Abstract

Inteins are invasive intervening sequences that perform an autocatalytic splicing from their host proteins. Among eukaryotes, these elements are present in many fungal species, including those considered opportunistic or primary pathogens, such as Candida spp. Here we reviewed and updated the list of Candida species containing inteins in the genes VMA, THRRS and GLT1 and pointed out the importance of these elements as molecular markers for molecular epidemiological researches and species-specific diagnosis, since the presence, as well as the size of these inteins, is polymorphic among the different species. Although absent in Candida albicans, these elements are present in different sizes, in some environmental Candida spp. and also in most of the non-albicans Candida spp. considered emergent opportunistic pathogens. Besides, the possible role of these inteins in yeast physiology was also discussed in the light of the recent findings on the importance of these elements as post-translational modulators of gene expression, reinforcing their relevance as alternative therapeutic targets for the treatment of non-albicans Candida infections, because, once the splicing of an intein is inhibited, its host protein, which is usually a housekeeping protein, becomes non-functional.

Keywords: Candida spp., intein, vacuolar ATPase, threonyl-tRNA synthetase, glutamate syntethase, molecular identification, new therapeutic targets

Introduction

Inteins are invasive genetic elements that occur as intervening sequences in conserved coding host genes. They are transcribed and translated with the flanking host protein sequences and then self-excised by protein splicing. The flanking protein sequences (exteins) are joined by a peptide bond, constituting the functional protein (Chong et al., 1996; Perler, 2005).

Over the past three decades, inteins have been detected mainly in unicellular microorganisms in the three domains of life and in viruses (Perler, 2002). Among the Eukarya domain, inteins are found mostly in fungi, some green algae and other basal eukaryotes (Liu, 2000; Butler et al., 2001, 2006). In a recent review, 2729 genomes of bacteria, 345 of archaea and 6648 of eukarya were analyzed (Topilina et al., 2015b) and 24, 47, and 1.1% of these genomes, respectively, presented at least one intein.

Inteins are usually found at conserved sites of housekeeping proteins that have vital functions in the cell, such as DNA and RNA polymerases, aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, recombinases, topoisomerases, helicases and essential components of the spliceosome (Novikova et al., 2014). Some hypothesis for this distribution already exist and are in part supported by some evolutionary scenarios, including probable horizontal transfer, as well as genetic mobility of inteins by homing endonuclease, which means that the spread and increase of this element in populations is due to a gene conversion process by homologous recombination, rather than any selective advantage (Nagasaki et al., 2005; Gogarten and Hilario, 2006; Swithers et al., 2009). This idea rendered to inteins the title of “parasitic” genetic elements during the past 25 years, although some domesticated inteins, such as HO gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed to have “gained” a function in the cell biology. In this specific case, the HO gene encodes for an endonuclease responsible for mating type conversion in yeast and its splicing domain is not active anymore (Koufopanou and Burt, 2005).

Nevertheless, recent works have evidenced a possible function for inteins in the post-translational regulation of gene expression. For instance, the splicing of SufB intein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis showed to be inhibited by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) when expressed in Escherichia coli. These stressful conditions are also experimented by M. tuberculosis inside the macrophage (Topilina et al., 2015a). Other evidence came from the splicing modulation of RadA intein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii according to the temperature, solution conditions and remote extein point mutations. So, RadA intein might function as an environmental sensor, releasing the intein for full activity only at optimal growth conditions for the native organism (high temperatures), while sparing ATP consumption under cold-shock. The authors observed intein splicing at low temperature only after adding a combination of the detergent SDS and the ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride, showing that, besides temperature, other factors may also interfere in RadA intein splicing (Topilina et al., 2015b).

Although the experimental evidence for the intein’s role in modulation of gene expression is based on a non-native context (different extein and different host cell), it is an important clue for the actual functionality of these elements in nature. Their presence in particular conserved motifs might be explained by an adaptive process (Novikova et al., 2014). Novikova et al. (2015) observed that inteins have a certain “preference” for specific functional domains of related housekeeping proteins, like ATPase domains for example, and this does not entirely fit to the models describing inteins as merely mobile parasitic elements. The authors argue that this intein distribution might be a result of a selective retention of these elements, which might be beneficial under certain environmental stresses. So, the sporadic nature of intein in closely related species could be explained by different environmental stresses. If there is no strong selective pressure for intein maintenance in a certain subpopulation and its presence reduces the adaptive value of the host microorganism, the intein-free alleles will increase in this population by means of natural selection (Gogarten and Hilario, 2006).

Nevertheless, we are far from a global understanding about the reason for intein persistence in different housekeeping host proteins, only in unicellular organisms, over millions of years. It seems consensual that their maintenance may be due to either their parasitic nature, since they are invasive elements, as well as to a possible role in specific physiological conditions of the host cell. Yet, among the mobile elements, inteins are the least studied, so that few inteins have already had their activity tested under different conditions; and therefore their real function is still a puzzle. Regarding that most of the produced knowledge on genome organization during the last years has been changing the status of many mobile genes, mainly retrotransposable elements, which are intensively studied, from parasitic entities to dynamic elements involved in genome evolution and gene expression (Mita and Boeke, 2016), it seems plausible that intein’s function in cell deserves more scientific investigation. The more we understand about inteins, the better we can explore their biotechnological applicability.

Few fungal inteins have been described, most of them are located in PRP8 (precursor mRNA protein) and VMA (vacuolar ATPase) coding genes, others can be observed in some RNA Polymerase subunits, GLT1 (glutamate synthase), CHS2 (chitin synthase) and THRRS (threonyl-tRNA synthetase) coding genes (Poulter et al., 2007). Most fungal inteins are present in the PRP8 and VMA genes. The PRP8 intein is widely dispersed in Fungi Kingdom (fungi containing this intein are found in different phyla), being present in many important human pathogens, such as Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gattii, Histoplasma capsulatum, Emmonsia spp., Paracoccidioides spp., Blastomyces dermatitidis, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus (Liu and Yang, 2004; Butler and Poulter, 2005; Butler et al., 2006; Theodoro et al., 2010). The VMA intein, on the other hand, is specifically distributed among Saccharomycetes, such as Saccharomyces, Zygosacchromyces and some Candida.

Here we updated the information on the intein distribution among Candida species and explored their potential as a source of phylogenetic information and, therefore, as species-specific diagnostic tool. Besides, the possible impact of the presence of these elements in housekeeping genes in Candida species life style was discussed raising their promising application as drug targets for most of the medically relevant non-albicans emergent Candida species.

Types of Inteins and How They Operate

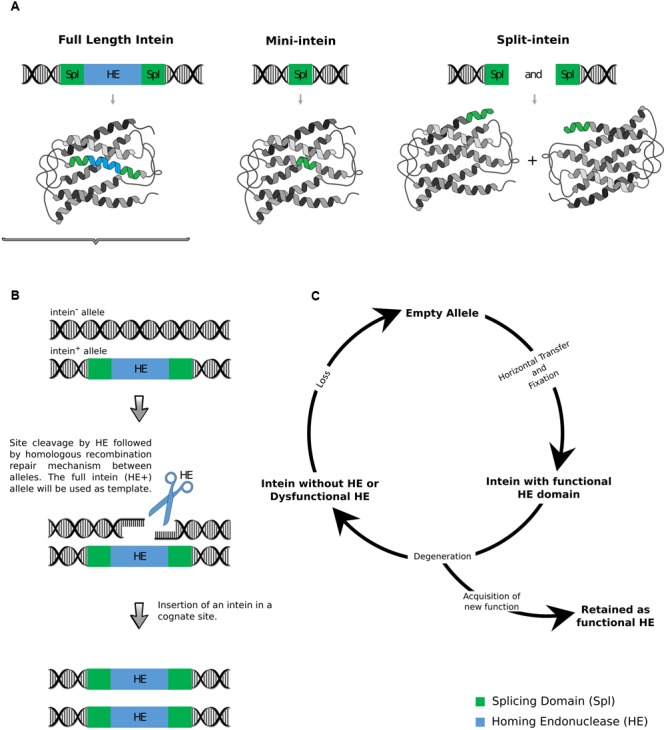

Inteins come in three configurations: full-length, mini and split (Figure 1A). The full-length inteins have a homing endonuclease domain (HE) splitting the splicing domain in N and C-Spl terminals. When active, the HE recognizes a cognate allele, without the intein, performs a double strand break (DSB) and, by homologous recombination, copies the intein using the intein-containing allele as template for DNA repair. Mini-inteins lack the HE domain and have a continuous splicing domain, while split-inteins are mini-inteins, whose N and C-Spl terminals are transcribed and translated with different exteins. When the N and C-Spl terminals are assembled, the intein suffers a trans-splicing reaction, ligating the different exteins (Wood et al., 1999; Volkmann and Iwaı, 2010).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Full length, mini and split inteins. (B) Intein mobility: DSB by HE and homologous recombination repair. (C) Cycle model of HE gain, degeneration, and loss within host populations modified from Burt and Koufopanou (2004).

Intein mobility is triggered by its HE domain which recognizes long, and therefore specific, DNA sequences (14–40 bp) lacking the intein, producing a DSB. The host repair system is then activated and the template containing the intein is “copied” to the recipient chromosome by a gene conversion event (Figure 1B), distorting the Mendelian segregation, causing a Super-Mendelian inheritance or a rapid dissemination and fixation of the intein in population. When all alleles of a certain population are occupied by the intein there is no selection pressure for functional HE, because both, functional and non-functional HEs will be equally maintained in population simply by cellular propagation and the HE domain is “free” to degenerate (Figure 1C). That is why the HE domain is expected to have more sequence variation, including its complete degeneration and/or deletion, than the splicing domain (Burt and Koufopanou, 2004; Koufopanou and Burt, 2005; Gogarten and Hilario, 2006).

Inteins are particularly interesting as a source of phylogenetic information because they present the well-preserved splicing domain (N and C terminals), with the conserved motifs A, B (for the N-splicing) and F, G (for the C-splicing), flanking the central and more variable HE domain, in the full-length inteins. The presence of the motifs C, D, E, and H, as well as the two aspartic acid residues, one in C and other in E, in HEs from LAGLIDADG family (the most common in fungal inteins), indicate that the HE domain is probably active (Gimble and Thorner, 1992; Liu, 2000; Posey et al., 2004). In mini-inteins, HE domains are supposed to be completely deleted. In addition, their location in highly conserved genes facilitates the design of primers for their amplification (Butler and Poulter, 2005; Theodoro and Bagagli, 2009; Prandini et al., 2013).

Besides its potential as molecular markers, inteins have been largely used for biotechnological purposes, accordingly to their functional mechanisms. The splicing domain, for example, is explored for purification of recombinant proteins, cyclization of proteins, protein labeling, production of selenoproteins (Miraula et al., 2015) and, for pathogenic microorganisms, it has been studied as a drug target (Paulus, 2007; Zhang et al., 2010). The HE domain has also been intensively studied as a biotechnological tool, in this case for genome editing, since these enzymes can be reprogrammed to specifically cut a genome site and deliver a gene of interest by homologous recombination. The applications of this technology are numerous for different social-economic fields, such as gene therapy for monogenic diseases, insect vector control (already developed for malaria mosquitoes) and gene delivery for transgenic plants, such as maize (Belfort and Bonocora, 2014).

Inteins in Candida Species

Candida species belong to Ascomycota phylum, Hemiascomycetes class and Saccharomycetales order. These species are distributed in three different clades making Candida a non-monophyletic group (Diezmann et al., 2004). With the exception of C. glabrata, which is in clade 3, together with C. castelli, C. norvegica, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other biotechnologically important yeast species, the most relevant clinical species of Candida are clustered in clade 1, which includes C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. metapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. viswanathii, as well as two non-pathogenic species, Candida maltosa and Lodderomyces elongisporus. C. guilliermondii, C. intermedia, C. famata, and C. zeylanoides are clustered in clade 2. The clades 1 and 2 are also referred as CUG group by distinctly translate this codon as serine instead of the standard leucine. Whether this attribute may play a hole in pathogenicity is still unknown (Diezmann et al., 2004).

Candida spp. can colonize human tissues in different ways, varying from a normal microbiota in the intestinal mucosa, contiguously to the vaginal mucosa, to a true pathogen. The transition to pathogenicity in Candida species, mainly in C. albicans, occurs generally due to the host immunological condition, leading to a microbiota unbalance, which associated with important virulence factors, such as biofilm formation and hydrolytic enzymes production, promotes fungal dissemination to other sites and organs. The clinical manifestations vary from a localized mucosa or skin infection to disseminated disease (Lagunes and Rello, 2016).

Although less common, disseminated candidiasis has significantly increased over the last 15 years, affecting mainly patients under debilitating and immunosuppressive conditions. Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Healthcare Safety Network, show that Candida species are the fifth pathogen related to nosocomial diseases and fourth pathogen among bloodstream infections – BSI (Wisplinghoff et al., 2004; Pfaller and Diekema, 2007). These nosocomial Candida infections are related to increment of invasive procedures and also to the intensive use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, particularly in patients admitted in Intensive Care Units – ICU (Colombo et al., 2013).

About 95% of diagnosed fungal infections are related to Candida spp., mainly involving the species C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. guilliermondii, C. lusitaniae, C. dubliniensis, C. pelliculosa, C. kefyr, C. lipolytica, C. famata, C. inconspicua, C. rugosa, and C. norvegensis, but C. albicans is still the most frequent species causing infection (Yapar, 2014). However, Candida infections caused by non-albicans Candida spp. have been increasing in the last few years (Richardson and Lass-Flörl, 2008). In a recent epidemiological analysis, non-albicans species accounted for more than 50% of all cases of invasive candidiasis in patients enrolled in the Prospective Antifungal Therapy Alliance, a sentinel surveillance network comprising 23 medical centers in the US and two in Canada. The non-albicans species identified were C. glabrata (46.4%), C. parapsilosis (24.7%), C. tropicalis (13.9%), C. krusei (5.5%), C. lusitaniae (1.6%), C. dubliniensis (1.5%) and C. guilliermondii (0.4%) (Pfaller et al., 2014). While C. albicans infections have been progressively replaced by C. glabrata infections in North America and in many European countries, C. parapsilosis or C. tropicalis are the most frequent non-albicans species in Latin America (Nucci et al., 2010; Cleveland et al., 2012; Lockhart et al., 2012). The central factor for the emergence of these non-albicans Candida spp. seems to be the undiscriminating use of antifungal drugs (Yapar, 2014).

The treatment of Candida infections, mainly candidemias, is based on antifungal agents that interfere on different metabolic pathways being fungicide, such as polyenes, azoles and equinocandis, or fungistatic, such as nucleoside analogs (Lopez-Martinez, 2010; Maubon et al., 2014). The polyenes act on the ergosterol, increasing the permeability of cell membrane by producing aqueous pores; the azoles inhibit the ergosterol biosynthesis and the echinocandins inhibit the synthesis of 1,3 β-glucan, a polysaccharide responsible for the cell wall integrity; and the nucleoside analogs inhibit DNA synthesis being used in combination with amphotericin B or fluconazole (Spampinato and Leonardi, 2013; Paramythiotou et al., 2014), which are the usual chosen drugs for treatment of Candida infections (Paramythiotou et al., 2014). The antifungal susceptibility can be easily accessed by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) reference microdilution method and also by commercially available antifungal susceptibility testing systems, such as the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric panel (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH, USA) (Pfaller et al., 2012).

Monitoring changes in antifungal drug resistance is as important as determining the incidence of candidemia by different Candida species. A recent report of surveillance for candidemia in Atlanta, GA, USA and Baltimore, MD, USA over a 5-year period, showed a shift in the species distribution among causative organisms, with a significant increase in C. glabrata, as well as in its resistance to echinocandin and fluconazole (Wang et al., 2012; Cleveland et al., 2015). This emergence of antifungal resistance, due to inappropriate prescriptions (Sardi et al., 2013), and the usual toxic side effects of some of these drugs strengthen the demand for new therapeutic targets.

The fungal systemic disease caused by Candida is an important cause of mortality, mainly in nosocomial infections and, since the antifungal susceptibility may vary among the different species (Bassetti et al., 2015), the correct diagnosis at species level is necessary. This can be accomplished by classical phenotypic methods, biochemical and physiological tests, which have automated versions, such as Vitek 2 ID – YST (bioMerieux), (Higashi et al., 2015). However, molecular epidemiological studies using different molecular markers (25S group I intron, rDNA D1/D2 region and ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) have revealed intraspecific variation in C. albicans and non-albicans Candida species and its correlation to antifungal susceptibility (Miletti and Leibowitz, 2000; Karahan et al., 2004; Steuer et al., 2004; Fahami et al., 2010; Gurbuz and Kaleli, 2010; Merseguel et al., 2015).

Besides intraspecific variation, molecular markers have also pointed out the existence of cryptic species in C. parapsilosis, actually composed by three species: C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis (Tavanti et al., 2005), which present differences in virulence and antifungal response. C. parapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis are more virulent in reconstituted human tissues models and the minimal inhibitory concentration values (MIC) of amphotericin B, caspofungin, anidulafungin and micafungin for C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis isolates were significantly lower than those for C. parapsilosis (Gacser et al., 2007; Lockhart et al., 2008).

The correct recognition of close fungal genotypes or cryptic species would improve the treatment; however, this is not achieved by the usual biochemical methods available in most routine laboratories, mainly in developing countries. The distinction of these very close Candida species requires molecular techniques such as PCR- RFLP of SADH gene (Tavanti et al., 2005), quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Hays et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2012), pyrosequencing (Borman et al., 2009), microsatellite analysis (Lasker et al., 2006) or matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time (MALDI-TOF MS analysis) (Quiles-Melero et al., 2012). This last technique is based on the mass spectrum analysis of crude protein cell extract and requires validated databases for the achievement of rapid and reliable pathogen identification. Recent researches have created databases for the identification of bloodstream yeasts and showed practically 100% accuracy in distinguishing medically important species, such as C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. pelliculosa, C. orthopsilosis, C. albicans, C. rugosa, C. guilliermondii, C. lipolytica, C. metapsilosis, C. nivariensis (De Carolis et al., 2014; Ghosh et al., 2015). The main apparent disadvantage of this technology is the up-front cost of purchasing a MALDI-TOF MS instrument; however, it is offset in about 3 years, providing a noteworthy long-term cost saving for the laboratory (Tran et al., 2015). Some authors have also pointed out the relatively low analytical sensitivity of the method, as well as the few advances for distinguishing filamentous fungi, when compared to the yeast databases (Bailey et al., 2013).

In this scenario, intein research is particularly interesting because they might be a valuable additional or alternative molecular markers for species identification, such as observed for Cryptococcus spp., Paracoccidioides spp., Histoplasma capsulatum, and Candida spp. (Butler and Poulter, 2005; Theodoro et al., 2008; Prandini et al., 2013; Theodoro et al., 2013; Satish Kumar and Ramesh, 2014) and also, since they are usually present in housekeeping genes and absent in multicellular eukaryotes, they can be explored as drug targets, because protein splicing inhibition would make the host protein non-functional (Paulus, 2003; Liu and Yang, 2004). However, drug screening for the inhibition of intein splicing has only been carried out for bacterial pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis. The intein MtuRecA was inserted in the GFP (green fluorescent protein) coding sequence and its splicing efficiency was evaluated according to the fluorescence emission. More than 85 thousand compounds were tested. Some electrophilic compounds, such as cisplatin inhibited the intein MtuRecA splicing by blocking the intein’s first N-Spl cystein residue (Paulus, 2007; Zhang et al., 2010).

Three host proteins, considered essential for cell physiology, have been observed containing inteins in Saccharomycetales species: vacuolar ATPase (VMA), threonyl-tRNAsynthetase (ThrRS) and glutamate synthase (GLT1) (Poulter et al., 2007).

In order to update the distribution of these inteins in Candida, we carried out a search for inteins sequences in 81 sequenced genomes of 30 Candida species (Supplementary Table 1). Public Contigs deposited into MycoCosmosDB and NCBI WGS Databases were downloaded. By using GetORF program, all genomes were converted into six frames amino-acids sequences, for their ORFs deduction. Using those sequences, a local database was created, using NCBI Local BLAST+ (v.3.1.4) program in a UNIX system. Finally, sequences of VMA, ThrRS, GLT1 inteins were blasted to this database. This analysis revealed inteins in VMA, ThrRS and GLT1 proteins in Candida species, in which they have not been described before.

The VMA, ThrRS and GLT1 inteins are present in 14, 6, and 3 Candida species, respectively. The differences among Candida species concerning intein presence and/or size polymorphism (Table 1) can be easily accessed as molecular markers for species differentiation.

Table 1.

Inteins encoded by Candida spp.

| Host protein | Candida species | Intein nomenclature | Size(aa residues) | Essential aspartate residue∗ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block C | Block E | ||||

| VMA1, vacuolar ATPase | C. castellii∗∗ | CcaVMA | 367 | D | I |

| C. apicola∗∗ | CapVMA | 389 | T | K | |

| C. glabrata | CglVMA | 415 | S | Q | |

| C. nivariensis∗∗ | CniVMA | 424 | S | K | |

| C. bracarensis∗∗ | CbrVMA | 420 | S | K | |

| C. homilentoma∗∗ | ChoVMA | 491 | D | D | |

| C. sorboxylosa∗∗ | CsorVMA | 374 | T | V | |

| C. tropicalis | CtrVMA | 471 | I | A | |

| C. sojae∗∗ | CsoVMA | 501 | D | N | |

| C. metapsilosis | CmeVMA | 454 | N | D | |

| C. orthopsilosis | CorVMA | 530 | D | D | |

| C. intermedia∗∗ | CinVMA | 455 | T | D | |

| C. maltosa∗∗ | CmaVMA | 451 | N | D | |

| C. famata | CfaVMA (DhaVMA) | 395 | N | D | |

| ThrRS, threonyl-tRNA synthetase | C. tropicalis | CtrThrRS | 345 | N | S |

| C. sojae∗∗ | CsoThrRS | 338 | T | S | |

| C. maltosa∗∗ | CmaThrRS | 444 | D | D | |

| C. orthopsilosis | CorThrRS-A | 180 | – | – | |

| C. orthopsilosis | CorThrRS-B | 439 | D | D | |

| C. parapsilosis | CpaThrRS | 183 | – | – | |

| C. metapsilosis | CmeThrRS | 172 | – | – | |

| GLT1, glutamate synthase | C. famata | CfaGLT1 | 607 | D | D |

| C. carpophila∗∗ | Ccar GLT1 | 557 | D | D | |

| C. guilliermondii | Cgu GLT1 | 553 | E | D | |

∗Aspartic acids residues from block C and E considered essential for HE domain function. ∗∗Inteins found in new available Candida genomes.

Some Candida species have more than one intein in their genome. The species C. maltosa, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis present both VMA and ThrRS inteins and C. famata presents both VMA and GLT1 inteins (Table 1). No inteins were found in C. albicans, C. arabinofermentans, C. auris, C. boidinii, C. dubliniensis, C. succiphila, C. tanzawaensis, C. tenuis, C. infanticola, C. krusei, C. lusitaniae, and C. ciferri.

Inteins are not exclusively found in clinically relevant Candida species, some of the intein containing species listed on Table 1 are frequently isolated from environmental sources. For instance, C. apicola is found in wine and cachaça fermentation processes (Vega-Alvarado et al., 2015), C. homilentoma is commonly associated to insects (Yun et al., 2015), C. sorboxylosa was originally found in fruits and described as close related to C. krusei (Nakase, 1971) and C. sojae can be isolated from water-soluble substances of defatted soybean flakes (Nakase et al., 1994).

Some environmental species presenting inteins, listed on Table 1, have been rarely reported in invasive candidemia in human. This is the case of C. intermedia, isolated from soil, beer, grapes and also present on skin, throat, or animal feces (Ruan et al., 2010), as well as C. famata (Debaryomyces hansenii), which is commonly found in natural substrates and in various types of cheese and accounts for 0.08–0.5% of isolates recovered during invasive candidiasis. C. famata is sometimes misidentified as C. guilliermondii, which has a variety of environmental sources and is a common constituent of the normal human microbiota, being associated with only 1–2% of candidemias (Desnos-Ollivier et al., 2008). The species C. castellii, C. nivariensis and C. bracarensis belong to Nakaseomyces genus (Kurtzman, 2003), being closely related to C. glabrata. The high genetic proximity between C. nivariensis or C. bracarensis and C. glabrata may have caused their misidentification as C. glabrata (Alcoba-flórez et al., 2005; Correia et al., 2006; Bishop et al., 2008), so that their emergent character may have been due to recent advances in molecular epidemiology tools. The ecological niches of these species are still poorly understood. C. nivariensis has been isolated from flowering plants in Australia, indicating a possible environmental source for human infections (Lachance et al., 2001). Despite their environmental aspect, C. nivariensis and C. bracarensis show an expansion in EPA genes, a family of glycosylphosphatydylinositol (GPI)-anchored cell-wall protein, considered an important virulence factor for emergent pathogens, such as C. glabrata (Gabaldón et al., 2013).

VMA Inteins

The first evidence of an intein arose from structural studies and expression analysis of the vacuolar ATPase gene and its encoded protein (VMA) in S. cerevisiae (Hirata et al., 1990). Since then, VMA inteins have been described in several species of Saccharomycetales order, including yeasts of biotechnological and medical interests, and seem to follow a model of invasion, fixation, degeneration, loss and reinvasion (Okuda et al., 2003; Burt and Koufopanou, 2004; Butler et al., 2006), leading to its sporadic distribution. For this reason two very close sister species might differ concerning the presence of the intein in the VMA gene. Most of the VMA inteins have a degenerated HE domain (from LAGLIDADG family). Some of the few active HE may also recognize allelic sites in other yeast species. Actually, the HE domain of the VMA intein (also called VDE) from S. cariocanus is more effective in cutting the VMA recognition site of S. cerevisiae than its own VMA (Posey et al., 2004), which would allow horizontal transfer. Notwithstanding, once the intein is acquired, it tends to be transmitted vertically, reflecting the group phylogeny (Butler et al., 2006; Goodwin et al., 2006). Comparing the VMA intein patterns in related Saccharomyces species, it was also possible to document hybridization process, such as in a diploid strain of S. carslbergensis that contain two distinct alleles, one with the VMA intein, supposedly received from S. cerevisiae, and the other with only the intein-less VMA sequence, probably received from S. pastorianus (Okuda et al., 2003).

The amino acid sequence alignment of VMA inteins in Candida species shows large degeneration process in the HE domain, mainly in those species lacking both aspartate residues, one in block C and the other in E (Supplementary Figure S1).

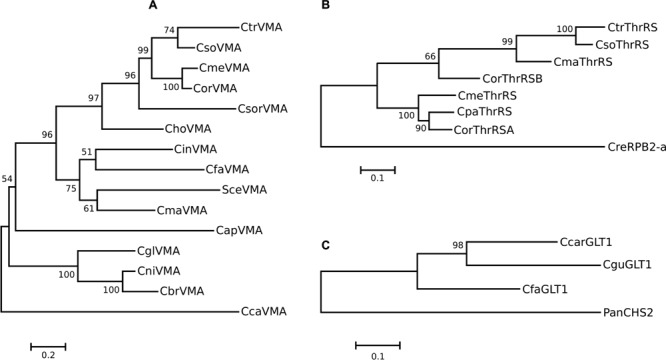

The phylogenetic relationships among these elements revealed a non-vertically inheritance pattern, since the intein from C. maltosa was clustered apart from C. tropicalis, C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis inteins (Figure 2A). According to a combined maximum likelihood analysis of six genes (ACT1, EF2, RPB1, RPB2, 18S rDNA, and 26S rDNA) (Diezmann et al., 2004) these four species belong to a unique clade, named clade 1. Besides, although C. glabrata, C. castellii, C. nivariensis and C. bracarensis share a common ancestor with S. cerevisiae, belonging to clade 3 (Diezmann et al., 2004), their inteins were not clustered together in our analysis. Actually, the intein SceVMA showed to be closer to CmaVMA, than to the inteins of other species from clade 3. These observations corroborate the hypothesis of VDE adaptation for horizontal transfer. This hypothesis is supported by the high conservation of its 31 bp long recognition site and also by the incongruence between host and inteins phylogenies. This horizontal transfer seems to occur preferentially between closely related species, probably by eventual hybridization events (Goddard and Burt, 1999; Koufopanou et al., 2002).

FIGURE 2.

Molecular Phylogenetic analysis by Maximum Likelihood method conducted in Mega v.6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013) for the amino acids aligned sequences of the inteins VMA, ThrRS and GLT1 from Candida and their close relative inteins. The trees with the highest log likelihood are shown. The trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All sites containing alignment gaps were removed (Complete deletion). (A) VMA intein phylogeny inferred based on the Le_Gascuel_2008 model (Le and Gascuel, 2008). A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [5 categories (+G, parameter = 2.0642)] and the rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I], 8.7480% sites). (B) ThrRS intein phylogeny inferred based on the Whelan And Goldman model (Whelan and Goldman, 2001). The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable. (C) GLT1 intein phylogeny inferred based on the Whelan And Goldman model (Whelan and Goldman, 2001). The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable.

Horizontal transfer has also been proposed as an explanation to the peculiar distribution of other inteins. For instance, the PRP8 intein, which occurs, sporadically, in many ascomycetes is also found in only four basidiomycetes from Tremellales order (Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gattii, Cryptococcus laurentii and Cryptococcus bacillisporus) (Butler and Poulter, 2005; Butler et al., 2006). It was speculated that a co-phagocytosis event by a metazoan macrophage could be a possible scenario for PRP8 intein transfer from an ascomycete to a basidiomycete (Poulter et al., 2007).

It seems plausible that, for sharing part of their ecological niches, such as metazoan tissues, as well as some environmental sources, and being closely related, Candida species could hybridize creating suitable conditions for HE invasion in new and empty alleles, carrying the VMA intein. In fact, there are some researches that point out the occurrence of hybridization events in Candida. For instance, hybrid lineages between the two subspecies of C. orthopsilosis have been described in distant continents (Pryszcz et al., 2014). The same authors also found genomic evidence that some C. metapsilosis strains worldwide distributed are heterozygous hybrids resulting from the same past hybridization event involving two non-pathogenic parental lineages. This observation corroborates the idea of hybridization as a source for the emergence of virulence attributes (Pryszcz et al., 2015).

The vacuolar H+-ATPase is a fundamental and therefore highly conserved enzyme in almost every eukaryotic cell. It functions as ATP-dependent proton pumps energizing various organelles and membranes, making numerous secondary transport processes possible. Yeast genetics researches identified the properties of individual subunits of V-ATPase and discovered the factors involved in its biogenesis and assembly. Null mutations in genes encoding V-ATPase subunits of S. cerevisiae result in a phenotype that is unable to grow at high pH and is sensitive to high and low metal-ion concentrations (Nelson et al., 2000).

The VMA intein is inserted in a P-loop containing the Nucleoside Triphosphate Hydrolase domain of VMA protein, the most prevalent domain of the several distinct nucleotide-binding protein folds. The most common reaction catalyzed by enzymes of the P-loop NTPase fold is the hydrolysis of the beta-gamma phosphate bond of a bound nucleoside triphosphate (NTP). The energy from NTP hydrolysis is typically utilized to induce conformational changes in other molecules, which constitutes the basis of the biological functions of most P-loop NTPases (Leipe et al., 2004).

The VMA intein is sporadically distributed among Candida species, with very close related species differing in its presence. For instance, this intein is absent in C. parapsilosis, while it is present, in different sizes, in C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis (as described on Table 1), although C. orthopsilosis and C. parapsilosis share a most recent common ancestor, being closer to each other than either of them to C. metapsilosis (Pryszcz et al., 2015). It is possible that the clonal nature of C. parapsilosis lineage (Tavanti et al., 2005), in contrast to the possible mating occurrence in C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis (Sai et al., 2011; Pryszcz et al., 2015), could have contributed to the loss of VMA intein. On the other hand, the sexual reproductive mode, as well as the occurrence of hybridization events, combined to a certain adaptation for lateral transfer of VDE, would prevent the intein loss in C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. The presence/absence and size polymorphisms make the VMA intein an easy strategy to differentiate these cryptic species (Prandini et al., 2013), constituting the most practical DNA-based method proposed so far for the correct identification of the species from the complex, since it does not requires PCR digestion or sequencing. However, additional retrospective analysis of more isolates known to belong to C. parapsilosis complex should be carried out in order to better explore the VMA intein as a phylogenetic tool.

Zhang and Rao (2010) discussed the contributions of V-ATPase function to pathogenicity and reviewed the functional link between V-ATPase and the lipid components of the membrane, showing that ergosterol removing or inhibition (performed by azoles, morpholines and allylamines) alters the V-ATPase conformation. Also, erg mutants showed the same phenotype of vma mutants, which is the inability to grow in alkaline medium. Besides, the authors also pointed out that fluconazole treatment, as well as ERG3 deletion or vma7-/- mutation cause inhibition of filamentation, which, for Candida pathogenic species, is an important virulence treat for tissue invasion (Lo et al., 1997; Saville et al., 2006; Bastidas and Heitman, 2009). Furthermore, C. albicans vma7-/- mutant cells are eliminated by macrophages and fail to colonize epithelial cells. These observations show that azole drugs may have an effect on V-ATPase function, disrupting the pH homeostasis in fungal pathogens (Zhang and Rao, 2010). Despite no data is available for vma mutants in non-albicans Candida species, the conservative aspect of the VMA protein makes plausible the assumption that this protein is actually essential for the survival of all yeast species, mainly in alkaline medium, and it may also play an important role for fungal maintenance during infection in other Candida species. For this reason, we suppose this data reinforce the importance of the intein in V-ATPase protein as a potential drug target for the inhibition of the normal function of this protein in those Candida species that present this genetic element.

It is interesting to note that the most prevalent Candida species in hospital infections is C. albicans, which does not have any intein, while non-albicans Candida spp. predominated in samples collected from environment (Ferreira et al., 2013). If we consider that some physiological conditions may decrease the intein splicing efficiency, the existence of an intein in an important protein can modulate its post-translational expression. Regarding the importance of the V-ATPase for cell homeostasis and even for filamentation, it seems reasonable that the loss of this intein in C. albicans lineage might have contributed, together with many virulence factors, for its maintenance in vertebrate tissue as a member of the normal microbiota and eventual pathogen. The absence of the intein in VMA protein could have contributed, for example, for the highly efficient filamentation of C. albicans when compared to other Candida species, that have the VMA intein, such as C. glabrata and C. tropicalis, whose pathogenicity might be associated with many other virulence factors rather than to filamentation capacity (Sudbery, 2011). Among the non-albicans Candida spp., whose incidence is becoming more expressive, are the species C. parapsilosis and C. krusei, which also lack the VMA intein. In these species, the VMA gene expression is not under post-translational regulation controlled by intein splicing, so that it could be more efficiently expressed in a larger variety of physiological conditions when compared to the intein containing species. However, no experiment has been conducted to assess the splicing of the VMA intein in Candida species in different physiological and stressing conditions.

ThrRS Intein

The ThrRS intein is inserted in the threonyl-tRNAsynthetase gene (THRRS) which encodes an aminoacyl-tRNAsynthetase (aaRS), responsible for engaging the amino acid threonine with the corresponding tRNA (anticodon). The ThrRS intein is located in the Class II tRNA aaRS catalytic core domain. Class II amino acyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) share a common fold and generally attach an amino acid to the 3′ OH of the tRNA ribose. This domain is primarily responsible for ATP-dependent formation of the enzyme bound aminoacyl-adenylate (O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten, 2003).

The ThrRS intein has already been described as full-length intein in C. tropicalis and as mini-intein in C. parapsilosis, as well as in C. orthopsilosis (CorThrRS-A) and C. metapsilosis. Nevertheless, some isolates of C. orthopsilosis present a full-length intein (CorThrRS-B) in the same insertion site. This was the first report of two types of intein in the same insertion site in the same species (Prandini et al., 2013), though in distinct strains. The finding of both inteins (CorThrRS-A and CorThrRS-B in the same C. orthopsilosis strain is also possible, since they are diploids. Here we also described a full-length intein in C. maltosa (CmaThrRS), which, like the CorThrRS-B, presents both aspartic acids residues (D), and in C. sojae (CsoThrRS), whose aspartic acid residues were replaced by the amino acids T and S (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S2).

Phylogeny of the ThrRS inteins clearly distinguished the Candida species from the C. parapsilosis complex (Figure 2B), but it does not corroborate the species phylogeny initially proposed, in which C. metapsilosis and C. orthopsilosis share a most recent common ancestor and are the sister clade of C. parapsilosis (Tavanti et al., 2005; Wolfe et al., 2012). However, a more recent phylogenetic analysis using 396 conserved, as well as a super-tree derived from the whole phylome using a gene tree parsimony approach, supported a basal position of C. metapsilosis to the exclusion of C. orthopsilosis and C. parapsilosis (Pryszcz et al., 2015).

The splicing domain of the intein CorThrRS-B (a full-length intein) does not group with the other intein of C. orthopsilosis, the CorThrRS-A (a mini intein), since it is more closely related to ThrRS inteins from C. tropicalis, C. maltosa and C. sojae (Figure 2B). This might reflect the occurrence of independent intein invasions. The ancestor of C. orthopsilosis species might have its THRRS gene invaded by an intein (ThrRS-A), which, following the homing cycle “rules,” might have been fixed in most of population, leading to its HE degeneration (explaining its current mini-intein structure). Since the homing endonuclease is no longer functional, empty sites could have arisen being occupied again by another intein, the ThrRS-B, which also invaded the THRRS gene from C. tropicalis, C. sojae, and C. maltosa.

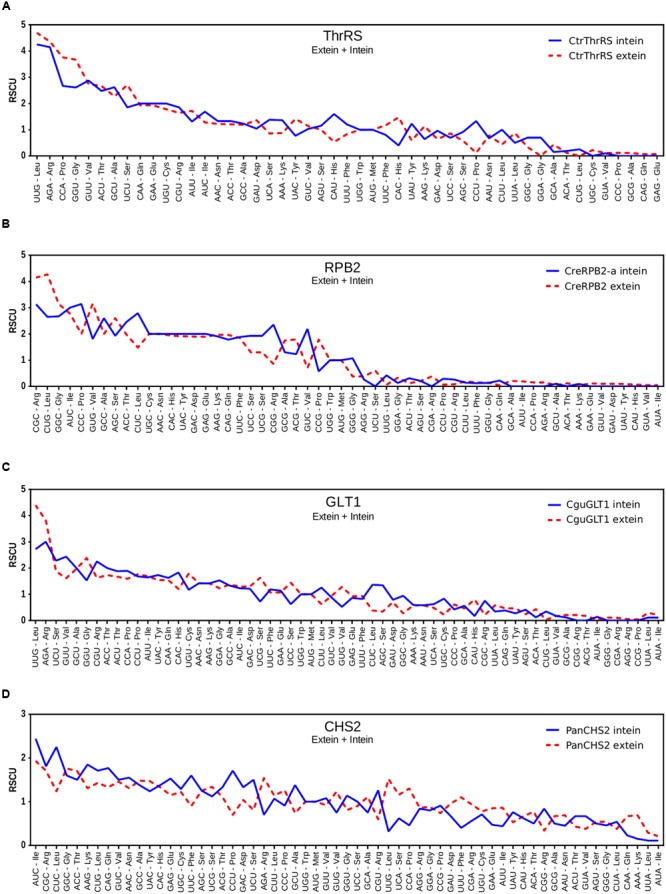

The ThrRS intein has 29.33% of similarity with one of the four inteins located in the RNA polymerase II of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (the CreRPB2-a intein), a green unicellular algae. Indeed, the RPB2-a intein was discovered because of its similarity to the threonyl-tRNA synthetase intein from C. tropicalis, which suggest the occurrence of horizontal transfer (Goodwin et al., 2006; Poulter et al., 2007). This horizontal transfer, if recent, can be evidenced by the sequence similarity between the exteins and between the inteins and also by differences in codon usage between intein and extein, as demonstrated for the DnaB intein and its extein in Rhodothermus marinus (Liu and Hu, 1997). If two homologous inteins are not related through recent lateral transfer, the sequence divergence between them is larger than between their extein sequences, in a similar way that happens to introns, whose sequences usually diverge faster than exon sequences. Accordingly, in the well-known case of lateral transfer of DnaB intein from Synechocystis sp. to R. marinus, the intein aminoacid sequences share a 54% sequence identity that is noticeably higher than the 37% sequence identity shared by the DnaB extein sequences (Liu and Hu, 1997). In the case of the CtrThrRS and CreRPB2 inteins: their identity is 29.33%, which is higher than the 17.77% sequence identity shared by the extein sequences. But, of course, this low identity is already expected since these exteins are not homologous genes. However, no pronounced deviation in relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) (Sharp et al., 1986) is observed between the ThrRS intein and its extein or between the RPB2-a intein and its extein, suggesting that the possible lateral transfer was not a recent event (Figures 3A,B). The same is not observed between both inteins and also between both exteins, which present a great codon usage deviation (Supplementary Figures S4A,B).

FIGURE 3.

Graphic view of RSCU values for codon usage in ThrRS, GLT1, RBP2 and CHS2 inteins and their respective exteins. Comparison between: (A) RSCU values for CtrThrRS intein and THRRS gene of C. tropicalis without intein; (B) RSCU values for CreRBP2-a intein and RPB2 gene of C. reinhardtii without intein; (C) RSCU values for CguGLT1 intein and GLT1 gene of C. tropicalis without intein and (D) RSCU values for PanCHS2 intein and CHS2 gene of P. anserina without intein.

The aaRSs are considered important therapeutic target for antibiotics, antifungals and antiprotozoal drugs. Most inhibitors of aaRSs act by competitive binding at the active site where normally the cognate amino acid would bind (Vondenhoff and Van Aerschot, 2011; Kalidas et al., 2014). Most of these compounds are not commercial and few have reached the stage of clinical development. Icofungipen, for example is an antifungal that inhibits IleRS, presenting satisfactory clinical efficacy and safety, although low mycological eradication rates were observed in HIV-positive patients (Ochsner et al., 2007). Cispentacin, a cyclic β-amino acid that has been isolated from Bacillus cereus and Streptomyces setonii inhibits IleRS and proved to be effective against C. albicans infection in mice (Konishi et al., 1989; Ochsner et al., 2007).

The presence of an intein in the ThrRS protein would represent an additional approach for its inhibition, as well as it would assure a specific and therefore safer antifungal mechanism, because, despite the functional evolutionary convergence, as all the aaRS carry out the same basic biochemical function (O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten, 2003), only the ThrRS protein of the fungal pathogen has an intervening intein.

GLT1 Intein

The GLT1 gene codifies an oligomeric enzyme named glutamate synthase (GOGAT), which is composed by three identical subunits. This enzyme, together with glutamine synthase, encoded by GLN1 gene, is involved in one of the three pathways for the synthesis of glutamate, in yeast cells. GOGAT catalyzes the reductive synthesis of L-glutamate from 2-oxoglutarate and L-glutamine via intramolecular channeling of ammonia. It is a multifunctional enzyme that functions through three distinct active centers, carrying out L-glutamine hydrolysis, conversion of 2-oxoglutarate into L-glutamate and electron uptake from an electron donor (Filetici et al., 1996).

In this review we described, for the first time the GLT1 intein in C. carpophila, a distinct species that is closely related to both P. guilliermondii and C. fermentati. Before being described as a different species, C. carpophila, previously named as C. guilliermondii var. carpophila, was considered as a member of a genetically heterogeneous complex comprising several phenotypically indistinguishable taxa inside C. guilliermondii (Vaughan-Martini et al., 2005).

Both CfaGLT1 and CcarGLT1 inteins present the two aspartic acid residues, known to be essential for HE function, while CguGLT1 presented a substitution to E residue in the first aspartate (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S3). Phylogenetic analysis previously indicated that these inteins were very closely related to a non-allelic intein, the PanCHS2 (the intein in chitin synthase 2, from Podospora anserina) (Poulter et al., 2007). Similarly to that observed for the ThrRS intein, the RSCU between the GLT1 intein and its extein is concordant for most codons, also indicating that the possible lateral transfer of this intein from CHS2 to GLT1 is ancient (Figures 3C,D). The same is not observed between both inteins and also between both exteins, which present a great codon usage deviation (Supplementary Figures S4C,D).

As we can infer from Figure 2C, the GLT1 intein probably invaded the GLT1 gene before the divergence of Candida species from the clade 2 proposed by Diezmann et al. (2004), which includes C. guilliermondii, C. intermedia, C. famata and C. zeylanoides. Evidently this intein was lost in C. intermedia and C. zeylanoides, probably due to HE degeneration and genetic drift.

According to KEEG Orthology (entry: YDL171C), the host protein for this intein, the GOGAT protein, is involved in cryptic pathways such as (i) alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism; (ii) nitrogen metabolism; (iii) biosynthesis of secondary metabolites; (iv) biosynthesis of antibiotics; and (v) biosynthesis of amino-acids. Connecting all these pathways, there is high nitrogen dependency. Nitrogen is a very important component, which is present in the chemical structure of almost every single molecule in cell’s constituents. Yeasts cannot make their own nitrogen by taking it from the air, so it is necessary external sources of this macronutrient to keep it constantly available. So, the cell needs to adapt their metabolism to obtain or catabolize the available nitrogen sources, such as ammonia, glutamine, asparagine, glutamate, and proteins.

As the life style of Candida ssp. ranges from environmental to commensal and/or parasitic, the nutrient availability varies as well. During infection, Candida ssp. needs to obtain nitrogen from a broad range of different sources, which may change dramatically depending on the anatomical site of infection. The changing from commensal to pathogenic growth depends on a differential gene expression, which allows the establishment of infection (Ramachandra et al., 2014).

Candida spp. are constantly exposed to stressful agents, such as nitrogen deprivation in their microenvironment changing. Also, it is known that nitrogen source utilization modulates some morphological and physiological changes, sexual and asexual sporulation and virulence factors expression (Marzluf, 1997; Biswas et al., 2007). Therefore, the presence of the intein in this protein, by a post-translational expression modulation, could allow fine adjustments in nitrogen pathway during infection.

GLT1 expression is highly modulated in S. cerevisiae, being repressed in the presence of glutamate rich nitrogen sources, which suggests that GOGAT may have an important role in glutamate biosynthesis under conditions where this amino acid becomes limiting. It seems that GOGAT constitute an ancillary pathway, supplying low but continuous glutamate production, even in the presence of other glutamate pathways, suggesting that a high intracellular glutamate concentration may be needed for optimal growth, mainly under conditions in which carbon and nitrogen are limiting (Valenzuela et al., 1998). GLT1 knockout evaluation showed that GOGAT does not significantly influence cellular physiology, corroborating its auxiliary characteristic in glutamate synthesis (Brambilla et al., 2016), though GOGAT non-expression yeasts accumulated more ROS, when treated with hydrogen peroxide.

The use of different glutamate pathways in Candida was compared to Saccharomyces (Holmes et al., 1989). The authors compared the NADP+-dependent GDH and GOGAT pathways activities in four Candida species (C. albicans, Candida pseudotropicalis, C. parapsilosis and C. tropicalis) and S. cerevisiae. The relative contribution of GOGAT in S. cerevisiae is around 1.6%, while among Candida species it ranges from 13 to 70%, being most expressive in C. albicans. This observation may indicate that, in Candida, GOGAT pathway may have a greater impact in nitrogen metabolism than in S. cerevisiae, so a post-translational regulatory role of the intein in this gene would be noteworthy in Candida. Thus, if the relative contribution of GOGAT is as expressive in non-albicans Candida species containing GLT1 intein as it is in C. albicans, the GLT1 intein could also be considered an additional drug target.

Conclusion

In this review, the list of intein containing Candida species was updated, as well as their sequence features and phylogenetic relationships. The horizontally transferred nature of VMA inteins was corroborated by our phylogeny. The possible lateral transfer of inteins from C. reinhardtii (RPB2 gene) and P. anserina (CHS2 gene) to THRRS and GLT1 genes, respectively, of Candida species, might be very ancient, since no significant deviation of RSCU was observed between these inteins and their respective exteins. Besides the peculiar evolutionary history of the inteins, their presence or absence, as well as their polymorphic sizes, should also be explored as molecular markers for species or cryptic species recognition, assisting the diagnosis and the therapeutic choices, since different species diverge in their clinical and antifungal susceptibility aspects.

The recent discussions about whether inteins are parasitic genetic elements or post-translational expression modulators gives rise to important questions: Can the splicing efficiency of an intein be altered under different life-style conditions of opportunistic or pathogenic fungal species? Can inteins regulate gene expression in different ways during infection? Here we reviewed the importance of the VMA, ThrRS and GLT1 genes in the yeast cell physiology. Besides acidifying vacuoles, the VMA protein can also be important for fungal filamentation, an important virulence feature in C. albicans. Can the presence of an intein in the VMA protein modulate its function in the intein-containing Candida species, interfering in their filamentation capacity? The ThrRS protein is essential for protein synthesis in cell; the splicing inefficiency of its intein would prevent cell proliferation and maintenance. This protein is inhibited by some drugs and the presence of an intein in some species would add another way to target it, by inhibiting its intein splicing. The GOGAT protein, coding by GLT1 gene, on the other hand, is not considered so essential because it is part of one out of three possible pathways to synthetize glutamate, however, since this pathway seems to be largely used in some Candida species, the GLT1 intein could also constitute an important therapeutic target for those non-albicans Candida species that contain it.

In order to address the aforementioned questions many experimental researches must be done, clarifying the actual role of inteins in fungal pathogens and possibly opening new prospects for antifungal drugs researches. The use of inteins as a new drug target is, clearly, limited to the species in which they are present in at least one protein, while their absence/presence should also be explored as a molecular marker. The merit of this discussion can be extended for other pathogenic fungi, besides Candida spp., that contain inteins in housekeeping genes, and may open a new study field in medical mycology concerning invasive genetic elements as tools for drug screening and diagnosis.

Author Contributions

JF, TP, and RT conceived, designed, did the literature review, provided and wrote the manuscript. JF carried out the search for inteins in Candida genomes and the RSCU analysis. TA, MC, and JG reviewed the taxonomy and epidemiology of Candida species. TA, MC, JG, and EB assisted in the preparation, final review, and co-wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by fellowships and grants provided by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq/Universal 475525/2013-2), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (PROPESQ-NUPLAM) and Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP Grants 2012/04003-1, 2012/07741-3).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01585

References

- Alcoba-flórez J., Méndez-álvarez S., Guarro J., Pérez-roth E., Arévalo P., Cano J., et al. (2005). Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Candida nivariensis sp. nov., a possible new opportunistic fungus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 4107–4111. 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D., Diamandis E. P., Greub G., Poutanen S. M., Christensen J. J., Kostrzew M. (2013). Use of MALDI-TOF for diagnosis of microbial infections. Clin. Chem. 59 1435–1441. 10.1373/clinchem.2013.204644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetti M., Merelli M., Ansaldi F., De Florentiis D., Sartor A., Scarparo C., et al. (2015). Clinical and therapeutic aspects of candidemia: a five year single centre study. PLoS ONE 10:e0127534 10.1371/journal.pone.0127534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastidas R. J., Heitman J. (2009). Trimorphic stepping stones pave the way to fungal virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 351–352. 10.1073/pnas.0811994106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M., Bonocora R. P. (2014). Homing endonucleases: from genetic anomalies to programmable genomic clippers. Methods Mol. Biol. 1123 1–26. 10.1007/978-1-62703-968-0_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop J. A., Chase N., Magill S. S., Kurtzman C. P., Fiandaca M. J., Merz W. G. (2008). Candida bracarensis detected among isolates of Candida glabrata by peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization: susceptibility data and documentation of presumed infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 443–446. 10.1128/JCM.01986-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S., Van Dijck P., Datta A. (2007). Environmental sensing and signal transduction pathways regulating morphopathogenic determinants of Candida albicans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71 348–376. 10.1128/MMBR.00009-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borman A. M., Linton C. J., Oliver D., Palmer M. D., Szekely A., Odds F. C., et al. (2009). Pyrosequencing analysis of 20 nucleotides of internal transcribed spacer 2 discriminates Candida parapsilosis, Candida metapsilosis, and Candida orthopsilosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 2307–2310. 10.1128/JCM.00240-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla M., Adamo G. M., Frascotti G., Porro D., Branduardi P. (2016). Physiological effects of GLT1 modulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains growing on different nitrogen sources. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26 326–336. 10.4014/jmb.1508.08002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt A., Koufopanou V. (2004). Homing endonuclease genes: the rise and fall and rise again of a selfish element. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14 609–615. 10.1016/j.gde.2004.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. I., Goodwin T. J. D., Poulter R. T. M. (2001). A nuclear-encoded intein in the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Yeast 18 1365–1370. 10.1002/yea.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. I., Gray J., Goodwin T. J. D., Poulter R. T. M. (2006). The distribution and evolutionary history of the PRP8 intein. BMC Evol. Biol. 6:42 10.1186/1471-2148-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. I., Poulter R. T. M. (2005). The PRP8 inteins in Cryptococcus are a source of phylogenetic and epidemiological information. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42 452–463. 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong S., Shao Y., Paulus H., Benner J., Perler F. B., Xu M. (1996). Protein splicing involving the Saccharomyces cerevisiae VMA intein. J. Biol. Chem. 271 22159–22168. 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland A. A., Farley M. M., Harrison L. H., Stein B., Hollick R., Lockhart S. R., et al. (2012). Changes in incidence and antifungal drug resistance in candidemia: results from population-based laboratory surveillance in Atlanta and Baltimore, 2008-2011. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55 1352–1361. 10.1093/cid/cis697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland A. A., Harrison L. H., Farley M. M., Hollick R., Stein B., Chiller T. M., et al. (2015). Declining incidence of candidemia and the shifting epidemiology of Candida resistance in two US metropolitan areas, 2008–2013: results from population-based surveillance. PLoS ONE 10:e0120452 10.1371/journal.pone.0120452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo A. L., Guimarães T., Camargo L. F. A., Richtmann R., de Queiroz-Telles F., Salles M. J. C., et al. (2013). Brazilian guidelines for the management of candidiasis – a joint meeting report of three medical societies: Sociedade Brasileira de Infectologia, Sociedade Paulista de Infectologia and Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 17 283–312. 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia A., Sampaio P., James S., Pais C. (2006). Candida bracarensis sp. nov., a novel anamorphic yeast species phenotypically similar to Candida glabrata. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56 313–317. 10.1099/ijs.0.64076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carolis E., Vella A., Vaccaro L., Torelli R., Posteraro P., Ricciardi W., et al. (2014). Development and validation of an in-house database for matrix assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry-based yeast Identification using a fast protein extraction procedure. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52 1453–1458. 10.1128/JCM.03355-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnos-Ollivier M., Ragon M., Robert V., Raoux D., Gantier J. C., Dromer F. (2008). Debaryomyces hansenii (Candida famata), a rare human fungal pathogen often misidentified as Pichia guilliermondii (Candida guilliermondii). J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 3237–3242. 10.1128/JCM.01451-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diezmann S., Cox C. J., Scho G., Vilgalys R. J., Mitchell T. G. (2004). Phylogeny and evolution of medical species of Candida and related taxa: a multigenic analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42 5624–5635. 10.1128/JCM.42.12.5624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahami S., Kordbacheh P., Moazeni M., Mahmoodi M., Mirhendi H. (2010). Species identification and strain typing of Candida isolates by PCR-RFLP and RAPD-PCR analysis for determining the probable sources of nosocomial infections. Iranian Red Crescent Med. J. 12 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. V., Prado C. G., Carvalho R. R., Dias K. S. T., Dias A. L. T. (2013). Candida albicans and Non-C. albicans Candida species: comparison of biofilm production and metabolic activity in biofilms, and putative virulence properties of isolates from hospital environments and infections. Mycopathologia 175 265–272. 10.1007/s11046-013-9638-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filetici P., Martegani M. P., Valenzuela L., González A., Ballario P. (1996). Sequence of the GLT1 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals the domain structure of yeast glutamate synthase. Yeast 12 1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldón T., Martin T., Marcet-Houben M., Durrens P., Bolotin-Fukuhara M., Lespinet O., et al. (2013). Comparative genomics of emerging pathogens in the Candida glabrata clade. BMC Genomics 14:623 10.1186/1471-2164-14-623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gacser A., Schafer W., Nosanchuk J. S., Salomon S., Nosanchuk J. D. (2007). Virulence of Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in reconstituted human tissue models. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44 1336–1341. 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K., Paul S., Sood P., Rudramurthy S. M., Rajbanshi A., Jillwin T. J., et al. (2015). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-fight mass spectrometry for the rapid identification of yeasts causing bloodstream infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 21 372–378. 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimble F. S., Thorner J. (1992). Homing of a DNA endonuclease gene by meiotic gene conversion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 357 301–306. 10.1038/357301a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M. R., Burt A. (1999). Recurrent invasion and extinction of a selfish gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 13880–13885. 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogarten J. P., Hilario E. (2006). Inteins, introns, and homing endonucleases: recent revelations about the life cycle of parasitic genetic elements. BMC Evol. Biol. 6:94 10.1186/1471-2148-6-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin T. J. D., Butler M. I., Poulter R. T. M. (2006). Multiple, non-allelic, intein-coding sequences in eukaryotic RNA polymerase genes. BMC Biol. 4:38 10.1186/1741-7007-4-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbuz M., Kaleli I. (2010). Molecular analysis of Candida albicans isolates from clinical specimens. Mycopathologia 169 261–267. 10.1007/s11046-009-9263-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays C., Duhamel C., Cattoir V., Bonhomme J. (2011). Rapid and accurate identification of species belonging to the Candida parapsilosis complex by real-time PCR and melting curve analysis. J. Med. Microbiol. 60 477–480. 10.1099/jmm.0.026633-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi C. M., Takashina F. H., Zendrini D., Stipp-abe A. T., Vespero E. C., Mariuza R. (2015). Comparison of Vitek-2 automated identification system and PCR-ITS for species characterization of clinical isolates. Semina 36 233–242. 10.5433/1679-0367.2015v36n1Suplp233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata R., Ohsumi Y., Nakano A., Kawasaki H., Suzuki K., Anraku Y. (1990). Molecular structure of a gene, VMA1, encoding the catalytic subunit of H(+)-translocating adenosine triphosphatase from vacuolar membranes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 265 6726–6733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. R., Collings A., Farnden K. J., Shepherd M. G. (1989). Ammonium assimilation by Candida albicans and other yeasts: evidence for activity of glutamate synthase. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135 1423–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalidas S., Cestari I., Monnerat S., Li Q., Regmi S., Hasle N., et al. (2014). Genetic validation of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases as drug targets in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 13 504–516. 10.1128/EC.00017-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karahan Z., Güriz H., Agirbasli H., Balaban N., Gocmen J. S., Aysev D., et al. (2004). Genotype distribution of Candida albicans isolates by 25S intron analysis with regard to invasiveness. Mycoses 47 465–469. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.01022.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi M., Nishio M., Saitoh K., Miyaki T., Oki T., Kawaguchi H. (1989). Cispentacin, A new antifungal antibiotic I. Production, isolation, physico-chemical properties and structure. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 42 1749–1755. 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koufopanou V., Burt A. (2005). Degeneration and domestication of a selfish gene in yeast: molecular evolution versus site-directed mutagenesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 1535–1538. 10.1093/molbev/msi149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koufopanou V., Goddard M. R., Burt A. (2002). Adaptation for horizontal transfer in a homing endonuclease. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19 239–246. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman C. P. (2003). Phylogenetic circumscription of Saccharomyces, Kluyveromyces and other members of the Saccharomycetaceae, and the proposal of the new genera Lachancea, Nakaseomyces, Naumovia, Vanderwaltozyma and Zygotorulaspora. FEMS Yeast Res. 4 233–245. 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00175-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachance M. A., Starmer W. T., Rosa C. A., Bowles J. M., Barker J. S., Janzen D. H. (2001). Biogeography of the yeasts of ephemeral flowers and their insects. FEMS Yeast Res. 1 1–8. 10.1016/S1567-1356(00)00003-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunes L., Rello J. (2016). Invasive candidiasis: from mycobiome to infection, therapy, and prevention. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35 1221–1226. 10.1007/s10096-016-2658-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasker B. A., Butler G., Lott T. J. (2006). Molecular genotyping of Candida parapsilosis group I clinical isolates by analysis of polymorphic microsatellite markers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44 750–759. 10.1128/JCM.44.3.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le S. Q., Gascuel O. (2008). An improved general amino acid replacement matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25 1307–1320. 10.1093/molbev/msn067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipe D. D., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2004). STAND, a class of P-Loop NTPases including animal and plant regulators of programmed cell death: multiple, complex domain architectures, unusual phyletic patterns, and evolution by horizontal gene transfer. J. Mol. Biol. 343 1–28. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Q. (2000). Protein-splicing intein: genetic mobility, origin, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34 61–76. 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Q., Hu Z. (1997). A DnaB intein in Rhodothermus marinus: indication of recent intein homing across remotely related organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 7851–7856. 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Q., Yang J. (2004). Prp8 intein in fungal pathogens: target for potential antifungal drugs. FEBS Lett. 572 46–50. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo H. J., Köhler J. R., Didomenico B., Loebenberg D., Cacciapuoti A., Fink G. R. (1997). Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90 939–949. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80358-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart S. R., Iqbal N., Cleveland A. A., Farley M. M., Harrison L. H., Bolden C. B., et al. (2012). Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies in two U.S. cities from 2008 to 2011. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50 3435–3442. 10.1128/JCM.01283-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart S. R., Messer S. A., Pfaller M. A., Diekema D. J. (2008). Geographic distribution and antifungal susceptibility of the newly described species Candida orthopsilosis and Candida metapsilosis in comparison to the closely related species Candida parapsilosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46 2659–2664. 10.1128/JCM.00803-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Martinez R. (2010). Candidosis, a new challenge. Clin. Dermatol. 28 178–184. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzluf G. A. (1997). Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61 17–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubon D., Garnaud C., Calandra T., Sanglard D., Cornet M. (2014). Resistance of Candida spp. to antifungal drugs in the ICU: where are we now? Intensive Care Med. 40 1241–1255. 10.1007/s00134-014-3404-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merseguel K., Nishikaku A., Rodrigues A., Padovan A., Ferreira R., de Azevedo Melo A. S., et al. (2015). Genetic diversity of medically important and emerging Candida species causing invasive infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 15:57 10.1186/s12879-015-0793-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miletti K. E., Leibowitz M. J. (2000). Pentamidine inhibition of group I intron splicing in Candida albicans correlates with growth inhibition. Antimicrob. Agents Chem. 44 958–966. 10.1128/AAC.44.4.958-966.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miraula M., Enculescu C., Schenk G., Mitić N. (2015). Applications of splicing-promoting proteins. Am. J. Mol. Biol. 5 42–56. 10.4236/ajmb.2015.52005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mita P., Boeke J. D. (2016). How retrotransposons shape genome regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 37 90–100. 10.1016/j.gde.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki K., Shirai Y., Tomaru Y., Nishida K., Pietrokovski S. (2005). Algal viruses with distinct intraspecies host specificities include identical intein elements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 3599–3607. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3599-3607.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase T. (1971). New species resembling of yeasts Candida krusei (cast.) Berkhout. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 398 383–398. 10.2323/jgam.17.383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakase T., Suzuki M., Takashima M., Miyakawa Y., Kagaya K., Fukazawa Y., et al. (1994). Candida sojae, a new species of yeast isolated from an extraction process of water soluble substances of defatted soubean flakes. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 40 161–169. 10.2323/jgam.40.161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N., Perzov N., Cohen A., Hagai K., Padler V., Nelson H. (2000). The cellular biology of proton-motive force generation by V-ATPases. J. Exp. Biol. 203 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova O., Jayachandran P., Kelley D. S., Morton Z., Merwin S., Topilina N. I., et al. (2015). Intein clustering suggests functional importance in different domains of life. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 783–799. 10.1093/molbev/msv271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova O., Topilina N., Belfort M. (2014). Enigmatic distribution, evolution, and function of Inteins. J. Biol. Chem. 289 14490–14497. 10.1074/jbc.R114.548255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nucci M., Queiroz-Telles F., Tobón A. M., Restrepo A., Colombo A. L. (2010). Epidemiology of opportunistic fungal infections in Latin America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51 561–570. 10.1086/655683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner U. A., Sun X., Jarvis T., Critchley I., Janjic N. (2007). Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: essential and still promising targets for new anti-infective agents. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drug 16 573–593. 10.1517/13543784.16.5.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue P., Luthey-Schulten Z. (2003). On the evolution of structure in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67 550–573. 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda Y., Sasaki D., Nogami S., Kaneko Y., Ohya Y., Anraku Y. (2003). Occurrence, horizontal transfer and degeneration of VDE intein family in Saccharomycete yeasts. Yeast 20 563–573. 10.1002/yea.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramythiotou E., Frantzeskaki F., Flevari A., Armaganidis A., Dimopoulos G. (2014). Invasive fungal infections in the ICU: how to approach, how to treat. Molecules 19 1085–1119. 10.3390/molecules19011085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus H. (2003). Inteins as targets for potential antimycobacterial drugs. Front. Biosci. 1:1157–1165. 10.2741/1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus H. (2007). Protein splicing inhibitors as a new class of antimycobacterial agents. Drugs Fut. 32 973–984. 10.1358/dof.2007.032.11.1140690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perler F. B. (2002). InBase: the intein database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 383–384. 10.1093/nar/30.1.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perler F. B. (2005). Protein splicing mechanisms and applications. IUBMB Life 57 469–476. 10.1080/15216540500163343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Andes D. R., Diekema D. J., Horn D. L., Reboli A. C., Rotstein C., et al. (2014). Epidemiology and outcomes of invasive candidiasis due to non-albicans species of Candida in 2,496 patients: data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) registry 2004–2008. PLoS ONE 9:e101510 10.1371/journal.pone.0101510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Chaturvedi V., Diekema D. J., Ghannoum M. A., Holliday N. M., Killian S. B., et al. (2012). Comparison of the sensititre YeastOne colorimetric antifungal panel with CLSI microdilution for antifungal susceptibility testing of the echinocandins against Candida spp., using new clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73 365–368. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Diekema D. J. (2007). Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20 133–163. 10.1128/CMR.00029-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posey K. L., Koufopanou V., Burt A., Gimble F. S. (2004). Evolution of divergent DNA recognition specificities in VDE homing endonucleases from two yeast species. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 3947–3956. 10.1093/nar/gkh734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter R. T. M., Goodwin T. J. D., Butler M. I. (2007). The nuclear-encoded inteins of fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44 153–179. 10.1016/j.fgb.2006.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prandini T. H. R., Theodoro R. C., Bruder-Nascimento A. C. M. O., Scheel C. M., Bagagli E. (2013). Analysis of inteins in the Candida parapsilosis complex for simple and accurate species identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51 2830–2836. 10.1128/JCM.00981-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryszcz L. P., Németh T., Gácser A., Gabaldón T. (2014). Genome comparison of Candida orthopsilosis clinical strains reveals the existence of hybrids between two distinct subspecies. Genome Biol. Evol. 6 1069–1078. 10.1093/gbe/evu082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryszcz L. P., Németh T., Saus E., Ksiezopolska E., Hegedűsová E., Nosek J., et al. (2015). The genomic aftermath of hybridization in the opportunistic pathogen Candida metapsilosis. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005626 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiles-Melero I., García-Rodríguez J., Gómez-López A., Mingorance J. (2012). Evaluation of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry for identification of Candida parapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis and C. metapsilosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31 67–71. 10.1007/s10096-011-1277-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandra S., Linde J., Brock M., Guthke R., Hube B., Brunke S. (2014). Regulatory networks controlling nitrogen sensing and uptake in Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 9:e92734 10.1371/journal.pone.0092734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M., Lass-Flörl C. (2008). Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14 5–24. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan S.-Y., Chien J.-Y., Hou Y.-C., Hsueh P.-R. (2010). Catheter-related fungemia caused by Candida intermedia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14 147–149. 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai S., Holland L. M., McGee C. F., Lynch D. B., Butler G. (2011). Evolution of mating within the Candida parapsilosis species group. Eukaryot. Cell 10 578–587. 10.1128/EC.00276-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]