Abstract

Viruses must remain infectious while in harsh extracellular environments. An important aspect of viral particle stability for double-stranded DNA viruses is the energetically unfavorable state of the tightly confined DNA chain within the virus capsid creating pressures of tens of atmospheres. Here we study the influence of internal genome pressure on the thermal stability of viral particles. Using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to monitor genome loss upon heating, we find that internal pressure destabilizes the virion, resulting in a smaller activation energy barrier to trigger DNA release. These experiments are complemented by plaque assay and electron microscopy measurements to determine the influence of intra-capsid DNA pressure on the rates of viral infectivity loss. At higher temperatures (65 – 75 °C), failure to retain the packaged genome is the dominant mechanism of viral inactivation. Conversely, at lower temperatures (40 – 55 ºC), a separate inactivation mechanism dominates, which results in non-infectious particles that still retain their packaged DNA. Most significantly, both mechanisms of infectivity loss are directly influenced by internal DNA pressure, with higher pressure resulting in a more rapid rate of inactivation at all temperatures.

Introduction

A virus can generally be described as a nucleic acid genome contained within a protective protein shell, termed the capsid. The viral replication cycle is composed of two distinct processes—delivery of the genetic material to the host (infection) and the subsequent production of new virions (replication). After viral replication, virions released from cells must persist in the external environment until an encounter with a new cellular host. Viral particles must be sufficiently stable to sustain infectivity over time in response to various harsh environmental conditions. For example, loss of viral infectivity occurs in response to elevated temperatures or solutions of low ionic strength1; 2. Previous studies have demonstrated that under such conditions the rate of genome loss from virions approximated the decreasing proportion of infectious virions1; 2. Particles that packaged shorter genome lengths had an increased ability to remain infectious over a longer time in these conditions1; 2. These results show that the packaged genome within the viral capsid influences viral particle stability. In this work, we specifically investigate the influence of internal genome pressure on viral particle stability and infectivity in response to elevated temperatures.

During replication of phage λ, the double-stranded (ds) DNA genome is actively packaged into the capsid by a powerful molecular motor3. The resulting state of packaged DNA is highly energetically unfavorable due to bending stress of the stiff DNA polymer and repulsive electrostatic and hydration forces between neighboring DNA helices4; 5; 6. These forces create an internal pressure of tens of atmospheres within the viral capsid. Internal DNA pressure was first experimentally verified for phage λ7, and was also demonstrated for phages SPP18 and T59. More recently, internal genome pressure was confirmed within an Archaeal virus (His1)10 and a eukaryotic virus (Herpes Simplex virus type 1; HSV-1)11. Experimental and theoretical work has investigated the role of internal pressure for receptor-triggered DNA ejection7; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17. Here, using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), we investigate the influence of internal DNA pressure on the thermal stability of viral particles.

We show that DSC measurements provide direct detection of viral genome loss upon heat treatment. This approach allows us to quantitatively describe the process of DNA release at higher temperatures. Using DSC we investigate the influence of internal pressure for viral particle stability, as it relates to DNA retention. Calorimetric studies provide a quantitative description of the energy barriers associated with viral particle stability. We complement our calorimetric experiments with plaque assay measurements to determine the influence of internal pressure on the time dependence for viral infectivity loss in response to elevated temperatures. These combined approaches allow us to monitor viral particle stability and infectivity under identical environmental conditions. We observe two different mechanisms of viral inactivation over the investigated temperature range (40 – 80 °C). Viral inactivation at higher temperatures (above 65 °C) is specifically due to DNA release from the virus, which we determine by DSC. At temperatures below 55 °C, a separate inactivation mechanism dominates, resulting in non-infectious virions that still retain their packaged genome. By comparing genome packaging density and buffer ionic conditions (e.g. Mg2+ ion concentration) we show that both inactivation mechanisms are specifically dependent on internal DNA pressure. Throughout the entire investigated temperature range, higher internal pressures result in faster rates of infectivity loss over time. These experiments reveal that success of the viral replication cycle directly relates to internal genome pressure through its influence on viral particle stability and infectivity.

Results and Discussion

Detecting heat-induced DNA Release with DSC

A DSC temperature scan measures the heat capacity of the viral sample relative to buffer solution alone. Thermally induced transformations in the viral particle result in heat absorbed or released into the surroundings. The DSC feedback system responds to these events by reducing or increasing the heat supplied to the sample cell in order to keep the temperature equal to the buffer reference cell. This leads to negative or positive peaks in the resulting heat capacity versus temperature data. Each peak provides direct measurement of the energetics and transition temperatures for a specific heat-induced process. Endothermic transitions—such as protein denaturation or DNA melting—result in positive peaks in the heat capacity versus temperature profile, while exothermic events yield downward peaks.

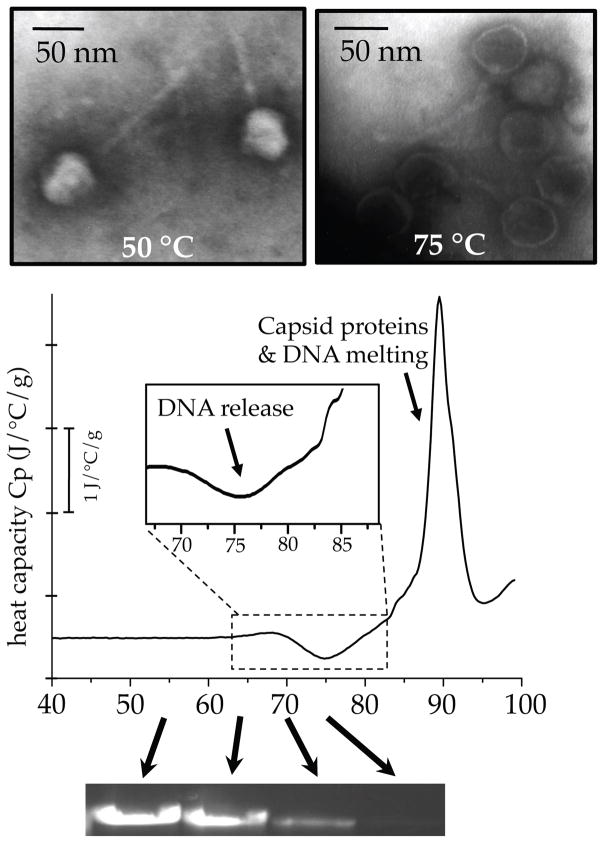

DSC scans of wild-type (wt) DNA length phage λ in 10 mM MgCl2 Tris-buffer at 200 °C/hour scan-rate (Figure 1) show an exothermic peak followed by a large complex endothermic transition spanning from ~80 to 95 °C. The endothermic signal corresponds to capsid protein denaturation and DNA melting, which have previously been described in detail for DSC scans of phage λ18, as well as HK9719. Our focus is specifically on the exothermic peak of DNA release (~75 °C) that occurs prior to the larger endothermic events. The temperature range of this exothermic peak matches the temperature of heat-induced DNA release from λ virions, determined by the accessibility of the viral genome to DNase digestion as a function of temperature. Capsids were incubated at various temperatures, followed by DNase I treatment at 37 °C to digest any DNA that was released from capsids during the elevated temperature incubation. The protected DNA that remains within capsids is extracted and visualized following gel electrophoresis (lower panel of Figure 1). The decreasing intensity of the DNA band for samples incubated above 70 °C represents the increasing amount of viral DNA released during higher temperature incubations. Electron microscopy (EM) images of λ virions after brief incubation at 75 °C show that the overall capsid structure and tail appear intact (upper panel of Figure 1), but have clearly lost their packaged genomes (as judged by the darker staining of the capsid volume compared to virions incubated at 50 °C, which appear lighter because the negative stain is excluded from within the capsid due to the presence of packaged DNA). The temperature for heat-induced DNA ejection observed here also coincides with previous experiments on phage λ utilizing light scattering to monitor genome release as a function of temperature18. Further, by measuring receptor-triggered genome release using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), we previously confirmed that DNA ejection from viral capsids does indeed have a measurable exothermic enthalpy component13; 20. By inducing genome release with heat treatment, rather than a cellular receptor protein, we probe the overall stability of packaged DNA within virions. This approach assays the process of genome release as it relates to viral infectivity loss and also allows quantification of the energetics of the packaged genome. A major advantage of studying the energetics of genome release by DSC is that isolation and purification of a specific cellular receptor is not required to trigger the DNA ejection event. The requirement of receptor purification has limited earlier in vitro ejection studies to a select few viruses for which protein receptors have been identified and isolated7; 8; 9.

Figure 1.

DSC scans of phage λ reveal the exothermic peak of heat-induced DNA release. DSC scan of phage λ performed in 10 mM MgCl2 Tris-buffer at 200 °C/hour. The exothermic peak near 75 °C (inset) represents DNA release from virions. (Upper panel) Negative stain electron microscopy (EM) images showing DNA-filled virions that retain their packaged genome after brief incubation below the DNA release temperature at 50 °C (left), whereas virions incubated at the temperature of the exothermic peak (75 °C) no longer contain packaged genomes, but rather still show intact capsid and tail structures (right). (Lower panel) Gel electrophoresis bands showing that the decreasing amount of protected DNA within capsids corresponds with the temperature of the exothermic peak in DSC scans (bands correspond to incubations at 55, 65, 70, and 75 °C).

Influence of pressure on viral particle stability

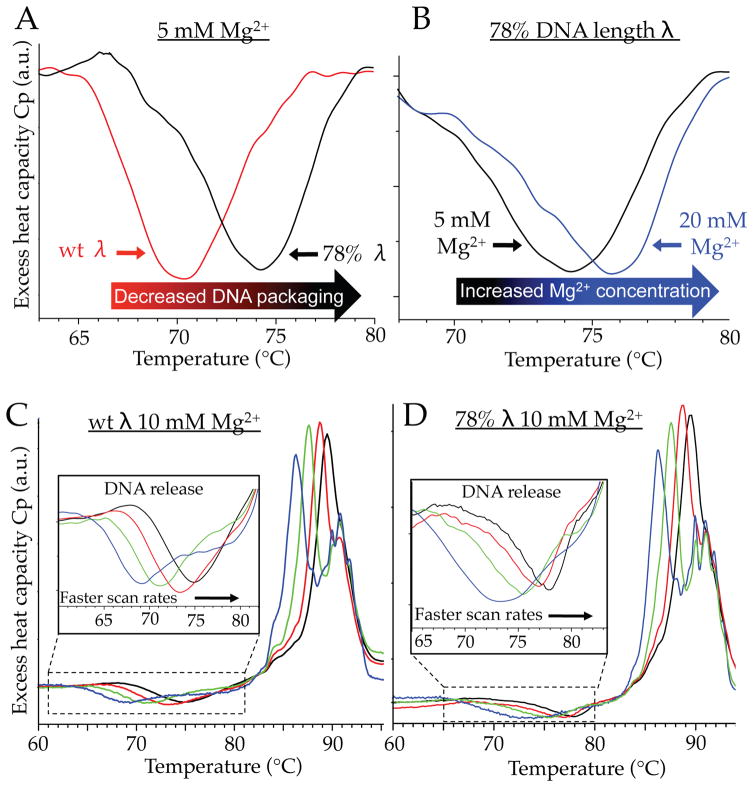

Varying the amount of DNA packaged within the virus provides a direct interrogation for the role of internal pressure for viral particle stability. For a given temperature scanning-rate, DNA release from the shorter genome mutant consistently occurs at a higher temperature relative to wt DNA length λ (Figure 2A, and comparison of panels C and D). Figure 2A shows a comparison of the ejection peak for DSC scans performed at 90 °C/hour in 5 mM MgCl2 for wt (red line) and 78% (black line) DNA length λ. A reduction in the amount of DNA inside the virus (yielding a lower internal pressure21) results in an increased thermal stability of the viral particle for DNA retention, whereas the temperature of capsid protein denaturation remains unchanged for the different genome packaging lengths18. Furthermore, since the viral capsid is permeable to small ions, internal DNA pressure can also be manipulated by the ionic conditions of the suspending buffer22. The blue line of Figure 2B represents 78% DNA λ virions scanned in the presence of 20 mM MgCl2 compared to 5 mM MgCl2 (black line). The increased ionic screening (resulting in decreased internal pressure) yields a further increase in thermal stability of the viral particle. These comparisons clearly reveal that internal DNA pressure has a direct influence on particle stability for genome retention. Comparing single DSC scans for each condition (ionic concentration and DNA length) primarily provides insight on the relative stability of the overall system (packaged DNA and viral proteins). DSC experiments that utilize scan-rate dependence of the DNA release event provide analysis of the energetic barriers associated with genome retention and particle stability. This approach is used to further investigate the influence of internal genome pressure on the energetics of initiating DNA loss from heated virions.

Figure 2.

(A) DSC scans at 90 °C/hour showing that the reduced packaging density of 78% DNA λ (black) results in a higher temperature to trigger heat-induced DNA release compared to wt DNA λ (red) in 5 mM MgCl2. (B) Increasing the Mg2+ concentration from 5 mM (black) to 20 mM (blue) further stabilizes the 78% DNA length λ virion, resulting in a higher temperature of DNA release. Influence of temperature scanning rate on wt (C) and 78% (D) DNA length λ virions performed in 10 mM MgCl2 buffer. DSC scans were performed at 60 (blue), 90 (green), 150 (red), and 200 °C/hour (black). For both viral strains, faster scanning rates result in shifting the DNA release peak toward higher temperature (insets). The minimum for the peak of DNA release was reproducible to within 0.1 °C.

Scan-rate dependence of DNA ejection

DNA ejection from virions is inherently a non-equilibrium event (once DNA release is triggered, it progresses irreversibly to the final state). DSC scans of wt DNA length λ in 10 mM MgCl2 Tris-buffer are shown in Figure 2C at four different temperature scanning rates ranging from 60 to 200 °C/hour. As illustrated in the inset of Figure 2C, experiments performed at faster scanning rates result in the ejection peak shifting toward higher temperatures. At the lowest scanning rate (60 °C/hour; blue line) the minimum in the ejection peak occurs at 69.2 ± 0.1 °C, and is progressively shifted toward higher temperatures for faster scan rates, reaching 74.8 ± 0.1 °C at the fastest scanning speed (200 °C/hour; black line). Scan-rate dependence is also observed for the capsid denaturation peak, which shifts from 86 to ~90 °C with increasing temperature scanning rates. A corresponding scan-rate dependence has previously been observed in DSC experiments on phage P22 capsid protein transformations23, but has yet to be described for the process of DNA release from virions.

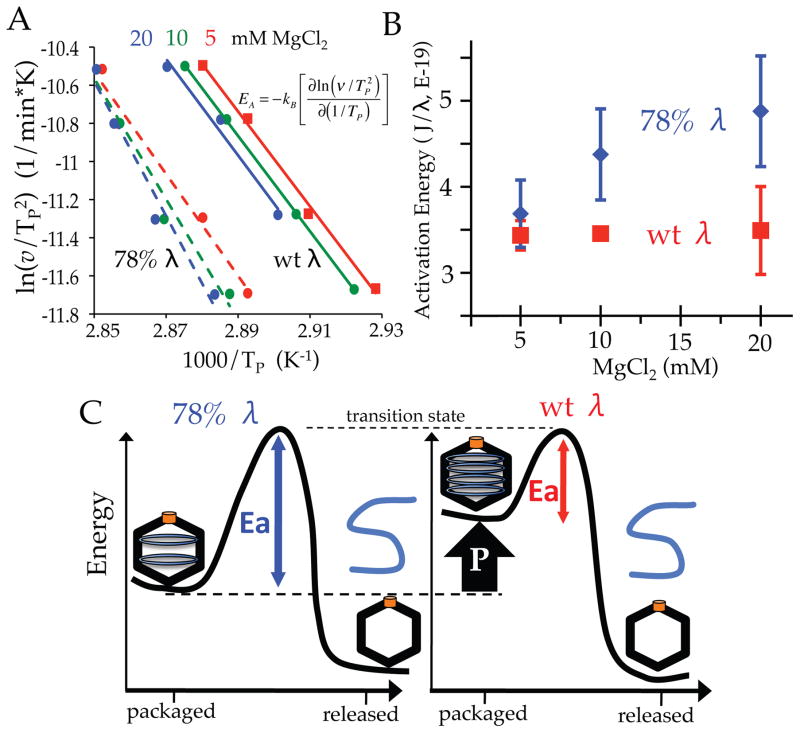

The temperature shifts of the calorimetric peaks are indicative of a rate-limiting step in the heat-induced transition24. This scan-rate dependence can be used to investigate the rate constant of the kinetically limiting step for the observed reaction. We show that the rate at which particles lose their packaged DNA decreases exponentially over time (see below). This exponential decrease is indicative of a first order reaction, where the observed rate of genome loss depends only on the number of DNA-filled virions present over time. First order kinetics for genome loss coincides with the anticipation that it is a uni-molecular reaction, with each virion releasing its genome independently of other viral particles in the sample. Further, we also show (see below) that the rate constant describing DNA release changes exponentially with inverse temperature (Arrhenius dependence). These two observations allow us to study heat-induced DNA release within a previously developed model describing the scan-rate dependence of thermal transitions24. By presuming a first order reaction with a rate constant (k) that changes according to the Arrhenius equation (k = Aexp[−EA/kBT]), the model provides an estimate of the underlying activation energy barrier (EA) associated with the thermal transition (kB is the Boltzmann constant and A is the pre-exponential factor). The temperature of the ejection peak position (TP) is predicted to vary with the scanning-rate (v) according to v/TP2 = (AkB/EA)exp(−EA/kBTP)24. The solid green line of Figure 3A shows this analysis applied to the scan-rate dependence of DNA release from phage λ in 10 mM Mg2+ Tris buffer. (Data points were determined from the peak positions in the DSC scans shown in Figure 2C). The slope of the plot of ln(v/TP2) as a function of inverse temperature (Figure 3A) provides the activation energy (EA) for DNA release from the viral particle (Figure 3B). Next, we investigate the influence of internal genome pressure on this activation energy barrier relating to DNA retention within the virion. Pressure is manipulated in the DSC scans by varying the genome packaging density and ionic conditions of the suspending buffer.

Figure 3.

(A) The dependence of the DNA release peak position (plotted as inverse temperature) on the temperature scanning rate (60, 90, 150, and 200 °C/hour). Analysis was performed on wt (solid lines) and 78% (dotted lines) DNA length λ virions in 5 (red), 10 (green), and 20 (blue) mM MgCl2 buffers. (B) Activation energy for heat-induced DNA release determined from the linear fits in (A) (see text for further description) for each buffer and DNA length condition. (C) Schematic illustrating that decreased internal pressure (from either reduced DNA packaging or ionic conditions) results in higher activation energies for DNA release from λ virions. This is due to higher internal pressures resulting in an increased internal energy, which effectively lowers the overall energy barrier height.

Internal pressure modifies activation energy for DNA release from capsid

In addition to wt DNA length λ, the scan-rate dependence of the genome release peak was also analyzed in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ for a phage λ mutant that packages 78% of the wt λ DNA length (Figure 2D). Using the model described above, the activation energy of DNA release was again determined from the scan-rate dependence of the DNA ejection peak temperatures (dashed green line of Figure 3A). As illustrated above, the effect of internal pressure on viral particle stability can also be interrogated by varying the Mg2+ ion concentration (Figure 2B). The scan-rate dependence of the DNA ejection peak was also determined for both strains of phage λ (with 78% and 100% of the wt λ-DNA length packaged) in the presence of 5 and 20 mM MgCl2 (Figure 3A, red and blue lines respectively). From this analysis we can investigate the influence of internal pressure on the activation energy barrier associated with viral particle stability at elevated temperatures. Activation energy values are determined from the slopes of the lines in Figure 3A, and are presented in Figure 3B as a function of MgCl2 concentration for λ virions that package either 78% or 100% of the wt genome length.

The overall trend observed for the variations in MgCl2 and DNA density is that lower internal pressures result in larger activation energy barriers to initiate DNA release (Figure 3B). Our results reveal that the lower internal DNA pressure of the 78% DNA length mutant (15 atm, compared to 25 atm for wt DNA length λ)21 consistently results in a larger energy barrier for DNA release relative to wt DNA length λ, yielding activation energies of 4.9 ± 0.6 and 3.5 ± 0.5 E-19 Joules/virion respectively in 20 mM MgCl2. Higher salt concentrations also lower internal pressure by reducing the repulsive forces between neighboring packaged DNA helices5; 22. Correspondingly, the activation energy barrier for genome release from 78% DNA λ increases with higher MgCl2 concentrations from 3.7 ± 0.4 E-19 Joules/virion (in 5 mM MgCl2) to 4.9 ± 0.6 E-19 Joules/virion (in 20 mM MgCl2). Variations of packaged genome length and ionic conditions, together, consistently show that lower internal pressures within the viral capsid result in larger energy barriers to trigger DNA release. Table 1 summarizes the activation energy values of DNA release for all six conditions investigated.

Table 1.

Activation energy (Ea) for DNA release determined by analysis of DSC scans (Figure 3A), along with half-lives for the kinetics of viral infectivity loss determined by plaque assay (Figure 4B) at 75 and 40 °C reported in minutes (mins) and hours (hrs) respectively.

| [MgCl2] (mM) | Ea (DSC) (E-19 J/phage) | Half-life (plaque assay)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 °C (mins) | 40 °C (hrs) | |||

| wt DNA | 5 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | — | — |

| 10 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 0.83 ± 0.03 | 7.48 ± 0.21 | |

| 20 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | — | — | |

|

| ||||

| 78% DNA | 5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 6.03 ± 0.33 | 8.01 ± 0.6 |

| 10 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 9.67 ± 0.58 | 9.11 ± .025 | |

| 20 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | — | — | |

A higher internal pressure (whether by increased genome packaging density or buffer ionic conditions) results in a more energetically unstable state of the packaged DNA within the viral capsid3; 5. Although they contain different genome lengths, the protein composition of the virus particle is identical for the two λ strains studied here. Thus it is reasonable to assume that the molecular event causing DNA release is the same for both viruses. In this scenario, the energy of the transition state for DNA release would be equal for both genome mutants (Figure 3C). However, a higher initial energy state (due to increased pressure) would result in a correspondingly lower energy barrier height to trigger DNA release. This would explain the conserved trend of larger activation energy values for lower internal DNA pressures (Figure 3B). A reduced internal pressure was previously reported to lower the activation energy for DNA ejection from phage λ triggered by addition of the cellular receptor protein12. Here, our DSC studies reveal that internal pressure also has a direct effect on viral particle stability in response to elevated temperatures. Higher internal pressures destabilize the particle, resulting in a smaller activation energy barrier, which renders it more susceptible to loss of its packaged viral genome.

The influence of varying internal pressure due to increased MgCl2 concentrations is clearly evident for the activation energy barriers of DNA release from the 78% genome mutant λ. However, salt-dependence is not observed for the activation energy of genome release from wt DNA length λ. This result can be understood from the tighter spacings of packaged DNA within the wt genome length λ relative to the 78% genome mutant. Packaged viral DNA is affected by the repulsive forces between neighboring helices, as well as bending stress due to the inner radius of the capsid being comparable to the persistence length of the DNA polymer15; 16. Small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) provides structural details describing the energy of the packaged genome in terms of the average inter-axial DNA-DNA spacings (aH)4; 5; 25. At DNA spacings tighter than ~30 Å, the repulsive force between neighboring DNA strands becomes less sensitive to the buffer ionic conditions. This is due to hydration forces (rather than purely electrostatic forces) dominating the overall DNA repulsion4. At the spacings associated with the packaged 78% genome λ mutant (~30.5 Å), an increase from 5 to 20 mM MgCl2 results in progressively smaller average DNA spacings for the packaged viral genome5. The reduced electrostatic repulsion strength allows the DNA polymer to decrease the overall bending energy by pushing DNA more toward the capsid periphery, where the local DNA spacing becomes smaller. However, this effect does not occur for the packaged genome of the wt DNA length λ strain5. At the DNA spacings associated with wt λ (27.5 Å) hydration forces dominate over electrostatic forces, thus addition of Mg2+ ions from 5 to 20 mM has minimal effect on DNA spacings or the associated interaction pressure between neighboring helices4. The relatively constant activation energy value for DNA ejection from wt λ (relative to the 78% DNA length mutant) reflects the reduced dependence of MgCl2 concentration at tighter DNA spacings.

Monitoring heat-induced viral infectivity loss using plaque assay

The DSC investigations above were motivated by earlier work showing that loss of viral infectivity in response to harsh environmental conditions correlated with loss of DNA from the viral particle. Our DSC assay provides quantification of the energetics for initiating DNA release from viral particles. These experiments demonstrate the influence of internal genome pressure on viral particle stability, as it relates to stable retention of packaged DNA within virions. The temperature at which DNA release occurs in our calorimetric assays is specifically determined by the buffer conditions and scanning rate, occurring between 68 and 80 °C (Figure 2). As described above, the tightly confined dsDNA genome inside the λ viral capsid is thermodynamically unstable. It is the presence of an activation energy barrier that allows the intact virus to persist in this kinetically stable state26. Since genome release is not an equilibrium transition, this irreversible process can be studied at temperatures lower than the transition temperatures observed in DSC scans. To investigate viral particle stability over a larger temperature range, we utilized a plaque assay approach to determine the influence of internal pressure on DNA release and loss of viral infectivity.

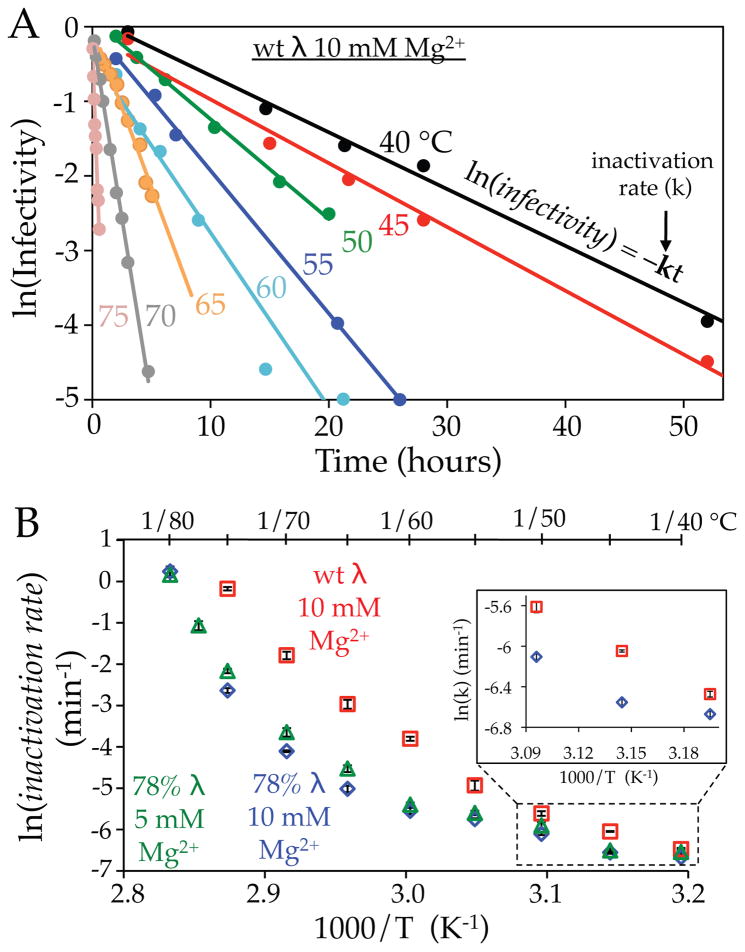

Plaque assays provide a direct measurement of the number of infectious particles. The viral sample is first mixed with a solution of cells. Viable virions will infect a host cell and through multiple rounds of replication and infection lyse the cell and its neighboring cells, creating a visible region (referred to as a plaque) in the cell layer plated on the solid growth medium on a Petri dish27. The number of infectious virions present in the sample is then directly determined by the number of observed plaques. Figure 4A shows the influence of temperature on the loss of viral infectivity over time for wt DNA length λ virions for several temperatures ranging from 40 to 75 °C. Virions are incubated at the specified temperature, and the remaining proportion of infectious particles over time is quantified. Depending on the incubation temperature, the half-life (time required for the number of viable particles to decrease by a factor of 2) of infectious virions varies from nearly 8 hours (40 °C; black line) to under one minute (75 °C, pink line). For all temperatures investigated, the proportion of infectious viral particles exponentially decreases with time (linear fits on the log-scale of Figure 4A). This is indicative of a first-order reaction dominated by a single rate-limiting step. For each temperature, the rate constant describing the loss of viral infectivity over time (k) was extracted from the exponential fits in Figure 4A. The natural logarithms of the rate constants (k) for wt λ in 10 mM Mg2+ are plotted as a function of inverse temperature in Figure 4B (red squares). In the same fashion, the exponential rate constants describing loss of viral infectivity over time were also determined for 78% DNA length λ in 5 and 10 mM MgCl2 (green triangles and blue diamonds respectively). By comparing variations in DNA packaging density and MgCl2 concentration, we investigate the influence of internal pressure for loss of viral infectivity.

Figure 4.

(A) Logarithm of the remaining proportion of viral infectivity over time for wt DNA λ in 10 mM MgCl2. Experiments were performed for various temperatures between 40 and 75 °C. For each temperature the rate constant for loss of viral infectivity (k) was determined from the exponential fits (solid lines). (B) Viral inactivation rate constants (determined from plaque assay experiments) are plotted as a function of inverse temperature (Arrhenius plot). (The corresponding values for the inverse Celsius temperatures are shown in 5 °C increments on the upper horizontal axis). Rates of viral infectivity loss are shown for wt DNA length λ in 10 mM MgCl2 (red squares), along with 78% DNA length λ in 5 mM (green triangles) and 10 mM (blue diamonds) MgCl2. The inset shows the influence of DNA packaging density for the lower temperature region.

Internal DNA pressure reduces thermal stability of phage particles

Figure 4B shows that higher internal pressures result in faster rates of infectivity loss measured by plaque assay. This is demonstrated by variations in genome packaging density or ionic buffer conditions. As noted above, reduced ionic conditions result in greater repulsive forces between neighboring packaged DNA helices5; 22. Upon reduction of the MgCl2 concentration from 10 to 5 mM, the rate of viral infectivity loss at 75 °C for the 78% DNA length mutant increases by over 60% (half-lives of ~10 and 6 minutes respectively). Additionally, internal pressure increases with the amount of DNA packaged inside the capsid21. Accordingly, the viral inactivation rate at 75 °C is over 10-fold greater for wt DNA length λ relative to the shorter genome mutant (half-lives of 50 seconds and ~10 minutes respectively). These plaque assay results precisely agree with the observed influence of internal pressure for the activation energy barrier to initiate genome release measured by DSC above (Figure 3). Note that DSC experiments specifically probe DNA loss from the virus in response to heat-treatment, whereas plaque assay experiments monitor loss of viral infectivity (regardless of the mechanisms that result in viral inactivation). From our DSC experiments above, we describe how a higher internal pressure results in lower activation energies for DNA release. Thus, higher internal pressure results in lower activation energies for DNA release (determined by DSC; Figure 3B), which corresponds to faster viral inactivation rates (determined by plaque assay; Figure 4B). Despite the mechanistic differences in the two experimental approaches, both reveal the same relative dependence of internal genome pressure for their respective measures of particle stability. Table 1 summarizes the kinetics of λ viral infectivity loss at 75 and 40 °C for the three conditions investigated.

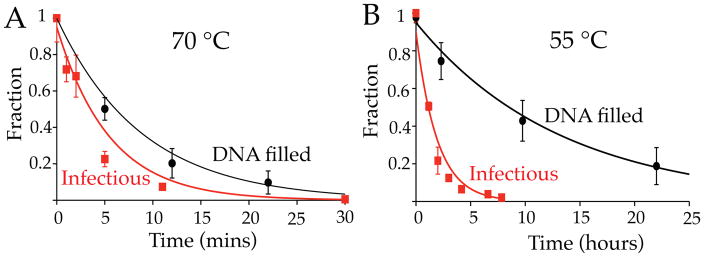

For the temperature range discussed above, the rates of viral infectivity loss appear to have an exponential dependence on inverse temperature (i.e. Arrhenius dependence), evidenced by the linearity of the high temperature portions of Figure 4B (70 – 80 °C). There is however a clear deviation from the anticipated Arrhenius dependence over the full temperature range investigated here, with the largest deviation occurring between 50 and 65 °C. Our DSC studies suggest that viral inactivation at higher temperatures is specifically due to release of the pressurized genome from the viral particle. Using time-resolved electron microscopy (EM) we could follow the kinetics for DNA loss from virions over a larger temperature range than accessible by DSC, by monitoring the conversion of DNA-filled virions to empty viral particles. DNA-containing virions appear brighter than empty particles due to the increased accumulation of stain within the capsid in the absence of the packaged genome (Figure 1). This allows us to estimate the rate of DNA loss from wt DNA length λ virions in 10 mM MgCl2 buffer. Figure 5A compares the proportion of DNA-filled particles over time (black circles) with the loss of viral infectivity determined by plaque assay (red squares) at 70 °C. At this temperature the two processes have comparable exponential decay rates for viral inactivation (0.168 ± 0.015 min−1) and DNA loss (0.106 ± 0.015 min−1). This correspondence strongly suggests that inactivation at higher temperatures is directly due to genome loss. Alternatively, at 55 °C the proportion of infectious particles decreases over 5 times faster than the proportion of DNA-filled virions, 0.43 ± 0.05 and 0.078 ± 0.009 hours−1 respectively (Figure 5B). This reveals that an additional mechanism of infectivity loss, other than DNA release, occurs at lower temperatures.

Figure 5.

(A) The proportion of remaining DNA filled virions observed over time by EM analysis at 70 °C (black circles) closely agrees with the proportion of infectious particles over time determined by plaque assay (red squares). (B) The same comparison for incubation at 55 °C shows significantly reduced kinetics for DNA release compared to infectivity loss.

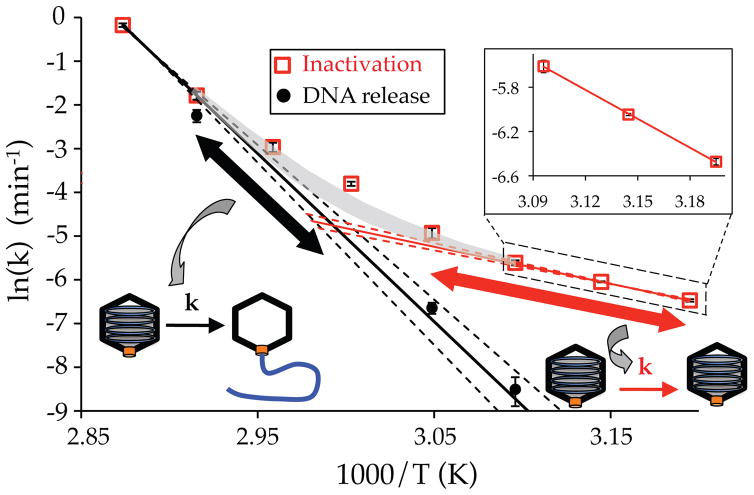

To further investigate the separate inactivation mechanisms observed for wt DNA length λ, the rate constants for DNA loss (determined by EM analysis, Figure 5) are compared with the rates of viral inactivation as a function of inverse temperature in Figure 6. (It is important to note that the rate constants describing DNA loss refer to conversion from DNA-filled to empty particles, not the rate of DNA translocation out of individual capsids. The latter is on the scale of 1 – 10 seconds12 and would not be accessible in this assay.) As Figure 6 illustrates, the rate constant for DNA release at 70 °C closely matches the rate of viral infectivity loss. Conversely, the rates of DNA loss at lower temperatures (55 and 50 °C) progressively deviate from the viral inactivation rates. Unlike the overall viral inactivation rates, rate constants for DNA loss between 50 and 70 °C follow an Arrhenius dependence with temperature (black circles), as shown by the enhanced linearity relative to the viral inactivation rates (red squares). In fact, extrapolation of the viral inactivation rates from the two highest measured temperature points (70 and 75 °C, where inactivation primarily occurs from DNA loss) yields a precise agreement with the rates of DNA loss determined by EM at 50 and 55 °C (solid black line in Figure 6). The dotted lines represent the error of the extrapolation based on the errors associated with the high temperature data points. Agreement between these independent data sets reveals that DNA loss dictates viral inactivation at higher temperatures. However, the viral inactivation rates (red squares) at temperatures below ~65 °C begin to progressively deviate from the rates of DNA loss (black line). This represents the increasing contribution of an alternative inactivation mechanism that does not relate to genome release. At 50 °C the measured rate for DNA loss is ~20 times smaller than the rate of viral infectivity loss. At progressively lower temperatures DNA loss would contribute even less to viral inactivation, being over 200 times smaller than the plaque assay measured rate of viral inactivation at 40 °C.

Figure 6.

Rate constants describing heat-induced genome release (black circles) for wt DNA length λ plotted against inverse temperature along with the rates of viral inactivation (red squares) from Figure 4B. At the higher temperature range, inactivation is dominated by genome release (black line), whereas an alternative mechanism dominates inactivation at lower temperatures (red line). Reaction rates for both mechanisms follow an anticipated Arrhenius dependence on temperature, as revealed by the linearity of the separate higher and lower (inset) temperature regions. Summing the extrapolated rate values for two separate mechanisms (shaded region) accounts for a significant degree of the observed variation in the measured rate constants.

Two DNA pressure dependent mechanisms contribute to viral inactivation

Our combined results from all three techniques (DSC, EM, and plaque assay) reveal that different mechanisms of viral infectivity loss dominate inactivation depending on the temperature range investigated. At higher temperatures (> 65 °C), loss of infectivity is directly due to release of the packaged genome, whereas viral inactivation occurs without release of the packaged genome at lower temperatures (< 50 °C). The kinetics of infectivity loss for both the high and low temperature inactivation mechanisms change with temperature according to the Arrhenius equation (a linear dependence in Figure 6). An Arrhenius dependence for viral inactivation rates below 45 °C has been previously confirmed for a diverse variety of E. coli-infecting viruses28. An Arrhenius dependence allows estimation of the expected rate constant for each mechanism throughout a larger temperature range. This is shown by the solid lines in Figure 6 corresponding to the expected rate constants for the inactivation mechanisms at lower (red line) and higher (black line) temperature. (The dotted lines represent the error of the extrapolations resulting from the errors in the inactivation rates for individual temperature data points.) The shaded curve of Figure 6 is the sum of these two extrapolations, where the width of the shading indicates the sum of the extrapolation errors. This curve represents the predicted total viral inactivation rates over the intermediate (50 – 70 °C) temperature range, which closely agrees with the measured rates (red squares). This agreement indicates that these two inactivation mechanisms together are sufficient to account for a significant degree of the overall temperature dependence for the kinetics of viral infectivity loss studied here.

Using the combined approaches of DSC and EM, we have described the influence of internal pressure on the loss of viral infectivity over time. Internal pressure influences the kinetics of viral inactivation for both observed mechanisms. This is readily apparent upon comparison of the inactivation rates between 40 and 50 °C for wt and 78% DNA length λ in 10 mM MgCl2 (Figure 4B inset). As we have recently shown, internal DNA pressure results in a mechanical force that destabilizes viral portal-tail vertex proteins that are responsible for genome retention (Bauer et. al., 2015, under review). At higher temperatures, this results in a pressure-dependent destabilization of the protein(s) that directly act to retain the tightly confined viral genome. The strong temperature dependence of this mechanism (i.e. the larger magnitude slope in Figure 6) results in a rapidly decreasing reaction rate toward lower temperatures (black line). Thus at lower temperatures the DNA loss mechanism has a minimal contribution to viral infectivity loss relative to the alternative inactivation mechanism that is independent of DNA release (red line).

Rationales for pressure-dependent inactivation of virions

From the comparison of the rates for viral infectivity loss and DNA release at 55 °C (Figure 5B), it is clear that non-infectious particles still readily lose their packaged genome during the elevated temperature incubation. Otherwise, the proportion of DNA-filled particles would become nearly constant once the population of infectious particles had significantly dropped (i.e. after ~5 minutes of incubation.) This suggests that the population of virions that are DNA filled (but non-infectious) may have lost their ability to initiate genome ejection upon interaction with the host cell. For example, the tail tip protein of phage λ (gpJ) facilitates a crucial step to initiate infection by interacting with the cellular host receptor29; 30. Minor alterations to this phage protein result in virions that retain their packaged genome but fail to initiate DNA ejection30. If heat treatment affects the integrity of this protein (or any other phage protein required for cell attachment and/or genome release), it would result in non-infectious particles that still contain their DNA. As described above, the inactivation mechanism at lower temperature is sensitive to internal pressure (Figure 4B inset), with a greater-than 20% increase in the inactivation rate at 40 °C for wt DNA length λ compared to the 78% genome length mutant (half-lives of 7.48 and 9.11 hours respectively). Thus, if loss of viral infectivity related to integrity of a specific viral protein, it would have to be a protein that physically experiences the effect of internal genome pressure. The numerous protein interactions of the phage λ portal-tail vertex31 would be potential candidates that contribute to regulating genome release32; 33 and experience the internal force of tightly packaged DNA34. It should also be mentioned that the right chromosome end of phage λ was shown to be associated with the proximal end of the tail35; 36.

Furthermore, an alternative explanation may exist for the population of non-infectious, DNA-filled virions. We have recently shown that packaged DNA within wt DNA length λ capsids exhibits a structural transition13. This temperature-induced transition results in an abrupt variation in the structure, energy, and mobility (or fluidity) of encapsidated DNA and occurs close to 37 ºC depending on the buffer conditions13. Internal pressure was found to influence the temperature at which this DNA transition occurred, with higher pressure resulting in a lower transition temperature. This is related to the fact that DNA has to reach a critical stress value before the transition can occur. Below the transition temperature, DNA mobility inside the capsid is significantly reduced relative to the higher temperature state of packaged DNA. Above the transition temperature, DNA has a more disordered state with enhanced mobility. This resulted in initiation of receptor-triggered DNA ejection occurring more readily from a significantly larger fraction of viruses for temperatures just above the transition. At the same time, below the transition temperature, DNA packaged in the capsid has restricted mobility, which delays or completely prevents its release even when the capsid is opened by receptor molecule13. Such restriction on DNA movement within the capsid may also have a role in the heat-induced formation of DNA-filled but non-infectious virions observed above.

Conclusions

The work presented here describes the loss of viral infectivity in response to temperature. At more extreme conditions (higher temperature) viral infectivity loss is a direct consequence of particles losing their highly pressurized packaged genome. We combine calorimetric measurements to monitor DNA release, along with direct measurements of viral infectivity and visualization by electron microscopy. We found that an alternative inactivation mechanism, other than DNA loss, dominates at lower temperatures. Of particular interest is the realization that both inactivation mechanisms are sensitive to internal DNA pressure. For all conditions studied, higher pressures result in increased susceptibility of the virus to infectivity loss upon exposure to elevated temperatures. This influence of tight genome packaging on viral infectivity may also be important for other classes of viruses that package single stranded (ss) DNA genomes. For instance, the eukaryotic ssDNA viruses minute virus of mice (MVM)37 and adeno associated virus (AAV)38 show an analogous viral particle destabilization due to their confined nucleic acid. In both studies genome loss was reported to occur from intact particles, similar to results for dsDNA phage λ. Furthermore, the direct role of genome confinement on particle stability for these ssDNA viruses was demonstrated by comparisons of particles that package less than full-length genomes37; 38. This suggests that similar influences of tight genome confinement may play a role in viral infectivity even for viruses that package forms of nucleic acid other than dsDNA.

Materials and Methods

Phage preparation

Procedures were performed as previously described for isolation of λ virions containing wild-type (λcI60) or 78% genome lengths (λb221)21. Phage samples were dialyzed overnight in TM buffer (50 mM Tris, supplemented by 5, 10, or 20 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4). Throughout this study, we use varying MgCl2 concentrations added to Tris-buffer. Since Tris is used for all buffers in this study, buffer solutions are referred to by the added MgCl2 concentration without specifying “Tris-buffer”.

Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC experiments were performed on a Malvern-MicroCal capillary VP-DSC, using TM buffer dialyzate as the sample reference. Experiments were performed at scan-rates of 60, 90, 150, or 200 °C per hour with viral concentrations of 1012 per mL. Replicate scans yielded reproducibility of ~0.1 °C for determining the temperature minimum of the DNA release peaks.

Plaque assays

E. coli C600 cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 in LB medium supplemented with 2 mg/mL thymine and 0.2% maltose. Viral samples were mixed with cell suspensions and spread on to LB agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 12 hours. Viral plaque counts were determined from at least two plates containing 100 to 300 plaques per plate.

Electron Microscopy

After various incubation times at specified temperatures, viral samples were stained with uranyl acetate for imaging. To determine DNA loss kinetics, one to two hundred viral particles were counted per time point, with at least four time points used per incubation temperature. For each incubation time point, counts were performed from, on average, at least 10 separate portions of one to two grids. To account for potential staining artifacts, kinetic analyses were compared to non-heated samples, which yielded 95 – 100% DNA filled virions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Verna Frasca at Malvern Instruments as well as to Julia Fecko and Neela Yennawar at the Huck Institute of the University of Pennsylvania for their generous assistance in performing calorimetric scans. We also thank Kaitlin Hamilton for her contributions to the plaque assay experiments. We acknowledge James Conway, Daniel Zuckerman, Fred Homa and Markus Deserno for fruitful discussions. This research was supported by Natural Science Foundation grant CHE-1152770 (A.E.) and the Swedish Research Council, VR grant 622-2008-726 (A.E) and, as well as NIH training grant T32 GM088119 (D.W.B).

References

- 1.Ritchie DA, Malcolm FE. Heat-stable and density mutants of phages T1, T3 and T7. J Gen Virol. 1970;9:35–43. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-9-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkinson JS, Huskey RJ. Deletion mutants of bacteriophage lambda. I. Isolation and initial characterization. J Mol Biol. 1971;56:369–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Rickgauer JP, Robertson RM, Catalano CE, Anderson DL, Grimes S, Smith DE. Measurements of single DNA molecule packaging dynamics in bacteriophage lambda reveal high forces, high motor processivity, and capsid transformations. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1113–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rau DC, Lee B, Parsegian VA. Measurement of the repulsive force between polyelectrolyte molecules in ionic solution: hydration forces between parallel DNA double helices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:2621–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu X, Rau DC, Parsegian VA, Fang LT, Knobler CM, Gelbart WM. Salt-dependent DNA-DNA spacings in intact bacteriophage lambda reflect relative importance of DNA self-repulsion and bending energies. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:028102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.028102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lander GC, Johnson JE, Rau DC, Potter CS, Carragher B, Evilevitch A. DNA bending-induced phase transition of encapsidated genome in phage lambda. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:4518–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evilevitch A, Lavelle L, Knobler CM, Raspaud E, Gelbart WM. Osmotic pressure inhibition of DNA ejection from phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9292–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1233721100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sao-Jose C, de Frutos M, Raspaud E, Santos MA, Tavares P. Pressure built by DNA packing inside virions: enough to drive DNA ejection in vitro, largely insufficient for delivery into the bacterial cytoplasm. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:346–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leforestier A, Brasiles S, de Frutos M, Raspaud E, Letellier L, Tavares P, Livolant F. Bacteriophage T5 DNA ejection under pressure. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:730–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanhijarvi KJ, Ziedaite G, Pietila MK, Haeggstrom E, Bamford DH. DNA ejection from an archaeal virus--a single-molecule approach. Biophys J. 2013;104:2264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer DW, Huffman JB, Homa FL, Evilevitch A. Herpes virus genome, the pressure is on. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:11216–21. doi: 10.1021/ja404008r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grayson P, Han L, Winther T, Phillips R. Real-time observations of single bacteriophage lambda DNA ejections in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14652–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703274104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, Sae-Ueng U, Li D, Lander GC, Zuo X, Jonsson B, Rau D, Shefer I, Evilevitch A. Solid-to-fluid-like DNA transition in viruses facilitates infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:14675–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321637111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raspaud E, Forth T, Sao-Jose C, Tavares P, de Frutos M. A kinetic analysis of DNA ejection from tailed phages revealing the prerequisite activation energy. Biophys J. 2007;93:3999–4005. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kindt J, Tzlil S, Ben-Shaul A, Gelbart WM. DNA packaging and ejection forces in bacteriophage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13671–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241486298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzlil S, Kindt JT, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. Forces and pressures in DNA packaging and release from viral capsids. Biophys J. 2003;84:1616–27. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74971-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrov AS, Harvey SC. Packaging double-helical DNA into viral capsids: structures, forces, and energetics. Biophys J. 2008;95:497–502. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu X. Heat induced capsid disassembly and DNA release of bacteriophage lambda. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39793. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duda RL, Ross PD, Cheng N, Firek BA, Hendrix RW, Conway JF, Steven AC. Structure and energetics of encapsidated DNA in bacteriophage HK97 studied by scanning calorimetry and cryo-electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2009;391:471–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeembaeva M, Jonsson B, Castelnovo M, Evilevitch A. DNA heats up: energetics of genome ejection from phage revealed by isothermal titration calorimetry. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:1079–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grayson P, Evilevitch A, Inamdar MM, Purohit PK, Gelbart WM, Knobler CM, Phillips R. The effect of genome length on ejection forces in bacteriophage lambda. Virology. 2006;348:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evilevitch A, Fang LT, Yoffe AM, Castelnovo M, Rau DC, Parsegian VA, Gelbart WM, Knobler CM. Effects of salt concentrations and bending energy on the extent of ejection of phage genomes. Biophys J. 2008;94:1110–20. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.115345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galisteo ML, King J. Conformational transformations in the protein lattice of phage P22 procapsids. Biophys J. 1993;65:227–35. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez-Ruiz JM, Lopez-Lacomba JL, Cortijo M, Mateo PL. Differential scanning calorimetry of the irreversible thermal denaturation of thermolysin. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1648–52. doi: 10.1021/bi00405a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Earnshaw WC, Harrison SC. DNA arrangement in isometric phage heads. Nature. 1977;268:598–602. doi: 10.1038/268598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Ruiz JM. Protein kinetic stability. Biophys Chem. 2010;148:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning A Laboratory Manual. 7. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Paepe M, Taddei F. Viruses’ life history: towards a mechanistic basis of a trade-off between survival and reproduction among phages. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Hofnung M, Charbit A. The C-terminal portion of the tail fiber protein of bacteriophage lambda is responsible for binding to LamB, its receptor at the surface of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:508–12. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.2.508-512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werts C, Michel V, Hofnung M, Charbit A. Adsorption of bacteriophage lambda on the LamB protein of Escherichia coli K-12: point mutations in gene J of lambda responsible for extended host range. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:941–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.941-947.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajagopala SV, Casjens S, Uetz P. The protein interaction map of bacteriophage lambda. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lhuillier S, Gallopin M, Gilquin B, Brasiles S, Lancelot N, Letellier G, Gilles M, Dethan G, Orlova EV, Couprie J, Tavares P, Zinn-Justin S. Structure of bacteriophage SPP1 head-to-tail connection reveals mechanism for viral DNA gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812407106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olia AS, Prevelige PE, Jr, Johnson JE, Cingolani G. Three-dimensional structure of a viral genome-delivery portal vertex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:597–603. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar R, Grubmuller H. Elastic properties and heterogeneous stiffness of the phi29 motor connector channel. Biophys J. 2014;106:1338–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chattoraj DK, Inman RB. Location of DNA ends in P2, 186, P4 and lambda bacteriophage heads. J Mol Biol. 1974;87:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90556-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas JO. Chemical linkage of the tail to the right-hand end of bacteriophage lambda DNA. J Mol Biol. 1974;87:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotmore SF, Hafenstein S, Tattersall P. Depletion of virion-associated divalent cations induces parvovirus minute virus of mice to eject its genome in a 3′-to-5′ direction from an otherwise intact viral particle. J Virol. 2010;84:1945–56. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01563-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horowitz ED, Rahman KS, Bower BD, Dismuke DJ, Falvo MR, Griffith JD, Harvey SC, Asokan A. Biophysical and ultrastructural characterization of adeno-associated virus capsid uncoating and genome release. J Virol. 2013;87:2994–3002. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03017-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]