Abstract

In proteins, empirical correlations have shown that changes in heat capacity (ΔCP) scale linearly with the hydrophobic surface area buried upon folding. The influence of ΔCP on RNA folding has been widely overlooked and is poorly understood. In addition to considerations of solvent reorganization, electrostatic effects might contribute to ΔCPs of folding in polyanionic species such as RNAs. Here, we employ a perturbation method based on electrostatic theory to probe the hot and cold denaturation behavior of the hammerhead ribozyme. This treatment avoids much of the error associated with imposing two-state folding models on non-two-state systems. Ribozyme stability is perturbed across a matrix of solvent conditions by varying the concentration of NaCl and methanol co-solvent. Temperature-dependent unfolding is then monitored by circular dichroism spectroscopy. The resulting array of unfolding transitions can be used to calculate a ΔCP of folding that accurately predicts the observed cold denaturation temperature. We confirm the accuracy of the calculated ΔCP by using isothermal titration calorimetry, and also demonstrate a methanol-dependence of the ΔCP. We weigh the strengths and limitations of this method for determining ΔCP values. Finally, we discuss the data in light of the physical origins of the ΔCPs for RNA folding and consider their impact on biological function.

INTRODUCTION

Thermal unfolding studies generally reflect the denaturation of biological macromolecules at high temperature, but macromolecules also can be unfolded by decreasing temperature in a phenomenon called cold denaturation. Protein cold denaturation is well studied (1), and results from an increase in the heat capacity of the unfolded state relative to the native, folded state. The change in heat capacity (ΔCP) correlates with the amount of hydrophobic surface area buried upon protein folding (2). The Gibbs–Helmholtz equation incorporates the free energy contribution of the ΔCP as shown in and Equations 1, and 2 graphically in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Plot of −ΔGfold versus temperature for a hypothetical RNA. ΔG was calculated as a function of ΔCP by using Equation 2 to illustrate the effect of non-zero heat capacities on RNA stability. The solid line corresponds to a −ΔCPfold = 0. The dashed and dotted lines show the progressive increase in curvature up to a −ΔCPfold of 3.4 kcal mol−1 K−1. For the purposes of this figure, ΔHref = −123 kcal mol−1, ΔSref = −374 cal mol−1 K−1 and Tref = 329 K.

![]()

![]()

In the absence of a ΔCPfold, the free energy of folding is linear as a function of temperature; ΔGfold = 0 at exactly one point, which corresponds to the conventional melting transition midpoint (TM). However, as ΔCP increases, the stability plot becomes parabolic. Thus, ΔGfold = 0 at two points, corresponding to the hot and cold TMs (TH and TC, respectively). Clearly, ignoring the contribution of ΔCPfold can lead to the overestimation of stability at reduced temperature.

The parameters commonly used to predict RNA and DNA duplex stability were obtained from melting studies that employed model duplexes with TMs typically in the vicinity of 50°C (3,4). Thus, these values are most accurate in predicting melting behavior around this temperature. It is convenient to use TH as the reference temperature (Tref) for a system, because at this temperature, the contribution of ΔCP to ΔG reduces to zero. As temperature deviates from Tref = TH, however, the error associated with neglecting ΔCP increases (Figure 1), especially at low temperatures.

It is frequently assumed that nucleic acid folding occurs with a negligible ΔCP (5–7). Despite some early studies by Petersheim and Turner (8) who measured ΔCPs for simple model systems, this practice is due in part to the historical difficulty of measuring ΔCPs with older calorimeters (9,10). Theoretical studies of DNA duplexes explored the possibility of nucleic acid cold denaturation in recent years (11,12) and reports of non-zero ΔCPs in nucleic acid folding have increased (13–18). By using a methanol–water co-solvent system originally designed for cryoenzymology (19), we recently demonstrated that the hammerhead ribozyme unfolds when exposed to low temperatures (20), providing conclusive evidence for large ΔCPs of folding in the RNA.

The ribozyme construct we used, hammerhead-16, is a well-studied bimolecular hammerhead (Figure 2). Two oligonucleotides anneal to form a three-way helical junction in which two helical stems coaxially stack, and a third stem docks to form the active site where self-cleavage occurs (21). Our construct featured a 2′-deoxy substitution at the cleavage site to prevent strand scission during the folding studies.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of hammerhead ribozyme 16 (HH16). The ribozyme strand is shown in solid lettering and the substrate strand is shown in outline. The arrow indicates the normal site of ribozyme cleavage, but all of the experiments described were performed with a non-reactive substrate analog containing a deoxyC residue at position 17.

As described in our previous work, two-state fits of the circular dichroism (CD) melting data were used to estimate a van't Hoff ΔCP of folding using the approximation ΔCP = (ΔHhot − ΔHcold)/(TH − TC). The cryo-solvent system used to collect these data (500 mM NaCl, 40% methanol, pH 6.6) lacks divalent cations. Under these conditions, the ribozyme has modest activity and the room temperature CD spectrum is similar to that observed in solutions containing 10 mM MgCl2 (22–24). The ΔCP was thus taken to pertain predominantly to secondary structure, and fell within the reported range for such values as calculated from both calorimetric (13,14) and optical (10,18) thermal melting data for nucleic acid duplexes. A growing database of ΔCPs associated with both secondary and tertiary folding of nucleic acids is emerging in the literature (Table 1). Understanding the ΔCP of folding for nucleic acids may not only benefit folding prediction algorithms (17,18,28), but also help us to investigate the possibility that biology has exploited ΔCPfold to regulate activity through structure.

Table 1. Recently reported heat capacities of folding for nucleic acids.

| Nucleic acid system | −ΔCP (kcal mol−1 K−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Hammerhead ribozyme | 3.4a, 1.0b | This study |

| Hammerhead ribozyme folding mutants | −0.7 − +0.8 | (16) |

| Hairpin ribozyme (docking) | 0.9 | (25) |

| Catalytic domain of thermophilic RNase P RNA | 2.5 | (15) |

| Catalytic domain of mesophilic RNase P RNA | 0.5 | (15) |

| Multi-branched junctions | 3.1 (average) | (17) |

| Duplex DNA | 0.04−0.2 bp−1 | (13,14,27) |

aValue measured by perturbation method in 35% MeOH and 400 mM NaCl.

bValue measured by ITC in the absence of methanol in 500 mM NaCl.

ΔCPs of folding are typically measured in one of two ways (29,30): (i) from van't Hoff ΔHs and TMs, obtained from optical melting data or (ii) from direct measurement via calorimetry. The two approaches often yield different results (10,13), spurring debate over the applicability of each method (31,32). The disparities may arise largely by imposing the two-state assumption implicit in the van't Hoff model onto optical melting data for systems exhibiting non-two-state thermal melting behavior, or from statistical artifacts from correlated errors in the fitting of ITC data. Thus, van't Hoff fits can yield erroneously small ΔHs of folding, with error propagating to the calculated ΔCP. The van't Hoff ΔCP previously calculated for the hammerhead almost certainly reflects such error; incorporating it into Equation 2 yields a calculated TC more than 50 K colder than the observed TC. The results obtained from optical data should be verified by calorimetry, but calorimetric experiments require large amounts of sample and specially modified instrumentation for work at sub-zero temperatures. Therefore, a robust method of calculating ΔCPs from optical data that avoids some of the pitfalls of van't Hoff analysis would be of great utility.

Previous work by Rouzina and Bloomfield (10) applied perturbation theory to this problem. In this method, thermodynamic parameters are calculated from the change in TM observed as conditions that vary from a reference state. The deviations in ΔH and ΔS are defined as the ‘perturbation enthalpy’, δH and ‘perturbation entropy’, δS, respectively. Notably, the analysis relies only on the fitted TMs of optical data, which are much less susceptible to fitting error than the corresponding fitted ΔHs. Here, we use a variation of the perturbation approach to analyze TC and TH data for the hammerhead ribozyme. By using just the transition TMs, we obtain a value for ΔCPfold more than 4-fold larger than the previously determined van't Hoff ΔCP. Significantly, when incorporated into Equation 2, this new ΔCP value accurately predicts the observed TC in the reference state.

Systematic deviations in the TC + TH sum from the behavior predicted by the perturbation model suggest that the methanol co-solvent perturbs ΔCP across the matrix of solution conditions. Therefore, we directly investigate the effect of methanol on the ΔCP of hammerhead folding by using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Our results confirm that the ΔCP is dependent on co-solvent, but also show that the ΔCP calculated from perturbation data accurately represents the value at the center of the perturbation matrix.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of hammerhead ribozyme for spectroscopy

Substrate (17mer) strands were prepared by chemical synthesis (Dharmacon Research, Inc.). The RNAs were deprotected according to the manufacturer's protocol, and resuspended in water. Purity was assessed by PAGE. Enzyme (38mer) strands were prepared by T7 transcription of a synthetic DNA template (33), gel purified and resuspended in water. RNA concentrations in stock solutions were determined from their absorbance at 260 nm. Spectroscopic samples were prepared by heat annealing the RNA in a buffer containing all components of the final sample except methanol. Annealing was performed at 95°C for 2 min, and the samples were allowed to cool slowly to room temperature. Methanol was added after cooling.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

CD data were collected on a Jasco J715 spectropolarimeter. TH data were collected in a 1 cm pathlength cell with temperature controlled by a Peltier device. High-temperature ramps were conducted at 1°C/min, and the data were collected for every 1°C. TC data were collected in a 1 mm pathlength cylindrical jacketed cell attached to a 90% methanol-circulating bath for temperature control. The actual temperature within the jacketed cell was monitored by means of a microscale thermocouple inserted into the cell through a sealed hole in a Teflon stopper. Low-temperature ramps were conducted at 8 min/°C, and the data were collected for every 1°C.

Fitting of the CD data

Single-wavelength traces of the CD data at 265 nm (the positive absorption maximum) were fit by least-squares minimization to a double-baseline model (Equation 3), where m and b are individual baseline slopes and intercepts, and α is the fraction of folded RNA. The parameter α relates to K for the two-state folding of a non-self-complementary bimolecular system (Equations 4 and 5), where CT is the total strand concentration (34). Non-two-state behavior registers significant error in the fitted enthalpy, but has comparatively little effect on the fitted TM, which was the only parameter used for subsequent analyses. Least-squares minimization was performed by using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Application of perturbation theory approach to measuring ΔCP of nucleic acid folding

By incrementally altering the concentrations of NaCl and methanol in sample solutions, we caused small perturbations in the enthalpy and entropy of ribozyme folding relative to the reference state (11), as expressed in Equations 6 and 7:

![]()

![]()

where δH and δS are the perturbations to enthalpy and entropy, respectively. Furthermore, if ΔCP is perturbed across the matrix, this parameter can also be expanded to include perturbation terms:

![]()

Substituting the modified expressions for ΔH and ΔS into the Gibbs equation, we obtain

Note that, in the absence of perturbations, Equation 9 is equivalent to Equation 2.

Each perturbation term can be further expanded (Equations 10–12) to reflect separate perturbations by NaCl and methanol as their respective concentrations deviate from those in the reference condition.

![]()

![]()

![]()

This treatment of the data makes the assumption that the ΔCP is itself independent of temperature. Whereas this assumption may not be rigorously correct, it is reasonable for conveniently estimating the magnitude of the ΔCP (35).

Global fitting of TH and TC data to the perturbation model

Since ΔGfold = 0 at TH and TC, one can perform a global analysis of the experimental dataset of measured melting temperatures using Equation 9 as expanded by Equations 10–12. This analysis can yield values for ΔHref, ΔSref and ΔCPref most consistent with the measurements. The set of experimental TC and TH values (22 data points in total) was globally fit to the perturbation model by using a non-linear least-squares algorithm (the Solver utility in Microsoft Excel software), minimizing ΔGfold. Three rounds of twenty fits each were performed. First, fits were performed constraining only ΔHref to a range of values determined from the concentration-dependence of TH (see Equation 13). Second, fits were performed constraining only ΔSref to a range of values also determined from the concentration-dependent changes in TH. Separately constraining ΔHref and ΔSref prevented the minimization algorithm from collapsing through mutual simultaneous minimization of ΔHref and ΔSref. Third, the average values for ΔCPref obtained in the previous two rounds of fitting were used in the third round, constraining only ΔCPref to −3.4 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1 K−1, while allowing other parameters to float. In each of the three rounds, the perturbation terms (δH, δS and δCP) were allowed to float up to 2% of the parent parameter (ΔHref, ΔSref and ΔCPref) per mM NaCl or %MeOH. Initial values for all parameters were randomized before each fit. Each round of 20 least-squares fits thus produced an average value and standard deviation for each parameter. The final values (ΔHfit, ΔSfit and ΔCPfit) represent the mean of the three independently fit values. Errors were estimated from the propagated standard deviation for each parameter.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC sample preparation and experiments were performed essentially as described in (36). All ITC samples contained 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl and 0–35% methanol. Where appropriate, methanol was added to samples after heat annealing and slow cooling. Titrations in the absence of methanol consisted of an initial 2 μl injection followed by ∼40 injections (at 7 μl per injection) of 75 μM substrate strand into a cell containing 1.4 ml of 5 μM enzyme strand. Titrations in the presence of methanol employed lower concentrations of RNA to prevent aggregation of uninjected substrate strand within the syringe. Each of these titrations consisted of an initial 2 μl injection followed by 20–30 injections (at 10–15 μl per injection) of 15 μM substrate strand into a cell containing 1.4 ml of 1 μM enzyme strand.

Analysis of raw ITC data

ITC data were fit by using ORIGIN software, version 7 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA). Raw injection data (in μcal s−1 versus time) were integrated to yield individual injection enthalpies. The integrated data for each injection were normalized by the moles of added titrant. Normalized injection ΔHs were plotted as a function of the molar ratio of titrant sample to cell sample. All experiments included many injections past saturation of the folding event, such that all datasets had a long upper baseline. This baseline reflected the enthalpic contributions of dilution and mixing as they actually occurred in each experiment. Therefore, these upper baselines were extrapolated back to the first injection and subtracted from the full dataset. The resulting plots were directly fit to a one-site binding model (37) to yield the reaction ΔH, KA and stoichiometry (n) of folding. For single-site binding, one ideally should observe n = 1; across all titrations of this study, n = 0.93 ± 0.06.

RESULTS

Thermal melting data for both the hot and cold melting transitions of the hammerhead ribozyme were collected by CD spectroscopy. Representative samples of the CD spectra for the cold transition are shown in Figure 3. At moderate temperatures, we observe an intense spectrum indicative of A-form helical structures with a strong positive maximum at ∼265 nm and a strong negative minimum at ∼210 nm. The 265 nm feature reports primarily on base stacking whereas the 210 nm band derives from backbone conformational transitions (38). As temperature decreases, both peaks undergo transitions that mirror one another, each peak decreasing in intensity towards the adichroic axis. Globally, spectra of the cold-denatured state resemble those obtained for the heat-denatured ribozyme (Figure S1 in Supplementary Material), consistent with general structural similarity between unfolded ribozyme at high and low temperatures, though rigorous structural characterization of the cold-denatured state remains to be done. Close inspection of the spectra reveals a slight redshift in the positive maximum as intensity decreases, a detail also observed in high-temperature unfolding experiments and consistent with unstacking of the nucleobases (39).

Figure 3.

Cold denaturation of HH16 observed by CD spectroscopy. Arrows indicate the decrease in CD intensity of the 265 and 210 nm features as temperature is lowered. CD spectra were collected at 1°C intervals between 15 and −30°C on a 0.7 OD sample of HH16 in 50 mM cacodylate, pH 6.6, 400 mM NaCl and 35% MeOH. Added methanol prevents freezing and shifts cold denaturation to accessible temperatures.

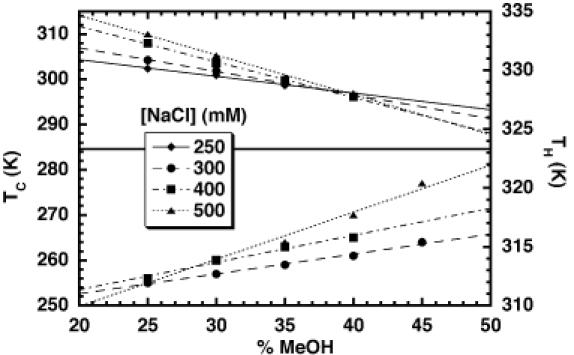

The spectra were fit to a van't Hoff model (see Materials and methods), but only the relatively error-insensitive TM (centroid of the transition) was used in subsequent analysis. Data were collected as a function of both the NaCl and methanol concentrations. The changes in solution dielectric and ionic strength provided the perturbations on both TC and TH required for the analysis (Figures 4 and 5). Conditions were chosen to keep the cold denaturation transition within the accessible window for the CD measurements. Near invariance of the TC + TH sum across perturbed solution conditions is expected when ΔCP >> ΔSref, conditions where cold denaturation could be observed. This predicted invariance arises from the highly parabolic relationship of ΔGfold with temperature in the presence of a large ΔCP, as observed in Figure 1. Stabilizing perturbations should shift TH to higher temperatures and TC to lower temperatures, whereas destabilizing perturbations should do the opposite. As long as solution perturbations are minute, the opposing effects on TH and TC should also be small. Across the matrix, one therefore expects opposing perturbations on TH and TC to mostly cancel with respect to the parent values, resulting in near invariance of the TC + TH sum. Failure to observe a relatively constant TC + TH sum would suggest that the observed TH and TC values do not actually report on the same kind of folding transition, and/or that the solution perturbations are sufficiently large that they significantly alter the transition endstates. Experimentally, the TC + TH sum averaged 591 K, with a range of 12 K and a standard deviation of ±3 K (Table 2). The 12 K range of TC + TH values across the matrix constitutes 2% of the average sum.

Figure 4.

Plot of the hot and cold denaturation temperatures (TH and TC, respectively) of HH16 versus the percentage of methanol co-solvent.

Figure 5.

Plot of the hot and cold denaturation temperatures (TH and TC, respectively) of HH16 versus the NaCl concentration.

Table 2. Observed TC and TH at various concentrations of NaCl and methanola.

| |

300 mM NaCl |

400 mM NaCl |

500 mM NaCl |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %MeOH | TC | TH | TC + TH | TC | TH | TC + TH | TC | TH | TC + TH |

| 25 | 255 | 330.9 | 586 | 256 | 332.3 | 588 | 256 | 333.1 | 589 |

| 30 | 257 | 330.0 | 587 | 260 | 330.6 | 591 | 260 | 331.2 | 591 |

| 35 | 259 | 328.9 | 588 | 263 | 329.1 | 592 | 264 | 329.4 | 593 |

| 40 | 261 | — | — | 265 | 327.8 | 593 | 270 | 328.0 | 598 |

aAll temperatures in K.

Methanol-dependence of TC and TH

The effect of methanol on the stability of nucleic acid duplexes has been studied previously and shown to have a linear effect on the high-temperature thermal denaturation behavior (40,41). Both the hot and cold unfolding transitions of the hammerhead ribozyme displayed a linear dependence on the concentration of methanol in the range studied (0–45%) (Figure 4). Methanol is therefore destabilizing with respect to both high- and low-temperature thermal denaturation. Over these concentrations, the dielectric constant of the methanol/water mixtures varies proportionally with the methanol concentration (41). Therefore, this experiment probably probes the effect of solvent dielectric on the folding equilibrium. Overall, TC displays a 2–3-fold greater methanol-dependence than the TH. The magnitude of the co-solvent effects on TH compare favorably with those previously measured for DNA duplex stability (40). The fact that the slopes are not identical for the high- and low-temperature transitions indicate that there is a minor deviation from the theoretical predictions of Rouzina and Bloomfield in that the sum TC + TH approximates a constant only over a limited range of methanol concentrations. These deviations are more pronounced at higher ionic strength and most probably reflect a systematic variation of ΔCP as a function of the methanol concentration. Alternatively, added methanol may affect the amount of residual structure in the unfolded state, producing methanol-dependent changes in the apparent ΔCP (42–44).

NaCl-dependence of TC and TH

The same dataset described above can also be used to analyze the denaturation temperature as a function of ionic strength. This analysis reveals that TH and TC for the hammerhead ribozyme both vary linearly with the log of the salt concentration (Figure 5). The usable range of ionic strengths was somewhat more limited than would be desired due to the competing needs of the system. Since these studies were performed in the absence of Mg2+, modestly high-ionic strength was required to promote the proper folding of the ribozyme (22,23,45). However, the incubation of RNAs at low temperature in methanol/water mixtures containing very high NaCl concentrations can lead to precipitation that would interfere with the measurements. Thus, our matrix represents a balancing act dictated by the glassing temperature of the solution and the physical properties of the RNA under these conditions.

In contrast to the methanol-dependence above, these trends exhibit slopes of the same sign for both TC and TH (Figure 5). NaCl exerts a stabilizing effect at high temperature but is destabilizing over this concentration range at low temperatures. The cold denaturation transition was slightly more sensitive to ionic strength than was high-temperature unfolding under the conditions tested. As with the methanol concentration dependence, this result reiterates the slight deviation from TC + TH being a constant over all conditions.

Determination of initial parameters Tref, ΔHref and ΔSref for the reference state

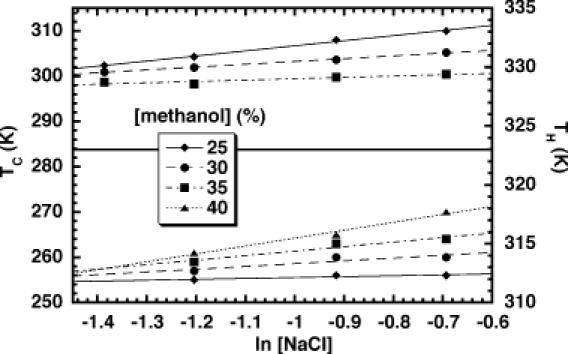

The selection of a convenient reference state is required if we wish to use the perturbation analysis to calculate ΔCP for the hammerhead ribozyme folding transition. We decided to use the high-temperature melting transition for samples at a central matrix condition (35% methanol and 400 mM NaCl) as the basis for our reference state. We collected initial ΔHref and ΔSref values for this state by using standard optical methods and measuring the RNA strand concentration-dependence of the TH. Thermal melting profiles for the hammerhead ribozyme were obtained across an 8-fold range of concentrations. The THs were plotted as a function of ln(CT/4), which reflects the fact that our hammerhead construct undergoes a bimolecular, non-self-complementary melting transition (46). The data were fit to a line (Figure 6). The reference enthalpy for folding, ΔHref = ΔH° = −133 ± 15 kcal mol−1, was extracted from the slope of that line according to Equation 13.

Figure 6.

Plot of 1/TH versus ln(CT/4) for HH16. As a bimolecular construct, the concentration dependence of TH can be used, together with Equation 13, to determine ΔHref and ΔSref for folding if one defines TH = Tref.

![]()

The linear fitting model assumes that ΔH does not vary as a function of temperature, and that changes in TM result from the entropic effects of changing strand concentration. Therefore, the fitted ΔHref is most valid within the temperature range covered by the observed TMs. The observed TH at the strand concentration used across the NaCl/methanol matrix was 329 K. Therefore, Tref was set at 329 K, and the hammerhead was calculated to fold with the transition entropy, ΔSref = ΔHref/Tref = −404 ± 45 cal mol−1 K−1.

Calculation of ΔCP and a predicted TC for hammerhead unfolding

The ΔCP for the unfolding transition was determined from global fitting of the matrix of TC and TH values to a perturbation form of the modified Gibbs equation (see Materials and methods). A total of 60 rounds of fitting were performed starting from randomized initial values, and independently constraining ΔH, ΔS and ΔCP while allowing other parameters to float. The refined parameters, ΔHfit = −123 ± 5 kcal mol−1, ΔSfit = −374 ± 16 cal mol−1 K−1 and ΔCPfit = −3.4 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 K−1, represent average values from all fits to the matrix of melting temperatures. ΔHfit and ΔSfit are in good agreement with the values obtained by the traditional methods described above. Notably, THfit = Tref = 329K, even though ΔHfit and ΔSfit were fit independently. ΔCPfit is more than 4-fold larger than the one previously calculated using van't Hoff methods at a single condition (20). This new value is also 9-fold greater than ΔSfit, consistent with a scenario in which the ΔCP exerts significant effects on the overall thermodynamics of folding. If the fitted ΔCP is incorporated into Equation 2 along with ΔHfit and ΔSfit, one obtains a TCcalc of 262 ± 8 K. This value nearly matches the TC observed under the reference conditions, 263 ± 1 K. Thus, the global analysis methodology produces appropriate values to describe the folding behavior of the system.

Systematic deviation of individual TC + TH sums from the average

Inspection of the data shown in Table 2 revealed an incremental increase in the individual TC + TH sums as one moves from low methanol, low-salt conditions to high methanol, high-salt conditions. The sums for conditions at the center of the matrix were closest to the average value. Changes in methanol concentration seemed to have a larger effect on TC + TH than did changes in the NaCl concentration. Moreover, the effect of changes in NaCl concentration appears magnified by increases in methanol concentration. These observations suggest that methanol might be perturbing the ΔCP of folding in addition to ΔH and ΔS. We therefore directly probed the effect of methanol on the ΔCP of hammerhead folding by using ITC.

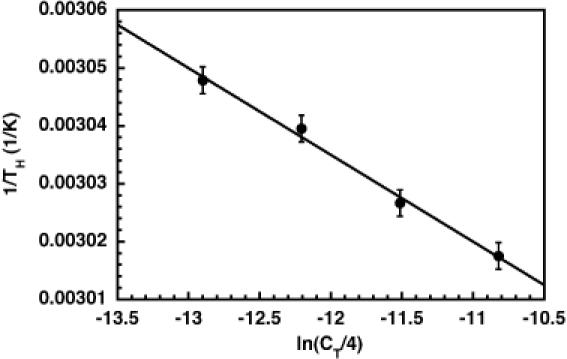

Calorimetric determination of ΔCP and its methanol-dependence

To support further the efficacy of the perturbation method in measuring ΔCP, we used ITC. Enthalpies for folding of the bimolecular HH16 ribozyme were obtained from the ITC experiments, an example of which is shown in Figure 7. The data were fit by a non-linear least-squares method (solid line in Figure 7, lower panel) to a one-site binding model (37), yielding experimental values for ΔH, KA and n, the reaction stoichiometry.

Figure 7.

Representative data from an ITC experiment. A 15 μM HH16 substrate strand was titrated into 1.4 ml of 1 μM enzyme strand. Both RNA samples were in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl and 25% methanol. The titration was performed in a VP-ITC calorimeter thermostatted at 40°C. The upper panel shows the raw injection data, and the lower panel shows the integrated injection enthalpies after background correction. The solid line in the lower panel represents a fit of the data to a one-site binding model, yielding the following experimental parameters: ΔH = −112 kcal mol−1, KA = 1.2 × 108 M−1 and n = 0.97. Note that KA values in excess of ∼108 cannot be accurately determined by this method.

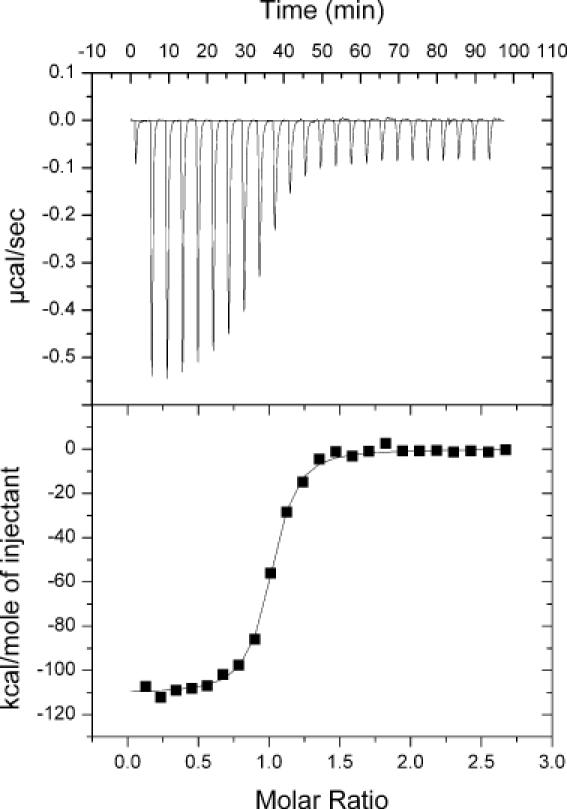

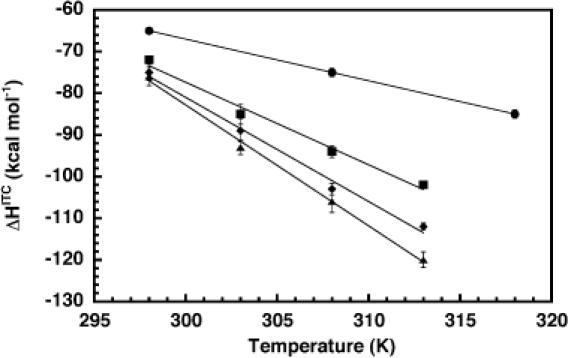

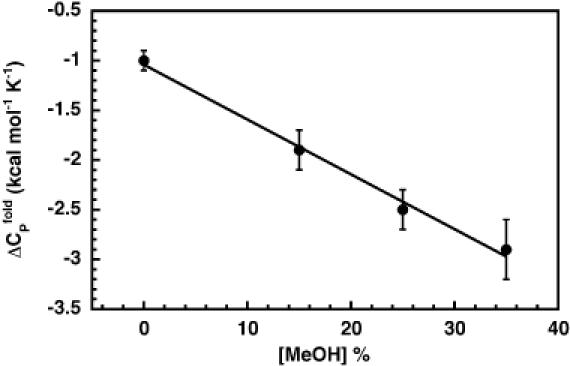

The results of the ITC experiments are shown in Figure 8. The temperature-dependence of ΔH was linear at all methanol concentrations, and became more pronounced as the percentage of methanol was increased from 0 to 35%. These data demonstrate that the ΔCP of hammerhead folding is in fact perturbed by methanol. The slopes of linear fits to the data in Figure 8 (solid lines) represent the ΔCP at each methanol concentration, and were used to quantify the methanol-dependence of the ΔCP, as shown in Figure 9. In the presence of 500 mM NaCl and in the temperature range considered, the ΔCP was perturbed by approximately −50 cal mol−1 K−1 per %MeOH. In the absence of methanol, the ΔCP was −1.0 ± 0.1 kcal mol−1 K−1, quite close to the ΔCP of −0.9 ± 0.1 kcal mol−1 K−1 we recently reported for folding of the hammerhead ribozyme in either 1 M NaCl or 10 mM MgCl2 (36). Notably, at 35% methanol the ΔCP was observed to be −2.9 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 K−1, in reasonable agreement with the average value calculated from the perturbation approach.

Figure 8.

Plot of ITC-detected enthalpies of HH16 folding as a function of temperature and in the presence of 500 mM NaCl and 0% (circles), 15% (squares), 25% (diamonds) or 35% (triangles) methanol. Solid lines represent linear least-squares fits to the data at each methanol concentration. The slope of each line corresponds to the experimental ΔCP under that condition.

Figure 9.

Plot of ΔCPs for HH16 folding in the presence of 500 mM NaCl, as a function of methanol. The solid line is a linear least-squares fit to the data, with a slope of −52 cal mol−1 K−1 per %MeOH.

DISCUSSION

Measuring heat capacity changes for biomolecular transitions

The importance of ΔCP in the overall thermodynamics of protein folding is well accepted and empirical trends for ΔCP have been identified using a large basis set of proteins (47,48). Despite some early reports (8,9,49), the recognition of an important ΔCP contribution to nucleic acid folding is only now emerging (11,13,18,20,28). In theory, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is an excellent way to obtain ΔCP. In practice, ΔCP values obtained from DSC data depend strongly on the assignment of transition baselines. Proper assignment of these baselines can prove difficult, especially with RNA samples that begin to degrade at the high temperatures required for complete melting. DSC also provides certain challenges when applied to low-temperature transitions. Most importantly, specially modified equipment is required to analyze events at subzero temperatures. The van't Hoff approach also has a drawback—it imposes on the analysis a two-state assumption that may or may not be applicable to thermal melting of complex biological molecules. We have applied a perturbation approach to obtain ΔCPs for nucleic acid folding transitions. This approach is dependent on the observation of high- and low-temperature folding events, and on thermodynamic parameters from a well-defined reference state.

ΔCP derived from perturbation approach accurately estimates TC

The theory underlying our approach predicted that the perturbation effects on TC and TH would be opposite and of roughly equal magnitude, leading to the sum TC + TH being constant over the range of conditions that perturb the solution TMs. We thus began a systematic analysis of the high- and low-temperature folding transition temperatures of the hammerhead ribozyme using CD spectroscopy.

We chose to use the concentration of methanol co-solvent used as our cryo-protectant and the concentration of NaCl used to support ribozyme folding as the perturbants in our study. Since the phenomena we are testing derived from condensation theory, both of these parameters have predictable effects on the solution properties. Additional methanol lowers the solution dielectric and hence increases the strength of the electrostatic interactions, but may also have effects on hydrophobic interactions. Salt (50,51) and co-solvent (40,41,52) are well known to affect duplex stabilities, so it was evident that they would provide corresponding perturbations on stability of the ribozyme. For the hammerhead ribozyme, high NaCl concentration allows proper folding of the RNA core and the formation of an active ribozyme (22,23,45). Thus, above a certain level that would support folding, additional NaCl could be used relatively indiscriminately as a perturbant. The solvent dependence of hammerhead ribozyme activity was previously assessed and the presence of up to 40% MeOH was found to be quite benign (19). The effect of added methanol (up to ∼60%) on TH for DNA duplexes has been previously studied by two groups showing a linear dependence of both TM (40) and solution dielectric constant (41).

Thermal denaturation of the hammerhead ribozyme both at high and low temperatures was studied by CD spectroscopy. The concentrations of NaCl and methanol were varied systematically across an array of conditions. As expected, solution composition perturbed TH and TC values. To a first approximation, the sum of the high- and low-temperature TMs was found to be relatively constant (591 ± 12 K), suggesting that the system is suitable for this data treatment as predicted by the previous work of Rouzina and Bloomfield for DNA duplexes (11). Reference parameters for folding under conditions at the center of the matrix were refined through global fitting to the matrix of TH and TC data, yielding average values for ΔHfit, ΔSfit and ΔCPfit. At −3.4 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 K−1, ΔCPfit is much greater than the −0.8 kcal mol−1 K−1 approximated previously from the TH, TC and corresponding van't Hoff ΔHs for the hot and cold transitions (20). However, when this larger ΔCPfit is incorporated into the modified Gibbs equation for folding (Equation 2)—along with ΔHfit and ΔSfit—cold denaturation is predicted to occur at a TC within one degree of the observed TC under the reference conditions. We thus feel that the value reported here better represents the true ΔCP for hammerhead ribozyme folding in the cryosolvent conditions we have used. The previous van't Hoff estimate likely suffered from the imposition of a two-state folding model onto data that reflect multi-state folding behavior.

Calorimetry confirms calculated ΔCP and methanol-dependence of ΔCP

Systematic deviations in TC + TH suggested that the methanol co-solvent might perturb the ΔCP of folding in addition to making the intended perturbations in ΔH and ΔS. We used ITC to directly test this hypothesis, and to check the validity of the ΔCP generated by the perturbation approach.

The ITC data showed a significant, linear change in ΔCP with added methanol (Figure 8). Therefore, ΔCPfit represents an average value that was most accurate for the conditions at the center of the matrix, the same conditions in which the reference parameters were collected. In fact, the ITC-measured ΔCP in the presence of 35% methanol was −2.9 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1 K−1, in reasonable agreement with ΔCPfit for the perturbation matrix, centered at 35% methanol. Thus, the perturbation approach has successfully measured the ΔCP for folding for the conditions at the center of the matrix.

Methanol and salt effects on TH

Methanol–water mixtures are common solvents for working with biological molecules at subzero temperatures (1,53,54). Over the concentrations of methanol used in these studies, added methanol decreases the bulk dielectric of the solution in a roughly linear fashion (41). As a result, it magnifies the role of electrostatic interactions and reduces the energetic contribution of base stacking. For the hammerhead ribozyme, the TH decreased linearly as a function of the methanol concentration between 25 and 45%. This result agrees quantitatively with studies that probed co-solvent effects on the stability of DNA duplexes (55,56). Lowered dielectric may also alter RNA backbone dynamics such that unstacking is less energetically costly (57). Although we have not explored them in any systematic manner, specific methanol–water and methanol–RNA interactions could also contribute to the observed destabilizing effects.

The salt dependence of the TH also agrees with that generally seen in nucleic acid structure–function analyses. Across all methanol concentrations, the TH rises as NaCl concentration increases from 250 to 500 mM. This effect arises in part from a favorable entropic contribution to duplex stability deriving from diffuse Na+ binding (58), and possibly from similar entropic forces that promote packing of helical elements (59).

Methanol and salt effects on TC

The cold denaturation of nucleic acids had not been studied prior to our initial observation (20), so this work constitutes the first glimpse of the relationship of TC to the solution conditions. We can compare the low-temperature behavior to that observed at high temperature, however. Addition of methanol destabilizes the ribozyme with respect to cold unfolding as it does with high-temperature unfolding. Previous studies have attributed alcohol-promoted unstacking at high temperatures to a reduction in the hydrophobic effect (40), and this phenomenon likely operates at low temperatures as well. This notion is consonant with evidence that the organic denaturants (like methanol), while altering RNA stability, do not significantly change the mechanism of duplex formation (60).

The salt dependence of TC may reveal part of the mechanism of cold denaturation. Increasing concentrations of NaCl clearly promote cold denaturation, the opposite of the salt effect on TH. The inversion of the salt effect suggests that the energetic consequences of salt on the system are different at high and low temperature. This phenomenon may result from the entropic origin of electrostatic stabilization. At the low-temperature limits, the TΔS contribution of diffuse ion mobility becomes less effective at counterbalancing the unfavorable enthalpic impact of electrostatic repulsion between backbone phosphates. Conversely, the reduced thermal motion of the backbone might lead to foci of electrostatic potential prone to site-specific outer-sphere interaction with condensed ions. This alteration in the mode of binding might shift the balance of forces to favor unfolding. Although we do not yet have enough data to definitively identify and deconvolute the energetic components of the cold denaturation process, the observed ion dependence of TC indicates that diffuse ion-binding interactions might be central players in the process.

We have learned that the perturbation approach can effectively measure the ΔCP of macromolecular folding. At the same time, the methanol co-solvent that we used as a perturbant strongly affects ΔCP, the value we wish to measure. The molecular origin of this methanol-dependence in the observed ΔCP remains to be determined, particularly regarding the possible impact of methanol on the distribution of unfolded states. As in studies employing urea to measure the ΔG of folding, special care must be taken to extrapolate observed effects back to more physiological conditions in the absence of co-solvent. Thus, future applications of the perturbation approach must either account for such behavior or, preferably, employ perturbants that minimize the changes of ΔCP.

Cold denaturation and ΔCPs in biological function

What do the thermodynamics of cold denaturation tell us about the behavior of RNAs in vivo? Various RNAs clearly differ in their response to the kinds of solution conditions used in this study. For example, neither tRNAAla nor self-complementary 6mer RNAs show signs of cold denaturing in the presence of methanol and various combinations of NaCl, MgCl2 and urea. On the other hand, C-domain from Bacillus stearothermophilus RNase P and Escherichia coli DsrA RNA undergo low-temperature structural changes (J. C. Takach, G. Chen, P. J. Mikulecky and A. L. Feig, unpublished data).

The principal factor dictating whether one can observe the cold denaturation transition is the magnitude of the heat capacity change for a folding transition. Much remains to be done in understanding the physical basis of ΔCP for RNAs, but clearly, the presence of the traditionally neglected ΔCP can have large-scale consequences on RNA structure. Although the ΔCP affects stability at low temperatures more so than high ones, it has quantifiable effects at all temperatures other than the reference state. Even a small effect on stability, far short of full-fledged denaturation, could have significant biological consequences. For example, a pool of complementary sequences or high-affinity protein ligands may sequester a small, Boltzmann-weighted population of unfolded RNAs, thereby pulling the remaining RNAs toward the denatured state. Such a mechanism could conceivably be exploited in transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression, perhaps differentially responding to temperature. As we grapple with the interplay of RNA structures and their myriad of cellular functions, we must expand our understanding of the thermodynamic intricacies of these species and the way they respond to solution conditions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at NAR Online.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Evelyn Jabri, Ioulia Rouzina, Jen Takach and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the work and the manuscript. This work was supported by IU, the IU Department of Chemistry and grants from the NIH (GM-065430 to A.L.F. and T32-GM07757 to P.J.M.). A.L.F. is a Cottrell Scholar of Research Corporation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Privalov P.L. (1990) Cold denaturation of proteins. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 25, 281–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robertson A.D. and Murphy,K.P. (1997) Protein structure and the energetics of protein stability. Chem. Rev., 97, 1251–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serra M.J. and Turner,D.H. (1995) Predicting thermodynamic properties of RNA. Methods Enzymol., 259, 242–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SantaLucia J. Jr and Turner,D.H. (1998) Measuring the thermodynamics of RNA secondary structure formation. Biopolymers, 44, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloomfield V.A., Crothers,D.M. and Tinoco,I.,Jr (2000) Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties and Functions. University Science Books, Sausalito, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslauer K.J., Frank,R., Blocker,H. and Marky,L.A. (1986) Predicting DNA duplex stability from the base sequence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 3746–3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae W., Xia,B., Inouye,M. and Severinov,K. (2000) Escherichia coli CspA-family RNA chaperones are transcription antiterminators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 7784–7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersheim M. and Turner,D.H. (1983) Base-stacking and base-pairing contributions to helix stability: thermodynamics of double-helix formation with CCGG, CCGGp, CCGGAp, ACCGGp, CCGGUp, and ACCGGUp. Biochemistry, 22, 256–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinz H.J., Filimonov,V.V. and Privalov,P.L. (1977) Calorimetric studies on melting of tRNA Phe (yeast). Eur. J. Biochem., 72, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouzina I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1999) Heat capacity effects on the melting of DNA. 2. Analysis of nearest- neighbor base pair effects. Biophys. J., 77, 3252–3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouzina I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (1999) Heat capacity effects on the melting of DNA. 1. General aspects. Biophys. J., 77, 3242–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubins D.N., Lee,A., Macgregor,R.B.,Jr and Chalikian,T.V. (2001) On the stability of double stranded nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 123, 9254–9259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holbrook J.A., Capp,M.W., Saecker,R.M. and Record,M.T.,Jr (1999) Enthalpy and heat capacity changes for formation of an oligomeric DNA duplex: interpretation in terms of coupled processes of formation and association of single-stranded helices. Biochemistry, 38, 8409–8422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalikian T.V., Volker,J., Plum,G.E. and Breslauer,K.J. (1999) A more unified picture for the thermodynamics of nucleic acid duplex melting: a characterization by calorimetric and volumetric techniques. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 7853–7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang X.W., Golden,B.L., Littrell,K., Shelton,V., Thiyagarajan,P., Pan,T. and Sosnick,T.R. (2001) The thermodynamic origin of the stability of a thermophilic ribozyme. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 4355–4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammann C., Cooper,A. and Lilley,D.M. (2001) Thermodynamics of ion-induced RNA folding in the hammerhead ribozyme: an isothermal titration calorimetric study. Biochemistry, 40, 1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathews D.H. and Turner,D.H. (2002) Experimentally derived nearest-neighbor parameters for the stability of RNA three- and four-way multibranch loops. Biochemistry, 41, 869–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu P., Nakano,S. and Sugimoto,N. (2002) Temperature dependence of thermodynamic properties for DNA/DNA and RNA/DNA duplex formation. Eur. J. Biochem., 269, 2821–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feig A.L., Ammons,G. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1998) Cryoenzymology of the hammerhead ribozyme. RNA, 4, 1251–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikulecky P.J. and Feig,A.L. (2002) Cold denaturation of the hammerhead ribozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 890–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wedekind J.E. and McKay,D.B. (1998) Crystallographic structures of the hammerhead ribozyme: relationship to ribozyme folding and catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct., 27, 475–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Rear J.L., Wang,S., Feig,A.L., Beigelman,L., Uhlenbeck,O.C. and Herschlag,D. (2001) Comparison of the hammerhead cleavage reactions stimulated by monovalent and divalent cations. RNA, 7, 537–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray J.B., Seyhan,A.A., Walter,N.G., Burke,J.M. and Scott,W.G. (1998) The hammerhead, hairpin and VS ribozymes are catalytically proficient in monovalent cations alone. Chem. Biol., 5, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis E.A. and Bartel,D.P. (2001) The hammerhead cleavage reaction in monovalent cations. RNA, 7, 546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klostermeier D. and Millar,D.P. (2000) Helical junctions as determinants for RNA folding: origin of tertiary structure stability of the hairpin ribozyme. Biochemistry, 39, 12970–12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouzina I.I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (2001) Force-induced melting of the DNA double helix. 2. Effect of solution conditions. Biophys. J., 80, 894–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams M.C., Wenner,J.R., Rouzina,I. and Bloomfield,V.A. (2001) Entropy and heat capacity of DNA melting from temperature dependence of single molecule stretching. Biophys. J., 80, 1932–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diamond J.M., Turner,D.H. and Matthews,D.H. (2001) Thermodynamics of three-way multibranch loops in RNA. Biochemistry, 40, 6971–6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu M., SantaLucia,J.,Jr and Turner,D.H. (1997) Solution structure of (rGGCAGGCC)2 by two dimensional NMR and the iterative relaxation matrix approach. Biochemistry, 36, 4449–4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper A. (1999) Thermodynamic analysis of biomolecular interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., 3, 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horn J.R., Russell,D., Lewis,E.A. and Murphy,K.P. (2001) van't Hoff and calorimetric enthalpies from isothermal titration calorimetry: are there significant discrepancies. Biochemistry, 40, 1774–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mizoue L.S. and Tellinghuisen,J. (2004) Calorimetric vs. van't Hoff binding enthalpies from isothermal titration calorimetry: Ba2+–crown ether complexation. Biophys. Chem., 110, 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milligan J.F., Groebe,D.R., Witherell,G.W. and Uhlenbeck,O.C. (1987) Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 8783–8798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schroeder S.J. and Turner,D.H. (2000) Factors affecting the thermodynamic stability of small asymmetric internal loops in RNA. Biochemistry, 39, 9257–9274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creighton T.E. (1993) Proteins: Structure and Molecular Properties, 2nd edn. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mikulecky P.J., Takach,J.C. and Feig,A.L. (2004) Entropy-driven folding of an RNA helical junction: an isothermal titration calorimetric analysis of the hammerhead ribozyme. Biochemistry, 43, 5870–5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiseman T., Williston,S., Brandts,J.F. and Lin,L.N. (1989) Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem., 179, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woody R.W. (1995) Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol., 246, 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray D.M., Hung,S.-H. and Johnson,K.H. (1995) Absorption and circular dichroism spectroscopy of nucleic acid duplexes and triplexes. Methods Enzymol., 246, 19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breslauer K.J., Bodnar,C.M. and McCarthy,J.E. (1978) The role of solvents in the stabilization of helical structure: the low pH ribo A8 and A10 double helices in mixed solvents. Biophys. Chem., 9, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Votavova H., Kucerova,D., Felsberg,J. and Sponar,J. (1986) Changes in conformation, stability and condensation of DNA by univalent and divalent cations in methanol–water mixtures. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 4, 477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holbrook J.A., Capp,M.W., Saecker,R.M. and Record,M.T.,Jr (1999) Enthalpy and heat capacity changes for formation of an oligomeric DNA duplex: interpretation in terms of coupled processes of formation and association of single-stranded helices. Biochemistry, 38, 8409–8422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takach J.C., Mikulecky,P.J. and Feig,A.L. (2004) Salt-dependent heat capacity changes for RNA duplex formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 126, 6530–6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dimitrov R.A. and Zuker,M. (2004) Prediction of hybridization and melting for double-stranded nucleic acids. Biophys. J., 87, 215–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hampel K.J. and Burke,J.M. (2003) Solvent protection of the hammerhead ribozyme in the ground state: evidence for a cation-assisted conformational change leading to catalysis. Biochemistry, 42, 4421–4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner D. (2000) Conformational changes. In Bloomfield,V.A., Crothers,D.M. and Tinoco,I.,Jr (eds), Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties, and Functions. University Science Books, Sausalito, CA, pp. 259–334. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makhatadze G.I. (1998) Heat capacities of amino acids, peptides and proteins. Biophys. Chem., 71, 133–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez J., Hilser,V.J., Xie,D. and Freire,E. (1995) The heat capacity of proteins. Proteins, 22, 404–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suurkuusk J., Alvarez,J., Freire,E. and Biltonen,R. (1977) Calorimetric determination of the heat capacity changes associated with the conformational transitions of polyriboadenylic acid and polyribouridylic acid. Biopolymers, 16, 2641–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volker J., Klump,H.H., Manning,G.S. and Breslauer,K.J. (2001) Counterion association with native and denatured nucleic acids: an experimental approach. J. Mol. Biol., 310, 1011–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bond J.P., Anderson,C.F. and Record,M.T.,Jr (1994) Conformational transitions of duplex and triplex nucleic acid helices: thermodynamic analysis of effects of salt concentration on stability using preferential interaction coefficients. Biophys. J., 67, 825–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hickey D.R. and Turner,D.H. (1985) Solvent effects on the stability of A7U7p. Biochemistry, 24, 2086–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Douzou P., Hui Bon Hoa,G., Maurel,P. and Travers,F. (1976) Physical chemical data for mixed solvents used in low temperature biochemistry. In Fasman,G.D. (ed.), Handbook of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 3rd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douzou P. (1983) Cryoenzymology. Cryobiology, 20, 625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albergo D.D. and Turner,D.H. (1981) Solvent effects on thermodynamics of double-helix formation in (dG-dC)3. Biochemistry, 20, 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiman R. and Draper,D.E. (2000) Stabilization of RNA tertiary structure by monovalent ions. J. Mol. Biol., 302, 79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norberg J. and Nilsson,L. (1998) Solvent influence on base stacking. Biophys. J., 74, 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manning G.S. (2003) Comments on selected aspects of nucleic acid electrostatics. Biopolymers, 69, 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murthy V.L. and Rose,G.D. (2000) Is counterion delocalization responsible for collapse in RNA folding? Biochemistry, 39, 14365–14370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Strazewski P. (2002) Thermodynamic correlation analysis: hydration and perturbation sensitivity of RNA secondary structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 124, 3546–3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.