Abstract

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of regulated necrosis. It is implicated in various human diseases, including ischemic organ damage and cancer. Here, we report the crucial role of autophagy, particularly autophagic degradation of cellular iron storage proteins (a process known as ferritinophagy), in ferroptosis. Using RNAi screening coupled with subsequent genetic analysis, we identified multiple autophagy-related genes as positive regulators of ferroptosis. Ferroptosis induction led to autophagy activation and consequent degradation of ferritin and ferritinophagy cargo receptor NCOA4. Consistently, inhibition of ferritinophagy by blockage of autophagy or knockdown of NCOA4 abrogated the accumulation of ferroptosis-associated cellular labile iron and reactive oxygen species, as well as eventual ferroptotic cell death. Therefore, ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process, and NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy supports ferroptosis by controlling cellular iron homeostasis.

Keywords: ferroptosis, autophagy, ferritinophagy, iron homeostasis, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Programmed cell death is crucial for various physiological processes in multicellular organisms1,2,3. Deregulation of programmed cell death contributes to the development of multiple human diseases, such as cancer and neurodegeneration. While apoptosis is the best-studied form of programmed cell death, recent studies demonstrate that there are also programmed cell death processes that are not apoptosis4,5,6,7. For example, necroptosis and ferroptosis are two distinct regulated necrosis pathways that are under precise genetic control and may function under diverse physiological and pathological contexts8,9,10.

Ferroptosis is emerging as a new form of programmed necrosis whose execution requires the accumulation of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) in an iron-dependent manner8. Synthetic small-molecule compound erastin can trigger ferroptosis by inhibiting the activity of cystine-glutamate antiporter (system Xc−), leading to the depletion of glutathione (GSH), the major cellular antioxidant whose synthesis requires cysteine11,12. As such, ferroptosis is caused by the loss of cellular redox homeostasis. Further, it appears that lipid ROS/peroxides instead of cytosolic ROS play more crucial roles in ferroptosis, and inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), an enzyme required for the clearance of lipid ROS, can induce ferropotosis even when cellular cysteine and GSH contents are normal13. Importantly, it has been demonstrated recently that the intracellular metabolic pathway glutaminolysis also plays crucial roles in ferroptosis by promoting cellular ROS generation14,15.

Although the physiological function of ferroptosis is not defined, its role in human diseases has been established. For example, ferroptosis is involved in ischemia-induced organ injury, and inhibition of ferroptosis has been shown to be effective in treating ischemia/reperfusion-induced organ damage in multiple experimental models14,16,17. Ferroptosis has also been investigated in cancer and cancer treatment11,13. Importantly, ferroptosis contributes to the tumor suppressive function of p5318. Loss of p53 leads to transcriptional upregulation of cystine transporter SLC7A11, thus rendering cancer cells more resistant to ferroptosis.

Autophagy is a conserved intracellular catabolic process that delivers cellular components to the lysosome for degradation19. The core machinery of autophagy consists of over 30 autophagy-related genes (ATGs). Autophagy is generally a stress-responsive, survival mechanism. However, a controversial theory ever since the original observation of autophagy is that autophagy may also be a cell death mechanism (autophagic cell death)20,21. Autophagy might indeed promote cell death under specific contexts22,23, but the underlying mechanisms have been elusive.

In this study, we demonstrate that ferroptosis is a form of autophagic cell death. Mechanistically, autophagy promotes ferroptosis via a form of cargo-specific autophagy known as ferrotinophagy. Upon cystine deprivation, autophagy is activated to degrade the iron storage protein ferritin, which is mediated by the cargo receptor NCOA4. Such NCOA4-mediated autophagic degradation of ferritin (ferroptinophagy)24,25,26,27, by maintaining cellular labile iron contents, promotes the accumulation of cellular ROS and consequent ferroptotic cell death.

Results

Identification of novel players of ferroptosis by RNAi screening

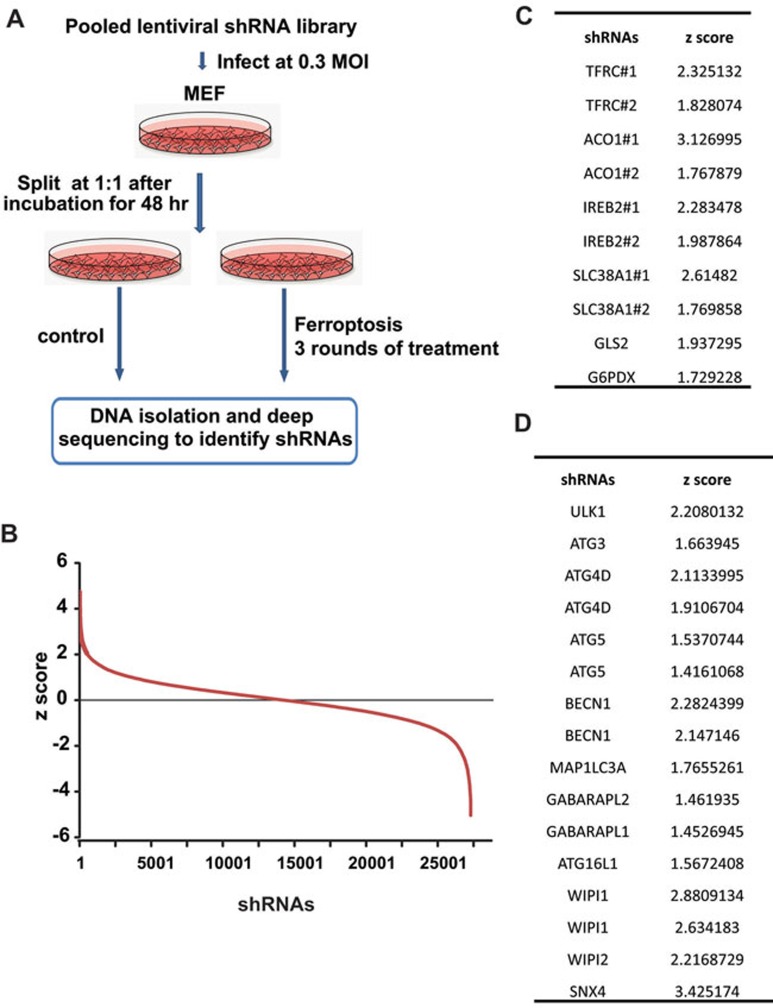

To systemically study the mechanisms of ferroptosis, we performed an RNAi screening. A pooled shRNA lentivirus library targeting 4 625 'signaling Pathway Targets' (DECIPHER shRNA Library Mouse Module 1: https://www.cellecta.com/products-services/cellecta-pooled-lentiviral-libraries/decipher-shrna-libraries/) was transduced into wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Cells were treated with normal medium or the ferroptosis-inducing medium (Figure 1A and 1B). Deep sequencing of the shRNAs integrated into genomic DNA from control cells and cells that survived ferroptosis induction was subsequently performed. Comparison of the sequencing data led to the identification of shRNAs that were enriched in cells surviving ferroptosis treatment. The gene targets of the enriched shRNAs are potential genes that positively regulate ferroptosis. Among the screen hits, many reported ferroptosis genes were identified, such as iron homeostasis regulating genes TFRC, ACO1, and IREB2; glutaminolysis regulating genes SLC38A1 and GLS2; and pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) gene G6PDX12,14 (Figure 1C). These positive outcomes validated our screen approach. Further, our screen also identified many genes not previously implicated in the regulation of ferrotpsis. Remarkably, 11 ATG genes were among this list of potential positive regulators of ferroptosis (the shRNA library used for this screen contains shRNAs targeting 22 ATG genes; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Genetic screen identifies regulators of ferroptosis. (A) RNAi screening strategy to identify novel players of ferroptosis. (B) Plot of z-score (frequency of a specific shRNA in total sequencing reads calculated from ferroptosis-treated cells over the frequency calculated from control cells) of the RNAi screen results shows the enrichment of individual shRNAs. (C) Multiple known ferroptosis regulators were enriched in our RNAi screening. (D) Multiple autophagy-related genes were enriched in our RNAi screening.

Autophagy is a positive regulator of ferroptosis

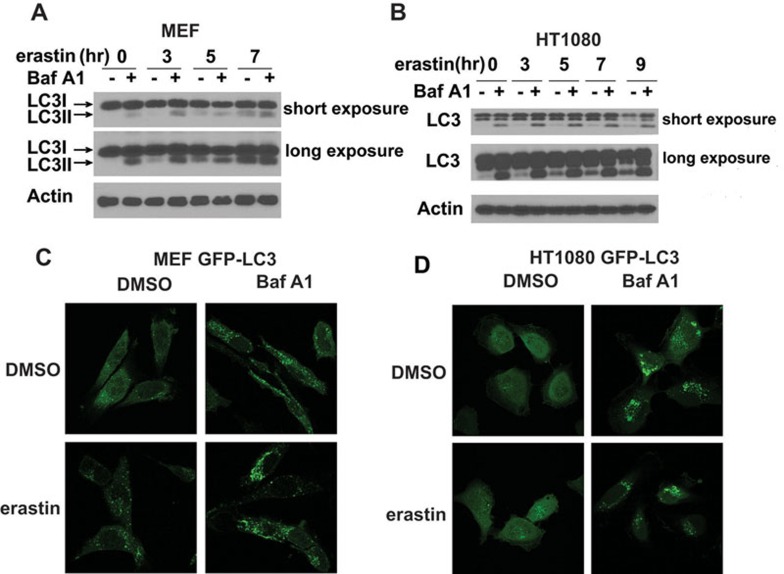

To examine the relationship between autophagy and ferroptosis, we first tested whether ferroptosis-inducing conditions can stimulate autophagy. Treatment of MEFs and human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells with ferroptosis inducer erastin induced a conversion of LC3I to LC3II and GFP-LC3 puncta formation, the hallmarks of autophagy response (Figure 2A-2D). Lysosomal inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) can further enhance LC3II accumulation and LC3-GFP puncta formation, indicating a functionally intact flux of autophagy.

Figure 2.

Ferroptosis inducer activates autophagy. (A, B) Erastin induced LC3 conversion in MEFs (A) and HT1080 cells (B). Cells seeded in six-well dishes were treated with the 0.5 μM (A) or 5 μM (B) erastin for the indicated times. 20 nM BafA1 was added 2 h before cell harvest. Cell extracts were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against the indicated proteins. The accumulation of LC3II (faster migrating form) relative to LC3I (slower migrating form) is indicative of the induction of autophagy. (C, D) Erastin induced GFP-LC3 puncta formation in MEFs (C) and HT1080 cells (D). Cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 grown on glass cover slips were either left untreated or treated with 0.5 μM (C) or 5 μM (D) erastin for 7 h. Cells were then fixed with 3.7% PFA, processed for imaging, and visualized under the confocal microscope using the 60× magnification objective.

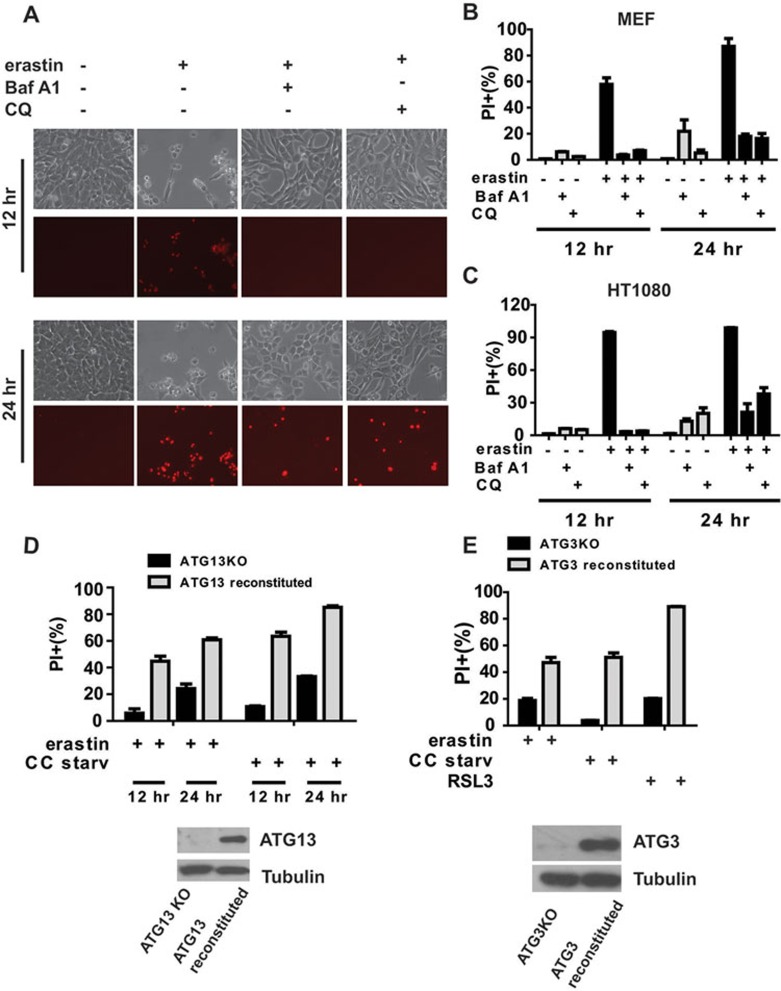

Is autophagy a driving force for ferroptotic cell death, as suggested by our RNAi screening? This is an important question since autophagy is usually an anti-death, survival mechanism. To address this question, we examined the effect of pharmacological inhibitors of autophagy on ferroptosis. Indeed, lysosomal inhibitors BafA1 and chloroquine (CQ) can significantly block erastin-induced ferrroptosis in both MEFs and HT1080 cells, as measured by propidium iodide (PI) staining coupled with flow cytometry (Figure 3A-3C). Similarly, BafA1 can also inhibit cystine starvation-induced ferroptosis in MEFs and HT1080 cells (Supplementary information, Figure S1). Ferroptosis was previously suggested to be independent of autophagy12, which appears to be in conflict with our finding. This promoted us to carefully compare our results with the previous report. In the previous study, cell death was measured at a relatively late time point (24 h). Therefore, we measured ferroptosis in two different cell types (MEFs and HT1080 cells) by using various erastin concentrations and at different time points (Supplementary information, Figure S2). BafA1 and CQ blocked ferroptosis at earlier time points, but the inhibitory effect was gradually lost at later time points, especially when higher dose of erastin was used. Taken together, inhibition of lysosomal function, the end point of autophagy flux, can significantly attenuate and delay the process of ferroptosis.

Figure 3.

Autophagy positively regulates ferroptosis. (A-C) Autophagy inhibitors BafA1 and CQ inhibit ferroptosis in MEFs (A, B) and HT1080 cells (C). Cells were treated as indicated. In A, the effect of autophagy inhibitors was shown by microscopy (black and white: phase contract; red: PI staining) with inhibitors and time (h) of treatment as indicated. In B and C, cell death was quantified by PI staining coupled with flow cytometry. erastin: 1 μM; BafA1: 20 nM; CQ: 50 μM. The data show means ± SEM from 3 independent experiments (same for all quantitative results thereafter). (D) ATG13 is required for ferroptosis. ATG13KO MEFs, or ATG13KO cells reconstituted with ectopic ATG13 expression, were treated as indicated. Cell death was determined by PI staining coupled with flow cytometry. Western blot confirmed the expression of ATG13. erastin: 1 μM. (E) ATG3 is required for ferroptosis. ATG3KO MEFs, or ATG3KO cells reconstituted with ectopic ATG3 expression, were treated as indicated for 12 h. Cell death was determined by PI staining coupled with flow cytometry. ATG3 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting. erastin: 1 μM; RSL3: 1 μM.

To further confirm the role of autophagy in ferroptosis, we tested the requirement of ATG genes for ferroptosis. Knockout of ATG13 and ATG3, two key players of autophagy that function at different stages of the autophagy pathway28, greatly reduced the sensitivity of MEFs to ferropotosis induced by erastin or cystine starvation, and reconstituting ATG13 and ATG3 back to these cells restored the ferroptosis sensitivity (Figure 3D and 3E). Consistently, knockout of other autophagy genes, such as ULK1/2 and ATG5, and pharmacological inhibition of PI3 kinase all led to significantly lower levels of erastin-induced ferroptosis in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Supplementary information, Figure S3). All these results demonstrate that canonical autophagy machinery plays a crucial role in ferroptosis. Importantly, both genetic (Figure 3E) and pharmacological (Supplementary information, Figure S4) inhibition of autophagy also prevented ferroptosis induced by a small-molecule inhibitor of GPX4, RSL3. Because GPX4 prevents ferroptosis through clearance of lipid peroxides, it is most likely that autophagy is essential for ferroptosis-associated generation of ROS and lipid peroxides. As such, autophagy blockage can prevent cells from building up a lethal amount of lipid peroxides, a prerequisite for ferroptosis, even when GPX4 is inhibited by RSL3.

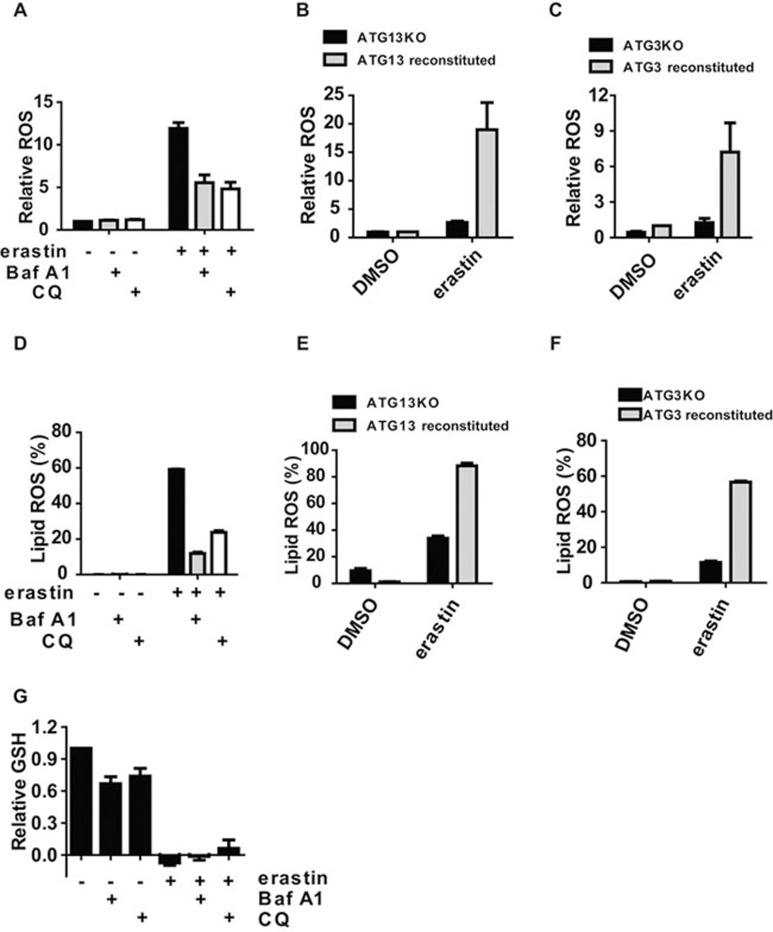

Autophagy is required for ferroptosis-associated ROS accumulation

ROS accumulation is one of hallmarks of ferroptosis. Consistently, ferroptosis inhibitors (such as ferrostatin) and various antioxidants or ROS scavengers can all completely inhibit cellular ROS accumulation and ferroptotic cell death12,14. As autophagy is required for ferroptosis induced by both erastin and RSL3, we tested whether autophagy is required for ferroptosis-associated ROS production, especially lipid ROS accumulation. Indeed, BafA1 and CQ significantly inhibited ferroptosis-associated total ROS accumulation (Figure 4A). Similarly, total ROS level was significantly lower in autophagy-deficient cells (ATG13-knockout (ATG13KO) and ATG3-knockout (ATG3KO)) compared to autophagy-rescued cells (Figure 4B and 4C). Importantly, both pharmacological and genetic inhibition of autophagy significantly inhibited ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS accumulation (Figure 4D-4F).

Figure 4.

Autophagy is required for ferroptosis-associated ROS accumulation. (A) Autophagy inhibitors Baf1A and CQ can inhibit ferroptosis-associated ROS accumulation. MEFs were treated as indicated for 8 h. ROS was measured by H2DCFDA staining coupled with flow cytometry. BafA1: 20 nM; CQ: 50 μM. (B) ATG13 knockout inhibited ferroptosis-associated ROS accumulation. ATG13KO MEFs, or ATG13KO cells reconstituted with ectopic ATG13 expression, were treated with 1 μM erastin for 8 h. ROS was measured by H2DCFDA staining coupled with flow cytometry. (C) ATG3 is required for ferroptosis-induced ROS accumulation. ATG3KO MEFs, or ATG3KO cells reconstituted with ectopic ATG3 expression, were treated with 1 μM erastin for 8 h. ROS was measured by H2DCFDA staining coupled with flow cytometry. (D) Autophagy inhibitors BafA1 and CQ inhibit ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS generation. MEFs were treated as indicated for 8 h. Lipid ROS was measured by C11-BODIPY staining coupled with flow cytometry. erastin: 1 μM; BafA1: 20 nM; CQ: 50 μM. (E, F) ATG13 and ATG3 are required for ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS accumulation. The experiments were performed as B and C, except that lipid ROS (not total ROS) was measured by C11-BODIPY staining coupled with flow cytometry. (G) Autophagy is not required for erastin-induced GSH depletion. MEFs were treated as indicated for 8 h. Total GSH was measured with or without pharmacological inhibition of autophagy. BafA1: 20 nM; CQ: 50 μM.

It should be noted that although inhibition of autophagy attenuated erastin-induced cellular ROS accumulation, it failed to prevent GSH depletion induced by erastin (Figure 4G). This result is not unexpected: erastin prevents the import of cytine and thus depletes one of the building blocks for GSH synthesis; under this condition, GSH depletion will not be prevented by autophagy inhibition or any other downstream intervention.

Autophagy regulates cellular iron homeostasis

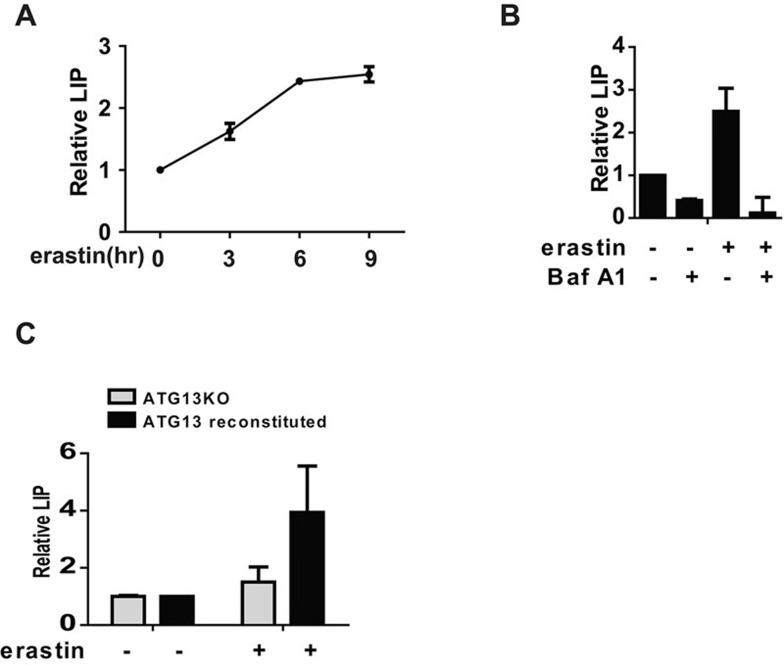

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent programmed necrosis, and cellular iron is required for ROS accumulation upon ferroptosis12. Therefore, does autophagy promote cellular ROS accumulation upon ferroptosis by increasing free iron levels in cells? To test this possibility, we first measured the cellular labile iron pool (LIP). Erastin treatment led to a time-dependent increase of the cellular LIP (Figure 5A). Subsequently, we tested whether inhibition of autophagy can block erastin-induced LIP increase. Indeed, BafA1 can block ferroptosis-associated LIP increase (Figure 5B). LIP accumulation was also significantly lower in autophagy-deficient cells compared to autophagy-reconstituted cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Autophagy is required for ferroptosis-associated labile iron accumulation. (A) Erastin treatment caused an increase of cellular LIP. MEFs were treated with erastin (1 μM) for the indicated times. Cells were stained with calcein-acetoxymethyl ester and LIP was subsequently quantitated by flow cytometry. (B) Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy prevents ferroptosis-associated LIP accumulation. MEFs were treated with or without BafA1 as indicated for 6 h. Cells were stained with calcein-acetoxymethyl ester, and LIP was subsequently quantitated by flow cytometry. BafA1: 20 nM. (C) Genetic disruption of autophagy prevents ferroptosis-associated LIP accumulation. ATG13KO MEFs, or ATG13KO MEFs reconstituted with ectopic ATG13 expression, were treated with 1 μM erastin as indicated for 6 h. Cells were stained with calcein-acetoxymethyl ester and LIP was subsequently quantitated by flow cytometry.

Autophagy regulates ferroptosis via ferritinophagy

The increase of LIP could be due to either increase of iron uptake from the medium or degradation of cellular iron storage protein ferritin. Transferrin-mediated iron transport is the most important iron uptake pathway29, and transferrin is required for ferroptosis14,15. However, erastin did not change the rate of transferrin internalization (Supplementary information, Figure S5).

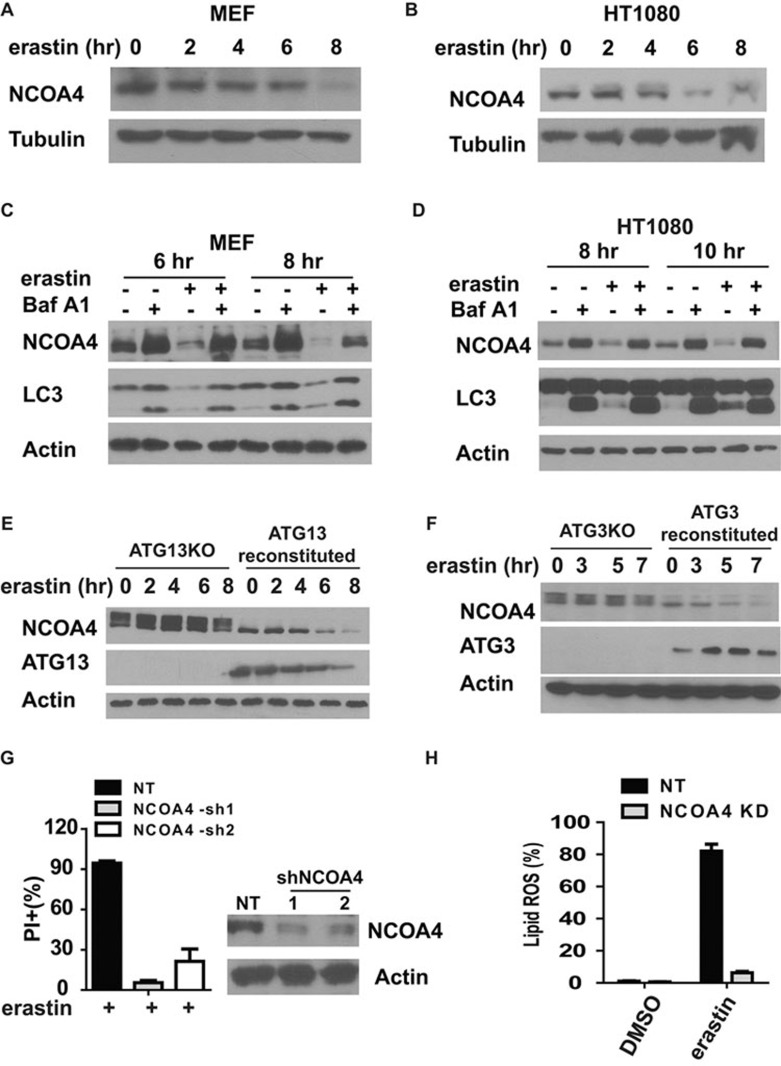

It has been reported that cellular iron homeostasis can be regulated by a specific, NCOA4-mediated autophagy pathway called ferritinophagy24,25,26,27. Using NCOA4 as the cargo receptor, ferritinophagy recognizes ferritin and delivers it for lysosomal degradation, leading to the release of free iron and thus an increase of LIP24,25,26,27. We found that upon erastin treatment, NCOA4 level was decreased in a time-dependent manner in both MEFs and HT1080 cells (Figure 6A and 6B). The decrease of NCOA4 is through autophagy because such NCOA4 degradation was ablated by both pharmacological and genetic inhibition of autophagy (Figure 6C-6F). Consistent with the model that ferritinophagy plays a crucial role in ferroptosis, elimination of NCOA4 expression by RNAi knockdown significantly block ferroptosis (Figure 6G) and ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS accumulation (Figure 6H).

Figure 6.

NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy promotes ferroptosis. (A, B) Ferroptosis induced NCOA4 degradation in a time-dependent manner in MEFs (A) and HT1080 cells (B). MEFs or HT1080 cells were treated as indicated. Total cell extract was used for western blot to detect NCOA4 change during ferroptosis. erastin: 0.5 μM (A) or 5 μM (B). (C, D) Autophagy inhibitor BafA1 can block ferroptosis-induced NCOA4 degradation in MEFs (C) and HT1080 cells (D). MEFs or HT1080 cells were treated as indicated. Total cell extract was used for western blot to detect NCOA4 change during ferroptosis. erastin: 0.5 μM (C) or 5 μM (D). BafA1: 20 nM. (E, F) Genetic disruption of autophagy blocks ferroptosis-induced NCOA4 degradation. ATG13KO and ATG13-reconstituted MEFs (E), or ATG3KO and ATG3-reconstituted MEFs (F), were treated with 1 μM erastin for the indicated times. Total cell lysate was used for western blot to detect NCOA4 change during ferroptosis. (G) Knockdown of NCOA4 by shRNAs can block ferroptosis. MEFs infected with non-target (NT) shRNA or two independent NCOA4 shRNAs were treated with 0.5 μM erastin for 12 h. Cell death was measured by PI staining coupled with flow cytometry. (H) Knockdown of NCOA4 by shRNA in MEFs can block ferroptosis-associated lipid ROS accumulation. NCOA4-knockdown or control knockdown cells were treated with 1 μM erastin for 10 h. Lipid ROS was measured by C11-BODIPY staining coupled with flow cytometry.

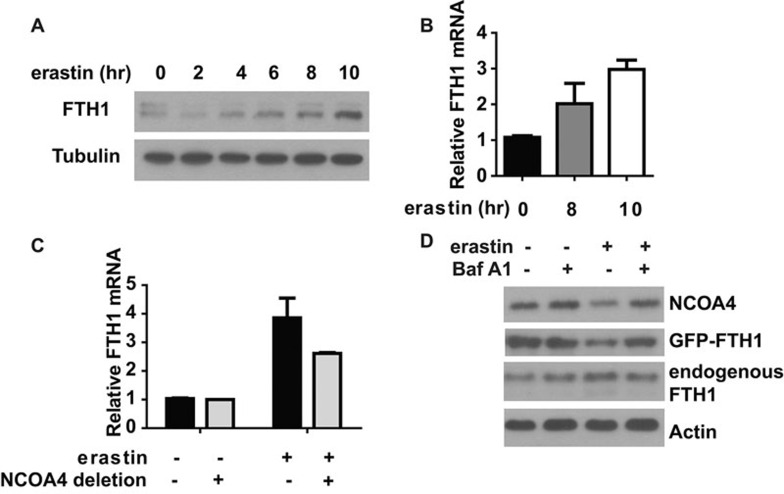

Given that both autophagy and NCOA4 are involved in ferroptosis, we tested whether ferritin light chain 1 (FTH1), a substrate of ferritinophagy, is also degraded by autophagy. Surprisingly, we observed an increase of endogenous FTH1 level during ferroptosis (Figure 7A). Since increase of cellular iron level will induce the expression of endogenous FTH129, it is likely that LIP accumulation during ferroptosis will induce transcriptional upregulation of endogenous FTH1. Indeed, q-PCR analysis confirmed the upregulation of endogenous FTH1 mRNA level (Figure 7B) and this upregulation is NCOA4 dependent (Figure 7C). To test whether there was a simultaneous degradation of FTH1 protein upon ferroptosis induction, we monitored the level of ectopically expressed GFP-FTH1. As shown in Figure 7D, erastin induced the degradation of GFP-FTH1, which could be prevented by autophagy inhibitor BafA1.

Figure 7.

Regulation of FTH1 expression during ferroptosis. (A) Ferroptosis induced an increase of FTH1 protein levels. HT1080 cells were treated with 5 μM erastin for the indicated times. Total cell lysate was used to detect FTH1 expression. (B) Ferroptosis induced an upreguation of FTH1 mRNA levels. HT1080 cells were treated with 5 μM erastin as indicated. Total RNA was isolated and mRNA level of FTH1 was measured by q-PCR. (C) NCOA4 is required for ferroptosis-induced FTH1 mRNA upregulatioin. HT1080 cells with or without NCOA4 depletion were treated with 5 μM erastin for 10 h. Total RNA was isolated and mRNA level of FTH1 was measured by q-PCR. (D) BafA1 inhibits ferroptosis-associated FTH1 degradation. HT1080 cells were treated as indicated. Total cell lysate was used for immunoblotting to detect the changes of target protein levels.

Discussion

Collectively, in this study we demonstrate that autophagy plays an important role in the regulation of ferroptosis by regulating cellular iron homeostasis and cellular ROS generation. Upon induction of ferroptosis, autophagy is activated, leading to degradation of cellular iron stock protein ferritin and thus an increase of cellular labile iron level via NCOA4-mediated autophagy pathway, ferritinophagy. High levels of cellular labile iron ensure rapid accumulation of cellular ROS, which is essential for ferroptosis.

It should be emphasized that the effect of autophagy inhibition on ferroptosis is more obvious at the early phase of ferroptosis and when the induction is modest, and such effect is plateaued at later time points and when the induction is more dramatic (see Figure 3 and Supplementary information, Figure S3). This can explain why such a crucial effect of autophagy evaded the earliest ferroptosis study12, and why only a modest effect of autophagy was observed in a recent study30; both studies utilized relatively high doses of erastin and late time points for ferroptosis measurement.

The role of autophagy in cell death and cell survival has been controversial. It is well accepted that under most biological conditions autophagy functions as a pro-survival mechanism31. Autophagy can be activated when cells encounter stresses such as nutrient starvation, hypoxia, as well as a wide range of anticancer therapies. For this reason, combination of autophagy inhibition and other cancer treatments might be an effective anticancer therapeutic approach19. On the other hand, autophagy may also be a cell death mechanism under certain specific contexts ― the so-called 'autophagic cell death', via less defined mechanisms20,32. Here, we present compelling evidence to support that ferroptosis is a form of autophagic cell death, as ferroptosis satisfies the two major criteria of autophagic cell death, that the death process is associated with autophagy activation and that autophagy plays a pro-death role in the cell death process. While autophagy activation appears to be modest as measured by LC3 conjugation, it is highly likely that the cargo-specific autophagy, ferritinophagy, is preferentially activated. Our finding that autophagy is crucial for ferroptosis is relevant to cancer treatment and raises concerns about combination therapy strategies involving autophagy inhibition. For example, sorafenib, a FDA-approved drug for the treatment of primary kidney cancer, advanced primary liver cancer and radioactive iodine-resistant advanced thyroid carcinoma, has been reported to induce ferroptotic cell death33. If ferroptosis indeed contributes to the therapeutic effect of sorafenib, then autophagy inhibition should not be combined with sorafenib for cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Primary antibodies used were anti-LC3 (Sigma, Cat# L7543), anti-γ-tubulin (Sigma, Cat# T6557), anti-NCOA4 (Bethyl Labs, Cat# A302-272A), anti-FTH1 (Cell Signaling, Cat# 4393S), anti-ATG13 (Sigma, Cat# SAB4200100), anti-ATG3 (Cell Signaling, Cat# 3415S), anti-actin (Sigma, Cat# A5316), erastin (Sigma, Cat# E7781), Bafilomycin A1 (Sigma, Cat# B1793), Chloroquine (Sigma, Cat# C6628), RSL3 (Selleckchem, Cat# S8155), wortmannin (Cell Signaling, Cat# 9951).

Cell culture

Unless specified otherwise, all mammalian cells are maintained in DMEM with high glucose, sodium pyruvate (1 mM), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (U/ml), streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) and 10% (v/v) FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Measurement of cell death and cell viability

Cell death was analyzed by PI staining coupled with microscopy or flow cytometry. Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega).

High-throughput RNAi genetic screens

The virus of the DECIPHER™ Lentiviral shRNA Library Mouse Module 1 with ∼27 500 shRNA hairpins targeting 4 625 genes was from Cellecta, Inc. RNAi screening was performed according to the user manual. Briefly, 8 × 107 MEFs were infected with virus at a low MOI (0.3) to ensure that most cells receive only 1 viral construct with high probability. After 48 h, 20% actual transduction efficiency was confirmed by flow cytometry and the cells were equally split into 2 samples (> 1 × 108 cells/sample). 24 h later, sample A was harvested and stored at −80 °C as control, and sample B with a 80% confluence was subjected to amino acid starvation plus killing of FBS for 16 h. The cells were changed back to full DMEM medium and recovered until cells get 80% confluence again. Repeat killing and recovery 3 more times. Sample A and sample B were subjected to genomic DNA isolation and HTseq sequencing of integrated barcodes. For sample A, 400 μg of genomic DNA is used for barcode PCR and HTseq sequencing. For the sample B, the entire recovered genomic DNA is used. shRNAs are evaluated based on barcode enrichment in sample B vs sample A. Gene hits are identified based on evaluation of targeting shRNAs.

Measurement of ROS

Total ROS measurement Cells were treated as indicated, and then 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, Life Technologies, Cat# D-399) was added and incubated for 1 h. Excess H2DCFDA was removed by washing the cells twice with PBS. Labeled cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS plus 5% FBS. Oxidation of H2DCFDA to the highly fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) is proportional to ROS generation and was analyzed using a flow cytometer (Fortessa, BD Biosciences). A minimum of 10 000 cells was analyzed per condition.

Lipid ROS measurement Cells were treated as indicated, and then 50 μM C11-BODIPY (Thermo Fisher, Cat# D3861) was added and incubated for 1 h. Excess C11-BODIPY was removed by washing the cells twice with PBS. Labeled cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS plus 5% FBS. Oxidation of the polyunsaturated butadienyl portion of C11-BODIPY resulted in a shift of the fluorescence emission peak from ∼590 nm to ∼510 nm proportional to lipid ROS generation and was analyzed using a flow cytometer.

Lentiviral-mediated shRNA interference

MISSION lentiviral shRNA clones targeting mouse or human NCOA4 and non-targeting control construct were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Lentivirus was packaged in 293T cells, and used to infect target cells which were then selected with puromycin for at least 3 days prior to use in experiments. The clone IDs for the shRNA targeting mouse NCOA4-sh1: TRCN0000095080; NCOA4-sh2: TRCN0000095083 and the clone IDs for the shRNA targeting human NCOA4-sh1: TRCN0000019724 and NCOA4-sh2: TRCN0000019726.

Measurement of GSH

2 × 105 MEFs were seeded in six-well plates. One day later, cells were treated as indicated for 6 h. Cells were harvested and cell numbers were determined. Total glutathione was measured as described previously34.

Fluorescence microscopy

HT1080 or MEF cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 were grown on glass cover slips in a six-well plate. 24 h later, cells were treated as indicated. Cover slips were then fixed with 3.7% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 for 30 min at room temperature. Cover slips were then mounted on microscope slides for visualization using Nikon Confocal Microscope using 60× magnification objectives.

Measurement of LIP

LIP was measured according to the methods described by Prus and Fibach35. Briefly, cells were trypsinized, washed twice with 0.5 ml of PBS, and incubated at a density of 1 × 106/ml for 15 min at 37 °C with 0.05 μM calcein-acetoxymethyl ester (AnaSpec). Then, the cells were washed twice with 0.5 ml of PBS and either incubated with deferiprone (100 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C or left untreated. The cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer. Calcein was excited at 488 nm, and fluorescence was measured at 525 nm. The difference in the cellular mean fluorescence with and without deferiprone incubation reflects the amount of LIP.

Measurement of transferrin internalization

Transferrin internalization and recycling were measured as described previously36. For transferrin internalization assay, cells were first treated with 1 μM erastin or DMSO for 2 h, and then cells were washed with PBS and incubated in serum-free medium plus erastin or DMSO for 30 min to remove any residual transferrin. Subsequently, cells were incubated with 25 μg/ml transferrin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) at 37 °C for the indicated times. Internalization was stopped by chilling the cells on ice. External transferrin was removed by washing with ice-cold serum-free DMEM and PBS, whereas bound transferrin was removed by an acid wash in PBS (pH 5.0) followed by a wash with PBS (pH 7.0). The fluorescence intensity of internalized transferrin was measured by flow cytometry. Data are normalized to the mean fluorescence of control cells incubated with transferrin for 10 min.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.0c GraphPad Software. P values were calculated with unpaired Student's t-test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments.

Author Contributions

M Gao, X Jiang conceived and supervised the study. M Gao performed most of the experiments in collaboration with P Monian and Q Pan. W Zhang and J Xiang performed high-throughput sequencing. M Gao and X Jiang analyzed the data and wrote the paper with suggestions from other authors. All authors reviewed the paper.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Jiang lab for discussing and reading the manuscript. This work is partially supported by NIH grants (R01CA166413 and R01GM113013 to XJ), a Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Foundation fund (to XJ), and NCI cancer center core grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Autophagy inhibitor BafA1 inhibits cystine starvation-induced ferroptosis in both MEFs and HT1080 cells.

The effect of autophagy inhibitors on ferroptosis is dose- and time-dependent.

Autophagy is required for ferroptosis.

Autophagy inhibitor BafA1 inhibits RSL3 starvation-induced ferroptosis in MEFs.

Erastin does not alter transferrin internalization.

References

- Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: Critical control points. Cell 2004; 116:205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science 2004; 305:626–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell 2011; 147:742–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum ES, Abraham MC, Yoshimura S, Lu Y, Shaham S. Control of nonapoptotic developmental cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans by a polyglutamine-repeat protein. Science 2012; 335:970–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Berghe T, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: the expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Kroemer G. Alternative cell death mechanisms in development and beyond. Genes Dev 2010; 24:2592–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol 2016; 26:165–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki K, Chan FK. RIP3: a molecular switch for necrosis and inflammation. Genes Dev 2013; 27:1640–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal 2010; 3:re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2003; 3:285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012; 149:1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell 2014; 156:317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell 2015; 59:298–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Monian P, Jiang X. Metabolism and iron signaling in ferroptotic cell death. Oncotarget 2015; 6:35145–35146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16:1180–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkermann A, Skouta R, Himmerkus N, et al. Synchronized renal tubular cell death involves ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:16836–16841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015; 520:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Overholtzer M, Thompson CB. Autophagy in cellular metabolism and cancer. J Clin Invest 2015; 125:47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Another way to die: autophagic programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ 2005; 12:1528–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Wan F, Dutta S, et al. Autophagic programmed cell death by selective catalase degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:4952–4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Shoji-Kawata S, Sumpter RM Jr, et al. Autosis is a Na+,K+-ATPase-regulated form of cell death triggered by autophagy-inducing peptides, starvation, and hypoxia-ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:20364–20371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Levine B. Autosis and autophagic cell death: the dark side of autophagy. Cell Death Differ 2015; 22:367–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdle WE, Nyfeler B, Nagel J, et al. Selective VPS34 inhibitor blocks autophagy and uncovers a role for NCOA4 in ferritin degradation and iron homeostasis in vivo. Nat Cell Biol 2014; 16:1069–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 2014; 509:105–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancias JD, Pontano Vaites L, Nissim S, et al. Ferritinophagy via NCOA4 is required for erythropoiesis and is regulated by iron dependent HERC2-mediated proteolysis. Elife 2015; 4:e10308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellelli R, Federico G, Matte A, et al. NCOA4 deficiency impairs systemic iron homeostasis. Cell Rep 2016; 14:411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev 2007; 21:2861–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews NC, Schmidt PJ. Iron homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol 2007; 69:69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, et al. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy 2016; 12:1425–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Marino G, Levine B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell 2010; 40:280–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife 2014; 3:e02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I, Kode A, Biswas SK. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat Protoc 2006; 1:3159–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prus E, Fibach E. Flow cytometry measurement of the labile iron pool in human hematopoietic cells. Cytometry A 2008; 73:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padron D, Tall RD, Roth MG. Phospholipase D2 is required for efficient endocytic recycling of transferrin receptors. Mol Biol Cell 2006; 17:598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Autophagy inhibitor BafA1 inhibits cystine starvation-induced ferroptosis in both MEFs and HT1080 cells.

The effect of autophagy inhibitors on ferroptosis is dose- and time-dependent.

Autophagy is required for ferroptosis.

Autophagy inhibitor BafA1 inhibits RSL3 starvation-induced ferroptosis in MEFs.

Erastin does not alter transferrin internalization.