Abstract

Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is associated with a higher mortality and an increased risk on exacerbations compared to COPD patients without PH. The aim was to evaluate the diagnostic value of pulmonary artery (PA) measurements on chest computed tomography (CT) for PH in end-stage COPD.

Methods

COPD patients evaluated for eligibility for lung transplantation between 2004 and 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Clinical characteristics, chest CTs, spirometry, and right-sided heart catheterizations (RHC) were studied. Diameters of PA and ascending aorta (A) were measured on CT. Diagnostic properties of different cut-offs of PA diameter and PA:A ratio in diagnosing PH were calculated.

Results

Of 92 included COPD patients, 30 (32.6 %) had PH at RHC (meanPAP > 25 mm Hg). PA:A > 1 had a negative predictive value (NPV) of 77.9 % and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 63.1 % with an odds ratio (OR (CI 95 %)) of 5.60 (2.00–15.63). PA diameter ≥30 mm had a NPV of 78 % and PPV of 64 % with an OR (CI 95 %) of 6.95 (2.51–19.24).

Conclusion

A small PA diameter and PA:A make the presence of PH unlikely but cannot exclude its presence in end-stage COPD. A large PA diameter and PA:A maybe used to detect PH early.

Keywords: COPD, Pulmonary circulation and pulmonary hypertension, Radiology and other imaging

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide, and estimates show that COPD will become the third leading cause of death in 2030 [1, 2]. Pulmonary hypertension (PH), defined as a mean pulmonary artery (PA) pressure (meanPAP) of >25 mmHg, is a relatively common and important complication in patients with severe COPD [1–4]. PH in COPD is mainly associated with degree of hypoxemia which causes pulmonary vascular constriction and increased precapillary vascular pressure with vascular remodeling. Histopathology demonstrated that the severity of PH correlates with pathologic vascular lesions in pulmonary arteries [5]. PH increases the risk of hospitalization and is associated with a reduced life expectancy [6–8]. Around half of all COPD patients will develop PH and consequently patients with PH tend to have an increased risk on exacerbations, which in turn leads to a greater mortality [9–11]. Moreover, PH is related to a reduced transplant free survival rate [12, 13].

Diagnosing PH remains a challenging clinical problem due to the nonspecific nature of the symptoms. PH-related symptoms like fatigue and exercise-induced dyspnea are often encountered in patients with severe COPD and therefore nonspecific. As a consequence most of the COPD patients are diagnosed with PH by the time the disease already is in an advanced stage [14, 15]. For an adequate treatment early detection is preferable [16, 17]. The gold standard for PH is right heart catheterization (RHC) [17]. However, RHC is invasive, makes use of iodine contrast, and exposes the patient to relatively high radiation doses [17]. A noninvasive tool frequently used in diagnosing PH is echocardiography, but in patients with advanced COPD it showed to be inherently inaccurate due to hyperinflation of the thorax [18, 19].

The routine clinical work-up and follow-up of end-stage COPD patients being screened for lung transplantation includes a chest CT scan. CT scans in end-stage COPD are also often made for a variety of purposes like unexplained acute dyspnea. In this light, a possible diagnostic marker, the PA diameter or the PA to ascending aorta diameter (A) ratio could be used as a noninvasive and opportunistic way to diagnose PH. In COPD patients undergoing CT scanning as routine work-up for lung transplantation, a high negative probability is desired, possibly preventing an invasive RHC. On the other hand, in COPD patients undergoing CT scanning because of any other reason, a high positive predictive value is needed to select those in need of RHC to establish a diagnosis of PH.

Previous studies suggest that PA:A is associated with PH [20–23]. However, there are only few who looked in the diagnostic value of the PA:A on CT in patients with end-stage COPD [24].

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine whether the PA:A and PA diameter can be used to diagnose PH in patients with end-stage COPD.

Methods

Patient Selection

In this diagnostic accuracy study, we included consecutive patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD or severe emphysema due to α-1-antitrypsin deficiency who were screened for eligibility for potential lung transplantation between 2004 and 2014 at the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMCU). Those with a time interval between the pre transplant chest CT scans and RHC of more than 6 months were excluded. Only patients who underwent both CT scanning and RHC in the UMCU were included, so those with external RCH and/or CT were excluded, resulting in 92 eligible patients of 154 screened in total at the UMCU. Informed consent for this retrospective study was waived by the local institutional review board (IRB), protocol number 14-568/C.

Right Heart Catheterization

The RHC data collected included mean pulmonary arterial pressure (meanPAP), systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (systPAP), and diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure (diastPAP), and in addition, cardiac output (CO), cardiac index (CI), and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) were evaluated. PH was defined as a meanPAP of 25 mmHg or more [18].

Clinical Parameters and Pulmonary Function

The following clinical parameters were obtained: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), forced expiratory volume in the first second of exhalation (FEV1) [l], predicted values of FEV1 %, predicted values of total lung capacity (TLC) %, predicted values of residual volume (RV) %, packyears smoked, partial oxygen pressure in the blood (Pa02), and outcome from the 6-min walk test (6MWT). COPD was defined by post-bronchodilator spirometry if the FEV1/FVC ratio was below 70 %. The median interquartile range (IQR) number of days between the RHC and CT scan was 42 (8–69).

CT Protocol and Measurements

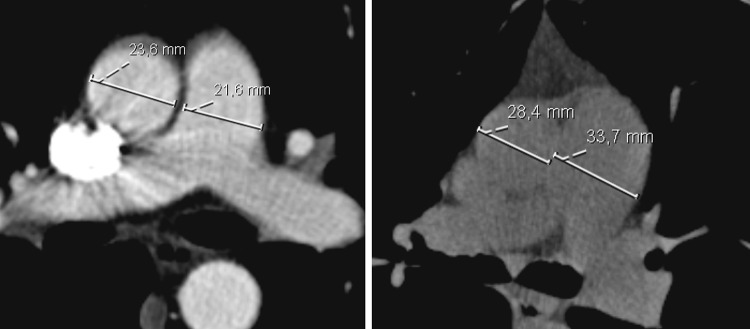

CT scans were acquired using 16-256 multi-detector row scanners (Philips Medical System), either with or without intravenous contrast. Resolution was below 1 mm. One reviewer (medical student) blinded to all clinical information including the outcome of the RHC analyzed all the CT scans. The PA:A was measured at the level bifurcation of the main PA and within the same slice, the diameter of the ascending aorta was measured (see Fig. 1). The left and right pulmonary arteries were measured directly after the bifurcation. The second blinded reviewer (senior radiology resident) measured the diameters in 25 randomly selected patients in order to assess the interobserver agreement. The intraclass coefficient was excellent 0.85 (CI 95 % 0.69–0.93).

Fig. 1.

Examples of measurements of the aorta and the pulmonary artery

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed with mean and standard deviation for normally distributed variables; if the data were not normally distributed, median and IQR were presented.

Unpaired t test and Mann–Whitney test were used for continuous variables (normally distributed and not normally distributed data, respectively). For nominal variables, the Chi-squared test was used.

Diagnostic properties to diagnose PH were studied by calculating negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV); sensitivity and specificity were calculated for PA:A, PA diameter, and both the left and right PA diameter. Logistic regression analysis was performed with PH as outcome and PA:A and PA diameter as predictive factors.

Results

In total, 92 patients were identified with complete datasets without missing CT scans, RHC data, and data within a time frame of 6 months. Baseline characteristics for the total population and split by the presence of PH are displayed in Table 1. Median (IQR) age of the total group was 55.1 (52–59) years and 61 females were included (66.3 %). Mean (SD) FEV1 was 0.65 (0.47–0.69) l and the predicted median (IQR) FEV1 was 23.1 % (17.0–25.0). Mean (SD) meanPAP was 22.7 (6.6) mmHg, median (IQR) systPAP was 33.6 (28.0–38.8) mmHg, and mean (SD) diastPAP was 15.9 (5.5) mmHg.

Table 1.

Characteristics for the total population and stratified by absence or presence of pulmonary hypertension (PH)

| No PH n = 62 |

PH n = 30 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (IQR) (years) | 54.7 year (52–59) | 55.9 year (52,75–60) | 0.953 |

| Sex (female) | 64.5 % female | 70.0 % female | 0.602 |

| BMI (SD) (kg/m2) | 23.3 (3.0) | 23.4 (2.7) | 0.795 |

| Packyears (SD) | 31.1 (11.7) | 25.8 (10.8) | 0.043 |

| FEV1 (IQR) (l) | 0.67 (0.5–0.69) | 0.62 L (0.39–0.61) | 0.178 |

| Predicted FEV1 % (IQR) | 23.0 % (27.6–24.6) | 23.3 % (15.8–26.5) | 0.967 |

| TLC % pred. (SD) | 137.2 (20.8) | 139.9 (22.3) | 0.577 |

| RV % pred. | 257.8 (63.2) | 274.2 (73.0) | 0.286 |

| 6MWT (SD) (m) | 263.3 (106.3) | 229.9 (106.9) | 0.058 |

| Change sat (%) during 6 MWT (SD) | 10.0 (5.9) | 13.3 (7.1) | 0.020 |

| PaC02 | 44.8 (7.6) | 50.5 (8.3) | 0.002 |

| Pa02 | 62.1 (14.3) | 56.0 (8.9) | 0.033 |

| Syst PAP (mmHg) | 31.1 (27–35) | 39.1 () | <0.001 |

| Diast PAP (SD) (mm Hg) | 13.0 (3.8) | 21.7 (3.3) | 0.102 |

| meanPAP | 19.1 (3.6 | 30.1(5.1) | <0.001 |

| CO (L/min) | 5.3 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.9) | 0.075 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 3.6 (1.2) | 4.2 (1.5) | 0.070 |

| PCWP (mmHg) | 9.9 (3.5) | 13.6 (5.5) | <0.001 |

| Aorta (SD) (mm) | 30.1 (3.8) | 30.8 (3.0) | 0.015 |

| Pulmonary artery (SD) (mm) | 25.8 (3.2) | 29.5 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| PA:A (SD) | 0.86 (0.12) | 0.97 (0.16) | <0.001 |

| Left pulmonary (SD) artery (mm) | 20.0 (2.6) | 21.7 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Right pulmonary (SD) artery (mm) | 20.0 (2.7) | 20.9 (2.7) | 0.24 |

Bold values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

IQR Interquartile range, BMI body mass index, TLC total lung capacity, RV residual volume, 6MWT 6-min walk test, PaCO2 partial carbon monoxide pressure in the blood, PaO2 partial oxygen pressure in the blood, meanPAP mean pulmonary arterial pressure, systPAP systolic pulmonary arterial pressure, diastPAP diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure, CO cardiac output, CI cardiac index, PCWP pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, PA:A pulmonary artery to aorta ratio

A third of patients (n = 30; 32.6 %) had PH (meanPAP ≥ 25 mmHg), of which 2 (2.2 %) suffered from severe PH (meanPAP > 40 mmHg). There were no significant differences in age, sex, FEV1, the outcome of the 6MWT, and BMI between patients with and without PH, see Table 1.

Of all included subjects, seven patients had alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. There was no significant difference in meanPAP between patients with and without alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, 23.7 (11.4) and 22.6 (6.2) mmHg, respectively. Of patients with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, 28.6 % (n = 2) had PH compared to 32.9 % (n = 28) of patients without alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency (p = 0.588).

Table 2 shows the diameters of the PA, aorta, and the PA:A by the presence of PH. There was a significant difference in PA diameter in subjects with and without PH, 29.5 (4.5) mm and 25.8 (3.2) mm, respectively (p < 0.001). Also the PA:A was significantly higher in patients with PH, see Table 1.

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for different cut-off values of pulmonary artery to aorta ratio (PA:A) in identifying pulmonary hypertension

| PA:A | ≥0.90 | ≥0.95 | ≥1 | ≥1.05 | ≥1.10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 44 | n = 34 | n = 24 | n = 12 | n = 8 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| Specificity | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| PPV | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.63 |

| NPV | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.70 |

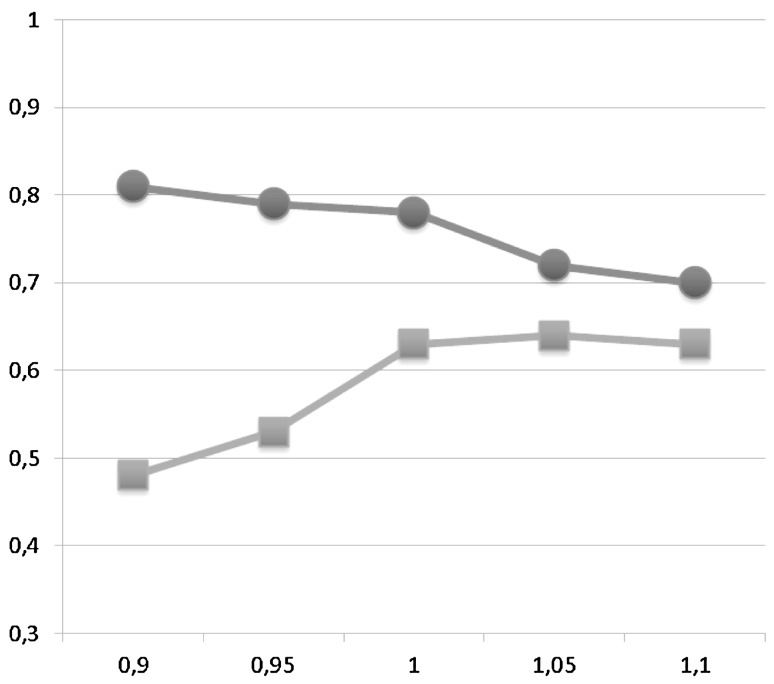

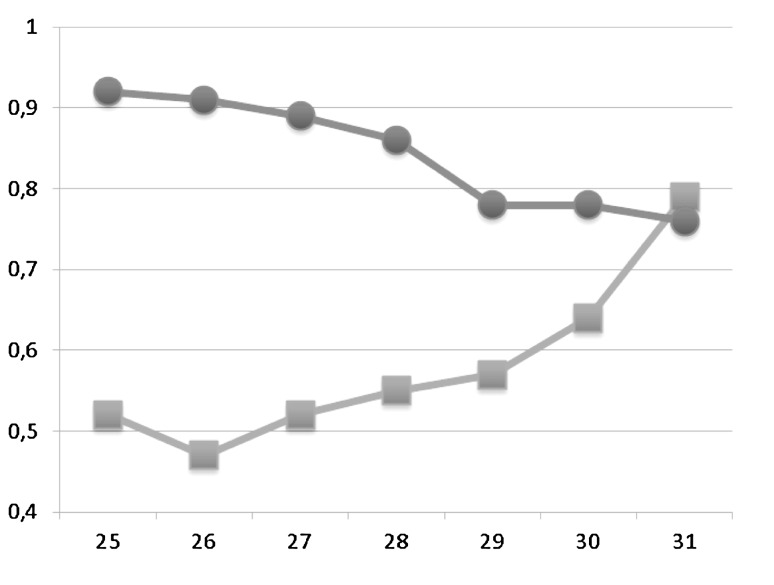

Sensitivity, specificity and negative and positive predictive values for different cut-offs of PA:A and PA diameter are displayed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. PPV and NPV are plotted in Figs. 2 and 3 for PAA and PA diameter, respectively. The NPV of a PA:A > 1 was 77.9 % and the PPV was 63.1 %. The sensitivity and specificity were 50.0 and 85.5 %. A PA diameter of >30 mm had a NPV of 78 % and PPV of 57 %. Sensitivity was 47 % and specificity 87 %.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity for different cut-offs of pulmonary artery (PA) diameter in identifying pulmonary hypertension

| PA diameter (mm) | ≥25 | ≥26 | ≥27 | ≥28 | ≥29 | ≥30 | ≥31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 64 | n = 57 | n = 48 | n = 42 | n = 28 | n = 22 | n = 14 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.37 |

| Specificity | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.95 |

| PPV | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.79 |

| NPV | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.76 |

Fig. 2.

Plot of positive and negative predictive values of different cut-offs for pulmonary artery to aorta ratio (PA:A). The X-axis shows the PA:A and the Y-axis the responding positive and negative predictive value. The red line with dot represents the negative predictive value and the blue line with squares the positive predictive value

Fig. 3.

Plot of positive and negative predictive value of different cut-offs for pulmonary artery diameters. The X-axis shows the pulmonary artery diameter in millimeters and the Y-axis the responding positive and negative predictive value. The red line with dot represents the negative predictive value and the blue line with squares the positive predictive value

Logistic regression analysis showed that per 1 additional mm of PA diameter, the OR (CI 95 %) was 1.31 (1.13–1.51). A PA diameter ≥30 had an OR (CI 95 %) of 5.91 (2. 01–16.58). A PA:A of more than 1 resulted in an OR (CI 95 %) of 5.60 (2.00–15.63).

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated that PA:A and PA diameter measured on chest CT contain substantial diagnostic accuracy for meanPAP at RHC. An increased PA:A and PA diameter on CT may be used as an indicator to raise the clinicians attention for the presence of PH (OR 5), probability of PH > 60 % for PA > 30 mm, and PA:A > 1. A PA diameter <30 mm makes PH unlikely (<78 %); however, CT cannot reliably exclude PH. Therefore, patients with end-stage COPD will still need to undergo RHC if PH needs to be excluded before transplantation.

PH is common in patients with end-stage COPD as found in our study with a prevalence rate of 31.5 %, which is in agreement with percentages found in previous studies and reports reporting a percentage of around 36 % [4]. The relationship of PA:A and PH is of clinical importance as PH is related with an increased mortality and increased exacerbation rate. In earlier stages of COPD, adequate treatment may influence the process of vascular remodeling and improve survival rate and quality of life [25, 26]. Another aspect is the higher complication risk of lung transplant surgery in patients with PH and increased post-transplant mortality [13, 27]. An increased PA:A or large PA diameter on CT may raise the clinicians’ awareness on the possibility that PH is present.

Prior studies have also shown a relationship between PA:A ratio > 1 and PH in COPD, but most data are derived from studies with a heterogeneous group of patients with different types of lung disease [20–23]. Because the pulmonary diameter can differ depending on the underlying lung disease, studies specifically aimed on end-stage COPD are needed. Our study included a well-defined cohort of patients with end-stage COPD. In addition, the hemodynamics and the pathophysiological relationship between COPD and PH may differ for instance from that of PH in sarcoidosis or interstitial pulmonary fibrosis [28].

The findings in the current study are consistent with studies by others. Iyer et al. performed a retrospective study on 60 patients with COPD, and the sensitivity and specificity for a PA:A > 1 were 73 and 84 % for identifying PH [24]. Although, the specificity numbers were similar to our study, sensitivity numbers were higher (in our study the sensitivity was 50 %). This difference could not be explained by a difference in study population. Shin et al. also retrospectively studied a cohort of 65 COPD patients and showed a sensitivity and specificity of a PA:A > 1 of respectively 50 and 93 %, which is similar to our study [20]. A strong point of our study compared to that of Shin is that we used RHC to diagnose PH instead of using the PA:A > 1 or <1.

A PA:A of more than 1 or PA diameter of ≥30 is associated with the presence of PH in our study and it may be of use to increase the suspicion of PH before RHC is performed. One of the most important advantages of using CT scanning is that it is a noninvasive method and that it is readily available. From our study, it is shown that no other clinical parameters differed between the patients with and without PH. Especially because the symptoms of PH show a great overlap with those of COPD, the PA:A may be the only parameter available to the treating physician giving information on the likelihood of PH before RHC is performed.

In addition, CT might also provide relevant information on the extent of emphysema and airway wall disease, which for instance could be of use in determining treatment effect. Ando et al. showed in a small set of COPD subjects that the automated quantification of emphysema and the extent of small pulmonary vessels is associated with a treatment effect of pulmonary vasodilators [29]. Assessing emphysema on CT might also be used to better understand the reduced aerobic exercise capacity in lung transplants candidates with COPD and PH. Data from Adir et al. suggest that lower aerobic exercise capacity is not associated with presence of PH, but with advanced emphysema [30]. Next to emphysema, CT scanning also can provide information on airway wall thickening. Airway wall thickening seems to be associated with severity of PH in patients with COPD. Results of the study by Dournes et al. showed that airway wall thickening on CT was highly associated with meanPAP even when compared to Pa02 [31]. Together, these studies indicate that CT scanning to determine extent of emphysema and airway wall disease in patients with COPD and PH may provide additional information.

Echocardiography is used frequently as noninvasive test for PH as it may estimate the pulmonary arterial pressure. However, in COPD patients, this is often not achievable because of hyperinflation of the thorax; and in only 60 % of cases, echocardiography can measure the pulmonary arterial pressure [19]. In our study, the diameters of the PA could be measured in all cases even in scans without i.v. contrast. The fact that we included both scans with and without i.v. contrast injection is a strong point, because in daily clinical practice both scans with and without contrast are made. Furthermore, these measurements show good reproducibility and require limited training.

A strong point of our study is the large sample size of 92 patients who underwent RCH, making it the largest study on PA:A and PH in end-stage COPD. Furthermore, all patients included were transplanted or were on the current waiting list, and therefore major co morbidities were excluded like coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure. Our study has some limitations. First, our population consisted only of patients with severe COPD awaiting lung transplantation. This may limit generalizability in patients with less severe COPD, but previous literature suggests that our results maybe generalizable [20]. In addition, our included patients have been selected by screening for a lung transplantation waiting list and comorbidities such as left heart disease were exclusion criteria, which may be associated with the occurrence of PH [5, 32]. Second, a limitation remains the single cohort design and retrospective nature of the study. Future studies in other cohorts should be performed to cross-validate our findings.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the PA:A and the PA diameter as measured on chest CT can be used to make the presence of PH very likely, but they cannot be used to reliably exclude PH in COPD patients that are screened for lung transplantation. Patients with a PA diameter > 30 mm or > PA:A > 1 have a high odds ratio of having PH. However, RHC will still remain the gold standard for diagnosing PH.

Acknowledgments

No funding was received for this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Burden of COPD, a WHO article. http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/. Accessed 1 Oct 2015

- 2.Kiely DG, Elliot CA, Sabroe I, Condliffe R. Pulmonary hypertension: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2013;346:f2028. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandel J, Poch D. In the clinic. Pulmonary hypertension. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(9):1–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-9-201305070-01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaouat A, Naeije R, Weitzenblum E. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1371–1385. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wrobel JP, Thompson BR, Williams TJ. Mechanisms of pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pathophysiologic review. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2012;31:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adir Y, Shachner R, Amir O, Humbert M. Severe pulmonary hypertension associated with emphysema: a new phenotype? Chest. 2012;142(6):1654–1658. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler R, Faller M, Fourgaut G, Mennecier B, Weitzenblum E. Predictive factors of hospitalization for acute exacerbation in a series of 64 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:158–164. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuttica MJ, Kalhan R, Shlobin OA, Ahmad S, Gladwin M, Machado RF, Barnett SD, Nathan SD. Categorization and impact of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced COPD. Respir Med. 2010;104(12):1877e82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells JM, Washko GR, Han MK, Abbas N, Nath H, Mamary AJ, Regan E, Bailey WC, Martinez FJ, Westfall E, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Curtis JL, Hokanson JE, Lynch DA, Make BJ, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, Bowler RP, Dransfield MT, COPDGene Investigators. ECLIPSE Study Investigators Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(10):913–921. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrington M, Murphy NF, Strange G, Peacock A, McMurray JJ, Stewart S. Prognostic impact of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a population-based analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;124:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin S, King CS, Brown AW, Albano MC, Atkins M, Sheridan MJ, Ahmad S, Newton KM, Weir N, Shlobin OA, Nathan SD. Pulmonary artery size as a predictor of pulmonary hypertension and outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2014;108(11):1626–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaïci A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Cottin V, Degano B, Jaïs X, Montani D, Souza R, Simonneau G. Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Circulation. 2010;122:156–163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh VK, George PM, Gries C. Pulmonary hypertension is associated with increased post-lung transplant mortality risk in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2015;34(3):424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling Y, Johnson MK, Kiely DG, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, Gibbs JS, Howard LS, Pepke-Zaba J, Sheares KK, Corris PA, Fisher AJ, Lordan JL, Gaine S, Coghlan JG, Wort SJ, Gatzoulis MA, Peacock AJ. Changing demographics, epidemiology, and survival of incident pulmonary arterial hypertension: results from the pulmonary hypertension registry of the United Kingdom and Ireland. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:790–796. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0383OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badesch DB, Raskob GE, Elliott CG, Krichman AM, Farber HW, Frost AE, Barst RJ, Benza RL, Liou TG, Turner M, Giles S, Feldkircher K, Miller DP, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: baseline characteristics from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2010;137:376–387. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simonneau G, Galiè N, Jansa P, Meyer GM, Al-Hiti H, Kusic-Pajic A, Lemarié JC, Hoeper MM, Rubin LJ. Treatment of patients with mildly symptomatic pulmonary arterial hypertension with bosentan (EARLY study): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2093–2100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60919-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, Mathier MA, McGoon MD, Park MH, Rosenson RS, Rubin LJ, Tapson VF, Varga J, American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. American Heart Association. American College of Chest Physicians. American Thoracic Society, Inc. Pulmonary hypertension Association ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(17):1573–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Ferrari VA, Sutton MS, Zisman DA, Blumenthal NP, Pochettino A, Kotloff RM. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;67(5):735–740. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1130OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janda S, Shahidi N, Gin K, Swiston J. Diagnostic accuracy of echocardiography for pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2011;97:612–622. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.212084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Y, Wan C, Tian P, Wu Y, Li X, Yang T, An J, Wang T, Chen L, Wen F. CT-based pulmonary artery measurement in the detection of pulmonary hypertension: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Med (Baltimore) 2014;93(27):e256. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng CS, Wells AU, Padley SP. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14(4):270–278. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alhamad EH, Al-Boukai AA, Al-Kassimi FA, Alfaleh HF, Alshamiri MQ, Alzeer AH, Al-Otair HA, Ibrahim GF, Shaik SA. Prediction of pulmonary hypertension in patients with or without interstitial lung disease: reliability of CT findings. Radiology. 2011;260(3):875–883. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahammedi A, Oshmyansky A, Hassoun PM, Thiemann DR, Siegelman SS. Pulmonary artery measurements in pulmonary hypertension: the role of computed tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 2013;28(2):96–103. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e318271c2eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer AS, Wells JM, Vishin S, Bhatt SP, Wille KM, Dransfield MT. CT scan-measured pulmonary artery to aorta ratio and echocardiography for detecting pulmonary hypertension in severe COPD. Chest. 2014;145(4):824–832. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girard A, Jouneau S, Chabanne C, Khouatra C, Lannes M, Traclet J, Turquier S, Delaval P, Cordier JF, Cottin V. Severe pulmonary hypertension associated with COPD: hemodynamic Improvement with specific therapy. Respiration. 2015;90(3):220–228. doi: 10.1159/000431380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald-Mammosser M, Weitzenblum E, Quoix E, Moser G, Chaouat A, Charpentier C, Kessler R. Prognostic factors in COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Importance of pulmonary artery pressure. Chest. 1995;107:1193–1198. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen KH, Iversen M, Kjaergaard J, Mortensen J, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Bendstrup E, Videbaek R, Carlsen J. Prevalence, predictors, and survival in pulmonary hypertension related to end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2012;31(4):373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan RT, Kuzo R, Goodman LR, Siegel R, Haasler GB, Presberg KW, Medical College of Wisconsin Lung Transplant Group Utility of CT scan evaluation for predicting pulmonary hypertension in patients with parenchymal lung disease. Chest. 1998;113(5):1250–1256. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ando K, Kuraishi H, Nagaoka T, Tsutsumi T, Hoshika Y, Kimura T, Ienaga H, Morio Y, Takahashi K. Potential role of CT metrics in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with pulmonary hypertension. Lung. 2015;193(6):911–918. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9813-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dournes G, Laurent F, Coste F, Dromer C, Blanchard E, Picard F, Baldacci F, Montaudon M, Girodet PO, Marthan R, Berger P. Computed tomographic measurement of airway remodeling and emphysema in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Correlation with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(1):63–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201408-1423OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adir Y, Ollech JE, Vainshelboim B, Shostak Y, Laor A, Kramer MR. The effect of pulmonary hypertension on aerobic exercise capacity in lung transplant candidates with advanced emphysema. Lung. 2015;193(2):223–229. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minai OA, Fessler H, Stoller JK, Criner GJ, Scharf SM, Meli Y, Nutter B, DeCamp MM, NETT Research Group Clinical characteristics and prediction of pulmonary hypertension in severe emphysema. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]