ABSTRACT

Transmissible self-assembled fibrous cross-β polymer infectious proteins (prions) cause neurodegenerative diseases in mammals and control non-Mendelian heritable traits in yeast. Cross-species prion transmission is frequently impaired, due to sequence differences in prion-forming proteins. Recent studies of prion species barrier on the model of closely related yeast species show that colocalization of divergent proteins is not sufficient for the cross-species prion transmission, and that an identity of specific amino acid sequences and a type of prion conformational variant (strain) play a major role in the control of transmission specificity. In contrast, chemical compounds primarily influence transmission specificity via favoring certain strain conformations, while the species origin of the host cell has only a relatively minor input. Strain alterations may occur during cross-species prion conversion in some combinations. The model is discussed which suggests that different recipient proteins can acquire different spectra of prion strain conformations, which could be either compatible or incompatible with a particular donor strain.

KEYWORDS: amyloid, prion variant, [PSI+], Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Saccharomyces paradoxus, Saccharomyces uvarum, Sup35

INTRODUCTION

Prions

Self-assembled fibrous cross-β polymers (amyloids) are associated with a variety of mammalian and human diseases including age-dependent Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, possibly type II diabetes, etc. (for review, see refs.1-5). Seeded polymerization of an amyloid occurs via immobilizing soluble protein of the same sequence into a fiber, and is accompanied by a conformational switch.2,6-8 This provides a basis for amyloid transmissibility. An extreme case of amyloids are infectious proteins (prions) that are transmitted between organisms and cause neurodegenerative diseases (in mammals), such as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs): sheep scrapie, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or “mad cow” disease, cervid chronic wasting disease (CWD) and human Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. These diseases are associated with the cross-β polymeric (prion) isoform of PrP protein that can convert normal cellular protein of the same sequence into a prion isoform.9,10 Cross-species prion transmission is usually impaired due to differences in the protein sequences of prion proteins. This phenomenon is termed as “species barrier.” However, in some cases the species barrier can be overcome. The cross-species BSE transmission to humans is a huge problem for the cattle industry and for public health, and the possibility of the cross-species transmission of CWD remains a concern.11-14 Our understanding of molecular mechanisms of the species barrier and cross-species prion transmission are still at rudimentary stage.

Yeast Prions

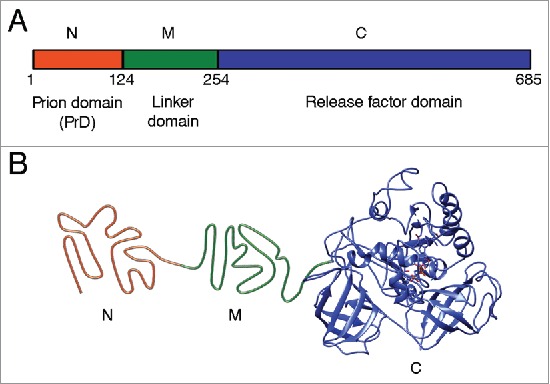

Prions are widespread among eukaryotic microorganisms, such as Saccharomyces yeast.15,16 Yeast prions provide a useful model for studying molecular basis of prion phenomena due to high rate of reproduction and safety for the researcher. Yeast prions control phenotypic traits inherited through the cytoplasm, therefore manifesting themselves as protein-based heritable determinants. About 1/3 of wild yeast strains exhibit traits inherited in a prion-like fashion, indicating that prions are widespread in nature.17 Yeast prion proteins contain regions that are responsible for prion propagation and are termed “prion domains” (PrDs).16,18 PrDs are typically distinct from regions essential for the major cellular function of a respective protein. Purified proteins (or PrDs) propagate an amyloid state in vitro and reproduce the prion upon transfection into yeast, confirming the “protein only” basis of prion phenomena.19-22 The best studied yeast prions [PSI+], [URE3], and [PIN+] (or [RNQ+]) are self-perpetuating amyloids of the proteins Sup35, Ure2 and Rnq1, respectively.15,16 Sup35 protein is the translation termination factor. When the Sup35 protein is in its prion form [PSI+], its translation termination activity is disrupted, so nonsense-codon read-through activity occurs,23 that is phenotypically detectable in specifically designed yeast strains.16,24 Sup35 protein consists of 3 regions: 1) N-terminal prion domain (Sup35N); 2) linker middle domain (Sup35M); and 3) functional C-terminal domain (Sup35C) responsible for translation termination and cell viability (Fig. 1). Truncated variant of protein consisting N and M domains are widely used as a model protein for studying amyloid aggregation in vitro, and can transmit prion conformation to the full-length Sup35.20,25,26

FIGURE 1.

Structural and functional organization of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sup35 protein. (A) Domain organization of Sup35. Designations N, M and C refer to the Sup35N (N-proximal), Sup35M (middle) and Sup35C (C-proximal) regions, respectively. Numbers correspond to amino acid positions. (B) Hypothetical model of tertiary structure of the non-prion isoform of Sup35. N domain is intrinsically unfolded, structure of M domain is unknown (shown as unfolded), the C domain structure is based on cryo-electron microscopy analysis (EMDB accession ID: 4crn).89

Prion Strains, or Variants

Prion proteins (including mammalian PrP and yeast Sup35) of one and the same sequence can form various amyloid conformations with distinct structures – prion “strains” (usually called “variants” in yeast).27-31 Different strains have different disease manifestation in mammals or phenotypic characteristics in yeast. In the case of yeast Sup35, “stronger” prion strains exhibit more severe translation termination defect, higher mitotic stability, a larger proportion of polymerized versus soluble protein, a smaller average polymer size, and a smaller size of the amyloid core region, protected from hydrogen-deuterium exchange, compared to “weaker” prion strains.28,32-36

Generally, each strain/variant is faithfully reproduced during prion transmission, although strain changes were also observed.37-45 It has been shown that the type of prion strain influences the species barrier properties in both yeast and mammals (for a review see ref. 46).

Yeast Models for Prion Species Barrier

Prion domains of yeast proteins quickly evolve in evolution, so that distantly related yeast genera show essentially no sequence homology in respective regions of Sup35 and typically exhibit strong transmission barriers.32,47-49 However, we50,51 and others52 have detected transmission barriers even between Sup35 proteins of the closely related yeast species, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, S. paradoxus and S. bayanus (now renamed as S. uvarum). Levels of similarity between the prion domains (Sup35N fragments) of these proteins (Table 1) are close to the range of variation observed among mammalian PrPs,53,54 which makes yeast system an appropriate model for studying general rules of the species barrier at relatively short phylogenetic distances. Notably, in some cases even intraspecies variation among S. cerevisiae Sup35 proteins from different strains may lead to transmission barriers.55 The current paper summarizes recent data about species prion barrier between closely related yeast and reviews data highlighting potential key determinants of cross-species prion transmission in yeast.

TABLE 1.

Identity of amino acid sequences for different domains of Sup35 protein from Saccharomyces paradoxus and S. uvarum in comparison to S. cerevisiae.

| Yeast species | N domain | M domain | C domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces paradoxus | 93.5% | 87% | 100% |

| Saccharomyces uvarum | 80% | 74% | 97% |

At Which Step Is the Species Barrier Controlled?

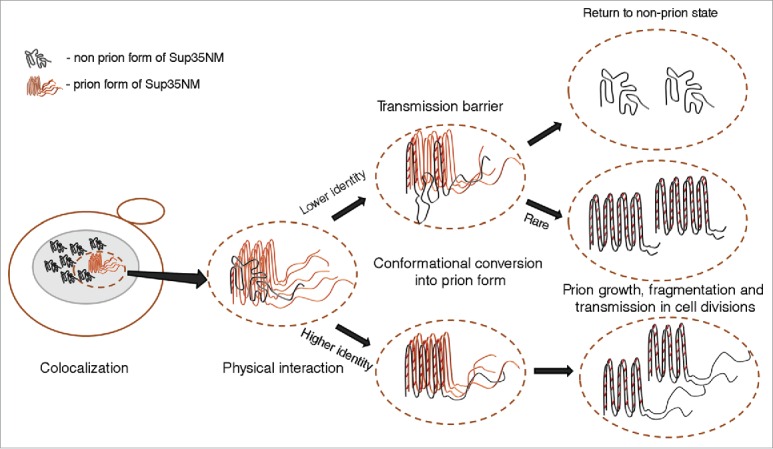

Transmission of prion state to a divergent protein may potentially involve 4 steps, as follows: (1) colocalization of 2 divergent proteins in one site within the cell; (2) physical interaction between colocalized proteins, leading to the formation of a heteroaggregate; (3) conformational conversion of newly joined non-prion protein into a prion form; (4) propagation of a prion, seeded by a divergent protein, in cell divisions (Fig. 2). Recent data (reviewed below) specifically address the issue of colocalization and coaggregation of divergent prionogenic proteins, and indicate that colocalization and coaggregation are not sufficient for cross-species prion transmission.

FIGURE 2.

Transmission of prion state to a divergent protein. Large ellipse on the left represents yeast cell. Gray area represents the cellular compartment or quality control protein deposit containing aggregating proteins. Dotted ellipse indicates the specific interacting protein molecules that are considered in more detail and at larger magnification in the images to the right. Nonprion form of heterologous Sup35 prion domain protein is represented as unstructured black tangle while prion polymers are shown by light (orange) (pre-existing “donor” prion) or dark (the newly formed heterologous prion) pleated lines demonstrating in-register parallel β-sheet architecture. Short crosscut lines indicate positions of interactions between β-sheets. Prion domains with high identity of amino acid sequences in the regions, corresponding to the cross-β core of a donor protein, can convert each other to prion form with high frequency, while prion proteins with lower identity typically cannot adopt the donor strain conformation and form nonprion aggregates; however, in rare cases, the recipient protein is converted to a prion conformation, that is only partly collinear to the original donor conformation, and partly different from it.

Fluorescence microscopy data show that divergent S. sensu stricto proteins colocalize with the pre-existing endogenous Sup35 prion in S. cerevisiae cells. Efficiency of colocolization depended on sequence divergence, as the colocalization between more closely related S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus proteins was higher than between more distantly related S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum proteins.50 Biochemical assays confirmed that the S. cerevisiae [PSI+] strain co-expressing heterologous (S. paradoxus or S. uvarum) Sup35 proteins contained both endogenous and heterologous proteins in an aggregated state, suggestive of coaggregation.50-52 However, despite colocalization and likely coaggregation, strong species barrier was observed between S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum Sup35 proteins, and in case of the weak prion strain (see below), also between S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus.50-52 These findings show that, despite colocalization, association with the S. cerevisiae prion and accumulation in the aggregated fraction, the heterologous Sup35 protein is not necessarily converted into the heritable prion form. Possibly, pre-existing prion of S. cerevisiae acts as a nucleus for aggregation of heterologous Sup35 protein, but fails to provide an efficient template for the formation of a new prion. This agrees with the previous report indicating that cross-species binding between mammalian PrPs is not sufficient for prion transmission.56

It is not yet entirely clears how divergent proteins colocalize in the cell and whether or not they form mixed heteroaggregates. Unrelated prionogenic proteins with prion domains of similar amino acid composition can cross-seed each other into the prion form as shown for example for the Rnq1 and Sup35 proteins in yeast.25,52,57 However, an interaction between these proteins is of transient nature and is observed only at early stages of the induction process, while persistent coaggregates are not formed and stable colocalization is not reported.58-60 It was shown that different amylodogenic proteins can be assembled in the form of ordered aggregates in the yeast quality control deposits, such as insoluble protein deposit, IPOD,61 or aggresome62,63 (that may represent a version of IPOD with a somewhat different intracellular location). However, the very distantly related Sup35 protein from the other yeast genera, Pichia does not colocalize with the preexisting S. cerevisiae Sup35 prion,50 suggesting that in case of more closely related proteins, colocalization might be not simply a result of co-sequestration into IPOD. Notably, mammalian amyloidogenic proteins PrP (associated with transmissible spongiform encephalopathies) and Aβ (associated with Alzheimer's disease) colocalize and even physically interact to each other (according to Förster resonance energy transfer, or FRET analysis) when co-expressed in yeast.64 These proteins are also shown to interact to each other in mammalian and human brains65-67 or in vitro,68 confirming that coaggregation in yeast likely reflects actual physiological interactions.

Thus, various prionogenic proteins of different sequences (either of yeast or mammalian origin) can colocalize and coaggregate (and at least in some cases, physically interact to each other) in yeast cells, but this is not sufficient for overcoming the species barrier. The specificity of prion transmission must be controlled at the steps following coaggregation.

What Is the Primary Determinant of the Species Barrier?

There are several factors that could potentially influence prion transmission, including differences in amino acid sequences, type of initial prion strain, chemical condition of aggregation reaction, and cell environment. Recent work in the Saccharomyces model has systematically address impact of these factors on cross-species prion transmission.

Role of Amino Acid Sequence

As expected, Sup35 PrDs with more similar sequences, e. g. those from S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus, exhibited higher frequency of cross species prion transmission, compared to PrDs with less similar sequences, e. g. those from S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum.50-52,69 However, experiments with the chimeric constructs have shown that the stringency of species barrier is not dependent on sequence divergence in a linear fashion, as different regions of Sup35 PrD have differential impact to the cross-species transmission.51,69 There are 3 major regions within Sup35 PrD, as follows: 1) N-terminal NQ-rich stretch (NQ); 2) region of oligopeptide repeats (ORs), and 3) the C-proximal region without an obvious sequence pattern. Interestingly, different regions played crucial roles in different cross-species combinations, with NQ region being a primary determinant of species specificity in the S. cerevisiae / S. paradoxus combination, and ORs region being a primary determinant of species specificity in the S. cerevisiae / S. uvarum combination. While differences in the C-proximal region of PrD did not play any significant role in the species barrier in our experiments, the amino acid substitution within this region (at position 109) has been reported by others to generate intraspecies prion transmission barrier between the Sup35 proteins from divergent S. cerevisiae strains.55 Overall, it appears that differences within specific amino acid stretches rather than overall sequence divergence play a key role in determining cross-species prion specificity.

Indeed, some individual species-specific amino acid substitutions within Sup35 PrD had strong impacts on transmission barrier, for example the substitutions at position 12 for the S. cerevisiae / S. paradoxus combination, or at the position 49 (in S. cerevisiae numbering) for the S. cerevisiae / S. uvarum combination.51 Intriguingly, in each case, the substitution in the divergent species disrupts the S. cerevisiae hexapeptide sequence corresponding to so called “amyloid stretch” consensus, found in the vast majority of proteins generating amyloids in vitro.70-72 While the role of “amyloid stretch” hexapeptides in vivo remains a matter of debate, it is an intriguing possibility that at least some of them may mark positions of initial cross-β structures formed in the process of conformational conversion, thus explaining an effect of these sequences on cross-species prion specificity.

Role of Prion Strain

In case of mammalian PrP, different strains of one and the same prion protein show different levels of cross-species prion transmission.73 The same pattern was detected for Saccharomyces Sup35.51 Moreover, effects of prion strains depended on the species combination. For example, the “strong” prion strain of S. cerevisiae Sup35 protein transfer to the protein with S. paradoxus Sup35 PrD more efficiently than the “weak” strain, while transmission of the same “strong” strain to the protein with S. uvarum was less efficient than for the same “weak” strain. Differential abilities of recipient proteins to be converted into a prion state by different strains of one and the same donor protein could be attributed to different sets of “strain” conformations that can be acquired by different protein sequences.

Prion strain properties also influenced the intraspecies transmission barrier caused by polymorphism at the position 109 of S. cerevisiae Sup35.55 Moreover, authors observed that in this case, clones with altered transmissibility patterns could be spontaneously generated by the donor strain. Such patterns persisted for certain number of cell divisions but eventually reverted back to the initial transmission specificity pattern. Authors interpreted this as a result of constant variation within the prion strain, producing new strains with altered parameters. This should however be noted that these new “strains” were not different from each other in any phenotypic characteristics, and their biochemical characterization has not been performed. Therefore, it remains unclear if differences between such “strains” are controlled by the same structural parameters as differences between phenotypically distinct and faithfully heritable strains. For example, it is possible that differences in transmission patterns could be determined by variations in the number of heritable prion units (propagons). Changes in the number of templates (that, once achieved, could be maintained for a certain number of generations) may alter transmission of the prion state to a divergent protein as well. Until detailed characterization is performed, this would be more logical to refer to such transient prion variants as “substrains.” Notably, formation of such substrains may depend on prion strain, conditions and/or yeast genotype, as other authors38 were not able to detect substrains using similar experimental model. In our experiments on cross-species prion transmission,50,51,69 we always analyzed a large number of independent samples for a given cross-species combination, each obtained from an individual culture. This minimized potential impact of substrains with altered specificity even in case they appeared.

Role of Conditions of the Aggregation Reaction

Both kinetics of aggregation reaction74-76 and predominant type of the amyloid strain formed are shown to be influenced by conditions such as temperature etc. 20,77 Our previous work demonstrated that salts of Hofmeister series influence both kinetics78 and strain preferences79 of amyloid formation by the fragment of Sup35 protein comprising N- and M domains (Sup35NM) in vitro. Specifically, strongly hydrated anions (kosmotropes) promote fast amyloid formation and elongation, and favored the formation of “strong” strains, while poorly hydrated anions (chaotropes) delayed nucleation, slowed down elongation and favored the formation of “weak” prion strains of Sup35 protein. These effects, initially described for S. cerevisiae Sup35NM, were confirmed for the Sup35NM proteins of S. paradoxus and S. uvarum.69 To determine if salt composition also influences the species specificity of prion transmission, we compared the intraspecies and cross-species prion seeding among S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus and S. uvarum Sup35NMs in all possible combinations, by using seeds obtained in different salts and performing cross-seeding in the presence of different salts in each case.69 Our data clearly demonstrated that species specificity of cross-seeding is influenced by the type of salt in which an initial seed was obtained. However, salt composition of the solution in which the cross-seeding reaction was performed influenced only kinetic parameters of aggregation without having any significant impact of species specificity. These results parallel our previous observations in vivo51 and confirm that the type of donor prion strain represents the key determinant of cross-species prion specificity, so that different salts influence specificity via favoring formation of different strains.

Role of the Cell Environment

Contribution of cell/organismal environment to cross-species specificity remained unclear until very recently. While it was proposed that differences in helper proteins (e. g. chaperones) or glycosylation patterns may contribute to prion species barrier in mammalian systems,80,81 systematic analysis of their inputs was difficult to perform. The Saccharomyces model allowed for the systematic comparison of prion transmission between Sup35 PrDs of various origins in the cells of 2 different yeast species, S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxs.69 For this purpose, we constructed a series of S. paradoxus strains carrying a marker that can be used to phenotypically monitor the Sup35 prion, and lacking the endogenous chromosomal SUP35 gene. Viability of such a strain was supported by the SUP35 gene located on a low-copy (centromeric) plasmid, so that SUP35 genes of various origins could be shuffled in and out at will of an experimentator, the approach that was identical to one of the strategies used previously for studying cross-species prion transmission in S. cerevisiae cells. In addition, we employed transfection with cell extracts to introduce the same S. cerevisiae prion strain that was previously used in the S. cerevisiae experiments into the S. paradoxus strain derivative bearing the S. cerevisiae SUP35 gene. Thus, experiments in S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus employed the exact same prion strain, the same set of divergent and chimeric genes, and the same experimental strategy, differing from each other only by cell environment. Somewhat counterintuitively, we found out that all the major patterns of the species barrier are conserved between the S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus cells, although some numerical differences were of course detected. Together with results showing that the major parameters of the species barrier can be reproduced with purified Saccharomyces Sup35NM protein fragments in vitro (see refs.50,69 and above), these data confirm that the identities of specific amino acid sequences and type of prion strain play a major role in the control of specificity of cross-species prion transmission, while cell environment (at least, in the yeast Sup35 model) makes only a relatively minor input.

Fidelity of the Cross-Species Prion Transmission

This is an important issue whether prion conformation of a certain strain is precisely transmitted to the protein of a divergent sequence, so that the same strain could be recovered if a prion state is reversely transmitted back to the original protein? The “prion adaptation” phenomenon described for mammalian PrP (for a review see ref.82) indicates that manifestation of strain-specific characteristics can be altered upon transmission of the prion state to a divergent protein. However, is this alteration reversible? The Saccharomyces model enabled us to address this question. Indeed, while phenotypic patterns of the Sup35 prion strain were altered after transmission to the protein with S. paradoxus PrD, the reverse transmission to the S. cerevisiae protein restored the patterns of the initial strain.51 Thus, to the extent allowed by the resolution of our approach, we concluded that the major structural parameters underlying the strain characteristics remained intact during transmission and propagation of the prion state by a divergent (but very closely related) protein. However, the situation was different in the S. cerevisiae / S. uvarum combination where the level of sequence divergence is higher. Indeed, the “strong” S. cerevisiae prion strain was irreversibly altered during propagation through the protein with S. uvarum PrD; moreover, reverse transmission from S. uvarum to S. cerevisiae generated a variety of prion strains, which were all weaker than the initial S. cerevisiae prion strain. Probably, Sup35 protein of S. uvarum can not adopt the same conformation as the “strong” prion variant of Sup35 S. cerevisiae due to steric constraints dictated by the divergence in amino acid sequences. Therefore, in rare cases when the species barrier is overcome, the S. uvarum protein acquires a conformation preferable for its prion domain, which then can be transmitted to S. cerevisiae Sup35 in the form of a “weak” prion strain (Fig. 2). Indeed, the species barrier between S. cerevisiae and S. uvarum is more pronounced in case of the “strong” prion strain rather than in the case of “weak” prion strain.51 It should be noted that once again, cell environment apparently plays a minor role in the conformation fidelity during the cross-species prion transmission, as similar results were detected in both S. cerevisiae and S. paradoxus cells.69

How does the strain switch occur during the cross-species prion transmission? One possibility is the “prion cloud” model, suggesting that prion strains in fact represent mixtures of the different derivatives or substrains, so that the donor derivatives with the higher conformational compatibility to the recipient protein are more likely to cross the barrier.27,55,80 However, it appears that one and the same isolate of S. uvarum prion can generate multiple prion strains after transmission to S. cerevisiae; moreover, these new strains initially appear to be unstable, generating new variants upon subsequent propagation.51 Such a scenario is more consistent with the “deformed templating” mechanism,83 and/or with so-called “secondary nucleation”84 when a pre-existing prion protein nucleates formation of a new prion that is not entirely identical to the pre-existing template. For example, β-strands in the regions that are involved in direct intermolecular interactions between the donor and recipient molecules could be reproduced precisely, while other β-strands between them could be formed de novo and fluctuate for a while until a stable structure is selected. The extreme case of such a secondary nucleation could be observed when heterologous protein of unrelated sequences but similar amino acid composition cross-seed aggregation of each other, e. g. in case of Rnq1 and Sup35. Indeed, PrD of Sup35 protein from Pichia methanolica, having essentially no sequence homology but exhibiting a similarity of amino acid composition with PrD of Sup35 from S. cerevisiae, can induce formation of the Sup35 prion when overproduced,47,48 and even transmit prion state to the S. cerevisiae Sup35 protein at normal levels.85 However, frequency of such non-templated cross-seeding between unrelated or distantly related proteins is much less than in case of prion transmission between S. uvarum and S. cerevisiae, suggesting that the latter process includes both templated (through interaction between identical or nearly identical sequences) and non-templated components.

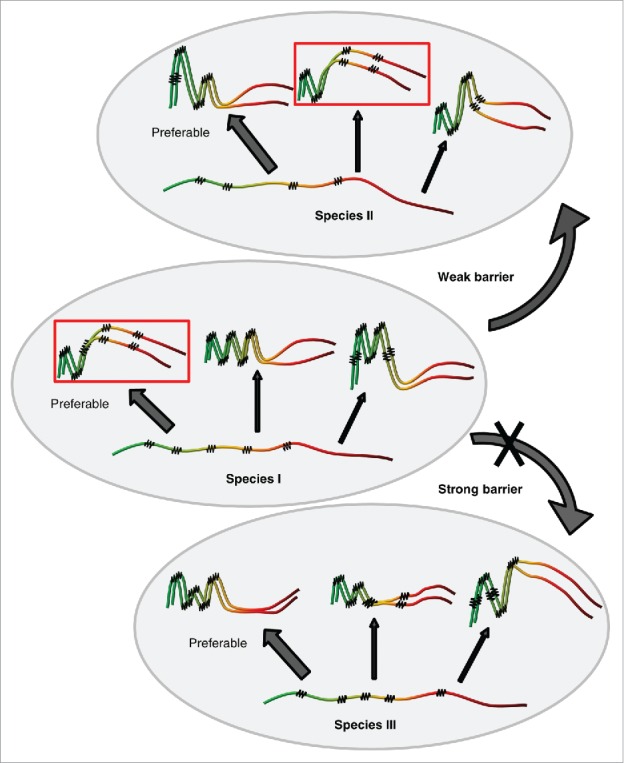

Model for Cross-Species Prion Transmission

The following model explains the role of sequence similarity and conformational state of prion protein in the species barrier (Fig. 3). Different protein sequences are likely to differ from each other both in the spectra of possible prion variants they can form, and in the preferences in regard to which variant(s) is (are) predominantly formed and is (are) most kinetically stable in given conditions. Indeed, a substitution of the specific single amino acid residue may lead to dramatic changes in the ability of such a protein to form/propagate some prion strains.36,38,86,87 Thus, divergent prion proteins generate different, although in some cases partly overlapping sets of strains. Notably, strain preferences also depend on the conditions in which initial protein aggregation has occurred.

FIGURE 3.

Model for cross-species prion transmission. Large gray ellipses correspond 3 different yeast species. Non-prion form of PrD domain of Sup35 protein is shown as wavy line, while prion polymers are shown by pleated lines demonstrating in-register parallel β-sheet architecture. Zigzags correspond to turns between β-strands. Prion strains formed by one and the same protein differ from each other by both size/location of cross-β regions, and positions of turns. Due to differences in amino acid sequences, homologous proteins from different species can generate different spectra of strains. Each species has a preferable strain conformation (pointed to by a thick arrow), and different strains may have different preferable conformations. When prion proteins from different species can adopt similar conformations (as in examples within the rectangles), and a donor protein prefers such a conformation (or is present in such a conformation in the specific experiment), cross-species prion transmission may occurs relatively efficiently, and prion species barrier is weak (as shown for species I and II on this Figure). When prion proteins from different species do not produce strains of identical or similar conformations, strong species barrier is detected (as shown for species I and III on this Figure).

Strain conformations apparently control specificity of prion transmission between divergent proteins. If donor conformation is not formed or is strongly disfavored by a recipient protein, the cross-species prion transmission would be greatly reduced (Fig. 3). This explains why the prion species barrier depends on a donor strain. For example, the “weak” prion strain of S. cerevisiae could be transmitted to the S. uvarum protein with a higher efficiency, compared to a “strong” strain,51 because Sup35 PrD of S. uvarum cannot readily form a conformation similar to a “strong” prion form of S. cerevisiae PrD but can adopt a conformation similar to a “weak” form. Indeed, a Sup35 protein with S. uvarum PrD can form only weak prion strains in S. cerevisiae.50,51 Moreover, in rare cases when strong strain of S. cerevisiae is transmitted to S. uvarum, reverse transmission of this prion back to S. cerevisiae protein results in the formation of weak strains.51 Thus, a conformation of the strong S. cerevisiae strain cannot be propagated by S. uvarum, and in the process of cross-species prion transmission, the protein another prion conformation that is better agreed with the S. uvarum strain preferences.

This model also explains the asymmetry of cross-species prion barrier, phenomenon that is detected as a decreased efficiency of prion transmission between 2 divergent proteins in one direction, compared to the opposite direction.50-52,88 Efficient transmission may occur when donor strain conformation is compatible with a recipient protein, while impaired transmission corresponds to the situation when donor protein is present in a prion conformation that is not formed or is disfavored by a recipient protein.

Conclusions

Recent research using the Saccharomyces model provided significant new insights into the mechanism of prion species barrier. Major determinants of prion specificity were identified, and stages at which cross-species specificity is controlled were determined. Overall, data agree with the model postulating that both protein sequence and cell physiology or environment modulate cross-species prion conversion primarily via influencing conformational preferences of prion formation, that results in generation of prion variants (strains) which are either compatible (barrier) or incompatible (cross-species transmission) with the recipient protein.

Future Perspectives

The next challenge in deciphering the rules of species barrier is related to determining the molecular basis of the strain preferences for various prion protein sequences, and to elucidation of molecular foundations of physical interactions between heterologous proteins in the process of prion transmission. This requires high resolution structural studies of prion strains and of heteroaggregates formed by prion proteins of divergent sequences.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- CWD

cervid chronic wasting disease

- IPOD

insoluble protein deposit

- NQ

N-terminal NQ-rich stretch within Sup35 prion domain

- ORs

region of oligopeptide repeats within Sup35 prion domain

- PrDs

prion domains

- Sup35C

functional C-terminal domain of Sup35 protein

- Sup35M

linker middle domain of Sup35 protein

- Sup35N

N-terminal prion domain of Sup35 protein

- Sup35NM

fragment of Sup35 protein comprising N- and M domains

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants 14-50-00069 from Russian Science Foundation (YOC and AAR) and 15-04-06650 from Russian Foundation for Basic Research (YOC). AVG was supported by Postdoctoral Fellowship 1.50.1038.2014 from St. Petersburg State University and grant from the Dynasty Foundation.

REFERENCES

- [1].Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Annals Neurol 2011; 70:532-40; PMID:22028219; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ana.22615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moreno-Gonzalez I, Soto C. Misfolded protein aggregates: mechanisms, structures and potential for disease transmission. Seminars Cell Dev Biol 2011; 22:482-7; PMID:21571086; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kraus A, Groveman BR, Caughey B. Prions and the potential transmissibility of protein misfolding diseases. Annu Rev Microbiol 2013; 67:543-64; PMID:23808331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goedert M. Neurodegeneration. Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Abeta, tau, and α-synuclein. Science 2015; 349:1255555; PMID:26250687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1255555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Aguzzit A, Lakkaraju AK. Cell biology of prions and prionoids: A status report. Trends Cell Biol 2016; 26:40-51; PMID:26455408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wisniewski T, Sigurdsson EM. Therapeutic approaches for prion and Alzheimer's diseases. FEBS J 2007; 274:3784-98; PMID:17617224; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Park DC. Beta-amyloid deposition and the aging brain. Neuropsychol Rev 2009; 19:436-50; PMID:19908146; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11065-009-9118-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aguzzi A, O'Connor T. Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9:237-48; PMID:20190788; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Perspectives on prion biology, prion disease pathogenesis, and pharmacologic approaches to treatment. Clin Lab Med 2003; 23:1-41; PMID:12733423; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0272-2712(02)00041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weissmann C. The state of the prion. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004; 2:861-71; PMID:15494743; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrmicro1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Moore RA, Vorberg I, Priola SA. Species barriers in prion diseases–brief review. Arch Virol Suppl 2005; (19):187-202; PMID:16355873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aguzzi A, Falsig J. Prion propagation, toxicity and degradation. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15:936-9; PMID:22735515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.3120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Belay ED, Schonberger LB. The public health impact of prion diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26:191-212; PMID:15760286; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barria MA, Telling GC, Gambetti P, Mastrianni JA, Soto C. Generation of a new form of human PrP(Sc) in vitro by interspecies transmission from cervid prions. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:7490-5; PMID:21209079; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.198465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wickner RB, Edskes HK, Shewmaker F, Nakayashiki T, Engel A, McCann L, Kryndushkin D. Yeast prions: evolution of the prion concept. Prion 2007; 1:94-100; PMID:19164928; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.1.2.4664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liebman SW, Chernoff YO. Prions in yeast. Genetics 2012; 191:1041-72; PMID:22879407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.111.137760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Halfmann R, Jarosz DF, Jones SK, Chang A, Lancaster AK, Lindquist S. Prions are a common mechanism for phenotypic inheritance in wild yeasts. Nature 2012; 482:363-8; PMID:22337056; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Inge-Vechtomov SG, Zhouravleva GA, Chernoff YO. Biological roles of prion domains. Prion 2007; 1:228-35; PMID:19172114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.1.4.5059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].King CY, Diaz-Avalos R. Protein-only transmission of three yeast prion strains. Nature 2004; 428:319-23; PMID:15029195; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS. Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature 2004; 428:323-8; PMID:15029196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Patel BK, Liebman SW. “Prion-proof” for [PIN+]: infection with in vitro-made amyloid aggregates of Rnq1p-(132-405) induces [PIN+]. J Mol Biol 2007; 365:773-82; PMID:17097676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Brachmann A, Baxa U, Wickner RB. Prion generation in vitro: amyloid of Ure2p is infectious. EMBO J 2005; 24:3082-92; PMID:16096644; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cox B. Cytoplasmic inheritance - prion-like factors in yeast. Curr Biol 1994; 4:744-8; PMID:7953567; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chernova TA, Wilkinson KD, Chernoff YO. Physiological and environmental control of yeast prions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014; 38:326-44; PMID:24236638; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/1574-6976.12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN(+)]. Cell 2001; 106:171-82; PMID:11511345; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00427-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Tanaka M, Weissman JS. An efficient protein transformation protocol for introducing prions into yeast. Method Enzymol 2006; 412:185-200; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science 2007; 318:930-6; PMID:17991853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1138718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Derkatch IL, Chernoff YO, Kushnirov VV, IngeVechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Genesis and variability of [PSI] prion factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 1996; 144:1375-86; PMID:8978027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schlumpberger M, Prusiner SB, Herskowitz I. Induction of distinct [URE3] yeast prion strains. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21:7035-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bradley ME, Liebman SW. Destabilizing interactions among [PSI+] and [PIN+] yeast prion variants. Genetics 2003; 165:1675-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morales R, Abid K, Soto C. The prion strain phenomenon: molecular basis and unprecedented features. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1772:681-91; PMID:17254754; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kushnirov VV, Kryndushkin DS, Boguta M, Smirnov VN, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Chaperones that cure yeast artificial [PSI+] and their prion-specific effects. Curr Biol 2000; 10:1443-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Borchsenius AS, Muller S, Newnam GP, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Chernoff YO. Prion variant maintained only at high levels of the Hsp104 disaggregase. Current Genetics 2006; 49:21-9; PMID:16307272; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00294-005-0035-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou P, Derkatch IL, Uptain SM, Patino MM, Lindquist S, Liebman SW. The yeast non-Mendelian factor [ETA(+)] is a variant of [PSI+], a prion-like form of release factor eRF3. EMBO J 1999; 18:1182-91; PMID:10064585; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kryndushkin DS, Alexandrov IM, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Kushnirov VV. Yeast [PSI+] prion aggregates are formed by small Sup35 polymers fragmented by Hsp104. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:49636-43; PMID:14507919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M30799-6200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Toyama BH, Kelly MJ, Gross JD, Weissman JS. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature 2007; 449:233-7; PMID:17767153; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shkundina IS, Kushnirov VV, Tuite MF, Ter-Avanesyan MD. The role of the N-terminal oligopeptide repeats of the yeast Sup35 prion protein in propagation and transmission of prion variants. Genetics 2006; 172:827-35; PMID:16272413; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.105.048660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Huang YW, Chang YC, Diaz-Avalos R, King CY. W8, a new Sup35 prion strain, transmits distinctive information with a conserved assembly scheme. Prion 2015; 9:207-27; PMID:26038983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19336896.2015.1039217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chernoff YO. Mutations and natural selection in the protein world. J Mol Biol 2011; 413:525-6; PMID:21854786; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kimberlin RH, Walker CA. Pathogenesis of Scrapie (Strain-263k) in Hamsters infected intracerebrally, intraperitoneally or intraocularly. J General Virol 1986; 67:255-63; PMID:3080549; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1099/0022-1317-67-2-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li JL, Browning S, Mahal SP, Oelschlegel AM, Weissmann C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science 2010; 327:869-72; PMID:20044542; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1183218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mahal SP, Browning S, Li JL, Suponitsky-Kroyter I, Weissmann C. Transfer of a prion strain to different hosts leads to emergence of strain variants. P Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:22653-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1013014108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Angers RC, Kang HE, Napier D, Browning S, Seward T, Mathiason C, Balachandran A, McKenzie D, Castilla J, Soto C, et al.. Prion strain mutation determined by prion protein conformational compatibility and primary structure. Science 2010; 328:1154-8; PMID:20466881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1187107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ghaemmaghami S, Watts JC, Nguyen HO, Hayashi S, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Conformational transformation and selection of synthetic prion strains. J Mol Biol 2011; 413:527-42; PMID:21839745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Roberts BE, Duennwald ML, Wang H, Chung C, Lopreiato NP, Sweeny EA, Knight MN, Shorter J. A synergistic small-molecule combination directly eradicates diverse prion strain structures. Nat Chem Biol 2009; 5:936-46; PMID:19915541; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bruce KL, Chernoff YO. Sequence specificity and fidelity of prion transmission in yeast. Seminars Cell Dev Biol 2011; 22:444-51; PMID:21439395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chernoff YO, Galkin AP, Lewitin E, Chernova TA, Newnam GP, Belenkiy SM. Evolutionary conservation of prion-forming abilities of the yeast Sup35 protein. Mol Microbiol 2000; 35:865-76; PMID:10692163; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kushnirov VV, Kochneva-Pervukhova N, Chechenova MB, Frolova NS, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Prion properties of the Sup35 protein of yeast Pichia methanolica. EMBO J 2000; 19:324-31; PMID:10654931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/19.3.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Santoso A, Chien P, Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Molecular basis of a yeast prion species barrier. Cell 2000; 100:277-88; PMID:10660050; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81565-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chen B, Newnam GP, Chernoff YO. Prion species barrier between the closely related yeast proteins is detected despite coaggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:2791-6; PMID:17296932; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611158104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chen B, Bruce KL, Newnam GP, Gyoneva S, Romanyuk AV, Chernoff YO. Genetic and epigenetic control of the efficiency and fidelity of cross-species prion transmission. Mol Microbiol 2010; 76:1483-99; PMID:20444092; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07177.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Afanasieva EG, Kushnirov VV, Tuite MF, Ter-Avanesyan MD. Molecular basis for transmission barrier and interference between closely related prion proteins in yeast. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:15773-80; PMID:21454674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.183889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wopfner F, Weidenhofer G, Schneider R, von Brunn A, Gilch S, Schwarz TF, Werner T, Schatzl HM. Analysis of 27 mammalian and 9 avian PrPs reveals high conservation of flexible regions of the prion protein. J Mol Biol 1999; 289:1163-78; PMID:10373359; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sandula J, Vojtkova-Lepsikova A. Immunochemical studies on mannans of the genus Saccharomyces. Group of Saccharomyces sensu stricto species. Folia Microbiologica 1974; 19:94-101; PMID:4215716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02872841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bateman DA, Wickner RB. [PSI+] Prion transmission barriers protect saccharomyces cerevisiae from iinfection: intraspecies ‘Species Barriers’. Genetics 2012; 190:569-79; PMID:22095075; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.111.136655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Horiuchi M, Priola SA, Chabry J, Caughey B. Interactions between heterologous forms of prion protein: binding, inhibition of conversion, and species barriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97:5836-41; PMID:10811921; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.110523897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Osherovich LZ, Weissman JS. Multiple Gln/Asn-rich prion domains confer susceptibility to induction of the yeast [PSI(+)] prion. Cell 2001; 106:183-94; PMID:11511346; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00440-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Derkatch IL, Uptain SM, Outeiro TF, Krishnan R, Lindquist SL, Liebman SW. Effects of Q/N-rich, polyQ, and non-polyQ amyloids on the de novo formation of the [PSI+] prion in yeast and aggregation of Sup35 in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:12934-9; PMID:15326312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0404968101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Arslan F, Hong JY, Kanneganti V, Park SK, Liebman SW. Heterologous aggregates promote de novo prion Appearance via more than one mechanism. Plos Genet 2015; 11:e1004814; PMID:25568955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Du ZQ, Li LM. Investigating the interactions of yeast prions: [SWI+], [PSI+], and [PIN+]. Genetics 2014; 197:685-700; PMID:24727082; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.114.163402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kaganovich D, Kopito R, Frydman J. Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature 2008; 454:1088-95; PMID:18756251; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang L. Towards revealing the structure of bacterial inclusion bodies. Prion 2009; 3:139-45; PMID:19806034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.3.3.9922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gong H, Romanova NV, Allen KD, Chandramowlishwaran P, Gokhale K, Newnam GP, Mieczkowski P, Sherman MY, Chernoff YO. Polyglutamine toxicity is controlled by prion composition and gene dosage in yeast. Plos Genet 2012; 8:223-35; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Rubel AA, Ryzhova TA, Antonets KS, Chernoff YO, Galkin A. Identification of PrP sequences essential for the interaction between the PrP polymers and Aβ peptide in a yeast-based assay. Prion 2013; 7:469-76; PMID:24152606; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.26867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-β oligomers. Nature 2009; 457:1128-32; PMID:19242475; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kudo W, Petersen RB, Lee HG. Cellular prion protein and Alzheimer disease Link to oligomeric amyloid-β and neuronal cell death. Prion 2013; 7:114-6; PMID:23154635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.22848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Resenberger UK, Harmeier A, Woerner AC, Goodman JL, Muller V, Krishnan R, Vabulas RM, Kretzschmar HA, Lindquist S, Hartl FU, et al.. The cellular prion protein mediates neurotoxic signalling of β-sheet-rich conformers independent of prion replication. EMBO J 2011; 30:2057-70; PMID:21441896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chen SG, Yadav SP, Surewicz WK. Interaction between human prion protein and amyloid-β (Abeta) oligomers: Role of N-terminal residues. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:26377-83; PMID:20576610; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.145516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Sharma A, Bruce KL, Chen BX, Gyoneva S, Behrens SH, Bommarius AS, Chernoff YO. Contributions of the prion protein sequence, strain, and environment to the species barrier. J Biol Chem 2016; 291:1277-88; PMID:26565023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M115.684100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Bateman DA, Wickner RB. The [PSI+] prion exists as a dynamic cloud of variants. PLOS Genet 2013; 9:e1003257; PMID:23382698; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].de la Paz ML, Serrano L. Sequence determinants of amyloid fibril formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101:87-92; PMID:14691246; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.2634884100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Pastor MT, Esteras-Chopo A, Serrano L. Hacking the code of amyloid formation: the amyloid stretch hypothesis. Prion 2007; 1:9-14; PMID:19164912; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.1.1.4100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Hill AF, Collinge J. Prion strains and species barriers. Contributions Microbiol 2004; 11:33-49; PMID:15077403; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000077061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Munishkina LA, Henriques J, Uversky VN, Fink AL. Role of protein-water interactions and electrostatics in α-synuclein fibril formation. Biochemistry-US 2004; 43:3289-300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi034938r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Diaz-Espinoza R, Mukherjee A, Soto C. Kosmotropic anions promote conversion of recombinant prion protein into a PrPSc-like misfolded form. Plos One 2012; 7:e31678; PMID:22347503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0031678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lodderstedt G, Sachs R, Faust J, Bordusa F, Kuhn U, Golbik R, Kerth A, Wahle E, Balbach J, Schwarz E. Hofmeister salts and potential therapeutic compounds accelerate in vitro fibril formation of the N-terminal domain of PABPN1 containing a disease-causing alanine extension. Biochem-US 2008; 47(7):2181-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi701322g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ohhashi Y, Ito K, Toyama BH, Weissman JS, Tanaka M. Differences in prion strain conformations result from non-native interactions in a nucleus. Nat Chem Biol 2010; 6:225-30; PMID:20081853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Yeh V, Broering JM, Romanyuk A, Chen B, Chernoff YO, Bommarius AS. The Hofmeister effect on amyloid formation using yeast prion protein. Protein Sci 2010; 19:47-56; PMID:19890987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/pro.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Rubin J, Khosravi H, Bruce KL, Lydon ME, Behrens SH, Chernoff YO, Bommarius AS. Ion-specific effects on prion nucleation and strain formation. J Biol Chem 2013; 288:30300-8; PMID:23990463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M113.467829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95:13363-83; PMID:9811807; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Aguzzi A, Sigurdson C, Heikenwaelder M. Molecular mechanisms of prion pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol-Mech 2008; 3:11-40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Collinge J. Prion strain mutation and selection. Science 2010; 328:1111-2; PMID:20508117; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1190815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Baskakov IV. The many shades of prion strain adaptation. Prion 2014; 8:169-72; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/pri.27836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Cohen SI, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Knowles TP. Nucleated polymerization with secondary pathways. II. Determination of self-consistent solutions to growth processes described by non-linear master equations. J Chem Phys 2011; 135:065107; PMID:21842956; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1063/1.3608918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Vishveshwara N, Liebman SW. Heterologous cross-seeding mimics cross-species prion conversion in a yeast model. BMC Biology 2009; 7:26; PMID:19470166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1741-7007-7-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Bondarev SA, Zhouravleva GA, Belousov MV, Kajava AV. Structure-based view on [PSI+] prion properties. Prion 2015; 9:190-9; PMID:26030475; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19336896.2015.1044186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Paul KR, Ross ED. Controlling the prion propensity of glutamine/asparagine-rich proteins. Prion 2015; 9:347-54; PMID:26555096; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/19336896.2015.1111506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Vanik DL, Surewicz KA, Surewicz WK. Molecular basis of barriers for interspecies transmissibility of mammalian prions. Mol Cell 2004; 14:139-45; PMID:15068810; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00155-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Preis A, Heuer A, Barrio-Garcia C, Hauser A, Eyler DE, Berninghausen O, Green R, Becker T, Beckmann R. Cryoelectron microscopic structures of eukaryotic translation termination complexes containing eRF1-eRF3 or eRF1-ABCE1. Cell Rep 2014; 8:59-65; PMID:25001285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]