Abstract

Optic disc drusen occur in 0.4% of children and consist of acellular intracellular and extracellular deposits that often become calcified over time. They are typically buried early in life and generally become superficial, and therefore visible, later in childhood, at the average age of 12 years. Their main clinical significance lies in the ability of optic disc drusen, particularly when buried, to simulate true optic disc edema. Misdiagnosing drusen as true disc edema may lead to an invasive and unnecessary workup for elevated intracranial pressure. Ancillary testing, including ultrasonography, fluorescein angiography, fundus autofluorescence, and optical coherence tomography, may aid in the correct diagnosis of optic disc drusen. Complications of optic disc drusen in children include visual field defects, hemorrhages, choroidal neovascular membrane, non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and retinal vascular occlusions. Treatment options for these complications include ocular hypotensive agents for visual field defects and intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents for choroidal neovascular membranes. In most cases, however, children with optic disc drusen can be managed by observation with serial examinations and visual field testing, once true optic disc edema has been excluded.

Keywords: Optic disc drusen, children, pediatric, pseudopapilledema, choroidal neovascular membrane

1. Introduction

Optic disc drusen are acellular calcified deposits located both intracellularly and extracellularly first described by Muller in 1858.130 The main clinical significance of optic disc drusen in children is that they can simulate true optic disc edema (Figure 1).52; 81; 127; 189; 213 Misdiagnosing drusen as true disc edema may lead to an extensive, invasive and unnecessary work-up for elevated intracranial pressure, including neuroimaging and lumbar puncture.115 Optic disc drusen are typically buried in the optic disc early in life and become more superficial later.7; 57; 79; 196 In children, therefore, drusen are more likely to be buried and may be more difficult to detect.45

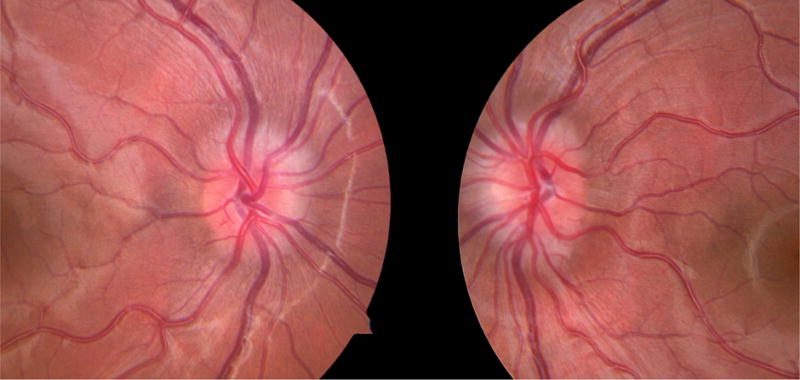

Figure 1.

Comparison of optic disc in children with optic disc drusen and papilledema. A) Optic disc photos of a 10 year old boy with bilateral buried optic disc drusen. The disc margins are blurred, but there are no hemorrhages, exudates, or vessel obscuration. B) Optic disc photos of a 5 year old girl with mild papilledema due to increased intracranial pressure secondary to the use of exogenous growth hormone. Disc margins are blurred with mild obscuration of vessels, but no hemorrhages or exudates.

1.A. Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of optic disc drusen is unknown. The three classical theories on the formation of optic disc drusen postulate that they are caused by a disturbance in axonal metabolism with slowed axoplasmic flow;197; 204 congenitally dysplastic discs with a propensity for drusen formation;139; 174 or a small scleral canal that physically compresses the optic nerve, causing ganglion cell death, with extrusion and calcification of mitochondria.132 The latter theory has been called into question by a study that showed that the scleral canal in patients with optic disc drusen was not smaller than controls when measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT).51

1.B. Demographics

The prevalence of optic disc drusen in children is about 0.4%.43 In adults, studies have found a prevalence of 0.5 to 2.4%.7; 56 The lower prevalence of optic disc drusen reported in children is likely due to the difficulty in detecting buried drusen. In children and adults, optic disc drusen are more common in females and Caucasians and are bilateral in over two-thirds of cases.7; 19; 97; 171; 203

1.C. Inheritance

Optic disc drusen are frequently familial. Family members of patients with optic disc drusen have up to ten times the risk of harboring optic disc drusen compared to the general population, and they have an increased risk of optic disc dysplasia and anomalous retinal vasculature.4; 118 Optic disc drusen can also be inherited as part of a genetic syndrome with other ocular or systemic manifestations.

2. Association of optic disc drusen with other ocular or systemic disorders

Optic disc drusen have been reported in association with many ocular (Table 1) and systemic (Table 2) disorders; however, there are only a few disorders in which optic disc drusen have been demonstrated to occur more frequently than in the general population.

Table 1.

Ocular disorders reported in association with optic disc drusen

| Acquired myelinated nerve fibers40; 83 |

| Adams-Oliver syndrome107 |

| Aneurysm of the ophthalmic artery35 |

| Astrocytic hamartoma165 |

| Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy15 |

| β-thalassemia10 |

| Birdshot chorioretinopathy and Cacchi-Ricci syndrome198 |

| Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium28 |

| Congenital night blindness205 |

| Familial macular dystrophy96 |

| Glaucoma169; 176 |

| Gyrate atrophy66; 207 |

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension67; 94; 100; 102; 166; 171; 172 |

| Idiopathic parafoveal telangiectasia133 |

| Joubert syndrome199 |

| Morning glory disc anomaly164 |

| Ocular tumoral calcinosis59 |

| Optic nerve tumors21; 111 |

| Peripapillary central serous retinopathy128 |

| Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy (PPRCA)216 |

| Pseudoxanthoma elasticum and angioid streaks33; 46; 89; 116; 122; 157; 191 |

| Retinitis pigmentosa8; 34; 41; 71; 106; 126; 130; 147; 149; 155; 161; 167; 192; 209 |

| Severe Early Childhood Onset Retinal Dystrophy (SECORD)210 |

| Tilted optic disc65 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) syndrome26 |

| VACTERL association124 |

Table 2.

Systemic disorders reported in association with optic disc drusen

| Alport syndrome54 |

| Alstrom syndrome188 |

| Cystic fibrosis72 |

| Delayed language development and dyslexia119; 180 |

| Down syndrome91 |

| Headaches and seizures disorders45; 180 |

| Intracranial tumor13; 14; 27; 120; 136; 139; 160; 171 |

| Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome21 |

| Mental retardation180 |

| Noonan syndrome113 |

| Primary megalencephaly80 |

| Psychomotor retardation171 |

| Schizophrenia171 |

| Sturge Weber syndrome202 |

| Teeth and jaw anomalies53 |

| Trisomy 15q214 |

| Tuberous sclerosis206 |

2.A. Retinitis pigmentosa

The association of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) with optic disc drusen has been known since the first case of optic disc drusen was published by Muller in 1858.130 The frequency of optic disc drusen in children with retinitis pigmentosa is not known. The largest study of optic disc drusen in patients with RP included both adults and children and found that 9.2% of patients with RP had optic disc drusen. The frequency of optic disc drusen in children was not reported separately, however, and because fundus photography was used, the authors may not have identified buried non-calcified drusen in children.71 Optic disc drusen are hypothesized to develop in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa as a result of retinal ganglion cell axonal degeneration.106; 126; 161 Degenerating axons extrude mitochondria, which become calcified and form drusen.204 Optic disc drusen have been associated with subtypes of retinitis pigmentosa including Usher syndrome and the syndrome of nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disc drusen.34; 41; 192 Genetic analysis has shown that a mutation in the Membrane-type Frizzled-related protein (MFRP) gene is responsible for some cases of the latter syndrome.8; 34; 147; 167; 209 More recently, a mutation in the crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1) gene has been reported in a family with nanophthalmos-retinitis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disc drusen syndrome who did not harbor a mutation in MFRP.155

2.B. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum and angioid streaks

Optic disc drusen have likewise been reported in association with pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) and angioid streaks.46; 116; 122; 157; 191 Reports of the incidence of optic disc drusen in pseudoxanthoma elasticum and angioid streaks are as high as 25%;122; 157; 191 however, the frequency of this association in children is not known. Many of the studies of optic disc drusen in PXE and angioid streaks did not include children and, in those that did, the findings in children were not separately reported. The cause of optic disc drusen in these disorders is postulated to be elastin mineralization in the lamina cribrosa from deposition of polyanions in the abnormal elastin fibrils. Calcium is believed to bind to these polyanions, resulting in the formation of macromolecules that disrupt axonal transport and lead to the formation of drusen.33; 89; 122 The gene responsible for the combination of optic disc drusen, angioid streaks, and pseudoxanthoma elasticum has yet to be elucidated.90

2.C. Alagille syndrome

Alagille syndrome has similarly been shown to be associated with optic disc drusen.42; 98; 150 This disorder is a form of familial intrahepatic cholestasis, with neonatal jaundice and paucity of intrahepatic bile ducts. Many ocular findings have been reported in association with Alagille syndrome, including posterior embryotoxon, pigmentary retinopathy, and optic disc drusen.150 Ultrasonographic evidence of optic disc drusen is found in at least one eye in 90% of children with Alagille syndrome and both eyes in 50%.150 The pathogenesis of optic disc drusen in Alagille syndrome is unclear. Eyes in Alagille syndrome have shorter than expected axial lengths, which could contribute to a small scleral canal with resultant axonal disruption and formation of optic disc drusen.150 Alagille syndrome is also associated with metabolic abnormalities that cause deposition of lipofuscin in the retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch membrane.87 These deposits may also disrupt axonal transport and contribute to drusen formation.150

3. Clinical findings

3.A. Symptoms

Patients with optic disc drusen are frequently asymptomatic, and optic disc drusen are often discovered incidentally on ophthalmologic examination. In children, ophthalmologic examination is prompted by a systemic symptom such as headache, vomiting, or seizure in 48% of patients. The remainder undergo examination for unrelated ocular issues such as strabismus, or as a part of routine screening.45 Children are less likely than adults to report symptoms attributable to optic disc drusen, such as transient visual obscurations182 and visual field defects (Figure 2).36; 119; 152

Figure 2.

Characteristic visual field defects in a patient with bilateral optic disc drusen. The left eye has a small inferonasal scotoma, and the right eye has a predominantly nasal inferior arcuate defect.

3.B. Visual field defects

Visual field defects are more common in superficial compared to buried drusen, and therefore visual field defects tend to increase in frequency with increasing age.138; 185 Erkkila found visual field defects in 10 of 89 eyes (11%) of children with optic disc drusen.45 The average age of patients in this study was 9.8 years. In a study of older children with optic disc drusen (mean age of 10.2 years at presentation, followed for an average of 44 months), Hoover et al found visual field defects in 18 of 35 eyes (51%).79 The authors reported that the average age at which visual field defects were detected was 14 years, while the mean age at which drusen became superficial and visible was 12.1 years.79

Noval et al studied 15 children with visual field defects from buried or superficial optic disc drusen and found that the most common visual field defect was a nasal inferior arcuate scotoma (32%), followed by unspecified nasal defect (21%), constricted visual field (21%), and enlarged blind spot (18%).152 Visual field constriction occurred in 50% of eyes with superficial drusen, compared to 17% of eyes with buried drusen.

Longitudinal studies of visual field defects in optic disc drusen suggest that progression is generally slow.109; 190 Shelton et al examined 23 eyes of 16 patients over a mean of 9.7 years and found the average change in mean deviation (MD) on Humphrey visual field (HVF) to be −0.78 dB, with the majority of eyes showing no clinically significant decrease in MD.190 Lee and Zimmerman followed 32 patients with optic disc drusen over 36 months and reported that the annual rate of visual field loss on Goldmann visual field (GVF) testing was 1.6%.109

3.C. Examination findings

Central visual acuity is typically unaffected by optic disc drusen.45; 119; 152 Patients may have an afferent pupillary defect if drusen are unilateral or asymmetric.36 The optic disc usually appears elevated, and there may be superficial or deep hemorrhages.45; 77; 119 The drusen are typically located nasally and cause a lumpy bumpy appearance if superficial. Buried drusen are difficult to appreciate on slit lamp examination, but may sometimes be seen adjacent to vessels or the disc margin with oblique illumination.36; 45; 171 Additionally, the retinal vasculature of eyes with optic disc drusen is frequently anomalous.49 In children, optic disc drusen are associated with a cilioretinal artery in 43% of eyes, optociliary shunt vessels in 4%, and more vascular tortuosity and early branching of vessels compared to control eyes.44; 45

3.D. Distinguishing from true optic disc edema by funduscopy

When optic disc drusen are suspected, it is imperative to rule out true optic disc edema, which is distinguished from drusen on examination by obscuration of peripapillary vessels, hyperemia, hemorrhages, cotton wool spots, Paton lines, and exudates around the optic disc.36; 77 In many cases, however, it may be difficult to distinguish between optic disc drusen and true mild disc edema based on clinical examination alone, particularly when drusen are buried (Figure 1). In these cases, ancillary testing can be helpful.

4. Diagnostic testing

Various ancillary tests, including B-scan ultrasonography,55; 105; 151; 168 fundus autofluorescence,95; 140; 145 orbital computed tomography (CT) scan,12; 131; 162 fluorescein angiography (FA),24; 159; 177 scanning laser ophthalmoscopy,75; 103; 187 electrophysiology,17; 18; 23; 142; 186 and more recently optical coherence tomography (OCT),31; 88; 112; 125; 215 have been used to identify optic disc drusen. These tests may be less useful in children who typically have buried drusen that are more difficult to detect.

4.A. B-scan ultrasonography

B-scan ultrasonography is considered the gold standard imaging modality to detect optic disc drusen.7; 55; 105; 151 Drusen characteristically appear hyperechoic with posterior shadowing on ultrasonography (Figure 3). The B scan is able to scan the entire area of the optic disc using sweeping movements of the ultrasound probe. In a study of children and adults comparing B-scan ultrasonography, preinjection control photography for detection of autofluorescence, and orbital CT scan, B-scan ultrasonography detected significantly more cases of optic disc drusen,105 but identified only 39 of 82 cases (48%) of suspected buried optic disc drusen. This is likely because the undetected drusen were not calcified.6 Because optic disc drusen in children are more frequently non-calcified and buried,57; 79; 196 the sensitivity of ultrasound for diagnosis of drusen in children may be lower than in adults, and ultrasonography may become positive over time as drusen become calcified.156 Petrushkin et al described five children who had optic disc drusen not seen on B-scan ultrasonography at presentation whose drusen later became detectable by ultrasonography at a mean age of 8.8 years.156

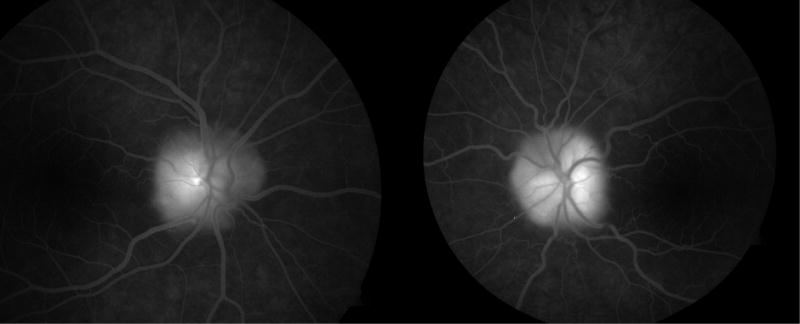

Figure 3.

Appearance of calcified optic disc drusen on ultrasonography. The calcified drusen produce a hyperechoic signal at the optic disc with posterior shadowing.

4.B. Fundus autofluorescence

Optic disc drusen display autofluorescence and can therefore be detected on preinjection control photography (Figure 4B) and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy.39; 95; 105; 140; 145 Autofluorescence, however, does not reliably detect buried drusen, possibly because of attenuation from overlying tissue.105; 140 Kurz-Levin et al found that autofluorescence detected over 96% of superficial drusen but only 27% of buried drusen in a study including both adults and children.105 In contrast, in a study of 24 children with optic disc drusen, Gili et al reported that autofluorescence was able to detect drusen in 94% of cases.63 The presence of drusen, however, was established by B-scan ultrasonography, which does not reliably detect non-calcified drusen. Therefore, the usefulness of autofluorescence in identifying optic disc drusen in children, who are more likely to harbor non-calcified buried drusen, has not been conclusively determined.

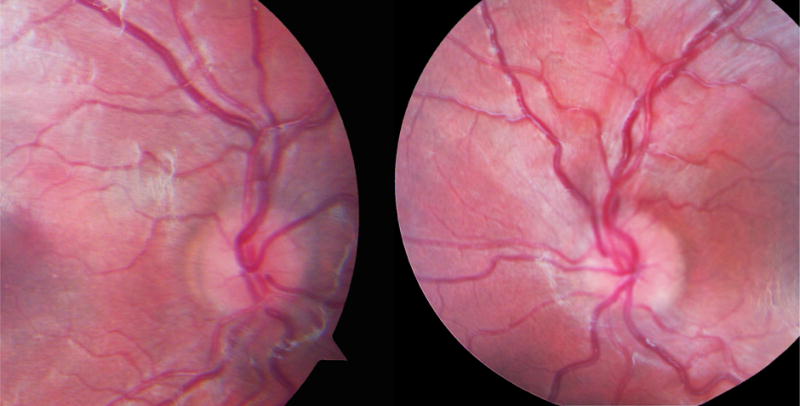

Figure 4.

Fundus photography, autofluorescence, and fluorescein angiography in a 12 year old girl with optic disc drusen. A) Color fundus photography demonstrates blurred disc margins and superficial gliosis. B) Preinjection control photography shows hyperautofluorescence of optic disc drusen bilaterally. C) Late phase fluorescein angiography demonstrates nodular staining of the optic discs with no leakage.

4.C. Orbital computed tomography (CT)

Orbital CT has also been used to image optic disc drusen.12; 82; 105; 131; 162; 217 Like B-scan ultrasonography, CT detects calcification of drusen. It is limited by the 1.5 mm thickness of slices, which may miss drusen, and has been shown to be inferior to ultrasonography.105 Given the concerns regarding excess radiation in children, and the low sensitivity of CT scans for detecting optic disc drusen, we do not recommend ordering CT scans in children for this purpose.

4.D. Fluorescein angiography (FA)

Fluorescein angiographic characteristics of eyes in children with optic disc drusen include optic disc staining159 and delayed filling of the peripapillary choriocapillaris in 43% of cases.44; 45 Fluorescein angiography may be used to distinguish between optic disc drusen and true optic disc edema.24; 140; 159; 177 Pineles and Arnold found that true disc edema was characterized by early or late disc leakage, while optic disc drusen displayed staining without leakage.159 Superficial optic disc drusen demonstrated early and late nodular disc staining in 90% of cases, while buried drusen showed early nodular staining in 25% and late nodular staining in 29% (Figure 4C).159 Their study included both children and adults, with a mean age of 36 years. The above results suggest that fluorescein angiography in children may not reliably detect nodular staining by buried drusen, but may be helpful to rule out true disc edema.

In younger children, intravenous fluorescein angiography (IVFA) may not be possible because of intolerance of venipuncture. In such cases, oral fluorescein angiography (oral FA) may be considered.60; 144 The role of oral FA for distinguishing between pseudopapilledema and true optic disc edema in children is unclear. Young patients who cannot tolerate venipuncture may also be unable to cooperate with image capture during oral FA.144 Moreover, the sensitivity of oral FA may be less than IVFA for detection of optic disc edema. Ghose and Nayak performed oral FA in 30 eyes with suspected papilledema and 16 eyes with pseudopapilledema in children aged 1 month to 10 years.60 The optic disc in eyes with suspected pseudopapilledema showed similar findings to normal children, with fluorescence of the optic disc at 30 minutes that nearly disappeared by 60 minutes post-injection. Of 30 eyes with suspected papilledema, only 12 (40%) showed positive findings on oral FA, defined as focal or diffuse late disc hyperfluorescence at 60 minutes.

4.E. Optical coherence tomography (OCT)

A relatively new modality for imaging optic disc drusen is optical coherence tomography (OCT).5; 31; 50; 76; 88; 93; 104; 112; 114; 135; 195; 211; 215 On OCT, optic disc drusen can be seen as a focal hyperreflective mass posterior to the outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers, with absence of the inner and outer segment photoreceptor junction (Figure 5);112 however, Kulkarni et al found standard spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) to be unreliable at distinguishing between buried optic disc drusen and true optic disc edema in children and young adults.104 They noted that, in several cases of mild disc edema, OCT showed nonspecific hyperreflective areas underneath the optic nerve that were confused with drusen.

Figure 5.

Optical coherence tomography of optic disc demonstrating drusen. The drusen appear as hyperreflective masses posterior to the outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers, with loss of the inner and outer segment photoreceptor junction.

4.F. Retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) analysis

Investigators have also used OCT, as well as scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and fundus photography, to examine the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in patients with optic disc drusen.16; 32; 48; 62; 74; 88; 92; 103; 141; 153; 154; 158; 170; 201 In a study of OCT RNFL in children with optic disc drusen, Noval et al found the RNFL thickness to be higher than controls in eyes with partially or completely buried drusen and lower than controls in eyes with superficial drusen.152 The RNFL defect is typically nasal, with sparing of the temporal RNFL.62 A new OCT parameter, macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL) thickness, may show thinning earlier than the RNFL in buried optic disc drusen in both children and adults.25; 163 Some authors have sought to use OCT RNFL thickness to distinguish between optic disc drusen and true disc edema, in which RNFL thickness may be higher, especially nasally;11; 88; 181 however, the degree of RNFL thickening in true disc edema may depend on the severity of edema, and thickness may not differ significantly between mild optic disc edema and pseudopapilledema.92

4.G. Enhanced-depth imaging OCT (EDI-OCT) and swept-source OCT (SS-OCT)

Enhanced-depth imaging OCT (EDI-OCT) and swept-source OCT (SS-OCT), which image more posteriorly than standard SD-OCT, have shown promise in detecting optic disc drusen.125; 183; 194 Merchant et al examined 32 eyes with clinically definite optic disc drusen and 25 eyes with suspected optic disc drusen in children and adults.125 They found that B-scan ultrasonography, SD-OCT, and EDI-OCT all detected every case of clinically definite optic disc drusen; however, in 25 eyes with suspected buried optic disc drusen, EDI-OCT detected 17 cases, while SD-OCT and B-scan ultrasonography were positive in 14 and 7 eyes, respectively. EDI-OCT was significantly better than B-scan ultrasonography at identifying buried drusen.

4.H. Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological testing has also been performed in both adults and children with optic disc drusen, and abnormalities are thought to be related to the degree of nerve fiber layer damage.7 Scholl et al performed pattern electroretinogram (pERG) testing on 24 eyes with optic disc drusen and reported P50 amplitude reduction in 17% of eyes and reduction or absence of the N95 component in 79% of eyes.186 Multiple investigators have studied visual evoked responses in eyes with optic disc drusen, and the results have been mixed, with P100 latency prolongation reported in 0 to 83% of eyes.17; 18; 23; 121; 142; 186; 208 Given the variability in these electrophysiological changes, as well as the difficulty of performing these tests in young children, they are not routinely ordered for diagnosis of optic disc drusen in children.

5. Complications

Although optic disc drusen are typically considered benign, they may be associated with various ocular complications in children.

5.A. Visual field defects

As discussed previously, visual field defects occur in up to 51% of children and become more common with increasing age.79; 138 The average age at which visual field defects are detected in children with optic disc drusen is 14 years.79 Visual field loss in patients with optic disc drusen may have a vascular etiology, as visual field defects correlate with lower systolic flow velocities in the central retinal artery in both adults and children with optic disc drusen.1

5.B. Hemorrhagic complications

Optic disc drusen are also associated with several hemorrhagic and vascular complications.73; 77; 110; 134; 173; 178; 179; 212 Peripapillary subretinal, retinal, and vitreous hemorrhages occur at a frequency of 2 to 13%.20; 49; 110 Sanders et al divided the hemorrhagic complications associated with optic disc drusen into three categories: small, superficial hemorrhages limited to the optic disc; large hemorrhages on the optic disc extending in the vitreous; and deep peripapillary hemorrhages extending from the optic disc under the surrounding retina.178 In their series of seven patients with hemorrhagic complications of optic disc drusen, Sanders et al included three children. One of these children had a disc hemorrhage leading to vitreous hemorrhage, whereas the other two had subretinal hemorrhage simulating choroidal malignant melanoma that resulted in enucleation in one case.178

5.C. Choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM)

Choroidal neovascular membrane formation is a complication of optic disc drusen that is thought to occur more frequently in children (Figure 6).3; 7; 22; 137; 184 Mustonen found two cases of choroidal neovascular membranes, both in children, in a series of 200 adults and children with optic disc drusen.137 The neovascular membrane is typically located in the peripapillary region and is frequently associated with good visual acuity without treatment.73 In some cases it can extend into the macula and fovea, causing vision loss via submacular fluid and/or hemorrhage.9; 99; 178; 184

Figure 6.

Regressed juxtapapillary choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to optic disc drusen, with subretinal fibrosis and pigment mottling (Courtesy of Anthony C. Arnold, MD).

5.D. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION)

Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) is the most common ischemic complication of optic disc drusen and has been postulated to be the most frequent cause of visual loss in this disorder.119 Compared to patients with classic NAION, patients who have optic disc drusen and develop NAION are typically younger (late teens to early twenties) without systemic risk factors.64; 148; 171 Patients with systemic risk factors may develop NAION at an unusually young age or have bilateral involvement. Nanji et al reported a case of NAION in a 12-year-old boy with optic disc drusen and cited travel to high altitude and dehydration from emesis as possible contributory factors.143 Choi et al described a 19-year-old male with bilateral optic disc drusen who developed bilateral NAION with visual field constriction.31 Systemic risk factors for NAION included a history of systemic hypotension and smoking, as well as dehydration while backpacking at an altitude of over 11,000 feet at the time of the ischemic events.

5.E. Retinal vascular occlusions

Case reports have also been published of central and branch retinal artery occlusion and central retinal vein occlusion in association with optic disc drusen.30; 47; 58; 61; 68; 78; 108 These retinal vascular occlusions occur at a younger age than is typical for these disorders in patients without optic disc drusen; the youngest reported patient developed a branch retinal artery occlusion at the age of 11 years.61 In most cases, patients with optic disc drusen who developed a retinal vascular occlusion at a young age also had another systemic risk factor, such as migraine, contraceptive use, systemic hypertension, atrioseptal defect, or travel to altitude.7

6. Treatment

6.A. Visual field defects

If true optic disc edema has been ruled out, patients with asymptomatic optic disc drusen may be observed with serial visual field testing. Because visual field defects occur in up to 51% of children with optic disc drusen,79; 119 regular visual field testing is important and should be performed as soon as children can do so reliably. In cases with progressive visual field defects, topical ocular hypotensive therapy may be initiated, although there have been no studies to evaluate the effectiveness of this therapy in children or adults.7; 70 The usual precautions when using ocular hypotensives in children apply. α-agonists should be used with caution in young children because of the risk of central nervous system depression, and β-blockers should be avoided in patients with respiratory disorders such as asthma. Surgical treatment of visual field defects due to optic disc drusen with optic nerve sheath fenestration or radial optic neurotomy is controversial and not considered standard of care, but success has been reported by a few authors.85; 86; 129; 146

6.B. Choroidal neovascular membranes

Optic disc drusen complicated by choroidal neovascular membranes can potentially be observed if they are asymptomatic and do not involve the macula. Successful treatment of optic disc drusen with CNVM has been reported with surgery,123; 200 laser photocoagulation,38 photodynamic therapy,29; 193 and more recently intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents.2; 9; 37; 69; 84; 99; 175 Both bevacizumab and ranibizumab have been used successfully in children with CNVM secondary to optic disc drusen as young as five years of age.9; 99 Although some clinicians use anti-VEGF agents to treat infants with retinopathy of prematurity, concerns still exist regarding the safety of these drugs, particularly bevacizumab, in the pediatric population.99 The long-term systemic effects on developing organs have yet to be determined, and they should be used with caution in children.

6.C. Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) and retinal vascular occlusions

Ischemic complications of optic disc drusen in children, including NAION and retinal vascular occlusions, should be managed as in the absence of drusen. In children with retinal vascular occlusions, consideration should be given to initiating a work-up for a secondary cause, such as hypercoagulability or atrioseptal defect, as these vascular occlusions are rare in children with optic disc drusen in the absence of a systemic risk factor.7; 47

7. Conclusions

Optic disc drusen in children are typically bilateral and are more likely to be buried than in adults. Thus, they may be difficult to distinguish from true optic disc edema, which mandates exploration for secondary causes of increased intracranial pressure, such as a mass lesion of the brain or pseudotumor cerebri syndrome. Ancillary testing, especially ultrasonography, fluorescein angiography, fundus autofluorescence, and optical coherence tomography, may be helpful in distinguishing between optic disc drusen and true disc edema, although these tests may be less sensitive for detecting buried drusen in children. It is important to consider optic disc drusen in the differential for papilledema, as 50 to 55% of children initially diagnosed with papilledema have optic disc drusen as their final diagnosis.101; 117 If optic disc drusen are correctly diagnosed initially, patients may avoid unnecessary further work-up and expense. Leon et al reported that in children ultimately diagnosed with optic disc drusen, when an ultrasound was ordered as the initial test, the cost of evaluation was $305, compared to $1,173 when neuroimaging was ordered first.115 The presence of optic disc drusen, however, does not exclude true disc edema, and optic disc drusen occur simultaneously with true disc edema in some children.67; 100; 172 Therefore, in patients with signs or symptoms suspicious for another disorder, further evaluation may be necessary even if optic disc drusen are detected.

Complications of optic disc drusen include visual field defects in up to 51% of children, and less commonly hemorrhages, choroidal neovascular membrane, non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and retinal vascular occlusions. Consideration may be given to initiating ocular hypotensive therapy in patients with progressive visual field defects secondary to optic disc drusen, although α-agonists and β-blockers should be used with caution in children. Choroidal neovascular membranes complicated by submacular hemorrhage and/or fluid with decreased visual acuity may be treated with intravitreal anti-VEGF agents. Both bevacizumab and ranibizumab have been successfully used in children, although the long-term systemic effects of these drugs in the pediatric population have yet to be elucidated. In most cases, children with optic disc drusen can be managed by observation with serial examinations and visual field testing, once true optic disc edema has been excluded.

Methods of literature search

A search of the MEDLINE database was conducted during December 2015 using the following key words: optic disc and drusen and child; optic disc and drusen and children; optic disc and drusen and pediatric; optic disk and drusen and child; optic disk and drusen and children; optic disk and drusen and pediatric; optic nerve and drusen and child; optic nerve and drusen and children; and optic nerve and drusen and pediatric. The search covered all published literature through December 2015. The bibliographies of key articles were also hand-searched to identify further references. References spanned the period from 1858 to December 2015. All articles judged to be of clinical importance were included. The review was limited to peer-reviewed papers published in English. Abstracts of articles in other languages were included if the abstracts were published in English. Search results were collected and abstracts screened to remove any articles not relevant to the topic. The total number of references for this review is 217.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

MYC – none

SLP – Funding sources: NIH/NEI K23EY021762l; Research to Prevent Blindness Walt and Lily Disney Award for Amblyopia Research; Knights Templar Eye Foundation; Oppenheimer Family Foundation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abegao Pinto L, Vandewalle E, Marques-Neves C, Stalmans I. Visual field loss in optic disc drusen patients correlates with central retinal artery blood velocity patterns. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(4):e286–291. doi: 10.1111/aos.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkin Z, Ozkaya A, Yilmaz I, Yazici AT. A single injection of intravitreal ranibizumab in the treatment of choroidal neovascularisation secondary to optic nerve head drusen in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CJ, Zauel DW, Schlaeger TF, Meyer SM. Bilateral juxtapapillary subretinal neovascularization and pseudopapilledema in a three-year-old child. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1978;15(5):296–299. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19780901-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antcliff RJ, Spalton DJ. Are optic disc drusen inherited? Ophthalmology. 1999;106(7):1278–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asensio-Sanchez VM, Trujillo-Guzman L. SD-OCT to distinguish papilledema from pseudopapilledema. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2015;90(10):481–483. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atta HR. Imaging of the optic nerve with standardised echography. Eye. 1988;2(4):358–366. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auw-Haedrich C, Staubach F, Witschel H. Optic disk drusen. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(6):515–532. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala-Ramirez R, Graue-Wiechers F, Robredo V, et al. A new autosomal recessive syndrome consisting of posterior microphthalmos, retinitis pigmentosa, foveoschisis, and optic disc drusen is caused by a MFRP gene mutation. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baillif S, Nguyen E, Colleville-El Hayek A, Betis F. Long term follow-up after a single intravitreal ranibizumab injection for choroidal neovascularisation secondary to optic nerve head drusen in a 5-year-old child. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(6):1657–1659. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barteselli G, Dell’arti L, Finger RP, et al. The spectrum of ocular alterations in patients with beta-thalassemia syndromes suggests a pathology similar to pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(3):709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassi ST, Mohana KP. Optical coherence tomography in papilledema and pseudopapilledema with and without optic nerve head drusen. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(12):1146–1151. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.149136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bec P, Adam P, Mathis A, et al. Optic nerve head drusen. High-resolution computed tomographic approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102(5):680–682. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030536010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bella L, Faivre M, Mercier-Tacheix V, et al. Optic disk drusen and intracranial tumor. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1990;90(6–7):699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Zur PH, Lieberman TW. Drusen of the optic nerves and meningioma: a case report. Mt Sinai J Med. 1972;39(2):188–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson WE, Kolker AE, Enoch JM, et al. Best’s vitelliform macular dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernardczyk-Meller J, Wasilewicz R, Pecold-Stepniewska H, Wasiewicz-Rager J. OCT and PVEP examination in eyes with visible idiopathic optic disc drusen. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2006;223(12):993–996. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-927155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishara S, Feinsod M. Visual evoked response as an aid in diagnosing optic nerve head drusen: case report. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980;17(6):396–398. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19801101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishara S, Zelikowitch A. Pulfrich’s phenomenon and drusen of optic nerve head. Ann Ophthalmol. 1984;16(1):27–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boldt HC, Byrne SF, DiBernardo C. Echographic evaluation of optic disc drusen. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1991;11(2):85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borruat FX, Sanders MD. Vascular anomalies and complications of optic nerve drusen. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1996;208(5):294–296. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1035219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bothun ED, Kao T, Guo Y, Christiansen SP. Bilateral optic nerve drusen and gliomas in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J AAPOS. 2011;15(1):77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown SM, Del Monte MA. Choroidal neovascular membrane associated with optic nerve head drusen in a child. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(2):215–217. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brudet-Wickel CL, Van Lith GH, Graniewski-Wijnands HS. Drusen of the optic disc and occipital transient pattern reversal responses. Doc Ophthalmol. 1981;50(2):243–248. doi: 10.1007/BF00158005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cartlidge NE, Ng RC, Tilley PJ. Dilemma of the swollen optic disc: a fluorescein retinal angiography study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61(6):385–389. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.6.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casado A, Rebolleda G, Guerrero L, et al. Measurement of retinal nerve fiber layer and macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with optic nerve head drusen. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(10):1653–1660. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2773-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavazza S, Molinari PP. Bilateral intermediate uveitis and acute interstitial nephritis (TINU syndrome). Ultrasonographic documentation of a case. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1994;17(1):59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers JW, Walsh FB. Hyaline bodies in the optic discs: report of ten cases exemplifying importance in neurological diagnosis. Brain. 1951;74(1):95–108. doi: 10.1093/brain/74.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang YC, Tsai RK. Coexistence of optic nerve head drusen and combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium in a Taiwanese male. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaudhry NA, Lavaque AJ, Shah A, Liggett PE. Photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascular membrane secondary to optic nerve drusen. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2005;36(1):70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chern S, Magargal LE, Annesley WH. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with drusen of the optic disc. Ann Ophthalmol. 1991;23(2):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi SS, Zawadzki RJ, Greiner MA, et al. Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography and adaptive optics reveal nerve fiber layer loss and photoreceptor changes in a patient with optic nerve drusen. J Neuroophthalmol. 2008;28(2):120–125. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318175c6f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chrzanowska B, Szuminski M, Bakunowicz-Lazarczyk A. Optic nerve head drusen in children–visual function and OCT outcomes. Klin Oczna. 2012;114(4):274–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman K, Ross MH, Mc Cabe M, et al. Disk drusen and angioid streaks in pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(2):166–170. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crespi J, Buil JA, Bassaganyas F, et al. A novel mutation confirms MFRP as the gene causing the syndrome of nanophthalmos-renititis pigmentosa-foveoschisis-optic disk drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(2):323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunningham RD, Sewell JJ. Aneurysm of the ophthalmic artery with drusen of the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72(4):743–745. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis PL, Jay WM. Optic nerve head drusen. Semin Ophthalmol. 2003;18(4):222–242. doi: 10.1080/08820530390895244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delas B, Almudi L, Carreras A, Asaad M. Bilateral choroidal neovascularization associated with optic nerve head drusen treated by antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:225–230. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S22991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delyfer MN, Rougier MB, Fourmaux E, et al. Laser photocoagulation for choroidal neovascular membrane associated with optic disc drusen. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2004;82(2):236–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinc UA, T S, Gorgun E, Yenerel M. Fundus Autofluorescence in Optic Disc Drusen: Comparison of Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscope and Standard Fundus Camera. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2009;33(6):318–321. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duval R, Hammamji K, Aroichane M, et al. Acquired myelinated nerve fibers in association with optic disk drusen. J AAPOS. 2010;14(6):544–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards A, Grover S, Fishman GA. Frequency of photographically apparent optic disc and parapapillary nerve fiber layer drusen in Usher syndrome. Retina. 1996;16(5):388–392. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199616050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Koofy NM, El-Mahdy R, Fahmy ME, et al. Alagille syndrome: clinical and ocular pathognomonic features. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(2):199–206. doi: 10.5301/ejo.2010.5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erkkila H. Clinical appearance of optic disc drusen in childhood. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975;193(1):1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00410523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erkkila H. The central vascular pattern of the eyeground in children with drusen of the optic disk. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1976;199(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00660810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erkkila H. Optic disc drusen in children. Acta Ophthalmol. 1977;55(Suppl 129):7–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erkkila H, Raitta C, Niemi KM. Ocular findings in four siblings with pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61(4):589–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb04349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farah SG, Mansour AM. Central retinal artery occlusion and optic disc drusen. Eye. 1998;12(3a):480–482. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fard MA, Fakhree S, Abdi P, et al. Quantification of peripapillary total retinal volume in pseudopapilledema and mild papilledema using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flores-Rodriguez P, Gili P, Martin-Rios MD. Ophthalmic features of optic disc drusen. Ophthalmologica. 2012;228(1):59–66. doi: 10.1159/000337842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flores-Rodriguez P, Gili P, Martin-Rios MD. Sensitivity and specificity of time-domain and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in differentiating optic nerve head drusen and optic disc oedema. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32(3):213–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2012.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Floyd MS, Katz BJ, Digre KB. Measurement of the scleral canal using optical coherence tomography in patients with optic nerve drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(4):664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fong CY, Williams C, Pople IK, Jardine PE. Optic disc drusen masquerading as papilloedema. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(8):629. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.186122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fotzsch R. Problems in the etiology, pathogenesis and clinical significance of drusen (hyalin bodies) of the optic disk. Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) 1970;22(6):223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedburg D. Pseudoneuritis and drusen of the optic disk in Alport’s syndrome. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1968;152(3):379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman AH, Beckerman B, Gold DH, et al. Drusen of the optic disc. Surv Ophthalmol. 1977;21(5):373–390. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(77)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedman AH, Henkind P, Gartner S. Drusen of the optic disc. A histopathological study. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975;95(1):4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frisen L. Evolution of drusen of the optic nerve head over 23 years. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(1):111–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gallagher MJ, Clearkin LG. Drug or drusen? Central retinal vein occlusion in a young healthy woman with disc drusen. Eye. 2000;14(3a):401–402. doi: 10.1038/eye.2000.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghanchi F, Ramsay A, Coupland S, et al. Ocular tumoral calcinosis. A clinicopathologic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(3):341–345. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130337022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ghose S, Nayak BK. Role of oral fluorescein in the diagnosis of early papilloedema in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71(12):910–915. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.12.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gifford H. An unusual case of hyaline bodies in the optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol. 1895;24:395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gili P, Flores-Rodriguez P, Martin-Rios MD, Carrasco Font C. Anatomical and functional impairment of the nerve fiber layer in patients with optic nerve head drusen. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(10):2421–2428. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gili P, Flores-Rodriguez P, Yanguela J, Herreros Fernandez ML. Using autofluorescence to detect optic nerve head drusen in children. J AAPOS. 2013;17(6):568–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gittinger JW, Jr, Lessell S, Bondar RL. Ischemic optic neuropathy associated with optic disc drusen. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1984;4(2):79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giuffre G. Optic disc drusen in tilted disc. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2005;15(5):647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goel N, Jain P, Arora S, Ghosh B. Gyrate atrophy of the choroid and retina with cystoid macular edema and unilateral optic disc drusen. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015;52(1):64. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20141230-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Granger RH, Bonnelame T, Daubenton J, et al. Optic nerve head drusen and idiopathic intracranial hypertension in a 14-year-old girl. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46(4):238–240. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090706-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Green WR, Chan CC, Hutchins GM, Terry JM. Central retinal vein occlusion: a prospective histopathologic study of 29 eyes in 28 cases. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:371–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gregory-Evans K, Rai P, Patterson J. Successful Treatment of Subretinal Neovascularization with Intravitreal Ranibizumab in a Child with Optic Nerve Head Drusen. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009 doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090818-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grippo TM, Shihadeh WA, Schargus M, et al. Optic nerve head drusen and visual field loss in normotensive and hypertensive eyes. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(2):100–104. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31814b995a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grover S, Fishman GA, Brown J., Jr Frequency of optic disc or parapapillary nerve fiber layer drusen in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(2):295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gupta R, Singh S, Tang RA, Blackwell TA. Valsalva retinopathy and optic nerve drusen in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Am J Med. 2002;112(3):246–247. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00956-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harris MJ, Fine SL, Owens SL. Hemorrhagic complications of optic nerve drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)75910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hassan A, Gouws P. Optical coherence tomography demonstrating macular retinal nerve fiber thinning in advanced optic disc drusen. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2014;7(2):84–86. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.137167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haynes RJ, Manivannan A, Walker S, et al. Imaging of optic nerve head drusen with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(8):654–657. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.8.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heidary G, Rizzo JF., 3rd Use of optical coherence tomography to evaluate papilledema and pseudopapilledema. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(5–6):198–205. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.518462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hitchings RA, Corbett JJ, Winkleman J, Schatz NJ. Hemorrhages with optic nerve drusen. A differentiation from early papilledema. Arch Neurol. 1976;33(10):675–677. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1976.00500100009005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Honkanen RA, Baba FE, Sibony P, Prabhu SP. Ischemic central retinal vein occlusion and neovascular glaucoma as a result of optic nerve head drusen. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2011;5(1):73–75. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181c33375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoover DL, Robb RM, Petersen RA. Optic disc drusen in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1988;25(4):191–195. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19880701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoover DL, Robb RM, Petersen RA. Optic disc drusen and primary megalencephaly in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1989;26(2):81–85. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19890301-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu K, Davis A, O’Sullivan E. Distinguishing optic disc drusen from papilloedema. BMJ. 2008;337:a2360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Irnberger T. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of drusen of the optic papilla with special reference to computed tomography. Rofo. 1984;141(2):136–139. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1053103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jean-Louis G, Katz BJ, Digre KB, et al. Acquired and progressive retinal nerve fiber layer myelination in an adolescent. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(3):361–362. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jedrzejczak-Strozniak M, Siwiec-Proscinska J, Gotz-Wieckowska A, Kociecki J. Unilateral extrafoveal choroidal neovascularization in a 13-year-old child with bilateral optic nerve drusen. Klin Oczna. 2013;115(3):230–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jiraskova N, Rozsival P. Decompression of the optic nerve sheath–results in the first 37 operated eyes. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 1996;52(5):297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jiraskova N, Rozsival P. Results of 62 optic nerve sheath decompressions. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 1999;55(3):136–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnson BL. Ocular pathologic features of arteriohepatic dysplasia (Alagille’s syndrome) Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(5):504–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Johnson LN, Diehl ML, Hamm CW, et al. Differentiating optic disc edema from optic nerve head drusen on optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(1):45–49. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kadayifcilar S, Tatlipinar S, Erdener U, Eldem B. Optic disc drusen associated with angioid streaks. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2001;25(3):164–167. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaimbo DK, Mutosh A, Leys A, et al. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum: clinical, histologic, and genetic studies–a report of two sisters. Skinmed. 2011;9(2):119–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kamoun R, Mili Boussen I, Beltaief O, Ouertani A. Drusen in children: three case studies. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2008;31(1):e1. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(08)70333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Karam EZ, Hedges TR. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fibre layer in mild papilloedema and pseudopapilloedema. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(3):294–298. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.049486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kardon R. Optical coherence tomography in papilledema: what am I missing? J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34(Suppl):S10–17. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Katz B, Van Patten P, Rothrock JF, Katzman R. Optic nerve head drusen and pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(1):45–47. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520250051020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kelley JS. Autofluorescence of drusen of the optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;92(3):263–264. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1974.01010010271022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Khairallah M. Familial macular dystrophy of polymorphic aspect associated with optic nerve drusen. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1997;20(9):650–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kiegler HR. Comparison of functional findings with results of standardized echography of the optic nerve in optic disk drusen. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1995;107(21):651–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim BJ, Fulton AB. The genetics and ocular findings of Alagille syndrome. Semin Ophthalmol. 2007;22(4):205–210. doi: 10.1080/08820530701745108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Knape RM, Zavaleta EM, Clark CL, 3rd, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab treatment of bilateral peripapillary choroidal neovascularization from optic nerve head drusen. J AAPOS. 2011;15(1):87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Komur M, Sari A, Okuyaz C. Simultaneous papilledema and optic disc drusen in a child. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(3):187–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kovarik JJ, Doshi PN, Collinge JE, Plager DA. Outcome of pediatric patients referred for papilledema. J AAPOS. 2015;19(4):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Krasnitz I, Beiran I, Mezer E, Miller B. Coexistence of optic nerve head drusen and pseudotumor cerebri: a clinical dilemma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1997;7(4):383–386. doi: 10.1177/112067219700700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kuchenbecker J, Wecke T, Vorwerk CK, Behrens-Baumann W. Quantitative and objective topometrical analysis of drusen of the optic nerve head with the Heidelberg retina tomograph (HRT) Ophthalmologe. 2002;99(10):768–773. doi: 10.1007/s00347-002-0639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kulkarni KM, Pasol J, Rosa PR, Lam BL. Differentiating mild papilledema and buried optic nerve head drusen using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(4):959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kurz-Levin MM, Landau K. A comparison of imaging techniques for diagnosing drusen of the optic nerve head. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(8):1045–1049. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.8.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lam BL, Morais CG, Jr, Pasol J. Drusen of the optic disc. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(5):404–408. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lascaratos G, Lam WW, Newman WD, MacRae M. Adams-Oliver syndrome associated with bilateral anterior polar cataracts and optic disk drusen. J AAPOS. 2011;15(3):299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Law DZ, Yang FP, Teoh SC. Case report of optic disc drusen with simultaneous peripapillary subretinal hemorrhage and central retinal vein occlusion. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2014;2014:156178. doi: 10.1155/2014/156178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee AG, Zimmerman MB. The rate of visual field loss in optic nerve head drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(6):1062–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee KM, Hwang JM, Woo SJ. Hemorrhagic complications of optic nerve head drusen on spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2014;34(6):1142–1148. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee KM, Hwang JM, Woo SJ. Optic disc drusen associated with optic nerve tumors. Optom Vis Sci. 2015;92(4S):S67–75. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee KM, Woo SJ, Hwang JM. Differentiation of optic nerve head drusen and optic disc edema with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(5):971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lee NB, Kelly L, Sharland M. Ocular manifestations of Noonan syndrome. Eye. 1992;6(3):328–334. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lefrancois A, Barrault O, Parc C, et al. Optic disk drusen: what are the advantages of the new imaging techniques? J Fr Ophtalmol. 2003;26(Spec No 2):S23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Leon M, Hutchinson AK, Lenhart PD, Lambert SR. The cost-effectiveness of different strategies to evaluate optic disk drusen in children. J AAPOS. 2014;18(5):449–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li Volti S, Avitabile T, Li Volti G, et al. Optic disc drusen, angioid streaks, and mottled fundus in various combinations in a Sicilian family. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240(9):771–776. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu B, Murphy RK, Mercer D, et al. Pseudopapilledema and association with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30(7):1197–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00381-014-2390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lorentzen SE. Drusen of the optic disk, an irregularly dominant hereditary affection. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1961;39:626–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1961.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lorentzen SE. Drusen of the optic disk. A clinical and genetic study. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1966;44(Suppl 90):1–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lowder CY, Tomsak RL, Zakov ZN, Hahn J. Visual loss from pituitary tumor masked by optic nerve drusen. Neurosurgery. 1981;8(4):473–476. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lowitzsch K, Neuhann T. Pattern-reversal-VEP in the diagnosis of drusen and papilledema. Fortschr Ophthalmol. 1983;79(6):509–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mansour AM. Is there an association between optic disc drusen and angioid streaks? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1992;230(6):595–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00181785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mateo C, Moreno JG, Lechuga M, et al. Surgical removal of peripapillary choroidal neovascularization associated with optic nerve drusen. Retina. 2004;24(5):739–745. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200410000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mehta P, Puri P, Talbot JF. Disc drusen and peripapillary subretinal neovascular membrane in a child with the VACTERL association. Eye. 2006;20(7):847–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Merchant KY, Su D, Park SC, et al. Enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography of optic nerve head drusen. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1409–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Milam AH, Li ZY, Fariss RN. Histopathology of the human retina in retinitis pigmentosa. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17(2):175–205. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(97)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mishra A, Mordekar SR, Rennie IG, Baxter PS. False diagnosis of papilloedema and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11(1):39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Moisseiev J, Cahane M, Treister G. Optic nerve head drusen and peripapillary central serous chorioretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108(2):202–203. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Moreau A, Lao KC, Farris BK. Optic nerve sheath decompression: a surgical technique with minimal operative complications. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34(1):34–38. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Muller H. Anatomische Beiträge zur Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Klin Ophthalmol. 1858;4:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mullie MA, Sanders MD. Computed tomographic diagnosis of buried drusen of the optic nerve head. Can J Ophthalmol. 1985;20(3):114–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mullie MA, Sanders MD. Scleral canal size and optic nerve head drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(3):356–359. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Munteanu G, Munteanu M, Zolog I, Giuri S. Idiopatic parafoveolar telangiectasia associated with pseudoviteliform lesion, basal laminar drusen and optic nerve head drusen. Oftalmologia. 2010;54(2):79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Munteanu M. Hemorrhagic complications of drusen of the optic disk. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(07)89552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Murthy RK, Storm L, Grover S, et al. In-vivo high resolution imaging of optic nerve head drusen using spectral-domain Optical Coherence Tomography. BMC Med Imaging. 2010;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mustonen E. Optic disc drusen and tumours of the chiasmal region. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1977;55(2):191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1977.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mustonen E. Pseudopapilloedema with and without verified optic disc drusen. A clinical analysis I. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61(6):1037–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Mustonen E. Pseudopapilloedema with and without verified optic disc drusen. A clinical analysis II: visual fields. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1983;61(6):1057–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1983.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mustonen E, Kallanranta T, Toivakka E. Neurological findings in patients with pseudopapilloedema with and without verified optic disc drusen. Acta Neurol Scand. 1983;68(4):218–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Mustonen E, Nieminen H. Optic disc drusen–a photographic study. I. Autofluorescence pictures and fluorescein angiography. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60(6):849–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Mustonen E, Nieminen H. Optic disc drusen–a photographic study. II. Retinal nerve fibre layer photography. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60(6):859–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mustonen E, Sulg I, Kallanranta T. Electroretinogram (ERG) and visual evoked response (VER) studies in patients with optic disc drusen. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1980;58(4):539–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb08295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nanji AA, Klein KS, Pelak VS, Repka MX. Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a child with optic disk drusen. J AAPOS. 2012;16(2):207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Nayak BK, Ghose S. A method for fundus evaluation in children with oral fluorescein. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71(12):907–909. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.12.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Neetens A, Burvenich H. Autofluorescence of optic disc-drusen. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol. 1977;179:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nentwich MM, Remy M, Haritoglou C, Kampik A. Radial optic neurotomy to treat patients with visual field defects associated with optic nerve drusen. Retina. 2011;31(3):612–615. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318209b748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Neri A, Leaci R, Zenteno JC, et al. Membrane frizzled-related protein gene-related ophthalmological syndrome: 30-month follow-up of a sporadic case and review of genotype-phenotype correlation in the literature. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2623–2632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Newman WD, Dorrell ED. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with disc drusen. J Neuroophthalmol. 1996;16(1):7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Newsome DA, Anderson RE, May JG, et al. Clinical and serum lipid findings in a large family with autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(12):1691–1695. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)32950-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Nischal KK, Hingorani M, Bentley CR, et al. Ocular ultrasound in Alagille syndrome: a new sign. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Noel LP, Clarke WN, MacInnis BJ. Detection of drusen of the optic disc in children by B-scan ultrasonography. Can J Ophthalmol. 1983;18(6):266–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Noval S, Visa J, Contreras I. Visual field defects due to optic disk drusen in children. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(10):2445–2450. doi: 10.1007/s00417-013-2384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ocakoglu O, Ustundag C, Koyluoglu N, et al. Long term follow-up of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in eyes with optic nerve head drusen. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26(5):277–280. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.4.277.15428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Patel NN, Shulman JP, Chin KJ, Finger PT. Optical coherence tomography/scanning laser ophthalmoscopy imaging of optic nerve head drusen. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41(6):614–621. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20100929-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Paun CC, Pijl BJ, Siemiatkowska AM, et al. A novel crumbs homolog 1 mutation in a family with retinitis pigmentosa, nanophthalmos, and optic disc drusen. Mol Vis. 2012;18:2447–2453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Petrushkin H, Ali N, Restori M, Adams GG. Development of optic disc drusen in familial pseudopapilloedema: a paediatric case series. Eye. 2011;25(8):1101–1102. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Pierro L, Brancato R, Minicucci M, Pece A. Echographic diagnosis of drusen of the optic nerve head in patients with angioid streaks. Ophthalmologica. 1994;208(5):239–242. doi: 10.1159/000310498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Pilat AV, Proudlock FA, Kumar P, et al. Macular morphology in patients with optic nerve head drusen and optic disc edema. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(2):552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Pineles SL, Arnold AC. Fluorescein angiographic identification of optic disc drusen with and without optic disc edema. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(1):17–22. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31823010b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Pollack IP, Becker B. Hyaline bodies (drusen) of the optic nerve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1962;54:651–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Puck A, Tso MO, Fishman GA. Drusen of the optic nerve associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(2):231–234. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050020083027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Ramirez H, Blatt ES, Hibri NS. Computed tomographic identification of calcified optic nerve drusen. Radiology. 1983;148(1):137–139. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.1.6856823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Rebolleda G, Diez-Alvarez L, Casado A, et al. OCT: New perspectives in neuro-ophthalmology. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29(1):9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Reddy RK, Sundaram PM, Shetty S, Choudhari NS. Optic nerve head drusen in an eye with morning glory disc anomaly. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(7):1111–1112. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Reeser FH, Aaberg TM, Van Horn DL. Astrocytic hamartoma of the retina not associated with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;86(5):688–698. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(78)90192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Reifler DM, Kaufman DI. Optic disk drusen and pseudotumor cerebri. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(1):95–96. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ritter M, Vodopiutz J, Lechner S, et al. Coexistence of KCNV2 associated cone dystrophy with supernormal rod electroretinogram and MFRP related oculopathy in a Turkish family. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(2):169–173. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Rochels R, Neuhann T. B scan sonography in drusen of the optic disc. Ophthalmologica. 1979;179(6):330–335. doi: 10.1159/000308940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Roh S, Noecker RJ, Schuman JS. Evaluation of coexisting optic nerve head drusen and glaucoma with optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(7):1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Roh S, Noecker RJ, Schuman JS, et al. Effect of optic nerve head drusen on nerve fiber layer thickness. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(5):878–885. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)95031-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Rosenberg MA, Savino PJ, Glaser JS. A clinical analysis of pseudopapilledema. I. Population, laterality, acuity, refractive error, ophthalmoscopic characteristics, and coincident disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(1):65–70. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010005001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Rossiter JD, Lockwood AJ, Evans AR. Coexistence of optic disc drusen and idiopathic intracranial hypertension in a child. Eye. 2005;19(2):234–235. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Rubinstein K, Ali M. Retinal complications of optic disc drusen. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66(2):83–95. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Sacks JG, O’Grady RB, Choromokos E, Leestma J. The pathogenesis of optic nerve drusen. A hypothesis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95(3):425–428. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450030067005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Saffra NA, Reinherz BJ. Peripapillary Choroidal Neovascularization Associated with Optic Nerve Head Drusen Treated with Anti-VEGF Agents. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2015;6(1):51–55. doi: 10.1159/000375480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Samples JR, van Buskirk M, Shults WT, Van Dyk HJ. Optic nerve head drusen and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(11):1678–1680. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050110072028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Sanders MD, Ffytche TJ. Fluorescein angiography in the diagnosis of drusen of the disc. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1967;87:457–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Sanders TE, Gay AJ, Newman M. Drusen of the optic disk-hemorrhagic complications. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1970;68:186–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Sanders TE, Gay AJ, Newman M. Hemorrhagic complications of drusen of the optic disk. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71(1 Pt 2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(71)90391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Santavuori P, Erkkila H. Neurological and developmental findings in children with optic disc drusen. Neuropadiatrie. 1976;7(3):283–301. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Sarac O, Tasci YY, Gurdal C, Can I. Differentiation of optic disc edema from optic nerve head drusen with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J Neuroophthalmol. 2012;32(3):207–211. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318252561b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Sarkies NJ, Sanders MD. Optic disc drusen and episodic visual loss. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71(7):537–539. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.7.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Sato T, Mrejen S, Spaide RF. Multimodal imaging of optic disc drusen. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(2):275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Saudax E, Martin-Beuzart S, Lesure P, George JL. Submacular neovascular membrane and drusen of the optic disk. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1990;13(4):219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Savino PJ, Glaser JS, Rosenberg MA. A clinical analysis of pseudopapilledema. II. Visual field defects. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97(1):71–75. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1979.01020010011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Scholl GB, Song HS, Winkler DE, Wray SH. The pattern visual evoked potential and pattern electroretinogram in drusen-associated optic neuropathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(1):75–81. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080130077029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Schon JK, Nasemann JE, Boergen KP. Comparative study of deep lying drusen of the papilla with the scanning laser ophthalmoscope and fundus camera. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1992;200(3):175–177. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1045733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Sebag J, Albert DM, Craft JL. The Alstrom syndrome: ophthalmic histopathology and retinal ultrastructure. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(7):494–501. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.7.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Shams PN, Davies NP. Pseudopapilloedema and optic disc haemorrhages in a child misdiagnosed as optic disc swelling. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(10):1398–1399. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.148700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Shelton J, Digre K, Warner J, Katz B. Progression of Visual Field Defects in Patients with Optic Nerve Drusen: Follow-up with Automated Perimetry. North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society (NANOS) Annual Meeting; 2011; Vancouver, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 191.Shields JA, Federman JL, Tomer TL, Annesley WH., Jr Angioid streaks. I. Ophthalmoscopic variations and diagnostic problems. Br J Ophthalmol. 1975;59(5):257–266. doi: 10.1136/bjo.59.5.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Shiono T, Noro M, Tamai M. Presumed drusen of optic nerve head in siblings with Usher syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1991;35(3):300–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Silva R, Torrent T, Loureiro R, et al. Bilateral CNV associated with optic nerve drusen treated with photodynamic therapy with verteporfin. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14(5):434–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.Silverman AL, Tatham AJ, Medeiros FA, Weinreb RN. Assessment of optic nerve head drusen using enhanced depth imaging and swept source optical coherence tomography. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34(2):198–205. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.Slotnick S, Sherman J. Buried disc drusen have hypo-reflective appearance on SD-OCT. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89(5):E704–708. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31824ee8e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.Spencer TS, Katz BJ, Weber SW, Digre KB. Progression from anomalous optic discs to visible optic disc drusen. J Neuroophthalmol. 2004;24(4):297–298. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Spencer WH. Drusen of the optic disk and aberrant axoplasmic transport. The XXXIV Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76658-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Stefan C, Berbece C, Jurja S. Papillary drusen associated with bird shot retinochoroidopathy and the Cacchi-Ricci syndrome. Oftalmologia. 1995;39(2):114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Sturm V, Leiba H, Menke MN, et al. Ophthalmological findings in Joubert syndrome. Eye. 2010;24(2):222–225. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]