Abstract

Pediatric dural arteriovenous shunts (dAVSs) are a rare form of vascular disease: Fewer than 100 cases are reported in PubMed and the understanding of pediatric dAVS is limited. For this study, we searched in PubMed, reviewed and summarized the literature related to pediatric dAVSs. Our review revealed that pediatric dAVSs have an unfavorable natural history: If left untreated, the majority of pediatric dAVSs deteriorate. In a widely accepted classification scheme developed by Lasjaunias et al., pediatric dAVSs are divided into three types: Dural sinus malformation (DMS) with dAVS, infantile dAVS (IDAVS) and adult-type dAVS (ADAVS). In general, the clinical manifestations of dAVS can be summarized as having symptoms due to high-flow arteriovenous shunts, symptoms from retrograde venous drainage, symptoms from cavernous sinus involvement and hydrocephalus, among other signs and symptoms. The pediatric dAVSs may be identified with several imaging techniques; however, the gold standard is digital subtraction angiography (DSA), which indicates unique anatomical details and hemodynamic features. Effectively treating pediatric dAVS is difficult and the prognosis is often unsatisfactory. Transarterial embolization with liquid embolic agents and coils is the treatment of choice for the safe stabilization and/or improvement of the symptoms of pediatric dAVS. In some cases, transumbilical arterial and transvenous approaches have been effective, and surgical resection is also an effective alternative in some cases. Nevertheless, pediatric dAVS can have an unsatisfactory prognosis, even when timely and appropriate treatment is administered; however, with the development of embolization materials and techniques, the potential for improved treatments and prognoses is increasing.

Keywords: Angiography, brain circulation, cerebral venous drainage, dural arteriovenous shunt, dural sinus malformation, imaging, pediatrics, procedures, review, sinus thrombosis, therapy

Introduction

Dural arteriovenous shunts (dAVSs) account for 10–15% of all intracranial arteriovenous diseases and are rare in the pediatric population, with a reported incidence of 10%.1 In 2003, Barbosa et al.2 reviewed 620 cases of pediatric intracranial arteriovenous diseases that were reported from 1985 to 2003, and only 52 cases involved pediatric dAVSs. In 2013, there were 60 cases of pediatric dAVSs.3 Pediatric dAVS is complex and can include dural sinus malformation (DMS) with dAVS, infantile dAVS (IDAVS), and adult-type dAVS (ADAVS).4 Pediatric dAVS exhibit a more aggressive clinical course than adult dAVS. With a reported mortality rate > 25%, the treatment of large neonatal arteriovenous shunts (AVSs) is challenging.5 To date, the majority of the clinical experience with dAVS has been obtained from adult cases; however, the experience gained from adult cases cannot be applied to children, because of the growth and maturation of the skull, dura, vasculature, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways and the brain.6 Moreover, pediatric dAVS cases have a high mortality rate and are difficult to treat. Because there are few cases reported in PubMed, this study reviewed the literature on pediatric dAVS, in terms of their pathogenesis, classification, clinical presentation, treatment, prognosis and other characteristics.

Pathogenesis

Congenital developmental factor

The pathogenesis of pediatric dAVS remains elusive. Controversy exists regarding whether pediatric dAVS comprises congenital or acquired lesions. Most pediatric dAVS tend to be considered congenital. For example, pediatric dAVSs may be associated with DMSs, and an unknown trigger was postulated to cause the persistent ballooning of the posterior sinus, sinus wall overgrowth and development of abnormal venous spaces, which can lead to dAVS.7–9 In one case, De Haan et al.7 identified pathological evidence of abnormal sinus wall development and evidence of early compromise of cerebral venous drainage.

Hereditary and genetic mutation factor

Pediatric dAVS may be associated with syndromes derived from hereditary abnormalities, such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia syndrome, craniofacial arteriovenous metameric syndrome and cavernous malformations.10–12 These associations support the hypothesis that pediatric dAVS is hereditary. In addition, pediatric dAVSs may be accompanied by genetic-phenotypic mutations. For example, in 2016, Grillner et al.13 reported a spectrum of intracranial high-flow AVSs in RAS p21 protein activator 1 (RASA1) mutations, in which a case had a large DSM with dAVS between the meningeal arteries and the malformed superior sagittal sinus. In 2006, Srinivasa et al.14 reported the case of a 9-year-old child with dAVS with a frameshift mutation of the phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) tumor-suppressor gene.

Cerebral sinus thrombosis

Cerebral sinus thromboses may lead to dAVS in adults.15 Similar to adult dAVS, in rare situations the pediatric dAVSs may originate from cerebral sinus thromboses. The first definite case of this situation was reported by Morales et al.16 in 2010. A 5-month-old girl presented with a ruptured aneurysm, followed by extensive hemorrhaging and a right sigmoid sinus thrombosis, where a new, adult-type dAVS arose.16 In 2013, Walcott et al.12 suggested that cerebral sinus thrombosis may not be a rare cause of pediatric dAVS. Moreover, multiple dAVSs may simultaneously occur.17

Iatrogenic factor

Endovascular treatment may result in dAVSs.18 In 2012, Bai et al.19 reported the case of a 7-year-old boy with a cerebral arteriovenous fistula that was completely embolized; however, multiple de novo dAVS occurred as a result of hemodynamic changes following the embolization, and venous hypertension was considered the main causal factor of those dAVS. In another example, in 2013 Paramasivam et al.20 reported 4 cases of the de novo development of dAVSs following the embolization of pial arteriovenous fistulas. The post-operative blood flow in the draining vein or sinus became slow, and it induced thrombosis; and secondarily, localized hypertension, which initiated the pathogenesis of the dAVSs.20 In some cases, birth injuries induce sinus thromboses, and Ko et al.21 reported one case in 2010.

Natural history

The natural history of pediatric dAVS is unclear; however, a consensus has been reached that if treatment is not administered, pediatric dAVS may result in serious symptoms. In contrast to adults, in the early stage children primarily exhibit macrocrania, cardiac failure, increased intracranial pressure and other symptoms.22 In the late stage, a pediatric dAVS may rupture, which may result in subarachnoid and cerebral hemorrhages; moreover, as a result of the inhibition of CSF absorption, pediatric dAVS may cause focal neurological deficits via venous congestion or arterial steal.

Pediatric intracranial dAVS exhibits a more aggressive clinical course than adult dAVS, and the reported mortality rate is > 25%;23 however, in general, pediatric dAVS is often stable for a period of time and they are associated with well-tolerated congestive heart failure, until the dAVS regrows or the venous outlet is occluded by thrombosis.24 At the moment the hemodynamic equilibrium is broken, new symptoms or signs appear.14 In contrast to acquired dAVS in adults, these congenital pediatric dAVS have a very small chance of causing spontaneous occlusion; and very few cases of ADAVS have been reported in the cavernous sinus .25 There is a smaller chance of spontaneous occlusion with pediatric dAVS; however, dAVS may cause occlusion after a partial embolization.26

Pediatric dAVS classification

In 1996, Lasjaunias et al.4 divided pediatric intracranial dAVS into three groups: DSM with AVS, IDAVS and ADAVS:

In DSMs with dAVSs, two subtypes are recognized:

DSMs that involve the posterior sinus are typically characterized by giant dural lakes and slow-flow mural AV shunting;4 however, occasionally, the AV shunting is high flow.27 Spontaneous thrombosis or hypogenesis of one jugular bulb can be observed and leads to hemorrhagic infarction;

DSMs that involve the jugular bulb, other sinuses and normal sinuses appear as a sigmoid sinus-jugular bulb diaphragm; and these are associated with high-flow sinus AVS.

IDAVSs are high flow and low pressure: The draining of the venous sinus of an IDAVS is large and patent, there are no lakes and they are without sinus malformations. In rare instances, IDAVSs may drain into a developmental venous anomaly.23 IDAVSs may be multifocal.28–31 IDAVSs may also occur consecutively (For example: In 2007, Pan et al.32 reported the case of a 27-month-old girl in whom the IDAVS first occurred in the anterior base of the left middle cranial fossa; and then 2 years after radiotherapy, another dAVS occurred over the left transverse-sigmoid sinus region32; ADAVSs are similar in appearance and presentation to dAVSs in the adult population. ADAVSs may develop following thrombosis in the sinus wall or traumatic injuries to the sinus.1 ADAVSs are slow-flow arteriovenous shunts that typically develop within the walls of normal-sized sinuses; they are most frequently encountered in the cavernous sinus and rarely, in the sigmoid sinus. ADAVSs are very rare, including the cases that were reported by Konishi et al.33 in 1990 and Cohen et al.34 in 2008.

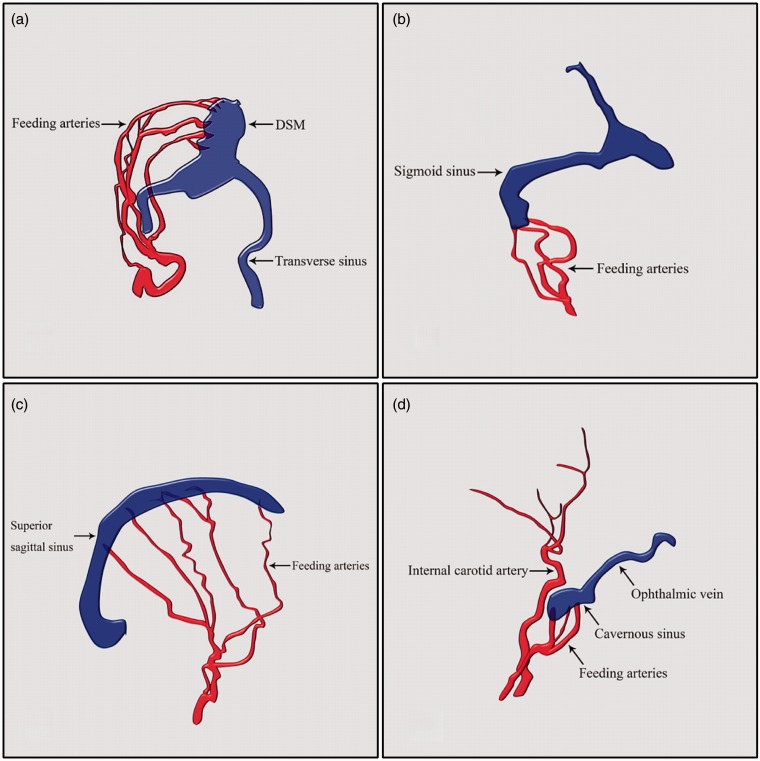

Representative images of DSM with dAVS, IDAVD and ADAVS are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Representative images of pediatric dAVS. (a) DSM with dAVS that involved the posterior sinus with giant dural lakes; (b) DSM with dAVS that involved the jugular bulb, other sinuses and normal sinuses that appear as a sigmoid sinus-jugular bulb ‘diaphragm’; (c) IDAVS without venous lakes or sinus malformations; (d) ADAVS in the cavernous sinus.

ADAVS: adult dural arteriovenous shunt; dAVS: dural arteriovenous shunt; DSM: dural sinus malformation; IDAVS: infant dural arteriovenous shunt.

Clinical manifestations

Pediatric dAVSs exhibit a slight predominance in males, in whom IDAVSs are most common. DSM with dAVS, IDAVS and ADAVS may occur in neonates. In general, DSMs with dAVSs are clinically expressed during the perinatal period; DSMs have also been diagnosed in utero. IDAVS are identified in infancy and early childhood, and the frequency of ADAVS increases with age.4 The presentation of pediatric dAVSs depends on the hemodynamic (cavernous capture or pial reflux) symptoms, including high-flow steal, venous drainage occlusion and mass effects.35 Hemorrhage is not a common initial presentation in infants or neonates with dAVSs.26 Pediatric dAVSs may be dormant for a long time prior to the occurrence of progressive symptoms. There are two causes for such dormancy: the persistence of high flow within the pial-induced shunts and progressive outlet restriction during skull base development with jugular stenosis or even occlusion.

Symptoms of high-flow arteriovenous shunts

Pediatric DSM with dAVS

The typical clinical manifestations are similar to the symptoms of intracranial high-flow pial arteriovenous fistulas, which often present with hyperdynamic heart failure, increased intracranial pressure, macrocrania, neurocognitive delay, seizures, and other signs and symptoms. DSMs with dAVSs involve the triad of macrocrania, a cranial bruit and signs of severe cardiac failure.9 For example, in 1996, Ross et al.27 reported a DSM with a high-flow dAVS in a neonate. In this case, the feeding arteries involved many branches of the external and internal carotid arteries, and there were giant dural lakes in the posterior sinus. As a result of the high-flow shunt, the patient presented with macrocrania and congestive cardiac failure. The patient died shortly after birth.27 In another example: In 2011, Prasanna et al.36 reported an eight-month-old male child with DSM with a high-flow dAVS; whom exhibited symptoms of respiratory distress, seizure, cardiac murmur and facial nevus with dilated veins. The bruit was predominantly located in the right frontal region.

IDAVS

IDAVS is the most common high-flow pediatric dAVS. Patients may manifest symptoms of a high-flow shunt11,23,37; however, in general, these symptoms develop gradually in IDAVSs. For example, in 1983, Albright et al.38 reported an IDAVS involving the torcular region. At 5 months after birth, the patient presented with macrocrania; at 14 months, the patient could not walk and at 23 months, a loud heart murmur, cranial bruit and thrill appeared; however, the majority of the neurological functions appeared normal. Thus, although the clinical onset often occurs in the first few years of life, the child's symptoms may be minor or well tolerated. In another example: In 2006, Srinivasa et al.14 reported a DSM in a high-flow IDAVS case. At birth, the patient presented with macrocrania and seizure, and these symptoms were stable until 9 years of age.14 The symptoms of IDAVS are complex; occasionally, the veins distal to the AVS can be involved. For example: In 2010, Thiex et al.39 described an 11-month-old child with a torcular dAVS that presented with increased head circumference as a result of the obstructed drainage, a captured cavernous sinus and posterior cortical venous drainage via the cavernous sinus into the superior ophthalmic, facial and scalp veins. The relevant symptoms and signs were present. In addition to the previously described symptoms, high-flow dAVS may lead to brain steal, which produces the relevant symptoms.35

Symptoms from retrograde venous drainage

In adults, dAVSs are typically supplied by the meningeal arteries and exhibit venous drainage either directly into the dural venous sinuses or via the cortical and meningeal veins. Borden Type II and III and Cognard Type IIb, IIa+b, III and IV lesions involve direct or indirect reflux into the cortical veins that causes more aggressive presentations, including hemorrhage and neurological deficits, and these symptoms are the basis of the widely used Cognard and Borden dAVS classifications.6 In pediatric dAVSs, the mechanisms and symptoms are the same. For example, in DSMs located on the midline: Because spontaneous thromboses may occur in the dural lake and dysplastic sinus, even if the dAVS is slow flowing, cerebral venous drainage may be compromised and may lead to subsequent venous infarction and intraparenchymatous hemorrhage. In 2006, Srinivasa et al.14 reported a case with a DSM and dAVS. At birth, the patient presented with macrocrania and seizures: These symptoms were stable until a thrombus formed in the sigmoid sinus, which resulted in most of the cerebral veins draining in the anterior through the collaterals into the orbital veins; persistent severe headaches and prominent periorbital veins also appeared.14

Symptoms of cavernous sinus involvement

In pediatric dAVSs, the ADAVSs present in older children and are nearly always located in the cavernous sinus or sigmoid sinus. The ADAVSs are typically small, occasionally partially thrombosed; and they may be secondary to another local event.35 The symptoms include venous hypertension, proptosis and chemosis. These are the same symptoms as in cavernous dural arteriovenous malformations in adults. For example: In 1995, Yamamoto et al.25 reported the case of a 5-week-old boy with a congenital dural caroticocavernous fistula. This patient presented with gradually progressive proptosis, dilated conjunctival veins, chemosis, abducens nerve palsy and an objective bruit.25 Other similar reported cases include Konishi et al.33 in 1990 and Cohen et al.34 in 2008. Furthermore, some dAVSs occur far from the cavernous sinus; however, when the draining vein or sinus is occluded by stenosis or thrombosis, the cavernous sinus may be captured, and symptoms such as facial venous distension and pulsatile proptosis may appear.24,40

Other symptoms

If a dAVS size is giant, the AVS may compress the cerebrospinal fluid circulation pathway, which results in hydrocephalus. For example, in 1986, Ross et al. reported a neonatal case of DSM with dAVS. This patient had giant dural lakes that led to serious hydrocephaly.27 The hydrocephaly was caused by poor venous drainage and venous hypertension, and it was resolved following interventional embolization treatment.26 Moreover, unilateral or bilateral jugular bulb stenoses and occlusions may lead to tonsillar prolapse and syringohydromyelia.41

Imaging manifestations

Several imaging techniques may be used to identify pediatric dAVSs, including CT, ultrasonography, MRI, MRA, DSA, and other methods. On CT, pediatric dAVSs may manifest as dilatations of the sinuses, a local mass effect, patchy enhancement, a decreased parenchymal density, and hydrocephaly. In some cases, a contrast CT scan is more useful.11

Prior to birth, ultrasonography may be useful when the dAVSs are sufficiently apparent.42 For example, in 2007, Herman et al. reported a DSM with an dAVS, and antenatal ultrasonography was used to identify the lesion8; however, it is difficult to identify the angioarchitecture of pediatric dAVSs with ultrasonography; thus, other imaging examinations are required to recognize the disease condition. MR arteriography and MR venography may clearly indicate the vascular structures of pediatric dAVSs.43 An early diagnosis with MR imaging is essential to determine the prognosis and potential treatment options because MR venography may be used to identify thromboses and stenoses in the draining vein and sinus.9 In recent years, the use of CT angiography for the diagnosis of dAVSs has increased. One study demonstrated 86% sensitivity and 100% specificity with CT angiography.44 Therefore, CT angiography is applicable to pediatric dAVSs; however, the gold standard for pediatric dAVSs is digital subtraction angiography (DSA). The current diagnostic capabilities of DSA enable this technique to provide unique anatomical details and hemodynamic features that are more detailed than the images provided by other techniques.45,46

Treatment

The treatment of pediatric AVSs is similar to the treatment of dural AVSs in adults, with several important differences. For adult dural AVSs, it is not rare to sacrifice the draining sinus during the occlusion of dAVS shunts47; however, in children, the therapeutic principle is to reduce or block the shunt while preserving the draining sinus because the vein system has not yet matured.48 In some cases, if sufficient collateral circulation of the venous sinus exists, it is feasible to sacrifice the draining sinus. To date, the treatment of paediatric dAVSs is primarily accomplished via endovascular embolization using both transarterial and transvenous approaches. In rare cases, transumbilical embolization has been used. Surgical resection is often used.49

Treatment of DSMs with AVSs

For children who exhibit DSMs with AVSs, the therapeutic goal is the early correction of the dAVS and the preservation of the compromised venous outflow via anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin. Once the venous outflow is occluded, the prognosis is very poor.14 Therefore, medical treatments with anticoagulants, diuretics, and inotropic agents have been used in this process to prevent dural sinus thrombosis.30

For DSMs with AVSs, a transarterial approach is currently the mainstream method. Occasionally, transumbilical arterial embolization may be performed. For example, in 2015, Oshiro et al. reported a female neonate who presented with congestive cardiac failure. MRI indicated a large DSM with a dAVS at the torcular herophili. Multiple embolizations in the meningeal feeders were performed with high-concentration glue and platinum coils. A follow-up angiography confirmed the absence of a dAVS.50 When necessary, the combination of transarterial and transvenous approaches is feasible.51 Moreover, transarterial and transvenous embolization via the umbilical venous route has been reported.49 When it is difficult to reach the pouch, the most direct method is to create a burr hole or needle puncture.52

In addition to endovascular treatment, the direct surgical approach may be used to resolve DSM with dAVS.53 In some cases, surgical or combined embolization may constitute an alternative. For example, in 2009, Johnson et al. reported a neonate with a torcular DSM who presented at birth with macrocephaly and high-output cardiac failure. The child initially underwent treatment via surgical clipping of the large main feeding artery. The DSM was subsequently resolved via interventional embolization treatment.26

Treatment of IDAVS

For children with IDAVS, the therapeutic principle is similar to adult dAVSs; however, the goal of the treatment is difficult to establish because the patency of the sinuses should be preserved, and incomplete cavernous capture suggests a high risk of directly sacrificing the sinus.11 In some cases, the endovascular embolization may be performed in stages to achieve gradual closure of the shunt, which provides time for sinus remodeling.21 In addition to the endovascular method, microsurgical resection may represent an alternative for simple IDAVSs.54

In recent years, Onyx has improved the therapeutic results of IDAVSs. For example, in 2010, Thiex et al.39 reported a series of pediatric vascular malformations in which two IDAVSs were included. Both patients had reversed cortical venous drainage, and staged Onyx embolizations associated with coils were performed. After many treatments, both patients achieved satisfactory recoveries, and the authors suggested the Onyx embolization of paediatric dAVSs was an efficacious treatment technique with an extremely low associated morbidity.39 For safer and longer injections into the IDAVS, a combination of Onyx and a new detachable tip microcatheter, SONIC (Balt, Montmorency, France), was helpful.55

When venous sinus draining is sufficient in some IDAVSs, the sinus sacrifice is feasible, and the potential to completely treat IDAVSs is improved.37 For example, in 2012, Niizuma et al. reported the case of a 20-month-old girl with IDAVS. DSA indicated a dAVS that involved the right transverse sinus. Because of the presence of sufficient venous draining, the right transverse sinus was transvenously embolized with platinum coils. The shunt subsequently recurred, and another embolization was performed, followed by the complete surgical resection of the right transverse sinus. In this case, the transverse sinus was sacrificed, and the patient had a good prognosis.56

In some cases of neonate treatment, the combined surgical/endovascular treatment of a complex IDAVS was necessary.9 For example, in 1983, Albright et al. reported an IDAVS in the confluence of the sinus; a partial embolization was initially performed, followed by a subtotal resection and an additional embolization for the residual vessels. Despite this extensive therapy, the IDAVS was not completely eradicated and ultimately recurred.38 Thus, the treatment of IDAVSs is very difficult in complex cases.

On rare occasions, radiosurgical techniques have been performed, particularly for multifocal IDAVSs because the multifocal nature of the arteriovenous shunts also limits the option of surgery. For example, in 2007, Pan et al. reported the case of a 27-month-old girl with 2 consecutive IDAVSs. Both of the fistulae were successfully obliterated with gamma knife radiosurgery.32 Therefore, radiosurgery may be attempted for those with IDAVSs and without life-threatening heart failure or venous infarction.

Treatment of ADAVS

ADAVSs are very rare in pediatric patients. Nearly all ADAVSs occur in the cavernous sinus, and fewer ADAVSs are located in the sigmoid sinus. For children with cavernous plexus adult-type shunts, embolization is the treatment of choice. Occasionally, when an ADAVS is found, the child may be too young to undergo endovascular embolization. In such cases, conservative treatment is the only option.

Spontaneous thrombosis and thrombosis following carotid compression have been observed but should not be expected. For example: In 1995, Yamamoto et al.25 reported on a 5-week-old boy with congenital ADAVS. After diagnosis by angiography and because the patient was found to be too young, conservative treatment was administered. The child's symptoms and signs spontaneously disappeared within a few weeks and did not recur for over 11 months: At this time, angiography indicated the continued presence of a small communication.25

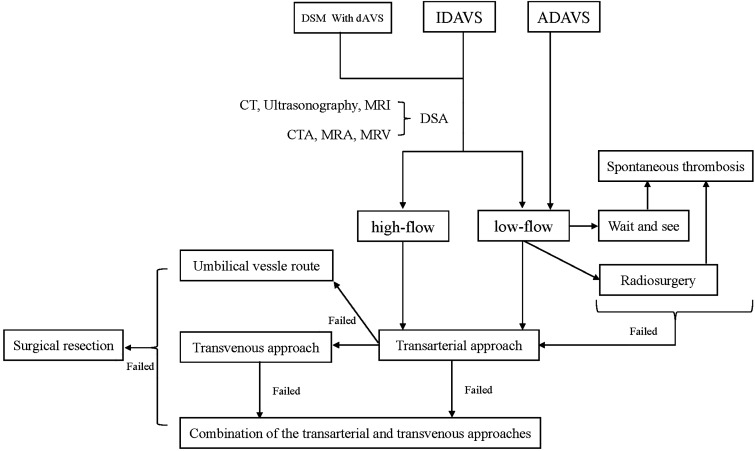

Some patients require treatment. For example: In 1990, Konishi et al.33 reported on a 2-month-old child whom was diagnosed with an ADAVS. The child was initially followed up for 1 year, to determine whether spontaneous thrombosis would occur.33 The symptoms persisted, and platinum coiling was performed for closure via the transarterial approach. After treatment, the symptoms were completely resolved.33 Similar cases were reported by Cohen et al.34 in 2008, who opted for coil treatment, and by Albayram et al.43 in 2004, who opted for N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate treatment. Satisfactory outcomes were achieved in both cases.34,43 The treatment protocol for pediatric dAVSs is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Treatment protocol of pediatric dAVSs.

ADAVS: adult-type dural arteriovenous shunt; CT: computed tomography; dAVS: dural arteriovenous shunt; DSM: dural sinus malformation; IDAVS: infantile dural arteriovenous shunt.

Necessity of anticoagulation

For pediatric dAVSs, especially in DSM with dAVS, thrombosis in the giant lakes or poaches is not uncommon, and the main factors include the combination of impaired venous drainage and venous dilatation, in which there is a sudden reduction in the blood flow. Thrombosis may occur spontaneously or after embolization. In 2014, Puccinelli et al.57 concluded that treatment by curative doses of low-molecular-weight heparin (plasma anti-Xa activity: 0.5e1 IU/ml) appears to be safe and effective until satisfactory vascular remodeling is obtained. In another example in 2010, Reig et al.37 recommended giving heparin for 1 week and low-molecular-weight heparin for 8 weeks until the next angiographic follow-up, with the goal of preserving the patency of the partially malformed sinus, even in cases with intracranial hemorrhages. Particularly in cases of DSMs with dAVSs, the patients typically proceed to total or partial spontaneous thrombosis prior to the age of 2 years, which therefore compromises the normal cerebral venous drainage.2

Prognosis and complications

Prognosis

Pediatric dAVSs have unsatisfying prognoses. Even following timely treatment, some patients will die within a short time.27 For example: In 1995, Morita et al.5 reported that the overall mortality rates were approximately 38% among all age groups and 67% among the neonatal subgroup; and in addition, that the occurrence of a DSM at the torcula was lethal.5 The mortality rate was 37.9% in a 2003 study by Barbosa et al.2; however, the overall rate decreased to 26% in a 2010 study by Ko.21 For example, in 2013, Walcott et al.12 reported a series of seven pediatric IDAVSs. Good recoveries were achieved in five cases.12 The better therapeutic outcomes may have resulted from advances in endovascular techniques; however, it should be noted that in pediatric dAVSs, even if a good immediate recovery is obtained, the patient's condition may deteriorate in the long term21,37; however, not all cases of pediatric dAVSs are associated with a poor recovery. Patients typically have favorable outcomes when the DSM is localized in the unilateral dural sinus, remote from the torcular herophili and the superior sagittal sinus; and when the DSM exhibits a small and/or slow dAVS, as a result of adequate alternate cerebral venous drainage in the event of involved sinus thrombosis or occlusion. These patients substantially benefit from endovascular treatment.2 The presence of bilateral cavernous sinus drainage and the absence of jugular bulb dysmaturation or occlusion are also favorable factors.7

Complications

Many complications, such as intracerebral hemorrhages, can be encountered during the treatment of IDAVSs. For example: In 2014, Appaduray et al.24 reported on three pediatric IDAVS treatments. Following the embolization of the fistulae via the transarterial approach, intracerebral hemorrhages occurred in two of those patients. This study analyzed the causes and the authors considered that the hemorrhages were secondary to the anticoagulation therapy. Anticoagulation therapy for dural sinus thrombosis improves outcomes, even in the presence of intracranial hemorrhages; however, the guidelines for the management of these lesions in the context of coexisting infantile dAVSs are unclear.24

In IDAVS, the sinus sump effect creates a pial AVS. These shunts are asymptomatic and may regress, following the occlusion of the primary dAVSs. For example in 1983, Albright et al.38 reported an IDAVS in the confluence of the sinus: Partial embolization was initially performed, followed by subtotal resection, and then an additional embolization was performed for the residual vessels. Despite this extensive therapy, the AVS was not completely eradicated and an occipital pial shunt developed. Because this type of shunt is asymptomatic and may regress following the treatment of the primary dAVS, there was no attempt to treat the pial shunt.38

Conclusions

Pediatric dAVSs are a rare vascular disease and can be divided into three types: DSM with dAVS, IDAVSs, and ADAVSs. Each type has its own characteristics, but in general, the clinical manifestations can be summarized as symptoms due to high-flow arteriovenous shunts, symptoms from retrograde venous drainage, symptoms from cavernous sinus involvement, symptoms from hydrocephaly, and other signs and symptoms. The treatment of pediatric dAVSs is difficult, and the prognoses are unsatisfactory. Transarterial embolization with liquid embolic agents and coils is the treatment of choice for the safe stabilization and/or improvement of the symptoms of pediatric dAVS. In some cases, transumbilical arterial and transvenous approaches can be effective; and in some cases, surgical resection is an alternative. Nevertheless, pediatric dAVSs can have an unsatisfactory prognosis, even with timely and appropriate treatment; however, with the ongoing development of embolization materials and techniques, improved treatments and prognoses are increasingly likely.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Souza MP, Willinsky RA, Terbrugge KG. Intracranial dural arteriovenous shunts in children. The Toronto experience. Interv Neuroradiol 2003; 9: 47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbosa M, Mahadevan J, Weon YC, et al. Dural sinus malformations (DSM) with giant lakes, in neonates and infants. Review of 30 consecutive cases. Interv Neuroradiol 2003; 9: 407–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JE, Gomori JM, Benifla M, et al. Endovascular management of sigmoid sinus dural arteriovenous fistula associated with sinus stenosis in an infant. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20: 168–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lasjaunias P, Magufis G, Goulao A, et al. Anatomoclinical aspects of dural arteriovenous shunts in children. Review of 29 cases. Interv Neuroradiol 1996; 2: 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita A, Meyer FB, Nichols DA, et al. Childhood dural arteriovenous fistulae of the posterior dural sinuses: Three case reports and literature review. Neurosurgery 1995; 37: 1193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piippo A, Niemela M, Van Popta J, et al. Characteristics and long-term outcome of 251 patients with dural arteriovenous fistulas in a defined population. J Neurosurg 2013; 118: 923–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Haan TR, Padberg RD, Hagebeuk EE, et al. A case of neonatal dural sinus malformation: Clinical symptoms, imaging and neuropathological investigations. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2008; 12: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herman TE, Siegel MJ. Congenital dural arteriovenous fistula at torcula herophili. Endovascular embolization. J Perinatol 2007; 27: 730–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowley RW, Evans AJ, Jensen ME, et al. Combined surgical/endovascular treatment of a complex dural arteriovenous fistula in 21-month-old. Technical note. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2009; 3: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratliff J, Voorhies RM. Arteriovenous fistula with associated aneurysms coexisting with dural arteriovenous malformation of the anterior inferior falx. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 1999; 91: 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bun YY, Ming CK, Ming CH, et al. Endovascular treatment of a neonate with dural arteriovenous fistula and other features suggestive of cerebrofacial arteriovenous metameric syndromes. Childs Nerv Syst 2009; 25: 383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walcott BP, Smith ER, Scott RM, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistulae in pediatric patients: Associated conditions and treatment outcomes. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grillner P, Soderman M, Holmin S, et al. A spectrum of intracranial vascular high-flow arteriovenous shunts in RASA1 mutations. Childs Nerv Syst 2016; 32: 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasa RN, Burrows PE. Dural arteriovenous malformation in a child with Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome. Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 1927–1929. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burch EA, Orbach DB. Pediatric central nervous system vascular malformations. Pediatr Radiol 2015; 45: S463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales H, Jones BV, Leach JL, et al. Documented development of a dural arteriovenous fistula in an infant subsequent to sinus thrombosis: Case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 2010; 52: 225–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witt O, Pereira PL, Tillmann W. Severe cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and dural arteriovenous fistula in an infant with protein S deficiency. Childs Nerv Syst 1999; 15: 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vassilyadi M, Mehrotra N, Shamji MF, et al. Pediatric traumatic dural arteriovenous fistula. Can J Neurol Sci 2009; 36: 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai Y, He C, Zhang H, et al. De novo multiple dural arteriovenous fistulas and arteriovenous malformation after embolization of cerebral arteriovenous fistula: Case report. Childs Nerv Syst 2012; 28: 1981–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paramasivam S, Toma N, Niimi Y, et al. De novo development of dural arteriovenous fistula after endovascular embolization of pial arteriovenous fistula. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko A, Filardi T, Giussani C, et al. An intracranial aneurysm and dural arteriovenous fistula in a newborn. Pediatr Neurosurg 2010; 46: 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toma AK, Davagnanam I, Ganesan V, et al. Cerebral arteriovenous shunts in children. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2013; 23: 757–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geibprasert S, Krings T, Pereira V, et al. Infantile dural arteriovenous shunt draining into a developmental venous anomaly. Interv Neuroradiol 2007; 13: 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Appaduray SP, King JA, Wray A, et al. Pediatric dural arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2014; 14: 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto T, Asai K, Lin YW, et al. Spontaneous resolution of symptoms in an infant with a congenital dural caroticocavernous fistula. Neuroradiology 1995; 37: 247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JN, Hartman TK, Barbaresi W, et al. Developmental outcomes for neonatal dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2009; 3: 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross DA, Walker J, Edwards MS. Unusual posterior fossa dural arteriovenous malformation in a neonate: Case report. Neurosurgery 1986; 19: 1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Monaco R, Rodesch G, Terbrugge K, et al. Multifocal dural arteriovenous shunts in children. Childs Nerv Syst 1991; 7: 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dogan M, Kahraman AS, Firat C, et al. Multiple dural arteriovenous fistulas involving the cavernous sinus, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus and spinal drainage: CT angiography findings in a 14-year-old boy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012; 16: 1305–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kincaid PK, Duckwiler GR, Gobin YP, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula in children: Endovascular treatment and outcomes in seven cases. Am J Neuroradiol 2001; 22: 1217–1225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ushikoshi S, Kikuchi Y, Miyasaka K. Multiple dural arteriovenous shunts in a 5-year-old boy. Am J Neuroradiol 1999; 20: 728–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan HC, Sheehan J, Huang CF, et al. Two consecutive dural arteriovenous fistulae in a child: A case report of successful treatment with gamma knife radiosurgery. Childs Nerv Syst 2007; 23: 1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konishi Y, Hieshima GB, Hara M, et al. Congenital fistula of the dural carotid-cavernous sinus: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1990; 27: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen JE, Gomori JM, Grigoriadis S, et al. Endovascular treatment of congenital carotid-cavernous fistulas in infancy. Neurol Res 2008; 30: 649–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iizuka Y, Koda E, Tsutsumi Y, et al. Neonatal dural arteriovenous fistula at the confluence presenting with paralysis of the orbicularis oris muscle. Neuroradiol J 2013; 26: 47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasanna Karanam LS, Baddam SR, Joseph S. Role of endovascular embolisation in treatment of pediatric dural arteriovenous fistula: A case report with a review of the literature. Neurol India 2011; 59: 917–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reig AS, Simon SD, Neblett WW, III, et al. Eight-year follow-up after palliative embolization of a neonatal intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with high-output heart failure: Management strategies for symptomatic fistula growth and bilateral femoral occlusions in pediatric patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2010; 6: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albright AL, Latchaw RE, Price RA. Posterior dural arteriovenous malformations in infancy. Neurosurgery 1983; 13: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thiex R, Williams A, Smith E, et al. The use of Onyx for embolization of central nervous system arteriovenous lesions in pediatric patients. Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cataltepe O, Berker M, Gurcay O, et al. An unusual dural arteriovenous fistula in an infant. Neuroradiology 1993; 35: 394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ApSimon HT, Ives FJ, Khangure MS. Cranial dural arteriovenous malformation and fistula. Radiological diagnosis and management. Australas Radiol 1993; 37: 2–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caponigro M, Filly RA, Dowd CF. Diagnosis of a posterior fossa dural arteriovenous fistula in a neonate by cranial ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med 1997; 16: 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Albayram S, Selcuk H, Ulus S, et al. Endovascular treatment of a congenital dural caroticocavernous fistula. Pediatr Radiol 2004; 34: 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narvid J, Do HM, Blevins NH, et al. CT angiography as a screening tool for dural arteriovenous fistula in patients with pulsatile tinnitus: Feasibility and test characteristics. Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez J, Amin AG, Gregg L, et al. Classification schemes of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2012; 23: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, et al. Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas: Clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology 1995; 194: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai LK, Liu HM, Jeng JS. Diagnosis and management of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Expert Rev Neurother 2016; 16: 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berenstein A, Ortiz R, Niimi Y, et al. Endovascular management of arteriovenous malformations and other intracranial arteriovenous shunts in neonates, infants and children. Childs Nerv Syst 2010; 26: 1345–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komiyama M, Nishikawa M, Kitano S, et al. Transumbilical embolization of a congenital dural arteriovenous fistula at the torcular herophili in a neonate. Case report. J Neurosurg 1999; 90: 964–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oshiro T, Nakayama O, Ohba C, et al. Transumbilical arterial embolization of a large dural arteriovenous fistula in a low-birth-weight neonate with congestive heart failure. Childs Nerv Syst 2016; 32: 723–726. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Komiyama M, Matsusaka Y, Ishiguro T, et al. Endovascular treatment of dural sinus malformation with arteriovenous shunt in a low birth weight neonate: Case report. Neurol Med Chir 2004; 44: 655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu H, Kuo M, Tu Y. Embolization of a giant torcular dural arteriovenous fistula in a neonate. Pediatr Neurosurg 1999; 30: 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monges JA, Galarza M, Sosa FP, et al. Direct surgical approach of a congenital dural arteriovenous fistula at the torcular herophili in a neonate: Case illustration. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan ST, Weeks RD. Dural arteriovenous malformation presenting as cardiac failure in a neonate. Acta Neurochir 1988; 91: 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maimon S, Strauss I, Frolov V, et al. Brain arteriovenous malformation treatment using a combination of Onyx and a new detachable tip microcatheter, SONIC: Short-term results. Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 947–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niizuma K, Sakata H, Koyama S, et al. [Childhood transverse sinus dural arteriovenous fistula treated with endovascular and direct surgery: A case report]. No Shinkei Geka 2012; 40: 1015–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Puccinelli F, Deiva K, Bellesme C, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis after embolization of pediatric AVM with jugular bulb stenosis or occlusion: Management and prevention. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2014; 18: 766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]