Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively investigate the reliability of breast ultrasound (US) Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) final assessment in mammographically negative patients with pathologic nipple discharge, and to determine the clinical and ultrasonographic variables associated with malignancy in this group of patients.

Methods

A total of 65 patients with 67 mammographically negative breast lesions that were pathologically confirmed through US-guided biopsy were included.

Results

Of the 53 BI-RADS category 4 and 5 lesions, eight (15.1%) were malignant (six ductal carcinomas in situ, one invasive ductal carcinoma, and one solid papillary carcinoma). There was no malignancy among the remaining 14 category 3 lesions. Malignant lesions more frequently displayed a round or irregular shape (75.0%, 6/8; p=0.030) and nonparallel orientation (33.3%, 4/12; p=0.029) compared to the benign lesions. The increase in the BI-RADS category corresponded with a rise in the malignancy rate (p=0.004).

Conclusion

The BI-RADS lexicon and final assessment of breast US reliably detect and characterize malignancy in mammographically negative patients with pathologic nipple discharge.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Galactorrhea, Mammography, Ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Nipple discharge is a symptom that commonly occurs in 4.8% to 7.4% of patients that are referred to breast clinics [1,2,3]. Although intraductal papilloma is the most common underlying cause of pathologic nipple discharge [4], previous studies have reported the incidence of breast cancer at 2.8% to 21.3% in these women [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Thus, the development of a reliable diagnostic strategy for detecting malignancy are important goals. Initial evaluation with physical examination and mammography in patients with bloody nipple discharge is useful for detecting high-risk cases [12]. However, the ability of mammograms to detect intraductal lesions is limited, and other diagnostic procedures such as galactography and ultrasound (US), have also been proposed. Breast US is a valuable, noninvasive imaging method that can be used to evaluate the morphologic features of a breast mass and its relationship to adjacent ductal structures in patients with dense breast tissue [5]. Furthermore, US is a useful adjunct after mammography for the detection of nonpalpable breast cancer, particularly in dense breasts. One study reported that 32% of nonpalpable breast cancers were negative on mammography and could be detected only by US [13]. However, to our knowledge only a few studies have assessed the role of US in detecting nonpalpable breast cancer specifically in mammographically negative patients presenting with pathologic nipple discharge. Therefore, accurate interpretation of findings is essential for lesions that are only detectable by US.

The US Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) is widely used in conjunction with its final assessment to predict the probability that a targeted breast lesion is malignant [14]. However, BI-RADS and its final assessment do not contain a detailed lexicon that describes the morphology of ductal involvement, which is common in patients with pathologic nipple discharge. Also, there are no clear guidelines on what sonographic variables differentiate malignancy from benign etiology based on clinical and radiologic assessment.

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively investigate the reliability of breast US BI-RADS final assessment and US-guided biopsy in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge, and to determine the clinical and ultrasonographic variables associated with malignancy.

METHODS

Patient selection

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our institution, Yonsei University Medical Center, Severance Hospital, South Korea (IRB number: 4-2015-0286). The requirement for informed consent was waived.

Study population

Using a computerized search of the database, all breast US performed for patients presenting with symptoms of pathologic nipple discharge were located. Pathologic nipple discharge was defined as any unilateral and spontaneous clear discharge, or discharge with blood. From December 2009 to December 2014, a total of 222 patients presenting only with pathologic nipple discharge underwent diagnostic US. Among these women, 11 had bilateral pathologic nipple discharge.

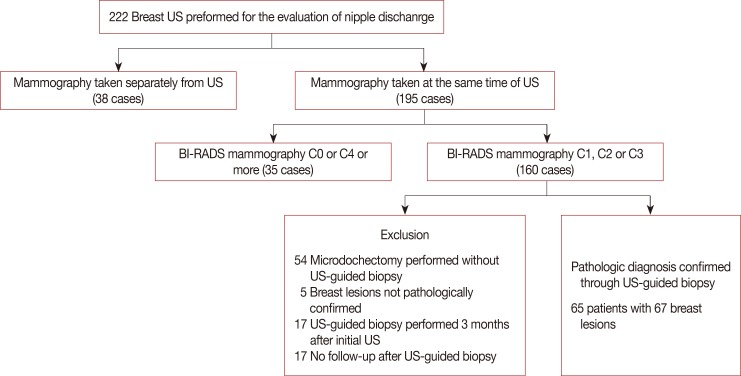

Patients were excluded from the study if mammography results were considered positive when there was a detectable lesion and further evaluation or biopsy was recommended (BI-RADS categories: 0, 4 or 5; n=35 breasts in 35 patients). Patients who did not undergo mammography at the time of US were also excluded (n=38 breasts in 31 patients). Among the remaining 160 mammographically negative breasts, 54 breasts which underwent microdochectomy without US-guided biopsy, five breast lesions which were not pathologically confirmed, and 17 breast lesions whose US-guided biopsy was performed later than 3 months after the initial US (n=17) were excluded. Additionally, 17 breasts that had no imaging follow-up for at least 2 years after US-guided biopsy were also excluded. Therefore, the final study population included 65 patients with 67 mammographically negative breast lesions that were pathologically confirmed through US-guided biopsy and underwent subsequent surgery or follow-up for at least 2 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study investigating the reliability of breast ultrasound Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) final assessment in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge and radiologic predictors of malignancy.

US=ultrasound.

Image evaluation and biopsy

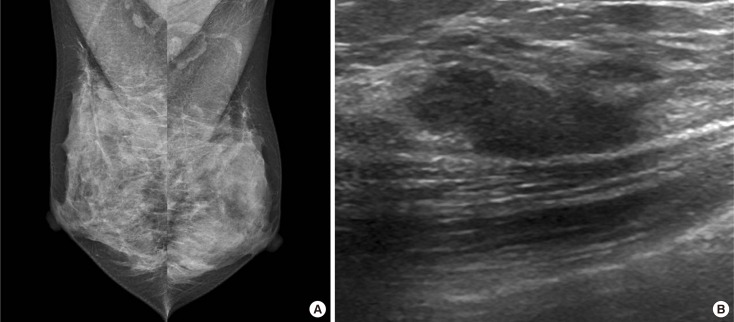

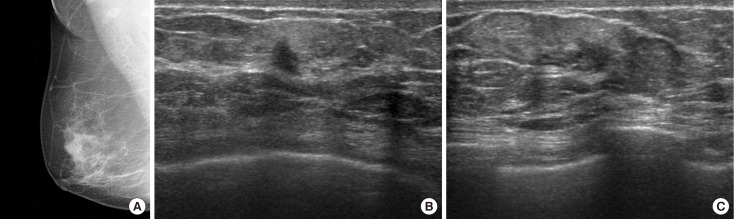

Mammography was performed using one of two dedicated full-field digital mammography units (Senographe 2000D, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA; or Lorad/A Hologic, Danbury, USA). Standard craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views were routinely obtained, and additional mammographic views were obtained as needed. Breast parenchymal pattern was assessed and recorded according to BI-RADS as follows: entirely fatty breast (A), scattered fibroglandular tissue (B), heterogeneously dense (C), or extremely dense (D) [15]. All patients underwent US examination using high-resolution US units with 5- to 10-MHz or 5- to 12-MHz linear-array transducers (HDI5000, Philips Advanced Technology Laboratories, Bothell, USA; Logic 9, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, USA; or iU22, Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, USA). Bilateral whole-breast scanning was performed at every examination, with the patient in the supine position and the patient's arm raised above the head. B-mode with spatial compound imaging was used as the default; Doppler and harmonic imaging were used if necessary. Depending on breast tissue composition and thickness, the US frequency (MHz) and the amount of compound imaging were adjusted to enhance spatial resolution or tissue penetration. Breast US examinations were performed by one of 15 board-certified radiologists with 1 to 15 years of experience in breast imaging. The radiologist performing the US determined the final assessment category according to BI-RADS by assessing the lesion characteristics by BI-RADS lexicon (Figures 2, 3) [15].

Figure 2. Radiologic findings of a 38-year-old woman with a several-week history of spontaneous serous discharge from the right nipple. (A) Mediolateral mammography of the both breast shows dense breasts with no abnormalities to explain right nipple discharge (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System [BI-RADS] category 1). (B) Longitudinal ultrasound images show a 2.0 cm sized isoechoic, oval shaped, microlobulated mass with parallel orientation which was located at 1 o'clock 2 cm from nipple (BI-RADS category 3). Ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy was performed and the pathologic result was consistent with fibrocystic disease with stromal fibrosis. After the procedure, the patient had no persistent nipple discharge, and no malignancy was detected during a 2-year follow-up period.

Figure 3. Radiologic findings of a 73-year-old woman with a 1-week history of spontaneous bloody discharge from the right nipple. (A) Mediolateral mammography of right breast shows no definite abnormality to explain right bloody nipple discharge. Transverse (B) and longitudinal (C) ultrasound images of the right breast show a 1.0 cm sized isoechoic, irregularly shaped, spiculated mass with nonparallel orientation (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System category 5) which was located at 8 o'clock 1 cm from nipple. Ultrasound-guided biopsy was performed, and the pathologic result was consistent with ductal carcinoma in situ. Subsequent surgery was performed.

For patients with nipple discharge in our hospital, image-guided biopsies were recommended for patients with BI-RADS category 4 or 5 breast lesions identified by mammography or US. Image-guided biopsies were also performed in patients with BI-RADS category 3 if desired by the patient or clinical physician.

US-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed using a 14-gauge automated core needle (Stericut with coaxial; TSK Laboratory, Tochigi, Japan) or an 8- or 11-gauge vacuum-assisted probe (Mammotome; Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, USA), as previously described [16]. Subsequent surgical excisional biopsy was performed under US-guided localization.

Retrospective image review

All US features of the breast lesions were retrospectively reviewed and re-evaluated according to the fifth BI-RADS lexicon (American College of Radiology 2013) [15] by consensus of two dedicated breast imaging radiologists with 1 and 15 years of experience, respectively. The radiologists were blinded to the final pathologic diagnosis of all breast lesions. The final assessment category of breast US BI-RADS was not re-evaluated and was determined prospectively at the time when US was performed.

US features were classified according to BI-RADS lexicon as follows: tissue composition (homogeneous-fat, homogeneous-fibroglandular, or heterogeneous), shape (oval, round, or irregular), orientation (parallel or not parallel), margin (circumscribed, indistinct, angular, microlobulated, or spiculated), echo pattern (anechoic, hyperechoic, complex, hypoechoic, isoechoic, or heterogeneous), posterior features (none, enhancing, or shadowing) and calcification (present or absent).

Furthermore, the ductal involvement pattern was reviewed and classified into three groups: a single mass not associated with a duct, a mass incompletely filling a duct, and a mass completely filling or extending outside the duct [17]. If a lesion was associated with ducts, the ductal wall irregularity was assessed further. There were also single masses that were not intraductal, but showed adjacent ductal dilatation that seemed to have no connection to the mass. Thus, the existence of adjacent ductal dilatation was also recorded. The number of involved branch ducts was noted as zero (0), one (1), two (2) or more. A retrospective review of US images was performed using digitized static images on a 5-MP monochrome display monitor (ME551 i2; Totoku Electric Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) on a picture archiving and communication system.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Clinical and radiologic records were reviewed for patient age, the site of nipple discharge (right, left, or both breasts), lesion size, and distance from the nipple. The radiologists performing the US recorded the direction of nipple discharge, lesion size (maximal diameter), and distance from the nipple.

Follow-up data, including recurrence of nipple discharge, were reviewed by examining medical records. Surgical reports were reviewed to ascertain or rule out malignancy, both at the biopsied lesion and in other aspects of the remaining breast. The reference standards for final diagnosis were based on pathologic results and follow-up records. Patients were considered to have breast cancer if histopathologic reports of percutaneous biopsy or surgical specimens were positive for breast cancer. If biopsy results showed indeterminate pathology such as atypical ductal hyperplasia, information from surgical specimens was regarded as the final pathology. The final diagnosis was considered negative if there was no evidence of malignancy in follow-up imaging or medical record review within 2 years of the initial benign biopsy performed as a radiologic intervention in response to pathologic nipple discharge. The malignancy rate in mammographically occult and sonographically suspicious lesions in patients with pathologic nipple discharge was calculated.

For statistical analysis, Fisher exact tests were performed for comparison of nonparametric variables such as US features, and Mann-Whitney U-tests were performed for comparison of parametric variables, including age, lesion size, and distance from the nipple. Fisher exact test, Mann-Whitney U-test, and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel tests were performed to establish the association between BI-RADS category and malignancy rate.

Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS system for Windows version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, USA). A p-value< 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

In all 67 cases, US-guided core needle biopsy or vacuum-assisted excision was performed for pathologic diagnosis. Among 67 breast lesions, surgery was performed subsequently for 43 breast lesions in 43 patients, for the following reasons: (1) presence of malignancy (n=5); (2) atypical pathologic reports (n=4); (3) complete excisional biopsies for papillary or phyllodes tumor (n=22); and (4) symptom control (n=12). According to surgical reports, no malignancy was identified in these cases, other than at the local site. The remaining 24 patients did not undergo surgery but received clinical or imaging follow-up. The final diagnoses for the 67 breast lesions revealed eight malignancies (six ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS], one invasive ductal carcinoma [IDC], and one solid papillary carcinoma), and 59 benign diseases (31 papillomas, 13 fibrocystic disease, four fibroadenomas, three ductectasias, two atypical ductal hyperplasias, two columnar cell changes, one benign phyllodes tumor, one complex sclerosing lesion, one stromal fibrosis, and one papillary apocrine hyperplasia). Among the eight malignant lesions, three were confirmed to be malignant on surgical excision, and exhibited atypical pathologic features based on the US-guided biopsy. All pathologically proven benign lesions were followed up for 2 years, and no malignancies developed during the follow-up period. Thus, the malignancy rate in mammographically occult and sonographically detected lesions (category 4 and 5) in patients with nipple discharge was 15.1% (8/53).

The ultrasonographic findings of benign and malignant breast lesions in patients with nipple discharge are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 47.5 years (standard deviation, 12.0 years; range, 26–78 years). The lesion size and distance from the nipple were not significantly different between benign and malignant groups (p=0.377 and p=0.568, respectively). Malignant breast lesions more frequently showed round or irregular (75.0%, 6/8) shape compared to benign lesions (32.2%, 19/59; p=0.030). Among 42 oval-shaped lesions, 95.2% (40/42) proved to be benign. Malignant lesions more frequently showed nonparallel orientation (33.3%, 4/12) compared to benign lesions (7.3%, 4/55; p=0.029). However, other radiologic findings (such as the presence of calcifications, tissue composition, margin, echogenicity, and posterior features), were not significantly different between benign and malignant breast lesions.

Table 1. Ultrasonographic findings in benign and malignant breast lesions in patients with nipple discharge.

| Variable | Pathology No. (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (n=59) |

Malignant (n=8) |

||

| Age (yr)* | 46.8±11.3 | 52.5±16.6 | 0.456 |

| Size (cm)* | 1.1±4.2 | 1.4±8.7 | 0.377 |

| Distance from the nipple (cm)† | 1.0 (0.0–6.0) | 1.0 (0.0–7.0) | 0.568 |

| Tissue composition | 0.497 | ||

| Homogeneous fat | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Homogeneous fibroglandular | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | |

| Heterogeneous | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Shape | 0.030 | ||

| Oval | 40 (95.2) | 2 (4.8) | |

| Round | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Irregular | 10 (76.8) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Orientation | 0.029 | ||

| Parallel | 51 (97.7) | 4 (7.3) | |

| Not parallel | 8 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | |

| Margin | 0.278 | ||

| Circumscribed | 21 (95.5) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Indistinct | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Angular | 1 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Microlobulated | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Spiculated | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Echogenicity | 0.609 | ||

| Hypoechoic | 18 (90.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Isoechoic | 32 (84.2) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Mixed (solid and cystic) | 8 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Heterogeneous | 1 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Posterior features | 0.444 | ||

| None | 43 (87.8) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Enhancement | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Shadowing | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Calcification | 1.000 | ||

| None | 56 (87.5) | 8 (12.5) | |

| Microcalcification in mass | 3 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Association with ducts | 0.751 | ||

| Single mass not associated with duct | 34 (85.0)‡ | 6 (15.0)‡ | |

| Mass incompletely filling the duct | 7 (100.0) | 0 | |

| Mass completely filling the duct or extending outside the duct | 18 (90.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Adjacent ductal dilatation | 0.465 | ||

| No | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | |

| Yes | 32 (91.4) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Branch duct | 0.554 | ||

| 0 | 45 (88.2) | 6 (11.8) | |

| 1 | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| 2 or more | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

*Mean±SD; †Median (range); ‡Seven among 34 benign lesions (20.6%) and one among six malignant lesions (16.7%) showed adjacent ductal changes.

The morphologic pattern of duct involvement (the degree of expansion or filling of the duct by the mass) was not significantly different between benign and malignant breast lesions. However, all seven masses that incompletely filled the duct were benign. Of eight malignant lesions, six were single masses showing no association with ducts, and two were intraductal, with one completely filling the duct and one extending outside the duct. Ductal dilatation adjacent to the mass, or the number of involved branch ducts, were not significantly different between benign and malignant groups (p=0.465 and p=0.554, respectively). Among 27 lesions that were associated with ducts, six masses showed irregular ductal wall changes and only one case (16.7%, 1/6) was confirmed as DCIS.

Table 2 shows the BI-RADS category of breast US in both benign and malignant breast lesions. The malignancy rate for each BI-RADS category was as follows: category 3, 0% (0/14); category 4, 13.5% (7/52); and category 5, 100% (1/1). The trend of BI-RADS category was significantly different between the benign and malignant groups (p=0.004). The increase in the BI-RADS category corresponded with a rise in the malignancy rate (p=0.004).

Table 2. Relationship between ultrasound BI-RADS category and pathology in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge.

| Pathology No. (%) |

p-value* | p-value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (n=59) |

Malignant (n=8) |

|||

| BI-RADS category | 0.040 | 0.004 | ||

| 3 | 14 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| 4A | 42 (87.5) | 6 (12.5) | ||

| 4B | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| 5 | 0 | 1 (100.0) | ||

BI-RADS=Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

*Fisher exact test, Mann-Whitney U-test; †Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test.

DISCUSSION

Breast US has conventionally been used as a complement to mammography, as it is useful for lesion detection and characterization in women with dense breasts, without the risk of a radiation hazard. Previous studies have reported that high-resolution US is a valuable diagnostic method in patients with pathologic nipple discharge and is therefore a valuable alternative to galactography [5,18]. To our knowledge, there have been few studies regarding the value of US in mammographically negative patients with pathologic nipple discharge. In our study, the malignancy rate in mammographically-negative and those breast lesions only detected by US was 15.1% (8/53). This value is slightly higher than the previously reported malignancy rate ranging from 11.7% to 12.5% for mammographically-negative breasts with lesions that were only detected by US [5,19]. Our result, even in diagnostic settings with nipple discharge, is in line with previous studies that showed adding a screening US for women with increased risk of breast cancer resulted in an increased number of false-positive findings as well as in an increased cancer detection rate [20,21]. Meanwhile, by adding US and subsequent US-guided biopsy to negative mammogram, 15.1% of malignancy (8/53) was confirmed without another invasive procedure such as galactography prior to surgery.

In our study, among various ultrasound features, round or irregular shape and not parallel orientation of breast lesions were associated with malignancy in patients with pathologic nipple discharge. This finding is consistent with previous studies that reported nodules with irregular shape or nonparallel orientation are likely to be malignant in women with or without nipple discharge [15]. Meanwhile, Nakahara et al. [22] reported that hypoechoic masses with an irregular margin were more likely to be malignant. However, echogenicity showed no significant difference between the benign and malignant group, probably because only mammographically negative lesions were included in our study, as they showed mild radiographic changes. Though excluded in the BI-RADS lexicon, detailed ductal involvement patterns were investigated in our study, as they may be helpful in diagnosing malignancy in patients with pathologic nipple discharge. However, we found that the ductal involvement pattern was not significantly different between benign and malignant breast lesions, which might be due to the small number of intraductal breast lesions examined in our study. There were no malignancies in seven cases of intraductal masses that incompletely filled the duct, consistent with a previous study by Kim et al. [17], who reported no malignancies in a total of 37 intraductal masses incompletely filling the duct. Thus, we can consider US follow-up for masses that incompletely fill the duct. In their study, malignant intraductal masses were more likely to involve the branch duct than benign intraductal masses [17]. However, there was no significant association between malignancy and branch duct involvement in our study, which may be due to the small number of breast lesions involving the branch ducts. Also, there may be a bias in our study due to the limited enrollment of mammographically negative breast lesions. Among eight malignant lesions, six were single masses without visible ductal changes at the ultrasound which does not clearly explain the symptom of pathologic nipple discharge. This result suggests that even in the patients with nipple discharge, masses might be seen without detectable associated ductal changes. The ductal changes might be not well delineated at the time of US if the symptom of nipple discharge is intermittent rather continuous. However, we did not assess whether the nipple discharge is intermittent or not in each patient and its association with malignancy. Besides, considering the fact that all the lesions were not detected at the mammography, these masses might accompany less positive findings also at the US. Our study at least suggests that in the patients with nipple discharge showing negative mammogram, the masses could be seen without expected ductal changes and there is also possibility of malignancy in these cases.

Previous studies have shown that the sensitivity of breast US in patients with nipple discharge ranged from 36% to 80% [5,19,23,24]. In our study, all mammographically negative malignant lesions were detected by US, at a sensitivity of 100%. There are several possible reasons for the high US sensitivity in our study. First, all the US BI-RADS category 1 or 2 lesions for which the US guided biopsy was not performed were excluded in our study. Also, breast lesions that were only confirmed through surgery without US-guided biopsy were also excluded; therefore, the sensitivity of breast US may have been lower if malignancy were detected in these excluded cases. Thus, the high sensitivity of breast US could be largely explained by our study design, which is one of the limitations of the study. However, among the benign lesions at biopsy, there was no malignancy other than the biopsied lesions, which suggests that US accurately detected the most suspicious lesions in each breast accurately. Furthermore, applying the BI-RADS lexicon and final assessment during US interpretation [15] may have also led to the high sensitivity of US in our study. Previous studies of US in patients with nipple discharge were conducted before [24] or during [5,23] US BI-RADS publication. Additionally, only specialized breast radiologists who routinely perform at least 300 breast US exams per month in our institution were involved, which may explain the high sensitivity of breast US in our study.

In patients with pathologic nipple discharge, higher US BI-RADS categories correlated with increased malignancy rates. Also, the malignancy yield rate for each category was comparable to the likelihood of malignancy rate [25]. Although the current BI-RADS lexicon and final assessment have not been well established in the evaluation of intraductal lesions [17,26], our results suggest that BI-RADS reliably predicts malignancy as far as US detects positive findings in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge.

It has been reported that adding US to mammography during preoperative evaluation in patients with pathologic nipple discharge may detect an additional 26.3% of breast cancers [27], and that US is more useful in patients who have more clinical features of nipple discharge [19]. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that US BI-RADS itself reliably classifies breast lesions that are only detected by US. According to Bahl et al. [19], most lesions considered positive on US were intraductal masses or ectatic ducts with echogenic material or retroareolar masses without a definite intraductal component. However, there was no description of how the final US BI-RADS category was determined. In our study, we determined the final US category by assessing its detailed characteristics with BI-RADS lexicon, and all lesions were pathologically confirmed through US-guided biopsy, which gives strength to our results. Furthermore, we assessed whether the ductal wall shows irregularity among lesions that were associated with ducts. Though the number of masses showing irregular ductal wall changes was small, the positive predictive value of ductal wall irregularity was 16.7%, which is comparable to the malignancy rate of category 4. Thus, we suggest that irregular ductal wall changes at the breast US should be considered as category 4.

There are some limitations to our study. First, this is a retrospective, single-institution study. Although the number of malignancy cases in our study cohort was too low to have statistical power, it suggests several suspicious findings of breast US especially in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge. Second, breast lesions of US BI-RADS category 1 or 2 were excluded; as such, we cannot assess the reliability of US BI-RADS in these groups. Thus, further studies are required to fully assess the reliability of US BI-RADS in mammographically negative patients with nipple discharge. Third, we excluded the cases where the breast lesions were confirmed through surgery, rather than US-guided biopsy, to ascertain the exact correlation between BI-RADS final assessment and findings in the pathology report. This selection bias might have led us to miss any potential malignancy in these excluded cases. In conclusion, the BI-RADS lexicon and final assessment of breast US reliably detects and characterizes malignancy in mammographically negative patients with pathologic nipple discharge. Among US BI-RADS lexicons, the round or irregular shape, and not the parallel orientation of breast lesions, were associated with malignancy in mammographically negative patients with pathologic nipple discharge.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Leis HP., Jr Management of nipple discharge. World J Surg. 1989;13:736–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leis HP, Jr, Greene FL, Cammarata A, Hilfer SE. Nipple discharge: surgical significance. South Med J. 1988;81:20–26. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198801000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gülay H, Bora S, Kìlìçturgay S, Hamaloğlu E, Göksel HA. Management of nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:471–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrogh M, Park A, Elkin EB, King TA. Lessons learned from 416 cases of nipple discharge of the breast. Am J Surg. 2010;200:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rissanen T, Reinikainen H, Apaja-Sarkkinen M. Breast sonography in localizing the cause of nipple discharge: comparison with galactography in 52 patients. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1031–1039. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.8.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alcock C, Layer GT. Predicting occult malignancy in nipple discharge. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:646–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King TA, Carter KM, Bolton JS, Fuhrman GM. A simple approach to nipple discharge. Am Surg. 2000;66:960–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmons R, Adamovich T, Brennan M, Christos P, Schultz M, Eisen C, et al. Nonsurgical evaluation of pathologic nipple discharge. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:113–116. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawes LG, Bowen C, Venta LA, Morrow M. Ductography for nipple discharge: no replacement for ductal excision. Surgery. 1998;124:685–691. doi: 10.1067/msy.1998.91362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gioffrè Florio M, Manganaro T, Pollicino A, Scarfo P, Micali B. Surgical approach to nipple discharge: a ten-year experience. J Surg Oncol. 1999;71:235–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199908)71:4<235::aid-jso5>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murad TM, Contesso G, Mouriesse H. Nipple discharge from the breast. Ann Surg. 1982;195:259–264. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198203000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vargas HI, Romero L, Chlebowski RT. Management of bloody nipple discharge. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2002;3:157–161. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leconte I, Feger C, Galant C, Berlière M, Berg BV, D'Hoore W, et al. Mammography and subsequent whole-breast sonography of nonpalpable breast cancers: the importance of radiologic breast density. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1675–1679. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim EK, Ko KH, Oh KK, Kwak JY, You JK, Kim MJ, et al. Clinical application of the BI-RADS final assessment to breast sonography in conjunction with mammography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1209–1215. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA. ACR BI-RADS Atlas: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston: American College of Radiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim MJ, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Son EJ, Park BW, Kim SI, et al. Nonmalignant papillary lesions of the breast at US-guided directional vacuumassisted removal: a preliminary report. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:1774–1783. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim WH, Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, Yi A, Koo HR, et al. Intraductal mass on breast ultrasound: final outcomes and predictors of malignancy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:932–937. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ballesio L, Maggi C, Savelli S, Angeletti M, Rabuffi P, Manganaro L, et al. Adjunctive diagnostic value of ultrasonography evaluation in patients with suspected ductal breast disease. Radiol Med. 2007;112:354–365. doi: 10.1007/s11547-007-0146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahl M, Baker JA, Greenup RA, Ghate SV. Diagnostic value of ultrasound in female patients with nipple discharge. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:203–208. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Böhm-Vélez M, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:2151–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.18.2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D, Jong RA, Pisano ED, Barr RG, et al. Detection of breast cancer with addition of annual screening ultrasound or a single screening MRI to mammography in women with elevated breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2012;307:1394–1404. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakahara H, Namba K, Watanabe R, Furusawa H, Matsu T, Akiyama F, et al. A comparison of MR imaging, galactography and ultrasonography in patients with nipple discharge. Breast Cancer. 2003;10:320–329. doi: 10.1007/BF02967652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adepoju LJ, Chun J, El-Tamer M, Ditkoff BA, Schnabel F, Joseph KA. The value of clinical characteristics and breast-imaging studies in predicting a histopathologic diagnosis of cancer or high-risk lesion in patients with spontaneous nipple discharge. Am J Surg. 2005;190:644–646. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabioglu N, Hunt KK, Singletary SE, Stephens TW, Marcy S, Meric F, et al. Surgical decision making and factors determining a diagnosis of breast carcinoma in women presenting with nipple discharge. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:354–364. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01606-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercado CL. BI-RADS update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2014;52:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, Dennis MA, Parker SH, Sisney GA. Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Radiology. 1995;196:123–134. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.1.7784555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon H, Yoon JH, Kim EK, Moon HJ, Park BW, Kim MJ. Adding ultrasound to the evaluation of patients with pathologic nipple discharge to diagnose additional breast cancers: preliminary data. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:2099–2107. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]