clin Nutr 50: 352–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazard S, Ostrowski M, Partensky F, Scanlan D. (2012). Multi-locus sequence analysis, taxonomic resolution and biogeography of marine Synechococcus. Environ Microbiol 14: 372–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mella-Flores D, Mazard S, Humily F, Partensky F, Mahé F, Bariat L et al. (2011). Is the distribution of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus ecotypes in the Mediterranean Sea affected by global warming? Biogeosciences 8: 2785–2804. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M, Pascovici D, Keighley T, George I, Voelckel C, Heenan P et al. (2011). Shotgun proteomic profiling of five species of New Zealand Pachycladon. Proteomics 11: 166–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M, Soltani N, Sarhadi E, Pascovici D, Keighley T, Salekdeh G et al. (2012). Shotgun proteomic analysis of long-distance drought signaling in rice roots. J Proteome Res 11: 348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel F, Rueter J, Anderson D, Guillard R. (1979). Aquil: a chemically defined phytoplankton culture medium for trace metal studies. J Phycol 15: 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley A, Florens L, Wen Z, Washburn M. (2009). A label free quantitative proteomic analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae nucleus. J Proteomics 72: 110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata N, Los D. (1997). Membrane fluidity and temperature perception. Plant Physiol 115: 875–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata N, Takahashi S, Nishiyama Y, Allakhverdiev S. (2007). Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1767: 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson K, George I, Emery S, Muralidharan S, Mirzaei M, Haynes P. (2014). Analysis of rice proteins using SDS-PAGE shotgun proteomics Jorrin-Novo JV, Komatsu S, Weckwerth W, Wienkoop S (eds). Plant Proteomics: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology. Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, pp 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Tetu S, Phillippy K, Johnson A, Palenik B et al. (2010). PtrA is required for coordinate regulation of gene expression during phosphate stress in a marine Synechococcus. ISME J 4: 908–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paerl R, Foster R, Jenkins B, Montoya J, Zehr J. (2008). Phylogenetic diversity of cyanobacterial narB genes from various marine habitats. Environ Microbiol 10: 3377–3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palenik B. (2015). Molecular mechanisms by which marine phytoplankton respond to their dynamic chemical environment. Annu Rev Mar Sci 7: 325–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palenik B, Brahamsha B, Larimer F, Land M, Hauser L, Chain P et al. (2003). The genome of a motile marine Synechococcus. Nature 424: 1037–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palenik B, Ren Q, Tai V, Paulsen I. (2009). Coastal Synechococcus metagenome reveals major roles for horizontal gene transfer and plasmids in population diversity. Environ Microbiol 11: 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penno S, Lindell D, Post A. (2006). Diversity of Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus populations determined from DNA sequences of the N-regulatory gene ntcA. Environ Microbiol 8: 1200–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittera J, Humily F, Thorel M, Grulois D, Garczarek L, Six C. (2014). Connecting thermal physiology and latitudinal niche partitioning in marine Synechococcus. ISME J 8: 1221–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post A, Penno S, Zandbank K, Paytan A, Huse S, Welch D. (2011). Long term seasonal dynamics of Synechococcus population structure in the Gulf of Aqaba, Northern Red Sea. Front Microbiol 2: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud C, Cassier-Chauvat C, Perennes C, Bergounioux C. (2004). An Arabidopsis homolog of the bacterial cell division inhibitor SulA is involved in plastid division. Plant Cell 16: 1801–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosana A, Chamot D, Owttrim G. (2012). Autoregulation of RNA helicase expression in response to temperature stress in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS One 7: e48683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T, Bryant D. (1998). Growth at low temperature causes nitrogen limitation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Arch Microbiol 169: 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto T, Bryant D. (1999). Nitrate transport and not photoinhibition limits growth of the freshwater cyanobacterium Synechococcus species PCC 6301 at low temperature. Plant Physiol 119: 785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan D, Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Dufresne A, Garczarek L, Hess W et al. (2009). Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73: 249–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan D. (2012) Marine picocyanobacteria. In Whitton BA (ed.), Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time. Springer Science + Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp 503–533. [Google Scholar]

- Sohm JA, Ahlgren N, Thomson ZJ, Williams C, Moffett JW, Saito MA et al. (2015). Co-occurring Synechococcus ecotypes occupy four major oceanic regimes defined by temperature, macronutrients and iron. ISME J e-pub ahead of print 24 July 2015 doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stuart R, Brahamsha B, Busby K, Palenik B. (2013). Genomic island genes in a coastal marine Synechococcus strain confer enhanced tolerance to copper and oxidative stress. ISME J 7: 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Mao F, Dam P, Wu H, Olman V, Paulsen I et al. (2006). Computational inference and experimental validation of the nitrogen assimilation regulatory network in cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH 8102. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 1050–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki I, Kanesaki Y, Mikami K, Kanehisa M, Murata N. (2001). Cold-regulated genes under the control of the cold sensor Hik33 in Synechocystis. Mol Biol 40: 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandeau de Marsac N, Cohen-Bazire G. (1977). Molecular composition of cyanobacterial phycobilisomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74: 1635–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R, Fedorova N, Jackson J, Jacobs A, Kiryutin B, Koonin E et al. (2003). The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetu S, Johnson D, Varkey D, Phillippy K, Stuart R, Dupont C et al. (2013). Impact of DNA damaging agents on genome-wide transcriptional profiles in two marine Synechococcus species. Front Microbiol 4: 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyystjärvi T, Herranen M, Aro E. (2001). Regulation of translation elongation in cyanobacteria: Membrane targeting of the ribosome nascent-chain complexes controls the synthesis of D1 protein. Mol Microbiol 40: 476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth B, Remm M et al. (2012). Primer3—new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbach E, Scanlan D, Distel D, Waterbury J, Chisholm S. (1998). Rapid diversification of marine picophytoplankton with dissimilar light-harvesting structures inferred from sequences of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (Cyanobacteria). J Mol Evol 46: 188–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mooy B, Rocap G, Fredricks H, Evans C, Devol A. (2006). Sulfolipids dramatically decrease phosphorus demand by picocyanobacteria in oligotrophic marine environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 8607–8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno J, Cote R, Csordas A, Dianes J, Fabregat A, Foster J et al. (2013). The Proteomics Identifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D1063–D1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno J, Deutsch E, Wang R, Csordas A, Reisinger F, Ríos D et al. (2014). ProteomeXchange provides globally co-ordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nature Biotechnol 30: 223–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Gombos Z, Murata N. (1994). Contribution of membrane lipids to the ability of the photosynthetic machinery to tolerate temperature stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 4273–4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel D, Flügge U. (1984). A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal Biochem 138: 141–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu E, Owttrim G. (2000). Characterization of the cold stress-induced cyanobacterial DEAD-box protein CrhC as an RNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 3926–3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwirglmaier K, Heywood J, Chamberlain K, Woodward E, Zubkov M, Scanlan D. (2007). Basin-scale distribution patterns of picocyanobacterial lineages in the Atlantic Ocean. Environ Microbiol 9: 1278–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwirglmaier K, Jardillier L, Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Garczarek L, Vaulot D et al. (2008). Global phylogeography of marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus reveals a distinct partitioning of lineages among oceanic biomes. Environ Microbiol 10: 147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zybailov B, Mosley A, Sardiu M, Coleman M, Florens L, Washburn M. (2006). Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res 5: 2339–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.