Abstract

Introduction

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI) can be a challenging condition to manage. We describe the protocol design and rationale for the Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced with Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence (ESTEEM) trial, designed to compare a combined conservative and surgical treatment approach versus surgery alone for improving patient-centered MUI outcomes at 12 months.

Methods

ESTEEM is a multi-site, prospective, randomized trial of female participants with MUI randomized to a standardized perioperative behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention plus midurethral sling versus midurethral sling alone. We describe our methods and four challenges encountered during the design phase: defining the study population, selecting relevant patient-centered outcomes, determining sample size estimates using a patient-reported outcome measure, and designing an analysis plan that accommodates MUI failure rates. A central theme in the design was patient-centeredness, which guided many key decisions. Our primary outcome is patient-reported MUI symptoms measured using the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) score at 12 months. Secondary outcomes include quality of life, sexual function, cost-effectiveness, time to failure and need for additional treatment.

Results

The final study design was implemented in November 2013 across 8 clinical sites in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. As of February 27, 2016, 433 total /472 targeted participants have been randomized.

Conclusions

We describe the ESTEEM protocol and our methods for reaching consensus for methodological challenges in designing a trial for MUI by maintaining the patient perspective at the core of key decisions. This trial will provide information that can directly impact patient care and clinical decision-making.

Keywords: female, mixed urinary incontinence, clinical trials, sling, behavioral therapy, pelvic floor exercises

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common female condition with an estimated prevalence of 25-49%.1-3 The prevalence and number of women undergoing UI treatment are expected to increase with our aging population.4-6 Additionally, the number of women undergoing surgery for UI is estimated to increase by almost 50% by 2050.5 The personal and societal burden of female UI is substantial, including negative consequences on a woman's mental, physical and sexual health, work productivity, and quality of life.7-11

There are two major subtypes of UI. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is defined as involuntary loss of urine on effort or exertion, sneezing or coughing.12 Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) is typically part of overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome, defined as “urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence”.12 Although mechanisms for each subtype may include multiple factors, SUI is generally considered to be due to weakening support to the urethra and surgery is often used for treatment. UUI is thought to be a result of involuntary detrusor muscle contractions, although many women with UUI do not demonstrate detrusor overactivity on urodynamic testing.13 Primary treatments for UUI are typically behavioral and/or medical.

Up to 50% of women with UI suffer from a mixture of both SUI and UUI, or mixed UI (MUI), a complex and challenging condition for patients, clinicians and researchers.2, 14, 15 For patients, MUI is more bothersome than either SUI or UUI alone.16-18 For both patients and clinicians, management is challenging because most existing interventions are designed to benefit only one of the conditions and typically do not benefit the other. For clinicians and researchers, the lack of a clinically useful definition,19 the frequent exclusion of MUI patients from trials,20 and the fact that MUI includes two separate symptom components pose challenges for determining best treatment approaches. These controversies and lack of guidelines for MUI have recently been highlighted.21

Several assumptions have dominated the management of MUI:

Assumption 1: The primary MUI treatment strategy should focus on the most bothersome component (SUI versus UUI). In line with this, previous MUI studies have also segregated outcomes and defined “success” as either SUI or UUI improvement, but often do not incorporate both components. One limitation of this approach is that from the patient perspective, improvement in only one condition is often considered a failure if she still suffers from the other. Furthermore, patients may not always be able to determine which condition is more bothersome.

Assumption 2: SUI surgery should not be performed in women with MUI because it will worsen UUI and urgency. This is mainly supported by retrospective studies of older surgical approaches including pubovaginal slings.22 In the 1990's, the less obstructive midurethral sling was introduced as an effective SUI treatment.23 Several recent studies show that OAB with UUI symptoms may actually improve in 30-85% after midurethral sling.24-28 In practice, many surgeons still consider MUI to be a relative contraindication whereas others are comfortable offering the midurethral sling. Counseling these women about expectations remains challenging because clinical trial and outcome data for MUI are limited.

Dilemmas in studying the MUI population include lack of a clinically useful definition of the condition, historical use of non-patient-centered outcomes in studies, and sparse data on how to optimize treatment outcomes. In 2009, Brubaker et al published on their experience with the “Mixed Incontinence: Medical or Surgical Approach” (MIMOSA) study, a pragmatic trial designed to measure the effectiveness of treatments in routine clinical practice. MIMOSA randomized women with MUI to nonsurgical versus surgical treatment.29 After 4 months of enrollment, the study was terminated after only 27/1190 screened women were randomized. The investigators attributed low recruitment to the divergent treatments and overestimation of the study population based on their MUI definition and eligibility criteria. The MIMOSA study highlights the difficulty in studying this population.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network designed the Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced with Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence (ESTEEM) trial to address knowledge gaps in MUI. At the core of study development was the patient perspective, which guided numerous decisions when evidence was lacking or when traditional approaches did not seem patient-centered.11

The purpose of this paper is three-fold. Firstly, given the challenges and controversies surrounding the clinical care and research of the MUI population, we discuss the process and rationale for key design features of ESTEEM including determining eligibility, defining MUI, selecting patient-important outcomes, quality assurance, and identifying challenges encountered during trial design and implementation. Secondly, ESTEEM represents one of the few surgical trials for UI that uses a patient reported outcome (PRO) measure as the primary outcome. Patient-centered research is increasingly recognized as important for clinical decision-making and informing health policy. Special considerations for ensuring transparency, accurate interpretation, and relevance of study results when using a PRO measure are discussed which can benefit researchers conducting patient-centered research. Finally, this methods paper may serve as a reference when the trial has been completed for readers desiring additional information. We hope this information will be useful for clinicians and researchers who care for women with MUI.

Materials and Methods

A. Overall design

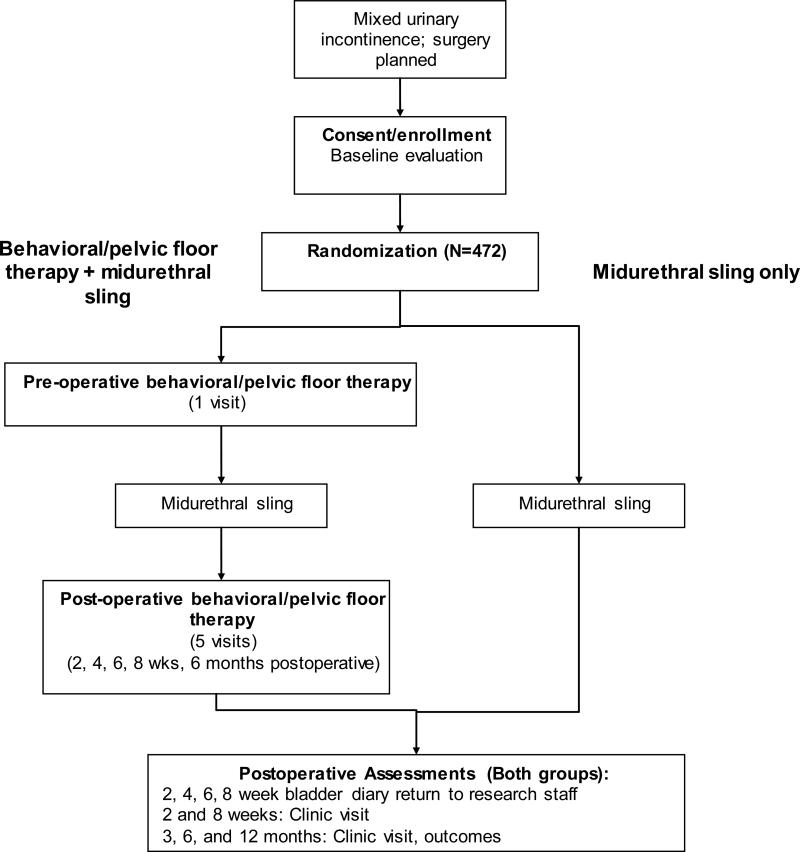

ESTEEM is a randomized controlled trial designed to assess whether combined midurethral sling plus a peri-operative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle exercise intervention is superior to midurethral sling alone for improving female MUI symptoms 12 months later. The flow of participants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

ESTEEM Participant Flow

The study aims of ESTEEM are as follows:

- Primary Aim:

- To assess whether combined midurethral sling + peri-operative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle therapy is superior to midurethral sling alone for improving MUI symptoms at 1 year in women electing surgical treatment.

- Secondary Aims:

- OAB symptom outcomes: To assess whether combined midurethral sling + peri-operative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle is superior to midurethral sling alone for improving change in OAB symptoms at 1 year in women electing surgical treatment.

- SUI symptom outcomes: To assess whether combined midurethral sling + peri-operative behavioral/pelvic floor muscle is superior to midurethral sling alone for improving change in SUI symptoms at 1 year in women electing surgical treatment for MUI.

B. Study population

The study population of interest includes women with at least moderately bothersome SUI and UUI symptoms for whom it is unclear whether a midurethral sling will result in improvement, no change, or worsening of UUI/OAB. The team wanted to avoid overly strict inclusion criteria, but assure a study population with bothersome MUI symptoms. Instruments that can clearly segregate SUI from UUI symptoms and predict clinical outcomes for MUI do not currently exist.30 Therefore, defining our inclusion criteria was a critical process. Trials for SUI typically use a subjective report of SUI in combination with a positive cough stress test on examination31 for inclusion whereas UUI trials often use bladder diaries to document the condition. Invasive urodynamic testing has not been shown to predict treatment outcomes for SUI32-35 or UUI36,37 and thus the team reached consensus that urodynamic evaluation (UDE) findings would not be a part of inclusion criteria. However, preoperative UDE results will be collected on all participants to be used in secondary analyses to identify potential predictors of improvement or worsening of urinary outcomes after treatment.

The team agreed that using a combination of symptoms and objective documentation of both conditions would be ideal. Because no single measure provides subjective and objective documentation of both conditions, the investigators agreed on a combined study definition of MUI: 1) symptom documentation of at least moderately bothersome SUI and UUI measured by two items on the Urogenital Distress Inventory9 (UDI, described below); 2) objective documentation of both SUI and UUI on a 3-day bladder diary; and 3) objective documentation of SUI on clinical examination (either cough stress test or urodynamic testing). Participants must desire surgical treatment of their SUI. See Table 1 for criteria.

Table 1.

ESTEEM inclusion/exclusion criteria*

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1) Presence of both SUI and UUI on bladder diary; and ≥ 2 incontinence episodes/3 days |

| a) ≥ 1 SUI episode/3 day diary |

| b) ≥ 1 UUI episode/3 day diary |

| 2) Reporting at least “moderate bother” from UUI item on Urogenital Distress Inventory |

| “Do you usually experience urine leakage associated with a feeling of urgency, that is a strong sensation of needing to go to the bathroom?” |

| 3) Reporting at least “moderate bother” from SUI item on Urogenital Distress Inventory |

| “Do you usually experience urine leakage related to coughing, sneezing, or laughing” |

| 4) Diagnosis of SUI defined by a positive cough stress test or urodynamic testing within the past 18 months |

| 5) Desires surgical treatment for SUI symptoms |

| 6) Urinary symptoms ≥3 months |

| 7) Subjects understand that behavioral/pelvic floor muscle therapy is a treatment option for MUI outside of current study protocol |

| 8) Urodynamics within past 18 months (for secondary analyses only) |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1) Anterior or apical compartment prolapse at or beyond the hymen, regardless if patient is symptomatic |

| a) Women with anterior or apical prolapse above the hymen who do not report vaginal bulge symptoms will be eligible |

| 2) Planned concomitant surgery for anterior vaginal wall or apical prolapse |

| a) Women undergoing only rectocele repair or other repair unrelated to anterior or apical compartment (i.e.: anal sphincter repair) are eligible |

| 3) Women undergoing hysterectomy for any indication will be excluded |

| 4) Active pelvic organ malignancy |

| 5) Age <21 years |

| 6) Pregnant or plans for future pregnancy in next 12 months, or within 12 months post-partum |

| 7) Post-void residual >150 milliliters on 2 occasions within the past 6 months, or current catheter use |

| 8) Participation in other trial that may influence results of this study |

| 9) Unevaluated hematuria |

| 10) Prior sling, synthetic mesh for prolapse, implanted nerve stimulator for incontinence |

| 11) Spinal cord injury or advanced/severe neurologic conditions including Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson's Disease |

| 12) Women on overactive bladder medication/therapy will be eligible after 3 week wash-out period |

| 13) Non-ambulatory |

| 14) History of serious adverse reaction to synthetic mesh |

| 15) Not able to complete study assessments per clinician judgment, or not available for 12 month follow-up |

| 16) Women who only report “don't know” for urine leakage type on bladder diary, and do not report at minimum 1 SUI and 1 UUI episode over 3 days |

| 17) Diagnosis of and/or history of bladder pain or chronic pelvic pain |

| 18) Women who had intravesical botulinum injection within the past 12 months |

| 19) Women who have undergone anterior or apical pelvic organ prolapse repair within the past 6 months |

SUI = Stress urinary incontinence. UUI = Urgency urinary incontinence. MUI = Mixed urinary incontinence

C. Study procedures

Three types of midurethral slings were selected for use in ESTEEM based on previous trials demonstrating equivalence, including the Tension-free Vaginal Tape-retropubic™ (TVT, Gynecare), TVT-obturator (Gynecare), and the Monarc™ transobturator sling (American Medical Systems).25, 27 Certified surgeons participating in the trial must have performed a minimum of 20 midurethral slings.

The participant is randomized only after she is determined to be eligible based on the UDI and diary criteria, completes all baseline assessments, and has a scheduled date for midurethral sling surgery within 91 days of completing the UDI and diary. Randomization is generated by computer through the data coordinating center. Once the required elements are keyed into the data center, an unmasked research staff member at the site receives the randomization assignment and schedules study and interventionist appointments as appropriate (please see below for more details about masked and unmasked personnel in this study). Randomization is in 1:1 allocation, stratified by the 8 clinical sites and UUI severity. The rationale for stratification by UUI severity was based on a previous trial demonstrating that women with > 10 UUI episodes in 7 days (or ~ 4 episodes on a 3 day diary) were less likely to achieve continence after behavioral intervention.38

D. Behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention design and quality control

Currently there is conflicting evidence about the “ideal” conservative treatment for MUI. Pelvic floor muscle exercises are frequently recommended for SUI treatment and are designed to enhance urethral closure through strengthening and improved coordination. A Cochrane review concluded that pelvic floor muscle exercise was effective for both SUI and MUI, but women with pure SUI have better outcomes.39 Although pelvic floor muscle exercises are included in UUI treatment, bladder training and strategies to promote skills and behaviors that encourage continence are also critical.13, 40

We developed a standardized, combined behavioral/pelvic floor exercise intervention in ESTEEM based on the best available evidence for components focused on SUI and UUI/OAB. When evidence was lacking, design decisions were based on logical and pragmatic rationale with a focus on developing a reproducible protocol. Details about the methods for intervention development will be published separately, but we provide a brief description here. The intervention includes: 1) pelvic floor muscle training; 2) bladder training and delayed voiding techniques; 3) urgency suppression; and 4) SUI strategies (eg, “knack”).40, 41 Based on previous work42-45 we were aware of the potential challenges for standardization of this type of intervention and ensuring consistency across multiple sites. For example, one requirement was for interventionists to be experienced pelvic floor nurses, nurse practitioners, or physical therapists trained and certified by ESTEEM experts. Although this helps to ensure high experience and quality, it could lead to inconsistencies if individual interventionists added strategies that are successful in their clinical practices but are not included in ESTEEM due to lack of evidence. To ensure consistency, the team developed an a priori quality control plan including audits of intervention audio recordings and a list of protocol deviations, which includes the addition and/or omission of specific intervention content. To our knowledge this is one of the first trials to define and assess deviations for this type of intervention. Other methods to improve standardization and quality are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methods to enhance standardization and quality of ESTEEM intervention

| • Certification of all interventionists through passing of e-learning modules and attendance and demonstration of hands-on skills at an, in-person interventionist training session. |

| • Demonstration of ability to perform pelvic floor muscle assessment. |

| • Required completion of an interventionist checklist during each visit to ensure the same components have been performed across subjects. |

| • Development of a protocol for determining voiding patterns and prescribing new voiding intervals. |

| • Development of a detailed protocol for the pelvic floor muscle exercise progression |

| • Development of a detailed protocol for “special circumstances” for when the standard pelvic floor muscle exercise progression protocol cannot be followed (i.e.: weak muscle) that the interventionist is trained to follow |

| • Subject handouts for the 4 components (pelvic floor muscle training, urge strategies, stress strategies, and bladder training with delayed voiding techniques) - the interventionists will be required to refer only to these handouts during the education component to ensure that additional information outside of the intervention protocol is not provided. |

| • All intervention sessions will be audiotaped and will be randomly selected for auditing by protocol/intervention experts to ensure adherence to protocol. |

| -A detailed list of intervention protocol deviations was developed and provided to interventionists |

| -Protocol deviations identified through auditing will be recorded and entered |

| -Protocol deviations identified through auditing will be reviewed with the interventionist |

Previous studies have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with perioperative physical therapy, including post-prostatectomy SUI prevention in males.46-48 Another study of UUI patients demonstrated that combined behavioral and drug therapy yielded better outcomes compared to drug alone.44 The ESTEEM behavioral/pelvic floor intervention was designed as a combined peri-operative treatment including one preoperative visit and five post-operative visits at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks and 6 months postoperative.49 To help differentiate the contributions between the pelvic floor muscle strengthening versus behavioral therapy components, pelvic floor muscle strength is measured using the Peritron™ perineometer (Laborie, Williston, VT) and will be included in exploratory analyses.

E. Measurement, follow-up, and masking

Participants undergo assessments at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively. Additional treatment for any urinary symptom is not permitted in the first 3 months of surgical recovery.

It is not feasible to mask participants or interventionists due to the nature of the behavioral/pelvic floor intervention. Based on expert interventionist opinion, the team rejected “sham” intervention visits because they present design difficulties and often are not convincing. In order to minimize potential bias, there is strict delegation of masked and unmasked study personnel. Unmasked roles include: study participant, data entry staff for unmasked data entry, interventionists, data coordinating center study coordinator and data managers, and a study statistician. Masked roles include: study surgeon, research staff administering questionnaires to participants, data entry staff to key in data for masked data, any clinical staff or coordinators performing pelvic floor measurements, and the study's senior statistician. All PRO measures are administered prior to clinical assessments to minimize any bias that may occur due to clinical findings. All study and interventionist visits are coordinated by unmasked research staff.

F. Primary outcome selection and rationale for using a patient reported outcome measure

Currently there is no “objective” gold standard for measuring MUI severity or clinically meaningful disease markers that can be measured by a clinician, observer, or laboratory. Unlike other conditions, the severity of UI is dependent primarily on the patient perspective. Physical examination, urodynamic testing, and bladder diary do not always correspond to patient perceptions of impact or treatment benefit, and can yield biased “success rates”.50, 51 MUI treatments are aimed at improving symptoms and quality of life and the investigators reached consensus that a PRO measure would best capture outcomes from the patient perspective. Furthermore, in clinical trials PRO instruments are increasingly being considered as primary outcomes and their use is supported by federal agencies.52

The long form of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) was selected as the primary outcome based on its domain coverage and validity properties.9 It is a self-administered, 19 item questionnaire that measures 3 urinary symptom domains: 1) irritative symptoms (OAB/UUI); 2) SUI; and 3) obstructive symptoms.9 The three subscale scores are summed to provide a UDI-total score ranging from 0-300 with higher scores representing more severe symptoms and bother. The UDI demonstrates significant correlation with the number of UI episodes on diary and pad weight tests (construct validity), clinical diagnoses (criterion validity), can discriminate between known UI subgroups, and is responsive to change with published minimally important difference (MID) estimates.53, 54 These are some minimum qualities needed for valid interpretation of a PRO measure in a clinical trial. Additional scoring information for the UDI can be found in the original publication.9

Using the total UDI score as the primary outcome accomplishes several goals. It comprehensively captures the presence and bother from all MUI symptom components and can separately characterize improvement, worsening, or no change in these components from the patient perspective. Unlike previous studies, this important aspect will help address the historical assumption that a sling may improve SUI but worsen UUI.

The team considered, but did not select, other primary outcome measures. The bladder diary, which can measure voiding frequency and number of incontinence episodes, is a commonly used measure. It may not, however, capture what is meaningful to patients, and statistically significant reductions in incontinence episodes are not always clinically relevant.55 A patient's overall/global impression of improvement, measured with the Patient Global Impression of Improvement,56 is subject to bias in non-masked trials. Participants randomized to the midurethral sling-only group could potentially be influenced by the knowledge that they did not receive the additional intervention. If this causes them to be less likely to report improvement, the combined intervention would falsely appear more effective. Overactive bladder questionnaires often omit SUI symptoms and would be incomplete in capturing MUI. Generic quality of life questionnaires are not as responsive to change for UI treatments.57 The team reached consensus based on several phone and in-person conferences over the course of protocol development which took over 15 months. We did not use focus groups or surveys to reach consensus.

Secondary outcomes in ESTEEM include SUI and UUI/OAB symptoms analyzed separately, bladder diary, pelvic floor muscle strength, quality of life and cost-effectiveness analyses (see Table 3 for complete list). Additional exploratory studies will include evaluation of the urinary and vaginal microbiomes and goal attainment.

Table 3.

ESTEEM outcomes*

G. Sample size: considerations when using a PRO measure and anticipating requests for additional treatment

Our primary outcome is MUI symptoms measured by the UDI-total score. One consideration when using a PRO measure is to ensure that the sample size calculation is relevant based on clinical rationale and meaningfulness to patients.58 The minimum important difference (MID) of a measure is a score change that reflects a clinically meaningful response to treatment and represents the change in score that needs to be met or exceeded for treatment effects to be considered clinically meaningful to patients. The MID represents the magnitude of benefit for which trials should be powered to minimize type 1 and type 2 errors: MIDs have been previously published for the UDI.53, 54 In considering the results of ESTEEM, we would only recommend the combination of midurethral sling and behavioral therapy over midurethral sling alone if the improvement with additional behavioral therapy was of a magnitude that patients would consider important. Thus, we used the published MIDs as estimates of that meaningful difference.

For the UDI, a reduction in score (negative change) represents improvement, but for simplicity we report the absolute value of the MIDs here. Based on a UUI-predominant MUI population undergoing UUI treatment, Dyer et al recommend an MID for the UDI-total score of 35 points and an MID of 15 points for the UDI-irritative subscale.53 For a SUI-predominant population undergoing conservative SUI treatment, Barber et al recommend an MID of 11 points for the UDI-total score and an MID of 8 points for the UDI–SUI subscale based on a modified UDI.54 These are the available estimates most applicable to our study population.53,54 Because all women in ESTEEM have UUI, the ESTEEM population is likely more similar to the Dyer population. They have also selected SUI surgery, and thus, it is likely that the MID for the ESTEEM population will be smaller than 35 but unlikely that it would be smaller than 11. Because the UDI-SUI and UDI-irritative subscales are important secondary outcomes, we powered the study to detect between-group differences at least as small as the published MIDs for the UDI-total, -SUI, and -irritative subscales.19

Because MUI is more challenging to treat compared to SUI or UUI alone, we anticipated that some participants would request additional treatment outside of the study prior to 12 months. However, our interest was in estimating the effect of the study treatments in the absence of additional treatment; thus, our sample size and analysis plans were designed to achieve that goal. The rate of additional treatment for residual UUI/OAB symptoms in previous trials after midurethral sling is 4-25%. 25, 27, 59 To be conservative, we assumed that 30% of women in the midurethral sling only group and 20% in the combined behavioral/pelvic floor intervention group would request additional UUI/OAB treatment. We assumed those participants who start additional treatment would have smaller improvements from baseline in their UDI scores at the time of requesting additional treatment, and that these score changes would be similar for all participants requesting additional treatment regardless of intervention assignment. All outcome measures will be collected before additional treatment is started, and these data will be included in the statistical model used for our primary analyses. We will exclude (consider informatively missing) UDI scores collected after additional treatment is initiated because we would expect additional treatment to improve follow-up scores, which would bias the study results. See Analysis plan below for more information on how these data will be managed.

Simulated data that incorporated our assumptions about participants requesting additional treatment were used to produce power and sample size estimates. Power was estimated based on the proportion of simulated data sets for which the null hypothesis, that the changes from baseline in UDI scores at 12 months were the same in the two treatment groups, was rejected at the p < 0.05 level using the analysis approach planned for the primary analysis.

For the UDI-total score, 75 women per group would provide at least 90% power to detect a statistically significant difference between groups as small as 35 in mean change from baseline in UDI-total scores at 12 months assuming a standard deviation of 50.4.53 For the UDI-irritative score, 92 women per group would provide 90% power to detect a difference as small at 15 points assuming an SD of 25.6,53 and for the UDI-stress score, 200 women per group would provide 90% power to detect a difference as small as 8 points assuming an SD of 21.5.24

Using 200 per group as our base estimate and adjusting for 15% dropout results in a total sample size of 472 randomized to treatment. Because we have elected to use the highest of the three sample estimates, our study will have 90% power to detect a statistically significant difference in UDI-total scores if the true difference between groups is as small as 19 points, and 80% power to detect a difference if the true difference is as small as 16.5 points. These differences are in a range of what we think may be clinically important given the differences between the ESTEEM population and those on which the published MID was based. If a between-group difference smaller than 35 is found to be statistically significant, the primary publication will discuss the extent to which the observed difference is thought to be clinically meaningful. A secondary aim of the study is to explore whether the MIDs for the UDI scores differ in this MUI population from what has been previously published. We will also describe the distribution of responses in both treatment groups to assess the percent of patients experiencing a meaningful change in score between baseline and 12 months.52

H. Analysis considerations

The primary analysis will estimate the effect of midurethral sling surgery with versus without behavioral/pelvic floor intervention in the absence of additional treatment. However, if a participant does request additional treatment, her outcome data up to the time of additional treatment will be included in the model used for analysis as described below. The primary analysis will be based on a general linear mixed model (GLMM) to predict change from baseline in UDI scores using data from all follow up time points up to 12 months following surgery. Participants requesting additional treatment for any lower urinary tract symptoms (SUI, UUI/OAB, voiding dysfunction) before 12 months will be asked to complete all primary and secondary outcome measures at an additional time point prior to starting additional treatment. We anticipate that these women will have worse outcome trajectories compared to women who do not have additional treatment, and that those trajectories will be reflected in the outcome data collected before starting additional treatment. UDI measurements after the time of additional treatment will be considered informatively missing, so as not to bias the model results as previously discussed. A GLMM model allows missing outcome data to be dependent on predictors in the model (in this case, additional treatment); thus, our model will include fixed effects for intervention group, additional treatment, time, and interactions between those variables, in order to model separate trajectories (slopes) for the outcomes of participants in each intervention group who do and do not undergo additional treatment. The model will also be adjusted for the design effects of stratification by center and by baseline UUI, and it will account for the lack of independence between repeated measures on the same participant by modeling the within-participant covariance structure. The test to compare mean changes from baseline in UDI scores at 12 months between intervention groups will be constructed based on the average predicted responses of participants who do and do not request additional treatment within each intervention group weighted by the percent of women in each of those subgroups. Sensitivity analysis will be conducted to test the robustness of results to model specifications and assumptions. Regression models will be created to identify predictors of change for UDI-total and subscale scores.

Results to date

All 8 clinical sites received local Institutional Review Board approval. Study recruitment began in November 2013 and 433 total women out of a targeted 472 women (92%) have been randomized (February 27, 2016). Recruitment was anticipated for 24 months but we now project 30 months. Recruitment challenges have included inability to document SUI on diary despite patient reporting SUI symptoms and participants being unable to commit to the intervention visits. Some sites reported surgeon concern about performing sling procedures on women with MUI, supporting that surgical treatment of this population remains controversial. Some sites have found a higher than anticipated prevalence of previous transvaginal mesh placement, including previous midurethral slings, which excluded potential participants.

Discussion

Patients with MUI who elect treatment are often hopeful that their overall urinary condition will improve. However, most treatments are designed to improve either SUI or UUI only, leading to high patient dissatisfaction. ESTEEM will address several knowledge gaps. First, it is the first trial to evaluate the combined approach of conservative and surgical treatment for MUI. It will also provide data to guide counseling about midurethral sling outcomes in MUI. Finally, we will gain important predictive information for patients undergoing midurethral sling. The unique features of the ESTEEM trial design compared to previous UI studies are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

Distinction of ESTEEM trial design compared to previous urinary incontinence trials*

| Previous trials | ESTEEM trial | Advantages of ESTEEM design | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study population | 1. Stress-predominant MUI or stress incontinence only 2. Urgency-predominant MUI or urgency incontinence only |

Mixed urinary incontinence with both bothersome SUI and UUI | Focus is on MUI population without requirement to have predominant symptoms or bother of either SUI or UUI |

| Primary outcome measures used in previous urinary incontinence trials | 1. Bladder diary 2. Urodynamic test 3. Single item measuring incontinence presence or bother (either SUI or UUI) 4. Composite outcome combining diary and single item incontinence questions |

Patient-reported outcome measure (Urogenital distress inventory) | 1. Powered using minimal important difference estimates to ensure relevance to patients 2. Avoids problems associated with diary use in the mixed urinary incontinence population (described in Lessons Learned) |

| Primary outcome measures used in previous mixed urinary incontinence trials | 1. Focus on either SUI or UUI symptoms only Mixed urinary incontinence population frequently relegated to a sub-analysis and underpowered |

1. UDI will measure MUI symptoms without having to focus only on SUI or UUI 2. Study is also powered to detect differences between stress incontinence and urgency incontinence separately |

1. Comprehensively captures all relevant symptom components of MUI 2. Will capture MUI as a whole but can also determine whether each separate condition improves, worsens, or stays the same after treatment |

| Behavioral/pelvic floor muscle therapy intervention | Development and implementation of quality control plan | Ensures higher quality and consistency of intervention delivered |

SUI = stress urinary incontinence; UUI = urgency urinary incontinence; MUI = mixed urinary incontinence

Although the trial is still ongoing, there have been some lessons learned. Although the diary is not our primary outcome, it is part of our inclusion criteria and secondary outcomes because of its common use. In the design phase, the team anticipated it may be difficult for women with MUI to distinguish leakage episodes as either SUI or UUI on a diary. In anticipation of this problem the ESTEEM diary included a classification option of “Don't know”. From an eligibility standpoint, adding this option excludes women who are not able to classify their leakage but nonetheless have MUI. This also presents challenges from a quality control standpoint. We have learned that it is both difficult and inappropriate for a third party to re-categorize UI episodes because it ultimately depends on the patient's experience. For example, UI associated with jumping is typically a SUI episode but it is possible that the patient experienced urgency at that time and marked an UUI episode. Therefore, coordinators have been trained to try to resolve any ambiguities with the bladder diary by eliciting additional information from the participant at the time of the visit.

The development of ESTEEM challenged the investigators to critically re-evaluate historical outcomes and definitions used for MUI, comprehensively review the literature as presented in this paper, and to maintain the patient perspective as the central focus. We reviewed in detail the outcomes and eligibility criteria used in previous urinary incontinence trials and the special considerations to ensure valid . and accessible reporting as recommended by International Society of Quality of Life Research and CONSORT-Patient-Reported Outcomes extension standards when using a patient-reported outcome as the primary outcome.58, 60 This helps to ensure that results from ESTEEM will be relevant from the patient perspective. At the conclusion of this study, we expect to understand whether a combined conservative/surgical treatment approach is superior to surgery alone and will, hopefully, have predictive information that will be directly applicable to the clinical care and decision-making of patients with MUI.

Summary.

We describe the design of the ESTEEM trial, a randomized trial comparing combined conservative and surgical treatment versus surgery alone for improving mixed urinary incontinence outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Alex Lynch for her technical expertise and Dr. Deborah Myers for her content expertise in the development and implementation phases of this study.

Funding:

Supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U10 HD041261, U10 HD069013, U10 HD054214, U10 HD054215, U10 HD041267, U10 HD069025, U10 HD069010, U10 HD069006, U01 HD069031) and the National Institutes of Health Office of Research on Women's Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Vivian W. Sung None

Diane Borello-France None

Gena Dunivan Pelvalon: Research funding

Marie Gantz None

Emily S. Lukacz Renew Medical, Inc: Research : 2010-2011; Consultant 2012-2015 for study of anal insert for accidental bowel leakage.

Pfizer: Study drug donated for trial on prevention of urinary tract infections.

AMS/Astora: Consultant: clinical events committee member for prolapse study, TOPAS sling for accidental bowel leakage.

Boston Scientific: Research funding for observational study of native tissue vaginal prolapse surgery

Uroplasty: Research funding for observational study of Macroplastique for intrinsic sphincter deficiency

Axonics: Consultant for development of neuromodulation technology

Grants: American Urogynecologic Society fellow research award: 2013 funding for study of prevention of urinary tract infection.

UpToDate – Royalties for chapters on urinary incontinence and perioperative management

NIH/NIDDK: Honoraria and travel for scientific consulting and Principal Investigator in the PLUS (Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) network

Pamela Moalli ACell-Unrestricted Corporate Research Agreement

Diane K. Newman Research support: VA, NIH, Wellspect

Holly Richter Research Grants:

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases K24 Midcareer Award in Patient Oriented Pelvic Floor Research

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development - Pelvic Floor Disorders Network

National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases/National Institute of Health/Dept of Health and Human Services Washington University/National Institutes of Health Pelvalon, Inc

Consultant: Kimberly Clarke, Astellas and Pelvalon, Inc

Royalties: UpToDate

Beri Ridgeway None

Ariana L. Smith None

Alison C. Weidner None

Susan Meikle None

Author Contributions:

Sung, Vivian W. Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Borello-France, Diane Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing

Dunivan, Gena Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Gantz, Marie Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing

Lukacz, Emily S. Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Moalli, Pamela Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Newman, Diane K. Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing

Richter, Holly Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Ridgeway, Beri Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing

Smith, Ariana L. Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Weidner, Alison C. Protocol/project development, data collection, manuscript writing/editing

Meikle, Susan Protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing

References

- 1.Dooley Y, Kenton K, Cao G, et al. Urinary incontinence prevalence: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2008;179:656–61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, Newton K. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:537–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung VW, Raker CA, Myers DL, Clark MA. Ambulatory care related to female pelvic floor disorders in the United States, 1995-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:508, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:230, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1278–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Kelleher CJ, Milsom I. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers RG, Kammerer-Doak D, Villarreal A, Coates K, Qualls C. A new instrument to measure sexual function in women with urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:552–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009;103(Suppl 3):4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung VW, Marques F, Rogers RR, Williams DA, Myers DL, Clark MA. Content validation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) framework in women with urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:503–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.21048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(1):5–26. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kammerer-Doak D, Rizk DE, Sorinola O, Agur W, Ismail S, Bazi T. Mixed urinary incontinence: international urogynecological association research and development committee opinion. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:1303–12. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karram MM, Bhatia NN. Management of coexistent stress and urge urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:4–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–36. doi: 10.1007/s00345-002-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monz B, Chartier-Kastler E, Hampel C, et al. Patient characteristics associated with quality of life in European women seeking treatment for urinary incontinence: results from PURE. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1073–81. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.022. discussion 81-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dooley Y, Lowenstein L, Kenton K, FitzGerald M, Brubaker L. Mixed incontinence is more bothersome than pure incontinence subtypes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1359–62. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0637-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subak LL, Brubaker L, Chai TC, et al. High costs of urinary incontinence among women electing surgery to treat stress incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:899–907. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816a1e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brubaker L, Stoddard A, Richter H, et al. Mixed incontinence: comparing definitions in women having stress incontinence surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28:268–73. doi: 10.1002/nau.20698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dmochowski R, Staskin D. Mixed incontinence: definitions, outcomes, and interventions. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15:374–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000183946.96411.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers DL. Female mixed urinary incontinence: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:2007–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsumi HK, Rutman MP. Can we predict if overactive bladder symptoms will resolve after sling surgery in women with mixed urinary incontinence? Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:328–37. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulmsten U, Falconer C, Johnson P, et al. A multicenter study of tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1998;9:210–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01901606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 22:923–32. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2066–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Risk factors associated with failure 1 year after retropubic or transobturator midurethral slings. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:666, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:611–21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318162f22e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palva K, Nilsson CG. Prevalence of urinary urgency symptoms decreases by mid-urethral sling procedures for treatment of stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1241–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brubaker L, Moalli P, Richter HE, et al. Challenges in designing a pragmatic clinical trial: the mixed incontinence -- medical or surgical approach (MIMOSA) trial experience. Clin Trials. 2009;6:355–64. doi: 10.1177/1740774509339239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brubaker L, Lukacz ES, Burgio K, et al. Mixed incontinence: comparing definitions in non-surgical patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:47–51. doi: 10.1002/nau.20922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swift SE, Yoon EA. Test-retest reliability of the cough stress test in the evaluation of urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bosch JL, Cardozo L, Hashim H, Hilton P, Oelke M, Robinson D. Constructing trials to show whether urodynamic studies are necessary in lower urinary tract dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:735–40. doi: 10.1002/nau.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nager CW, Brubaker L, Daneshgari F, et al. Design of the Value of Urodynamic Evaluation (ValUE) trial: A non-inferiority randomized trial of preoperative urodynamic i nvestigations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:531–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nager CW, Kraus SR, Kenton K, et al. Urodynamics, the supine empty bladder stress test, and incontinence severity. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:1306–11. doi: 10.1002/nau.20836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nager CW, Brubaker L, Litman HJ, et al. A randomized trial of urodynamic testing before stress-incontinence surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1987–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashim H, Abrams P. Is the bladder a reliable witness for predicting detrusor overactivity? J Urol. 2006;175:191–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00067-4. discussion 94-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rovner ES, Goudelocke CM. Urodynamics in the evaluation of overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11:343–7. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al. Predictors of outcome in the behavioral treatment of urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:940–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumoulin C, Hay-Smith J. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD005654. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005654.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgio KL. Update on behavioral and physical therapies for incontinence and overactive bladder: the role of pelvic floor muscle training. Curr Urol Rep. 2013;14:457–64. doi: 10.1007/s11934-013-0358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller JM, Sampselle C, Ashton-Miller J, Hong GR, DeLancey JO. Clarification and confirmation of the Knack maneuver: the effect of volitional pelvic floor muscle contraction to preempt expected stress incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:773–82. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0525-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609–17. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d055d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burgio KL, Goode PS, Locher JL, et al. Behavioral training with and without biofeedback in the treatment of urge incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2293–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgio KL, Kraus SR, Menefee S, et al. Behavioral therapy to enable women with urge incontinence to discontinue drug treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:161–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1023–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Husby VS, Helgerud J, Bjorgen S, Husby OS, Benum P, Hoff J. Early postoperative maximal strength training improves work efficiency 6-12 months after osteoarthritis-induced total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 60 years. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:304–14. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181cf5623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel MI, Yao J, Hirschhorn AD, Mungovan SF. Preoperative pelvic floor physiotherapy improves continence after radical retropubic prostatectomy. International journal of urology : official journal of the Japanese urological Association. 2013;20:986–92. doi: 10.1111/iju.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tienforti D, Sacco E, Marangi F, et al. Efficacy of an assisted low-intensity programme of perioperative pelvic floor muscle training in improving the recovery of continence after radical prostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2012;110:1004–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Goode PS, et al. Adherence to behavioral interventions for urge incontinence when combined with drug therapy: adherence rates, barriers, and predictors. Phys Ther. 2013;90:1493–505. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:213–40. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staskin D, Tubaro A, Norton PA, Ashton-Miller JA. Mechanisms of continence and surgical cure in female and male SUI: surgical research initiatives. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:704–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. [June 1, 2015];Guidance for Industry Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Dyer KY, Xu Y, Brubaker L, et al. Minimum important difference for validated instruments in women with urge incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 30:1319–24. doi: 10.1002/nau.21028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barber MD, Spino C, Janz NK, et al. The minimum important differences for the urinary scales of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:580, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lowenstein L, Kenton K, FitzGerald MP, Brubaker L. Clinically useful measures in women with mixed urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:664, e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.014. discussion 64 e3-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:98–101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halme AS, Fritel X, Benedetti A, Eng K, Tannenbaum C. Implications of the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for Health-Related Quality-of-Life Outcomes: A Comparison of Sample Size Requirements for an Incontinence Treatment Trial. Value Health. 2015;18:292–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brundage M, Blazeby J, Revicki D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1161–75. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdel-fattah M, Mostafa A, Young D, Ramsay I. Evaluation of transobturator tension-free vaginal tapes in the management of women with mixed urinary incontinence: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:150, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309:814–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]