Abstract

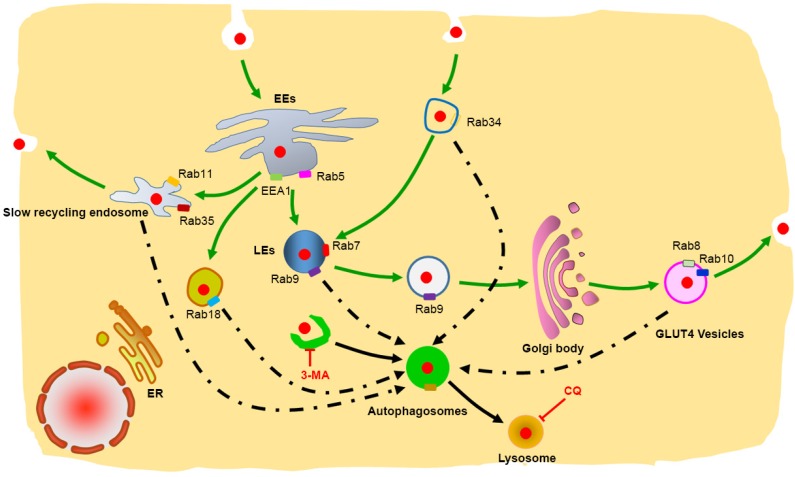

The inner membrane vesicle system is a complex transport system that includes endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy. However, the details of the intracellular trafficking pathway of nanoparticles in cells have been poorly investigated. Here, we investigate in detail the intracellular trafficking pathway of protein nanocapsules using more than 30 Rab proteins as markers of multiple trafficking vesicles in endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy. We observed that FITC-labeled protein nanoparticles were internalized by the cells mainly through Arf6-dependent endocytosis and Rab34-mediated micropinocytosis. In addition to this classic pathway: early endosome (EEs)/late endosome (LEs) to lysosome, we identified two novel transport pathways: micropinocytosis (Rab34 positive)-LEs (Rab7 positive)-lysosome pathway and EEs-liposome (Rab18 positive)-lysosome pathway. Moreover, the cells use slow endocytosis recycling pathway (Rab11 and Rab35 positive vesicles) and GLUT4 exocytosis vesicles (Rab8 and Rab10 positive) transport the protein nanocapsules out of the cells. In addition, protein nanoparticles are observed in autophagosomes, which receive protein nanocapsules through multiple endocytosis vesicles. Using autophagy inhibitor to block these transport pathways could prevent the degradation of nanoparticles through lysosomes. Using Rab proteins as vesicle markers to investigation the detail intracellular trafficking of the protein nanocapsules, will provide new targets to interfere the cellular behaver of the nanoparticles, and improve the therapeutic effect of nanomedicine.

Keywords: Nanomedicine, Endocytosis, Autophagy, Exocytosis, Protein nanocapsules.

Introduction

Most human diseases, including cancer, diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases, are caused by mutations in a class of specific genes. Mutations in these genes can induce the transcription of dysfunctional or nonfunctional proteins that cause pathogenesis. Protein therapy is one of the safest and most direct approaches for the treatment of disease by replenishing functional proteins within unhealthy cells 1. However, the poor stability and low cellular permeability of the proteins makes protein therapy difficult to apply clinically 2. In recent years, a novel delivery platform based on nanocapsules was developed to deliver proteins to target cells. Nanocapsules are designed to consist of a protein core and a thin permeable degradable polymeric shell 3-5. Once the degradable nanocapsules enter the cells, their shells break down and release the core proteins into the cytoplasm 5.

Including the newly designed protein nanocapsules, many biodegradable nanocarried particles have been developed, such as PLGA(poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based nanoparticles, micelles, chitosan and microgels 6-10. Most of these nanocarriers are used as drug nano-vehicles and have promising effects for drug delivery, such as a long lifecycle in the blood stream, targeting to specific cells with ligands on the surface of the particles or cells and multiple drug targets 7, 11. These designed nanocarriers must enter the cells and release the drugs to the target cells to execute their missions. Most nanoparticles enter the target cells through endocytosis 12. The main endocytosis pathways are either clathrin dependent or clathrin independent 12. The clathrin independent pathways include the micropinocytosis, caveolin dependent and caveolin independent (Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42 and RhoA- dependent) pathways 12. After crossing the cell membrane, the nanoparticles are sequestered in vesicles. These vesicles are transported to early endosomes (EEs) and late endosomes (LEs) and finally fuse with lysosomes 12, 13. Most developed nanoparticles, including PLGA-based nanoparticles, micelles, chitosan and microgels, have been shown to traffic in this classic endocytosis pathway. Modification of nanoparticles with various ligands, such as histidine, detergent and cell membrane penetrating peptides, enhances the nanoparticles' escape from the endo-lysosome system 14-16.

The inner membrane vesicle system is a complex transport system that includes endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy, which is responsible for the transport of various macromolecules between different organelles in the cells 17-19. The crosstalk between endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy makes these networks much more complex. Other endocytotic pathways exist in addition to the EEs-LEs-lysosome pathway. Recycling of the endosome system is responsible for delivering protein receptors back to the cell membrane 12. The exocytosis pathway is responsible for the transportation of mature proteins from the Golgi body to the cell membrane or for secreting the proteins out of the cells 19. Autophagy is a cellular process that engulfs cellular components, such as cytoplasm, damaged mitochondrial, aggregated proteins and invading pathogens 18. Moreover, there are multiple pathways that exist in endocytosis, recycling endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy. However, most studies focus on the intracellular trafficking and, accordingly, the design of nanocarriers is limited to the EEs-LEs-lysosome pathway. The trafficking pathways such as recycling endosomes, exocytosis and autophagy of the nanoparticles in the cells are poorly investigated and unknown.

The Rab protein family consists of GTPases/GTP- binding proteins that are evolutionary conserved from yeast to humans. Rab proteins have various cellular functions, including protein trafficking, transmembrane signal transduction and the fusion of vesicles between different organelles 20. More than 70 human Rab proteins have been identified, and the functions of 30 Rab proteins have been identified 21. Most of these Rab proteins are involved in the trafficking of vesicles in and across endocytosis, recycling endocytosis and exocytosis pathways 22. Rab5 and Rab7 have been well studied and have become the most important organelle identity markers of EEs and LEs in the endocytic pathway, respectively 22. To investigate in detail, the trafficking pathways of protein nanocapsules, we used these Rab proteins as vesicle markers to track the intracellular travel pathway of nanoparticles. The crosstalk between the endocytosis and exocytosis pathway with autophagy has also been extensively investigated, through the manipulation of the exocytosis and autophagy pathways with inhibitors such as 3-MA (autophagy inhibitor) and CQ (lysosome inhibitor), which block the degradation of the protein nanocapsules. The effects of the protein nanocapsules may extensively improve when combined with drugs that can block the autophagy and exocytosis pathways.

Materials and methods

Materials

Bovine serum albumin, dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO), Chloroquine (CQ), and 3-methyladenine (3-MA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). N-acryloxysuccinimide (NAS), acrylamide (AAm), N, N-methylene bisacrylamide (BIS), ammonium persulphate (APS), N, N, N', N'-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Aladdin Industrial Co. LTD. (Shanghai, China). N-(3-Aminopropyl) methacrylamide hydrochloride was purchased from Polymer Science, Inc. All other chemicals of the highest quality were commercially available and used as received. Lyso-Tracker Red was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Antibodies against LC3, Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42, RhoA, P62, EEA1, Clathrin, Caveolin were from Cell Signaling Technology. The antibody against LAMP1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, and the antibody against β-actin was obtained from Abmart.

Plasmid and transfection

The EGFP-LC3 and DsRed-LC3 plasmids were created in our laboratory. The DsRed-Rab5, DsRed-Rab7 and Flag-Rubicon plasmids were purchased from Addgene. The KSHV Flag-vBcl-2 plasmid was kindly provided by Professor Beth Levine from the University of Texas Department of Medicine. The Rab1-37 genes in the T Vector were from Professor Jiahuai Han's Lab and sub-cloned into EGFP-C1 and DsRed-C1, respectively. All plasmids were confirmed by automated DNA sequencing. Cells were transiently transfected with the plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Synthesis of nBSA

The synthesis procedures were similar to reference 4. First, 20 mg of BSA in 4 ml of pH 8, 50 mM sodium carbonate buffer was reacted with 0.5 mg N-acryloxysuccinimide in 50 ml DMSO for 2 h at room temperature. Then, the reaction solution was thoroughly dialysed against pH 7.0, 20 mM phosphate buffer. Using 10 mg acryloylated BSA solution at 1 mg/ml, radical polymerization from the surface of the acryloylated protein was initiated by adding APS dissolved in deoxygenated and deionized water and TEMED into the test tube. A specific amount of N-(3-Aminopropyl) methacrylamide (Apm), AAm and BIS (molar ratio BSA/ Apm/ AAm/ BIS/ Aps/ TEMED = 1 / 500 / 2500 / 300 / 300 / 1200) dissolved in deoxygenated and deionized water was added to the test tube over 60 min. The reaction was allowed to proceed for another 60 min in a nitrogen atmosphere. Finally, dialysis was used to remove monomers and initiators. The unmodified BSA was removed using ion exchange chromatography.

Characterization of nBSA

Ion exchange chromatography was performed with a DEAE Sephadex A-25. Gel electrophoresis results were quantified with ImageQuant LAS4000 after agarose gel electrophoresis in 0.7% agarose gels. TEM images of nanocapsules were obtained with a Philips EM120 TEM at 100000X. Before observation, nanocapsules were negatively stained using 1% pH 7.0 phosphotungstic acid (PTA) solution. Zeta potential and particle size distribution were measured with a Malvern particle sizer Nano-ZS.

Cell culture

MCF-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS).

Cellular uptake of nBSA

FITC was used as a model fluorescent molecule and was formulated in nBSA. Non-transfected or DsRed-Rab1-38 were incubated with 1 mg/mL FITC-label nBSA at 37 ℃ for 20 h. For lysosome detection, the cells were incubated with Lyso-Tracker Red for 1 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS three times and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Cells were stained with DAPI for 15 min and washed three times with PBS. Confocal microscopy was performed with a FLUO-VIEW laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1000, Olympus Optical, Japan) in sequential scanning mode using a 60~100×objective. The operation processes were similar to reference 23.

Autophagy assays

Cells were transfected with EGFP-LC3 under the indicated conditions and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The percentages of cells with fluorescent dots representing EGFP-LC3 translocation were counted by confocal microscopy as described previously 24-26.

LC3II protein level was detected using an anti-LC3 antibody.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting analysis was performed as previously described 24, 27. In brief, cell lysates were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using an LC3 antibody, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection (Thermo Scientific).

Immunofluorescence assay

Briefly, the cells were incubated with the following primary antibodies: EEA1, Clathrin, LC3, Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42, RhoA, P62, EEA1, and Caveolin. TRITC and FITC labeled secondary antibodies were used to detect the primary antibodies.

Statistical methodology

All results are reported as the mean ± S.D of three independent experiments. Comparisons were performed using two-tailed paired Student's t tests (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001).

Results and discussion

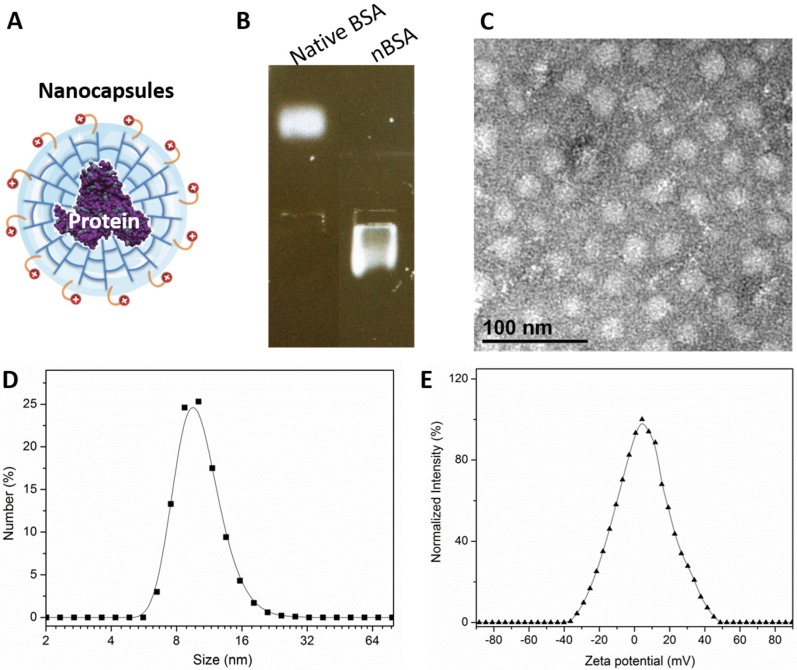

Preparation and Characterization of BSA nanocapsules (nBSA)

We prepared BSA nanocapsules (nBSA) that consist of a single-protein core and thin polymer shell anchored covalently to the protein core through in situ polymerization 4. Fig. 1A is a schematic illustration of nBSA. The gel electrophoresis results indicated that the charge of nBSA was opposite to that of native BSA. Native BSA had a negative charge, whereas nBSA had positive charge, which demonstrates that BSA was completely encapsulated and nBSA was successfully synthesized (Fig. 1B). As shown in the TEM image (Fig. 1C), nBSA was spherical, with a diameter of approximately 20 nm. Dynamic light scattering (DSL) measurements indicated that the size of nBSA was uniformly distributed and consistent with the TEM results (10.74 ± 0.95 nm) (Fig. 1D). The zeta potential of nBSA was measured to be 5.28 ± 0.43 mV (Fig. 1E). The positive charge could help nBSA internalize quickly into cancer cells. The yield of the protein nanocapsules was higher than 95%.

Figure 1.

Formation of nBSA. (A) Schematic illustration of nBSA. (B) Gel electrophoresis results of BSA and nBSA. (C) TEM image of nBSA. (D) Size distribution of nBSA determined with DLS. (E) Zeta potential distribution of nBSA. Scale bars: 50 nm.

Endocytosis pathway of protein nanocapsules

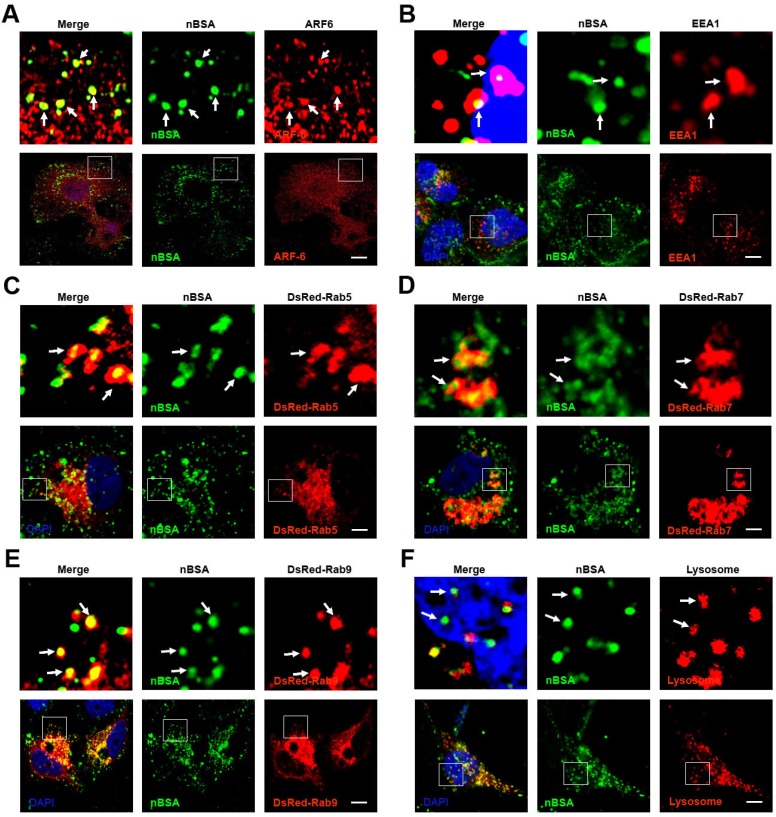

Endocytosis includes clathrin dependent and clathrin independent pathways. The clathrin independent pathway includes the micropinocytosis, caveolin dependent and caveolin independent (Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42 and RhoA-dependent) pathways 12. To detect the pathways through which the protein nanocapsules enter the cells, MCF-7 cells were treated with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 hours. We observed many FITC-positive vesicles containing nBSA within the cells. We then detected the localization of the FITC-positive vesicles with Clathrin, Caveolin, Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42 and RhoA- positive vesicles. We found that FITC-positive vesicles co-localized with Arf-6 positive vesicles, but not with clathrin, caveolin, Flotillin, Cdc42 or RhoA- positive vesicles (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1A-E). These data indicated that the cells uptake protein nanocapsules through Arf-6 dependent endocytosis but not through clathrin- or caveolin-dependent pathway endocytosis.

Figure 2.

The nBSA enters the cells through Arf-6 dependent endocytosis. (A, B) Confocal images of MCF-7 cells, which were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 hours. Arf-6 and EEA1 were detected with primary antibodies against Arf-6 and EEA1, respectively. (C, D, E) DsRed-Rab5, DsRed-Rab7, DsRed-Rab9 transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h. (F) For lysosome detection, the MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h and then co-treated with Lyso-Tracker Red probes for 30 min. Scale bars: 10 μm.

The classic endocytosis pathways include EEs, LEs and lysosomes. Rab5 and its effector EEA1 have been widely used as a marker of EEs, whereas Rab7 is a marker of LEs 17. Therefore, we used EEA1 and DsRed-Rab5 to label the EEs and DsRed-Rab7 and Rab9 to label LEs. We then treated MCF-7 cells transfected with the vector and DsRed-Rab7 with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. We found that the FITC-labeled nBSA containing vesicles co-localized with EEA1 and DsRed-Rab5-labeled EEs (Fig. 2B, C). FITC-labeled nBSA containing vesicles also co-localized with DsRed-Rab7 and Rab9 positive LEs (Fig. 2D, E). Lyso-Tracker Red probes were used to detect lysosomes. As expected, FITC-positive vesicles co-localized with the lysosomes (Fig. 2F). These data demonstrated that the protein nanocapsules were taken up by the cells through Arf-6 dependent endocytosis, transported to LEs and EEs, and finally degraded through the classic endocytosis pathway.

In addition to Rab5 and Rab7, more than 30 types of Rab proteins have been identified. These Rab proteins have specific functions in vesicle trafficking 22. Among these Rab proteins, Rab 18, 21, 23 and 34 have also been reported to be involved in the endocytosis pathway 22, 28. However, only Rab5 and Rab7 have been widely detected in endocytosis for tracking the travel pathway of the nanoparticles. To investigate the other intra-trafficking pathways of protein nanocapsules, we treated the DsRed Rab18, 21, 23 and 34 transfected MCF-7 cells with FITC-labeled nBSA (Table 1). We found that FITC-positive vesicles co-localized with DsRed-Rab18, 23, and 34 positive vesicles but not Rab21 (Fig. 3 and S2). Micropinocytosis is a type of clathrin independent endocytosis, which is controlled by Rab34. Thus, Rab34 is a marker of micropinocytosis 21, 22. We observed that Rab34 positive vesicles colocalized well with FITC-labeled nBSA (Fig. 3A). To investigate the downstream pathway of micropinocytosis, we detected the co-localization between DsRed-Rab34 with the markers of the classic endocytosis pathway (EEA1, EGFP-Rab7 and lysosome). Notably, we found that Rab34 could co-localize with EGFP-Rab7 and lysosomes but not with EEA1 (Fig. 3B and Fig.S2A, B). These data indicated that micropinocytosis (Rab34 positive)-LEs (Rab7 positive)-lysosomes might be a novel endocytosis pathway involved in the turnover of protein nanocapsules.

Table 1.

Endocytosis marker co-localization with FITC-labeled nBSA.

| Protein Markers | Co-localization with nBSA | Subcellular localization | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Internalization | |||

| Clathrin | NO | Cell membrane | Clathrin-dependent endocytosis |

| Caveolin | NO | Cell membrane | Caveolin-dependent endocytosis |

| RhoA | NO | Cell membrane | RhoA-dependent endocytosis |

| Cdc42 | NO | Cell membrane | Cdc42-dependent endocytosis |

| Flotillin | NO | Cell membrane | Flotillin-dependent endocytosis |

| Arf6 | YES | Cell membrane | Arf6-dependent endocytosis |

| Rab proteins in trafficking | |||

| Rab1 | NO | ER-Golgi intermediate | ER-Golgi trafficking |

| Rab2 | NO | ER-Golgi intermediate | ER-Golgi trafficking |

| Rab3 | NO | TGN-apico-lateral membranes | Exocytosis of secretory granules and vesicles from TGN to apico-lateral |

| Rab4 | NO | Early and recycling endosomes | Endocytic recycling to plasma membrane |

| Rab5 | YES | Early endosome | Endocytic internalization and early endosome fusion |

| Rab6 | NO | Intra-Golgi | Intra-Golgi transport |

| Rab7 | YES | Late endosome | Control late endocytic trafficking |

| Rab8 | YES | Median Golgi and TGN | Basolateral protein transport from median Golgi and TGN |

| Rab9 | YES | Late endosome | Transport from late endosomes to trans-Golgi |

| Rab10 | YES | Median Golgi and TGN | Basolateral protein transport from median Golgi and TGN |

| Rab11 | YES | Recycling endosomes | Transport from the Golgi, and apical and basolateral endocytic recycling |

| Rab12 | Not Tested | Peripheral region of cell to perinuclear centrosomes | Transport from peripheral region of cell to perinuclear centrosomes |

| Rab14 | NO | Early endosomes and Golgi | Transport between early endosomes and Golgi |

| Rab15 | Not Tested | Early and recycling endosomes | Inhibitor of endocytic internalization |

| Rab17 | Not Tested | Epithelial-specific; apical recycling endosome | Transport through apical recycling endosomes |

| Rab18 | YES | ER and liposome | Liposome formation |

| Rab20 | YES | Recycling endosome | In apical endocytosis/recycling |

| Rab21 | NO | Cell membrane | Focal adhesion site transport |

| Rab22 | YES | Early endosomes and TGN | Transport between TGN and early endosomes and vice versa |

| Rab23 | YES | Plasma membranes and early endocytic vesicles | Transport between plasma membranes and early endocytic vesicles |

| Rab24 | YES | ER/cis-Golgi region and on late endosomal structures | Autophagy-related processes |

| Rab25 | YES | Apical recycling endosome | Transport through apical recycling endosomes |

| Rab26 | NO | TGN-apico-lateral membranes | Exocytosis of secretory granules and vesicles from TGN to apico-lateral membranes |

| Rab31 | YES | Early endosomes and TGN | Transport between TGN and early endosomes and vice versa |

| Rab32 | NO | Melanosomes | Biogenesis of melanosomes |

| Rab38 | NO | Melanosomes | Biogenesis of melanosomes |

| Rab34 | YES | Micropinocytosis | Biogenesis of micropinocytosis |

| Rab35 | YES | Recycling endosomes | Apical endocytic recycling |

| Rab43 | NO | ER-Golgi intermediate | ER-Golgi trafficking |

| Autophagy | |||

| LC3 | YES | Autophagosome | Autophagosome formation |

Figure 3.

The nBSA enters the cells through the micropinocytosis-LEs-lysosome pathway. (A, B) DsRed-Rab34 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h; DsRed-Rab34 cells were co-transfected with EGFP-Rab7. (C-F) DsRed-Rab18 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h; EEA1 was then detected with a primary antibody against EEA1; DsRed-Rab18 cells were co-transfected with EGFP-Rab7; for lysosome detection, the MCF-7 cells were transfected with DsRed-Rab18 and then co-treated with Lyso-Tracker Red probes for 1 h. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Rab18 is a well-known marker for lipid droplets in adipocytes 29. Rab18 is associated with lipid droplets and the release of lipids from lipid droplets in adipocytes and is therefore an excellent marker to follow the dynamics of lipid droplets 21. Notably, we observed that Rab18 positive vesicles merged with FITC-nBSA positive vesicles (Fig. 3C). To investigate the relationship between Rab18-positive vesicles and the classic endocytosis pathway, we examined the co-localization of DsRed-Rab18 and the markers of the classic endocytosis pathway (EEA1, EGFP-Rab7 and lysosomes). We found that Rab18 could co-localize with EEA1 and lysosomes but not with EGFP-Rab7 (Fig. 3D-F). To confirm this result, we examined the co-localization of DsRed-Rab18 with another LE marker, the Rab protein EGFP-Rab9. DsRed-Rab18 also did not co-localize with EGFP-Rab9 (Fig.S3A). Therefore, the LEs-liposome (Rab18 positive)-lysosome pathway is another novel endocytosis pathway involved in the turnover of the protein nanocapsules.

Rab23 is an inhibitor of hedgehog signaling; however, the function of Rab23 in endocytosis is poorly understood 30-32. Rab23 is supposed to be involved in the transport system between plasma membranes and early endocytic vesicles 21. We observed that Rab23 positive vesicles merged well with FITC-labeled protein nanocapsules (Fig. S4A). Therefore, we examined the co-localization of DsRed Rab23 and cell membrane markers (clathrin, caveolin, Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42 and RhoA) and EEs (EEA1). Rab23 colocalized with clathrin, Arf-6, Flotillin, Cdc42, RhoA and EEA1, but not caveolin (Fig.S4B-G). These data indicated that Rab23 might have an important function in the trafficking between the cell membrane and EEs. Rab23 may help Arf-6 positive vesicles transport protein nanocapsules to EEs.

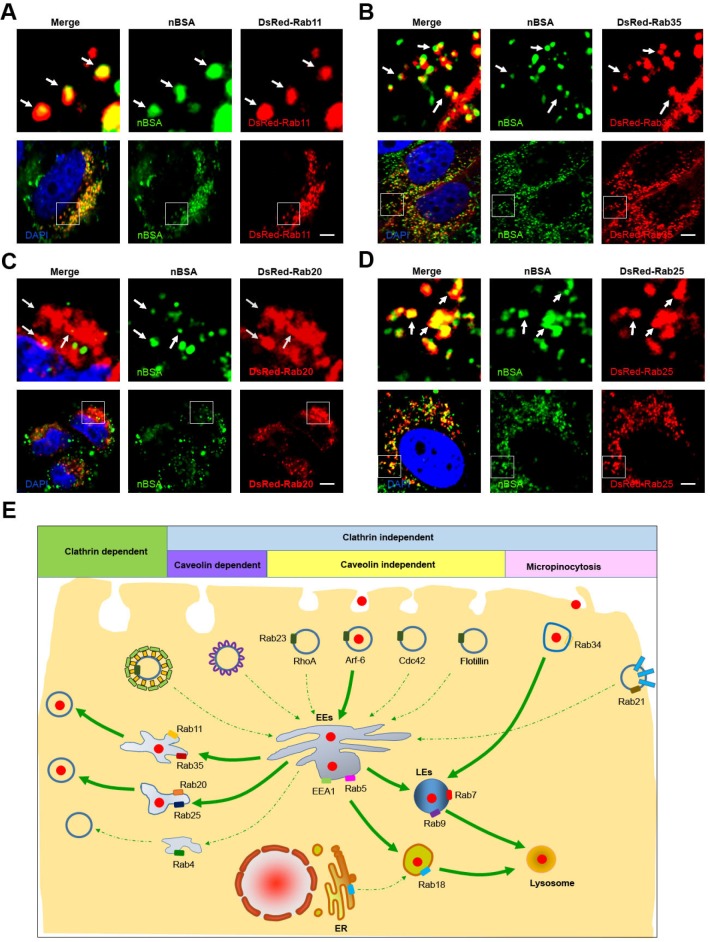

Recycling endosome pathway transport protein nanocapsules

Recycling endosomes are responsible for the redelivery of protein receptors from EEs back to the cell membrane 28. Rab proteins, including Rab4, 11, 15, 17, 20, 25 and 35, have been reported to regulate the formation of recycling endosomes 21, 28. Among these Rab proteins, Rab11 and Rab35 mediate slow endocytic recycling directly from EEs 22, 28. Rab4 mediates fast endocytic recycling from EEs 22, 28. Rab15, 17, 20 and Rab25 control trafficking through the apical recycling endosomes to the apical plasma membrane 22, 28, 29. It is not known whether nanoparticles can be released from the cells through the recycling endosome system. To determine whether protein nanocapsules could be delivered by recycling endosomes, we treated the DsRed-Rab4, 11, 20, 25 and 35 transfected MCF-7 cells with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. We examined the co-localization between nBSA and these Rab proteins (Table 1). We found that FITC-positive nBSA localized with Rab11 and 35 positive slow recycling endosomes and Rab20 and 25 positive apical recycling endosomes (Fig. 4A, B and S5A). However, FITC-positive protein nanocapsules did not co-localize with Rab4 positive fast recycling endosomes (Fig. S5B). These data indicated that nBSA could be transported out of the cells through the slow (Rab11 and Rab35 positive) and apical (Rab20 and Rab25 positive) recycling endosome pathways to release the nanoparticles out of the cells.

Figure 4.

nBSA through the recycling pathway. (A, B) DsRed-Rab11 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h; DsRed-Rab35 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h. (C, D) DsRed-Rab20 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h; DsRed-Rab25 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h. Scale bars: 10 μm. (E) Schematic representation of the pathway through which the BSA-nanocapsules enter the cells, turnover in the cells and transport out of the cells.

According to our data, we determined that protein nanoparticles could enter the cells through Arf-6 dependent endocytosis and Rab34 positive micropinocytosis (Fig. 4E). Two pathways are involved in protein nanocapsule turnover: the EEs-LEs-lysosome and the EEs-Liposome-lysosome pathway (Fig. 4E). Protein nanocapsules could be transported out of the cells through the slow and apical recycling endosome pathways to release the nanoparticles out of the cells (Fig. 4E).

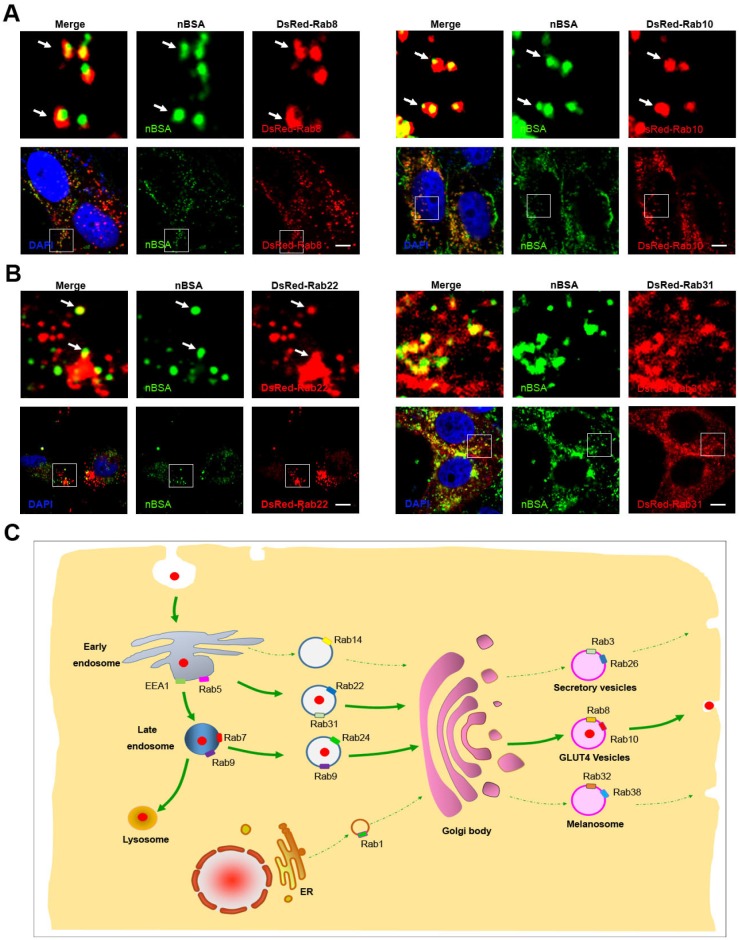

Exocytosis pathway of protein nanocapsules

Exocytosis is an energy-consuming process by which cells direct the contents of secretory vesicles out of the cell membrane and into the extracellular space 19, 33. Some Rab proteins regulate the formation, transport and fusion of these secretory vesicles and have become markers for some secretory vesicles 21, 22. Rab3, Rab26, Rab27 and Rab37 mediate classic secretory vesicles 21, 22. Rab8, Rab10 and Rab14 participate in GLUT4 vesicle translocation 21, 22. Rab27, Rab32 and Rab38 mediate the translocation of melanosomes to the cell periphery 22, 28. To investigate whether protein nanocapsules could be transported out of the cell through the exocytosis pathway, we treated DsRed-Rab3, Rab26, Rab37, Rab8, Rab10, Rab14, Rab27, Rab32, and Rab38 transfected MCF-7 cells with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h (Table 1). We found that FITC-positive nBSA co-localized with DsRed Rab8 and Rab10-positived vesicles (GLUT4 vesicle) (Fig. 5A and S7A).

Figure 5.

nBSA through the exocytosis pathway. (A) DsRed-Rab8 transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h; DsRed-Rab10 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h. (B) DsRed-Rab22 transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h; DsRed-Rab31 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled BSA-nanocapsules for 20 h. (C) Schematic representation of how the cells use the Rab8, Rab10-positived GLUT4 transport vesicles pathway to transport protein nanocapsules out of the cells.

However, FITC-positive protein nanocapsules neither co-localized with DsRed Rab3 and Rab26 positive secretory vesicles (Fig.S6A-C) nor Rab32 and Rab38 positive melanosomes (Fig.S6D-F). These data indicated that protein nanocapsules could be secreted to the extracellular environment through the Rab8 and Rab10-positive GLUT4 vesicle pathway.

DsRed Rab8 and Rab10-positived GLUT4 transport vesicles are formed from the TGN 22. Thus, the protein nanocapsules should be transported into the Golgi, and then sequestered in GLUT4 transport vesicles. The Golgi body could receive the components from EEs and LEs 22. Rab14, Rab22 and Rab31 positive vesicles are transport vesicles from EEs to the TGN 22. Rab9 positive vesicles are responsible for the transportation from LEs to the TGN 20. To test whether the protein nanocapsules were transported from EEs to TGN, we treated the DsRed-Rab14, DsRed-Rab22 and DsRed-Rab31 transfected MCF-7 cells with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. We observed that DsRed-Rab22 and DsRed-Rab31 positive vesicles co-localized with nBSA but not Rab14 (Fig. 5B and S7B). To test whether the protein nanocapsules were transported from LEs to the TGN, we treated the DsRed-Rab9 and 24 transfected MCF-7 cells with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. We found that DsRed-Rab9, DsRed-Rab22 and DsRed-Rab31 positive vesicles could co-localize with nBSA (Fig. 2E and S7C). These data indicated that the TGN might receive the protein nanocapsules from both of EEs and LEs.

Next, we also tested Rab1 and Rab44 positive vesicles, which are responsible for ER-TGN trafficking. However, we observed that DsRed-Rab1 and Rab44 positive vesicles did not transport the protein nanocapsules (Fig. S8A, B). Rab6 mediates transport in the Golgi body; however, Rab6 positive vesicles did not transport nBSA (Fig. S8C). These data indicated that the Golgi body might receive protein nanocapsules from both EEs and LEs. Then, the cells use the Rab8 and Rab10-positive GLUT4 transport vesicles pathway to transport protein nanocapsules out of the cells (Fig. 5C).

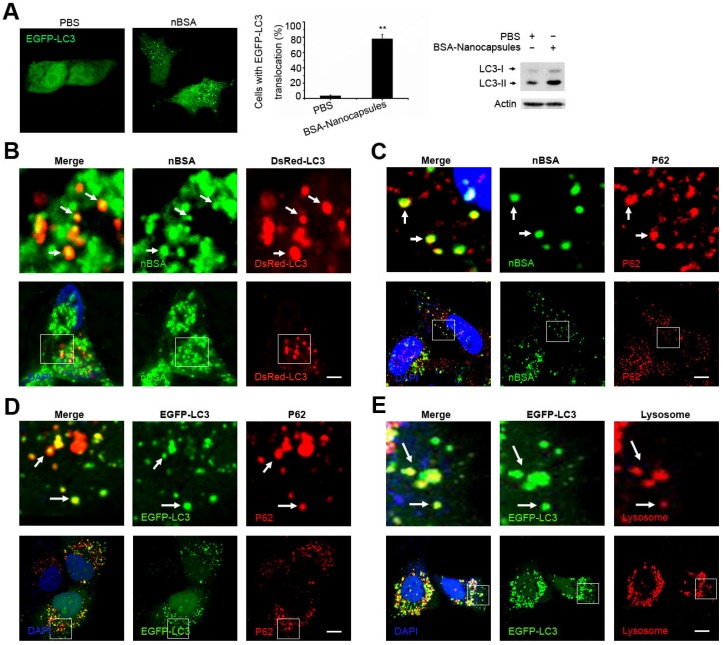

Autophagy pathway of protein nanocapsules

Autophagy is a cellular process for degrading protein aggregates, damaged organelles such as damaged mitochondria, and invading pathogens such as viruses 18, 34. Previously, we reported that autophagy also could sequester some biodegradable nanoparticles, such as PLGA-based nanoparticles and micelles 25, 35, 36. Because the components and structure of protein nanocapsules are similar to protein aggregates, autophagy may also sequester these protein nanocapsules 37. To measure autophagy, we examined autophagosome (LC3-positive vesicle) formation and LC3II protein levels 38. When autophagy is initiated, LC3 is cut on its C-terminal end to produce the LC3II protein, which is then transferred to the autophagosome 38. To investigate the relationship between protein nanocapsules and autophagy, we transfected cells with EGFP-LC3. To detect whether the protein nanocapsules induced autophagy, EGFP-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were incubated with nBSA for 20 h. Afterwards, substantial autophagosomes were induced within the cells (Fig. 6A). LC3-II protein levels were also increased in the cells (Fig. 6A). To further investigate whether protein nanocapsules could be degraded through the autophagy pathway, we used red fluorescent-labeled LC3 protein (DsRed-LC3) to detect autophagy and FITC-labeled nBSA. DsRed-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. After 20 h incubation, the FITC-labeled nBSA were sequestered within DsRed-LC3 positive autophagosomes (Fig. 6B). P62, also known as sequestosome 1(SQSTM1), is one of the most characterized substrates of selective autophagy 38. LC3 directly interacts with P62/SQSTM1 and captures P62 on the isolation membrane 38. P62 is an adapter molecule that selectively recognizes and binds the substrates of autophagy, such as proteins, organelles and microbes 20-22. Because protein nanocapsules are similar to protein aggregates, we hypothesized that P62/SQSTM1 might mediate the selective autophagy of the protein nanocapsules. As expected, we found that the FITC-positive vesicles merged with P62/SQSTM1 in the cells (Fig. 6C). However, P62/SQSTM1-protein merged with autophagosomes perfectly (Fig. 6D). Finally, the autophagosomes were then translocated to fuse with the lysosome for degradation (Fig. 6E). These data indicated that P62/SQSTM1 selectively captures the nanocapsules and delivers them to autophagosomes. These data demonstrated that the nBSA could be degraded through the autophagy pathway.

Figure 6.

nBSA induces autophagy and are sequestered by the autophagosomes. (A) Representative images and quantification of MCF-7 cells with EGFP-LC3 vesicles (autophagosomes). EGFP-LC3 transfected cells were treated with 1 mg/mL non-labeled nBSA for 20 h. Scale bars: 10 μm. Data are provided as the means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001 compared to controls. (B) LC3I/II protein levels were analyzed by western blotting in the MCF-7 cells treated in (A). (C) DsRed-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h; MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h and then P62 was detected with a primary antibody against P62. (D) DsRed-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells and then P62 was detected with a primary antibody against P62. (E) EGFP-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were co-treated with Lyso-Tracker Red probes for 1 h. The autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes (arrows). The above images are enlarged from the white outline in the images below. Scale bars: 10 μm.

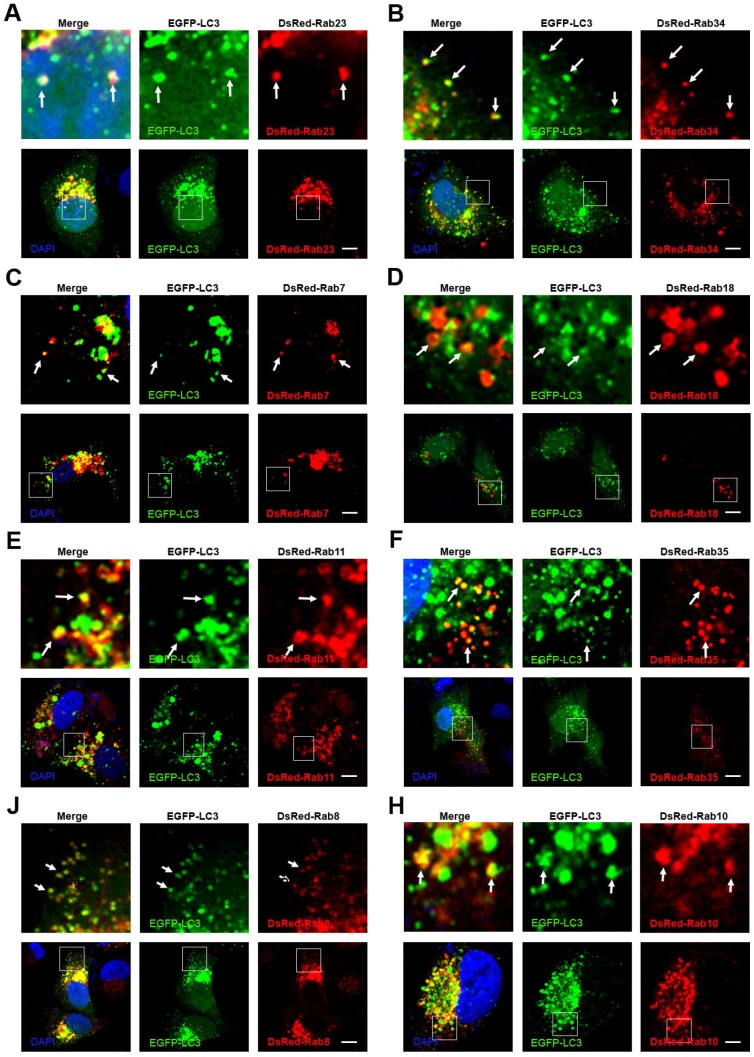

Crosstalk between endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy

In recent years, studies have shown that some Rab proteins are involved in the regulation of autophagy, such as Rab5, Rab7, Rab8, Rab9, Rab11, Rab20, Rab32 and Rab33 39. These findings suggest that the endocytosis and exocytosis pathways may have crosstalk with autophagy. In selective autophagy, P62 selects the target and LC3 selects P62 38. We have observed that autophagosomes contain biodegradable nanoparticles, such as PLGA-based NPs, micelles, and protein nanocapsules 35, 36. The autophagosome may sequester the nanoparticles directly. However, there may be another mechanism in which autophagosomes fuse with Rab protein positive vesicles of endocytosis and exocytosis. To investigate whether autophagosomes have crosstalk with these Rab positive vesicles, we co-transfected MCF-7 cells with EGFP-LC3 and DsRed Rab proteins representing various vesicles of endocytosis and exocytosis. The nBSA were internalized into the cells through Arf-6 dependent endocytosis and Rab34 positive micropinocytosis. Then, the protein nanocapsules could be delivered to lysosomes by three different pathways: (I) EEs (EEA1 and Rab5 positive)-LEs (Rab7 positive)-lysosome, the classic endocytosis pathway; (II) the Micropinocytosis (Rab34 positive)-LEs (Rab7 positive)-lysosome pathway; (III) the EE-liposome (Rab18)-lysosome pathway. We observed that EGFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes could merge with Rab23, Rab34, Rab7 and Rab18 positive vesicles (Fig. 7A-D). These data indicated that autophagosomes might receive protein nanocapsules through these endocytosis-related vesicles.

Figure 7.

Crosstalk between endocytosis, exocytosis and autophagy. (A-H) EGFP-LC3 cells were co-transfected with DsRed-Rab23, DsRed-Rab34, DsRed-Rab7, DsRed-Rab18, DsRed-Rab11, DsRed-Rab35, DsRed-Rab8 and DsRed-Rab10, respectively. Scale bars: 10 μm.

We also tested whether the recycling endosomes had crosstalk with autophagosomes. We previously mentioned that protein nanocapsules could be sequestered in slow recycling endosomes and apical recycling endosomes. To determine whether autophagy had crosstalk with recycling endosomes, we co-transfected the MCF-7 cells with EGFP-LC3 and DsRed-Rab4 (fast recycling endosome), Rab11, Rab35 (slow recycling endosome), Rab15, Rab17 and Rab25 (apical recycling endosome). We found that only DsRed-Rab11 and Rab35 co-localized with EGFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes (Fig. 7E, F). These data indicated that autophagosomes might also receive the protein nanocapsules through recycling endosomes.

We also demonstrated that protein nanocapsules could be sequestered in GLUT4 transport vesicles. To detect whether autophagy had crosstalk with exocytosis, we co-transfected the MCF-7 cells with EGFP-LC3 and DsRed-Rab3, Rab26, Rab37 (Secretory vesicles), Rab8, Rab10, Rab14 (GLUT4 vesicles), Rab32, and Rab38 (melanosomes). We observed that Rab8 and Rab10 positive GLUT4 vesicles co-localized with autophagosomes (Fig. 7J, H). DsRed-Rab3 and Rab26 positive secretory vesicles and Rab32 and Rab38 positive melanosomes did not merge with EGFP-LC3 positive autophagosomes (Fig.S9A-C). These data suggest that autophagosomes may receive the protein nanoparticles from Rab11 positive slow recycling endosomes or Rab8 positive GLUT4 vesicles.

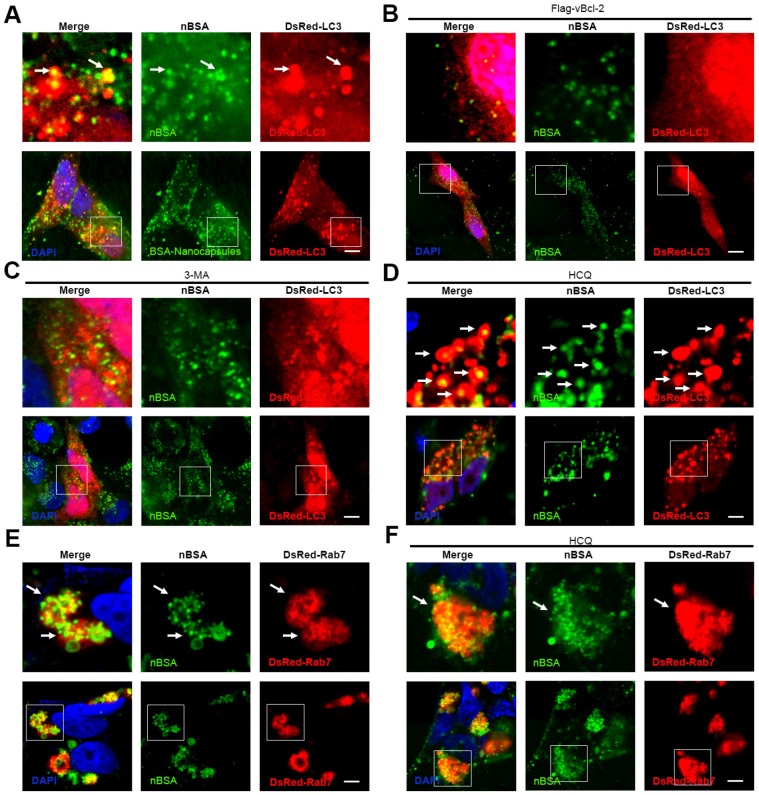

Inhibiting autophagy blocks the degradation of nBSA by the auto-lysosome pathway

Protein nanocapsules must enter the cytoplasm to execute their function, particularly the protein molecules. However, the cellular trafficking of the protein nanocapsules will transport them to lysosomes for degradation from endocytosis and autophagy.

Therefore, inhibition of the degradation of protein nanocapsules by lysosomes will be important. The class III PI3K complex, including Atg14L, Beclin1, hVps34, hVps15, UVRAG, Rubicon and Bcl-2 family members, is a major complex that regulates the autophagy and endosome pathways 40. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus Bcl-2 (KSHV vBcl-2) can significantly inhibit autophagy 24. Therefore, we first investigated whether vBcl-2 could inhibit autophagy and block the transport of protein nanocapsules by autophagy. As expected, overexpression of Flag-vBcl-2 inhibited the formation of autophagosomes; FITC-labeled nBSA could not be sequestered by the autophagosomes (Fig. 8A, B). 3-MA is a chemical inhibitor of hVps34 that can inhibit the activity of the Class III PI3K complex and the initiation of autophagy 18. Treatment of the cells with 3-MA also inhibited the formation of autophagosomes and blocked the degradation of protein nanocapsules by the autophagy pathway (Fig. 8 C, D).

Figure 8.

Inhibiting autophagy and exocytosis enhances the effect of protein nBSA. (A, B) DsRed-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h; DsRed-LC3 cells were co-transfected with Flag-vBcl-2 and then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h. (C, D) Representative images of MCF-7 cells with DsRed-LC3 vesicles. The DsRed-LC3 transfected MCF-7 cells were co-treated 10 μM 3-MA and 30 μM CQ, respectively. (E, F) DsRed-Rab7 transfected MCF-7 cells were then treated with 1 mg/mL FITC-labeled nBSA for 20 h; The DsRed-Rab7 transfected MCF-7 cells were co-treated with 30 μM CQ. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Chloroquine is a lysosome tropic agent that prevents endosomal acidification and disrupts lysosomes 36. Therefore, because CQ blocked the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, numerous autophagosomes accumulated in the cytoplasm. Treatment of the cells with CQ also blocked the degradation of protein nanocapsules by lysosomes (Fig. 8D). Because Rab7 positive LEs also must fuse with lysosomes for the final degradation of nanocapsules, disruption of lysosomes also resulted in the accumulation of LEs. Treatment of the cells with CQ for 20 h caused the DsRed-Rab7 positive LEs to accumulate, and prevented the degradation of the protein nanocapsules by lysosomes (Fig. 8E, F). Thus inhibition of the autophagy and endocytosis pathways by inhibitors could block the degradation of protein nanocapsules by lysosomes (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the degradation pathway of protein nanocapsules in cell. Rab34 positive micropinocytosis, Rab7 and Rab9 positive late endosome, Rab18 positive liposome, Rab11 and Rab35 positive slow recycling endosome, Rab8 and Rab10 positive GLUT4 vesicles co-localize with autophagosomes.

Conclusions

In this paper, we determined that FITC-labeled nBSA are internalized by cells mainly through Arf6-dependent endocytosis and Rab34 mediated micropinocytosis. Moreover, we used more than 30 Rab proteins to investigate the detail intracellular trafficking pathway of nBSA. In addition to the classic pathway, we identified two other novel transport pathways: micropinocytosis pathway and liposome pathway. Cell also used slow endocytic recycling and GLUT4 exocytosis vesicles transport the nBSA out of the cells. Autophagy also sequester the nBSA through p62 and other endosome vesicles. Using an autophagy inhibitor (3-MA) and lysosome inhibitor (CQ) to block these transport pathways eliminated the degradation of nanoparticles through lysosomes. Rab family proteins are specific markers on the endo trafficking vesicles, which are excellent vesicle markers to investigation the detail intracellular trafficking of the nanoparticles. These new trafficking findings will provide new targets to interfere the cellular behaver of the nanoparticles, and improve the therapeutic effect of nanomedicine.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31270019), Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholar (No. 2014A030306036), Guangdong Special Support Program, Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2016A020217001), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2015M580109), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2016A030310023), Science, Technology & Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (Nos. JCYJ20150430163009479 and JCYJ20150529164918738).

References

- 1.Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE. Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2008;7:21–39. doi: 10.1038/nrd2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ. et al. Cell-penetrating peptides. A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:585–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas A, Joo KI, Liu J, Zhao M, Fan G, Wang P. et al. Endoprotease-mediated intracellular protein delivery using nanocapsules. ACS nano. 2011;5:1385–94. doi: 10.1021/nn1031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan M, Du J, Gu Z, Liang M, Hu Y, Zhang W. et al. A novel intracellular protein delivery platform based on single-protein nanocapsules. Nature Nanotechnology. 2010;5:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao M, Biswas A, Hu B, Joo KI, Wang P, Gu Z. et al. Redox-responsive nanocapsules for intracellular protein delivery. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gothwal A, Khan I, Gupta U. Polymeric Micelles: Recent Advancements in the Delivery of Anticancer Drugs. Pharmaceutical Research; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danhier F, Feron O, Preat V. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Passive and active tumor targeting of nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;148:135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yue ZG, Wei W, Lv PP, Yue H, Wang LY, Su ZG. et al. Surface charge affects cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of chitosan-based nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:2440–6. doi: 10.1021/bm101482r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyon LA, Fernandez-Nieves A. The polymer/colloid duality of microgel suspensions. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2012;63:25–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032511-143735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan S, Wu T, Zhang D, Zhang Z. Cell or cell membrane-based drug delivery systems. Theranostics. 2015;5:863–81. doi: 10.7150/thno.11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Cui H. Nanostructure-Based Theranostic Systems. Theranostics. 2016;6:1274–6. doi: 10.7150/thno.16479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahay G, Alakhova DY, Kabanov AV. Endocytosis of nanomedicines. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;145:182–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinc A, Battaglia G. Exploiting endocytosis for nanomedicines. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5:a016980. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang G, Li C, Lu W, Ding J. N-Boc-histidine-capped PLGA-PEG-PLGA as a smart polymer for drug delivery sensitive to tumor extracellular pH. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2010;10:1248–56. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copolovici DM, Langel K, Eriste E, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides: design, synthesis, and applications. ACS nano. 2014;8:1972–94. doi: 10.1021/nn4057269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chugh A, Eudes F, Shim YS. Cell-penetrating peptides: Nanocarrier for macromolecule delivery in living cells. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:183–93. doi: 10.1002/iub.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huotari J, Helenius A. Endosome maturation. The EMBO Journal. 2011;30:3481–500. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology; 2011. p. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutagalung AH, Novick PJ. Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiological Reviews. 2011;91:119–49. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00059.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhuin T, Roy JK. Rab proteins: the key regulators of intracellular vesicle transport. Experimental Cell Research. 2014;328:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10:513–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Tao W, Chen Y, Chang D, Wang T, Zhang X. et al. Doxorubicin-loaded star-shaped copolymer PLGA-vitamin E TPGS nanoparticles for lung cancer therapy. Journal of Materials Science Materials in Medicine. 2015;26:165. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5498-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T. et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Molecular Cell. 2007;25:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Yang Y, Liang X, Zeng X, Liu Z, Tao W. et al. Enhancing therapeutic effects of docetaxel-loaded dendritic copolymer nanoparticles by co-treatment with autophagy inhibitor on breast cancer. Theranostics. 2014;4:1085–95. doi: 10.7150/thno.9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Zhang H, Liang X, Zhang J, Tao W, Zhu X. et al. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Autophagosome Accumulation through Multiple Mechanisms: Lysosome Impairment, Mitochondrial Damage, and ER Stress. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2016;13:2578–87. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang X, Yang Y, Wang L, Zhu X, Zeng X, Wu X. et al. pH-Triggered burst intracellular release from hollow microspheres to induce autophagic cancer cell death. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2015;3:9383–96. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordens I, Marsman M, Kuijl C, Neefjes J. Rab proteins, connecting transport and vesicle fusion. Traffic. 2005;6:1070–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozeki S, Cheng J, Tauchi-Sato K, Hatano N, Taniguchi H, Fujimoto T. Rab18 localizes to lipid droplets and induces their close apposition to the endoplasmic reticulum-derived membrane. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118:2601–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eggenschwiler JT, Espinoza E, Anderson KV. Rab23 is an essential negative regulator of the mouse Sonic hedgehog signalling pathway. Nature. 2001;412:194–8. doi: 10.1038/35084089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans TM, Ferguson C, Wainwright BJ, Parton RG, Wicking C. Rab23, a negative regulator of hedgehog signaling, localizes to the plasma membrane and the endocytic pathway. Traffic. 2003;4:869–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0854.2003.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuller K, O'Connell JT, Gordon J, Mauti O, Eggenschwiler J. Rab23 regulates Nodal signaling in vertebrate left-right patterning independently of the Hedgehog pathway. Developmental Biology. 2014;391:182–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mochida S. Activity-dependent regulation of synaptic vesicle exocytosis and presynaptic short-term plasticity. Neuroscience Research. 2011;70:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim YM, Jung CH, Seo M, Kim EK, Park JM, Bae SS. et al. mTORC1 phosphorylates UVRAG to negatively regulate autophagosome and endosome maturation. Molecular Cell. 2015;57:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Zeng X, Liang X, Yang Y, Li X, Chen H. et al. The chemotherapeutic potential of PEG-b-PLGA copolymer micelles that combine chloroquine as autophagy inhibitor and docetaxel as an anti-cancer drug. Biomaterials. 2014;35:9144–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Dong Y, Zeng X, Liang X, Li X, Tao W. et al. The effect of autophagy inhibitors on drug delivery using biodegradable polymer nanoparticles in cancer treatment. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1932–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mei L, Zhang X, Feng SS. Autophagy inhibition strategy for advanced nanomedicine. Nanomedicine. 2014;9:377–80. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szatmari Z, Sass M. The autophagic roles of Rab small GTPases and their upstream regulators: a review. Autophagy. 2014;10:1154–66. doi: 10.4161/auto.29395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N. et al. Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nature Cell Biology. 2009;11:385–96. doi: 10.1038/ncb1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.