Abstract

HLA-A , -B and -C alleles of 285 individuals, representing three Iranian Lur populations and one Iranian Kurd population were sequenced completely, yielding HLA class I genotypes at high resolution and filling four fields of the official HLA nomenclature. Each population has 87–99 alleles, evenly distributed between the three HLA class I genes, 145 alleles being identified in total. These alleles were already known, named and deposited in the HLA database. The alleles form 316 different HLA A-B-C haplotypes, with each population having between 80 and 112 haplotypes. The four Iranian populations form a related group that is distinguished from other populations, including other Iranians. All four KIR ligands - the A3/11, Bw4, C1 and C2 epitopes - are well represented, particularly Bw4, which is carried by three high-frequency allotypes: HLA-A*24:02, HLA-A*32:01 and HLA-B*51:01. In the Lur and Kurd populations, between 82% and 94% of individuals have the Bw4 epitope, the ligand for KIR3DL1. HLA-B*51:01 is likely of Neandertal origin and associated with Behcet’s disease, also known as the Silk Road disease. The Lordegan Lur have the highest frequency of HLA-B*51:01 in the world. This allele is present on 46 Lur and Kurd haplotypes. Present at lower frequency is HLA-B*51:08, which is also associated with Behcet’s disease. In the four Iranian populations, 31 haplotypes encode both Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B, a dual combination of Bw4 epitopes that is relatively rare in other populations, worldwide. This study both demonstrates and emphasizes the value of studying HLA class I polymorphism at highest resolution in anthropologically well-defined populations.

Keywords: Bw4 epitope, HLA Class I polymorphism, HLA-B*51:01, High-throughput sequencing, Lur and Kurd populations

Introduction

The lands of contemporary Iran provided routes through which the continents of Asia and Europe were first colonized by modern humans migrating out of Africa (1). Subsequently these same routes were used by a succession of human invasions originating either in Europe or Asia (2). Although providing a physical barrier for migration, the Zagros mountains in southern and south-western Iran (Figure 1) have been inhabited by humans for some 40,000 years (3). The first inhabitants were Elamites, followed by Kassites and then the Medes and Persians (4). The fourth wave of human migration into the Zagros mountains was made by Lurs, over 2000 years ago. Around 1000 years ago they split into linguistically distinctive Lurs and Kurds (5, 6). Originally nomadic and pastoral, the Lurs were settled during the last 150 years and they now constitute one of the largest minority populations in Iran, numbering ~5–8 million people. The region they inhabit, named Luristan in the tenth century, corresponds to the modern Iranian provinces of Chaharmahaal and Bakhtiari, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, part of Fars (Mamasani), Ilam and Lorestan.

Figure 1. Map of Iran showing the regions inhabited by the Kurd, Lorestan, Lordegan and Yasuj populations.

The Kurd ethnic group live in Kurdistan province as indicated on the map. Circles show where the four populations reside. The Zagros Mountains extend from the northwest of Iran to the southwest. The thin lines on the map show the boundaries of the Iranian provinces.

Previous studies examined mitochondrial DNA and HLA class II diversity in the Yasuj and Lorestan Lur populations and a Kurd population (Figure 1 map), showing their close relationship (7, 8). In addition, these studies indicated a genetic affinity of the Lur and Kurd with other Iranians ethnics, Macedonians, Greeks, and Italians. The mitochondrial DNA analysis also showed the Yasuj has some similarity to Arabs and Persians, not seen for Lorestan and Kurd (9). In the study described here we have defined at high resolution HLA class I variation in the same Kurd, Yasuj and Lorestan populations, as well as a third Lur population, Lordegan (Figure 1). This was achieved by using a novel high-throughput method of HLA class I typing based upon next generation sequencing (10).

Material and Methods

Ethical statement

Sample collection was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences as part of another study. All participants gave their informed consent. Banked and de-identified samples were used for this study.

Study populations

DNA samples from a total of 285 individuals representing four different Iranian populations from the Lur and Kurd ethnic groups were analyzed. Demographic information, regarding language and parental place of birth, was collected from all individuals at the time the samples were collected. For each individual, at least two previous generations belonged exclusively to the identified ethnic group. A total of 229 Lur: comprising 66 Lordegan (Province of Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, city of Lordegan), 84 Yasuj (province of Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, city of Yasuj) and 79 Lorestan (province of Lorestan) and 56 Kurd (province of Kurdistan) were genotyped using high throughput sequencing as described previously (10). The Lur populations inhabit the central and southern parts of the Zagros Mountains and are considered aboriginal groups with nomadic, pastoral habits (11). The Kurds inhabit the northern Zagros area and had little admixture with the various invading populations. The Lurs and Kurds are closely related peoples; but they speak different languages (5).

High resolution HLA class I typing by high throughput sequencing

Library preparation

The protocol was based on the Truseq Nano method for library preparation (Illumina Inc. San Diego, CA). For each individual studied, 300ng genomic DNA was sheared into 800bp fragments using a Covaris S220 instrument (Covaris, Woburn, MA). The library preparation was then performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the following three modifications: Following end-repair, volumes of 70.2ul sample purification beads and 89.8ul H2O were used. In the final PCR setup, the 72°C extension time was 90s.

Isolation of HLA-A, -B and -C gene fragments from libraries

Isolation of DNA fragments from libraries corresponding to the HLA-A, -B and -C genes was performed using a modified version of the Nextera Rapid Capture enrichment protocol (Illumina Inc. San Diego, CA). Subsets of biotinylated capture probes were designed and made as described previously (10). Each hybridization mix (100ul) contained twelve uniquely indexed sequencing libraries (500ng each), 50pM of biotinylated capture probes and hybridization buffer (CT3, Illumina). The hybridization mix was heated to 95°C for 10min and then gradually cooled, 2°C per cycle, to 58°C and then incubated at 58°C for an additional 90min. Afterward, the libraries were bound to 100ul of streptavidin magnetic beads (SMB beads) in the course of a 30min agitation at 1000rpm on a plate shaker at room temperature.

A magnetic separator was used to remove the beads from the excess unhybridized probes. The beads were then washed twice with 200ul of a high salt, non-stringent buffer (EWS, Illumina Inc.) at 50°C for 30min. After washing, the beads were exposed to 21ul of 0.1 N NaOH (HP3, EE1, Illumina Inc.) to separate and elute the DNA libraries from the magnetic beads. After removal of the beads, the solution was neutralized by the addition of 4ul of ET2 buffer (Illumina Inc.). The neutralized DNA was then subjected to another round of enrichment, consisting of hybridization, followed by washing, elution and neutralization. The protocol was the same as in the first round, except that during the hybridization step the mix was incubated at 58°C overnight (for at least 14.5hr and no more than 24hr), instead of for 90min (10).

10ul of the twice-eluted enriched DNA were subject to PCR amplification in a 50ul reaction mix containing Illumina library-specific primers and Illumina PCR mixture. PCR cycling was performed as follows: 98°C for 30s, 17 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s, and a final elongation of 5min at 72°C. Amplified material was purified with 40ul of Sample Purification beads and eluted in 30ul of resuspension buffer (RSB, Illumina Inc.).

DNA Sequencing

Paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp), using 48 samples per run, was performed using a MiSeq instrument with V3 chemistry (Illumina Inc. San Diego, CA).

Data analysis

Any reads which mapped to HLA-Y, which is always linked to an HLA-A*02:05, -A*30:01, -A*31:01, -A*33:01 or -A*68:02 allele (12, 13), were removed using filtering and scripting as described (10). The identities of HLA class I alleles were determined using NGSengine 1.7.0 (GenDX software, Utrecht, NL), kindly provided by Wietse Mulder and Erik Rozemuller. All samples flagged for inspection were processed using filters that remove all contaminating reads that originate from HLA class I pseudogenes or HLA class II genes (10), and were then reanalyzed with the NGSengine software.

Population genetics

The allele frequency of each HLA class I allele in the four Iranian populations was determined by direct counting. The differences between individual allele frequencies were calculated using Fisher’s Exact tests. Significance (p) values are given in one of three categories: p<0.05, p<0.01 or p<0.001. Haplotype frequencies were predicted based on implementation of the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm using Arlequin 3.5.2 software (14). A complete list of the HLA A-B-C haplotypes identified in the four Iranian populations is given in Supplementary Figure 1. A summary of the haplotypes that are shared by the populations and haplotypes that distinguish the populations are given in Supplementary Figure 2.

Principal component analysis was performed on the HLA-A, -B, and -C allele frequencies of 106 populations, comprising 102 worldwide populations described previously (15) and the four Iranian populations studied here, using the FactoMineR package implemented in the R program language (16). Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) was performed on the same data set, using incorporated data embedded in all dimensions and then projected in two dimensions, using the t-SNE package implemented in the R program language. The results of t-SNE are given in Supplementary Figure 3.

The Watterson’s homozygosity F test and normalized deviate of homozygosity (Fnd) were calculated as described previously (17). The expected Hardy-Weinberg homozygosity was calculated based on allotype frequencies for a given HLA class I motif using the test described by Slatkin (18) and implemented in the Pypop software package (19). A significant negative Fnd value was considered to be evidence for balancing selection; a significant positive Fnd value was considered to be evidence for directional selection.

Results

We studied a total of 285 individuals, representing four ethnically and geographically distinguishable Iranian populations. These comprised one population of Kurds (n=56) and three populations of Lurs: Lordegan (n=66), Yasuj (n=84), and Lorestan (n=79). Samples of genomic DNA were genotyped for HLA-A, -B and -C at high resolution, to four fields of the official HLA nomenclature (20), using the next generation sequencing method of Norman et al (10).

The Lur and Kurd populations have high HLA-A, -B and -C diversity

In the four Iranian populations, we identified a total of 145 HLA class I alleles (Figure 2). These comprise 49 HLA-A alleles (Figure 2A), 55 HLA-B alleles (Figure 2B) and 41 HLA-C alleles (Figure 2C). All of the alleles had been identified previously. The allele distributions of each gene were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE).

Figure 2. Very high HLA-A, -B, -C polymorphism in the Lur and Kurd populations.

Shown are the allele frequencies of HLA-A, -B, -C in the four Iranian populations studied here: the Lordegan (2n=132), Yasuj (2n=168) and Lorestan (2n=158) Lur poulations and Kurd (2n=112).

HLA-A

Of the 49 HLA-A alleles, 14 are common to the four populations and they contribute 80% of the HLA-A alleles in the combined population; 21 of the HLA-A alleles were identified in only one of the four populations, and 14 alleles were identified in either two or three of the populations (Figure 2A). HLA-A*24:02:01:01, -A*02:01:01:01, -A*03:01:01:01 and A*32:01:01 alleles have worldwide distributions and in the Iranian populations they are four of the 14 common HLA-A alleles. In Kurds, Lordegan and Yasuj HLA-A*24:02:01:01, -A*02:01:01:01, -A*03:01:01:01 and A*32:01:01 account for 50% of the frequency contributed by the 14 common alleles; in Lorestan they account for 37.6% of the frequency, a reduction that is principally due to a lower frequency of A*32:01:01.

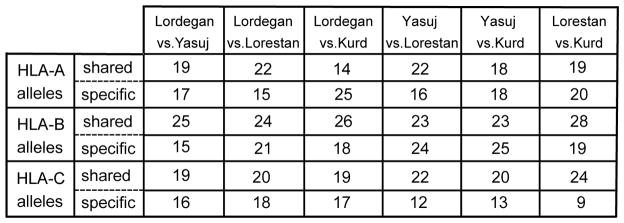

With frequencies of 17.2–22.6%, HLA-A*24:02:01:01 is the most common HLA-A allele in each of the four Iranian populations. The results from pairwise comparisons made among the four populations, shows that a greater number of HLA-A alleles are shared by the three Lur populations (19–22 HLA-A alleles), than is shared by the Lur and Kurd populations (14–19 HLA-A alleles) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Sharing of HLA-A, -B and -C alleles by Lur and Kurd populations.

Shown for each gene, and for each pairwise comparison of two populations, are the number of alleles that are common to the two populations (shared) and the number of alleles that are present in only one of the two populations (specific).

HLA-B

Similar analysis of HLA-B allele frequencies showed that the three Lur populations had 23–25 HLA-B alleles in common, compared to the 23–28 HLA-B alleles that are shared by Kurd and Lur populations. Of the 55 HLA-B alleles identified in the four Iranian populations, 15 of them are present in only one of the four populations. In contrast, nineteen of the HLA-B alleles are common to the four populations (Figure 2B) and these represent 80% of the total number of HLA-B alleles. In Lordegan, five alleles (B*18:01:01:02; B*38:01:01; B*41:01:01; B*51:01:01; B*52:01:01:01) account for 56.1% of the HLA-B alleles, compared to their combined frequencies of 24.2–30.5% in the other three populations. The higher combined frequency in the Lordegan is due largely to the higher frequency of B*51:01:01 in this population: 28% compared to 10.8–18.5% in the other three populations (Figure 2B). The common and widely distributed B*40:06:01:02 allele has significantly higher frequency in the Yasuj (6.5%) than in the Lordegan (1.5%) and Kurd (0.9%) populations (Yasuj vs. Kurd, p<0.05). An even greater difference is the absence of this allele from the Lorestan population. The Lorestan and Kurd populations have the highest number, 28, of HLA-B alleles in common (Figure 3).

HLA-C

The Lorestan and Kurd populations also have the highest number of HLA-C alleles in common. Of the 41 HLA-C alleles we identified, 24 are common to the Lorestan and Kurd populations. Seventeen of the HLA-C alleles are common to all four populations (Figure 2C), and these represent 80% of the HLA-C alleles. The common and widespread HLA-C*04:01:01:01 allele is the most frequent HLA-C allele in all four Iranian populations (Figure 2C). The lower frequency of 10.6% in Lordegan was significantly different from the higher frequencies of 20.2% in Yasuj (p< 0.05) and 23.4% in Lorestan (p<0.01). The highest frequency, that of 27.7% in the Kurd population, was significantly greater than the frequencies in the three Lur populations (p<0.001). Also, the Lordegan have a significantly higher frequency of HLA-C*14:02:01 than the Lorestan (p<0.001).

In summary, all four Iranian populations are seen to have a high diversity of HLA-A, -B and -C alleles. For each gene, there is a small number of alleles that have high frequencies in all four populations, and a large number of alleles that have low frequencies, and differ between the four populations. In terms of allele numbers, the HLA-A, -B and -C diversity seen in these Iranian populations is comparable to that seen in sub-Saharan African populations (15).

Comparison of HLA class I frequencies in Iranians and other populations

To compare the HLA-A, -B and -C class I frequencies with those in 102 other populations, worldwide, we performed a principal component analysis (Figure 4). Although other major population groups were separated to considerable extent, there are overlaps between them at the boundaries. The HLA class I profiles of the Iranian Lur and Kurd populations are most closely related to each other, consistent with their population histories. Moreover, they are distinguished in their HLA class I frequencies from other Iranian population, such as Balochs. The Iranian Lurs and Kurd population form a loose group with Georgians and Georgian Kurds, Arab Druze and Moroccan and Israel Jews, consistent with Iran’s place as a major crossroads in the history of human migration and population (Figure 4). We also performed t-SNE analysis (Supplemental figure 3) and multidimensional scaling analysis (data not shown) on the same data and they gave similar results and distribution to that obtained by PCA analysis.

Figure 4. Placing the Lur and Kurd populations in a global context of HLA-A, -B and -C diversity.

(A). Shows the results of principal component analysis (PCA) of the Lur, Kurd and 102 other populations using previously described methods (15). Dimension 1 (dim1) accounts for 11.58% of the total variance and dimension 2 (dim2) accounts for an additional 5.87%. The data point for each population is colored according to their geographical region of origin: Amerindian: (AME) pink; Europe (EUR) blue; North Africa (NAF) violet; Northeast Asia (NEA) dark red; Oceania (OCE) green; Southeast Asia (SEA) orange; Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) yellow; Southwest Asia (SWA) olive. The labels for Individual populations are GK Georgian Kurdish, GK; Georgian, GE; Moroccan-Jews (MJ); Israeli Jews (IJ); North Africans resident in Paris, France (NAP); Arab Druze (AD); Iranian Baloch (BL); Iranian Lordegan Lur (LL); Iranian Lorestan Lur (LR); Iranian Yasuj Lur (LY) and Iranian Kurd (KU).

(B). Shows the distribution of variance explained by principal component.

Limited evidence for selection on HLA class I polymorphism in Iranians

For HLA-A, -B and -C, the sites of functional interactions with peptide, T cell receptors, CD8 co-receptors and KIR were analyzed for evidence of selection in the Kurd and Lur populations. The methods used were those of Norman et al (15). The allele distribution of each motif was calculated using the Ewens-Watterson test of neutrality and the division of neutrality was calculated using normalized division of the homozygosity (Fnd) (21). Each set of HLA motifs analyzed was shown to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

For HLA-A, there was no evidence for selection (data not shown). For HLA-B (Figure 5B), there is evidence of weak, directional selection for all binding sites in the Lordegan, but not the other Lur and the Kurd populations. This effect, which is not statistically significant, is caused by the unusually high frequency of HLA-B*51 in this population. These results contrast with those obtained from other populations (Figure 5B). For Ghanaians, KhoeSan, Europeans and Japanese there is evidence for strong balancing selection on the peptide-binding site and also on the KIR-binding site of Ghanaians (15). For HLA-C, there is evidence of balancing selection at the TCR binding site in the Lordegan, but not in any other of the populations analyzed (Figure 5A). If the four Iranian populations are combined then balancing selection at the peptide-binding site of HLA-C is detected (Figure 5A). That selection is seen for the peptide-binding motifs but not for the whole HLA-C molecule (All in Figure 5A) shows that these functional sites are acting independently of the rest of the molecule.

Figure 5. Balancing selection on the TCR binding motif of HLA-C in the Lordegan population.

(A). Shown are normalized deviate values of Ewens-Watterson’s F test (Fnd) for polymorphic sequence motifs that influence the binding of HLA-C allotypes to peptide, TCR, KIR and CD8 motifs in the Lur and Kurd populations. The Fnd analysis was performed using the amino acid sequence for each binding motif of HLA class I alleles (15). (p value was calculated using the exact test).

(B). Represents the Fnd value of HLA-B motifs in the Lur and Kurd populations with the other major global populations described previously (15). No evidence of balancing selection on these motifs was found in the Lur and Kurd populations. The colors indicate different p values as shown in the color key. ALL: complete polypeptide sequence; A hyphen (−) indicates the motif is monomorphic.

KIR ligands are well represented in the Lur and Kurd populations

Five types of KIR ligand are well represented in the Kurd and Lur populations (Figure 6). These comprise HLA-A3/11, Bw4+HLA-A, Bw4+HLA-B, C1+HLA-C and C2+HLA-C. A rare sixth KIR ligand, C1+HLA-B, is present in three individuals: C1+HLA-B*73:01 in one Lordegan individual and one Yasuj individual, and C1+HLA-B*46:01:01 in one Kurd individual (Figures 2B and 6).

Figure 6. Distribution in the Lur and Kurd populations of the KIR ligands carried by HLA-A, -B and -C allotypes.

Shows the allotype frequencies in the four Iranian populations of the six HLA class I epitopes recognized by KIR.

An even balance between the C1 and C2 epitopes is seen, particularly in the Kurd and Lorestan populations. Furthermore, the frequencies of Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B are higher than in many other populations. In particular, the 59.1% allotype frequency of Bw4+HLA-B in Lordegan is unusually high and significantly different from the frequencies of 33.9% in the Yasuj (p<0.001), 44.3% in Lorestan (p<0.05) and 39.3% in Kurd (p<0.01) (Figure 6).

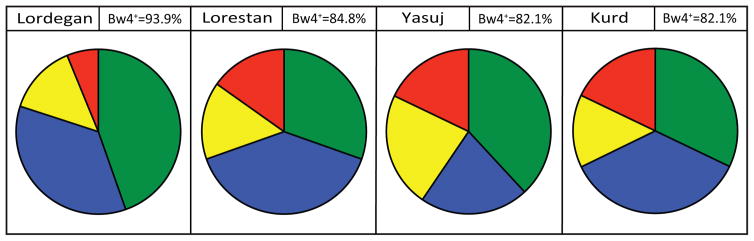

In combining Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B, we observe that a majority of individuals have the Bw4 epitope (Figure 7). Of the 66 Lordegan individuals studied 62 of them (93.9%) carry at least one Bw4 epitope.

Figure 7. Distribution of the Bw4 epitope in four Iranian populations.

The pie charts show the phenotype frequency of Bw4 epitopes in each population. In this analysis both Bw4+ HLA-A and Bw4+ were included and treated equivalently. The colored segments of the pie chart show the phenotype frequencies of Bw4+HLA-A plus Bw4+HLA-B (green); Bw4+HLA-B without Bw4+HLA-A (blue); Bw4+HLA-A without Bw4+HLA-B (yellow) and absence of Bw4 (red). For each population the phenotypic frequency of Bw4 is given in the box next to that containing the name of the population.

Lordegan Lur have the highest frequency of HLA-B*51 worldwide

The high frequency of Bw4+HLA-B in the Lordegan, compared to the other three populations, is due to an elevated frequency of HLA-B*51:01:01, the only HLA-B*51:01 allele present in these populations. The HLA-B*51:01 allotype is present at frequencies of 28.0% in the Lordegan, 18.5% in the Yasuj, 10.8% in the Lorestan (p<0.001) and 11.6% in Kurds (p<0.01). Consequently, the phenotype frequency of HLA-B*51:01 in the Lordegan is 50% and significantly greater than the 32.5% in Yasuj (p<0.05), 19% in Lorestan (p<0.001) and 23% in Kurd (p<0.001) (Figure 8A and 8B). HLA-B*51:01 is a globally widespread allele, being particularly prominent in the Mediterranean region, the Middle East and Asia (Figure 8C). Comparison with other populations, shows that the frequency of B*51:01 in the Lordegan is the highest worldwide and an outlier of the distribution shown in Figure 8B.

Figure 8. Global distribution of HLA-B*51.

(A). Gives the phenotype frequencies of HLA-B*51:01 in the four Iranian populations: Lordegan (LL), Yasuj (LY), Lorestan (LR) and Kurd (KU). (*p<0.05,**p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

(B). Histogram showing the frequency distribution of the B*51:01 allele in 176 populations (53). Indicated by arrows are the bars containing the four Iranian populations and the Ghanaians (G), British Caucasians (UK) Japanese (J) and Bulgarians (B). The populations were selected for being represented by >40 individuals and for being anthropologically well defined. Populations that lack HLA-B*51:01 were excluded from the analysis.

(C). Shows the global distribution of the HLA-B*51 allotype. Each colored circle represents one population studied. The colors give the frequencies, as indicated by the scale at the bottom of the panel. The region where the Lur and Kurd populations reside is indicated by the black arrow, and surrounded by the dark blue ellipse. HLA-B*51 frequencies were obtained from a panel of 208 populations described previously (52).

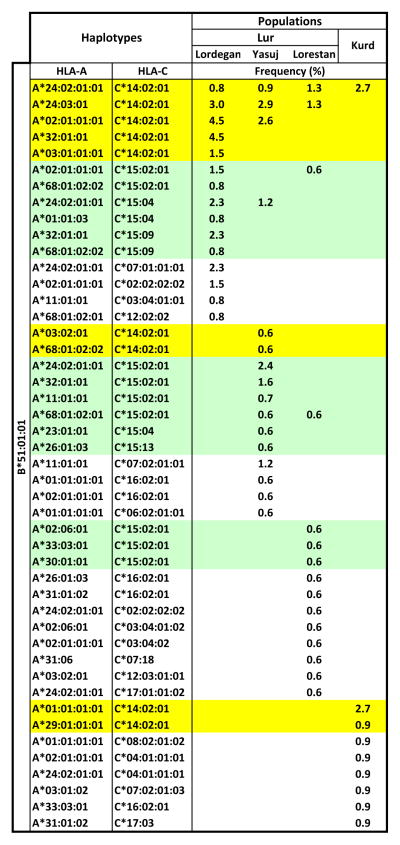

In the Kurd and Lur populations HLA-B*51:01:01 is present on 46 different HLA haplotypes. Of these, only one is present in all four populations (A*24:02, B*51:01, C*14:02) and only one other (A*24:023, B*51:01, C*14:02) is present in three populations, four are common to two populations and 40 are specific to just one of the populations: 10 in Lordegan, 11 in Yasuj, 11 in Lorestan and 8 in Kurds (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Diversity of HLA haplotypes containing HLA-B*51:01:01 in the Lur and Kurd populations.

Shows the diversity and frequency distributions of B*51-containing HLA haplotyes in the four populations, as estimated using the EM algorithm. Green and yellow shading indicate those haplotypes having HLA-C*15 and HLA-C*14:02:01 alleles, respectively.

Lurs and Kurds have diverse haplotypes encoding Bw4+ HLA-A and Bw4+ HLA-B

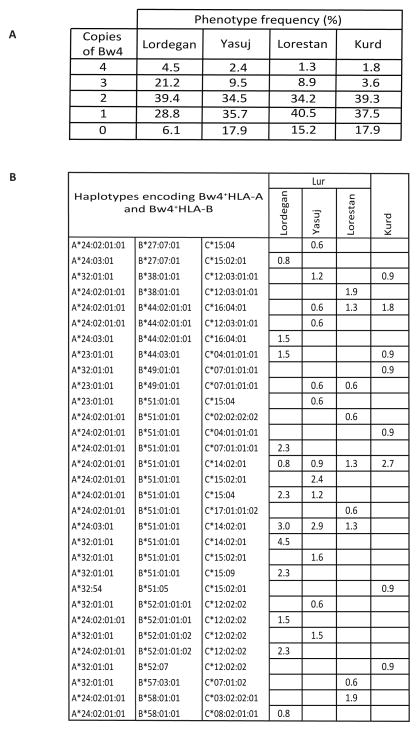

The haplotype shared by all four populations is characterized by having Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B, as is the haplotype shared by the three Lur populations and Kurds. The frequency of haplotypes having Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B varies considerably between the Lordegan (23.5%), Yasuj (15.1%), Lorestan (10.1%) and Kurd (9.8%). Thus the increased frequency of Bw4 in the Lordegan is mainly due to the rise in frequency of haplotypes providing two copies of the Bw4 epitope. As a consequence 25.7% of Lordegan individuals have genomes encoding three or four copies of the Bw4 epitope, whereas that is only the case for <12% of individuals in the other three populations (Figure 10A).

Figure 10. Distribution of the Bw4 epitope in Lur and Kurd populations.

(A). Shows the phenotype frequencies of individuals having different numbers Bw4 epitopes in the four Iranian populations.

(B). Shows the subset of haplotypes that encode both Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B and their frequencies in the four populations.

In the four Iranian populations we identified 31 different HLA-A, -B and -C haplotypes that encode both Bw4+ HLA-A and Bw4+ HLA-B. Contributing to this haplotype diversity are five HLA-A, twelve HLA-B and fourteen HLA-C alleles (Figure 10B). A large majority of these haplotypes, 24, are specific to one of the four populations, whereas four are present in two populations, two are present in three, and one is present in all four. These associations involve six C2+ and eight C1+ HLA-C allotypes.

Discussion

This study applied high throughput, next-generation sequencing to define HLA class I polymorphism at high resolution in three Lur populations and one Kurd population, who reside in the Zagros Mountains of Iran. Although these minority Iranian populations have an impressively high HLA-A, -B and -C polymorphism, it was surprising that no novel alleles were discovered in the course of this study. Thus the sequences of all 49 HLA-A, 55 HLA-B and 41 HLA-C alleles we identified in these Iranians had been described previously. These results attest to the extent the HLA class I database now covers the breadth and depth of human MHC class I polymorphism; they are also a reflection of Iran’s history, as a major crossroads of human migration routes, as well as an important region where populations of archaic and modern humans once coexisted and socially interacted.

Although more closely related to each other than to other populations, the Lur and Kurd populations have distinctive combinations of HLA-A, -B and -C alleles, but similar numbers, 87–99, of HLA class I alleles. These numbers exceed the 81 HLA-A, -B and -C alleles we identified in a Ghanaian population (15), Sub-Saharan Africans who are generally considered to have the highest genome diversity worldwide (22). At the other end of the spectrum are South Amerindians, such as the Yucpa of Venezuela, who have a total of 19 HLA-A, -B and -C alleles (23).

A striking feature of the Lur and Kurd populations is the abundance of HLA-A, -B and -C allotypes that function as KIR ligands. Of particular note is the Bw4 epitope, which has phenotypic frequencies of 82.1–93.9% in the four populations. Major contributions to this elevated level of Bw4 are made by the high frequencies of HLA-B*51, HLA-A*24 and HLA-A*32. Of these three allotypes, HLA-B*51 is of special interest, because of its association with Behçet’s disease, a systemic inflammatory disorder, and its increase prevalence along the Silk Road, a trading route of ancient origin that connected the Mediterranean region, through Iran and central Asia to China and Japan (24).

Correlation of the HLA-B*51 antigen with Behçet’s disease was first reported in 1982 (25) and has been confirmed in numerous subsequent studies (26–28). As is often the case for HLA-associated inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, the debate surrounding Behçet’s disease has centered on whether HLA-B*51 contributes directly to the disease-causing mechanism, or is merely an uninvolved marker for a linked gene that is the real culprit. Although much of the genetic evidence is consistent with HLA-B*51 being the primary risk factor for Behçet’s disease (29, 30), in 2013 a study based on deep-sequencing and imputation reported on “The identification of multiple independent susceptibility loci in the HLA region in Behçet’s disease”’ and concluded that “the robust HLA-B*51 association in Behçet’s disease is explained by a variant located between the HLA-B and MICA genes.”(31). Consistent with this study is a study by Xavier et al of Iranian Behçet’s patients (32). Such differences in the analysis and interpretation of the genetic association with Behçet’s disease have yet to be resolved.

With widespread distribution and relatively high frequencies throughout the world, a case can be made that HLA-B*51 is the most successful of the HLA-B allotypes. As we report here, HLA-B*51 reaches its highest frequency in the Lordegan Lur population. HLA-B*51 has an allele frequency of 31% in the Lordegan: with 28% of that contributed by B*51:01:01 and 3.0% by B*51:08:01. The HLA-B*51 frequencies in the three other Iranian populations are also substantial and on the high side of the global distribution of HLA-B*51 frequencies: 19.7% in Yasuj Lur, 11.4% in Lorestan Lur and 14.3% in Kurd. Although Behçet’s disease has been well correlated with B*51 in Iranian populations (33), to our knowledge there is no study that has focused specifically on Behçet’s disease in the Lur and Kurd populations.

Comparison of HLA-B*51:01 with other HLA-B allotypes, has shown that B*51:01 has several distinctive properties that could account for its success and prevalence in so many human populations. These same properties may also be responsible for the role of HLA-B*51:01 in causing Behçet’s disease. One characteristic of HLA-B*51:01 is that it assembles more slowly in vitro than other HLA-B allotypes (34), and this is reflected in vivo, where HLA-B*51:01 is highly dependent on tapasin for its exit from the endoplasmic reticulum and translocation to the cell surface (35–37). When the three dimensional structure of HLA-B*51:01 was compared to structures of the serologically related HLA-B*35:01 and HLA-B*53:01 allotypes, the substitution of histidine for tyrosine at position 171 was seen to have a dramatic effect on the conformation of the bound peptide (38). Histidine 171 effects a substantial change in the position of the amino-terminal residue, which causes the peptide to be drawn more deeply into the binding groove. Maenaka et al also attributed the slow in vitro assembly of HLA-B*51:01 (34) to the presence of histidine at position 171.

HLA-B*51:02, which only differs from B*51:01 by having tyrosine 171, was not associated with Behçet’s disease in Japanese patients (39) suggesting that histidine 171 could be a factor in the cause of disease. Four HLA-B*51 subtypes were identified in all Lur and Kurd populations and all four have histidine 171. HLA-B*51:01 and B*51:08 are both present in the four populations and have both been associated with Behçet’s disease in Iranians (40), Turks (41), Greeks (42), Italians (43) and Germans including those of Turkish origin (44). HLA-B*51:05, which we found only in the Kurd, has been detected in Behçet’s patients (44) and B*51:09, found only in Yasuj Lur, is associated with the disease in Turkish patients (45). HLA-B*51:01, -B*51:08, -B*51:09 differ at positions 152 and 156 in the a2 domain. At these positions, HLA-B*51:01 has an E-L motif, HLA-B*51:08 has a V-D motif and HLA-B*51:09 has a V-L motif. HLA-B*51:05 has a V-R motif at position 152 and 156 combined with substitution of tyrosine for histidine at position 171 (46).

That HLA-B*51 carries the Bw4 epitope and has high frequency means that B*51 accounts for a substantial proportion of the Bw4 epitopes in the Lur and Kurd populations. That B*51 is a good ligand for KIR3DL1 (47, 48) raises the possibility that education and regulation of NK cells by the interaction of B*51 with KIR3DL1 may in some way contribute to Behcet’s disease (49). It will therefore be of interest to study the KIR genes of Lur and Kurd and explore the co-evolution of their KIR3DL1 alleles with HLA-B*51 and other Bw4-bearing HLA-A and HLA-B. Like the allelic polymorphism, there is a high diversity of HLA A-B-C haplotypes in the Lur and Kurd populations: 83 in Lordegan, 98 in Yasuj, 112 in Lorestan, 80 in Kurd, and a total of 274 different haplotypes in the combined population. For example, HLA-B*51:01 is present on 46 different haplotypes, and 31 different haplotypes encode both Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B. This latter observation contrasts with the situation in most human populations worldwide, where haplotypes encoding both Bw4+HLA-A and Bw4+HLA-B are rare (50).

All three of the Neandertals for whom genome sequences were determined (51) carried HLA-B*51, as well as HLA-B*07 (52). The Neandertal allele could either have been HLA-B*51:01 or HLA-B*51:08. Both these alleles are associated with Behçets disease and are present in the Lur and Kurd populations studied here. The results of simulations that tested for introgression, support the model that modern human population inherited HLA-B*51:01 or HLA-B*51:08 (or both) from Neandertals. In the context of this model, HLA-B*51-associated Behçets disease could have been a secondary and undesirable consequence of the immunological advantages conferred by HLA-B*51 in activating NK cells and CD8 T cells in response to life-threatening infectious disease. The high frequency of HLA-B*51 in the Lur and Kurd populations, particularly the Lordegan, plus the high diversity of HLA-B*51-encoding HLA haplotypes point to a persisting long-term benefit of this enigmatic HLA-B allotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI7892. We thank those who helped us to collect the samples. EA, PP, PJN, AG designed the study. EA, PJN, LAG, ASH, NNG and SJN generated the data. All authors contributed to writing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Lahr MM, Foley RA. Towards a theory of modern human origins: geography, demography, and diversity in recent human evolution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;(Suppl 27):137–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8644(1998)107:27+<137::aid-ajpa6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalli-Sforza LL. The spread of agriculture and nomadic pastoralism: insights from the genetics, linguistics and archaeology. In: Harris DR, editor. The origins and spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. London: University College London press; 1996. pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hole F. Pastoral nomadism in Western Iran: Explorations in Ethnoarchaeology. University of New Mexico Press; 1978. pp. 127–167. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zvelebil M. The rise of the nomads in Central Asia. In: Sherratt A, editor. The Cambridge encyclopedia of archaeology. New York: Crown; 1980. pp. 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunter MM. Historical Dictionary of the Kurds. 2. Scarecrow Press; 2011. p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frye RN. The Golden age of Persia. Phoenix Press; 2000. pp. 111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farjadian S, Ota M, Inoko H, Ghaderi A. The genetic relationship among Iranian ethnic groups: an anthropological view based on HLA class II gene polymorphism. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:1943–50. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farjadian S, Ghaderi A. Iranian Lurs Genetic Diversity: An Anthropological View Based on HLA Class II Profiles. Iranian journal of immunology : IJI. 2006;3:106–13. doi: 10.22034/iji.2006.16983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farjadian S, Sazzini M, Tofanelli S, et al. Discordant patterns of mtDNA and ethno-linguistic variation in 14 Iranian Ethnic groups. Hum Hered. 2011;72:73–84. doi: 10.1159/000330166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman PJ, Hollenbach JA, Nemat-Gorgani N, et al. Defining KIR and HLA class I Genotypes at Highest Resolution Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.023. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amanollahi-Baharvand S. The Lurs: Investigation of tribal relation and geographical distribution of the Lurs in Iran. Tehran: Agah; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman PJ, Norberg SJ, Nemat-Gorgani N, et al. Very long haplotype tracts characterized at high resolution from HLA homozygous cell lines. Immunogenetics. 2015;67:479–85. doi: 10.1007/s00251-015-0857-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe Y, Tokunaga K, Geraghty DE, Tadokoro K, Juji T. Large-scale comparative mapping of the MHC class I region of predominant haplotypes in Japanese. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:135–41. doi: 10.1007/s002510050252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3. 5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Molecular ecology resources. 2010;10:564–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman PJ, Hollenbach JA, Nemat-Gorgani N, et al. Co-evolution of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I ligands with killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) in a genetically diverse population of sub-Saharan Africans. PLoS genetics. 2013;9:e1003938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008;25:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solberg OD, Mack SJ, Lancaster AK, et al. Balancing selection and heterogeneity across the classical human leukocyte antigen loci: a meta-analytic review of 497 population studies. Human Immunology. 2008;69:443–64. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slatkin M. An exact test for neutrality based on the Ewens sampling distribution. Genetical Research. 1994;64:71–4. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300032560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancaster AK, Single RM, Solberg OD, Nelson MP, Thomson G. PyPop update--a software pipeline for large-scale multilocus population genomics. Tissue antigens. 2007;69(Suppl 1):192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00769.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh SG, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, et al. Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 2010. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75:291–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watterson GA. The homozygosity test of neutrality. Genetics. 1978;88:405–17. doi: 10.1093/genetics/88.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324:1035–44. doi: 10.1126/science.1172257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gendzekhadze K, Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, et al. Co-evolution of KIR2DL3 with HLA-C in a human population retaining minimal essential diversity of KIR and HLA class I ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18692–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906051106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verity DH, Wallace GR, Vaughan RW, Stanford MR. Behcet’s disease: from Hippocrates to the third millennium. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1175–83. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohno S, Ohguchi M, Hirose S, Matsuda H, Wakisaka A, Aizawa M. Close association of HLA-Bw51 with Behcet’s disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100:1455–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030040433013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Menthon M, Lavalley MP, Maldini C, Guillevin L, Mahr A. HLA-B51/B5 and the risk of Behcet’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control genetic association studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1287–96. doi: 10.1002/art.24642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gul A. Genetics of Behcet’s disease: lessons learned from genomewide association studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:56–63. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatemi G, Seyahi E, Fresko I, Talarico R, Hamuryudan V. Behcet’s syndrome: a critical digest of the 2014–2015 literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace GR. HLA-B*51 the primary risk in Behcet disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8706–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407307111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ombrello MJ, Kirino Y, de Bakker PI, Gul A, Kastner DL, Remmers EF. Behcet disease-associated MHC class I residues implicate antigen binding and regulation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8867–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406575111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes T, Coit P, Adler A, et al. Identification of multiple independent susceptibility loci in the HLA region in Behcet’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:319–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xavier JM, Davatchi F, Abade O, et al. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex locus association with Behcet’s disease in Iran. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:81. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davatchi F, Chams-Davatchi C, Shams H, et al. Adult Behcet’s disease in Iran: analysis of 6075 patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19:95–103. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chersi A, Garzillo C, Butler RH, Tanigaki N. Allele- and temperature-dependency of in vitro HLA class I assembly. Human Immunology. 2001;62:858–68. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(01)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geironson L, Thuring C, Harndahl M, et al. Tapasin facilitation of natural HLA-A and -B allomorphs is strongly influenced by peptide length, depends on stability, and separates closely related allomorphs. J Immunol. 2013;191:3939–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizvi SM, Salam N, Geng J, et al. Distinct assembly profiles of HLA-B molecules. J Immunol. 2014;192:4967–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raghavan M, Geng J. HLA-B polymorphisms and intracellular assembly modes. Mol Immunol. 2015;68:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maenaka K, Maenaka T, Tomiyama H, Takiguchi M, Stuart DI, Jones EY. Nonstandard peptide binding revealed by crystal structures of HLA-B*5101 complexed with HIV immunodominant epitopes. J Immunol. 2000;165:3260–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizuki N, Inoko H, Ando H, et al. Behcet’s disease associated with one of the HLA-B51 subantigens, HLA-B* 5101. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:406–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizuki N, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, et al. HLA class I genotyping including HLA-B*51 allele typing in the Iranian patients with Behcet’s disease. Tissue Antigens. 2001;57:457–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057005457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirim I, Atasoy M, Ikbal M, Erdem T, Aliagaoglu C. HLA class I and class II genotyping in patients with Behcet’s disease: a regional study of eastern part of Turkey. Tissue antigens. 2004;64:293–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuki N, Ota M, Katsuyama Y, et al. Sequencing-based typing of HLA-B*51 alleles and the significant association of HLA-B*5101 and -B*5108 with Behcet’s disease in Greek patients. Tissue Antigens. 2002;59:118–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2002.590207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kera J, Mizuki N, Ota M, et al. Significant associations of HLA-B*5101 and B*5108, and lack of association of class II alleles with Behcet’s disease in Italian patients. Tissue Antigens. 1999;54:565–71. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.1999.540605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotter I, Gunaydin I, Stubiger N, et al. Comparative analysis of the association of HLA-B*51 suballeles with Behcet’s disease in patients of German and Turkish origin. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:166–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.580304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demirseren DD, Ceylan GG, Akoglu G, et al. HLA-B51 subtypes in Turkish patients with Behcet’s disease and their correlation with clinical manifestations. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:4788–96. doi: 10.4238/2014.July.2.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsh SGE, Parham P, Barber LD. The HLA FactsBook. London: Academic Press; 2000. p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gumperz JE, Litwin V, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Parham P. The Bw4 public epitope of HLA-B molecules confers reactivity with natural killer cell clones that express NKB1, a putative HLA receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1133–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanjanwala B, Draghi M, Norman PJ, Guethlein LA, Parham P. Polymorphic sites away from the Bw4 epitope that affect interaction of Bw4+ HLA-B with KIR3DL1. J Immunol. 2008;181:6293–300. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petrushkin H, Hasan MS, Stanford MR, Fortune F, Wallace GR. Behcet’s Disease: Do Natural Killer Cells Play a Significant Role? Front Immunol. 2015;6:134. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norman PJ, Abi-Rached L, Gendzekhadze K, et al. Unusual selection on the KIR3DL1/S1 natural killer cell receptor in Africans. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1092–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abi-Rached L, Jobin MJ, Kulkarni S, et al. The shaping of modern human immune systems by multiregional admixture with archaic humans. Science. 2011;334:89–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1209202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gonzalez-Galarza FF, Takeshita LY, Santos EJ, et al. Allele frequency net 2015 update: new features for HLA epitopes, KIR and disease and HLA adverse drug reaction associations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D784–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.