Abstract

Antiplatelet agents are pivotal for prevention of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease worldwide. Individual patient data meta‐analysis indicates that low‐dose aspirin causes a 10% risk reduction in pre‐eclampsia for women at high individual risk. However, in the last 15 years it has emerged that a significant proportion of aspirin‐treated individuals exhibit suboptimal platelet response, determined biochemically and clinically, termed ‘aspirin non‐responsiveness’, ‘aspirin resistance’ and ‘aspirin treatment failure’. More recently, investigation of aspirin responsiveness has begun in pregnant women. This review explores the history and clinical relevance of ‘aspirin resistance’ applied to high‐risk obstetric populations.

Tweetable abstract

Is ‘aspirin resistance’ clinically relevant in high‐risk obstetrics?

Keywords: Activation, aspirin, platelet, pre‐eclampsia, pregnancy, resistance

Tweetable abstract

Is ‘aspirin resistance’ clinically relevant in high‐risk obstetrics?

Introduction

Antiplatelet agents are pivotal in both primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease worldwide (Table 1). In high‐risk pregnant women, low‐dose aspirin (LDA) also confers a 10% risk reduction for pre‐eclampsia and a 20% risk reduction for fetal growth restriction.8, 9 However, it has been postulated that a significant proportion of individuals exhibit suboptimal response to aspirin, defined biochemically as diminished suppression of platelet activation or clinically as development of thrombotic events while on treatment.10 This has been referred to interchangeably, as ‘aspirin non‐responsiveness’, ‘aspirin resistance’ and ‘aspirin treatment failure’. Controversies remain regarding the definition, optimal means of identification, and management strategy in affected individuals.11 Determination of compliance with aspirin is likely to be of central importance to discriminate non‐compliance from true suboptimal response and begin to explore causal mechanisms including pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and genetic factors. Recently, the concept of ‘aspirin resistance’ has been extended to high‐risk obstetric populations where sustained platelet activation despite LDA has been linked to subsequent pre‐eclampsia and/or fetal growth restriction. This review explores the history and clinical relevance of ‘aspirin resistance’ and methods to assess platelet response to aspirin with particular focus on pregnancy.

Table 1.

Clinical indications for aspirin therapy in medical and surgical specialities

| Clinical area | Clinical situation | Dose | Guideline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | Acute myocardial infarction | 300 mg | NICE1 |

| Acute unstable angina | 300 mg | ||

| Secondary prevention of myocardial infarction | 75 mg | NICE2 | |

| Atrial fibrillation, primary prevention of myocardial infarction | 75 mg | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | Acute ischaemic stroke | 300 mg | NICE3 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 300 mg | NICE4 | |

| Secondary prevention of stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 75 mg | ||

| Peripheral arterial disease | Secondary prevention | 75 mg | NICE4 |

| High‐risk Pregnancy | Antiphospholipid syndrome | 75 mg from conception, combined with low‐molecular‐weight heparin | RCOG5 |

| High risk for pre‐eclampsia | 75 mg from 12 weeks | NICE6 | |

| High risk for small‐for‐gestational‐age infant | Consider 75 mg <16 weeks if at high risk for pre‐eclampsia | RCOG7 |

History of aspirin

Aspirin is one of the oldest medications still in widespread modern use. The first records of aspirin‐related compounds, ‘salix’, derived from willow tree bark, were documented on papyrus scrolls used by Egyptian physicians in 1534 BC.12 The translation of this knowledge into modern practice began in Oxford in 1758 when Reverend Edward Stone consumed, and later successfully trialled willow tree bark for relief of headaches, myalgia and fever.13 In 1971 Vale, Samuelson and Bergstrom were awarded the Nobel Prize for elucidating the mechanism of action of aspirin, and clinical research investigating the antiplatelet effects of aspirin began.14, 15 Although aspirin was initially used as an analgesic and antipyretic, its antiplatelet effects mean it has become one of the most frequently prescribed medications worldwide, taken by more than 50 million people for prevention of cardiovascular disease alone, with approximately 40 000 tons administered annually. Aspirin's broad clinical effectiveness, cost‐effectiveness and safety profile have led to its inclusion in the WHO Essential Medicines list for basic healthcare systems.16

Aspirin's most frequently reported adverse effect is gastric irritation. Enteric formulations do not appear to reduce this effect but they have been associated with diminished platelet effects and may reduce bioavailability.17 A systematic review published in 2014 supports the safety of aspirin in pregnancy, particularly for women at high‐risk of pre‐eclampsia, finding no increase in maternal or neonatal bleeding complications.9

Mechanism of action of aspirin

Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) is a weak acid, with a white crystalline appearance in its solid state. Acetylsalicylic acid is produced by esterification of salicylic acid, catalysed by sulphuric acid, with acetic acid also generated as a by‐product. Aspirin is administered orally and is readily absorbed in the upper gastrointestinal tract with most platelet effects occurring in the portal system.10

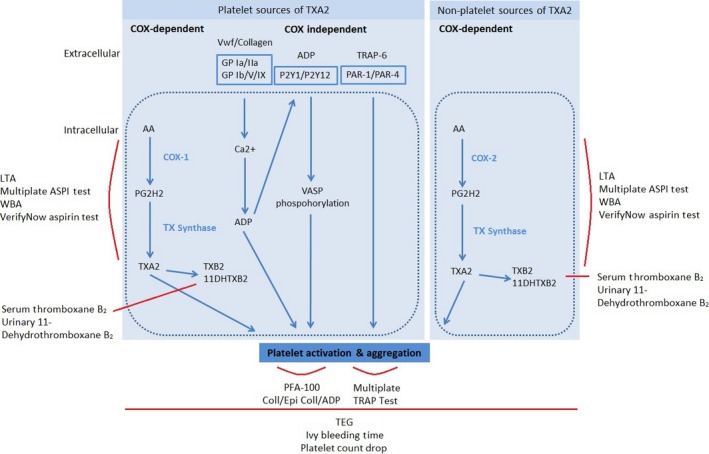

The principal pharmacological target of acetylsalicylic acid is the platelet enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), responsible for producing prostaglandins which mediate pain and induce platelet activation. COX is a membrane‐bound glycoprotein with three isoforms (COX‐1, COX‐2, COX‐3). Acetylsalicylic acid selectively acetylates the serine residue (Ser529), altering the enzyme structure and preventing binding of arachidonic acid to the Tyr385 catalytic site. The resultant inhibition of prostaglandin H‐synthase production leads to irreversible inhibition of COX‐1 activity and, to a lesser degree, inhibition of COX‐2 activity (Figure 1).18, 19 COX‐1 inhibition by aspirin is rapid and saturable at low doses. Peak plasma concentrations are reached within 40 minutes, and demonstrable platelet inhibition occurs within 1 hour of ingestion for non‐enteric coated formulations.18 In non‐pregnant individuals, low‐dose aspirin (0.45 mg/kg, 60–150 mg) administered once daily has been demonstrated to reduce serum thromboxane B2 (TxB2, the stable serum metabolite of thromboxane A2) by a minimum of 95% within 5 days of commencing treatment.18, 19, 20 It is important to note that thromboxane A2 is also produced in smaller quantities via COX‐independent pathways, and from non‐platelet sources such as monocytes and macrophages (Figure 1). These pathways have considerable inter‐connections.19 Following acetylsalicylic acid exposure, COX‐dependent generation of thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and TxA2‐induced platelet aggregation remain inhibited for the lifespan of the platelet. In the healthy non‐pregnant state the average platelet lifespan is 8–9 days.

Figure 1.

Platelet activation pathways and relevant assays.

Platelet response to aspirin

The concept of suboptimal platelet response to aspirin, linked to recurrent cardiovascular and cerebrovascular ischaemia and cardiovascular deaths,21 has become well‐established in cardiovascular and stroke research over the last 20 years. Suboptimal platelet response is usually defined as a biochemical failure to inhibit platelet activation in aspirin‐treated individuals, assessed in the laboratory or with point‐of‐care tests. Suboptimal response to aspirin has also been described clinically as recurrence of ischaemic events despite aspirin treatment at the recommended dose. However, there is currently no universally accepted definition which unifies laboratory and clinical findings. The reported prevalence ranges from 5 to 65%, varying with the assay used and the populations studied.22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Proposed underlying causes include drug interactions and states of enhanced platelet turnover, such as during the immediate postoperative period and in pregnancy. Genetic predisposition is also likely to be influential; however, non‐compliance is widespread in cardiology populations represented in the literature and is likely to be a key determinant.27, 28

Tests of platelet response to aspirin

A range of platelet activation and function assays are available, but suffer from limited reproducibility and poor agreement between assays. With appropriate dosing and compliance, low‐dose aspirin provides complete inhibition of the COX‐1 pathway, the primary target of aspirin, in over 99% of individuals. Consequently, platelet function assays that target the aspirin COX pathways demonstrate lower inter‐individual variability.

COX‐specific assays include light transmission aggregrometry (LTA) with arachidonic acid‐induced platelet activation (Figure 1). The method is based on detection of light that passes through platelet‐rich plasma containing aggregated platelets. VerifyNow utilises the theory of LTA but allows assessment using whole blood within a closed point‐of‐care system. Additionally, the stable serum and urinary metabolites of TxA2, TxB2 and 11‐dehydrothromboxane B2 (11‐DTxB2), respectively, can be quantified (Figure 1).

In contrast, if platelet function assays rely on adenosine diphosphate (ADP), collagen or epinephrine for platelet activation, the assays are considered to assess non‐COX‐dependent pathways (Figure 1). Non‐COX‐specific assays include the PFA‐100 System, a point‐of‐care system using citrated whole blood. It measures the time taken for platelet aggregation to occlude a micro‐aperture within collagen/epinephrine or collagen/ADP‐coated cartridges. Thromboelastography (TEG) measures speed and strength of clot formation as an indirect assessment of the contribution of platelet aggregation to stable clot formation. Bleeding time measurements provide an in vivo assessment of time taken for blood to clot in a superficial linear forearm wound. Platelet counts approximate the impact of platelet activation, aggregation, sequestration and destruction on total circulating platelets. These assays demonstrate a high degree of inter‐individual variability; however, due to the multiple pathways involved in platelet activation, non‐COX‐specific assays may better reflect the global platelet response and provide information about in vivo milieu.

Literature review

We set out to identify all biochemical tests and definitions used to define suboptimal platelet response to aspirin across all clinical applications. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library from 1957 to 26 February 2015, limited to humans and English language. The search terms used were ‘aspirin’, ‘acetylsalicylic acid’ appearing adjacent to ‘resistance’, ‘non‐responsiveness’, ‘treatment failure’ and ‘pseudoresistance’. All original articles were included; review articles were excluded. Additionally, we excluded articles relating to studies where participants received concomitant alternative antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants. This search yielded 492 articles after abstract and full text reviews (135) were included.

Tests and definitions

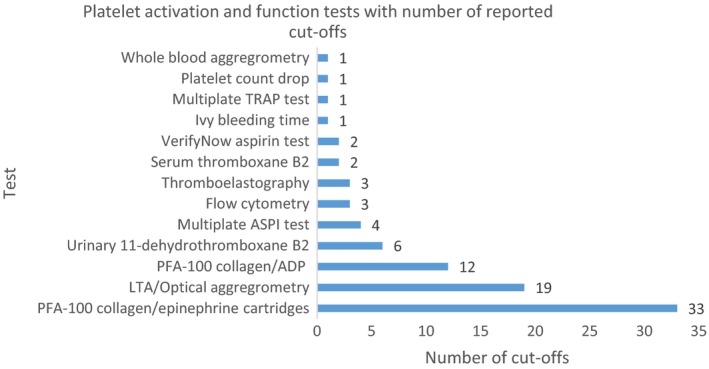

There is now a broad range of experience with platelet activation and function testing across speciality areas: healthy individuals, cardiology, stroke, endocrinology, nephrology, rheumatology, general medicine, general surgery, vascular surgery, paediatrics and high‐risk obstetrics (Supporting Information Table S1). Our review identified 13 platelet activation assays; the three most commonly used were PFA 100 collagen/epinephrine cartridges, LTA with arachidonic acid induction and PFA‐100 collagen/ADP cartridges (Figure 2, expanded information in Table S1). In the examined literature, PFA‐100 collagen/epinephrine cartridges were associated with 33 different cut‐offs, the commonest being <165 seconds (Table S1). LTA had 19 proposed cut‐offs, the commonest being a mean aggregation of ≥20%. PFA collagen/epinephrine cartridges had 12 different cut‐offs, the commonest being <114 seconds (Table S1). The majority of studies refer to manufacturer's cut‐offs, or have conducted in‐house work to establish cut‐offs from small numbers of predominantly male volunteers. Subsequently, there is limited applicability of these cut‐offs to obstetric populations.

Figure 2.

Platelet activation and function tests with number of reported cut‐offs.

In total, 88 different definitions of suboptimal platelet response to aspirin have been described, the vast majority utilising only laboratory‐based parameters to delineate responsiveness to aspirin. One study defined suboptimal response clinically as the occurrence of myocardial infarction in patients with stable coronary artery disease while on aspirin therapy.29 Another described a combined definition with laboratory assessment of 11‐DTxB2 and ischaemic cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events.26 We identified 24 studies where suboptimal response to aspirin was linked to clinical outcomes: 14 in cardiology, 6 in stroke patients, 1 in nephrology and 3 in obstetrics (Supporting Information Table S2).

Obstetric studies were carried out in pregnant women at high risk of pre‐eclampsia, including two prospective cohort studies, one case‐control study and a dose escalation study from groups in the UK, Canada and Poland (Table S2).30, 31, 32, 33 Two studies used PFA‐100 collagen/epinephrine cartridges, with diagnostic cut‐offs determined from the mixed adult population.31, 32 One study utilised 11‐DTxB2 with locally determined pregnancy‐specific cut‐offs, and one study used the LTA method. In these high‐risk obstetric populations, suboptimal platelet response to aspirin was identified in 29–39% of participants, and was associated with increased pre‐eclampsia, preterm birth and delivery of small‐for‐gestational‐age infants.31, 32 Additionally, Rey et al.31 assessed the impact of PFA‐100 guided aspirin dose escalation and determined that women requiring escalation had a higher risk of pre‐eclampsia (11/43, 25.6% versus 6/68, 8.8%; P = 0.03).

Non‐compliance testing

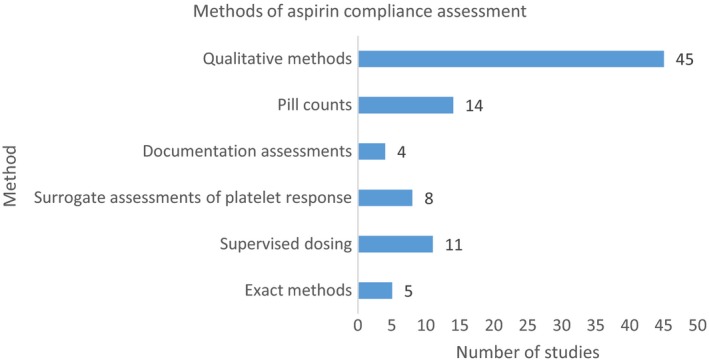

To assess the clinical impact of suboptimal platelet response to aspirin, it is vital that true non‐responsiveness can be distinguished from non‐compliance. In cardiovascular research, patient non‐compliance with medication is reported to be widespread at 30–50%.10 The existing literature demonstrates that there is no consensus on robust assessment of compliance (Figure 3, expanded information in Supporting Information Table S3). Where researchers have endeavoured to quantify the impact of non‐compliance, most have relied on qualitiatiive measures including patient enquiries, questionnaires and drug diaries, which are likely to underestimate the true scale. In our review, 5/87 (6%) relied on assessment of serum or urinary thromboxane, both considered to be measures of platelet activation (Table S3). However, elevated TxB2 and 11‐DTxB2 may be secondary to non‐platelet sources and therefore not a specific reflection of platelet COX inhibition by aspirin. Importantly, only 2/87 (2%) of studies measured salicylate levels, both in patients taking aspirin for cardiovascular disease prevention (Table S3). Three of four obstetric studies considered the issue of compliance and undertook verbal enquiries at study visits.31, 32, 33 Biochemical assessment of aspirin metabolites has not been assessed in pregnant populations.

Figure 3.

Methods of aspirin compliance assessment.

Causal mechanisms for suboptimal response to aspirin with adequate compliance

Where compliance is confirmed, the remainder of individuals with persistent suboptimal suppression of platelet activation are likely to represent a heterogeneous group with interacting physiological, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors.

In healthy adults, 10% of circulating platelet numbers are replaced with aspirin‐naïve platelets daily. It has been accepted that acetylsalicylic acid irreversibly inhibits COX‐1 in exposed platelets and with regular dosing, adequate global inhibition of platelet COX activity is maintained. Interestingly, recent work has demonstrated mRNA sequence coding for COX‐1 within platelets, raising a possibility that generation of new COX‐1, following inhibition of the native enzyme, may circumvent the antiplatelet action of aspirin.

Patients may be insufficiently treated with aspirin for a variety of reasons, including problems with total dose, inappropriate dosing intervals or dose delivery issues. Enteric coated aspirin in particular has been implicated in suboptimal suppression of platelet activation, as demonstrated by laboratory tests.17 It is now clear that low‐dose aspirin is as effective as high‐dose aspirin for secondary prevention of ischaemic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.34 However, there remain limitations in dose selection due to the range of low doses currently manufactured (60–150 mg). The standard low (75 mg) daily dose recommended by NICE is more than double the dose required to maintain complete COX‐1 inhibition in non‐pregnant individuals, although there has been no assessment of platelet effects of this dose in pregnancy.35

Once‐daily dosing has become standard practice, as the effects of aspirin are dependent on the rate of platelet turnover as opposed to the half‐life,36 but incomplete maintenance of COX‐1 suppression with once‐daily doses has been described in association with increased platelet turnover in diabetes, obesity and postoperative states.37, 38

Daily low doses of aspirin irreversibly inhibit COX‐1 activity in platelets and impact COX‐1 in megakaryocyte precursors, an effect which diminishes with accelerated platelet maturation.36 This is of particular relevance for obstetric populations where platelets are continually sequestered by the placenta, balanced by an increase in platelet production and release from bone marrow, resulting in an increase in circulating immature platelets, which are pre‐disposed to aggregate at lower levels of stimuli. Additionally, endothelial dysfunction in pregnancies affected by pre‐eclampsia leads to pathologically increased platelet activation and destruction, which may outstrip the ability of the bone marrow to compensate, leading to thrombocytopaenia.

Circadian timing of aspirin doses may also be of significance. Recently, evening dosing has been associated with beneficial effects on ambulatory blood pressure and decreased hazard ratios of a composite of serious adverse events in high‐risk pregnant populations.39, 40

Pharmacogenetics

Inter‐individual variability in response to aspirin is affected by clinical, environmental and genetic factors, the latter of which have been targeted for investigation in recent years. Initial attempts to identify genetic determinants of suboptimal platelet response to aspirin in non‐obstetric populations were afflicted by poor reproducibility in underpowered candidate gene studies. However, recent large studies have combined candidate gene and genome‐wide association study (GWAS) approaches and have described important genetic determinants that map with platelet function.41 These include loci associated with native platelet function in the following genes; PEAR1, SHH, MRVII, ADRA2A and GP6. Additionally, gene expression analysis has been used to identify >60 genes described as the ‘aspirin response signature’.42 The experience and recent developments in the pharmacogenetics of aspirin provide a promising start for GWAS in high‐risk obstetrics.

Implications for research in obstetrics

It is vital that true suboptimal response to aspirin is distinguished from aspirin non‐compliance. We firmly believe that compliance testing should be based on detection and quantification of aspirin metabolites from maternal blood or urine.

A suboptimal response to aspirin in compliant patients does not currently have a uniform definition, nor has an adequately sensitive, specific diagnostic test emerged and this should be prioritised. Tests aligned to the COX pathway are likely to be of greatest clinical utility, particularly if point‐of‐care use is feasible.

Platelet activation should be measured against pregnancy‐specific reference ranges, and if suboptimal response is identified, its clinical significance must be judged in light of clinically important outcomes.

Accurate and user‐friendly stratification of pregnant women according to response to aspirin and compliance should encourage interventional studies of new treatments with alternative targets within platelet activation pathways or the coagulation cascade.8 For genuine non‐responders to standard LDA, randomised comparisons with aspirin dose escalation and low‐molecular‐weight heparin should be carried out. The outcomes of interest should not be restricted to platelet response to aspirin, but also include placentally mediated adverse outcomes (pre‐eclampsia, IUGR, placental abruption and stillbirths). Heterogeneity in response to aspirin due to genetic factors has not yet been investigated in pregnancy and may provide a unique, early and discriminative means of risk stratification.

The pathophysiology of pre‐eclampsia remains incompletely elucidated and increased understanding of its evolution is likely to be key in guiding screening and interventional approaches. Further investigation of platelet response to LDA in high‐risk pregnant women may provide fresh insight into the relatively modest risk reduction in placentally mediated disease observed with current therapy. If women with suboptimal response to aspirin experience more adverse clinical events, this may prove not only an important research area for preventative therapy but a valuable opportunity to stratify maternal and fetal surveillance in the near future. With current debates regarding the potential utility and cost‐effectiveness of no test/treat all approaches to pre‐eclampsia prevention, the acceptability of such approaches to women and compliance with aspirin will be key issues.43, 44 Additionally, recent signals of increased risk of placental abruption will need to be rigorously assessed.9

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

ZA conceived the idea. KN performed the literature searches and reviewed the papers. KN prepared the manuscript with the advice of AA. AA and ZA reviewed the final manuscript.

Details of ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required for this review.

Funding

Research Training Fellowship for Dr Kate Navaratnam provided by Wellbeing of Women.

Supporting information

Table S1. Platelet activation and function tests.

Table S2. Clinical evaluation of aspirin resistance.

Table S3. Methods of aspirin compliance assessment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Wellbeing of Women.

Navaratnam K, Alfirevic A, Alfirevic Z. Low dose aspirin and pregnancy: how important is aspirin resistance? BJOG 2016;123:1481–1487.

Linked article This article is commented on by MK Hoffman. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13983.

References

- 1. NICE . Unstable Angina and Nstemi: The Early Management of Unstable Angina and Non‐st Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. London: NICE, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. NICE . Secondary Prevention. Secondary Prevention in Primary and Secondary Care for Patients Following a Myocardial Infarction. London: NICE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NICE . Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack in Over 16s: Diagnosis and Initial Management. London: NICE, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. NICE . Clopidogrel and Modified‐Release Dipyridamole for the Prevention of Occlusive Vascular Events. London: NICE, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. RCOG . Recurrent Miscarriage, Investigation and Treatment of Couples (Green‐Top Guideline no. 17). London: RCOG, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. NICE . Hypertension in Pregnancy. London: NICE, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. RCOG . Small‐for‐Gestational‐Age Fetus, Investigation and Management (Green‐Top Guideline no. 31). London: RCOG, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson‐Smart DJ, Stewart LA. Fast track‐articles: antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre‐eclampsia: a meta‐analysis of individual patient data. Lancet 2007;369:1791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu TT, Zhou F, Deng CY, Huang GQ, Li JK, Wang XD. Low‐dose aspirin for preventing preeclampsia and its complications: a meta‐analysis. J Clin Hypertens 2015;17:567–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. Aspirin resistance. Lancet 2006;367:606–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. FitzGerald R, Pirmohamed M. Aspirin resistance: effect of clinical, biochemical and genetic factors. Pharmacol Ther 2011;130:213–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ebers G. Ebers Papyrus http://web.archive.org/web/20130921055114/http://oilib.uchicago.edu/books/bryan_the_papyrus_ebers_1930.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2016.

- 13. Stone E. An account of the success of the bark of the willow in the cure of agues. Philos Trans 1763;53:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerhardt C. Untersuchungen über die Wasserfreien organischen Säuren. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem 1853;87:149. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zundorf U. Aspirin 100 Years: The Future Has Just Begun. Leverkusen: Bayer AG, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO [http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/EML2015_8-May-15.pdf]. Accessed 3 March 2015.

- 17. Grosser T, Fries S, Lawson JA, Kapoor SC, Grant GR, FitzGerald GA. Drug resistance and pseudoresistance: an unintended consequence of enteric coating aspirin. Circulation 2013;127:377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roth GJ, Majerus PW. The mechanism of the effect of aspirin on human platelets. I. Acetylation of a particulate fraction protein. J Clin Invest 1975;56:624–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roth GJ, Calverley DC. Aspirin, platelets, and thrombosis: theory and practice. Blood 1994;83:885–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Spencer FA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI. Antiplatelet drugs: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th edn. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141 (2 Suppl):e89S–119S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krasopoulos G, Brister SJ, Beattie WS, Buchanan MR. Aspirin ‘resistance’ and risk of cardiovascular morbidity: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2008;336:195–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michelson AD. Platelet function testing in cardiovascular diseases. Circulation 2004;110:e489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weber AA, Przytulski B, Schanz A, Hohlfeld T, Schror K. Towards a definition of aspirin resistance: a typological approach. Platelets 2002;13:37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snoep JD, Hovens MC, Eikenboom JJ, van der Bom JG, Huisman MV. Association of laboratory‐defined aspirin resistance with a higher risk of recurrent cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1593–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marshall PW, Williams AJ, Dixon RM, Growcott JW, Warburton S, Armstrong J, et al. A comparison of the effects of aspirin on bleeding time measured using the Simplate(TM) method and closure time measured using the PFA‐100(TM), in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1997;44:151–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Aspirin‐resistant thromboxane biosynthesis and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Circulation 2002;105:1650–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gum PA, Kottke‐Marchant K, Poggio ED, Gurm H, Welsh PA, Brooks L, et al. Profile and prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maree AO, Fitzgerald DJ. Variable platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel in atherothrombotic disease. Circulation 2007;115:2196–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neergaard‐Petersen S, Ajjan R, Hvas A‐M, Hess K, Larsen SB, Kristensen SD, et al. Fibrin clot structure and platelet aggregation in patients with aspirin treatment failure. PLoS One 2013;8:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wojtowicz A, Undas A, Huras H, Musial J, Rytlewski K, Reron A, et al. Aspirin resistance may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2011;32:334–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Caron N, Rivard G, Michon N, Morin F, Pilon D, Montquin J, et al. Low‐dose ASA response using the PFA‐100 in women with high risk pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009;31:1022–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rey E, Rivard G‐E. Is testing for aspirin response worthwhile in high‐risk pregnancy? Eur J Obstet Gynecol 2011;157:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sullivan MHF, Elder MG. Changes in platelet reactivity following aspirin treatment for pre‐eclampsia. BJOG 1993;100:542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration . Collaborative meta‐analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Patrignani P, Filabozzi P, Patrono C. Selective cumulative inhibition of platelet thromboxane production by low‐dose aspirin in healthy subjects. J Clin Invest 1982;69:1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patrono C, Patrono C. The multifaceted clinical readouts of platelet inhibition by low‐dose aspirin. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evangelista V, de Berardis G, Totani L, Avanzini F, Giorda CB, Brero L, et al. Persistent platelet activation in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with low doses of aspirin. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maree AO, Curtin RJ, Dooley M, Conroy RM, Crean P, Cox D, et al. Platelet response to low‐dose enteric‐coated aspirin in patients with stable cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Fernandez JR, Mojon A, Alonso I, Silva I, et al. Administration time‐dependent effects of aspirin in women at differing risk for preeclampsia. Hypertension 1999;34:1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ayala DE, Ucieda R, Hermida R. Chronotherapy with low‐dose aspirin for prevention of complications in pregnancy. Chronobiol Int 2013;30:260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beitelshees AL, Voora D, Lewis JP. Personalized antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy: applications and significance of pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics Pers Med 2015;8:43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Voora D, Cyr D, Lucas J, Chi J‐T, Dungan J, McCaffrey TA, et al. Aspirin exposure reveals novel genes associated with platelet function and cardiovascular events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hyde C, Thornton S. Does screening for pre‐eclampsia make sense? BJOG 2013;120:1168–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Werner EF, Hauspurg AK, Rouse DJ. A cost‐benefit analysis of low‐dose aspirin prophylaxis for the prevention of preeclampsia in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:1242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Platelet activation and function tests.

Table S2. Clinical evaluation of aspirin resistance.

Table S3. Methods of aspirin compliance assessment.