Abstract

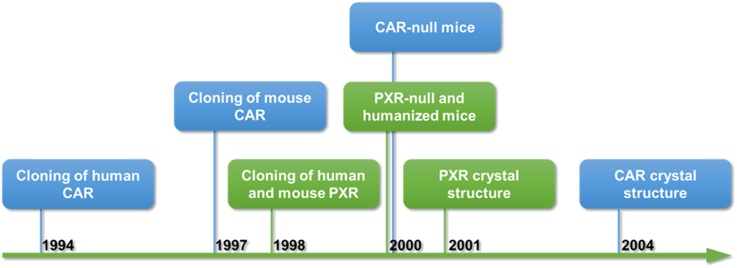

The nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) were cloned and/or established as xenobiotic receptors in 1998. Due to their activities in the transcriptional regulation of phase I and phase II enzymes as well as drug transporters, PXR and CAR have been defined as the master regulators of xenobiotic responses. The discovery of PXR and CAR provides the essential molecular basis by which drugs and other xenobiotic compounds regulate the expression of xenobiotic enzymes and transporters. This article is intended to provide a historical overview on the discovery of PXR and CAR as xenobiotic receptors.

KEY WORDS: Pregnane X receptor, Constitutive androstane receptor, Xenobiotic receptors, CYP3A, CYP2B, CYP2B10

Graphical abstract

The discovery of the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) provides the essentail molecular basis by which drugs and other xenobiotic compounds regulate the expression of xenobiotic enzymes and transporters. This article is intended to provide a historical overview on the discovery of PXR and CAR as xenobiotic receptors.

1. Discovery of PXR as a xenobiotic receptor

The drug responsive regulation of the expression and activity of enzymes or transporters has long been appreciated. This regulation can affect the degree of absorption or elimination of drugs, and potentially alter the therapeutic or toxicological response to a drug. The molecular mechanisms by which drugs regulate enzyme and transporter expression have been elusive up until the discovery and characterization of the xenobiotic nuclear receptor pregnane X receptor (PXR) in 1998, which was independently cloned in the laboratories of Steve Kliewer1 then at the Glaxo Wellcome, and Ron Evans2 at the Salk Institute. The Kliewer laboratory discovered the mouse PXR from a gene fragment in the Washington University mouse expressed-sequence tag (EST) database by Gene Trapper solution hybridization cloning technology using a mouse liver cDNA library1. PXR was named based on its activation by the pregnanes 21-carbon steroids1. The Evans laboratory cloned the human PXR as a homolog of the Xenopus benzoate X receptors (BXR) from a human genomic library/liver cDNA library hybridized with a full-length cDNA encoding the Xenopus BXR, which was originally discovered in a screen for maternally expressed nuclear hormone receptors and cloned from a Xenopus egg cDNA library2, 3. The human PXR was originally named by the Evans laboratory as steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR) due to its activation by multiple natural and synthetic steroids as well as xenobiotics2.

The discovery of PXR benefited from earlier work published by Phil Guzelian׳s laboratory4, 5 at the University of Colorado who suggested that there are “cellular factor” and defined “DNA element” that are responsible for the drug responsive regulation of the human CYP3A and rodent Cyp3a genes in hepatocytes. The consensus glucocorticoid-responsive “DNA element” identified by DNase I footprint turned out to be the PXR response element in the CYP3A gene promoter, which is occupied by the “cellular factor” PXR. Therefore, Cyp3a is considered a prototypical target gene of PXR. The in vivo role of PXR as a xenosensor has been firmly established through the creation and characterization of Pxr knockout mice, in which the Cyp3a induction in response to prototypic inducers, such as pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile (PCN) and dexamethasone (DEX) was completely abolished6, 7. The identification of PXR as a xenosensor also provides a molecular basis for the species specificity of CYP3A induction4. hPXR and mPXR have high homology (95% at the amino acid level) in the DNA-binding domain (DBD), so they can share PXR binding sites found in promoters of the human CYP3A or rodent Cyp3a genes. In contrast, the homology in the ligand-binding domain (LBD) is significantly lower (73% at the amino acid level), which may have explained the ligand specificity between these two receptors. This notion was supported by the X-ray crystal structure analysis of the PXR LBD8. The spherical ligand-binding pocket of PXR was estimated to be at least twice as large as those of the other steroid hormone or retinoid receptors. In addition, the ligand-binding pocket of PXR was extremely hydrophobic and flexible. These structural features may have accounted for the promiscuity of this receptor in recognizing a wide range of xenobiotics8. Using both transfection and transgenic approaches, it has been functionally demonstrated that the species origin of the PXR receptor, rather than the promoter structure of CYP3A genes, dictates the species-specific pattern of CYP3A inducibility6. These findings also led to the creation of the so-called “humanized” hPXR transgenic mice, in which the mouse PXR in the liver was genetically replaced by its human counterpart hPXR. The humanized mice exhibit the human profile of drug response, such as their responsiveness to the human-specific inducer rifampicin and a lack of response to the rodent-specific inducer PCN6. Since the propensity of drugs to induce CYP3A and many other drug metabolizing enzymes are implicated in drug metabolism, drug–drug interactions, and drug toxicity, the humanized mice represent a major step toward creating humanized toxicological models that may aid in the development of safer drugs and nutraceuticals.

2. Characterization of CAR as a xenobiotic receptor

The xenobiotic receptor identity of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), a human orphan nuclear receptor cloned in David Moore׳s laboratory9 in 1994 whose physiological function was then unknown, was revealed shortly after the discovery of PXR in 1998. CAR was initially identified as MB67 from the human cDNA library using a degenerate oligonucleotide directed to the P-box sequence of the thyroid hormone receptor (TR)/retinoid acid receptor (RAR)/orphan receptor subgroup. The receptor was shown to activate a direct repeat spaced by five-nucleotides (DR-5) type of retinoid acid response element (RARE) in a ligand-independent manner, which can be further augmented by the addition of the heterodimerization partner retinoid X receptor (RXR)9. The mouse Car was cloned using the human CAR (MB67) cDNA probe in 199710. The identity of CAR as a xenobiotic receptor was first hinted by the ability of selective androstane metabolites to inhibit its constitutive activity11. The role of CAR in the positive xenobiotic regulation was suggested when CAR was shown to activate the phenobarbital response element (PBRE) found in the promoters of phenobarbital (PB)-inducible Cyp2b genes that were independent reported by several laboratories12, 13, 14. Masa Negishi׳s laboratory15, 16, 17, 18 at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) was the first to purify CAR from mouse hepatocytes as a protein bound to the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module (PBREM) of the Cyp2b10 gene, the mouse homolog of CYP2B, where it heterodimerizes with RXR. CYP2B is therefore a prototypical target gene of CAR. The in vivo xenobiotic function of CAR was firmly established through the creation and characterization of Car knockout mice. Disruption of the mouse CAR locus by homologous recombination resulted in the loss of PB and 1,4-bis(2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy))benzene (TCPOBOP)-activation of Cyp2b10 gene19.

3. Functions of PXR and CAR beyond being “xenobiotic receptors”

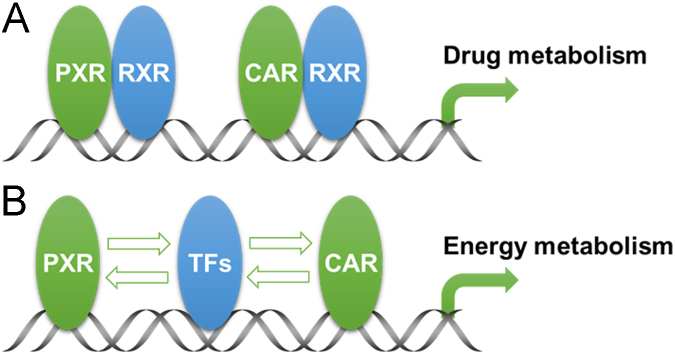

As xenobiotic receptors, PXR and CAR were initially shown to regulate the expression of phase I P450 enzymes, such as the CYP3A and CYP2B enzymes. Subsequent studies from many laboratories have led to the conclusion that PXR and CAR can function as master regulators of the xenobiotic response by regulating the expression of both the phase I and II drug metabolizing enzymes as well as the drug transporters. This regulation has broad implications in drug/xenobiotic metabolism, drug—drug interactions, and drug/xenobiotic toxicity, a topic that has been extensively reviewed20, 21, 22, 23. More recently, it has become clear that PXR- and CAR-mediated regulation of enzymes and transporters can not only impact drug metabolism, but also influence many physiological and disease pathways by affecting the homeostasis of endogenous chemicals, such as bile acids, bilirubin, steroid hormones, glucose, and lipids. These new developments suggest that the functions of PXR and CAR are actually beyond being the “xenobiotic receptors”. Fig. 1 summarizes the functions of PXR and CAR in both drug metabolism and energy metabolism, which is an example of the endobiotic functions of PXR and CAR.

Figure 1.

Summarized functions of PXR and CAR in drug metabolism and energy metabolism. (A) Regulation of drug metabolism by PXR and CAR is achieved by the binding of PXR-RXR or CAR-RXR heterodimers to their binding sites in the promoter regions of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters. (B) PXR and CAR can regulate energy metabolism by directly regulating genes that are involved in energy metabolism, or by crosstaking with other transcriptional factors (TFs) that are implicated in energy metabolism.

Acknowledgments

Numerous investigators and laboratories have participated in the cloning and functional characterization of PXR and CAR, which remain to be a very active area of research 18 years after their discoveries. This review is intended to focus on the initial discovery of PXR and CAR as xenobiotic receptors. It is not our intention to omit many other important literatures related to the functions of PXR and CAR. Wen Xie is supported in part by the Joseph Koslow Endowed Professorship from the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Kliewer S.A., Moore J.T., Wade L., Staudinger J.L., Watson M.A., Jones S.A. An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell. 1998;92:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumberg B., Sabbagh W., Jr, Juguilon H., Bolado J., Jr, van Meter C.M., Ong E.S. SXR, a novel steroid and xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptor. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3195–3205. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumberg B., Kang H., Bolado J., Jr, Chen H.W., Craig A.G., Moreno T.A. BXR, an embryonic orphan nuclear receptor activated by a novel class of endogenous benzoate metabolites. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1269–1277. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barwick J.L., Quattrochi L.C., Mills A.S., Potenza C., Tukey R.H., Guzelian P.S. Trans-species gene transfer for analysis of glucocorticoid-inducible transcriptional activation of transiently expressed human CYP3A4 and rabbit CYP3A6 in primary cultures of adult rat and rabbit hepatocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quattrochi L.C., Mills A.S., Barwick J.L., Yockey C.B., Guzelian P.S. A novel cis-acting element in a liver cytochrome P450 3A gene confers synergistic induction by glucocorticoids plus antiglucocorticoids. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28917–28923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie W., Barwick J.L., Downes M., Blumberg B., Simon C.M., Nelson M.C. Humanized xenobiotic response in mice expressing nuclear receptor SXR. Nature. 2000;406:435–438. doi: 10.1038/35019116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staudinger J.L., Goodwin B., Jones S.A., Hawkins-Brown D., MacKenzie K.I., LaTour A. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3369–3374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051551698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins R.E., Wisely G.B., Moore L.B., Collins J.L., Lambert M.H., Williams S.P. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR: structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science. 2001;292:2329–2333. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baes M., Gulick T., Choi H.S., Martinoli M.G., Simha D., Moore D.D. A new orphan member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that interacts with a subset of retinoic acid response elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1544–1552. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi H.S., Chung M., Tzameli I., Simha D., Lee Y.K., Seol W. Differential transactivation by two isoforms of the orphan nuclear hormone receptor CAR. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23565–23571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forman B.M., Tzameli I., Choi H.-S., Chen J., Simha D., Seol W. Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-β. Nature. 1998;395:612–615. doi: 10.1038/26996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honkakoski P., Negishi M. Characterization of a phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module in mouse P450 Cyp2b10 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14943–14949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trottier E., Belzil A., Stoltz C., Anderson A. Localization of a phenobarbital-responsive element (PBRE) in the 5′-flanking region of the rat CYP2B2 gene. Gene. 1995;158:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00916-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park Y., Li H., Kemper B. Phenobarbital induction mediated by a distal CYP2B2 sequence in rat liver transiently transfected in situ. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23725–23728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honkakoski P., Zelko I., Sueyoshi T., Negishi M. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5652–5658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan L., Vincent J., Brunzelle J.S., Dussault I., Lin M., Ianculescu I. Structure of the murine constitutive androstane receptor complexed to androstenol: a molecular basis for inverse agonism. Mol Cell. 2004;16:907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suino K., Peng L., Reynolds R., Li Y., Cha J.Y., Repa J.J. The nuclear xenobiotic receptor CAR: structural determinants of constitutive activation and heterodimerization. Mol Cell. 2004;16:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu R.X., Lambert M.H., Wisely B.B., Warren E.N., Weinert E.E., Waitt G.M. A structural basis for constitutive activity in the human CAR/RXRα heterodimer. Mol Cell. 2004;16:919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei P., Zhang J., Egan-Hafley M., Liang S.G., Moore D.D. The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature. 2000;407:920–923. doi: 10.1038/35038112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sueyoshi T., Negishi M. Phenobarbital response elements of cytochrome P450 genes and nuclear receptors. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:123–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tzameli I., Moore D.D. Role reversal: new insights from new ligands for the xenobiotic receptor CAR. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie W., Evans R.M. Orphan nuclear receptors: the exotics of xenobiotics. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37739–37742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kliewer S.A., Willson T.M. Regulation of xenobiotic and bile acid metabolism by the nuclear pregnane X receptor. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]