Existing data have suggested that rice intake was associated with elevated urinary excretion of total arsenic among pregnant women (1) and in a population in Bangladesh whose major staple food is rice (2). Moreover, evidence suggests that brown rice may contain more arsenic than white rice (3). In this research, we aimed to examine brown and white rice consumption in relation to urinary excretion of arsenic among U.S. adults.

The study population consisted of 6677 U.S. adults (≥20yr) in the 2003–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), who were randomly selected for urine arsenic analysis. Arsenic species were separated using high performance liquid chromatography. Because inorganic arsenic, i.e., arsenous acid and arsenic acid, had low detection rates (<5%), we derived inorganic arsenic excretion by subtracting most abundant organic arsenic, i.e., arsenobetaine, from the total arsenic concentration (4). We calculated average white rice and brown rice intake of these two nonconsecutive 24-hour recalls. The first recall was done during the in-person interview, and the second recall was conducted through a telephone interview 3–10 days later (5). In statistical analysis, we log-transformed excretion of arsenic and used generalized linear models to compare the urinary arsenic concentration in white-rice and brown-rice eaters. We took into account the sampling weights specifically for participants included in the arsenic assessments. We used SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to perform statistical analysis.

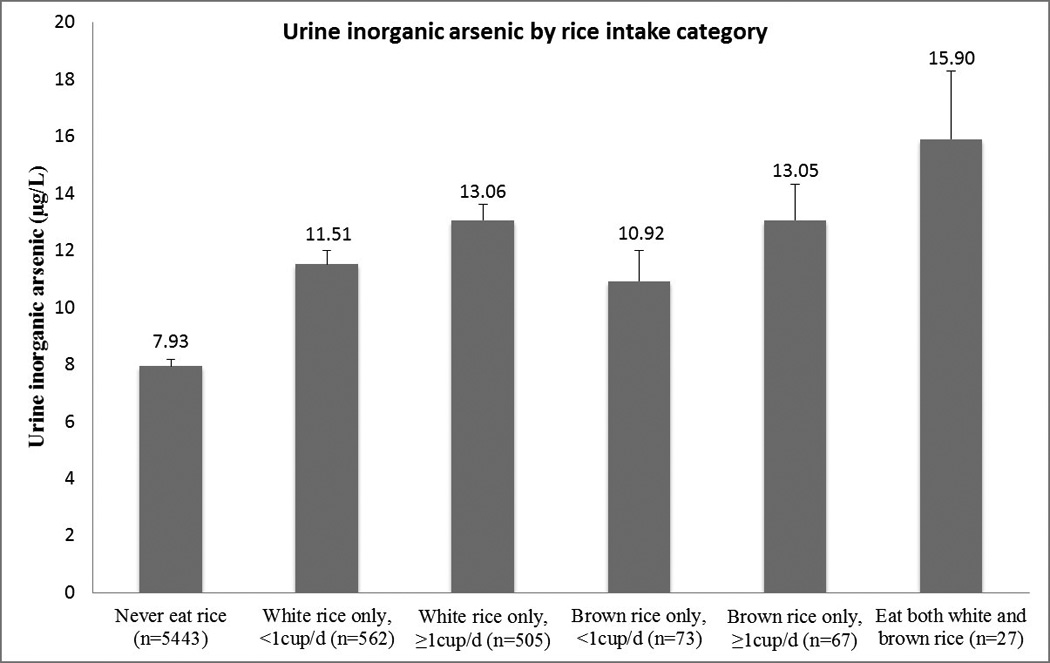

We observed that intakes of white and brown rice were both associated with higher total urinary arsenic concentrations, and the inorganic arsenic concentrations were not different between participants who primarily ate white rice versus those who ate brown rice: as shown in Figure 1 the geometric means±SE of inorganic arsenic were 7.93±0.24 µg/L for participants who did not eat rice (n=5443), 11.51±0.49 µg/L for those who ate < 1cup/d white rice only (n=562), and 13.06±0.56 µg/L for those who ate ≥ 1cup/d white rice only (n=505) (Ptrend<0.001). For brown rice eaters, the means were 10.92±1.07 µg/L for those who ate < 1cup/d brown rice only (n=73) and 13.05±1.25 µg/L for those who ate ≥ 1cup/d brown rice only (n=67) (Ptrend<0.001). There are only 27 participants who reported consuming both white rice and brown rice (mean total rice intake=2.14cup/d), and the geometric means±SE of their inorganic arsenic were 15.90±2.38 µg/L. Urine excretion of total arsenic and inorganic arsenic by participants’ characteristics are presented in eTable 1 (link)

Figure 1. Urinary concentration of inorganic arsenic by category of rice consumption.

Data are geometric means (in µg/L), adjusted for age (years), gender (male/female), race/ethnicity (white/black/Mexican American/others), body mass index (kg/m2), education (less than high school/high school/higher than high school), smoking status (never smoked/former smoker/current smoker) and urine creatinine level (mg/dL). Sample size in each category: Never eat rice (n=5443); White rice only, <1cup/d (n=562); White rice only, ≥1cup/d (n=505); Brown rice only, <1cup/d (n=73); Brown rice only, ≥1cup/d (n=67); Eat both white and brown rice (n=27).

To our knowledge, the present study compared for the first time the two main types of rice, i.e., brown vs white rice, in terms of their contributions to inorganic arsenic exposures. Arsenic is primarily localized in outer layers of the grain (3). As a result, brown rice grains typically have higher arsenic levels than polished white rice (6). Jackson et al. recently reported a high inorganic arsenic concentrations in organic brown rice syrup (7). In the current study, however, we did not observe a difference in urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic between participants who primary ate brown rice and those who primarily ate white rice, although the number of brown rice eaters was relatively small. One explanation for this finding is that the two-day recalls may not be able to capture the long-term rice consumption. In addition, the outer layer part of rice grain, i.e., the pericarp and aleurone layer, which are removed during polishing process, makes up only a minor part of the grain (around 14%). Thus, at the same intake amount, the relative differences in arsenic concentrations between brown and white rice are less than those between bran per se and white rice (8).

In summary, we found that consumption of white and brown rice showed similar associations with inorganic arsenic in urine. Data from prospective studies with larger sample size of rice eaters are needed to verify our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support This work was supported by a career development award R00HL098459 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (to Q.S.) and a Pilot and Feasibility Program sponsored by the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (DK46200).

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Gilbert-Diamond D, Cottingham KL, Gruber JF, et al. Rice consumption contributes to arsenic exposure in US women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(51):20656–20660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109127108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melkonian S, Argos M, Hall MN, et al. Urinary and dietary analysis of 18,470 bangladeshis reveal a correlation of rice consumption with arsenic exposure and toxicity. PloS one. 2013;8(11):e80691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meharg AA, Lombi E, Williams PN, et al. Speciation and localization of arsenic in white and brown rice grains. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(4):1051–1057. doi: 10.1021/es702212p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones MR, Tellez-Plaza M, Sharrett AR, et al. Urine arsenic and hypertension in US adults: the 2003–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Epidemiology. 2011;22(2):153–161. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318207fdf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: MEC in-person dietary interviewers procedures manual. [Accessed July 19, 2012];< http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/DIETARY_MEC.pdf>. US Department of Health and Human Services National Center for Health Statistics. 2002

- 6.Sun G-X, Williams PN, Carey A-M, et al. Inorganic Arsenic in Rice Bran and Its Products Are an Order of Magnitude Higher than in Bulk Grain. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42(19):7542–7546. doi: 10.1021/es801238p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson BP, Taylor VF, Karagas MR, et al. Arsenic, organic foods, and brown rice syrup. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(5):623–626. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ren X-L, Liu Q-L, Wu D-X, et al. Variations in concentration and distribution of health-related elements affected by environmental and genotypic differences in rice grains. Rice Science. 2006;13(3):170–178. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.