Abstract

It is now evident that the cell nucleus undergoes dramatic shape changes during important cellular processes such as cell transmigration through extracellular matrix and endothelium. Recent experimental data suggest that during cell transmigration the deformability of the nucleus could be a limiting factor, and the morphological and structural alterations that the nucleus encounters can perturb genomic organization that in turn influences cellular behavior. Despite its importance, a biophysical model that connects the experimentally observed nuclear morphological changes to the underlying biophysical factors during transmigration through small constrictions is still lacking. Here, we developed a universal chemomechanical model that describes nuclear strains and shapes and predicts thresholds for the rupture of the nuclear envelope and for nuclear plastic deformation during transmigration through small constrictions. The model includes actin contraction and cytosolic back pressure that squeeze the nucleus through constrictions and overcome the mechanical resistance from deformation of the nucleus and the constrictions. The nucleus is treated as an elastic shell encompassing a poroelastic material representing the nuclear envelope and inner nucleoplasm, respectively. Tuning the chemomechanical parameters of different components such as cell contractility and nuclear and matrix stiffnesses, our model predicts the lower bounds of constriction size for successful transmigration. Furthermore, treating the chromatin as a plastic material, our model faithfully reproduced the experimentally observed irreversible nuclear deformations after transmigration in lamin-A/C-deficient cells, whereas the wild-type cells show much less plastic deformation. Along with making testable predictions, which are in accord with our experiments and existing literature, our work provides a realistic framework to assess the biophysical modulators of nuclear deformation during cell transmigration.

Introduction

Tumor cell extravasation is one of the critical, and possibly rate-limiting, steps in the process by which cancer spreads to metastatic sites from a primary tumor (1, 2). Although we know relatively little about the details of extravasation, recent in vitro studies have elucidated a process beginning with tumor cell arrest in the microcirculation and the formation of protrusions that reach across the endothelial monolayer, accompanied by polarization of tumor cell actin and activation of β-1 integrins to generate firm adhesions (3, 4). This is rapidly followed by actomyosin contraction to generate the forces needed to pull the remaining cell body across the monolayer. Similarly, during invasion into tissues, tumor cells use actomyosin activity to squeeze through tight interstitial spaces (5). During these processes, the cell size, rheological properties and the geometric parameters associated with the extracellular environment dictate the maximal rate at which the cell can transmigrate and change its shape (6, 7). The nucleus, being the largest and the stiffest organelle within the cell, is a physical constraint to migration and may be a rate-limiting factor for cellular deformations during cell migration through three-dimensional (3D) constrictions that are smaller or comparable to the nuclear cross section (8, 9, 10). On the other hand, since the nucleus houses the genetic machinery of the cell, changes in the nuclear morphology and positioning within the cytoplasm during migration can influence the phenotypic profile of the cell (5, 11). For instance, it has been recently shown that in addition to the ability of cells to dramatically squeeze their nuclei to pass through small constrictions, cells utilize components of the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery to repair the concomitant damage to their nuclear envelope (NE) and DNA that occur during confined migration (12, 13).

In light of experimental discoveries that identified nuclear morphological changes and their implications for cellular behavior, progress has been made in quantifying mechanical and rheological properties of the nucleus (14, 15). Yet how actomyosin-generated forces coordinate with geometric and mechanical parameters (such as the constriction size and the stiffness of the extracellular matrix and the nucleus) to modulate the nuclear morphology during cell passage through small openings remains poorly understood. Furthermore, despite the development of a variety of approaches that model the mechanics of the whole cell (16, 17, 18), a mechanistic model to assess the ability of cells to pass through small constrictions and the role of the nucleus and other biophysical parameters is still lacking.

To address these shortcomings, we developed a novel, to our knowledge, chemomechanical model that describes nuclear morphology during cell migration through deformable constrictions smaller than the size of the nucleus. Based on biophysical modulators of transmigration including actomyosin contractility, the geometric and mechanical properties of the opening, the nucleus, and the extracellular matrix (ECM), our model estimates the stiffness-dependent actomyosin driving forces and the mechanical resistance encountered by the nucleus to predict the chances of successful transmigration. By varying these biophysical factors, we computed the strain distribution within the nucleus at different stages of transmigration to elucidate the physical mechanisms behind NE and DNA damage, as well as the thresholds for plastic deformation of the nucleus. To verify our model, we simulated nuclear transmigration through an endothelial gap and also passage through rigid constrictions. Tuning our model parameters by comparison with experimental measurements, our framework provides a quantitative description of nuclear mechanics during transmigration of cancer cells across the endothelial monolayer and through rigid constrictions.

Materials and Methods

Model formulation

To understand the influence of both the intracellular and extracellular cues and the mechanical properties of the nucleus on cell transmigration, a cell with a spherical nucleus of radius invading the ECM through a deformable gap smaller than the diameter of the nucleus (Fig. 1 c) is considered. The nucleus is treated as a nonlinear shell with shear modulus , simulating the NE, filled with a soft poroelastic solid material mimicking chromatin and other subnuclear structures (Fig. 1 c; refer to the Supporting Material for details). Recent work has shown that the nucleus is also viscoelastic, but the timescale of viscous relaxation is of the order of 1–300 s (14, 15, 19, 20), which is an order of magnitude smaller than the time it takes the nucleus to pass through endothelial gaps/constrictions (3). Thus, the elastic properties we use here are the moduli after the viscous effects have relaxed. To model the extracellular environment, a thin flexible layer with a hole or gap of radius mimicking the endothelium (or a constriction in a microfluidic device) and a deformable ECM placed on the other side of the endothelium are introduced (Fig. 1 c). The endothelium (or constriction) and the ECM are treated as compressible neo-Hookean hyperelastic materials to capture the mechanical response (refer to the Supporting Material for details).

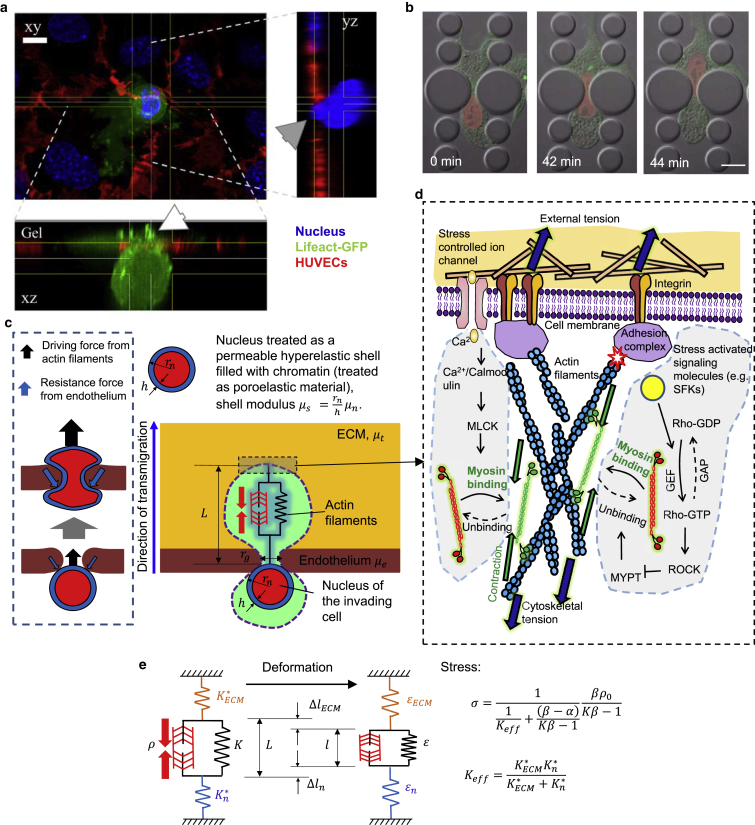

Figure 1.

Computational model for tumor cell transmigration. (a) High-resolution confocal z-stack of a cancer cell (Lifeact-GFP, MDA-MB-231, green) transmigrating through an endothelial monolayer (PECAM-1, HUVECs, red) cultured on a collagen gel. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). The white arrow indicates actin-rich protrusions at the leading edge of the cancer cell entering the ECM. The gray arrow indicates the front of the cancer cell nucleus squeezing through the endothelial gap. Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Representative time-lapse images of a fibroblast (NIH 3T3) expressing mCherry-Histone4 (red) and GFP-actin (green) migrating through a 3-μm-wide rigid constriction in a 5-μm-tall microfluidic device. Scale bar, 15 μm. (c) The nucleus is modeled as a permeable hyperelastic shell (representing the NE) with modulus filled with chromatin (modeled as a poroelastic material with modulus and Poisson’s ratio in the range ∼0.3–0.5 based on permeability). The parameters in the model are the shear moduli for the endothelium , the ECM , and the nucleus , the nuclear radius , the endothelial gap size , and the average length of the actin filaments . The nuclear stiffness, , is mainly determined by the NE elasticity, , , where is the thickness of the shell. (d) The driving force for transmigration is generated by stress-dependent contraction of the actomyosin complex. The actomyosin activity is mediated by a variety of biochemical processes, such as the ρ-ROCK and calcium-mediated pathways (see the Supporting Material for details). (e) Schematic for the mechanical model of active contractile stress generation. The actomyosin contraction is modeled by a spring in parallel with an active contractile element, which ensures that stiffer ECMs will generate larger contractile stresses (see the Supporting Material for details). To see this figure in color, go online.

The actomyosin contraction at the front of the cell provides the driving force for transmigration. A cell can adjust its contractility by controlling myosin motor recruitment through a variety of signaling pathways, such as Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) and Ca (Fig. 1 d; refer to the Supporting Material for details). Here, we applied our recently published model (21) to introduce the stiffness-dependent recruitment of the contractile machinery (Fig. 1 e; refer to the Supporting Material for detailed descriptions) that accounts for the influence of both intracellular (for example, signal pathways) and extracellular cues (ECM modulus and deformation). The resistance force during transmigration is calculated using the finite-element method to compute the deformations of the nucleus, endothelium, and ECM. Transmigration is predicted to be successful if the resistance force is smaller than the actomyosin contractile force. The simulation steps are shown in Fig. S1.

Atomic force microscopy

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) microindentation measurements of gel and cell nucleus elasticity were performed using a JPK NanoWizard I (JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany) interfaced to an inverted optical microscope (IX81, Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Cantilevers (MLCT, Bruker, Billerica, MA; nominal spring constants of 0.07 N m−1) were modified by attaching beads (15 μm beads for cellular measurements and 50 μm for gel) using ultraviolet curing glue. Using the thermal noise method implemented in the AFM software (JPK SPM), the spring constants of the cantilevers were determined. Before measurements, the sensitivity of the cantilever was set by measuring the slope of the force-distance curves acquired on a glass-bottom petri dish. To determine the nucleus elasticity, we applied force to the nuclear regions of the cell with large forces (>9 nN) to create indentation depths >2 μm that ensure significant deformation of the nucleus and thereby maximize the contribution of the nucleus to the measured elasticity (22). The tip of the cantilever was aligned over the regions above the cell nucleus using the optical microscope and indentation measurements were performed. Force-distance curves were acquired with an approach speed of 1 μm s−1 until reaching the maximum set force of 20 nN. Using a previously described method (23), we found the contact point and subsequently calculated the indentation depth, δ, by subtracting the cantilever deflection, d, from the piezo translation, z, after contact . The elastic moduli were extracted from the force-distance curves by fitting the contact portion of curves to a Hertz contact model between a spherical indenter and an infinite half-space (24).

Microfluidic device and NE rupture experiments

Details on the microfluidic device fabrication, cells used, and analysis of the chromatin deformation have been described previously (25). In brief, cells were plated in a microfluidic device made of polydimethylsiloxane and a glass slide, containing 5-μm-tall migration channels with constrictions of 1–15 μm in width. Cells migrate along a chemotactic gradient, and nuclear deformation is observed by time-lapse imaging of fluorescently labeled histones. As decribed previously, NE rupture was detected by monitoring the transient escape of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused with a nuclear localization signal (NLS-GFP) from the nucleus into the cytoplasm and fluorescently labeled cytoplasmic DNA-binding protein (cGAS-RFP) that accumulates at newly exposed genomic DNA was used to monitor the sites of NE rupture (13). Cells were generated by stable expression of fluorescent reporter proteins, i.e., NLS-GFP and cGAS-RFP, by lentiviral transduction. For confined migration experiments, cells were loaded into a custom-manufactured microfluidic device and imaged for 14 h on a temperature-controlled microscope. Image analysis was carried out in ZEN (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA), and ImageJ.

Results

During extravasation, the invading cancer cell sends protrusions between two adjacent endothelial cells, and creates a small opening within the endothelial layer (4). The actin-rich protrusions at the front of the cell (Fig. 1 a, green region) adhere to and pass through the basement membrane, penetrating into the ECM. During transendothelial migration (TEM), the actomyosin-mediated contractile forces generated in the “preinvaded” part of the cell and around the nucleus, push/pull the nucleus to pass through the endothelial gap. Similarly, as cells migrate through interstitial spaces, they have to move through confined spaces imposed by extracellular matrix fibers and surrounding cells (9). To understand the influence of both the intracellular and extracellular cues and the mechanical properties of the nucleus on cell transmigration, we consider the case of a cell with an initially spherical nucleus of radius invading the ECM through the endothelial layer or, more generally, a gap (of radius ) smaller than the radius of the nucleus (Fig. 1, b and c). We adopted our recently developed chemomechanical model (21) to describe the stress-dependent actomyosin activity (Fig. 1 e), which is mediated by mechanosensitive signaling pathways such as the Src-family kinases, ROCK, and myosin light chain kinase, as shown in Fig. 1 d. We first studied the mechanics of nuclear transmigration through deformable constrictions to mimic TEM and then explored cell passage through rigid constrictions, for example, in microfluidic devices whose dimensions can be specified (25).

ECM stiffness and gap size modulate nuclear transmigration

We employed finite-element simulations to estimate the normalized resistance force during each stage of nuclear transmigration (see the Supporting Material for details). As the nucleus enters the constriction, increases monotonically as the nucleus advances, reaching a maximal resistance force (which we name the critical resistance force, ) at a critical position. After this, the nucleus snaps through the opening, leading to a drop in the resistance force, which vanishes after complete nuclear escape (Fig. S2 a). To predict the driving force, we calculated the normalized actomyosin contractile forces based on an actin contraction model (21) that relies on a mechanochemical feedback parameter , that accounts for the increase in contractility in response to tension in the actomyosin system (see the Supporting Material for details). Through myosin motor recruitment, the contractile force gradually reaches its maximum level to overcome the resistance force leading to successful transmigration, . is defined as the critical mechanochemical coupling parameter that is just sufficient for transmigration to occur ( at the critical position). At weak feedback levels , the cell is unable to build up enough driving force for the nucleus to pass through (Fig. S2 b, top), whereas at higher feedback levels , the cell is able to generate the critical force required to snap through the gap (Fig. S2 b, bottom).

Our model shows that the radii of the nucleus and the endothelial gap , and the moduli of the endothelium and the nucleus are the main determinants of the resistance force, . Indeed, transmigration is difficult through small endothelial gaps (Fig. 2 a) and a stiffer endothelium also impedes transmigration. Although the modulus of the ECM has little influence on the resistance force, it has a strong effect on the actomyosin contractile forces: at the same chemomechanical coupling level, a softer ECM induces lower levels of cellular contractile force (21, 26, 27), which may not be sufficient for the cells to overcome the resistance force. Therefore, it is less likely for the cell to transmigrate when the ECM is soft (Fig. 2 b). On the other hand, a stiffer ECM often has smaller pores, which impose higher geometrical constraints on cell movement. Therefore, although a cell encountering a stiff ECM can develop higher contractile forces, the chances of successful transmigration are still limited by the geometric constraints. For the sake of simplicity, the strain-stiffening response of the fibrous ECMs was not taken into consideration in this analysis. With strain-stiffening, we would expect that the cell can transmigrate through smaller gaps (compared to current predictions), particularly for soft ECMs. Since the strain-stiffening nature of fibrous ECM (28, 29) is more pronounced in soft ECMs, the cell will potentially generate a higher level of contractile force and therefore facilitate transmigration.

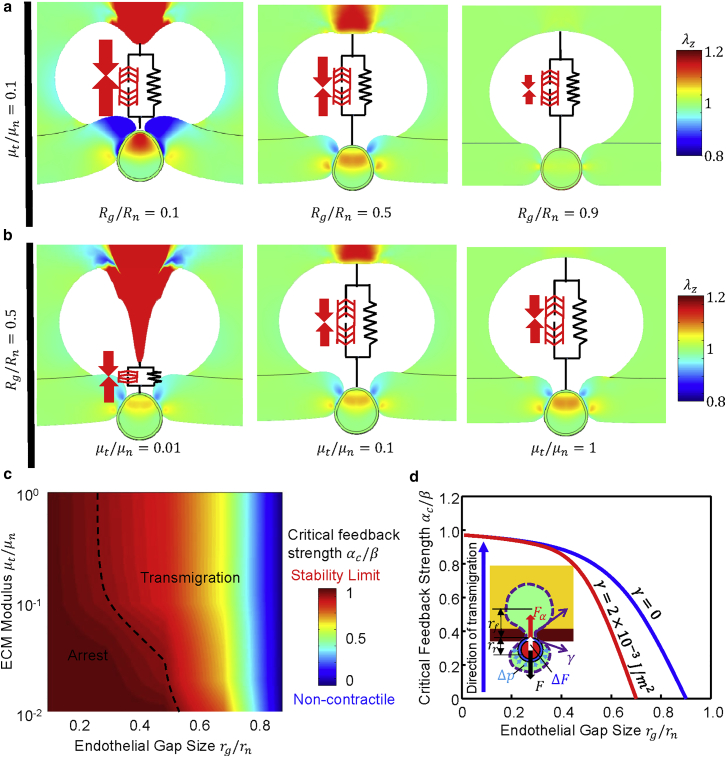

Figure 2.

Influence of the endothelial gap size and ECM modulus on transmigration. (a) As the gap size decreases (from right to left) the cell cannot transmigrate through the smaller gaps because of the increase in critical resistance force. (b) As the ECM stiffness decreases (from right to left) cells cannot transmigrate since they cannot build up sufficient contractile forces in soft ECMs. Colors in (a) and (b) indicate the stretches along the direction of invasion. (c) Critical feedback strength as a function of the ECM modulus and the endothelial gap size predicted by the model. The dashed line denotes the phase boundary for transmigration. On the righthand side of the phase boundary, and the cells can pass through the gap. The model predicts the physical limit of for successful transmigration, corresponding to ∼10% of the undeformed nuclear cross section, in excellent agreement with previous measurements (9), as shown in Fig. S3. (d) Cytosolic pressure generated through cortical actomyosin contractility can promote transmigration. Comparison between the critical feedback strength required for transmigration as a function of the endothelial gap size with (red) and without (blue) accounting for pressure exerted on the nucleus due to membrane tension. Model parameters are kPa, kPa, Pa, kPa, kPa, kPa in (a), and in (b). To see this figure in color, go online.

By varying the model parameters, we have predicted the normalized critical feedback strength (, where β is a chemomechanical coupling parameter related to motor engagement; see the Supporting Material for details) as a function of the radius of the endothelial constriction and the ECM modulus (Fig. 2 c). The model predicts the physical limit for successful transmigration to be , corresponding to ∼10% of the undeformed nuclear cross-sectional area, in excellent agreement with previous measurements (9), as shown in Fig. S3. Our AFM measurements of the elastic properties of components of an extravasation monolayer assay show Pa, Pa, and Pa (Fig. S4). This, together with the geometrical parameters extracted from our system (Fig. S4), implies that cancer cells have to overcome a resistance force of ∼38 nN to successfully transmigrate through endothelial constrictions as small as 30% of the nucleus size, which is within the physiological range (30).

Lamin A/C level is one of the main determinants of the resistance forces

It has been shown that the levels of the NE proteins lamin A and C (lamin A/C) determine the stiffness of the nucleus (20, 31, 32, 33), and that lower levels of lamin A/C facilitate cell migration through tight spaces (8, 10, 34). We studied the influence of lamin A/C on transmigration by varying the modulus of the NE in our model (Fig. S5). The critical resistance force linearly increases with increasing nuclear stiffness. Contractile driving force also increases with increase in the nuclear and ECM stiffness, but eventually reaches a plateau (Fig. S5). Therefore, transmigration cannot occur due to the lack of sufficiently large contractile forces if cells have very stiff nuclei (wild-type cells) (30). For soft nuclei (e.g., lamin-A/C-deficient cells), the resistance force is much smaller than the contractile force, implying that transmigration is much easier for these cells but is accompanied by large nuclear deformations, consistent with recent measurements in microfluidic devices (25).

Contribution of cytosolic back pressure to transmigration

During transmigration, the nucleus can divide the cell into two parts with a pressure difference between these parts created by the cortical membrane tension in the front and rear cytosolic compartments. For simplicity, we assume that the membrane tension is uniform and that the front and rear cytosol compartments are both spherical, with radii and , respectively (Fig. 2 d). The pressure difference (rear − front) can be estimated as , where is the actin cortical tension. Recently, it has been shown that the nucleus partitions the cytoplasm after the cell transports the majority of its cytosol to the front (3). As a result, , and , indicating that membrane tension creates a positive pressure difference that pushes the nucleus from the back to assist transmigration. To study the effect of membrane tension and back pressure from the cytosol, we consider an extreme case in which the cell translocates almost all cytosol before nuclear transmigration, meaning that and , which is commonly seen in our experiments with very small gap sizes. To estimate the pressure difference, we consider a cortical actin tension of based on a previous study (35). The additional driving force due to cytosolic pressure is , where is the endothelial gap radius in the current state (Fig. 2 d). For a certain gap size and mechanical properties of different components, although the resistance force stays the same, the required active contractile force for successful transmigration can be smaller when considering this cytosolic back pressure . Therefore, cytosolic back pressure from membrane tension promotes transmigration.

Effects of compressibility and NE permeability on nuclear volume change

The biochemical interactions of the nuclear proteins are dependent on the amount of accessible water that regulates the levels of pH and ionic strength and the concentration of different chemical species within the nucleus. We considered water displacement in and out of the nucleus (through pores), but also the redistribution of water within the nucleus as it is compressed locally. The structural organization and function of nuclear macromolecules rely on the physical and thermodynamic interactions between different nuclear components and the excluded volume effects of macromolecular crowding. The change in water concentration within the nucleus can be directly correlated to the nuclear volume change through

where is the water concentration in the reference state before transmigration and is the volume per water molecule. Therefore, considering its implications on excluded volume effects, as well as water concentration and redistribution, here we investigate the changes in nuclear volume during transmigration. We estimated the normalized nuclear volume change as a function of the normalized nuclear position with respect to the gap considering different constriction sizes. Our model predicts that the nucleus undergoes substantial shape change during transmigration, leading to significant volume decrease (Fig. 3, a and c). The experimental model confirmed the large variations in shape (Fig. 3 b) but did not find significant changes in the nuclear volume (25), but accurate volume measurements are difficult to obtain even using high-resolution 3-D confocal microscopy. In the case of relatively small gaps ( = 0.5 ), the predicted shape change and volume decrease (∼24%) are dramatic, leading to significant fluid efflux that influences the water concentration and macromolecular crowding (Fig. 3 c). For larger gaps, though the overall volume change is small (∼13% (Fig. 3 c)), there is still large reduction (∼20% (Fig. 3 d)) in localized fluid volume (dilatation), leading to a decrease in the amount of accessible water locally.

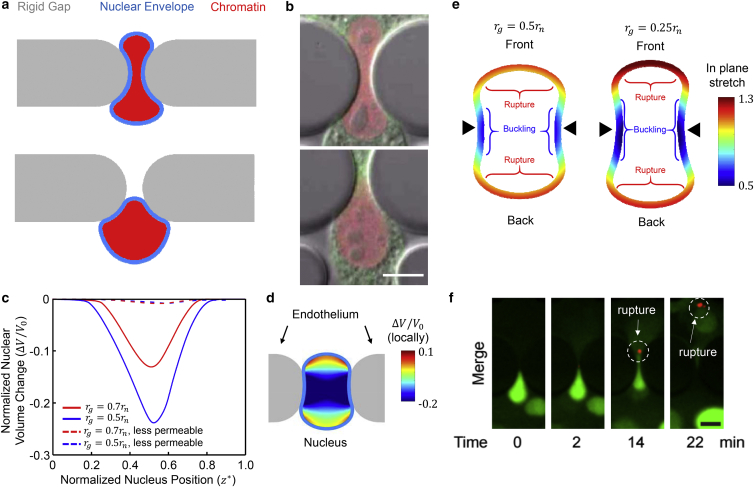

Figure 3.

Nuclear shapes, spatial distribution of volumetric strains and fluid content as well as nuclear envelope deformation and rupture. (a) Snapshots of the nuclear shapes at different stages of transmigration through a small rigid gap . (b) Nuclear shapes in experiments on cell migration through constrictions in a microfluidic device. The nucleus is labeled by mCherry-Histone4 (red) and the cytoplasm by GFP-actin (green). Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) The normalized nuclear volume change as a function of nuclear position. The nucleus experiences large volumetric strains due to fluid expulsion when it passes through smaller gaps. The model predicts up to ∼24% decrease in nuclear volume during transmigration for the smallest gap . Also the effect of nuclear permeability on volume change is shown. (d) The local volume change (dilatation) exhibits large spatial variations within the nucleus. Contours show the normalized local volumetric strain for a permeable nucleus passing through a gap size of (red line in (c)), with blue representing regions with large volume decrease. (e) In-plane stretch just before the nucleus exits the endothelial gap for (left) and (right) (only the NE is shown). The in-plane stretch of the NE is inhomogeneous, with the front and back of the lamina being under tension (potential location of lamina rupture and bleb formation) while the side of the nucleus in contact with the gap is under compression (potential locations for lamina buckling). Black triangles indicate the gap center. (f) Representative time-lapse images showing NE rupture at the front of an HT1080 cell passing through a constriction. The NE rupture was visualized by the spill of NLS-GFP (green) into the cytoplasm and the accumulation of the cytoplasmic DNA-binding protein cGAS-RFP (red) at the site of rupture at the NE. Scale bar, 10 μm. Model parameters for (a), (c), (d), and (e) are kPa, kPa, Pa, kPa, kPa, and kPa. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also investigated the effects of decreasing the nucleus permeability, thereby impeding fluid outflow and redistribution. To address the effects of permeability, we considered changing the “dry” Poisson ratio (Poisson ratio of the solid phase in the poroelastic material). Considering values close to 0.5 for the dry Poisson ratio (set as 0.49) suggests an almost nonpermeable NE with minimal chances of fluid outflow. In this case, and as expected, the overall volume changes (∼1%) are significantly reduced compared to the permeable cases (Fig. 3 c). A recent study showed that the nuclei of fibroblasts (NIH 3T3) undergo a small volume decrease (<10%) while migrating through tight spaces, implying limited fluid flow from the nucleus to the cytosol (25). This suggests that the dry Poisson’s ratio of the nuclei studied here is close to 0.5.

Prediction of lamina buckling and rupture

The NE controls protein trafficking between the cytoplasm and the nucleoplasm and is essential for protecting the chromatin from being exposed to the cytoplasm. Recently it has been shown that rupture of the NE during cell migration through rigid constrictions can potentially lead to herniation of chromatin across the NE and breaking of DNA double strands (12, 13). The rupture and blebs are often found at defective sites in the NE where the nuclear lamina signal was weak or absent (13). Interestingly, the occurrences of these events were also associated with the size of the constriction, which influences the degree of nuclear deformation (13). Therefore, we studied the spatial distribution of strains in the NE and predicted possible locations for NE rupture and buckling as the result of large nuclear deformation during transmigration. The in-plane stretch of the NE is inhomogeneous, with the front and back of the lamina being under tension while the side of the nucleus in contact with the gap is under compression (Fig. 3 e). As a result, the lamina can rupture in the tensile regions, which in turn can lead to nuclear blebbing (Fig. 3 e). Also in the regions where the lamina is under compression, buckling of the NE has been reported (13, 25, 36). Using a device to apply controlled compression on the cell, the precise threshold of deformation above which the nuclear lamina ruptures has been found and correlated with the expression of specific sets of genes, including those involved in DNA damage repair (37). From these experimental data (37), we estimated the threshold of in-plane stretch (stretch = 1 + in-plane strain) for NE rupture to be ∼1.2. Although the cells pass through small gaps, our model predicts a maximal in-plane stretch of ∼1.3, which exceeds the experimentally measured threshold, indicating the cells are under high risk of NE rupture during transmigration. The in-plane stretch at the front is higher than the stretch at the back (Fig. 3 e), suggesting that the front of the nucleus has a higher chance of rupture, which is consistent with recent findings (13) indicating that 70% of NE rupture events occur at the front of the nucleus during the process of cancer cell migration through confined environments (Fig. 3 f). As the gap size increases from to , the maximum in-plane stretch decreases from 1.3 to 1.1, corresponding to a lower likelihood of NE rupture, which is consistent with the positive correlation between NE rupture and smaller constriction size reported with a microfluidic migration device (13).

Pulling forces as the primary mechanism of transmigration

A recent study identified cortical actin filaments at the back of the cell that can generate pushing forces at the rear of the nucleus that may facilitate transmigration (38). To investigate the role of forces acting on the rear of the nucleus, we dissected the influence of push and pull forces and tested whether push forces acting on the rear of the nucleus can explain the shape and distribution of strain during transmigration. We estimated the maximal and minimal principal strains while mapping them at different stages of transmigration through rigid constrictions of different sizes (Fig. 4 a and b). Also, we considered the cases of having either purely pushing forces at the rear of the nucleus or pulling forces on the front (Fig. 4, a and b). For all cases, we found that is mostly in the direction of transmigration, whereas is aligned approximately perpendicular to the transmigration direction.

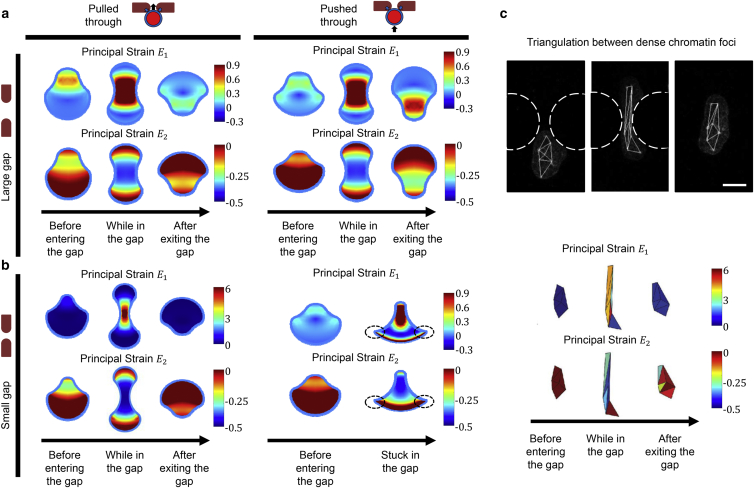

Figure 4.

Nuclear strains during transmigration. (a and b) Graphical representation of spatial distributions of strains in the nucleus at different stages of transmigration through large (a) (rg = 0.5 rn) and small (b) (rg = 0.25 rn) rigid constrictions under either pushing (left) or pulling (right) forces. (c) The experimental strain maps of lamin A/C-deficient cells (bottom) based on triangulation between present dense chromatin foci (top), adapted from (25) with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. Scale bar, 10 μm. Model parameters are K=1 kPa, ρ0 = 0.5 kPa, β = 2.77 × 10−3 Pa, μn = 5 kPa, μt = 5 kPa. To see this figure in color, go online.

For a relatively large constriction, we find that the nucleus adopts an hourglass shape whether it is pulled by frontal actomyosin forces or pushed by rear cytosolic forces (Fig. 4 a). This hourglass shape has been observed in various cell migration experiments (8, 13, 25, 39). Interestingly, our model predicts that and are mostly tensile and compressive, respectively, consistent with the experimental patterns of strain maps derived based on the triangulation between the individual, naturally present dense chromatin foci (Fig. 4 c) (25). However, for a smaller constriction, the nucleus still adopts an hourglass shape when it is pulled through, whereas the pushing at its rear results in an inverted bolt shape (Fig. 4 b) and the appearance of a large compressive that has not been observed in the experiments (Fig. 4 b). Furthermore, in the case of small gaps, our simulations suggest that purely pushing forces cannot lead to a successful transmigration, and the nucleus remains stuck in the gap. Therefore, pulling from actomyosin forces at the front of the nucleus appears to be the primary driving mechanism of transmigration, particularly for small constrictions.

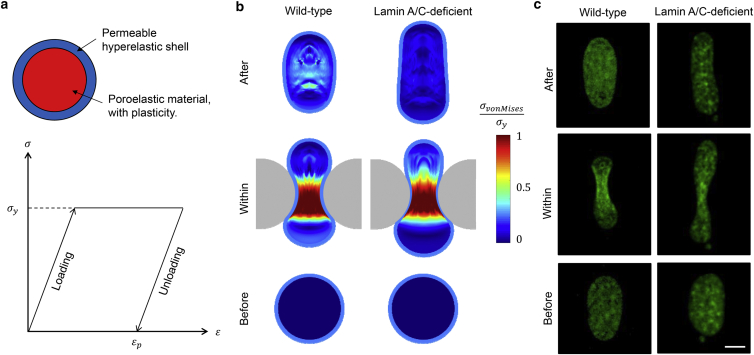

Effects of plasticity on irreversible nuclear deformations

Previously, Pajerowski et al. reported that cell nuclei experience irreversible deformation after release of pressure applied by a micropipette (15). A later study showed evidence that dynamic loading of the nucleus can lead to permanent structural changes in chromatin (40). Since these studies indicate the existence of significant plastic nuclear deformations, we studied the plastic behavior of the nucleus by treating the filling material (representing the chromatin) as an ideal plastic material (which is the extreme limit of a shear thinning material), with no strain hardening after yielding (Fig. 5 a), and the NE as a permeable hyperelastic shell. An ideal plastic material shows an elastic response when the stress is below the yield stress; it undergoes plastic (permanent) deformation without any increase in stresses beyond the yield stress (note that we ignored the effect of hydrostatic pressure on plastic flow, since it does not influence the qualitative trends). The representative nuclear shapes, together with the contour plots of the normalized von Mises stress (with respect to the yield stress, ) during transmigration through a relatively small rigid constriction , are shown in Fig. 5 b, left. Due to the presences of stresses that exceed the yield stress, the interior of the nucleus undergoes plastic deformation while the elastic properties of the NE still work toward restoring nuclear shape, leading to a permanent prolate ellipsoid shape after the nucleus exits the constriction, which is very similar to experimental observations (Fig. 5 c, left). This conflict between the respective elastic and plastic deformations of the NE and the chromatin results in an inhomogeneous residual stress within the nuclear interior after complete transmigration (Fig. 5 b, left).

Figure 5.

Impact of chromatin plasticity and lamina stiffness on nuclear shapes after transmigration. (a and b) The nucleus changes its shape from a spheroid to a prolate ellipsoid during transmigration when plastic nuclear matter is considered. (a) Chromatin is assumed to be ideally plastic, with no strain hardening after yielding. The stress-strain response of the chromatin is shown at the bottom. (b) Normalized von Mises stresses (measured relative to the yield stress ) of the nuclear matter during transmigration through a rigid constriction for wild-type (left) and lamin-A/C-deficient (right) cells. Due to the presence of stresses that exceed the yield stress, the nucleus undergoes plastic deformation leading to permanent change in shape after exiting the constriction. Lamin-A/C-deficient cells undergo larger irreversible shape change than wild-type cells. Model parameters are kPa and . (c) Representative nuclear shapes during different stages of transmigration for wild-type (left) and lamin-A/C-deficient (right) cells, indicating larger irreversible nuclear shape change for lamin-A/C-deficient cells compared to wild-type controls, consistent with the simulations. The nucleus is labeled by H2B-mNeon (green). Scale bar, 10 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Experimentally, it has been shown that the nuclei of cells lacking lamin A/C exhibit larger irreversible shape changes after moving through tight spaces (25, 34) (Fig. 5 c, right). To capture the effects of lamin A/C deficiency on plastic deformation and final shape of the nucleus, we considered a compliant NE that is significantly softer (90% softer; Fig. 5 b, right) than the control, which represents the wild-type NE with normal levels of lamin A/C (Fig. 5 b, left). The nuclei of lamin-A/C-deficient cells undergo much larger irreversible deformation, with a significantly larger nuclear aspect ratio of 2.06 compared to that of wild-type cells, which is 1.52 (Fig.5 b, left and right). Due to the softer NE, the residual stress within the chromatin decreases and shows a more homogenous distribution after the cell fully exits the constriction compared to wild-type cells. These predictions from our model are in excellent agreement with our experimental data (Fig. 5 c) indicating that after transmigration the nuclear aspect ratio increases by ∼2.2 = 3.78/1.74-fold (where 3.78 and 1.74 are the aspect ratios before and after transmigration, respectively) for the case of lamin-A/C-deficient cells, which is significantly larger than the increase for wild-type cells (∼1.15 = 2.12/1.85-fold). Taken together, our model predictions confirm that lamin A/C regulates nuclear deformability and that nuclei lacking lamin A/C are more plastic and undergo larger irreversible deformation than nuclei from wild-type cells.

Discussion

Focusing on nuclear mechanics, we used a chemomechanical model to study the ability of cells to pass through tight interstitial spaces depending on the mechanical and geometrical features of the cell and the extracellular environment. We predicted that cells transmigrate more easily with a stiff ECM and a large endothelial/constriction gap (Fig. 2 c) and estimated the minimal actomyosin contraction force required for transmigration of the nucleus. Indeed, recent experiments suggest that the cells are not able to transmigrate either when contractility (41, 42) is abolished or when nesprin links (42) and/or integrins (4) are inhibited. Cells also deform the endothelium and create larger openings to facilitate transmigration (Fig. S6), which implies that the endothelial cells around the opening are under compression, leading to rupture of cell-cell adhesions within the endothelium. We also quantitatively investigated the influence of transmigration on cell nuclei, including nuclear shapes, chromatin deformations, and NE deformations. Our results predict nuclear shape profiles that closely agree with both our experimental observations and previously published data (8, 9, 13, 25). Furthermore, investigating the nuclear profiles and the distribution of strain within the nucleus, we conclude that the primary driving forces (particularly for transmigration through small gaps) are those that pull the nucleus from the front. This is consistent with the experimental observations of dense regions of actin at the leading edges of cell protrusions extending into the subendothelial ECM during tumor cell extravasation (4). Considering plasticity associated with chromatin structure (40), we captured the effects of irreversible nuclear shape changes (Fig. 5) and verified recent observations suggesting that cells lacking lamin A/C are more deformable and undergo more plastic deformations (34).

Our model further predicted that transmigration places extensive physical stress on the nucleus and the NE, particularly at the leading edge, and that the in-plane stretch of the NE can exceed the critical stretch value of ∼1.2, placing cells at high risk of NE rupture during transmigration. A major function of the NE is to act as a barrier separating chromatin from the cytoplasm, with nucleocytoplasmic exchange closely controlled by the nuclear pore complex. Transmigration-induced rupture of the NE exposes the genomic DNA to normally cytoplasmic factors (Fig. 3 f), including nucleases, which could result in DNA damage, as observed in recent studies (12, 13). Although cells in those studies were generally able to tolerate NE rupture and DNA damage, combined inhibition of ESCRT-III-mediated NE repair and DNA-damage repair pathways substantially increased the rate of cell death during transmigration (12, 13), highlighting the importance of maintaining NE integrity during migration. Importantly, some cells also exhibit DNA damage during transmigration through small constrictions even without NE rupture (12). In these cases, DNA damage could result from mechanical straining of the chromatin and/or from volume changes of the nucleus. Our model and experimental data indicate that during transmigration, the nucleus undergoes significant shape changes (Fig. 3 a) associated with large intranuclear strains (Fig. 4) that impose substantial mechanical stress on the chromatin, which may be sufficient to induce DNA damage. Nuclear volume changes and (local) efflux of water and soluble nuclear components could further contribute to DNA damage. A previous study found that loss of DNA repair enzymes can potentially lead to irreversible DNA damage (43). These enzymes are small molecules and their activity is highly dependent on the distribution and the amount of water accessible to them within the nucleus. Our model predicts an overall volume decrease of up to 24%, which could be sufficient to induce DNA damage by water redistribution and the local loss of DNA repair enzymes.

Our model provides support for the existence of all three mechanisms, which could occur alone or in combination. Currently, the relative contribution of NE rupture, chromatin strain, and nuclear volume change for DNA damage incurred during transmigration remains unclear. Predictions from our model regarding the expected localization of DNA damage, depending on the specific DNA damage mechanism, may be used in combination with quantitative, high-resolution time-lapse imaging experiments to fully elucidate the molecular and biophysical details of DNA damage during transmigration.

Although these observations pertain specifically to tumor cell transendothelial migration, they are widely applicable to any situation in which a cell needs to pass through narrow constrictions, such as during migration through interstitial spaces (typically ranging from 2 to 20 μm). Note, however, that in the current simulations, the monolayer gap size at zero stress is taken as fixed, whereas in the case of the endothelial monolayer, it will vary with the degree to which cell-cell adhesions rupture due to the forces generated during transmigration. Nonetheless, in the particular case of TEM, these findings may have important implications with respect to the tendency of tumor cells to survive and proliferate once they extravasate into tissue from the vascular system. Studies are therefore needed to investigate changes in the phenotype of cells that have undergone TEM.

Conclusions

In summary, we proposed a model for cell transmigration that provides testable predictions, which are in accord with our experiments and the existing literature. The model addresses key factors such as nuclear shape change and nuclear strain, which are crucial to determine the ability of cancer cells to invade and move through the surrounding matrix and which may also help predict the anticipated extent of DNA damage. By tuning the model parameters, our simulations can be adapted to understand cell transmigration for other cells and matrix systems. This work therefore provides a framework to assess the roles of mechanical and geometric features on cell migration across monolayers and through 3D matrices.

Author Contributions

X.C., X.W., and V.B.S. formulated the mathematical framework for the chemomechanical model; X.C. carried out the computations; E.M., P.I., P.M.D., M.B.C., J.L., and R.D.K. designed the experiments. E.M., P.I., P.M.D., and M.B.C. conducted the experiments. All authors interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute under award nos. U01CA202177 (to R.D.K. and V.B.S), U54CA193417 (to V.B.S.) and U54CA143876 (to J.L. through the Cornell Center on Microenvironment and Metastasis); the National Institutes of Health under award nos. R01EB017753 (to V.B.S.) and R01HL082792 (to J.L.); the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program under award nos. BC102152 and BC150580 (to J.L.); and the National Science Foundation under award no. CBET-1254846 (to J.L.). This work was performed in part at the Cornell NanoScale Science and Technology Facility, which is supported by the National Science Foundation (grant ECCS-15420819). E.M. is grateful for the financial support through a Wellcome Trust-Massachusetts Institute of Technology Fellowship (grant WT103883).

Editor: Alissa Weaver.

Footnotes

Six figures and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30698-1.

Supporting Citations

References (44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Reymond N., d’Água B.B., Ridley A.J. Crossing the endothelial barrier during metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2013;13:858–870. doi: 10.1038/nrc3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madsen C.D., Sahai E. Cancer dissemination—lessons from leukocytes. Dev. Cell. 2010;19:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen M.B., Whisler J.A., Kamm R.D. Mechanisms of tumor cell extravasation in an in vitro microvascular network platform. Integr. Biol. (Camb) 2013;5:1262–1271. doi: 10.1039/c3ib40149a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M.B., Lamar J.M., Kamm R.D. Elucidation of the roles of tumor integrin β1 in the extravasation stage of the metastasis cascade. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2513–2524. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedl P., Wolf K., Lammerding J. Nuclear mechanics during cell migration. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011;23:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moeendarbary E., Valon L., Charras G.T. The cytoplasm of living cells behaves as a poroelastic material. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nmat3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charras G., Sahai E. Physical influences of the extracellular environment on cell migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson P.M., Denais C., Lammerding J. Nuclear deformability constitutes a rate-limiting step during cell migration in 3-D environments. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2014;7:293–306. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0342-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf K., Te Lindert M., Friedl P. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J. Cell Biol. 2013;201:1069–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada T., Swift J., Discher D.E. Nuclear lamin stiffness is a barrier to 3D migration, but softness can limit survival. J. Cell Biol. 2014;204:669–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201308029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson P.M., Lammerding J. Broken nuclei—lamins, nuclear mechanics, and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raab M., Gentili M., Piel M. ESCRT III repairs nuclear envelope ruptures during cell migration to limit DNA damage and cell death. Science. 2016;352:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denais C.M., Gilbert R.M., Lammerding J. Nuclear envelope rupture and repair during cancer cell migration. Science. 2016;352:353–358. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilak F., Tedrow J.R., Burgkart R. Viscoelastic properties of the cell nucleus. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;269:781–786. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pajerowski J.D., Dahl K.N., Discher D.E. Physical plasticity of the nucleus in stem cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15619–15624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702576104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher D.A., Mullins R.D. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 2010;463:485–492. doi: 10.1038/nature08908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moeendarbary E., Harris A.R. Cell mechanics: principles, practices, and prospects. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2014;6:371–388. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janmey P.A., McCulloch C.A. Cell mechanics: integrating cell responses to mechanical stimuli. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2007;9:1–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panorchan P., Schafer B.W., Tseng Y. Nuclear envelope breakdown requires overcoming the mechanical integrity of the nuclear lamina. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43462–43467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swift J., Ivanovska I.L., Discher D.E. Nuclear lamin-A scales with tissue stiffness and enhances matrix-directed differentiation. Science. 2013;341:1240104. doi: 10.1126/science.1240104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shenoy V.B., Wang H., Wang X. A chemo-mechanical free-energy-based approach to model durotaxis and extracellular stiffness-dependent contraction and polarization of cells. Interface Focus. 2016;6:20150067. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2015.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H., Wen J., Sun Y. In situ mechanical characterization of the cell nucleus by atomic force microscopy. ACS Nano. 2014;8:3821–3828. doi: 10.1021/nn500553z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin D.C., Dimitriadis E.K., Horkay F. Robust strategies for automated AFM force curve analysis—I. Non-adhesive indentation of soft, inhomogeneous materials. J. Biomech. Eng. 2007;129:430–440. doi: 10.1115/1.2720924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bilodeau G.G. Regular pyramid punch problem. J. Appl. Mech. 1992;59:519. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson P.M., Sliz J., Lammerding J. Design of a microfluidic device to quantify dynamic intra-nuclear deformation during cell migration through confining environments. Integr. Biol. (Camb) 2015;7:1534–1546. doi: 10.1039/c5ib00200a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghibaudo M., Saez A., Ladoux B. Traction forces and rigidity sensing regulate cell functions. Soft Matter. 2008;4:1836–1843. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitrossilis D., Fouchard J., Asnacios A. Single-cell response to stiffness exhibits muscle-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18243–18248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903994106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H., Abhilash A.S., Shenoy V.B. Long-range force transmission in fibrous matrices enabled by tension-driven alignment of fibers. Biophys. J. 2014;107:2592–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abhilash A.S., Baker B.M., Shenoy V.B. Remodeling of fibrous extracellular matrices by contractile cells: predictions from discrete fiber network simulations. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1829–1840. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon H., Kim E., Grigoropoulos C.P. Measurement of contractile forces generated by individual fibroblasts on self-standing fiber scaffolds. Biomed. Microdevices. 2011;13:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9475-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahl K.N., Kahn S.M., Discher D.E. The nuclear envelope lamina network has elasticity and a compressibility limit suggestive of a molecular shock absorber. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4779–4786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lammerding J., Fong L.G., Lee R.T. Lamins A and C but not lamin B1 regulate nuclear mechanics. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:25768–25780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lammerding J., Schulze P.C., Lee R.T. Lamin A/C deficiency causes defective nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:370–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI19670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rowat A.C., Jaalouk D.E., Lammerding J. Nuclear envelope composition determines the ability of neutrophil-type cells to passage through micron-scale constrictions. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8610–8618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salbreux G., Charras G., Paluch E. Actin cortex mechanics and cellular morphogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim D.-H., Li B., Sun S.X. Volume regulation and shape bifurcation in the cell nucleus. J. Cell Sci. 2015;128:3375–3385. doi: 10.1242/jcs.166330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Berre M., Aubertin J., Piel M. Fine control of nuclear confinement identifies a threshold deformation leading to lamina rupture and induction of specific genes. Integr. Biol. (Camb) 2012;4:1406–1414. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20056b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norden C., Young S., Harris W.A. Actomyosin is the main driver of interkinetic nuclear migration in the retina. Cell. 2009;138:1195–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim M.-C., Neal D.M., Asada H.H. Dynamic modeling of cell migration and spreading behaviors on fibronectin coated planar substrates and micropatterned geometries. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1002926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poh Y.-C., Shevtsov S.P., Wang N. Dynamic force-induced direct dissociation of protein complexes in a nuclear body in living cells. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:866. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoletov K., Kato H., Klemke R. Visualizing extravasation dynamics of metastatic tumor cells. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:2332–2341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas D.G., Yenepalli A., Egelhoff T.T. Non-muscle myosin IIB is critical for nuclear translocation during 3D invasion. J. Cell Biol. 2015;210:583–594. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201502039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karschau J., de Almeida C., de Moura A.P.S. A matter of life or death: modeling DNA damage and repair in bacteria. Biophys. J. 2011;100:814–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.12.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fawcett D.W. On the occurrence of a fibrous lamina on the inner aspect of the nuclear envelope in certain cells of vertebrates. Am. J. Anat. 1966;119:129–145. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001190108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall M. Bulk modulus of a fluid−filled spherical shell. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1975;57:508–510. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerlitz G., Bustin M. Efficient cell migration requires global chromatin condensation. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:2207–2217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.058271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Century T.J., Fenichel I.R., Horowitz S.B. The concentrations of water, sodium and potassium in the nucleus and cytoplasm of amphibian oocytes. J. Cell Sci. 1970;7:5–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.7.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abu-Arish A., Kalab P., Fradin C. Spatial distribution and mobility of the Ran GTPase in live interphase cells. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2164–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caille N., Thoumine O., Meister J.-J. Contribution of the nucleus to the mechanical properties of endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 2002;35:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng D., Juzkiw T., Johnson M. Young’s modulus of elasticity of Schlemm’s canal endothelial cells. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2010;9:19–33. doi: 10.1007/s10237-009-0156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomasy S.M., Raghunathan V.K., Murphy C.J. Elastic modulus and collagen organization of the rabbit cornea: epithelium to endothelium. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:785–791. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chiron S., Tomczak C., Coirault C. Complex interactions between human myoblasts and the surrounding 3D fibrin-based matrix. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang H., Svoronos A.A., Shenoy V.B. Necking and failure of constrained 3D microtissues induced by cellular tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:20923–20928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313662110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pellegrin S., Mellor H. Actin stress fibres. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3491–3499. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawada Y., Tamada M., Sheetz M.P. Force sensing by mechanical extension of the Src family kinase substrate p130Cas. Cell. 2006;127:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puklin-Faucher E., Sheetz M.P. The mechanical integrin cycle. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:179–186. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katoh K., Kano Y., Fujiwara K. Rho-kinase-mediated contraction of isolated stress fibers. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:569–584. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matthews B.D., Thodeti C.K., Ingber D.E. Ultra-rapid activation of TRPV4 ion channels by mechanical forces applied to cell surface beta1 integrins. Integr. Biol. (Camb) 2010;2:435–442. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00034e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reference deleted in proof.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.