Abstract

Objective To explore how patients and physicians describe attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared decision making.

Background Studies have described physician behaviours in shared decision making, explored decision aids for informing patients and queried whether patients and physicians want to share decisions. Little attention has been paid to patients’ behaviors that facilitate shared decision making or to the influence of patients and physicians on each other during this process.

Methods Qualitative analysis of data from four research work groups, each composed of patients with chronic conditions and primary care physicians.

Results Eighty‐five patients and physicians identified six categories of paired physician/patient themes, including act in a relational way; explore/express patient’s feelings and preferences; discuss information and options; seek information, support and advice; share control and negotiate a decision; and patients act on their own behalf and physicians act on behalf of the patient. Similar attitudes and behaviours were described for both patients and physicians. Participants described a dynamic process in which patients and physicians influence each other throughout shared decision making.

Conclusions This study is unique in that clinicians and patients collaboratively defined and described attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared decision making and expand previous descriptions, particularly of patient attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared decision making. Study participants described relational, contextual and affective behaviours and attitudes for both patients and physicians, and explicitly discussed sharing control and negotiation. The complementary, interactive behaviours described in the themes for both patients and physicians illustrate mutual influence of patients and physicians on each other.

Keywords: collaboration, communication, mutual influence, physician–patient relationship, qualitative research, shared decision making

Introduction

Health‐care leaders and policy planners internationally have placed a priority on physicians and patients learning to make health‐care decisions together. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 In response, research and opinion papers have proliferated. Researchers have examined behaviours of physicians that facilitate patients’ involvement in clinical settings, 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 determined whether shared decision making happens in clinical settings 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 and studied whether physicians and patients really want to share decisions. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 A great deal of research also has been devoted to developing and testing decision aids designed to inform patients about medical information they need to participate in decisions. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 Descriptions of physician behaviours in this research literature reveal some commonalities, especially regarding cognitive processes involved in shared decision making. Researchers have described ‘stages’ physicians can progress through, and behaviours or ‘competencies’ they can execute to involve patients in decision making. These behaviours focus on the physician’s role in sharing information (e.g. problem definition, presenting options with risks and benefits), eliciting patients’ values and preferences (for format and amount of information, and role in making decisions) and agreeing on or deferring a decision. 8 , 35 , 36

Despite the proliferation of literature, important questions remain. There is no common definition of shared decision making, and many studies do not specify the definition or framework used in the research. 35 , 37 There has been little research about how physicians integrate insight about patients’ life contexts, emotions and preferences into their own thinking about decisions, or about how physicians and patients reach mutual agreement through dialogue, how they manage conflict and the impact of resolving disagreements.

Patients’ perspectives on shared decision making are generally limited to studies about whether decisions were shared, 38 , 39 what behaviours they want in their physicians, 40 how sharing decisions affects their satisfaction 13 , 41 and whether or not they want to share decisions with their physicians. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 42 When asked which physician behaviours they associate with involvement in decision making, patients generally focus on the degree to which physicians convey respect for patients as persons, build understanding of their life context and listen to and consider patients’ contributions. 43 , 44 Patients seem to emphasize physicians’ attitudes and behaviours that extend beyond sharing information, eliciting patients’ values and preferences, and agreeing on or deferring a decision. 45

The literature about patients’ roles in decisions covers predominantly how they become informed and which decision aids are most effective in providing useful information. 31 , 32 , 33 , 46 While some studies have examined the general impact of patients’ and parents’ communication skills on their interactions with physicians, 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 few have examined the specific impact of patient communication skills on shared decisions. 52 , 53 We found only two research reports of either physicians’ or patients’ perspectives about which patient behaviours constitute shared decision making, beyond asking questions and becoming informed. 8 , 43 Relatively, little research has explored what patients do to encourage or elicit shared decision‐making behaviours in their physicians, how patients and physicians influence one another during an encounter that involves a decision that could be shared, how either physicians or patients can be motivated to engage in shared decision making or what patient and physician behaviours occur when shared decision making goes well. 54 , 55 Might patients play an active role in shaping physicians’ approaches to a decision, just as physicians may play a role in shaping the degree of patient involvement in a decision? Might both persons change their minds in the course of a decision, or might both persons begin without a clear decision in mind, and shape a decision that neither could have conceptualized alone?

Barriers to shared decision making have been identified during discussions of the topic in conversation and the literature. 6 , 56 , 57 Physicians worry about lack of time, whether or how to engage patients who do not seem interested and whether their patients really want to share in making decisions. Still, in the complex health‐care environment of the 21st century, leaders agree that we all must learn to make health‐care decisions together. There are some studies that indicate that it is possible to teach physicians to engage in the behaviours of sharing decisions; 18 , 38 , 58 , 59 the limited evidence available suggests this is true for patients as well. 52 , 53 Given current recommendations to enable patients to exercise the degree of control they choose over health‐care decisions, we need to understand which behaviours to teach to both groups, particularly patients.

In summary, three gaps emerge in this literature on shared decisions. First, what is the patients’ role (beyond becoming informed) in a decision shared with a physician? Second, how do patients and physicians influence each other during encounters in which they try to share decisions? Third, what can both parties do to facilitate shared decisions?

In this study, we sought to add to current understanding by exploring both patients’ and physicians’ perspectives about attitudes and behaviours in the patient–physician encounter when shared decision making goes well. This question guided the study: How do groups of patients and physicians working together describe patient and physician attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared medical decision making?

Methods

The research protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, MA, USA, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA, USA and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, MD, USA.

The study goal, to describe both patients’ and physicians’ behaviours that facilitate shared decision making, guided all aspects of our study design. Using Charles’ definition as a theoretical foundation, we sought to understand shared decision making as an interactive process. 10 Therefore, we chose a qualitative research design in which patients and physicians would together discuss their own attitudes and behaviours and those of the other person. One of the authors (JLH) had experience involving patients and families in collaborative work groups to develop medical education curricula. 60 , 61 We adapted this process for the study reported here.

As we aimed to learn about patient and physician behaviours and attitudes in successful shared decision making, we used the principles of appreciative inquiry and asked participants to discuss examples and share stories of their own experiences in which shared decision making went well. 62 Sharing their stories helped participants identify specific attitudes and behaviours they had experienced in actual situations. We recruited research participants (experienced physicians, patients with chronic health conditions) who had experience making health‐care decisions in situations where there were treatment choices.

Study participants

Patients and physicians were recruited to participate as expert ‘key informants’, 63 with approximately equal numbers of patients and physicians in each of four 3‐h sessions. Physicians affiliated with hospital‐based departments of primary care were recruited if they were ≥3 years post‐residency and expressed interest in patient–doctor communication. Primary care physicians referred patients to the study who had experienced multiple health‐care interactions, expressed interest in patient–doctor communication and agreed to be contacted. Participants were not in a group with their own physician or patient. 85 patients and physicians participated in the four research work groups, 50 women (58%) and 35 men (42%). Their ages ranged from 34 to 79. There were 41 physicians, 20 women (49%) and 21 men (51%). Physicians were affiliated with community, HMO, Veteran’s Administration, or other hospital‐based practices. 75% of physicians worked in medical school‐affiliated practices. There were 44 patients, 29 women (68%) and 15 men (32%). Patients had a variety of chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, congestive heart failure, liver transplant and chronic leukaemia.

Group process

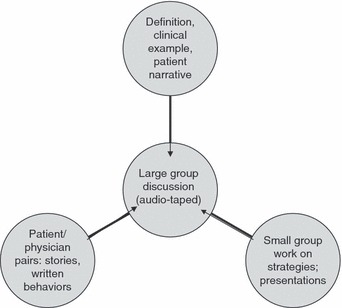

Two physicians (BAL and WDC) and two educators (JLH and AW, noted in Acknowledgements) facilitated the research work groups, one physician and one educator leading each group. Three of the groups took place in Massachusetts, the fourth during a national meeting of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare in MD. Each research work group began with a definition and brief description of shared decision making to establish a common language. Shared decision making was described as the interaction between patients and physicians when both parties wish to participate in making a decision about health‐care tests or treatments, and in which both physician and patient are involved in the process, both share information and express preferences, and both agree about the decision plans. 10 One researcher then shared a clinical example of shared decision making and a patient narrative, 64 followed by large‐group discussion of aspects of shared decision making illustrated by these examples. In patient/physician pairs or trios, participants discussed specific positive examples of shared decision making from their own experiences. 62 , 65 Each participant wrote down the facilitative attitudes and behaviours of the patients and physicians in the examples described. In the large group, participants then shared the attitudes and behaviours they had identified, working together with the researchers to group them as preliminary themes and suggest a label for each emerging theme. Finally, participants worked in small groups to develop communication strategies to implement these themes and presented these strategies to the large group. All large‐group discussions were audio‐taped and transcribed. This process is summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Group process for data collection

| Step no. | Group process steps | Rationale | Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Two researchers facilitated each group session | A physician and an educator contributed to the facilitation of each group | |

| 2 | Both patients and physicians interacted and participated throughout the group process | Patient and physician perspectives were represented throughout and informed the development of thought and comments | |

| 3 | One researcher (BL) presented a definition of shared decision making 10 | The definition of shared decision making was explained and components posted on the wall to establish shared language within the groups | |

| 4 | One researcher (BL) shared a clinical example of shared decision making and read a patient narrative | Stories in which shared decision making occurred provided clear examples and further established a shared language | |

| 5 | Each large group discussed the examples | Participants identified components of shared decision making they heard in the examples and discussed their reactions | Audiotapes and transcripts of large‐group discussions |

| 6 | In patient–physician pairs or trios, participants shared and discussed specific positive examples of shared decision making from their own experiences | Asking participants to identify positive examples of shared decision making from their own experience as physicians or patients provided material from which they could draw detailed descriptions of behaviours and attitudes that had facilitated successful sharing of decisions | Written descriptions of behaviours and attitudes of patients and physicians who had engaged in successful shared decision making |

| 7 | Participants shared the attitudes and behaviours they had identified with the large group, working together with the researchers to group them as preliminary themes and suggest a label for each emerging theme | Research participants participated in initial interpretation and data analysis by assisting with development of preliminary themes and providing comments that explained their rationale | The written descriptions of behaviours and attitudes of patients and physicians (from step 6) were grouped in categories. Audiotape transcripts of the discussion of these behaviours and attitudes provided additional data |

| 8 | Participants each chose one emerging theme, worked in small groups to develop communication strategies to implement these themes, and presented these strategies to the large group | Small groups provided an opportunity for participants to work in depth with a few behaviours and/or attitudes that facilitate shared decision making among patients or physicians or both. Presentations to the large group provided more detailed explanations of participants’ insights | Audiotape transcriptions of small group presentations and comments from the larger group |

Figure 1.

Research work group process.

Data analysis process

The data included descriptions of patient and physician behaviours and attitudes written by participants, transcripts of audiotapes from large‐group discussions and reports of small group work on communication strategies. Researchers assured thematic saturation by checking with participants during each research work group about whether all concepts and preliminary themes were represented, and by reviewing and incorporating themes across all research work groups. Researchers analysed the data using the constant comparative method and grounded theory techniques. 66 , 67

After the four work groups, all four group facilitators met to identify themes in the descriptions of patient and physician behaviours and attitudes written by participants during the work groups. Two researchers (BAL and JLH) reviewed the preliminary themes, revised wording, and grouped them within broader categories. The four research team members used this list of patient and physician themes to code data from two to four research work groups. Working in pairs, researchers reviewed and discussed the data and themes until they reached consensus that the attitudes and behaviours for shared decision making contained within the written data were adequately described (Table 1, data collected in steps 6, 7). This resulted in 26 behaviours and attitudes for physicians and 17 behaviours and attitudes for patients.

Two researchers (BAL and JLH) then analysed the audiotape transcripts and renamed and regrouped the attitudes and behaviours within the categories (Table 1, data collected in steps 5, 7, 8) to better describe the data. The patient and physician themes remained the same after analysis of the transcripts, with two exceptions. First, an additional patient theme ‘negotiates/agrees to disagree’ was clearly described in the transcripts and added to the list of patient behaviours. Second, ‘listens and’ was added to the first two physician behaviours under PH2: explores patient’s feelings, preferences and information about self. The final list of 26 physician behaviours and attitudes and 18 patient behaviours and attitudes are represented in the bulleted points in Table 2.

Table 2.

Attitudes and behaviours that enhance shared decision making

| Patient themes | Physician themes |

|---|---|

| PT1 – acts in a relational way • Seeks a personal connection with the physician • Trusts the physician • Demonstrates respect and consideration or empathy for the physician | PH1 – acts in a relational way • Uses non‐verbal behaviours to connect with the patient • Is personal (shares interests, humour, feelings) while being professional • Stays in connection over the long term • Doesn’t rush. Takes time during the clinical encounter or afterwards (includes follow‐up) • Trusts the patient to be truthful • Expresses empathy, compassion, and/or caring • Respects the person without passing judgement (includes intelligence, culture, psychosocial context, and style) |

| PT2 – understands and expresses feelings, preferences and information about self • Is aware of feelings and expresses them • Recognizes and expresses personal priorities and preferences. (Includes needs, preferences regarding participation, preferences about care.) • Considers family (and significant other) needs when making choices • Describes symptoms and their personal significance • Answers questions honestly | PH2 – explores patient’s feelings, preferences and information about self • Listens and explores patient’s personal information, thoughts and feelings (includes fears and concerns) • Listens and explores patient’s needs and preferences • Acknowledges and conveys respect for patient’s information, needs, preferences (includes goals), and feelings. (Includes patient’s expertise about his/her body. Includes patients’ explanation of his/her illness) |

| PT3 – discusses information and options • Is willing to listen and be open to ideas from the physician. (Includes considering options.) • Asks questions. (Includes seeking information from the physician.) • Shares understanding of information with the physician • Explains thinking process. (Includes transparency and honesty) | PH3 – discusses information and options • Provides medical information; elicits questions, and adjusts information‐giving to the patient’s needs and preferences • Bases information shared on recent literature • Presents options, including risks and benefits • Is honest about limits of physician’s knowledge and scientific information • Is willing to listen and be open to ideas from the patient, family and friends • Presents his/her opinion |

| PT4 – seeks information, support and advice • Gathers support from family, friends or others • Gathers information from sources other than this physician | PH4 – seeks information, support and advice • Demonstrates willingness to seek and/or seeks additional information and encourages the patient to do the same (includes complementary therapies) • Acknowledges or seeks and respects the expertise of other professionals • Physician seeks personal support |

| PT 5 – shares control/negotiates a decision • Advocates for self within the relationship. (Includes standing up for oneself, challenging the physician, or making the ultimate decision.) • Accepts risk or uncertainty • Negotiates/agrees to disagree | PH5 – shares control/negotiates a decision • Acknowledges areas of agreement and disagreement • Validates patient self‐advocacy and autonomy, or acknowledges that power is shared (includes sometimes deferring to patient’s wishes) • Integrates patient’s feelings and preferences into a mutual decision • Negotiates agreeable decisions and choices • Includes patient’s family or friends in discussion • Accepts risk or uncertainty |

| PT6 – acts on behalf of oneself • Takes responsibility for acting on agreed upon plans | PH6 – acts on behalf of the patient • Advocates for the patient (includes willingness to circumvent or adapt the system) |

Using the themes as organized in Table 2, these two researchers coded each transcript independently and then together to reach agreement that the data in the transcripts were accurately represented by the revised themes. Finally, a third researcher (WDC) independently reviewed the coded audio‐transcripts. Researchers discussed discrepancies and disagreements and revised the coding until they reached consensus about the coding of all data and agreed that all attitudes and behaviours were accurately described and represented within themes.

This data analysis process accomplished open coding (identifying individual themes in the data, ensuring that all important concepts are represented) and axial coding (identifying relationships between themes), in this case grouping the themes in six categories and noting that patient and physician attitudes and behaviours fell into very similar categories (the six categories placed side by side in Table 2). The final step of the analysis involved comparing the parallel patient and physician themes and examining transcript quotes to understand relationships between them. 67

Results

Table 2 presents six categories of patient and physician themes and a complete list of corresponding attitudes and behaviours described by participants and derived from the data. We have presented the themes in pairs, with attitudes and behaviours of patients and physicians grouped in categories that mirror each other or occur in response to each other.

Patient and physician: acts in a relational way

Participants described both patients and physicians who facilitate shared decision making as actively seeking a personal connection with each other. Both patients and physicians trust, respect and offer empathy to one another, actively engaging in building a relationship that makes shared decision making possible. Patient participants discussed the need for trust in order to share concerns that influence decision making. One patient said, ‘…[It helps] having an open and candid dialogue and relationship so that pretty much anything can be discussed…If you have the trust, then you find that you are…more willing to put those things out on the table’. Another said, ‘This…really does require a really kind of intimate attachment between the patient and the doctor…’. Participants described relationship as a mutual responsibility. For example, one patient explained, ‘I create relationships with healthcare providers that are around things besides my health. It’s sort of a great equalizer in some way…’. A physician participant highlighted the importance of the physician’s effort to act in a relational way by saying, ‘…Express caring in that interaction – this is what the physician can do. And the quality of that caring is what enhances the intrinsic motivation of the patient to take the responsibility’. Participants also described the importance of finding a way to spend the necessary time and stay in connection over time, while acknowledging that time constraints make this challenging.

Patient: understands and expresses feelings, preferences, and information about self Physician: explores patients’ feelings, preferences, and information about self

Participants recognized the importance of the patient’s ability to understand and articulate his or her feelings, preferences, priorities and needs. This may involve preparation and openness on the part of the patient. As one patient said in response to a story, ‘(The) patient was emotionally available. She was in touch with some emotions she was having when the physician in the story gave an indication that they were receptive. She let the flow take place. She shared herself’. Participants also noted the physician’s role in exploring the patient’s thoughts, feelings and fears and in helping to clarify preferences and needs. For example, a physician noted, ‘Without being able to say, “What is it that you’re most afraid of?” nothing else would have happened in that conversation’. Another said, ‘…[I]t has to do with giving her voice by asking the question, she was able to actually access for herself, what perhaps she couldn’t say before’. They acknowledged that patients may find it difficult to understand and express feelings and values. As one patient said, ‘Sometimes those fears are not accessible to patients because they’re too dark and too threatening and they have to be willing to share them to the physician. And that is also complex because it involves a physician and how much they can be trusted to be shared with that information’.

Patient and physician: discusses information and options

Discussing information was important for both patients and physicians. For patients, this meant asking questions, listening to the physician, considering options and sharing one’s understanding and thinking process. As one physician expressed, ‘[Y]ou don’t understand something, you ask again. You know what, “I don’t understand the sensitivity and specificity stuff. Put it into different words”. You’re going through and letting people know it, rather than just nodding your head’. For physicians, this meant providing current information, risks and benefits, eliciting questions and adjusting information to patients’ needs, being honest about the limits of the physician’s and scientific knowledge, and presenting an opinion. For example, a patient noted, ‘[I]t’s extremely important that there is a language that is understandable by the patient…And that the physician takes time out to get feedback. “Did you really understand what just was communicated?”…Sometimes information can be given in too large a dose, even though it may be clear’. Participants discussed the challenge of this process for the physician who might find it difficult to interpret and present technically difficult information in a balanced fashion without leaving the patient bewildered.

Patient and physician: seeks information, support and advice

Participants acknowledged the importance of seeking information from sources outside the physician–patient relationship. They described both patients and physicians as active seekers of support and advice from family, loved ones, friends and trusted colleagues. A patient said, ‘[M]y strategy really is to take a friend to listen with me because I don’t always hear what I really should, what the person said. I may hear what I thought they said and that person can strike a balance for me and put things in some objective perspective’. Another patient said, ‘I mean, it’s very useful to talk to non‐doctors about a dilemma because they don’t see it in an occupationally routinized way. I think it’s going outside of medicine to bring things to the medical encounter – literature, religion’.

Patient and physician: shares control/negotiates a decision

Shared decision making involves both persons acknowledging areas of agreement and disagreement, validating a patient’s self‐advocacy and negotiating. Participants described the physician as sometimes guiding the process of shared decision making, and the patient as sometimes needing to stand up for him‐ or herself and make the decision.

Participants described decision making as a dynamic process in which control was at times shared, at other times shifted to one or another person. Either the physician or the patient may assume, defer or share control in decision making. One patient said, ‘We sort of realized that there’s a meta‐process that has to occur first, which is the physician and the patient have to agree about how the decision is going to get made. Some patients will want the physician basically to lead them and say, “This is what you should do”. And other patients basically would have the physician explain the alternatives to them. So the first step actually is to come together and create a decision about how the process will be implemented’. One physician said, ‘It’s the shifting of control, too. I mean, in him giving her control, then she handed it over [to him]. And it’s a dynamic that in any interaction goes back and forth’.

The physician sharing decision making acknowledges that power is shared and integrates the patient’s preferences into a mutual decision. Participants acknowledged that it is not always possible to reach agreement and validated the importance of deferring to the patient’s wishes in this situation. As a patient said, ‘He allowed her to be the person to make the final decision. He said, “If you don’t want us to do this, we won’t”. She had the power’. A patient described maintaining a relationship despite disagreement said, ‘The patient was able to make an informed decision. Though it differed from the doctor’s, a respectful relationship was maintained’.

One patient described the physician’s role as fostering equality through deep inquiry: ‘I think he went beyond listening and really he was inquiring. And, I think, by doing that he sort of empowered her and he empowered himself in her eyes [be]cause that inquiry presages some equality between them, and I think it made their communication so successful’. Participants described reaching a decision that neither may have conceptualized on their own. A patient explained one such scenario: ‘I think she felt the control in the beginning was ONLY to say no to the treatment, period. And then when he asked that question and she was able to respond to him, she discovered that the control could be to accept SOME of the treatment that she felt comfortable and safe with’.

Negotiation may occur within a single encounter, or a shared decision may take place over several visits. ‘Sometimes shared decision‐making doesn’t happen in one meeting, but happens over a long continuum and there may be areas of agreement and lack of agreement in the same relationship or consensus and lack of consensus. Sometimes agree to disagree’. Participants also noted the need for ongoing discussion because decisions may change over time. One patient described the give‐and‐take of negotiation and changing a decision in this way, ‘I’ve…[made] a decision that my doctor absolutely hated. And, I think, the best thing he did was actually expressed that. He said, “Today you are saying no. Can we agree to talk about it tomorrow?” And I said, “Well, we can agree to talk about it an hour from now, two hours from now, a day from now, but it’s not going to change my mind”. Well, surprisingly, I changed my mind’.

Patient: acts on behalf of self Physician: acts on behalf of the patient

Once a decision has been made, participants noticed that ultimate responsibility for implementing health decisions resides with patients. A patient stated, ‘[U]ltimate control of patients’ health decisions resides with the patient. These are strategies – be mindful of behavioural changes, [they’ve] got to be owned by the patient’. Physicians’ advocacy within (or around) the health‐care system helps patients implement jointly negotiated decisions. For example, a physician suggested, ‘[Y]ou can lay out, “Well these options exist, but your insurance…will prevent us from doing something”. But if we go out of the box and go at it a different way, another solution is possible. A willingness to circumvent system issues’.

Relationships among themes

The final step of the data analysis involved examining the relationships between the themes. Participants’ comments regarding four of the six categories of themes revealed mutual influence between patients and physicians (acts in a relational way; understands and expresses/explores patients’ feelings, preferences and information about self; discusses information and options; shares control and negotiates a decision). Comments regarding two categories of themes (seeks information, support and advice; acts on behalf of oneself/the patient) reflected moving outside of the patient–physician relationship and taking action to research, implement or support a decision. It also became clear when reading the transcripts that the themes did not reflect sequential stages, but rather continuous movement among all of the described attitudes and behaviours, with no one starting point for all encounters.

In summary, the participants described the facilitators of shared decision making as behaviours and attitudes ascribed to both physicians and patients. Both can make an effort to build their relationship, and relationships based on trust and respect provide the necessary context within which shared decision making can occur. The physician and patient influence each other throughout shared decision making. The patient may at times be able to understand and articulate information, feelings and preferences about him‐ or herself. At other times, the physician, through listening and deep inquiry, plays a role in helping the patient access and give voice to emotions and preferences that otherwise may not be clear. Each person discusses his or her understanding of information, and is open to ideas expressed by the other. Mutual influence is also reflected in adjustments of type and amount of information shared and language used to ensure clarity and common understanding. The physician may take the lead in sharing control, and at times, the patient may make the decision. Mutual influence is also reflected when patients or physicians hand control to the other, enable the other to participate in a decision or take control, integrate each others’ preferences into a mutually agreeable decision, or agree to disagree and honour the patient’s decision.

Discussion

The results of this study describe behaviours and attitudes for patients and physicians that facilitate shared decision making, in a framework that posits influence of both patients and physicians on each other throughout their interactions. Suchman has written about patient/physician encounters as non‐linear patterns of behaviour. 68 This study suggests such a complex, non‐linear process for shared decisions, in which the outcome of a shared decision cannot be predicted with certainty at the start of any one encounter. The behaviours and attitudes described by the patients and physicians provide neither prerequisites nor stages of a shared decision, but rather a repertoire of facilitators from which either person may draw to increase the likelihood that a shared decision will occur. As such, these findings suggest a more fluid and dynamic process than the concept of sequential steps or ‘stages’ described by others. 36

Mutual influence occurs throughout shared decision making: for example, in acts of deep inquiry, listening and response; when either person takes, cedes or shares control or facilitates the other person’s ability to do so; when physician or patient adjusts the information they share based on their level of trust or to meet needs and when emotions and preferences are integrated into a collaboratively constructed decision. Shared decision making, as described by participants in this study, is a dynamic process that occurs within the context of a relationship that includes trust and respect. This relationship may precede a decision or may develop while creating a shared decision. Physician and patient attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared decision making also help foster a relationship within which shared decision making can occur.

Earlier research about communication between patients and physicians indicates that patients can influence the communication behaviours of physicians. For example, active patient participation (e.g. asking questions, stating opinions, expressing concerns) has been shown to increase information‐sharing by physicians 47 , 48 and improve clinical outcomes. 52 , 53 Furthermore, active patient participation and physician partnership building (encouraging, supporting and accommodating patient involvement) predict each other. 49 , 50 , 51 The keys to more frequent occurrence of successful shared decision making may therefore lie equally in the hands of both patients and physicians.

Our six physician themes elaborate those described previously, particularly in relational, contextual and affective domains, and in the explicit discussion of sharing power and negotiation. For example, the physician theme ‘acts in a relational way’ includes aspects of the physician–patient relationship that go beyond developing a partnership around a decision, to include self‐expression, humour, expressing empathy and compassion, staying in connection, taking time, trusting the patient, adopting a non‐judgemental attitude towards the patient and respecting his or her intelligence, culture, circumstances and style. Some may argue that these attitudes and behaviours are not specific to shared decision making. Our analysis of the data suggests that they provide the context within which shared decision making can occur by building relationships that facilitate sharing control and responsibility.

A previous preliminary list of patient ‘competencies’ for shared decision making included defining a preferred patient–physician relationship, establishing partnership, articulating for oneself and communicating health problems, feelings, beliefs and expectations, accessing and evaluating information, negotiating decisions and agreeing on plans. 8 The attitudes and behaviours described in each of the patient themes reported here substantiate and expand this description, suggesting an active role for patients in shaping the relationship, sharing contextual information including the personal significance of symptoms, listening and discussing options with an open mind, bringing information to the discussion from outside sources, seeking support and taking responsibility to follow through on agreed‐upon decisions. Participants described how an individual patient’s desire for decisional responsibility is not necessarily fixed, but may vary between and even within consultations depending on contextual and clinical factors. They also described the patient’s role in sharing power, including challenging the physician, sometimes making the decision, and accepting associated risk or uncertainty.

There are several limitations to the present study. By design, bringing physicians and patients together in research work groups influenced the data collected. While the intent was to further discussion about interaction and to enable both physicians and patients to hear and respond to one another’s views, it is possible that either group would feel hesitant to speak openly in the presence of the other. The transcript data suggest, however, that the climate of the work groups permitted physicians and patients to build upon, agree or disagree with each other, and each group contributed comparable numbers of comments. Only primary‐care physicians participated in this study, and only patients with serious or chronic health conditions; and the patients included more women than men. The findings in this study, therefore, may not transfer to all patients and physicians in all settings. Furthermore, the participants in the study were all positively motivated towards shared decision making, as required by the goals of the study. Physicians and patients in general, however, may not wish to engage in shared decision making, depending on their personal and contextual factors, 69 they may not possess the communication skills needed to negotiate decisions 70 and they may operate in health‐care settings that make sharing decisions difficult. 7 , 22 , 26 , 57 , 68 , 71 , 72 Even given the rich description and numerous facilitators offered, the attitudes and behaviours described by patients and physicians reflecting on positive experiences and examples of shared decision making may not be enough to overcome an unwilling partner.

This study is, however, unique in that clinicians and patients defined and described attitudes and behaviours that facilitate shared decision making, using a process that both modelled and explored collaboration. Others have queried physicians or patients separately about proposed competencies for informed shared decision making. 6 , 8 , 36 In this study, both physicians and patients contributed to the descriptions of all the themes describing both patient and physician attitudes and behaviours. The contribution of mutual influence between patients and physicians was perhaps, therefore, more clearly elucidated than in previously reported studies. Future educational efforts may apply the themes described here for teaching and assessing collaboration for both patients and physicians. Future research may explore in more detail how patients facilitate the shared decision‐making behaviours of their physicians, how physicians respond to patients’ influence and what conditions increase the likelihood that effective sharing of decisions will occur. The findings described here may further understanding and exploration of mutual influence and help both patients and physicians collaborate more effectively and share control and responsibility in decisions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Amy Wasserman MS who helped facilitate, and analyse and code data. Dr Lown thanks Charles J. Hatem MD for his mentorship and support. Dr Hanson thanks Patrick O’Malley MD MPH, Jeffrey Jackson MD and Terrence Tice ThD PhD for their support and suggestions during preparation of the manuscript.

Salary support for Beth A. Lown MD was provided by a fellowship from the Carl J. Shapiro Institute of Education and Research (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School). The Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, Boston, MA, USA, provided support for participants’ expenses. The American Academy on Physician and Patient (now the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare) provided support for facilitators’ expenses. Janice L. Hanson’s work on this study was supported in part by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. The funders did not participate in the design, conduct of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense, the U.S. government, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Mount Auburn Hospital, the Carl J. Shapiro Institute of Education and Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation, or the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare.

References

- 1. Committee on Quality Healthcare in America, Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The President’s Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in the Health Care Industry . Participation in Treatment Decisions In: Consumer Bill of Rights and Responsibilities. Washington DC, 1997. Available at: http://www.hcqualitycommission.gov/cborr/chap4.html, accessed on 22 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. House of Commons Health Committee. Patient and public involvement in the NHS . Third report of session 2006‐07. Vol. 1. House of Commons. London, 2007. Available at: http://www.parliament.the‐stationery‐office.co.uk/pa/cm200607/cmselect/cmhealth/278/278i.pdf, accessed on 22 October 2008.

- 4. Farrell C. Patient and public involvement in health: the evidence for policy implementation. A summary of the results of the health in partnership research programme. London: Department of Health, 2004. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4082334.pdf, accessed on 22 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gafni CC, Whelan T. Decision‐making in the physican–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision‐making model. Social Science and Medicine, 1999; 49: 651–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Gwyn R, Grol R. Towards a feasible model for shared decision‐making: focus group study with general practice registrars. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 753–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Gandek B, Rogers WH, Ware JE Jr. Characteristics of physicians with participatory decision‐making styles. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1996; 124: 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Towle A, Godolphin W. Framework for teaching and learning informed shared decision‐making. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 766–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scare for measuring patient involvement. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2003; 12: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 44: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charles CA, Whelan T, Gafni A, Willan A, Farrell S. Shared treatment decision making: what does it mean to physicians? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2003; 21: 932–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charles C, Whelan T, Gafni A. What do we mean by partnership in making decisions about treatment? British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 780–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goossensen A, Zijlstra P, Koopmanschap M. Measuring shared decision making processes in psychiatry: skills versus patient satisfaction. Patient Education and Counseling, 2007; 67: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hindley C, Thomson AM. The rhetoric of informed choice: perspectives from midwives on intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring. Health Expectations, 2005; 8: 306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McGuire AL, McCullough LB, Weller SC, Whitney SN. Missed expectations? Physicians’ views of patients’ participation in medical decision‐making. Medical Care, 2005; 43: 466–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Flynn N, Britten N. Does the achievement of medical identity limit the ability of primary care practitioners to be patient‐centred? A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 60: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seaburn DB, Morse D, McDaniel SH, Beckman H, Silberman J, Epstein R. Physician responses to ambiguous patient symptoms. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2004; 20: 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Towle A, Godolphin W, Grams G, Lamarre A. Putting informed and shared decision making into practice. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kremer H, Ironson G, Schneiderman N, Hautzinger M. ‘It’s my body’: does patient involvement in decision making reduce decisional conflict? Medical Decision Making, 2007; 27: 522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swenson SL, Buell S, Zettler P, White M, Ruston DC, Lo B. Patient‐centered communication: do patients really prefer it? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2004; 19: 1069–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benbassat J, Pilpel D, Tidhar M. Patients’ preferences for participation in clinical decision‐making: a review of published surveys. Behavioral Medicine, 1998; 24: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deber RB, Kraerschmer N, Irvine J. What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision‐making. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1996; 156: 1414–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stevenson FA. General practitioners’ views on shared decision making: a qualitative analysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 2002; 50: 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edwards A, Elwyn G. Involving patients in decision making and communicating risk: a longitudinal evaluation of doctors’ attitudes and confidence during a randomized trial. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 2004; 10: 431–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McKeown RE, Reininger BM, Martin M, Hoppmann RA. Shared decision making: views of first‐year residents and clinic patients. Academic Medicine, 2002; 77: 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2005; 20: 531–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caress AL, Beaver K, Luker K, Campbell M, Woodcock A. Involvement in treatment decisions: what do adults with asthma want and what do they get? Results of a cross sectional survey Thorax, 2005; 60: 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosen P, Anell A, Hjortsberg C. Patient views on choice and participation in primary health care. Health Policy, 2001; 55: 121–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKinstry B. Do patients wish to be involved in decision making in the consultation? A cross sectional survey with video vignettes. British Medical Journal, 2000; 321: 867–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamann J, Neuner B, Kasper J et al. Participation preferences of patients with acute and chronic conditions. Health Expectations, 2007; 10: 358–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systemic review. British Medical Journal, 1999; 319: 731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wills CE, Holmes‐Rovner M. Patient comprehension of information for shared treatment decision making: state of the art and future directions. Patient Education and Counseling, 2002; 50: 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sepucha KR, Mulley AG. Extending decision support: preparation and implementation. Patient Education and Counseling, 2003; 50: 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Graham ID, Logan J, O’Connor A et al. A qualitative study of physicians’ perceptions of three decision aids. Patient Education and Counseling, 2003; 50: 279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 60: 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. British Journal of General Practice, 2000; 50: 892–897. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moumjid N, Gafni A, Bremond A, Carrere MO. Shared decision making in the medical encounter: are we all talking about the same thing? Medical Decision Making, 2007; 27: 539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K et al. Long‐term effects of a shared decision‐making intervention on physician–patient interaction and outcome in fibromyalgia. A qualitative and quantitative 1 year follow‐up of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 63: 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Hasenburg A. Concordance between patients’ desired and actual decision‐making roles in breast cancer care. Psychooncology, 2007; 17: 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B. Clinical decision‐making: patients’ preferences and experiences. Patient Education and Counseling, 2007; 65: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Swanson KA, Bastani R, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Ford DE. Effect of mental health care and shared decision making on patient satisfaction in a community sample of patients with depression. Medical Care Research and Review, 2007; 64: 416–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hanson JL. Shared decision‐making: have we missed the obvious? Archives of Internal Medicine, 2008; 168: 1368–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Edwards A, Elwyn G, Smith C, Williams S, Thornton H. Consumers’ views of quality in the consultation and their relevance to ‘shared decision‐making’ approaches. Health Expectations, 2001; 4: 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Entwistle V, Prior M, Skea ZC, Francis JJ. Involvement in treatment decision‐making: its meaning to people with diabetes and implications for conceptualisation. Social Science and Medicine, 2008; 66: 362–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Entwistle VA, Watt IS. Patient involvement in treatment decision‐making: the case for a broader conceptual framework. Patient Education and Counseling, 2006; 63: 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Waljee JF, Rogers MA, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2007; 25: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Street RL. Information‐giving in medical consultations: the influence of patients’ communicative styles and personal characteristics. Social Science and Medicine, 1991; 32: 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cegala DJ, McClure L, Marinelli TM, Post DM. The effects of communication skills training on patients’ participation during medical interviews. Patient Education and Counseling, 2000; 41: 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Street RL, Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Haidet P. Beliefs about control in the physician–patient relationship. Effect on communication in medical encounters. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2003; 18: 609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Street RL. Communicative styles and adaptations in physician–parent consultations. Social Science and Medicine, 1992; 34: 1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Street RL, Gordon HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations. Why some patients are more involved than others. Medical Care, 2005; 43: 960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1985; 102: 520–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1988; 3: 448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Patient–doctor decision‐making about treatment within the consultation – a critical analysis of models. Social Science and Medicine, 2006; 62: 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Mowle S et al. Measuring the involvement of patients in shared decision‐making: a systematic review of instruments. Patient Education and Counseling, 2001; 43: 5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gravel K, Legare F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision‐making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Implementation Science, 2006; 1: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Elwyn G, Gwyn R, Edwards A, Grol R. Is ‘shared decison‐making’ feasible in consultations for upper respiratory tract infections? Assessing the influence of antibiotic expectations using discourse analysis. Health Expectations, 1999; 2: 105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bieber C, Muller KG, Blumenstiel K et al. A shared decision‐making communication training program for physicians treating fibromyalgia patients: effects of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 2008; 64: 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Elwyn G, Edwards A, Hood K et al. Achieving involvement: process outcomes from a cluster randomized trial of shared decision making skill development and use of risk communication aids in general practice. Family Practice, 2004; 21: 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hanson JL, Randall VF. Advancing a partnership: patients, families, and medical educators. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 2007; 19: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hanson JL, Randall VF. Patients as Advisors: Enhancing Medical Education Curricula. Bethesda, MD: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cooperrider DL, Sorensen PJ Jr, Whitney D, Yaeger TF. Appreciative Inquiry. Rethinking Human Organization Toward a Positive Theory of Change. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing LLC, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. London: Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 64. McCollum S. Between Yes and No. Narratives: American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. Available at: http://www.aachonline.org/membership/patientexperiences/, accessed on 22 October 2008.

- 65. Watkins JM, Mohr BJ. Appreciative Inquiry: Change at the Speed of Imagination. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass/Pfeiffer, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine Publishing Company, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship‐centered care. Complex responsive processes of relating. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2006; 21 (Suppl. 1): S40–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cooper LA, Beach MC, Johnson RL, Inui TS. Delving below the surface. Understanding how race and ethnicity influence relationships in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2006; 21: S21–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui TS. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 1997; 227: 350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barry CA, Barber N, Bradley CP. Misunderstanding in prescribing decisions in general practice: qualitative study. British Medical Journal, 2000; 320: 484–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Guadagnoli E, Ward P. Patient participation in decision‐making. Social Science and Medicine, 1998; 47: 329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]