Abstract

A wide array of cross-coupling methods for the formation of C–C bonds from unactivated alkyl electrophiles have been described in recent years. In contrast, progress in the development of methods for the construction of C–heteroatom bonds has lagged; for example, there have been no reports of metal-catalyzed cross-couplings of unactivated secondary or tertiary alkyl halides with silicon nucleophiles to form C–Si bonds. In this study, we address this challenge, establishing that a simple, commercially available nickel catalyst (NiBr2·diglyme) can achieve couplings of alkyl bromides with nucleophilic silicon reagents under unusually mild conditions (e.g., −20 °C); especially noteworthy is our ability to employ unactivated tertiary alkyl halides as electrophilic coupling partners, which is still relatively uncommon in the field of cross-coupling chemistry. Stereochemical, relative-reactivity, and radical-trap studies are consistent with a homolytic pathway for C–X bond cleavage.

Graphical abstract

Organosilicon compounds play an important role not only in organic chemistry,1 but also in fields ranging from materials science2 to agrochemistry3 to medicinal chemistry.4 For example, in the pharmaceutical industry, the investigation of silicon analogues of known drugs, as well as of entirely new silicon-containing molecules, has become an active area of research.4

Two of the most common methods for the synthesis of tetraorganosilanes, each of which has significant limitations, are outlined in Figures 1(a) and 1(b).5 In the case of the hydrosilylation of olefins (Figure 1(a)), issues of reactivity (e.g., hindered substrates) and regioselectivity (e.g., 1,2-disubstituted olefins) can present significant challenges.6,7 In the case of the coupling of an organic nucleophile with a silicon electrophile (Figure 1(b)),8 this approach has rarely proved to be effective for secondary or for tertiary alkylmetal reagents.9.10

Figure 1.

Three approaches to the synthesis of tetraorganosilanes.

In principle, the umpolung variant of Figure 1(b), i.e., the coupling of an alkyl electrophile with a silicon nucleophile (Figure 1(c)), could provide an attractive approach to the synthesis of tetraorganosilanes. In practice, however, progress has been rather limited. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, catalyzed methods have been restricted to couplings of activated alkyl electrophiles (e.g., allylic, benzylic, and propargylic),11 with the exception of a single study that reports the cross-coupling of disilanes with methyl and ethyl (but not n-propyl) halides catalyzed either by palladium (up to 92% yield at 110 °C) or by nickel (up to 48% yield at 110 °C).12,13

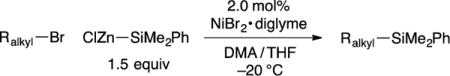

During the past years, we have devoted considerable effort to the development of metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles.14 Initially, we focused on the use of carbon nucleophiles to effect C–C bond formation, but recently we have turned our attention to the construction of C–heteroatom bonds. In 2012, we reported our first success in addressing this challenge, specifically, the coupling of alkyl halides with diboron compounds to generate alkylboranes (C–B bond formation).15,16 In the interim, we have continued to pursue the possibility that versatile methods can be developed for the construction of other C–X bonds, and we describe herein our progress with respect to C–Si bond formation. In particular, we establish that commercially available NiBr2·diglyme, without an added ligand, catalyzes the cross-coupling of an array of unactivated secondary and tertiary alkyl electrophiles with silicon nucleophiles under mild conditions (eq 1).

|

(1) |

In initial studies, we applied the conditions that we had developed for the borylation of alkyl halides with pinB–Bpin (pin = pinacolato)15 to the corresponding silylation with pinB–SiMe2Ph (eq 2). Unfortunately, we obtained only a trace of the desired alkylsilane (<1%). Furthermore, our attempts to increase the efficiency of C–Si bond formation with this reagent were unsuccessful.

|

(2) |

We therefore turned our attention to the use of other silicon nucleophiles, and we determined that a silylzinc halide17 can serve as a suitable coupling partner under the appropriate conditions (Table 1). Thus, in the presence of 2.0 mol% of NiBr2·diglyme, the cross-coupling of an unactivated secondary alkyl bromide with ClZn–SiMe2Ph can be achieved in good yield under remarkably mild conditions (−20 °C, 84% yield; entry 1). ClZn–SiMe2Ph can be prepared via Li–SiMe2Ph using standard Schlenk techniques and, if desired, stored under nitrogen at −35 °C for at least one month without deterioration.

Table 1.

Silylation of an Unactivated Secondary Alkyl Bromide: Effect of Reaction Parameters

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from the “standard” conditions | yield (%)a |

| 1 | none | 84 |

| 2 | no NiBr2·diglyme | <1 |

| 3 | Li–SiMe2Ph, instead of ClZn–SiMe2Ph | 2 |

| 4 | ClMg–SiMe2Ph, instead of ClZn–SiMe2Ph | 1 |

| 5 | FeCl2, instead of NiBr2·diglyme | <1 |

| 6 | CoCl2, instead of NiBr2·diglyme | 2 |

| 7 | CuBr·SMe2, instead of NiBr2·diglyme | <1 |

| 8 | Pd(MeCN)2Cl2, instead of NiBr2·diglyme | <1 |

| 9 | no DMA | 1 |

| 10 | 0.5 mol% NiBr2·diglyme | 60 |

| 11 | 1.1 equiv ClZn–SiMe2Ph | 78 |

| 12 | r.t., instead of −20 °C | 73 |

| 13 | under air in a closed vial | 69 |

| 14 | added H20 (2.0 equiv) | 78 |

Yields were determined by GC analysis with the aid of a calibrated internal standard (average of two experiments).

Essentially no C–Si bond formation is observed in the absence of the nickel catalyst (entry 2). Under these conditions, the other silicon nucleophiles that we have examined are not useful coupling partners (e.g., entries 3 and 4), and an array of complexes of other transition metals do not serve as effective catalysts (entries 5–8).18 The use of a mixture of DMA and THF as the solvent is important (entry 9).19 If the cross-coupling is conducted with less catalyst or with less nucleophile, or at room temperature, there is a small deleterious effect on the yield (entries 10–12). The method is not highly air- or moisture-sensitive (entries 13 and 14). This is the first nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of alkyl electrophiles that we have developed that does not require an added ligand.

NiBr2·diglyme is an effective catalyst for the silylation of an array of unactivated secondary alkyl bromides at −20 °C (Table 2).20 Thus, C–Si bond formation proceeds in good yield with hindered (entries 2 and 3) and with functionalized (entries 4–10) electrophiles. The method is compatible not only with an ether, a carbamate, an aniline, a sulfonamide, an aryl chloride, and an ester, but also with heterocycles such as a furan and an indole; however, in a preliminary study, an electrophile that included a thiophene was not a useful coupling partner, nor was an unactivated secondary alkyl chloride or tosylate (<2% yield). On a gram scale, the cross-coupling illustrated in entry 1 of Table 2 proceeds in 81% yield in the presence of 1.0 mol% NiBr2·diglyme. Finally, we have determined that our standard conditions for the silylation of secondary alkyl bromides can also be applied to the silylation of a corresponding iodide (eq 3).21

|

(3) |

Table 2.

Silylation of Unactivated Secondary Alkyl Bromides: Scope

Yield of purified product (average of two experiments).

Catalyst loading: 5.0 mol% NiBr2·diglyme.

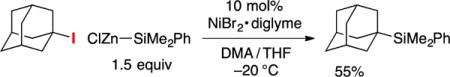

Although considerable progress has been described in recent years in the discovery of methods for the cross-coupling of unactivated secondary alkyl electrophiles, advances in the case of tertiary electrophiles have been rather limited.22 We were therefore pleased to determine that the simple standard conditions that we have developed for silylations of secondary alkyl bromides can be applied directly to tertiary bromides, with the only difference being the use of a higher catalyst loading (10 mol%; Table 3). Both acyclic (entries 1–3) and cyclic (entries 4–6) unactivated tertiary alkyl bromides serve as suitable cross-coupling partners. A preliminary attempt to silylate a tertiary alkyl iodide under the same conditions provided a promising result (eq 4).

|

(4) |

Table 3.

Silylation of Unactivated Tertiary Alkyl Bromides: Scope

Yield of purified product (average of two experiments).

Catalyst loading: 2.0 mol% NiBr2·diglyme.

Having established that the scope of this new C–Si bond-forming process is broad with respect to the electrophile, we shifted our focus to examining the use of other silicon nucleophiles. We have determined that, in the presence of 10 mol% NiBr2·diglyme, other silylating agents also serve as effective cross-coupling partners (eq 5).

|

(5) |

Our working hypothesis is that C–Br bond cleavage in these silylation reactions proceeds through a radical intermediate, as for our previous nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of unactivated alkyl halides to generate C–C and C–B bonds,15,23 and this suggestion is supported by our preliminary mechanistic studies. For example, exo- and endo-2-bromonorbornane react to afford the same mixture of diastereomers (7:1 exo:endo; eq 6 and eq 7; at partial conversion, each alkyl bromide remains a single stereoisomer), consistent with a common intermediate in the two cross-couplings.

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

We have examined the relative reactivity of alkyl bromides as a function of the level of substitution of the carbon that bears bromine (eq 8 and eq 9). If the stability of the radical is the dominant factor, then the anticipated ordering would be: tertiary > secondary > primary; if, on the other hand, steric effects are dominant, then the expected ordering would be: tertiary < secondary < primary. Through competition experiments, we have determined that more substituted alkyl bromides are more reactive, consistent with the generation of a radical intermediate in the C–X cleavage step.24 Furthermore, the addition of 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxyl (TEMPO), which can rapidly trap alkyl radicals,25 inhibits C–Si bond formation.26

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

In conclusion, we have described the first metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of unactivated secondary and tertiary alkyl electrophiles to form C–Si bonds, thus expanding such nickel-catalyzed couplings beyond the construction of C–C and C–B bonds. With the aid of a simple, commercially available catalyst, both secondary and tertiary alkyl bromides react with silicon nucleophiles under unusually mild conditions (e.g., −20 °C) to furnish alkylsilanes in good yield; a variety of functional groups are compatible with the method. Stereochemical and reactivity studies are consistent with a radical pathway for C–X cleavage in this new bond-forming process. Additional efforts to expand the scope of metal-catalyzed coupling processes are underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences: R01–GM62871) and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis). We thank Dr. Alexander S. Dudnik for preliminary observations and Dr. Junwon Choi for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Fuchs PL, editor. Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis: Reagents for Silicon-Mediated Organic Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auner N, Weis J, editors. Organosilicon Chemistry V: From Molecules to Materials. Wiley–VCH; Weinhiem, Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flusilazole, silthiofam, and simeconazole are examples of tetraorganosilanes that are employed in the agrochemical industry.

- 4.For a recent review with leading references, see:; Franz AK, Wilson SO. J Med Chem. 2013;56:388–405. doi: 10.1021/jm3010114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The development of new strategies for the synthesis of organosilanes continues to be an active area of research. For an example of the synthesis of organosilanes (allylsilanes and vinylsilanes) through a silyl-Heck approach, see:; McAtee JR, Martin SES, Ahneman DT, Johnson KA, Watson DA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:3663–3667. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For overviews of recent advances, as well as leading references, see:; (a) Nakajima Y, Shamada S. RSC Advances. 2015;26:20603–20616. [Google Scholar]; (b) Troegel D, Stohrer J. Coord Chem Rev. 2011;255:1440–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) For a recent example of isomerization during the hydrosilylation of internal olefins, see:; Buslov I, Becouse J, Mazza S, Montandon-Clerc M, Hu X. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:14523–14526. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) For an example of poor regioselectivity in the hydrosilylation of internal olefins, see:; Benkeser RA, Muench WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:285–286. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For leading references, see:; Science of Synthesis. Vol. 4. Georg Theime Verlag; Stuttgart, Germany: 2002. Chapter 4.4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.We are aware of only a few examples, most of which proceed in low yield and/or involve special (reactive) coupling partners. See:; (a) Bréfort J-L, Corriu RJP, Guérin C, Henner BJL, Man WWCWC. Organometallics. 1990;9:2080–2085. [Google Scholar]; (b) Itami K, Terakawa K, Yoshida J-i, Kajimoto O. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6058–6059. doi: 10.1021/ja034227g. (one example reported on page S6 of the Supporting Information: 22% yield) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Eisch JJ, Gupta G. J Organomet Chem. 1979;168:139–157. (cyclopropylMgBr as the nucleophile, 37% yield) [Google Scholar]; (d) Kang K-T, Yoon UC, Seo HC, Kim KN, Song HY, Lee JC. Bull Korean Chem Sci. 1991;12:57–60. (a silacyclobutane as the electrophile) [Google Scholar]

- 10.For an example of an unsuccessful coupling (0% yield), see:; Murakami K, Hirano K, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5833–5835. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For selected examples, see:; (a) Lefort M, Simmonet C, Birot M, Deleris G, Dunogues J, Calas R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:1857–1860. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tobisu M, Kita Y, Ano Y, Chatani N. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15982–15989. doi: 10.1021/ja804992n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vyas DJ, Oestreich M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8513–8515. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hazra CK, Oestreich M. Org Lett. 2012;14:4010–4013. doi: 10.1021/ol301827t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zarate C, Martin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2236–2239. doi: 10.1021/ja412107b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Huang Z-D, Ding R, Wang P, Xu Y-H, Loh T-P. Chem Commun. 2016;52:5609–5612. doi: 10.1039/c6cc00713a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaborn C, Griffiths RW, Pidcock A. J Organomet Chem. 1982;225:331–341. [Google Scholar]; After the submission of our study, a report of copper-catalyzed silylation of primary alkyl triflates was described:; Scharfbier J, Oestreich M. Synlett. 2016;27:1274–1276. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For related work, see: (a)copper-catalyzed couplings that proceed in low (<40%) yield:; Okuda Y, Morizawa Y, Oshima K, Nozaki H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:2483–2486. [Google Scholar]; (b) rhodium-catalyzed substitution of a cyano group with a silyl group (48% yield): Ref 11b.

- 14.(a) For an early report, see:; Netherton MR, Dai C, Neuschütz K, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10099–10100. doi: 10.1021/ja011306o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) For a recent report and leading references, see:; Liang Y, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:9523–9526. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudnik AS, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10693–10697. doi: 10.1021/ja304068t. (nickel catalyst; primary, secondary, and tertiary electrophiles) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For contemporaneous work by others, see:; (a) Yang C-T, Zhang Z-Q, Tajuddin H, Wu C-C, Liang J, Liu J-H, Fu Y, Czyzewska M, Steel PG, Marder TB, Liu L. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:528–532. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106299. (copper catalyst; primary and secondary electrophiles) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito H, Kubota K. Org Lett. 2012;14:890–893. doi: 10.1021/ol203413w. (copper catalyst; primary and secondary electrophiles) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yi J, Liu J-H, Liang J, Dai J-J, Yang C-T, Fu Y, Liu L. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:1685–1691. (palladium and nickel catalysts; primary and secondary electrophiles) [Google Scholar]; (d) Joshi-Pangu A, Ma X, Diane M, Iqbal S, Kribs RJ, Huang R, Wang C-Y, Biscoe MR. J Org Chem. 2012;77:6629–6633. doi: 10.1021/jo301156e. (palladium catalyst; primary electrophiles) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemeon I, Singer RD. Science of Synthesis. Vol. 4. Georg Theime Verlag; Stuttgart, Germany: 2002. Chapter 4.4.9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2656–2670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preliminary studies indicate that a lower yield of cross-coupling product is observed if less than ~20 equiv of DMA is present. Possible roles for DMA include binding to nickel or increasing the dielectric constant of the reaction medium.

- 20.Notes: (a) Small amounts of products derived from hydrodebromination of the electrophile or from homocoupling of the nucleophile are sometimes observed. (b) Under our standard conditions, the addition of ligand 1 is deleterious for cross-coupling.

- 21.We have not yet attempted to separately optimize the yield for this family of electrophiles.

- 22.For selected examples of cross-couplings of unactivated tertiary alkyl halides, see:; (a) Tsuji T, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:4137–4139. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021104)41:21<4137::AID-ANIE4137>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mitamura Y, Asada Y, Murakami K, Someya H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. Chem Asian J. 2010;5:1487–1493. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ref 15; (d) Zultanski SL, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:624–627. doi: 10.1021/ja311669p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wu X, See JWT, Xu K, Hirao H, Roger J, Hierso J-C, Zhou J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:13573–13577. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; See also:; (f) Wang X, Wang S, Xue W, Gong H. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11562–11565. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.For recent discussions and leading references, see:; (a) Liang Y, Fu GC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:9047–9051. doi: 10.1002/anie.201503297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schley ND, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:16588–16593. doi: 10.1021/ja508718m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.We have observed similar trends in nickel-catalyzed borylations of unactivated alkyl bromides: Ref 15.

- 25.Henry-Riyad H, Montanari F, Quici S, Studer A, Tidwell TT, Vogler T. In: Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis. Fuchs PL, editor. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2013. pp. 620–626. [Google Scholar]

- 26.For details, see the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.