Summary

Recently, massive functional data have been widely collected over space across a set of grid points in various imaging studies. It is interesting to correlate functional data with various clinical variables, such as age and gender, in order to address scientific questions of interest. The aim of this paper is to develop a single-index varying coefficient (SIVC) model for establishing a varying association between functional responses (e.g., image) and a set of covariates. It enjoys several unique features of both varying-coefficient and single-index models. An estimation procedure is developed to estimate varying coefficient functions, the index function, and the covariance function of individual functions. The optimal integration of information across different grid points are systematically delineated and the asymptotic properties (e.g., consistency and convergence rate) of all estimators are examined. Simulation studies are conducted to assess the finite-sample performance of the proposed estimation procedure. Furthermore, our real data analysis of a white matter tract dataset obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study confirms the advantage and accuracy of SIVC model over the popular varying coefficient model.

Keywords: Functional response, Image analysis, Single index, Uniform convergence, Varying coefficient

1. Introduction

As a semiparametric regression modelling strategy, single-index modelling has attracted much attention in the literature due to its balance between exibility and fidelity. A classical single-index model is often written as

| (1) |

where Y is a response variable, g(·) is an unknown index function, X is a covariate vector, and ε is an error term such that E(ε|X) = 0. See Horowitz (2009) for a comprehensive review of various estimation methods for single-index models and references therein (Li, 1991; Cook and Weisberg, 1991; Zhu et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2002; Xia, 2007; Ma and Zhu, 2012, 2013). For instance, dimension reduction approaches, such as likelihood-based methods (Cook and Forzani, 2009), are also commonly used for estimation. However, the existing literature primarily considers univariate response observed from cross-sectional studies.

This paper is motivated by the analysis of a real diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) data set with n = 213 subjects collected from NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study. For each subject, we calculated a Fractional Anisotropy (FA) curve at all the 83 grid points along the skeleton of the midsagittal corpus callosum as shown in Figure 1. We are interested in establishing an association between FA curves and several covariates of interest, such as age and gender. To establish such association, standard grid-wise methods are to fit a linear model to functional observations at each grid point as responses and clinical variables, such as age and gender, as covariates, and to generate a statistical map of test statistics or p-values across all grid points (Lazar, 2008;Worsley et al., 2004). These grid-wise methods have several major limitations. First, compared with model (1), the classical linear model used in the neuroimaging literature is often restrictive, since it assumes that the index function g(·) is an identity function. When g(·) is truly nonlinear, directly fitting a classical linear model can cause substantial efficiency loss and reduce prediction accuracy. Second, since the grid-wise methods treat all grid points as independent units, they ignore two key functional features of functional data including spatial smoothness and spatial correlation.

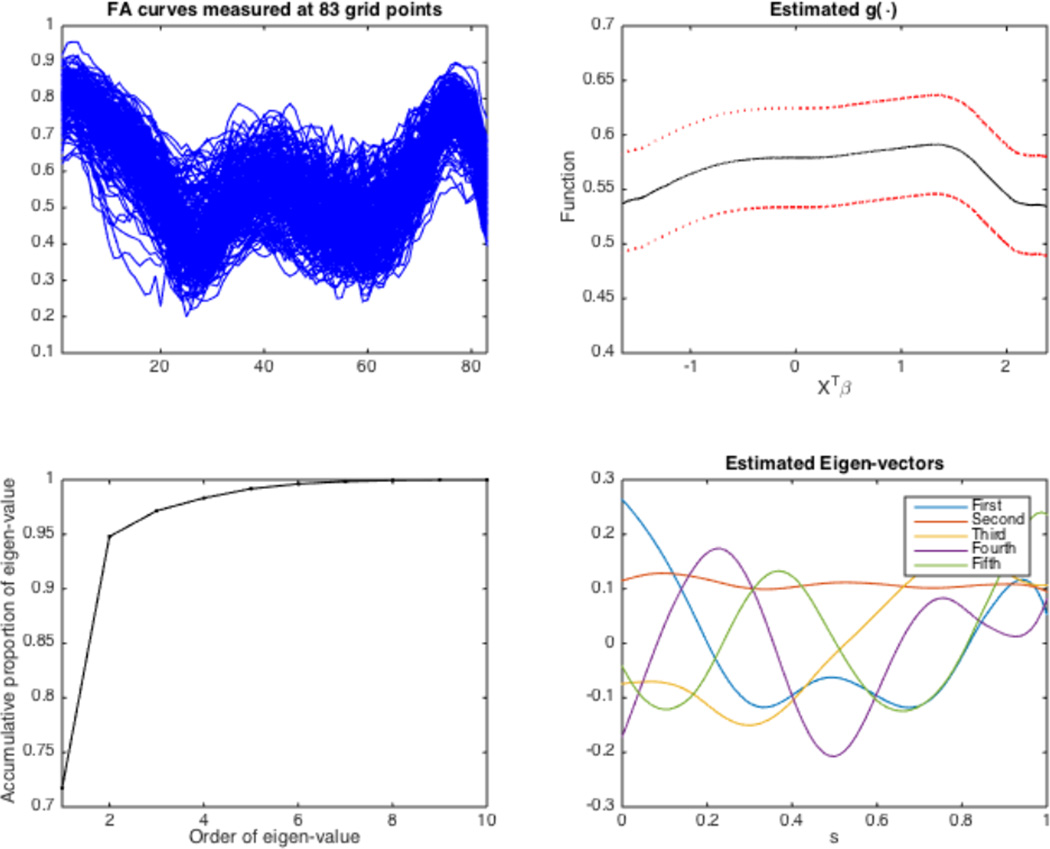

Figure 1.

ADNI data analysis: raw FA curves measured at 83 grid points (upper-left panel), the estimated index function with the broken red lines representing 95% simultaneous Confidence bands (upper-right panel), the estimated accumulative proportion of estimated eigenvalues (lower-left panel) and estimated eigenfunctions (lower-right panel) corresponding to the five largest eigenvalues.

Some advanced methods have been developed to specifically incorporate these features by using function-on-scalar regression under the functional data analysis (FDA) framework (Zhu et al., 2012; Ramsay and Silverman, 2005; Staicu et al., 2010; Zhang and Chen, 2007; Reiss et al., 2010). Some important estimation methods for FDA include adaptive smoothing methods (Polzehl and Spokoiny, 2006; Li et al., 2011), the integration of FDA and adaptive smoothing methods (Zhu et al., 2014), and spatial priors within the Bayesian framework (Gossl et al., 2001; Penny et al., 2005; Bowman et al., 2008; Smith and Fahrmeir, 2007; Yue et al., 2010; Miranda et al., 2013), among others. See Morris (2015) and Wang et al. (2015) for a comprehensive review of various FDA models for functional responses. However, to the best of our knowledge, none of the references cited above address the two functional features and estimate the nonparametric index function simultaneously.

The aim of this paper is to develop a single-index varying coefficient (SIVC) model to establish a varying association between functional responses and a set of covariates. Specifically, we extend the single-index model (1) to SIVC for functional responses as follows:

| (2) |

where {Y (s) : s ∈ 𝒮} is an observed stochastic process on a compact set 𝒮 and ε(s) is a random function characterizing the within-subject correlations and measurement errors at different grid points such that E{ε(s)|X} = 0 for all s ∈ 𝒮. The β(s) allows us to characterize the dynamic association between covariate X and functional response, whereas g(·) is a nonparametric function, while being fixed across all s ∈ 𝒮. Model (2) differs from the functional single index model in Jiang and Wang (2011), in which g(·) varies across s, but β(s) is assumed to be stationary. When g(x) = x, model (2) reduces to standard voxel-wise methods based on linear model and the most popular FDA model considered in (Zhang and Chen, 2007; Ramsay and Silverman, 2005; Zhu et al., 2014). For notational simplicity, we set 𝒮 = [0, 1]. The results can be readily extended to more general cases with compact subset 𝒮 of the Euclidean space.

Compared with the existing literature, we make several unique contributions. (i) We develop a new estimation procedure to estimate various parametric and non-parametric components of SIVC. (ii) Theoretically, we delineate the integration of information across all grid points by using an optimal weight function and then establish the asymptotic properties of various estimates for SIVC. (iii) Our analysis of the ADNI data confirms the advantage and accuracy of SIVC model over the popular varying coefficient model (Zhang and Chen, 2007; Ramsay and Silverman, 2005; Zhu et al., 2014).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the estimation procedure to estimate varying coefficient functions, index function, and the covariance function of individual functions. Section 3 systematically investigates the asymptotic properties of all estimators. A simulation study and a real data analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study are presented in Section 4 to demonstrate the finite sample performance of SIVC. Section 5 concludes with some discussions.

2. Methods

2.1 Single-index Varying Coefficient Model

We formally introduce the single-index varying coefficient model as follows. Consider {({Yi(s) : s ∈ 𝒮}, Xi) : i = 1, …, n} from n independent subjects, where 𝒮 is a compact set that characterizes the range of all possible grid points. Our single-index varying coefficient (SIVC) model is written as

| (3) |

where Xi is a p × 1 covariate vector, β(s) = (β1(s), ⋯, βp(s))T is a p × 1 vector of varying coefficient functions, g(·) is an unknown index function, ηi(s) characterizes individual curve variations, and εi(s) is a random function of measurement errors. The process {ηi(s) : s ∈ 𝒮} is assumed to be a Gaussian process with zero mean and a covariance function Ση(s, t) = Cov{η(s), η(t)}. The error terms εi(s) follow a Gaussian process with zero mean and a diagonal covariance function Cov{ε(s), ε(t)}. That is, εi(s) and εi(t) are assumed to be independent for s ≠ t, and Cov{ε(s), ε(t)} takes the form of , where 1(·) is an indicator function. Moreover, Yi(s) are usually measured at the same set of locations for all subjects and exhibit both the within-curve and between-curve dependence structures. Thus, without loss of generality, it is assumed that Yi(s) are observed on M grid points 𝒮M = {sm : 0 = s1 ≤ ⋯ ≤ sM = 1} for all subjects.

For single index model, β(s) is not identifiable since g(XT β(s)) and g(β0(s) + δXT β(s)) are not distinguishable, where δ is any nonzero scalar. A simple solution in the literature (Zhu et al., 2010; Xia et al., 2002) is to impose some constraints on β0(s) and β(s), such as β0(s) = 0 and β(s)T β(s) = 1. Therefore, throughout the paper, it is assumed that X does not contain the intercept, β(s)T β(s) = 1 holds for all s ∈ 𝒮 and the first entry of β(s) is positive at each s.

2.2 Estimation Procedure

Our estimation procedure consists of three steps for estimating the varying coefficient functions β(·), the index function g(·), and the covariance function Ση(s, s′).

Step I. Estimating varying coefficient β(s)

We first consider the estimation of β(sm) at each given grid point sm. Model (3) reduces to a classical single-index model given by

| (4) |

where such that and . The likelihood function of a random observation (X, Y (sm)) in model (4) is given by

where f1 is the probability density function of X, and f2 is the conditional probability density function of ε*(sm) = Y (sm) − g(XT β(sm)) given X.

Based on the Gaussian assumption of , f2(·) is the normal density with mean zero and variance . Thus, the score function for β(sm), denoted as S(β(sm)), is given by

| (5) |

where ġ(t) = dg(t)/dt. Following the reasoning in Ma and Zhu (2014), (I) and (II) belong to the tangent space of model (4) with respect to β(sm), denoted by Λg(sm), and its orthogonal component, denoted by Λg(sm)⊥, respectively. For any s ∈ 𝒮, Λg(s) and Λg(s)⊥ are, respectively, given by

Therefore, the efficient score function for β(sm) is given by

| (6) |

To calculate an efficient estimator of β(sm), denoted as β̃(sm), we can solve

| (7) |

Since Seff depends on three unknown quantities E{X|XT β(sm)}, g(XT β(sm)) and ġ(XT β (sm)), we construct their nonparametric estimators as follows (Ma and Zhu, 2013). The Nadaraya-Watson kernel estimator of E{X|XT β(sm)} is given by

| (8) |

where Kh(·) = K(·/h)/h is a kernel function and hx is a given bandwidth. We can calculate the estimates of g(XT β(sm)) and ġ(XT β(sm)) at XT β(sm) = XT β0(sm), denoted by ĝ(XT β0(sm)) and ġ̂(XT β0(sm)), by minimizing

| (9) |

As suggested by Ma and Zhu (2014), we set hx = cn−1/3 and hy = cn−1/5, where c is the average standard deviation of X. By plugging Ê{X|XT β(sm)}, ĝ(XT β0(sm)) and ġ̂(XT β0(sm)) into (7), we get an estimate of Seff(β(sm); Xi, Yi(sm)), denoted by Ŝeff(β(sm); Xi, Yi(sm)) and then calculate β̃(sm) by solving

| (10) |

To estimate β(s) at any s ∈ 𝒮, we need to construct a weighted estimating equation to borrow information across all grid points by using the functional features of imaging data (Wang et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2012; Polzehl and Spokoiny, 2006; Li et al., 2011). Specifically, the weighted estimating equation is given by

| (11) |

where w(sm, s) is a weight function of (sm, s) and may depend a few parameters, such as bandwidth. Then, we calculate an estimate of β(s), denoted by β̂(s), by solving the following equation:

| (12) |

A critical issue in (12) is how to select an optimal weight function w(sm, s). Theoretically, one may choose w(sm, s) by minimizing the mean integrated squares error (MISE) of β̂(·) for all s ∈ 𝒮, but it can be challenging due to the lack of precise information about β(s). Without such information, a simple solution is to set w(sm, s) = K((sm − s)/h)/h and then select the bandwidth h by using some criteria, such as cross-validation method, based on MISE. Furthermore, when β(s) is a piecewise constant function, we will show how to optimally select w(sm, s) in Section 3.

Step II. Estimating the unknown index function g(·)

We use the local linear technique to estimate g(XT β(s)). We define and

where Z⊗2 = ZZT for any vector Z. By replacing β(sm) by β̂(sm), we get Ẑi,m(s) and Σ̂(XT β(s), h1). Denote G(XT β (s)) = (g(XT β (s)), h1ġ(XT β (s)))T, we directly minimize a weighted least square function given by

| (13) |

Thus, we have ĝ(XT β(s)) = [1 0]Ĝ (XT β (s)), where Ĝ (XT β(s)) is given by

The bandwidth h1 is chosen by using the cross-validation method.

Step III. Estimating the covariance function Ση(s, t)

Let di(s) = (ηi(s), h2η̇i(s))T, Wm,s = (1, (sm−s)/h2)T, and . We minimize the following function

| (14) |

to obtain

Then, η(s) can be estimated by

| (15) |

where , which is the empirical equivalent kernel. The bandwidth h2 is also chosen by using the cross-validation method.

We consider the spectral decomposition of Ση(s, t) and its approximation. Suppose Ση(s, t) is continuous on 𝒮2, then according to Mercer’s theorem, it can be decomposed as

where λ1 ≥ λ2 ≥ ⋯ ≥ 0 are ordered eigenvalues and ψk(s) are the corresponding orthonormal eigenfunctions. Furthermore, the eigenfunctions form an orthonormal system on the space of square-intergrable function on 𝒮, and ηi(s) admits the Karhunen-Loeve expansion as , where is the k-th functional principal component scores of the i-th subject. For a fixed i, ξik are uncorrelated random variables with mean zero and variance λk.

By following Rice and Silverman (1991), the covariance matrix Ση(s, t) and its spectral decomposition can be estimated by

| (16) |

where λ̂1 ≥ λ̂2 ≥ ⋯ ≥ 0 are estimated eigenvalues and ψ̂k(s) are the corresponding estimated eigenfunctions. Moreover, the k-th functional principal component scores can be computed by for i = 1, …, n.

2.3 Simultaneous Confidence Bands

Given a Confidence level α, we construct a simultaneous Confidence band for each βl(s) such that where and are the lower and upper limits of simultaneous Confidence band, respectively. Specifically, we set

| (17) |

where bias(β̂l(s)) is the bias of β̂l(s) at s ∈ 𝒮 and Cβl(α) is a scalar. By following the arguments in Zhu et al. (2012), we use the local polynomial technique to estimate bias(β̂l(s)) for each l and then approximate Cβl(α) by using the wild bootstrap as follows:

Step 1: We calculate for all i and m.

Step 2: For q = 1, …, Q, we independently generate { : i = 1, ⋯, n} from N(0, 1) and construct . Then, based on {Yi(sm)(q)}, we recalculate β̂(s)(q), and obtain a stochastic process Gβl(s)(q) = | β̂l(s)(q) − β̂l(s)(q)| for each l.

Step 3: For all q, we calculate the 1 − α empirical percentile of Gβl(s)(q), denoted by Cβl(s, α), at each s ∈ 𝒮. Finally, an estimate of Cβl(α) is sups |Cβl(s, α)|.

Similarly, for a given α, we construct a simultaneous Confidence band for g(·) as follows:

where 𝒰 is a compact set in R and ĝL,α(u) and ĝU,α(u) are the lower and upper limits of simultaneous Confidence band, respectively. Specifically, we set

| (18) |

Subsequently, we use the local polynomial technique to estimate bias(ĝ(u)) and then use the wild bootstrap to approximate Cg(α) as follows:

Step 1: We calculate for all i and m.

Step 2: For q = 1, …, Q, we independently generate { : i = 1, ⋯, n} from N(0, 1) and construct . Then, based on {Yi(sm)(q)}, we recalculate ĝ(·)(q), and obtain a stochastic process Gg(u)(q) = |ĝ(u) − ĝ(u)(q)|.

Step 3: For all ℓ, we calculate the 1 − α empirical percentile of Gg(u)(q) denoted by Cg(u, α) at every u ∈ 𝒰 and then approximate Cg(α) by using supu∈𝒰 |Cg(u, α)|.

3. Theoretical Results

3.1 Optimal weight Functions

We consider a challenging issue of optimally selecting the weight function w(sm, s) in order to gain efficiency, since ŜnM (β(s);w) for a given weight function w(·, ·) may not be an efficient estimating equation. Specifically, Λg(s) and Λg(s′) may interact with each other for s ≠ s′ by noting that

| (19) |

Therefore, Λg(s) and Λg(s′) are orthogonal with each other for s ≠ s′ if and only if Ση(s, s′) = 0 for s ≠ s′. It also holds for {Λg(s)⊥ : s ∈ 𝒮} due to Λg(s) ⊥ Λg(s)⊥.

First, we consider how to choose the weight function when β(s) = β0 does not vary across s ∈ 𝒮. With some calculations, we can show that the covariance matrix of can be approximated by

| (20) |

where w(s) = (w(s1, s), ⋯, w(sM, s))T and D(w(s)) is given by

| (21) |

We can obtain an optimal weight vector, denoted by w*, by minimizing Σ1(w(s)) such that w* = argminw(s)Σ1(w(s)). As shown in Theorem 1 (i) below, w* is associated with the eigenvalue-eigenvector pairs of , denoted by {(λm*,M, ψm*,M) : m = 1, …, M}, where Ση*,M = (Ση(sm, sm′)) and are two M × M matrices.

Second, we set ω(sm, s) as Kh(sm − s), which is a kernel function of (sm − s)/h, when β(s) may vary across s ∈ 𝒮. If h → 0, then it can be shown that the covariance matrix of can be approximated by Σ1(w(s)) in (20). We will show in Theorem 1 (ii) that the use of the kernel function can lead to substantial efficiency gain even under this general scenario.

Theorem 1

We have the following results.

- Suppose that β(s) = β0 does not vary across s ∈ 𝒮. The optimal w* is given by

where ‖·‖2 is the Euclidean norm of a vector, Σε*,M = Ση*,M+Λε*,M is an M×M matrix, and 1M is an M × 1 vector of ones. Thus, the optimal D(w) is given by and is independent of s. The can be written as(22) (23) Suppose that β(s) may vary across s ∈ 𝒮. Under Assumptions (C6) and (C7), if w(sm, s) = Kh(sm − s), h → 0, and Mh → ∞, then D(w(s)) can be approximated by Ση(s, s).

Theorem 1 has several interesting implications. If Ση(s, s′) = 0 for any s ≠ s′, then w* is proportional to . In this case, we can set for all m, and then the optimal weighted estimating equation is given by

Theorem 1 (i) also implies that in general cases, w(sm, s) is given by

where em is an M × 1 vector with the m-th element one and zero otherwise. For functional data, it is common to assume that λm*,M = 0 for all m > K, where K is a positive integer. Under some additional conditions, it can be shown that λm*,M and ψm*,M converge to the m–th eigenvalue and its corresponding eigenfunction of the covariance function Ση(s, s′)/{σε(s)σε(s′)}, respectively.

Another implication of Theorem 1 (i) is the lower bound of D(w*). Specifically, D(w*) is given by

| (24) |

which is greater than . In general, the presence of spatial correlation increases the covariance matrix of β̂(s). Such lower bound is achievable only when Ση(s, s′) = 0 holds for any s ≠ s′. Furthermore, such lower bound is asymptotically achievable when λ1*,M = op(1), since x/(1 + x) is a monotone function of x.

Theorem 1 (ii) implies that the use of w(sm, s) = Kh(sm − s) can lead to substantial efficiency gain if there are substantial measurement errors. Specifically, if w(sm) = em, then we consider information at the m–th grid point. In this case, we have , which can be much larger than Ση(sm, sm) when is much larger than Ση(sm, sm). The ratio of Σ1(e(sm)) over Σ1((Kh(sm−s))) is equal to . Therefore, the efficiency gain of using w(sm, s) = Kh(sm − s) can be substantial if the value of is large.

3.2 Asymptotic Properties

Second, we investigate the asymptotic properties of β̂(·), ĝ(XT β̂(s)) and Σ̂η(s, t) when we set w(sm, s) = Kh(sm − s). For any smooth function f(s) and g(s, t), define ḟ(s) = df(s)/ds, f̈(s) = d2 f(s)/ds2 and g(a,b)(s, t) = ∂a+bg(s, t)/∂sa∂tb, where a and b are any nonnegative integers. We state the following theorems regarding the weak convergence of {β̂(s) : s ∈ 𝒮} and ĝ(XT β̂(s)), whose detailed assumptions and proofs can be found in Web Appendix. Moreover, we also include additional asymptotic properties and their proofs in the same Web Appendix.

Theorem 2

Under Assumptions (C1)–(C11), as n, M → ∞, we have the following results.

converges weakly to a Gaussian process with mean zero and covariance function, which is the limiting function of , where An(·) and Bi(·) are defined in Web Appendix.

converges weakly to a Gaussian process with mean zero and covariance function Ση(s, t).

Theorem 2 ensures that we can make formal statistical inference on β(·) and g(·). Based on Theorem 2 (i) and (ii), we develop a wild bootstrap method to construct the Confidence bands of β̂(·) and ĝ(·) and include it in Section B of Web Appendix.

4. Numerical Studies

4.1 Simulation Results

We generated Y (sm) according to model (3) with ε(sm) ~ N(0, σ2 = 0.32) and Xi ~ N(0p, Σ), where Σ is a 4 × 4 matrix with elements ρ|j′−j| for j, j′ = 1, …, 4. Moreover, the varying coefficients βj(s) are, respectively, given by

and then they were scaled as β(s)/‖β(s)‖2. We set sm as M = 50 equidistant grid points in [0,1] with s1 = 0 and sM = 1. We set with , and . We consider two index functions including and .

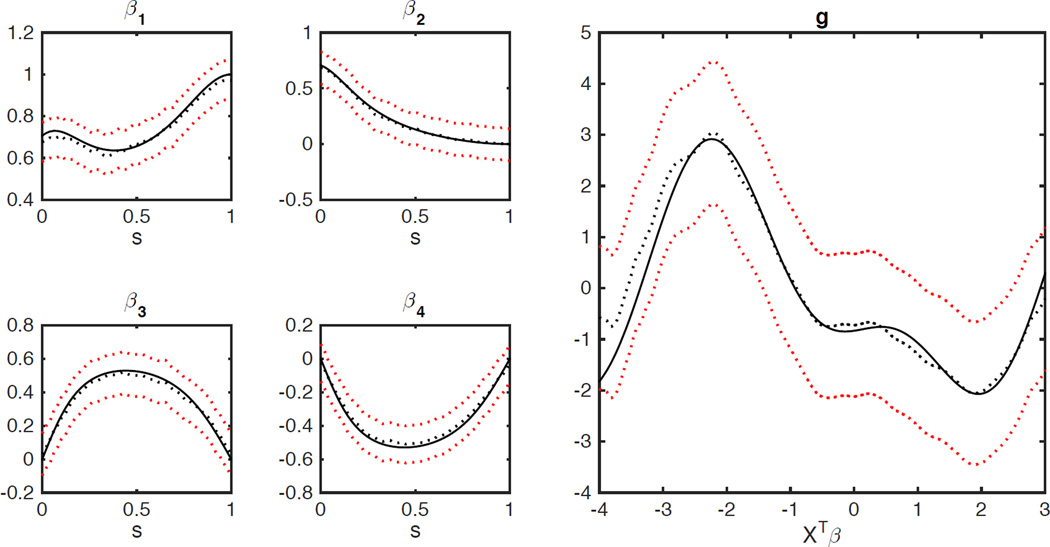

We conducted extensive simulation studies under different settings, but we only report some representative results for the sake of space. First, we set n = 40 and 200 and simulated data sets from model (3) for the first index function as described above. We fitted SIVC to each simulated data set and calculated all unknown quantities. Table 1 summarizes the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) of all parameter estimates and the mean integrated absolute error (MIAE) and mean integrated squared error (MISE) of all estimated functions based on 200 simulations. The results in Table 1 indicate satisfactory performance of our estimators since all MAE, MSE, MIAE and MISE values are quite small. Typical estimated functions with mean performance are displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 1 in Web Appendix. The estimated curves (broken lines) closely resemble the corresponding true functions (solid lines) in these figures. As expected, all the errors increase as sample size decreases. Moreover, Table 2 includes the coverage probabilities of the simultaneous Confidence bands of βl(s)s and g1(u) for n = 40 and 200 based on 500 simulations. These coverage probabilities get close to the specified Confidence level 95% as sample size increases, while the results for g(·) are slightly worse than those of βl(s).

Table 1.

Estimation results from 200 simulated data sets corresponding to the index function g1(XT β(s)) with n = 200 and 40. MAE is mean absolute error, RMSE is root mean square error, MIAE is mean integrated absolute error, and MISE is mean integrated square error

| n = 200 | n = 40 | ||||||

| Parameters | λ1 | λ2 | σ2 | λ1 | λ2 | σ2 | |

| MAE | 0.1551 | 0.0621 | 0.0202 | 0.1773 | 0.1026 | 0.0594 | |

| RMSE | 0.1724 | 0.0726 | 0.0267 | 0.2108 | 0.1212 | 0.0667 | |

| n = 200 | |||||||

| Functions | β1(s) | β2(s) | β3(s) | β4(s) | ψ1(s) | ψ2(s) | g(·) |

| MIAE | 0.0288 | 0.0440 | 0.0403 | 0.0119 | 0.0137 | 0.0138 | 0.1063 |

| MISE | 0.0042 | 0.0077 | 0.0093 | 0.0039 | 0.0033 | 0.0034 | 0.0412 |

| n = 40 | |||||||

| Functions | β1(s) | β2(s) | β3(s) | β4(s) | ψ1(s) | ψ2(s) | g(·) |

| MIAE | 0.0488 | 0.0751 | 0.0686 | 0.0597 | 0.0291 | 0.0299 | 0.2536 |

| MISE | 0.0121 | 0.0249 | 0.0251 | 0.0241 | 0.0061 | 0.0060 | 0.1530 |

Figure 2.

Simulation results for model (3) with the first index function and n = 200: the true and estimated varying coefficient functions and the true and estimated index functions. In each panel, the solid line represents the true function, the broken line represents the estimated function, and the red broken lines are the corresponding 95% simultaneous Confidence bands.

Table 2.

Coverage probabilities of simultaneous confidence bands for n = 40 and 200 based on 500 simulated data sets. The confidence level is 95%.

| n | β1(s) | β2(s) | β3(s) | β4(s) | g(·) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 0.936 | 0.932 | 0.944 | 0.934 | 0.924 |

| 200 | 0.946 | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.946 | 0.942 |

Second, we illustrate the superiority of SIVC over multivariate varying coefficient model (MVCM) in Zhu et al. (2012) in terms of prediction accuracy. We set n = 200 and then simulated data sets from model (3) for both and . For each simulated dataset, we randomly split it into a training set and a test set according to proportions π and 1 − π, respectively. We used the training set to estimate all unknown parameters, and then predicted the responses in the test set. Finally, we calculated the prediction error for each simulated dataset. We consider three values of π including 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7. For each case, we repeated 200 times. Table 3 reports the MAE and RMSE of prediction errors for SIVC and MVCM. For the index function , SIVC significantly outperforms MVCM with smaller MAE and RMSE. Even for , SIVC is slightly better than MVCM. It may indicate that SIVC is a useful tool for modeling functional data.

Table 3.

Prediction results corresponding to both index functions g1(XT β(s)) and g2(XT β(s)) with n = 200. MAE is mean absolute error and RMSE is root mean square error.

| g1(XT β(s)) | g2(XT β(s)) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | |

| π = 0.3 | ||||

| SIVC | 1.013 (0.040) | 1.282 (0.052) | 0.987 (0.042) | 1.248 (0.053) |

| MVCM | 1.215 (0.040) | 1.530 (0.053) | 1.031 (0.045) | 1.299 (0.060) |

| π = 0.5 | ||||

| SIVC | 1.002 (0.049) | 1.267 (0.063) | 0.978 (0.048) | 1.236 (0.060) |

| MVCM | 1.207 (0.048) | 1.520 (0.065) | 1.014 (0.050) | 1.278 (0.062) |

| π = 0.7 | ||||

| SIVC | 0.977 (0.068) | 1.236 (0.081) | 0.966 (0.065) | 1.222 (0.082) |

| MVCM | 1.188 (0.063) | 1.494 (0.082) | 1.006 (0.068) | 1.268 (0.084) |

4.2 Real Data Analysis

We applied model (3) to the DWI data set described in Section 1. One goal of NIH ADNI is to test whether genetic, structural and functional neuroimaging, and clinical data can be integrated to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). We downloaded the structural brain MRI data and corresponding clinical and genetic data from baseline and follow-up from the ADNI publicly available database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/).

The DWI data were processed by using a FSL TBSS pipeline (Smith et al., 2006) to register DTIs from multiple subjects to create a mean image and a mean skeleton. We used FMRIB software library to compute maps of fractional anisotropy (FA) for all subjects from the DTI after eddy current correction and automatic brain extraction. Then, we fed FA maps into the TBSS tool, which is also part of FSL. In the TBSS analysis, we aligned the FA data of all the subjects into a common space by using non-linear registration and created and thinned the mean FA image to obtain a mean FA skeleton, which represents the centers of all white matter tracts common to the group. Subsequently, we projected each subject’s aligned FA data onto this skeleton. Finally, we obtained the FA template curve measured at all the 83 grid points along the skeleton of the midsagittal corpus callosum as shown in Figure 2 in Appendix for all the subjects.

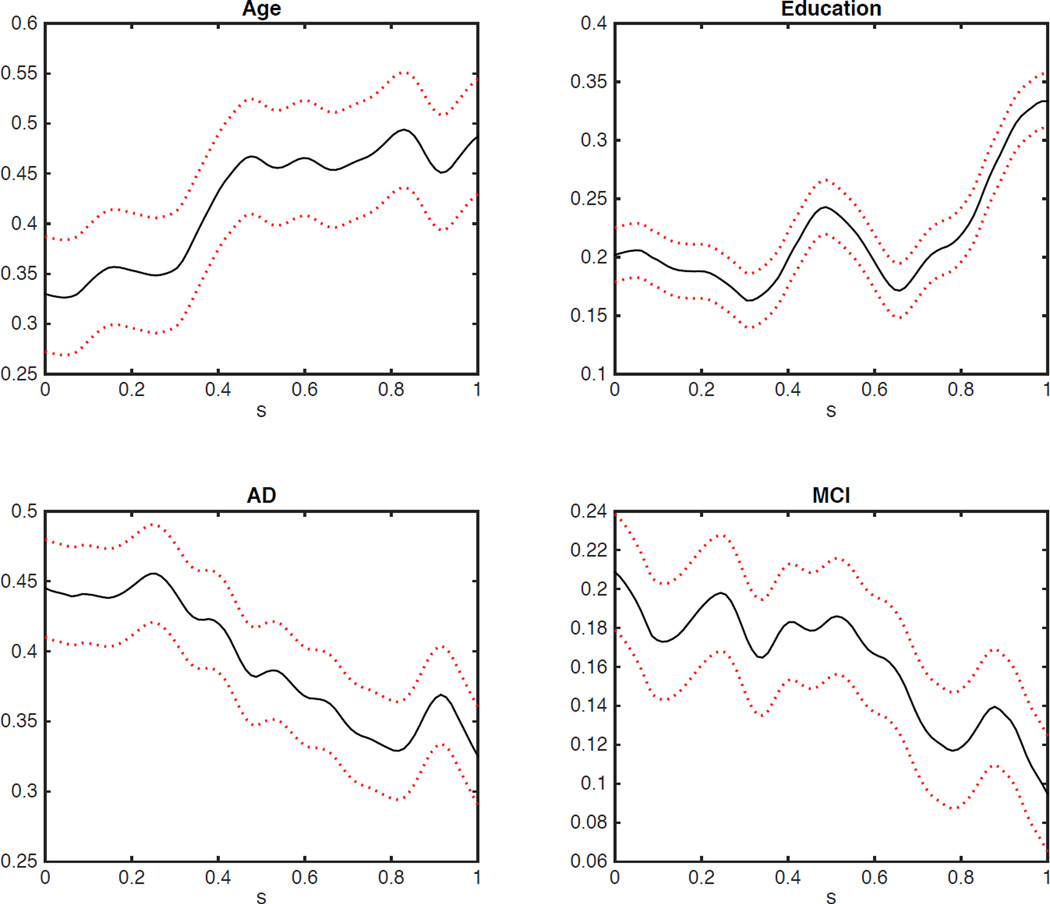

We are interested in establishing an association between FA and seven covariates including the gender variable (123 male and 91 female, coded by a dummy variable indicating for male), the age of the subject (years, ranges from 48.4 (years) to 90.4, mean 73.20), an indicator for handiness (193 right-hand and 20 left-hand, coded by a dummy variable indicating for left-hand), the education level (years, ranges from 9 to 20 (years), mean 15.91), an indicator for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) status (19.6%), an indicator for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) status (55.1%) and Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) of ADNI. We standardized all variables to have mean zero and variance one. We fitted model (3) and applied the estimation procedure in Section 2 to the data set. Figure 3 presents the estimated varying coefficients corresponding to age, education, AD status, and MCI status. The results reveal that MMSE, age, education, MCI, and AD are the most important factors. Moreover, gender and handiness have little effects on FA.

Figure 3.

ADNI data analysis: the four estimated varying coefficients for Age, Education, AD, and MCI. The black solid lines are estimated coefficients and the red broken lines are their corresponding 95% simultaneous Confidence bands.

We estimated the single index function g(·) and the covariance function Ση(s, s′) and its associated eigenvalues and eigenfunctions. See Figure 1 for details. The single index function shows a pattern with small values at the left and right ending points of the range and two modes in the middle of the range. The top five non-zero eigenvalues of Σ̂η(s, s′) are 0.8628, 0.2771, 0.0284, 0.0142, and 0.0102, respectively. The first two eigenvalues account for 94.8% of the total variability, while the remaining eigenvalues rapidly drop to zero. The first eigenfunction, with a dominant eigenvalue accounting for 71.8% of the total variation, is simple in structure and resembles a single cycle of a sine wave. The remaining eigenfunctions are also quite simple and roughly sinusoidal representing additional functional structure that cannot be captured by the mean structure of model (3).

Finally, we compared the prediction accuracy of SIVC with that of MVCM in Zhu et al. (2012). We randomly split the 213 subjects into a training set and a test set with corresponding proportions π and 1 − π, respectively. We used the training set to estimate all the parameters, and then predicted the responses of the testing set. The 100 replications were used to calculate the prediction errors corresponding π = 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7. Table 4 reports the MAE and RMSE of the prediction errors and indicates that SIVC significantly outperforms MVCM in terms of both MAE and RMSE.

Table 4.

Prediction results for the ADNI data analysis. EST is estimate, SE is standard error, MAE is mean absolute error, and RMSE is root mean square error.

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| π = 0.3 | π = 0.5 | π = 0.7 | |||||

| SIVC | EST | 0.114 | 0.1374 | 0.113 | 0.136 | 0.112 | 0.135 |

| SE | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| MVCM | EST | 0.599 | 0.650 | 0.599 | 0.627 | 0.600 | 0.628 |

| SE | 0.012 | 0.028 | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.013 | 0.016 | |

5. Conclusion

In this paper we have developed a single-index varying coefficient model for establishing a varying association between functional responses (e.g., image) and a set of covariates. We have developed an estimation procedure to estimate varying coefficient functions, link function, and the covariance function of individual functions. We have investigated a strategy to integrate the information across all grid points. We have used simulations and real data analysis to demonstrate that SIVC is a useful tool for modeling functional data.

Many important issues need to be addressed in future research. First, the computational burden associated with SIVC can be quite heavy making it infeasible for large-scale imaging data at this moment. We will develop more computationally efficient algorithms to address such challenge. Second, we need to develop an effective procedure to carry out statistical inference, such as hypothesis test. Third, it is scientifically interesting to extend SIVC to carry out regression analysis of longitudinal functional data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research of Dr. Zhu was supported by NIH grants 1UL1TR001111, MH086633, and EB005149-01 and NSF grants SES-1357666 and DMS-1407655. Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Footnotes

All Web Appendices, Tables, and Figures referenced in Sections 3.2 and 4.2 are available with this paper at the Biometrics website on Wiley Online Library. In addition, we will develop a companion software for SIVC and release it to the public through http://www.nitrc.org/ and https://www.nitrc.org/projects/fadtts/.

References

- Bowman FD, Caffo B, Bassett SS, Kilts C. A bayesian hierarchical framework for spatial modeling of fmri data. NeuroImage. 2008;39:146–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RD, Forzani L. Likelihood-based sufficient dimension reduction. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2009;104:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cook RD, Weisberg S. Discussion of “sliced inverse regression for dimension reduction”. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1991;86:328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Gossl C, Auer DP, Fahrmeir L. Bayesian spatiotemporal inference in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biometrics. 2001;57:554–562. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL. Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods in Econometrics. Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang CR, Wang JL. Functional single index models for longitudinal data. Annals of Statistics. 2011;39:362–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar N. The Statistical Analysis of Functional MRI Data. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li K-C. Sliced inverse regression for dimension reduction. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1991;86:316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhu H, Shen D, Lin W, Gilmore JH, Ibrahim JG. Multiscale adaptive regression models for neuroimaging data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 2011;73:559–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhu L. A semiparametric approach to dimension reduction. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2012;107:168–179. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2011.646925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhu L. Efficient estimation in sufficient dimension reduction. Annals of statistics. 2013;41:250–268. doi: 10.1214/12-AOS1072SUPP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhu L. On estimation efficiency of the central mean subspace. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2014;76:885–901. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda MF, Zhu H, Ibrahim JG. Bayesian spatial transformation models with applications in neuroimaging data. Biometrics. 2013;69:1074–1083. doi: 10.1111/biom.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JS. Functional regression. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application. 2015;2:321–359. [Google Scholar]

- Penny WD, Trujillo-Barreto NJ, Friston KJ. Bayesian fmri time series analysis with spatial priors. NeuroImage. 2005;24:350–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polzehl J, Spokoiny VG. Propagation-separation approach for local likelihood estimation. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields. 2006;135:335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay JO, Silverman BW. Functional Data Analysis. second. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss PT, Huang L, Mennes M. Fast function-on-scalar regression with penalized basis expansions. The International Journal of Biostatistics. 2010;6 doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JA, Silverman BW. Estimating the mean and covariance structure nonparametrically when the data are curves. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B. 1991;53:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Fahrmeir L. Spatial bayesian variable selection with application to functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2007;102:417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols T, Mackay C, Watkins K, Ciccarelli O, Cader M, Matthews P, Behrens T. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staicu A, Crainiceanu C, Carroll R. Fast analysis of spatially correlated multilevel functional data. Biostatistics. 2010;11:177–194. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxp058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J-L, Chiou J-M, Mueller H-G. Review of functional data analysis. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, van Eeden C, Zidek JV. Asymptotic properties of maximum weighted likelihood estimators. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2004;119:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Worsley KJ, Taylor JE, Tomaiuolo F, Lerch J. Unified univariate and multivariate random field theory. NeuroImage. 2004;23:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y. A constructive approach to the estimation of dimension reduction directions. The Annals of Statistics. 2007;35:2654–2690. [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Tong H, Li W, Zhu L-X. An adaptive estimation of dimension reduction space. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. 2002;64:363–410. [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Loh JM, Lindquist MA. Adaptive spatial smoothing of fMRI images. Statistics and its Interface. 2010;3:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Chen J. Statistical inferences for functional data. The Annals of Statistics. 2007;35:1052–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Fan J, Kong L. Spatially varying coefficient model for neuroimaging data with jump discontinuities. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2014;109:1084–1098. doi: 10.1080/01621459.2014.881742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Li R, Kong L. Multivariate varying coefficient model for functional responses. Annals of Statistics. 2012;40:2634–2666. doi: 10.1214/12-AOS1045SUPP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Wang T, Zhu L, Ferré L. Sufficient dimension reduction through discretization-expectation estimation. Biometrika. 2010;97:295–304. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.