Abstract

Diverse neurological and psychiatric conditions are marked by a diminished sense of positive self-regard, and reductions in self-esteem are associated with risk for these disorders. Recent evidence has shown that the connectivity of frontostriatal circuitry reflects individual differences in self-esteem. However, it remains an open question as to whether the integrity of these connections can predict self-esteem changes over larger timescales. Using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging and probabilistic tractography, we demonstrate that the integrity of white matter pathways linking the medial prefrontal cortex to the ventral striatum predicts changes in self-esteem eight months after initial scanning in sample of thirty young adults. Individuals with greater integrity of this pathway during the scanning session at Time 1 showed increased levels of self-esteem at follow-up, whereas individuals with lower integrity showed stifled or decreased levels of self-esteem. These results provide evidence that frontostriatal white matter integrity predicts the trajectory of self-esteem development in early adulthood, which may contribute to blunted levels of positive self-regard seen in multiple psychiatric conditions including depression and anxiety.

Keywords: Self-esteem, diffusion tensor imaging, medial prefrontal cortex, ventral striatum

Introduction

A diminished sense of self-regard is a hallmark characteristic of multiple psychiatric disorders. Compared to healthy individuals, patients with depression (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989; Butler, Hokanson, & Flynn, 1994), anxiety (Greenberg et al., 1992), and eating disorders (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Vohs et al., 2001) experience blunted levels of self-esteem. Higher self-esteem has also been linked to reduced risk for and greater responsiveness to treatment for these disorders (Roberts, Shapiro, & Gamble, 1999). Moreover, healthy individuals with high self-esteem show increased levels of general happiness, positive affect, and enhanced initiative in the face of challenges (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). Consistent with these findings, psychologists have shown that self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in young adults using longitudinal designs, where higher self-esteem was associated with a reduced risk for depression from adolescence into early adulthood (Orth, Robins, & Roberts, 2008). However, despite decades of research on self-esteem in psychology, the brain systems that support these functions and how they change over time are not well understood.

By definition, self-esteem must incorporate aspects of self-referential cognition with positive affect. The results of meta-analytic neuroimaging studies have shown that self-referential processing is most consistently associated with activation of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) (Denny, Kober, Wager, & Ochsner, 2012; Wagner, Haxby, & Heatherton, 2012), while positive affect can be inferred from activation in the ventral striatum (Knutson, Katovich, & Suri, 2014). Importantly, the integration of information between these two areas may be critical for supporting self-esteem. Recently, we have used multiple neuroimaging modalities to show that connectivity of frontostriatal circuits, linking the MPFC to the ventral striatum, is related to self-esteem (Chavez & Heatherton, 2015). Specifically, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we found that functional connectivity between the MPFC and the ventral striatum during positive self-evaluation was correlated with measures of state self-esteem reflecting transient feelings of positive self-regard. Using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI), we found that white matter integrity in tracts connecting the same frontostriatal regions was correlated with individual differences in trait measures of self-esteem, reflecting general self-esteem maintenance over time. These results suggest that frontostriatal connectivity reflects individual differences in self-esteem operating on multiple timescales.

It remains unknown, however, if these connections maintain self-esteem over time and whether changes in self-esteem can be predicted by the integrity of this network. This may be especially informative during critical phases of personality development such as early adulthood when shifts in levels of self-esteem often occur (Robins, Trzesniewski, Tracy, Gosling, & Potter, 2002). In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that greater structural integrity of frontostriatal white matter tracts connecting the MPFC to the ventral striatum predicts increased longitudinal changes in self-esteem. Using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging, we scanned and measured the self-esteem of in a sample of young adults recently arrived for their first year in college. Approximately eight months after the initial scanning session, we measured their self-esteem again in a follow up session and compared it to their first self-esteem scores at the first time point. Using probabilistic tractography to delineate white matter tracts connecting the MPFC to the ventral striatum, we hypothesized that the integrity of these pathways measured at the beginning of the year would correlate with the change in self-esteem across the two time points.

Materials & Methods

Participants

Subjects participated in the study at two time points: an initial scanning session (Time 1) and a follow-up behavioral session (Time 2). For the Time 1 scanning session, forty-eight Dartmouth College freshmen between the ages of 18 and 19 years (28 female) were recruited from the student community. The Time 1 scanning session was completed within the first two weeks of the academic year. All subjects were screened to be right-handed and reported no history of psychiatric or neurological conditions and were kept blind to the aim of the study. The Time 1 dataset used in the current study is identical to that used in Chavez and Heatherton (2015). Of the 48 subjects who participated in the Time 1 scanning session, 30 subjects (20 female) returned to the lab at Time 2 for the follow-up behavioral session between 31 and 33 weeks (i.e., approximately eight months) after their first visit. There were no differences in self-esteem between those who were included and those who were unable to participate (neither the mean nor variance differed for the groups, p’s > .10). For both Time 1 and Time 2 experiments, subjects gave informed consent in accordance with the guidelines set by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College. All subjects either received course credit or were paid for their participation after each session.

Procedure

During the Time 1 scanning session, subjects underwent MRI scanning and behavioral assessment outside of the scanner. While in the scanner, each subject received a high-resolution anatomical scan and two runs of a diffusion-weighted imaging scan. Each subject’s self-esteem was assessed via surveys completed outside the scanner. Trait self-esteem was measured using the Janis and Field Feelings of Inadequacy Scale (Fleming & Courtney, 1984), which asks participants to report general self-evaluative feelings. During the Time 2 behavioral session, participants came back to the lab to complete surveys, but did not participate in MRI scanning.

Image acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging was conducted with a Philips Achieva 3.0 Tesla scanner using a 32-channel phased array head coil. High-resolution anatomical images were acquired using a T1-weighted MP-RAGE protocol (220 sagittal slices; TR: 8.176 ms; TE: 3.72 ms; flip angle: 8°; 1 mm isotropic voxels). Diffusion-weighted images were collected using 70 contiguous 2 mm thick axial slices with 32 diffusion directions (91 ms TE, 8848 TR, 1000 s/mm2 b-value, 240 mm FOV, 90° flip angle, 1.875 mm × 1.875 mm × 2 mm voxel size). Two diffusion scans were acquired and averaged per subject in order to increase the dMRI signal-to-noise ratio.

Image analyses

All anatomical and dMRI scans were visually inspected for quality to ensure that there were no gross distortions, misalignments, or segmentation errors. Skull-stripping of the anatomical images was performed using the Brain Extraction Tool in FSL (Smith, 2002). Transformation warps of the anatomical images to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space template brain were calculated using non-linear registration with FMRIB's Non-linear Image Registration Tool (FNIRT) in FSL. Bilateral ventral striatum regions of interest (ROIs) were defined anatomically within each subject’s native space using an automated subcortical segmentation tool (Patenaude, Smith, Kennedy, & Jenkinson, 2011).

DMRI data were analyzed using the Diffusion Toolbox in FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FDT) (Behrens et al., 2003). Standard preprocessing included brain extraction, eddy current correction and motion correction. To model the underlying white matter architecture, a dual-fiber model was implemented using the Bayesian Estimation of Diffusion Parameters Obtained using Sampling Techniques method (BEDPOSTx; Behrens, Berg, Jbabdi, Rushworth, & Woolrich, 2007) to account for crossing fiber uncertainty in the diffusion-imaging signal. Probabilistic tractography was used to delineate white matter tracts between each of the bilateral ventral striatum ROIs and an area of the MPFC defined from areas which are consistent with a meta-analysis by Denny et al., (2012) that have shown to be recruited for self-referential processing in the literature. Using two-mask seeding, 5000 probabilistic tract streamlines were taken at each voxel within each mask. This method allowed resulting tractography maps to only include streamlines passing through both the MPFC and ventral striatum seed masks. These results were then normalized to MNI standard space using non-linear registration warps from each subject’s high-resolution anatomical scan in FNIRT. To ensure tracts were consistent among subjects, registered tractography results were binarized within each subject and then added together across subjects to create group-level probabilistic tractography maps. Thresholding of these probabilistic maps was set at 50%, such that at least 24 subjects (the total number of subjects divided by two) had overlapping tracts within any given voxel of the group mask. White matter integrity was measured using partial volume fractions (PVFs) corresponding to the first-order fiber orientation calculated in BEDPOSTx. Importantly, these PVF measures are analogous to fractional anisotropy (the most commonly used metric in in the diffusion imaging literature), but are more conservative and attempt to account for crossing fiber uncertainty by inferring signal from only a single fiber orientation at a time (Jbabdi, Behrens, & Smith, 2010). Individual differences in white matter integrity were then quantified by overlaying group tractography results onto each subject’s PVF image and averaging across white matter voxels. These values were then used for the correlational analyses with self-esteem for each bilateral frontostriatal tract.

Results

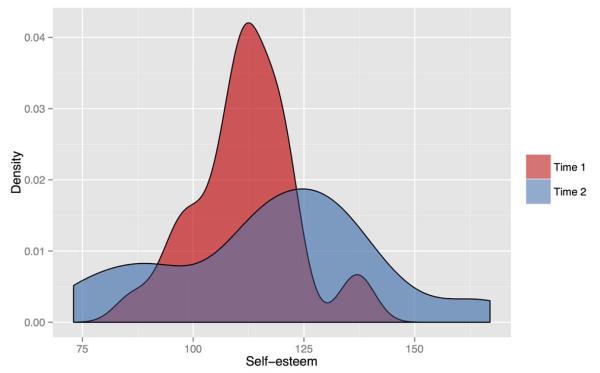

As hypothesized, Time 1 (M = 111.8) and Time 2 (M = 117.2) self-esteem measures were significantly correlated overall (R28 = .73, p < .0001) but showed shifts in their respective distributions between time points. From Time 1 to Time 2, average within-subject self-esteem values increased, but the differences were not statistically significant (T28 = 1.73, p = .09). However, there was a large increase in the variance of self-esteem scores from Time 1 (SD = 11.28) to Time 2 (SD = 23.37), showing self-esteem scores spreading towards both ends of the scale over time (Bartlett’s K2 = 13.95, p < .001). Differences in the distribution of self-esteem scores from Time 1 and Time 2 are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Density curves showing the distribution of self-esteem scores at Time 1 and Time 2. Self-esteem scores spread toward both ends of the distribution over time, indicating that some individuals experienced increased self-esteem, while others experienced decreased self-esteem.

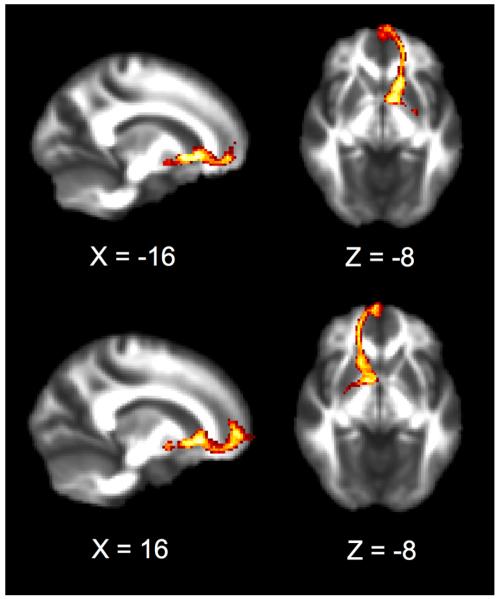

Results from the probabilistic tractography analyses revealed a robust white matter pathway linking the MPFC and bilateral ventral striatum across subjects. Probabilistic tractography maps showing each bilateral frontostriatal white matter pathway are displayed in Figure 2. Consistent with the findings from Chavez and Heatherton (2015), the current sample of 30 subjects’ Time 1 self-esteem was highly correlated with bilateral frontostriatal tract integrity (left hemisphere: R28 = .49, p < .006; right hemisphere: R28 = .54, p < .002). Similarly, frontostriatal integrity was also highly correlated with Time 2 self-esteem scores in both hemispheres (left hemisphere: R28 = .67, p < .0001; right hemisphere: R28 = .60, p < .0004). Interestingly, tract integrity (which was only measured at Time 1) showed a stronger relationship to self-esteem scores at Time 2, relative to Time 1.

Figure 2.

Cross-subject probabilistic tractography results displaying bilateral MPFC to ventral striatum white matter tracts reveal a robust anatomical connection between these regions. Slices are marked with MNI coordinates.

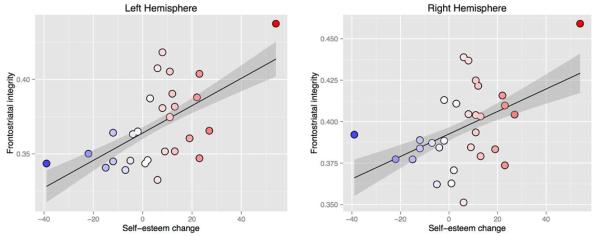

The primary question of interest was whether frontostriatal integrity measures could account for the change in self-esteem from Time 1 and Time 2. To test this, Time 1 self-esteem was subtracted from Time 2 self-esteem to create a self-esteem change index. Self-esteem change was significantly correlated with frontostriatal integrity in both the left hemisphere (R(28) = .59, p = .0005) and the right hemisphere: (R(28) = .47, p = .009). Scatterplots of these relationships are displayed in Figure 3. Although these effects are strong, it is worth noting that there are two possible outliers on either end of the self-esteem change index. To ensure that our results are robust to these individuals, both of these data points were eliminated and the analysis was repeated. After removing the potential outliers, the left hemisphere tract remains significant (R(26) = .42, p = .025) while the right hemisphere tract shows a near-significant trend falling slightly below α = .05 (R(26) = .33, p = .08). However, whole sample correlation coefficients computed using Fisher R-to-z transformation comparisons were not significantly different in the outlier-removed sample in either hemisphere (left: z = 0.83, p = .41; right: z = 0.4, p = .68). In addition to removing the influence of the outliers, this analysis also indicates that even with a reduction in statistical power, left- hemisphere frontostriatal integrity remains significant, while the right hemisphere shows a positive trend. These relationships indicate that individuals with greater tract integrity at Time 1 were more likely to show increases in self-esteem at Time 2. Conversely, individuals with lower tract integrity at Time 1 were more likely to show decreases or little change in self-esteem at Time 2.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots depicting the relationship of frontostriatal white matter integrity and the difference between self-esteem from Time 1 to Time 2. Bilateral frontostriatal integrity predicted the change in self-esteem from Time 1 to Time 2. Warm colors indicate individuals whose self-esteem increased from Time 1 to Time 2; cool colors indicate individuals whose self-esteem decreased.

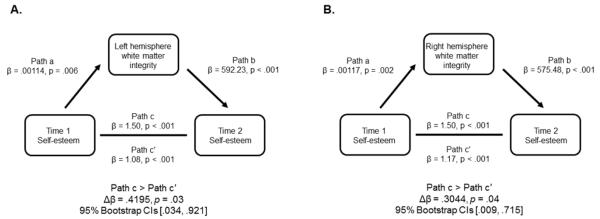

Finally, the question remains whether frontostriatal white matter integrity mediates the relationship between self-esteem scores taken at the two time points. To test this, we conducted a mediation analysis for each hemisphere separately. Bias-corrected bootstrap sampling (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013) was used to assess the significance. From this analysis, we found that frontostriatal integrity showed a significant partial mediation for the relationship between Time 1 and Time 2 in both hemispheres. The full results of the mediation analyses are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The results of the mediation analyses indicating that white matter integrity has a significant partial mediation of the relationship between self-esteem scores at Time 1 and Time 2. (A) Consistent with the correlational analyses, results from the left hemisphere showed the strongest mediation effects between the two hemispheres. (B) Results of the mediation analysis in right hemisphere were significant but weaker than in the left.

Discussion

The results of the current study show that the structural integrity of frontostriatal white matter tracts predict changes in self-esteem over the course of several months in young adults. Specifically, these results reflect a “rich get richer” scenario: individuals with greater tract integrity had higher self-esteem at Time 1 and were more likely to have higher self-esteem at the follow-up, whereas individuals with lower tract integrity were more likely to have lower self-esteem at the follow-up. The results of our analyses also show that the relationship between self-esteem at Time 1 and Time 2 is partially mediated by frontostriatal tract integrity in both hemispheres. Thus, the structural connectivity of the MPFC and ventral striatum may reflect long-term self-esteem by predicting the polarization of its trajectory over time.

Previous research has shown that self-esteem varies across the lifespan, both in degree and stability. In a large cross-sectional study, researchers found that self-esteem levels begin to shift markedly in direction during early adulthood (Robins et al., 2002). Additionally, using longitudinal methods, researchers have found that self-esteem levels tend to increase throughout adulthood (Erol & Orth, 2011), before beginning to decline later in life (Orth, Trzesniewski, & Robins, 2010). However, the stability of self-esteem in early adulthood is slightly lower than in midlife stages, but is higher than it is in either adolescence or late life (Trzesniewski, Donnellan, & Robins, 2003). Together, these findings suggest that self-esteem development in early adulthood strikes a balance between plasticity and reliability, whereby self-esteem changes commonly occur but can also be measured with increased reliability. The cohort of college freshman used in the current study reflects the patterns in the extant literature. Self-esteem scores from Time 1 and Time 2 were significantly correlated, reflecting the reliability of scores overall. However, the difference in the variance between the two time points shows the plasticity of self-esteem within subjects. This plasticity may reflect the susceptibility of self-esteem to changing life circumstances, allowing for shifts in these scores over participants’ first year of college. The results of the current study indicate that variations in self-esteem scores over time are mediated by individual differences in frontostriatal white matter integrity at a given baseline.

These results also add to work linking self-referential processing to reward systems in the brain. For instance, disclosing information about the self has been shown to activate the ventral striatum and ventral tegmental area (Tamir & Mitchell, 2012), and meta-analyses have revealed that the ventral striatum shows consistently greater activation to the representation of self vs. others (Denny et al., 2012) and to the representation of personal vs. vicarious rewards (Morelli, Sacchet, & Zaki, 2014). Recently, researchers have also linked the identical frontostriatal white matter tracts to individual differences in narcissism, underscoring its role in evaluative self-referential processing related to psychopathology (Chester, Lynam, Powell, & DeWall, in press) Moreover, the current study’s results build upon previous work linking individual differences in self-esteem to frontostriatal networks involved in positive affect and reward (Chavez & Heatherton, 2015). Specifically, the integrity of frontostriatal anatomical pathways was not only related to individual differences in trait self-esteem, but was also correlated with the variability of that trait over time. Taken together, these findings suggest that certain facets of self-representation may be inherently linked to positive evaluation and reward systems that are reflected in the underlying neuroanatomy.

There are some limitations of the current study to mention. First, subjects were only scanned at Time 1, so it cannot be determined if the changes in self-esteem were accompanied by changes in white matter integrity within these pathways as well. However, the current results can be seen as analogous to the use of a radiological scan to inform the prognosis of a medical condition: To the extent that one is interested in predicting changes in self-evaluation, these results provide evidence that a snapshot of brain connectivity at one time point can account for some of the variance in shifting self-evaluative attitudes over time. Second, this study sought to investigate self-esteem in a sample of individuals within a marked period of personality development, namely first-year college students. Although the current results speak to the nature of these effects for similar individuals within this timeframe, they might not reflect similar processes across the entire lifespan or in people of different socioeconomic statuses. Nonetheless, ages of the subjects in the current study is within range of previous longitudinal studies linking self-esteem to future onset of depression (Orth et al., 2008). Similarly, though we would hypothesize that our findings would generalize to populations of patients diagnosed with an affective disorder, our data cannot speak to this possibility directly. Future studies recruiting patient populations will be necessary to test these possibilities. Finally, though the sample of participants used in the current study were healthy students who did not report any history of mental illness, we did not screen for these issues using structured interviews. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that our cohort of participant were free of more subtle mental health issues.

In conclusion, the current study provides evidence that changes in self-esteem during early adulthood are mediated by individual differences in frontostriatal white matter integrity prospectively, pointing to a possible biological mechanism underlying the trajectory of self-esteem changes. Given that previous longitudinal studies have identified self-esteem as a risk factor for depressive symptoms (Orth, Robins, & Meier, 2009; Orth, Robins, Trzesniewski, Maes, & Schmitt, 2009), our results contribute to a growing body of work linking self-esteem to mental health, and may inform the etiology and prognosis of depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Courtney Rogers for help with data collection. R.S.C. is a National Science Foundation graduate research fellow. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH059282) to T.F.H.

References

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:368. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. http://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TEJ, Berg HJ, Jbabdi S, Rushworth MFS, Woolrich MW. Probabilistic diffusion tractography with multiple fibre orientations: What can we gain? NeuroImage. 2007;34(1):144–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.018. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, Smith SM. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;50(5):1077–88. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10609. http://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Hokanson JE, Flynn HA. A comparison of self-esteem lability and low trait self-esteem as vulnerability factors for depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psycholog. 1994;6(1):166. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.166. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez RS, Heatherton TF. Multimodal frontostriatal connectivity underlies individual differences in self-esteem. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2015;10(3):364–70. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu063. http://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DS, Lynam DR, Powell DK, DeWall CN. Narcissism is associated with weakened frontostriatal connectivity: a DTI study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsv069. (in press) http://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny BT, Kober H, Wager TD, Ochsner KN. A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of self- and other judgments reveals a spatial gradient for mentalizing in medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;24(8):1742–52. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00233. http://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol RY, Orth U. Self-esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101(3):607–19. doi: 10.1037/a0024299. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JS, Courtney BE. The dimensionality of self-esteem: II. Hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46(2):404–421. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.404. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J, Solomon S, Pyszczynski T, Rosenblatt A, Burling J, Lyon D, Pinel E. Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(6):913–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.913. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Scharkow M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: does method really matter? Psychological Science. 2013;24(10):1918–27. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613480187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(1):86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jbabdi S, Behrens TEJ, Smith SM. Crossing fibres in tract-based spatial statistics. NeuroImage. 2010;49(1):249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.039. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Katovich K, Suri G. Inferring affect from fMRI data. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014;18(8):422–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli SA, Sacchet MD, Zaki J. Common and distinct neural correlates of personal and vicarious reward: A quantitative meta-analysis. NeuroImage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.056. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Meier LL. Disentangling the effects of low self-esteem and stressful events on depression: findings from three longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(2):307–321. doi: 10.1037/a0015645. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0015645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(3):695–708. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Maes J, Schmitt M. Low self-esteem is a risk factor for depressive symptoms from young adulthood to old age. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):472–478. doi: 10.1037/a0015922. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0015922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth U, Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW. Self-esteem development from young adulthood to old age: a cohort-sequential longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(4):645–658. doi: 10.1037/a0018769. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0018769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, Jenkinson M. A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. NeuroImage. 2011;56(3):907–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Shapiro AM, Gamble SA. Level and perceived stability of self-esteem prospectively predict depressive symptoms during psychoeducational group treatment. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38(Pt 4):425–9. doi: 10.1348/014466599162917. http://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Tracy JL, Gosling SD, Potter J. Global self-esteem across the life span. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17(3):423–34. http://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.3.423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human Brain Mapping. 2002;17(3):143–55. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. http://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir DI, Mitchell JJP. Disclosing information about the self is intrinsically rewarding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;2012(21):8038–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202129109. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202129109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Robins RW. Stability of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84(1):205–220. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Voelz ZR, Pettit JW, Bardone AM, Katz J, Abramson LY, Joiner TE. Perfectionism, Body Dissatisfaction, And Self-esteem: An Interactive Model of Bulimic Symptom Development. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20(4):476–497. http://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.20.4.476.22397. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD, Haxby JV, Heatherton TF. The Representation of Self and Person Knowledge in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science. 2012;3(4):451–470. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1183. http://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]