This study analyzed the activity of sunitinib in a relatively large and homogenous international cohort of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma in terms of outcome and comparison with a matched cohort of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinomas. Sunitinib therapy may be associated with outcome and toxicities similar to those seen with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. The Heng risk and pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio may be associated with progression-free survival and overall survival.

Keywords: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, Chromophobe type, Clear cell type, Outcome, Sunitinib

Abstract

Background.

Sunitinib is a standard treatment for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC). Data on its activity in the rare variant of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (mchRCC), are limited. We aimed to analyze the activity of sunitinib in a relatively large and homogenous international cohort of mchRCC patients in terms of outcome and comparison with mccRCC.

Methods.

Records from mchRCC patients treated with first-line sunitinib in 10 centers across 4 countries were retrospectively reviewed. Univariate and multivariate analyses of association between clinicopathologic factors and outcome were performed. Subsequently, mchRCC patients were individually matched to mccRCC patients. We compared the clinical benefit rate, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) between the groups.

Results.

Between 2004 and 2014, 36 patients (median age, 64 years; 47% male) with mchRCC were treated with first-line sunitinib. Seventy-eight percent achieved a clinical benefit (partial response + stable disease). Median PFS and OS were 10 and 26 months, respectively. Factors associated with PFS were the Heng risk (hazard ratio [HR], 3.3; p = .03) and pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) >3 (HR, 0.63; p = .02). Factors associated with OS were the Heng risk (HR, 4.1; p = .04), liver metastases (HR, 3.8; p = .03), and pretreatment NLR <3 (HR, 0.55; p = .03). Treatment outcome was not significantly different between mchRCC patients and individually matched mccRCC patients. In mccRCC patients (p value versus mchRCC), 72% achieved a clinical benefit (p = .4) and median PFS and OS were 9 (p = .6) and 25 (p = .7) months, respectively.

Conclusion.

In metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, sunitinib therapy may be associated with similar outcome and toxicities as in metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. The Heng risk and pretreatment NLR may be associated with PFS and OS.

Implications for Practice:

Data on the activity of sunitinib in metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (mchRCC) are limited. This study analyzed the activity of sunitinib in a cohort of mchRCC patients. Of 36 patients with mchRCC who were treated with first-line sunitinib, 78% achieved a clinical benefit. Median PFS and OS were 10 and 26 months, respectively. Treatment outcome was not significantly different between mchRCC patients and individually matched metastatic clear cell RCC patients.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common cancer of the kidney [1]. Metastatic disease is diagnosed in 20%–30% of patients, and 70%–80% of patients present with localized or locally advanced disease at diagnosis, which is potentially curable by radical surgical resection alone [2]. Among patients who undergo radical resection for localized disease, future metastatic disease develops in 20%–40% [3].

Renal cell carcinoma is a heterogeneous disease in terms of histological subtypes. The most common subtype (80%) is clear cell. Less common, non-clear cell subtypes include papillary type 1, papillary type 2, chromophobe (5%), and other rarer subtypes [4].

An understanding of the pathogenesis of renal cell carcinoma at the molecular level and randomized clinical trials have established the standard role of the orally administered vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor inhibitor sunitinib for the treatment of advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma [5].

Data on the activity of sunitinib therapy in the rare variant of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma are limited by the lack of prospective controlled phase III studies dedicated to this histological variant [6]. Published data include relatively small or heterogeneous (combined analysis of mixed histology with papillary type, or mixed targeted therapies) studies [6–8].

In the present study we sought to analyze the activity of sunitinib in a relatively large and homogenous international cohort of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (mchRCC) in terms of outcome and comparison with a matched cohort of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (mccRCC).

Materials and Methods

Study Group

We reviewed the records of patients (unselected cohort, international multicenter database) with evidence of metastatic renal cell carcinoma who were treated with first-line sunitinib between February 1, 2004, and December 31, 2014, in 10 centers across 4 countries: the United States (Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD), Israel (Institutes of Oncology at Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba; Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, Zerifin; Rambam Medical Center, Haifa; Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer; Soroka Medical Center, Beer-Sheva; Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva; Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv), South Korea (Department of Oncology, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Asan Medical Center, Seoul), and Turkey (Department of Medical Oncology, Ataturk Training and Research Hospital, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Izmir).

Patients with chromophobe-type metastatic renal cell carcinoma were identified and individually matched by clinicopathologic factors to patients with clear cell type metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Patient data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records and paper charts, including the following baseline clinical characteristics and known prognostic factors [8–14]: age; gender; pretreatment smoking status (active versus past/never); past nephrectomy; the time interval from initial diagnosis to sunitinib treatment initiation; number of metastasis sites; presence of lung, liver, or bone metastases; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; hemoglobin level, corrected (for albumin); calcium level; pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR); and two postbaseline clinical characteristics: sunitinib-induced hypertension and sunitinib dose reduction or treatment interruption. Data on the concomitant use of medications, including angiotensin system inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers) was gathered from patients' electronic medical records and paper charts, from pharmacy records, and by contacting patients and other treating physicians as needed. Outcome data were last updated on December 31, 2014, including clinical benefit, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Patients who did not progress or die by December 31, 2014, were censored in progression-free survival analysis or overall survival analysis, respectively.

Sunitinib Treatment

All patients had objective disease progression on scans before starting sunitinib treatment (required as an entry criterion). Sunitinib was administered orally, usually at a starting dose of 50 mg once daily, in 6-week cycles consisting of 4 weeks of treatment followed by 2 weeks without treatment. On-treatment dose reduction or treatment interruption was done for the management of adverse events, depending on their type and severity, according to standard guidelines. Treatment was continued until evidence of disease progression on scans, unacceptable adverse events, or death. Patient follow-up generally consisted of regular physical examinations and laboratory assessments (hematologic and serum chemical measurements), every 4–6 weeks, and imaging studies were performed every 12–18 weeks.

Treatment Outcomes

For the evaluation of response, the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors, version 1.1, were applied [15]. In patients with only bone metastases, only complete response, stable disease, or progressive disease was noted; partial response was not noted [15]. The response was assessed by treating physicians (while the patients were receiving treatment in each center, as part of standard patient follow-up). Clinical benefit was determined for each patient as a binary variable indicating whether stable disease or better was achieved.

Progression-free survival was defined as the time from the initiation of sunitinib treatment until evidence of disease progression on scans or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the time from the initiation of sunitinib treatment to death from any cause.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed retrospectively. Patients with chromophobe and clear cell histology subtypes were individually matched by the following discrete variables: gender, prior nephrectomy, sunitinib-induced hypertension, sunitinib dose reduction/treatment interruption, the use of angiotensin system inhibitors, Heng risk, and pretreatment NLR. Patients were also individually matched by age (age of a patient with clear cell histology was chosen as the age of a patient with chromophobe histology ±5 years).

The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for nominal data and two-sample t test (or Mann-Whitney nonparametric test) for continuous measures, each when appropriate, were used to compare, between chromophobe and clear cell histology subtypes, clinicopathologic characteristics and clinical benefit rate (partial response + stable disease; odds ratio (OR) for clear cell versus chromophobe subtypes). In all tests, a two-tailed p value of <.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Cox proportional hazards or logistic regression models were used for comparison of progression-free survival and overall survival between the two groups.

Furthermore, to determine whether histologic subtype is independently associated with treatment outcome, a univariate analysis (unadjusted) of association between each clinicopathologic factor and clinical outcome was performed for the entire patient cohort (comprising both histology subtypes), using logistic regression for response rate and Cox regression model for survival outcomes (progression-free survival and overall survival). Factors with significant association in the univariate analysis were included in multivariable logistic or Cox proportional hazards regression models (using forward selection) to determine their independent effects. Once the base model was determined for each endpoint, the “treatment variable” (mccRCC vs. mchRCC) was added to the base models to obtain adjusted treatment group odds ratios or hazard ratios.

Progression-free survival and overall survival times (probability and median) were estimated from a Kaplan-Meier curve. Data were analyzed by using SPSS software, version 21 (IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY, http://www.ibm.com/us-en).

Regulatory Considerations

The research was carried out in accordance with the approval by the institutional review board committee of our institutions.

Results

Patient Characteristics

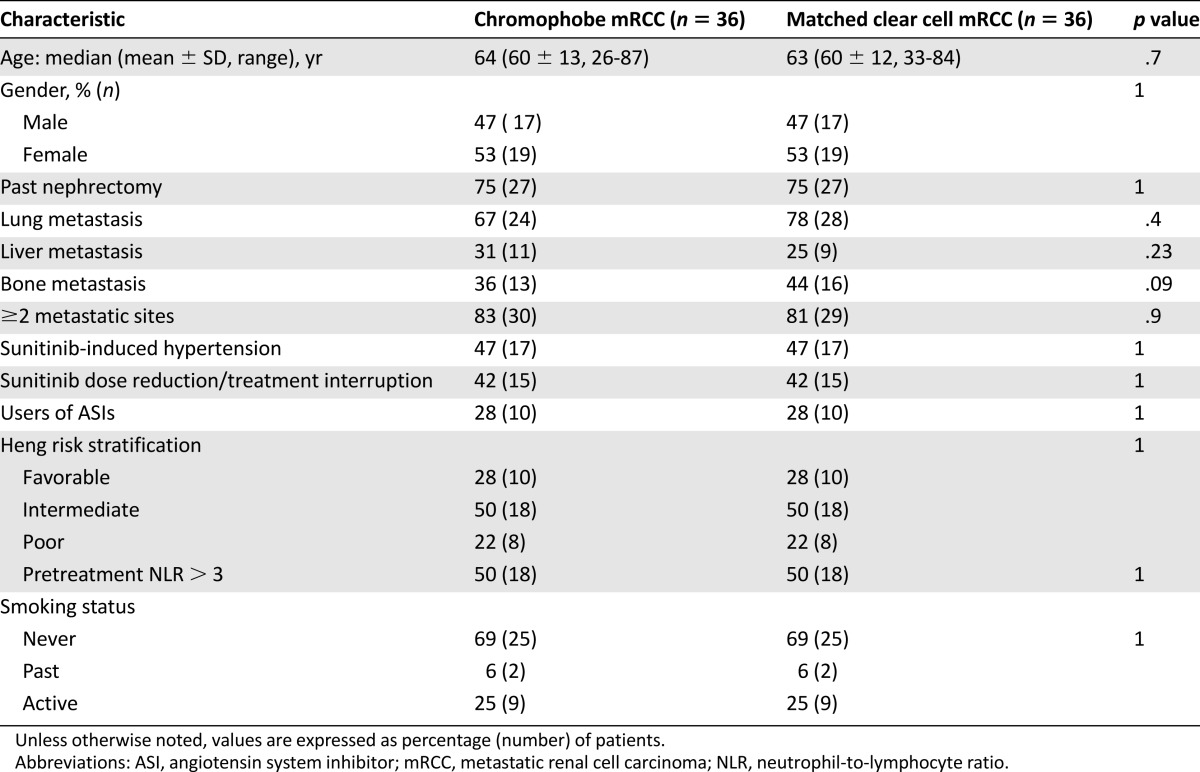

Between February 1, 2004, and December 31, 2014, 36 patients with metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma treated with first-line sunitinib were individually matched to patients with clear cell histology. The distribution of clinicopathologic and prognostic factors is shown in Table 1. The groups were matched regarding the following clinicopathologic factors: age, gender, prior nephrectomy, sunitinib-induced hypertension, sunitinib dose reduction/treatment interruption, the use of angiotensin system inhibitors, Heng risk, pretreatment NLR, and smoking status. They were balanced with regard to the presence of two or more metastatic sites and lung, liver, or bone metastasis.

Table 1.

Distribution of clinicopathologic and prognostic factors, stratified by histology

Sunitinib Treatment Outcomes

In the entire patient cohort (n = 72), best objective response was complete response in 1% (n = 1), partial response in 32% (n = 23), stable disease in 42% (n = 30), and progressive disease (within the first 3 months of therapy) in 25% (n = 18). Median progression-free survival was 9.5 months (mean ± SD, 14 ± 8 months [range, 1–51 months]). Median overall survival was 26 months (29 ± 11 months [range, 1–75] months).

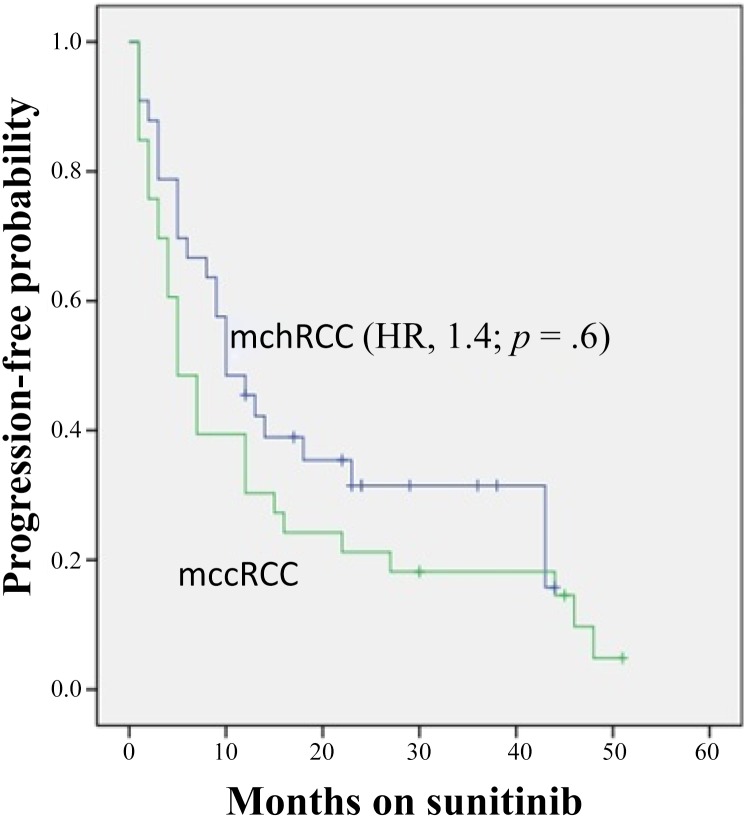

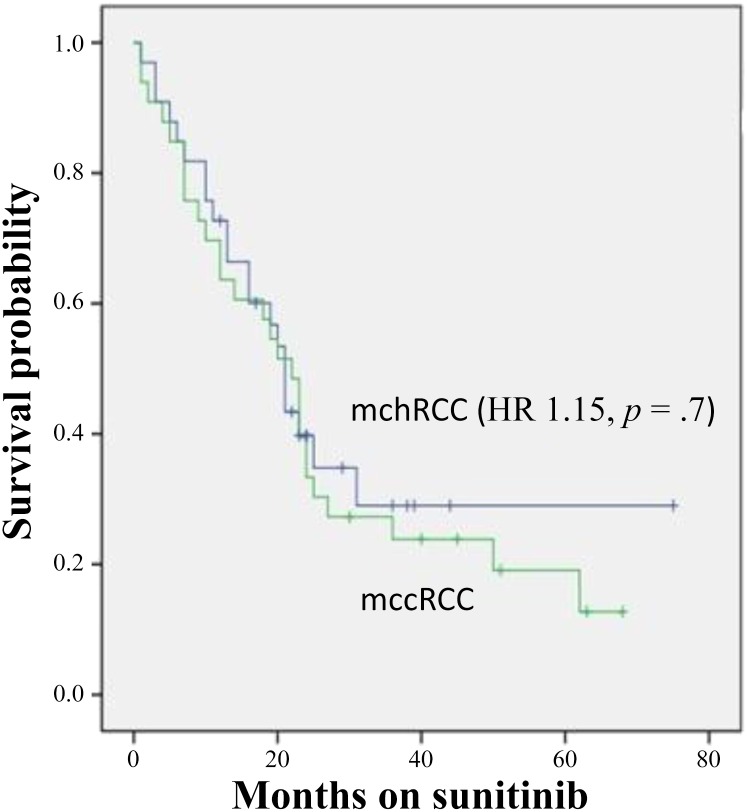

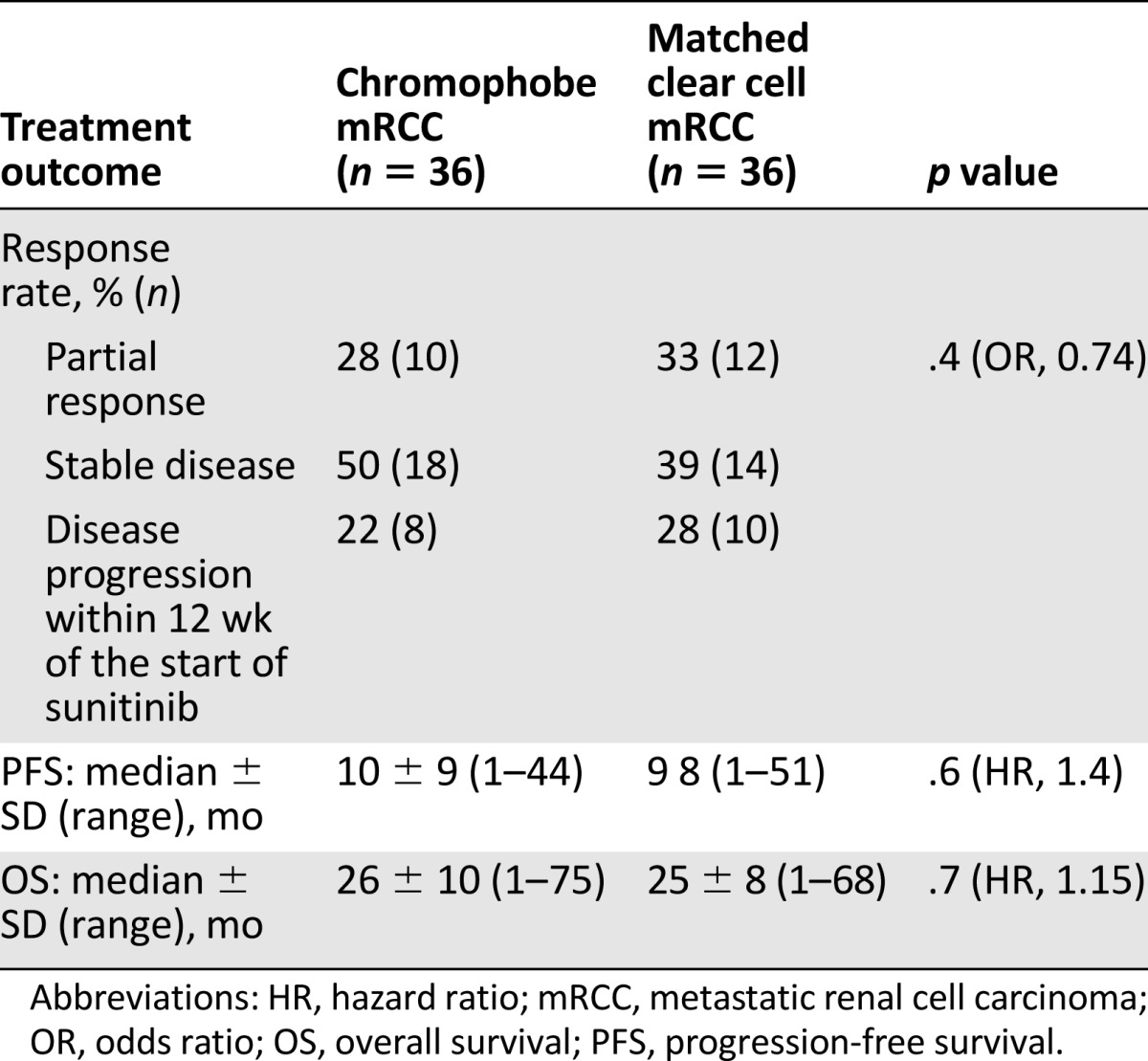

In patients with chromophobe versus clear cell histology, clinical benefit (partial response + stable disease) was 78% (n = 28) versus 72% (n = 26), whereas 22% (n = 8) versus 28% (n = 10) had disease progression within the first 3 months of therapy (p = .4; odds ratio, 0.74). Median progression-free survival (Fig. 1) was 10 versus 9 months (hazard ratio [HR], 1.4; p = .6). Median overall survival (Fig. 2) was 26 versus 25 months (HR, 1.15; p = .7) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival stratified by histology.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mccRCC, metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma; mchRCC, metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival stratified by histology.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mccRCC, metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma; mchRCC, metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma.

Table 2.

Sunitinib treatment outcome stratified by histology

Univariate Analysis (Entire Patient Cohort, n = 72) of Factors Associated With Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival

Smoking status (HR, 3.6; p < .0001 for active vs. never-smokers/past smokers), the Heng risk (HR, 1.3 and 4.1; p = .4 and p < .0001, for favorable and intermediate versus poor risk, respectively), past nephrectomy (HR, 0.39 for yes vs. no; p = .002), the use of angiotensin system inhibitors (HR, 0.48 for yes vs. no; p = .03), sunitinib-induced hypertension (HR, 0.43 for yes vs. no; p = .004), and pre–sunitinib treatment NLR > 3 (HR, 0.13 for ≤3 vs. >3; p < .0001) were individually associated with progression-free survival. Histology type (chromophobe vs. clear cell) was not associated with progression-free survival (HR, 0.71; p = .1).

Smoking status (HR, 3.29 for active vs. never-smokers/past smokers; p < .0001), the Heng risk (HR, 1.3 and 3.37 for poor vs. favorable and intermediate risk, respectively; p = .7 and <.0001), past nephrectomy (HR, 0.4 for yes vs. no; p = .003), the use of angiotensin system inhibitors (HR, 0.43 for yes vs. no; p = .018), sunitinib-induced hypertension (HR, 0.36 for yes vs. no; p = .001), presence of liver metastases (yes vs. no) (HR, 2.3; p = .015), sunitinib dose reduction or treatment interruption (HR, 0.52 for no vs. yes; p = .028), and pre–sunitinib treatment NLR > 3 (HR, 0.17 for ≤3 vs. >3; p < .0001) were individually associated with overall survival. Histology type (chromophobe vs. clear cell) was not associated with overall survival (HR, 0.9; p = .2).

Multivariate Analysis (Entire Patient Cohort, n = 72) of Factors Associated With Clinical Benefit, Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival

Factors independently associated with clinical benefit (adjusted odds ratio) were sunitinib-induced hypertension (OR, 2.7; p < .001), smoking status (OR, 3.4 for never-smoker/past smoker vs. active smoker; p = .02), and pretreatment NLR > 3 (OR, 3.9; p = .01 for ≤3 vs. >3). Factors independently associated with PFS (adjusted hazard ratios) were the use of angiotensin system inhibitors (HR, 0.3 for yes vs. no; p = .03) and pretreatment NLR >3 (HR, 0.6 for ≤3 vs. >3; p = .04). Factors independently associated with OS (adjusted hazard ratios) were the presence of liver metastases (yes vs. no) (HR, 2.7; p = .014), sunitinib dose reduction or treatment interruption (HR, 0.5 for no vs. yes; p = .008), and pre–sunitinib treatment NLR > 3 (HR, 0.2 for ≤3 vs. >3; p < .003).

In patients with chromophobe histology (n = 36), factors independently associated with PFS were the Heng risk (HR, 3.3; p = .03) and pretreatment NLR >3 (HR, 0.63; p = .02). Factors independently associated with OS were the Heng risk (HR, 4.1; p = .04), liver metastases (HR, 3.8; p = .03), and pretreatment NLR <3 (HR, 0.55; p = .03).

Discussion

The present study found that patients with metastatic chromophobe-type RCC may benefit from sunitinib therapy, with an outcome similar to that of patients with clear cell type histology, in terms of objective response, progression-free survival, and overall survival. Furthermore, in univariate and multivariate analyses of the entire patient cohort (chromophobe type plus clear cell type), the histologic type was not associated with treatment outcome, although statistical inference was limited because of sample size considerations.

Data on the activity of sunitinib therapy in the rare variant of metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma are limited by the lack of prospective controlled phase III studies dedicated to this histological variant [6]. Published data include relatively small or heterogeneous (combined analysis of mixed histology with papillary type, or mixed targeted therapies) studies [6, 7]. Chromophobe-type RCC has a relatively indolent course, uncommonly metastasizes, and may be associated with a better prognosis than clear cell–type RCC [16, 17]. Prolonged PFS and OS with sunitinib therapy may be explained by the indolent course of disease or the biologic effect of sunitinib, which is a VEGF and KIT inhibitor because VEGF and KIT overexpression have been reported in chromophobe RCC [16, 17].

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a multicenter retrospective study. We could not exclude the possibility that unequal distribution of unidentified clinicopathologic parameters in our patient cohort may have biased the observed results. Moreover, other clinicopathologic factors, including histologic type, that were not significantly associated with treatment outcome in the present study might have been important in a larger patient cohort. Nonetheless, the outcome of the mchRCC patient population in this study (i.e., a clinical benefit in most patients, median progression-free survival of 10 months, and median overall survival of 26 months) is similar to previously published data among patients with mchRCC treated with sunitinib [7, 16]. Second, mchRCC is a relatively rare disease. Thus, the total number of 72 patients is relatively small. As a result, our study was underpowered to show a difference in outcome. Third, whether our findings are specific to sunitinib or are generalizable to other tyrosine kinase inhibitors is not known.

Despite these limitations, our clinical observation that histologic status of chromophobe type does not affect the outcome of sunitinib treatment in metastatic renal cell carcinoma may contribute to treatment decisions, patient selection, and clinical trial design. According to a recent meta-analysis of systemic therapy in renal cell carcinoma, the outcomes tend to be significantly worse for non–clear cell type (vs. clear cell type), with lower response rate and shorter progression-free survival and overall survival [18]. In the present study, the outcome of sunitinib therapy in mchRCC is similar to that of mccRCC. Thus, a lower efficacy of targeted therapy may exist in metastatic nonchromophobe, non–clear cell RCC (e.g., papillary, sarcomatoid, undifferentiated). Further prospective studies may be warranted to test and confirm our hypothesis-generating observation in larger patient cohorts and to define the association between histologic type and outcome in different subgroups of patient (e.g., according to risk by prognostic models).

Conclusion

In metastatic chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, sunitinib therapy may be associated with outcome and toxicities similar to those seen with metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. The Heng risk and pretreatment NLR may be associated with PFS and OS.

Acknowledgments

Some of the data were presented (as a poster) at the Genitourinary Cancers Symposium of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Orlando, FL, February 2015, and published in abstract form (J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl 7):429a). The data were also presented (as a poster) at the 7th European Multidisciplinary Meeting on Urological Cancers, Barcelona, Spain, 2015, and published in abstract form (Eur Urol 2015;14(suppl 7):157a).

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Daniel Keizman, David Sarid, Maya Gottfried, Victoria Neiman, Eli Rosenbaum, Avivit Peer, Ibrahim Yildiz

Provision of study material or patients: Daniel Keizman, David Sarid, Avishay Sella, Maya Gottfried, Hans Hammers, Mario A. Eisenberger, Michael A. Carducci, Victoria Sinibaldi, Victoria Neiman, Eli Rosenbaum, Avivit Peer, Avivit Neumann, Wilmosh Mermershtain, Keren Rouvinov, Raanan Berger, Ibrahim Yildiz

Collection and/or assembly of data: Daniel Keizman, Jae L. Lee, Avishay Sella, Maya Gottfried, Mario A. Eisenberger, Michael A. Carducci, Victoria Sinibaldi, Victoria Neiman, Eli Rosenbaum, Avivit Peer, Avivit Neumann, Wilmosh Mermershtain, Keren Rouvinov, Raanan Berger, Ibrahim Yildiz

Data analysis and interpretation: Daniel Keizman, Eli Rosenbaum, Ibrahim Yildiz

Manuscript writing: Daniel Keizman, David Sarid, Avishay Sella, Maya Gottfried, Victoria Neiman, Eli Rosenbaum, Ibrahim Yildiz

Final approval of manuscript: Daniel Keizman, David Sarid, Jae L. Lee, Avishay Sella, Maya Gottfried, Hans Hammers, Mario A. Eisenberger, Michael A. Carducci, Victoria Sinibaldi, Victoria Neiman, Eli Rosenbaum, Avivit Peer, Avivit Neumann, Wilmosh Mermershtain, Keren Rouvinov, Raanan Berger, Ibrahim Yildiz

Disclosures

Avishay Sella: Pfizer, Novartis (C/A), Pfizer, Novartis (RF), Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline (H); Hans Hammers: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Exelixis (C/A), Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Li L, Kaelin WG., Jr New insights into the biology of renal cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25:667–686. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massari F, Bria E, Maines F, et al. Adjuvant treatment for resected renal cell carcinoma: are all strategies equally negative? Potential implications for trial design with targeted agents. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2013;11:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrmann E, Weishaupt C, Pöppelmann B, et al. New tools for assessing the individual risk of metastasis in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuter VE. The pathology of renal epithelial neoplasms. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:534–543. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Rahman O, Fouad M. Efficacy and toxicity of sunitinib for non clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC): A systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choueiri TK, Plantade A, Elson P, et al. Efficacy of sunitinib and sorafenib in metastatic papillary and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:127–131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patil S, Figlin RA, Hutson TE, et al. Prognostic factors for progression-free and overall survival with sunitinib targeted therapy and with cytokine as first-line therapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:295–300. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Bukowski RM, Figlin RA, et al. Prognostic nomogram for sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;113:1552–1558. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rini BI, Cohen DP, Lu DR, et al. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:763–773. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: Results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–5799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keizman D, Huang P, Eisenberger MA, et al. Angiotensin system inhibitors and outcome of sunitinib treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective examination. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1955–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keizman D, Ish-Shalom M, Huang P, et al. The association of pre-treatment neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio with response rate, progression free survival and overall survival of patients treated with sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keizman D, Gottfried M, Ish-Shalom M, et al. Active smoking may negatively affect response rate, progression-free survival, and overall survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. The Oncologist. 2013;19:51–60. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tannir NM, Plimack E, Ng C, et al. A phase 2 trial of sunitinib in patients with advanced non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2012;62:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin JM, Fisher RA, Pickering LM, et al. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with prolonged response to sequential sunitinib and everolimus. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e241–e242. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vera-Badillo FE, Templeton AJ, Duran I, et al. Systemic therapy for non-clear cell renal cell carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2015;67:740–749. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]