Abstract

PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial quality control (MQC) requires valosin-containing protein (VCP)-dependent Mitofusin/Marf degradation to prevent damaged organelles from fusing with the healthy mitochondrial pool, facilitating mitochondrial clearance by autophagy. Drosophila clueless (clu) was found to interact genetically with PINK1 and parkin to regulate mitochondrial clustering in germ cells. However, whether Clu acts in MQC has not been investigated. Here, we show that overexpression of Drosophila Clu complements PINK1, but not parkin, mutant muscles. Loss of clu leads to the recruitment of Parkin, VCP/p97, p62/Ref(2)P and Atg8a to depolarized swollen mitochondria. However, clearance of damaged mitochondria is impeded. This paradox is resolved by the findings that excessive mitochondrial fission or inhibition of fusion alleviates mitochondrial defects and impaired mitophagy caused by clu depletion. Furthermore, Clu is upstream of and binds to VCP in vivo and promotes VCP-dependent Marf degradation in vitro. Marf accumulates in whole muscle lysates of clu-deficient flies and is destabilized upon Clu overexpression. Thus, Clu is essential for mitochondrial homeostasis and functions in concert with Parkin and VCP for Marf degradation to promote damaged mitochondrial clearance.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common progressive neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by bradykinesia, rigidity, tremor and postural instability. Although most of the diagnosed PD cases are sporadic, mutations in several genes that cause familial forms have been identified, including Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), a-synuclein, parkin, PINK1 and DJ-1 (1,2).

PINK1, a mitochondrial serine–threonine protein kinase, and Parkin, a cytosolic E3 ubiquitin ligase, link mitochondrial health to PD (3–5). Healthy mitochondria, the powerhouse for most cellular events, are dynamic organelles that alter their morphology to maintain a balance between fusion and fission. Mitochondrial fusion in mammals is regulated by mitofusin 1 and 2 (Mfn 1/2), while the fission process is governed by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) (6). Delicately balanced fission and fusion events are essential for normal mitochondrial function and organ integrity (7–11). Genetic studies in Drosophila have shown that PINK1 acts upstream of Parkin to regulate cell death, mitochondrial integrity and function (12–14). Remarkably, multiple defects induced by loss of PINK1 or parkin function in Drosophila can be rescued by the downregulation of mitochondrial remodeling factors, including Marf, the fly homolog of human Mitofusin 1 and 2, or overexpression (OE) of Drp1 (15–17). The underlying molecular mechanism for this was unclear until other studies revealed that PINK1 and Parkin promote damaged mitochondrial clearance through interactions with the fusion/fission machinery (18–20).

Mitochondria that are damaged or senescent may lose their inner membrane potential, accumulate toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS), fuse with and contaminate other healthy mitochondria. PINK1 and Parkin are key factors in the efficient isolation and elimination of these poisonous mitochondria, a process called mitochondrial quality control (MQC) (21). Studies in mammalian cell culture show that mitochondrial damage and/or a collapse in membrane potential stabilizes PINK1 protein on the mitochondrial outer membrane and, in turn, phosphorylates Mfn (22,23). Phosphorylated Mfn, together with other mitochondrial proteins on the outer membrane, act as receptors to recruit cytoplasmic Parkin and serve as substrates for Parkin-dependent ubiquitination. Ubiquitinated Mfn is extracted from mitochondria by VCP/p97 for proteasomal degradation, while the entire mitochondria can be eliminated by autophagy (18,24,25). Indeed, loss of Mfn prevents damaged mitochondria from fusing with other healthy mitochondria (18,26). A number of observations also demonstrate that increased mitochondrial fission facilitates mitophagy, whereas reduced fission or elevated fusion compromises mitophagy (27–31). These results suggest that smaller mitochondria are eliminated by autophagy more readily than larger organelles (32). Mitophagy also occurs in distal neuronal axons. Interaction between the mitochondrial protein Miro and adaptor protein Milton mediates transport of mitochondria along microtubules (MTs). Damaged mitochondria can be halted by PINK1/Parkin-dependent Miro degradation and then displaced from the MTs, followed by local clearance by autophagy (33,34).

Clustered mitochondria (Clu) orthologs, Clu1 in yeast and clueless (clu) in Drosophila, were first characterized for their role in the prevention of mitochondrial clustering (35,36). Although Clu protein can be found in close vicinity to mitochondria, suggestive of a mitochondrial requirement, it is predominantly localized to puncta within the cytoplasm, suggesting that Clu may have alternative functions (35,37–40). Indeed, Clu forms a complex with aPKC/Baz/Par6 to regulate Drosophila larval neuroblast asymmetric division (41). Human CLUH may also be required for mitochondrial biogenesis by binding to the selective mRNA of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins and affecting protein levels encoded by these mRNAs (37,42,43). Our previous study shows that Clu interacts with the Drosophila Golgi reassembly stacking protein (dGRASP) to suppress ER stress and mediate the export of αPS2 integrin, but not βPS, from the perinuclear ER by maintaining the stability of Sec16 at ER exit sites, independent of its role in mitochondrial clustering (38). However, the precise mechanism by which Clu takes part in these processes is still not clear. clu mutant flies phenocopy parkin mutants, namely decreased levels of ATP, abnormal mitochondrial integrity and shorter lifespan (35,39,44,45). Further genetic studies show that clu interacts with PINK1 and parkin in regulating mitochondrial morphology in female germ cells. Clu protein normally binds PINK1 and physically interacts with Parkin upon mitochondrial depolarization, indicating that Clu may play a role in PD (35,40). However, whether Clu is involved in PINK1/Parkin-mediated MQC is unknown.

Here, we show that Clu is involved in Parkin-mediated mitophagy. In Drosophila muscle tissues, OE of Clu partially rescues the mitochondrial morphology defects in PINK1, but not parkin, mutant flies. Knockdown of clu in S2 cells impairs mitophagy by delaying VCP-mediated Marf degradation. Furthermore, Clu OE in flies promotes Marf degradation and knockdown of Marf alleviates impaired mitophagy resulting from loss of Clu. Taken together, our data suggest that Clu is involved in MQC and with VCP to regulate Marf degradation.

Results

Clu regulates mitochondrial morphology and Clu OE suppresses PINK1 mutants

Previous studies showed that mutations in either clu, parkin or pink1 result in mitochondrial clustering in Drosophila female germline cells (35,40). However, the large nuclei and a small amount of cytoplasm in these cells make it difficult to observe morphological changes in individual mitochondrion. Recently, we uncovered a role for clu in the regulation of differential integrin subunit export from the perinuclear ER in 3rd larval instar (L3) body wall muscles (38). These muscles are an ideal model to study mitochondrial morphology and function (46). Not only are these cells relatively large with multiple small nuclei, but high energy-consuming tissues, like muscle, tend to be sensitive to perturbations in mitochondrial structure and/or function (6,45). Thus, we chose to focus on Drosophila larval muscles 6 and 7 [ventral longitudinal (VL) 3 and 4] to examine how mutations in clu affect mitochondrial morphology. Two clu null alleles were used for analysis, the P-element insertion clud08713 (clud08713) and the deletion mutant cluΔW, which removes the 5′UTR and start codon of Clu (35,38).

In wild-type (WT) L3 muscles, the majority of mitochondria appeared tubular with organized cristae as shown by immunofluorescence staining against mitochondrial Complex V (α-ATPase 5α) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of individual organelles (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). In contrast, clustered mitochondria were round with disrupted cristae in all clu null alleles examined (Fig. 1A and C; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A) (38). Moreover, muscle-specific OE of Clu-Myc in a clu mutant background restored the mitochondrial morphology to WT, and did not phenocopy the small, circular mitochondria induced by the OE of Clu alone (Fig. 1C). Locomotor defects in clu mutants cannot solely be attributed to defective mitochondrial morphology in muscle, as RNAi knockdown of clu in either muscle or neuronal tissues impaired mobility (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B).

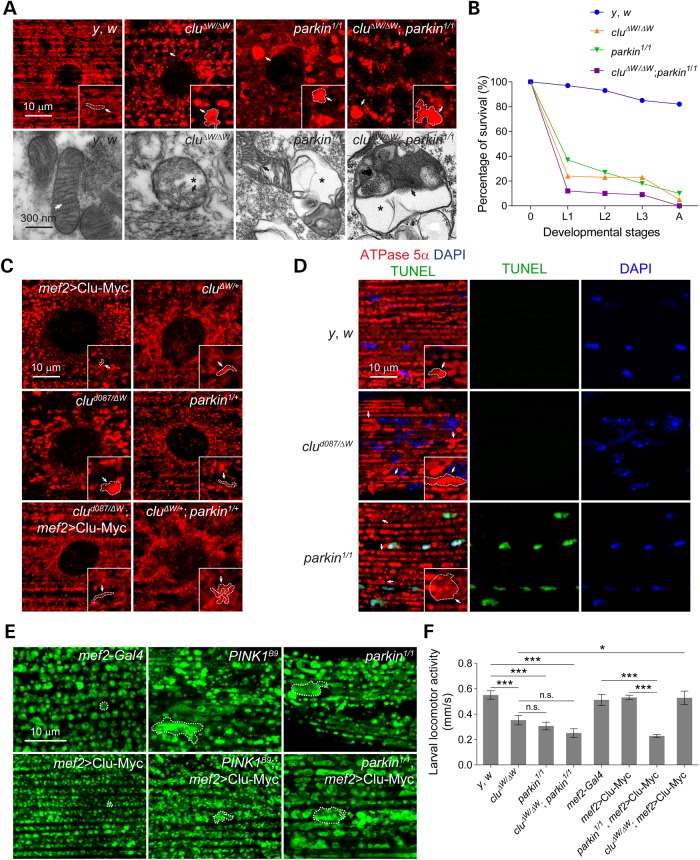

Figure 1.

clu genetically interacts with parkin and OE of Clu partially rescues PINK1, but not parkin mutants. (A) Upper panel: ventral-lateral (VL) muscles from L3 larva of the indicated genotypes stained with anti-ATPase 5α. Lower panel: TEM images of mitochondria in L3 larval muscles. Arrows indicate mitochondrial cristae and asterisks show swollen regions of the mitochondrial matrix. (B) Lethality curves of clu mutants, parkin mutants or clu; parkin double mutants throughout development. L1, 1st instar larva; L2, 2nd instar larva; L3, 3rd instar larva; A, adults. n = 100 for each genotype. (C) VL muscles from larva of the indicated genotypes stained with anti-ATPase 5α. Arrows in insets indicate clustered mitochondria. (D) Adult IFMs from control flies, clu mutants or parkin mutants stained with anti-ATPase 5α (red), TUNEL (green) and DAPI (blue). The insets show a magnified area in each image and single mitochondria are highlighted with arrows. (E) Adult IFMs of the indicated genotypes stained with anti-ATPase 5α. Dotted circles outline a single mitochondrion. Single mitochondrion is outlined by a dotted line for (A)–(E). (F) Quantification of larval mobility in clu mutants, parkin mutants clu; parkin double mutants or Clu OE. n = 15–20 larvae for each genotype. Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

The mitochondrial phenotypes in Drosophila clu mutants were similar to, but not identical, to mutations in parkin. Consistent with a previous study (47), large swollen mitochondria were present in parkin mutant muscles (Fig. 1A, top panel; Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). Transmission electron micrographs of individual mitochondrion in parkin mutants revealed a loss of organized cristae as in clu mutants, but additionally showed larger swollen regions within mitochondria (Fig. 1A, lower panel). The adult indirect flight muscles (IFM) of parkin mutants undergo muscle degeneration and subsequent cell death (15,45). Thus, we asked whether the IFMs in clu mutants also display cell death using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) on dissected thoraces from 4-day-old flies. Most nuclei in IFMs from parkin mutants were labeled with TUNEL, whereas muscles from WT and clu mutants were not TUNEL (+) (Fig. 1D).

Consistent with previous observations that clu and parkin genetically interact in germline cells (35), we observed mitochondria clustered around muscle nuclei in clu/+; parkin/+ double heterozygotes, but not in clu/+ or parkin/+ single heterozygotes (Fig. 1C, right panel). To further define if clu and parkin function in the same or different pathways, we examined animals doubly mutant for both clu and parkin. Double mutants would be expected to exhibit a phenotype similar to each mutant alone if these genes act in the same pathway, while double mutant phenotypes would be stronger if two separate pathways are affected. Analysis of mitochondrial morphology in clu; parkin mutant muscles showed an overall decrease in mitochondrial content (40) and deteriorated mitochondrial morphology compared with clu or parkin mutants alone (Fig. 1A). While single clu and parkin mutants each displayed a similar lethality profile of 5–10% adult escapers (Fig. 1B), clu; parkin double mutants did not yield any viable adults (Fig. 1B). Based upon the stronger phenotypes observed in clu; parkin double mutants, we conclude that clu and parkin likely function in independent pathways to regulate mitochondrial morphology. To determine the basis for the observed genetic interaction between clu and parkin (Fig. 1C), we examined mitochondrial morphology in adult IFMs upon when Clu OE in parkin mutants. Although Clu OE alone resulted in mitochondrial fragmentation in larvae (Fig. 1C, left panel) or adult IFMs (Fig. 1E), it failed to rescue the swollen mitochondrial phenotype and the defective larval locomotor activity in parkin mutant flies (Fig. 1E and F). In contrast, the swollen mitochondria were partially ameliorated in PINK1 mutants upon Clu OE (Fig. 1E).

PINK1 and Parkin OE ameliorate mitochondrial and locomotor defects upon clu RNAi knockdown

In Drosophila, the PINK1–Parkin pathway promotes turnover of respiratory chain (RC) proteins and OE of Parkin increases lifespan (48,49). In addition, OE of anti-oxidant genes can partially reverse increased levels of ROS in cells from PD patients or parkin mutant flies (26,50–54). As clu mutant adult flies have decreased levels of mitochondrial proteins and increased oxidative stress (39,40), we analyzed if OE of PINK1, Parkin or the anti-oxidant proteins Catalase, Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) or Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) can compensate for decreased clu levels. Knockdown of clu using RNAi (38) effectively reduced Clu protein levels (Fig. 2C) and phenocopied the IFM mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 2A), larval mobility (Fig. 2B) and adult eclosion defects (Fig. 2C) present in clu null mutants. All of these mutant phenotypes were restored to WT by PINK1 or Parkin OE, but not upon Catalase, SOD1 or SOD2 OE (Fig. 2A–C). These data indicate that elevated ROS are not responsible for the mitochondrial and mobility defects observed in clu RNAi flies.

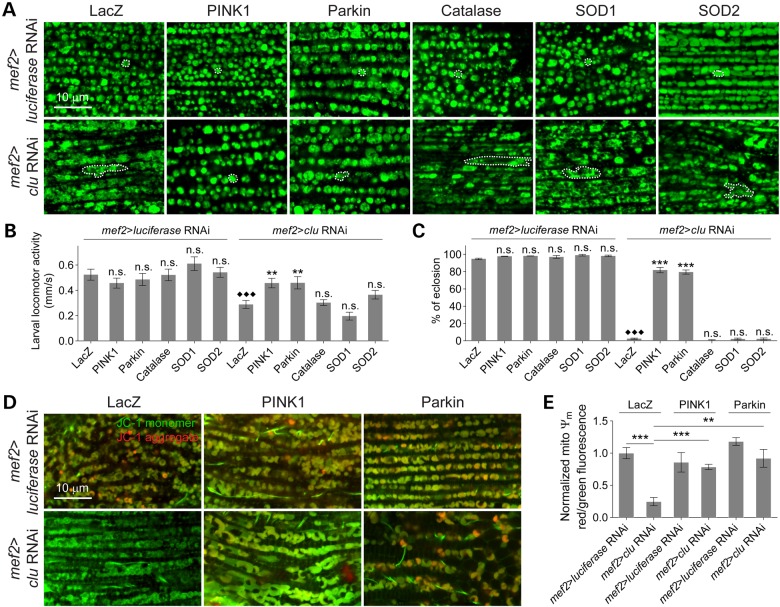

Figure 2.

Overexpression of PINK1 or Parkin rescues defects caused by clu knockdown. (A) LacZ, PINK1, Parkin, Catalase, SOD1 or SOD2 were overexpressed in adult IFMs in either luciferase RNAi (control) or a clu RNAi background. Single mitochondrion is circled (dotted line). (B and C) Quantification and comparison of larval mobility (n = 10–15 larvae for each genotype) and adult eclosion (n = 90–120 total pupae for each genotype) of the indicated genotypes. Asterisks and n.s. (not significant) indicate comparisons between PINK1, Parkin, Catalase, SOD1 or SOD2 OE and the LacZ OE controls from either a luciferase RNAi or a clu RNAi background, whereas diamonds indicate the comparisons between LacZ OE in clu RNAi flies compared with LacZ OE in the luciferase RNAi flies. (D) IFMs from adults of LacZ, PINK1 or Parkin OE in a luciferase RNAi or clu RNAi background stained with JC-1 dye to show the Ψm. Green monomers stain all mitochondria, while red polymers are formed in polarized mitochondria (n = 5 adult thoraces for each genotype). (E) Quantification of normalized red/green fluorescence. Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, **P < 0.01, *** or ♦♦♦P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

Given that clu mutants have decreased ATP levels and selectively reduced levels of RC proteins (39,40), we next examined general mitochondrial health by assessing inner mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψm). JC-1 is a cationic fluorescent dye that accumulates proportionally with the strength of the membrane potential (55). The monomeric form of JC-1 emits at ∼529 nm (green) and higher potentials result in red fluorescent aggregates with an emission maximum of ∼590 nm (red). Thus, measurement of the relative red:green fluorescence intensity is a reliable indicator of ΔΨm and overall viability. In control IFMs, both green monomer and red polymer JC-1 staining patterns were observed, whereas the red fluorescence was lost in clu RNAi muscles (Fig. 2D and E), indicating a loss of Ψm. PINK1 or Parkin OE in clu RNAi muscles recovered the Ψm (Fig. 2D and E), suggesting that PINK1 or Parkin OE may promote MQC of damaged mitochondria upon depletion of Clu.

Our previous study showed that administration of two chemical chaperones, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) and 4-phenylbutyric acid (PBA), to clu RNAi larvae alleviate ER stress, rescue abnormal αPS2 integrin accumulation around the perinuclear ER and improves their locomotor activity (38). Long-term uptake of these drugs neither rescued the abnormal mitochondrial morphology defects nor increased adult eclosion rates in clu RNAi larva (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A and B). Therefore, the mitochondrial function of Clu is independent of its role in integrin subunit transport.

Loss of Clu leads to mitochondrial recruitment of Parkin

In multiple Drosophila tissues, Clu protein is present in puncta and in close proximity to mitochondria (35,38,39). This punctate distribution of Clu is lost in parkin mutant Drosophila female germline cells (35). Thus, we asked whether the mitochondrial localization of Clu in L3 muscles also depends on the formation of Clu particles maintained by the presence of Parkin. Consistent with our previous report, Clu particles were found near mitochondria in WT muscles (Fig. 3A) (38). Mutations in parkin generally abolished Clu puncta, but a portion of diffuse Clu protein was still detected on mitochondria and total Clu protein levels were not altered in parkin mutants (Fig. 3A–C).

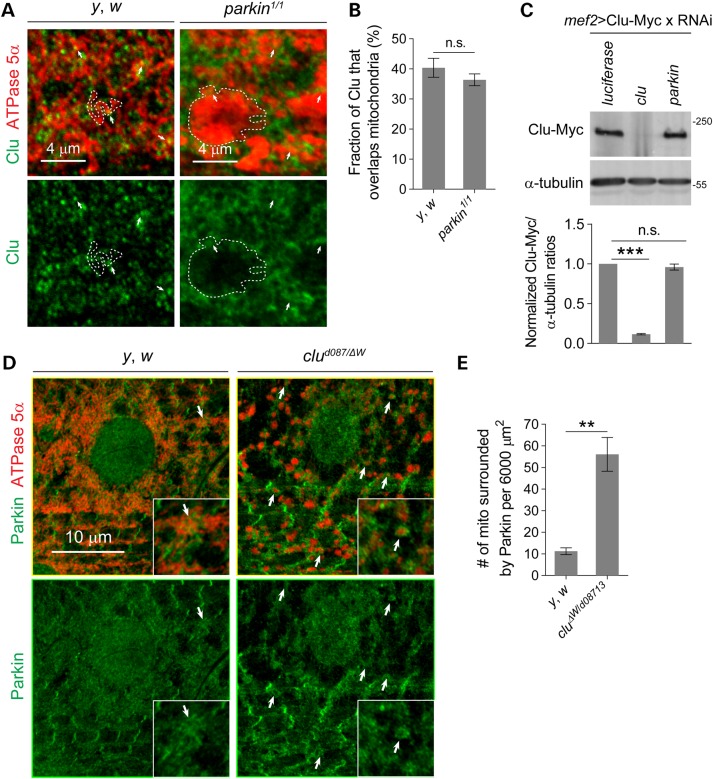

Figure 3.

Clu protein localization is altered in parkin mutants and vice versa. (A) Larval muscles from control (y, w) or parkin mutants stained with anti-ATPase 5α (red) or anti-Clu (green). Arrows show that Clu is in close vicinity or overlapping to mitochondria. Single mitochondrion is outlined by a dotted line. (B) Quantification of the percentage of Clu staining overlapping mitochondria (n = 6 larvae for each genotype). (C) Whole larval lysates in the indicated mutants immunoblotted with anti-Myc to detect Clu (n = 3 experiments) protein levels. Protein levels were normalized to the levels of α-tubulin. (D) Confocal sections show muscles from y, w or clu mutant larva stained with anti-Parkin and anti-ATPase 5α. Arrows show mitochondria surrounded by Parkin. (E) Quantification of the number of mitochondria surrounded by Parkin per 6000 μm2 muscles. Mean ± s.e.m. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

Mitophagy mediated by Parkin translocation to damaged mitochondria requires depolarized Ψm and is conserved from humans to Drosophila (20,22,23,56). Since clu deficiency also leads to a reduction in Ψm, we used immunostaining to assess whether endogenous Parkin localization in larval muscles was altered. In WT muscles, Parkin was largely distributed in the myoplasm and partially accumulated in a striated pattern (Fig. 3D). Only a few mitochondria were surrounded by Parkin, suggesting a low level of mitochondrial clearance (Fig. 3D and E). However, in clu mutant muscles, a large number of mitochondria were enveloped by Parkin (Fig. 3D and E), indicating that mitophagy may be induced.

Parkin translocates to damaged mitochondria upon depletion of Clu, but the mitochondrial clearance is abrogated

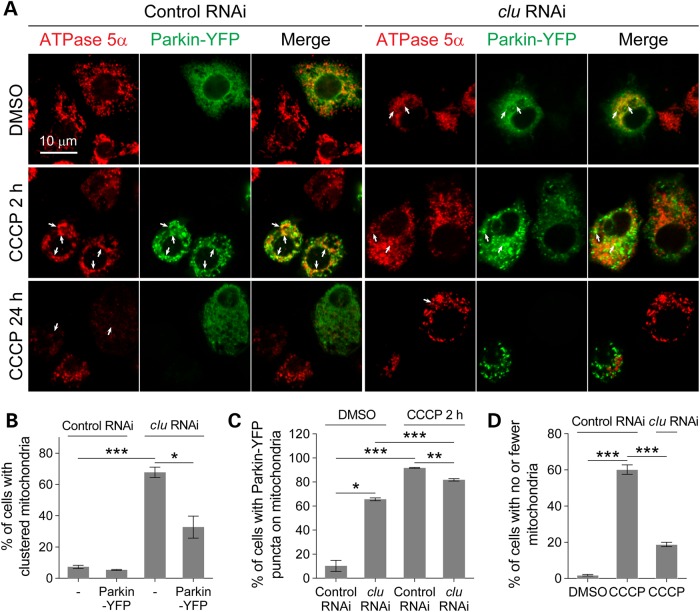

To further discriminate whether the presence of Parkin-localizing mitochondria in clu mutants signifies ongoing mitophagy or impeded mitochondrial clearance, we generated a Parkin-YFP construct used in a previous study (20) and performed mitophagy assays by transiently transfecting Parkin-YFP into S2 cells followed by treatment with the mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) to induce mitophagy. Given that the white gene is not expressed in S2 cells, we treated cells with white double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) as a control. Treating cells with clu dsRNA efficiently reduced Clu protein levels and over 60% of the cells exhibited clustered mitochondria (Fig. 4A and B; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A). In control RNAi cells treated with the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Parkin-YFP was largely diffuse throughout the cytoplasm, but translocated to mitochondria upon a 2 h incubation with CCCP (Fig. 4A and C), consistent with previous studies in Drosophila S2 cells and other mammalian cell lines expressing tagged Parkin (20,22,56,57). Intriguingly, Parkin-YFP translocated to mitochondria in DMSO-treated clu RNAi cells (Fig. 4A and C). However, further mitochondrial accumulation of Parkin-YFP triggered by CCCP was impeded (Fig. 4A and C), although the mitochondrial clustering defects were partially rescued (Fig. 4A and B). After CCCP incubation for 24 h, most control cells were depleted of mitochondria due to robust mitophagy, whereas ∼72% of clu RNAi cells preserved mitochondria (Fig. 4A and D). Similar results were observed in cells transfected with mouse LC3-GFP (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B and C), a marker for the presence of autophagosomes (58). These data show that mitophagy is impaired in Clu-deficient cells.

Figure 4.

Depletion of Clu induces mitochondrial translocation of proteins required for mitophagy, but mitochondrial clearance is impeded. (A) S2 cells were treated with the indicated dsRNAs for 48 h before transfection with Parkin-YFP (green) for an additional 16 h. The cells were treated with DMSO or 20 μm CCCP, harvested after 0, 2 or 24 h, and immunostained with anti-ATPase 5α (red). Arrows indicate mitochondrial localized Parkin-YFP after DMSO or 20 μm CCCP treatment for 0 and 2 h, or presence of mitochondria after treatment for 24 h. (B–D) The extent of mitochondrial clustering (B), mitochondrial translocation of Parkin-YFP (C) and mitophagy (D) were quantified for the experiments described in A (n > 100 cells in each condition). Mean ± s.e.m. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

Autophagosomes are recruited to, but fail to engulf enlarged mitochondria upon loss of Clu in vivo

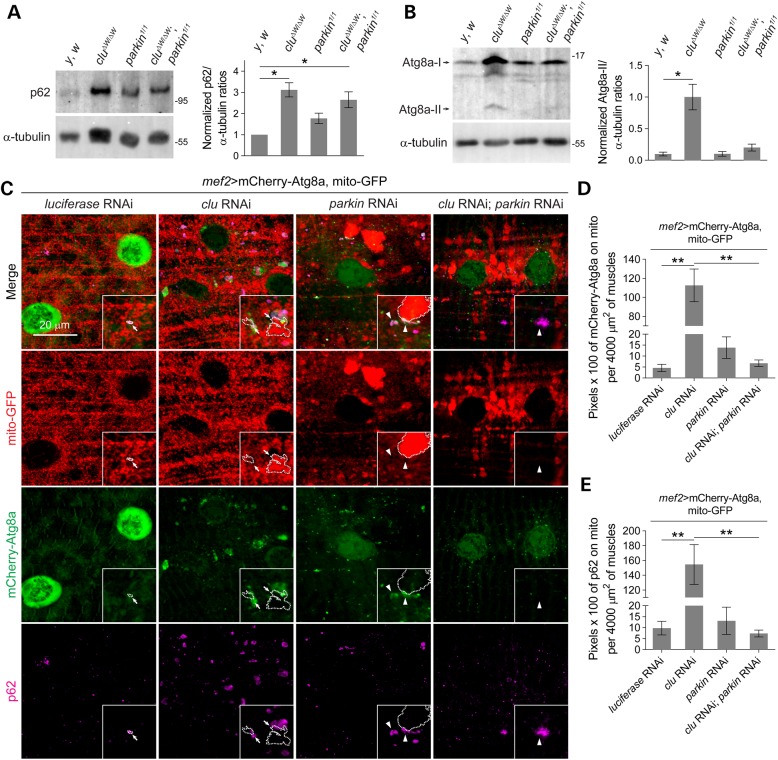

To further explore our finding that mitophagy is impeded upon loss of Clu, we examined protein levels in whole larval lysates for two autophagy markers, p62 and Atg8a. p62, or Ref(2)P in Drosophila, is degraded during autophagy and the inhibition of autophagy results in the accumulation of p62 (59–61). Atg8a-II, also known as LC3-II, is a lipid-conjugated form of Atg8a-I that marks autophagosomes (59–62). The protein levels of p62 were remarkably increased in clu mutants or clu; parkin double mutants, but not significantly elevated in parkin mutant flies (Fig. 5A). Similarly, Atg8a-II levels were increased in clu mutants compared with control lysates (Fig. 5B). Immunoblots of S2 cells also showed an increase in endogenous Atg8a-II in clu knockdown cells compared with control cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D). These results are consistent with our in vitro data showing that loss of Clu impedes mitophagy.

Figure 5.

Loss of Clu results in autophagosome recruitment to damaged mitochondria, but failure to engulf the whole enlarged mitochondria for clearance in vivo. (A and B) Whole larval lysates of y, w, clu, parkin or clu; parkin mutants were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted using anti-p62 (A), anti-Atg8a (B) or anti-α-tubulin. Quantifications of p62 or Atg8 levels were normalized to α-tubulin (n = 3 experiments). (C) Single confocal images show the localization of mCherry-Atg8a (green) and anti-p62 (purple) in relation to mitochondria (mito-GFP, red) upon RNAi knockdown of clu, parkin or both, in larval VL muscles. Mitochondria decorated with or without mCherry-Atg8a or p62 are indicated by arrows or arrowheads, respectively. Note that mCherry-Atg8a in clu RNAi muscles fails to envelop the entire/swollen mitochondria. (D–E) Quantifications of mCherry-Atg8a (D) or p62 (E) localized to mitochondria in muscles of the indicated genotypes using the ‘colocalization’ plugin in ImageJ (n = 6 larvae for each genotype). Mean ± s.e.m. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Scale bars are indicated.

To better understand the overall accumulation of p62 and Atg8a proteins levels observed by western blotting, we examined the in vivo localization of mCherry-Atg8a and p62 in larval muscles. In control luciferase RNAi muscles, mitochondria appeared tubular and few mitochondria were enveloped by mCherry-Atg8a or p62, suggesting a basal level of mitophagy. Clu knockdown muscles showed an accumulation of mCherry-Atg8a (Fig. 5C and D) and p62 (Fig. 5C and E) on numerous mitochondria. However, autophagosomes marked by mCherry-Atg8a (arrows) failed to completely envelope swollen mitochondria (dotted lines) (Fig. 5C), suggesting that these damaged mitochondria are not completely cleared. Notably, this mitochondrial recruitment of autophagosomes was diminished upon concurrent parkin depletion, similar to parkin knockdown alone in muscles (Fig. 5C–E). Therefore, our data demonstrate that the protein translocation of p62 and Atg8a to damaged mitochondria proceed normally upon depletion of clu and is dependent on Parkin, but the engulfment of swollen mitochondria and induction of mitochondrial clearance are hindered.

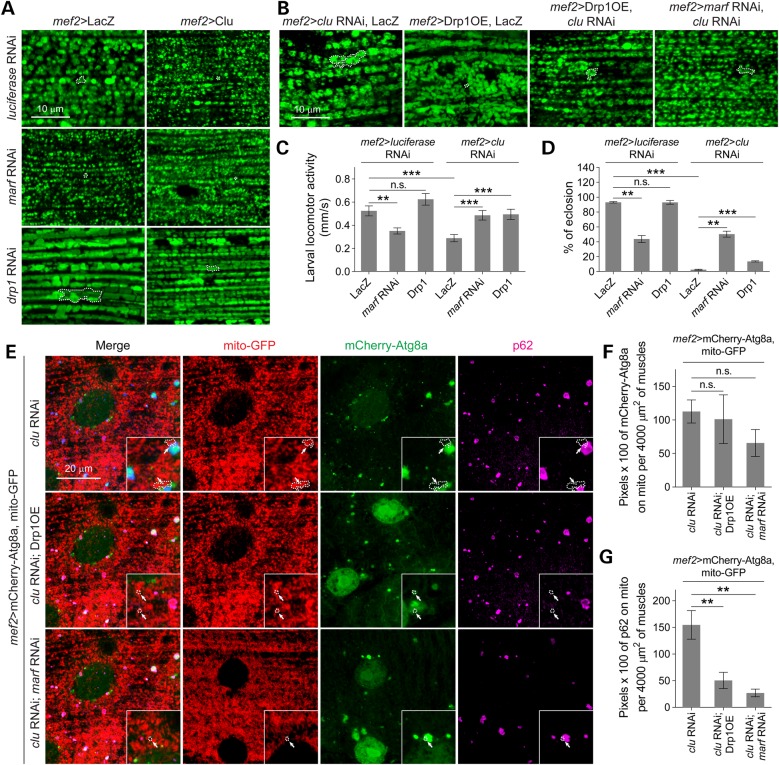

Excessive fission or reduced fusion rescues the swollen mitochondrial clu phenotype

Previous studies have shown that Marf is a downstream substrate of the PINK1/Parkin pathway in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology (15–17,20). Our observations show that Clu genetically interacts with parkin and loss of Clu leads to a swollen mitochondrial phenotype, similar to parkin mutants (Fig. 1). These data suggest that the enlarged mitochondrial phenotypes in clu mutants may be due to excessive mitochondrial fusion. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that inducing mitochondrial fission or decreasing fusion would rescue the defects in clu knockdown flies. As expected, RNAi knockdown of drp1 or marf alone in adult IFMs resulted in enlarged or fragmented mitochondria, respectively (Fig. 6A). Clu OE appeared to further promote mitochondrial fragmentation in a marf RNAi background and also reduced the swollen size of mitochondria upon drp1 RNAi knockdown (Fig. 6A). To test if the observed interactions between clu, marf and drp1 affect aspects other than mitochondrial morphology, we examined larval mobility and lethality. Overexpression of Drp1 alone did not influence larval mobility or adult eclosion, while marf RNAi alone impaired larval locomotor activity and resulted in ∼50% pupal lethality (Fig. 6C and D). In a clu RNAi background, Drp1 OE restored larval mobility and slightly rescued the adult eclosion rate (Fig. 6B–D). Inhibition of Marf activity by RNAi phenocopied the Drp1 OE results, but also led to increased eclosion of adult flies (Fig. 6B–D), possibly indicating a more direct role for Clu through Marf than Drp1. These data suggest that inhibiting the fusion of damaged mitochondria upon loss of Clu protects the pool of healthy mitochondria in the cell.

Figure 6.

clu genetically interacts with mitochondrial fission/fusion genes and promotion of mitochondrial fission rescues defects caused by loss of Clu. (A and B) Adult IFMs of the indicated genotypes were stained with anti-ATPase 5α (green). (C and D) Quantification of larval mobility (n = 15 larvae for each genotype) and adult eclosion (n = 100–120 total pupae for each genotype) upon manipulating Marf or Drp1 levels in luciferase or clu RNAi backgrounds. (E) The localization of mCherry-Atg8a (green) and anti-p62 (purple) were examined in relation to mitochondria (mito-GFP, red) in cluRNAi, cluRNAi; Drp1OE or cluRNAi; marfRNAi larval VL muscles. Arrows show mitochondria decorated with or without mCherry-Atg8a or p62. Note that mCherry-Atg8a in clu RNAi muscles fails to envelop the swollen mitochondria, while it surrounds a portion of fragmented mitochondria in cluRNAi; Drp1OE or cluRNAi; marf RNAi muscles. (F–G) Quantifications of mitochondrial-localized mCherry-Atg8a or p62 in muscles of the indicated genotypes (n = 6 larvae for each genotype). Single mitochondrion is outlined with a dotted line in A, B and E. Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

DRP1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) have reduced Parkin-mediated mitophagy compared with WT MEFs, whereas inhibition of fusion ameliorates mitochondrial defects resulting from loss of parkin in flies (15,18,26). These data, in combination with our results that the swollen clu mitochondrial phenotype can be restored by decreased mitochondrial fusion or elevated fission (Fig. 6B–D), prompted us to determine whether this rescue resulted from the recovery of mitophagy on isolated mitochondria. For this set of experiments, the distribution mCherry-Atg8a and mito-GFP were examined in the larvae of clu RNAi, clu RNAi; Drp1OE or clu RNAi; marf RNAi. Inducing mitochondrial fission by either Drp1 OE or a decrease in Marf levels in a clu RNAi background did not alter the relative percentage of mitochondrial autophagosomes as marked by Atg8a (Fig. 6F). This suggests that reducing mitochondrial size does not alter the induction of mitophagy or affect the ability of autophagosomes to translocate to mitochondria (arrows in Fig. 6E). However, the relative amount of p62 on mitochondria was decreased (Fig. 6E and G), suggesting that the impaired mitophagic flux caused by clu knockdown was partially recovered. Intriguingly, induction of mitochondrial fragmentation and rescue to a WT tubular mitochondrial morphology shape was more effective upon knockdown of marf than Drp1 OE in a clu RNAi background (Fig. 6E). Together, these data indicate that promotion of mitochondrial fragmentation upon loss of Clu can facilitate the clearance of damaged mitochondria, without changing the induction of mitophagy.

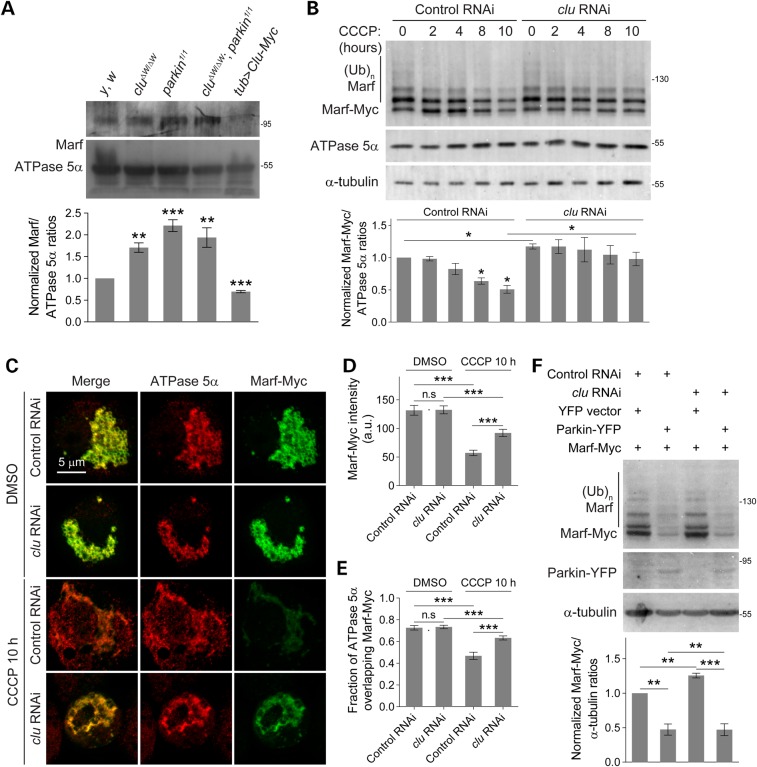

Marf is stabilized upon loss of Clu

Multiple lines of evidence led us to postulate that Clu may influence Marf protein levels. First, Clu OE phenocopies the small, round mitochondrial morphology defects observed in marf RNAi muscles (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Second, Clu OE suppresses mitochondrial fusion to promote mitochondrial fission in drp1 RNAi muscles (Fig. 6A). Finally, marf RNAi knockdown rescues the defective autophagosome mitochondrial engulfment in clu RNAi muscles better than Drp1 OE (Fig. 6E–G). To test how Clu affects Marf, we examined endogenous Marf protein levels in whole larval lysates and found that Marf protein was increased in clu or parkin single mutants and clu; parkin double mutant flies. In addition, ubiquitous Clu-Myc expression with tub-Gal4 decreased the overall amount of Marf protein (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, we also found that RNAi knockdown of clu in S2 cells increased the levels of endogenous Marf compared with control cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4C).

Figure 7.

Loss of Clu impairs Marf degradation. (A) Whole larval lysates of the indicated mutants immunoblotted with anti-Marf. Protein levels were normalized to the levels of ATPase 5α. (n = 4 experiments). (B) S2 cells were treated with either control or clu dsRNA for 2 h and again at 48 h before transfection with Marf-Myc. After expression for 36 h, cells were incubated with DMSO or 20 μm CCCP for the indicated time. Whole cell lysates were collected and subjected to SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using anti-Myc, anti-ATPase 5α and anti-α-tubulin. The levels of Marf-Myc were quantified by normalizing to ATPase 5α protein levels. Statistics show comparison between 0 h CCCP treatment and other time points in the same dsRNA treated cells (n = 3 experiments). (C) S2 cells treated with indicated dsRNAs were incubated with DMSO or 20 μm CCCP for 10 h, then immunostained with anti-Myc (green) and anti-ATPase 5α (red). (D and E) The intensity of Marf-Myc (D) or the overlap between Marf-Myc and mitochondria (E) are shown (n = 20 cells for each condition). (F) S2 cells treated with either control or clu dsRNA were transfected with Parkin-YFP or the YFP vector alone. After 36 h, the cells were harvested. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using anti-YFP, anti-Myc or anti-α-tubulin. The levels of Marf-Myc were normalized to α-tubulin and are presented in the graph below (n = 5 experiments). Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

To test whether Clu affects Marf levels during mitophagy, we expressed a Myc-tagged version of Marf in Drosophila S2 cells and examined the resulting protein levels and ubiquitination state. Incubation in DMSO had no influence on Marf-Myc levels (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). As expected, the levels of Marf-Myc decreased in control cells upon CCCP treatment, whereas the relative amounts of both Marf-Myc and Ubi-Marf-Myc were preserved in clu RNAi cells after prolonged CCCP incubation (Fig. 7B). Immunofluorescence staining showed that both the Marf-Myc pixel intensity and its colocalization on mitochondria were decreased in CCCP-treated control cells (Fig. 7C–E). Marf levels were maintained in clu knockdown cells although Marf-Myc intensity levels in control or clu RNAi cells were similar with DMSO treatment (Fig. 7D). One explanation for this result is that the fluorescence intensity may only reflect an average density of the signals, but not the total amount of labeled protein in an entire area. To examine whether Clu influences Marf stability through the Parkin pathway, we coexpressed YFP-tagged Parkin with Marf-Myc in control or clu RNAi cells. Consistent with the results obtained in Figure 7B, control cells transfected with YFP vector alone showed decreased Marf-Myc levels, while Marf levels were elevated in clu RNAi cells (Fig. 7F). The addition of Parkin still promoted Marf-Myc degradation in both control and clu RNAi cells (Fig. 6F), consistent with our previous results that Clu and Parkin act in independent pathways.

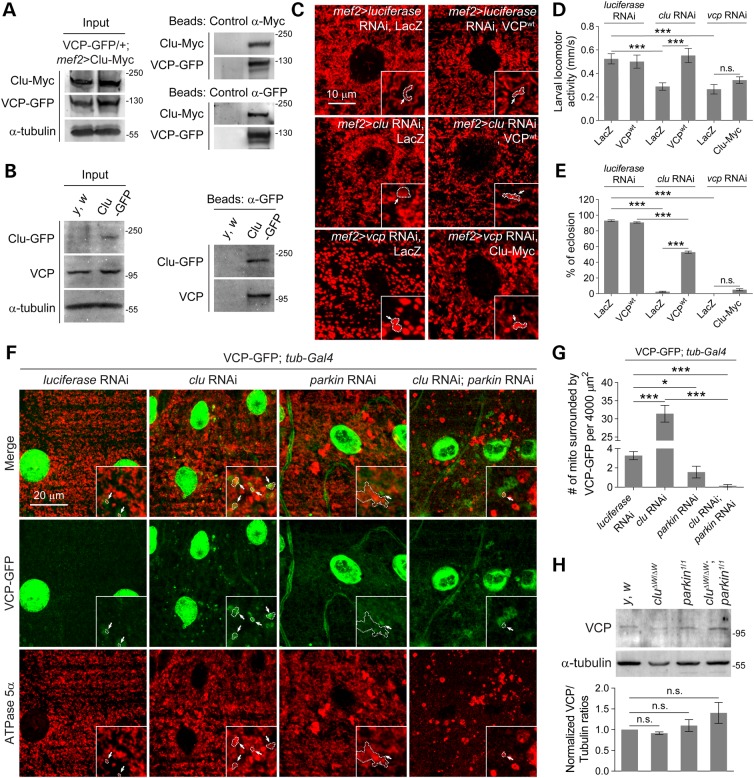

Clu biochemically and genetically interacts with VCP to regulate mitochondrial morphology and loss of Clu induces Parkin-dependent mitochondrial recruitment of VCP

To better understand how Clu affects MQC, we overexpressed Myc-tagged Clu in larval muscles using mef2-Gal4 and performed immunoprecipitations (IPs) using an anti-Myc antibody followed by mass spectrometry. We identified VCP as a possible Clu interacting protein. VCP is a multifunctional protein involved in many different processes, including the DNA damage response, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and autophagosome biogenesis (63–69). The ATPase activity of VCP is proposed to extract ubiquitinated proteins from protein complexes or membranes for recycling or proteasomal degradation (70). Importantly, this VCP extraction activity is critical for the degradation of Mitofusin 1 and 2 to promote MQC (18,24).

We first confirmed the physical binding of both overexpressed and endogenous Clu with VCP in larval muscles (Fig. 8A and B). Next, we examined if clu and vcp genetically interact to regulate mitochondrial morphology. VCP OE in clu RNAi muscles partially suppressed the enlarged mitochondrial phenotype (Fig. 8C), fully restored larval locomotion (Fig. 8D) and partially rescued adult eclosion (Fig. 8E). VCP OE alone had no effect (Fig. 8C–E). Knockdown of vcp in L3 muscles resulted in round and swollen mitochondria (Fig. 8C). Larval muscles expressing vcp RNAi also showed defective mobility (Fig. 8D) and did not yield viable adults (Fig. 8E). Although Clu OE in a vcp RNAi background appeared to slightly alter the abnormal mitochondrial morphology in muscles, the majority of mitochondria were still swollen (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, there was no significant rescue in either larval mobility or adult eclosion rates (Fig. 8D and E). Notably, Clu OE in the adult IFMs suppressed the swollen mitochondrial phenotypes resulting from the expression of VCP mutants (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5), suggesting that mitochondrial fragmentation caused by Clu OE requires functional VCP. These data, taken together, indicate that Clu is upstream of VCP.

Figure 8.

Clu binds to and is upstream of VCP and knockdown of Clu leads to accumulation of VCP on mitochondria. (A) Lysates were collected from whole larva with GFP-tagged endogenous VCP also expressing Myc-tagged Clu under control of the muscle driver, mef2-Gal4. Either Myc or GFP antisera was added to IP protein complexes, while control IPs contained no antibody. The resulting protein complexes were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted using anti-Myc or anti-GFP. (B) Lysates were collected from y, w or Clu GFP larvae. Anti-GFP beads were added to both lysates for IPs. The resulting protein complexes were subjected to SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted using anti-VCP or anti-GFP. (C) Larval VL muscles of the indicated genotypes were stained with anti-ATPase 5α (red). Arrows point out a single mitochondrion (inset). (D and E) Quantification and comparison of larval mobility (n = 15 larvae for each genotype) and adult eclosion (n = 100–110 total pupae for each genotype) upon VCP OE in control (luciferase RNAi) or clu knockdown (clu RNAi) and Clu OE in a vcp RNAi background. (F) Larval VL muscles of indicated RNAi stained with anti-ATPase 5α (red). Arrows illustrate mitochondria decorated with VCP-GFP (green). (G) Quantifications of VCP-GFP surrounded mitochondria (n = 6 larvae for each genotype). (H) Whole larval lysates in the indicated mutants were immunoblotted with anti-VCP and anti-α-tubulin to detect VCP protein levels (n= 3 experiments). Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

Since our observations show that multiple protein markers for mitophagy, including Parkin, Atg8a, p62, were associated with mitochondria upon depletion of Clu (Figures 3 and 5), we examined the protein localization of endogenous VCP using a VCP-GFP trap line in L3 larval muscles. In luciferase RNAi control muscles, VCP-GFP was prominent in nuclei and localized near a few mitochondria (Fig. 8F and G). However, in clu RNAi muscles, VCP-GFP enveloped multiple mitochondria and this mitochondrial recruitment of VCP-GFP was Parkin-dependent (Fig. 8F and G), similar to our results with Atg8a and p62 (Fig. 5) and consistent with results from previous studies (18,24). However, total VCP levels were not altered in clu or parkin single mutants, or clu; parkin double mutant flies (Fig. 8H). Here we conclude that Clu and VCP biochemically and genetically interact to regulate mitochondrial morphology, possibly to regulate MQC through Marf degradation.

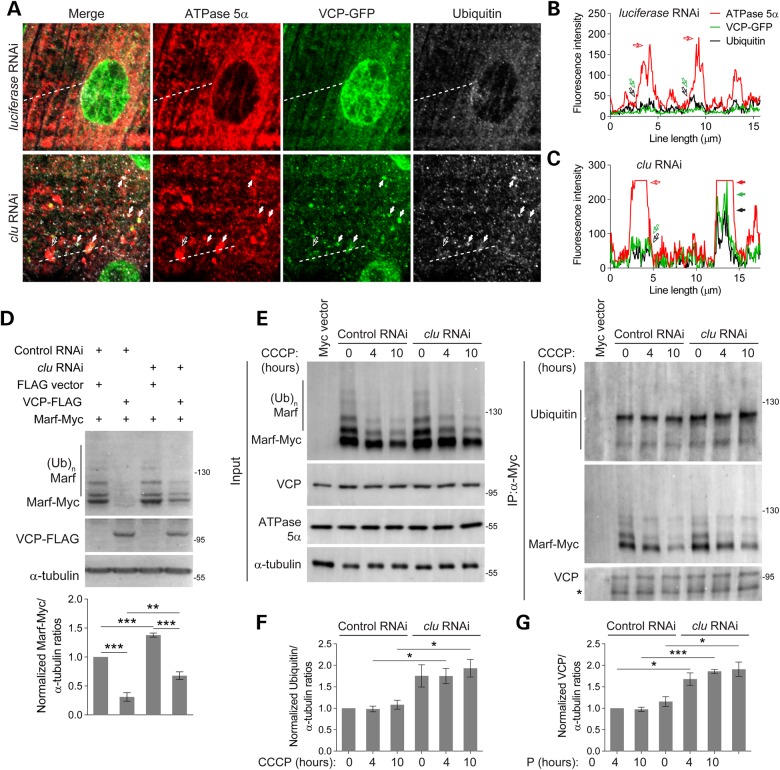

Clu is involved in Marf degradation through VCP

VCP is required for mitophagy by promoting the proteasomal degradation of Mfn/Marf (18,24). Loss of Clu hinders mitochondrial clearance (Fig. 4; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3), enhances the mitochondrial recruitment of VCP (Fig. 8), and prevents Marf degradation (Fig. 7B, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B and C). Thus, we hypothesized that VCP fails to extract ubiquitinated-Marf from the mitochondria in Clu-depleted muscles, leading to enlarged mitochondria that are unable to be cleared by autophagy. Since we did not possess an anti-Marf antibody that works in tissue, we examined the levels of ubiquitinated proteins on mitochondria relative to VCP-GFP. We found that many swollen mitochondria in clu RNAi muscles accumulated ubiquitinated proteins and VCP-GFP in the same location (Fig. 9A–C). Since we have established that VCP and Clu physically and genetically interact and VCP OE partially rescues clu phenotypes (Fig. 8), we further examined whether Clu influences the stability of Marf through VCP. We transfected S2 cells with FLAG-tagged VCP or an empty FLAG vector in control or clu RNAi cells. Consistent with the results in Figure 7F, control cells transfected with FLAG vector alone showed decreased Marf-Myc levels upon treatment with CCCP, while Marf-Myc levels remained unchanged in clu RNAi cells (Fig. 9D). However, Marf-Myc protein still persisted with concurrent VCP-Flag expression in clu RNAi cells (Fig. 9D). These results indicate that Clu promotes VCP-mediated Marf degradation. Since VCP is required for mitophagy by promoting the proteasomal degradation of Mfn/Marf (18,24) and VCP abnormally accumulates elevated levels of ubiquitinated proteins on swollen mitochondria in clu knockdown muscles (Fig. 9), it is possible that higher levels of ubiquitinated Marf are preserved when Clu is depleted during mitophagy. To test this, we transfected S2 cells with Marf-Myc and performed anti-Myc IPs. Immunoblots using anti-ubiquitin showed significantly increased levels of total Marf-Myc conjugated with poly-ubiquitin in clu RNAi compared with control cells (Fig. 9E and F). Nearly all cells treated with CCCP in control or clu RNAi cells showed high levels of ubiquitin on mitochondria (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4D and E). Thus, we conclude that Clu is involved in VCP-mediated Marf degradation.

Figure 9.

Clu is involved in VCP-mediated ubiquitinated-Marf degradation. (A) Larval muscles with GFP-tagged endogenous VCP expression and indicated genotypes were immunostained with anti-Ubiquitin and anti-ATPase 5α. (B and C) Single confocal images in (A) were used to draw a line on mitochondria to calculate fluorescence intensity of mitochondria, ubiquitin and VCP-GFP by the ‘linear profile’ macro in ImageJ. (D) S2 cells treated with either control or clu dsRNA were transfected with VCP-FLAG or the FLAG vector alone. After 36 h, the cells were harvested. Whole cell lysates were subjected to SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG, anti-Myc or anti-α-tubulin. The levels of Marf-Myc normalized to α-tubulin are presented in the graph below (n = 5 experiments). (E) S2 cells treated with indicated dsRNA were transfected with Marf-Myc, followed by 20 μm CCCP treatment for 0, 4 or 10 h. Whole cell lysates were incubated with anti-Myc beads. IP complexes were detected using antibodies against Marf, Ubiquitin or VCP. (F) The levels of ubiquitinated-Marf to α-tubulin were quantified. Asterisks indicate non-specific bands (n = 4 experiments). Mean ± s.e.m. (n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Scale bars are indicated.

Discussion

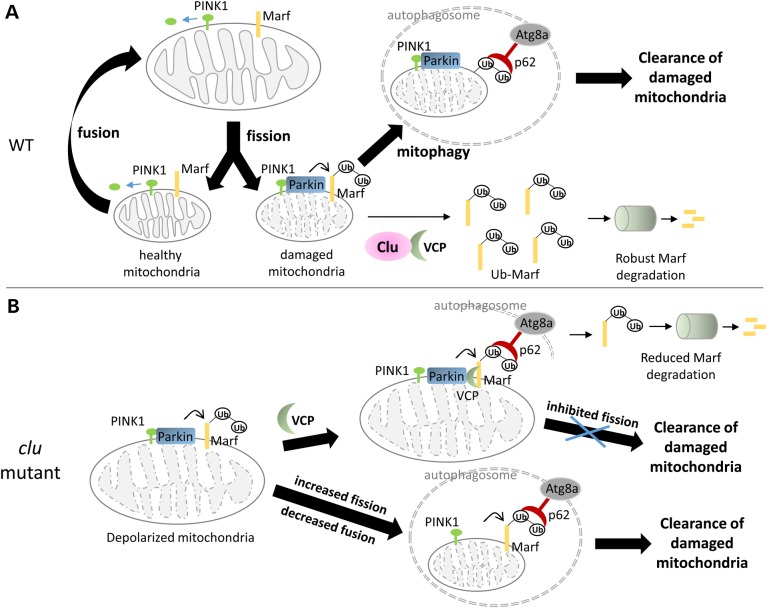

Numerous studies have focused on the activation of PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy upon mitochondrial damage. As shown in Figure 10A, cytoplasmic PINK1 is continuously imported into mitochondria, processed by proteases in the transmembrane space, and transported back into the cytoplasm for proteasomal degradation (71–76). However, when mitochondria are damaged and the membrane potential collapses, PINK1 is stabilized on the outer membrane and, in turn, phosphorylates Parkin and Mfn (22,23,77–80). After the activation of Parkin in the ubiquitination of Mfn/Marf, VCP, together with its cofactors, mediates the degradation of Mfn/Marf in both human and fly cells, presumably to promote the fragmentation of damaged mitochondria for subsequent autophagy (18,24).

Figure 10.

A model for Clu-mediated mitochondrial morphology and Marf degradation through VCP. (A) In WT cells, healthy mitochondria undergo membrane remodeling through repeated rounds of fission and fusion events. The normal targeting of PINK1 (green) to mitochondria is cleaved to prevent protein accumulation. Upon membrane depolarization, the cleavage of PINK1 is inhibited, accumulates on the mitochondrial outer membrane and recruits cytosolic Parkin (blue) to mitochondria. Marf (yellow) is ubiquitinated by Parkin and is extracted from the membrane by VCP/ p97 (light green) for subsequent proteasomal degradation. Our data show that Clu (pink) physically interacts with VCP and promotes efficient Marf turnover. Damaged mitochondria that lack Marf are fusion defective and cannot enter the healthy mitochondrial pool. Parkin-dependent polyubiquitation of outer mitochondrial membrane recruits p62, which links defective mitochondria to the autophagosome for mitophagy. (B) Clu deficiency results in mitochondrial depolarization. As in WT cells, these damaged mitochondria accumulate high levels of Ub-Marf. VCP is recruited to mitochondria, but VCP-mediated Marf degradation by the proteasome is reduced in the absence of Clu. The accumulation of Marf protein impairs fission and leads to enlarged mitochondria that cannot be engulfed by the autophagosome for mitophagy, even though p62 and Atg8a are present. The promotion of mitochondrial fragmentation restores the clearance of damaged organelles.

Here, we have identified an additional component, Clu, that influences ubiquitinated Marf degradation through the activity of VCP. First, both overexpressed and endogenous Clu biochemically interacts with VCP (Fig. 8A and B). Second, clu knockdown leads to an increase in overall Marf protein levels (Fig. 7A and B). Third, Clu OE reduces Marf levels (Fig. 7A) and phenocopies the small mitochondrial morphologies observed in marf RNAi knockdown muscles (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Finally, OE of VCP partially rescues mitochondrial morphology (Fig. 7C), possibly by its partial activity to promote ubiquitinated Marf degradation (Fig. 9D) upon loss of Clu. Previous studies showed that during mitophagy, VCP functions as a ubiquitin-dependent segregase for Mfn degradation by the proteasome in the presence of the Ufd1/Npl4 complex, but VCP ATPase activity is dispensable for its mitochondrial translocation (18,24). In our experiments, although VCP translocation to damaged mitochondria is intact, the extracting activity of VCP activity is impaired (Fig. 7F and G) and likely requires Clu as a cofactor for efficient Marf extraction and degradation.

A notable feature in clu mutants from various organisms is the clustered mitochondrial phenotype (36,81–83). Muscles containing mutations in Drosophila clu have swollen mitochondria with disrupted cristae, resembling mitochondrial phenotypes in parkin mutants. The finding that clu genetically interacts with PINK1 or parkin in the regulation of mitochondrial clustering prompted studies to examine whether Clu plays a role in the PINK1/Parkin pathway. The authors found that Clu partially rescues PINK1, but not parkin mutants (35,40), consistent with our results in Figure 1E, and can be explained by results in Figure 7A where Clu OE reduces Marf protein levels, thus decreasing fusion and reducing the enlarged mitochondrial phenotypes in PINK1 mutants. The intriguing result that Clu OE fails to rescue parkin mutants is similar to published results for VCP. VCP also rescues PINK1, but not parkin mutants, and is essential for the extraction and degradation of Parkin-ubiquitinated Mfn from the mitochondrial outer membrane during mitophagy (18,24).

We speculate that the observed genetic interaction between clu and parkin results from Clu functioning in concert with Parkin to promote MQC through the degradation of Marf on damaged mitochondria (Fig. 7B and F). Indeed, loss of Clu results in decreased Ψm. Sen et al. (40) recently proposed that Drosophila Clu is a negative regulator of the PINK1/Parkin pathway based upon their observations that loss of Clu induces a physical interaction between PINK1 and Parkin. Our data are consistent with their findings, although possibly through a different mechanism. The resulting PINK1–Parkin complex may form as Parkin gets recruited to damaged mitochondria upon a loss of Clu (Figs 3D and 4A) since PINK1 is already stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane after a decrease in Ψm (22,23). Since Clu deficiency may cause mitochondrial damage through a number of mechanisms, the observation that PINK1 OE or Parkin OE can rescue clu mutant phenotypes is consistent with the idea that Parkin OE may increase turnover of damaged mitochondria upon Clu depletion to rescue normal mitochondrial functions. The presence of Parkin on mitochondria is indicative of the induction of mitophagy marked by Atg8a accumulation (Fig. 5B–D). Surprisingly, mitophagic flux is impeded upon mitochondrial damage and p62 levels remain high in clu mutant cells (Fig. 4A and D). There is a corresponding buildup in Marf levels upon clu deficiency, leading to swollen mitochondria that cannot be engulfed and cleared by autophagosomes (Fig. 10B).

We propose that Clu also plays a role in MQC by maintaining the balance between fission and fusion dynamics (Fig. 10B). The weaker mitochondrial morphologies and lack of TUNEL labeling in clu mutant muscles compared with parkin mutants may be explained by the indirect effect of Clu on Marf degradation through VCP (Fig. 1D) versus the direct ubiquitination of Marf by Parkin (18,20). Our speculation is supported by a recent study where OE of Marf in adult IFMs resembles the swollen mitochondrial morphology and muscle cell death phenotypes observed in parkin mutants (57). Excessive Marf levels also explain the mitochondrial defects in clu-depleted muscles, where inhibition of mitochondrial fusion by marf RNAi promotes the clearance of damaged mitochondria (Fig. 6E–G). These data are consistent with previous findings that Parkin can initiate mitophagy in the absence of Mfn and the fission-induced segregation of damaged mitochondria promotes mitophagy (18,25,32,84,85).

Since Clu OE in a marf RNAi background enhances mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 6A), Clu may function in normal mitochondrial remodeling through the degradation of Marf. One possibility is that Clu OE further reduces Marf levels beyond the reduced marf RNAi levels. Alternatively, Clu OE may lead to altered mitochondrial fission due to a role in mitochondrial biogenesis. The levels of mitochondrial proteins are decreased in Drosophila clu mutants (35) or cluH knockdown in human cells (37). Furthermore, human CLUH binds to mRNAs of nuclear encoded mitochondrial proteins, suggesting a role in mitochondrial biogenesis (37). Interestingly, clu; parkin double mutants show markably decreased mitochondrial content compared with single mutants alone (35) and Parkin is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis by promoting local mitochondrial protein translation (86). Thus, double mutations in clu and parkin may aggravate defects in mitochondrial biogenesis, leading to decreased mitochondrial content over single mutants alone, or by depolarizing the Ψm, thus inducing the mitochondrial recruitment of key proteins required for mitophagy and contributing to a loss of mitochondrial protein content through the turnover of damaged proteins.

Clu protein is found in puncta within cells (35,37,38,83). The observations that the formation of Clu particles are maintained by Parkin raise two questions: (1) what comprises the Clu particles? and (2) is the formation of Clu particles critical for its mitochondrial function? Human CLUH was found to form granules in the vicinity to newly formed MTs and enriched in the same fractions with nuclear-encoded mRNA of mitochondrial proteins (37), suggesting that Clu may be involved in mitochondrial RNA transport and metabolism. Recent studies uncovered that PINK1 and Parkin regulate translation of RC mRNAs on the mitochondrial outer membrane by displacement of translational repressors (86). Further work is needed to elucidate whether Parkin functions in concert with Clu and promotes the initiation of localized Clu bound mRNA translation.

Although the pathological relevance of Clu in humans is still unidentified, our studies reveal that Drosophila Clu impacts the PINK1/Parkin pathway by promoting Marf degradation through VCP. Emerging evidence from this study and others show that Clu is a multifunctional protein required for protein exit from the ER, the regulation of mitochondrial mRNAs and mitophagy, all are pivotal events required for cell homeostasis.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

Drosophila melanogaster stocks were maintained on standard cornmeal medium at 25°C, while crosses utilizing the UAS/GAL4 system were cultured at 29°C. The original clud87 (clud08713) was generously provided by Rachel Cox (35). The cluΔW allele, clu RNAi and UAS-Clu-Myc transgenic flies were previously described (38). The UAS-VCPwt and UAS-VCPR152H transgenic flies were kind gifts from Yuh Nung Jan (87). The following stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center: y, w (BL-1495); mef2-Gal4 (BL-27390); tubulin-Gal4 (BL-5138); elav-Gal4 (BL-458); PINKB9(BL-34749); parkin1 (BL-34747); UAS-LacZ (BL-1777); UAS-PINK1 (BL-51648); UAS-Parkin (BL-51651); UAS-Catalase (BL-24621); UAS-SOD1 (BL-33605); UAS-SOD2 (BL-24494); UAS-mCherry-Atg8a (BL-37750); UAS-mito-GFP (BL-8443); UAS-Drp1 (BL-51647); VCP-GFP (TER94CB04973) (BL-51529); luciferase RNAi (BL-31603) (88); parkin RNAi (BL-38333) (26); drp1 RNAi (BL-27682) (89). The vcp RNAi (v-24354) (87) and marf RNAi (v-40478) (90) lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC).

Cell culture, plasmids and transfections

S2 cells were cultured in Schneider's medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma) at 25°C. The open-reading frames for Marf and Parkin were PCR amplified from cDNA clones RE04414 and SD01679 [(Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC)], inserted into the Gateway pENTR vector (Invitrogen) and recombined into the pTWM or pTWV destination plasmids (DGRC), respectively, to generate pUAST-Marf-Myc and pUAST-Parkin-YFP. The pMT-mouse-LC3a construct was obtained from Catherine Rabouille (58) and the pUAST-VCPwt-Flag construct was a kind gift from Yuh Nung Jan (87). Cells were transfected using Cellfectin (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions and harvested after 16–36 h. A pWA-Gal4 vector was cotransfected into cells with the pUAST constructs for constitutive expression, while 1 mm CuSO4 was added to the cells transfected with the pMT construct to induce expression.

RNAi and drug treatment

DNA [(506 base pairs (bps)] amplified from cDNA clone LD19312 was utilized for generating double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) of Clu. A DNA fragment (298 bps) amplified from the third exon of white gene was utilized for generating dsRNAs as a control. In order to amplify the DNA fragment of white gene, mef2-Gal4 flies were homogenized in squishing buffer (10 mm Tris–HCl pH = 8.0, 1 mm EDTA, 25 mm NaCl, 200 μg/ml Protease K) for extraction of genomic DNA. dsRNA was generated using a MEGA script kit (Ambion). The following primers used for RNAi knockdown contain a T7 promoter sequence at the 5′ end: white: 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAACGACATCTGACCTATCGGC-3′; and 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGAAGACGGCTGATGAATGGT-3′; and clu: 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGTGGAGTGCAAGGGCATT-3′; and 5′-GAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGAGCGCAAGCCCGCTTTA-3′.

A total of 3 × 106 cells were cultured in six-well plates and incubated with 20 μg dsRNA probe in serum-free Schneider's medium for 2 h, followed by replacement with complete medium. After culturing for 48 h, cells were treated with dsRNA again and grown in complete medium for another 24 h before transfection. Cells were incubated with 20 μm CCCP or an equal amount of DMSO for the indicated time.

IP and western blots

L3 larva or S2 cells were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris–HCl pH = 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 50 μm MG-132, 50 μg/ml PMSF, 1× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.). After centrifugation at 4°C at 12 000 × g for 15 min, the resulting supernatants were removed for IP and incubated with 25 μl anti-Myc conjugated beads, 25 μl GFP-Trap beads (ChromoTek), or regular protein A beads (Zymed) for 4 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled in 6× Laemmli buffer. For the analysis of protein levels, the supernatant was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), transferred to polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.), and probed with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-Myc (9E10, 1:1000, a kind gift from Brian Geisbrecht); rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, Invitrogen); anti-Flag (M2, 1:1000, Sigma); rabbit anti-Clu (1:1000, a kind gift from Li Hui Goh); mouse anti-VCP (1:1000, a kind gift from Michael Buszczak) (91); rabbit anti-Ubiquitin (P4D1, 1:1000, Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-p62 (1:3000, a kind gift from Gábor Juhász) (60); mouse; rabbit anti-Atg8a (1:1000, a kind gift from Katja Köhler) (92); rabbit anti-Marf (1:1000, a kind gift from Alexander Whitworth) (20); anti-α-Tubulin (1:10 000, B-512, Sigma); mouse anti-ATPase 5α (1:10 000, Mitosciences), followed by incubation with Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000–1:5000, GE Healthcare) and detection using the ECL Plus western blotting detection system (Pierce).

Immunostaining

Third instar larvae were live dissected in modified HL3 buffer (70 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 20 mm MgCl2, 10 mm NaHCO3, 115 mm sucrose and 5 mm Hepes, pH 7.2) and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. For adult IFMs, thoraces from 4-day-old flies were bisected in cold PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 30 min. Transfected S2 cells were plated on slides coated with 0.5 mm concanavalin A. Cells were then incubated with DMSO or CCCP in complete medium as indicated, followed by fixation in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min. Primary antibodies used were: mouse anti-ATPase 5α (1:400, Mitosciences); rabbit anti-ATPase 5α (1:400, Mitosciences); guinea pig anti-Clu (1:2000) (35); rabbit anti-Parkin (1:1000, a kind gift from Alexander Whitworth) (20); mouse anti-Myc (9E10, 1:800); rabbit anti-Ubiquitin (1:1000, Abcam); rabbit anti-p62 (1:2000). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 568 or Alexa Fluor 647 (1:400, Molecular Probes).

JC-1 staining and TUNEL assay

For JC-1 staining, thoraces of 4-day-old adult flies were bisected in HL3 buffer and incubated with 20 μm JC-1 (Molecular Probes) in HL3 for 10 min. After three washes with HL3, IFMs were imaged after excitation at 488 nm (green) and 555 nm (red). The ratio of red to green intensity was quantified using ImageJ. For TUNEL assays, thoraces of 4-day-old adult flies were bisected in cold PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, permeabilized and blocked in PBST (0.1% Triton X-100) with 10% BSA. After blocking, TUNEL staining was performed using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Switzerland).

Transmission electron microscopy

Dissected L3 larvae were fixed in a paraformaldehyde/glutaraldehyde solution in a sodium cacodylate buffer, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, stained with uranyl acetate and dehydrated. After infiltration with resin, the samples were sectioned and photographed on a Tecnai G2 Spirit TEM in the electron microscopy facility at the Nanotechnology Innovation Center of Kansas State (NICKS).

Survival analyses

GFP balancers were used to maintain all stocks for survival analyses and lack of GFP was used to select chromosomes containing mutant or UAS-RNAi insertions. Flies of the indicated genotype were kept in small cages supplied with yeast paste on apple juice agar plates. One hundred embryos of each genotype were selected to track the number of viable animals at each developmental stage. The larval stages were determined according to the size of animals. After eclosion of the first adult, the rest of the pupae were kept for an additional 4 days to determine eclosion. The numbers of pupae utilized for determining adult eclosion are indicated in each figure legend.

Larval locomotion assays

Staged L3 larvae of the appropriate genotypes were placed on a fresh apple juice agar plate (35 mm diameter) for 15 min to acclimate to their surroundings. Videos of larval mobility were recorded for 1 min and transformed into time-lapse images (200 frames/min). The Grid plugin of ImageJ was utilized to add lines on the time-lapse images (area per point = 150 pixels2). The number of grids that larva crawled through was recorded and converted into velocity (distance/time).

Confocal imaging and statistics

Fluorescent images were collected on a Zeiss 700 confocal system with single sections as follows: z = 0.5 μm, 5–6 μm total for 20×; z = 0.4 μm, 4–5 μm total for 40×; and z = 0.35 μm, 3–4 μm total for the 63× objective. Maximum intensity projections of confocal z-stacks were processed using ImageJ software (NIH). All images were assembled into figures using Adobe Illustrator. Colocalization images were obtained on two single-step images from each staining by using ‘Colocalization’ plugin in ImageJ. For quantitation of western blots, densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ and normalized to either the levels of α-tubulin or ATPase 5α. All experiments were repeated at least three independent times and averaged for quantitation. Raw data were imported into Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) for the generation of graphs and statistical analysis. All error bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using either Student's t-tests or ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05 and are indicated in each figure legend.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant (R01 AR060788) to E.R.G. and UMKC School of Graduate Studies research grant (KDF41) to Z.W.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rachel Cox, Catherine Rabouille, Li Hui Goh, Michael Buszczak, Gábor Juhász, Katja Köhler, Alexander Whitworth and Yuh Nung Jan for their generous contribution of reagents to complete this study. We also thank the Bloomington Stock Center at Indiana University and Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) for fly stocks. We also thank Cheryl Clark, David Brooks, Nicole Green and Vishal Kumar in the Geisbrecht lab for discussions.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Dodson M.W., Guo M. (2007) Pink1, Parkin, DJ-1 and mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol., 17, 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke W.J. (2002) Recent advances in the genetics and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurology, 59, 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narendra D., Walker J.E., Youle R. (2012) Mitochondrial quality control mediated by PINK1 and Parkin: links to parkinsonism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol., 4, a011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valente E.M., Abou-Sleiman P.M., Caputo V., Muqit M.M., Harvey K., Gispert S., Ali Z., Del Turco D., Bentivoglio A.R., Healy D.G. et al. (2004) Hereditary early-onset Parkinson's disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science, 304, 1158–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitada T., Asakawa S., Hattori N., Matsumine H., Yamamura Y., Minoshima S., Yokochi M., Mizuno Y., Shimizu N. (1998) Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature, 392, 605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra P., Chan D.C. (2014) Mitochondrial dynamics and inheritance during cell division, development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 15, 634–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn G.W., Clark C.F., Eschenbacher W.H., Kang M.Y., Engelhard J.T., Warner S.J., Matkovich S.J., Jowdy C.C. (2011) MARF and Opa1 control mitochondrial and cardiac function in Drosophila. Circ. Res., 108, 12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham A.H., Meng S., Chu Q.N., Chan D.C. (2012) Loss of Mfn2 results in progressive, retrograde degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal circuit. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 4817–4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H., McCaffery J.M., Chan D.C. (2007) Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell, 130, 548–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kageyama Y., Hoshijima M., Seo K., Bedja D., Sysa-Shah P., Andrabi S.A., Chen W., Höke A., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M. et al. (2014) Parkin-independent mitophagy requires Drp1 and maintains the integrity of mammalian heart and brain. EMBO J., 33, 2798–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berthet A., Margolis E.B., Zhang J., Hsieh I., Hnasko T.S., Ahmad J., Edwards R.H., Sesaki H., Huang E.J., Nakamura K. (2014) Loss of mitochondrial fission depletes axonal mitochondria in midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci., 34, 14304–14317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark I.E., Dodson M.W., Jiang C., Cao J.H., Huh J.R., Seol J.H., Yoo S.J., Hay B.A., Guo M. (2006) Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature, 441, 1162–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park J., Lee S.B., Lee S., Kim Y., Song S., Kim S., Bae E., Kim J., Shong M., Kim J.M. et al. (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature, 441, 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y., Gehrke S., Imai Y., Huang Z., Ouyang Y., Wang J.W., Yang L., Beal M.F., Vogel H., Lu B. (2006) Mitochondrial pathology and muscle and dopaminergic neuron degeneration caused by inactivation of Drosophila Pink1 is rescued by Parkin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 10793–10798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng H., Dodson M.W., Huang H., Guo M. (2008) The Parkinson's disease genes pink1 and parkin promote mitochondrial fission and/or inhibit fusion in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 14503–14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y., Ouyang Y., Yang L., Beal M.F., McQuibban A., Vogel H., Lu B. (2008) Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 7070–7075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poole A.C., Thomas R.E., Andrews L.A., McBride H.M., Whitworth A.J., Pallanck L.J. (2008) The PINK1/Parkin pathway regulates mitochondrial morphology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 1638–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka A., Cleland M.M., Xu S., Narendra D.P., Suen D.F., Karbowski M., Youle R.J. (2010) Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J. Cell Biol., 191, 1367–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole A.C., Thomas R.E., Yu S., Vincow E.S., Pallanck L. (2010) The mitochondrial fusion-promoting factor mitofusin is a substrate of the PINK1/parkin pathway. PLoS One, 5, e10054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ziviani E., Tao R.N., Whitworth A.J. (2010) Drosophila parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates mitofusin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 5018–5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickrell A.M., Youle R.J. (2015) The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron, 85, 257–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuda N., Sato S., Shiba K., Okatsu K., Saisho K., Gautier C.A., Sou Y.S., Saiki S., Kawajiri S., Sato F. et al. (2010) PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol., 189, 211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narendra D.P., Jin S.M., Tanaka A., Suen D.F., Gautier C.A., Shen J., Cookson M.R., Youle R.J. (2010) PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol., 8, e1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N.C., Tresse E., Kolaitis R.M., Molliex A., Thomas R.E., Alami N.H., Wang B., Joshi A., Smith R.B., Ritson G.P. et al. (2013) VCP is essential for mitochondrial quality control by PINK1/Parkin and this function is impaired by VCP mutations. Neuron, 78, 65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan N.C., Salazar A.M., Pham A.H., Sweredoski M.J., Kolawa N.J., Graham R.L., Hess S., Chan D.C. (2011) Broad activation of the ubiquitin–proteasome system by Parkin is critical for mitophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet., 20, 1726–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhandari P., Song M., Chen Y., Burelle Y., Dorn G.W. (2014) Mitochondrial contagion induced by Parkin deficiency in Drosophila hearts and its containment by suppressing mitofusin. Circ. Res., 114, 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomes L.C., Scorrano L. (2013) Mitochondrial morphology in mitophagy and macroautophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta., 1833, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomes L.C., Di Benedetto G., Scorrano L. (2011) During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat. Cell Biol., 13, 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacVicar T.D., Lane J.D. (2014) Impaired OMA1-dependent cleavage of OPA1 and reduced DRP1 fission activity combine to prevent mitophagy in cells that are dependent on oxidative phosphorylation. J. Cell Sci., 127, 2313–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song M., Mihara K., Chen Y., Scorrano L., Dorn G.W. (2015) Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts. Cell Metab., 21, 273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank M., Duvezin-Caubet S., Koob S., Occhipinti A., Jagasia R., Petcherski A., Ruonala M.O., Priault M., Salin B., Reichert A.S. (2012) Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim. Biophys. Acta., 1823, 2297–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scarffe L.A., Stevens D.A., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M. (2014) Parkin and PINK1: much more than mitophagy. Trends Neurosci., 37, 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashrafi G., Schlehe J.S., LaVoie M.J., Schwarz T.L. (2014) Mitophagy of damaged mitochondria occurs locally in distal neuronal axons and requires PINK1 and Parkin. J. Cell Biol., 206, 655–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Winter D., Ashrafi G., Schlehe J., Wong Y.L., Selkoe D., Rice S., Steen J., LaVoie M.J., Schwarz T.L. (2011) PINK1 and Parkin target Miro for phosphorylation and degradation to arrest mitochondrial motility. Cell, 147, 893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox R.T., Spradling A.C. (2009) Clueless, a conserved Drosophila gene required for mitochondrial subcellular localization, interacts genetically with parkin. Dis. Model Mech., 2, 490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fields S.D., Conrad M.N., Clarke M. (1998) The S. cerevisiae CLU1 and D. discoideum cluA genes are functional homologues that influence mitochondrial morphology and distribution. J. Cell Sci., 111, 1717–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao J., Schatton D., Martinelli P., Hansen H., Pla-Martin D., Barth E., Becker C., Altmueller J., Frommolt P., Sardiello M. et al. (2014) CLUH regulates mitochondrial biogenesis by binding mRNAs of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial proteins. J. Cell Biol., 207, 213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z.H., Rabouille C., Geisbrecht E.R. (2015) Loss of a Clueless–dGRASP complex results in ER stress and blocks Integrin exit from the perinuclear endoplasmic reticulum in Drosophila larval muscle. Biol. Open, 4, 636–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sen A., Damm V.T., Cox R.T. (2013) Drosophila clueless is highly expressed in larval neuroblasts, affects mitochondrial localization and suppresses mitochondrial oxidative damage. PLoS One, 8, e54283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen A., Kalvakuri S., Bodmer R., Cox R.T. (2015) Clueless, a protein required for mitochondrial function, interacts with the PINK1–Parkin complex in Drosophila. Dis. Model Mech., 8, 577–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goh L.H., Zhou X., Lee M.C., Lin S., Wang H., Luo Y., Yang X. (2013) Clueless regulates aPKC activity and promotes self-renewal cell fate in Drosophila lgl mutant larval brains. Dev. Biol., 381, 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vornlocher H.P., Hanachi P., Ribeiro S., Hershey J.W. (1999) A 110-kilodalton subunit of translation initiation factor eIF3 and an associated 135-kilodalton protein are encoded by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae TIF32 and TIF31 genes. J. Biol Chem., 274, 16802–16812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitchell S.F., Jain S., She M., Parker R. (2013) Global analysis of yeast mRNPs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 20, 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y., Nishimura I., Imai Y., Takahashi R., Lu B. (2003) Parkin suppresses dopaminergic neuron-selective neurotoxicity induced by Pael-R in Drosophila. Neuron, 37, 911–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greene J.C., Whitworth A.J., Kuo I., Andrews L.A., Feany M.B., Pallanck L.J. (2003) Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 4078–4083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z.H., Clark C., Geisbrecht E.R. (2015) Analysis of mitochondrial structure and function in the drosophila larval musculature. Mitochondrion, 26, 33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vos M., Esposito G., Edirisinghe J.N., Vilain S., Haddad D.M., Slabbaert J.R., Van Meensel S., Schaap O., De Strooper B., Meganathan R. et al. (2012) Vitamin K2 is a mitochondrial electron carrier that rescues pink1 deficiency. Science, 336, 1306–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vincow E.S., Merrihew G., Thomas R.E., Shulman N.J., Beyer R.P., MacCoss M.J., Pallanck L.J. (2013) The PINK1–Parkin pathway promotes both mitophagy and selective respiratory chain turnover in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 6400–6405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rana A., Rera M., Walker D.W. (2013) Parkin overexpression during aging reduces proteotoxicity, alters mitochondrial dynamics, and extends lifespan. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 8638–8643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saini N., Oelhafen S., Hua H., Georgiev O., Schaffner W., Büeler H. (2010) Extended lifespan of Drosophila parkin mutants through sequestration of redox-active metals and enhancement of anti-oxidative pathways. Neurobiol. Dis., 40, 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M. (2000) Oxidative stress and genetics in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis., 7, 240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenner P., Olanow C.W. (1996) Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neurology, 47, S161–S170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vincent A., Briggs L., Chatwin G.F., Emery E., Tomlins R., Oswald M., Middleton C.A., Evans G.J., Sweeney S.T., Elliott C.J. (2012) Parkin-induced defects in neurophysiology and locomotion are generated by metabolic dysfunction and not oxidative stress. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 1760–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu S., Lu B. (2010) Reduction of protein translation and activation of autophagy protect against PINK1 pathogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet., 6, e1001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chazotte B. (2011) Labeling mitochondria with JC-1. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc., 2011, doi:10.1101/pdb.prot065490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Narendra D., Tanaka A., Suen D.F., Youle R.J. (2008) Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol., 183, 795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yun J., Puri R., Yang H., Lizzio M.A., Wu C., Sheng Z.H., Guo M. (2014) MUL1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway in regulating mitofusin and compensates for loss of PINK1/parkin. Elife, 3, e01958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zacharogianni M., Gomez A.A., Veenendaal T., Smout J., Rabouille C. (2014) A stress assembly that confers cell viability by preserving ERES components during amino-acid starvation. Elife, 3, e04132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klionsky D.J. (2014) Coming soon to a journal near you — the updated guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy, 10, 1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pircs K., Nagy P., Varga A., Venkei Z., Erdi B., Hegedus K., Juhasz G. (2012) Advantages and limitations of different p62-based assays for estimating autophagic activity in Drosophila. PLoS One, 7, e44214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klionsky D.J., Abdalla F.C., Abeliovich H., Abraham R.T., Acevedo-Arozena A., Adeli K., Agholme L., Agnello M., Agostinis P., Aguirre-Ghiso J.A. et al. (2012) Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy, 8, 445–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeVorkin L., Gorski S.M. (2014) Genetic manipulation of autophagy in the Drosophila ovary. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc., 2014, 973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krick R., Bremer S., Welter E., Schlotterhose P., Muehe Y., Eskelinen E.L., Thumm M. (2010) Cdc48/p97 and Shp1/p47 regulate autophagosome biogenesis in concert with ubiquitin-like Atg8. J. Cell Biol., 190, 965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partridge J.J., Lopreiato J.O., Latterich M., Indig F.E. (2003) DNA damage modulates nucleolar interaction of the Werner protein with the AAA ATPase p97/VCP. Mol. Biol. Cell, 14, 4221–4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartolome F., Wu H.C., Burchell V.S., Preza E., Wray S., Mahoney C.J., Fox N.C., Calvo A., Canosa A., Moglia C. et al. (2013) Pathogenic VCP mutations induce mitochondrial uncoupling and reduced ATP levels. Neuron, 78, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ritson G.P., Custer S.K., Freibaum B.D., Guinto J.B., Geffel D., Moore J., Tang W., Winton M.J., Neumann M., Trojanowski J.Q. et al. (2010) TDP-43 mediates degeneration in a novel Drosophila model of disease caused by mutations in VCP/p97. J. Neurosci., 30, 7729–7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ju J.S., Fuentealba R.A., Miller S.E., Jackson E., Piwnica-Worms D., Baloh R.H., Weihl C.C. (2009) Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is required for autophagy and is disrupted in VCP disease. J. Cell Biol., 187, 875–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye Y., Meyer H.H., Rapoport T.A. (2001) The AAA ATPase Cdc48/p97 and its partners transport proteins from the ER into the cytosol. Nature, 414, 652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]