Abstract

Introduction: People with severe mental illness have increased risk for premature mortality and thus a shorter life expectancy. Relative death rates are used to show the excess mortality among patients with mental health disorder but cannot be used for the comparisons by country, region and time. Methods: A population-based register study including all Swedish patients in adult psychiatry admitted to hospital with a main diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or unipolar mood disorder in 1987–2010 (614 035 person-years). Mortality rates adjusted for age, sex and period were calculated using direct standardization methods with the 2010 Swedish population as standard. Data on all residents aged 15 years or older were used as the comparison group. Results: Patients with severe mental health disorders had a 3-fold mortality compared to general population. All-cause mortality decreased by 9% for people with bipolar mood disorder and by 26–27% for people with schizophrenia or unipolar mood disorder, while the decline in the general population was 30%. Also mortality from diseases of the circulatory system declined less for people with severe mental disorder (−35% to − 42%) than for general population (−49%). The pattern was similar for other cardiovascular deaths excluding cerebrovascular deaths for which the rate declined among people with schizophrenia (−30%) and unipolar mood disorder (−41%), unlike for people with bipolar mood disorder (−3%). Conclusions: People with mental health disorder have still elevated mortality. The mortality declined faster for general population than for psychiatric patients. More detailed analysis is needed to reveal causes-of-death with largest possibilities for improvement.

Introduction

Reduced life expectancy and premature death are important aspects of severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder. This has been shown for a long time, also in different countries and settings (1–6). However, there is still uncertainty concerning whether the mortality gap between patients with severe mental illness and the population is being widened, bridged or remaining constant over time, in a period when the longevity of the population continues to increase, by 2.2 months per year in Sweden between 2000 and 2010 (7). Also, the long-term effects in terms of possible reduced mortality from treatment is far from evident, which is also the case of patient outcome measured by life expectancy and premature mortality differ by countries and setting.

Frequently, patient mortality is assessed in terms of mortality rate ratios, thus estimating the relative mortality among psychiatric patients compared to mortality in the general population (1). This is a valuable way to assess increased mortality risk, but it also has important drawbacks. Since the outcome of relative mortality studies will be affected not only by mortality in the patients but also by mortality in the population, results of relative mortality studies cannot be compared with studies from different areas due to the fact that effects of mortality among patients cannot be differentiated from effects of mortality among the whole population. Also, in time trend studies, effects of mortality in patients cannot be differentiated from effects of mortality in the general population.

Thus, to compare mortality outcome between different areas and over time, absolute mortality in terms of number of deaths is necessary. If assessed in population-based samples, this type of data will enable comparisons of mortality outcome for all causes of death and over time. Since diseases from the circulatory system cause a significant part of all deaths—35% of all deaths in Sweden in 2010 (8)—we studied them separately further divided to ischaemic heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases (myocardial infarctions separately) and other diseases from the circulatory system.

The aim of this study was to assess mortality in hospitalized patient with diagnosed schizophrenia, bipolar or unipolar mood disorder in Sweden. The trends were studied by time, for all-cause mortality and for specific causes of death, which then might be compared with data from similar analyses from other population-based samples.

Methods

Swedish national health registers were used to follow the entire population aged 15 years or older, approximately 175 million person years and identify all people admitted to hospital with a main diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar or unipolar mood disorder (614 035 person-years) from 1987 to 2010. Data about patients were retrieved from the National Patient Register (NPR).

The NPR, which is maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare, contains information on all hospital in-patient treatments in Sweden since 1987. For psychiatric in-patient care, the register has nationwide coverage dating back from 1973. For each hospitalization, the unique national personal identity code, date of admission and discharge, as well as the main and secondary diagnosis are registered in NPR.

All hospital diagnoses are classified according to the WHOs International Classification of Diseases (ICD) in Sweden. Since the diagnostic definitions of affective disorders were substantially changed in ICD-9 and ICD-10 as compared with ICD-8, only patients diagnosed with bipolar mood disorder according to ICD-9 or ICD-10 were included in the study. Bipolar mood disorder diagnoses recorded between 1987 and 1996 were identified using ICD-9 (296A, 296C, 296D, 296E, 298B). From 1997 and later, ICD-10 (F30–F31) was used to identify bipolar mood disorder diagnoses. Similarly, ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes were used to identify unipolar mood disorder diagnoses (ICD-9: 296B, 298A, 300E, 311X, ICD-10: F32, F33, F34) and schizophrenia (ICD-9: 295, ICD-10: F20, F25). All the studied disorders are diagnosed in adult psychiatry justifying the cut-off point of 15 years for patients and control population.

Information of causes of deaths was obtained by linking the NPR with the national Swedish Cause-of-Death Register using unique personal identification numbers given for all citizens and permanent residents.

The Cause-of-Death Register includes all individuals who were registered in Sweden at the time of death. The register provides information on date of death as well as main (underlying) and secondary causes of death based on death certificates. The used causes of death categories are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used for mortality analysis

| Diseases of the circulatory system | ICD-9 | ICD-10 |

|---|---|---|

| All deaths from diseases of the circulatory system | 401–459 | I10–I99 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 410–414 | I20–I25 |

| Acute myocardic infarction | 410 | I21–I22 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 430–438 | I60–I69 |

| Other deaths from diseases of the circulatory system | 401–409, 415–429, 439–459 | I10–I19, I26–I59, I70–I99 |

For studying time trends, the 24-year observation period was divided into six 4-year periods: 1987–90, 1991–94, 1995–98, 1999–2002, 2003–06 and 2007–10. Four-year periods were chosen to diminish random variation and to achieve cohorts with similar time from the first hospitalisation within each time period. In each time period, follow-up started on the date of first hospital admission. Each person was followed from the day of first hospital admission until death or the end of the 4-year period; therefore, a person could be counted in more than one time period if readmitted during a different period. The change by time was calculated by using the decline in mortality between the first (1987–90) and the last time period (2007–10).

Statistical analyses

Person years at risk and number of cause-specific deaths for both patients and the general population were determined. Person time was stratified by sex, calendar year and 5-year age categories, and adjusted mortality rates were calculated using direct standardization methods with the Swedish population in 2010 as standard. Confidence intervals for standardized rates were estimated using methods based on the gamma distribution (8). Analyses were carried out using statistical software SAS (version 9.2). All models were adjusted for or stratified by sex, attained age and years of follow-up.

Results

Basic information on the study groups is given in Table 2. The mean and median age of patients decreased for patients with bipolar and unipolar mood disorder but increased for patients with schizophrenia. In 2007–10, both the mean and median ages were similar for all three study groups: 47–48 years. In total, 55% of patients with schizophrenia were males, while there were more women in patients with bipolar mood disorder (61%) and unipolar mood disorder (59%).

Table 2.

Number of cases by sex, mean and median age (in years) and time of follow-up (in years) for each time period and psychiatric diagnosis

| Mental disorder | Year | Mean age | Median age | N | Men | Women | Mean follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 1987–90 | 46.3 | 42 | 15 744 | 8877 | 6867 | 2.36 |

| 1991–94 | 46.1 | 43 | 15 096 | 8501 | 6595 | 2.41 | |

| 1995–98 | 45.4 | 43 | 13 774 | 7672 | 6102 | 2.39 | |

| 1999–2002 | 45.5 | 44 | 11 880 | 6446 | 5434 | 2.39 | |

| 2003–06 | 46.5 | 46 | 11 477 | 6231 | 5246 | 2.28 | |

| 2007–10 | 47.4 | 47 | 10 940 | 6004 | 4936 | 2.33 | |

| Bipolar mood | 1987–90 | 50.9 | 50 | 6564 | 2604 | 3960 | 2.28 |

| disorder | 1991–94 | 51.5 | 50 | 6307 | 2569 | 3738 | 2.25 |

| 1995–98 | 51.8 | 51 | 6257 | 2501 | 3756 | 2.15 | |

| 1999–2002 | 50.7 | 51 | 6245 | 2597 | 3648 | 2.21 | |

| 2003–06 | 50.2 | 50 | 7596 | 2989 | 4607 | 2.05 | |

| 2007–10 | 47.3 | 47 | 9995 | 3896 | 6099 | 2.08 | |

| Unipolar mood | 1987–90 | 56.5 | 59 | 25 495 | 8803 | 16 692 | 2.09 |

| disorder | 1991–94 | 57.3 | 59 | 25 141 | 9063 | 16 078 | 1.92 |

| 1995–98 | 55.4 | 56 | 28 503 | 10 802 | 17 701 | 1.97 | |

| 1999–2002 | 52.2 | 52 | 28 725 | 10 914 | 17 811 | 1.99 | |

| 2003–06 | 49.9 | 50 | 29 430 | 11 633 | 17 797 | 1.94 | |

| 2007–10 | 48.1 | 48 | 31 396 | 12 896 | 18 500 | 2.00 |

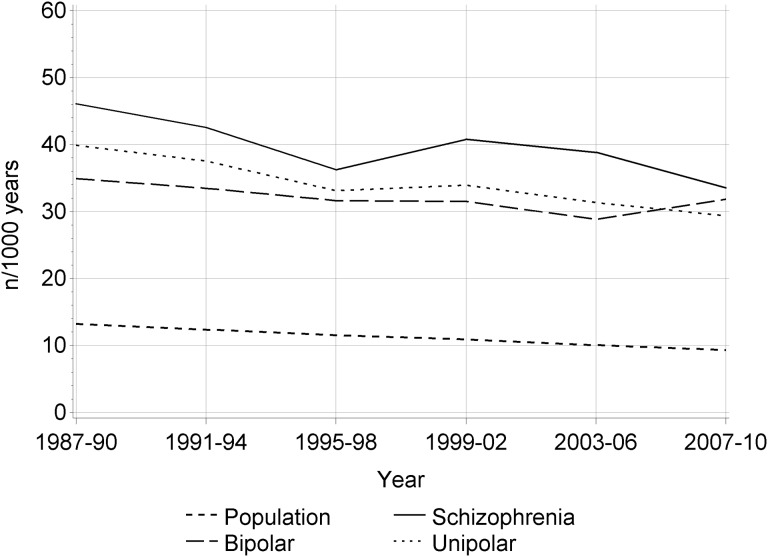

The age- and sex-standardised all-cause mortality declined in all patient groups during the study period (Fig. 1), most for patients with schizophrenia (−27%) and unipolar mood disorder (−26%), less for patients with bipolar mood disorder (−9%). The decline was, however, more significant for general population (−30%).

Figure 1.

Time trends in all-cause mortality among persons with schizophrenia, bipolar mood disorder, unipolar mood disorder and the general population in Sweden 1987–2010

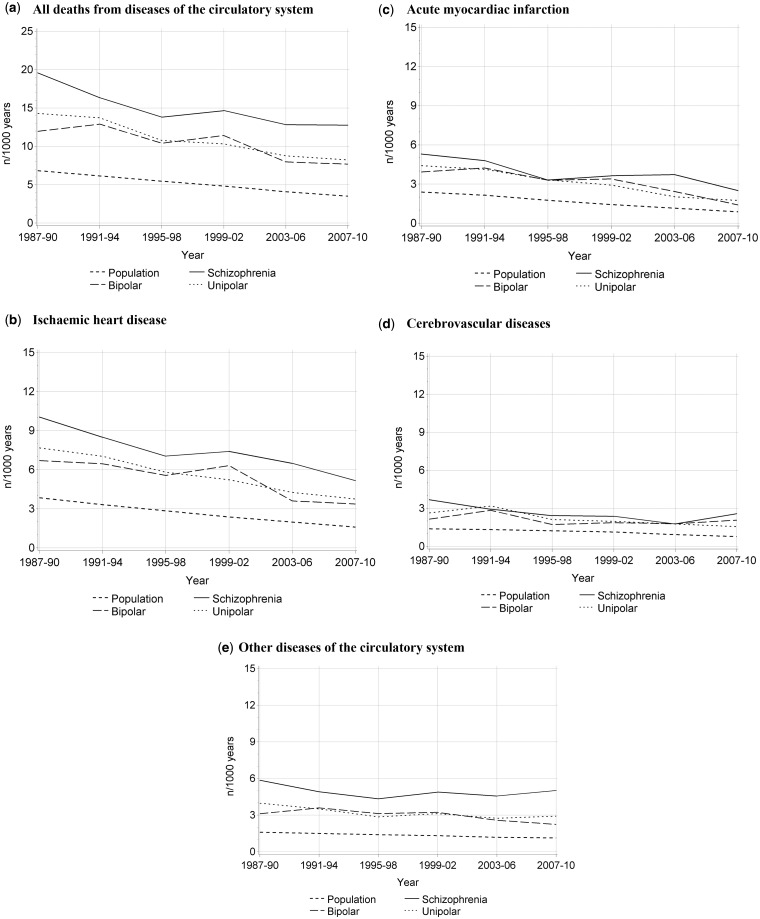

For all deaths from diseases of the circulatory system (Fig. 2), the decline was between −35% and −42% for the three patient groups, but −49% for general population. Similar pattern was observed for ischaemic heart diseases (from −49% to −51% for patient groups and −59% for general population), acute myocardial infarction (from −53% to −64% for patient groups and −64% for general population) and other diseases of the circulatory system (from −14% to −28% for patient groups and −29% for general population). The only exception was cerebrovascular diseases, for which the decline was substantial for people with schizophrenia (−30%) and unipolar mood disorder (−40%) as well as for general population (−44%) but only −3% for people with bipolar mood disorder.

Figure 2.

Time trends in mortality from cardiovascular diseases among persons with schizophrenia, bipolar mood disorder, unipolar mood disorder and the general population in Sweden 1987–2010

The excess all-cause mortality, as calculated by rate ratios, was more elevated for people with schizophrenia (variation between 3.1 and 3.9 during the study period) than for people with bipolar mood disorder (2.6–3.4) or with unipolar mood disorder (2.9–3.2).

For all deaths from diseases of the circulatory system, the excess mortality increased during the study period for all three patient groups, more for people with schizophrenia (from 2.9 to 3.6) than for people with unipolar mood disorder (from 2.1 to 2.3) or with bipolar mood disorder (from 1.7 to 2.0).

For the subgroup analyses, the trends varied more. For people with schizophrenia, the rate ratios increased for coronary heart disease, acute myocardial infarction and other cardiovascular diseases but decreased for cerebrovascular diseases. For people with bipolar mood disorder, the rate ratio increased for coronary heart disease but remained unchanged in other disease groups. For people with unipolar mood disorder, the rate ratios decreased for cerebrovascular diseases, increased for coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction and remain unchanged for other cardiovascular diseases.

Discussion

Patients with severe mental health disorders had a 3-fold mortality compared to general population, and there were no major change in the relative excess mortality during the study period, in spite of the declining mortality rates among people with mental disorder. The decline was higher for people with schizophrenia or unipolar mood disorder compared to people with bipolar mood disorder. The pattern was similar for cardiovascular deaths excluding cerebrovascular deaths for which the rate declined substantially less for people with bipolar mood disorder than the other study groups.

The Swedish NPR and Cause of Death Register include all residents in the country and are considered unique, comprehensive and highly credible. Currently, more than 99% of all somatic and psychiatric hospital discharges are recorded in the NPR (10). Swedish hospitals and government agencies are obliged by law to enter medical information in the NPR (10). All diagnoses in the NPR and the Cause-of-Death Register were given by the physician treating the patient using internationally accepted standard classification (ICDs). Being register based, this study used information about clinical diagnoses from hospital admissions in Sweden, but the categorisation of patient groups was based on the most recent diagnoses given at the discharge. Since hospital admission diagnoses are not recorded in the NPR, we could not analyse the differences between diagnoses at admission and discharge. The diagnoses given at discharge are, however, more reliable than at admission (11).

During the study period, the ICD diagnostic definitions were specific for selected mental disorders. A validation of the Swedish clinical bipolar mood disorder diagnoses given in hospital has shown high validity, sufficient for epidemiological studies (12). One limitation of this study was that it was based on in-patient diagnoses, which may have generated a selective bias towards severely ill patients. However, most individuals with schizophrenia and most with severe stages of bipolar and unipolar mood disorder are admitted to hospital in Sweden. Since medical care, including hospital care and prescribed medication, is heavily subsidised in Sweden (13), there is no bias by costs for hospital care leading to differences in health-seeking behaviour.

In a previous study, we have shown that the number and frequency of hospital admissions due to bipolar mood disorder remained relatively unchanged during recent years, while the overall number of psychiatric admissions was drastically reduced (14). We did not have access to medical records or information on medical treatment. We also lack information on other important factors affecting health, such as measures of socio-economic status and health behaviour, which is the main limitation of our study.

In terms of the validity of the data on causes of death, in CVD deaths we found a slightly higher autopsy rate (28%) among patients with bipolar mood disorder than in the general population (22%) (15). It is unlikely that these small differences affected the outcome of the study. An advantage with this study is the analysis of specific causes of death.

For clinical practice, the findings from this study implicate that outcome in schizophrenia, bipolar and unipolar mood disorder, as measured with mortality, improved during the study period in Sweden. However, the mortality gap between people with those diagnoses and the general population remained basically the same. This indicates that these psychiatric patients have benefited from improved treatment for cardiovascular diseases and other somatic conditions. Although the difference with the population has not decreased, implicating the need for special effort to further target cardiovascular diseases and other somatic conditions to improve longevity in this population. So far national public health goals of reducing the mortality gap between psychiatric patients and the general population have not been fulfilled, which calls for new clinical approaches and increased funding in this area to reach the long-term goal of health equality.

In conclusion, our study shows mortality trends in the major psychiatric disorders. Our data analysis methods can be used to investigate mortality in patient and other population groups, as well other patient outcomes in addition to mortality. It further allows comparisons of mortality rates by period, region/country and causes of death, unlike the more frequently used mortality rate ratios. This is a major improvement towards the possibility to make patient data comparable between countries and regions unaffected by the underlying population data.

Acknowledgements

The results were presented at 8th European Public Health Conference in Milan, Italy, 14–17 October 2015.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant (no. 2008-0885) from the Swedish Council for Social and Working Life Research and a project grant (no. 20 120 263) from Stockholm County Council. The sponsors had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of the research.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points

People with severe mental illness have increased risk for premature mortality and thus a shorter life expectancy.

Instead of using relative death rates, we calculated mortality rates for all-cause mortality and for specific causes of death, which can be used to compare mortality by time, region, population group and country.

People with mental health disorder have still elevated mortality, and the mortality declined faster for general population than for psychiatric patients.

More detailed analysis is needed to reveal the causes-of-death with largest possibilities for improvement.

References

- 1.Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, et al. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westman J, Gissler M, Wahlbeck K. Successful deinstitutionalisation of mental health care: increased life expectancy among people with mental disorders. Eur J Public Health 2012; 22: 604–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLoS One 2013; 8:e55176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One 2013;8:e67133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gissler M, Munk Laursen T, Ösby U, et al. Patterns in mortality among people with severe mental disorders across birth cohorts: a register-based study of Denmark and Finland in 1982-2006. BMC Public Health 2013; 13:834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westman J, Wahlbeck K, Munk Laursen T, et al. Mortality and life expectancy of people with alcohol use disorder in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2015; 131:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Health for All—Statistical Database. Geneva: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe; Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/data-and-evidence/databases/european-health-for-all-database-hfa-db (9 July 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fay M. Confidence intervals for directly standardized rates: a method based on the gamma distribution. Stats Med 1997;16:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prieto ML, Cuéllar-Barboza AB, Bobo WV, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:342–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponizovsky AM, Grinshpoon A, Pugachev I, et al. Changes in stability of first-admission psychiatric diagnoses over 14 years, based on cross-sectional data at three time points. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2006; 43:34–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sellgren C, Landén M, Lichtenstein P, et al. Validity of bipolar disorder hospital discharge diagnoses: file review and multiple register linkage in Sweden. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011; 124:447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NOMESCO. Health Statistics in the Nordic Countries 2014. Copenhagen: Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee, 2014: 102 Available at: http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:774213/FULLTEXT01.pdf (31 December 2015, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osby U, Tiainen A, Backlund L, et al. Psychiatric admissions and hospitalization costs in bipolar disorder in Sweden. J Affect Disord 2009; 115:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westman J, Hällgren J, Wahlbeck K, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in bipolar disorder: a population-based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ Open 2013;18;3. pii: e002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]