Abstract

Water molecules inside a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) have recently been spotlighted in a series of crystal structures. To decipher the dynamics and functional roles of internal water molecules in GPCR activity, we studied the A2A adenosine receptor using microsecond molecular-dynamics simulations. Our study finds that the amount of water flux across the transmembrane (TM) domain varies depending on the receptor state, and that the water molecules of the TM channel in the active state flow three times more slowly than those in the inactive state. Depending on the location in solvent-protein interface as well as the receptor state, the average residence time of water in each residue varies from ∼(102) ps to ∼(102) ns. Especially, water molecules, exhibiting ultraslow relaxation (∼(102) ns) in the active state, are found around the microswitch residues that are considered activity hotspots for GPCR function. A continuous allosteric network spanning the TM domain, arising from water-mediated contacts, is unique in the active state, underscoring the importance of slow water molecules in the activation of GPCRs.

Introduction

The activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) is associated with a conformational change of the receptor modulated by an agonist binding. As suggested by the x-ray crystal structure of the β2-adrenergic receptor, the outward tilting of TM5 and TM6 helices that accompanies a helix rotation of the cytoplasmic part of TM5-ICL3-TM6 is one of the key structural changes that facilitate G-protein recruitment (1, 2, 3). More microscopically, orchestrated dynamics among a common set of highly conserved fingerprint residues, dubbed “microswitches”, of the class-A GPCR family, is critical for the regulation of GPCR activity (4, 5). These microswitches, including three ubiquitous sequence motifs, DRY, CWxP, and NPxxY (where x denotes any amino acid residue), adopt distinct rotameric configurations in their side chains, which are sensitive to the type of a cognate ligand bound to the orthosteric site (6). In the agonist-bound state, the dynamic correlations among microswitches allow the receptor to adopt and maintain the active conformation, which facilitate accommodation of G-protein (6).

Besides the allosteric network defined by the interresidue contacts (6, 7), water molecules can also contribute to the formation of the intrareceptor signaling network. Given that GPCRs are the key therapeutic targets that sense and process external stimuli with an exquisite precision, it is critical to understand the roles played by water as well as the residue dynamics in GPCR activation. As is well appreciated by many studies, water is essential for the structure, dynamics, and function of biomolecules (8, 9, 10). Water molecules that form a hydration shell on protein surfaces (8, 11, 12, 13) or a lipid-mediated effect of water via hydrophobic matching to the protein surface (14) have long been studied. Possible functional roles of internal water molecules that were found inside the TM domain in GPCR activation have been discussed in Yuan et al. (15, 16), Sun et al. (17), Burg et al. (18), and Leioatts et al. (19). Recently, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations studies have analyzed water in various type of GPCRs, including A2A AR (15, 20, 21, 22), β2-adrenergic receptor (23), rhodopsin (17, 19, 24, 25), dopaminergic receptor (26), and μ-opioid receptor (16); yet the foci of these studies were mostly on mapping the locations of internal water molecules and metal ions inside the TM domain, or on the local dynamics of water specific to the ligand binding cleft in the process of ligand-receptor recognition (22). Dynamical properties of internal water over the entire architecture of GPCR have not fully been discussed. While x-ray crystal structures provide a glimpse of ordered water molecules interacting with the interior of GPCRs (16, 18, 27, 28), these structural water molecules are not completely static but have finite lifetimes. Furthermore, the roles of mobile water molecules with relatively faster relaxation kinetics remain unknown. Thus, it is timely to examine the dynamics of water in GPCR and ask the functional roles of water in conjunction with the local dynamics of amino acid residues.

Here, we explored water dynamics in A2A AR by conducting microsecond all-atom MD simulations. To assess the role of water dynamics in GPCR function, we strategically evaluated various quantities. We first calculated the water capacity in the TM region, and mapped the probability density of water for each receptor state. Explicit calculation of water flux through the TM region has revealed that the water flux in the agonist (UK432097)-bound active form is three times smaller than that in the apo or antagonist (ZM241385)-bound form. Water streams are divided into multiple pathways, some of which form a one-dimensional “water wire” (29, 30, 31). The receptor surfaces, mapped with the water relaxation time, indicate that the water dynamics is heterogeneous in space. Water molecules in the extra- and intracellular domains move fast (≲1 ns). Especially in the agonist-bound form, water molecules trapped around the microswitches display ultraslow relaxation (≳100 ns), coating the polar and charged surface of the TM channel. Our study finally shows that a water-mediated interresidue interaction network, formed along microswitches in TM7, reinforces and extends the range of allosteric interface in the active state, aiding robust activation of GPCRs.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of the receptor structures complexed with ligands

The x-ray crystal structures of A2A AR bound with an agonist or antagonist were modeled based on the structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (32, 33). We used the x-ray crystal structures with PDB entries of PDB: 3QAK (32) for the agonist-bound model and PDB: 3EML (33) for the antagonist-bound model, and used UK432097 and ZM241385 for agonist and antagonist ligands, respectively. Because some of the loop regions are not resolved in the crystal structures, we performed homology modeling using the MODELLER program (https://salilab.org/modeller/) implemented in Discovery Studio Ver. 3.1 (Accelrys, San Diego, CA) to prepare the full-length A2A AR models including all the loop regions. The x-ray crystal structures PDB: 2YDV (3) and PDB: 3PWH (34) were used to model the loop regions missing in PDB: 3QAK and PDB: 3EML, and the conserved disulfide bridges connecting the loops, i.e., C71–C159, C74–C146, C77–C166, and C259–C262, were retained. These models were optimized by simulated annealing and selected based on the DOPE score. The final structures were obtained by energy-minimization using the conjugate gradient method and the generalized-Born with simple-switching-implicit-solvent model.

Although an antagonist-bound engineered crystal structure of A2A AR complexed with apocytochrome b562RIL replacing intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) (PDB: 4EIY (27)), whose structure was fully determined with no missing region including extracellular (EC) and intracellular (IC) loops, became available after we started this research, the extent of structural overlap between the crystal structure and our modeled structure is as high as Cα-root mean-squared deviation (RMSD) = 0.407 Å. Furthermore, as the memory of initial configuration, especially the initial configuration of flexible loops, would be erased after some time (at most a few tens of nanoseconds), and an identical force field is used for simulation, the conclusion of this study would not be altered even when a more precise and accurate structure is used as a starting conformation for the simulation run. For the apo form, we used the protein structure, minimized after removing the antagonist ligand from the original structure (PDB: 3EML) as a starting conformation of our MD simulations.

MD simulations

To construct the explicit membrane system, the transmembrane region of A2A AR was predicted based on the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database (http://opm.phar.umich.edu/) and the hydrophobicity of the protein. Using SOLVATE 1.0 (http://www.mpibpc.mpg.de/home/grubmueller/solvate), we first solvated the receptor structure with TIP3P water molecules and removed the water molecules that were outside the receptor in the TM region. Then, the 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) lipid bilayer (88 × 91 Å2 wide) was placed around the TM region of A2A AR. After aligning the initially solvated receptor structure and the bilayer system, we removed the lipid and water molecules overlapping within the distance of 0.5 Å from the receptor structure. The prepared system was solvated with the water box, covering all the previous output molecules, and neutralized with K+/Cl− ions to make 150 mM salt concentration. Our system contains 68,799 (apo, 13,549 water + 173 lipid), 70,052 (antagonist-bound, 13,551 water + 182 lipid), and 69,449 (agonist-bound, 13,552 water + 177 lipid) atoms in a 85 × 88 × 99 Å3 periodic box.

MD simulations were performed using NAMD package v.2.8 (35) with the CHARMM22/CMAP force field (36). The topology and parameter files for the ligands were generated by the SwissParam web server (http://www.swissparam.ch/), which provides topologies and parameters for ligands based on the Merck molecular force field, and is compatible with the CHARMM force field (37). The simulations were then conducted with the following steps: 1) energy-minimization for 2000 steps using conjugate gradient method in the order of membrane, water molecules, protein structure, and the whole system; 2) gradual heating from 0 to 300 K using a 0.01 K interval at each step; 3) 50 ns preequilibration with NVT ensemble before the production runs; and 4) 1.2 μs production runs with the NPT ensemble (T = 300 K, P = 1 atm). Pressure was maintained at atm using the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston method with an oscillation period of 200 fs and a decay time of 50 fs. The temperature was controlled by applying Langevin forces to all heavy atoms with a damping constant of 1 ps−1. Nonbonded interactions were truncated with a 12.0 Å cutoff and a 10.0 Å switching distance, and a particle-mesh Ewald summation with a grid spacing 0.91 Å was used to handle electrostatic interactions. We used a uniform integration time step of 1 fs, and during all of the production runs, no specific constraints were applied to the system except for restraining the hydrogen atoms. The SETTLE algorithm was used to keep water molecules rigid, and the SHAKE algorithm was used to restrain the bond lengths of hydrogens other than those of water molecules. The atomic coordinates of the simulated system were used every 50 ps for water flux analysis and 400 ps for other calculations.

Importantly, in the production runs it takes >200–300 ns to fully equilibrate the (receptor + lipid bilayer) system in NPT ensemble. Water molecules fill the TM channel gradually (Fig. 1). While the protein RMSD gets to its steady state at t ≲ 200 ns (Fig. S1 A in the Supporting Material), the area per lipid or the bilayer thickness is still under relaxation in the first 200–300 ns (see Fig. S1, B and C). In the steady state, the area per lipid (APL) for the POPC molecule is ∼61 ± 2 Å2 and bilayer thickness is ∼40 Å, which compare well with the experimental values at T = 27°C (APL ∼ 63 ± 2 Å2, thickness ∼39 ± 1 Å) as well as with other simulation studies (38, 39). After the first t = 0–300 ns simulation, we restrained the xy-plane area of the simulation box by using the option of “useConstantArea” in the NAMD package. As a result, the APL value and the thickness of the lipid bilayer are stably maintained for t ≥ 300 ns. In our study, the production runs of the first 0–400 ns, which could usually be regarded as a long simulation time, are still in the process of nonequilibrium relaxation. Thus, we conducted various analyses in this study using the data from ns after the system had reached the steady state.

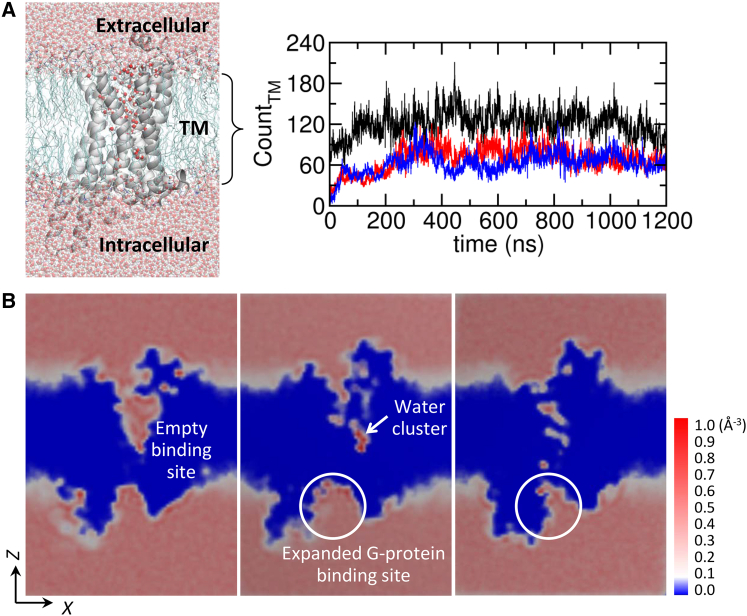

Figure 1.

Water molecules in the TM region. (A) The number of water molecules occupying the TM regions as a function of time in the apo (black), agonist-bound (red), and antagonist-bound (blue) forms. On the left depicted is a snapshot of water permeating through the TM region. (B) Probability density map of water ρ(r) at each three-dimensional grid point r (0 ≤ ρ(r)Δr ≤ 1 with the grid cell volume of Δr = ΔxΔyΔz = 1 Å × 1 Å × 1 Å) calculated for the apo, agonist-bound, and antagonist-bound states based on the final 200 ns of simulation. Two-dimensional slices of ρ(r) were calculated using the VolMap plugin in the software VMD (http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Research/vmd/). To see this figure in color, go online.

Time correlation function to probe water unbinding kinetics

To quantitatively probe the dynamics of water near the receptor structure, we calculated the autocorrelation function (40, 41):

| (1) |

The function describes whether a contact is formed between an atom in the receptor and a water molecule at time t. The value for a water molecule within 4 Å from any heavy atom of a residue α at time t; otherwise, . The measurement denotes a time average along the trajectory and an ensemble average over the number of water molecules (Nα) associated with the residue α. Because , is equivalent to the survival probability of a bound water at time t. Thus, the average lifetime of water is obtained using .

Betweenness centrality

Simplifying a structure of complex systems into a graph, represented with vertices and edges, can be used as a powerful means to extract key structural features of the system (42, 43, 44, 45). The graph theoretical analysis can be performed for protein structures (46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51) to judge the importance of each vertex that defines the graph. For instance, a residue in contact with many other surrounding residues, which in the language of graph theory is called a “vertex with high degree centrality”, could be deemed important for characterizing a main feature of the given structure. However, to address the issue of allostery, the betweenness centrality can be used for quantifying the extent to which a node (ν) has control over the transmission of information between nodes in the network (45). The betweenness centrality is defined as

| (2) |

with . The value is the number of paths with the shortest distance linking the nodes s and t, and is the number of minimal paths linking the nodes s and t via the node ν.

To build a network (graph), the residue-residue contact was defined 1) for water-free contact using the threshold distance of 4 Å between any two heavy atoms of two residues; and 2) for water-mediated contacts between two residues if a water oxygen is shared within 3.5 Å by any two heavy atoms of two residues or if the two residues are within 4 Å. To quantify the importance of the νth residue in mediating signal transmission, we calculated two distinct betweenness centralities: 1) the values for a water-free and 2) for a water-mediated interresidue network of GPCR. The and values calculated for each snapshot of the molecular structure were averaged over the ensemble of structures obtained along the MD trajectories. To calculate , we employed the Brandes algorithm (52), which substantially reduces the computational cost of Eq. 2.

Results

Water capacity in the TM region

Our simulations show that it takes >200–300 ns for water molecules to fill the empty TM channel and to reach the steady state (Fig. 1 A; see also Fig. S1 for the time evolutions of the receptor RMSD, area per POPC lipid, and membrane thickness). In the steady state, on average 121 ± 20, 69 ± 18, and 63 ± 16 water molecules are found in the interior (between the phosphate atoms of upper and lower leaflets) of the apo, agonist-bound active, and antagonist-bound inactive states, respectively (Fig. 1 A). As depicted in the probability density map of water (Fig. 1 B), the apo form, due to the water-filled ligand binding cleft, contains twice the volume of the water compared with the other ligand-bound states. In the ligand-bound states, a large volume of water has to be discharged from the vestibule. The expanded G-protein binding cleft is also seen in the agonist-bound active state (Fig. 1 B, middle). A water cluster, whose functional role will be further discussed in the Discussion, is identified in the midst of the TM domain (see the white arrow in Fig. 1 B, middle).

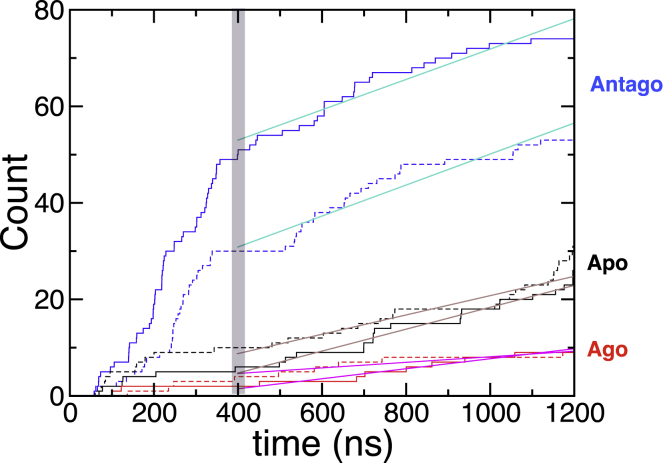

Water flux through the TM pore

Although the average number of water molecules in the TM channel remains constant in the steady state (Fig. 1 A, t ≳ 400 ns), this does not imply that water is static inside the channel. The numbers of water molecules in and out of the channel are balanced in the steady state. To compare the water flux between the different receptor states, we traced the coordinate of every water molecule along the axis (z axis) perpendicular to the lipid bilayer plane and counted the number of water molecules that traverse the channel from the EC to the IC or from the IC to the EC domain (Fig. 2). In the early stage of simulations, non-steady-state fluxes are observed in the apo and antagonist-bound forms. Thus, we excluded the first 400 ns from the analysis. For ns, the water fluxes in the two directions satisfy in all the receptor states. Overall, the water flux of the antagonist-bound state is threefold greater (jantago ∼ 30 μs−1) than that of the agonist-bound state (jago ∼ 10 μs−1). The water flux of the apo state lies in between (japo ∼ 20 μs−1). In fact, the lowest water flux in the agonist-bound form has its molecular origin. Below we will map each receptor state by probing the relaxation kinetics of water around each residue, which will help elucidate the role of water in receptor activation as well as the molecular origin of differential water fluxes.

Figure 2.

Water flux through the transmembrane region. The number of water molecules traversing the TM domain as a function of time (EC IC, solid lines; IC EC, dashed lines). Water fluxes (j) through the receptor, calculated using the slope from linear fits to the data over the interval 400 < t < 1200 ns, are j ≈ 30 (antagonist), 20 (apo), and 10 μs−1 (agonist). To see this figure in color, go online.

Relaxation kinetics of water

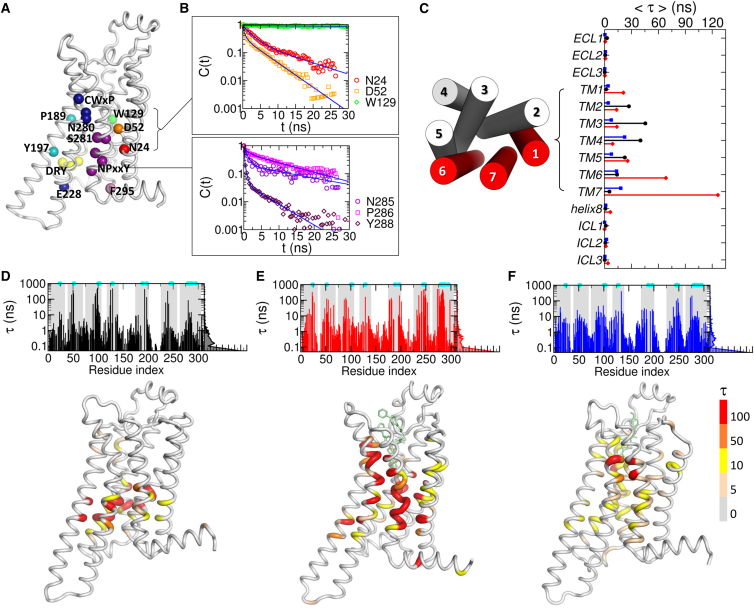

We mapped the water dynamics on the receptor surfaces by computing time correlation functions of water from each residue (C(t); see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 3, A and B). Water in the vicinity of the IC or EC loops, exposed to the bulk, is expected to have a shorter lifetime. In the TM region, in contrast, the dynamics of water is much slower (Fig. 3 C), displaying a broad spectrum of relaxation times depending on 1) the receptor state and 2) their locations (Fig. 3, D–F). The average lifetimes of water are 14.5, 26.3, and 7.1 ns for the apo, agonist, and antagonist-bound states, respectively. The water molecules, hydrating the TM1, TM6, and TM7 helices in the agonist-bound form, reside longer than 100 ns, especially around the microswitches (marked with the cyan circles at the top of Fig. 3, D–F). This long residence time of water in the interior of the TM domain (≳(100) ns) is noteworthy, given that a typical water lifetime on a biomolecular surface probed by a spin-label measurement is ∼(100) ps (53, 54).

Figure 3.

Relaxation kinetics of water mapped on A2A AR structure. (A) Location of the microswitches. (B) Time correlation functions of water from six key residues are fitted to multiexponential functions (see the Supporting Material). (C) Average relaxation time of water from various regions (TM, ECL, and ICL) in the apo (black), agonist-bound (red), and antagonist-bound (blue) forms. The extracellular view of the TM helices is shown on the left. TM1, TM2, and TM7, which have much longer relaxation time in the agonist-bound form, are marked in red. (D–F) Water relaxation time (τ) from each residue in (D) the apo, (E) the agonist-bound, and (F) the antagonist-bound forms. The TM regions are shaded in gray, and the positions of microswitches are marked with cyan dots. The receptor structures are colored based on the τ-values. To see this figure in color, go online.

Similar conclusions as the above analysis calculating relaxation times were drawn by calculating the Fano factor involving water number fluctuation around each residue (see the Supporting Material text and Fig. S2).

Discussion

Detailed look into water flux across the TM domain

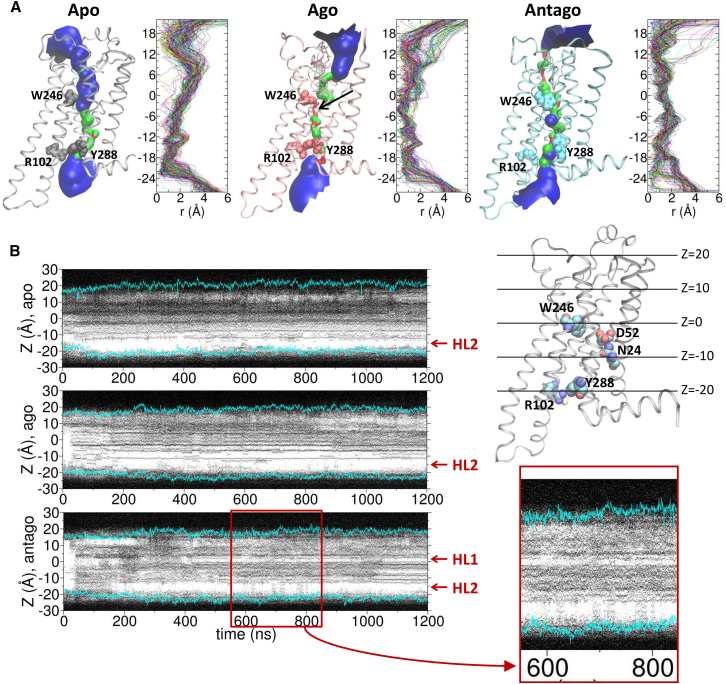

To glean the molecular origin of receptor state-dependent water flux, we first visualize the geometry of water channel. The radius of the water channel, calculated using the program HOLE (55) (see Fig. 4 A), reveals that the geometrical bottleneck (r ≈ 0) in the midst of TM domain (Z ≈ 0) (Fig. 4 A, see the black arrow) is formed around W2466.48 and Y2887.53 in the agonist-bound active form. This is compatible with our finding that the water flux is substantially reduced in the agonist-bound form (Fig. 2). W2466.48, a key microswitch that senses an agonist and relays its signal to other microswitches (6, 56), is located deep inside the orthosteric binding vestibule, regulates the entry of water from the EC domain; whereas Y2887.53 is located at the lower part of TM channel, regulating the entry of water from the IC domain.

Figure 4.

Water occupation map of the TM channel. (A) The channel formed across the TM domain of each receptor state using the 250 snapshots from 1000 to 1200 ns for the apo form, and from 600 to 800 ns for the agonist-bound and antagonist-bound forms, at which the highest water flux is observed. The channel surfaces, calculated using the program HOLE (55), are colored to visualize the channel radius (red (r < 1.15 Å), green (r = 1.15 ∼ 2.30 Å), and blue (r > 2.3 Å)). Channel radii (r) along the z axis are shown on the right with a different color for each frame. (B) Water occupancy maps along the axis perpendicular to the bilayer, calculated for the simulations of the apo (top), agonist- (middle), and antagonist-bound forms (bottom). The positions of two hydrophobic layers (HL1 and HL2) are marked with red arrows. The position of the lipid headgroup is in cyan lines on the map. A magnified view of the water occupation map for 600 ≲ t ≲ 800 ns is provided. On the right, the apo structure is displayed with the key microswitches. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although the geometry of channel in each receptor state provides a glimpse of pipeline across the TM region, the actual water flux through the channel is not fully explained by the radii of the channel alone. For example, the apo state, overall, has greater radii along the channel and does not have a particularly more restrictive geometrical bottleneck than those in the antagonist-bound state (Fig. 4 A); yet the flux is smaller than the one observed in the antagonist-bound state. Depending on the extent of hydrophobicity or electrostatic nature of residues comprising each region of the channel surface, stochastic wetting-dewetting transition (30, 57, 58) can occur along the channel. Furthermore, a stable water cluster in the channel, not exchanging water molecules with the surroundings, would impede the water dynamics through the channel. Explicit calculations of water occupancy along the z axis (58) visualize how water molecules actually fill the TM channel at time t (Fig. 4 B). As expected, in the apo state (Fig. 4 B, top), the EC region (Z > 0 Å) is always filled with a high density of water because the empty ligand binding pocket is accessible from the bulk; however, the IC region (−20 ≲ Z ≲ −10 Å) remains dry, indicating that the entry of water through the IC region is blocked. This dry zone corresponds to the second hydrophobic layer (HL2) around the NPxxY motif above Y2887.53, illustrated by Yuan et al. (15). In the agonist-bound form, another water-free layer is observed right above the HL2 (−10 < Z < −5 Å) (Fig. 4 B, middle). This is the region below which the water cluster is formed. On the other hand, the first hydrophobic layer (HL1) (15), corresponding to another dry zone between the orthosteric and the allosteric sites (15), (Z ≈ 0 Å) is observed in the inactive state. Notably, despite the HL1, the water occupancy map of the antagonist-bound form (Fig. 4 B, bottom) finds multiple instances (t = 600–800 ns) that both HL1 and HL2 are filled with water bridging across the entire TM region. This accounts for the greater water flux in the inactive state.

The location of the hydrophobic layer and the receptor state-dependent water fluxes are affected by the alignment of polar residues along the channel. The TM domain is mostly composed of nonpolar hydrophobic residues, but there are polar/charged amino acids buried inside the TM domain as well. The streams of water molecules are found along a Y-shaped array of these polar and charged residues that bridge through the TM domain (Fig. S3). This array of polar/charged residues corresponds to the buried ionizable networks in GPCRs that have recently been underscored (59). Our study reveals that these networks shape the passages of water molecules through the TM domain. A misalignment of polar residues in the agonist-bound state is led to dehydration of the IC zone at ∼−20 < Z < −10 Å, which gives rise to the HL2 (Fig. S3, left). The rotameric state of Y2887.53 side chain in the antagonist-bound form enables a single file of water molecules constituting a water wire to flow across the HL2 (Fig. S3, right; Movie S3 in the Supporting Material. See also Fig. S4). The formation of the Y-shaped bridge made of polar residues including the NPxxY motif is the molecular origin underlying the “hydrophobic gating” (60, 61) that regulates the water flux through the IC region of A2A AR.

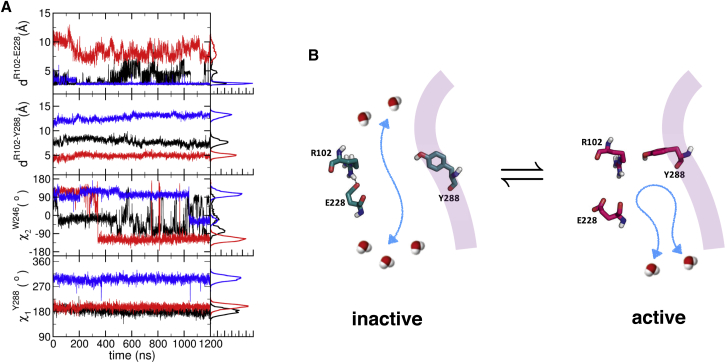

Microscopic origin of receptor state-dependent water flux

To further glean the microscopic underpinnings of the receptor state-dependent water flux (Fig. 2), configurations of microswitches at three key locations in the TM domain are probed (Fig. 5): 1) The ionic lock (R1023.50-E2286.30; Fig. 5 A, top panel), the hallmark of the inactive state of GPCRs, is intact in the antagonist-bound form, maintaining the interresidue distance dR102-E228 ≈ 2.5 Å. In the apo form, the ionic-lock repeatedly disrupts and rebinds, suggestive of the receptor’s basal activity (62). In the agonist-bound form, the ionic lock is completely disrupted. 2) The distance between R1023.50 and Y2887.53 depends on the receptor state (Fig. 5 A, second panel from the top), and importantly Y2887.53 gates the entry of water from the IC region. In the active form, R1023.50 released from the influence of E2286.30 can interact with and stabilize the side-chain orientation of Y2887.53, resulting in blocking the passage of water stream as well as misaligning the bridge made of NPxxY motif (see Movie S2; Fig. 5 B; Fig. S3). 3) The side chain of W2466.48 residue gates the entry of water from the EC domain. In the active form, W2466.48 blocks the water passage from the EC region, but it allows water to flow more freely in the inactive form. In the apo form, the rotamer angle of W2466.48 undergoes sharp transitions ( in Fig. 5 A, black trace) multiple times during the simulation (500 ≲ t ≲ 1000 ns), displaying correlations with the ionic-lock (dR102-E228 in Fig. 5 A, black line) and with the increased level of water flux (notice the sudden increase of the flux at t ≈ 500 ns from EC to IC (black trace in solid line in Fig. 2)). For example, when the ionic-lock was stabilized at ≈1000 ns in the apo form (Fig. 5 A, top panel, black trace), the rotameric angle of W2466.48 also displayed a sharp change from −90° to +90° (cyan arrow in the plot of Fig. 5 A). This is the moment when in the apo form has increased (t > 1000 ns in Fig. 2).

Figure 5.

Configuration of ionic-lock and Y288 associated with water flux gating. (A) Time traces probing the dynamics of three major structural motifs, i.e., ionic-lock (DRY motif), W2466.48 of CWxP, and Y2887.53 of NPxxY. From the top shown are the distances between R1023.50 and E2286.30 (ionic-lock), and between R1023.50 and Y2887.53, and the dihedral angles of W2466.48 and Y2887.53 for the apo (black), agonist-bound (red), and antagonist-bound (blue) forms. The histograms on the right are drawn using data with t > 400 ns. (B) The configurations of R1023.50, E2286.30, and Y2887.53 in the inactive and active states. The ionic lock (R102-E228) in the inactive form is disrupted in the active form, allowing R102 to form a contact with Y288. The passage of water from the IC domain is blocked by this change in the active form. The helix 7 is illustrated with the transparent band in purple. To see this figure in color, go online.

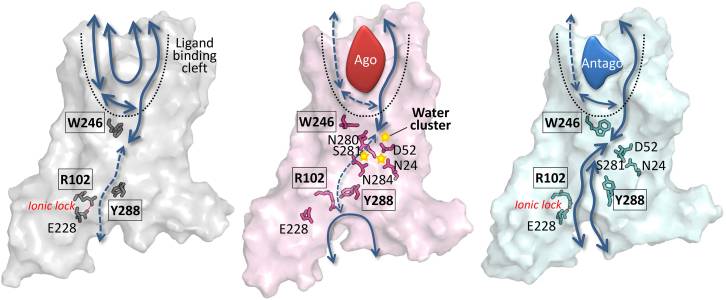

Movie S1, Movie S2, and Movie S3, from simulations of the water dynamics across the TM region, provide nice visualizations of receptor state-dependent water flux, which is recapitulated in the cartoons in Fig. 6. In the apo form, the water molecules freely navigate the wide volume of the empty ligand binding cleft in the EC domain, but a further penetration across the TM region is regulated by the narrow channel gated by W2466.48. When the agonist or antagonist occupies the binding cleft, however, water flux is divided into the major (solid lines in Fig. 6) and minor streams (dashed lines in Fig. 6); the major stream is formed between TM1, 2, and 7, and the minor stream is formed between TM3, 5, and 6. In the agonist-bound form, the W2466.48 blocks the minor stream and the water flow along the major stream is tightly regulated by the several other microswitch residues (N241.50, D522.50, N2807.45, S2817.46, and N2847.49), which creates the stable water cluster. In the case of the antagonist-bound form, no water cluster is observed; the W2466.48 gate is open and lets water molecules flow in and out of the TM channel. The water flux from the IC region is regulated by the side-chain configuration of Y2887.53. In the active state whose ionic-lock is disrupted, R1023.50 interacts with Y2887.53, which in turn blocks the passage of water flux in the IC domain.

Figure 6.

Water flux map of A2A AR. Schematics of the water flux map (apo, agonist-bound, and antagonist-bound forms from the left to the right) are drawn based on the water dynamics from Movie S1, Movie S2, and Movie S3. The major and minor paths of water flux are depicted in solid and dashed lines, respectively. The key microswitches are depicted in sticks, and the residues of the three major structural motifs, i.e., R1023.50 of DRY, W2466.48 of CWxP, and Y2887.53 of NPxxY, are enclosed in the boxes. In the agonist-bound form, the microswitches (N241.50, D522.50, N2807.45, N2847.49, and S2817.46) in TM1, 2, and 7 form a water cluster and block the water flux. The breakage of the ionic-lock brings R1023.50 closer to Y2887.53 in TM7, blocking the entry of water from the IC domain. To see this figure in color, go online.

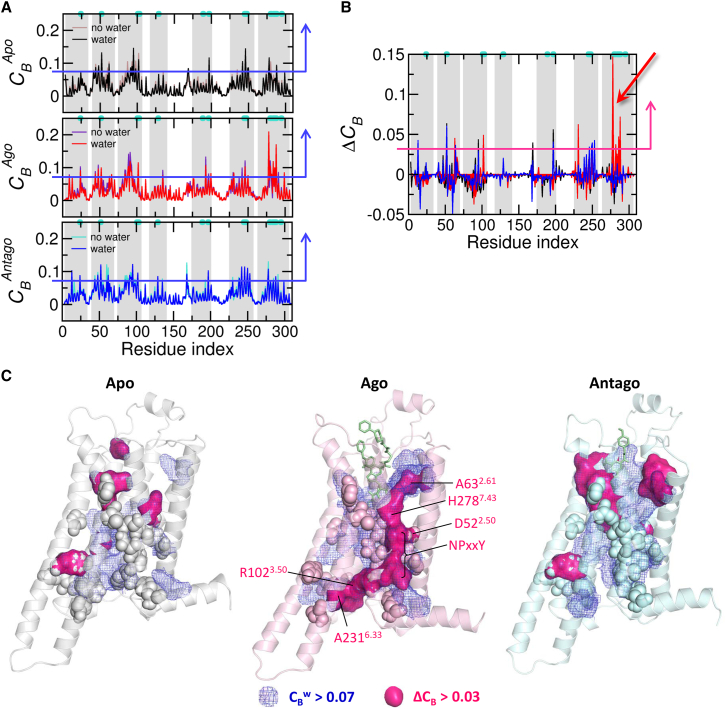

Allosteric interface reinforced by water-mediated interactions

To underscore the contribution of water-mediated contacts between TM residues to the receptor’s allosteric signaling and function, we conducted a graph theoretical analysis on the ensemble of GPCR structures. As shown by our previous study (7), the microswitches of GPCRs in general are identified by graph theoretical analysis using betweenness centrality to be the key sites for intramolecular orthosteric (allosteric) signal transmission (see Materials and Methods). An allosteric interface can be visualized by highlighting those allosteric hotspots (7). While water molecules inside the channel are generally dynamic, some water molecules, especially around microswitches in the active state, display slow relaxation kinetics and can even be trapped for an extended amount of time (τ > (102) ns) (see Supporting Material text and Figs. S5 and S6). As long as the water dynamics is sufficiently slow, stable water-mediated contacts can be made between two residues that are not in direct contact. Defining a water-mediated contact when two residues share a water oxygen within 3.5 Å from any heavy atom in each residue, we constructed a water-mediated residue interaction network for a given structure. Using an ensemble of structure obtained from simulations, we calculated an average betweenness centrality at the νth residue (see the Supporting Material and Fig. 7 A). At present, there are many ways to consider the protein allostery; some of them consider the thermodynamic aspect of protein allostery (63, 64), and others focus more on identification of an allosteric hotspot of a given structure (65, 66, 67). The graph theoretical method (7, 68, 69, 70) can also be employed to identify an allosteric hotspot of a given network structure, and in this method a residue with a high value corresponds to a site important for allosteric signal transmission (7).

Figure 7.

Allosteric interface extended by water-mediated interactions. (A) Betweenness centralities calculated with and without water-mediated interaction for each receptor state. Water-free contact between two residues is defined if any heavy atom in one residue is within 4 Å from other residue; water-mediated contact between two residues is defined if a water oxygen is shared by two residues within 3.5 Å. (B) (≡ − ) for each state. Large values of are identified around the TM7 helix in the agonist-bound active state (red arrow). (C) Regions with > 0.07 (corresponding to the top 10% of values, blue mesh, and blue arrows in (A)) and > 0.03 (magenta surface in (C) and a magenta arrow in (B)) are demarcated on the structure of the active state. The microswitch residues are depicted as spheres. To see this figure in color, go online.

In the agonist-bound active state, the values calculated with and without water-mediated contacts (see Fig. S7) show clear differences (δCB(ν)) along the microswitches in TM7 (Fig. 7, B and C), which is in accord with our findings that a number of slow water molecules stably coordinating with microswitches along the water channels are present in the active state. Highlighted in Fig. 7 C with magenta surface is the allosteric interface in the active state reinforced by water-mediated interactions (δCB(ν) > 0.03). The interface mainly formed from along the TM7 helix, reaches R1023.50 in the TM3 helix via Y2887.53 and A2316.33, spanning the whole TM domain. We surmise that this widespread interface across the TM domain enables a robust long-range signal transmission (compare the map of agonist-bound active state with those for apo- and antagonist-bound inactive states in Fig. 7 C). Notably, recent calculation of energy transport in homodimeric hemoglobin also underscores the importance of the interface water cluster, substantiating our proposal of ultraslow water-mediated allosteric signaling (71).

Conclusions

Systematic analyses of GPCR structures reveal the network of inter-TM contacts mediated by microswitches (28). Network analysis also put forward that these microswitches act as the hub of the intrareceptor signaling network of A2A AR (7), and analyses of MD simulation trajectories confirmed that dynamics of microswitches occurs in concert (6). Here, we extended our analysis to the dynamics of water molecules traversing through the TM channel and investigated their role in allosteric (orthosteric) signaling.

As is well appreciated, water, an essential component of living systems, provides a driving force for self-assemblies of biomolecules and enhances their conformational fluctuations (11, 41, 72, 73, 74). Without water, biomolecules cannot function (10). Guided by the array of polar residues, water permeates inside the mostly dry and hydrophobic pore of GPCRs. In the antagonist-bound inactive state, this array of polar residues is connected continuously from the EC to the IC domain. In accord with Yuan et al. (15, 21), our simulations confirm the presence of the two hydrophobic layers, HL1 and HL2; however, these hydrophobic layers are not static, but highly dynamic. Our study also confirms the finding of Yuan et al. (21) that the water flux along the TM channel is regulated by the rotameric states of several microswitches (Fig. 6). Among them, two key microswitches, W2466.48 and Y2887.53, act together to form an “AND-gate” controlling the water flow.

There are also other MD simulation studies on GPCRs (e.g., rhodopsin (19)) proposing that a continuous stream of internal water is important for GPCR activation. By counting the number of water molecules inside the TM domain, Leioatts et al. (19) showed that upon an elongation of retinal, an influx of water increases inside the TM domain rhodopsin. They found that the increase of hydration level was significant in the complex-counterion simulation of rhodopsin, but not in the dark state. Their simulation results on water hydration in the dark state of rhodopsin differ from A2A AR in the inactive state in that only 20–30 water molecules are allowed inside the TM domain during the 1.6 μs simulation time (19). However, the hydration level in the complex-counterion form is consistent with our study on the active form of A2A AR in terms of the number of water molecules filling the TM channel. In our study, both active and inactive states of A2A AR could accommodate approximately an equivalent amount of water molecules, 60–100, at steady state (Fig. 1 A), but the water flux in the inactive form was found greater than that in the inactive form by three times (Fig. 2). Here, it is crucial to distinguish the flux of water across the TM domain (Fig. 2) from the number of water molecules inside the TM domain (Fig. 1). As described in Results, the water flux across the TM domain was calculated by tracing the individual water molecules and counting the number of water molecules that enter and exit from one side of the membrane to the other. It is not merely the increase of TM water with time. While the number of water molecules inside the dark state of rhodopsin is smaller than that in the inactive state of A2A AR, the water flux in the dark state of rhodopsin could also be large. Our study puts more emphasis on the dynamic aspect of water molecules across the TM domain in the steady state, which leads us to further ask the questions of which residues are hydrated by slow water and how those slow water molecules contribute to the water-contact-mediated allosteric network.

Our explicit calculations of water fluxes indicate that the continuous water stream can be formed in all three states (i.e., j ≠ 0 in Fig. 2), but with differing degrees. Thus, we want to argue that what is more relevant for GPCR activation are the water-mediated contacts among the key allosteric residues rather than the existence of a continuous water stream. It is easier to make a water-mediated contact if a water molecule is slower. In the agonist-bound active state, water molecules inside the TM channel are almost stagnant, displaying minimal flux (Fig. 2); they can stably hydrate the microswitches mainly along the TM7 helix. We show that the water-mediated residue network extends from the extracellular domain to the intracellular part of the TM6 helix via the TM3 helix (Figs. 3 and 7).

The water molecules around TM microswitches, some of which constitute the water cluster, stabilize the relative orientation and distance between TM helices by bridging them together (Figs. 7 and S7). Our study highlights the interactions of internal water with microswitches, which contribute to extending and reinforcing the allosteric interface of GPCRs (Fig. 7). Our study puts forward that these interactions are especially critical for the functional fidelity of the GPCR activity.

Author Contributions

Y.L., S.K., S.C., and C.H. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Korea Institute for Advanced Study (KIAS), and the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) Supercomputing Center for providing computing resources.

This work was supported by grant No. 2011-0028885 from the National Leading Research Laboratory program, funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning and the National Research Foundation of Korea (to S.C.), and by RP-Grant 2015 funded by Ewha Womans University (to S.C. and Y.L.).

Editor: Scott Feller.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, seven figures, and four movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30658-0.

Contributor Information

Sun Choi, Email: sunchoi@ewha.ac.kr.

Changbong Hyeon, Email: hyeoncb@kias.re.kr.

Supporting Material

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

The receptor structure is represented as white ribbon, and two water molecules that compete around are depicted using spheres in cyan and green.

References

- 1.Rosenbaum D.M., Rasmussen S.G., Kobilka B.K. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–363. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rasmussen S.G., DeVree B.T., Kobilka B.K. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebon G., Warne T., Tate C.G. Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature. 2011;474:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nygaard R., Frimurer T.M., Schwartz T.W. Ligand binding and micro-switches in 7TM receptor structures. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katritch V., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013;53:531–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y., Choi S., Hyeon C. Communication over the network of binary switches regulates the activation of A2A adenosine receptor. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y., Choi S., Hyeon C. Mapping the intramolecular signal transduction of G-protein coupled receptors. Proteins. 2014;82:727–743. doi: 10.1002/prot.24451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarek M., Tobias D.J. The dynamics of protein hydration water: a quantitative comparison of molecular dynamics simulations and neutron-scattering experiments. Biophys. J. 2000;79:3244–3257. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76557-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ball P. Water as an active constituent in cell biology. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:74–108. doi: 10.1021/cr068037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frauenfelder H., Chen G., Young R.D. A unified model of protein dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5129–5134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900336106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai A.M., Neumann D.A., Bell L.N. Molecular dynamics of solid-state lysozyme as affected by glycerol and water: a neutron scattering study. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2728–2732. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76511-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pal S.K., Peon J., Zewail A.H. Biological water at the protein surface: dynamical solvation probed directly with femtosecond resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1763–1768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042697899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jungwirth P. Biological water or rather water in biology? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:2449–2451. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallikarjunaiah K.J., Leftin A., Brown M.F. Solid-state ²H NMR shows equivalence of dehydration and osmotic pressures in lipid membrane deformation. Biophys. J. 2011;100:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan S., Filipek S., Vogel H. Activation of G-protein-coupled receptors correlates with the formation of a continuous internal water pathway. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4733. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan S., Vogel H., Filipek S. The role of water and sodium ions in the activation of the μ-opioid receptor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:10112–10115. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X., Ågren H., Tu Y. Functional water molecules in rhodopsin activation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:10863–10873. doi: 10.1021/jp505180t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burg J.S., Ingram J.R., Garcia K.C. Structural biology. Structural basis for chemokine recognition and activation of a viral G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2015;347:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leioatts N., Mertz B., Brown M.F. Retinal ligand mobility explains internal hydration and reconciles active rhodopsin structures. Biochemistry. 2014;53:376–385. doi: 10.1021/bi4013947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J.Y., Lyman E. Agonist dynamics and conformational selection during microsecond simulations of the A2A adenosine receptor. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2114–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan S., Hu Z., Vogel H. W2466.48 opens a gate for a continuous intrinsic water pathway during activation of the adenosine A2A receptor. Angew. Chem. 2015;127:566–569. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabbadin D., Ciancetta A., Moro S. Perturbation of fluid dynamics properties of water molecules during G protein-coupled receptor-ligand recognition: the human A2A adenosine receptor as a key study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014;54:2846–2855. doi: 10.1021/ci500397y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai Q., Pérez-Sánchez H., Yao X. Ligand induced change of β2 adrenergic receptor from active to inactive conformation and its implication for the closed/open state of the water channel: insight from molecular dynamics simulation, free energy calculation and Markov state model analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:15874–15885. doi: 10.1039/c4cp01185f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossfield A., Pitman M.C., Gawrisch K. Internal hydration increases during activation of the G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;381:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jardón-Valadez E., Bondar A.-N., Tobias D.J. Coupling of retinal, protein, and water dynamics in squid rhodopsin. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2200–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selent J., Sanz F., De Fabritiis G. Induced effects of sodium ions on dopaminergic G-protein coupled receptors. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W., Chun E., Stevens R.C. Structural basis for allosteric regulation of GPCRs by sodium ions. Science. 2012;337:232–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1219218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venkatakrishnan A.J., Deupi X., Babu M.M. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013;494:185–194. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavender U.S., Aravinda S., Balaram P. Characterization of water wires inside hydrophobic tubular peptide structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15130–15132. doi: 10.1021/ja9038906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy G., Straub J.E., Thirumalai D. Dry amyloid fibril assembly in a yeast prion peptide is mediated by long-lived structures containing water wires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21459–21464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008616107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thirumalai D., Reddy G., Straub J.E. Role of water in protein aggregation and amyloid polymorphism. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:83–92. doi: 10.1021/ar2000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu F., Wu H., Stevens R.C. Structure of an agonist-bound human A2A adenosine receptor. Science. 2011;332:322–327. doi: 10.1126/science.1202793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaakola V.P., Griffith M.T., Stevens R.C. The 2.6 Ångstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doré A.S., Robertson N., Marshall F.H. Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure. 2011;19:1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buck M., Bouguet-Bonnet S., MacKerell A.D., Jr. Importance of the CMAP correction to the CHARMM22 protein force field: dynamics of hen lysozyme. Biophys. J. 2006;90:L36–L38. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoete V., Cuendet M.A., Michielin O. SwissParam: a fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kučerka N., Nieh M.-P., Katsaras J. Fluid phase lipid areas and bilayer thicknesses of commonly used phosphatidylcholines as a function of temperature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:2761–2771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai H.-H.G., Lee J.-B., Juwita R. A molecular dynamics study of the structural and dynamical properties of putative arsenic substituted lipid bilayers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:7702–7715. doi: 10.3390/ijms14047702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luzar A., Chandler D. Hydrogen-bond kinetics in liquid water. Nature. 1996;379:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoon J., Lin J.-C., Thirumalai D. Dynamical transition and heterogeneous hydration dynamics in RNA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:7910–7919. doi: 10.1021/jp500643u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Freeman L. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Networks. 1979;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strogatz S.H. Exploring complex networks. Nature. 2001;410:268–276. doi: 10.1038/35065725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albert R., Jeong H., Barabási A.L. Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature. 2000;406:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35019019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newman M. A measure of betweenness centrality based on random walks. Soc. Networks. 2005;27:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greene L.H., Higman V.A. Uncovering network systems within protein structures. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:781–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amitai G., Shemesh A., Pietrokovski S. Network analysis of protein structures identifies functional residues. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:1135–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Del Sol A., Fujihashi H., Nussinov R. Residues crucial for maintaining short paths in network communication mediate signaling in proteins. Mol. Sys. Biol. 2006;2:2006.0019. doi: 10.1038/msb4100063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bagler G., Sinha S. Assortative mixing in protein contact networks and protein folding kinetics. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1760–1767. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vendruscolo M., Dokholyan N.V., Karplus M. Small-world view of the amino acids that play a key role in protein folding. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2002;65:061910. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.65.061910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dokholyan N.V., Li L., Shakhnovich E.I. Topological determinants of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8637–8641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122076099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brandes U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J. Math. Sociol. 2001;25:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franck J.M., Sokolovski M., Horovitz A. Probing water density and dynamics in the chaperonin GroEL cavity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9396–9403. doi: 10.1021/ja503501x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Franck J.M., Ding Y., Han S. Anomalously rapid hydration water diffusion dynamics near DNA surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12013–12023. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smart O.S., Neduvelil J.G., Sansom M.S. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. 376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J., Jonsson A.L., Voth G.A. Ligand-dependent activation and deactivation of the human adenosine A2A receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8749–8759. doi: 10.1021/ja404391q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aryal P., Abd-Wahab F., Tucker S.J. A hydrophobic barrier deep within the inner pore of the TWIK-1 K2P potassium channel. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4377. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anishkin A., Sukharev S. Water dynamics and dewetting transitions in the small mechanosensitive channel MscS. Biophys. J. 2004;86:2883–2895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74340-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Isom D.G., Dohlman H.G. Buried ionizable networks are an ancient hallmark of G protein-coupled receptor activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:5702–5707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417888112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aryal P., Sansom M.S., Tucker S.J. Hydrophobic gating in ion channels. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell M.R., Cleary L., Siwy Z.S. Electric-field-induced wetting and dewetting in single hydrophobic nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kobilka B.K., Deupi X. Conformational complexity of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hilser V.J., Wrabl J.O., Motlagh H.N. Structural and energetic basis of allostery. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2012;41:585–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Motlagh H.N., Wrabl J.O., Hilser V.J. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lockless S.W., Ranganathan R. Evolutionarily conserved pathways of energetic connectivity in protein families. Science. 1999;286:295–299. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halabi N., Rivoire O., Ranganathan R. Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure. Cell. 2009;138:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng W., Brooks B.R., Thirumalai D. Network of dynamically important residues in the open/closed transition in polymerases is strongly conserved. Structure. 2005;13:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ribeiro A.A., Ortiz V. Determination of signaling pathways in proteins through network theory: importance of the topology. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014;10:1762–1769. doi: 10.1021/ct400977r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feher V.A., Durrant J.D., Amaro R.E. Computational approaches to mapping allosteric pathways. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014;25:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Di Paola L., Giuliani A. Protein contact network topology: a natural language for allostery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015;31:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leitner D.M. Water-mediated energy dynamics in a homodimeric hemoglobin. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:4019–4027. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b02137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoon J., Thirumalai D., Hyeon C. Urea-induced denaturation of preQ1-riboswitch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12112–12121. doi: 10.1021/ja406019s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Réat V., Dunn R., Smith J.C. Solvent dependence of dynamic transitions in protein solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:9961–9966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.9961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fitter J., Lechner R.E., Dencher N.A. Internal molecular motions of bacteriorhodopsin: hydration-induced flexibility studied by quasielastic incoherent neutron scattering using oriented purple membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:7600–7605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

All the water oxygens are shown with small spheres in different colors. The key microswitch residues are depicted using the stick representation marked with their residue numbers.

The receptor structure is represented as white ribbon, and two water molecules that compete around are depicted using spheres in cyan and green.